Like innovation, the concept of health is multidimensional with multifactorial determinants (1), making healthcare and innovation in healthcare a multidimensional-multifactorial complex construct. While the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has exposed numerous gaps in the above dimensions in the healthcare systems worldwide, it also acted as a catalyst for healthcare innovations and innovative technology and has been the focus of policy initiatives (Reference Mukherjee2). However, not all innovations or technologies add value or are sustainable for healthcare systems. Hence, sustainable healthcare innovations must be identified early, adapted contextually, and scaled up effectively by policy makers, which meet the healthcare system’s objectives and are beneficial for society. Given the complex interactions between health technology, innovation, and policy, coupled with an uncertain future, policymakers are faced with tough decisions. In this context, this article discusses the emerging question of how science can help in this decision making in the emerging “new normal.” To answer this question, we used inductive epistemology and applied the principles of pragmatism and historicity to explore the role of two existing scientific mechanisms, health technology assessment (HTA) and responsible innovation in health (RIH), as a source of evidence in policies regulating the emergence and use of innovative health technologies. The epistemological position of this article is that science is affected by the social and historical setting and requires revisions based on changing contexts. Using inductive reasoning on this position, this article attempted to arrive at meaningful conclusions from observations, patterns, resemblances, and experiences. Using this process, we analyzed HTA and RIH by applying the principles of pragmatism and historicity. Through the lens of historicity, we understood that both RIH and HTA concepts, practices, and values have developed over time and discussed their practical application using pragmatism.

A narrative synthesis approach, which involves synthesis of findings through literature review and the use of text to summarize and explain the findings, has been used to present the discussion, which is structured into three sections. The first section of the narrative introduces the challenges in the interaction of health innovation, technology, and policy, followed by the second section, which discusses existing mechanisms in HTA and RIH to address these challenges. Finally, the third section presents a synthesis of these narratives to discuss the intersection between HTA and RIH and the scope for an integrated application in the “new normal” emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Innovation and Technology in Healthcare: Definitions, Dimensions, and Dilemma

The World Health Organization (WHO) definition considers that healthcare innovation is to develop and deliver new or improved health policies, systems, products and technologies, and services and delivery methods toward achieving Universal Health Coverage (UHC) (3). Technology can be an innovation and a driver of innovation, and health technology includes innovative products, organizational processes, and programmatic and systemic interventions (4). However, technological innovation does not continually improve health or create value relative to costs (Reference Cutler and McClellan5;Reference Newhouse6). The COVID-19 pandemic has brought many health technology dimensions to the forefront. For example, the PLACID trial for the use of high-cost convalescent plasma for COVID-19 showed the ineffectiveness of this intervention, but it had already received regulatory approvals for patient use in several countries (Reference Agarwal, Mukherjee and Kumar7). With the increasing number of new technologies being developed, new and complex policy challenges arise for meeting the socio-cultural-political dimension of technology adoption in healthcare delivery, which question the moral, political values, and power relationships in determining a technological configuration and its use (Reference Silva, Lehoux, Miller and Denis8). In this context, the following section explores two existing scientific mechanisms that attempt to address the abovementioned interactions and challenges—HTA and RIH.

HTA and RIH

To address the complexities associated with the use of technology, technology assessment (TA) was developed as a multidisciplinary process to evaluate the medical, ethical, economic, and social aspects of technology and provide evidence on the value of technology for decision makers across different decision-making contexts. TA comes in various forms (Reference Nentwich9); however, the one closely associated with health technology and innovations is HTA and has about 50 years of existence. Tracing these 50 years historically, the use, definition, and application of HTA have evolved (Reference Banta and Jonsson10;Reference Kristensen, Lampe and Wild11), and the most recent HTA definition (Reference O’Rourke, Oortwijn and Schuller12) explicitly provides a health systems approach for determining the value of health technologies and is closely aligned with the objectives of health innovation and UHC (Reference Mukherjee13).

Advancing this systems perspective, a holistic concept of responsible innovation (Reference Silva, Lefebvre, Oliveira and Lehoux14) and “responsible research in innovation” (RRI) (Reference Stilgoe, Owen and Macnaghten15) was introduced in innovation literature from the developed countries. RRI has snowballed over the past decade and has significantly influenced the European research policy landscape and has been suggested as offering a new lens to consider and govern the innovation process (Reference Burget, Bardone and Pedaste16). These concepts were developed further and applied to health systems literature in Canada to develop the concept of “RIH” (Reference Silva, Lehoux, Miller and Denis8;Reference Demers-Payette, Lehoux and Daudelin17). Historically, RIH is a relatively new concept and consists of a “collaborative endeavor wherein stakeholders are committed to clarify and meet a set of ethical, economic, social and environmental principles, values and requirements when they design, finance, produce, distribute, use or discard socio-technical solutions to address the needs and challenges of health systems in a sustainable way.” (Reference Silva, Lehoux, Miller and Denis8) This definition posits that RIH encompasses social and sustainable innovations, which aim at creating social change and benefit health and well-being. Thus, both HTA and RIH have commonalities and scope for mutual interaction and learning (Reference Lehoux, Silva, Sabio and Roncarlo18;Reference van Est19), and both are aligned with the objectives of UHC and Sustainable Development Goals(SDGs). For example, components of the INTEGRATE-HTA project (Reference Bijlmakers, Mueller, Kahveci, Chen and van der Wilt20) consider involving stakeholders early and examining outcomes beyond clinical and cost-effectiveness. Analyzing these similarities inductively and in the context of early HTA and its life cycle approach in the “new normal” emerging from this pandemic, the following section proposes an integrated approach of RIH and HTA in linking health innovations, systems, and policies.

Integrated Approach of RIH and HTA-Ecosystems Framework

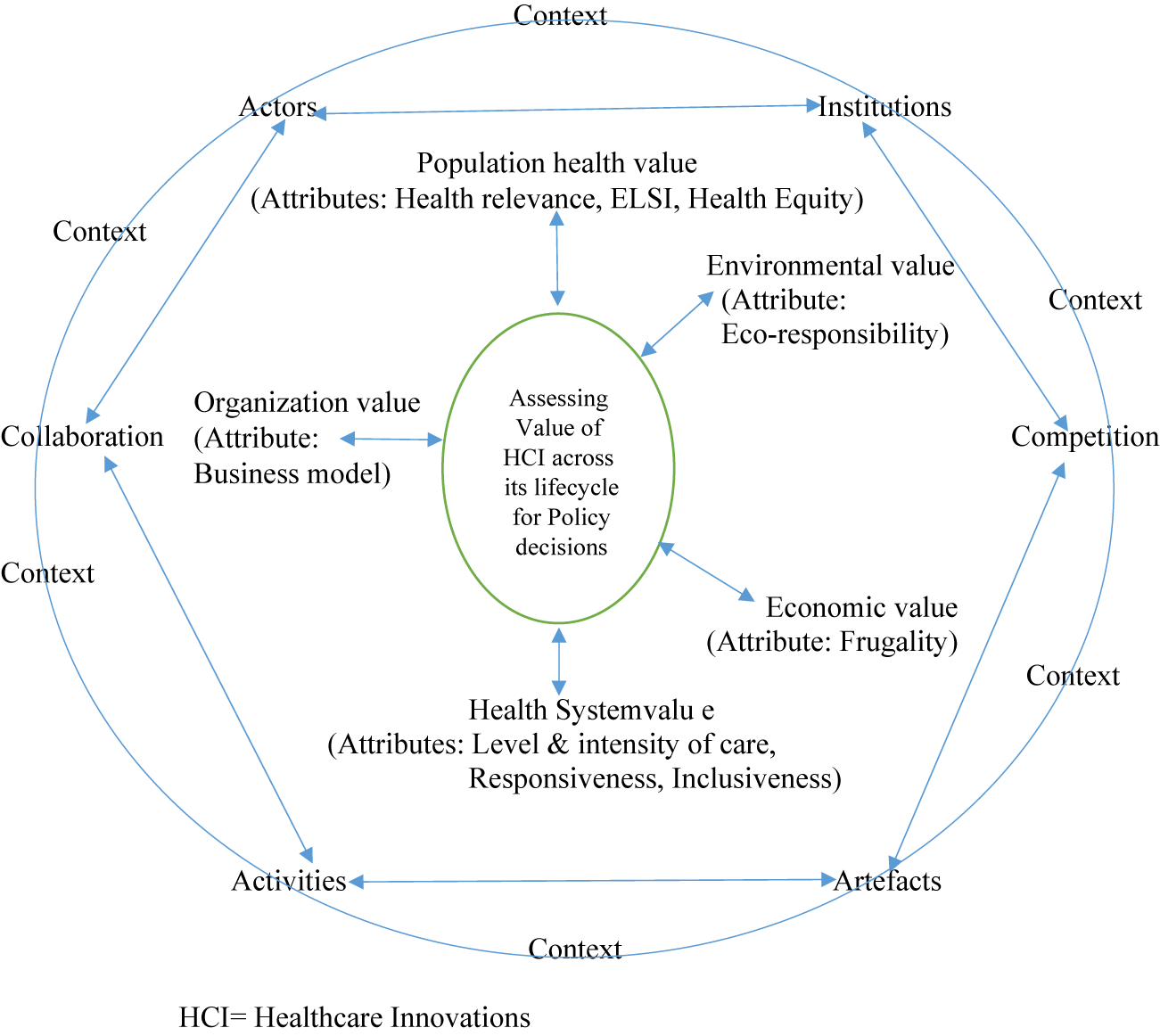

Healthcare innovations happen in an innovative space, which can be considered an ecosystem. An innovation ecosystem can be considered as an evolving phenomenon of interaction of actors (public, private, academia, civil society, patient groups, and so on), activities and artifacts (technology products and services) with institutions and relations (collaboration and competition) important for innovative performance (Reference Granstrand and Holgersson21). A practical application of this innovation ecosystem at the global level was observed during the development of COVID-19 diagnostics and vaccines in the form of Access to COVID-19 tools accelerator of the WHO and the solidarity trials for COVID-19 treatments, serologic studies, and vaccines (22;23). These have demonstrated the importance of working collaboratively with all stakeholders in this ecosystem to make health innovations available and accessible. Using this ecosystems framework and adapting the RIH value attributes with the normative principles of HTA emerging from its new definition, we discuss the potential of an integrated application of these two scientific mechanisms to determine the value of healthcare innovations, which is conceptualized in Figure 1. The proposed integrated model is based on the process-oriented principles of RRI (Reference Lubberink, Vincent, Johan van and Onno24), which includes anticipation of the risks and opportunities of innovation; reflexivity toward the value systems (including health system values) and social practices; inclusion of stakeholders in an evidence informed deliberative process (Reference Oortwijn and Klein25); and responsiveness to unforeseen consequences that may occur along innovation trajectories and ecosystems. In HTA, the above principles are more commonly applied downstream in the health innovation lifecycle. Incorporating the RIH perspective would help address the upstream factors that affect the innovation purpose, emergence, function, and costs through early HTA and provide scope for necessary modifications before the health innovation enters the market (Reference Silva, Lefebvre, Oliveira and Lehoux14). The RIH assessment tool consists of nine attributes (health relevance, Ethical, Legal, and Social Issues(ELSIs), health inequalities, inclusiveness, responsiveness, level and intensity of care, frugality, business model, eco-responsibility), which are rarely considered together in current HTA practice (Reference Silva, Lefebvre, Oliveira and Lehoux14). Hence, while some of the questions in the RIH tool are answered by current HTA processes, others require refinement of methodologies or approaches, depending on the current state of functional HTA in a given country context. Below, we discuss the intersection of current HTA practice with the above nine attributes of the RIH tool and its scope for application.

Figure 1. Integrated ecosystems framework for assessing the value of healthcare innovation. HCI = Healthcare Innovations

The first attribute of health relevance is determining the issue’s importance to the local context and a demand-side need of the society to prevent it from being an exercise based on the supplier’s (technology producers) priority. Country/region-specific epidemiological data and health systems data available in global or local databases would be helpful to answer this question. Attributes two and three (ELSIs and equity) are closely linked, and HTA needs to prioritize these attributes in determining the value of health innovations especially in the context of the “new normal” emerging from this pandemic. The pandemic exposed voids in equity and ethics created by healthcare innovations like COVID-19 vaccines, which showed that although innovative technology can add value in terms of effectiveness, the same innovation can also contribute to inequity in society. For example, the current pricing of COVID-19 vaccine would require the low-income countries to increase their health expenditure by 30–60 percent over 1 year to vaccinate 70 percent of their population. The corresponding health expenditure increase for the high-income countries for achieving the same vaccination coverage would be only 0.8 percent (26). This has resulted in an inequitable vaccination coverage status, wherein over 70 percent of the population in high-income countries have received at least one dose of the vaccine, but only 15 percent of the population in low-income countries have received one vaccine dose (26). HTA has a vital role in addressing this challenge and shaping the future trajectory of equity in society. The use of ethical, equity frameworks, and methodological refinements capturing equity dimensions has been limited in HTA (Reference Mukherjee13), and there is scope to improve their application in the future. Further, factors influencing access may differ from those influencing use of health technology like vaccines. For example, although the USA had sufficient vaccine stocks to vaccinate its population against COVID-19, vaccine hesitancy was over 20 percent in the USA, in the first few weeks of the vaccine roll out (27), which adversely affected use of this health technology. Social experimental studies and qualitative studies provided critical insights on the role of factors influencing the uptake of vaccines by the population, which helped create appropriate interventions to decrease vaccine hesitancy (Reference Abu-Akel, Spitz and West28;Reference Aschwanden29). Hence, evidence on this attribute will be enriched by contextual analysis, evidence from social experiments, qualitative evidence, and mixed-methods design of HTA. The use of mixed-methods design in HTA is limited (Reference Mukherjee30), and incorporating evidence from the disciplines of social and behavioral sciences and other relevant allied disciplines will enrich the HTA process and enhance the value of the evidence generated to inform policy.

Early engagement of relevant stakeholders (inclusiveness attribute) is critical and is part of the core process-oriented principles of RRI described above to ensure ownership of the process and product of HTA (Reference Mukherjee30), which, in turn, will contribute to better acceptability of the innovation and facilitate its adoption and diffusion. The new definition of HTA has brought the focus explicitly on health system responsiveness, which is the fifth attribute in the RIH tool. However, the level and intensity of care (sixth attribute) is yet to be assessed in current formal HTA techniques. Also, as the new definition emphasizes, HTA should be a continuous process responsive to changing evidence and contexts. In addition to being dependent on the availability of resources and data, operationalizing this life cycle approach to responsive health technology will need to navigate through three challenging constructs in any given country context. These constructs would include the actor interface constructs involving government and industry at the policy level, the capacity constructs to generate and use this real-world data at the health systems level, and the socio-cultural construct of the population in terms of willingness to share data and data privacy issues at the community level. The methods to capture cost and effectiveness data are well established in HTA to provide evidence on value for money. This, combined with value for many, constitutes the RIH tool’s frugality (seventh attribute). Frugality has emerged as an important value in the context of COVID-19 (Reference Harris, Bhatti, Buckley and Sharma31) especially in resource-constrained settings. HTA can play an important role in guiding policy decisions in this attribute by assessing affordability, ease of use, and context-specific optimized performance of healthcare innovations. Regarding the eight attribute (business model), current HTA practices focus on the health innovation or technology or interventions (population based/hospital based) as the unit of analysis and not the organization producing the innovation. The RIH tool assesses the organizations propensity to be socially and ethically responsible in doing business. For example, the RIH tool (Reference Pacifico Silva, Lehoux and Hagemeister32) mentions that the corporate social irresponsibility exclusion criterion requires searching for legitimate public statements describing infringements in responsible corporate actions. For assessing this, one needs to refer to specific governmental agencies, regulatory bodies, or independent not-for-profit organizations that monitor human and labor rights, animal welfare, and environmental regulations. Whether HTA should include such a “business model” assessment along with innovation assessment within its scope of work and whether it would be pragmatically feasible given the tensions between different stakeholders in the HTA process needs further discussion. Technology and climate change are the two seismic shifts affecting the future of this planet (33), and by incorporating eco-responsibility (ninth attribute) in the assessment of innovative technologies, HTA has the potential to contribute toward eco-friendly technology in the future. Although attempts have been made to capture the impact of technology on the environment through HTA, it needs more methodological refinements (Reference Marsh, Ganz and Hsu34;Reference Polisena, De Angelis, Kaunelis and Gutierrez-Ibarluzea35).

Conclusions

Healthcare innovation is a complex phenomenon, and a holistic approach to innovation is the key to generating, adapting, diffusing, and sustaining such innovations as they are embedded in policy, institutional, and societal contexts. In this context, this article discusses the values and attributes of RIH and HTA through an integrated ecosystems model to determine the value of healthcare innovations. The integrated approach described the potential and scope for determining the value of health innovations through explicit methods and robust analysis in the emerging “new normal.” However, while leveraging this for policy traction, one needs to be sensitive to the country’s socio-political context. The application of HTA is limited, while RIH is relatively unexplored in the developing world. Hence, its acceptance in the global south would be dependent on engaging with local contexts, cultures, capacities, and practices. The applicability of this approach will also be limited by resources and capacities and availability of data and other attributes of interest. Conflicting priorities, power, and information asymmetry may limit the mutual responsiveness of stakeholder engagement and could affect the collaborative endeavor that this integrated approach stands for.

Given the above limitations, this integrated ecosystems approach is conceptualized as evolving and flexible, which can be adapted to local contexts based on resources, capacities, and data availability. Hence, it is recommended that future researchers help refine this approach and test its usefulness through empirical studies. Its application has the potential to generate evidence on the performance of process-product-organization configurations at an early stage of health innovation development and will be helpful for policymakers in decisions regarding research and development funding, adoption, diffusion, and scaling of healthcare innovations based on a whole of society approach.

Innovation policies, RIH, and HTA are challenging but essential since they are expected to address unforeseen events, processes, and products and have the potential to broaden our thinking, enhance community reflexivity, and ensure collective decision making for creating a sustainable future. Hence, innovation policies should be broader than merely identifying and contextualizing new technologies. They should be more democratic and inclusive and discussing the kind of society we want for the future and hence provide scope for democratizing the future in the making. This proposed integrated approach of RIH attributes with existing HTA practices provides an opportunity for HTA to be transdisciplinary in nature, not just to provide a report card on the value of health innovation but as a tool for providing evidence and guidance to stakeholders for co-creation of innovative health technologies toward creating sustainable and inclusive societies for the future.

Funding Statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.