Introduction

For over thirty years public policy in the UK and elsewhere has explicitly promoted a mixed economy of social welfare services, where public bodies, private firms and third sector organisations are variously involved in shaping and delivering services (Powell, Reference Powell2019). In a mixed welfare economy, the state can provide, fund or regulate services (Hills, Reference Hills2011), but under the continuing sway of New Public Management (NPM) and quasi-market reforms from the 1990s, the guiding vision has been towards a state which purchases and regulates the delivery of public services by competing independent providers (Le Grand and Bartlett, Reference Le Grand and Bartlett1993). Successive governments across the political spectrum have encouraged and invested in the ‘third sector’ of charities, voluntary and community groups and social enterprise to engage more fully in delivering public services (Rees and Mullins, Reference Rees and Mullins2016), building on a much longer history of charitable and voluntary involvement in welfare services (Lewis, Reference Lewis, Page and Silburn1999). Recent Conservative dominated governments in the UK have continued to promote the service delivery role of the third sector, as seen in the Coalition government’s ‘Open Public Services’ agenda (HM Government, 2011), and subsequently in the minority Conservative government’s ‘Civil Society Strategy’ (HM Government, 2018).

Yet the hope of putting the resources and purported distinctive features of third sector organisations to use in improving public services has caused considerable debate. Whilst some elements of the third sector embrace or support these developments (ACEVO, 2003; 2015), others are pragmatically cautious (Blackmore et al., Reference Blackmore, Bush and Bhutta2005; Clark et al., Reference Clark, Dobbs, Kane and Wilding2009) or openly critical (Benson, Reference Benson2014; Reference Benson2015). The debate surfaces the contested politics of the third sector, and public services. Underlying these different positions is a common representation of relatively powerless and resource-fragile third sector organisations encountering a monolithic environment of public service markets orchestrated through commissioning processes. What is missing is a more nuanced consideration of the active real-world dilemmas for different kinds of third sector organisations engaging in this area. In urging caution against entrenched debates around commissioning, Rees et al. (Reference Rees, Miller and Buckingham2017: 191) note a lack of empirical evidence and call for ‘further grounded research into the realities of commissioning especially at the local level’.

There is gathering recognition that third sector participation in public services does not occur on a level playing field. The ‘third sector’ is not a homogenous entity but a diverse aggregation of different kinds and sized organisations. Debate has increasingly focused on the challenges faced by smaller, local, third sector organisations, squeezed by competition from larger, national organisations and private companies. The Government’s Civil Society Strategy, for example, argues that the current public service delivery model favours large companies who can navigate complex commissioning systems, carry risk and bid competitively, whilst simultaneously failing to ‘recognise the added value that small and local organisations can bring’ such as local knowledge and support, additional resources, flexibility and commitment (HM Government, 2018: 105-6).

There is thus acknowledgement of how the public services landscape presents different opportunities and constraints for different organisations. How might this differentiated landscape be usefully conceptualised and understood? Informed by Hay (Reference Hay2002), this paper argues that the third sector is involved in a strategically selective public services commissioning environment, which operates to structure opportunities in ways which advantage some strategies and some types of organisation over others. This idea animates our attempt to make better sense of the ways in which third sector organisations variously experience and navigate a complex and ever-changing landscape of public services. Strategic selectivity, we suggest, is an approach which can embrace the complex contingencies of wider commissioning structures (‘context’) and how third sector organisations (and others) seek to shape and navigate a course through this environment (‘conduct’). Drawing from qualitative longitudinal evidence of change within the third sector, the paper seeks to contribute to our understanding of public service delivery, commissioning, and the third sector in social policy. This approach gives due attention to the agency of third sector actors and the strategies they adopt in social policy fields, without assuming that this is either even or unconstrained.

In the next section we set our argument in the context of a growing body of literature on public service commissioning and the role of the third sector. This is followed by an account of how strategic selectivity might provide some theoretical grounding to take forward contested debates in this area. Then we outline the methodological basis of the empirical research which supports our argument, before moving on to explore qualitative findings that highlight the significance of both ‘context’ and ‘conduct’ in the navigation of commissioning landscapes. We provide an extended discussion of the theoretical approach and empirical findings and reflect on their implications in conclusion.

Commissioning public services and the third sector

Allied to the New Labour government’s ‘Third Way’ promotion of a mixed welfare economy and contestability in public services, government funding of the third sector in the UK changed in both scale and form during the 2000s. It grew from a total of £10.5bn per year in 2000-01 to £16.6bn per year in 2009-10, after which it has remained fairly stable at around £16bn per year, representing in 2016-17 some 31% of total income for the sector (Hornung et al., Reference Hornung, Chan, Dobbs, Jochum, Lawson, McGarvey and Rooney2019)Footnote 1 . At the same time, the balance has shifted away from grant funding towards contracts and fees: the ratio of the aggregate value of grants to contracts and fees changed from 1:1 in 2000-01 to 1:4 by 2014-15 (Bénard et al., Reference Bénard, Davies, Dobbs, Hornung, Jochum, Lawson and McGarvey2018). The government’s financial presence in the third sector is, however, concentrated in larger organisations and those operating primarily in the fields of core public services (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Dobbs, Kane and Wilding2009).

The deepening relationship between the state and the third sector during the New Labour years was part of a wider trend in the development of competitive tendering and quasi markets from the late 1980s (Rees, Reference Rees2014; Sturgess, Reference Sturgess2018). Since then a complex public service market architecture has been constructed, involving new models, systems, occupational structures and training for the commissioning and procurement of public services (Bovaird et al., Reference Bovaird, Briggs and Willis2014). A substantial research, policy and practice literature has developed around commissioning generally and on the experience of third sector organisations in particular. Commissioning is often held to be a broader process of coordinating services to solve social problems or meet needs, rather than simply the procurement of services through tendering and contracts. However, the notion of a rational commissioning cycle – moving sequentially through understanding needs and identifying priorities, developing proposed outcomes, organising and investing in suitable responses, and evaluating results – appears to act more as a heuristic device than a description of practice (Rees, Reference Rees2014). In the conflation of ‘commissioning’ with ‘procurement’, it is argued, a range of options for organising the delivery of services are closed off. Grounded research on commissioning identifies much more varied, fragmented and contested practices than suggested in strategic documents and diagrammatic representations of the process (Bovaird et al., Reference Bovaird, Briggs and Willis2014; Miller and Rees, Reference Miller and Rees2014; Rees et al., Reference Rees, Miller and Buckingham2017).

Much of the literature on third sector involvement in commissioning and public service delivery reports the challenges faced by many third sector organisations. Concerns gravitate towards two poles: a set of operational challenges and a deeper set of existential anxieties. First, research points to a range of difficulties gaining access to and maintaining positions within public service commissioning systems (Martikke and Moxham, Reference Martikke and Moxham2010; Lloyds Bank Foundation for England and Wales, 2016; Aiken and Harris, Reference Aiken and Harris2017). The concern is whether commissioning and procurement processes prevent many third sector organisations from playing a full and meaningful part in public service delivery. This could be through tendering requirements, such as track records, quality assurance systems and balance sheets which act to preclude many organisations from engagement. Or it could be through doubts about the managerial and operational capabilities required to deliver and account for complex services with demanding output or outcome expectations on reduced budgets. These concerns invariably lead to calls for a variety of reforms to structures, systems and payment mechanisms, alongside investment in awareness raising, training and capacity building support for third sector organisations and commissioners alike (Gash et al., Reference Gash, Panchamia, Sams and Hotson2013).

A second set of concerns strike more fundamentally at the contested heart of what it means to be a third sector organisation. Anxieties concentrate on how involvement threatens valued and distinctive qualities associated with third sector activity, such as independence, a purported collaborative ethos, flexibility and close relationships with service users, advocacy and commitment to organisational missions (Buckingham, Reference Buckingham2009; Milbourne, Reference Milbourne2013; Milbourne and Cushman, Reference Milbourne and Cushman2015; Civil Exchange, 2016). Taking on contracts for public services, it is suggested, enables commissioners to determine third sector activities and formalises relationships with service users, intensifies competition, involves formal or tacit ‘gagging’ relationships and risks mission drift. These concerns are more intractable, and often become the well-spring for more critical interventions raising searching questions about commissioning and public service delivery in principle.

The empirical literature on third sector experiences of commissioning has been remarkably consistent over time. The same pattern of experiences recurs, albeit in slightly different sets of circumstances, which may give some confidence in the findings. However, there are some common limitations. Methodologically, most studies provide only cross-sectional pictures. There is often also an implied normative framing at work, favouring collaboration over competition. Further, an explicit theoretical grounding seems to be absent in many contributions, which restricts the possibilities for deeper understanding of the structures, contexts and processes at work. An exception is provided by Milbourne and Cushman (Reference Milbourne and Cushman2015), who draw on theories of isomorphism and governmentality to identify worrying overarching trajectories of change and fragmentation for the third sector, as a consequence of involvement in commissioned public services. However, the authors recognise the limitations of these theoretical framings, in that they readily gloss over ‘the complexity of responses visible at the level of everyday organisational dilemmas and activities’ (Milbourne and Cushman, Reference Milbourne and Cushman2015: 482). Arguably, critical accounts of the ‘big picture’ overlook differentiated practices, experiences, dilemmas and positionings, and pay insufficient attention to agency within third sector organisational contexts (Buckingham, Reference Buckingham2012). This paper responds to this gap.

Strategic selectivity

There is a need for a framework, then, that can allow for a keener sense of the interplay between context – of how commissioning shapes action and experience – and conduct – an appreciation of the dilemmas and decisions of differently positioned and resourced actors within this. For this we turn to the concept of ‘strategic selectivity’, formulated by the political scientist Colin Hay in order to highlight the iterative relationship between ‘structure’ (context) and ‘strategy’ (conduct), and particularly the opening up and closing down of political and institutional possibilities (Hay, Reference Hay2002). For our purposes, ‘strategic selectivity’ involves four inter-related assumptions which together help provide deeper insight into commissioning processes and, in this case, third sector experiences.

First, the context or environment is ‘strategically selective’ in that it ‘presents an unevenly contoured terrain which favours certain strategies over others and hence selects for certain outcomes while militating against others’ (Hay, Reference Hay2002: 129). Context is not an overwhelming grid of given power relationships which predetermines some outcomes and forecloses others. Rather, it is presented as a complex, actively shaped institutional environment which offers an uneven array of opportunities and constraints. Some actors, narratives and strategies are privileged and rewarded, and others disadvantaged and penalised, but actors work strategically both within and on that selective context.

Second, then, actors are viewed as at least partly strategic, in as much as they can develop and revise skilled ways of realising their intentions and pursuing their interests, whether these are framed as normative causes or instrumental positioning. As Hay suggests: ‘It is the intention to realise certain outcomes and objectives which motivates action. Yet for that action to have any chance of realising such intentions, it must be informed by a strategic assessment of the relevant context in which strategy occurs and upon which it subsequently impinges’ (Hay, Reference Hay2002: 129).

Third, actors are regarded as being more or less oriented to the context, such that they attempt to read and understand the rules, ways of working and possibilities for action: ‘to act strategically is to project the likely consequences of different courses of action and, in turn, to judge the contours of the terrain’ (Hay, Reference Hay2002: 132). This reading of context can only ever be partial, fallible and ‘sense-made’. It is never directly apprehended by actors but always discursively mediated, interpreted and translated: ‘actors have no direct knowledge of the selectivity of the context they inhabit. Rather they must rely upon on understandings of the context…which are, at best, fallible. Nonetheless some understandings are likely to prove more credible given past experience than others…. Context comes to exert a discursive selectivity upon the understandings actors hold about it’ (Hay, Reference Hay2002: 212).

Finally, action may have direct intended and unintended effects on the context, but it also leads to strategic learning. Actors are reflexive, such that, again fallibly, they ‘routinely monitor the consequences of their action (assessing the impact of previous strategies, and their success or failure in securing prior objectives)’ (Hay, Reference Hay2002: 133). Strategic action is then reformulated through ongoing interpretations of a changing context alongside learning about constraints, enabling factors and skilled approaches.

The concept of strategic selectivity was developed as a general recursive model of strategic action in political environments, helping to explore the ‘asymmetries of access and power in particular institutional terrains’ (Raza, Reference Raza2016: 216). It arose out of the broader ‘strategic-relational’ view of the state, which offers the basis for a complex macro-analysis of the political economy of contemporary capitalist societies (Jessop, Reference Jessop2016). This approach has been influential in macro social policy scholarship through Jessop’s analysis of welfare state restructuring, accounting for the shift from a Keynesian welfare national state to a Schumpeterian workfare post-national regime (Jessop, 2000; Reference Jessop2002). ‘Strategic selectivity’ has been applied in discussions of local environmental politics (Jonas et al., Reference Jonas, While and Gibbs2004), higher education (Dickhaus, Reference Dickhaus2010) and trade liberalisation (Raza, Reference Raza2016), but to our knowledge has not so far informed more detailed analysis of social policy or questions of public management.

Our use of ‘strategic selectivity’ to illuminate the world of third sector navigations of public service commissioning involves its application at a more concrete, meso-level. Strategic selectivity helps us in understanding how differently positioned third sector actors are making strategic assessments of (what they perceive to be) the relevant contexts in which they operate, forming judgements about what matters most and what the likely consequences of the different courses of action available to them might be. Here, context can be presumed to refer to any configuration of policies, institutional architectures, cultures and organisational arenas, in which participants are relationally positioned, oriented towards and conduct themselves. Third sector organisations are involved in effortful attempts to understand the strategically selective ‘rules’ of the various fields in which they operate and to seek convincing ways of navigating a journey through them. In doing so, they shape the context of which they are a part. The framework, we believe, makes way for understanding differential, situational and contingent third sector experiences, in which conduct and context are inherently interlinked, without losing sight of the wider picture.

We use the framework first through case study narratives to explore how different aspects of conduct and context play out within the field of third sector commissioning. We develop it further within the discussion section through an analysis of our data against the four assumptions within strategic selectivity outlined above, and a consideration of how this adds to existing literature.

Methods

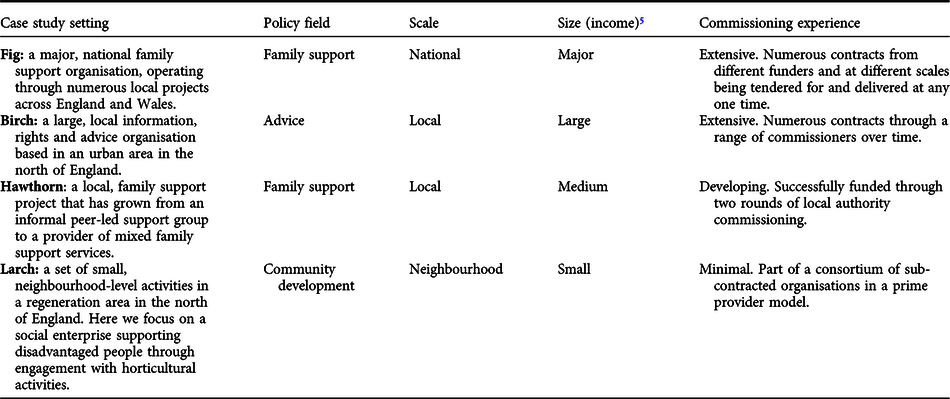

We draw on data from a qualitative longitudinal study of change within the third sectorFootnote 2 . Qualitative longitudinal research enriches our understanding of “the processes by which change occurs, and the agency of individuals in shaping or accommodating to these processes” (Neale et al., Reference Neale, Henwood and Holland2012: 5). It emphasises the importance of longer-term journeys for understanding current positions and possibilities, and so supports our interest in the experience of third sector organisations in navigating strategically selective commissioning environments. The study explores change within and around third sector organisations in four contrasting case study settings in England. These were originally selected, in an earlier phase of research, for diversity in terms of geographical spread, size, scope, and field (Macmillan, Reference Macmillan2011; Macmillan et al., Reference Macmillan, Taylor, Arvidson, Soteri-Proctor and Teasdale2013). Table 1 provides summary information about the four cases.

TABLE 1. Third sector commissioning experiences – summary information for four cases

The research involved three waves of fieldwork in each of the cases, during 2017, 2018 and 2019. Data was mainly collected through interviews with a range of respondents, including trustees, chief executives, staff, volunteers, service users, partners, competitors and funders. The dataset contains over 120 transcripts of interviews, including repeat interviews with the same individuals. All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. These were supplemented by the collection of background information, such as annual reports and other strategic documents, along with observations during regular visits to the fieldwork sites and attendance at various organisational meetings throughout the study period. Additionally, as indicated above, the current research builds on an earlier phase of research which commenced in 2010. Altogether, the organisations have been engaged in the research for approaching ten years, providing considerable temporal depth.

Qualitative longitudinal research enables researchers to explore how issues may unfold over time. Commissioning emerged as an important theme within the analysis of our first wave of interviews. It was then pursued as a line of enquiry within subsequent waves of fieldwork, and as a ‘through line’ (Saldana, Reference Saldana2003) within our analysis. We undertook further analysis with a sub-set of 40 interviews from across our four cases which focused most intensely on commissioning – including those with key staff, their partners and funders (e.g. commissioners). Following Thomson (Reference Thomson2007: 580) our further analysis involved ‘the analytic practice of reading data in two directions’, first by following and (re)constructing the commissioning stories of each of our individual cases over time, and second, bringing the cases into conversation with each other. Both ‘readings’ were guided by the analytical framework provided by Hay’s account of strategic selectivity. This is framed by and situated within our wider analysis of the full dataset, reflecting a qualitative longitudinal approach which allows for the ‘intermeshing of synchronic and diachronic, cross-cutting and longitudinal analyses’ (Neale et al., Reference Neale, Henwood and Holland2012: 5). Together this analysis provides new insights into the dynamic interplay of context and conduct within the third sector commissioning environment, highlighting both the shifting dynamics of the strategically selective context and the ways in which organisations have navigated and shaped it. The qualitative longitudinal approach allowed for an appreciation of the increasing significance of commissioning in each of the cases over time – we were able to observe how the context was shifting and becoming more salient. It also allowed for an understanding of how organisations had developed over time – we had followed their journeys as they navigated their way to get to the positions they were currently in.

Findings

How then does strategic selectivity work in practice in understanding the experience of third sector organisations engaging in the commissioning of public services? Our findings suggest that the commissioning environment represents a set of circumstances, rules, constraints and parameters within which third sector organisations operate when trying to access the resources they require to do the things they want to do. These revolve around commissioning processes, including: pre-tender opportunities and commissioner capabilities; tender specifications, particularly in terms of financial and geographical scale; and contract terms and conditions, particularly partnership and staffing requirements. We suggest that these contextual factors work together to create a strategically selective environment which favours some organisations, and some responses, more than others.

Our findings also highlight the significance of ‘strategic action’ – of the choices organisations make, and the strategies and tactics they adopt. These aspects of ‘conduct’ are highlighted through four specific dimensions associated with commissioning, which we illustrate through four contrasting case study accounts. These cover: shaping commissioning contexts before tenders are issued; assessing risks in order to decide whether or not to bid for a tender; considering when to work in partnership, and when to compete; and finally when and how to adapt internal structures and behaviours to deliver contracts.

Case study research in general is valued for its ability to capture complexity and multiplicity of themes. Here we use our cases parsimoniously, by using each one to illustrate a particular dimension of ‘conduct’ while also weaving in significant aspects of the ‘context’ – maintaining the integrity of case stories whilst also allowing cross-case analysis. Each, however, highlights additional elements of both context and conduct, not least because the two are inseparable. We return to the interplay of conduct and context, and to each of the assumptions within Hay’s conception of ‘strategic selectivity’, within the discussion section.

1. Shaping commissioning contexts

Third sector organisations are often assumed to be relatively fragile, resource constrained and rather powerless in the wider fields of public service delivery. It is important, though, not to overlook the explicit ways in which third sector actors seek to shape the context – through campaigning, lobbying and influencing public opinion – but also in sometimes quite subtle micro interventions in their local contexts. These can lay the ground for emerging path dependencies; the context is shaped and sets the parameters within which actors subsequently operate. The recent experience of case study ‘Birch’ demonstrates how third sector organisations are differentially positioned within strategically selective environments, but also how they can shape the commissioning context in ways which affect the development of tender specifications to which they may later respond.

Like many local advice centres, Birch has experienced the sharp end of austerity. Over the past ten years it has faced cycles of relative stability and vulnerability as funding has come and gone, with associated rounds of redundancy, restructuring and new recruitment (reflecting on this, one respondent noted: ‘it’s what it’s like in many voluntary organisations, I think it’s a sort of a symptom of our times really’). In 2015 its local authority proposed to withdraw all funding for advice services across the city. While the local authority contract previously held by Birch was not its most significant financially, it was symbolically important and losing it would be a ‘big deal’. Few other funders supported generalist, open door, advice. The proposed loss of funding potentially affected many organisations, sending shock waves across the advice sector in the city. As one advice provider reflected: ‘there was such a storm kicked up’.

Birch, as the largest and most significant advice centre in the area, worked behind the scenes with supportive councillors to try to save the funding. A working group to develop a longer-term advice services strategy for the city was established, and Birch took the lead on working with others to write the strategy. It made suggestions about how best to save money, including the proposal that advice services should gradually shift from face-to-face to telephone and web-based provision. The local authority followed the recommendations of the new strategy, including re-commissioning advice services. The tender specified that only one contract would be awarded (previously there had been a series of contracts with a number of individual providers), with a preference for a consortium approach, and included targets for how quickly the ‘channel shift’ move from face-to-face to telephone services should be implemented. Birch won the contract, leading a partnership with three other advice agencies. While Birch was able to draw on its various resources to challenge the original decision, develop the strategy and ultimately win the new tender along with a small number of partners, other advice providers in the city were less well positioned to be able to respond.

As the contract was delivered, and as our research followed the organisation through time, staff discussed the move from face-to-face to telephone advice. The story of ‘channel shift’ told by members of Birch initially highlighted how the organisation was responding to the stipulations of this latest contract with the local authority; that the change was the result of the wider commissioning context. Yet deeper research engagement revealed a more nuanced account of the organisation’s agency in shaping the strategic context in which its operational decisions are being made:

“it’s what we’ve put in the advice strategy as a group of partners, and the council have bought into, it’s about where things are moving to generally” (B1, 017).

It had the existing position, resources and skills to remain embedded in a set of relationships with other agencies and stakeholders, such that it was able both to lobby to protect some funding from the local authority and lead the development of the forward strategy for advice services. In doing so it was actively involved in shaping the context in which it and other actors, including the local authority, found themselves. It helped mould the selectivity of that context.

2. Assessing risks and deciding whether to bid

‘Fig’ was also involved in actively shaping the commissioning context, at both local and national level, but here we use it as an example of the ways in which organisations demonstrate agency through assessing risks in order to decide whether or not to bid for a tender. Fig grew steadily during the New Labour period and became significantly reliant on statutory sources of income. The first part of the 2010s was dominated by concerns about funding ‘cliff edges’ as large contracts came to an end, with associated cuts to income, services and staff. Learning from these experiences, its recent strategy has been to try and balance a small number of larger contracts with a much larger number of smaller contracts, and to position itself as a specialist provider:

“It’s partly reflecting opportunities in the market…it’s partly about financial risk analysis, in as much as I would prefer the organisation to be specialist, neat, niche, edgy, doing risky services, you know, doing the services that others might be less confident to touch rather than doing massive multimillion contracts which are easier to cut and create cliff edges in the organisation …” (F1, 014).

Significant organisational resources are invested in an ongoing assessment of both the environment and the performance of individual contracts, identifying future funding opportunities, building relationships, and developing, refining and reformulating responses. Structures and processes are designed to be ‘agile’ allowing the organisation to continually (re)position itself to ‘take advantage’ of new funding streams as they come on board. A sophisticated process has been put in place to respond to new tender opportunities, with specialist teams (including business development and legal support) dedicated to the task of rigorous assessment against a detailed set of criteria for judging organisational fit and risk. This strategy has helped to strengthen Fig’s position and re-secure a healthy financial trajectory.

Across our cases it was reported that contracts have grown in scale, scope and complexity over recent years, signalling a more demanding commissioning environment. Fig’s resources – both financial and human – give it the capacity and capability to make careful judgments about the context within which it operates, including when and how to engage with commissioners, which contracts to go for and which to avoid, and when to walk away. These resources offer greater possibilities for autonomy and influence. The need for thorough assessments highlights the relatively advantageous position of larger third sector organisations, such as Fig, within a strategically selective environment.

The ability and willingness to walk away from contracts at different stages of (re)tender and delivery is an important real and symbolic demonstration of agency:

“we’re not afraid to say “no” and we also say “no” to things that we are the existing provider of […] It is ultimately a commercial decision, but it is also about being able to deliver to our values…” (F2, 083).

In actively seeking other sources of funding and investing its own reserves in supporting new service developments, Fig had been further managing the constraints of commissioning, and in doing so hoping to ‘take back some control’. Such strategic actions both respond to and shape the commissioning environment, at times contributing to commissioners revisiting and revising their approaches.

3. Partnership and/or competition

In Fig’s judgment, a period of intense competition with other providers has begun to give way to more partnership working. Here it is navigating complex sets of relationships not just with commissioners but also with other providers, while constantly jostling for position within the field of family support services. Fig’s scale, resources and reach open partnership opportunities up, but can also serve to close them down – through being viewed as a competitive threat by both small local organisations (for example, we heard concern about national organisations who ‘swoop in and …take all the money’) and in relation to other large national organisations.

At the same time, smaller third sector organisations struggle to engage in a commissioning environment that favours organisations and strategies which can work across a broader scale. A common recommendation is to build scale through partnerships with others, for example by forming a consortium to bid for contracts or becoming a sub-contracted supplier of services to larger ‘prime contractor’ organisations. The horticultural social enterprise in ‘Larch’ highlights some of these challenges and responses to them. It was established in 2010 to engage disadvantaged people in therapeutic horticulture and has achieved considerable success in terms of building a diverse funding and reputational base.

Growth, however, has been relative. It remains a ‘small’ organisation, which has shaped its ability to work within existing rules of the commissioning environment: while it operates on a very local scale, commissioning often doesn’t. Ever larger contracts – both in geographic and financial terms – have precluded it from bidding, compounded by riskier contract terms and conditions, such as payment by results and TUPEFootnote 3 stipulations. As one member of staff from Larch reflected:

“when you tender it’s a far more complex process [than applying for grants] and it’s really very rigid. So, tendering is awful and it’s all the big boys that are gobbling up the tendering now” (L2, 069).

Judging that a ‘go it alone’ strategy would be futile, the social enterprise made partnership arrangements with other local providers, including working as part of a consortium of organisations sub-contracted to a prime provider within a large commissioned service. Working with others has enabled it to engage with commissioning but has been the source of considerable frustration as neither funding nor referrals have flowed as anticipated through the supply chain. The organisation has been rendered relatively powerless, with little room for manoeuvre within contract terms that were not of its choosing:

“I’m really unhappy about consortiums […] [T]he money doesn’t trickle down […] you get one prime provider, one lead organisation, they gobble up everything. They take all the money.” (L1, 034).

Rather than simply accepting the constraints imposed by its unfavourable position within a selective commissioning landscape, however, the social enterprise has exploited other opportunities afforded by being locally well-networked and well-respected. In response to a new tender specification, which was thought to favour much larger organisations, the CEO invited the commissioner to visit the social enterprise and observe first-hand the outcomes it (and, by implication, other small organisations) achieves, in an attempt to over-turn the contract rules and requirements and make their engagement a possibility.

These experiences highlight both the strategically selective nature of the commissioning environment in which third sector organisations operate – sometimes favouring strategies of partnership and sometimes competition, whilst also tending to favour large organisations over small – and the strategic action of those organisations, constantly adapting and shaping that context on different levels.

4. Developing internal structures and behaviours

Third sector organisations also often adapt their internal structures and behaviours to maximise the opportunities available to them within the commissioning environment. ‘Hawthorn’ was established in 2004 as an informal, volunteer-run, family support organisation, but over time it has expanded, supported by grant funding and a local authority contract. In the process it has introduced more formal structures and sought to develop a ‘professional’ ethos, gaining and maintaining a position as a reputable service provider locally. Hawthorn’s recent experience highlights how key strategic decisions by commissioning bodies fundamentally alter the landscape of constraints and opportunities experienced by third sector organisations, and the dilemmas and responses this can contribute to.

Between 2017 and 2019 Hawthorn’s attention was dominated by a (re)commissioning processes for family support services. Under the promise of economies of scale, the local authority initially proposed to bring several services together in a large tender covering a wider range of service users and across the whole County. Hawthorn was disadvantaged by this decision: it worked only at district level, and it could not meet the anticipated demands of delivering such a large contract on its own. The proposed contract appeared to favour larger or national private and third sector organisations. Faced with losing its existing work through this, it sought (like the social enterprise in Larch) to compensate for its lack of scale: it began to build collaborative links with similar organisations in other districts, to see if a consortium bid might be possible, but also it developed promotional materials to showcase its approach to larger bidders, in the hope of securing a local sub-contract.

Late in the process, however, commissioners gained internal local authority approval to disaggregate the proposed tender into district-based lots, responding to concern that the existing approach would undermine local voluntary sector provision. At once the landscape of possibility for Hawthorn had changed. Smaller local organisations found themselves in a more advantageous position, whereas larger organisations from elsewhere might judge the new contracts as too small to be worth tendering for. Hawthorn was now in a highly competitive position to bid for its district-based contract alone: it no longer needed to market itself to other potential providers, and the impetus behind a consortium bid subsided. The landscape was selecting for certain organisations and strategies over others. However, other proposed terms of the tender, particularly a proposed ‘payment by results’ mechanism, would prove to be more challenging for a relatively small organisation with limited capacity, expertise and working capital. Without the sophisticated expert capacity evident in Fig, Hawthorn’s managers and trustees had to set prices for the work by assessing and forecasting the likely numbers of families they would support, the resultant up-front staffing and other costs, and the chances of gaining successful ‘outcomes’ from which payments would be triggered.

Hawthorn’s tender was successful. The initial excitement of success after several stressful months of preparation was, however, quickly replaced by the anxiety of delivery. Hawthorn had felt little option but to bid for (what they had assessed to be) a risky contract with borderline viability. But with a reduction in targeted client numbers, difficulties demonstrating evidence of outcomes and payment in arrears, the challenges of retaining and motivating staff have intensified. Staff morale is at its lowest ebb in a working environment now characterised by the need to meet targets and complete paperwork. The worry across the organisation is whether all the effort has been worth it, and whether it is now rapidly losing its charitable ethos of flexible, relational work alongside clients:

“sometimes our hands are tied […] we’ve got to deliver this number of sessions for this family, and we can’t do all of the nice stuff that we used to do for families” (H2, 088).

Respondents discuss the risk of becoming less like a charity and more like a ‘cheap department of the county council – they set the targets, tell us how high to jump’. Having been in a position to win the contract, Hawthorn is now considering withdrawing from it. Just raising this possibility is helping to rebuild a sense of agency:

“I think the fact that the organisation’s already stopping and starting to think, “Do we back out of this?” is a positive. Because you always feel better don’t you, when you feel you’re in control of something, rather than your destiny being controlled by somebody else. Which is how it feels at the moment” (H2, 087).

Discussion

As public policy continues to develop sophisticated processes for commissioning public services, existing literature has highlighted the struggles facing third sector organisations participating in such an environment (Rees et al., Reference Rees, Miller and Buckingham2017). We add weight to these findings by evidencing the considerable challenges and frustrations that third sector organisations encounter within commissioning. It is resource intensive, requires organisations to have or invest in specific skills and expertise (in, for example, business development, marketing, impact measurement and partnership working), and it can contribute to a heightened sense of competition amongst third sector organisationsFootnote 4 .

The extant literature, however, tends to suggest that third sector organisations are passive ‘takers’ of a commissioning environment driven from elsewhere (Milbourne and Cushman, Reference Milbourne and Cushman2015). In response, they are sometimes encouraged to build their capacity to engage more effectively in commissioning, in effect to become more like larger organisations. Alternatively, they might opt out of public service delivery insofar as it is beyond their reach or poses too much of a threat to their values and principles. Our research, however, shines some light on otherwise overlooked aspects of third sector organisations in a commissioned public services environment. The theoretical approach and qualitative longitudinal analysis have enabled a more nuanced understanding of the granular experiences of different third sector organisations in navigating the commissioning environment. The approach draws attention both to the uneven landscape through which third sector organisations are travelling, but also their agency in pursuing strategies to improve their position and prospects. It attends to both ‘context’ and ‘conduct’.

Returning to the four assumptions at the heart of the idea of ‘strategic selectivity’, discussed earlier, emphasises the ways in which actors encounter and act within strategically selective commissioning environments. The first assumption is that a strategically selective environment represents a set of circumstances, rules, constraints and parameters within which third sector and other actors operate and which favours certain strategies and organisations over others. Of particular significance were: first, the financial and geographical scale of tender specifications, alongside size thresholds precluding smaller organisations from bidding; second, contract terms and conditions, such as payment by results and TUPE requirements; and third, the sheer complexity of commissioning processes. Most of these parameters tend to operate in favour of larger organisations, with more resources available to bid successfully and to organise large scale delivery over a broader geographical scale. There are of course countertendencies and examples, such as attempts to tailor contracts specifically to enable smaller organisations to participate. Overall, however, current commissioning environments tend to select for strategies which favour those with existing or ready access to resources, such as investing in business development, competitive pricing, and supplementing bids with additional charitable resources.

Yet organisations do not passively respond to this strategically selective environment. The case accounts also highlight the significance of conduct – the strategic action of third sector organisations. They are involved in shaping the context, as well as being shaped by it. The second assumption, then, is that actors are at least partly strategic. They seek to use what skills, experience and knowledge they can muster to understand the contexts in which they operate and through which to pursue their interests. All four of our cases were constantly reviewing and assessing their operating environments and devising and resetting strategies in this light. But each had different capacities and capabilities to do so. Fig’s financial and human resources, for example, enable a much more sophisticated and thorough assessment of the varied contexts in which it works or seeks to work, and arguably a wider range of options to pursue. Smaller organisations are more constrained in the strategic choices they have, and the resources to hand in making those choices. The social enterprise in Larch was pushed towards a strategy of seeking to join a supply chain led by another organisation because it did not have the capacity to bid alone for work it wanted to do. Hawthorn was in a similar situation until the contextual rules around it changed to favour smaller, local third sector organisations.

Third, actors are assumed to be more or less orientated to the context. They seek to interpret and understand the rules, ways of working and possibilities for action, but readings of context are only ever partial. Two comparisons help demonstrate this. Fig and Hawthorn are both involved in family support, but at different organisational and geographical scales. Fig operates at national level and in lots of different localities. It can engage in and make sense of wider policies, developments and trends, as well as gain grounded insights from its local work. It uses this as part of its highly developed approach to business development. Hawthorn operates only in a single district within a larger county. It has less access to and knowledge of wider developments and trends, but has deeper knowledge of local conditions, practices and politics. It followed closely the emerging messages about the County Council’s commissioning plans and initially sought to showcase its work and connections to potential large prime providers. Yet it was anxious throughout the process to find out more, including how the commissioning would work and who the prospective bidders would be.

This leads to a second comparison. Both Hawthorn and the social enterprise in Larch are relatively small organisations struggling to gain footholds in their commissioning environments. But the extent to which they are oriented towards their contexts differs. The commissioning process for Hawthorn mattered a great deal. It felt compelled to be involved given the importance of this funding stream for its work. In Larch, by contrast, the social enterprise was involved in multiple activities funded through a range of different sources. It was somewhat less attuned to its commissioning context, and more oriented to other contextual dimensions, including the lives and circumstances of its volunteers and other community developments in its neighbourhood.

The final assumption in strategic selectivity is that action may have direct intended and unintended effects on context, but it also leads to learning, as actors routinely monitor the consequences of their decisions and strategies. All our cases were involved in indirect efforts to shape the contexts in which they work, which led to significant consequences: Birch, for example, led the development of a strategy which ultimately contributed to a change in how it delivers services, whilst Hawthorn engaged in local efforts to challenge the decision to procure services on a County wide basis, such that the decision’s reversal opened up possibilities for it to win resources. Qualitative longitudinal research engagement with the organisations allowed for a closer real time appreciation of the unfolding of events, and how the organisations learn from their experiences, if not always in positive ways. Hawthorn’s success in winning its tender, for example, has generated greater ambivalence once the realities and consequences of delivery have materialised. It is now considering whether to withdraw from the contract. The social enterprise in Larch has learnt by painful experience that supply chains do not always live up to their promise. Birch and Fig have learnt about and mitigated the risks of larger contracts, including the exploration of alternative models of financing services.

Conclusions

Much has been written about the difficult encounters many third sector organisations have with public service commissioning, yet overall the literature tends to lack the theoretical grounding through which to make sense of these processes and experiences. This paper contributes to the literature, and to broader debates around commissioning and public services, by deploying the idea of ‘strategic selectivity’ to shed theoretical light both on the differentiated experiences of third sector organisations and on the ways they seek to navigate pathways through an uneven commissioning landscape. Strategic selectivity offers a way of understanding how differently positioned organisations seek to read, travel through and transform that landscape. Third sector organisations cannot credibly be regarded as passive and powerless in the contexts in which they work. In principle these contexts are malleable, yet at the same time the approach avoids heroic assumptions about how much change can be effected, and acknowledges that actors are differently positioned within their contexts.

Our analysis suggests several implications for policy, practice and research. If policy makers and commissioners are as committed to engaging the third sector in the delivery of public services as general rhetoric suggests, acknowledging the unevenness of the commissioning landscape, and the implications of the rules and parameters which they create, would be a good starting point. The findings should give third sector organisations some confidence in their ability to influence the environments in which they are operating; to recognise themselves as strategic actors, with the ability to shape – and not just be shaped by – the opportunities and constrains which the commissioning environment offers.

It is also worth reflecting on the advantages and limitations of applying a ‘strategic selectivity’ lens in social policy analysis. To our knowledge it has not been used in any detail in this area, and references to it in social policy and other disciplines tend to use it to inform fairly high level and abstract discussion of the role and complex functioning of the (welfare) state in contemporary capitalism. Our approach has involved rendering the idea of strategic selectivity in concrete form, here in the case of commissioning public services. Doing so extends the reach and relevance of the concept. Our qualitative longitudinal analysis of third sector experiences has given temporal depth and detail to an otherwise cyclical dynamic of the interplay between context and conduct. Our approach also highlights limitations. There is some tension over the notion of ‘context’, seen on the one hand as rather abstract and singular, but on the other in the idea of a more concrete, multiple, and complex array of different inter-related contexts through which actors travel. A more plural conception of context would suggest that further research might explore the different strategically selective dynamics in play in specific fields of social policy activity, such as children’s services, criminal justice or social care, and to investigate and compare the interplay of context and conduct over time in these fields. Empirical testing in different fields could then lead to further development of strategic selectivity as a theoretical approach.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Economic and Social Research Council (award number ES/N010582/1) for supporting the research upon which this article is based. They would also like to thank all of the interviewees who have taken part in the ‘Change in the Making’ study.