1. Introduction

Diabasic rocks occur as shallow intrusive bodies such as dykes and sills that are characterized by fine-grained to aphanitic chilled margins (Yang et al. Reference Yang, Sun, Chen, Wilde and Wu2007; Zhang, S. H. et al. Reference Zhang, Zhao, Yang, He and Wu2009). These lithologies are commonly associated with dyke swarms that comprise hundreds of individual dykes or sills radiating from a volcanic centre (e.g. Park, Buchan & Harlan, Reference Park, Buchan and Harlan1995; Ernst, Grosfils & Mege, Reference Ernst, Grosfils and Mege2001; Ali et al. Reference Ali, Thompson, Zhou and Song2005; Shellnutt, Reference Shellnutt2014; Li, H. et al. Reference Li, Zhang, Ernst, Lu, Santosh, Zhang and Cheng2015). Geochemically, mafic dykes or sills represent mantle-derived magmas that are usually associated with lithospheric-scale extensional tectonics in intraplate or post-collisional extensional settings (e.g. Kröner et al. Reference Kröner, Wilde, Zhao, O'Brien, Sun, Liu, Wan, Liu and Guo2006; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Sun, Chen, Wilde and Wu2007; Smirnov & Evans, Reference Smirnov and Evans2015). Analyses of such dykes and sills can also be used to reconstruct supercontinents and to determine the tectonic setting of orogenic belts (e.g. Halls et al. Reference Halls, Li, Davis, Hou, Zhang and Qian2000; Peng et al. Reference Peng, Zhai, Guo, Kusky and Zhao2007; Cai et al. Reference Cai, Sun, Yuan, Zhao, Xiao, Long and Wu2010). The spatial patterns, petrology, geochemistry and geochronology of dykes and sills in a number of orogenic belts, including the Palaeoproterozoic Trans-North China and the Cenozoic Himalayan orogenic belts, have been used to identify the mantle source regions for the magmatism in these regions as well as the evolution of individual orogens (e.g. Gorring & Kay, Reference Gorring and Kay2001; Williams et al. Reference Williams, Turner, Kelley and Harris2001; Gorring et al. Reference Gorring, Singer, Gowers and Kay2003; Kusky, Li & Santosh, Reference Kusky, Li and Santosh2007; Li et al. Reference Li, Zhao, Wilde, Zhang, Sun, Zhang and Dai2010; Wang, L. J. et al. Reference Wang, Griffin, Yu and O'Reilly2010; Wang, Q. et al. Reference Wang, Wyman, Li, Sun, Chung, Vasconcelos, Zhang, Dong, Yu, Pearsong, Qiu, Zhu and Feng2010). This indicates that the timing of crystallization and the geochemical compositions of mafic rocks can provide key insights into the evolution of the continental lithosphere and the onset of extension during post-orogenic collapse (e.g. Dewey, Reference Dewey1988; Rock, Reference Rock1991; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Sun, Chen, Wilde and Wu2007; Hou et al. Reference Hou, Li, Yang, Yao, Wang and Wang2008).

Magma oxygen fugacity is a key control on Cu–Mo–Au mineralization (e.g. Candela & Holland, Reference Candela and Holland1986; Lynton, Candela & Piccoli, Reference Lynton, Candela and Piccoli1993; Hedenquist & Lowenstern, Reference Hedenquist and Lowenstern1994; Liang et al. Reference Liang, Campbell, Allen, Sun, Liu, Yu, Xie and Zhang2006; Liu, S. et al. Reference Liu, Su, Hu, Feng, Gao, Coulson, Wang, Feng, Tao and Xia2010; Li et al. Reference Li, Zhang, Wang, Liu, Sun, Hao, Li and Sun2012; Qiu & Qiu, Reference Qiu and Qiu2016). For example, the genesis of major Au and Au-rich Cu deposits in supra-subduction zone type environments requires oxidation of the mantle wedge (e.g. Mungall, Reference Mungall2002; Kerrich, Goldfarb & Richards, Reference Kerrich, Goldfarb and Richards2005; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Santosh, Yuan, Li and Li2016). The presence of two periods of Carlin-like Au mineralization in the Youjiang Au–As–Sb–Hg province at 230–190 Ma and 150–130 Ma led Hu et al. (Reference Hu, Chen, Xu and Zhou2017a,b) to suggest that magmas beneath these deposits heated and caused the circulation of meteoric water, a process that mobilized metals from sedimentary rocks. These metals were subsequently concentrated to form the Au deposits in the SW South China Block (SCB). However, rare magmatic rocks have been identified in the Youjiang fold-and-thrust belt (Wang, Y. J. et al. Reference Wang, Fan, Zhang and Zhang2013; Qiu, L. et al. Reference Qiu, Yan, Tang, Arndt, Fan, Guo and Cui2015a,b, Reference Qiu, Yan, Tang, Wang, Yang, Wang and Tang2016). In addition, the recent discovery of an Au deposit hosted by the Badu diabase (Dong et al. Reference Dong, Su, Shen, Zhu and Cai2013; Li, P. et al. Reference Li, Pang, Wang, Li, Zhou, Lv and Ma2015) implies a genetic relationship between mafic magmatism (e.g. diabase dykes and/or sills), specific conditions of magmatic oxygen fugacity and the generation of Carlin-like Au mineralization. As such, the Badu diabase that hosts Carlin-type Au or Au-bearing mineralization in the study area provides an excellent opportunity to investigate the Triassic mineralization in this region, especially the influence of magma oxygen fugacity.

This study presents new insights into the timing and redox state of early Mesozoic mafic intrusive rocks of the southwestern SCB. Combining these data with previously published geochronological and geochemical results provides new insights into the nature of gold mineralization, the origin of mafic magmatism and the post-collisional extension in this region, all of which are addressed in the framework of the evolution of the Palaeo-Tethys.

2. Regional geology

The SCB was formed by the Neoproterozoic amalgamation of the Yangtze and Cathaysia blocks (Fig. 1a; e.g. Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Yan, Kennedy, Li and Ding2002; Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Zhou, Yan, Zheng and Li2011; Wang, Y. J. et al. Reference Wang, Fan, Zhang and Zhang2013). This block was subsequently subjected to early Palaeozoic and Mesozoic tectonic events (e.g. Lin, Wang & Chen, Reference Lin, Wang and Chen2008; Li et al. Reference Li, Zhao, Wilde, Zhang, Sun, Zhang and Dai2010; Wang, Y. J. et al. Reference Wang, Fan, Zhang and Zhang2013) and contains folded and metamorphosed Proterozoic basement material (e.g. Wang & Zhou, Reference Wang and Zhou2014; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Cawood, Zhou and Zhao2016) that is overlain by a folded Phanerozoic sedimentary cover sequence (Fig. 1; e.g. Yan et al. Reference Yan, Zhou, Song, Wang and Malpas2003, Reference Yan, Zhou, Wang and Xia2006, Reference Yan, Xu, Dong, Qiu, Zhang and Wells2016; Wang, Y. J. et al. Reference Wang, Fan, Zhang and Zhang2013; Qiu et al. Reference Qiu, Yan, Yang, Wang, Tang and Ariser2017). The basement in this region consists of metamorphosed Neoproterozoic shallow-marine sandy to argillaceous detrital flysch units that are intercalated with volcanic rocks Qiu et al. Reference Qiu, Yan, Tang, Arndt, Fan, Guo and Cui(2015a). The basement is overlain by a Palaeozoic to lower Mesozoic marine and Middle Triassic to Cretaceous clastic sedimentary cover sequence (Li et al. Reference Li, Zhang, Dong and Johnston2014; Tang et al. Reference Tang, Yan, Qiu, Gao and Wang2014; Qiu et al. Reference Qiu, Yan, Yang, Wang, Tang and Ariser2017).

Figure 1. Map showing the tectonic setting of the South China Block and adjacent blocks (after Yan et al. Reference Yan, Zhou, Song, Wang and Malpas2003; Faure et al. Reference Faure, Lepvrier, Nguyen, Vu, Lin and Chen2014, Reference Faure, Lin, Chu and Lepvrier2016b; Qiu, L. et al. Reference Qiu, Yan, Zhou, Arndt, Tang and Qi2014, Reference Qiu, Yan, Tang, Wang, Yang, Wang and Tang2016). The inset shows the continents and suture zones of East Asia (Metcalfe, Reference Metcalfe2013). Abbreviations: CB – Cathaysian Block; LS – Lhasa Block; WB – West Burma; QD – Qaidam Block; QS – Qamdo–Simao Block; QT – Qiangtang Block; SG – Songpan–Ganzi accretionary complex; YB – Yangtze Block.

The Phanerozoic tectonic configuration of Eurasia was a consequence of northward drift of continents from Gondwana and subsequent orogenic tectonism (e.g. Gehrels et al. Reference Gehrels, Kapp, Decelles, Pullen, Blakey, Weislogel, Ding, Guynn, Martin, Mcquarrie and Yin2011; Metcalfe, Reference Metcalfe2011, Reference Metcalfe2013; Faure et al. Reference Faure, Lin, Chu and Lepvrier2016a,b; Sun et al. Reference Sun, Yin, Yan, Ren, Mu, Zhu and Qiu2018; Yan et al. Reference Yan, Zhou, Qiu, Wells, Mu and Xu2018). The Triassic Indosinian orogeny is a key part of the tectonic history of the eastern Palaeo-Tethys and resulted from the amalgamation of the South China and Indochina blocks (e.g. Lepvrier et al. Reference Lepvrier, Faure, Van, Vu, Lin, Trong and Hoa2011; Faure et al. Reference Faure, Lepvrier, Nguyen, Vu, Lin and Chen2014, Reference Faure, Lin, Chu and Lepvrier2016a,b; Cao et al. Reference Cao, Yan, Qiu, Zhang and Qiu2015; Halpin et al. Reference Halpin, Tran, Lai, Meffre, Crawford and Zaw2016). This orogeny was originally identified from Late Triassic angular unconformities in Vietnam (e.g. Deprat, Reference Deprat1914; Fromaget, Reference Fromaget1932, Reference Fromaget1941), foreland basins, fold-and-thrust belts and large-scale granitic magmatism within the southwestern SCB (e.g. Wang, Y. J. et al. Reference Wang, Fan, Cawood, Ji, Peng and Chen2007a,b, Reference Wang, Fan, Zhang and Zhang2013; Lepvrier et al. Reference Lepvrier, Faure, Van, Vu, Lin, Trong and Hoa2011; Faure et al. Reference Faure, Lepvrier, Nguyen, Vu, Lin and Chen2014, Reference Faure, Lin, Chu and Lepvrier2016a,b; Qiu, L. et al. Reference Qiu, Yan, Zhou, Arndt, Tang and Qi2014, Reference Qiu, Yan, Tang, Arndt, Fan, Guo and Cui2015a,b, Reference Qiu, Yan, Tang, Wang, Yang, Wang and Tang2016, Reference Qiu, Yan, Yang, Wang, Tang and Ariser2017). The Triassic magmatism is characterized by voluminous felsic intrusions that are distal from continental margins and occur as dispersed batholiths and sporadic plutons within the SCB (Fig. 1; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Fan, Cawood, Ji, Peng and Chen2007a,b; Qiu, L. et al. Reference Qiu, Yan, Zhou, Arndt, Tang and Qi2014). However, this region is free of volcanic rocks and mafic intrusions associated with the Indosinian orogeny, barring several contentious tuffaceous rocks (e.g. Yao et al. Reference Yao, Ji, Wang, Liu, Wu, Wu, Zhang and Wang2010; Blanchard et al. Reference Blanchard, Rossignol, Bourquin, Dabard, Hallot, Nalpas, Poujol, Battail, Jalil, Steyer, Vacant, Veran, Bercovici, Dize, Paquette, Khenthavong and Vongphamany2013; Qiu et al. Reference Qiu, Yan, Zhou, Gao, Tang and Barnes2015b).

The Youjiang fold-and-thrust belt is located within the southwestern SCB and includes nappes that extend into Vietnam (Fig. 1; Lepvrier et al. Reference Lepvrier, Faure, Van, Vu, Lin, Trong and Hoa2011; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Cawood, Du, Huang and Hu2012; Faure et al. Reference Faure, Lepvrier, Nguyen, Vu, Lin and Chen2014). The oldest units in the basin are Cambrian–Ordovician shales and calcareous rocks that crop out within a series of c. 50 km long superimposed anticlines (Fig. 1). These oldest units are interbedded with rift-associated basalt and diabase units, and are overlain by Lower to Middle Devonian siltstone, sandstone and shale (BGMRGX, 1985; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Cawood, Du, Huang and Hu2012; Qiu et al. Reference Qiu, Yan, Ren, Cao, Tang, Guo, Fan, Qiu, Zhang and Wang2018). The Youjiang Basin hosts a 7 km thick sequence of upper Proterozoic to Middle Triassic sediments (Figs 1, 2; Lehrmann et al. Reference Lehrmann, Enos, Payne, Montgomery, Wei, Yu, Xiao and Orchard2005, Reference Lehrmann, Pei, Enos, Minzoni, Ellwood, Orchard, Zhang, Wei, Dillett, Koenig, Steffen, Druke, Druke, Kessel and Newkirk2007; Galfetti et al. Reference Galfetti, Bucher, Martini, Hochuli, Weissert, Crasquin-Soleau, Brayard, Goudemand, Bruehwiler and Guodun2008; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Cawood, Du, Huang and Hu2012) that were overthrust by Palaeozoic sedimentary rocks (Lepvrier et al. Reference Lepvrier, Faure, Van, Vu, Lin, Trong and Hoa2011; Faure et al. Reference Faure, Lepvrier, Nguyen, Vu, Lin and Chen2014). The occurrence of Lower and Middle Triassic clastic sediments, as well as a regional unconformity, indicates a transition from Palaeo-Tethyan subduction to SCB–Indochina collisional tectonics that led to the Youjiang Basin becoming a foreland basin associated with the Indosinian orogen during Middle Triassic time (Yang et al. Reference Yang, Cawood, Du, Huang and Hu2012; Qiu et al. Reference Qiu, Yan, Tang, Wang, Yang, Wang and Tang2016, Reference Qiu, Yan, Yang, Wang, Tang and Ariser2017).

Figure 2. (a) Geological map of the Badu anticline within the Youjiang Basin (BGMRGX, 1985; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Yan, Qiu, Chen, Mu and Wang2018) and (b) cross-section showing the relationship between Phanerozoic units and diabase dykes within the Badu anticline (BGMRGX, 1992).

The diabase units in the Badu anticline occur as a series of arc-shaped E–W-trending intrusions (Fig. 2a). The unmetamorphosed early-stage sills were emplaced into upper Palaeozoic carbonate and clastic rocks and crop out over an area up to 20 km long and 0.5–2.0 km wide. Late-stage diabase sills are also common within sedimentary units from Devonian and Carboniferous mudstones to Lower Triassic carbonates. From west to east, the Badu diabase is divided into the Triassic Pingle sill and the Jurassic Bashuang sill (BGMRGX, 1992). The diabase units range in width from several to hundreds of metres and locally show concentric weathering features (Fig. 3). Cross-cutting relationships, textural characteristics and mineral assemblages identified during detailed 1:50000 scale field mapping in the 1990s enabled the division of these units into early and late diabase sills, but the absolute age of the diabase has not been constrained to date (BGMRGX, 1992). In addition, an approximately E–W-striking, arcuate high-angle normal fault system indicates that thrusting within the western and eastern parts of this region displaced the older diabase units, whereas the younger diabase units were emplaced into these older units along this fault system. The other NW–SE- or NE–SW-striking, kilometre-scale normal and strike-slip faults cross-cut and offset the diabase and older faults in this region, representing the youngest period of faulting within the Badu anticline (Fig. 2).

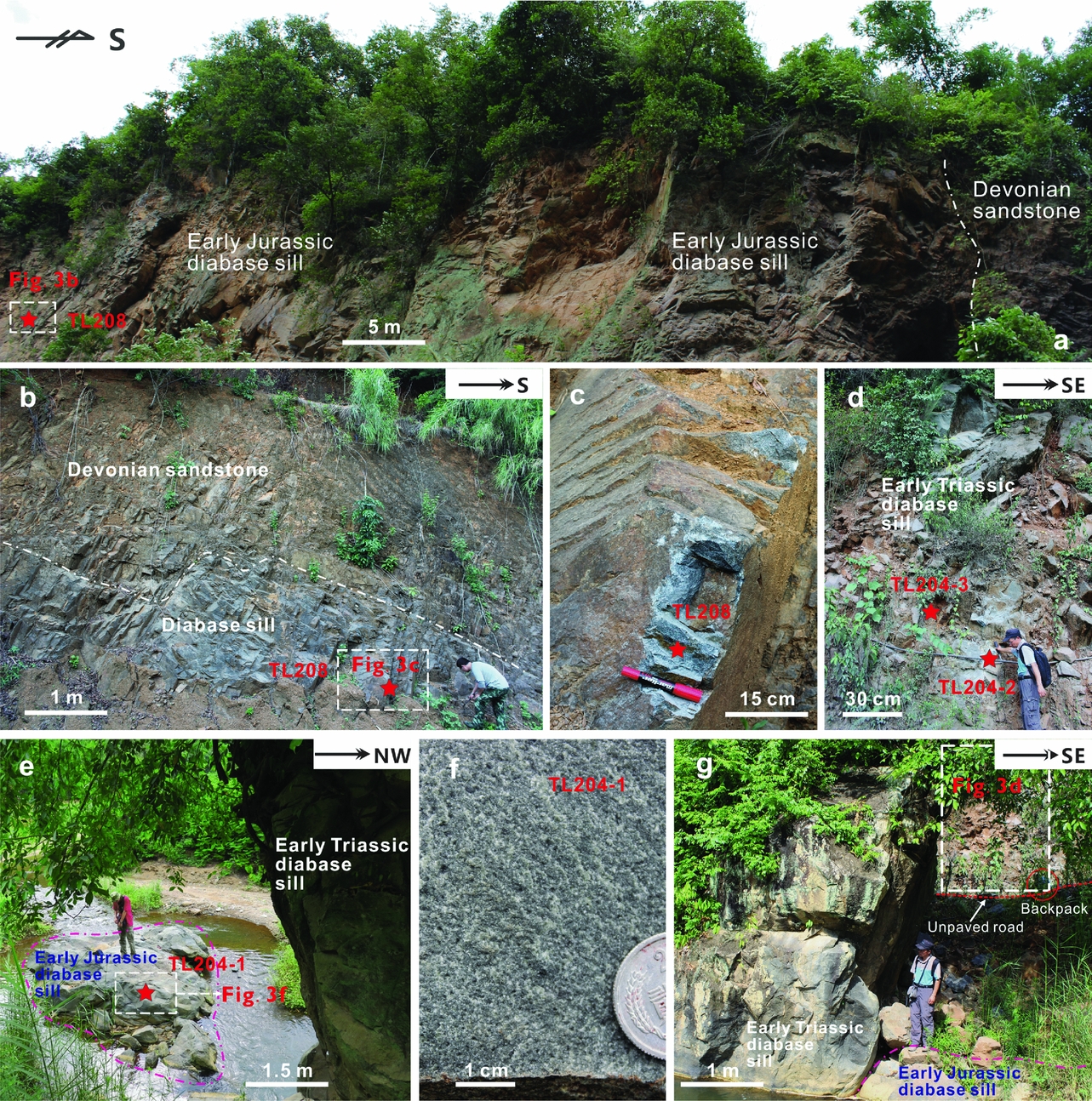

Figure 3. Field photographs showing representative samples of diabase sills within the Youjiang fold-and-thrust belt. (a, b) Early Jurassic diabase sill intruded into Devonian sandstone (TL208), (c) detailed view of a diabase sill (TL208), (d–g) late-stage diabase sill (TL204-1) intruding an early-stage diabase sill (TL204-2 and-3) exposed within a riverbank (viewed from opposite directions), and (f) late-stage diabase sill shown in detail (TL204-1). Sample locations are shown in Figure 2.

3. Sampling and analytical methods

Samples were collected from the Badu anticline of the Youjiang fold-and-thrust belt (Fig. 2). Diabase sills were sampled for zircon laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) U–Pb analysis. Samples TL204-1, TL204-2 and TL204-3 were collected from a section near a tributary of the Tuoniang River, ~2 km southwest of the village of Badu (Figs 2, 3). Sample TL204-1 is from a late diabase sill, and samples TL204-2 and TL204-3 are from an early diabase sill (Fig. 3). Samples TL204-2 and TL204-3 are referred to as early-stage diabase sills (labelled as Triassic in Fig. 1) in the following discussion. Sample TL208 was collected from a ~300 m thick diabase sill in the southern part of Bashuang village (Figs 2, 3). Sample TL209 was collected from a second diabase sill located ~1 km to the east of this village (Figs 2, 3). Samples TL204-1, TL208 and TL209 are referred to as late-stage diabase sills (labelled as Jurassic in Fig. 1) in the following discussion. Geological mapping (BGMRGX, 1992; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Yan, Qiu, Chen, Mu and Wang2018) indicates that samples TL204-2 and TL204-3 formed during the early stages of mafic magmatism, whereas samples TL204-1, TL208 and TL209 formed during the later stages. Consequently, we have grouped these samples when plotting U–Pb ages, determining Ti-in-zircon temperatures and calculating the magma oxygen fugacity.

3.a. Petrographic description

Early-stage diabase samples (TL204-2 and 204-3) have subophitic textures (Fig. 4) and are dominated by plagioclase, orthopyroxene and clinopyroxene. Lath-shaped plagioclase forms ~45 vol.% of these samples, which also contain about 20 vol.% clinopyroxene, 20 vol.% orthopyroxene, 10 vol.% hornblende and 5 vol.% olivine. These minerals are commonly altered to chlorite, biotite and hornblende, and the samples also contain accessory zircon, rutile and sulfide minerals.

Figure 4. Photomicrographs showing representative examples of diabase sills within the Badu anticline. Abbreviations: Cpx – clinopyroxene; Ol – olivine; Opx – orthopyroxene; Pl – plagioclase.

Late-stage diabase samples (TL204-1, TL208 and TL209) have ophitic to subophitic textures with varying crystal sizes (Fig. 4). Sample TL204-1 contains smaller crystals of plagioclase and clinopyroxene, whereas samples TL208 and TL209 contain lath-shaped plagioclase as well as millimetre-sized anhedral clinopyroxene and orthopyroxene. Plagioclase forms up to 60 vol.% of these samples and is commonly altered to chlorite and clay minerals. The clinopyroxene and accessory olivine within these samples is altered to hornblende, biotite and chlorite, and these diabase units also contain accessory zircon, baddeleyite, pyrite, arsenopyrite and pyrrhotite.

3.b. Zircon LA-ICP-MS U–Pb analysis

Zircons were separated by conventional density and magnetic techniques before crystals free of major fractures and visible inclusions were handpicked, mounted in epoxy resin and polished to expose the zircon centres. Cathodoluminescence (CL) images were obtained using a JSM 6510 electron microprobe with a Gatan mini detector to characterize the internal structures of the zircon grains and select sites for analysis (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Representative cathodoluminescence (CL) images of zircons showing the sites of U–Pb analyses. The majority of zircons were inherited xenocrysts and are therefore not shown in the CL images in order to focus on the youngest mafic magmatism. White circles indicate the locations of 206Pb/238U analytical spots using a laser diameter of 30 μm.

Zircon U–Pb and trace-element analyses were undertaken by LA-ICP-MS at the Mineral Laser Microprobe Analysis Laboratory (Milma Lab), China University of Geosciences, Beijing, China (CUGB) and at the In-situ Mineral Geochemistry Lab, Ore Deposit and Exploration Centre (ODEC), Hefei University of Technology, Hefei, China. These analyses used an Agilent 7900 ICP-MS instrument coupled to a New Wave 193UC excimer laser ablation system. The ICP-MS system was optimized by line scanning at a rate of 5 μm/s and using a spot size of 35 μm while also ensuring low ThO/Th (<0.2%) and Ca2+/Ca+ ratios (<0.7%; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Ge, Ning, Nie, Zhong, Zhou and White2017).

A 91500 standard zircon and a NIST 610 standard glass were used for external calibration for U–Pb ages and trace-element concentrations, respectively, with GJ-1, NIST 610 or 91500 standard zircons analysed after every ten unknowns for quality control. Each block of five unknowns was followed by the analysis of two standards, with each analysis beginning with a 20–25 s blank followed by a further 40 s of analysis time after the laser was switched on. These analyses used a 30 μm diameter laser beam with an 8 Hz repetition rate and an energy density of 2 J/cm2. Helium was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 0.85 l/min. This gas carried ablated aerosols out of the sample chamber before mixing with Ar gas and being carried to the plasma torch. Time-dependent drifts of U–Th–Pb isotopic ratios were corrected using a linear interpolation (with time) for every five analyses according to variations in the composition of the 91500 standard zircon compared to the U–Th–Pb isotopic ratios reported by Wiedenbeck et al. (Reference Wiedenbeck, Alle, Corfu, Griffin, Meier, Oberli, Vonquadt, Roddick and Speigel1995). Zircon trace-element compositions were calibrated against the NIST 610 standard using 29Si for internal standardization. Common Pb was corrected following Andersen (Reference Andersen2002). Any uncertainties in the preferred composition of the external 91500 standard zircon were propagated to the final results presented in this study. Offline data processing was performed using ICPMSDataCal software (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Hu, Gao, Gunther, Xu, Gao and Chen2008). All concordia diagrams and weighted mean calculations were made using Isoplot version 4.0 (Ludwig, Reference Ludwig2003). Geochemical diagrams were constructed using the CGDK+ZOFIT software package (Corel Geological Drafting Kit; Qiu, J. T. et al. Reference Qiu, Song, Jiang, WU and Dong2013a, Reference Qiu, Li, Santosh and Yu2014a; for more details, see Qiu & Qiu, Reference Qiu and Qiu2016).

3.c. Ti-in-zircon thermometry and magma oxygen fugacity

Zircon crystallization temperatures were determined using a revised Ti-in-zircon thermometry approach (Watson, Wark & Thomas, Reference Watson, Wark and Thomas2006; Ferry & Watson, Reference Ferry and Watson2007). The fact that rutile is absent means that the melts that formed the units in the study area were undersaturated in titanium (Ferry & Watson, Reference Ferry and Watson2007). In addition, the absence of quartz as individual crystals and within the matrix indicates that these samples formed from silica-unsaturated melts, yielding an aSiO2 value of 0.5. The presence of Fe–Ti minerals (ilmenite and titanite; BGMRGX, 1992) and the calculated titanium activities of similar phase assemblages yield a conservative estimate of the aTiO2 value of the system to be 0.6 (Watson, Wark & Thomas, Reference Watson, Wark and Thomas2006; Hiess et al. Reference Hiess, Nutman, Bennett and Holden2008).

The fact that the zircon structure can incorporate Ce4+ means that Ce anomalies (δCe) can provide qualitative estimations of magma oxidation states. The calibration of Trail, Watson & Tailby (Reference Trail, Watson and Tailby2011, Reference Trail, Watson and Tailby2012) can be used to estimate oxygen fugacity values for magmatic melts. The calculation of δCe values based on interpolation between La and Pr is often affected by large analytical uncertainties, low concentrations of La and Pr within zircons, and the presence of small light rare earth element (LREE)-rich mineral inclusions within zircons (Qiu, J. T. et al. Reference Qiu, Li, Santosh and Yu2014a; Qiu & Qiu, Reference Qiu and Qiu2016). Here, we use lattice strain models that quantify the relationship between logarithmic partition coefficients and ionic radii (Blundy & Wood, Reference Blundy and Wood1994) to calculate of δCe values using Gd and Lu and Nd and Sm, elements that are present at higher concentrations than La and Pr in zircon, an approach that yields more reliable estimates of Ce anomalies and associated oxygen fugacities (Trail, Watson & Tailby, Reference Trail, Watson and Tailby2011, Reference Trail, Watson and Tailby2012; Qiu et al. Reference Qiu, Yu, Santosh, Zhang, Chen and Li2013b). Detailed descriptions of this approach are given in Qiu & Qiu (Reference Qiu and Qiu2016).

4. Analytical results

4.a. Zircon U–Pb ages

The zircon U–Pb data are plotted in concordia and age probability diagrams (online Supplementary Material Table S1 available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo; Fig. 6). The majority of the zircons are inherited xenocrysts and only a small amount of these have igneous origins (Fig. 5). The youngest populations of zircons have igneous textures and characteristics, whereas the other larger and more rounded zircons are inherited (Fig. 5). The fact that the mafic diabase did not yield enough igneous zircons and that the majority of the zircons are inherited means that we grouped samples during this study to generate reasonable and statistically meaningful crystallization ages. As shown on the geological map (Fig. 1), samples TL204-1, TL204-2 and TL204-3 are from a section around the TL204 locality. Previous detailed geological mapping (1:50000 scale; BGMRGX, 1992) identified cross-cutting relationships, textural characteristics and mineral assemblages that allow all of these units to be classified as an early diabase unit (TL204-2 and TL204-3) and late diabase unit (TL204-1). As such, the youngest igneous zircon populations from samples TL204-2 and TL204-3 are combined to yield a U–Pb age for the early diabase phase of magmatism (Fig. 6a, b). Equally, the fact that samples TL204-1, TL208 and TL209 all formed during the same stage of late diabase magmatism means that we grouped the youngest igneous zircon populations from these samples to yield a single U–Pb age (Fig. 6c, d).

Figure 6. Zircon U–Pb concordia and weighted average diagrams for the Badu diabase.

A total of 58 zircons from the late diabase sill were separated from samples TL204–1, TL208 and TL209 (Fig. 3). The majority of the zircons have Th/U ratios of 0.17–1.61 (barring analyses TL204-1-16 and TL208-23) and have oscillatory zoning with inherited cores visible during CL imaging, indicating a magmatic origin. These samples also contain minor amounts of rounded zircons that most likely represent inherited xenocrysts. The zircons are 20–150 μm long with length/width ratios of 1:1 to 6:1 (Fig. 5). The majority of the zircons yield ages between 2762 Ma and 181 Ma with peaks at 347, 241 and 188 Ma, and lesser peaks at 1741, 1071 and 818 Ma (Fig. 6c, d). The age population is dominated by zircons with ages of c. 188 Ma.

A total of 28 analyses of zircons from the early diabase sill (samples TL204-2 and TL204-3) were undertaken during this study. These zircons have Th/U ratios of 0.16–1.90 and a minority of these grains have pyramidal and prismatic shapes and magmatic oscillatory zoning, with the majority containing inherited cores. They range in length from 30 to 150 μm, have length/width ratios from 1:1 to 5:1 (Fig. 5) and yield ages from 2436 to 243 Ma (Fig. 6a, b). The age spectra for this sample include a largest peak at 248 Ma and other peaks at 1877, 992, 669 and 370 Ma.

4.b. Zircon trace-element compositions

All of the young igneous zircons have trace-element patterns that are enriched in the heavy rare earth elements (HREEs) and depleted in the LREEs, with negative Eu and variably positive Ce anomalies. Some analyses yielded strongly enriched LREE or HREE compositions that are indicative of the influence of REE-rich inclusions within these zircons and as such were excluded from further discussion. The rest of the analyses of the igneous zircons from samples TL204-2 and TL204-3, and TL204-1, TL208 and TL209 yield ΣREE values of 453–1599 and 824–2655 ppm, respectively, with Ti concentrations of 3–16 and 4–32 ppm, respectively. These data are given in online Supplementary Material Table S2 available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo and are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Chondrite-normalized REE patterns for zircons from the Badu sills, normalized to the chondrite composition of Boynton (Reference Boynton and Henderson1984).

4.c. Ti-in-zircon thermometry and magma oxygen fugacity

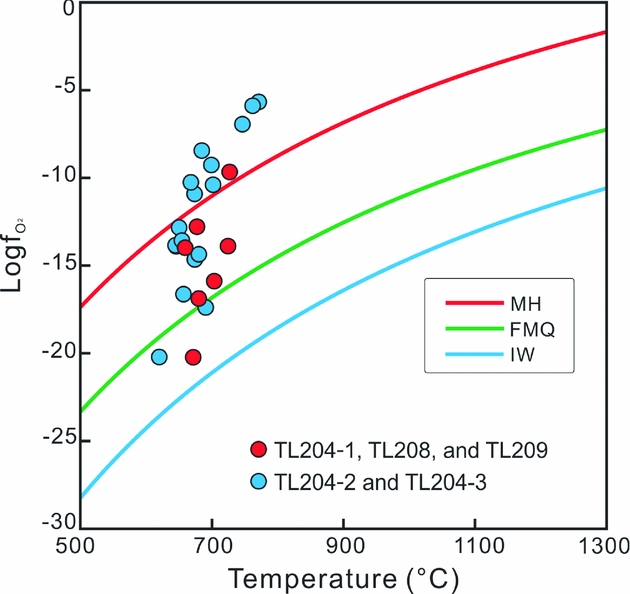

One analysis (TL204-2-6) yielded extremely high values of oxygen fugacity that are statistical outliers and were excluded from further discussion. The oxygen fugacity values obtained from the rest of the zircons from samples TL204-2 and TL204-3, and TL204-1, TL208 and TL209 range from ‒20 to ‒6 (average of ‒12) and ‒20 to ‒10 (average of ‒15), respectively. These values yield calculated mean magma oxidation states for the igneous zircon populations of FMQ +5 and FMQ +2, respectively (online Supplementary Material Tables S2 and S3 available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo).

5. Discussion

5.a. Emplacement age of the diabase

Previous whole-rock K–Ar dating and the presence of mineral assemblages similar to those found in Early Devonian basalts within the Badu anticline indicate that the diabase sills within the Lower Devonian units of the Tangding Formation were emplaced during Early Devonian time (BGMRGX, 1985, 1992). In comparison, the late diabase sills that cross-cut the early diabase sills and were emplaced into Lower Triassic carbonates with sedimentary clastic interlayers were thought to have formed either during Middle–Late Triassic or Jurassic times (BGMRGX, 1985, 1992). However, potential overprinting by widespread early and late Mesozoic tectonothermal events (e.g. the Indosinian and Yanshanian events; Wang, Y. J. et al. Reference Wang, Fan, Zhang and Zhang2013; Qiu, L. et al. Reference Qiu, Yan, Zhou, Arndt, Tang and Qi2014, Reference Qiu, Yan, Tang, Arndt, Fan, Guo and Cui2015a,b; Dong et al. Reference Dong, Zhang, Zhang, Cui, Chen, Zhang, Miao, Li, Shi, Li, Huang and Li2015) suggests that the K–Ar ages for these diabase units may be unreliable. As such, precise ages are necessary to constrain the timing of emplacement of these sills.

Zircon age populations and cross-cutting field relationships indicate that the diabase units within the Badu anticline formed during two stages of mafic magmatism in Early Triassic and Early Jurassic times. Excluding inherited xenocrysts, our zircon U–Pb dating of these diabase units indicates that: (1) the early sills that were emplaced into the Lower Devonian Tangding Formation yield a weighted U–Pb mean age of 249.2±2.0 Ma (youngest population; mean standard weighted deviation (MSWD) = 2.9, N = 18); and (2) the late sills that intruded the Triassic sills yield a weighted mean age of 187.1±3.3 Ma (youngest population; MSWD = 7.6, N = 12). The two youngest age peaks for all of the zircons occur at c. 190 Ma and c. 250 Ma, suggesting that this area records two stages of mafic magmatism. These zircons are igneous and the diabase sills that host these zircons were not emplaced into Upper Triassic units. Combining this with the presence of units with similar mineral assemblages and field mapping of the diabase within the Badu anticline (BGMRGX, 1992) suggests that the large volume of diabase sills within the Proterozoic units were emplaced at c. 250 Ma and c. 190 Ma.

Key magmatic provenance information can also be obtained from the trace-element compositions of the zircons. The c. 250 Ma and c. 190 Ma zircons have mean Th/U ratios of 0.90 (range of 0.24–1.90) and 0.69 (range of 0.23–0.95), respectively, indicating a magmatic origin (Th/U values >0.1 or 0.4; Hoskin & Ireland, Reference Hoskin and Ireland2000; Yakymchuk, Kirkland & Clark, Reference Yakymchuk, Kirkland and Clark2018). In addition, these youngest zircons are enriched in HREEs, depleted in LREEs and have variably positive Ce and apparent negative Eu anomalies, again supporting a magmatic origin (Hoskin & Ireland, Reference Hoskin and Ireland2000; Fig. 7). The c. 190 Ma zircon population has higher REE abundances (ΣREE = 824–2655 ppm, average of 1362 ppm) and flatter chondrite-normalized REE patterns than the c. 250 Ma zircons (ΣREE = 435–1599 ppm, average of 807 ppm), whereas the c. 250 Ma zircon population has smaller negative Eu anomalies and larger Pr anomalies than the c. 190 Ma zircon population (Fig. 7).

The c. 190 Ma zircon population yields higher zircon crystallization temperatures (659–726°C, average of 691°C) than the c. 250 Ma zircons (619–771°C, average of 683°C; Fig. 8; methods in Section 3.c). The c. 250 Ma zircon population also yields higher oxygen fugacities (‒20 to ‒6, average of ‒12 and FMQ +5) than the c. 190 Ma zircons (‒20 to ‒10, average of ‒15 and FMQ +2). This suggests that these two phases of mafic magmatism involved magmas derived from different sources and with different petrogenetic histories.

Figure 8. Zircon crystallization temperatures and magma oxygen fugacity during the formation of the Badu diabase. The fayalite–magnetite–quartz (FMQ), magnetite–haematite (MH), and iron–wüstite (IW) buffers are from Myers & Eugster (Reference Myers and Eugster1983). Filled circles indicate the youngest zircon populations.

5.b. Magma oxygen fugacity and origin of the diabase

Igneous rocks form in a range of tectonic settings under different magma oxygen fugacity conditions. Terrestrial igneous rocks have magma oxygen fugacity (f O2) values that range between the wüstite–magnetite (WM) buffer and the nickel–nickel oxide (NNO) +1 buffer, which are oxidizing conditions close to the FMQ buffer. The oxygen fugacity of igneous rocks erupted and intruded in island arcs is greater than NNO +1 (~FMQ +2), whereas those erupted and emplaced in non-arc settings are associated with f O2 conditions less than FMQ –1 (e.g. Christie, Carmichael & Langmuir, Reference Christie, Carmichael and Langmuir1986; Carmichael, Reference Carmichael1991; Lee et al. Reference Lee, Leeman, Canil and Li2005).

The Badu diabase formed in a non-arc setting (Qiu et al. Reference Qiu, Yan, Tang, Arndt, Fan, Guo and Cui2015a,b, Reference Qiu, Yan, Tang, Wang, Yang, Wang and Tang2016). If the diabase was generated directly from the mantle and underwent fractional crystallization then it should have formed under magma oxygen fugacity conditions similar to that of typical Hawaiian basalts (~FMQ +1; Jackson, Weis & Huang, Reference Jackson, Weis and Huang2012). However, our data indicate that the Badu diabase formed under ~FMQ +2.3 or ~FMQ +5.2 conditions that are typical of magmas generated in non-arc settings.

A positive correlation exists between zircon δ18O and Ce4+/Ce3+ (a proxy for f O2) values for rocks from the Lower Yangtze River belt (Liu, S. A. et al. Reference Liu, Li, He and Huang2010; Wang, F. Y. et al. Reference Wang, Liu, Li and He2013), indicating that the assimilation of oxidized components may increase the magma oxygen fugacity. However, Qiu & Qiu (Reference Qiu and Qiu2016) suggested that the assimilation of poorly oxidized components may not significantly increase magma oxygen fugacity. This means that the oxidation state of material assimilated by magmas also needs to be taken into consideration.

The abundant inherited zircons of the present study yield Proterozoic and Palaeozoic age peaks that indicate the magmas that formed the diabase units assimilated material derived from both basement and Phanerozoic cover sequence units. For example, the basalts from the basement rocks of the Yangtze Block yield an average oxygen fugacity value of FMQ +2.5 (Zhou, Zhao & Qi, Reference Zhou, Zhao and Qi2006; online Supplementary Material Fig. S1 available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo), which is 0.2 log units higher than the value of the Badu diabase (the ~190 Ma diabase sill, ~FMQ +2.3) and 1.5 log units higher than the values expected for typical Hawaiian basalts. This indicates that assimilation of this basement material resulted in an increase in the magmatic oxygen fugacity of the magmas that formed the Badu diabase.

5.c. Relationship between magmatism and metallogenesis

The Phanerozoic history of the SCB is dominated by the generation of a giant low-temperature metallogenic domain of ~500000 km2 in size, especially the Youjiang Au–As–Sb–Hg metallogenic province (e.g. Hu et al. Reference Hu, Su, Bi, Tu and Hofstra2002, Reference Hu, Chen, Xu and Zhou2017a,b; Hu & Zhou, Reference Hu and Zhou2012; Goldfarb et al. Reference Goldfarb, Taylor, Collins, Goryachev and Orlandini2014; Deng & Wang, Reference Deng and Wang2015; Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Zhou, Li, Zhao and Gao2017; Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Hu, Richards, Bi, Stern and Lu2017). The Youjiang Au–As–Sb–Hg province is located in the present study area and contains vein-type Sb, Hg and As deposits, and Carlin-type gold deposits that formed mainly during two episodes of mineralization at 230–190 Ma and 150–130 Ma (Pi et al. Reference Pi, Hu, Peng, Wu, Wei and Huang2016, Reference Pi, Hu, Xiong, Li and Zhong2017; Hu et al. Reference Hu, Chen, Xu and Zhou2017a,b; Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Hu, Richards, Bi, Stern and Lu2017). These epigenetic (~100–250°C) deposits are locally controlled by faults and are hosted by sedimentary rocks (Su et al. Reference Su, Heinrich, Pettke, Zhang, Hu and Xia2009). Hu et al. (Reference Hu, Chen, Xu and Zhou2017a,b) suggested that the Carlin-type gold deposits in this region were formed by the heating of meteoric water by magmas at depth in a process that generated a hydrothermal circulation system. These fluids mobilized metals from sedimentary rocks to form the Carlin-type gold deposits. However, little evidence of this magmatism has been identified to date, namely (1) c. 250 Ma diabase units that were emplaced into the southern fold-and-thrust belt and are interpreted to be a distal manifestation of the Emeishan mantle plume to the west (Zhou, Zhao & Qi, Reference Zhou, Zhao and Qi2006; Fan et al. Reference Fan, Zhang, Wang, Guo and Peng2008; Shellnutt et al. Reference Shellnutt, Zhou, Yan and Wang2008); and (2) Yanshanian (c. 90 Ma) and Indosinian (c. 215 Ma) granites associated with W–Sn polymetallic deposits within the southern and eastern parts of the basin (Liu, S. et al. Reference Liu, Su, Hu, Feng, Gao, Coulson, Wang, Feng, Tao and Xia2010; Feng et al. Reference Feng, Zeng, Zhang, Qu, Du, Li and She2011; Zhang, J. W. et al. Reference Zhang, Dai, Huang, Luo, Qian and Zhang2015). The Gejiu basalt is the only Indosinian magmatism identified to date within the southwestern SCB, and no Triassic intrusive rocks have been identified (Zhang, J. W. et al. Reference Zhang, Dai, Huang, Luo, Qian and Zhang2015). The identification of diabase in the Badu anticline is the first evidence of an Indosinian mafic intrusion in the southwestern SCB, and this supports Hu et al.’s (Reference Hu, Chen, Xu and Zhou2017a,b) metallogenic model of epigenetic deposits. In other words, the mantle-derived magmas that are represented by the Badu diabase were emplaced within the lower crust, providing heat to drive crustal anatexis and the subsequent exsolution of fluids derived from these magmas and the mixing of these fluids with heated meteoric water (e.g. Bonin, Reference Bonin2004).

Magma oxygen fugacity is also a key control on Cu–Mo–Au mineralization (e.g. Rowins, Reference Rowins2000). Previous research has linked ore assemblages to the oxidation states of melt or fluid systems (e.g. Ballard, Palin & Campbell, Reference Ballard, Palin and Campbell2002; Mengason, Candela & Piccoli, Reference Mengason, Candela and Piccoli2011; Richards, Reference Richards2011; Qiu & Qiu, Reference Qiu and Qiu2016), with Cu–Au-bearing granites conventionally being associated with oxidized magmas or highly oxidized fluid systems (e.g. Rowins, Reference Rowins2000; Qiu, J. T. et al. Reference Qiu, Li, Santosh and Yu2014a,b). The fact that the late-stage Badu diabase yields a wide range of oxygen fugacity values that are all higher than typical Hawaiian basalts but lower than the early-stage Badu diabase and basalts within the basement suggests that the ~250 Ma Badu diabase or basement rocks were assimilated by and thus contributed to the variations in the oxygen fugacity values of the late-stage magmas that hosted the gold deposits (Fig. 1; online Supplementary Material Fig. S1 available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo). This inference is supported by the recent discovery of the diabase-hosted Badu gold deposit in the late-stage diabase and the related Pingle and Gaolong gold deposits (Fig. 1; e.g. Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Wang, Wang, Wang and Qiu2012; Luo et al. Reference Luo, Wu, Li, Liao and Li2014; Li, P. et al. Reference Li, Pang, Wang, Li, Zhou, Lv and Ma2015), although more detailed future research is needed to link the oxygen fugacity status of these magmas to the metallogenesis in this region.

5.d. Tectonic implications

Zircon ages and compositions provide new constraints on the Triassic and Early Jurassic evolution of the southwestern SCB. The Triassic tectono-magmatic evolution of the Indosinian orogeny in Vietnam and the southwestern SCB was a consequence of the Middle Triassic collision between the Indochina Block and the SCB after the closure of the eastern Palaeo-Tethys Ocean (e.g. Lepvrier et al. Reference Lepvrier, Maluski, Tich, Leyreloup, Thi and Vuong2004; Metcalfe, Reference Metcalfe2013; Faure et al. Reference Faure, Lin, Chu and Lepvrier2016a,b). This collision occurred along the Song Ma/Song Chay suture (Wang, Y. J. et al. Reference Wang, Fan, Zhang and Zhang2013; Hu et al. Reference Hu, Du, Cawood, Xu, Yu, Zhu and Yang2014; Faure et al. Reference Faure, Lin, Chu and Lepvrier2016a,b). Both the structure and the sedimentary units in this region record the transition from subduction to collision during Middle Triassic time (Qiu et al. Reference Qiu, Yan, Tang, Wang, Yang, Wang and Tang2016, Reference Qiu, Yan, Yang, Wang, Tang and Ariser2017). Although volcanic rocks and mafic intrusions are not present within the southwestern SCB, this orogenic event is also recorded by the extensive intrusion of igneous rocks and deformation at c. 255–205 Ma and two peak stages of granitic magmatism at c. 238 Ma and c. 218 Ma (e.g. Wang, Y. J. et al. Reference Wang, Fan, Cawood, Ji, Peng and Chen2007a,b, Reference Wang, Fan, Zhang and Zhang2013; Qiu, L. et al. Reference Qiu, Yan, Zhou, Arndt, Tang and Qi2014, Reference Qiu, Yan, Tang, Arndt, Fan, Guo and Cui2015a,b). The present data for the c. 250 Ma mafic magmatism in this region suggests that this event was caused by post-flood-basalt extension related to the Emeishan mantle plume (Shellnutt et al. Reference Shellnutt, Zhou, Yan and Wang2008; Zhang, Z. et al. Reference Zhang, Mao, Saunders, Ai, Li and Zhao2009, Reference Zhang, Mao, Wang and Pirajno2015) or rollback of the subducting Palaeo-Tethyan slab. A comparison of ages with large-scale Triassic granitic magmatism in the SCB and Indochina suggests that the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic mafic magmatism in this region was generated by regional extension and lithospheric thinning after the SCB–Indochina collision, potentially marking the collapse of the Triassic Indosinian orogen (Fig. 9). In addition, mantle-derived magmas emplaced within the lower crust and associated crustal anatexis driven by heat from these magmas played a key role during post-collisional tectonism but ceased during the transition to a within-plate tectonic regime (Bonin, Reference Bonin2004; Brown, Reference Brown2010). For example, the N–S-trending extension and rifting associated with the genesis of carbonatitic magmas within the Tibetan Plateau is thought to have been related to either mantle flow (Yin & Harrison, Reference Yin and Harrison2000), a change in the stress field (Murphy, Saylor & Ding, Reference Murphy, Saylor and Ding2009) or collision-induced rotation (Wang, Y. J. et al. Reference Wang, Fan, Zhang and Zhang2013) during Indo-Asia collision. This means that the Triassic diabase units of the present study were probably derived from partial melting of lithospheric upper mantle material with later crustal contamination during the transition from post-collisional to within-plate tectonic regimes (Fig. 9).

Figure 9. Tectonic model of the post-orogenic extensional origin of the Badu diabase (modified after Wells et al. Reference Wells, Hoisch, Cruz–Uribe and Vervoort2012; Qiu, L. et al. Reference Qiu, Yan, Zhou, Arndt, Tang and Qi2014). (a) Late Permian to Early Triassic diabase units with a peak age of c. 250 Ma were generated by post-flood-basalt extension associated with the Emeishan mantle plume or rollback of the subducting Palaeo-Tethyan slab. (b) Early Jurassic diabase intrusions with an age peak at ~190 Ma were derived during the Late Triassic transition from post-orogenic extension to within-plate tectonism.

The western extension of the Neoproterozoic Jiangshao suture between the Yangtze and Cathaysia blocks remains controversial as a result of the presence of a thick Phanerozoic cover sequence (Qiao, Wang & Li, Reference Qiao, Wang and Li2015; Guo & Gao, Reference Guo and Gao2018), especially within the Youjiang Basin. Inherited zircon xenocrysts derived from partial melting of the basement and the host rocks of these ascending magmas provide important insights into provenance and magma sourcing. Inherited Proterozoic to Permian zircons within the diabase samples analysed during this study have subordinate age peaks at c. 2450, 1750 and 800 Ma (online Supplementary Material Fig. S2 available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo). The age distribution of these inherited zircons is similar to that of Precambrian detrital zircons (dominated by 1850 and 800 Ma peaks) from the Yangtze Block (Qiu, L. et al. Reference Qiu, Yan, Zhou, Arndt, Tang and Qi2014, Reference Qiu, Yan, Tang, Arndt, Fan, Guo and Cui2015a,b; Qiao, Wang & Li, Reference Qiao, Wang and Li2015), but is different from that of Precambrian detrital zircon crystals (with a 930 Ma peak) from the western Cathaysia Block (Qiao, Wang & Li, Reference Qiao, Wang and Li2015). This suggests that the western segment of the Jiangshao suture zone is located to the south of the Badu anticline (Fig. 1; online Supplementary Material Fig. S2 available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo).

6. Conclusions

The new data presented in this study allow the following conclusions to be made.

(1) The Badu diabase complex in the Youjiang fold-and-thrust belt was emplaced in two stages at c. 190 Ma and c. 250 Ma.

(2) The Early Triassic mafic magmatism was most likely caused by post-flood-basalt extension of the Emeishan large igneous province, whereas the Early Jurassic mafic magmatism was triggered by post-orogenic extension.

(3) The diabase within the Badu anticline provides evidence of Indosinian mafic magmatism within the southwestern SCB and supports an epigenetic model for mineralization in this region.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Basic Research Programme of China (973 Programme Grant No. 2014CB440903) and the NSF of China (Grants 41672216 and 41702207). We thank Chen-Guang Xu and Hong-Xu Mu for assistance during zircon U–Pb lab work and data processing. We also acknowledge the Editor, Professor Olivier Lacombe, and two anonymous reviewers for constructive comments that helped to improve the manuscript.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756818000493