Wagner first publicly unveiled the poem for the Ring cycle as a work of literature. “[It] will be … the greatest poem that has ever been written,”Footnote 1 he puffed optimistically to Theodor Uhlig in 1852, before distributing fifty printed copies. Thomas Mann had qualms on reading this sixty years later, observing that even if Wagner’s literary poems had not been written in the language of opera texts, they would still fall short of such a boast, and that such a remark – sidelining the “colossal oeuvre” of Shakespeare, Goethe, Balzac, Homer, Dante, Cervantes, Lesage, and Gogol – “could only have come from an artist whose intellect/character was depressingly incommensurate with his talent.” It is hard not to sympathize with Mann’s position. Talent alone does not make for greatness, he continues. And what is it that Wagner lacks? Literature. “It is the lack on which he prided himself all his life as a virtue, and which the Germans have likewise always regarded as a virtue in him.”Footnote 2 What he meant was that Wagner devalued “literary dramas for silent reading” in favor of “living” drama for enactment (and for this reason privately regretted distributing those printed copies of his Ring poem in 1853).Footnote 3 While the “ancillary-words” and “complicated phrases” of silent literature appealed to the imagination, Wagner argues, drama appealed to the senses. Literature was a natural consequence of “the evolution of understanding out of feeling,” that is, fruit of the very alienating process he sought to undo.Footnote 4 Such an insult might have dissuaded serious writers from engaging with Wagner’s works. It seems faintly ironic, then, that nine years before receiving the Nobel Prize in Literature (1929), Mann confessed privately, “Wagner is still the artist I understand best, and in whose shadow I continue to live.”Footnote 5 This distinction between forms of “literature” bears consideration. What about Wagner’s works and stature cast such a shadow that, despite his hostility, they put Europe’s belletrists in the shade?

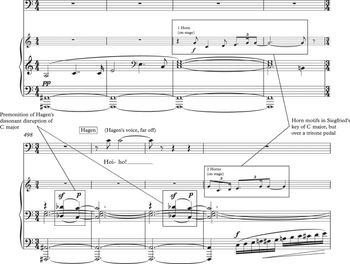

Consider another perspective. The German pedagogue and founder of the London Wagner society, Edward Dannreuther, parroted Wagner’s theoretical writings in 1872 when he declared the composer “a poet first and foremost,” pronouncing him “formidable as a writer” because he was “perfectly conscious of all his mental evolutions” and wrote about them with a cool, Goethean detachment.Footnote 6 Regardless of whether we accept this, Dannreuther gave voice to popular assumption by entitling his second book Wagner and the Reform of Opera (1873). It posited Wagner as an aggrandizing, visionary reformer who secured lasting fame since conceiving Der Ring des Nibelungen as a “stage festival play” unfettered from Franco-Italian convention, a work that eschews “conventional forms, the recitative secco and the aria” as impediments to true expression, forms that “have imposed their fetters upon every composer … [and] hampered every poet.”Footnote 7 Critical opinion was far from marshaled on the matter. But with increased performances of Wagner’s works during the late 1870s and early 80s, the results of such reform – continuing momentarily Dannreuther’s distorting cliché – appeared persuasive to a public nourished on warm critical endorsements. However unwittingly, the famed cottage industry of satirists depicting the “power” of Wagner’s reformed art only served to feed such assumptions, while skewering efforts to take his music too seriously. In the case of Faustin Betbeder’s evocation of the premiere of the Ring cycle in 1876, given in Figure 12.1, an oversized head and baton/wand whips up soundwaves into such a swirling mass that it devastates mere individuals caught in its field: Witness the ridicule of an artistic hurricane, the fruit of Wagner’s disruptive operatic reform.

Figure 12.1 Faustin Betbeder, “Wagner,” Figaro September 26, 1876.

These two strands of Wagner’s early posthumous identity – an immensely talented composer disparaging of silent literature; a reformer of opera – are inextricably entwined. In this chapter, I ask how the one relates to the other for literary writers responding to the Ring cycle. Dannreuther’s fifty-seven-column entry on Wagner for the first edition of Grove’s Dictionary, reiterated his message in primary colors: “Broadly stated, Wagner’s aim is Reform of the Opera from the standpoint of Beethoven’s music,”Footnote 8 and asserted a forcedly a neat link-up between sounds heard and words read, where Ring validated Wagner’s controversial theories of Versmelodie, thematic motifs, and orchestral commentary: “to us who have witnessed the Nibelungen … the entire book [Opera and Drama] is easy reading.”Footnote 9 Such were prominent views reflecting Wagner’s identity around the time of Mann’s birth in 1875. Accordingly, the following reflections divide into two interrelated critiques: Wagner as a reformer of opera; the Ring as a work of literary fascination.

Early Essays

Given Wagner’s legacy as a reformer, we may wonder at its origins. The so-called Young German movement – an opposition group of left-leaning writers critical of autocratic rule and sympathetic to French socialist ideals and the idea of a unified German nation – offers one background for the impulse to enact change. In his sympathies for the movement, Wagner established an early bond with Heinrich Heine, a fellow expatriate in Paris whose name had been on the Bundestag resolution of December 10, 1835 against the group’s writings.Footnote 10 Even before the twenty-one-year-old composer joined Heine in the French capital, admittedly, he writes of the need for opera to exceed its national traditions, rousing readers to “take the era by the ears, and honestly try to cultivate its modern forms; and he will be master, who writes neither Italian, nor French – nor even German.”Footnote 11 Wagner would reflect critically on the nature of an ideal German character for decades, of course. In like spirit, Heine ridiculed the political scene (Neue Gedichte, Deutschland: Ein Wintermärchen) but took aim specifically at art music for being blithely disconnected from matters of social concern. While gorging on the “Marseillaise” booming beneath his window, Heine condemns art music as powerless in the face of such rabble-rousing anthems.Footnote 12

That Wagner’s setting of Heine’s “Les deux grenadiers” incorporates the Marseillaise (three months after his arrival in Paris) offers grounds to suspect the composer was both aware of and sympathetic to Heine’s complaint. By 1848, with the authority of public office, his attitude had hardened enough to warrant public criticism; he remodeled Heine’s concern as the subjugation of artists’ creativity in Art and Revolution (1848): “What [has aggrieved] the musician, when he must compose his music for the banquet-table? And what the poet, when he must write romances for the lending library? … That he must squander his creative powers for gain, and make his art a handicraft!”Footnote 13 Other Young Germans were still more assertive in their contempt for the disconnect between instrumental music and bracing social realities. A fuller case is articulated by literary critic Ludolf Wienbarg, for whom the escapism of “refined” art music created a moral solipsism that blots out suffering. Music truly expressive of “silent dissonances within our breast … would drown out the music of the angels and bring forth the shrillest discords from the throne of harmony itself” he explains.Footnote 14 Such sentiments may offer one reason why Wagner remained a self-styled dramatist reluctant to acknowledge his identity as composer, even during the composition of Götterdämmerung.Footnote 15

At the age of twenty-seven, the composer famously reflected on German musical character in a short essay rooted in Ludwig Tieck’s writings. On German Music (1840) placed this character starkly at odds with the spectacle and virtuosity of the Opéra and the cult of celebrity that characterized the principal singers of the Théâtre-Italien. “The German cannot impart his musical transports to the mass, but only to the most familiar circle of his friends,” Wagner tells his French readers. “Music in Germany has spread to the lowest and most unlikely social strata, nay, perhaps here has its root.”Footnote 16 (The attempt to define the terms of the question Was ist Deutsch? runs like a red thread through Wagner’s writings between at least the essays of 1834 and 1878, and both he and Heine would satirize the enterprise by 1840.Footnote 17) Patent exceptions to the low standing of German opera – Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte (1791) and Weber’s Der Freischütz (1821) – merely proved – he felt – that German opera is at home only within the sphere of fairy tale.Footnote 18

Beyond confirming domestic instrumental music as the German vernacular, this 1840 essay laid the ground for an identity problem that would occupy Wagner for decades: “[i]t is not to be denied that the grander genre of dramatic music does not flourish in Germany of itself; and apparently for the same reason that the higher type of German play has never reached its fullest bloom.”Footnote 19 How, a concerned reader might ask, should Germanic theater flourish and be true to itself? In a decade during which Shakespeare was claimed as a native German and Meyerbeer a naturalized Parisian, national identity and affiliation were both flexible and chosen. Whether motivated in the context of aesthetic or nationalist discourses, the German question acknowledges a positional weakness vis-à-vis French and Italian traditions and, guarding against frail teleologies, it is in this context that we may start to investigate Wagner’s identity as a reformer.

Aborted Reforms at Dresden

At the age of thirty-four, Wagner’s impulse to reform German theater first found its public voice. The year was 1847. Twelve months earlier, Wagner had submitted a formal entreaty to reform and reorganize the Dresden Court Theater; he waited over a year for a response. The document, Regarding the Royal Chapel (Die Königliche Kapelle betreffend) sets out a practical case for pensioning off old or inadequate players, appointing new players in key roles, apportioning players between heavier and lighter operas (to avoid fatigue), updating old instruments (timpani, double-pedal harps), redressing discrepancies between the salaries of certain orchestral players, and rearranging the layout of the orchestra the better to enable lines of sight.Footnote 20

During July 1847, August von Lüttichau, Intendant at the Dresden Theater, informed Wagner his proposals had been rejected without further explanation: “I broke definitively with Lüttichau,” Wagner confessed privately.Footnote 21 The moment was pivotal; it was the last time Wagner had the opportunity for advancement within a municipal institution, and, in effect, before embracing the identity of an outsider. After his proposal was dismissed, Wagner went from febrile frustration (in August):

I am so full of utter contempt for everything connected with the theatre as it stands at present that – being unable to do anything about it – I have no more ardent desire than to sever all links with it, and I regard it as a veritable curse that my entire creative urge is directed towards the field of drama, since all I find in the miserable conditions which characterize our theatres today is the most abject scorn for all that I do.Footnote 22

to outright revolt (in November): “There is a dam that must be broken down here, and the means we must use is Revolution … A single sensible decision from the King of Prussia with regard to the opera house, and all would be well again!”Footnote 23

Of course, the fractious character of social reform was long familiar to early nineteenth-century Europeans, and Wagner’s efforts in 1846–7 are far from singular for the period. Wagner came of age during the post-Napoleonic retrenchment of rights, and his radical conclusion – in a string of essays from 1848–9 – linked urges towards artistic reform with those governing the reshaping of social institutions and prevailing middle-class values.

We find this to varying degrees in publications of 1849:

Plan for the Organization of a German National Theater in the Kingdom of Saxony

On Edward Devrient’s History of Acting (not accepted by the AAZ)

The synonymy of political and artistic reforms in Wagner’s mind emerges explicitly in 1849 when he asks his close acquaintance, the Berlin music critic Karl Gaillard, to place “Theater Reform” in a Berlin newspaper, adding: “perhaps [the title] ‘German Reform’ will suffice for present purposes.”Footnote 24 In rhetoric, he effortlessly blended artistic matters with social reformist principles – and their implied violence. The essay Revolution (attributed to Wagner in the Sämtliche Schriften und Dichtungen but published anonymously in the Volkszeitung without surviving holographs, and whose authorship therefore remains unproven) left little doubt as to the radical nature of urges towards artistic reform and their translation into civic engagement: “If we look out across nations and people, we recognize everywhere throughout the whole of Europe the fermenting of a violent movement, whose first vibrations have already seized us, whose full fury already threatens to close in on us.”Footnote 25 The notion that “true Art is revolutionary, because its very existence is opposed to the ruling spirit of the community,” sets Wagner’s brand of mid-century reformism apart from other figures in the history of opera.Footnote 26

Operatic Reform: A Brief History

Histories of opera are of course studded with debate concerning local conventions. And textbooks record several calls – Wagner’s included – to reform the genre by reviving ancient Greek tragedy. Since its inception in the late sixteenth century, the raising of speech-like utterance and dialogue to monody reflects a humanist impulse predicated on the prestige of Greek practice. In 1634, Pietro de’ Bardi (fils) wrote of Vincenzo Galilei “restoring ancient music … to improve modern music,”Footnote 27 while Marco da Gagliano praises Ottavo Rinnucini and Jacopo Corsi for “having repeatedly discoursed on the manner in which the ancients used to represent their tragedies, how they introduced their choruses, whether they employed song, and of what kind, and similar matters.”Footnote 28 For humanists like Galileo, opera itself was less an invention than a revival.

Wagner disagreed. As early as 1851, he complained of “an entirely misconstrued Greek mythology” in which “the whole apparatus of musical drama [aria, dance music, recitative] – unchanged in essence down to our very latest opera – was settled once and for all.”Footnote 29 By 1872, writing with the confidence of Germany’s unification behind him, he reflected on what he saw as the specious reasoning that had concealed a flaw in the genre from the outset:

Italian opera is the singular miscarriage of an academic fad, according to which, if one took a versified dialogue modelled more or less on Seneca, and simply got it psalm-sung as one does with the church-litanies, it was believed one would find oneself on the high road to restoring antique tragedy, provided one also arranged for due interruption by choral chants and ballet-dances.Footnote 30

That Wagner was consistent in this view indicates a hard kernel, a leftover that cannot easily be ascribed to an ideology of 1848–9, neither literary fantasy nor anti-Italian prejudice alone.

To take a second example of operatic reform, in the middle of the eighteenth century attitudes towards antiquity were tempered by appeals to Enlightenment ideals of progress, with Vincenzo Manfredini advocating that “to convince oneself that modern music … is absolutely better than ancient music, it is enough to compare good modern compositions with ancient ones.”Footnote 31 Manfredini’s caution against venerating tradition was aimed at conventions of opera seria. He was writing in the wake of Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice (1762), whose reforms the composer and his librettist – Ranieri de’ Calzabigi – would summarize in the preface to Alceste (1769):

I resolved to divest [Alceste] entirely of all those abuses, introduced to it either by the mistaken vanity of singers or by the too great complaisance of composers, which have so long disfigured Italian opera … I have striven to restrict music to its true office of serving poetry by means of expression and by following the situations of the story, without interrupting the action or stifling it with a useless superfluity of ornaments.Footnote 32

Historically speaking, Wagner’s writings on singers largely amplify rather than add to these principles, though the conventions against which each composer worked were different (and Wagner supplied an entirely new linguistic apparatus). According to Manfredini, Gluck inveighed against such practices as: (i) repeating the words of the first part of an aria four times, and the words of the second only once; (ii) stipulating between two and four cadenzas; (iii) adhering first to formal convention, and only then to dramatic situation; (iv) vocalizing on syllables favorable to the voice before the end of the word in question; (v) making conspicuous display of vocal agility in long drawn-out passages. Wagner, for his part, became irritated by conventions of end-rhyme, iambic meter, melodically unsuitable libretto translations, ad libitum cadenzas, and unmetrical recitative divorced from the natural rhythms of prosody. But such fixations served only to bolster his terminal verdict against the genre of opera, which he felt derived from principles of absolute music (rather than poetry) and hence was “dead at core … no longer an art, but a mere article of fashion.”Footnote 33 Of Gluck’s reforms, he acknowledges only that “the so famous revolution of Gluck, which has come to the ears of many ignoramuses as a complete reversal of the views previously current as to opera’s essence, in truth consisted merely in this: that the musical composer revolted against the willfulness of the singer.”Footnote 34 Despite elevating poetry above music, in other words, Gluck was no dramatist. In a court of law, it would be improper for the prosecution to present the case for the defendant (or vice versa) but, in the absence of standardized narratives for music history, this is effectively what happened during the mid-century. Wagner’s self-serving, potted histories of opera and stage drama – principally parts 1–2 of Opera and Drama – are often dazzling to modern readers in placing him at the apex of historical necessity. No fewer than twenty-seven German-language music periodicals were established between 1848 and 1860, and controversy only increased dissemination as Wagner’s views were widely discussed and propagated – however inaccurately – in the professional press.Footnote 35

However partial Wagner’s summaries may seem to us today, his insistence on the historically unprecedented nature of his music, beginning – he specified – with Tannhäuser (1845), found sympathy among writers of the next generation. Wagner wrote in 1864 to his Swiss confidante, Eliza Wille, of having embarked “upon a course that was as novel as it was fraught with difficulty,” and of how his “unspeakable suffering” from the birth pangs of such artworks bestowed on him “a superior right, an entitlement which … would have raised me far, far above the world and thus … would have made me inwardly a hallowed and blessed human being.”Footnote 36 This kind of attitude repulsed Nietzsche, who deftly inverted it: “one is an actor by virtue of being ahead of the rest of mankind in one insight: what is meant to have the effect of truth must not be true.”Footnote 37 Wagner’s claims for a “human gospel of the art of the future” would be so much self-aggrandizement but for the fact that they entered the water stream of European aesthetics, and – for a time – were readily imbibed. As ever, the discourse is enmeshed within Wagner’s own words and endeavors: the very existence of Bayreuth solidified his aura of uniqueness along with that of the Ring in 1876; it was a singular theater for a singular art – from architecture to atmosphere to acoustics – and hence epitomizes his claims for the historical uniqueness of his “stage festival play.”Footnote 38 Writing with all the wisdom of hindsight, Martin Geck still diagnoses Wagner as the prophet of art sought by his century: “he may not have been uncontroversial, but there is no doubt that he was unrivalled.”Footnote 39 It was a Kantian justification – identifying the natural genius principally by a criterion of originality – but also a powerful historical claim; it made Wagner central and yet radically extraneous to the institution of opera.

In the first part of his poetic obituary, Richard Wagner: Rêvue d’un poëte français (1885), Mallarmé echoes the composer’s sense of his own particularism: “The certainty that neither he himself nor anyone of this time will be involved in any similar enterprise liberates him from any restriction that might be placed on his dream by a sense of incompetence and by the gap between dream and fact.”Footnote 40 Wagner’s peculiarly singular artistic vision shields him from normative judgment, in other words, allowing him at least to lock eyes with the greater heuristic phantasms of art, if not quite slay them. (The Ring, for Mallarmé, remained unresolved and incomplete, its violated law of exchange is unrectified and its incest taboo unrecanted: “Le dieu Richard Wagner”Footnote 41 had scaled but “halfway up the holy mountain” [à mi-côte de la montagne sainte].)Footnote 42

Against such qualified praise, the question arises as to why, historiographically speaking, Wagner’s case, and that of the Ring in particular, has been treated as sui generis, as Wagner asserted it to be. What is it about the Ring – fruit of contested reforms – that led a generation of writers and philosophers to interpret the world through its expressive devices, its symbols, and its narratives? If the practical principles of Wagner’s reforms – from disciplining singers to seeking radically flexible forms and the primacy of drama – largely build on Gluck’s precedent, why did they encounter such a different reception?

The Ring in Literature

There are several routes a response to these questions could take. One would be that Wagner embarked on Der Ring des Nibelungen explicitly as a political revolutionary, that the work resonates long into the night of German modernism because it was conceived from the outset as “an onslaught on the bourgeois-capitalist order,” as John Deathridge put it. George Bernard Shaw had declared the Ring “a first essay in political philosophy” as early as 1901, a view that underscored his allegorical reading of it – in 1898 – as a poetic vision of unregulated industrial capitalism, where the much delayed composition of Götterdämmering almost becomes anachronistic: “an attempt to revive the barricades of Dresden in the Temple of the Grail.”Footnote 43 But there is little reason to attribute Wagner’s literary influence to this political identity, which – for those historical witnesses aware of it – appears incidental to the design of his musico-theatrical program (it goes unmentioned in most literary responses to the Ring: the Wagnerism of Wilde’s Algernon Moncrieff and Huysmans’ Jean des Esseintes has nothing to do with revolutionary politics and everything to do with psychological captivity and sartorial extravagance). Another answer would be that the Ring imputes a certain mythic symbolism to its musical devices, a symbolism that resonated profoundly with turn-of-the-century aesthetics where music is elevated above representational forms of art. Hence, the psychological function of leitmotifs, the musical sound of poetry, and the impulse to draw different artistic media together under the auspices of revivifying Greek theater. Still a third answer might point to Wagner’s reception as a literary persona, whose bold statements, strewn throughout his lengthy published essays, became attractive for a generation of artists regardless of medium. To take one example: “The artist addresses himself to feeling and not to understanding,” Wagner explains near the beginning of A Communication to My Friends (1851) in a statement that would become a mantra. “If he is answered in terms of the understanding, it is as good as saying he has not been understood.”Footnote 44 Walter Pater would influence a generation of writers and painters (“decadents”) by extending much the same argument in 1873, that aesthetic criticism depends on the cultivation of one’s receptivity to beauty as a function of pure sensory pleasure.Footnote 45 “What is important,” he explains, “is not that the critic should possess a correct abstract definition of beauty for the intellect, but a certain kind of temperament, the power of being deeply moved by the presence of beautiful objects.”Footnote 46 Here, it seems, composer and critic interlock cleanly in their aspirations for aesthetic communication.

For Wagner the reformer, silent literature almost always carried negative connotations, as noted above. Drama, he felt, should not be treated as a branch of literature, a defective “literary drama” wherein any musical accompaniment was incidental, akin to the unintegrated media of melodrama.Footnote 47 But if Wagner is to be taken at his word, the narrative and symbols of the Ring cycle came from literature: the Old Norse Sagas and instantiations of the Nibelungenlied. It seems fitting, then, to investigate in turn the Ring’s impact on literature, however diffuse this may be. It is certainly not my intention to provide a synthesis of all that has been written and all that could be written on Wagner’s literary dimensions.Footnote 48 But rather to ask: What about Wagner’s public image and the Ring cycle in particular appealed so potently to turn-of-the-century writers? Previous commentators addressing the topic acknowledge it as theoretically infinite – a vast network of influence, whose tremors are often subtle, occasionally antithetical – and break it down according to discrete national literary traditions.Footnote 49 Here we might note that separate literary journals were founded in France (Revue wagnérienne, 1885–7), England (The Meister, 1888–95), and Italy (Cronaca Wagneriana, 1893–5), in order of consequence. One problem for this approach to literary influence is that where the tremors stop depends on the apparatus of measurement, regardless of intention. Such artificiality becomes particularly evident when such questions are subsumed within the broader remit of Wagner’s role in European modernism (for Mann he was nothing less than “the problem of modernism itself”).Footnote 50 Hence the task becomes to bring the intentionless into the realm of concepts.

Such an ambition is necessarily tapered by the remaining space of this chapter, so I adopt a series of representative case studies rather than attempt a comprehensive overview. To structure this closing discussion, I focus on three categories vis-à-vis the Ring: (i) mythic themes, (ii) leitmotifs, (iii) the sounding surface of musical words, to probe the role Wagner’s harmony, Versmelodie, and alliterative poetry had for European writers.

Mythic Reference, Mythic Parody

Alongside coded allusions to Wagner’s works (Adrian Leverkühn’s letter to Kretschmar gives a verbal description of the Prelude to act 3 of Die Meistersinger in Doctor Faustus, without naming it)Footnote 51 are explicitly intertextual references to the Ring pitched ambiguously between parody and homage. D. H. Lawrence’s novel The Trespasser (1912) was originally entitled The Saga of Siegmund. Some parallels are glaring: a sheepdog bays, like Wagner’s giants; the sound of the train mimics the “Ride of the Valkyries” (Raymond Furness found these “forced and unsubtle”).Footnote 52 More intriguing is the mythic realism that sees Wagnerian characters citing Wagner’s actual works, as though in an alternative reality: at Tintagel, Helena

found that the cave was exactly, almost identically, the same as the Walhalla scene in Walküre; in the second place, Tristan was here, in the tragic country filled with the flowers of a late Cornish summer, an everlasting reality … Helena forever hummed fragments of Tristan. As she stood on the rocks she sang, in her little half-articulate way, bits of Isolde’s love, bits of Tristan’s anguish, to Siegmund.Footnote 53

In the same vein, Mann’s insight for his early novella, The Blood of the Walsungs (1906), was to transplant the social shock and latent tension of Wagner’s (positive) depiction of incest vis-à-vis Hunding to that between assimilated Jews (the Aarenhold family) and a German outsider (Herr von Beckerath). Sieglinde and Siegmund are turn-of-the-century Jewish “twins, graceful as young fawns,” practicing incest, while Sieglinde is engaged to a German government official, sixteen years her senior. His visit to the Aarenhold house, and the psychological development of the opera they witness together, constitute the action of the novella. Along with allusion to the plot of Die Walküre, its musical barbs shred the otherwise seamless poetic realism: Siegmund asks von Beckerath if he and Sieglinde may hear Die Walküre “once more together – may we? We are of course aware that everything depends upon your gracious favour,” and this question is followed by Sieglinde’s other brother, Kunz, tapping Hunding’s motif on the tablecloth – mocking both the leitmotif technique and the pretense that von Beckerath (or any reader) is ignorant of what is going on.

Parody without homage formed a prominent literary strand in its own right, of course. We are perhaps most familiar with pictorial caricatures of Wagner. Less immediately graspable, but no less lancing, were the numerous literary riffs on Wagner’s narratives.Footnote 54 Aubrey Beardsley, for one, planned to write a “Comedy of the Rheingold” in the same spirit as his illustrated novel Venus and Tannhäuser – variously called “a romantic novel” and “a fairy tale” – but aside from its cover illustration, this never materialized (see Figure 12.2). In other writing, Beardsley’s nested criticism of the Ring is plain. Take the example of Under the Hill (1907), where Tannhäuser lies in bed reading a score of Das Rheingold:

Tannhäuser had taken some books to bed with him. One was the witty, extravagant “Tuesday and Josephine,” another was the score of “The Rheingold.” Making a pulpit of his knees, he propped up the opera before him and turned over the pages with a loving hand, and found it delicious to attack Wagner’s brilliant comedy with the cool head of the morning. Once more he was ravished with the beauty and wit of the opening scene … But it was the third tableau that he applauded most that morning, the scene where Loge, like some flamboyant primeval Scapin, practices his cunning upon Alberich. The feverish insistent ringing of the hammers at the forge, the dry staccato restlessness of Mime, the ceaseless coming and going of the troupe of Nibelungs, drawn hither and thither like a flock of terror-stricken and infernal sheep, Alberich’s savage activity and metamorphoses, and Loge’s rapid, flaming tonguelike movements, made the tableau the least reposeful, most troubled and confusing thing in the whole range of opera. How the Chevalier rejoiced in the extravagant monstrous poetry; the heated melodrama, and splendid agitation of it all!Footnote 55

Here the insights of criticism (not unlike those of G. B. Shaw) merge with ironic inversions (a reposing knight reading the “least reposeful” opera; the knees not as vehicle of deference but as “pulpit” from which to attack Wagner’s score) and parodic readings of Rheingold in terms of alien genres (a “brilliant comedy” or “melodrama” replete with flamboyance, extravagance, wit), all under the protective guise of fiction. The author’s voice functions at multiple levels: The parody is stylistically true, while the moments of genuine music criticism – where accurate – can only be read as equally sincere.

Figure 12.2 Aubrey Beardsley frontispiece to his projected “Comedy of the Rhinegold,” The Savoy 8 (December 1896), 43–4

The lofty claims of myth frequently lend themselves to satire, and, perhaps for this reason, more traditional parody of the Ring cycle has had a long shelf life. As early as 1877, Pniower Gisbert’s The Ring that Never Worked sent up much of the action from the previous year, from alliterative “female Rhein guards” (Wir Wiener Wäscherinnen waschen weiße Wäsche / Die Katze tritt die Treppe krumm.) to the god “Wodann?” (literally: “Where then?”) whose very name asks how he is supposed to attain Götterdämmerung.Footnote 56 A century on, Anthony Burgess’ novel Worm and the Ring (1961) resituates the cast in an English grammar school: Wooltan (the school principal), his wife Frederica, Lodge (cf. Loge), Linda (cf. Woglinde), and one Albert Rich who is in pursuit of three giggling schoolgirls, make up the cast: “Albert Rich and his rain reflection sloshed through the puddles after the three giggling fourth-form girls. By God, he would have one of them, which one didn’t matter … The three maidens laughed in peal after peal, a shrill song of provocative triads as they bounded with girlish grace through the water.”Footnote 57 Beyond the fading satisfaction of intertextual recognition, Burgess’ comic allusion carries comparators, e.g., casting Rich’s pedophilic desire as a Wagnerian malady akin to incest, as provocative in 1961 as it was in 1870/76.

After parody lies the soberness of veiled critique. The protagonist in Émile Zola’s novel L’Oeuvre (1886), Claude Lantier, is a misunderstood, revolutionary artist (painter) who fruitlessly adores Wagner and fails to live up to his potential, descending into madness while attempting a huge landscape painting before finally hanging himself. Beyond camouflaging his own friendship with Paul Cézanne and his imbrication with the Wagnerism of the 1880s, Zola obliquely highlights the loss of landscape painting from Wagner’s touted society of artists in The Artwork of the Future (1849). Neither the richness of the Vienna Secessionist’s response to Wagner nor the flourishing industry of Ring-inspired imagery could reinstate the rejected role of landscape painter.

Leitmotif

Historically speaking, literary responses to Wagner’s music begin with the man he once saluted as “my second self.”Footnote 58 Liszt’s extended, propagandistic essays on Tannhäuser and Lohengrin (1850–2) were the longest written responses to Wagner’s music to date, dwarfing French reviews of Wagner productions in Germany (by Théophile Gautier and Gérard de Nerval among others).Footnote 59 One need but hear the overture to Tannhäuser in order to discern in its principal motifs the opera’s medieval agon between faith and flesh, Liszt asserted: “not once is it necessary to know the words which are adapted to [the motifs] afterwards.”Footnote 60 This claim to eschew text and context in favor of pure sound effectively threw down a gauntlet for later writers. To be sure, French literary Wagnerism officially begins around 1860–1 with Baudelaire’s essay Richard Wagner and Tannhäuser in Paris (1861), modeled in part on Liszt’s reading of synesthetic imagery into Wagner’s sonorities. That this was coeval with the symbolist movement is no coincidence. Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal (1857) inaugurated a movement conceived in opposition to realism (cf. Balzac, Flaubert, Zola), whose central purpose was to unleash the far-flung intuitions of the imagination; describing this “delicate delirium” which writers wished to present often required the language of synesthesia, becoming a task for which music – the least referential art – was best suited.Footnote 61 Baudelaire’s “Correspondences” speaks of “perplexing messages; / forests of symbols between us and the shrine.”Footnote 62 In charting correspondences between sounds, scents, and colors, it could be taken as a manifesto for symbolism as offspring of leitmotifs:

The Ring is the earliest work Wagner composed explicitly as a fabric of corresponding mnemonic-thematic associations that carry listeners’ feeling and mold perspective. In his oft-cited 1844 letter to Gaillard, moreover, he explained his own working practice of being “immersed in the musical aura of my new creation,” even before drafting a word of a prose scenario, continuing, “I have the whole sound and all the characteristic motifs in my head so that when the poem is finished … the actual opera, for me, is finished.”Footnote 64 Whether or not we accept this, it rings true for the aspirations of later poets.

Scathing reactions to Wagner’s practice are less familiar than the proliferation of his thematic Leitfaden (Wolzogen’s term) or “melodic moments” (Wagner’s term) as signposts to direct listeners’ feeling through the labyrinthine corridors of a drama. On different occasions Hanslick dubbed leitmotifs tourist guides, quipping that the operas’ heroes are all furnished (via the orchestra) with a “rich musical wardrobe”;Footnote 65 for Nietzsche, they held the ironic status of the ideal toothpick,Footnote 66 while Stravinsky spoke of “cloakroom numbers,”Footnote 67 George Bernard Shaw of “calling cards,” and Debussy of an absurd “address book.” It has been easy to impugn the principle of musical signs (such mockery only attests the pervasive presence of Wagner), yet the technique is central to Wagner’s notion of an unfolding drama that can be understood intuitively, without verbal commentary (Wagner’s terms for this are Gefühlsverstehen / gefühlsverständlich). His cultural ownership of the leitmotif is a mixed blessing, though, and in some cases contributes to dubious generalizations: It encourages simplistic assessment of what is a protean, inconstant technique of audio-visual signs, and it ascribes a semiotic process wholly to Wagner that other composers and genres already employed in part if not systematically. Witness melodrama’s unsubtle use of musical signs to mark a particular character’s entrance, to underscore heightened tensions, or to signal a change in situation.Footnote 68

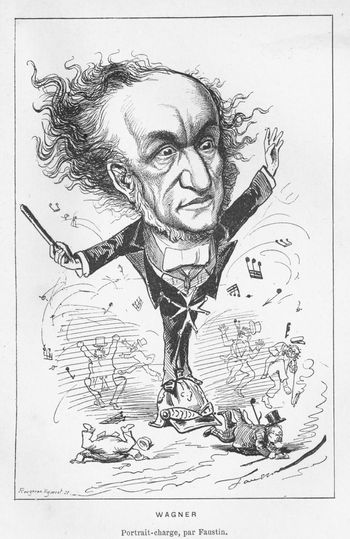

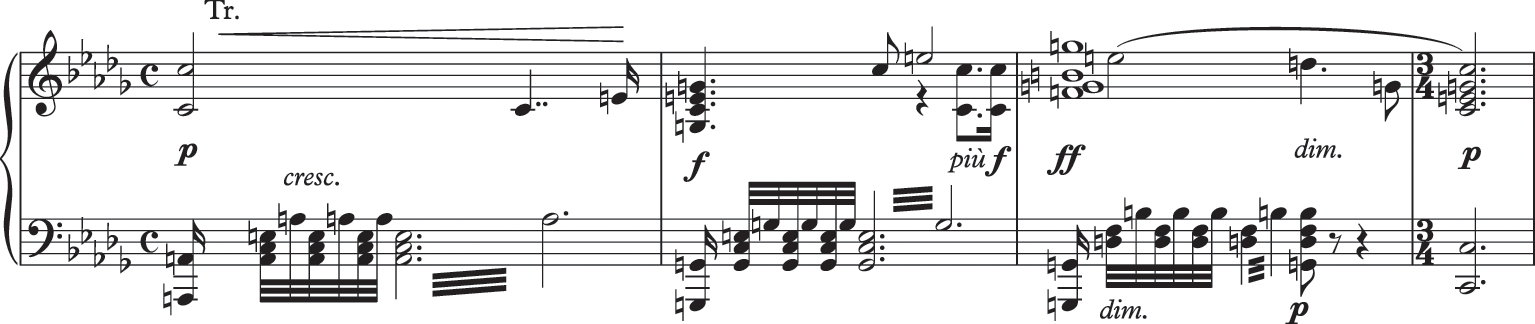

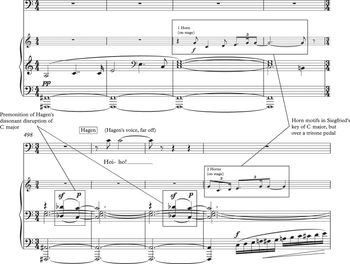

An instance where nothing more than a key delivers a leitmotivic function can be instructive, given the unchanging nature of its pitch and hence its proximity to the use of fixed images or a recurring phrase. The trumpet’s C major dotted arpeggio is one example of a sound assigned an associative value mnemonically. When it recurs later in the narrative, it has with the effect of adding interpretive layers to our reading, both of the past and present. As Example 12.1a shows, this is initially linked to Wotan’s mission in Das Rheingold (just before he ascends the rainbow bridge to Valhalla, bb. 3780–7, 3876–80) and to Wälse’s sword, Notung, in Die Walküre (when Siegmund draws the sword from the World Ash Tree, act 1 scene 3, bb. 848–50). It transfers to Siegfried – as Wotan’s now unsanctioned agent – where the key, first played by the trumpet, and later heard in radiant brass and harps for the sunrise on his awakening of Brünnhilde, carries his strength, all the while conceived as part of his (unsanctioned) mission. This association of strength, coupled to his relation to Brünnhilde, is fatally undermined for listeners in Götterdämmerung when Siegfried, unaware of the threat from Hagen, is undone (Examples 12.1b–c), perhaps by naïveté now seen as the flipside to his strength-giving fearlessness: Following the curse motif heard pianissimo on a single trombone, two C major snippets from his triadic horn call – ordinarily in F – are undercut by a tritone pedal (F♯; act 3 scene 2, bb. 494–501) and, in premonition of Hagen’s call “Hoi-ho” after Siegfried’s murder, the jarring semitone (D♭–C, cf. act 3 scene 3, bb. 1033–42) is overlaid in octaves, all against the lower tritone pedal. The C major pitches are identical but clouded in dissonance: What sounded so vibrant and powerful now signals vulnerability, weakness, and death – not just of Siegfried, also of his ostensive mission.

Example 12.1a Premonition of the sword motif, emblematic of Wotan’s mission, Das Rheingold

Example 12.1b Premonition of Siegfried’s downfall, Götterdämmerung, act 3 scene 2

Example 12.1c The underlying harmonic corruption of Siegfried’s C major

It is worth clarifying, then, what it means when authors like Furness say, that the harmonic and timbral transformations of these carriers of feelings “exerted such an overwhelming influence on literature because psychological cross-references and associations, and interrelationships between clusters of images and symbols, could be established, the impact being enormously increased thereby.”Footnote 69 This reminds us that motifs – sensory carriers of associative meaning – are as protean and potentially combinatorial as the expansive harmonic and contrapuntal vocabulary of the period allows, i.e. considerably freer than grammatical syntax. Critically useful for literature was the fact that, like spoken intonation, at least two layers of meaning are collapsed into one sound signal: sound conveying an activity, person, event, object, etc.; sound commenting on or expressing the emotional value of that activity etc. In such elisions, the difference between word and music, sign and sensation recede into an infinite regress between memory and meaning.

Sound of Language

While Pater’s adage that all arts aspire to the condition of music is usually taken to refer to music’s freedom from referentially and the fetters of meaning, Paul Valéry valued Wagner’s music for its “pure sound,” viewing the entire symbolist movement as an attempt to reclaim from music what originally belonged to poetry itself.Footnote 70 Mallarmé sharpened Valéry’s position, seeking to recuperate specifically from Wagner’s music what he felt had once belonged to poetry alone. He sought, in other words, to roll back Wagner’s increase of “music’s language-capacity into the immeasurable,” in Nietzsche’s words, while retaining the potential for multimodal communication through verbal sounds.Footnote 71

Contemporary commentators such as Joachim Raff were skeptical of Wagner’s alliterative poetry in the Ring, but Gottfried Keller recommended the 1853 printing of Wagner’s poem, explaining to Hermann Hettner, “you will find a powerful, typically Germanic poetry here, but one which is ennobled by a sense of antique tragedy.”Footnote 72 And while many subsequent musicologists have scoffed at Wagner’s claims for language’s ancient communicative potency, the twentieth century has been particularly receptive to composers seeking to “increase music’s capacity for language.” Influential commentaries by Ferdinand de Saussure (linguistics) and Ludwig Wittgenstein (philosophy of language) tended to sever the word from any reference it had in an external, physical world. Just as language thereby became a system of signs, entirely derefentialized and self-enclosed, where signs point to other signs rather than to real, tangible objects, so speech becomes ever more like music.

Ironically, Wagner was moving in the opposite direction with the Ring poem, seeking a language whose phonemes were ever more firmly referentialized, resulting in an ever-greater hedging-in of meaning through sound, even as symbolists cultivated sound as a means of loosening syntactical fixity. If the direction of travel is different, the road is the same. “Understanding a sentence is much more akin to understanding a theme in music than one may think,” Wittgenstein mused in 1953.Footnote 73 He explains this elsewhere by noting how the progression from dereferentialized verbal sounds to music is really only possible upon realizing that “reality” depends on conventions of verbal signs:

to say a word has meaning does not imply that it stands for or represents a thing … The sign plus the rules of grammar applying to it is all we need [to make a language]. We need nothing further to make the connection with reality. If we did we should need something to connect with that reality, which would lead to an infinite regress.Footnote 74

Wagner’s Ring is not responsible for this move in structural linguistics, but his sonically captivating treatment of language as a totality of phonetic elements and his practice of motivic signification arguably opened the door.

In James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (1939), we find alliterative references to Das Rheingold, whose musical effect ripples on the brink of syntactical sense, relishing the patterns of pure vocal sound:

Alongside the steady evolution of phonemic patterns – not unlike the children’s game of “telephone” – the unmistakable cadence evokes Woglinde’s opening phonemes, which constitute equally referential sounds on the brink of nonsense, particularly when unsung.

The Swedish playwright August Strindberg alludes to the German verbs in this passage rather more literally in A Dream Play (1907), a work – he explains – modeled on associative patterns formed during dreaming. Here is the waves’ gentle singing interlude, in conspicuously alliterative translation: “We, we are the waves – which rock the winds in their cradle to rest – we, we are the winds – which wail and moan – woe – woe – woe … ”Footnote 75 In his richly allusive poem The Waste Land, T. S. Eliot too points to traditions of Wagnerian alliteration (“Summer surprised us, coming over the Starnbergersee” [where King Ludwig II drowned]) and audio-aquatic imagery from the Prelude to Das Rheingold (“If there were the sound of water only”). Beyond the oft-cited Tristan quotations (“Frisch weht der Wind … ” / “Oed’ und leer das Meer”), Eliot’s chain of Wagnerian references testifies to the prevalence of Wagnerism as obsession and malady in British literary discourse. Amid densely nested intertextuality, we find Erda by another name (“Madame Sosostris, famous clairvoyante / … Is known to be the wisest woman in Europe, / With a wicked pack of cards”), along with the Rhinemaidens – Flosshilde, Woglinde, Wellgunde – transmogrified in rhyme and cleanliness as the three “Thames” daughters – Richmond, Moorgate, Margate – where they quote their cousins in Götterdämmerung, as though dispelling all doubt of kinship: “Weialala leia / Wallala leialala.” Indeed, the whole profile of apocalypse, fire, water, and redemptive love resonates with Götterdämmerung, and the temptation of mining Eliot’s text for Ring references has led some to regard Wagner as the preeminent influence on The Waste Land.Footnote 76 But Eliot’s allusions borrow to reflect the age. Stoddard Martin is persuasive in suggesting that such allusion reflects less Eliot’s own mixed affiliation to Wagner, more “the Wagnerism of those artists who people his mind as he wrote.”Footnote 77 This is not to deny Eliot’s early infatuation. His unpublished poem “Opera” (1909) revels in Tristan’s paroxysms, a music “Flinging itself at the last / Limits of self-expression.”Footnote 78 But by the end this leaves him feeling strangely disconnected: “like the ghost of youth / At the undertakers’ ball.”Footnote 79 Whether because of enervation or alienation, Eliot’s motivic allusions critique the cumbersomeness of Gesamtkunstwerk, while capturing the interior soundscape of European cultural thought, suffused as it was with Wagnerian reference.

But motifs are also carriers of memory and hence of time. Marcel Proust’s extended novel A la recherche du temps perdu (1913–27) is a touchstone for a literary technique of leitmotif that conveys how involuntary memory functions by subconscious association, the belief that we only recall the past when we stumble across a sensation: a taste of madeleine cake and lime-blossom tea (recalling Sunday mornings in Combray with Aunt Léonie), the scent and texture of an old glove (recalling the love for us by those who are gone), a sound of an old piano (recalling your grandfather).Footnote 80 Boulez would make an explicit connection to Wagner’s temporality here, and it is surely no coincidence that later French authors such as Henri Bergson, Edmund Husserl, and Jean-Paul Sartre all likened the consciousness of one’s temporal existence to “melody.”Footnote 81 The association between musical flow and interior perception has a complex history, to be sure. For present purposes, though originally a simile introduced by Schopenhauer, melody’s link to the perception of consciousness arguably finds its characteristic formulation in Wagner’s description of infinite melody (unendliche Melodie), given in his preface to a French translation of the librettos of his romantic operas.Footnote 82 Ventriloquizing a dialogue between a (male) poet and (female) musician, Wagner imagines the former imploring the latter:

throw yourself boldly into the sea of music; with my hand in yours you can never lose contact with what all men find most comprehensible. For, through me, you remain in constant contact with the firm ground of a dramatic action, and the scenic representation of this action is the most immediately comprehensible poem of all. Unharness your melody boldly, so that it gushes through the whole work like an uninterrupted stream; in it you will be voicing what I leave unsaid, for only you can say it; while I will still be saying it all silently, since it is your hand I am guiding.Footnote 83

In the Ring cycle this double narrative – poetic word and instrumental music – is spun into a polyphonic web that includes characters’ words, their singing voices, orchestral sonorities, and their thematic signs, though the potential narrative multiplications go much further.

The French poet Édouard Dujardin, founder and editor of Revue wagnerienne, came close to this poetic-musical compound for a purely verbal sort of drama in his description of monologue intérieur, a literary technique first used in his novel Les Lauriers sont coupés (1887). Like an “uninterrupted [musical] stream” giving voice to what syntactical words cannot, an interior monologue offers: “the most intimate thought, closest to the unconscious,” Dujardin explains. “[I]n concept, it is speech before any logical organization, reproducing this thought as it comes into being and in its apparently raw state; in its form, it is realized through sentences in direct speech reduced to a syntactic minimum.”Footnote 84 As is well known, this literary technique is the model Joyce acknowledged for his steam of consciousness in Ulysses (1922). Not enough has been made of the links between Joyce’s technique and Wagner’s concept of an “uninterrupted stream” of melody that ensounds unvoiced thoughts. Dujardin appears not to have understood Wagner’s leitmotifs comprehensively (he suggested they never develop),Footnote 85 but as Stephen Huebner has argued, the language of Les Lauriers reveals a twofold trend: “an ambition to create a seamless … open-ended unfolding of new impressions and an inclination to lyrical repetition and order.”Footnote 86 In the shadow of Wagner, both relate to literary investigations of interiority and putatively subliminal processing, both entrain aesthetic techniques to mimic lived experience and vice versa.

Motifs as Psychological Reference

Proust himself invokes Wagner for the cognitive realism he sees embedded in recurring musical reference:

I was struck by how much reality there is in the work of Wagner as I contemplated once more those insistent, fleeting themes which visit an act, recede only to return again and again, and, sometimes distant, drowsy, almost detached, are at other moments, while remaining vague, so pressing and so close, so internal, so organic, so visceral, that they seem like the reprise not so much of a musical motif, as of an attack of neuralgia.Footnote 87

Here musical allusion becomes the guarantor of individuality, no less, evoking interior responses to exterior objects. Proust’s are needle-point specific: “Even that which, in this music, is most independent of the emotion that it arouses in us preserves its outward and absolutely precise reality; the song of a bird, the ring of a hunter’s horn, the air that a shepherd plays upon his pipe, each carves its silhouette of a sound against the horizon.”Footnote 88 This roll call of Wagner’s motifs – the Woodbird in Siegfried, Siegfried’s horn call, the Shepherd’s lament in Tristan – contrasts with the nondiegetic thematic references of, say, an instrumental sonata, though the psychological effort each solicits from listeners are akin as signs within what Proust calls music’s “liquidity.” Witness his description of Swann listening to fleeting thematic references in the absence of verbal language. Here, in a final quote from Proust, the concept of understanding is moot as memory intervenes in the cognitive wash of a sonata:

The motifs which from time to time emerge, barely discernible, to plunge again and disappear and drown, recognised only but the particular kind of pleasure which they instil, impossible to describe, to recollect, to name, ineffable … [S]carcely had the exquisite sensation … died away, before his memory had furnished him with an immediate transcript, sketchy, it is true, and provisional, which he had been able to glance at while the piece continued, so that, when the same impression suddenly returned, it was no longer impossible to grasp.Footnote 89

This kind of emerging cartography of our emotions was attractive for writers probing the psychological interiority of subjects. It established a mnemonic framework as central to organizing aesthetic experience. And the cognitive task of relating one’s experience of Wagner to meaningful interpretation of his operas is laid bare at once as literary technique, fictional description, and music criticism.

Perhaps this helps explain why Mann’s novels glisten with leitmotifs. “I have imitated Wagner a great deal,” Mann confessed to Adorno in 1952.Footnote 90 Beyond Proust’s involuntariness, leitmotifs can point to unconscious thoughts or processes as a narrative technique, where the absence of narrative comment on their recurrence leaves the reader to assign significance. Witness the song Hans Carstorp sings on the battlefield (“Der Lindenbaum”), which recuperates the experience he had when listening to same song on the gramophone at the Berghof, as well as the tree’s broader cultural resonance within German mythology; or the recurring x-rays; or Asiatic eyes (The Magic Mountain); or the varying state (and colors) of characters’ teeth that signals their mental as well as physical health; or the prominent blue veins on Thomas Buddenbrook’s “narrow temple”; or the “finely articulated” Buddenbrook hands (Buddenbrooks). Such tiny signs draw on a symbolist tendency towards gestures of meaning, while simultaneously serving the purpose of realist description. Mann wrote openly about his musical understanding of the technique:

Musical composition – I have already mentioned in connection with earlier works that the novel has always been for me a symphony, a work of counterpoint – a thematic fabric in which ideas play the part of musical motifs. This technique is applied to The Magic Mountain in the most complex and all-pervasive way. On that account you have my presumptuous suggestion to read it twice. Only then can one penetrate the associational musical complex of ideas. When the reader knows his thematic material, then he is in a position to interpret the symbolic and allusive formulae both forwards and backwards.Footnote 91

This is why readers gain a “heightened and deepened pleasure” from a second and third reading, of course, “just as one must be acquainted with a piece of music to enjoy it properly.” Such a bold confession of intent leaves no room for doubt about the extent of Wagner’s role in shaping Mann’s literary aspirations. Regardless of certain irreducible differences between musical and verbal signs, it provides a new context for substantiating Jean-Jacques Nattiez’s belief that music provides a “redemptive model” for literature.Footnote 92

At a certain level of theoretical abstraction, this notion has been applied even to figures as ostensibly hostile to the Gesamtkunstwerk as Bertholt Brecht. Hilda Brown reads the use of “imagery or image-networks” that have a strategic function in his plays as a principle of recurrence that constitutes kinship with Wagner’s leitmotifs. Both men sought a deliberately radical break with the past, yet their dialectical relation has arguably been distorted by an overemphasis on Brecht’s rejection of Wagnerian phantasmagoria as a narcotic of yesteryear.Footnote 93 Unlike Proust, who saw sensory motifs as routes to unconscious associationism, Brown sees Brecht’s image networks, and their shifting contexts, as a means of creating reflective distance: Witness the telescope, the apple, the milk in Leben des Galileo (1943).Footnote 94 The ostensive dialectic between Wagner and Brecht weakens further upon consideration of certain famous passages of epic narrative and monologue within the Ring, moments of reflective distance from the drama, leading other commentators to go further in venturing that modern theater itself, whose standard-bearer is epic theater—“may be the illegitimate child of opera.”Footnote 95

Closing Thoughts

The second half of this discussion indicates that literary responses to the Ring cycle have almost nothing to do with Wagner’s self-image as a reformer of art institutions. While it is clear Wagner’s sense of his own destiny is a prerequisite for the shaping of the Ring as compositional praxis, it is the tetralogy’s characters, narrative techniques, and structuring principles that provided literary hooks for later writers in the first instance. The impulse to respond goes to the heart of Wagner’s modernist outlook, for along with the cultural phenomenon of Wagnerism that engulfed Eliot, Joyce, Fontane, Mann, Proust, et al., the musicking of poetic language helped destabilize the image of language as a referential link to reality. Auditory signs functioned as such not only by referring to other signs in an infinite chain but by conveying a quality of sensory experience in their very signing. Adapting Nietzsche, we might say Wagner heightened the sensory potential of language immeasurably. It is perhaps for this reason that Ernst Krenek reclassified Wagner’s operatic reforms in 1936 simply in terms of extending sensory pleasure:

Wagner, the argument runs, is not prized and admired for the new quality of his total art-work, as he intended, for the way the music heightens and underlies the significance of his dramatic conceptions; he is valued because, despite all these speculative achievements, the public has learnt to track down the purely operatic side of his work, the side that appeals to the sensual instincts; moreover all his intellectual apparatus only had the result of extending the pleasure-potentialities in the sphere of opera.Footnote 96

For his part, Wagner complained to Cosima in 1880 that the achievements of the first scene of Das Rheingold “were not properly appreciated” in 1876.Footnote 97 This scene epitomizes the sensuous sonification of language predicated on the coupled sounds of alliteration and proved one of the passages most immediately amenable to subsequent writers and poets. While we cannot know what Wagner had in mind, it is tempting to interpret Krenek’s insight about pleasure potentiality as inflating to daunting dimensions opera’s sensory means of communication. With the first words of Rheingold, in such a reading, Wagner effectively recast what it meant for a word to mean. It was a flash of experience undreamt of by those ordinarily occupied with the estranging enigmas of thought alone. Two years after his complaint, Cosima – again thinking of Rheingold – recalls that Wagner: “agrees with me when I say that music can make an impression in the memory as great as when one is actually hearing it.”Footnote 98 By inwardly mediating sense and sign, the literary technique of motivic recall in Proust and Mann (to name but two) would substantiate that passing thought for literary endeavor for decades to come.