The digital economy, centred on the internet, has transformed the business landscape and provides a global platform for the execution of e-commerce. However, due to the absence of face-to-face interactions, consumers are more vulnerable in e-commerce than in offline transactions. Consumers can deal directly with traders at their premises in offline commerce, whereas e-commerce transactions take place virtually, leaving consumers more susceptible to fraud. In addition, consumers cannot physically examine the products prior to making purchases; hence, they rely heavily on information provided online. In comparison, traders have greater information and knowledge about the products compared to consumers. A misallocation of resources is likely to occur where traders produce limited or irrelevant information, whereas consumers fail to act sensibly on the information they receive. This is a classic example of the market failure that results from information asymmetry.Footnote 1 Therefore, a duty of information serves as a safeguard to ensure a ‘parity of arms’ between traders and consumers.Footnote 2 As Geraint Howells emphasised:

Consumers have less information than traders and so have difficulty in making decisions that reflect their true preferences. There are not sufficient incentives for traders to volunteer information, so the law needs to require that the information be provided. Once this information is provided, consumers can protect their own interests by selecting the goods or services closest to their preferences. Harm will be reduced by ensuring goods and services are more likely to be in line with realistic consumer expectations based on reliable information.Footnote 3

The low-cost options for marketing products in e-commerce have also lowered the barriers to entry for fraudsters. Setting a website or other online presence is cheap and easy, allowing highly persuasive scammers to approach consumers.Footnote 4 Given that consumers cannot always rely on traders to provide honest representation, the law plays a crucial role in providing protection against traders who may intentionally provide false, inaccurate, or misleading information to entice consumers to buy their products. For the law to be effective, it must be recognised and accepted by the general public, as well as enforceable, stable, consistent, and flexible.Footnote 5 Therefore, key market players (eg, traders, consumers, or buyers) must first be informed of and understand the provisions of the Consumer Protection Act 1999 (CPA) in Malaysia. Otherwise, these stakeholders will not be able to carry out their legal duty and exercise their statutory rights to the fullest. Second, law enforcers must be able to identify and arrest those who violate the CPA and bring them to justice. Third, the CPA itself needs to be stable and consistent. Therefore, lawmakers must avoid making unnecessary changes that confuse market players. Finally, the CPA must be flexible and adaptable to remain relevant and capable of protecting consumers despite the rapid changes in the e-commerce market.

Although the CPA is the primary legislation for consumer protection in Malaysia, it has been unable to keep pace with the technological advancements in e-commerce. In particular, it is outdated and has neglected the fundamental importance of ensuring informed consumers. This article identifies areas of the CPA that are in need of reform using a doctrinal approach to ensure that consumers can make informed decisions and are adequately protected in modern e-commerce transactions. In addition, this article takes a comparative approach, examining how the English legal framework provides comprehensive protection to consumers and addresses information duty in a rapidly changing and challenging e-commerce market. As a member of the European Union (EU) (before Brexit), the United Kingdom is bound to apply EU laws.Footnote 6 The UK government and UK courts must apply, follow, and give primacy to EU laws and the decisions of the European Court of Justice (CJEU) in Luxembourg.Footnote 7 Consequently, UK law has been influenced by EU lawsFootnote 8 while the CJEU's decisions bind the UK courts on issues involving EU law. EU law operates in tandem with the laws of its Member States. Therefore, it is unsurprising that English consumer law today is an operational and doctrinal hybrid of common law and civil law systems.Footnote 9

Comparisons with English law provides new insights and pragmatic suggestions for legal reform and regulatory improvements of consumer law in Malaysia. Furthermore, ‘borrowing’ legal rules and approaches that have already been successfully ‘tested’ abroad via legal transplants can be a more cost-effective alternative. Instead of guessing possible solutions and risking fewer effective approaches, Malaysia should consider the enormous wealth of legal experience from a more advanced jurisdiction.Footnote 10 Specifically, the appropriate transplantation of English law may lower the costs of enacting new laws or switching from one set of rules to another. Indeed, ‘[T]he reception of foreign legal institutions is not a matter of nationality, but of usefulness and need. No one bothers to fetch a thing from afar when he has one as good or better at home, but only a fool would refuse quinine just because it didn't grow in his back garden.’Footnote 11 The Malaysian legal system is also primarily based on the English common law resulting from colonisation by the British empire.Footnote 12 Although the Federation of Malaya (the polity that existed before the formation of Malaysia) attained independence from Britain in 1957, English law retains influence and its application remains permitted in Malaysia to a limited extent.Footnote 13 Certain English statutes have also been modified to suit local circumstances.Footnote 14 In addition, legal transplant is a common technique in the process of legal reform in Malaysia. The CPA itself draws extensively from consumer protection legislation in various countries such as New Zealand, Australia, and the UK.Footnote 15

The Preconditions of Effective Consumer Information

The duty of information is among the most fundamental regulatory instruments for achieving the objectives of consumer policy.Footnote 16 Information duty can enhance consumer protection,Footnote 17 whereas the absence of sufficient information may result in market failure.Footnote 18 The law must ensure that the information provided to consumers is effective; namely, it is clear, understandable, engaging, and, most importantly, enables consumers to make informed decisions. However, determining the proper method of providing information and the appropriate information duty is not always straightforward. It is for the law and the courts to identify the solutions to these dilemmas.Footnote 19 In general, there are three primary types of information that a consumer is likely to seek when considering making a purchase, namely, (i) the price of the product and other products (substitutes and complements), (ii) product quality, and (iii) the Terms & Conditions (T&Cs).Footnote 20 If consumers possess and understand these three types of information, they can make an optimal purchase and fulfil their economic role as a maximiser of their own utility.Footnote 21

The importance of effective information has gained much attention from both government agencies and academic experts. The Financial Conduct Authority in the UK, for example, has identified several principles of smarter consumer communications. Among others, communication should be in plain and understandable language to meet the needs of the targeted audience. Furthermore, it must be made available at an appropriate time so that consumers can initiate prompt action.Footnote 22 Similarly, the UK Office of Communications (OFCOM) has proposed seven potential characteristics for evaluating information; namely, awareness, accessibility, trustworthiness, accuracy, comparability, clarity, understandability, and timely.Footnote 23 Other scholars argue that information must be effective in terms of both contents and presentation, ie, communicated in a manner that consumers can understand to translate into action.Footnote 24 In addition, transparent information has been viewed as the primary approach to consumer protection. Transparency refers to ‘an obligation to disclose (or not omit) certain information deemed needed by consumers to improve informed decision making’.Footnote 25 Information is therefore effective if it promotes transparency as it enables consumers to make informed and efficient choices.Footnote 26 What constitutes transparent information, however, varies according to the legal system of the respective country. Under English law, a written term or consumer notice is transparent if expressed in plain, intelligible language and legible.Footnote 27 Meanwhile, neither Malaysian law nor the CPA has any provision requiring consumer information to be transparent. This is the main issue that requires attention under Malaysian consumer law. Simply requiring traders to provide information is fruitless without clear guidance on the quality of the information itself. Accordingly, ‘good consumer information’ comprises transparency, comprehensibleness, comparability, clarity, being fit for personal needs, and verifiability. Regrettably, the information that consumers currently receive hardly meet these requirements.Footnote 29

ACCURATE Information

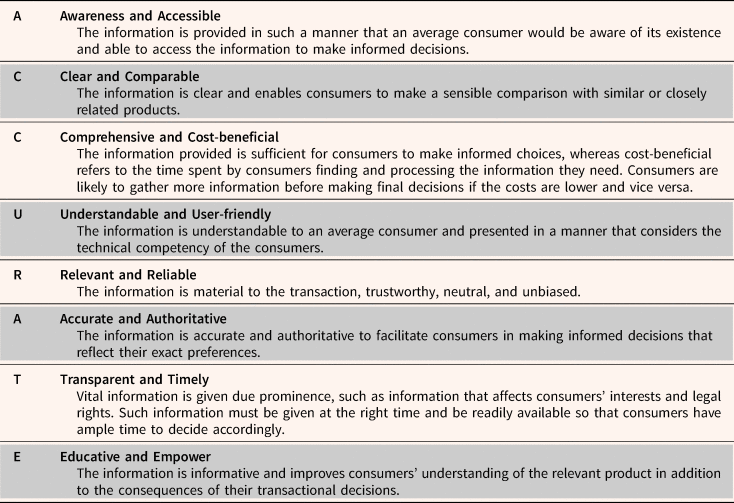

This article argues that information is effective if it comprises crucial values encapsulated by the acronym ACCURATE. The ACCURATE framework proposed herein was developed based on the analysis of different key elements of effective information proposed by government agencies and academic experts as discussed above. The underlying principles of ACCURATE information are interrelated; thus, consumer information can be deemed effective if it displays most, if not all, of the ACCURATE aspects, as summarised in Table 1 below.

Table 1: The Essential Principles of ACCURATE InformationFootnote 28

The ACCURATE framework can be used as a benchmark to assess whether the CPA has mitigated the inequality of bargaining power between traders and consumers by ensuring that consumers have sufficient information to make informed purchase decisions. However, even if consumers are given ACCURATE information, they may not necessarily become well-informed buyers if they themselves do not read the information. Insights from behavioural economic studies have also noted that transparent information does not necessarily produce well-informed consumers.Footnote 30 First, when there is too much information to process prior to making a decision, consumers tend to focus exclusively on the core aspects of the transaction. Some consumers cease searching or will collect less information when it is costly (eg, time-consuming) to gather and process that information.Footnote 31 Second, consumers may be overly optimistic, thus fail to anticipate future risks. This may be due to highly positive marketing techniques, prior psychological commitment to make purchases, and the risks and benefits of the transaction being framed in sophisticated ways. Third, consumers assume that traders are likely to disagree with any changes to the information in the T&Cs. Therefore, consumers frequently disregard the T&Cs, assuming that they are the industry standard and represent ‘the law’.Footnote 32 In essence, the core principles of the ACCURATE framework proposed herein may not necessarily serve as a legitimising factor for informed consumers or guarantee that consumers will act rationally and make wise decisions. However, it can represent a basis for consumers to give informed consent within the continually changing e-commerce environment. The ACCURATE information framework can also serve as a focal point for regulatory debates in Malaysia regarding the effectiveness of the CPA and the necessity of legal reform.

The Consumer Protection ACT 1999

The CPA addresses various consumer-related issues not considered by other prevailing laws in Malaysia, but it does not emphasise the duty of traders to provide information. Consequently, consumers are unable to make prudent buying decisions due to insufficient information.Footnote 33 The Act is also limited, irrelevant, and too outdated to deal with the complexities of e-commerce,Footnote 34 thereby increasing consumers’ vulnerability. These lacuna are discussed in detail below.

The Duty of Information

Information duty is one of the most widely used tools in consumer law as it empowers consumers to make informed decisions.Footnote 35 It is, however, unfortunate that the CPA is less concerned with the role of information – the absence of which exposes consumers to the risk of making uninformed purchasing decisions. The CPA merely prohibits traders from making false or misleading representations about goods and services,Footnote 36 but it does not explicitly require traders to disclose material information before consumers make purchases. The Act is also silent on the obligation of traders to present information in a manner that average consumers can easily understand. Information duty operates on an ex-ante basis to prevent consumers from experiencing harm (eg, receiving goods of unacceptable quality or non-mercantile goods), as shown in Naza Motor Trading Sdn Bhd v Faizah binti Othman (henceforth ‘Naza’).Footnote 37 Here, the consumer bought a Mercedes Benz car that had technical issues after five months of use. The car required a type of fuel called ‘Euro 5’ that was unavailable in Malaysia, but that requirement can be modified to allow the car to function in local settings. The Court held that the dealer was liable for failing to supply acceptable and merchantable quality goods as required under the CPA and the Sale of Goods Act 1957 (SOGA).Footnote 38 Arguably, the purchaser would have been able to minimise the risk of economic loss and made an informed decision if the CPA had initially placed a duty on businesses to disclose material information before the consumer's final decision. As illustrated in Naza, the purchaser would have decided otherwise if she was informed of the technical limitation from the outset.Footnote 39

The absence of information duty under the CPA gives traders discretion over what information to disclose and how to convey it to consumers. The information may be of poor quality, written in vague and complicated language, printed in small fonts, and mixed in with traders’ endless T&Cs. In these instances, consumers may not understand the information, let alone read it. Consumers are also prone to ‘bounded rationality’Footnote 40 whereby they can only process a limited amount of information at a time. The concept of ‘bounded rationality’ refers to actual human thinking and behaviour that differs from that which is expected of a rational consumer. Such biases include the habits and tendencies of humans that systematically underestimate or overestimate certain kinds of risks. Consumers, for example, tend to be overconfident in their abilities and their faith in the quality and reliability of the information given. Consequently, they might underestimate the probability of a dispute with the trader and thus ignore information such as disclaimers and T&Cs.Footnote 41 Consumers also tend to rely on their personal heuristicsFootnote 42 to simplify their decisions when dealing with a significant amount of information. Nevertheless, they may develop cognitive biases,Footnote 43 cease reading material information, and make purchases against their best interests. Furthermore, consumers who wish to bring legal action against a trader in Malaysia must establish that the trader's conduct or representations have led them into error.Footnote 44 For example, in Euromobil Sdn Bhd v Nan Ya Hardware Sdn Bhd, the Court held that ‘it is the Plaintiff who brought this suit, and in consumer protection claims, the burden is still on the Plaintiff to prove based on the balance of probability by following section 101 of the Evidence Act 1950’.Footnote 45 Arguably, it is challenging for consumers to prove that they were led into error if traders do not owe them a legal duty of information in the first place. Consumers also have to represent themselves before the Tribunal for Consumer Claims without the assistance of a lawyer.Footnote 46 As such, consumers must be well-versed in their statutory rights, which can be challenging if the CPA itself does not explicitly grant them the right to be informed.

Outdated Legislation

The CPA has been in force for two decades, yet it has not developed in line with modern e-commerce transactions. Most of the key provisions and scope of coverage has remained unchanged, thus raising doubts about its effectiveness in the digital age. The term ‘in trade’, for example, is the key concept which defines the protection offered by the CPA.Footnote 47 In general, ‘trade’ refers to ‘[t]he business of selling, [for] profits, goods which the trader has either manufactured or himself purchased’.Footnote 48 Meanwhile, the CPA defines ‘trade’ as ‘any trade, business, industry, profession, occupation, activity of commerce or undertaking relating to the supply or acquisition of goods or services’.Footnote 49 Such a broad interpretation of ‘trade’ offers little assistance in identifying who is the trader acting ‘in trade’ within the scope of the CPA. In addition, the CPA does not clarify whether ‘trade’ that fall within its remit refers to commercial sale, private sale, or both. Judicial assistance is also limited regarding the term ‘in trade’ and the dividing line between commercial and private trade.Footnote 50 Arguably, private traders are unlikely more aware of consumer law requirements than professional traders, and subjecting them to the CPA may impose additional burden on law enforcement. Enforcement authorities, in particular, may struggle to police a larger number of small-scale traders in the e-commerce marketplace compared to a smaller number of large-scale traders.Footnote 51

The fine line between a commercial and a private sale creates challenges in determining when a private trader qualifies as a commercial trader acting ‘in trade’ under the CPA. For example, many Malaysians generate extra income by selling handmade products on social media platforms (eg, Facebook). These individuals trade on occasion, and it is uncertain if their activities are considered ‘in trade’ during those periods and, therefore, should comply with the CPA. Furthermore, some individuals sell refurbished items (eg, laptops or iPhones) in addition to their used products, raising the issue of whether they are professional traders, private traders, or both. However, if private traders are not recognised as acting ‘in trade’ under the CPA, consumers who buy from them will have limited rights compared to those buying from professional traders in a commercial sale. Consumers may assert their rights under general contract law, ie, the Contract Act 1950 (CA) or SOGA, but relying on these statutes put them at a disadvantage. Both are archaic laws, favouring the principles of freedom of contract and contain no provisions on consumers’ right to information. If a private trader contests the consumer's claim, the parties may have to seek judicial redress, which could be both costly and time-consuming. The burden of proof will be more complicated in a private sale because it is usually made informally with no written agreement or sale invoice. Furthermore, when purchasing goods from private traders, the principle of caveat emptor (let the buyer beware) is often applied, ie, it is the buyer's responsibility to check the quality and suitability of the goods or services prior to purchasing them.

The CPA also defines a ‘consumer’ as a person who ‘acquires or uses goods or services of a kind ordinarily acquired for personal, domestic or household purpose, use or consumption’.Footnote 52 However, the Act does not further elaborate on this interpretation. Relying on the reason for which the goods were purchased and their intended use to determine whether a person is a consumer under the CPA does not reflect the actual state of today's transactions. The purpose of the purchase is difficult to deduce as it requires an assessment of the buyer's subjective state of mind prior to making a final decision. Although a purchaser who acquires goods for business purposes is not a ‘consumer’ under the CPA, in practice, many buyers nowadays purchase goods for both private and business purposes. For instance, some purchase laptops or smartphones exclusively for personal use, whereas others buy them for personal and business purposes. In the latter case, it is uncertain whether those consumers fall within the definition of ‘consumer’ under the CPA. Fortunately, the CPA's interpretation of the term ‘consumer’ is similar to that of the Consumer Guarantees Act 1993 (CGA)Footnote 53 and Fair Trading Act 1986 (FTA)Footnote 54 in New Zealand, another Commonwealth jurisdiction that share the same common law roots as Malaysia. Therefore, the New Zealand Court of Appeal's view in Nesbit v Porter Footnote 55 may shed light on the meaning of ‘consumer’ under the CPA. The Court held that ‘ordinarily’ is used in the sense of ‘as a matter of regular practice or occurrence’ or ‘in the ordinary or usual course of events or things’.Footnote 56 This suggests that the phrase ‘ordinarily acquired for personal, domestic or household purpose, use or consumption’ focuses not on the dominant use of a product but what is considered ‘ordinary’. For example, a business is a consumer and may seek protection under the CGA if they purchase a laptop – an ‘ordinary’ product – rather than, say, a photocopy machine.

In terms of scope, the CPA has also not been expanded to regulate the purchase of digital content, despite the fact that millions of consumers worldwide conduct such transactions daily.Footnote 57 The existing definitions of ‘goods’ and ‘services’ under the CPA are incompatible for describing digital content, ie, data produced and supplied in digital form. Such content includes software; computer games; applications (‘apps’); ringtones; e-books; online journals; and digital media such as music, film, and television programmes.Footnote 58 Consumers can purchase digital content on a durable medium (eg, in a digital disc) or by downloading, streaming, or using a specific password to access these services. In addition, books and films that were previously exclusively available in a tangible form are now offered in digital formats (eg, e-books, Netflix), whereas digital goods with no visible precursor such as computer software and apps for smartphones (eg, game apps) have emerged. Given these novelties, the CPA requires reform to keep pace with technological advancements and provide comprehensive protection to domestic consumers in the modern e-commerce market. Otherwise, there will be legal uncertainties regarding consumer protection and rights in digital content transactions, including the right to be informed about the functionality of the digital content, the applicable remedies if the digital content are not of satisfactory quality or not as described, and the right to be protected against unfair T&Cs.

The Supplementary Status

The CPA is the primary legislation for consumer protection in Malaysia, but it is only supplemental to other laws governing contractual relations.Footnote 59 The Federal Court clarified in Ong Siew Hwa v UMW Toyota Motor Sdn Bhd that

[t]he effect of the words ‘without prejudice’ in section 2(4) of the CPA is that the application of the CPA is not to impair the force of any other law regulating contractual relations. The CPA does not override or repeal any other law on contractual relations … any other law regulating contractual relations continue to apply together with the CPA.Footnote 60

The supplementary nature of the CPA has defeated its purpose as Malaysia's main consumer protection legislation. It also indicates that the CPA is dependent on other laws regulating contracts (eg, SOGA) and is incapable of providing robust protection to consumers on its own. Decided cases show that the CPA will not override SOGA. Instead, they may apply synchronously when pari materia provisions are involved, such as the requirement that goods must be of satisfactory quality and match their description.Footnote 61 For instance, in Puncak Niaga (M) Sdn Bhd v NZ Wheels Sdn Bhd,Footnote 62 the defendant was found guilty of violating the statutory guarantees under section 32 of the CPA due to the subject matter (a car) being of substandard or unacceptable quality.Footnote 63 In regard to the remedies, the Court cited section 12(2) of SOGA, which allows the Plaintiff to terminate the contract,Footnote 64 and section 45 of the CPA to reject and return the goods.Footnote 65 Arguably, the Court would have reached the same decision without referring to SOGA as the CPA itself contains provisions that have the same effects as section 12(2) of SOGA.Footnote 66 Likewise, in Naza,Footnote 67 the trader was found guilty of violating section 32 of the CPA and section 16 of SOGA by failing to supply goods of acceptable quality that were reasonably fit for its intended purpose.Footnote 68 Regrettably, the Court failed to recognise section 33 of the CPA, which is analogous to section 16 of SOGA.

These decided cases indicate that Malaysian courts are sceptical of the CPA's ability to deal with consumer matters independently. It also reflects the courts’ reluctance to release themselves from the shackles of archaic law. The continued use of both Acts in consumer cases may result in legal uncertainty regarding which law shall prevail in the event of a conflict or overlap between the CPA and SOGA. It should be noted that SOGA is currently obsolete in the context of digital commerce. It was enacted in 1957 when the Federation of Malaya (as it was then) gained independence from the British Empire. Furthermore, SOGA is not a consumer protection-oriented piece of legislation. The principles therein are closely linked to the English law practices of the 18th and 19th centuries when the freedom of contract and application of the laissez-faire doctrine was prevalent. Therefore, it is unsurprising that SOGA contains provisions that directly contradict consumer expectations and interests.Footnote 69 In essence, SOGA is incapable of dealing with issues that arise in the modern and sophisticated 21st century society; thus, referring to that Act in consumer-related matters leads to injustice.

The Consumer Protection (Electronic Trade Transactions) Regulations 2012

The CPA was amended in 2007 to include e-commerce transactions within its purview. The amendment, however, does not impose a direct obligation on traders to provide consumers with information. The CPA later rectified this by introducing the Consumer Protection (Electronic Trade Transactions) Regulations 2012 (CPETTR) to regulate information disclosure in e-commerce. The CPETTR requires traders to display eight types of information, namely (i) the name of the trader, business or company; (ii) their registration number; (iii) contact details; (iv) descriptions of the main characteristics of the goods and services; (v) final prices (including any other costs such as transportation and taxes); (vi) the method of payment; (vii) the T&Cs and (viii) the estimated time of delivery.Footnote 70 The CPETTR contains no penalties for violations of its provisions, but general penalties under the CPA may apply.Footnote 71 The CPETTR also requires online marketplace operators to keep records for two years of the names, phone numbers, and addresses of traders who use their platform. Non-compliance will render the platforms liable and punishable under the CPA.Footnote 72 However, operators are not required to verify the authenticity of such information; thus, fraudulent traders can still use the platform for scamming purposes.

The CPETTR mandates traders to provide consumers with certain information, but it is silent on how that information should be delivered. In particular, it does not require information such as, for example, descriptions of the main characteristics of the goods or services and the T&Cs, to be made transparent and understandable to the average consumer. The CPETTR also consists of only five regulations,Footnote 73 which are arguably insufficient to assist consumers in making informed decisions. First, the CPETTR fails to appreciate other essential information, such as the dispute settlement process representing consumers’ right to seek redress. In Naza, Footnote 74 the Court recognised the importance of information on the right of redress and held that traders have a continuing obligation (even after the transaction has concluded) to provide consumers with sufficient information regarding available redress, ie, to reject or repair the goods. Second, traders need to keep consumers informed about the confidentiality of their data as this can boost consumers’ confidence and trust in e-commerce. Regrettably, the CPETTR does not require traders to inform consumers of how their data are processed and used, despite the fact that privacy-related issues are relatively high among online shoppers in Malaysia. A survey conducted to understand consumers’ characteristics and behaviours in e-commerce also revealed that most consumers (59.0 per cent) are concerned with how their data are treated, including their misuse for marketing purposes and browser tracking.Footnote 75

The Duty of Information Under English Law

English law has traditionally adopted a reluctant position towards the requirement of information duties.Footnote 76 However, following the implementation of EU law, the duty of information has become the most important regulatory instrument in the UK, mostly in consumer contracts.Footnote 77 The duty of information under English law is governed by the Consumer Contracts (Information, Cancellation and Additional Charges) Regulations 2013 (CCR), the Consumer Rights Act 2015 (CRA), and the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008 (CPUTR). Traders must provide the information specified under Schedule 2 of the CCR clearly and prominently prior to the consumer placing an order. It is based on this pre-contractual information that consumers can make an informed choice to be bound by the contract or otherwise. Information provided on a durable medium must also be legible.Footnote 78 The relevant information is deemed to have been made available when consumers can reasonably be expected to know how to access it.Footnote 79 The information required under the CCR is treated as a term,Footnote 80 and traders must prove that such information has been appropriately provided to consumers.Footnote 81 The CCR does not provide penalties for breaches, but consumers may claim under the CRA if traders fail to perform their information duty specified under the CCR.Footnote 82 Both pieces of legislation forbid any changes being made to the pre-contractual information unless expressly agreed between the contracting parties.Footnote 83 However, for digital content, traders may improve or add new features provided that it continues to match the original product description and conforms to the pre-contractual information previously disclosed.Footnote 84

The CPUTR, on the other hand, contains several provisions associated with information duty in commercial practices, namely (i) misleading actions and omissions and (ii) aggressive practices. Misleading actionsFootnote 85 concern the act of giving false information to consumers. Although the information provided may be factually correct, it can still lead to misleading actions if delivered deceptively. Meanwhile, traders are deemed to have committed misleading omissionsFootnote 86 if they (i) omit material information, (ii) hide material information, (iii) provide material information in an unclear, unintelligible, ambiguous, or untimely manner, and (iv) fail to identify the commercial intent unless it is already apparent from the context.Footnote 87 Material information refers to the information that the average consumer requires to make an informed transactional decision in the given context, and any informational requirement that applies to a commercial communication due to an obligation under EU law.Footnote 88 The CPUTR also forbids aggressive practices to shield consumers against physical or psychological pressure while making decisions.Footnote 89 A commercial practice is aggressive if it will significantly (or is likely to) impair consumers’ freedom of choice or conduct via harassment, coercion, or undue influence. The CPUTR does not expressly define harassment and coercion, but they may include physical and non-physical (eg, psychological) pressure.Footnote 90 Meanwhile, undue influence refers to the exploitation of power or position to pressure the consumer. It does not necessarily involve a threat or physical force as long as it significantly limits the consumer's freedom to make informed choices.

The Key Aspects under the CPUTR

Traders are deemed to have breached the CPUTR if their commercial practices cause (or are likely to cause) average consumers to make a transactional decision they would not have made otherwise.Footnote 91 However, the courts will also consider several aspects before deciding whether a commercial practice constitutes a breach.

Standards of Protection

English consumer law considers average and vulnerable consumers within its regulatory framework. The origins of the average consumer standard can be traced to the case of Gut Springenheide.Footnote 92 In that case, the CJEU adopted the opinion of the Advocate General, stating that the Court has always referred to the average, reasonably circumspect consumer as the benchmark of its consumer policy as opposed to the casual consumer.Footnote 93 From a legal perspective, the average consumer refers to the ‘reasonably well informed, reasonably observant and circumspect’ individual,Footnote 94 with each of these characteristics having its own significance. ‘Well-informed’ relates to ‘the level of knowledge the consumer is assumed to have’, ‘reasonably observant’ refers to ‘the intensity and absorption of information’, and being ‘circumspect’ is concerned with ‘the degree of critical attitude the consumer should have when processing information’.Footnote 95 In Office of Fair Trading v Purely Creative Ltd (henceforth ‘Purely Creative’),Footnote 96 the English Court took the view that the ‘average consumers’ reflects consumers ‘who take reasonable care of themselves, rather than the ignorant, the careless or the over-hasty consumer’.Footnote 97 Such an ‘average consumer’ is a hypothetical person and somewhat different from the legal tests used in other contexts, namely ‘the reasonable person’, ‘the fair-minded observer’, or ‘ordinary decent people’.Footnote 98 It is linked factually to a specific population of actual persons, namely, the consumers targeted by the relevant advertising.Footnote 99

An average consumer is a hypothetical person, or ‘legal construct’, created to balance between various competing interests, ie, the need to protect consumers, promote free trade in an openly competitive market, and establish a standard for national courts to apply.Footnote 100 The assessment is based on a qualitative judgement rather than a quantitative or statistical test. The courts may consider the generally presumed consumer's expectations without requiring an expert report or consumer survey.Footnote 101 Judges are not required to consider ‘the ignorant, the careless or the over-hasty’ consumers, as protecting such a demographic is not the purpose of the EU Directive on Unfair Commercial Practices (UCPD), which the CPUTR transposed.Footnote 102 The bar set is higher, with judges expected to consider only reasonably well-informed, observant, and circumspect consumers.Footnote 103 Primarily, the law only protects consumers who exert some effort in informing themselves and make good use of the information made available to them. As the proverb goes, vigilantibus non dormientibus iura succururunt, which can be translated as ‘the law comes to the assistance of those who are vigilant with their rights, and not those who sleep on their rights’.Footnote 104

Certain consumers are more vulnerable than the average consumer in e-commerce transactions, even when they are placed in a good position to make informed decisions. These consumers are vulnerable due to characteristics beyond their control that prevent them from understanding and utilising the disclosed information, such as mental or physical infirmity, age, or credulity in a manner that traders could reasonably be expected to foresee.Footnote 105 Consequently, the standard of a vulnerable consumer is established to guard traders against using their superior position to exploit consumers’ behaviour and deficiencies.Footnote 106 Consumers’ vulnerability, however, is not limited to uncontrollable personal characteristics. Consumers can also be vulnerable in a variety of interconnected contexts.Footnote 107 These vulnerabilities are classified as informational vulnerability (eg, information asymmetries), pressure vulnerability (eg, lack of confidence or knowledge), supply vulnerability (eg, where there is a situational monopoly in the market), redress vulnerability (eg, consumers have difficulties securing redress due to a lack of awareness of their rights or the settlement mechanisms available), and impact vulnerability (eg, where loss or harm impacts certain consumers disproportionately due to differences in their level of poverty or income).Footnote 108

Commercial Practices

The concept of ‘commercial practice’Footnote 109 that the CPUTR aims to govern is ‘concerned with systems rather than individual transactions’. The protection is mainly directed at commercial practices as a whole rather than to a specific commercial transaction.Footnote 110 In Nemzeti,Footnote 111 the CJEU held that the sole criterion for ‘commercial practices’ under Article 2(d) of the UCPD is that the trader's practice must be ‘directly connected with the promotion, sale or supply of a product to or from consumers’.Footnote 112 Meanwhile, in Warwickshire County Council v Halfords Autocentres Ltd (Competition and Market Authority Intervening) (henceforth ‘Warwickshire’),Footnote 113 the English Court clarified that the UCPD focuses on commercial practices targeted at consumers rather than ‘a consumer’.Footnote 114 Considering otherwise would do serious harm to the principal aim of the UCPD, ie, to achieve a high level of consumer protection.Footnote 115 The Court also held that a commercial practice might be established through a test purchase of a product (including a service) that is generally promoted to and intended for purchase by consumers, even if the purchaser may not himself be a consumer (eg, a trading standards officer pretending to be a consumer). The English Court has sufficient confidence in its interpretation, which seems clear when a properly purposive approach is taken; thus, it denied the request for a referral to the CJEU.Footnote 116

Transactional Decisions

A ‘transactional decision’Footnote 117 does not exclusively refer to the decision to enter into a legally binding contract. It encompasses a wide range of potential consumer decisions that have been or may be taken by the average consumer concerning the product.Footnote 118 In the e-commerce environment, ‘transactional decisions’ may include the decision to visit a trader's website first, rather than its competitors, and navigate to another page on a website to view further content.Footnote 119 A ‘transactional decision’ also includes the decision to purchase a product and other related decisions. In Trento,Footnote 120 the consumer claimed that a supermarket advertisement was misleading because a laptop advertised at a promotional price was not available at the store during his visit. The question raised before the CJEU was whether the consumer's decision to enter the store constituted a ‘transactional decision’ distinct from the decision to purchase the laptop. The CJEU confirmed the broad interpretation of ‘transactional decision’ to include the purchase of the laptop and other directly related decisions such as entering the shop. Footnote 121 However, it is for the national court to determine, on a case-by-case basis, whether the information disclosed is sufficient to enable consumers to make informed transactional decisions.Footnote 122

In Purely Creative,Footnote 123 the Court noted that any decision taken by consumers with an economic consequence was a transactional decision, even if it was simply deciding between doing nothing and responding to promotions by posting a letter, making a premium rate call, or sending a text message.Footnote 124 The Court explained that the applicable test for the phrase ‘causes or is likely to cause’ is equivalent to the English standard of the balance of probabilities, whereas the phrase ‘to take a transactional decision, he would not have taken otherwise’ suggests a sine qua non test, namely, whether but for the relevant misleading action or omission of the trader, the average consumer would have made a different decision.Footnote 125 The Court also asserted that the causation test for misleading acts and omissions is the same and must be assessed simultaneously; an independent assessment could erroneously allow communication to escape from being classified as an infringement containing misleading acts and omissions – none of which would separately satisfy the causation test unless combined.Footnote 126

Materiality of Information

Traders are not required to disclose all the available information they possess, but only that which is material for consumers to make informed decisions. The purpose of information disclosure is primarily to protect less sophisticated consumers who may not understand what information is relevant to make wise choices. It is to these consumers’ needs that information disclosure and materiality of information should be tailored.Footnote 127 In Purely Creative,Footnote 128 the Court emphasised the concept of ‘need’ to clarify the requirements for ‘material information’ under the CPUTR. It is not a matter of whether the omitted information would assist the consumer or be relevant for them, but whether that information is necessary for the average consumer to make informed decisions.Footnote 129 Whereas the type of information required and its significance varies by consumer,Footnote 130 it is for the Court to determine what constitutes material information in light of consumers’ needs.Footnote 131 In the latter case of Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills v PLT Anti-Marketing Ltd,Footnote 132 the Court provided further clarification on the ‘need’ test, holding that consumers’ need for material information is contingent upon the availability of the information and whether consumers must obtain such information from the trader rather than finding it out themselves. The Court stated that inward-facing information (eg, about the trader and their products) might only be available from the trader. In contrast, information about alternative or competing products is generally available in the marketplace. It is restricted only by the extent to which an individual consumer desires to obtain it prior to making final decisions. In this case, the Court holds a general presumption that average consumers, ie, those who are reasonably well-informed, reasonably observant, and circumspect, would conduct their own research on alternative or competing products rather than relying on the trader for such information.Footnote 133

Comparisons of Malaysia (The CPA) and English Law

The CPA protects consumers in both offline and online transactions. Although the Act forbids traders from making false or misleading representations about goods and services, it does not directly compel traders to furnish consumers with material information. The CPETTR was then introduced via the CPA to govern information disclosure in e-commerce. However, the information required of traders is limited and insufficient to enable consumers to make informed decisions. Both the CPA and CPETTR also underestimate the importance of providing consumers with quality information to assist them in making efficient choices. In particular, there are no provisions mandating information to be provided in a transparent, prominent, or understandable manner. On the other side, English law recognises three distinct types of contract (ie, on-premises, off-premises, and distance contracts), each requiring a slightly different set of information. The duty of disclosure is a cornerstone of English consumer law, imposed on the premise that only an informed consumer is capable of acting rationally and making prudent transactional choices. The CCR and the CRA explicitly require traders to provide a set of material information in a clear and comprehensible manner prior to a consumer placing an order, whereas the CPUTR prohibits traders from engaging in three types of unfair practices related to information. These practices are misleading actions (eg, providing false information), misleading omissions (eg, omitting or hiding material information), and aggressive practices (eg, using harassment, coercion, and undue influence to impair consumers’ freedom of choice to make purchase decisions).

The CPA also lacks a specific benchmark for assessing breaches of its provisions. The Act merely states that any conduct and representation that ‘led consumers into error’ is a form of unfair practice.Footnote 134 In contrast, as noted above, English law uses the average consumer as the standard of expected consumers’ behaviour, characterised as a reasonably well-informed, reasonably observant, and circumspect consumer.Footnote 135 The average consumer also refers to consumers who take reasonable care of themselves, as opposed to the ignorant, careless, and over-hasty consumer.Footnote 136 In addition, English law recognises that some consumers are vulnerable due to characteristics beyond their control. Therefore, English law uses the standard of a vulnerable consumer to prevent traders from using their superior position to exploit consumers’ behaviour and vulnerabilities. English law also emphasises the importance of providing information in a clear, intelligible, and timely manner so that consumers can reasonably be expected to understand how to assess it.Footnote 137 If the information is in a durable medium (eg, email), it must be legible. Furthermore, English law requires contracts to be transparentFootnote 138 and prominent,Footnote 139 especially if the T&Cs may be detrimental to consumers.Footnote 140

The CPA only applies to the sale of goods and services, whereas it is silent on transactions involving digital content. In contrast, English consumer law has expanded its scope of protection to digital content via the introduction of the CRA in 2015. The Act has separate chapters to deal with goods, services, and digital contentFootnote 141 as each requires a slightly different set of information. Such an arrangement also enables the CRA and enforcers to concentrate on consumers’ diverse needs according to the products purchased. Lastly, several key terms (eg, ‘trade’, ‘goods’, ‘consumer’) in the CPA are vague and outdated. Since its introduction two decades ago, no revisions have been made, which has rendered the CPA outdated compared to the current state of e-commerce. Consequently, identifying the extent to which the CPA applies to private sales, auction-type websites, digital content, and consumers buying goods for dual purposes (private and business purposes) is legally challenging. By comparison, key definitions such as ‘trader’, ‘consumer’, and ‘business’ under English law are more straightforward and precise than the interpretations under the CPA. The CRA also defines goods and digital contents separately while specifying the types of regulated sales transactions that fall under its purview.

Proposed Legal Reforms

Introduce a Duty of Information

The increasing number of choices available in the e-commerce marketplace can cause consumers to feel overwhelmed and prone to making decisions inconsistent with their preferences. Consumers who are not fully informed are more likely to make purchases that do not suit their needs, resulting in disappointment and inefficient market transactions.Footnote 142 On the other hand, traders are not entirely trustworthy as they tend to exaggerate claims while promoting and highlighting their products’ positive attributes.Footnote 143 As such, legislation against misleading or deceptive advertising is vital to enhance the likelihood of consumers receiving quality information while protecting them from misinformation.Footnote 144 In view of this, the CPA should revise existing provisions or introduce specific information duty requirements to assist consumers in making informed decisions. Imposing disclosure duties will level the inequality of bargaining power and help ‘lift’ the consumer to be on a par with the trader.Footnote 145 As demonstrated under English law, there are several aspects for lawmakers to consider when revising the CPA and introducing information duty. First, the CPA can make businesses directly accountable for providing material information to assist consumers in making informed decisions. Otherwise, omitting and hiding material information can be regarded as unfair practice in the form of misleading omissions. Second, it should be forbidden to provide false information or present the information in any manner likely to deceive consumers. Businesses that engage in such commercial practices can be held liable for misleading actions. Third, the CPA should forbid businesses from using aggressive practices such as harassment, coercion, or undue influence when delivering information as these practices can impair consumers’ freedom of choice. Aggressive practices also include exaggerating claims to stimulate fearful reactions concerning the nature and risks that consumers (or their families) may be exposed to if the consumer does not purchase the product.

The CPA itself should determine what information is considered material rather than letting traders decide which information they would like to give consumers. There is no consensus on what kind of information improves consumers’ decision-making, the appropriate form of presenting information, and how much information is required.Footnote 146 From the English law perspective, the materiality of information is contextual. It depends on the consumer's ‘need’ for the information to make informed decisions,Footnote 147 which must be balanced with the availability of the information. If such information is obtainable elsewhere in the market, an average consumer who is reasonably well informed, reasonably observant, and circumspect is expected to search for that information independently without waiting for the trader to provide it. However, information alone is insufficient to empower consumers to make informed choices. Behavioural insights suggest that consumers are not always rational and are prone to biases, particularly when presented with information that exceeds their ability to process. Due to these ‘cognitive limitations’, consumers tend to make decisions based on incomplete or insignificant information highlighted by traders.Footnote 148 Therefore, a regulatory approach to disclosure should address the contents and quality of the information delivered in light of consumers’ bounded rationality and the limits of their ability to process information.Footnote 149 Otherwise, traders may offer information on their website in ways that benefit them while making it hard for consumers to comprehend. The CPA, therefore, should mandate that information must be transparent, readable, and understandable to consumers, ie, avoiding small print, compact text formats, and complicated terminology. The information should also be prominently displayed, concise, and well-organised.Footnote 150 Alternatively, the CPA could refer to the ACCURATE information framework proposed herein as the focal point for establishing the information duty.

Introducing a statutory duty of information has novelty value to the CPA. To facilitate smooth legislative reform, the CPA can guide relevant stakeholders on what constitutes material information and provide examples of commercial practices related to information duty. To illustrate, Schedule 2 of the CCR under English law offers a detailed set of information that businesses must provide before consumers make their final choices. In a distance contract, for instance, the required information includes the details of the trader and their products,Footnote 151 price-related matters (eg, final costs, additional charges, manner of calculating the price and the arrangements of payments and delivery),Footnote 152 procedures for settling a dispute, refunds, and cancellation rights.Footnote 153 The information should also include a reminder that the trader is legally bound to supply goods according to the sales contract.Footnote 154 Such a reminder can increase consumers’ confidence to transact via e-commerce while raising awareness of their statutory rights. English consumer law is also flexible in its information requirements. It recognises that the nature of the transactions will dictate what information is material, which is assessed on a case-by-case basis.Footnote 155

Information duty is futile in the absence of a benchmark to evaluate and assess its compliance. Furthermore, consumers respond to information differently; some may be reasonable, intelligent, and act sensibly, whereas others are gullible and careless with the information provided. As such, the CPA should establish a framework for evaluating and assessing the overall adherence to the information duty and its other provisions, eg, whether they will be assessed against the average, reasonable, or vulnerable consumer. English consumer law, for instance, uses the average consumer as the primary benchmark and vulnerable consumer as the subsidiary benchmark to assess compliance. The CPA could consider a similar parameter to balance the rights of market players. A defined framework of assessment will clarify the acceptable standard of information duty businesses must adhere to while protecting their interests when consumers do not use the information provided wisely. Essentially, laws can only assist consumers in making wise and informed decisions by imposing a duty on traders to provide high-quality information. Consumers, however, must also be reasonably prudent and observant in leveraging the information provided to make informed choices.

Modernise the Key Definitions

The CPA should update existing key provisions to reflect current developments in e-commerce transactions. First, the CPA must define who qualifies as a trader within the meaning of ‘acting in trade’, ie, whether they are a professional trader, a private trader, or both. Consumers are, likewise, exposed to information asymmetry in private sales. They are unable to inspect the goods prior to completing the purchase, hence justifying the need for private traders to have the same disclosure obligation as professional traders. However, if the CPA does not apply to private traders, it should expressly exclude private transactions from its ambit. It could provide guidance for distinguishing private and commercial sales by offering examples of individuals acting ‘in trade’. For instance, if Kokone sells her son's clothes that he has outgrown, she is not deemed ‘in trade’ as the garments were initially purchased for personal use. Similarly, if Kokone purchases books regularly, reads them, and sells them online, she is not ‘in trade’ as the books were purchased for personal use. However, if Kokone makes jewellery at home and sells them over social media, she is ‘in trade’ because she made the jewellery items with the intention of selling them. The CPA should also require traders to identify themselves when advertising goods or services for sale on the internet. For example, traders must inform potential purchasers that they are ‘acting in trade’ within the context of the CPA (or similar identification). The information enables prospective buyers to determine with whom they are dealing and be informed whether the CPA will govern the risks associated with the transactions. Such identification will also ensure that professional traders do not masquerade as private traders to avoid liability should the latter fall outside the remits of the CPA. Enforcing these requirements, however, can be challenging in e-commerce. Hundreds, if not thousands, of online transactions are performed daily, making it hard to supervise each sale. In addition, potential buyers may be uninterested in verifying with whom they transact or whether the traders have adequately identified themselves as a ‘trader’ within the meaning of the CPA.

Second, the archaic definition of ‘consumer’ should be revised to reflect modern commercial transactions while also clarifying the nature of the actual ‘consumer’ that the CPA aimed to protect. The CPA presently defines ‘consumer’ as a person who ‘acquires or uses goods or services of a kind ordinarily acquired for personal, domestic and household purpose, use or consumption’.Footnote 156 Using these criteria to determine whether a consumer may rely on the CPA can lead to ambiguity. In practice, many consumers nowadays purchase goods (eg, a smartphone or laptop) for both business and personal usage. By comparison, English law uses a much more explicit description of ‘consumer’, which refers to ‘an individual acting for purposes that are wholly or mainly outside that individual's trade, business, craft or profession’.Footnote 157 For example, Zadie buys a kettle for her home. If she works from home one day a week and uses the kettle when working from home, Zadie is still a consumer under the CRA. In contrast, a sole trader operating from a private dwelling who buys a printer which is used for business 95 per cent of the time is unlikely to be considered a ‘consumer’. That sole trader would have to rely on other legislation such as the Sale of Goods Act 1979 for protections concerning the quality of the goods.Footnote 158 However, it is for the trader to prove that an individual was not acting wholly or mainly outside their trade, business, craft, or profession.Footnote 159

Third, the CPA must be transparent about its relevance in a variety of settings. For example, it does not explicitly include or exclude auction sites and charity sales from its remit. Therefore, it is debatable whether consumers buying from traders through these platforms have equivalent rights to those buying from professional traders on a general e-commerce website. Arguably, consumers rarely assert their rights when buying on auction platforms, either because they are unaware if they have any rights or they presume that purchases through an auction website were made at their own risk.Footnote 160 In addition, consumers may be hesitant to demand their legal rights against charity shops due to the fact that they sell goods for charitable purposes. However, if consumers do not raise concerns about these types of businesses, lawmakers may not see the need for laws to regulate them in Malaysia.

Re-evaluate the Scope of the CPA in Modern E-Commerce Transactions

The CPA needs to be expanded to govern digital content so that consumers are optimally protected in the challenging and ever-changing e-commerce market. Presently, the CPA has no provisions dealing with digital content. Existing provisions are also incompatible with digital content transactions as they are primarily concerned with physical products (eg, cancellation rights and rights to demand, repair, or return a product). Unlike physical goods, it is frequently difficult, if not impossible, for consumers to foresee certain features of digital contents (eg, game software) prior to experiencing them. In addition, digital content is often accompanied by various complicated technical jargon that can be difficult for consumers to comprehend. Digital content is also subject to specific licensing requirements that govern its functionality and usability. These complexities, therefore, justify the importance of greater transparency and high-quality information related to digital content purchases.Footnote 161 In comparison, English law via the CRA defines ‘digital content’ as data produced and supplied in digital form.Footnote 162 The CRA also has specific provisions that deal with digital content transactions.Footnote 163 The CPA can follow suit by either amending the current definition of ‘goods’ to include digital content or introducing provisions that explicitly define and address digital content transactions. These reforms will clarify consumers’ rights when purchasing digital content, such as the right to information and protection against unfair T&Cs, while also reflecting the current landscape of the digital market.

Re-examine the Supplementary Status of the CPA

The CPA was the first Act enacted in 1999 that exclusively addresses consumers affairs in Malaysia. However, it operates in tandem with other laws governing contractual relations, even in consumer-related matters. Legislators may have reservations about its capabilities, which explains why the CPA was introduced as a supplementary to other laws. Arguably, the supplementary status of the CPA has undermined its credibility as the primary consumer protection legislation in Malaysia. Instead, it should function independently in matters involving consumer issues without operating as a supplement to other laws. Furthermore, the CPA has been law for twenty years, so it should be self-sufficient in its provision of robust protection to consumers by now. In essence, lawmakers need to revise the supplementary status of the CPA and consider making it a stand-alone legislation. If a matter in dispute involves consumer contracts, the CPA should take precedence over other legislation. Otherwise, it is pointless for the CPA to be the leading consumer protection law in Malaysia if lawmakers are not confident in its effectiveness alone.

Law Reform and Existing Consumer Protection Regimes

Other legislations in Malaysia also regulate the dissemination of information to consumers, such as the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998 (CMA) and the Trade Descriptions Act 2011 (TDA). Reforming the CPA to adopt the duty of information is unlikely to impede the CMA and TDA from performing their respective functions. Instead, these Acts could operate in tandem to ensure consumers receive optimal protection in Malaysia. These are discussed in detail below.

The CPA and CMA

The CMA is under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Communications and Multimedia Malaysia. It was enacted to govern the convergent communication and multimedia industries and incidental matters.Footnote 164 It focuses on the communications marketFootnote 165 and digitised contentFootnote 166 and only applies to network facilitiesFootnote 167 providers, network serviceFootnote 168 providers, application service providers, and contentFootnote 169 applications services. These parties are required to deal reasonably with consumers and adequately address consumer complaints in the telecommunications industry.Footnote 170 The CMA defines ‘communication’ as any communication between individuals, things, or persons and things, whether by sound, data, text, visual images, signals, or any other form or combination of those forms.Footnote 171 Such ‘communication’ may also include ‘telecommunication’.Footnote 172 The CMA does not define ‘telecommunication’; however, in its ordinary meaning, ‘telecommunication’ refers to ‘the telegraphic or telephonic communication of audio, video or digital information over a distance by means of radio waves, optical signals, etc., or along a transmission line’.Footnote 173

In Telekom Malaysia Bhd v Tribunal Tuntutan Pengguna & Anor (‘Telekom’),Footnote 174 the Court held that section 2(2)(g) of the CPA expressly excluded trade transactions by electronic means from its ambit.Footnote 175 Therefore, the Tribunal for Consumer Claims lacked jurisdiction to hear a dispute arising from the telecommunications industry. Section 2(2)(g) of the CPA was repealed in 2007 to include electronic transactions within its remit. However, the CPA and CMA were enacted to govern different industries, hence the removal of section 2(2)(g) of the CPA does not affect the CMA from performing its core objectives. As held in Telekom, the CMA was clearly enacted to protect consumers in the telecommunications industry. In contrast, the CPA was not meant to apply to the hearing of a dispute arising from the same industry.Footnote 176 Furthermore, the CPA is under the jurisdiction of a different Ministry, ie, the Ministry of Domestic Trade and Consumer Affairs, and was enacted to safeguard consumers in offline and online transactions involving the sale of goods and services.Footnote 177 The CPA also concerns consumers who bought products for personal use; traders who supplied the products; and the manufacturer who assembled, produced, and processed these products.Footnote 178

In addition, the CMA has its own Consumer Code of Practice that addresses the information, advertising, and representation of services, rates and performance to customers.Footnote 179 The Code contains requirementsFootnote 180 comparable to those proposed under the ACCURATE information framework. For instance, it requires that consumers be given sufficient, accurate, trustworthy, and up-to-date information in plain and straightforward language, with the use of technical jargon only when necessary. The information may be delivered verbally, in writing, displayed at the premises or on websites, or distributed electronically or through other mass media available to consumers. Disclaimers in advertising must be understandable, clear, and reasonably visible. Consumers must be able to distinguish in advertisements between contractual T&Cs, marketing, and promotional activities. Despite these parallels, reforming the CPA to introduce the ACCURATE information framework will not conflict with the Code. Both aim to empower consumers with information, but they concern different market players and subject matters. The Code applies solely to Licensed Service Providers and non-Licensed Service Providers who are members of the consumer forumFootnote 181 in the telecommunications industry. In contrast, the ACCURATE framework proposed under the CPA is directed at traders, manufacturers, and those involved in advertising or marketing goods and services to consumers in both offline and online settings. Arguably, however, the Code and the ACCURATE framework can work in tandem to provide optimal protection to consumers without jeopardising their respective functions.

The CPA and TDA

The TDA was introduced to promote ethical trade practices by prohibiting false trade descriptions and false or misleading statements, conduct, and practices related to the supply of goods and services.Footnote 182 The TDA resembles the CPA in many ways. First, both pieces of legislation prohibit false and misleading statements regarding goods and services.Footnote 183 Second, the aspects considered in assessing false and misleading representations of goods,Footnote 184 services,Footnote 185 and priceFootnote 186 are practically identical. Third, the TDA closely follows the CPA concerning liability for making an advertisement containing false or misleading information,Footnote 187 and both provide similar defences for a person charged with the specified offences.Footnote 188 Fourth, both statutes offer rewards to whistleblowers who give information that leads to the conviction of offenders. The reward is in the form of monetary payment that is subtracted from the fine in an amount determined by the Court.Footnote 189 However, the CPA and TDA provide different mechanisms for addressing violations of their provisions. Under the CPA, consumers may seek redress from the Tribunal for Consumer Claims if it concerns the infringement of their rights.Footnote 190 In comparison, for breaches of the TDA, an action cannot be initiated directly against the relevant traders. Instead, a complaint must be submitted to the Assistant Controller for further investigation,Footnote 191 and no prosecution under the TDA can be instituted without the consent of the Public Prosecutor.Footnote 192 Therefore, an apparent downside of the TDA is that it has a relatively stringent requirement to initiate an action compared to the CPA.

The TDA also seems to correspond better with modern e-commerce transactions than the CPA in some respects. For instance, the TDA defines ‘goods’ in a broad sense by including all kinds of moveable property.Footnote 193 Although digital content is typically intangible, it may conform to the definition of ‘goods’ under the TDA as moveable property. However, for legal clarity, a proper definition of digital content must be included in Malaysia's existing consumer protection regime. The TDA also governs trade descriptions concerned with, inter alia, the physical or technological characteristics of the goods,Footnote 194 whereas this requirement is not specified in the CPA. Regrettably, the TDA does not explain what descriptions correspond to technological features. The meaning varies based on one's viewpoint and the context where the phrase ‘technological’ is used. For instance, it can describe the scientific elements of a product, such as the features and specifications of laptops (eg, processor speed, screen resolution, and wireless capability). Arguably, ‘technological characteristics’ can be used to describe the features of digital content. For example, device compatibility and graphics quality can be included in the descriptions of technological characteristics for software downloaded to a computer or mobile phone. However, in the absence of statutory explanations and given the limited judicial interpretations, one can only speculate on the applicability of the TDA to descriptions of digital content.

Revising the CPA is unlikely to affect the TDA as both Acts are directed at different individuals. The CPA considers conduct or representations as false and misleading if they lead a consumer, ie, an individual who purchases goods or services for personal purposes, into error.Footnote 195 In contrast, the TDA considers conduct or statements as false and misleading if they can lead any person into error.Footnote 196 Unlike the CPA, offences under the TDA are not restricted to interactions between a purchaser (consumer) and trader.Footnote 197 In particular, the TDA makes no explicit reference to ‘consumer’ in its provisions. The phrase any person Footnote 198 implies that anyone, not just the purchaser or those engaged with traders, can file a complaint with the authority if they believe that the trader's conduct is capable of leading them into error. Given these distinctions, reforming the CPA to embrace the duty of information and the ACCURATE framework is unlikely to impair the TDA from performing its primary objectives. Instead, the TDA should consider the proposed ACCURATE framework when determining the violation of its provisions to ensure legal consistencies within Malaysia's consumer protection framework.

Conclusion

This article examined the effectiveness of the CPA in ensuring that consumers can make informed decisions and that their interests are adequately protected in modern e-commerce. The outcomes of the doctrinal analysis revealed that the CPA does not emphasise the duty of traders to provide consumers with information. The Act is likewise limited in its scope and outdated compared to the current landscape of the e-commerce market. Consequently, consumers may have difficulty making informed decisions while their legal rights under the CPA remain ambiguous. Archaic laws are unsuitable for addressing contemporary legal issues. Thus, in a quest to modernise the CPA, this article explored English consumer protection law, which features advanced consumer regulatory regimes enriched by EU law. English law is also descended from a legal system fairly similar to Malaysia, namely the common law tradition. Accordingly, it serves as a valuable baseline for assessing the progress of Malaysian consumer protection law in the period since the country gained independence from the UK. English law initially adopted a reluctant position towards information duties. However, such obligation is now a cornerstone of English consumer law following the influence of EU law, demonstrating the feasibility of legal metamorphosis. The comparative analysis also provided new insights and inspiration for this article in developing the framework of ACCURATE information that the CPA can use as a focal point for regulatory debates regarding the implementation of information duty. In addition, this article identified aspects of the CPA that require reform, either via legal transplants or appropriate modifications. Reforms include revising outdated provisions, broadening the scope to regulate digital content, and reviewing the status of the CPA, which is currently supplementary despite being the primary consumer legislation in Malaysia.

Although these findings may be of interest to Malaysian lawmakers, the costs of rule formulation, enforcement, and compliance must be considered prior to reforming the CPA. Such an evaluation will enable lawmakers to quantify the potential costs and possible consequences while avoiding overly expensive rules. The rule formulation and enforcement costs refer to the funds and resources available prior to implementing the proposed reforms. Resources include skilled and expert professionals responsible for gathering the relevant data and analysing the appropriate measures to regulate the digital market. Transactions in e-commerce also require consistent monitoring as they are constantly evolving. Therefore, a specific enforcement body is essential for monitoring developments in e-commerce while ensuring that provisions of the CPA are complied with and remain relevant. Consumers are unlikely to act against traders who have violated their statutory rights because it is costly and time-consuming, They also lack the confidence and legal knowledge to do so, leaving public authorities with the incentives to pursue these traders. Adequate resources and funds are, therefore, highly crucial in ensuring successful enforcement. Otherwise, reforming the CPA can be challenging, let alone enforcing the proposed regulatory strategies.

On the flipside, compliance costs must also be considered. These refer to the expenses incurred by market participants, ie, businesses and consumers, in complying with the proposed reforms. Traders may refuse to provide ACCURATE information if it is costly and adversely affects their products’ marketability. Traders may also need to hire legal experts to draft their T&Cs to conform with the specified legal standard. If traders experience high compliance costs, such costs might be transferred to consumers in the form of price increases. To avoid such issues, lawmakers will have to achieve an equilibrium between the need to protect consumers’ interests and the costs incurred by traders. Meanwhile, compliance costs for consumers include, but are not limited to, their interest and willingness to spend time searching and processing information. When gathering and processing information becomes prohibitively expensive, some consumers will cease searching or gather less information. They are also unlikely to read T&Cs thoroughly if traders increase the level of complexity. Consumers, however, have a responsibility to overcome these compliance costs and their bounded rationality. Rather than depending entirely on the law to safeguard their interests, consumers should educate themselves about their statutory rights to minimise the risk of being manipulated by unscrupulous traders. Furthermore, due to its unique borderless nature, authorities do not have absolute control over the e-commerce environment. Therefore, consumers must be savvy by empowering themselves with their statutory rights to keep pace with sophisticated marketing strategies.