Introduction

Traumatic injuries are the leading cause of death in individuals up to the age of 45 years and the third overall leading cause of death in the United States (US). 1 They contribute significantly to the burden of diseases accounting for approximately 40 million emergency department (ED) visits and more than 169,000 deaths annually. 1,2

Prehospital therapeutic interventions were previously found to reduce mortality in patients with out-of-hospital cardiac and respiratory arrests, but not in trauma, with many studies showing a direct correlation between mortality and increased number of prehospital interventions. Reference Eisenberg, Bergner and Hallstrom3–Reference Bieler, Paffrath and Schmidt7

Many out-of-hospital factors contribute to mortality in trauma patients making this population widely heterogeneous. Identifying these factors and assessing their impact on trauma patients is key in improving out-of-hospital care and patients’ survival. The heterogeneity of trauma patients dictates different approaches, making both the “scoop and run” concept and the “stay and stabilize” concept valid in the right context.

Penetrating trauma represents approximately 15% of all major trauma world-wide and between 20%-45% of all major trauma in the US. Reference Soreide8 It is a condition where a rapid surgical intervention is needed in most cases. This highlights the importance of a shorter prehospital time and minimal prehospital interventions. When comparing transportation of penetrating trauma patients via Emergency Medical Services (EMS) and non-EMS (police and private transport), an improvement in mortality was found in sick patients transported via non-EMS, or at least no improvement in outcome when patients were transported via EMS. Reference Band, Salhi, Holena, Powell, Branas and Carr9–Reference Wandling, Nathens, Shapiro and Haut11 This better outcome might be attributed to the limited interventions and short prehospital time when transported via non-EMS.

Police units, who often reach the trauma scene before EMS and provide limited on-scene medical care, Reference Cornwell, Belzberg and Hennigan12 can potentially lead to shorter prehospital times and better outcomes in patients with penetrating injury. A recent study using the US National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB; American College of Surgeons; Chicago, Illinois USA) showed a high survival rate (93.5%) for trauma patients who were transported by police when compared to previous survival rates of trauma patients transported by EMS in other studies. Reference Colnaric, Bachir and El Sayed13

Current evidence regarding penetrating trauma patient outcomes in police transport (PT) is scarce. Previous studies showed that PT of penetrating injuries is not associated with a mortality difference when compared to EMS transport of similar injuries, Reference Zafar, Haider and Stevens10 and some showed improved survival with PT in sub-group analysis including only severely injured patients. Reference Band, Salhi, Holena, Powell, Branas and Carr9

Given the increasing utilization of non-EMS transport in prehospital trauma care and the need for more evidence-based involvement of police in penetrating trauma care and transport, this study uses the US NTDB to compare outcomes of patients with penetrating trauma according to mode of transport, police versus ground ambulance (GA).

Methods

Study Design and Population

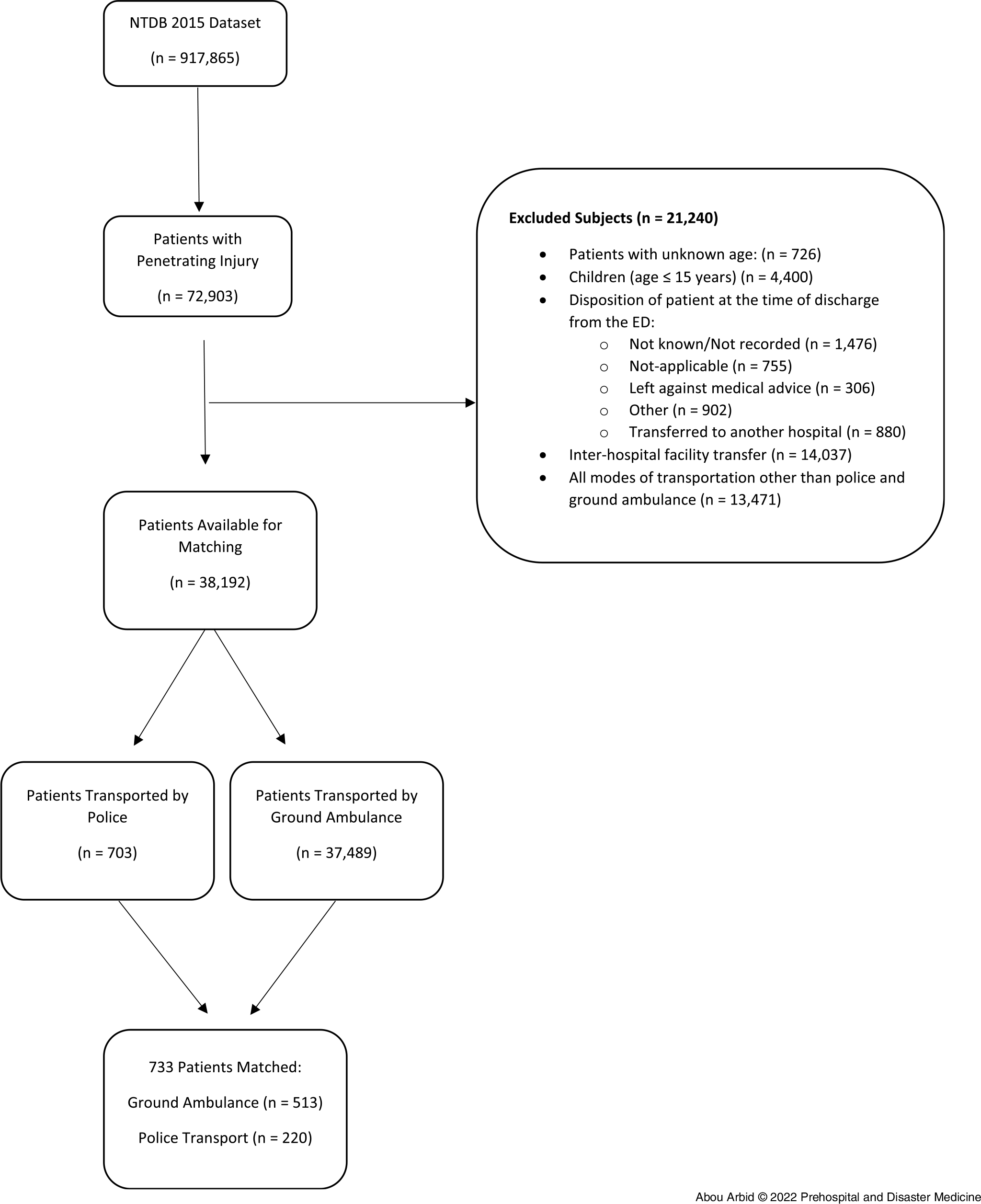

The NTDB is the largest trauma registry in the US. This retrospective study used NTDB 2015 dataset to identify trauma patients with a penetrating injury who had GA or PT from scene. The NTDB 2015 includes a total of 917,865 patients with sustained injuries. The sample selection was based on two available variables in NTDB. The first variable that indicates the type of injury for each patient and the second variable indicates which mode of transportation was used for each patient. Type of injury variable consists of: blunt/burn/penetrating and other. Mode of transportation variable includes the following categories: GA, helicopter ambulance, fixed-wing ambulance, police, private/public vehicle/walk-in, and other. The selection revealed that 72,903 patients had a penetrating injury. Exclusion criteria were patients with unknown age, those whose age ≤15 years, those with inter-hospital transfers, those with unknown/not recorded hospital discharge, and those who had unknown outcomes as ED discharge disposition (ie, not known/not recorded; not applicable; left against medical advice; discharged to jail, institutional, or mental health facility; or transferred to another hospital). A flowchart was added to illustrate the inclusion and the exclusion criteria (Figure 1). It is worth noting to mention that the sample size was not calculated because this study was based on a database, and as such, no additional patients can be included to the already collected ones. Therefore, it is not applicable for data extracted from a database to calculate the required sample size in order to have enough power to generate the study results. Nevertheless, NTDB is the largest registry of trauma patients across the US and findings of this study can be generalized to the US health care system and other similar systems.

Figure 1. Inclusion and Exclusion Flowchart.

Note: There are overlaps among the categories of the excluded variables. More specifically, some patients who had inter-hospital facility transfer had as ED disposition one of the excluded categories. Also, some patients whose age was not recorded or were 15 years or younger were transferred or had as ED disposition one of the excluded categories. These overlaps explain why the final number on which the data analysis was conducted cannot be calculated just by subtracting the number of excluded patients from the selected sample.

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; NTDB, National Trauma Data Bank.

Among the remaining patients, 703 individuals transported via police were matched (4:1) to those who were transported by GA (N = 37,489). Matching was done for the following variables: age (using an age range of ± five years); gender; race; state designation; geographic region for the hospital; comorbidity; injury intentionality as defined by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; Atlanta, Georgia USA); Injury Intentionality Matrix; International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) mechanism of injury E-code; patient’s primary method of payment; and ICD-9 body regions as defined by the Barell injury diagnosis matrix: extremities, head/neck, spine/back, torso, and unclassifiable by site; Injury Severity Score ([ISS] ≤15, ≥16); Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score at ED (severe <8, moderate 9-12, mild 13-15); and systolic blood pressure (SBP) at ED (≤90mm Hg, ≥91mm Hg). After matching, 513 patients transported by GA and 220 transported by police constituted the study sample in which the data analysis was conducted. The primary outcome was defined as survival to hospital discharge. An exemption was obtained from the institutional review board at the American University of Beirut (Beirut, Lebanon) for the use of the de-identified NTDB dataset. Therefore, institutional review board review and approval is not required for the implementation of any study from NTDB, and as such, there is no committee protocol identification number for this study.

Data Abstraction Accuracy

There are two essential references for the NTDB database and they are provided with every dataset release: (1) NTDB research data set user manual and variable description list; and (2) national trauma data standard: data dictionary. Their contents constituted the unique source of information for the study investigators to conduct this research study. They familiarized themselves with the available variables, adopted the NTDS-based definitions, and identified the limitations of the NTDB data. The manual extensively described the NTDB limitations in terms of data quality, convenience samples, selection and information bias, and missing data. These limitations were taken into account in all study phases, including the adopted criteria for the sample selection, the performed data management and analyses, and the interpreted findings. The percent of missing data was identified by carrying out a descriptive analysis for the selected variables. The internal inconsistency was determined by checking for the potential availability of any data entry errors. No inconsistencies were identified by comparing the values of the related data elements (such as mechanism of injury and trauma type).

No differences were detected in the demographic characteristics (age, gender, race, and ethnicity) between the original data selected from NTDB and the study data from which some patients were excluded based on pre-specified criteria (data not shown). This indicates that the exclusion criteria did not lead to a selection bias.

Moreover, the NTDB manual describes the approach used to improve the data quality. The data files received from the contributing hospitals are continuously screened, cleaned, and standardized by an NTDB’s edit check program/a validator.

Statistical Analyses

The data analyses were carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 24; IBM; Armonk, New York USA). Age was summarized as mean (standard deviation [SD]), median, and interquartile range (IQR). All categorical variables were presented by calculating their frequencies and percentages. The descriptive analysis indicated that the percent of missing values for the following variables (ethnicity, whether patient used alcohol, whether patient used drugs, and the patient’s primary method of payment) is greater than five percent. Multiple imputation procedures were performed to handle these missing data. Comparison between the two groups of the mode of transportation (PT versus GA) in terms of the patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics was carried out by the Pearson Chi-Square or Fisher’s Exact tests for the categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney test for the continuous variable (age). The latter test was used instead of the student’s t-test due to the violation of the normality distribution of age as revealed by the Shapiro-Wilk test and the histogram chart. Statistical significance was considered at the 0.05 level.

Results

A total of 733 matched patients met the inclusion criteria and were included in this study. Patients were divided into two groups: patients transported by GA (n = 513) and patients transported by police (n = 220). Demographic characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. The median age was 27 years (IQR: 22-33.50) with the majority of patients being male (95.6 %). Most of the patients were Black/African American (79.0%). Most patients were transported to a Level I trauma center (84.3%), followed by Level II trauma centers (12.3%). Hospital location was mostly in the northeast geographic region (67.1%), followed by the south (14.1%). The patient’s primary method of payment was Medicaid/Medicare (46.7%), followed by self-pay (30.2%), private/commercial insurance (18.4%), and others (4.8%). Clinical characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 2. More than one-half of the patients had recorded comorbidities (61.4%). Injuries resulted mainly from an assault (89.6%), followed by self-inflicted injuries (6.4%). Between the two mechanisms of injury, firearm-related injuries and cut/pierce injuries, the former was more common (68.8% and 31.2%, respectively). Open wounds were the most common type of injuries (75.7%) with the majority of overall injuries affecting the extremities and the torso (62.9% and 55.5%, respectively). Most of the patients had an ISS of <16 (88.0%). Upon arrival to the ED, most patients had a GCS of 13-15 and were hemodynamically stable with a SBP ≥ 91mmHg (95.2% and 93.5%, respectively).

Table 1. Hospital Information and Demographic Characteristics of Matched Patients Transported via Police or Ground Ambulance

Abbreviation: ACS, American College of Surgeons.

a Indicates that the Mann-Whitney test was used to calculate the P value.

b Other race includes: Asian, American Indian & Native Hawaiian, or Other Pacific Islander & Other Race.

c Indicates that the Fisher’s exact was used to calculate the P value.

Table 2. Event and Injury Characteristics of Matched Patients Transported via Police or Ground Ambulance

Abbreviation: CDC, Center for Disease Control and Prevention; ICD-9, International Classification of Diseases, ninth edition, Clinical Modification.

a Indicates that the Fisher’s exact was used to calculate the P value.

Table 3 displays outcomes by groups. Disposition of patients from the ED was similar between GA and PT (P = .957). Patients transported by GA were more likely to be discharged home at hospital disposition (84.4% versus 74.4%; P = .003) while patients transported by police were more likely to be transferred to other destination (20.5% versus 10.4%; P = .001; Table 4). A total of forty-four patients died in the ED and during admission with no significant difference in the overall survival to hospital discharge between patients transported by GA and by police (94.5% versus 92.7%; P = .343).

Table 3. Clinical Characteristics of Matched Patients Transported via Police or Ground Ambulance

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; ICD-9, International Classification of Diseases, ninth edition; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

a “Other” is the combination of the following nature of injuries: Amputations, Burns, Crush, Dislocation, Nerves, Sprains & Strains, System Wide & Late Effects, Unspecified.

b Indicates that the Fisher’s exact was used to calculate the P value.

Table 4. Emergency Department and Hospital Characteristics of Matched Patients Transported via Police or Ground Ambulance

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit.

a Indicates that the Fisher’s exact was used to calculate the P value.

Discussion

In this study, the association of police and GA transport with survival to hospital discharge was investigated in patients with penetrating injuries using the largest US national trauma data set. To adjust for confounders, PT patients were matched to GA transport patients based on significant variables. Patients with a penetrating trauma transported by police had a similar survival rate to hospital discharge when compared to patients transported by GA. The results of this study can be used to plan and support the involvement of police in the prehospital management protocols and transport in patients with penetrating trauma.

The results of this study reinforce previous findings that EMS transportation confers no survival benefit over PT. Reference Band, Salhi, Holena, Powell, Branas and Carr9,Reference Wandling, Nathens, Shapiro and Haut11,Reference Band, Pryor, Gaieski, Dickinson, Cummings and Carr14,Reference Branas, Sing and Davidson15 Research from Philadelphia (Pennsylvania USA), where the Philadelphia Police Department has a formalized trauma transport policy, showed that PT is as effective as EMS transport after adjusting for mechanism of injury and severity of injury. Reference Band, Salhi, Holena, Powell, Branas and Carr9,Reference Band, Pryor, Gaieski, Dickinson, Cummings and Carr14 A previous study assessing factors associated with survival of trauma patients transported by police showed that ISS along with other factors such as a GCS ≤ 8 and a SBP below 90mmHg were associated with lower survival to hospital discharge. Reference Colnaric, Bachir and El Sayed13

Beyond the potential medical benefits, incorporating PT of trauma patients to hospitals can be associated with positive outcomes. In previous studies out of the US, patients transported by police belonged to racial minority groups that have little confidence in their local police departments. Reference Kaufman, Jacoby and Sharoky16,17 Incorporating a life-saving role for the police may change how these communities perceive the police and can increase trust in police role. These findings were described in a study performed in Philadelphia where black patients transported by police described how it “made them feel that the police cared about their well-being and survival,” and similarly, the police perceived it as a chance to “save a lot of lives.” Reference Jacoby, Branas and Holena18 Furthermore, in countries that lack a structured EMS system and where the prevalence of shooting and penetrating injuries are high, police transportation can fill a gap in the prehospital system, improve health outcomes, and strengthen the relationship between the local communities and the police. Reference Jacoby, Reeping and Branas19

In addition to the benefits associated with PT of patients with penetrating injuries, a recent matched cohort study using NTDB and examining the association between the survival rate of blunt trauma patients and mode of transport among 2,469 patients showed results similar to this study. The overall survival rate of adult blunt trauma patients was found to be similar for police transported and EMS transported patients (99.2%; P = 1.000). Reference Sakr, Bachir and El Sayed20

Limitations

This study has some limitations. Similar to previous studies on this topic, many on-scene critical data were not available for analysis, mainly due to the complexity of collecting them. Such missing data include prehospital transport time, which can act as a potential confounder. The types of prehospital medical interventions performed by police were not analyzed in this study as they are not reported in NTDB. The NTDB dataset does not include patients declared dead at the scene and patients who were not transported to the ED, which can over-estimate the survival rate. In addition, the quality of the data included in this dataset might differ among hospitals. Nonetheless, the dataset is continuously monitored, cleaned, and reviewed to ensure the highest quality. Despite the limitations in the dataset, NTDB is the largest registry of trauma patients across the US, and findings of this study can be utilized to improve police involvement in trauma care in the prehospital system in the US and in other similar systems.

Conclusion

In this study of adult trauma patients with penetrating injuries, there was no difference in survival rate to hospital discharge among patients transported by police versus GA. As such, PT in penetrating trauma appears to be effective. Detailed protocols should be developed to further improve resource utilization and outcomes in this patient population.

Conflicts of interest/funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. No conflicts of interest declared.