I thought I was black for about three years. I felt like there was a black poet trapped inside me, and [‘The Jungle Line’] was about Harlem – the primitive juxtaposed against the Frankenstein of modern industrialization; the wheels turning and the gears grinding and the beboppers with the junky spit running down their trumpets. All of that together with that Burundi tribal thing was perfect. But people just thought it was weird.

Art is short for artificial. So, the art of art is to be as real as you can within this artificial situation. That’s what it’s all about. That’s what art is! In a way, it’s a lie to get you to see the truth.

Joni Mitchell has always been weird, even by her own account. Personifying as well as versifying the tensions, contradictions, and affinities between the footloose and the fenced-in that is a main theme running through her work, she has remained one of pop music’s enduring enigmas despite over five decades in the music business.3 By turns, she has described herself or been characterised by others as an idiosyncratic singer-songwriter, the ‘consummate hippy chick’, ‘Annie Hall meets urban cowgirl’, the ‘babe in bopperland, the novice at the slot machines, the tourist, the hitcher’, a poet, a painter, a reluctant yet ambitious superstar.4 Who, in fact, are we confronting in a ‘self-confessional singer-songwriter’ who withholds her ‘real’ name?

Born Roberta Joan Anderson to parents preparing for a son named Robert John on November 7, 1943, the artist better known as Joni Mitchell concocted her name through a combination of youthful pretensions and her first, brief marriage. Eschewing Roberta, Joan became Joni at the age of thirteen because she ‘admired the way [her art teacher, Henry Bonli’s] last name looked in his painting signatures’.5 Her marriage in June 1965 to older folk singer, Chuck Mitchell, when she was a twenty-one-year-old unwed mother, lasted less than two years yet she has continued to use Mitchell publicly for more than five decades (further, published accounts indicate she is called ‘Joan’ by intimates in her everyday life).6 Her acts of performative alterity reflect a lifelong interest in exploring the possibilities as well as testing the limits of identity claims, performed years before she harboured any concrete thoughts regarding a professional music career.

Her identity play does not stop with name games. In 1976, on her way to a Halloween party thrown by Peter and Betsy Asher, Mitchell was inspired by ‘this black guy with a beautiful spirit walking with a bop’, who, while walking past her, declared, ‘Lookin’ good, sister, lookin’ good!’ Mitchell continues, ‘I just felt so good after he said that. It was as if this spirit went into me. So I started walking like him’.7 Stopping at a thrift store on the way to the party, she transformed herself into a figure her party companions assumed was a black pimp. Not simply a ‘black man at the party’, Claude-Art Nouveau was a ‘pimp’, a detail that Miles Grier considers in a thoughtful essay on Mitchell’s use of black masculinity to earn ‘her legitimacy and authority in a rock music ideology in which her previous incarnation, white female folk singer, had rendered her either a naïve traditionalist or an unscrupulous panderer’.8 Importantly, Grier notes that Mitchell achieves this without having to pay full freight on the price of living in black skin or, I might add, the ease with which she can revert back to whiteness and its privileges, unlike avowed black-skinned models such as Miles Davis.

Entering the party unrecognised, Mitchell was delighted by her ruse and the masked anonymity it offered her, connecting her to the ways the burnt-cork mask of blackface minstrelsy, including its cross-gendered performance practices, allowed the predominantly working-class Irish male performers of the nineteenth century to perform in public in ways otherwise prohibited by bourgeois norms (see Figure 18.1).9 Despite (mis)representing ‘themselves’, blackface was a way for black performers to appear on public stages in the nineteenth century. As with those black minstrels, Art Nouveau was a way to be in public without having to expose herself – a veil, to spin Du Bois’ metaphor, which allowed Mitchell to hide in plain sight.

Figure 18.1 Joni Mitchell as ‘Claude’ at the Ashers' Halloween party, 1976.

This blackface drag persona is said to be so important to Mitchell that her four-volume autobiography (as yet unpublished) purportedly begins with the words, ‘I was the only black man at the party’.10 As a female rock musician, Mitchell’s responses to music industry inducements and demands were meant to defend her status as an artist without attracting pre-emptive gendered (dis)qualification. Her creative work, which not only fused musical genres but also synthesised music, painting, and verse, is complicated further by being caught within the contradictions of her (trans)gendered and (cross)racialist adoptions, co-optations, and appropriations.

Additionally, Mitchell invites interpreting her creative work as antagonistic to the notion of an art and popular culture opposition by challenging the music industry’s view of her creative output as pop commodity (while unapologetically accepting its material rewards) and simultaneously using jazz, visual art, and poetics as high cultural practices and discourses through which she argues she is more properly understood. Mitchell admitted to Mary Dickie, ‘I’m a fine artist working in the pop arena. I don’t pander; I don’t consider an audience when I work; I consider the music and the words themselves, more like a painter’.11 It is another question, of course, of whether the literati view her work in the same way they understand the work of, for example, Bob Dylan (an artist whose public name and persona reveal little of the ‘real’ Robert Zimmerman yet has not faced the same criticisms that Mitchell has encountered regarding inauthenticity; indeed, he is often praised for his chimerical persona), Jean-Michel Basquiat, Laurie Anderson, or Kara Walker, artists who have straddled a similar popular/art divide. Mitchell navigated the troubled waters between autonomous art tendencies and more mundane commercial considerations, plying the waves between high art aesthetics and a popular music career. Importantly, Mitchell accomplished this partially on the backs of black bodies, including her own in blackface drag – a figure of shadows and light.

On one hand, Mitchell often speaks somewhat obliviously to the hierarchical nature typically implied between the museum and the nightclub – as if ‘good pop’ such as hers easily transcends such demarcations. On the other hand, Mitchell’s categorisation of her music as a ‘popular art music’ questions the masculinist orientation of aesthetic values, which valorises certain values (intellectual rigor, discipline, technical virtuosity) while concurrently ‘feminising’ and devaluing others (emotional capaciousness, delicate or sensitive sensibilities, intuitive spontaneity).

As noted in the second epigraph to this chapter, Mitchell has used ‘art as artifice’ as a means to convey and express emotional and intellectual truth(s). But she also recognises its double-edged utility. In a 1979 Rolling Stone interview, Mitchell proclaimed,

People get nervous about that word. Art. They think it’s a pretentious word from the giddyap. To me, words are only symbols, and the word “art” has never lost its vitality. It still has meaning for me. Love lost its meaning to me. God lost its meaning to me. But art never lost its meaning. I always knew what I meant by art.12

Mitchell’s self-conscious merging of Romantic ideals of the artist as autonomous creator coupled to Modernist conceptions of art’s role in disrupting social norms begs questions about the relationship between authenticity and artifice in her work. Placing her internal black junkie poet musician in a space of art as artifice, as ‘the lie that gets us to see the truth’, is part of a larger programme that complicates easy accusations of minstrelsy, but it does not designate her blackface performances ‘innocent’ either.

Lady of the Canyon

Mitchell’s gender positioning is illustrated by the distance between her public persona as produced through promotional campaigns and her efforts to define herself as an artist. Mitchell had the good fortune to have published songs under her own name for a publishing company in which she was an owner prior to signing with Reprise, a record label originally created as a vanity label for Frank Sinatra. Notably, in addition to retaining her publishing rights, she was granted total artistic control, including choice of album artwork and repertoire, from her debut recording.

She evinced little control over her promotional campaigns, however. Mitchell’s image became deeply imbricated within the somewhat clumsy yet effective overlapping of the discursive regimes of the counterculture and marketing departments at record labels; in no small part due to music industry employees often identifying record labels as countercultural in some fashion. An advertisement in Rolling Stone for her third release, Ladies of the Canyon (Reprise 1970), can serve as an example of the intersecting ways in which the music industry and the counterculture framed Mitchell as an authentic ‘hippie chick folkie singer-songwriter’. The ad describes Amy, a twenty-three year old ‘quietly beautiful’ woman, as despondent because her recently departed boyfriend is moving quickly to marry a fellow employee at Jeans West, a well-known denim clothing store at the time. She begins to feel better when a grocery delivery boy, Barry, compliments her collage of Van Morrison images. Offering him a drink of ‘Constant Comment [tea] with orange honey mixed in’, Barry offers Amy, in return, to smoke a joint (marijuana cigarette) with her and, noticing her ‘far out’ stereo system, the opportunity to listen to a recent purchase, which just happens to be Joni Mitchell’s latest recording, Ladies of the Canyon. As they both became ‘quite mellow indeed’, Amy begins to feel better because she hears in Mitchell a sense that ‘there was someone else, even another canyon lady, who really knew’ her situation, easing her sense of painful isolation.13

This advertisement articulated the merging of consumerist culture signifiers (Jeans West, Constant Comment, stereo components) with countercultural ones (Van Morrison, marijuana, Joni Mitchell) indicating how, by obscuring the fact that this narrative is actually an advertisement for their new commercial release, Reprise’s publicity department hoped to market Ladies of the Canyon as a recording for young listeners who were similarly inclined to create their own artwork, listen to other countercultural artists (besides Van Morrison, Neil Young plays an important role in the advertisement; not surprisingly, all were Warner Brothers artists at the time), and lead lives wherein ‘alternative consumer culture’ was not an oxymoron or contradiction.

Reprise ran another advertising campaign in the early 1970s, revealing the role gender and sexuality performed in marketing Mitchell at the time by declaring ‘Joni Mitchell Takes Forever’, ‘Joni Mitchell is 90 Per Cent Virgin’, and ‘Joni Mitchell Finally Comes Across’. Recalling her career trajectory, Mitchell revealed that

[b]y the time I learned guitar, the woman with the acoustic guitar was out of vogue; the folk boom was kind of at an end, and folk-rock had become fashionable, and that was a different look. We’re talking about a business [in which the] image is, generally speaking, more important than the sound, whether the business would admit it or not.14

While Mitchell recognised the roles gender and image played in the popular music market, she rejected feminism: ‘I was never a feminist. I was in argument with them. They were so down on the domestic female, the family, and it was breaking down. And even though my problems were somewhat female, they were of no help to mine’.15 Reading feminism as anti-men more than pro-women, Mitchell explicitly positioned her musicking as androgynous: ‘For a while it was assumed that I was writing women’s songs. Then men began to notice that they saw themselves in the songs, too. A good piece of art should be androgynous. I’m not a feminist. That’s too divisional for me’.16 Women artists, she asserts, do not necessarily share aesthetic or musical affinities and therefore music should be evaluated without regard to the gender of its producer(s). Yet, her play for ‘androgynous art’ echoes the liminal space her music occupies – neither female nor male, Mitchell grounds her music in the space spanning genders. In a recent interview, Mitchell responded to a question about her image as ‘hippie folk goddess’ sardonically:

Well, we need goddesses but I don’t want to be one. Hippie? I liked the fashion show and I liked the rainbow coalition but most of the hippie values were silly to me. Free love? Come on. No, it’s a ruse for guys. There’s no such thing. Look at the rap I got that was a list of people whose path I crossed. In the Summer of Love, they made me into this ‘love bandit’. In the Summer of Love! So much for ‘free love’! Nobody knows more than me what a ruse that was. That was a thing for guys.17

A ‘Hollywood’s Hot 100’ spread in the 3 February 1972 issue of Rolling Stone displayed her name surrounded by lips with arrows connecting her to various male musicians, represented with simple boxes framing their names – no lips, alas, for male musicians. The previous year, the magazine listed her as ‘Old Lady of the Year for her friendships with David Crosby, Steve Stills, Graham Nash, Neil Young, James Taylor, et al.’. In the ‘Hot 100’ graphic (see Figure 18.2), David Crosby, James Taylor, and Graham Nash share images of a halved heart in separate connections to Mitchell’s lips. Mitchell is one of four females listed on the page though the only one with a special graphic image and given an equivalent ‘star billing’ position to the male musicians.18 Reflecting on it over twenty years later, Mitchell admitted, ‘[Rolling Stone’s chart] was a low blow [and] made me aware that the whore/Madonna thing had not been abolished by that experiment’.19

Figure 18.2 ‘Hollywood’s Hot 100’ Rolling Stone 3 February, 1972.

Yet, as Mitchell related to Cameron Crowe:

If I experience any frustration, it’s the frustration of being misunderstood. But that’s what stardom is – a glamorous misunderstanding ... I like the idea that annually there is a place where I can distribute the art that I have collected for the year. That’s the only thing that I feel I want to protect, really. And that means having a certain amount of commercial success.20

Acknowledging the contradictory pressures and privileges of commercial success, codified within her conflicted triangulation of artistic experimentation, mass popularity, and financial success, Mitchell’s artistic and commercial ‘independence’ is not based on a feminist agenda but on the claims to an art space ‘beyond’ the considerations of gender. Disavowing ‘the lie’ of the feminist movement, she argues that even well-meaning assessments that privilege women musicians’ expressive qualities miss too much, replying with a question of her own:

Do you think [the listening public] accepts [emotional expression] from a woman [as opposed to a man]? I don’t know. The feedback that I get in my personal life is almost like, ‘You wanted it, libertine!’ I feel like I’m in the same bind. That’s not going to stop me, I’m still going to do it but I don’t feel like I have the luxury [to openly express myself] because of my gender ... I wouldn’t go putting it into a gender bag, at all.21

Mitchell’s claims for artistic authority rest on a ‘gender-blind’ – or, to use the term she prefers, androgynous – aesthetic. It is no compliment to be called a ‘female songwriter’ as it ‘implies limitations [which have] always been true of women in the arts’, who are seen as ‘incapable of really tackling the important issues that men could tackle’.22 Her programme is not to deny her position but ‘in order to create ... a rich character full of human experience [for her songs] ... you have to work with the fodder that you have’.23 Indeed, songwriting liberated her:

I never really liked lines, class lines, you know, like social structure lines since childhood, and there were a lot of them that they tried to teach me as a child. ‘Don’t go there.’ ‘Why not?’ ‘Well, because they’re not like us.’ They try to teach you those lines ... And I ignored them always and proceeded without thinking that I was a male or a female or anything, just that I knew these people that wrote songs and I was one of them.24

In 1975’s The Hissing of Summer Lawns (Elektra-Asylum, 1975), Mitchell’s supine swimming body appears alongside the albums lyrics and liner notes (see Figure 18.3). By contrast, the liner notes were cryptic: ‘This record is a total work conceived graphically, musically, lyrically and accidentally as a whole. The performances were guided by the given compositional structures and the audibly inspired beauty of every player. The whole unfolded like a mystery. It is not my intention to unravel that mystery for anyone, but rather to offer some additional clues’. Her ambiguity ultimately fails to displace the fundamental ideological role patriarchy plays in ascertaining musical value because it leaves male privilege untouched and, arguably, placing this text above her bikinied body plays into gendered differential power relations. Male privilege is simply obscured but not eliminated in ‘gender-blind’ aesthetic discourse or when masculinity is described as merely another ‘choice’ among gender positionings. Simply judging artistic works against a standard that is embedded within and implicated by patriarchal Western standards immediately compromises those artists who fall outside of those norms – as Mitchell does, despite her intention to produce androgynous art.25

Figure 18.3 The Hissing of Summer Lawns (Elektra-Asylum, 1975).

Art Nouveau

In (re)naming her ‘inner black’ character Art Nouveau, Mitchell referenced an early twentieth century art movement that strove to beautify ordinary, everyday objects. The original Art Nouveau movement sought to aestheticise, in the sense of ‘making beautiful’, the everyday objects of ordinary life as a way to beautify an increasingly industrialised world.26 Driven by a similar impulse, Mitchell meant to transform subalternity through an engagement with art. Thus, Mitchell can be seen ‘making beautiful’ the street hustler, the con, the pimp. Certainly, we can also view it as racist condescension – who is she, to ‘make beautiful’ those whose racialised bodies encounter material conditions she has never had to even consider, let alone face? As Mitchell claims in the first epigraph to this chapter, she thought she ‘was black for about three years ... like there was a black poet trapped inside me’.27 Similar to Norman Mailer’s white Negroes,28 and as Grier has also noted, Mitchell capitalises on her white privilege in accessing black masculinity in order to transcend, in her case, femaleness, generic limitations, and conventional popular music categorisations.

In this context, one of Mitchell’s paintings blatantly signalled her use of black sexuality and, in particular, the black phallus, that play into tropes of black male hypersexuality, pointedly in its symbolic power over white masculinity, which is feminised in its presence, the fount of the white fear of, and desire for, blackness.29 Mitchell met percussionist Don Alias when he was hired for the Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter (Elektra-Asylum 1977) sessions, beginning a nearly four-year relationship. Mitchell had painted a number of her partners and she painted one of Alias in his bathrobe. Alias describes it: ‘It was me, with my bathrobe open with – bang! like this – a hard-on sticking out’.30 While she eventually succumbed to his pleas about the painting, countering that it was a ‘testament to his sexuality’, transforming the penis into a flaccid appendage, she displayed it ‘smack-dab in the middle of the living room of the loft’ they shared in New York. Perhaps Mitchell was so insistent about this painting because it served as a self-portrait of sorts, recording her self-transformation from blonde waif to black stud, from hippie chick to bebop poet.

Mitchell’s black phallic fixation speaks to all the criticisms her recklessness with racialised, sexualised, and gendered performances might deserve but her eagerness to display the picture ‘smack-dab in the middle of the living room’ reveals a typically confrontational stance. Her imperviousness to any criticism of her appropriation of subordinate identities and cultures was brought into literal sharp relief by her artwork for the cover of Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter (see Figure 18.4). Against a bare red and blue backdrop suggesting a desolate red landscape and an equally barren blue sky, Mitchell mounted a number of blue-toned black-and-white photographs, cut-and-pasted from a number of different photography sessions. Art Nouveau, leaning back, sunglasses obscuring his eyes, is physically mimicking what one imagines was the bodily stance of Mitchell’s Halloween admirer, slyly speaking the title, ‘Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter’, to us, unambiguously naming her audacity and hinting at his possible role in her adventures. As Gayle Wald asks in an insightful discussion of another ‘white Negro’, jazz musician Milton ‘Mezz’ Mezzrow, ‘To what degree do individuals exercise volition over racial identity, or how is volition over the terms of identity itself a function of, and a basis for, racial identity and identity-formation … and to what degree is such imagined racial or cultural mobility itself predicated upon a correspondingly rigid and immobile conception of “blackness”?’31

Figure 18.4 Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter (Elektra-Asylum, 1977).

Grier answers Wald’s question, noting critically, ‘Mitchell has shown that her transcendence of racial boundaries, at least, depends upon others’ upholding their essential functions ... Wisdom is of the North and the white race; heart comes from the soulful blacks of the south. Clarity is the gift of the East’s intelligent yellow race and introspection from the spiritual red men of the West’,32 locating Mitchell’s racial crossing as another instance of white privilege. Yet while dependent on non-white essentialisms, Mitchell has often complicated this relationship. At an infamous 1970 Isle of Wight Festival performance, she was interrupted by an acquaintance of hers named Yogi Joe, who was subsequently taken off the stage by stage hands – an action which prompted boos and yells of disapproval from the audience. In her emotional response to the crowd, Mitchell explicitly disconnected ethnic or racial background from cultural authenticity in her appeal that the audience calm down and let her perform: ‘Last Sunday I went to a Hopi ceremonial dance in the desert and there were a lot of people there and there were tourists ... and there were tourists who were getting into it like Indians and there were Indians getting into it like tourists, and I think that you’re acting like tourists, man. Give us some respect’.33 Her delineation between ‘tourists’ and ‘Indians’ as ‘inauthentic’ and ‘authentic’ experiences drain those categories of conventional, even normative, essentialisms and transposes them in a similar way that her blackface persona, Art Nouveau, highlights the constructed-ness of blackness and masculinity.

But it also reveals the fragility of artifice in the service of art. The self-awareness of the artifice involved in Mitchell’s appeal to her audiences is never adequate to the task of ‘saving’ her. Mitchell, describing her aesthetic at the time of Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter, positioned herself outside of musical norms:

Even though popularly I’m accused more and more of having less and less melody, in fact the opposite is true – there’s more melody and so they can’t comprehend it anymore. So I’m an oddball, I’m not part of any group anymore but I’m attached in certain ways to all of them, all of the ones that I’ve come through. I’m not a jazz musician and I’m not a classical musician, but I touch them all!34

Mitchell’s sense of ‘non-belonging’ from conventional musical categories can be seen in Ariel Swartley’s review of Mingus for Rolling Stone magazine: ‘It’s been a long time since her songs had much to do with whatever’s current in popular music. (She would prefer we call them art-songs.) But then, she doesn’t so much come on as an outsider, but as a habitual non-expert. She’s the babe in bopperland, the novice at the slot machines, the tourist, the hitcher’.35

Mitchell, however, argues that rather than ‘habitual non-expert’, she is a ‘consistent non-belonger’, declaring:

If you want to put me in a group – I tell you, nobody ever puts me in the right group ... I’m not a folk musician ... You know, melodically, folk musicians were playing three-chord changes. [I had] the desire to write [lyrics] with more content with a desire for more complex melody – [that] was my creative objective. That is not folk music.36

Conclusion

In an interview at the time of the release of the Mingus recording, Mitchell cited Mingus’ ‘If Charlie Parker Was a Gunslinger, There’d Be a Whole Lot of Dead Copycats’ as an example of her position on this issue:

Sometimes I find myself sharing this point of view. He figured you don’t settle for anything else but uniqueness. The name of the game to him – and to me – is to become a full individual. I remember a time when I was very flattered if somebody told me that I was as good as Peter, Paul and Mary. Or that I sounded like Judy Collins. Then one day I discovered I didn’t want to be a second-rate anything.37

As a quick perusal through interviews and reviews reveals, she has also been called self-indulgent, opinionated, over-reaching, and pretentious – often by individuals who find her music appealing (at least some of it, most of the time). As Janet Maslin tersely summed up in her review of Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter, ‘These days, Mitchell appears bent on repudiating her own flair for popular songwriting, and on staking her claim to the kind of artistry that, when it’s real, doesn’t need to announce itself so stridently’.38

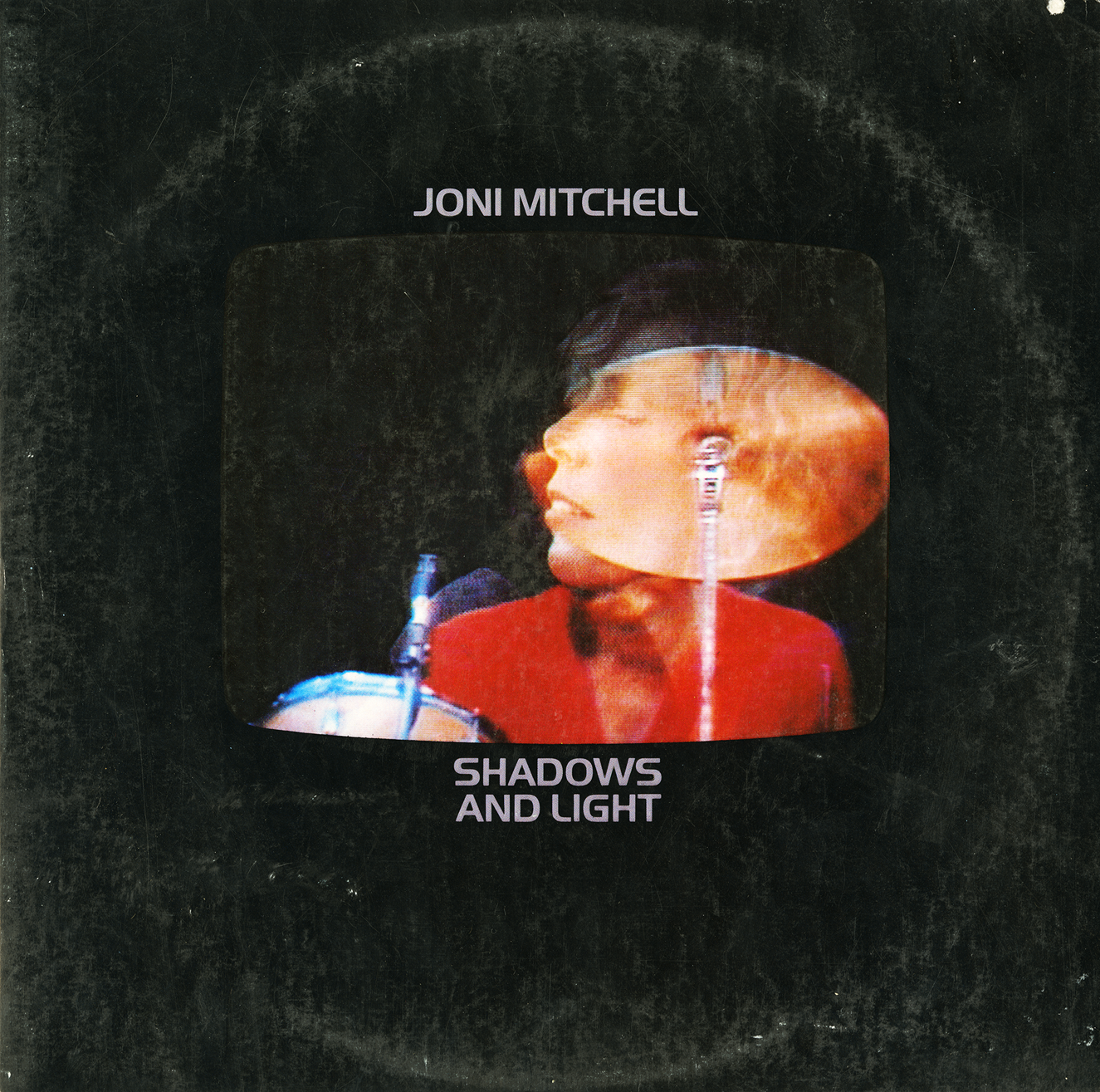

The cover of the live concert recording, Shadows and Light (Elektra-Asylum 1980), provides us with a final arresting visual image (see Figure 18.5). Centred on a black background, a double-exposed photographic image places Mitchell and Alias together within the small frame. Mitchell’s face is slightly obscured as it merges with Alias’ cymbals, his face hidden behind hers. His body is somewhat visible and the result is a jarring image of Mitchell’s profile sitting atop a black male body. Is this yet another case of Mitchell’s racial and gender masking or passing, another fanciful self-portrait? Undermining Maslin’s accusatory dismissal, the image is both revealing and cryptic, unfolding ‘like a mystery [though Mitchell has no] intention to unravel that mystery for anyone’, a figure of shadows and light.39

Figure 18.5 Shadows and Light (Elektra-Asylum, 1980).

It was the mid-1990s and Sarah McLachlan had been on the road promoting her Fumbling Towards Ecstasy (1993) album. At the time, a growing number of female singer-songwriters, such as Tracy Chapman, Jewel, Tori Amos, and Liz Phair, were experiencing significant commercial success. This gave McLachlan an idea. She suggested to her promoters that singer-songwriter Paula Cole be added to the bill as an opening act. Promoters balked and McLachlan quickly realised she had overlooked one crucial yet astoundingly superficial factor: Paula Cole is a woman. For decades, major record labels in the North American popular music industry have operated under the assumption that multiple women on a single concert bill would simply not be a profitable venture.1 It is assumed audiences would not want to hear more than one female voice in an evening. Rather than accept this logic, McLachlan railed against convention and founded Lilith Fair.

Lilith Fair was an all-female music festival that toured North America during July and August of 1997, 1998, 1999, and 2010.2 McLachlan was accompanied by a rotating line-up of approximately eleven to twelve female or female-led acts as the festival travelled to various cities, playing between thirty-five and fifty-five shows, depending on the year. The festival played one or two dates in each city it travelled to, the performances beginning in the afternoon and lasting through the evening. Lilith Fair quickly defied the music industry’s logic by outselling all other North American touring music festivals of 1997. The commercial success of the inaugural Lilith Fair allowed the festival to expand its roster from just over fifty female performers in 1997 to well over one hundred in subsequent years.

As Lilith Fair began touring in 1997, it was apparent that the festival’s ‘celebration of women in music’, as it was billed, was a celebration of a particular type of woman: white, female, singer-songwriters. In 1997, the lineup consisted of fifty-two acts. Thirty-nine of these acts were singer-songwriters, and thirty-six of these women were white. African American singer-songwriter Tracy Chapman would be the only non-white performer included on the Main Stage of Lilith Fair that year.3 Various news outlets and music publications picked up on this point, Neva Chonin accusing Lilith Fair of having a ‘whitebread, folkie focus’.4 Academics were also swift to critique the festival’s definition of women. Gayle Wald has argued Lilith Fair was a universalising recuperation of white women’s music/performance as women’s music/performance.5 Lilith Fair positioned white female singer-songwriters as representative of all women in popular music, much like the women’s liberation movement of the 1960s and 1970s situated the experiences of white middle-class women as normative. For other critics, the festival missed an opportunity to challenge traditional gender roles as they relate to music-making by privileging singer-songwriters over rock musicians, an issue that will be interrogated later in this chapter.6

These criticisms have merit. Lilith Fair’s ‘celebration of women in music’ was based on a limited definition of female musicians. What is missing from these discussions of Lilith Fair is a detailed consideration of the festival that moves beyond teasing out its shortcomings. Although not the first all-female music festival,7 Lilith Fair was the first all-female music festival to tour North America, and in 1997 it did outsell the rock-dominated tours that largely excluded female musicians. Robin D.G. Kelly suggests that if the success of radical movements is judged by whether or not they meet all of their goals; ‘virtually every radical movement failed because the basic power relations they sought to change remain pretty much intact’.8 It would be an overstatement to describe Lilith Fair as a radical movement, but Kelley’s point resonates nonetheless. Lilith Fair did not set out to revolutionise the music industry and challenge how women are represented in popular music. Lilith Fair was a mainstream event with a commercial agenda and because it did not reject the corporate structure which contained it, the festival straightforwardly engaged the politics of representation in the popular music industry that intersect with gender, race, class, and sexuality. While these politics must be foregrounded, Lilith Fair was more than just its failures.

The focus of this chapter is the Lilith Fairs of 1997, 1998, and 1999. Poor ticket sales plagued the 2010 festival and many of the dates were cancelled. Pinpointing a reason the festival could not be revived with more financial success is difficult. Perhaps it was a reflection of changing times, including an economic recession that stalled sales for North American concert tours in 2009 and 2010.9 The festival was also founded during a decade when a range of feminist perspectives circulated in the music industry, including the Riot Grrrl movement and The Spice Girls’ brand of ‘girl power’. Lilith Fair emerged during a cultural moment that celebrated feminist consciousness and women working in popular music, a climate that was not mirrored in 2010. The result was the cancellation of thirteen of the thirty-six scheduled dates. Many artists were forced to withdraw, and therefore the 2010 revival poses too many questions and problems to be considered here.

This chapter will expound upon the problems of representation the Lilith Fairs of 1997, 1998, and 1999 reproduced in order to scrutinise the festival’s definition of women; it must be made pervious so as not to cement hegemonic understandings of ‘women’. It is only in this context that the scope of the conversation can be broadened to address the following questions. How do criticisms that Lilith Fair privileged singer-songwriters over rock musicians ignore how gender and race intersect with genre in popular music? White female singer-songwriters dominated Lilith Fair, but what does this mean musically? As the first opportunity female musicians had to tour together in a festival setting, how did Lilith Fair engage with ‘women’s music’ and community? Women (specifically white women) have historically been well represented as singer-songwriters, but are often talked about in ways that enlist the notion of ‘women’s music’ and render musical differences irrelevant. Given the visibility of singer-songwriters within Lilith Fair, it may be useful to rethink the festival’s musical and extra-musical activities in a way that politicises a tradition often sutured to introspection and confession, deemed appropriate for women, and ghettoised as ‘women’s music’.

Scrutinising Lilith Fair

Festival organisers were quick to respond to criticisms that highlighted the issue of diversity in the 1997 Lilith Fair lineup. Organisers of the festival released this statement on the Lilith Fair 1998 website: ‘In addition to the Main Stage, Lilith Fair will again incorporate Second and Village Stages for both established and emerging artists, with an emphasis being placed on offering an even broader range of musicianship to this year’s audience.’10 While the 1997 Main Stage included only singer-songwriters, a survey of the women who performed on the Main Stage in 1998 shows that while white female singer-songwriters were still present, so too were rappers Missy Elliott and Queen Latifah, rock band Luscious Jackson, and soul singers Me’shell Ndegeocello, and Erykah Badu.

Table 19.1 Lilith Fair Main Stage 1998 performers.

| Me’Shell Ndegeocello |

| Erykah Badu |

| Missy Elliott |

| Queen Latifah |

| Des’Ree |

| Luscious Jackson |

| N’Dea Davenport |

| Diana Krall |

| Cowboy Junkies |

| Mary Chapin Carpenter |

| Emmylou Harris |

| Indigo Girls |

| Sarah McLachlan |

| Meredith Brooks |

| Natalie Merchant |

| Shawn Colvin |

| Liz Phair |

| Bonnie Raitt |

| Tracy Bonham |

| Suzanne Vega |

| Paula Cole |

| Chantal Kreviazuk |

| Joan Osborne |

| Lisa Loeb |

Notably, eighteen of the twenty-four Main Stage performers in 1998 were white and six were African American.11 This dualism also functioned in Lilith Fair 1999, as twelve of the seventeen Main Stage acts were white, five African American.12 Although Lilith Fair diversified the music heard on its Main Stage, overall white female singer-songwriters still comprised approximately two-thirds of the lineup, and rock bands were scarce.

Lilith Fair’s predominance of singer-songwriters and relative invisibility of rock musicians is not a situation unique to the festival, but a disparity that exists in popular music generally. The reasons behind this have as much to do with rock’s hegemonic masculinity as they do with the relationship between singer-songwriters and gender. Since the 1950s, rock has been a male-dominated space that typically only makes room for women as the lyrical objects of desire or resentment, or as devoted fans and groupies.13 The reasons for this are numerous, and include such issues as performance aesthetics, rock criticism, the electric guitar as phallic symbol, the masculinisation of technology, and gendered barriers to knowledge acquisition and gear. As a result, women tend to be far less visible in rock music than their male counterparts.14

In contrast, women have prospered and been heard as singer-songwriters. Gillian Mitchell contends the singer-songwriter tradition was the most visible outcome of the folk revival from the 1960s onwards.15 By the end of the 1960s, many folk revival performers began drifting towards the mainstream, in large part due to a shift in the cultural climate. The eclecticism and optimism that characterised the revival movement chafed against the conflict, protest, and rallies of the 1960s. As revival-style folk music began mingling with the sounds of mainstream popular music, lyrics gravitated towards introspection and personal experience, and women such as Joan Baez, Joni Mitchell, and Judy Collins, who were prominent in the folk scene, continued to be at the forefront.

Women’s visibility as singer-songwriters has much to do with the introspection and confession that characterised the music of singer-songwriters during the 1970s. The image of a lone, self-accompanied female musician with an acoustic instrument, stoically delivering confessional lyrics does not challenge traditional representations of femininity informed by white, middle-class respectability. Because of these associations, women are better-represented as singer-songwriters than rock musicians – at least some women are better-represented.16 The visibility of Joni Mitchell, Joan Baez, and Judy Collins during the 1960s and 1970s leads Gillian Mitchell to suggest the folk revival’s ideals of inclusiveness were actively materialised. A closer look at the women Mitchell cites, however, reveals a different picture. Thirteen of the fifteen women she cites as active in the Greenwich Village and Yorkville folk/singer-songwriter scenes in the 1950s and 1960s are white.17 Lilith Fair clearly demonstrates white women have continued to thrive as singer-songwriters, while women of other ethnicities are less visible as singer-songwriters in the mainstream, commercial market. Ellie Hisama and bell hooks suggest this is in large part due to the pressure many black female singers experience to cultivate an image of sexual availability, a direct consequence of ideologies that situate black sexuality as more free and liberated than white sexuality. As a result, black women do not always figure into either the racially marked women’s music scene or singer-songwriter category, where whiteness and respectability run deep.18

Lilith Fair did not create a space in which an equitable representation of female musicians in popular music was materialised, but in this respect the festival is not unique. While the women’s music scene was largely comprised of white, lesbian women, the first Ladyfest focused on indie rock, privileging white female musicians.19 As subsequent Ladyfests were organised internationally, each struggled to create inclusive lineups that acknowledged, ‘the contributions of women of colour as fellow organisers, musicians, and volunteers without rendering them as either token participants or invisible’.20 Arguably, this is where Lilith Fair struggled most. Because the Main Stage remained predominantly white, the majority of women who were not Caucasian were included on the Second and Village Stages.

Lilith Fair concerts were primarily held in amphitheatres, where a single stage was already in place and utilised as the festival’s Main Stage. Seating consisted of rows of seats in front of the Main Stage, grass seating behind them. The secondary stages were necessary because the eleven to twelve acts included on each concert bill performed consecutively. While one musician performed on the Village Stage, another could set up on the Second Stage, minimising the time spent setting up and removing equipment. Typically, the only delay between performances occurred during the evening when the Main Stage acts performed. Although a necessity in terms of production, the way in which these stages were positioned established hierarchies. The Second Stage was commonly situated amongst the grass seating, leaving those in the permanent seating with their backs to the Second Stage performers. The Village Stage was often located in the Village, an area not usually visible from the permanent or grass seating, and which included the distractions of booths and vendors. One might argue the musicians included on the secondary stages were lesser known and did not have a large enough audience to warrant billing on the Main Stage. Such thinking only reiterates the hegemony at play in Lilith Fair, and overlooks the choices made that favoured commercially successful white women.

Lilith Fair, genre, and ‘women’s music’

Lilith Fair’s definition of women musicians was narrow and physically inscribed on the festival’s landscape. Highlighting these issues is imperative in order not to perpetuate the recuperation of white female musicians as all ‘women in music’. To abandon the conversation at this juncture obscures the practices that prompted the founding of Lilith Fair, and implies female singer-songwriters have circumvented resistance in the popular music industry. Male singer-songwriters of the 1970s were intellectually appreciated for their views on politics and cultural events, and artistically revered for sensitive and autobiographical lyrics that ruminated on sex, love, and relationships.21 Descriptions of singer-songwriters as confessional and introspective proved thorny for female singer-songwriters. When applied to women, these adjectives become sutured to cultural representations of women as emotional and irrational. Joni Mitchell, Carole King, and Carly Simon produced a wealth of music during the 1970s that reflected a changing social climate. As they contemplated sex, relationships, politics, family, and work, female singer-songwriters questioned traditional ideals and considered new perspectives, particularly as they related to white, middle-class women benefiting from the women’s liberation movement.22

Socially and politically conscious lyrics did not necessarily ensure a serious reception. Stuart Henderson has examined the critical discourse surrounding Joni Mitchell’s musical output and found over the course of her first three albums, Mitchell was described using language that evoked youthfulness and naïveté. As her work became increasingly biographical and reflected the complexities of relationships and sex, the discourse was condescending and patronising. In 1970, Rolling Stone labelled her the ‘Queen of el-Lay’ and later published a list of her alleged lovers. Her record label Reprise published advertisements such as ‘Joni Mitchell is 90% Virgin’ and ‘Joni Mitchell Takes Forever’.23 (See also Chapter 18 in this volume) Mitchell’s personal disclosures and reflections were co-opted and used to depoliticise a body of work that clearly reflected the influence of both the sexual revolution and women’s liberation movement.24 Despite this, many female listeners saw themselves in the songs of Mitchell, Simon, and King and became a large market willing to purchase music that spoke to their experiences. By the early 1970s, the percentage of top-selling albums recorded by female artists reached double digits, and in 1974, Time magazine concluded ‘women’s music sells’.25

Twenty years later and these issues persisted. Singer-songwriter Fiona Apple gave voice to her personal story of rape in ‘Sullen Girl’, but a 1997 performance of the song was described as a ‘precocious teen-age girl becoming sure of herself’ by the New York Times.26 Various incarnations of ‘women’s music’ and ‘women in music’ also appeared as headlines during the 1990s, touting the success of such singer-songwriters as Jewel, Alanis Morissette, Tracy Chapman, Sarah McLachlan, Fiona Apple, and Liz Phair.27 In the wake of their commercial success, Warner Elektra Atlantic released five volumes of the compilation album Women & Songs between 1997 and 2000.

These headlines and compilation albums perpetuate the notion that music performed by female singer-songwriters is ‘women’s music’; that music made by female singer-songwriters constitutes a genre simply by virtue of their sex. ‘Women’s music’ is not imbued with musicological meaning, and in fact subsumes musical differences. Female singer-songwriters have been labelled ‘women’s music’ because they are women who write and perform their own music, not because of shared musical characteristics. The assumption that these women constitute a genre on the basis of their sex is what informed the music industry’s practice of not billing multiple women on a single concert tour; such a bill would be too similar. ‘Women’s music’ is also frequently conflated with the women’s music scene of the 1970s, a lesbian feminist project with the goal of transforming the mainstream music industry through women’s music recording and distribution companies, and enacting lesbian feminist politics through women-only events such as the Michigan Womyn’s Festival.28 A distinction between the marginalising label ‘women’s music’ and the women’s music scene is often lost, and therefore ‘women’s music’ invokes intimations of queerness whether they are real or imagined.

Lilith Fair provides an opportunity to further a critical dialogue around the relationship between female singer-songwriters and ‘women’s music’. Norma Coates’ discussion of ‘women in rock’ provides a useful starting point as she argues ‘women in rock’ separates rock and women; women are only related to rock by being allowed in. The label ‘women in music’ functions similarly by positioning women only in relation to music, not as a natural part. Coates proposes that rather than rejecting these gendered labels, ‘women in rock’ may be a politically useful term because it designates rock as contested ground: ‘By latching on to the label, women involved with rock can problematise the very practices and conditions which necessitate the use of that term within popular rock discourse’.29 Whether prohibited from touring with other women or excluded from rock festivals such as Lollapalooza, the need for Lilith Fair was clear. Lilith Fair’s ‘celebration of women in music’ designated music as contested ground and problematised the conditions that prompted the festival by deploying a roster comprised primarily of singer-songwriters to interrupt sexist music industry practices. The favouring of white female singer-songwriters highlighted inequities between female musicians and clearly situated the singer-songwriter tradition as a racially marked category that remains contested ground for those women who are not Caucasian.

The commercial success of Lilith Fair did not simply defy faulty industry logic, but also placed so-called ‘women’s music’ in a highly visible position. From this position, the festival confronted the tendency to depoliticise female singer-songwriters by creating a socially and politically engaged environment. Forming corporate sponsorships with Bioré, Nine West, and Borders Books and Music, Lilith Fair and its sponsors made donations both to local charities and to organisations identified as official Lilith Fair charities, such as RAINN (Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network), Planned Parenthood, and Artists Against Racism.30 These organisations addressed social, political, and economic issues with particular relevance to women, and were represented in the Lilith Fair Village in the form of booths providing information and education for audience members. Many of the topics and issues that were visible in the Lilith Fair Village were also voiced during festival performances. Alongside introspective performances contemplating love, such as in Jewel’s ‘Foolish Games’, Tracy Chapman spoke to cyclical poverty and unemployment in ‘Fast Car’, while Suzanne Vega commented on domestic violence in ‘Luka’.

Foregrounding a range of sounds and musicians would also problematise the tendency to group female singer-songwriters as ‘women’s music’, and those industry practices that rested on the same notion.31 In 1997, for instance, Emmylou Harris’ folk, country, rock, and bluegrass-inspired material was featured alongside Yungchen Lhamo’s unaccompanied vocals that drew on traditional and world music influences. Meredith Brooks’ guitar-based, rock-influenced performances also stood in stark contrast to Sarah McLachlan’s adult contemporary, piano-accompanied soprano. Singer-songwriters dominated the landscape of Lilith Fair, but the music they performed was varied and diverse and reflected the myriad of musical influences shaping the output of singer-songwriters. As Lilith Fair toured in subsequent years, female singer-songwriters performed alongside the pop vocals of Christina Aguilera, Cibo Matto’s indie rock and trip hop sounds, the soul, R&B, funk, and hip-hop-inspired repertoire of Me’shell Ndegeocello, the country sounds of the Dixie Chicks, and the rock, trip hop, down-tempo material of Morcheeba, broadening the festival’s definition of ‘women in music’.

At the end of each evening, the performers gathered onstage for an all-artist finale reminiscent of the folk revival’s emphasis on community and participation. The socially and politically conscious lyrics of Joni Mitchell’s ‘Big Yellow Taxi’ and Marvin Gaye’s ‘What’s Going On’ were the preferred choices and provided an audible example of community. Lilith Fair artists assembled informally and shared lead and backing vocal duties. The all-artist finales signalled a collective while defying the traditionally solitary nature of the singer-songwriter and the notion that female musicians should not share concert billing. Both factors have hindered a sense of community and belonging for female musicians in the popular music industry, something Sarah McLachlan hoped Lilith Fair could counter: ‘Lilith Fair was created for many reasons … the desire to create a sense of community that I felt was lacking in our industry’.32

Community did not refer to a fixed location or group of performers, but was imagined in the sense proposed by Benedict Anderson. As geographical exploration and the evolution of the printing press destabilised religious universalism and exposed the pluralistic nature of the world, people found new ways to define their place in the world, imagining this new place and their relationship to other people. The community Lilith Fair cultivated extended to only a small segment of female musicians working in popular music, but as Hayes argues, the women’s music scene did not change the music industry in the ways the scene had hoped, but it did play a valuable role in ‘buoying women’s spirits in the process of community formation’.33 Lilith Fair addressed only a handful of issues that some women in popular music face, but it did foster a sense of community that was lacking. Lilith Fair participants shared billing, attended press conferences together, and gathered in spontaneous musical moments backstage. As the festival stopped in various cities across the continent, local female musicians were invited to compete in the Village Stage Talent Search for the opportunity to perform on the Village Stage. Lilith Fair created a space that had not previously existed, even if that space had its limitations.

Conclusion

Lilith Fair’s version of ‘women in music’ was clearly flawed, foregrounding gender and clouding the way in which race, class, and sexuality informs the participation of female musicians in popular music. Lilith Fair signified a cultural moment when some women in popular music were able to openly problematise gendered practices that had existed in the popular music industry for decades. Expanding the conversation beyond Lilith Fair’s shortcomings to include a survey of the women and musics that Lilith Fair featured makes it clear it is necessary to interrogate both who was included and what music was heard. To dismiss the festival for its privileging of white singer-songwriters both obscures the racialised history of the singer-songwriter tradition, and overlooks the problematic ways ‘women’s music’ informs the reception of female singer-songwriters. Female singer-songwriters do not constitute a genre of music. Lilith Fair confronted the tendency to depoliticise and ghettoise female singer-songwriters as ‘women’s music’ by highlighting the range of musical traditions informing the output of singer-songwriters in an environment that emphasised social and political awareness. Lilith Fair’s landscape was far from the paradise Joni Mitchell laments in ‘Big Yellow Taxi’, but it should be considered anew as a space from which to explore the intersection of female singer-songwriters, genre, and ‘women’s music’.

A characteristic feature of the singer-songwriter idiom is the perceived confessional and personal nature of communication from musician to listener. The most commercially successful singer-songwriters use lyrics to describe personal experiences in ways heard by the listener as shared, universal experiences (falling in love, breaking up with a partner, and so on).1 Allan Moore concurs, describing this validation of listener’s life experiences as ‘second-person authenticity’.2 In most cases in the Anglophone pop mainstream, these assumed shared life experiences between creator and receiver reinforce the expected norm of the heterosexual, usually white, Western adult.3

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) perspectives complicate this universality.4 In this chapter, I consider how three LGBTQ singer-songwriters have used musical styles, lyrics, and extramusical actions and activities to effect and respond to changing social attitudes and tolerance over the last fifty years.5

Elton John

Reginald Kenneth Dwight was born in Pinner, Middlesex (UK) on 25 March 1947. He began playing the piano aged three, and was awarded a Junior Scholarship to the Royal Academy of Music aged eleven. In 1962, he began performing in a local pub, playing the piano to accompany himself singing cover versions of contemporary hits as well as his own songs. Two years later he joined his first band, The Corvettes, which later reformed as Bluesology. Dwight took his stage name from the Bluesology saxophonist Elton Dean and their lead singer Long John Baldry, and legally changed his name to Elton Hercules John in 1967.

In 1967, Elton John answered a ‘Talent Wanted’ advert in the New Musical Express. Ray Williams of the NME put him in touch with lyricist Bernie Taupin, and thus began the longstanding songwriting collaboration that persists to this day. (For more biographical detail, and issues of authorship and performance, see Chapter 11.)

The collaboration began remotely, with Taupin sending John completed lyrics to set to music. This can be seen as a modern-day counterpart to the ‘Lied singer-songwriters’ of the nineteenth-century (see Hamilton and Loges in Chapter 2) – although a distinction may be drawn between the latters’ tradition of setting established poetry to music, and John setting lyrics that Taupin had written for the purpose. Despite changing environments – the pair shared bunk beds at John’s mother’s Pinner home in the 1970s and later flat-shared – they have continued working in series to this day (2015).6 Due to their longstanding working relationship, the popular persona known as ‘Elton John’ embodies Taupin’s lyrics and John’s musical and performing input. Elton John has continued to record prolifically, and at the time of writing has recorded and released over thirty studio albums and four live albums.

In Britain, centuries of intolerance meant that that, by the 1950s, the official mood towards homosexuality was hostile. In 1952, the commissioner of Scotland Yard Sir John Nott-Bower, began to eliminate suspected homosexuals from the British Government.7 (At the same time in the United States, Senator Joseph McCarthy carried out a federally endorsed witch-hunt against Communists and, on a lesser scale, homosexuals.) In the late 1960s, Elton John became engaged to secretary Linda Woodrow (who is mentioned in the song ‘Someone Saved My Life Tonight’), publicly showing his involvement in a relationship that was socially acceptable.8

‘Your Song’ (1970)

One of John and Taupin’s best-known collaborations was ‘Your Song’, released on John’s self-titled second album (1970). ‘Your Song’ was released in the United States in October 1970, as the B-side to ‘Take Me to the Pilot’, eventually replacing the latter as the A-side due to its popularity; it reached Number 8 in the US charts, and Number 7 in the UK.

‘Your Song’ has a contrasting verse-chorus structure, where each chorus is preceded by two iterations of a four-line verse with changing text.9 The song has an acoustic soundworld that builds throughout. The lyrics of the chorus are self-referential, as John sings about writing the song for his loved one.

The lyrics are gender neutral; the addressee is always referred to in the second person (‘you’, ‘your’). The ambiguity allowed by these terms enables listeners to create their own interpretation: heterosexual listeners will interpret this as a straight relationship, while LGBTQ listeners will hear representations of their own sexual preference. John’s use of unmarked gender terminology leaves room for listener interpretations.10 However, given the societal and officially encouraged norm of heterosexuality in 1970s Britain, ‘Your Song’ can be assumed to be documenting such a relationship – ambiguously creating Moore’s second-person authenticity by validating the emotions and experience of mainstream culture as understood by the listener. The ongoing resonances of these emotions are reinforced by the song’s popularity, and the numerous cover versions by singers of both sexes over the decades.11

Despite the fact that at this point John’s biography was carefully managed to keep his sexuality ambiguous, the low and expressive vocal quality and unobtrusive recording techniques used in ‘Your Song’ begin to subvert traditional notions of masculinity. In subsequent decades, traditional notions of masculinity as labour were reversed by vocal and recording qualities that suggest directness and intimacy, as Ian Biddle notes.12

Homosexual acts between men (two consenting adults, in private) were decriminalised in England and Wales in 1967. In 1976, Elton John publicly came out as bisexual in an article in the music magazine Rolling Stone, claiming that he had not felt the need to acknowledge it openly before.13

In the same interview, Elton John explained that his first sexual relationships were with women. He was married to record producer Renate Blauel from 1984–8 – a relationship that could be seen publicly as conforming to the socially accepted heterosexual norm, but privately reinforced his bisexuality. However, by 1992 John informed Rolling Stone that he was ‘comfortable being gay’, explaining that he had settled with a male partner and felt happy and optimistic about the future.14

In October 1993, John entered a relationship with Canadian/British film producer David Furnish. The couple was one of the first in the UK to form a civil partnership when the Civil Partnership Act came into force on 21 December 2005. They have since adopted two children, Zachary Jackson Furnish-John (b. 25 December 2010) and Elijah Joseph Daniel Furnish-John (b. 11 January 2013). Furnish has since stated their intention to marry, since same-sex marriage was legalised in the UK on 29 March 2014:

Elton and I will marry … When it was announced that gay couples were able to obtain a civil partnership, Elton and I did so on the day it came into law. As something of a showman, [Elton] is aware that whatever he says and does, people will sit up and take notice. So what better way to celebrate that historic moment in time. Our big day made the news, it was all over the Internet within minutes of happening and front page news the next day.15

A significant change can be seen in societal attitudes towards homosexuality in the forty-eight years since John’s public career began. In the 1970s, he was reticent about his private life, but by 2015, he and Furnish felt able to use their fame to bring general attention to some of the social and civil restrictions faced by same-sex partners.

k. d. lang

Kathryn Dawn Lang was born in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada on 2 November 1961. She started singing at the age of five, and became fascinated with the life and music of country singer Patsy Cline while attending the Red Deer Community College. At the same time, Lang expressed her creativity in a series of performance art shows. She also formed a tribute band (the reclines), and adopted the stage name k. d. lang.

Their debut album, A Truly Western Experience, received positive reviews and national attention on its release in 1984. k. d. lang and the reclines released two further albums in the country style, Absolute Torch and Twang (1987) and Angel with a Lariat (1989). Richard Middleton comments on the rigid conventional gender politics of the country music scene, suggesting that lang’s complex gender identity began with Absolute Torch and Twang:

Here is some form of female masculinity … applied to country (including covers of songs ‘belonging’ to men), yet also performing torch songs (a genre traditionally associated with submissive, suffering femininity) … Her bluesy articulations come from torch song, but are smoothly integrated into a full range of country vocal conventions (growl, falsetto, catch in the throat) so that the overall impression, particularly in light of her powerful, gleaming timbres produced through a wide range of registers, is one of (phallic?) control.16

lang released her first solo album in 1988. As well as overt stylistic traits such as yodelling, steel guitars and the lush strings of the Nashville sound, Shadowland was linked to country and western music through producer Owen Bradley (who had produced Patsy Cline, 1957; Patsy Cline Showcase, 1961; and Sentimentally Yours, 1962). The performing persona that she developed was androgynous and grungy: she favoured short haircuts, and low-maintenance outfits such as jeans, check shirts, and dungarees. Again, lang used the strictures of country music and the associated cowboy scene to develop and nuance her gender identity: as Corey Johnson explains, at that time sartorial decisions based on cowboys were used by the LGBTQ community to satirise aggressive heteronormative masculinity, and to inform drag costumes.17

In 1990, lang recorded Cole Porter’s ‘So in Love’ for Red Hot & Blue, a compilation album to benefit AIDS research and relief.18 Themes of non-heteronormative sexualities pervade her cover version: although he married Linda in 1919, Porter is described variously as bisexual and homosexual.19 In the accompanying music video lang wears androgynous dungarees while doing a woman’s laundry. She buries her face in a negligee, lending weight to the rumours that were circulating of her lesbianism.

Her next solo album, Ingénue, was released in March 1992, and represented a change in musical direction from her previous work. Lang and her musical collaborator Ben Mink drew influences from many styles, including ‘1940s movie musicals, spiritual hymns, Russian folk music, American jazz, Joni Mitchell-like tunings and harmonies, Indian folk music and more’.20

‘Constant Craving’ (1992)

‘Constant Craving’, featured last on Ingénue, is lang’s most famous song. It was the first single released from the album, and charted at number 38 on the Billboard 100 and number 2 on the Adult Contemporary Chart. The following year, k. d. lang won multiple awards with the song, including Grammy Award for Best Female Pop Vocal, and the MTV award for Best Female Video.

The soundworld is established with a gentle rock beat, strummed acoustic guitar and melancholy harmonica, and is later enriched by a vibraphone counter melody. The minimal lyrical content depicts the relentless yearning of the song title. lang sings two verses, alternating with a chorus, with further repetitions of the chorus to finish. Her solo vocal is supported by a backing choir that echos her lyrics.

In contrast to ‘Your Song’, the lyrics of ‘Constant Craving’ do not refer to a loved one. Instead, they document and reflect upon the emotion of yearning. lang’s biographer Victoria Starr states that this ‘tormented splendor’ applies to the whole album, and refers to an unrequited love experience – exhibiting second-person authenticity.21 However, as explained below, in combination with lang’s biography, the lyrics create something more akin to first-person authenticity – where the listener believes that the musician is expressing their own lived experiences, in a direct and unmediated format.22

lang publicly came out as lesbian in a June 1992 issue of LGBTQ magazine The Advocate, and has actively championed gay rights causes since.23 Taken in combination with her personal life, the gender-neutral pronouns of the songs and the lyrical descriptions of love, yearning, and loss, take on a different meaning.

lang’s plea in the fourth song on the same album, ‘Save Me’, can be understood as an appeal to either gender, as she sings to an unnamed addressee: ‘Save me from you … Pave me/The way to you’. However, a closer reading of the album shows playfulness with gender construction and ambiguity. The song’s video depicts lang in an exaggeratedly feminine manner, surrounded by bright colours and bubbles. This stands in contrast to the persona that lang has chosen to adopt: a brief glance at her album covers, media presence, and performances show that she prefers androgynous hairstyles and clothing. The caricatured account of femininity lang creates on the ‘Save Me’ video perhaps satirises the fact that the English-language Canadian magazine Chatelaine once chose her as its ‘Woman of the Year’.

The following year, lang famously appeared in a cover photo and photo spread in the mainstream magazine Vanity Fair. The cover of the August 1993 issue featured a seated lang being shaved by supermodel Cindy Crawford. In contrast to the singer’s stereotypically masculine pinstripe suit and waistcoat, Crawford is dressed in a revealing swimsuit and high heels. As anthropologist Joyce D. Hammond explains, the photo shoot (conceived by lang, photographed by Herb Ritts, and willingly participated in by Crawford), challenges typical gender constructions by subverting both expected power dynamics in heterosexual relationships and those of lesbian and homosexual couples.24 The photo caricatured the stereotypical lesbian combination of butch and femme, by placing lang (dressed as a man, complete with shaving foam and the masculine stance of a crossed leg balanced on the opposite knee) in the submissive role of being tended to by an overly feminised and hypersexualised female supermodel in a dominant standing position, complete with careful makeup and hair. Although she claims that she came out publicly for personal, rather than political reasons, lang’s public profile, her 1992 article in The Advocate, and her photo shoot for Vanity Fair all contributed to a mainstreaming of lesbianism. Neil Miller concludes: ‘Nineteen ninety-three was the year of the lesbian. The print media discovered lesbians … Television discovered lesbians.’25

A subversion of traditional gender roles can also be seen in lang’s 1997 album Drag. The album is a covers album, with songs (such as ‘Don’t Smoke in Bed’, and ‘My Last Cigarette’, ‘The Old Addiction’, and ‘Love is Like a Cigarette’) supporting the album’s ostensible theme of smoking. However, the term ‘drag’ has been used in British slang since the late 1800s to refer to clothing associated with one gender but worn by the other. The term ‘drag queen’ is used to identify (often homosexual) men in women’s clothing, while ‘drag kings’ refers to women in mens’ garb. The album art for Drag features a close-up portrait of a carefully made-up lang in a mens’ formal black suit, with a white shirt and burgundy cravat, thereby reinforcing the gender ambiguity of the album but reversing the expected gender roles of drag queens.

On 11 November 2009, lang entered into a domestic partnership with Jamie Price, who she had met in 2003. They separated in September 2012, and lang filed for a dissolution of the marriage. Since coming out in 1992, lang has used her position as a famous musician to raise public awareness of lesbians.

Rufus Wainwright

Rufus Wainwright was born on 22 July 1973 in Rhinebeck, New York, to parents Kate McGarrigle and Loudon Wainwright III, both of whom were successful and well-known folk singers. They divorced when he was three, and he spent much of his childhood in Kate’s home town of Montreal, Canada.

Societal tolerance of non-heteronormative sexualities was growing: in June 1969 police raids on the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village, New York City had prompted members of the gay community to violent demonstrations, physically showing their dissatisfaction with the status quo; while in the year of Wainwright’s birth, the American Psychological Association removed homosexuality from its diagnostic manual (suggesting it had been considered an illness until that point). This social tolerance was tempered by a fear and lack of knowledge about the growing AIDS epidemic at the time, which public misconception frequently linked to homosexual activity.

Wainwright accepted his own homosexuality early on, stating in a 2009 documentary: ‘I knew when I was very young, when I was about fourteen, that I was gay.’26 As a teen, he spent many of his evenings sneaking out to gay bars, where he was ‘a Lolita-esque character, a fourteen-year-old boy who looked no older than his years, leaning at the bar, craving attention from older men’.27 In the summer of 1988, he engaged in similar behaviour while visiting Loudon in London, and suffered a violent sexual assault while walking in Hyde Park with a man he met at a bar. He subsequently entered a period of reclusivity and sexual abstinence. At around this time, Loudon and Kate sent him to finish his high school education at Millbrook, a private boarding school in upstate New York. Wainwright therefore went through initial experiences of his sexuality without the support of his family and friends, choosing to come out to his parents a few years later.

After beginning and dropping out of a music degree at McGill University in Canada, Wainwright returned to Montreal in 1991 and began building a repertoire of original material, performing frequently on the cabaret and club circuit. Like Elton John, his instrument of choice was the piano – but Wainwright differed in that he wrote the music and lyrics to his songs.28 Wainwright has an enormous vocal range, which he utilised more in performance and recordings as his career progressed. He is able to slide smoothly through a warm tenor, chest alto voice, head voice into falsetto, and a true falsetto, enabling a range of vocalised gendered personas.29 Wainwright has candidly displayed a queerness in his performance and recordings, which is supported by his developing performing person, his lyrical content, and his vocal qualities.30

The second song on Rufus Wainwright, his 1998 debut album, ‘Danny Boy’, describes his infatuation with a straight man named Danny. Apart from the fact that the lyrics are sung by a man, they could refer to a heterosexual relationship. Unlike either John or lang before him, though, Wainwright names his addressee, singing: ‘You broke my heart, Danny Boy/Not your fault, Danny Boy’. Other songs on the album deal with his sexuality more implicitly: ‘Every kind of love, or at least my kind of love/Must be an imaginary love to start with’ (from the closing song ‘Imaginary Love’).

The early 1990s saw a wave of critical and cultural theory that explored queerness as an alternative to binaries apparent in previous society and scholarship. Rufus Wainwright associates his awareness of his homosexuality with discovering opera in his teens, a connection also drawn by influential literary figures such as Wayne Koestenbaum and Sam Abel.31 ‘New musicology’ echoed conventions of literary criticism by introducing interdisciplinary approaches, focusing on the cultural study and criticism of music. In Queering the Pitch: The New Lesbian and Gay Musicology (1994), a collection of ‘mostly gay and lesbian scholars’ aimed to challenge binary tactics and positivistic approaches to previous musicological scholarship, claiming that they found it less interesting to ‘out’ composers and musicians (such as Franz Schubert, explained in more detail below and on accompanying website) than to reveal the homophobia present in previous scholarship and readings.32 By the mid-1990s, cultural awareness of LGBTQ music-making and appreciation went outside the media ‘year of the lesbian’ cited by Miller: it had become an academic discipline.

‘Pretty Things’ (2003)

In ‘Pretty Things’, the fifth song on Wainwright’s 2003 album Want One, he subtly expresses his sexuality. The assumed autobiography of his songs means that Moore’s authenticity is reinforced, but rather than validating listeners’ experiences (second-person authenticity), here the listener is encouraged to believe that Wainwright is sharing his own experiences (first-person authenticity).33 In line with the singer-songwriter idiom, his songs are perceived as more truthful because they appear unmediated. From a compositional/songwriting perspective, the song pays homage to the nineteenth-century Austrian composer Franz Schubert (to whom Wainwright had already paid tribute to with the line ‘Schubert bust my brain’ in the aforementioned ‘Imaginary Love’). Wainwright scored ‘Pretty Things’ for solo piano and voice, and marketed the song as a twenty-first century Lied (piano and vocal song, usually written for pre-existing text in the German vernacular, made famous by Schubert).34

The lines ‘Pretty Things, so what if I like pretty things/Pretty lies, so what if I like pretty lies’ give an insight into the tastes that Wainwright chooses to share. He continues by lamenting his alienation from society and his loved one: ‘From where you are/To where I am now’. It is but a small step to unite the two lyrical features: a man who is attracted to the typically feminine ‘pretty things’ may be ostracised and alienated from society. In his 2010 analysis of ‘Pretty Things’, Kevin C. Schwandt makes a connection between the isolating and ostracising device of Wainwright’s (assumed autobiographical) protagonist’s taste for pretty things (going against the masculine norm), and the standard Western musicological reading of Schubert as Beethoven’s feminine Other. Schwandt suggests that by associating himself and his music with Schubert, Wainwright implicitly aligns himself with these domestic and feminine readings.35 Schwandt implies that Wainwright was aware of the academic controversy that surrounded Maynard Solomon’s ‘outing’ of Schubert in 1989, and the longstanding tradition of homosexual oppression associated with Schubert’s life and music, and deliberately associated himself with it, in order to align himself with historic homosexuals.36 The lyrics are gender neutral, but Wainwright’s male voice and evocation of ‘pretty things’ make his subject position clear.

Wainwright maintained and developed his autobiographical subject matter and flamboyant performing persona, and made his sexuality more explicit in later songs and performances. While touring the Want albums, Wainwright routinely performed the overtly political ‘Gay Messiah’ (Want Two, 2004) dressed in heavenly garb, descending from the sky on a crucifix. The lyrics evoke a Gay Messiah, sent to save homosexuals the world around, and entangle religious stories with themes of salvation and sexual practices.

The song opens with a suggestion that listeners pray for salvation, before announcing that the gay messiah is coming (as in arriving). This final word is transformed at the end of the second stanza, when Wainwright claims to be ‘baptised in cum’ (the lyrics in the Want Two liner booklet use the spelling commonly associated with the male ejaculate). Wainwright continues twisting and conjoining sexual and biblical imagery, referencing the story of John the Baptist by suggesting that ‘someone will demand my head’. Again, he turns it back to a sexual metaphor, with a word play on ‘giving head’, a common expression for oral sex. ‘I will kneel down’, he sings, ‘and give it to them looking down’.

The lyrics to ‘Gay Messiah’ are an extreme example of sexual openness from a member of the LGBTQ community. Lake remarks upon Wainwright’s ‘gleeful’ smile at some of the more sexually explicit lines, when he first performed it on the national talk show Jimmy Kimmel Live in March 2004, and explains how the song also served as an expression of Wainwright’s opposition to the increasingly right-wing, conservative and intolerant government under George W. Bush in the post-9/11 years. By intertwining lyrical references to biblical stories, Wainwright implicitly shows his dissatisfaction with the intolerance shown by fundamentalist Christians.37

In 2007, Wainwright moved to Berlin to work on and record Release the Stars. During this period Rufus Wainwright met Jörn Weisbrodt, who at the time was working as Head of Special Projects at the Berlin Opera. The couple got engaged in late 2010, and Lorca Cohen (daughter of Leonard) gave birth to a daughter fathered by Rufus, in February 2011. Wainwright explains that when he met Weisbrodt, he began openly campaigning for legalised gay marriage in the United States. He explicitly connects this to the social climate in North America in the 2010s:

I am very aware of living in the US, of the conundrum that you can’t marry your gay partner and give him citizenship. He has to apply for a green card and he may or may not get accepted, which is annoying when you’re in a committed relationship. If we were straight, we could get married and he’d get his American passport and it would make a lot of sense.38

Until recently, in the United States of America, the legality of marriage regulation was enforced by state legislature. New York legalised same-sex marriage in November 2011, before the 2012 election. On 24 July 2012, Rufus and Jörn married at their family home in Long Island, New York State. On the 26 June 2015, the US Supreme Court ruled that same-sex marriage be legalised in all fifty states.

Conclusion