In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, it became evident that “vulnerable” populations are particularly at risk (ie, elderly, chronic disease sufferers, low-income) from regional impacts of disaster.Reference Brodie, Weltzien and Altman1Reference Zoraster3 Rural communities that tend to have a higher percent of populations age 65 and older and that have reduced access to resources due to small population size, reduced access to health care facilities, primary care providers, and specialists, and often remote locations are at significant risk for increased vulnerability and reduced resilience to disasters.Reference Baernholdt, Yan and Hinton4Reference Goins, Williams and Carter7 In these contexts, pharmacists and pharmacies have important roles to play.Reference Pincock, Montello and Tarosky8

A national standard for emergency dispensing during local and regional emergency situations and/or natural disasters is nonexistent, and existing laws, rules, and regulations vary significantly from state to state.9 All states included in the study include some provision, with varying degrees of specification and allowance, for dispensing during emergency situations, and/or natural disasters.1014 But, while legally there are grounds for dispensing, the question remains: How prepared are community pharmacies to maintain brick-and-mortar functioning during events?

Immediately following Hurricane Katrina, functioning community pharmacies served an important role in provision of medications, especially for patients with chronic diseases.Reference Jhung, Shehab and Rohr-Allegrini15 It is important for pharmacies to be prepared to continue operations for the populations that rely on products and services offered. Preparedness of community pharmacies involves ensuring that “appropriate pharmaceuticals and related equipment and supplies are in stock at the institution” to operate until state and/or federal assistance is available or local area has returned to a normalized state.16 However, a community pharmacy needs to have, not only pharmaceuticals and supplies, but also be able to maintain or resume business operations to deliver products and services to persons seeking routine or non-routine care in the context of a disaster.

First, it is critical to ensure the pharmacy has a well thought out, viable plan, something that can be created by the pharmacy itself, or adapted from readily available templates or existing plans available online, but that takes stock of operational strengths and weaknesses, considers an common array of potential disaster scenarios, and includes steps for continuing business operations, if reasonable, feasible, and safe, to serve their customers/local populations during times of need.Reference Noe and Smith17Reference Brown and Brown20

Second, it is important to ensure that customer records and files are available through protected hardcopy records or off-site data backup, so that, in the chaos that often ensues during disasters and emergencies, people who may have lost a great deal or be injured or searching for loved ones can obtain their regular care. Having records and files safe also reduces the burden for all local populations using pharmacy products and services.Reference Brown and Brown20, Reference Cohen21

Finally, it is important to ensure that the pharmacy is able to physically operate, provided conditions are safe. The typical pharmacy requires on-site power generation (hard to obtain immediately before, during, immediately after disaster events) to operate a PC or laptop, charge cell phones, and keep medications or other vital products (ie, vaccines, insulin) that require refrigeration at a safe temperature.Reference Brown and Brown20, Reference Cohen21 Power outages frequently accompany a diverse array of natural disasters and emergency situations.Reference Klinger, Landeg and Murray22

In the context of public health emergencies (eg, outbreak), community pharmacists and pharmacies can also serve as a possible community health resource, not only through providing education and answering questions for customers, but by having 1 or more trained pharmacy-based immunizers on staff.18, Reference Menighan19

This pilot study investigated basic preparedness in community pharmacies in predominantly rural areas of 5 states, including business continuity (formal disaster/business continuity plan, offsite data backup, and emergency power), as well as infectious disease response capacity (certified pharmacy immunizer on staff).

METHODS

During the fall of 2014, a telephone survey of community pharmacies was conducted. Pharmacies (N = 990) were located in 3 predominantly rural study areas spanning 5 states: North Dakota/South Dakota (ND-SD); West Virginia (WV); and a contiguous area of Southern Oregon/Northern California (Counties in California: Butte, Colusa, Del Norte, Glenn, Humboldt, Lassen, Lake, Nevada, Mendocino, Modoc, Plumas, Shasta, Sierra, Siskiyou, Sutter, Tehama, Trinity, Yuba; Counties in Oregon: Coos, Curry, Douglas, Jackson, Josephine, Klamath) (S.OR-N.CA). During business hours, trained pharmacy student research assistants contacted 100 percent of community pharmacies in the study areas by telephone and asked questions about emergency power (“Does the pharmacy or the building have an emergency power generator?”), data backup (“Does the pharmacy have offsite/online backup or storage of pharmacy data?”), and business continuity planning (“Does the pharmacy have a written plan for continuing operations, including dispensing, following a disaster?”), as well as whether or not the pharmacy offered immunizations.

County-level data for population density, mean area household income, and percent of households with at least 1 person age 65 or older were obtained from the American Community Survey Five-Year Estimates, 2008-2012.23 Pharmacies were classified as being in high- or low-income areas or high- or low-elderly areas based on 50th percentile distribution of mean area household income and percent of households with at least 1 person age 65 or older, respectively. A qualitative analysis of population density revealed that counties with ≥50 persons per square mile typically contained a micropolitan area or were adjacent to an urban center, so low area population density was defined as <50 persons per square mile, all other areas were classified as high area population density. Data were entered into Excel databases, merged, cleaned, and imported into Stata 11.1. Logistic regression and chi square analyses were performed.

RESULTS

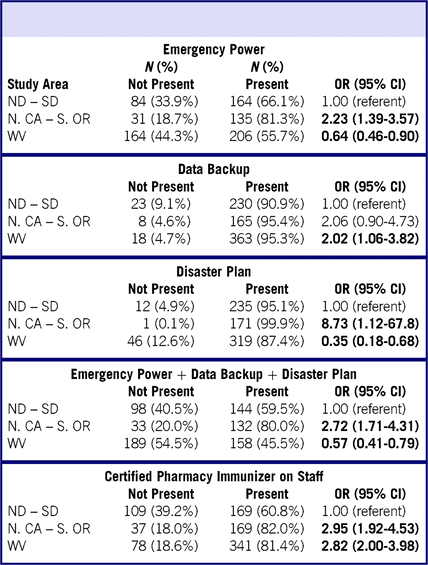

Comparing results among study areas (Table 1), community pharmacies in N.CA-S.OR were more likely to have emergency power generation onsite (81.3%) compared with ND-SD (66.1%) or WV (55.7%). The vast majority of pharmacies had offsite or online data backup (>90%) and a formal plan (>87%) for business continuity in disaster context. However, understanding that each of these factors is essential for providing care during and immediately post-disaster, N.CA-S.OR are significantly more prepared with all 3 criteria met (80.0%) compared with ND-SD (59.5%) or particularly WV (45.5%). Pharmacies in both N.CA-S.OR and WV were significantly more likely to have a certified pharmacy immunizer(s) on staff compared with ND-SD.

TABLE 1 Community Pharmacy Preparedness by Study Area

Abbreviations: ND, North Dakota; SD, South Dakota; N.CA, Northern California; S.OR, Southern Oregon; WV, West Virginia; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Note: Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals in bold are statistically significant at the P < 0.05 level or lower.

More rural areas, defined by county-level population density (Table 2), were no more or less likely to have emergency power, data backup, or a formal disaster plan. While fewer rural pharmacies (68.5%) had a certified pharmacy immunizer(s) on staff compared with less rural areas (82.2%), results were not statistically significant.

TABLE 2 Preparedness of Community Pharmacies in Areas With Low Versus High Population Density

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Note: Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals in bold are statistically significant at the P < 0.05 level or lower.

a Adjusted for study area.

Fewer pharmacies in lower-income areas (59.3%) had emergency power in place compared with their peers in higher-income areas (69.3%), but results were not statistically significant (Table 3). There were no differences between pharmacies in lower- or higher-income areas with regard to data backup or having a disaster plan. However, pharmacies surveyed in lower-income areas were significantly less likely to have all 3 elements of preparedness in place (OR = 0.70; 95% CI: 0.49-0.99) compared with pharmacies surveyed in higher-income areas. Pharmacies in lower-income areas were also less likely to have a certified pharmacy immunizer on staff (OR = 0.68; 95% CI: 0.46-0.99) compared with pharmacies in higher-income areas.

TABLE 3 Preparedness of Community Pharmacies in Lower- Versus Higher-Income Areas

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Note: Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals in bold are statistically significant at the P < 0.05 level or lower.

a Adjusted for study area.

Community pharmacies in areas with ≥30% of households with at least 1 person ≥65 years were significantly less likely to have emergency power (OR = 0.54; 95% CI: 0.39-0.73), to have all 3 elements in place (OR = 0.60; 95% CI: 0.44-0.82), or to have a certified pharmacy immunizer(s) (OR = 0.65; 95% CI: 0.47-0.91) compared with those in areas with <30.0% of households with 1 or more persons ≥65 years (Table 4).

TABLE 4 Preparedness of Community Pharmacies in Areas With High Versus Low Percent of Households With Person(s) ≥65 years

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Note: Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals in bold are statistically significant at the P < 0.05 level or lower.

a Adjusted for study area.

Areas included in the study were predominantly Caucasian, with 95.1% of the counties having ≥85.0% Caucasians. While comprehensive, stratified analyses were not possible due to small numbers, basic analyses of areas with <85.0% Caucasian population, tentatively, did not identify notable differences (absolute or statistically significant) for emergency power, data backup, disaster plan, or all 3 elements combined; however, pharmacies in those areas were significantly less likely (OR = 0.36; 95% CI: 0.19-0.68) to have a certified pharmacy immunizer on staff.

DISCUSSION

There was significant variability among areas with regard to preparedness in key areas (emergency power, data backup, and disaster planning) as well as for certified pharmacy immunizer on staff and overall preparedness.

Emergency power by far was the variable found most lacking, and without emergency power, a good plan and patient/customer data are of little value, at least during and in the short-term after a disaster. Emergency power, compared with data backup or formal disaster plan, was significantly less likely to be present in high-elderly areas. Rates of having an existing source of emergency power were also lower for areas that were lower-income or more rural.

Measures to address short-term emergency power are quite cost-effective and simple to implement.Reference Brown and Brown20, 24, 25 There are whole enterprise emergency power solutions for large brick-and-mortar health care facilities. A bare-bones, temporary, emergency operations power supply for a community pharmacy can be significantly more affordable. An 8,000 watt portable generator from Generac, $1,199 plus sales tax, would be more than sufficient to maintain running and peak (starting) operations for a PC, refrigerator, freezer, simple functional lighting, along with cell phone charging.24, 25 An investment of $5,000 will buy a 22,000 watt standby generator,25 which, if used judiciously, would be capable of powering 3 computers, 6 refrigerators/freezers, and several banks of overhead lights.

Offsite data backup (87.8-96.9%) and formal disaster plans (90.3-94.5%) were present in the vast majority of community pharmacies surveyed. However, having roughly 1 in 10 pharmacies that either has no formal disaster plan and/or no offsite data backup is problematic, given how critical these 2 areas are for business operations and/or resumption during and in the short-term after a disaster.Reference Noe and Smith17Reference Cohen21

Rates for community pharmacies having a certified pharmacy immunizer on staff ranged from 50.0% to 87.7%, with pharmacies in lower-income or high-elderly areas being significantly less likely to report having a certified pharmacy immunizer on staff. Community pharmacies can have a valuable role to play in public health emergencies (eg, influenza) wherein vaccination is a critical component of response.18, Reference Menighan19

The strengths of this study include 100% sample of community pharmacies in 3 geographically large study areas across 5 states with a high overall response rate (75.9%). The study areas were in 3 distinct regions in the United States (Midwest, Appalachia, West Coast), which each have different disaster risk profiles. It is 1 of only a few formal studies investigating disaster preparedness of community pharmacies.

Limitations include that the study is cross-sectional in design. Study areas were discrete; although consistent, results may not necessarily be generalizable to other regions of the United States. The information on disaster preparedness elements was self-reported and not independently verified by the researchers.

CONCLUSIONS

Considering the community-level ability to maintain and/or resume operations in the context of local emergencies and disasters, public health and health services professionals need to be aware that many community pharmacies do not have basic preparedness measures in place that would ensure continuing of operations during a disaster or resuming operations in the short term. Having community-level variables that are associated with greater vulnerability does not seem to equate to having pharmacies being more likely to have basic preparedness components in place; in fact the opposite seems to generally be the case.

Despite scientific evidence on disaster preparedness and pharmacy roles, many pharmacies remain unprepared to operate during or in the short-term following a disaster because they are lacking emergency power, offsite data backup, and/or a formal disaster plan. More than a decade after we learned hard lessons from Hurricane Katrina, vulnerable populations (eg, lower-income, elderly, chronic disease sufferers) seem to still be at risk in many rural communities.

While our findings did not cover rural areas of all states, patterns were quite readily identifiable. Community pharmacists, community pharmacies, and other health and health services professionals need to be aware of this continued risk and work to ensure that formal disaster plans are in place and that these disaster plans can be realized with emergency power and patient data access to provide continuity of care during and in the short-term following disasters.