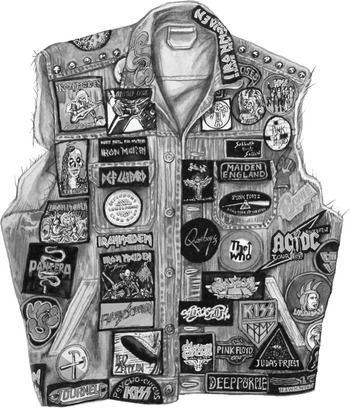

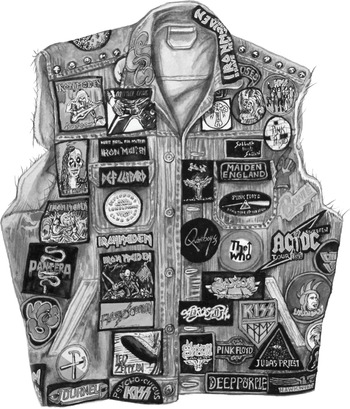

For anyone who has attended a heavy metal concert, or seen fans congregating outside one, the particular aesthetics of metal style will be familiar. Metal clothing is famously characterised by the fabrics denim and leather, to such an extent that the British band Saxon even named a song and album, Denim and Leather (1981), after this combination. The de facto uniform of the concert crowd is the band t-shirt, usually black, adorned with bold graphics and logos announcing the wearer’s band of choice. Paired with jeans and boots or trainers, the band t-shirt is the staple of most metal wardrobes. For the committed fan, the outfit is often completed by a customised ‘battle jacket’ uniquely configured to the wearer’s preference (see Figure 15.1). A battle jacket – also variously known as a battle vest, patch jacket, cut-off or Kutte – is a denim jacket, usually with the sleeves removed, decorated with patches, badges, studs, festival bands, handmade artworks and various other embellishments added by the owner to display their musical taste and allegiances.1

Figure 15.1 Tom Cardwell, Moonsorrow, 2020, watercolour painting on paper, 38 × 26 cm

Battle jackets are an important expression of metal identity for many fans and musicians and allow individuals to demonstrate commitment to metal subcultures and signify difference from mainstream styles and values. This chapter discusses the history and origins of battle jackets as a key component of metal style and considers the meanings and significance of these garments for those that make and wear them. The following argument makes reference to a series of interviews conducted by the author with jacket makers between 2014 and 2020.

Heavy Metal Style

As with the music itself, heavy metal style evolved in large part from the 1960s counterculture, as well as bringing influences from blues culture via 1950s rock ’n’ roll,2 both of which had connections with working class and manual labour, with the prevalence of denim as a workwear fabric giving rise to the term ‘blue collar’.3 Motorcycle culture also had a significant impact on the development of metal style, with the leather jackets, jeans and boots favoured by bikers becoming commonplace in rock and metal wardrobes by the 1970s.4 The historically masculinist codes of such working-class cultures, along with connections to military traditions, have caused many to view heavy metal clothing as at best nostalgic and at worst reactionary,5 with limited stylistic options available for women. Writing in 1985, Philip Bashe identified two alternatives for female metal fans when it came to clothing, either dressing like ‘the boys’ or else adopting the looks of the ‘goddesses they see in their heroes’ videos’.6 Whilst possibilities for more nuanced negotiation of gender identities through metal clothing arguably exist in today’s scenes (more on which later), these connotations ostensibly persist.

One of the key functions of heavy metal style is to mark the wearer as part of the ‘community of all metalheads’7 and to differentiate them from the perceived mainstream.8 As one fan I interviewed, Emily, put it when talking about her jacket: ‘You tend to exclude the mainstream from your insider [culture]. I call it “outsider/insider” because you’re an outsider, but you’re inside of this outsider culture’. This sense of distinction from wider culture is reinforced through the challenging and sometimes extreme nature of the images and texts that feature on metal clothing.9 The ‘insider’ or community aspect of metal fandom is expressed through individuality negotiated within the stylistic structures of the wider subcultural group. A sense of the tribal is apparent in metalhead style, for example, in the prevalence of long hair, beards, tattoos and DIY customisation of clothing.10 In these respects, the battle jacket is emblematic of many aspects of metal culture through its distinctiveness, connection to subcultural structures and traditions and personal construction.

Key Features of a Battle Jacket

Although individually customised, most battle jackets adhere to a set of tacitly agreed conventions amongst makers. The majority of jackets are based on the classic denim jacket epitomised by the ‘type III’ jacket created by Levi Strauss in the USA in the early 1960s;11 other popular garments are leather jackets, military jackets and workwear shirts. This includes a large rectangular area on the back of the jacket formed by the borders of the yoke, side panels and waistband. This area provides a prominent location to display patches or other artwork and is usually the site of a ‘backpatch’ – a large patch featuring detailed artwork and band logo, which is generally chosen to foreground a band that the wearer favours above most others. Around the backpatch, smaller patches can be displayed, often in closely-tessellated rows and columns (see Figure 15.2). The yoke area across the shoulders provides another large space but on a narrow landscape orientation, making it suited for large text-based logo patches, or a series of smaller patches. The area at the base of the back of the jacket is often populated by one or more ‘superstrip’ patches – wide horizontal patches, which usually bear a text logo appended by small artworks.12

Figure 15.2 Metal fan photographed at Bloodstock Festival, UK, August 2014.

The front of the jacket can be adorned with small patches as well as pin badges, studs and festival wristbands sewn on as strips (giving an effect similar to military rank colours) and other chosen additions (see Figure 15.3). Unlike the back of the jacket, the front does not afford any ideal spaces for bigger patches, as it is interrupted by fastenings (for example, buttons and buttonholes), collar, pockets and vertical seams. Nonetheless, some fans manage to feature large patches or artworks on the front, perhaps by changing the orientation of the patch, or cutting the patch in half and sewing half on each side of the front, so that the image is unified when the jacket is closed. Most battle jackets have the sleeves removed, allowing them to be worn over another garment (hence the popular term ‘battle vest’ used interchangeably with ‘battle jacket’), although some choose to retain them, in which case further patches can be added.

Figure 15.3 Tom Cardwell, Aidan’s Jacket (Front), 2015, watercolour painting on paper, 38 × 26 cm

Amongst jacket makers like those interviewed, there are variously acknowledged ‘rules’ about how a jacket should be composed and what type of patches these should feature. These rules are rarely universal but may be upheld as important by certain groups of makers or fans of particular genres of metal. Perhaps the most commonly held view is that a jacket should only feature patches relating to bands that the wearer has a sincere appreciation for. Some extend this to a qualification that one should own physical music (vinyl, cassettes, CDs) by the featured band, and others argue that they must have attended live concerts by each artist. Another common ‘rule’ is that a jacket should not be ‘double patched’, that is, feature only one patch by any particular band. There are many exceptions to this rule, however, notably in the genre of ‘tribute jackets’ that exclusively feature patches representing a favourite band.

Some fans maintain that a jacket should be genre-specific, featuring only patches for 1990s death metal bands or black metal bands, for example. Many jacket makers emphasise the importance of personal choice above genre conformity, however. As a maker called Pete put it:

Because this is documenting my life and my taste in music, and consequently, there’s a lot of non-metal stuff on here as well, which really f**ks people off! The ‘true metal heads’ go, ‘How can you have that next to that?!’, and I say, ‘Because I like ’em!’.

For all the credence extended to various rules by some, a common rejoinder to this attitude is expressed by Simon Springer, founder of Pull the Plug patches: ‘The overarching theme is (that) there should be no rules! It’s metal, it’s supposed to be rebellious’.13

History and Development of Battle Jackets

Whilst it is difficult to say for certain when battle jacket-making first started, it seems to have been well established by the time heavy metal music became widely popular in the 1970s.14 Methods of customisation around this time included hand embroidery, which was practised by fans as a way of rendering band logos on their jackets in the absence of readily available commercial patches.15 Once bands began to cater to the demand for patches, these became a way of commemorating particular gigs and tours, with unique editions sold at merchandise stands in concert venues. This means of distribution lent a sense of authority to the patches, as possessing a particular patch would usually indicate that the wearer had attended the concert it had been sold at. The battle jacket thus became a garment that testified to lived experience, with a heavily patched vest marking its wearer as someone who was deeply invested in the subculture.

The sense of a battle jacket as a marker of subcultural status owes much to the heritage of motorcycle jackets, and particularly the denim or leather ‘cut-offs’ worn by members of ‘outlaw’ bike clubs, which feature patches bearing logos of club affiliation and rank.16 The quasi-military order of the patches on bikers’ jackets is arguably linked to the formation of such clubs by returning veterans after World War II and the Vietnam War in America.17 Military uniforms themselves have been highly influential in heavy metal style, just as themes and imagery of war and conflict feature regularly in metal music. Some bands produce artworks and merchandise that directly reference military insignia and patches,18 and items of combat gear such as camouflaged clothing and army boots are staples of metal fans’ attire. Indeed, the term ‘battle jacket’ directly connects the garments to such traditions. During World War II, bomber crews wore leather flying jackets (most popularly the A2 type), which were often custom painted with the nose artwork from the plane they operated, as well as tally markings that enumerated missions flown or targets destroyed.19

Going back even further in history, early antecedents for metal fans’ jackets might be found in the heraldic tabards and armour worn by combatants in the Middle Ages.20 The tradition of heraldry has continued in folk costumes, such as those worn by Morris dancers, which are customised with badges, bells, coloured fabrics and small objects,21 in a parallel of the customisation of battle jackets. Like battle jackets, these costumes are worn in a performative context and play a key role in marking the wearer as part of the group and a participant in the festivities at hand.

Amongst twentieth century youth subcultures, there are many examples of customised clothing that compare directly to the jackets of heavy metal fans.22 During the 1950s in Britain, informal motorcycle subcultures such as the ‘rockers’ and ‘ton-up boys’ customised their leather jackets (often based on the famous ‘Perfecto’ style popularised by Marlon Brando in the 1953 movie The Wild One) with bike logos, club badges and ‘run patches’, which commemorated particular rides, in much the same way as metal band patches commemorated concerts.23 During the 1970s and 1980s, punks re-appropriated leather biker jackets, which were decorated with hand-painted logos and slogans, studs, chains and other additions.24 A number of post-punk subcultures, such as goths and crustpunks, also used hand-painting on leather jackets as a key mode of individuation.

Whilst battle jacket-making has remained an important part of metal subcultures since the practice was first established, there have been periods and genres of metal in which it has been particularly popular. The early 1980s was one such period when genres such as the New Wave of British Heavy Metal (NWOBHM) in the UK and thrash metal in the USA both saw an emphasis on battle jackets amongst musicians and fans. During the 1990s, battle jackets were perhaps less common, as the genres of nu metal and grunge changed the style and expression of metal fans,25 although even during this period, jacket customisation practices persisted in extreme genres such as black metal26 and death metal. After the turn of the millennium, the popularity of previous styles of metal grew once more, and battle jacket-making enjoyed a renaissance, which has continued until now.27 Today, battle jackets are very much in evidence in many metal scenes, with a large online community that post images of jackets and trade patches.28 Part of the present popularity may be driven by the nostalgic interest of veteran fans, who wish to revive the jacket-making of their younger days. Louis, a jacket maker who sells patches and jackets through an online store, comments: ‘I do get a lot [of customers] who are older …, and they had their own jackets back in the day, and they’ve either sold them or lost them, and now they see that they can get another one’.

Global Jacket Scenes

If battle jackets, like heavy metal music and culture more broadly, were once considered predominantly Western, today they are increasingly globalised.29 Metal fans and musicians in Australasia, Africa, Asia and South America, as well as Europe and North America, have taken up jacket customisation as part of their identification with metal culture.

In Malaysia, Marco Ferrarese found that fans placed great importance on obtaining authentic patches of death and thrash metal bands from the 1980s and 1990s to populate their jackets, with Western bands being particularly sought after.30 In Indonesia, patch collecting is also a big part of metal culture, with fans using social media to showcase their densely patched jackets.31 For fans in Nepal, the prohibitive cost of metal merchandise compared to local wages can be a limitation for fans, although many will use DIY methods to customise various items of clothing.32 For the ‘cowboy metalheads’ of Botswana,33 leather clothing is more common than denim, although some fans there sew band patches onto their jackets or waistcoats, with bands such as Iron Maiden and Cannibal Corpse being particularly popular.34

Whilst the exact expression of battle jacket practices varies from place to place, reflecting geographic and cultural specificities, in many ways, battle jackets can be considered a globally observed marker of metal fandom, with the universalising effects of online discourse allowing fans everywhere to post and view jackets and obtain patches. Like the ubiquitous band t-shirt,35 the battle jacket is an overt way for fans everywhere to stand out from the crowd and fit in with metal subcultures.

‘They Should Represent Your Life’: Personal Meanings and the Subcultural Significance of Battle Jackets

Within most subcultures, negotiating personal identity within the tacitly agreed structures of the subcultural community is important. In her research into club cultures in the UK during the 1990s, Sarah Thornton emphasised the importance of gaining and maintaining ‘subcultural capital’ for members of these scenes.36 In relation to metal, Nicola Allett looked at the ‘connoisseurship’ exhibited by extreme metal fans, expressed through distinctions of taste and esoteric knowledge of metal music and culture.37 David Muggleton has written extensively about the conditions of subcultural engagement in a postmodern context, highlighting the importance of ‘insider/outsider’ distinctions and individual negotiation of a personal sense of subcultural identity.38 Authenticity is key for many subcultures and is especially important in heavy metal. J. Patrick Williams summarises some of the important debates on this in subcultural literature.39 Niall Scott discusses ways in which resistance is demonstrated amongst metal fans, whether on a literal or symbolic level, and the importance of symbolism in this regard.40 Metal fans continue to signify differences from mainstream culture and allegiance to metal through their clothing and appearance, as Rosemary Overell41 and Paula Rowe42 both testify in their research.

As I have demonstrated through my own research,43 the making and wearing of a battle jacket represents a serious investment (of both time and money) in metal culture by the fan. Lauren O’Hagan also emphasises this point in her interview study of a broad group of metal fans who post and discuss their jackets online.44

Identity

For many fans, a sense of personal identity is closely bound up with the meanings of their battle jacket. As one interviewee called Eleanor remarked: ‘It’s expressive. It is who you are. It’s definitely important. I think we … find style quite an important thing’. Another fan, Alex, put it this way: ‘This is a personal thing. You can’t go and buy a jacket like this. And why would you, if you could? Because it doesn’t make sense’. For Alex, the meaning of the jacket is fundamentally tied to its uniqueness, and the fact that she made it herself.

The choice of patches, as well as their arrangement on the jacket, are some of the most important factors for any wearer, with the selection of bands to feature indicating a fan’s taste and showing others within the subcultures which genre(s) of metal they identify with.

Whilst there may be a sense in which the wearer is conscious of peer approval in this selection,45 many claim that it is important to show their personal taste, even if others may consider this idiosyncratic. Pete, a long-time jacket maker and metal musician, emphasised the importance of authentic expression in his choice of band patches. In a view that is characteristic of many in metal subcultures, Pete would only feature patches on his jacket from bands that he had a strong liking for, and in most cases, had seen in concert:

They should represent your life. And in this case, my life in bands. Like the bike jackets. You only get a patch if you’ve done something to get it … you have to earn them by being there and getting it and saying, ‘I was there and here’s the proof!’ And that’s how I treat this jacket. I only put on patches of bands that I have seen live, and that’s a rule.

In this sense, the jacket acts as a document of lived experience, a form of externalised autobiography for the metal fan. In a broader popular culture landscape in which style is often chosen over substance, the battle jacket wearer values genuine investment in the music and culture they are displaying on their clothing. Authenticity is a fundamental value for metalheads,46 and this is visually communicated through the DIY construction of the battle jacket47 – the handmade aspects testifying to personal investment through its making and a lack of concern for ‘slickness’ or refinement – as well as through patch choices.

Patches may also carry personal meanings. For Tony, some reminded him of his changing musical tastes, whilst a particular patch was connected to a life change when his girlfriend moved in with him:

The Almighty patch is off my old jacket. So that patch is over twenty years old, as is the Wolfsbane one. The Skid Row one’s off my old jacket. The Volbeat one’s new, Airbourne one’s new. But the Slash one, I actually found that one, I’ve just had my girlfriend move in with me, and I was clearing out a load of drawers, and I found it at the bottom of the drawer.

Battle Jackets and Gender Identities

As has been previously mentioned, the prevalence of denim and leather in metal style can often be thought of in terms of working-class masculinities.48 For early metal scholars writing in the 1980s and 1990s, these styles, and the subcultures they represented, were interpreted as masculinist and even misogynistic.49 Whilst a ‘traditional’ white male audience is still predominant in many genres of metal,50 increasingly, academic research testifies to growing diversity in heavy metal.51 Feminist and queer perspectives bring new interpretations to metal and metal style.52

Niall Scott suggests that metal masculinity ‘is in a confident state of flux and diverse in its expression’,53 offering a range of expressive options for men that do not necessarily conform to traditional gender representations. In her study of female metal fans in Canada, Jenna Kummer argued that these women resisted patriarchal meanings through the active choices they made with their clothing, responding in personal ways to challenge or subvert masculinist expectations.54 A queer perspective on metal culture is expounded by Amber Clifford-Napoleone, who suggests that metal culture, in general, can be read as a ‘queerscape’ that does not necessitate the reinforcing of traditional gender norms.55 Clifford-Napoleone points to the influence of queer BDSM (Bondage, Domination and Sado-Masochism) clothing on metal style.56 Perhaps the most famous example of this is Rob Halford, frontman of Judas Priest and arguably the most prominent openly gay metal musician.57 The prominence of hand sewing, and even embroidery, in battle jacket-making offers a contrast to common gender expectations, as in many other areas of culture, needlework is still thought of as a feminine occupation, which is less likely to be embraced by men.58

Whilst many who make battle jackets are male, an increasing number of women are taking up jacket-making on their own terms. Some suggest that female fans bring different approaches to their jackets, as this excerpt from my interview with two jacket makers, Eleanor and Jemima, indicates: ‘A lot of the guys actually tend to have really laid-out … regimented structured jackets. Boys do it. But I prefer things to be a little bit out-of-place and a little bit … wonky and stuff like that’. Others discuss bringing particular design agendas to their jacket-making, and all view it as an important means of self-expression. Yasmin, a British Pakistani woman, who is a prolific jacket maker, emphasises the growing possibilities for expressing diversity through metal styles: ‘It’s nice to see [people from] other backgrounds with battle jackets or people who are into metal, as metal is mostly male, or a white audience’. As a deeply personal garment that offers connections to wider subcultural norms and discourses within metal, a battle jacket provides scope for the individual to express their own identity and values in ways that an ‘off-the-peg’ item would not.

Conclusion

Worn in various guises by fans for around the last fifty years, battle jackets are firmly established as a key element of heavy metal style. Whilst perhaps not as ubiquitous as band t-shirts, battle jackets epitomise serious metal allegiance in a way that no other garments do. The personal customisation and DIY ethos of these jackets allow them to function as unique expressions of individual identity, as documents of lived experience and as an externalisation of the wearer’s musical taste. The collecting and trading of patches, as well as the posting and responding to images of jackets online, are key aspects of the international battle jacket community.

Like heavy metal itself, whilst battle jacket-making might have started in Europe, Great Britain and North America, it is an increasingly globalised practice which connects fans in disparate locations. Battle jacket-making offers the individual fan the opportunity to negotiate and express their personal identity whilst also connecting them to wider metal subcultural communities. This interface of the personal and the communal is reflected in the material structure of the battle jacket, as the common form and framework facilitate personal configuration. As one fan put it, ‘[t]hey should represent your life!’.