Introduction

In most African countries with electoral politics, a gap exists in the rates at which men and women vote, express partisanship, contact officials, attend community meetings, and raise issues (Coffe & Bolzendahl Reference Coffe and Bolzendahl2011). However, the size of the gender gap varies greatly from country to country, and women sometimes participate at higher rates than men (Isaksson et al. Reference Isaksson, Kotsdam and Nerman2014). While the origin of the gender gap is complex and contextually specific, one previously identified correlate is colonial history. Statistically, women in former French colonies participate at lower rates relative to men than women in former British colonies (Hern Reference Hern2018). Aili Marie Tripp notes that this trend dates back to anti-colonial and nationalist movements, where women in soon-to-be-former British colonies were more active than women elsewhere (Reference Tripp2009:34). This study focuses on how varied colonial experiences may have shaped women’s relationships to newly independent states. While the implication is that the legacies of these colonial experiences persist over time, this study examines how colonial policies from the 1920s to the 1950s shaped women’s opportunities for resisting colonial governance, participating in nationalist activity, and becoming involved in early-independence politics.

Without discounting the importance of other types of colonial policy, this article focuses specifically on the gendered differences in the British and French approaches to education in a comparative case analysis of the Gold Coast and Senegal. While many studies examine the influence of colonialism on women’s status in society, most investigate how colonialism writ large eroded women’s public and private power (see Zambakari Reference Zambakari2019 for a review of major works). However, the degree and nature of this disempowerment varies, and this study argues that key differences between the British and French systems—particularly with regard to education—shaped women’s prospects differently. The ample scholarship on girls’ education in the colonies has often focused on lack of access and the limits of a curriculum that focused on domesticity (see Mianda Reference Mianda, Allman, Geiger and Musisi2002). Yet, the rates of access and form of curriculum varied; in British colonies, more girls had access to education and the curriculum was less single-mindedly focused on producing homemakers. I argue that the British approach to education allowed more women to be fully engaged in the public sphere, which resulted in more women being mobilized into various roles in party politics and nationalist movements. The French system not only generated a smaller number of educated women, but also limited girls to a much more restrictive curriculum that emphasized their roles in the private rather than the public sphere. As a result, women in these contexts were less likely to be mobilized as political agents during the independence era, instead acting behind the scenes in supporting roles.

I examine the relative impact of the British and French educational systems through a comparison of the Gold Coast and Senegal. Both were economically important colonies in which the colonial administrations had a lengthy, strong presence. In Senegal, Dakar was the administrative center of the more vast French West Africa (Afrique Occidentale Française, or AOF), and the British had a long and robust presence in the Gold Coast as a result of the historical slave trading outpost at Elmina and the colony’s subsequent economic importance. French and British respective colonial policies were more consistently implemented in these regions than in those regarded as colonial backwaters. This consistency thus allows a more systematic comparison between the two colonial educational polices than would be possible in poorer, less central colonies. Of course, colonial institutions are not the only difference between Ghana and Senegal, or between former British and French colonies in Africa more generally. Because British and French colonies tended to be geographically clustered, it is essential to consider the impact of other variables, such as regional or cultural differences. I address this challenge in part by restricting my focus to two countries in West Africa, but also consider alternative explanations: the role of Islam in Senegal, the clout of Ghana’s market women, and the impact of matrilineality. None of these, however, detracts from the role of education in shaping women’s relationship to the political sphere.

The argument presented here draws largely on primary source documents from three archival collections: the British National Archives (BNA), the Ghanaian Public Records and Archives Administration Department (PRAAD), and the Archives Nationales du Sénégal (ANS).Footnote 1 The majority of these documents come directly from the colonial administrations. While of course one would expect a gap between official reports and on-the-ground reality, systematic comparison of the two regimes reveals important differences in the underlying ideals and rationale of colonial policy that formed curricular principles for girls’ education in the respective colonies. Additionally, these archives include correspondence that allows a more candid appraisal of policy implementation. I complement (and corroborate) analysis of these primary sources with secondary research, from which most of the accounts of women’s various forms of political participation are drawn.

To make this argument, I first provide a theory of how education might enable specific forms of women’s participation in late colonial West Africa. I then turn to an analysis of girls’ education in the Gold Coast and Senegal, demonstrating variation along three key dimensions: quantity, source, and curriculum. The analysis then addresses the independence movements in Ghana and Senegal, examining how women were mobilized (or not) in each context, and demonstrating how women featured more centrally in Ghana’s nationalist politics than in Senegal’s. Next, I consider alternative explanations for these different patterns of participation. The study concludes by considering how these different starting points for women’s participation created lasting variation, noting the extent to which the policies in Ghana and Senegal reflected colonial policy elsewhere, and outlining avenues for future research.

Education, Gender, and Political Behavior during Late Colonialism

In late colonial Africa, access to education (provided by the colonial administration or its affiliates) was an important shibboleth for participating in formal politics. In both French and British colonies, the Africans who designed the new independent governments were disproportionately products of the colonial education (Chafer Reference Chafer2002; Pool Reference Pool2009; Diouf Reference Diouf and Diouf2013). This experience directly shaped the emergent political class (Morgenthau Reference Morgenthau1964; Wallerstein Reference Wallerstein1964). Uneven access to education contributed to class stratification and influenced early political conflicts around independence, particularly between highly educated urbanites with expectations of white-collar careers and less- or un-educated rural dwellers engaged in small-scale agriculture (Cooper Reference Cooper1996; Bob-Milliar Reference Bob-Milliar2014). In most cases (though not exclusively), party formation and nationalist activity originated in the educated urban populations. The political landscape was strikingly different in colonies where bloody revolt or civil war preceded independence, but in colonies with a negotiated transition, the educated urban class had a distinct advantage in gaining access to political power, especially those who had worked within the colonial administration. Kate Skinner notes that teachers were especially over-represented in nationalist movements and political parties across Africa, because teachers and the literate class “played a key role…in deciphering the demands of the colonial state” (Reference Skinner2015:47).

Men dominated the formal independence negotiations, but the rate and the form of women’s involvement in nationalist politics varied from country to country. Women were sometimes armed revolutionaries, as in Algeria, Morocco, and Libya (Tripp Reference Tripp2009:37). Elsewhere, they were integral players in the nationalist-movements-turned-political-parties, as in Zambia’s UNIP (Geisler Reference Geisler2004) and Tanzania’s TANU (Geiger Reference Geiger1987). Often, they quietly adopted subversive roles in support of independence movements, providing food, shelter, and care for male political agents (Cooper Reference Cooper1996). Women worked as grassroots organizers for nascent political parties, as in Cameroon (Terretta Reference Terretta2013) and Guinea (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2005), and were occasionally able to secure positions in the newly independent governments, as in Ghana (Manuh Reference Manuh, Konandu and Campbell2016). While it was not the only important factor, access to education shaped women’s prospects for various forms of political action.

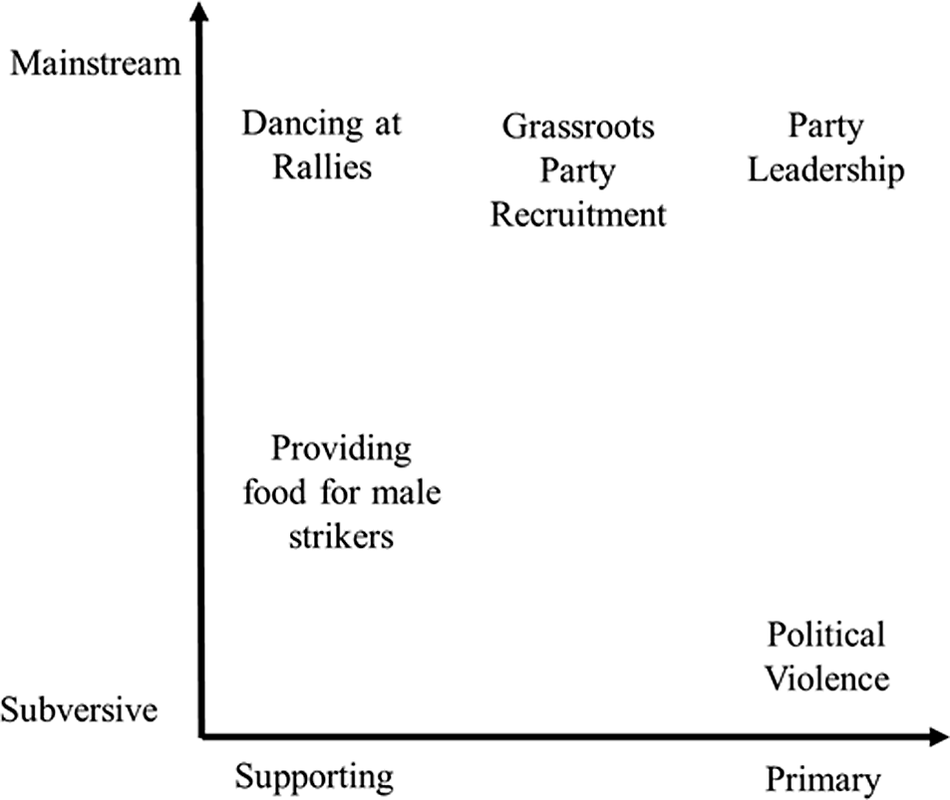

For the purposes of this study, I conceptualize women’s political activity along two dimensions, each constituting a spectrum: whether the activity was subversive or mainstream, and whether women played a primary or supporting role. Subversion includes actions intended to actively undermine a colonial regime (or other government) not carried out through formal channels, while mainstream behavior denotes activity taking place as part of the “normal” process of negotiated decolonization and party politics. For example, acts of violence or unsanctioned protest would be subversive, while authorized campaigning for a political party would be mainstream. Activity such as support of a wildcat strike would fall in the middle. The other dimension considers women’s roles: whether the action was predominantly carried out by women, or whether women supported men as the primary agents. Figure 1 illustrates this two-dimensional space.

Figure 1. Spectrum of Political Participation.

Considering this spectrum, I argue that education is particularly important for the upper right quadrant: mainstream political behavior in which women are the primary actors. During late colonialism, participating in mainstream politics required knowledge about the colonial administration and the ability to navigate exclusionary political systems. Formal education was important for understanding how to operate within these systems and for generating the skill set to be successful at doing so (Skinner Reference Skinner2015). Describing women’s participation in Guinea’s nationalist movement, for example, Elizabeth Schmidt notes a distinction between the Rassemblement Démocratique Africain’s establishment of a national women’s committee “led by Western-educated elites,” including three teachers, the wives of civil servants, and a midwife, and the broad grassroots activity undertaken by market women to disseminate political information crafted by the party leadership (Reference Schmidt2005:116–28). While educated women were offered roles as primary actors within the party’s leadership structure, non-elite women adopted supportive roles, including selling party cards and taking care of imprisoned male activists (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2005:139). Women sometimes needed to violate gender norms to perform primary political roles. For women living in deeply patriarchal societies, certain types of education may have increased their comfort with this transgression. Tripp notes, despite its focus on domesticity, colonial education created opportunities for women, especially by encouraging membership in politicized women’s organizations (Reference Tripp2009:32–34). In some cases, these organizations featured prominently in independence movements.

Education enabled women to be primary actors in mainstream politics, but it was hardly a prerequisite for all political activity. Women could—and did—take on subversive activity and supportive roles without colonial education. This typology is not a hierarchy; I am not suggesting that primary/mainstream participation is “better” than other forms. Rather, it illustrates the myriad ways that women contributed to anti-colonial and nationalist movements. However, I argue that education did influence women’s opportunities for primary roles in mainstream politics in the late colonial period—a development that likely had lasting consequences for women’s participation in post-independence politics.

This study proceeds to examine three important ways that the British and French educational systems differed in the Gold Coast and Senegal, namely with respect to quantity, source, and curriculum. As the following sections demonstrate, the British system offered education to a greater quantity of girls from more diverse backgrounds, with a great degree of similarity between boys’ and girls’ curriculum. The French educated far fewer girls, overwhelmingly in French schools, with a greater emphasis on domesticity. In the political activity preceding independence, women in the Gold Coast played an active role in mainstream party organizing (alongside other more subversive forms of political behavior). In Senegal, women were less active and primarily took on supportive roles.

Differences in Girls’ Education in the Gold Coast and Senegal

Both the British and the French overhauled and consolidated their colonial educational systems during the 1920s. Generally speaking, the 1920s constituted a period of planning and expansion, and the colonial administrations began to reflect on their progress in the 1930s. World War II disrupted much social welfare policy in the 1940s, and the 1950s brought a renewed focus on the importance of education as colonial administrators began to consider greater autonomy or independence for the colonies. While the French and British were functionally similar as colonial administrators in many ways, the following sections explore three ways their educational policies differed.

Educational Quantity

Far more girls (and boys) had access education in British than in French West Africa, due to the way each administration designed its educational system. The British had a more expansive and decentralized concept of colonial education, focused on creating a population that would be able to contribute to the colonial economy and fill lower-level positions in the civil service (Whitehead Reference Whitehead2005). To accomplish this, they relied heavily on Christian missions. Schools could offer lower-level classes in local languages, making them more widely accessible to non-elite students (Albaugh Reference Albaugh2014:31).Footnote 2 Ericka Albaugh estimates that by the 1930s, average school enrollment in British colonies was three to six times as great as those in the rest of colonial Africa (Reference Albaugh2014:40). By 1960, an estimated 25 percent of the Ghanaian population was literate, as compared to 5 percent of the Senegalese population (Quist Reference Quist1994:128).

The British believed that mass education would maximize colonial productivity, and this attitude extended to educating girls. Minutes from the Gold Coast Legislative Assembly in 1919–20 express the opinion that “The community and the future race benefit when a trained girl teacher or nurse marries,” as she would presumably pass on “civilized” characteristics to the rest of her household (quoted in Bening Reference Bening2015:76). L.W. Tucker, an organizer of girls’ education, wrote in 1931 that educated girls would be “inculcated into habits of industry, cooperation, responsibility, and the capacity to deal with situations more complicated than those that arise in ordinary home life,” which would help to make their communities more stable, industrious, and prosperous.Footnote 3 This attitude fueled interest in the mass education of girls.

The goal of France’s “civilizing mission” was to assimilate select elite through education to embrace French language, religion, and culture as their own, particularly the small group of originaires in Senegal’s Quatre Communes who were considered “citizens” rather than “subjects” (Diouf Reference Diouf1998; Conklin Reference Conklin2000; Johnson Reference Johnson2010).Footnote 4 Believing that not all colonial subjects had the background or talents to move directly into these ranks, the French self-consciously pursued a strategy of limited recruitment—including for girls. For example, in a 1935 report on girls’ education, Inspector General Charton specified that they should only admit “daughters of notables, who have come to acquire the habits of a more evolved type of life,” thereby dramatically limiting the potential pool of female students.Footnote 5 School subjects were taught entirely in French, which further restricted education to the elite and reinforced the division between “assimilated” educated francophones and the indigènes who spoke little or no French (Bryant Reference Bryant2015:165).

These different philosophical and practical approaches to education resulted in far more girls attending school in the Gold Coast than in Senegal. In 1935, according to government reports from each colony, 15,020 girls were enrolled in primary education in the Gold Coast, compared to 5,400 girls at all levels in the entirety of the AOF.Footnote 6 In the Gold Coast, girls made up nearly 25 percent of the total primary school population of 61,950 (including both government and mission schools).Footnote 7 In Senegal, girls made up only 8 percent of the 12,312 students enrolled in official schools at all levels.Footnote 8 The Gold Coast was twice as populous as Senegal, but adjusting for population, Gold Coast girls attended schools at about seven times the rate of girls in Senegal. Furthermore, British reports during the 1930s reflect a preoccupation with increasing girls’ enrollment, while the French were more interested in maintaining exclusivity. The British were also concerned with educating older women to avoid “breaking the natural ties between the generations or hardening the old prejudices of the elder women” (Bening Reference Bening2015:102), and so supported literacy programs in both English and local languages. These programs began in the 1920s, and by the 1950s were so popular that women outnumbered men taking literacy exams nine to one (Skinner Reference Skinner2015:77).

Educational Sources

The British and French systems differed in the primary source of education: the French had a centralized government-run system (White Reference White1996:11), while the British formalized their partnership with missions (Whitehead Reference Whitehead2003:82). The British strategy reflected financial exigency; as the British Committee on Education Expenditure explained, “It is only through missions that [education] can spread inexpensively. A child’s education in a mission school costs the country a bare half of what it would cost in a parallel government school.”Footnote 9 Administrators issued a series of curricular guidelines, providing government grants to those schools that met their standards (White Reference White1996:12–13; Albaugh Reference Albaugh2014:31). While many schools operated outside this supervision, administrators expressed satisfaction that the quality of mission education approximated that of government schools.Footnote 10 Ewout Frankema (Reference Frankema2012:336) notes that denominational competition between the mission societies increased the supply of education, while at the same time likely improving its quality. In the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast alone, the Wesleyans, the Basel Mission, the Church of Scotland, and the White Fathers all competed for congregants by running schools.Footnote 11 Each mission had the goal of “converting and saving as many souls as possible,” including those of girls (Frankema Reference Frankema2012:336). Reports state that “girls go freely to boys’ schools,” which, the Committee on Education Expenditure happily noted, reduced the necessity for separate girls’ schools.Footnote 12 Even so, some missions opened programs specifically to retain female students beyond primary education, including those at the Scottish Mission Girls’ School, the Presbyterian Aburi Training College, the Roman Catholic Mission, the Order of the Holy Paraclete, and the Wesley Girls’ School. The missions also contributed to teacher training, including the Ewe Presbyterian Church, the Methodist Mission, and the Roman Catholic Mission.Footnote 13

By the 1930s, the diversity of religious schools, co-educational government schools, and dedicated girls’ schools gave Gold Coast girls a variety of educational options; decentralization in the British approach also led to variation in the content of girls’ education. While there were large financial incentives to achieve “Assisted” status, ensuring some homogeneity in mission school curricula (Skinner Reference Skinner2015:33–34), these mission schools had a great degree of freedom once they had met the minimum curricular standards. They also had the advantage of being embedded in local communities. Often the mission schools would focus on “suitable training in domestic economy” for girls, but the standards for colonial financial assistance meant that girls were also taught literacy and other subjects (especially prior to adolescence) (Bening Reference Bening2015:75).

Alternatively, the French were hostile to religious education, and the 1905 Law on the Separation between State and Church accelerated the demise of mission education in French colonies (Cogneau & Moradi Reference Cogneau and Moradi2014:695). Islamic Qur’anic schools were the exception; the French remained tolerant of these institutions to maintain political order in areas with large Muslim populations, such as Senegal. However, these schools tended to focus on rote memorization of the Qur’an in Arabic, and they enrolled very few girls (Frankema Reference Frankema2012:346). In Senegal, the French created a centralized system in which, as Dr. Bryant Mumford described in 1936, “the state takes complete responsibility for the students it has chosen.”Footnote 14 For girls (or boys) who wanted “Western” education in French colonies, government-run schools were the only option, with a centralized curriculum oriented around French conceptions of gender-appropriate coursework.

Educational Content and Curriculum

Domestic training was an important component of girls’ education for both the British and French, but they differed in its centrality to the curriculum. In the Gold Coast, domestic science was generally an addition to co-curricular courses. In Senegal, girls were predominantly educated in separate schools where domestic science was the primary subject.

The British approach to colonial education was generally paternalistic, but as early as 1929, educators such as Ms. E.S. Fegan advocated for girls’ education because “she may, too, have to take a leading part herself in some of the many activities for the amelioration of the conditions of her own people.”Footnote 15 During his tenure through the 1920s, Director of Education D.J. Oman was a vocal advocate for girls’ education, as well as for employing local women as teachers.Footnote 16 In 1933, his successor, Gerald Power, focused on encouraging girls to go to school precisely because he feared that, without explicit attention, the girls would be “left behind.”Footnote 17 Administrators such as Esther Appleyard emphasized that domestic science coursework “provides excellent opportunities for training the girls to think, reason and act independently.”Footnote 18 This approach reflected the idea that schools should prepare girls for a role in public life.

In the Gold Coast, the overwhelming majority of schools that were either government-run or government-assisted were “mixed,” including both boys and girls. To gain their primary certificate and the possibility of advancing to secondary school, both boys and girls took the same tests in arithmetic and composition, and could choose either “general subjects,” including “nature study,” hygiene, citizenship, geography, and history, or “domestic science,” which included “sections on laundry, cookery, housewifery, hygiene, and child welfare.”Footnote 19 This curricular structure gave girls access to general primary education with optional instruction in domestic science. In the 1930s, those domestic science courses were added specifically to retain female students and to “secure public interest in the education of girls,”Footnote 20 though by the mid-1950s the domestic science instructors campaigned for this exam to be mandatory for girls because so many opted to take only the co-educational subjects.Footnote 21

This co-educational structure extended to secondary courses. At Achimota College, the Gold Coast’s flagship secondary school, men and women took the same course in teacher training, which was gender-segregated only for additional domestic science courses.Footnote 22 Shoko Yamada (Reference Yamada2018:226) argues that Achimota College was emblematic of the more progressive educational models at the time, which considered “the role of wives as not merely maids but the equal partners of men in maintaining a civilized family life.” While it is unlikely these ideas about gender equality were universal, Achimota was committed to recruiting young women, even going so far as to set lower tuition for girls (Yamada Reference Yamada2018:227). As a result of these efforts, by 1936, 213 of the 633 students at Achimota were women, as were 66 of the 152 teachers in training (Bening Reference Bening2015:253). The colonial administration so supported the recruitment of women teachers that, in 1935, it established a grant program to support women’s training at Achimota and bonded them to teaching in government schools for five years after completing their degrees.Footnote 23 In 1937, 121 of 869 teachers in the Gold Coast were African women.Footnote 24

Not all schools were equally progressive in their approach to girls’ education. For example, the Scottish Mission Girls’ School at Krobo proposed a curriculum including such “housewifery notes” as “look pretty at your house work and cooking. Take pride in your appearance even when washing and cooking. An apron is easily washed and can be taken off quickly when soiled. Which is easier to wash, an apron or a dress?” It further instructed students to beware “the deadly d’s: dust dirt [and] darkness causes disease,” and made them aware that they should use different techniques for cleaning “European” versus “African” bathrooms.Footnote 25 Nevertheless, Gold Coast girls had a relatively high degree of access to schools in which they were taught the same curriculum as boys, where domestic science was a curricular addition rather than a substitution.

The French had a markedly different orientation toward girls’ education, particularly in Senegal, where their assimilationist policies were the most intense. Educating girls and young women was key to their vision of “creating Frenchmen,” and they considered women central to society’s social and moral development. Jules Carde, the Governor General of the AOF, explained it was important to “ensure our influence over the native women. Through the men, we can increase and improve the country’s economy. Through the women, we touch the very heart of the native home, where our influence penetrates.”Footnote 26 Specifically, the French goal of girls’ education was to create a “civilizing influence” for men and to propagate French culture, as part of their broader project of creating an intercontinental “French family.” They thought that instilling French civilizational values in women would accelerate the “evolution” of native culture because an educated woman could “consolidate in future generations the new habits she acquired through education, and secure our actions permanently in native society.”Footnote 27 Administrators were preoccupied with women’s potential to influence culture through their maternal role. They wrote that women should be “filled with the civilization that they are charged with transmitting,”Footnote 28 and that educating women would allow “our ideas and our civilization to penetrate the masses.”Footnote 29 The curriculum in girls’ schools focused explicitly on training Senegalese women to behave like a specific vision of the French housewife, emphasizing French language, culture, and domestic training—even for those select women who gained a secondary education.

By the mid-1930s, the French, like the British, noted the impetus to train women as civil servants. The administration envisioned two levels of education for girls: one “practical,” which would involve regional girls’ schools where “practical housework, hygiene, and childcare take the largest space in the schedule,” and an advanced level of training for young women to join the French civil service as teachers, nurses, and midwives.Footnote 30 Unlike in the Gold Coast, where women could train in co-educational programs, in Senegal women attended separate programs that trained women for a “double role”: first to fill the employment needs of the administration, and second to fill her “social and domestic roles.”Footnote 31 Therefore, even the most elite schools training young women to be teachers and midwives divided the curriculum between instruction in French and science and “domestic” instruction about “running a household, cooking, and caring for children.”Footnote 32 The administration’s syllabus for the midwifery school specified that weekly instruction should include twelve hours of French, two hours of math, three hours of science, seven hours of dress-making and house-cleaning, two hours of singing and drawing, and four hours of working in a clinic.Footnote 33 This program differed from domestic science programs only in the nine hours per week spent on basic math, science, and clinic work. Further documents discussed establishing a “school for wives and mothers,” which would focus on training women to be “light-hearted and good humored…active, hard-working, frugal, and modest.”Footnote 34

Consequences of Educational Difference

These educational differences between the French and British systems translated to dramatically different lived experiences for school-aged girls in Gold Coast and Senegal from the 1920s. Girls in the Gold Coast had a much greater likelihood of being enrolled in school. While their experiences varied depending on which organization ran the school they attended, most girls attended classes alongside boys. Like the French, the British system included a domestic science component. However, most girls in the Gold Coast took domestic science as a supplement to the standard curriculum. In Senegal, a much smaller percentage of girls, concentrated among the urban elite, enrolled in schools. Those who did gained instruction primarily in spoken and written French and domestic tasks, even if they became nurses or teachers. By contrast, young women in the Gold Coast who advanced to vocational instruction often attended co-educational facilities such as Achimota College, where they earned the same credentials as men. These differences, which were apparent when both colonial administrations consolidated their educational programs in the 1920s, intensified over time. By the mid-1930s, the colonial government of the Gold Coast dedicated significant resources to girls’ education and to training women to perform in the civil service.

By the time of independence, women in Ghana and Senegal held distinctly different levels of social status and aggregate education. In Ghana, women had on average more years of schooling and higher literacy rates than women in Senegal; fewer than 1 percent of Senegalese women could speak or write French in 1965 (Callaway & Creevey Reference Callaway, Creevey, Charlton, Everett and Staudt1989:98), while by 1960 between 10 and 15 percent of Ghanaian women were literate in English.Footnote 35 Women in Ghana had also been more completely integrated into the economic structure, taking on more civil service positions—including as teachers of domestic science and other topics. Finally, Ghanaian women had access to similar curricula as men, and many gained their credentials from co-educational facilities. In Senegal, educated women had been trained primarily for domestic and social roles. One would expect, therefore, that Ghanaian and Senegalese women would engage differently in nationalist politics.

Women’s Mobilization during Independence Movements in Ghana and Senegal

Nationalist and independence movements in the Gold Coast and Senegal originated in the educated class and gained momentum in the decade after World War II, as the contradictions of colonialism became increasingly evident and unsustainable. However, each movement proceeded differently as a result of the different orientations the French and the British had toward their colonies. In the Gold Coast, the first party to agitate for independence was the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC), formed by southern urban elites who were upset with their second-tier status under colonialism. The Convention People’s Party (CPP) subsequently spun off, mobilizing denizens who had some education but were less elite, known as the “verandah boys,” who were “mostly Standard VII graduates…unemployed or informally employed.” (Bob-Milliar Reference Bob-Milliar2014:288). The CPP’s organizational structure developed from broad grassroots efforts and relied heavily on women as community mobilizers. The nationalist movement resulted in a transitional government in 1951 and full independence in 1957.

Senegal’s nationalist movement was part of the AOF’s federalist campaign. Also gaining momentum after World War II, this movement was top-down and involved elite-level negotiations between parties with representatives from the various AOF territories. Because of Senegal’s more privileged political spot among France’s colonies, its representatives had an outsized influence on the negotiations that ultimately led to the establishment of the Mali Federation in 1958. Because higher education in the AOF was available exclusively in Senegal, party elites from each colony were disproportionately products of the same schools in Dakar and France, where pan-African and anti-colonial ideas began to take root (Thioub Reference Thioub, Chanson-Jabeur and Goerg2005). The Mali Federation was short-lived, and Senegal gained full independence in 1960 under the leadership of Léopold Senghor and his Bloc Démocratique Sénégalais (BDS). Unlike in the Gold Coast, with few exceptions, the independence process in Senegal was an elite affair and generally excluded women from the ranks of those engaged in the negotiations. Babacar Fall (Reference Fall, White, Miescher and Cohen2001:215) notes that Senegal’s political elite was “mostly masculine,” precisely because there were so few educated women.

Ultimately, the characteristics of the nationalist movements in the Gold Coast and Senegal were linked to the respective colonial educational systems, and women’s form of involvement in each also reflected these systems and the societies in which they were embedded.

Women and the Nationalist Movement in the Gold Coast

In Ghana, women variously adopted both primary and supporting roles in mainstream nationalist politics. Women exerted influence from the beginning of UGCC agitation for independence, particularly under the leadership of Kwame Nkrumah. Their role in the movement expanded when the CPP split from the UGCC, and many (including Nkrumah himself) credit the CPP’s ultimate electoral success to the energies of women grassroots organizers (Allman Reference Allman2009; Bob-Milliar Reference Bob-Milliar2014; Manuh Reference Manuh, Konandu and Campbell2016). While much of this political energy came from market women who were not necessarily formally educated, other women who were products of the colonial educational system took prominent leadership roles in the nascent party (Tsikata Reference Tsikata, Imam, Mama and Sow1997:389–90; Manuh Reference Manuh, Konandu and Campbell2016:290). The Women’s Section of the CPP formed shortly after the party itself, and its leadership included educated women such as Mabel Dove Danquah and Akua Asabea Ayisi, who spread the party’s message by writing articles for the Evening News, Leticia Quaye, who (alongside Ayisi) was active in the party’s Positive Action Campaign and served prison time for civil disobedience (Manuh Reference Manuh, Konandu and Campbell2016:286), and Hannah Kudjoe and a team of “outstanding political propagandists,” including Alice Appia, Essie Mensah, Margaret Thompson, and Lilly Appiah (Allman Reference Allman2009:19). In 1951, the CPP appointed Leticia Quaye, Hannah Kudjoe, Ama Nkrumah, and Sophia Doku as Propaganda Secretaries, and they were integral in recruiting men and women across the country into the CPP’s Women’s Section and Youth Wing (Tsikata Reference Tsikata, Hansen and Ninsin1989:77–78; Manuh Reference Manuh, Konandu and Campbell2016:287). These women, most of whom had either partially completed or completed primary school, utilized their literacy and civic skills as extraordinarily effective party mobilizers for the CPP.

Women’s actions during the Gold Coast’s independence movement won them a formal seat within Ghanaian politics as early as the transitional government, when Mabel Dove Danquah, supported by Nkrumah and the CPP’s Central Committee, became the first woman elected to office in 1954 (Bob-Milliar Reference Bob-Milliar2014:305; Gadzekpo & Newell Reference Gadzekpo and Newell2004). In 1959, the National Assembly passed the stunningly progressive Representation of the People (Women Members) Act, which set aside ten seats of the National Assembly for women (Manuh Reference Manuh, Konandu and Campbell2016:287). In recognition of their service, the CPP further appointed women (some of whom had been trained as teachers under the colonial administration) to serve on boards of corporations, schools, and town councils, and actively promoted women’s continued education and vocational training (Allman Reference Allman2009:41; Manuh Reference Manuh, Konandu and Campbell2016:288–89). Others, such as Achimota graduates Susanna al-Hassan and Ramatu Baba, went on to become members of parliament during Ghana’s First Republic. In 1960, the CPP consolidated women’s political actions into the singular National Council of Ghana Women (NCGW) (Tsikata Reference Tsikata, Hansen and Ninsin1989:79). While some have criticized this move as a means for the party to control women’s activities, the NCGW also contributed to maintaining women’s presence in the public sphere (Tsikata Reference Tsikata, Hansen and Ninsin1989:79; Allman Reference Allman2009:41–42).

As noted above, market women also played an instrumental supporting role as grassroots organizers, and Asante women were active in the National Liberation Movement (NLM), an Asante nationalist movement that resisted integration into independent Ghana. While market women were essential in mobilizing the masses behind the CPP (Akyeampong & Aikins Reference Akyeampong and de-Graft Aikins2008; Tsikata Reference Tsikata, Imam, Mama and Sow1997), they were less likely than better-educated women to be recruited into leadership positions. Allman (Reference Allman1993:103) notes that NLM women “stood in the forefront of this popular resistance.” However, their activities tended to be restricted to supporting roles such as attendance at rallies and demonstrations.

Ghana’s First Republic ended in 1966 when a coup ousted Nkrumah. By the end of his tenure, the CPP’s relationship with women had become more fraught, as it frequently scapegoated Ghana’s market women for the country’s economic struggles. The tumultuous period that followed closed the political sphere in general. Nevertheless, from the post-World War II period through the mid-1960s, women played an active role in both the independence movement and in national politics. These activities transcended class and were not restricted to educated women; however, literate women who had experienced at least some formal schooling played an essential role in CPP organizing and politicking. The party’s subsequent focus on providing educational and professional opportunities for girls and women is a testament to the importance of education in shaping women’s access to the public sphere.

Women and the Nationalist Movement in Senegal

As in the Gold Coast, nationalist movements began to coalesce in Senegal (and the rest of the AOF) after World War II, in part because of the jarring experience many of the elites endured under Vichy rule (Morgenthau Reference Morgenthau1964:134). However, the administrative structure of the AOF and France’s relationship with its colonies also shaped Senegal’s nationalist movements in a way that distinguished them from the Gold Coast. As described above, the French educational system had produced a small class of elite colonial “citizens,” many of whom were well versed in assimilation and believed that “African emancipation would take place through integration with greater France, rather than through secession from it” (Chafer Reference Chafer2002:5). Much of the nationalist movement was thus oriented around discussions of various forms of federation rather than outright sovereignty, and came from three overlapping constituencies: the highly educated elite, who seized on French ideals of democracy and equal rights; the labor unions, who agitated for equal pay and equal treatment between French and African workers; and the student movement, which demanded full assimilation into the French system (Chafer Reference Chafer2002). Recognizing that sovereignty of each of the separate territories within the AOF would create economic and budgetary challenges for the newly independent states, most of the participants in these movements preferred federation and an ongoing relationship with France, but as equal partners rather than as colonial subjects (Cooper Reference Cooper2014:1–2).

More so than in the Gold Coast, these movements were concentrated among the French-speaking elite, nearly all of whom were products of the French educational system (Morgenthau Reference Morgenthau1964). Early political figures in Senegal were predominantly graduates of the Ecole William-Ponty, some of whom had been educated abroad, and had achieved status as urban white-collar workers. The graduates of William-Ponty and the members of the trade unions were exclusively male, and there is little indication that women partook in the students’ nationalist movement. As Lucy Creevey (Reference Creevey1991:365) argues, “the infusion of [French] ideas through their example of an appropriate lifestyle and the beginnings of a Western school system could not help but be important factors molding the new class of leaders who would take over Senegal at independence. Their ideas included a view of women as subordinate to men as well.” Fall (Reference Fall, White, Miescher and Cohen2001) notes that women’s limited access to education meant there were few high-profile women in nationalist politics. The first two women (Caroline Diop and Maimouna Kane), both highly educated, were only appointed as ministers in 1978. According to Fall, “the dominant image of the women participating in political life is that of the socialite woman providing some folklore,” and women who were able to take a more active role in mainstream politics were few and far between (Reference Fall, White, Miescher and Cohen2001:215).

While Fall notes that there is a “weak presence of women in Senegalese historiography” (Reference Fall, White, Miescher and Cohen2001:15), there are a two notable instances of women—both elite and non-elite—supporting political movements as nationalist sentiment began to increase. The first, taking place in elite society in Dakar, involved Senegalese women gaining the right to vote. Cooper (Reference Cooper2014:46–51) describes the event in detail. The originaires of Senegal’s Quatre Communes had long enjoyed special status as “citizens” within the colony, and when French women obtained the vote in 1944, citizens of the Quatre Communes assumed that it would include Senegalese female citizens. It did not, and the decision to prevent Senegalese women from enjoying the franchise inspired Lamine Guèye, one of Senegal’s most prominent politicians, to begin a campaign in favor of women’s suffrage. Elite women became involved in this campaign largely to support Guèye’s party, as doubling the Senegalese voting population would improve representation for the originaires. Indeed, the municipal elections of 1951 represented an overwhelming victory for his party, in part because of women’s votes. However, despite gaining suffrage, these elite women subsequently faded from Dakar’s late-colonial political scene.

The second instance concerns the railway strike of 1947–48. This strike, led by African railway workers demanding that they be treated equally to European employees was not an explicit nationalist movement, but historians such as Frederick Cooper (Reference Cooper1996) have argued that it was part of the tableau of anti-colonial movements that began chipping away at the French imperial model in the AOF. The strike lasted five months and was ultimately successful, resulting in wage increases, recognition of unions, and family allowances for civil servants (Cooper Reference Cooper1996:83). The strikers lasted for so long in large part because of women’s support; according to Cooper’s account of oral testimonies, women sustained the strikers by providing food, harassing would-be strike-breakers, and taking on additional market activities to supplement family income (Reference Cooper1996:95–96). While their actions were essential for the ultimate success of the strike, Cooper’s informants described the women as acting in a supporting role within their families and communities, rather than as primary actors.

Aside from these incidents, women are largely absent from Senegal’s nationalist historiography. This is not to say that Senegalese women were passive; however, what activities they may have undertaken were not prominent enough to attract widespread documentation. With the exception of fighting for their franchise, Senegalese politicians paid little attention to their potential political energy. Indeed, very few women had the education that would have allowed them to partake in the elite-level movement, and those with the requisite education had been trained almost exclusively in domestic arts. In stark contrast to that of the Gold Coast, Senegal’s nationalist movement was dominated by the educated male elite.

Alternative and Additional Explanations

The respective colonial educational systems did not constitute the only difference between the Gold Coast and Senegal that could have shaped women’s participation in nationalist movements. Of the myriad differences between the two colonies, three stand out as possible alternative explanations for women’s rates of public political involvement in nationalist movements: cultural differences (specifically the influence of Islam), differences in women’s economic roles (particularly the clout of Ghana’s market women), and the influence of matrilineality. While each of these factors undoubtedly shaped the experiences of women in Senegal and the Gold Coast in distinct ways, and likely influenced the way women experienced the public sphere more broadly, none is sufficient to explain differing rates of women’s participation without also considering the influence of the formal education system.

Cultural differences—especially religious differences—between Senegal and Ghana present an important alternative explanation. Specifically, the prevalence of Islam in Senegal could have had a dampening effect on women’s political participation, though there is reason to be skeptical of this explanation. While scholars such as Steven Fish (Reference Fish2002) have argued that the cultural influence of Islam contributes to gender inequalities, others (Donno & Russett Reference Donno and Russett2004; Rizzo et al. Reference Rizzo, Abdel-Latif and Meyer2007; Kang Reference Kang2015) have noted that those observations are better suited to the Shia and Sunni varieties of Islam that dominate Arab states than the Sufi varieties common to West Africa. Those who argue that Islam is uniquely bad for women (i.e., Fish Reference Fish2002; Inglehart & Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2003) note that it has strong dictates restricting women to the private sphere (Callaway & Creevey Reference Callaway, Creevey, Charlton, Everett and Staudt1989). Yet, major world religions are multivocal; local culture shapes the practice and doctrine of new religions (Stepan Reference Stepan2000:48). Anthropologists have noted that the arrival of new cultures through trade, religion, and migration often results in “bricolage” or “cultural heterogeneity”—not the wholesale replacement of one set of cultural ideas with another (Pritchett Reference Pritchett and Englund2011). One would therefore expect that local manifestations of major religions would likely reflect pre-existing beliefs about gender. Callaway and Creevey (Reference Callaway, Creevey, Charlton, Everett and Staudt1989) argue that women across West Africa were treated as second-class citizens prior to the arrival of Islam and note that elites used both Islam and Christianity to justify women’s subordination. If Islam kept women in the private sphere more so than other religions, then one would expect women’s participation to be lower relative to men in countries with a large Muslim population. However, in earlier work I demonstrate in cross-country regression analysis that the predominance of Islam (either as a population majority dummy or as a population percentage) not only failed to explain gender gaps in participation in African countries, but was sometimes associated with a smaller gender gap, indicating that Islam has an inconsistent and non-systematic relationship to women’s rates of political participation relative to men’s in the African context.Footnote 36 Religion aside, patriarchal practices are prevalent throughout both Senegal and Ghana. Without diminishing the importance of religion’s influence on political behavior, the prevalence of Islam is not a particularly good explanation for women’s limited public engagement in the post-World War II urban centers of Senegalese politics.

However, religious difference did play an important role in the form of education available in each colony. British reliance on mission schools was fundamental to their ability to expand educational opportunity. Frankema (Reference Frankema2012) explains that this reliance was possible precisely because, with a few notable exceptions, much of the British Empire in Africa was located in areas without a large Islamic influence (especially as compared to the French territories). In the Sahel and parts of North Africa where Islam had already taken root prior to “official” colonization, mission schools were an explicit threat to the system of Qur’anic education. The French found it useful to negotiate and collaborate with Islamic leaders in predominantly Muslim areas, and therefore refrained from supporting any religious competition—allowing the operation of Qur’anic schools instead (Babou Reference Babou and Diouf2013:128–29; Bryant Reference Bryant2015). As Frankema notes, female enrollment in traditional Islamic schools was very low, so the proliferation of Qur’anic rather than Christian mission schools had an adverse influence on girls’ overall access to education. The religious geography therefore provides important context for understanding the colonial educational policies.

Another possibility is that women in the Gold Coast participated more in the nationalist movement because they were already firmly entrenched in the public sphere through their economic activities, particularly as market women. Given the prominence of market women in the CPP’s popularization, it would be folly to discount this explanation. However, as described above, the market women largely (though not exclusively) played different roles than the better educated women. While the market women were essential in rallying public support for the CPP, the literate women of the Gold Coast, who had completed at least some primary school, performed essential tasks in the CPP leadership. Women’s history of public economic activity in the marketplace was certainly integral to the broad mobilization of women into supporting roles, but education was essential for the women who took on primary roles within the nationalist movement and independent government.

Finally, some analyses have highlighted the importance of matrilineality in pre-colonial social systems for women’s status in post-colonial society. Amanda Lea Robinson and Jessica Gottlieb (Reference Robinson and Gottlieb2019), for example, demonstrate that the contemporary gender gap in political participation narrows in localities where a significant portion of the population comes from ethnic groups with matrilineal practices. They argue that this outcome stems from women’s greater intra-household decision-making power in such societies, which normalizes women’s involvement in community-level decision-making. While West Africa has fewer matrilineal groups than other regions, notably one of the largest—the Akan—is in Ghana. Many Akan women participated in NLM’s ethno-nationalist movement, but Akan matrilineality cannot account for the ongoing participation of non-Akan women in the CPP’s campaigns. Additionally, if matrilineality were to account for the different rates of women’s nationalist participation in the Gold Coast and Senegal, one might expect that women from matrilineal groups in Senegal would be relatively more active. However, Lucy E. Creevey (Reference Creevey1991:362–63) has argued that the Serer of Senegal—who are both matrilineal and more likely to be Christian than Muslim—are neither better educated nor professionally placed than non-matrilineal Wolof women, and there is no evidence that they participated at higher rates during the nationalist struggle. One cannot observe the counterfactual (what if the Wolof were matrilineal?) for Senegal, but matrilineality offers only a partial explanation for women’s political activity in Ghana.

These alternative explanations—religion, economic integration, and matrilineality—all offer important nuance in how women in Senegal and Ghana navigate their environments and make decisions about their degree of participation in public life. However, these alternatives do not explain women’s varying rates of political involvement without also considering education.

Conclusion

Across Africa, colonial educational policies created or deepened gender disparities by educating more boys than girls and offering curricula differentiated by sex. However, there was a great degree of variation within this general trend, with implications for the way women carved out opportunities for engagement in the public sphere. This study has focused specifically on political behavior in nationalist movements, arguing that British educational policies in the Gold Coast created more opportunities for women to take on primary roles within the CPP, along with engagement in other forms of political participation. In Senegal, more limited educational opportunities for girls contributed to their relative exclusion from nationalist politics. However, it is worth considering whether the Gold Coast and Senegal are broadly representative of British and French policies.

Despite colonial administrations’ attempts to centralize policy decisions, every former colony had idiosyncrasies that influenced policy implementation. Without suggesting that the British and the French implemented their policies homogenously and consistently throughout their respective colonial regimes, there is reason to argue that Gold Coast and Senegal are generally representative. First, the quantities of students educated in the Gold Coast and Senegal are consistent with trends across British and French colonies. Because Dakar was the administrative capital of the AOF, access to education was greater there than elsewhere in the federation, where girls had even fewer options to attend Western-style schools. British investment in education varied according to the economic potential of the colony, but mission schools were ubiquitous. Given these general similarities across the British and French territories, one would expect that girls consistently had greater access to education from a variety of sources in British colonies—an assumption that is borne out in the data. While there is considerable variation within British and French territories, Tripp (Reference Tripp2009) noted that women in British colonies were more active in nationalist movements than elsewhere.

At independence, girls’ prospects for education in Ghana and Senegal varied; to what extent did these colonial policies generate lasting variation? Evidence suggests that the educational legacies of each system have persisted. Ghana continues to out-perform Senegal both in terms of raw numbers of students and in the female-to-male student ratio.Footnote 37 In Senegal, Jutta Bolt and Dirk Bezemer (Reference Bolt and Bezemer2009), along with Michelle Kuenzi (Reference Kuenzi2011), all note that, despite planned educational reforms in 1969, 1979, and 1984, the foundations of the Senegalese education system remain unchanged; most teaching is still in French with French-style curriculum, which in many cases remained gender-segregated by the end of the twentieth century. In the 1970s, the government still specified that the curriculum for middle school girls should “allow them to meet familial needs,” such as making clothes, cooking healthy meals, making crafts to decorate their homes, and understanding how to clean properly.Footnote 38 Similarly, the national teachers’ college reserved domestic instruction for female students, such as “making dolls, making clothes for dolls, babies, and children…housekeeping, healthy cooking, utilization of cleaning products, running a good household, mending clothing, washing, cleaning, ironing, and using modern home appliances.”Footnote 39 In Ghana, girls’ education continued to have domestic topics as supplements to, rather than instead of, the standard curriculum, and correspondence from the domestic science teachers in the early independence period indicates that many girls who attended school treated the subject “with a certain amount of apathy” and managed to evade the coursework.Footnote 40 While each country has experienced changes in national politics and in the nature of education over time, their educational systems are each linked to their colonial pasts, both in terms of raw numbers and in terms of integrating girls into the educational system.

How these educational systems continue to influence women’s political behavior is beyond the scope of this study, but it is worthy of future investigation. Both Senegal and Ghana have experienced dramatic political changes since independence, and it would be instructive to understand how women’s educational opportunities have shaped the way they engage with national politics over time. Given the continuities between the late colonial and early independence educational systems, future work should investigate the relationship between education and patterns of political engagement over time. Additionally, while I have argued for the representativeness of these cases, more systematic comparative work is warranted to explore these patterns elsewhere.

Acknowledgments

This work would not have been possible without the archival research assistance of Aminata Mbodj, the tireless staff at Kew, ANS, and PRAAD, and financial support from the NEH committee at the College of Idaho. I also thank Lauren MacLean, Jessica Achberger, Elizabeth Sperber, Elinor Accampo, and three anonymous reviewers for providing invaluable feedback on earlier drafts.