Linehan's (Reference Linehan1993) seminal biosocial theory purports that emotion dysregulation (ED), involving biological vulnerabilities to disrupted emotion and emotion regulation deficits (i.e. difficulties altering emotion; Gross & Thompson, Reference Gross, Thompson and Gross2007), is central to borderline personality disorder (BPD). Linehan (Reference Linehan1993) postulated three components of the former: heightened sensitivity (i.e. lower threshold for emotion), heightened reactivity (i.e. larger increase in emotion post-provocation), and delayed recovery (i.e. slower decreases in emotion post-provocation; Linehan, Reference Linehan1993). Research testing this theory is mixed, but methodological limitations obfuscate clear conclusions about whether BPD is characterized by ED.

Antecedent-based ED

Basal vagal tone

Emotion processes occur before (antecedent-based) or after (response-based) provocation (Gross, Reference Gross1998). Although Linehan's (Reference Linehan1993) ED components are response-based, subsequent studies suggest that BPD may be characterized by antecedent-based ED such as low basal vagal tone. Basal vagal tone is indexed by baseline respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA), which reflects variations in heart rate with respiration and represents the interaction of two efferent pathways from the parasympathetic nerve to the heart on cardiac activity (Porges, Doussard-Roosevelt, & Maita, Reference Porges, Doussard-Roosevelt and Maita1994). Basal vagal tone theoretically indicates greater vulnerability to intense negative emotion whereas increases in vagal tone reflect increases in parasympathetic activation and consequential decreases in reactivity (Beauchaine, Reference Beauchaine2001; Porges et al., Reference Porges, Doussard-Roosevelt and Maita1994). Although there are exceptions (Austin, Riniolo, & Porges, Reference Austin, Riniolo and Porges2007; Gratz, Richmond, Dixon-Gordon, Chapman, & Tull, Reference Gratz, Richmond, Dixon-Gordon, Chapman and Tull2019), several studies and a meta-analysis evince lower baseline RSA in BPD compared to healthy control (HC) and clinical groups (e.g. Koenig, Kemp, Feeling, Thayer, & Kaess, Reference Koenig, Kemp, Feeling, Thayer and Kaess2016; Kuo, Fitzpatrick, Metcalfe, & McMain, Reference Kuo, Fitzpatrick, Metcalfe and McMain2016; Kuo & Linehan, Reference Kuo and Linehan2009; Weinberg, Klonsky, & Hajcak, Reference Weinberg, Klonsky and Hajcak2009). However, research examining these processes in BPD is limited by inconsistent physiological recording procedures (Carr, de Vos, & Saunders, Reference Carr, de Vos and Saunders2018) and needs standardization.

Baseline emotion

Literature also demonstrates heightened baseline emotion in BPD across self-reported and sympathetic indices compared to clinical and healthy groups (e.g. Ebner-Priemer et al., Reference Ebner-Priemer, Welch, Grossman, Reisch, Linehan and Bohus2007; Elices et al., Reference Elices, Soler, Fernández, Martín-Blanco, Jesús Portella, Pérez and Carlos Pascual2012; Feliu-Soler et al., Reference Feliu-Soler, Pascual, Soler, Pérez, Armario, Carrasco and Borràs2013; Gratz, Rosenthal, Tull, Lejuez, & Gunderson, Reference Gratz, Rosenthal, Tull, Lejuez and Gunderson2010; Köhling et al., Reference Köhling, Moessner, Ehrenthal, Bauer, Cierpka, Kämmerer and Dinger2016; Kuo et al., Reference Kuo, Fitzpatrick, Metcalfe and McMain2016; Kuo & Linehan, Reference Kuo and Linehan2009; Scott, Levy, & Granger, Reference Scott, Levy and Granger2013). However, some findings suggest that physiological indices do not distinguish BPD from other clinical groups (e.g. Kuo & Linehan, Reference Kuo and Linehan2009), suggesting that BPD may be uniquely characterized by self-reported, but not physiological, antecedent-based ED.

Response-based emotion

Of the response-based emotion processes specified in Linehan's (Reference Linehan1993) model, emotional reactivity, recovery, and regulation have received the most empirical attention.

Emotional reactivity

Unlike with antecedent-based emotion, reactivity research that examines the extent to which emotion increases in response to a stressor from baseline in BPD is mixed. Some studies show heightened self-reported reactivity in BPD (e.g. Chapman, Dixon-Gordon, Butler, & Walters, Reference Chapman, Dixon-Gordon, Butler and Walters2015; Dixon-Gordon, Gratz, & Tull, Reference Dixon-Gordon, Gratz and Tull2013a; Dixon-Gordon, Yiu, & Chapman, Reference Dixon-Gordon, Yiu and Chapman2013b; Gratz et al., Reference Gratz, Richmond, Dixon-Gordon, Chapman and Tull2019; Rosenthal et al., Reference Rosenthal, Neacsiu, Geiger, Fang, Ahn and Larrauri2016), while others do not (e.g. Elices et al., Reference Elices, Soler, Fernández, Martín-Blanco, Jesús Portella, Pérez and Carlos Pascual2012; Evans, Howard, Dudas, Denman, & Dunn, Reference Evans, Howard, Dudas, Denman and Dunn2013; Feliu-Soler et al., Reference Feliu-Soler, Pascual, Soler, Pérez, Armario, Carrasco and Borràs2013; Sansone, Wiederman, Hatic, & Flath, Reference Sansone, Wiederman, Hatic and Flath2010; Scott et al., Reference Scott, Levy and Granger2013). Some suggest heightened sympathetic and parasympathetic reactivity in BPD (e.g. Austin et al., Reference Austin, Riniolo and Porges2007; Dixon-Gordon et al., Reference Dixon-Gordon, Gratz and Tull2013a, Reference Dixon-Gordon, Yiu and Chapmanb; Ebner-Priemer et al., Reference Ebner-Priemer, Welch, Grossman, Reisch, Linehan and Bohus2007; Rosenthal et al., Reference Rosenthal, Neacsiu, Geiger, Fang, Ahn and Larrauri2016) while others either do not (e.g. Baschnagel, Coffey, Hawk, Schumacher, & Holloman, Reference Baschnagel, Coffey, Hawk, Schumacher and Holloman2013; Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Dixon-Gordon, Butler and Walters2015; Dixon-Gordon et al., Reference Dixon-Gordon, Weiss, Tull, DiLillo, Messman-Moore and Gratz2015; Ebner-Priemer et al., Reference Ebner-Priemer, Badeck, Beckmann, Wagner, Feige, Weiss and Bohus2005; Gratz et al., Reference Gratz, Richmond, Dixon-Gordon, Chapman and Tull2019; Kuo et al., Reference Kuo, Fitzpatrick, Metcalfe and McMain2016; Kuo & Linehan, Reference Kuo and Linehan2009), or lower sympathetic reactivity (e.g. Herpertz et al., Reference Herpertz, Schwenger, Kunert, Lukas, Gretzer, Nutzmann and Sass2000; Herpertz, Kunert, Schwenger, & Sass, Reference Herpertz, Kunert, Schwenger and Sass1999; Pfaltz et al., Reference Pfaltz, Schumacher, Wilhelm, Dammann, Seifritz and Martin-Soelch2015). Studies examining neural activity and other emotion indices (e.g. eyeblink, electromyography) are similarly mixed (e.g. Baschnagel et al. Reference Baschnagel, Coffey, Hawk, Schumacher and Holloman2013; Baskin-Sommers, Vitale, MacCoon, & Newman, Reference Baskin-Sommers, Vitale, MacCoon and Newman2012; Elices et al. Reference Elices, Soler, Fernández, Martín-Blanco, Jesús Portella, Pérez and Carlos Pascual2012; Hazlett et al. Reference Hazlett, Zhang, New, Zelmanova, Goldstein, Haznedar and Chu2012; Herpertz et al., Reference Herpertz, Kunert, Schwenger and Sass1999; Reference Herpertz, Schwenger, Kunert, Lukas, Gretzer, Nutzmann and Sass2000; Pfaltz et al. Reference Pfaltz, Schumacher, Wilhelm, Dammann, Seifritz and Martin-Soelch2015; Rosenthal et al. Reference Rosenthal, Neacsiu, Geiger, Fang, Ahn and Larrauri2016; Scott et al. Reference Scott, Levy and Granger2013; Smoski et al., Reference Smoski, Salsman, Wang, Smith, Lynch, Dager and Linehan2011). Taken together, emotional reactivity is highly discordant across self-report and physiological indices, leading some to suggest that physiological emotional reactivity may not characterize BPD to the same extent as self-report (Rosenthal et al., Reference Rosenthal, Gratz, Kosson, Cheavens, Lejuez and Lynch2008).

Emotional recovery

The few studies that have investigated emotional recovery in BPD produce similarly mixed findings across indices. Although studies suggest that BPD or high BPD feature groups exhibit delayed self-reported emotional recovery (Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Dixon-Gordon, Butler and Walters2015; Ebner-Priemer et al., Reference Ebner-Priemer, Houben, Santangelo, Kleindienst, Tuerlinckx, Oravecz and Kuppens2015), several other studies do not (Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Dixon-Gordon, Butler and Walters2015; Ebner-Priemer et al., Reference Ebner-Priemer, Houben, Santangelo, Kleindienst, Tuerlinckx, Oravecz and Kuppens2015; Fitzpatrick & Kuo, Reference Fitzpatrick and Kuo2015; Gratz et al., Reference Gratz, Rosenthal, Tull, Lejuez and Gunderson2010; Jacob et al., Reference Jacob, Kathrin, Ower, Pillmann, Scheel, Rüsch and Lieb2009; Scheel et al., Reference Scheel, Schneid, Tuescher, Lieb, Tuschen-Caffier and Jacob2013; Weinberg et al., Reference Weinberg, Klonsky and Hajcak2009). Similarly, two studies show delayed recovery in BPD heart rate or parasympathetic functioning (Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Dixon-Gordon, Butler and Walters2015; Fitzpatrick & Kuo, Reference Fitzpatrick and Kuo2015), but several suggest comparable sympathetic and parasympathetic recovery in BPD and control groups (Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Dixon-Gordon, Butler and Walters2015; Fitzpatrick & Kuo, Reference Fitzpatrick and Kuo2015; Scott et al., Reference Scott, Levy and Granger2013; Weinberg et al., Reference Weinberg, Klonsky and Hajcak2009).

Emotion regulation implementation

Finally, although individuals with BPD report greater difficulties with emotion regulation compared to HCs (Daros et al., Reference Daros, Williams, Jung, Turabi, Uliaszek and Ruocco2018), studies suggest that they can suppress emotions and reappraise emotional content following training in these strategies to a similar or better extant than healthy groups across neural, self-report, and parasympathetic indices (e.g. Baczkowski et al., Reference Baczkowski, van Zutphen, Siep, Jacob, Domes, Maier and van de Ven2017; Chapman, Rosenthal, & Leung, Reference Chapman, Rosenthal and Leung2009; Krause-Utz, Walther, Lis, Schmahl, & Bohus, Reference Krause-Utz, Walther, Lis, Schmahl and Bohus2019; Lang et al. Reference Lang, Kotchoubey, Frick, Spitzer, Grabe and Barnow2012; Marissen, Meuleman, & Franken, Reference Marissen, Meuleman and Franken2010; Ruocco, Medaglia, Ayaz, & Chute, Reference Ruocco, Medaglia, Ayaz and Chute2010; Schulze et al. Reference Schulze, Domes, Kruüger, Berger, Fleischer, Prehn and Herpertz2011). Individuals with BPD can also implement BPD-relevant treatment strategies such as mindfulness and distraction when trained to the same extent as healthy groups across self-report and physiological indices (Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Rosenthal and Leung2009; Kuo et al., Reference Kuo, Fitzpatrick, Metcalfe and McMain2016). Notably, mindfulness and distraction decrease emotion through opposite mechanisms, either by directing attention towards or away from it, respectively (Sheppes & Meiran, Reference Sheppes and Meiran2008). Therefore, individuals with BPD do not exhibit deficits in implementing emotion regulation strategies that they are trained in (i.e. emotion regulation implementation) across self-reported and psychophysiological domains, regardless of mechanism of action, although other emotion regulation forms may be deficient in BPD (e.g. perceived effectiveness of strategies and downregulation of elevated baseline emotion; Daros et al., Reference Daros, Williams, Jung, Turabi, Uliaszek and Ruocco2018; Kuo et al. Reference Kuo, Fitzpatrick, Metcalfe and McMain2016; Southward & Cheavens, Reference Southward and Cheavens2020).

Is BPD an ED disorder?

Taken together, studies suggest that BPD may be an ED disorder with respect to antecedent-based emotion but not response-based emotion. However, such conclusions are obfuscated by methodological limitations. First, although ED is arguably most commonly associated with BPD, it also underpins other affective disorders such as generalized anxiety disorder (GAD; Mennin, Heimberg, Turk, & Fresco, Reference Mennin, Heimberg, Turk and Fresco2005). GAD is also considered to be an ED disorder given that it is associated with heightened baseline emotion, emotional reactivity, and emotion regulation deficits across student and clinical samples (Mennin et al., Reference Mennin, Heimberg, Turk and Fresco2005). However, few studies have compared ED in BPD to other high-ED clinical groups, resulting in minimal clarity regarding whether BPD is uniquely characterized by ED. Second, although individuals with BPD exhibit heightened reactivity to BPD-relevant themes (e.g. rejection or abandonment) more so than generic stressors (Limberg, Barnow, Freyberger, & Hamm, Reference Limberg, Barnow, Freyberger and Hamm2011), much of the extant research used generalized inductions and may fail to capture ED in this group. Third, most studies have not examined whether dissociation is related to outcomes and, if so, controlled for it, even though it is common in BPD (Ross, Reference Ross2007) and dampens ED (Ebner-Priemer et al., Reference Ebner-Priemer, Badeck, Beckmann, Wagner, Feige, Weiss and Bohus2005). Fourth, existing studies measure self-reported emotion through discrete measurements periodically administered, losing variability in real-time emotion changes. Such limitations have been overcome with continuous rating dials (Ruef & Levenson, Reference Ruef, Levenson, Coan and Allen2007), but this innovation has not been applied to BPD ED research.

Clear assessment of ED in BPD thus requires: (a) a high ED clinical control group; (b) BPD-relevant inductions; (c) controlling for dissociation when necessary; (d) comprehensive assessment across emotion domains; and (e) continuous measurement of self-reported emotion. No studies have met all of these criteria under one experimental umbrella, which prohibits probing ED with granularity and drawing firm conclusions about which components characterize BPD when study-based variability is constant.

Accordingly, the present study examined whether baseline RSA, baseline emotion, reactivity, recovery, and emotion regulation implementation vary in BPD compared to HCs and a GAD control group across continuous self-report and physiological indices, using BPD-relevant emotion inductions, and controlling for dissociation where necessary. We examined two emotion regulation strategies with distinct mechanisms, mindfulness and distraction (e.g. Linehan, Reference Linehan1993, Reference Linehan2015), to clarify if emotion regulation implementation deficits in BPD are specific to, or pervasive across, strategy types. We hypothesized that individuals with BPD would exhibit lower baseline RSA and higher baseline emotion relative to HCs. Consistent with Linehan (Reference Linehan1993), we also hypothesized that individuals with BPD would exhibit heightened reactivity, delayed recovery, and greater emotion regulation implementation deficits in both strategies, relative to HCs. We considered comparisons with the GAD group exploratory.

Methods

Participants

Forty age and sex-matched individuals with BPD, GAD, and HCs (N = 120), 18–60 years old were recruited online and via fliers. Consistent with other BPD studies (e.g. Elices et al., Reference Elices, Soler, Fernández, Martín-Blanco, Jesús Portella, Pérez and Carlos Pascual2012; Kuo & Linehan, Reference Kuo and Linehan2009), exclusion criteria were: medication that influences psychophysiology [e.g. beta-blockers, psychiatric medications other than selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (Licht, de Geus, van Dyck, & Penninx, Reference Licht, de Geus, van Dyck and Penninx2010)]; and current comorbid medical (e.g. epilepsy, heart/respiratory conditions) or psychiatric (i.e. alcohol or substance use dependence; bipolar I disorder, severe psychotic disorder) conditions that interfere with psychophysiology or task completion. To promote some distinction between BPD and control groups, prospective participants in the GAD and HC groups were excluded if they endorsed 4 + BPD criteria, or self-harm/suicidality or impulsivity BPD criteria. HCs were also excluded if they had any current psychiatric diagnoses or were taking any current psychiatric medications. Demographic and diagnostic information across groups is shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. Demographic and diagnostic information across groups

Note. There were significant group differences in BPD severity, F(2, 116) = 79.12, p < 0.001, depression, F(2, 117) = 51.70, p < 0.001, anxiety, F(2, 117) = 34.15, p < 0.001, and stress, F(2, 117) = 68.08, p < 0.001. For post-hoc contrasts examining group differences in BPD, depression, or anxiety severity only:.

aSignificant difference at p < 0.05 between BPD and HC groups.

bSignificant difference at p < 0.05 between GAD and HC groups.

cSignificant difference at p < 0.05 between BPD and GAD groups.

Table 2. Common current comorbidities across BPD and GAD groups

Note. Additional information about diagnostic comorbidities presented in Fitzpatrick, Maich, Kuo, and Carney (Reference Fitzpatrick, Maich, Kuo and Carney2020). Significant group differences are shown in bold.

Measures

The Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV-TR (SCID-IV-TR; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams1995) was administered to assess for GAD and diagnostic comorbidities. The International Personality Disorders Examination-BPD Module (IPDE-BPD; Loranger et al., Reference Loranger, Sartorius, Andreoli, Berger, Buchheim, Channabasavanna and Regier1994) was used to assess BPD. Undergraduate and master's-level assessors trained to reliability against a gold-standard assessor and supervised by a licensed clinical psychologist administered all interviews, with prevalence-adjusted bias-adjusted kappas (PABAKs; Byrt, Bishop, & Carlin, Reference Byrt, Bishop and Carlin1993) with the gold-standard assessor ranging from 0.67 to 1.00 across modules (average PABAK for SCID-IV-TR = 0.97 for IPDE-BPE = 0.95).

The Dissociative State Scale (DSS; Stiglmayr, Shapiro, Stieglitz, Limberger, & Bohus, Reference Stiglmayr, Shapiro, Stieglitz, Limberger and Bohus2001) is a 21-item scale that was used to measure state dissociation, with higher scores reflecting higher dissociation (α ranged from 0.92 to 0.93 across baseline and trials).

To characterize the sample, the Borderline Symptom List-23 (BSL-23; Bohus et al., Reference Bohus, Limberger, Frank, Chapman, Kühler and Stieglitze2007) was used to measure BPD severity (α = 0.97), and the depression, anxiety, and stress scales (DASS; Lovibond & Lovibond, Reference Lovibond and Lovibond1995) was used to measure depression, anxiety, and stress severity (subscale α = 0.92–0.97).

Emotion indices

Participants were asked to keep one hand on a rating dial throughout the experiment and adjust it to reflect shifts in self-reported emotional intensity. The dial ranges from 0 (very negative) to 9 (very positive) and allowed for a continuous, moment-by-moment, assessment of negative emotion, which was decomposed into 30 s epochs.Footnote †Footnote 1

Participants also rated the following experiences using a visual analog scale from 0 (not at all) to 100 (very) before and after each emotion induction: afraid, alone/lonely, angry, anxious, ashamed, disgusted, empty, guilty, hopeless, rejected, sad, and tense. Ratings for these emotions were summed together to yield a negativity composite used in manipulation check analyses. Following the implementation of mindfulness and distraction, participants were asked to rate how effective the strategy was in affecting their emotions from 0 (made much worse or much more intense) to 100 (made much better or much less intense).

Skin conductance responses (SCRs) were examined as a sympathetic index of emotion. Electrodes were placed on the medial phalanges of the middle and index finger of participant's non-dominant hand (Fowles et al., Reference Fowles, Christie, Edelberg, Grings, Lykken and Venables1981). SCRs were digitized using low (35 Hz) and high (0.05 Hz) pass filters at 1000 samples per second and a gain of 1000. Mindware Technologies EDA 2.40 program was used to process the data. A rolling filter detected and edited artifacts. SCR was indexed as the number of responses exceeding 0.05 μS per 30 s epoch.

RSA was examined as an index of basal vagal tone and parasympathetic emotion. A two-electrode electrocardiography configuration (i.e. one electrode placed 3–4 in. beneath the right clavicle, and the other placed beneath the left rib cage) with a bioimpedance module for grounding was used, with a respiratory band around the chest and a sampling frequency of 1000 samples/s. Mindware Technologies HRV 2.33 software was used to calculate R-R intervals across 30 s epochs. Mindware software detected R-spikes using the Shannon Energy Envelope technique (Manikandan & Soman, Reference Manikandan and Soman2012), and all data was further visually inspected and double-scored to scan for artifacts and correct R-spike identification. Following detection of R-spikes, interbeat intervals (IBIs) for subsequent beats were computed by subtracting the time at which they occurred from one another. Spectral analysis decomposed the electrocardiogram into three frequency ranges, applying validated algorithm to calculate spectral densities and retaining RSA signals within the frequency of 0.12–0.4 Hz. All measurements were taken with participants sitting upright with their feet placed on the floor. Data collected during segments of the experiment wherein the participants were clearly not complying with instructions, or the electrocardiogram was not detectable due to noise, were removed from analyses.

Emotion induction

We developed three, 2 min rejection-themed scripts with standardized numbers of thoughts and physiological sensations described in them across scripts, and standardized intensity of emotional words, across scripts (see open science framework for more information on script development).Footnote 2 Pilot data with 55 undergraduates demonstrated scripts elicit equivalent amounts of pre- to post-self-reported general negative emotion, F (2, 53) = 1.62, p = 0.21.

Procedures

Procedures were approved by institutional research boards. Interested participants were pre-screened and, if eligible, invited for an in-person eligibility assessment (SCID-IV-TR, IPDE). Eligible participants were invited to return for the experiment and instructed to avoid stimulants (e.g. caffeine, tobacco) on the experiment day. The time of experiments varied throughout the day and evening. Physiological equipment was attached and participants were instructed on rating dial use. Participants completed an initial 10 min resting baseline with no stimuli presented. To ensure stability, only the last 5 min of this baseline was analyzed (Jennings, Kamarck, Stewart, & Eddy, Reference Jennings, Kamarck, Stewart and Eddy1992).

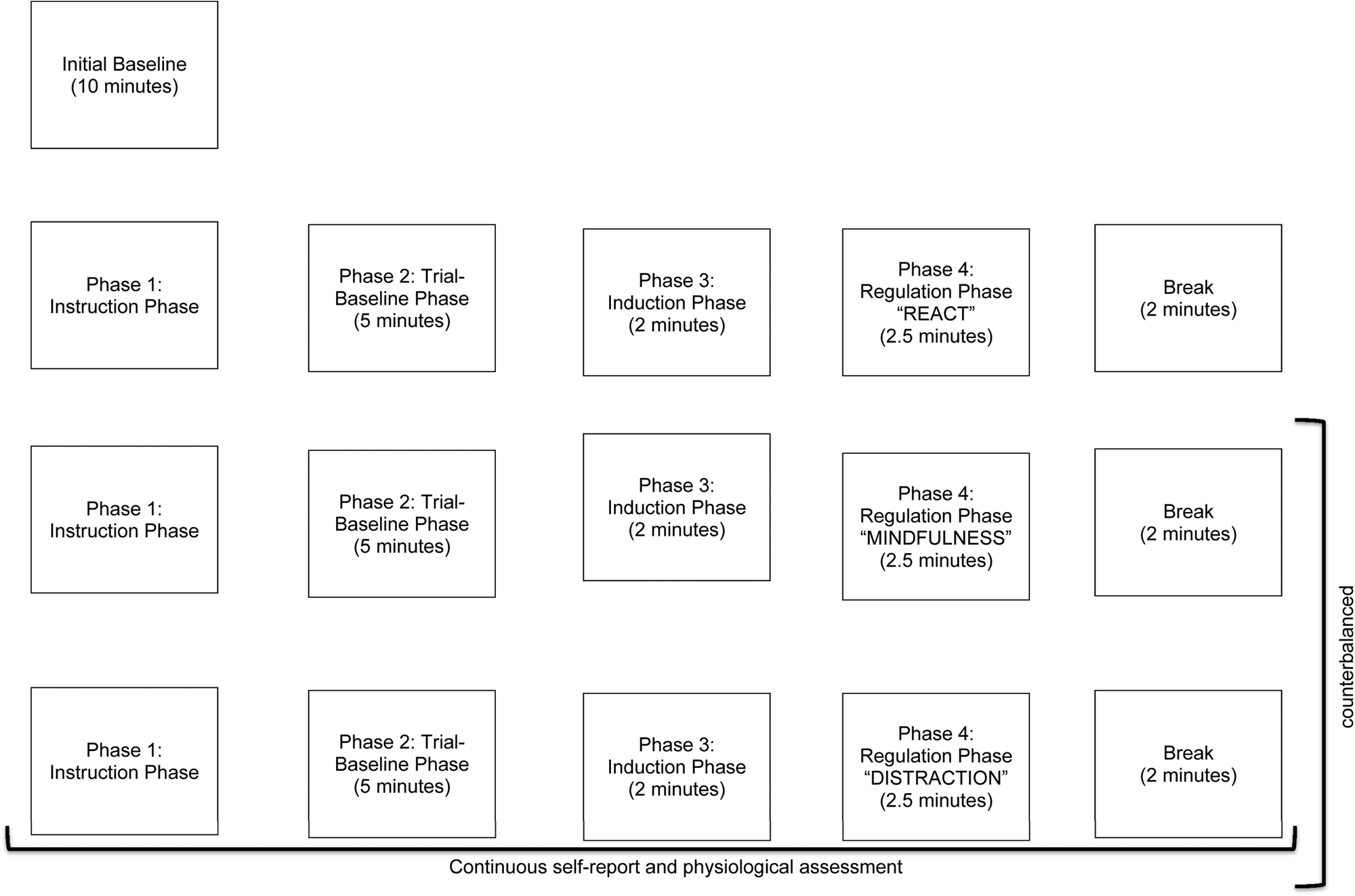

See Fig. 1 for an illustration of the experiment. Following baseline, the laboratory task was a within-subjects design involving three trials (REACT, MINDFULNESS, DISTRACTION), each of which involved four phases. In Phase 1 (instruction phase) of the first trial (REACT condition), participants were instructed to ‘act as they normally would’ (Kuo et al., Reference Kuo, Fitzpatrick, Metcalfe and McMain2016) when prompted. This condition allowed for assessment of post-induction recovery without instructed emotion regulation implementation. In Phase 1 of the second and third trials, participants were trained in the MINDFULNESS or DISTRACTION conditions. For MINDFULNESS, participants were instructed to non-judgmentally notice emotional experiences without rejection or amplification (Erisman & Roemer, Reference Erisman and Roemer2010; Kuo et al., Reference Kuo, Fitzpatrick, Metcalfe and McMain2016). For DISTRACT, the participants were instructed to distract themselves from induction content by thinking of something neutral (Kuo et al., Reference Kuo, Fitzpatrick, Metcalfe and McMain2016; Sheppes & Meiran, Reference Sheppes and Meiran2008) to avoid confounding distraction with positive emotion inductions by attending to positively valenced thoughts. Participants verbally repeated instructions to ensure understanding, with clarification provided as needed.

Fig. 1. Illustration of experimental phases and trials.

Across all trials, during Phase 2 (trial-baseline phase), participants sat quietly for 5 min while baseline measurements were taken again. Next, in Phase 3 (induction phase), participants listened to an induction script and were asked to imagine themselves in the scenario depicted for 2 min (i.e. four 30 s epochs). Finally, in Phase 4 (regulation phase), an on-screen prompt cued participants to engage in the emotion regulation strategy. Participants implemented react, mindfulness, or distraction for 2.5 min (i.e. five 30 s epochs), after which the DSS was administered. Rating dial and physiological recordings were continuous. Order of strategy presentation (mindfulness and distract), and pairings of strategy and emotion induction scripts were counterbalanced. Participants rated the extent to which they attempted to use mindfulness and distraction when instructed, ranging from 0% to 100% of the time.

Data analytic strategy

Generalized estimating equations (GEE; Burton, Gurrin, & Sly, Reference Burton, Gurrin and Sly1998; Hubbard et al., Reference Hubbard, Ahern, Fleischer, Van, Lippman, Jewell and Satariano2010) was used to analyze data with SPSS version 26. GEE is a semi-parametric extension of generalized linear modeling and maximizes power by examining outcome variables over continuous time courses and retaining information from participants with missing data. Autoregressive, exchangeable, and unstructured covariance structures were examined and the one with the lowest quasi-likelihood under the independence model criterion (QIC) value was selected. A negative binomial distribution was specified for SCR data which is typically an overdispersed count variable (Atkins & Gallop, Reference Atkins and Gallop2007). Continuous predictors were median-centered.

Analyses were run separately for each outcome (i.e. baseline emotional intensity/biological vulnerability, reactivity, recovery, mindfulness, distraction) and index nested within them (i.e. self-report, SCR, RSA). For baseline emotional intensity/biological vulnerability, emotion across 30 s epochs for the last 5 min of the initial baseline was the outcome, with groups (BPD, GAD, HC) as a between-subjects factor. For reactivity, emotional intensity for each 30 s epoch across the three induction phases (four epochs per phase = 12 repeated measures) was the outcome. For recovery, emotion across 30 s epochs during the regulation phase of the REACT condition was the outcome. In both analyses, group was a between-subjects factor, with either emotion from the trial-baselines preceding the inductions (reactivity analyses) or emotion from the induction preceding the REACT phase (recovery analyses) entered as a within-subjects covariate. In both, epoch was entered as a within-subjects predictor and group × epoch interactions were entered to test whether groups varied in change in emotion over the induction or regulation phase of the REACT condition, respectively. For mindfulness/distraction analyses, emotion across the 30 s epochs during either the regulation phase of the MINDFULNESS and DISTRACT conditions were the outcomes. Group was entered as a between-subjects factor, emotion from the induction phase that preceded it was entered as within-subjects covariate, and epoch was entered as a within-subjects predictor. Group × epoch interactions were entered to test whether groups varied in the change in emotion over the emotion regulation implementation phase. Univariate analyses of variance were performed to examine group differences in perceived effectiveness of distraction and mindfulness. In line with concerns regarding potential dilution of results due to the application of multiple tests corrections, they were not employed (e.g. O'Keefe, Reference O'Keefe2003; Rothman, Reference Rothman1990).

Identification of potential covariates

Higher dissociation was significantly or trending towards significantly correlated with self-reported negative emotion across several experiment components (significant or trending rs range from −0.22 to −0.17, ps from <0.02 to 0.06), and negative emotion from the visual analog scales (all ps ⩽ 0.001). Dissociation was not significantly correlated with physiological indices during any phases across conditions (ps range from 0.10 to 0.97), or the perceived effectiveness of emotion regulation strategies (ps range from 0.14 to 0.15). We, therefore, entered dissociation from each trial into the model as a within-subjects covariate for analyses examining self-reported emotion processes only.

Comparisons of the number of current comorbid psychological disorders within each group suggested that the BPD group had higher rates of alcohol abuse and dysthymic disorder, and lower rates of GAD (see Table 2). Groups did not significantly differ in age (p = 0.73), sex, gender identity, or race/ethnicity (ps range from 0.17 to 0.92). However, there were significant differences across race/ethnicity groups collapsed into three categories: White/Caucasian/European origin, Asian, and others, χ2(1) = 11.97, p = 0.02. We, therefore, included current comorbid alcohol abuse and dysthymic disorder, and race/ethnicity (with three categories), into all primary study analyses as between-subjects covariates.

ResultsFootnote 3

Mean BPD severity in the BPD group was within a standard deviation of that of treatment-seeking in patient samples with BPD (Kröger, Harbeck, Armbrust, & Kliem, Reference Kröger, Harbeck, Armbrust and Kliem2013), but mean BPD severity within the GAD and HC groups were not. See Table 1 for information regarding specific group differences in severity measures.

Manipulation check

Participant means and standard deviations for outcomes and dissociation are in Table 3. GEE analyses examining change in negative emotion across epochs from trial-baseline to induction within each group revealed main effects of phase (trial-baseline to induction) for self-reported negative emotion, which increased in BPD (B = −1.26, s.e. = 0.16), GAD (B = −1.33, s.e. = 0.18, and HC (B = −0.73, s.e. = 0.16) groups (all ps > 0.001). However, although there was a main effect of phase for SCRs for HCs (B = 0.23, s.e. = 0.09), χ2 (1) = 6.42, p = 0.01, this effect was not significant in BPD or GAD groups (ps = 0.22). As well, although there was a main effect of phase for RSA for the GAD group (B = −0.20, s.e. = 0.03), χ2 (1) = 32.45, p < 0.001, this effect was not significant in BPD or HC groups (ps = 0.64 and 0.35, respectively). These findings indicate that the induction induced negative emotion across self-reported domains, but was variable in its impact on physiological ones. Groups did not differ with respect to the extent to which they attempted to implement mindfulness, F(2, 116) = 0.78, p = 0.46, or distraction, F(2, 114) = 1.81, p = 0.17.

Table 3. Means (s.d.) across conditions, phases, and groups

Antecedent-based emotion

Primary study results are in Table 4. Group predicted self-reported baseline emotional intensity, wherein BPD (B = −0.98, s.e. = 0.33) and GAD (marginally significant; B = −0.57, s.e. = 0.29) groups exhibited more self-reported negative emotion at baseline than HCs, χ2(1) = 8.87, p = 0.003, and χ2(1) = 4.00, p = 0.05, respectively, but did not differ from each other, χ2(1) = 2.24, p = 0.13. Group also predicted baseline SCR, wherein BPD (B = 0.56, s.e. = 0.23) and GAD (B = 0.64, s.e. = 0.24) groups exhibited more self-reported negative emotion at baseline than HCs, χ2(1) = 5.79, p = 0.02, and χ2(1) = 6.89, p = 0.01, respectively, but did not differ from each other, χ2(1) = 0.09, p = 0.76. There was not a main effect of group predicting basal RSA.

Table 4. Primary GEEs analyses

Note. Statistically significant effects relevant to study hypotheses are shown in bold. s.e. = standard error; df = degrees of freedom.

Emotional reactivity/recovery

There was a significant main effect of group for self-reported reactivity such that the HCs exhibited less self-reported negative emotion across the induction phase than the BPD group (B = −0.64, s.e. = 0.24), χ2(1) = 7.08, p = 0.01, but not the GAD group, χ2(1) = 3.14, p = 0.08. The BPD and GAD groups did not differ from each other, χ2(1) = 1.73, p = 0.19. Group did not predict SCR or RSA reactivity, or any recovery indices, and group × epoch interactions did not predict any reactivity or recovery index.

Emotion regulation implementation

A group × epoch interaction predicted self-reported emotion in the distraction condition. There was less decrease in negative emotion in BPD relative to the GAD group (B = −0.22, s.e. = 0.07), χ2(1) = 8.44, p = 0.004. However, there were no differences between change in emotion in the HC and BPD, χ2(1) = 0.83, p = 0.36, or GAD, χ2(1) = 2.92, p = 0.09, groups. There was also a group × epoch interaction predicting SCR in the mindfulness condition. There was less decrease in SCR in the GAD group (B = 0.21, s.e. = 0.08), χ2(1) = 6.96, p = 0.01, but not in the BPD group, χ2(1) = 2.55, p = 0.11, compared to HCs. However, there were no differences in change in SCR in the BPD group compared to GAD group, χ2(1) = 1.21 p = 0.27. There were no other group × epoch interactions across indices and conditions.

Perceived effectiveness

Univariate analyses of variance indicated that there were not significant main effects of group predicting perceived effectiveness of mindfulness, F(2, 110) = 0.42, p = 0.66, or distraction, F(2, 108) = 0.97, p = 0.38.

Discussion

This study aimed to clarify whether BPD is uniquely or generally characterized by the prominent ED components by studying distinct and continuous emotion, using BPD-relevant inductions, compared to healthy and ED clinical control groups, after accounting for dissociation where necessary.

Antecedent-based emotion

In contrast to our hypotheses, no significant differences in basal vagal tone emerged between the groups. Most people with BPD take psychiatric medications (Hörz, Zanarini, Frankenburg, Reich, & Fitzmaurice, Reference Hörz, Zanarini, Frankenburg, Reich and Fitzmaurice2010), many of which were exclusion criteria for this study, which may have eliminated higher-severity participants, obfuscating differences in low basal vagal tone across groups. However, as studies with similar inclusion criteria evince lower basal vagal tone in BPD (e.g. Kuo et al., Reference Kuo, Fitzpatrick, Metcalfe and McMain2016), severity may not wholly account for these null findings. As well, we found that high self-reported negative emotion and sympathetic baseline activity characterize both high ED groups relative to HCs, but these phenomena are not specific to BPD. Furthermore, post-hoc analyses that involved including continuous measures of depression and anxiety as covariates resulted in the main effect of group on self-reported baseline emotion becoming non-significant. These findings indicate that comorbid depression or anxiety severity may account for heightened self-reported baseline emotion.

Response-based emotion

Emotional reactivity and recovery

Our findings further indicate discordance among reactivity indices. BPD and GAD groups exhibited higher self-reported negative emotion than the HC group during the induction phase after controlling for baseline emotion, suggesting that both of these groups experienced the inductions more intensely than HCs. However, post-hoc analyses with continuous measures of depression and anxiety, wherein the main effect of group became non-significant, suggest that these covariates may account for these differences. Furthermore, group × epoch interactions predicting self-reported negative emotion were non-significant, indicating that the rate of increase during the emotion induction was comparable across groups. These findings suggest that, while individuals with BPD and GAD experience provocations with greater intensity, these findings may be due to the severity of comorbid mood and anxiety disturbances they experience, and their rate of increase following those provocations is not atypical, further suggesting that generally elevated resting emotion may be characteristic of ED disorders but not BPD specifically. Researchers have examined both the main effect of group and group × epoch interactions as indices of reactivity, and little attention has been paid to the ways in which it has been, or should be, quantified. These findings importantly indicate that greater attention to the quantification of emotional reactivity is needed as it may lead to notably distinct results.

Our self-reported and physiological recovery results join many studies in suggesting lack differences between BPD and control groups on these outcomes (e.g. Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Dixon-Gordon, Butler and Walters2015; Dixon-Gordon et al., Reference Dixon-Gordon, Weiss, Tull, DiLillo, Messman-Moore and Gratz2015; Fitzpatrick & Kuo, Reference Fitzpatrick and Kuo2015; Kuo & Linehan, Reference Kuo and Linehan2009). It is possible that the emotion induction scripts were not potent or generalizable enough to induce heightened reactivity or prolonged recovery in BPD, especially in the physiological domain wherein they resulted in mixed effects across groups. Indeed, heightened reactivity in BPD has been more typically observed in everyday interactions (Glaser, Van Os, Mengelers, & Myin-Germeys, Reference Glaser, Van Os, Mengelers and Myin-Germeys2008, Reference Glaser, Van Os, Thewissen and Myin-Germeys2010). However, it is also possible that examining the effects of the induction within groups masked potentially significant impacts on the physiological domain due to low statistical power. Indeed, significant main effects of epoch in our primary study analyses suggest that both self-reported negative emotion and SCR increased across groups during the emotion induction, supporting its efficacy in these domains. Finally, delayed recovery may be specific to some emotions (e.g. anger) but not others, which was not examined in this study. However, past work also suggests that emotion-specific delayed recovery is evident in BPD compared to HCs but not clinical groups (Fitzpatrick & Kuo, Reference Fitzpatrick and Kuo2015). BPD may thus not be characterized by heightened physiological reactivity, or delayed recovery, compared to other clinical groups.

Emotion regulation implementation

Partially in line with our hypothesis, the BPD group exhibited lesser reduction in self-reported negative emotion in the distraction condition compared to the GAD, but not the HC, group. Distraction requires that an individual divert attention away from emotion, which is a core emotion deficit in BPD (Winter, Reference Winter2016). Selby and Joiner (Reference Selby and Joiner2009) purport that, following an emotional evocation, individuals with BPD ruminate, which exacerbates negative emotion. Such rumination may prevent individuals with BPD from shifting attention away from emotional content. Alternatively, individuals with BPD may be comparable to others in the use of distraction, and individuals with GAD may actually be particularly strong at it. Consistently, several theories of GAD emphasize the central role of avoidance of inner experiences (e.g. Behar, DiMarco, Hekler, Mohlman, & Staples, Reference Behar, DiMarco, Hekler, Mohlman and Staples2009), which may facilitate distraction.

Results also suggested that the GAD group was particularly deficient in mindfulness relative to HCs in decreasing sympathetic activity. The high avoidance that characterizes GAD may have made mindfulness, which directs attention towards such experiences, particularly challenging for this group. Alternatively, perhaps both BPD and GAD groups exhibit difficulties decreasing sympathetic activity using a strategy that directs attention towards it (i.e. mindfulness), but the BPD group was more practiced and consequently effective in this skill, given its emphasis in leading BPD treatments (i.e. DBT; Linehan, Reference Linehan1993, Reference Linehan2015). Mindfulness is also a complex skill that may require more training than distraction to effectively implement, which may mask potential deficits in this strategy in the BPD group if even HCs struggle with its use. Future research should examine history with mindfulness as a moderator of strategy effectiveness.

It is notable that BPD-specific effects for emotion regulation implementation were limited to the self-reported domain. Perhaps individuals with BPD are particularly likely to report problems distracting even if they physiologically do not experience them. However, the BPD group was not more or less likely to perceive either mindfulness or distraction as less effective than other groups, indicating that their deficits in distraction may extend beyond their reports of its efficacy. Moreover, it is notable that post-hoc analyses that involved the inclusion of continuous measures of depression and anxiety did not alter the significance of these interactions. Thus, unlike with differences in general self-reported emotion across groups, emotion regulation problems or lack thereof may not be accounted for by common comorbidities in BPD and GAD groups.

Limitations, implications, and future directions

Although this work reflects a rigorous and unifying assessment of ED in BPD, several limitations warrant consideration. The BPD-relevant stories may not have been sufficiently potent to replicate daily life stressors for those with BPD, and our manipulation check suggested that they failed to evoke distress in the parasympathetic domain. Furthermore, this study may have been underpowered to detect group effects, particularly interaction effects, given its modest sample size. In addition, although the inclusion of a clinical control group is a strength of this study, it is also limited by the high rates of overlap in BPD and GAD groups, wherein 40% of the BPD group also had GAD, which may have obfuscated otherwise apparent differences between these two groups. Future studies should extend this work by ensuring greater divergence between clinical groups and controlling for other comorbid diagnoses that commonly occur with BPD. This may be particularly important for antisocial personality disorder as well as psychopathy, given that both are highly associated with BPD (Sprague, Javdani, Sadeh, Newman, & Verona, Reference Sprague, Javdani, Sadeh, Newman and Verona2012; Zanarini et al., Reference Zanarini, Frankenburg, Dubo, Sickel, Trikha, Levin and Reynolds1998), and ‘Factor 1’ psychopathy is characterized by processes that may blunt ED processes in BPD (e.g. lack of empathy, guilt, shallow affect; Harpur, Hare, & Hakstian, Reference Harpur, Hare and Hakstian1989). Moreover, we did not collect information on the treatment history of study participants, which may confound study findings given the overlap between the emotion regulation strategies studied and their emphasis in BPD treatments (e.g. Linehan, Reference Linehan1993, Reference Linehan2015). Indeed, it is possible that the BPD group did not show more signs of emotion regulation implementation deficits with mindfulness particularly because they were more likely to be already exposed to treatments that emphasize them.

This study also only examined one form of emotion regulation (i.e. implementation of skill following training), and other variants of emotion regulation, such as continued elevated emotion following successful emotion regulation implementation, and emotion regulation implementation without training, may be deficient in BPD and should be examined. Finally, despite evidence that some ED components may be emotion-specific (e.g. Fitzpatrick and Kuo, Reference Fitzpatrick and Kuo2015; Jacob et al., Reference Jacob, Kathrin, Ower, Pillmann, Scheel, Rüsch and Lieb2009), we did not examine this possibility.

Despite these limitations, this work has clinical and research implications. BPD treatments such as DBT (Linehan, Reference Linehan1993, Reference Linehan2015) focus on skills to alter ED, even though several ED processes may not be problematic in, or unique to, BPD. Our results and extant literature call for increased attention to additional processes beyond ED such as rumination (e.g. Selby & Joiner, Reference Selby and Joiner2009) and interpersonal dysfunction (Fitzpatrick, Wagner, & Monson, Reference Fitzpatrick, Wagner and Monson2019), that may uniquely characterize BPD and require targeting. Regarding ED, clinicians and researchers are advised to focus on antecedent-based emotion and deficits in disengaging from emotion as clinical targets and areas for additional research.

Financial support

This work was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant numbers: 201210GSD-304038-229817 and 201711MFE-395820-229817), the American Psychological Association Dissertation Research Award, and the Ontario Mental Health Foundation Studentship Award.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.