One aspect of video game music that is both compelling and challenging is the question of how video game music should be studied. Game music is often sonically similar to classical music, popular musical styles and music in other media like film. Techniques from these other established fields of study can be applied to game music. Yet at the same time, game music exists as part of a medium with its own particular qualities. Indeed, many such aspects of games, including their interactivity, complicate assumptions that are normally made about how we study and analyse music.

Relationship with Film Music

Some scholars have examined game music by making fruitful comparisons with film music, noting the similarities and differences.Footnote 1 Neil Lerner has shown the similarities between musical techniques and materials of early cinema and those of early video game music like Donkey Kong (1981) and Super Mario Bros. (1985).Footnote 2 William Gibbons has further suggested that the transition of silent film to ‘talkies’ provides a useful lens for understanding how some video games like Grandia II (2000) and the Lunar (1992, 1996) games dealt with integrating voice into their soundtracks.Footnote 3 Such parallels recognized, we must be wary of suggesting that films and games can be treated identically, even when they seem most similar: Giles Hooper has considered the varieties of different kinds of cutscenes in games, and the complex role(s) that music plays in such sequences.Footnote 4

Film music scholars routinely differentiate between music that is part of the world of the characters (diegetic) and music that the characters cannot hear, like typically Hollywood orchestral underscore (non-diegetic). While discussing Resident Evil 4 (2005) and Guitar Hero (2005), Isabella van Elferen has described how games complicate film models of music and diegesis. Van Elferen notes that, even if we assume an avatar-character cannot hear non-diegetic music, the player can hear that music, which influences how their avatar-character acts.Footnote 5 These kinds of observations reveal how powerful and influential music is in the video game medium, perhaps even more so than in film. Further, the distinct genre of music games poses a particular challenge to approaches from other fields, and reveals the necessity of a more tailored approach.

Borrowing Art Music Techniques

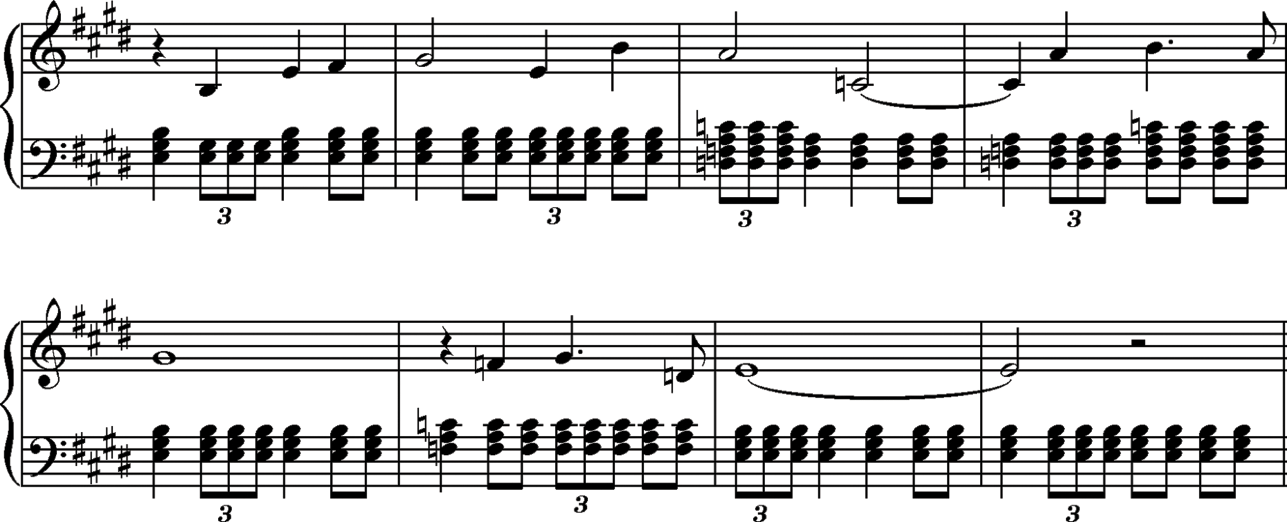

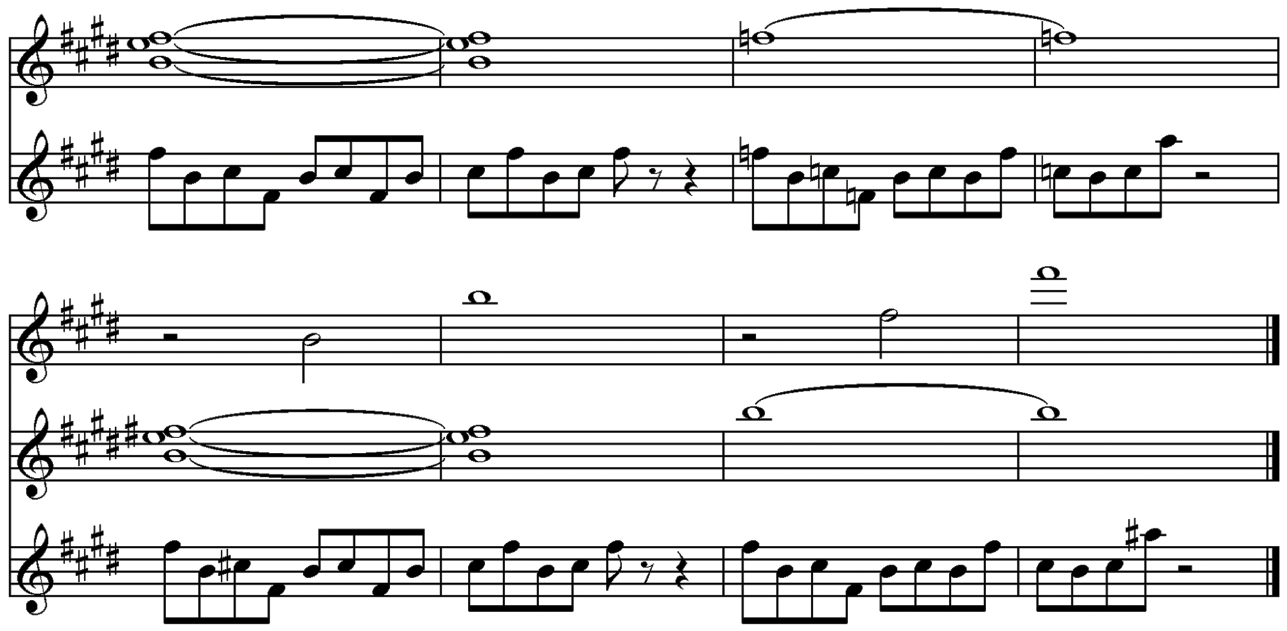

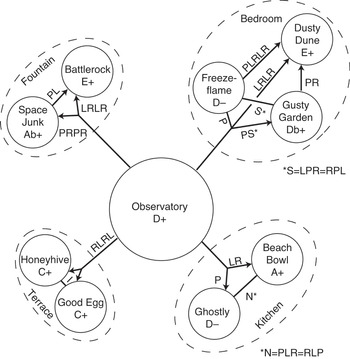

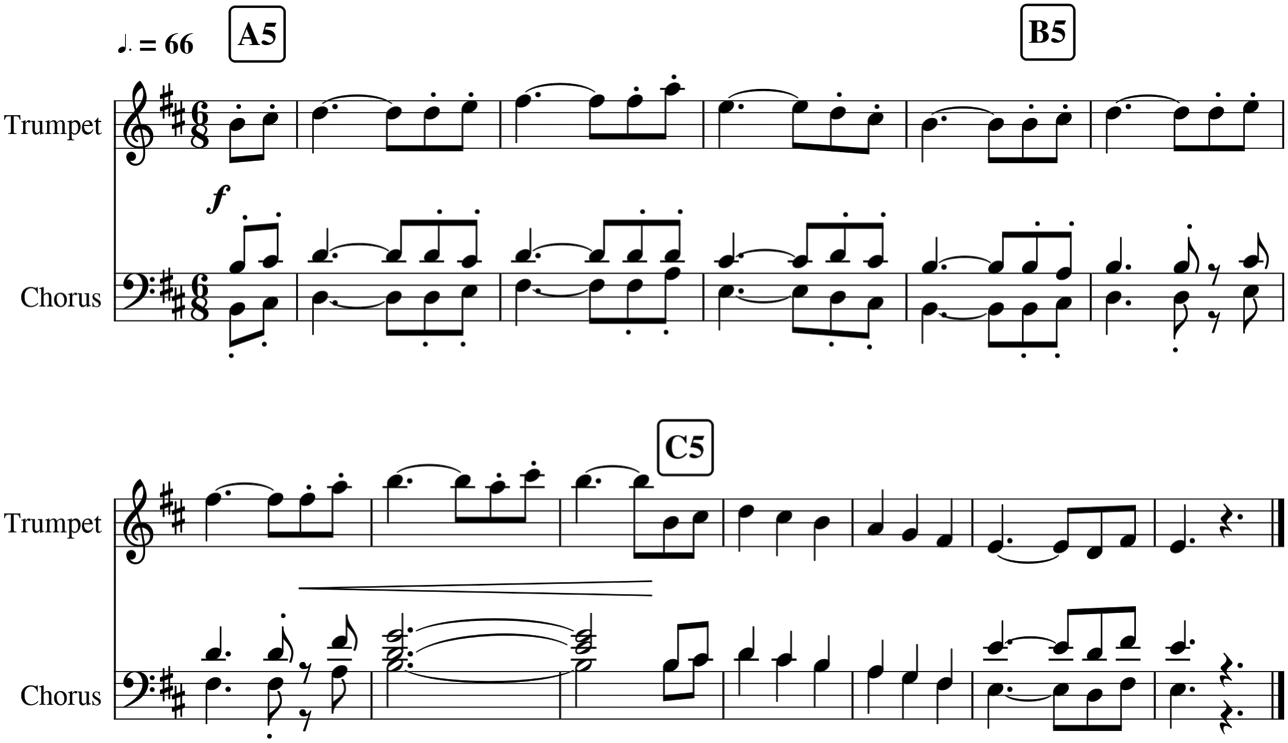

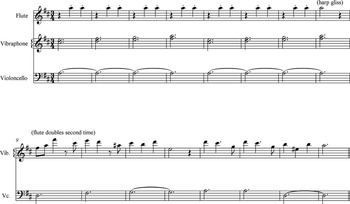

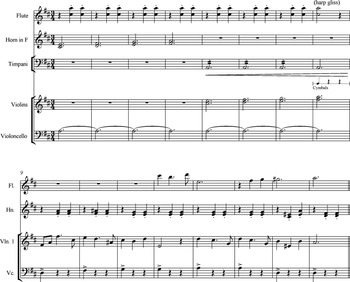

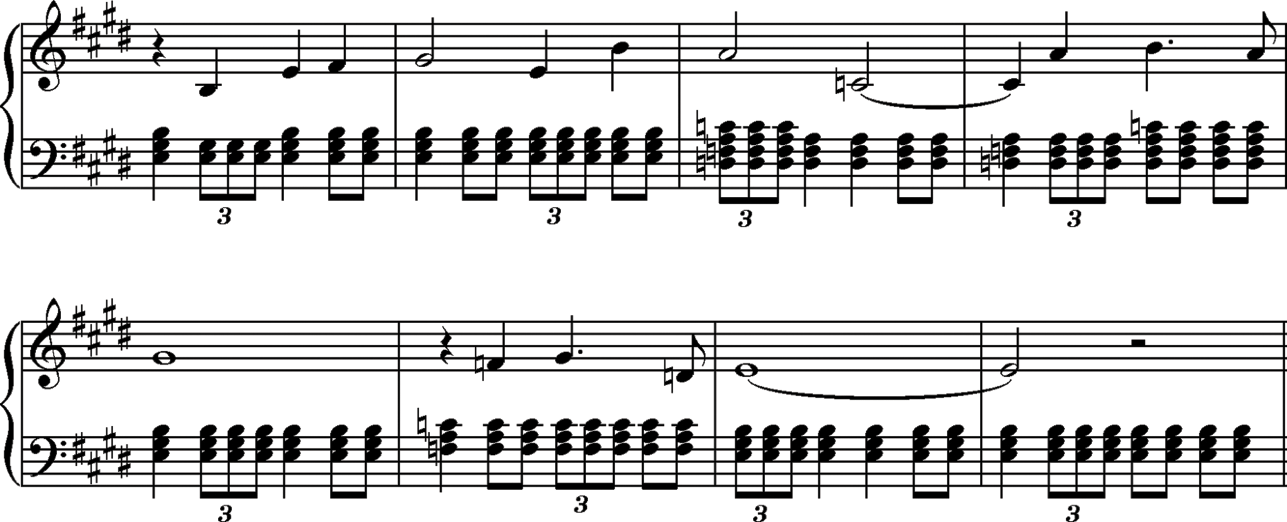

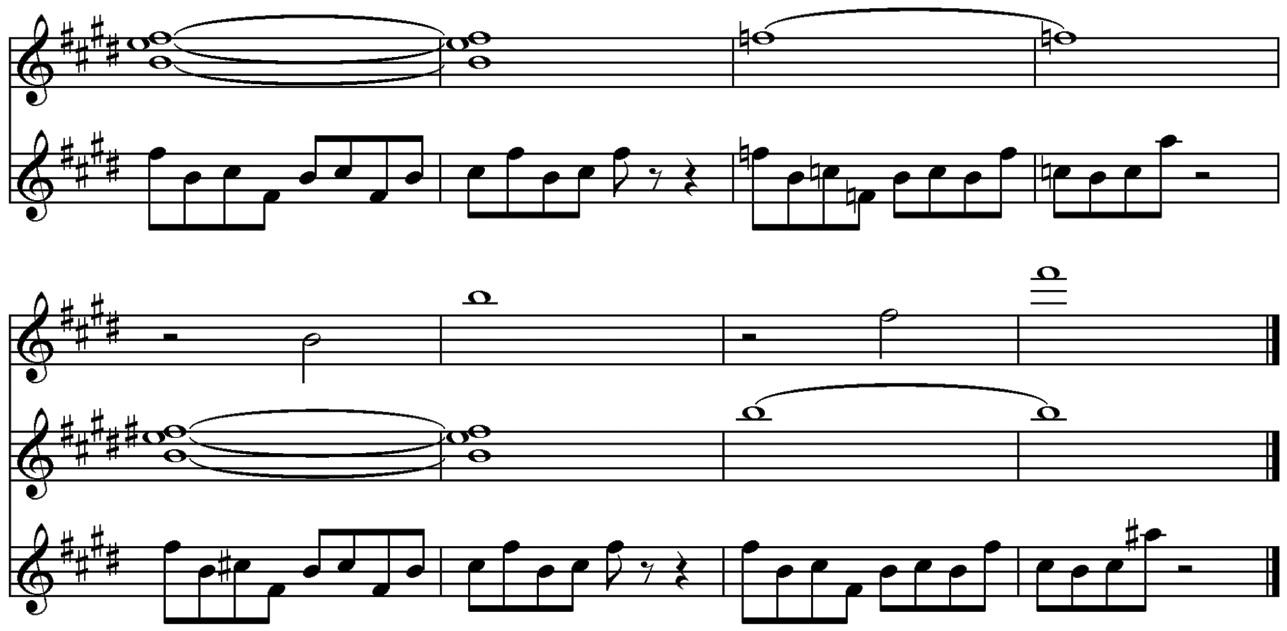

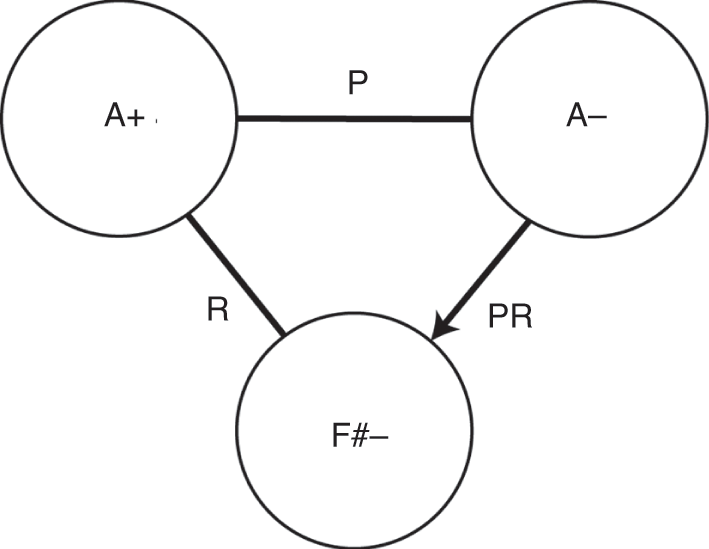

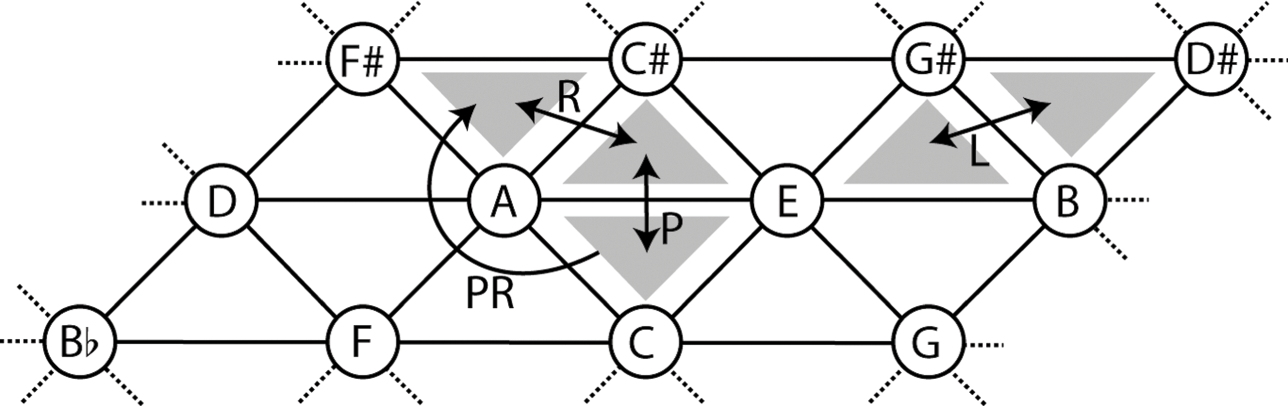

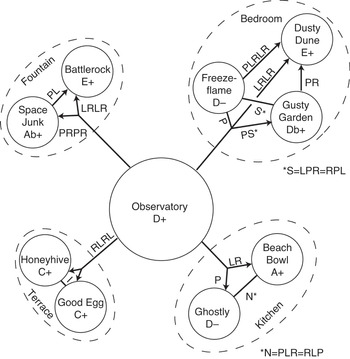

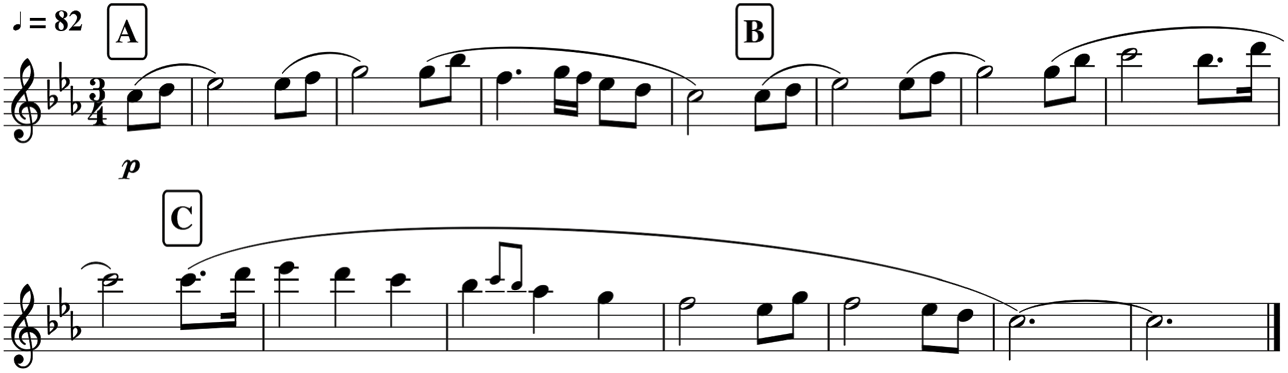

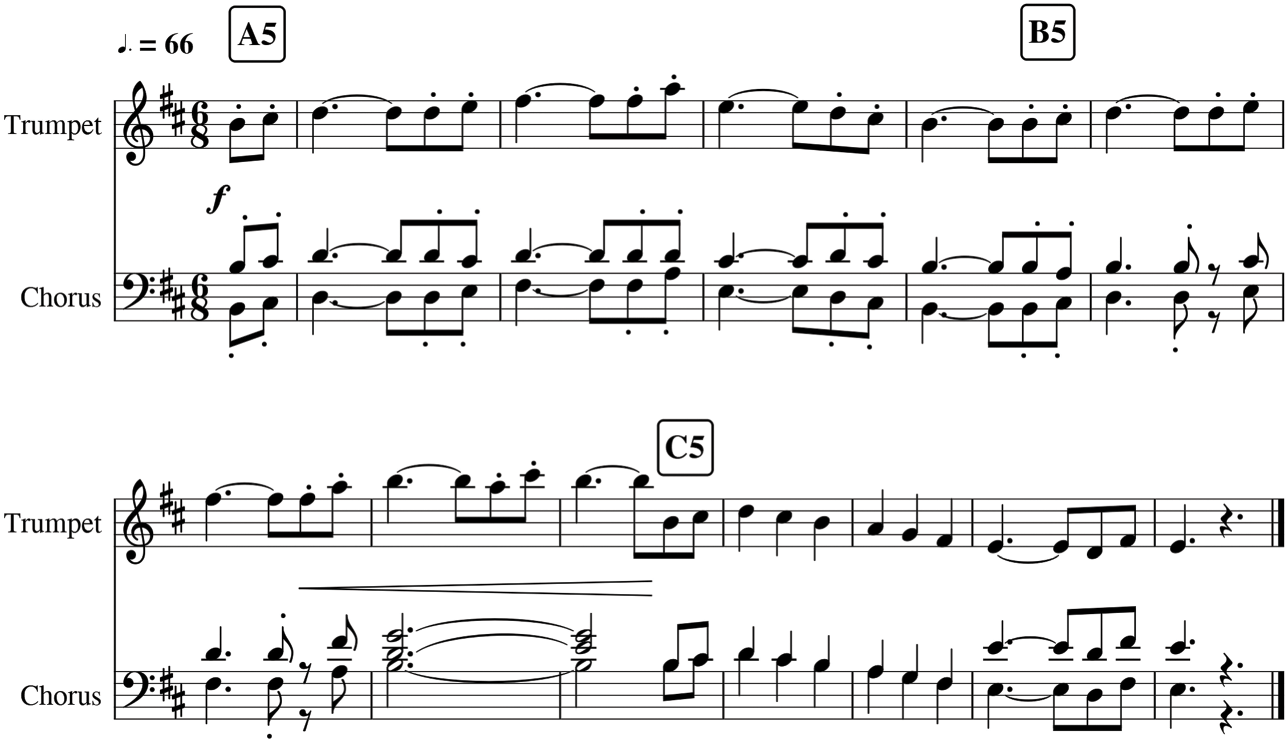

Just as thematic/motivic analysis has been useful in art music and film music studies, so it can reveal important insights in game music. Jason Brame analysed the recurrence of themes across Legend of Zelda games to show how the series creates connections and sense of familiarity in the various instalments,Footnote 6 while Guillaume Laroche and Andrew Schartmann have conducted extensive motivic and melodic analyses of the music of the Super Mario games.Footnote 7 Frank Lehman has applied Neo-Riemannian theory, a method of analysing harmonic movement, to the example of Portal 2 (2011).Footnote 8 Recently, topic theory – a way of considering the role of styles and types of musical materials – has been applied to games. Thomas Yee has used topic theory to investigate how games like Xenoblade Chronicles (2010) (amongst others) use religious and rock music for certain types of boss themes,Footnote 9 while Sean Atkinson has used a similar approach to reveal the musical approaches to flying sequences in Final Fantasy IV (1991) and The Legend of Zelda: Skyward Sword (2011).Footnote 10

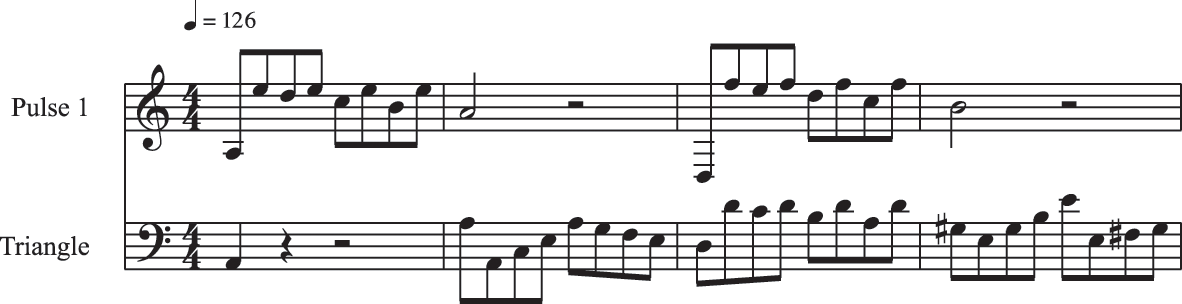

Peter Shultz has inverted such studies, and instead suggests that some video games themselves are a form of musical analysis.Footnote 11 He illustrates how Guitar Hero represents songs in gameplay, with varying degrees of simplification as the difficulty changes.

The Experience of Interactivity

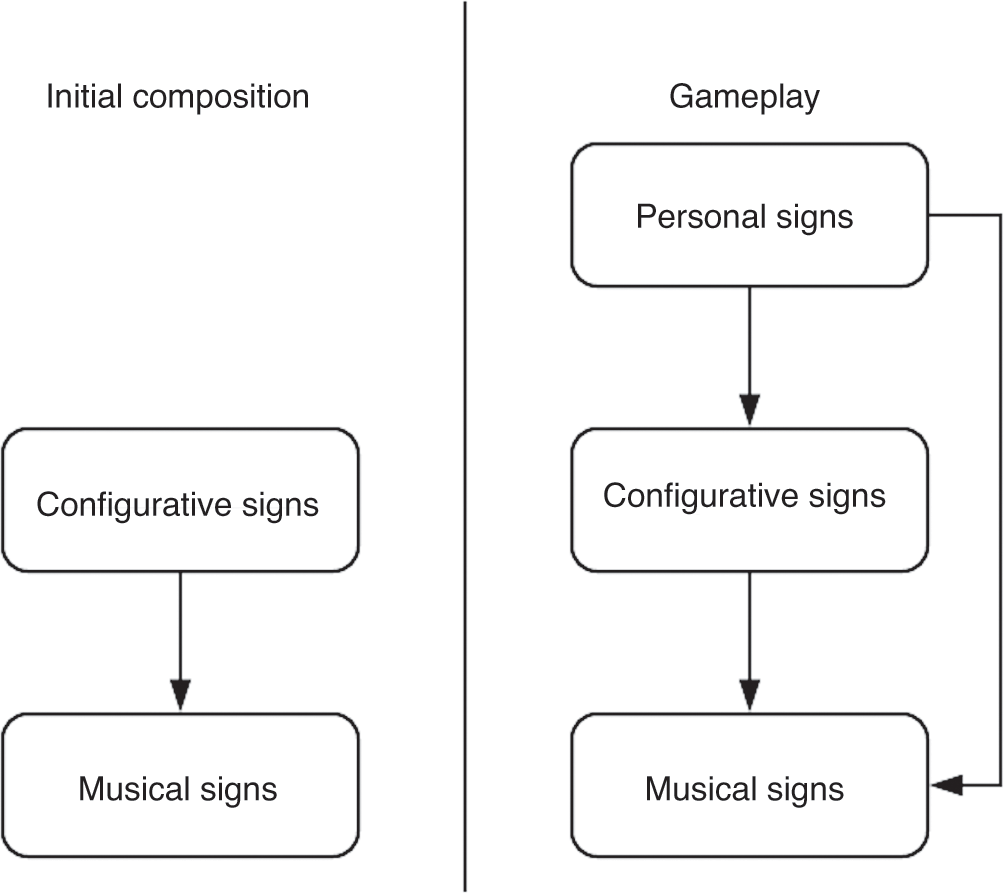

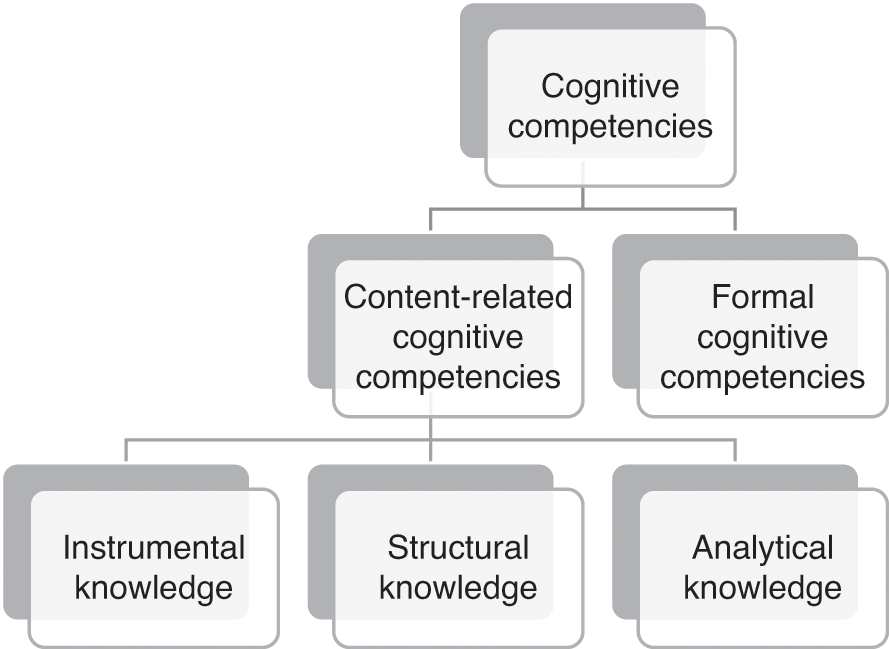

Musical analysis has traditionally been able to rely on the assumption that each time a particular piece of music is played, the musical events will occur in the same order and last for approximately the same duration. Though analysts have always been aware of issues such as optional repeats, different editions, substituted parts and varying performance practices, art music analysis has often tended to treat a piece of music as highly consistent between performances. The interactive nature of games, however, means that the music accompanying a particular section of a game can sound radically different from one play session to the next. The degree of variation depends on the music programming of the game, but the way that game music is prompted by, and responds to, player action asks us to reconsider how we understand our relationships with the music in an interactive setting.

Elizabeth Medina-Gray has advocated for a modular understanding of video game music. She writes,

modularity provides a fundamental basis for the dynamic music in video games. Real-time soundtracks usually arise from a collection of distinct musical modules stored in a game’s code – each module being anywhere from a fraction of a second to several minutes in length – that become triggered and modified during gameplay. … [M]usical modularity requires, first of all, a collection of modules and a set of rules that dictate how the modules may combine.Footnote 12

Medina-Gray’s approach allows us to examine how these musical modules interact with each other. This includes how simultaneously sounding materials fit together, like the background cues and performed music in The Legend of Zelda games.Footnote 13 Medina-Gray analyses the musical ‘seams’ between one module of music and another. By comparing the metre, timbre, pitch and volume of one cue and another, as well as the abruptness of the transition between the two, we can assess the ‘smoothness’ of the seams.Footnote 14 Games deploy smooth and disjunct musical seams to achieve a variety of different effects, just like musical presence and musical silence are meaningful to players (see, for example, William Gibbons’ exploration of the careful use of silence in Shadow of the Colossus (2005)).Footnote 15

Another approach to dealing with the indeterminacy of games has come from scholars who adapt techniques originally used to discuss real-world sonic environments. Just like we might analyse the sound world of a village, countryside or city, we can discuss the virtual sonic worlds of games.Footnote 16 These approaches have two distinct advantages: they account for player agency to move around the world, and they contextualize music within the other non-musical elements of the soundtrack.

The interactive nature of games has made scholars fascinated by the experiences of engaging with music in the context of the video game. William Cheng’s influential volume Sound Play draws on detailed interrogation of the author’s personal experience to illuminate modes of interacting with music in games.Footnote 17 The book deals with player agency and ethical and aesthetic engagement with music in games. His case studies include morality and music in Fallout 3 (2008), as well as how players exert a huge amount of interpretive effort when they engage with game music, such as in the case of the opera scene in Final Fantasy VI (1994). Small wonder that gamers should so frequently feel passionate about the music of games.

Michiel Kamp has described the experience of listening to video game music in a different way, by outlining what he calls ‘four ways of hearing video game music’. They are:

1. Semiotic, when music is heard as providing the player ‘with information about gameplay states or events’;

2. Ludic, when we pay attention to the music and play ‘to the music or along with the music, such as running to the beat, or following a crescendo up a mountain’;

3. Aesthetic, when ‘we stop whatever we are doing to attend to and reflect on the music, or on a situation accompanied by music’;

4. Background, which refers to when music ‘does not attract our attention, but still affects us somehow’.Footnote 18

Kamp emphasizes the multidimensional qualities of listening to music in games, and, by implication, the variety of ways of analysing it.

‘Music Games’

In games, we become listeners, creators and performers all at once, so we might ask, what kind of musical experiences do games afford? One of the most useful places to start answering this question is in the context of so-called ‘music games’ that foreground players’ interaction with music in one way or another.

Unsurprisingly, Guitar Hero and other music games have attracted much attention from musicians. It is obvious that playing instrument-performance games like Guitar Hero is not the same as playing the instrument in the traditional way, yet these games still represent important musical experiences. Kiri Miller has conducted extensive ethnographic research into Guitar Hero and Rock Band (2007). As well as revealing that these games appealed to gamers who also played a musical instrument, she reported that players ‘emphasized that their musical experiences with Guitar Hero and Rock Band feel as “real” as the other musical experiences in their lives’.Footnote 19 With work by Henry Svec, Dominic Arsenault and David Roesner,Footnote 20 the scholarly consensus is that, within the musical constraints and possibilities represented by the games, Guitar Hero and Rock Band emphasize the performative aspects of playing music, especially in rock culture, and opening up questions of music making as well as of the liveness of music.Footnote 21 As Miller puts it, the games ‘let players put the performance back into recorded music, reanimating it with their physical engagement and adrenaline’.Footnote 22 Most importantly, then, the games provide a new way to listen to, perform and engage with the music through the architecture of the games (not to mention the fan communities that surround them).

Beyond instrument-based games, a number of scholars have devised different methods of categorizing the kinds of musical interactivity afforded players. Martin Pichlmair and Fares Kayali outline common qualities of music games, including the simulation of synaesthesia and interaction with other elements in the game which affect the musical output.Footnote 23 Anahid Kassabian and Freya Jarman emphasize musical choices and the different kinds of play in music games (from goal-based structures to creative free play).Footnote 24 Melanie Fritsch has discussed different approaches to world-building through the active engagement of players with music in several ways,Footnote 25 as well as the adoption of a musician’s ‘musical persona’Footnote 26 for game design by analysing games, turning on Michael Jackson as a case study.Footnote 27

Opportunities to perform music in games are not limited to those specifically dedicated to music; see, for example, Stephanie Lind’s discussion of The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (1998).Footnote 28 William Cheng and Mark Sweeney have described how musical communities have formed in multiplayer online games like Lord of the Rings Online (2007) and Star Wars: Galaxies (2003).Footnote 29 In the case of Lord of the Rings Online, players have the opportunity to perform on a musical instrument, which has given rise to bands and even in-game virtual musical festivals like Weatherstock, where players from across the world gather together to perform and listen to each other. These festivals are social and aesthetic experiences. These communities also exist in tandem with online fan culture beyond the boundary of the game (of which more elsewhere in the book; see Chapter 23 by Ryan Thompson).

Play Beyond Music Games

Music is important to many games that are not explicitly ‘music games’. It is indicative of the significance of music in the medium of the video game that the boundaries of the ‘music game’ genre are ambiguous. For instance, Steven Reale provocatively asks whether the crime thriller game L.A. Noire (2011) is a music game. He writes,

Guitar-shaped peripherals are not required for a game’s music to be intractable from its gameplay … the interaction of the game world with its audio invites the possibility that playing the game is playing its music.Footnote 30

If games respond to action with musical material, the levels of games can become like musical scores which are performed by the gamer when they play. We may even begin to hear the game in terms of its music.

Reale’s comments echo a broader theme in game music studies: the role of play and playfulness as an important connection between playing games and playing music. Perhaps the most famous advocate for this perspective is Roger Moseley, who writes that

Like a Mario game, the playing of a Mozart concerto primarily involves interactive digital input: in prompting both linear and looping motions through time and space, it responds to imaginative engagement … [It makes] stringent yet negotiable demands of performers while affording them ample opportunity to display their virtuosity and ingenuity.Footnote 31

Moseley argues that ‘Music and the techniques that shape it simultaneously trace and are traced by the materials, technologies and metaphors of play.’Footnote 32 In games, musical play and game play are fused, through the player’s interaction with both. In doing so, game music emphasizes the fun, playful aspects of music in human activity more generally. That, then, is part of the significance of video game music – not only is it important for gaming and its associated contexts, but video games reveal the all-too-often-ignored playful qualities of music.

Of course, there is no single way that video game music should be analysed. Rather, a huge variety of approaches are open to anyone seeking to investigate game music in depth. This section of the Companion presents several different methods and perspectives on understanding game music.

Within the field of game studies, much ink has been spilt in the quest to define and classify games based on their genre, that is, to determine in which category they belong based on the type of interaction each game affords. Some games lie clearly within an established genre; for example, it is rather difficult to mistake a racing game for a first-person shooter. Other games, however, can fall outside the boundaries of any particular genre, or lie within the perimeters of several genres at once. Such is the case with music games. While some may argue that a game can be considered to be a music game only if its formal elements, such as theme, mechanics or objectives, centre on music, musicians, music making or another music-related activity, in practice the defining characteristics of a music game are much less clear – or rather, are much broader – than with other genres. Many game publishers, players, scholars and critics classify a game as musical simply because it features a particular genre of music in its soundtrack or musicians make appearances as playable characters, despite the fact that little-to-no musical activity is taking place within the game.

In this chapter, I outline a number of types of music games. I also discuss the various physical interfaces and controllers that facilitate musical interaction within games, and briefly highlight a number of cultural issues related to music video games. As a conclusion, I will suggest a model for categorizing music games based on the kind of musical engagement they provide.

Music Game (Sub)Genres

Rhythm Games

Rhythm games, or rhythm action games, are titles in which the core game mechanics require players to match their actions to a given rhythm or musical beat. The ways in which players interact with the game can vary widely, ranging from manually ‘playing’ the rhythm with an instrument-shaped controller, to dancing, to moving an in-game character to the beat of a game’s overworld music. Although proto-rhythm games have existed in some form since the 1970s, such as the handheld game Simon (1978), the genre became very successful in Japan during the late 1990s and early 2000s with titles such as Beatmania (1997), Dance Dance Revolution (1998) and Taiko no Tatsujin (2001). With Guitar Hero (2005), the genre came to the West and had its first worldwide smash hit. Guitar Hero achieved enormous commercial success in the mid-2000s before waning in popularity in the 2010s.Footnote 1

Peripheral-based Rhythm Games

Perhaps the most well-known of all types of rhythm games, peripheral-based rhythm games, are those in which the primary interactive mechanics rely on a physical controller (called peripheral because it is usually an extra, external component used to control the game console). While peripheral controllers can take any number of shapes, those that control rhythm games are often shaped like guitars, drums, microphones, turntables or other musical instruments or equipment.

Quest for Fame (1995) was one of the first music games to utilize a strum-able peripheral controller – a plastic wedge called a ‘VPick’. After connecting its cord into the second PlayStation controller port, players held the VPick like a guitar pick, strumming anything they had available – a tennis racket, their own thigh, and so on – like they would a guitar. The actions would be registered as electrical impulses that registered as soundwaves within the game. Players would progress through the game’s various levels depending on their success in matching their soundwaves with the soundwaves of the in-game band.

Games in the Guitar Hero and Rock Band series are almost certainly the most well-known peripheral-based rhythm games (and arguably the most well-known music video games). Guitar Hero features a guitar-shaped peripheral controller with coloured buttons along its fretboard. As coloured gems that correspond to the buttons on the controller (and ostensibly to notes in the song being performed) scroll down the screen, players must press the matching coloured buttons in time to the music. The original Rock Band (2007) combined a number of various plastic instrument controllers, such as a guitar, drum kit and microphone, to form a complete virtual band. Titles in the Guitar Hero and Rock Band series also allow players to play a wide variety of songs and genres of music through a large number of available expansion packs.

Non-Peripheral Rhythm Games

PaRappa the Rapper (1996), considered by many to be one of the first popular music games, was a rhythm game that used the PlayStation controller to accomplish the rhythm-matching tasks set forth in the game, rather than a specialized peripheral controller.Footnote 2 In-game characters would teach PaRappa, a rapping dog, how to rap, providing him with lyrics and corresponding PlayStation controller buttons. Players were judged on their ability to press the correct controller button in rhythm to the rap. Similar non-peripheral rhythm games include Vib-Ribbon (1999).

Other rhythm games aim for a middle ground between peripheral and non-peripheral rhythm games. These rely on players using physical gestures to respond to the musical rhythm. Games in this category include Wii Music (2008), which uses the Wii’s motion controls so that players’ movements are synchronized with the musical materials. Rhythm Heaven/Rhythm Paradise (2008) was released for the Nintendo DS, and to play the game’s fifty rhythm mini-games, players held the DS like a book, tapping the touch screen with their thumbs or using the stylus to tap, flick or drag objects on the screen to the game’s music.

Dance-based Rhythm Games

Dance-based rhythm games can also be subdivided into two categories. Corporeal dance-based rhythm games require players to use their bodies to dance, either by using dance pads on the floor, or dancing in the presence of sensors. Manual dance games achieve the required beat-matching through button-mashing that is synchronized with the dance moves of on-screen avatars using a traditional controller in the player’s hands. These manual dance games include titles such as Spice World (1998) and Space Channel 5 (1999).

Corporeal dance games were amongst the first rhythm games. Dance Aerobics (1987), called Aerobics Studio in Japan, utilized the Nintendo Entertainment System’s Power Pad controller, a plastic floor-mat controller activated when players stepped on red and blue circles, triggering the sensors imbedded inside. Players matched the motion of the 8-bit instructor, losing points for every misstep or rhythmic mistake. As players advanced through each class, the difficulty of matching the rhythmic movements of the instructor also increased. The ‘Pad Antics Mode’ of Dance Aerobics included a free-form musical mode called ‘Tune Up’ in which players could use the NES Power Pad to compose a melody, with each of the ten spots on the periphery of the Power Pad assigned a diatonic pitch; in ‘Mat Melodies’, players used these same spots to play tunes such as ‘Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star’ with their feet while following notes that appeared on a musical staff at the top of the screen. ‘Ditto’ mode featured a musical memory game similar to Simon.

Games in Konami’s Bemani series include many of the best known in the rhythm games genre. The term ‘Bemani’ originated as a portmanteau in broken English of Konami’s first rhythm game, Beatmania, and it stuck as a nickname for all music games produced by the publisher; the company even adopted the nickname as a brand name, replacing what was previously known as the Games & Music Division (GMD). Dance Dance Revolution, or DDR quickly became one of the most well-known games in this dance-based rhythm game genre. Usually located in public arcades, these games became spectacles as crowds would gather to watch players dance to match the speed and accuracy required to succeed within the game. DDR players stand on a special 3 x 3 square platform controller which features four buttons, each with arrows pointing forward, back, left or right. As arrows scroll upward from the bottom of the screen and pass over a stationary set of ‘guide arrows’, players must step on the corresponding arrow on the platform in rhythm with the game, and in doing so, they essentially dance to the music of the game.Footnote 3

Although the first dance-based games required players to match dance steps alone, without regard to what they did with the rest of their body, motion-based games required players to involve their entire body. For instance, Just Dance (2009) is a dance-based rhythm game for the motion-controlled Wii console that requires players to match the full-body choreography that accompanies each song on the game’s track list. As of the writing of this chapter in 2020, games were still being published in this incredibly popular series. When Dance Central (2010) was released for Microsoft Kinect, players of dance games were finally rid of the need to hold any controllers or to dance on a mat or pad controller; rather than simply stepping in a certain place at a certain time, or waving a controller in the air to the music, players were actually asked to dance, as the console’s motion-tracking sensors were able to detect the players’ motion and choreography, assessing their ability to match the positions of on-screen dancing avatars.Footnote 4

Musical Rail-Shooter Games

Rail-shooter games are those in which a player moves on a fixed path (which could literally be the rail of a train or rollercoaster) and cannot control the path of the in-game character/avatar or vehicle throughout the course of the level. From this path, the player is required to perform specific tasks, usually to shoot enemies while speeding towards the finish line. In musical rail-shooters, a player scores points or proves to be more successful in completing the level if they shoot enemies or execute other tasks in rhythm with music. Amongst the first of this type of game was Frequency (2001), which asked players to slide along an octagonal track, hitting controller buttons in rhythm in order to activate gems that represented small chunks of music. Other musical rail-shooters include Rez (2001), Amplitude (2003) and Audiosurf (2008).

Sampling/Sequencing and Sandbox Games

Some music games provide players with the ability to create music of their own. These games often began as music notation software or sequencing software programmes that were first marketed as toys, rather than serious music-creation software, such as Will Harvey’s Music Construction Set (1984), C.P.U. Bach (1994) and Music (1998). Otocky (1987) was designed as a music-themed side-scrolling shoot-’em-up in which players were able to fire their weapon in eight directions. Shots fired in each direction produced a different note, allowing players a small bit of freedom to compose music depending upon in which direction they shot. Mario Paint (1992) included an in-game tool that allowed players to compose music to accompany the artistic works they created within the game; this tool became so popular, it spurred on an online culture and spin-off software called Mario Paint Composer (Unfungames.com, 1992).Footnote 5

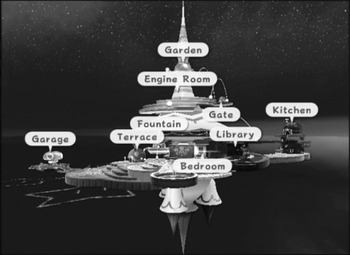

Electroplankton (2005) was released for the Nintendo DS console and designed as a sequencing tool/game in which players interacted with ten species of plankton (represented as various shapes) through the use of the DS’s microphone, stylus and touchscreen in the game’s ‘Performance Mode’. The species of a plankton indicated the action it performed in the game and the sound it produced. In ‘Audience Mode’, players could simply listen to music from the game. Despite its popularity, Electroplankton was not a successful music-creating platform due to its lack of a ‘save’ feature, which would have allowed players to keep a record of the music they created and share it.

KORG DS-10 (2008) was a fully fledged KORG synthesizer emulator designed to function like a physical synth in KORG’s MS range, and was created for use on the Nintendo DS platform. Other iterations, such as KORG DS-10 Plus (2009) and KORG iDS-10 (2015) were released for the Nintendo DSi and the iPhone, respectively. While it was released as synth emulator, KORG DS-10 received positive reviews by game critics because it inspired playful exploration and music creation.Footnote 6

Karaoke Music Games

Music games can also test a player’s ability to perform using musical parameters beyond rhythm alone. Games such as Karaoke Revolution (2003) and others in the series, as well as those in the SingStar series (2004–2017) have similar game mechanics to rhythm games, but rather than requiring players to match a steady beat, these games require players to match pitch with their voices.

Def Jam Rapstar (2010), perhaps the most critically acclaimed hip-hop-themed karaoke game, included a microphone controller in which players would rap along to a popular track’s music video (or a graphic visualization when no video was available), matching the words and rhythms of the original song’s lyrics; in instances where singing was required, a player’s ability to match pitch was also graded.

Mnemonic Music Games and Musical Puzzle Games

Many video games in this subgenre of music games have their roots in pre-digital games, and they rely on a player’s ability to memorize a sequence of pitches or to recall information from their personal experience with music. Simon, considered by many to be the first electronic music game, tested a player’s ability to recall a progressively complex sequence of tones and blinking lights by recreating the pattern using coloured buttons. Later games, such as Loom (1990) and The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (1998) relied, at least in part, on a similar game mechanic in which players needed to recall musical patterns in gameplay.

A variation on the ‘name that tune’ subgenre, Musika (2007) tapped into the library of song files players had loaded onto their iPod Touch. As they listen, players must quickly decide whether or not the letter slowly being uncovered on their screen appears in the title of that particular song. The faster they decide, the higher a player’s potential score. SongPop (2012) affords players the chance to challenge one another to a race in naming the title or performer of popular tunes, albeit asynchronously, from a multiple-choice list.

Musician Video Games

The subgenre of what we might term ‘musician video games’ are those in which musicians (usually well-known musicians that perform in popular genres) or music industry insiders become heavily involved in the creation of a video game as a vehicle to promote themselves and their work beyond the video game itself. Games might even serve as the means of distribution for their music. Musicians or bands featured in a game may go on music-themed quests, perform at in-game concerts or do a myriad number of other things that have nothing at all to do with music. A wide variety of musicians are featured in this type of game, which include Journey (1983), Frankie Goes to Hollywood (1985), Michael Jackson’s Moonwalker (1990), Peter Gabriel: EVE (1996) and Devo Presents Adventures of the Smart Patrol (1996).

Music Industry Games

In much the same way many musician video games allowed players to live the life of a rock star through an avatar, music industry-themed games put players in charge of musical empires, gamifying real-world, industry-related issues and tasks, such as budgets, publicity and promotion, and music video production. Games in this genre include Rock Star Ate My Hamster (1988), Make My Video (1992), Power Factory Featuring C+C Music Factory (1992), Virtual VCR: The Colors of Modern Rock (1992), Rock Manager (2001), Recordshop Tycoon (2010) and TastemakerX (2011).

Edutainment Music Games and Musical Gamification

Educators and video game publishers have long been keen on using video games as both a source of entertainment and as a potential tool for teaching various subjects, including music. Early edutainment games, such as Miracle Piano Teaching System (1990), sought to make learning music fun by incorporating video-game-style gameplay on a video game console or personal computer. Such endeavours must deal with the issue of how to incorporate instruments into the learning process. Some opt for MIDI interfaces (like Miracle Piano), while others use replica instruments. Power Gig: Rise of the SixString (2010) included an instrument very similar to an authentic guitar. This peripheral controller was designed to help teach players how to play an actual guitar, although it was 2/3 the size of a standard guitar and of poor quality, and besides teaching players various simplified power chords, the game really did not teach players how to play the guitar, instead simply mimicking the mechanics of Guitar Hero and other similar games. Power Gig also included a set of sensors that monitored the action of players who were air-drumming along with songs in the game. The game that has arguably come the closest to teaching game players to become actual instrument players is Ubisoft’s Rocksmith (2011) and its sequels, which allowed players to plug in an actual electric guitar of their own (or acoustic guitar with a pickup), via a USB-to-1/4 inch TRS cable, into their Xbox 360 console to be used as a game controller. The game’s mechanics are similar to those of other guitar-themed rhythm games: players place their fingers in particular locations on a fretboard to match pitch and strum in rhythm when notes are supposed to occur, rather than mashing one of four coloured buttons as in Guitar Hero-style rhythm games. Similarly, and taking the concept a step further, BandFuse: Rock Legends (2013) allows up to four players to plug in real electric guitars, bass guitars and microphones as a means of interacting with the video game by playing real music. In fact, the ‘legends’ referenced in the game’s title are rock legends who, with the aid of other virtual instructors, teach players how to play their hit songs through interactive video lessons in the game’s ‘Practice’ and ‘Shred-U’ modes.

Music Game Technology

Peripheral Controllers

Music games can frequently rely on specialized controllers or other accessories to give players the sense that they are actually making music. As previously discussed, these controllers are called ‘peripheral’ because they are often additional controllers used to provide input for a particular music game, not the standard controllers with which most other games are played. While some peripheral controllers look and react much like real, functioning instruments and give players the haptic sensation of playing an actual instrument, others rely on standard console controllers or other forms of player input.

Guitars

Games such as those in the Guitar Hero and Rock Band series rely on now-iconic guitar-shaped controllers to help players simulate the strumming and fretwork of a real guitar during gameplay. While pressing coloured buttons on the fretboard that correspond to notes appearing on the screen, players must flick a strum bar (button) as the notes pass through the cursor or target area. Some guitar controllers also feature whammy bars for pitch bends, additional effect switches and buttons and additional fret buttons or pads. These controllers can often resemble popular models of electric guitars, as with the standard guitar controller for Guitar Hero, which resembles a Gibson SG.

Drums and Other Percussion

Taiko: Drum Master (2004), known as Taiko no Tatsujin in Japan, is an arcade game that features two Japanese Taiko drums mounted to the console, allowing for a two-player mode; the home version employs the Taiko Tapping Controller, or ‘TaTaCon’, which is a small mounted drum with two bachi (i.e., the sticks used to play a taiko drum). Games in the Donkey Konga series (2003–2005) and Donkey Kong Jungle Beat (2004) require a peripheral set of bongo drums, called DK Bongos, to play on the GameCube console for which the games were created. Samba de Amigo (1999) is an arcade game, later developed for the Dreamcast console, played with a pair of peripheral controllers fashioned after maracas. Players shake the maracas at various heights to the beat of the music, positioning their maracas as indicated by coloured dots on the screen.

Turntables

Some hip-hop-themed music games based on turntablism, such as DJ Hero (2009), use turntable peripheral controllers to simulate the actions of a disc jockey. These controllers usually include moveable turntables, crossfaders and additional buttons that control various parameters within the game.

Microphones

Karaoke music games usually require a microphone peripheral in order to play them, and these controllers are notorious for their incompatibility with other games or consoles. Games such as Karaoke Revolution initially included headset microphones, but later editions featured handheld models. LIPS (2008) featured a glowing microphone with light that pulsed to the music.

Mats, Pads and Platforms

These controllers are flat mats or pads, usually placed on the ground, and in most cases, players use their feet to activate various buttons embedded in the mat. Now somewhat standardized, these mats are customarily found as 3 x 3 square grids with directional arrows printed on each square. As was previously mentioned, players use the NES Power Pad to play Dance Aerobics; this controller is a soft pad made of vinyl or plastic that can easily be rolled up and stored. Arcade music games like Dance Dance Revolution use hard pads, often accompanied by a rail behind the player to give them something to grab for stability during especially difficult dance moves and to prevent them from falling over. Some of these games now use solid-state pads that utilize a proximity sensor to detect a player’s movement, rather than relying on the pressure of the player’s step to activate the controller. DropMix (2017) is a music-mixing game which combines the use of a tabletop game plastic platform, cards with embedded microchips and a companion smartphone application to allow players to create mashups of popular songs. Using near-field communication and a smartphone’s Bluetooth capabilities, players lay the cards on particular spots on the game’s platform. Each card is colour-coded to represent a particular musical element, such as a vocal or drum track, and depending upon its power level, it will mix in or overtake the current mix playing from the smartphone. Players can also share their mixes on social media through the app.

Motion Controls

Taiko Drum Master: Drum ‘n’ Fun (2018) was released for Nintendo Switch and relies on the player using the console’s motion controls. Taking a controller in each hand, the player swings the handheld controllers downwards for red notes and diagonally for the blue notes that scroll across the screen. In Fantasia: Music Evolved (2014), based on the ‘Sorcerer’s Apprentice’ section of the film Fantasia (1940), players act as virtual conductors, moving their arms to trace arrows in time with music to accomplish goals within the game. These motions are registered by the Xbox Kinect’s motion sensors, allowing players to move freely without needing to touch a physical controller.

Wii Nunchuks

Using the Wii’s nunchuk controllers, players of Wii Music (2008) could cordlessly conduct an orchestra or play a number of musical instruments. Likewise, players of Ultimate Band (2008) played notes on a virtual guitar by pressing various combinations of buttons on the Wii nunchuk while strumming up and down with the Wii remote.

Smartphone or Portable Listening Device Touchscreens

Some games mimic the mechanics of a peripheral-based rhythm game, but without the need for the instrument controller. Phase: Your Music Is the Game (2007) is a touchscreen-based rhythm game for the Apple iPod Touch; using the music found on the iPod in the player’s song library as the playable soundtrack, players tap the iPod’s touchscreen, rather than colour-coded buttons on a plastic guitar. Likewise, Tap Tap Revenge (2008) also utilized the iPhone’s touchscreen to simulate controller-based rhythm games such as Guitar Hero.

Wider Culture and Music Games

When popular music is included within a music game, copyright and licensing can often be the source of controversy and fodder for lawsuits. In its early days, players of Def Jam Rapstar were able to record videos of themselves performing the hip-hop songs featured in the game using their consoles or computers, and could upload these videos to an online community for recognition. In 2012, EMI and other rights holders brought up charges of copyright infringement, suing the game’s makers for sampling large portions of hip-hop songs for which they owned the rights.Footnote 7 Because the game was a karaoke-style music game and players could further distribute the copyrighted songs in question through the online community, EMI sought even more damages, and the online community was subsequently shut down.

At the height of their popularity, rhythm games such as Rock Band and Guitar Hero featured frequently in popular culture; for example, on Season 2, Episode 15 (2009) of the popular television show The Big Bang Theory, characters are shown playing the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ song ‘Under the Bridge’ on Rock Band. As these games gained popularity in their heyday, naysayers and musical purists insisted that these games had no inherent musical value since they did not seem to encourage anyone to actually play an instrument. As such, the games were often parodied in popular culture: the premise of the South Park episode ‘Guitar Queer-O’ (Season 11, Episode 3, 2007) revolves around the supposition that games such as Guitar Hero require no real musical skills. But these kinds of music games have also enjoyed a surge in popularity in educational arenas, and have been successfully put to instructive uses in classrooms, albeit not as a replacement for instrumental tuition.Footnote 8 There is some evidence to suggest that music games have actually inspired players to learn to play musical instruments outside of video games. In fact, seeing game characters play instruments in music games, such as the male protagonist Link who plays the ocarina in games in the Legend of Zelda series (Nintendo), has inspired male students to study the flute.Footnote 9 Also related to music, gender and performance, Kiri Miller writes in Playable Bodies that music games such as Dance Central also provide opportunities for players who chose to play as avatars that do not correspond with their own gender expression to engage in ‘generic, stylized gender performances that may pose little risk or challenge to their own identities’,Footnote 10 and in doing so, may denaturalize gender binaries.

Types of Music Games

As we have seen, the term ‘music games’ covers a wide spectrum of games and subgenres. To conclude this chapter, I wish to introduce a model for categorization. While this type of analysis will never provide a definitive classification of music games, it does present a framework within which analysts can discuss what types of musical activities or opportunities a game affords its players and what types of musical play might be occurring within the course of a player’s interaction with a game.

One useful way to describe music games is by asking whether, and to what extent, the player’s musical engagement through the game is procedural (interacting with musical materials and procedures) and/or conceptual (explicitly themed around music-making contexts). These two aspects form a pair of axes which allow us to describe the musical experiences of games. It also allows us to recognize musical-interactive qualities of games that do not announce themselves as explicitly ‘music games’.

Procedural and Conceptual Musical Aspects of Games

The procedural rhetoric of a music game denotes the rules, mechanics and objectives within a game – or beyond it – that encourage, facilitate or require musical activity or interaction. For example, in the rhythm game Guitar Hero, players must perform a musical activity in order to succeed in the game; in this case, a player must press coloured buttons on the game’s peripheral guitar-shaped controller in time with the music, and with the notes that are scrolling by on the screen. Other games, such as SongPop require players to select a themed playlist, listen to music and race an opponent to select the name of the song or the artist performing the song they are hearing. It should be noted that the term procedural is used here to describe the elements of a game that facilitate a particular means or process of interaction, which is different from procedural generation, or a method of game design in which algorithms are used to automatically create visual and sonic elements of a video game based on player action and interaction within a game.

Amongst procedural games, some are strictly procedural, in that they rely on clear objectives, fixed rules and/or right or wrong answers. One such category of strictly procedural music games is that of rhythm- or pitch-matching games. Players of strictly procedural music games score points based on the accuracy with which they can match pitch or rhythm, synchronize their actions to music within the game, or otherwise comply with the explicit or implicit musical rules of the game. Loosely procedural music games rely less on rigorous adherence to rules or correct answers but rather facilitate improvisation and free-form exploration of music, or bring to bear a player’s personal experience with the game’s featured music. Games such as Mario Paint Composer or My Singing Monsters (2012) function as sandbox-type music-making or music-mixing games that allow players more freedom to create music by combining pre-recorded sonic elements in inventive ways. Other loosely procedural games take the form of quiz, puzzle or memory games that rely on a player’s individual ability to recall musical material or match lyrics or recorded clips of songs to their titles (as is the case with the previously mentioned SongPop); even though the procedural rhetoric of these games requires players to accurately match music with information about it (that is to say, there is a right and a wrong answer), players bring their own memories and affective experiences to the game, and players without these experiences are likely much less successful when playing them.

Highly conceptual music games are those in which theme, genre, narrative, setting and other conceptual elements of the game are related to music or music making. Here, content and the context provide the musical materials for a music game. This contrasts with the ‘procedural’ axis which is concerned with the way the game is controlled. Conceptually musical aspects of games recognize how extra-ludic, real-world music experiences and affective memories create or influence the musical nature of the game. This is often accomplished by featuring a particular genre of music in the soundtrack or including famous musicians as playable characters within the game. We can think of procedural and conceptual musical qualities as the differences between ‘inside-out’ (procedural) or ‘outside-in’ (conceptual) relationships with music.

Games may be predominantly procedurally musical, predominantly conceptually musical or some combination of the two. Many music games employ both logics – they are not only procedurally musical, as they facilitate musical activity, but the games’ music-related themes or narratives render them conceptually musical as well. We can also observe examples of games that are highly conceptually musical, but not procedural (like the artist games named above), and games that are procedural, but not conceptual (like games where players can attend to musical materials to help them win the game, but which are not explicitly themed around music, such as L.A. Noire (2011)).Footnote 11

Types of Conceptual Musical Content

Conceptual music games rely on rhetorical devices similar to those employed in rhetorical language, such as metonyms/synecdoches, which are used to describe strong, closely related conceptual ties, and epithets, for those with looser conceptual connections. A metonym is a figure of speech in which a thing or concept is used to represent another closely related thing or concept. For example, ‘the White House’ and ‘Downing Street’ are often used to represent the entire Executive Branches of the United States and British governments respectively. Similarly, the ‘Ivy League’ is literally a sports conference comprising eight universities in the Northeastern United States, but the term is more often used when discussing the academic endeavours or elite reputations of these universities. There are also musical metonyms, such as noting that someone has ‘an ear for music’ to mean not only that they hear or listen to music well, but that they are also able to understand and/or perform it well. Further, we often use the names of composers or performers to represent a particular style or genre of music as a synecdoche (a type of metonym in which a part represents the whole). For instance, Beethoven’s name is often invoked to represent all Classical and Romantic music, both or either of these style periods, all symphonic music, or all ‘art music’ in general. Similarly, Britney Spears or Madonna can stand in for the genre of post-1970s pop music or sometimes even all popular music.

Metonymic music games are often considered musical because a prominent element of the game represents music writ large to the player or the general public, even if the procedural logic or mechanics of the game are not necessarily musical, or only include a small bit of musical interactivity. For example, The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time is, by almost all accounts, an action-adventure game. Link, the game’s main character, traverses the enormous gameworld of Hyrule to prevent Ganondorf from capturing the Triforce, battling various enemies along the way. Link plays an ocarina in the game, and, as one might be able to conclude based on the game’s title, the ocarina plays a central role in the game’s plot; therefore, the game could be considered a music game. Amongst the many other varied tasks Link completes, lands he explores, items he collects, and so on, he also learns twelve melodies (and writes one melody) to solve a few music-based puzzles, allowing him to teleport to other locations. For many, the amount of musical material in the game sufficiently substantiates an argument for labelling the game as a music game. Most of the game does not involve direct interaction with music. It is limited to isolated (albeit narratively important) moments. We can therefore describe Ocarina of Time as conceptually musical in a metonymic way, but with limited procedural musical content.

Music games that are even further removed from music and music-making than metonymic music games are epithetic music games. An epithet is a rhetorical device in which an adjective or adjectival phrase is used as a byname or nickname of sorts to characterize the person, place or thing being described. This descriptive nickname can be based on real or perceived characteristics, and may disparage or abuse the person being described. In the case of Richard the Lionheart, the epithet ‘the Lionheart’ is used both to distinguish Richard I from Richards II and III, and to serve as an honorific title based on the perceived personality trait of bravery. In The Odyssey, Homer writes about sailing across the ‘wine-dark sea’, whereas James Joyce describes the sea in Ulysses using epithetical descriptions such as ‘the snot-green sea’ and ‘the scrotum-tightening sea’; in these instances, the authors chose to name the sea by focusing closely on only one of its many characteristics (in these cases, colour or temperature), and one could argue that colour or temperature are not even the most prominent or important characteristic of the sea being described.

Epithetic music games are video games classified by scholars, players and fans as music games, despite their obvious lack of musical elements or music making, due to a loose or tangential association with music through its characters, setting, visual elements, or other non-aural game assets, and so on. These games differ from metonymic games in that music is even further from the centre of thematic focus and gameplay, despite the musical nickname or label associated with them; in other words, the interaction with music within these games is only passive, with no direct musical action from the player required to play the game or interact with the game’s plot.

These epithetic connections are often made with hip-hop games. Hip-hop games are sometimes classified as music games because, aside from the obvious utilization of hip-hop music in the game’s score, many of the non-musical elements of hip-hop culture can be seen, controlled, or acted out within the game, even if music is not performed by the player, per se, through rapping/MC-ing or turntablism. Making music is not the primary (or secondary, or usually even tertiary) object of gameplay. For example, breakdancing is a para-musical activity central to hip-hop culture that can be found in many hip-hop games, but in non-rhythm hip-hop games, a player almost never directs the movements of the dancer. Boom boxes, or ‘ghetto blasters’, are also a marker of hip-hop culture and can be seen carried in a video game scene by non-player characters, or resting on urban apartment building stoops or basketball court sidelines in the backgrounds of many hip-hop-themed video games, but rarely are they controlled by the player. Games such as Def Jam Vendetta (2003), 50 Cent: Bulletproof (2005) and Wu-Tang: Shaolin Style (1999) are sometimes classified as music games due to the overt and substantial depictions of famous hip-hop artists, despite the lack of musical objectives or themes within these fighting and adventure games. Here, particular rappers are used as icons for hip-hop music and musical culture. For example, Def Jam Vendetta is a fighting game wherein hip-hop artists such as DMX, Ghostface Killah and Ludacris face off in professional wrestling matches. Similarly, the NBA Street series features hip-hop artists such as Nelly, the St. Lunatics, the Beastie Boys and others as playable characters, but since the artists are seen playing basketball, rather than engaging in musical activities, they are epithetic and loosely conceptual music games.

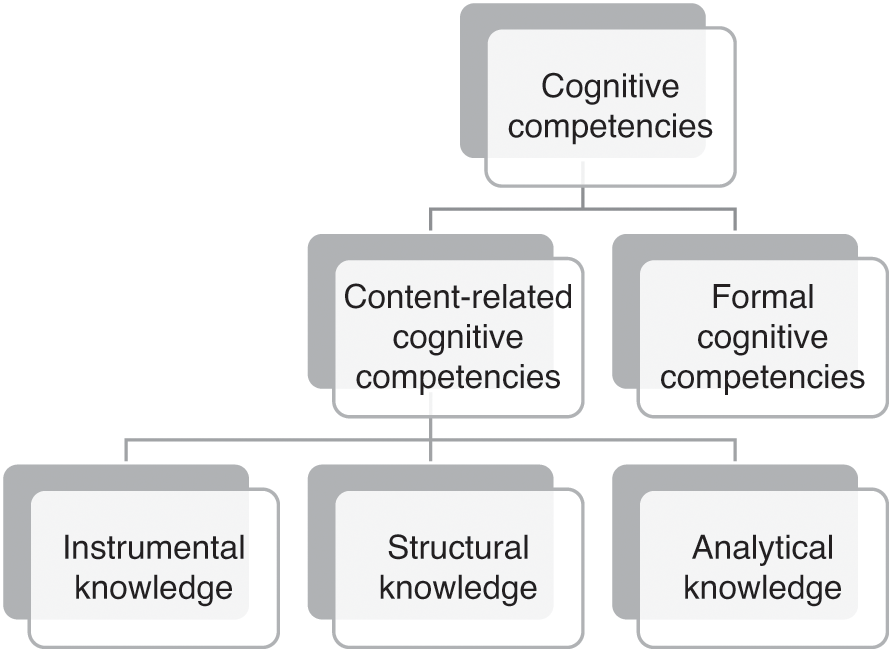

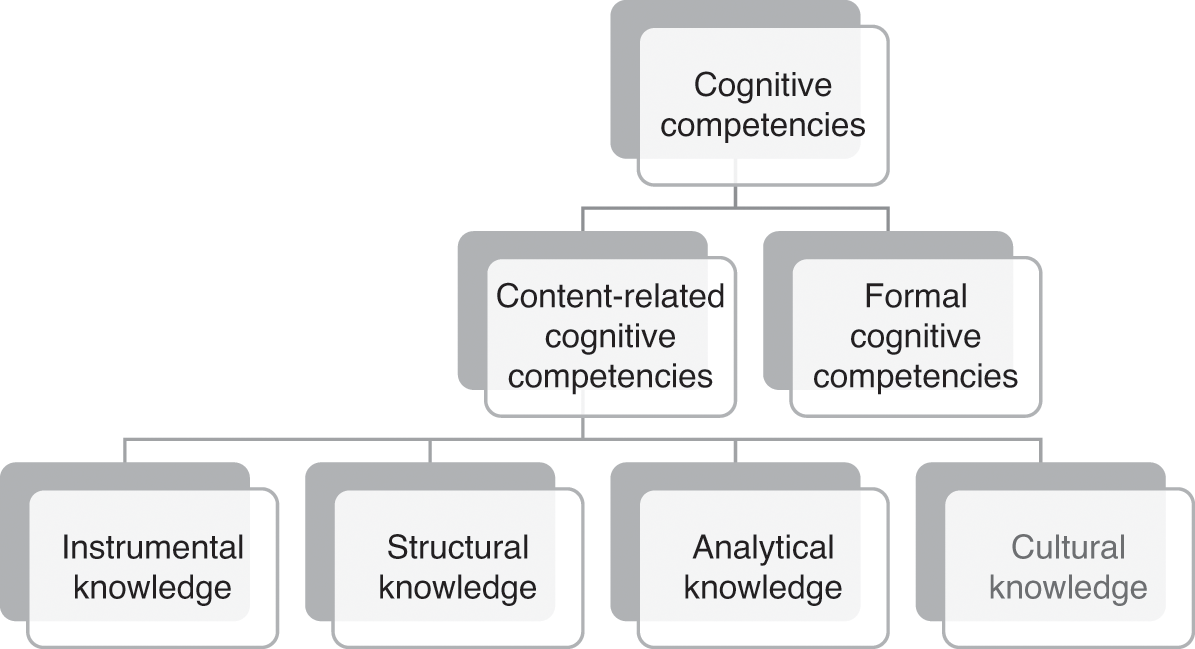

While it might be tempting to classify games as either procedurally or conceptually musical (and often games do tend to emphasize one or the other), this does not allow for the complexity of the situation. Some games are especially musical both procedurally and conceptually, as is the case with games such as those in the Rock Band and Guitar Hero series which require players to perform musical activities (rhythm matching/performing) in a conceptually musical gameworld (as in a rock concert setting, playing with rock star avatars, etc.). It is perhaps more helpful to consider the two elements as different aspects, rather than mutually exclusive. The procedural–conceptual axes (Figure 9.1) can be used to analyse and compare various music games, plotting titles depending upon which traits were more prominent in each game. We can also note that the more a game includes one or both of these features, the more likely it is to be considered a ‘music game’ in popular discourse.

Figure 9.1 Graphical representation of procedural–conceptual axes of music games

Using this model, Rocksmith would be plotted in the upper right-hand corner of the graph since the game is both especially procedurally musical (rhythm-matching game that uses a real electric guitar as a controller) and conceptually musical (the plot of the game revolves around the player’s in-game career as a musician). Rayman Origins (2011) would be plotted closer to the middle of the graph since it is somewhat, but not especially, procedurally or conceptually musical; on the one hand, players that synch their movements to the overworld music tend to do better, and the game’s plot does have some musical elements (such as a magical microphone and dancing non-playable characters); on the other hand, this game is a platform action game in which the object is to reach the end of each level, avoid enemies and pick up helpful items along the way, not necessarily to make music per se. Games in the Call of Duty or Mortal Kombat franchises, for example, would be plotted in the bottom-left corner of the graph because neither the games’ mechanics nor the plot, setting, themes and so on, are musical in nature; thus, it is much less likely that these games would be considered by anyone to be a ‘music game’ compared to those plotted nearer the opposite corner of the graph.

Conclusions

Even if music video games never regain the blockbusting status they enjoyed in the mid-to-late 2000s, it is hard to imagine that game creators and publishers will ever discontinue production of games with musical mechanics or themes. While the categorical classification of the music game and its myriad forms and (sub)genres remains a perennial issue in the study of music video games, there exists great potential for research to emerge in the field of ludomusicology that dives deeper into the various types of play afforded by music games and the impact such play can have on the music industry, the academy and both Eastern and Western cultures more broadly.

When studying a video game’s musical soundtrack, how do we account for the experience of hearing the music while playing the game? Let us pretend for a moment that a recording of Bastion (2011) is not from a game at all, but a clip from perhaps a cartoon series or an animated film.Footnote 1 We would immediately be struck by the peculiar camera angle. At first, when ‘The Kid’ is lying in bed, what we see could be an establishing shot of some sort (see Figure 10.1). The high-angle long shot captures the isolated mote of land that The Kid finds himself on through a contrast in focus between the bright and colourful ruins and the blurry ground far beneath him. As soon as he gets up and starts running, however, the camera starts tracking him, maintaining the isometric angle (from 0’02” in the clip). While tracking shots of characters are not uncommon in cinema, this particular angle is unusual, as is the rigidity with which the camera follows The Kid. Whereas the rigidity is reminiscent of the iconic tricycle shots from The Shining (1980), the angle is more similar to crane shots in Westerns like High Noon (1952). It would seem easy to argue that the high angle and the camera distance render The Kid diminutive and vulnerable, but David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson warn against interpreting such aspects of cinematography in absolute terms.Footnote 2 The major difference between traditional action sequences in film and the clip from Bastion is that the latter is essentially one long take, whereas typical (Hollywood) action sequences are composed of fast cuts between shots of varying camera distances and angles. The camerawork of this short sequence, then, creates a certain tension that remains unresolved, because there is no ‘cut’ to a next shot.

Figure 10.1 Bastion’s ‘opening shot’

From this film-analysis standpoint, the music in the clip is less problematic. The drone with which the scene opens creates the same air of expectancy as the camera angle, but it almost immediately fulfils that expectation, as The Kid rises from his bed, a moment accentuated by the narrator’s comment, ‘He gets up’. The Kid’s frantic pace through the assembling landscape is echoed in the snare drum and bass that form a shaky, staccato ground under the masculine reassurance of the narrator’s gravelly voice (whose southern drawl sounds like a seasoned cowboy, perhaps a Sam Elliott character). As The Kid picks up his weapon, a giant hammer (which the narrator calls ‘his lifelong friend’), a woodwind melody starts playing (0’19” in the clip). This common progression in the musical structure – a single drone leading into rhythmic accompaniment, in turn leading into melody – follows the progression in the narrative: The Kid gets his belongings and his journey is underway. But why does the camera not follow suit by cutting to the next ‘shot’?

Consider now a clip I made when playing the same sequence in Bastion on another occasion.Footnote 3 We see The Kid lying in bed, a single drone accompanying his resting state. The drone creates an air of tension, in which we discern the distant sounds of gushing wind. These sounds draw our attention to the rising embers around The Kid’s island high in the sky. Before we can start asking questions about the tension the drone creates – does it signify the emptiness of the sky, or the aftermath of the destruction that is implied in the ruined bedroom in the centre of the shot? – The Kid gets up, and a fast rhythm starts playing. As The Kid cautiously, haltingly, makes his way down a strip of land that starts forming around him in the sky (0’04” in the clip) – the camera following him step by step from afar – the frantic music suggests the confusion of the situation. The music heard in the first clip as underscoring the thrill and excitement of adventure now seems full of the anxiety and halting uncertainty of the protagonist. Yet the narrator suggests that ‘he don’t stop [sic] to wonder why’. So why does The Kid keep stopping?

Hearing Video Game Music

The questions that my analyses of Bastion prompted come from a misunderstanding of the medium of video games. The Kid stopped in the second clip because as my avatar, he was responding to my hesitant movements, probing the game for the source and logic of the appearing ground. I was trying to figure out if the ground would disappear if ‘I’ went back, and if it would stop appearing if ‘I’ stopped moving (‘I’ referring here to my avatar, an extension of myself in the gameworld, but when discussing the experience of playing a game, the two often become blurred). The camera does not cut to close-ups or other angles in the first clip because of the logic of the genre: this is an action-based role-playing game (RPG) that provides the player with an isometric, top-down view of the action, so that they have the best overview in combat situations, when enemies are appearing from all sides. So in order to accurately interpret the meaning of the camera angle, or of the actions of the characters, we need to have an understanding of what it is like to play a video game, rather than analyse it in terms of its audiovisual presentation. But what does this mean for our interpretation of the music?

In my example, I gave two slightly different accounts of the music in Bastion. In both accounts, it was subservient to the narrative and to the images, ‘underscoring’ the narrative arc of the first clip, and the confused movements of The Kid in the second. But do I actually hear these relationships when I am playing the game? What is it like to hear music when I am performing actions in a goal-oriented, rule-bound medium? Do I hear the musical ‘underscoring’ in Bastion as a suggestion of what actions to perform? I could, for instance, take the continuous drone at the beginning of the clip – a piece of dynamic music that triggers a musical transition when the player moves their avatar – as a sign to get up and do something. Or do I reflect on the music’s relationship to my actions and to the game’s visuals and narrative? While running along the pathway that the appearing ground makes, I could ask myself what the woodwind melody means in relation to the narrator’s voice. Or, again, do I decide to play along to the music? As soon as I get up, I can hear the music as an invitation to run along with the frantic pace of the cue, taking me wherever I need to be to progress in the game. Or, finally, do I pay attention to the music at all? It could, after all, be no more than ‘elevator music’, the woodwinds having nothing particularly worthwhile to add to the narrator’s words and the path leading me to where I need to be.

The questions I asked in the previous paragraph are all related to the broader question of ‘what is it like to hear video game music while playing a game?’ The three approaches that make up the title of this chapter – autoethnography, phenomenology and hermeneutics – revolve around this question. Each of the approaches can facilitate an account based in first-hand experience, of ‘what it is like’ to hear music while playing a video game, but each has its own methods and aims. With each also comes a different kind of knowledge, following Wilhelm Windelband’s classic distinction between the nomothetic and idiographic.Footnote 4 Whereas the nomothetic aims to generalize from individual cases – or experiences in this case – to say something about any kind of experience, the idiographic is interested in the particularities of a case, what makes it unique. As we shall see, whereas hermeneutics tends towards the idiographic and phenomenology towards the nomothetic, autoethnography sits somewhere in-between the two. The three approaches can be categorized in another manner as well. To loosely paraphrase a central tenet of phenomenology, every experience consists of an experiencer, an experiential act and an experienced object.Footnote 5 Autoethnography focuses on the unique view of the experiencer, phenomenology on the essence of the act and hermeneutics on the idiosyncrasies of the object. These are very broad distinctions that come with a lot of caveats, but the chapter’s aim is to show what each of these approaches can tell us about video game music. Since this chapter is about methodology, I will also compare a number of instances of existing scholarship on video game music in addition to returning to the example of Bastion. As it is currently the most common of the three approaches in the field, I will start with a discussion of hermeneutics. Autoethnography has not, until now, been employed as explicitly in video game music studies as in other disciplines, but there are clear examples of authors employing autoethnographic methods. Finally, phenomenology has been explored the least in the field, which is why I will end this chapter with a discussion of the potential of this approach as a complement to the other two.

Hermeneutics

Of the three approaches, hermeneutics is the one with the longest history within the humanities and the most applications in the fields of music, video games and video game music. As an approach, it is virtually synonymous with the idiographic, with its interest in the singular, idiosyncratic and unique. Hermeneutics is, simply put, both the practice and the study of interpretation. Interpretation is different from explanation, or even analysis, in that it aims to change or enhance the subject’s understanding of the object. We can describe three forms of interpretation: functional, textual and artistic. First, interpretation, in the broadest sense of the word, is functional and ubiquitous. Drivers interpret traffic signs on a busy junction, orchestra musicians interpret the gestures of a conductor and video game players interpret gameplay mechanics to determine the best course of action. Second, in the more specialist, academic sense of the word, interpretation is first and foremost the interpretation of texts, and it derives from a long history going back to biblical exegesis.Footnote 6 This practice of textual interpretation involves a certain submission to the authority of a text or its author, and we can include the historian’s interpretation of primary sources and the lawyer’s interpretation of legal texts in this form as well. In contrast, there is a third mode of interpretation, a more creative, artistic form of interpreting artworks. The New Criticism in literary studies is an important part of this tradition in the twentieth century,Footnote 7 but the practice of ekphrasis – interpreting visual artworks through poetry or literary texts – is often seen to go much further back, to classical antiquity.Footnote 8 A hermeneutics of video game music involves navigating the differences between these three forms of interpretation.

Of particular importance in the case of video games is the difference between functional and artistic interpretation. Players interpret video game music for a number of practical or functional purposes.Footnote 9 The most often discussed example is Zach Whalen’s idea of ‘danger state music’, or what Isabella van Elferen more broadly calls ‘ludic music’: music acts like a signpost, warning the player of the presence of enemies or other important events.Footnote 10 But the drone in Bastion warrants functional interpretation as well: as a player, I can understand its looping and uneventful qualities as signifying a temporary, waiting state, for me to break out of by pressing buttons. Artistic interpretation can certainly begin from such functional interpretation (I will return to this later), but it moves beyond that. It is not content with actions – pressing buttons – as a resolution of a hermeneutic issue but wants to understand the meaning of such musical material, in such a situation, in such a video game, in such a historical context and so on. This process of alternating focus on the musically specific and the contexts in which it sits is what is usually referred to as the hermeneutic circle, which is alternatively described as a going back and forth between parts and whole, between text and context, or between textual authority and the interpreter’s prejudices.Footnote 11

One of the most explicit proponents of artistic interpretation in musicology is Lawrence Kramer. First of all, what I referred to as a ‘hermeneutic issue’ is what Kramer calls a ‘hermeneutic window’: the notion that something in a piece stands out to the listener, that something is ‘off’ that requires shifting one’s existential position or perspective in regard to it. In other words, something deviates from generic conventions.Footnote 12 Through this window, we step into a hermeneutic circle of interpretation, which navigates between two poles: ‘ekphrastic fear’ and ‘ekphrastic hope’.Footnote 13 In every artistic interpretation, there is the fear that one’s verbal paraphrase of a piece overtakes or supplants it. The interpretation then becomes more of a translation, missing out on the idiosyncrasies of the original and driving the interpreter and their readers further away from the piece, rather than towards an understanding of it. Ekphrastic fear means that one’s prejudices fully overtake the authority of the work: it no longer speaks to us, but we speak for it. Ekphrastic hope, on the other hand, is the hope that a paraphrase triggers a spark of understanding, of seeing something new in the artwork, of letting it speak to us.

Game music hermeneutics involve another kind of fear that is often held by researchers and that is at the heart of this chapter: are we still interpreting from the perspective of a player of the game, or are we viewing the soundtrack as an outsider? This fear is best articulated by Whalen when he suggests that

[o]ne could imagine a player ‘performing’ by playing the game while an ‘audience’ listens in on headphones. By considering the musical content of a game as a kind of output, the critic has pre-empted analysis of the game itself. In other words, taking literally the implications of applying narrative structure to video-game music, one closes off the gameness of the game by making an arbitrary determination of its expressive content.Footnote 14

In a sense, Whalen’s ‘audience’ perspective is exactly what I took on in my introduction of Bastion. This kind of ‘phenomenological fear’ can be better understood and related to ekphrastic fear through an interesting commonality in the histories of video game and music hermeneutics. Both disciplines feature an infamous interpretation of a canonical work that is often used as an example of the dangers of hermeneutics by detractors. In the case of video games, it is Janet Murray describing Tetris as ‘a perfect enactment of the overtasked lives of Americans in the 1990s – of the constant bombardment of tasks that demand our attention and that we must somehow fit into our overcrowded schedules and clear off our desks in order to make room for the next onslaught’.Footnote 15 In the case of music, this is Susan McClary’s conception of a particular moment in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony as the ‘unparalleled fusion of murderous rage and yet a kind of pleasure in its fulfilment of formal demands’.Footnote 16 These interpretations were made an example of by those unsympathetic to hermeneutic interpretation.Footnote 17 Murray’s work was used by ludologists to defend the player experience of video games from narratological encroachment.Footnote 18 McClary’s work was used by formalist musicologists (amongst others) to defend the listener’s experience from the interpretations of New Musicology – a movement also influenced by literary studies. We might say that there is a certain formalism at play, then, in both the idea of phenomenological fear and ekphrastic fear: are we not going too far in our interpretations; and do both the experiencing of gameplay ‘itself’ and music ‘itself’ really involve much imaginative ekphrasis or critical analogizing at all?Footnote 19

There are two remedies to hermeneutics’ fears of overinterpretation and misrepresentation. First, there are questions surrounding what exactly the player’s perspective pertains to. Is this just the experience of gameplay, or of a broader field of experiences pertaining to gaming? That might involve examining a game’s paratexts (associated materials), the player and critical discourse surrounding a game and ultimately understanding the place of a game in culture. For instance, it is difficult to interpret a game like Fortnite Battle Royale (2017) or Minecraft (2011) without taking into account its huge cultural footprint and historical context. A music-related example would be K. J. Donnelly’s case study of the soundtrack to Plants vs. Zombies (2009).Footnote 20 Like Kramer, Donnelly opens with a question that the game raises, a hermeneutic window. In this case, Plants vs. Zombies is a game with a ‘simpler’ non-dynamic soundtrack in an era in which game soundtracks are usually praised for and judged by their dynamicity, yet the soundtrack has received positive critical and popular reception. The question of why is not solely born out of the player’s experience of music in relation to gameplay. Rather, it contraposes a deviation from compositional norms of the period. Donnelly then proceeds to interpret the soundtrack’s non-dynamicity, not as lacking, but as an integral part to the game’s meaning: a kind of indifference that ‘seems particularly fitting to the relentless forward movement of zombies in Plants vs. Zombies’.Footnote 21 In other words, the soundtrack’s indifference to the gameplay becomes an important part of the game’s meaning, which Donnelly then places in the context of a long history of arcade game soundtracks. By framing the interpretation through historical contextualization, Donnelly lends an authority to his account that a mere analogical insight (‘musical difference matches the indifference of the zombies in the game’) might not have had: experiencing Plants vs. Zombies in this manner sheds new light on a tradition of arcade game playing.

The second remedy involves keeping the player’s experience in mind in one’s interpretations. Context is essential to the understanding of every phenomenon, and it is difficult to ascertain where gameplay ends and context begins.Footnote 22 Even something as phenomenally simple as hearing the opening drone in Bastion as ‘expectant’ is based on a long tradition of musical conventions in other media, from Also Sprach Zarathustra in the opening scene of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) to the beginning of Wagner’s opera Das Rheingold. However, it is important to note that an explicit awareness of this tradition is not at all necessary for a player’s understanding of the drone in that manner, for their functional interpretation of it. In fact, the player’s functional interpretation relies on the conventionality of the expectant opening drone: without it, it would have formed a hermeneutic window that drove the player away from playing, and towards more artistic or textual forms of interpretation. These examples suggest that while the kind of functional interpreting that the experience of playing a game involves and artistic interpretation are to some extent complementary – the hermeneutic windows of artistic interpretation can certainly be rooted in musical experiences during gameplay – they can be antithetical as well. If the player’s experience is often based in their understanding of game-musical conventions, it is only when a score breaks significantly with these conventions that a hermeneutics of the object comes into play. In other situations, the idiosyncrasies of the player or their experience of playing a game might be more interesting to the researcher, and it is this kind of interpretation that autoethnography and phenomenology allow for. Playing a game and paying special attention to the ways in which one is invited to interpret the game as a player might reveal opportunities for interpretation that steers clear of generalization or mischaracterization.

Autoethnography

If the three approaches discussed in this chapter are about verbalizing musical experience in games, the most obvious but perhaps also the most controversial of the three is autoethnography. It contends that the scholarly explication of experiences can be similar to the way in which we relate many of our daily experiences: by recounting them. This renders the method vulnerable to criticisms of introspection: what value can a personal account have in scholarly discourse? Questions dealing with experience take the form of ‘what is it like to … ?’ When considering a question like this, it is always useful to ask ‘why?’ and ‘who wants to know?’ When I ask you what something is like, I usually do so because I have no (easy) way of finding out for myself. It could be that you have different physiological features (‘what is it like to be 7-foot tall?’; ‘what is it like to have synaesthesia?’), or have a different life history (‘what is it like to have grown up in Japan?’; ‘what is it like to be a veteran from the Iraq war?’). But why would I want to hear your description of what it is like to play a video game and hear the music, when I can find out for myself? What kind of privileged knowledge does video game music autoethnography give access to? This is one of the problems of autoethnography, with which I will deal first.

Carolyn Ellis, one of the pioneers of the method, describes autoethnography as involving ‘systematic sociological introspection’ and ‘emotional recall’, communicated through storytelling.Footnote 23 The kinds of stories told, then, are as much about the storyteller as they are about the stories’ subjects. Indeed, Deborah Reed-Danahay suggests that the interest in autoethnography in the late 1990s came from a combination of anthropologists being ‘increasingly explicit in their exploration of links between their own autobiographies and their ethnographic practices’, and of ‘“natives” telling their own stories and [having] become ethnographers of their own cultures’.Footnote 24 She characterizes the autoethnographer as a ‘boundary crosser’, and this double role can be found in the case of the game music researcher as well: they are both player and scholar. As Tim Summers argues, ‘[i]n a situation where the analyst is intrinsically linked to the sounded incarnation of the text, it is impossible to differentiate the listener, analyst, and gamer’.Footnote 25

If the video game music analyser is already inextricably connected to their object, what does autoethnography add to analysis? Autoethnography makes explicit this connectedness by focusing the argument on the analyst. My opening description of Bastion was not explicitly autoethnographic, but it could be written as a more personal, autobiographic narrative. Writing as a researcher who is familiar with neoformalist approaches to film analysis, with the discourse on interactivity in video game music and with the game Bastion, I was able to ‘feign’ a perspective in which Bastion is not an interactive game but an animated film. If I were to have written about a less experimental approach to the game, one that was closer to my ‘normal’ mode of engagement with it, I could have remarked on how the transition between cues registers for me, as an experienced gamer who is familiar with the genre conventions of dynamic music systems. In other words, autoethnography would have revealed as much about me as a player as it would have about the soundtrack of the game.