The transition from silent to synchronized sound film was one of the most dramatic transformations in cinema’s history, radically changing the technology, practices and aesthetics of filmmaking in under a decade. This period has long been a subject of fascination for filmmakers, scholars and fans alike. From Singin’ in the Rain (1952) to The Artist (2011), the film industry itself has shaped a narrative that remains dominant in the popular imagination. The simplistic teleological view of the transition – and the inevitability of the evolution of sound towards classical Hollywood sound practices that it implies – has been revised and corrected by numerous scholars (Bordwell et al. Reference Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson1985; Gomery Reference Gomery2005). But a narrative of continuity that posits its own idealized teleology is just as much a distortion as one founded on total rupture, as Gomery, for instance, simply replaces the great men of filmmaking with the great men of finance, and Bordwell, akin to André Bazin’s myth of total cinema (Bazin Reference Bazin and Gray2005 [1967], 17–22), draws the idea of a sound film from a transhistorical idea of cinema itself, though what Bazin links to deep focus and long takes, Bordwell links to editing.

While the film industry’s transition was swift, it was neither crisis-free nor particularly systematic, especially with respect to technology and aesthetics. Donald Crafton notes that the transition to sound was ‘partly rational and partly confused’ (Reference Crafton1997, 4), and Michael Slowik adds that ‘sound strategies differed from film to film’, which resulted in ‘a startling array of diverse and often conflicting practices’ (Reference Slowik2014, 13). The relationships between film and sound (particularly music) had to be negotiated, and the introduction of synchronized sound prompted a range of audiovisual approaches and opinions about the new technology and its aesthetic implications. The ‘transition’ period was therefore a time of pronounced experimentation but also of surprisingly rapid aesthetic and economic codification within the film industry. On the one hand, the range of reactions and approaches to sound in different national contexts points to the contested nature of synchronized sound during the transition era and its implications for cinema as art, industry and entertainment. On the other, an international consensus, led by the American industry, had formed around proper sound practices, the so-called classical style, by the late 1930s. Roger Manvell and John Huntley, for instance, argue that filmmakers had by 1935 mastered the soundtrack sufficiently to the point that they ‘had become fully aware of the dramatic powers of sound’ (Reference Manvell and Huntley1957, 59). This emerging consensus allowed for considerable variation in national practices but set limits and high technical standards for films that aimed for international distribution.

Early History of Sound Film: Experimentation and Development (1900‒1925)

A diversity of sound and music practices characterized the era of early cinema (Altman Reference Altman2004, 119–288). As film found a more secure footing as a medium of entertainment and narrative film increasingly dominated the market, musical accompaniment became more closely connected to the film. The importance of musical accompaniment – ‘playing the pictures’ – consequently increased with this codification of narrative filmmaking technique, as a means of representing and reflecting the narrative. Although the practice of ‘playing the pictures’ was quite varied, it was structured around three general principles: synchronization, subjugation and continuity.

Synchronization involved fitting the music to the story, through mood, recurring motifs and catching details pertinent to the narrative. Mood related music to dramatic setting, usually at the level of the scene. Motif entailed a non-contiguous musical recurrence linked to a narratively important character, object or idea and topically inflected to reflect the action. Catching the details, which would evolve into ‘mickey-mousing’ in the sound era, involved exaggerated sound or music and an exceptionally close timing with the image, as in the vaudeville practice of accompanying slapstick comedy with intentionally incongruous sound. Subjugation required that music be selected to support the story and that music should never draw attention to itself at the expense of the story. This principle ensured that the accompaniment was played to the film rather than to the audience. Through subjugation, music could also serve to mould the audience’s own absorption in the narrative. The musical continuity of the accompaniment likewise encouraged spectators to accept and invest in the film’s narrative continuity (Buhler Reference Buhler, Gilman and Joe2010).

These three principles structured the three dominant modalities of ‘playing the picture’ during the silent era: compilation, improvisation and special scores. Compiled scores, whether based on circulated cue sheets or assembled by a theatre’s musical staff, were especially common, and a whole division of the music-publishing industry was organized to support this concept. The publishing firms not only supplied original music composed to accompany conventional moods, but they also offered catalogues and anthologies of music indexed by mood and topic to facilitate compilation scoring. The most famous American anthology was Ernö Rapée’s Motion Picture Moods for Pianists and Organists (Reference Rapée1924). Compilation was the preferred practice of accompaniment in the early years and, even in the 1920s, it remained the basic method for orchestral performance.

Improvisation was the accompaniment practice over which the film industry had the least control. Typically performed on a piano or organ, an improvised score was left to musicians to invent on the fly. As with compiled scores, the improvisation would introduce shifts in musical style to fit the need of any given scene, and improvisers would commonly work well-known tunes into their accompaniments. But the results varied greatly depending on the musicians in charge, resulting in the stereotype of the inept small-town pianist. Variable accompaniment practices left to the devices of local musicians were seen, according to Tim Anderson, as ‘“problems” that needed to be solved’, as the film industry moved towards greater standardization of exhibition in the 1910s (Reference Anderson1997, 5).

Some ‘special’ scores – scores created and distributed to go with specific films – began to appear in America in the 1910s, and increased in frequency and prominence in the 1920s. Notable special scores for American films include Joseph Carl Breil’s for Birth of a Nation (1915), Mortimer Wilson’s for The Thief of Bagdad (1924), William Axt’s and David Mendoza’s for The Big Parade (1925), and J. S. Zamecnik’s for Wings (1927). The increased prevalence of special scores was part of the film industry’s attempts to standardize and systematize musical practices. Over the course of the 1910s and 1920s, movie exhibition became increasingly stratified, and film music reflected this disparity: many urban deluxe theatres devoted considerable resources to maintaining large music libraries and musical personnel, including substantial orchestras and Wurlitzer organs, but small town theatres could hardly afford to do the same, as Vachel Lindsay, among others, ruefully noted (Reference Lindsay1916, 189–97).

In Europe, cinema occupied a somewhat different cultural position, alongside its commercial and popular associations. In France, Camille Saint-Saëns composed a score in 1908 for L’Assassinat du Duc de Guise, the first production of the ‘Film d’Art’ company, which was formed with the idea of making prestige pictures that might attract a higher class of patron (Marks Reference Marks1997, 50–61). Other French composers soon demonstrated an interest in composing for cinema, most notably Erik Satie and members of Les Six. In the 1920s, surrealist artists and writers not only took inspiration from the cinema but also worked with it seriously as a medium. Additionally, ciné-clubs and journals devoted to filmmaking indicate film’s potential as high art in the eyes of French filmmakers and musicians. In Germany, too, silent film had a close relationship to modernist movements in the plastic arts, and original film scores to accompany these artistic films were quite common. Mostly original film scores were composed for such well-known expressionist films as Robert Wiene’s Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (1920; score by Giuseppe Becce) and Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927; score by Gottfried Huppertz). The Viennese-born composer Edmund Meisel composed scores for German and Soviet films, including Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925), one of the most influential Soviet films of the silent era (Ford Reference Ford2011). Additionally, German artists like Oskar Fischinger experimented in ‘visual music’, further linking music and the moving image through abstract visual art (Moritz Reference Moritz2004; Cooke Reference Cooke2008, 58).

European film-music practices were as diverse as they were in America, and accompaniment followed the same three principles of synchronization, subjugation and continuity, and was also organized by the same three modalities of compilation, improvisation and original score. In Germany, compilation was particularly formalized, with original compositions, anthologies and catalogues indexed by topics and moods along American lines. (Becce’s volumes of Kinothek music were especially popular.) In 1927, Hans Erdmann, Becce and Ludwig Brav published the Allgemeines Handbuch der Film-Musik, a two-volume compendium of silent-film dramaturgy, hermeneutic theory of music and systematic sorting of musical works according to the needs of a music director of a cinema. Although it appeared late in the silent era and so never had a chance to establish its principles in theatres, the Handbuch does represent a particularly well-formulated theory of mature silent-film practice (Fuchs Reference Fuchs, Tieber and Windisch2014). Its basic idea of a musical dramaturgy, related to traditional forms of theatre but with specific problems unique to film, also seems to have been absorbed by the composers of sound film as they worked to establish a place for music on the soundtrack.

Ultimately, the American studio system, with its drive towards standardization in order to control both labour costs and quality, found it increasingly advantageous to pursue experiments in synchronizing film with recorded sound. Filmmakers and inventors had been interested in mechanically linking sound and music with image since the earliest days of cinema. Thomas Edison, for instance, always claimed his inspiration for the motion picture had been the phonograph, ‘to do for the eye what the phonograph does for the ear’ (Edison Reference Edison1888). In 1895, he developed the Kinetophone, joining his Kinetoscope with a phonograph, and in 1913 his firm released a second version of the Kinetophone that allowed for better synchronization. In France, Léon Gaumont developed the Chronophone, a sound-on-disc technology that he patented and exhibited publicly in 1902 (Gaumont Reference Gaumont and Fielding1959, 65). Significant early research into sound synchronization occurred in Germany as well: in 1900, Ernst Ruhmer of Berlin announced his Photographophone, evidently the first device successfully to reproduce sound photographed on film (Crawford Reference Crawford1931, 634), and Oskar Messter’s Biophon apparatus was exhibited at the 1904 World Exposition in St. Louis (Narath Reference Narath and Fielding1960, 115). In the end, these systems had little more than novelty appeal, owing to major difficulties with synchronization and amplification.

A feverish pace of electrical research in the 1920s led to renewed effort in the development of synchronized sound, alongside a number of mass media and sound technologies. Donald Crafton refers to sound film’s various ‘electric affinities’ – including electricity and thermionics, the telephone, radio, television and phonography – that developed prior to or alongside sound-synchronization technology as part of the research boom following the First World War (Reference Crafton1997, 23–61). Perhaps most importantly, the invention of radio tubes led to a much more effective means of amplification. Companies and laboratories experimented with both sound-on-disc and sound-on-film playback technologies. Sound-on-disc sometimes (but not invariably) involved simultaneously recording a phonograph disc and a nitrate image, which were mechanically played back in sync, and sound-on-film consisted of an optical recording of the soundtrack – a physical writing of the sound onto a photographic strip that ran alongside the images. Sound-on-disc initially had somewhat better sound fidelity, and it drew on the long-established recording techniques of phonography, along with its industry and equipment. Sound-on-film, on the other hand, was better for on-location shooting, as the apparatus was more portable and the sound easier to edit. Although sound-on-film ultimately won out, for years both systems remained equally viable.

In 1919, three German inventors – Joseph Engl, Hans Vogt and Joseph Massolle – patented Tri-Ergon, an optical recording system first screened publicly in 1922 (Kreimeier Reference Kreimeier, Kimber and Kimber1996, 178). Meanwhile, in America in 1923, Lee de Forest, working with Theodore Case, patented and demonstrated a system with optical recording technology called Phonofilm. Early Phonofilms included a short speech by President Calvin Coolidge and performances by the vaudeville star Eddie Cantor and African-American songwriting duo Sissle and Blake. Several scores were also recorded and distributed for the Phonofilm system, including Hugo Riesenfeld’s for James Cruze’s The Covered Wagon (1923) and for Lang’s Siegfried (1924). Although de Forest’s system provided some publicity for the technology of synchronized sound film, the system remained mostly a novelty. While the recording process was already quite advanced, as can be heard on extant Phonofilm films, issues remained with Phonofilm’s exhibition and economics. Most importantly, not enough theatres were equipped with the Phonofilm playback equipment. De Forest claimed that as many as fifty theatres had been wired for his system in 1924 (Crafton Reference Crafton1997, 66), but major film companies, which also controlled much of the theatre market, were unwilling to risk production with Phonofilm, and this reluctance made the system commercially unsustainable.

Innovation, Introduction and Dispersion of Synchronized Sound Technology (1926–1932)

Vitaphone

Substantial change arrived with the public success of Vitaphone. Western Electric, a subsidiary of AT&T (American Telephone and Telegraph Company), developed this sound-on-disc system. Western Electric formed a partnership with Warner Bros., a modest but growing studio at the time. According to Crafton, ‘The Vitaphone deal was one of several tactics designed to elevate the small outfit to the status of a film major’ (Reference Crafton1997, 71). Their target market was midsize movie theatres with a capacity of 500–1000 – those theatres too small to afford big names in live entertainment, but large enough to afford the cost of installing sound equipment. (Warner Bros. did not end up following this strategy, since their first sound films were screened at larger, more prominent theatres, and the popularity of the talking picture radically altered the longer-term economic planning.)

Warner Bros. planned to use Vitaphone to replace live orchestral musicians with standardized recordings of musical accompaniment and to offer ‘presentation acts’ in the form of recorded shorts to provide all theatres with access to the biggest stars. In a lecture given at Harvard Business School in early 1927, Harry Warner recounted:

[M]y brother [Sam] … wired me one day: ‘Go to the Western Electric Company and see what I consider the greatest thing in the world’ … Had he wired me to go up and hear a talking picture I would never have gone near it, because I had heard and seen talking pictures so much that I would not have walked across the street to look at one. But when I heard a twelve-piece orchestra on that screen at the Bell Telephone Laboratories, I could not believe my own ears. I walked in back of the screen to see if they did not have an orchestra there synchronizing with the picture. They all laughed at me.

Using Vitaphone to record synchronized musical scores for their feature films, Warner Bros. aimed to codify film-music practices, replacing the diversity of live silent-film accompaniment with more standardized, high-quality musical performances.

For the Vitaphone debut, Warner Bros. recorded a synchronized musical accompaniment and some sound effects for Don Juan (1926), a silent costume drama starring John Barrymore that the company already had in production. The accompaniment was compiled by well-known silent-film composers Axt and Mendoza, both of whom worked at the Capitol Theatre, and was performed by the New York Philharmonic. On 6 August 1926, the film premiered at the Warner Theatre in New York along with a programme of shorts, including the New York Philharmonic playing Wagner’s Tannhäuser Overture (1845) and performances by violinists Mischa Elman and Efrem Zimbalist and by Metropolitan opera singers Marion Talley, Giovanni Martinelli and Anna Case. All shorts that evening were classical performances, with the exception of Roy Smeck, ‘The Wizard of the String’.

As can be seen from this first programme, Warner Bros. emphasized Vitaphone’s connections to high culture at the time of its introduction, explicitly linking sound-film technology and classical music as a means of establishing Vitaphone’s cultural prestige and gaining public acceptance of the somewhat unfamiliar medium. In his recorded public address that opened the programme, Will Hays, president of the Motion Picture Producers & Distributors of America, reinforced this point: ‘The motion picture too is a most potent factor in the development of a national appreciation of good music. That service will now be extended, as the Vitaphone shall carry symphony orchestrations to the town halls of the hamlets’ (quoted in Barrios Reference Barrios1995, 22). Film critic Mordaunt Hall’s review in the New York Times implied that this tactic for gaining public acceptance of the new technology was at least somewhat successful. He stated that the ‘Warner Brothers are to be commended for the high-class entertainment’, and claimed that the programme ‘immediately put the Vitaphone on a dignified but popular plane’ (Hall Reference Hall1926a).

The second Vitaphone premiere, which occurred exactly two months later on 6 October 1926, contrasted with the first in tone and cultural register (Barrios Reference Barrios1995, 26–7). This time the programme of shorts consisted primarily of vaudeville and popular performances (including a performance by Al Jolson in A Plantation Act). As was typical of deluxe theatre practice, the programme was designed to prime the audience for the night’s feature film, a slapstick comedy called The Better ’Ole (1926) starring Syd Chaplin. In his review of The Better ’Ole, Hall was not troubled by the popular tone of the programme, noting that the ‘series of “living sound” subjects are, in this present instance, in a far lighter vein, but none the less remarkable’ (Hall Reference Hall1926b). The third Vitaphone feature, When a Man Loves (1927), which included an original score by famed American composer Henry Hadley (Lewis Reference Lewis2014), did not debut until 3 February 1927, and the programme that premiered with this film split the difference of the first two, mixing shorts of high- and low-brow genres (Barrios Reference Barrios1995, 29–30). A potpourri of genres continued into the 1930s, although the number of classical-music shorts steadily declined. Jennifer Fleeger has argued that the variety of musical shorts in particular – some featuring opera, others jazz – was crucial since ‘opera and jazz provided Hollywood sound cinema with both “high” and “low” parentage, and in the case of Warner Bros., multiple tales of inception that gave the studio room to remake itself’ (Reference Fleeger2009, 20; Reference Fleeger2014a).

Movietone, RKO and RCA Photophone

Following the success of Vitaphone, other companies quickly followed suit. Fox’s Movietone, an optical recording system developed by Theodore Case and Earl Sponable, was the next technology introduced to the American public, in the spring of 1927. As a sound-on-film process, Movietone was capable of portable synchronized recording, and Fox quickly exploited this potential, beginning with the release of sound-enhanced newsreels. In September 1927, Fox began releasing feature films that, like the Vitaphone features, used Movietone to provide synchronized continuous scores and some sound effects. The first three were 7th Heaven, What Price Glory and Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (Melnick Reference Melnick2012, 288–96; Bergstrom Reference Bergstrom2005, 192). All three carried scores compiled by Rothafel, Rapée and the musical staff at the already famed Roxy Theatre. Each of these films also modelled a slightly different conception of how Movietone might be exploited for feature films. 7th Heaven and What Price Glory were both re-releases designed to market and distribute the ‘Roxy touch’. Both films also featured theme songs penned by Rapée and aimed at the sheet-music market. ‘Charmaine’, the theme of What Price Glory based on a song Rapée had written in the teens (Melnick Reference Melnick2012, 263), proved an exceptional hit. The Movietone score for Sunrise (1927), by contrast, was designed for longer-run exploitation (ibid., 295). It was the only film of the original trio that premiered with its Movietone score and a full programme of Movietone shorts, similar to the strategy Warner Bros. had developed for its Vitaphone features. This score, which was received enthusiastically by critics, featured no theme song and was usually attributed to Riesenfeld until Bergstrom (Reference Bergstrom2005) decisively challenged this view, and additional research by Melnick (Reference Melnick2012) conclusively showed that Rothafel, Rapée and the musical staff at the Roxy were responsible for both this score and those for the other early Movietone features.

Photophone, another optical system, this one developed by RCA (a subsidiary of General Electric and owner of NBC, the nation’s largest radio network), was introduced soon after Movietone. The first film with a Photophone soundtrack was Wings, a Paramount production that evidently combined live accompaniment with recorded sound effects featuring propellers and aircraft engines (Marvin Reference Marvin1928). Distributed initially as a road show with up to six soundtracks for effects, Wings was the most popular film of 1927, and it won the Academy Award for Best Engineering Effects (for Roy Pomeroy, who was responsible for the sound).

The Jazz Singer

By the end of 1927, both Warner Bros. and Fox were regularly producing sound films, but the economic certainty of sound film was not yet assured. Insufficient theatres had been wired for sound, and public interest was showing signs of waning in the first half of 1927. In order to drum up enthusiasm, Warner Bros. announced they were producing a film with Al Jolson. This became The Jazz Singer (1927), the first feature with directly recorded synchronized dialogue.

While The Jazz Singer was a turning point for sound film, proving its long-term economic viability and prompting a number of studios to turn their attention to synchronized sound, its importance has been somewhat overstated in popular narratives of the transition to sound. Consensus now seems to be that it was not The Jazz Singer but The Singing Fool (1928) – Jolson’s second feature film and a much greater commercial success – that was decisive in convincing studios to convert to talking pictures. Furthermore, The Jazz Singer was not itself a major aesthetic departure: it merely brought the aesthetics of the Vitaphone shorts into the narrative world of a feature film, presenting what commentators at the time called a ‘vitaphonized’ silent film (Wolfe Reference Wolfe1990, 66‒75; Gomery Reference Gomery1992, 219). Yet the story of The Jazz Singer as the first talking film remains seductive. Its narrative – about a Jewish singer (Jack Robin) and his cantor father who opposes his son’s desire to sing jazz songs – seems to equate the technology of synchronized sound with modernity and youth, and silent film with the older, traditional generation (Rogin Reference Rogin1992). It seems an almost too perfect allegory of the transition to sound.

Beyond that, however, little scholarly attention has been given to the reasons why this film with so little talking in it has come to serve as the point of origin for the talking film. And it seemingly occupied this position already in 1928. Crafton notes that ‘newspaper and magazine reports of the time consistently regarded The Jazz Singer as a breakthrough, turn-around motion picture for Warner Bros. and the genesis of the talkies’, and that the film was ‘an immediate hit’ (Crafton Reference Crafton, Bordwell and Carroll1996, 463, 468). Indeed, in a paper delivered to the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, New York Times reviewer Hall sketched this history of the transition: ‘it is now the familiar Movietone news reel and the financially successful Vitaphone version of Al Jolson’s “Jazz Singer” that caused Hollywood to rush so wildly to sound, when many had given it the cold shoulder when the Warner Brothers launched their first Vitaphone program’ (Reference Hall1928, 608). At that same conference, William A. Johnston stated forthrightly that ‘nothing revolutionary happened until “The Jazz Singer” came along. That is the picture that turned the industry talkie. Al Jolson and a song did the trick’ (Reference Johnston1928, 617).

Ultimately, the commercial success of The Jazz Singer gave Warner Bros. the prerogative to continue experimenting with and releasing sound films. In 1928 they released the first 100 per cent talkie, Lights of New York, and then had a juggernaut hit with The Singing Fool. Other studios followed, rapidly moving towards producing sound films of their own.

Hollywood Adjusts to Sound

The period from 1927 to 1930 was one of much uncertainty and experimentation as the industry adjusted to the technology, economics and emerging aesthetics of sound film. In 1927, AT&T and their subsidiary Western Electric founded ERPI (Electrical Research Products Inc.) to handle rights and standardize costs. ERPI installed sound technology in theatres and studios, and all major companies signed on. Soon after, RCA formed its own studio, RKO Pictures, to exploit its Photophone sound film, and the company also competed with ERPI in wiring theatres. After some initial patent disputes – due to its work in radio, RCA held strong patent positions – the two sides agreed to cross-license the basic technologies, allowing all films to be played on either system. This consolidation further quickened the pace of Hollywood’s transition.

Initially, there were three kinds of sound films: films with synchronized scores and sound effects, part-talkies and 100 per cent talkies. The first category featured music and sound effects that were post-synchronized. Essentially, these films followed silent-film strategies, recording music and sound effects that could have been performed live, using sound as spectacle or special effect. Examples of synchronized sound films include Warner Bros.’ The First Auto (1927) and MGM’s White Shadows in the South Seas (1928). While spoken dialogue was not a part of this kind of film, sometimes the voice was added to the soundtrack off-camera or in post-synchronization, in the manner of a sound effect, such as in The First Auto, parts of The Jazz Singer, White Shadows in the South Seas and Wild Orchids (1929). At the other end of the spectrum was the 100 per cent talkie, emerging out of the aesthetics established in the Vitaphone shorts. The emphasis on spoken dialogue in the early talkies resulted in a general aesthetic shift towards the comprehensibility of dialogue, sometimes at the expense of music or other sound effects. Regular production of 100 per cent talkies did not begin until 1929, perhaps in part because recording equipment and trained personnel to operate it remained in somewhat short supply (K. F. Morgan Reference Morgan1929, 268).

In between was the part-talkie, which was widespread in 1928 and 1929. Part-talkies were a varied lot, and as early as 1929 they were already being discounted as an expedient ‘due to recording and production problems’ (ibid., 271). Many, the so-called goat glands, had begun production as silent films but had dialogue scenes added (Crafton Reference Crafton1997, 168–9, 177). Talking (or singing) scenes in such films could heighten the spectacle and play to the novelty of synchronized sound, much like Technicolor sequences that were also occasionally added to films during this period, although the part-talkie’s shifts from intertitles to spoken dialogue and back with little warning often strike audiences today as jarring. The disparaging contemporaneous term ‘goat gland’ suggests that the lack of integration of the talking sequences also disturbed critics (and perhaps audiences) of the time, though the way the term was deployed indicates that the critics understood ‘talking’ as an interpolation – a gimmick that had been added to a silent film akin to the description of The Jazz Singer as ‘vitaphonized’ – rather than as a conflict between opposing film aesthetics (as such films are usually evaluated today).

Some part-talkies such as The Singing Fool, Noah’s Ark (1928) or Weary River (1929) thoroughly integrated talking and silent sequences, and such films could not be as easily converted into silent films without substantial re-editing (though each did appear in a silent version, and in each case the silent version is, like the goat glands, shorter than the sound version). These part-talkies are films apparently conceived as full hybrids with some thematic thought given to which scenes would better appear silent and which would be suited for spoken dialogue or musical performances. In Lonesome (1928), masterful parallel editing, which follows Jim and Mary in turn, accelerates towards the couple’s eventual union at Coney Island, and this point of conjunction is emphasized by a shift from the silent-film technique of the parallel editing to the talking-film technique of their initial encounter. Although the spectacle of the talking film obviously means to affirm the romance as something transformational for the new couple, the actual technique of talking film here makes the dialogue scene appear (to a modern audience) laboured instead, with much of the vivacious energy, dynamism and music of the silent sequences suddenly drained away during the talking.

As the novelty of spoken dialogue began to wear off, a craze for musical films began. Musicals offered a new kind of film spectacle, featuring elaborate song and dance numbers, frequently advertised as ‘all singing, all dancing and all talking’. Stage talent was brought to the screen in droves, as actors with singing experience, Broadway songwriters and stage directors all found in Hollywood a lucrative source of income and a chance to reach much larger audiences. Many of these early musicals were revues such as The Hollywood Revue of 1929 (1929), The Show of Shows (1929), Paramount on Parade (1930) and King of Jazz (1930), all of which essentially strung together a series of shorts. Such films offered studios opportunities to stage elaborate musical spectacles without having to worry about a connecting narrative and the different approach to capturing dialogue that narrative film required. Like the Vitaphone shorts on which Warner Bros. had honed its techniques, the individual numbers of a revue could be conceived as stage acts, and so dialogue captured with stage diction could simply mark the recording of an act. In this respect, one important innovation of The Broadway Melody (1929), one of MGM’s first talking features and winner of the second Academy Award for Best Picture, was the way it distinguished stage and backstage in terms of sound design realized as the approach to recording. It proved an important model for the backstage musical, although Warners’ musical part-talkies starring Jolson (The Jazz Singer and The Singing Fool) also largely follow this model. In the backstage musical, the dramatic action happened behind the scenes, and the musical numbers, often in colour and thematically unrelated to the principal action, would thus be given diegetic justification as performance. Operettas such as The Desert Song (1929), The Love Parade (1929) and The Lottery Bride (1930) were another important type of musical film during the transition era. Additionally, film musicals often exploited the synergy between the film and popular-music industries. As Katherine Spring has shown (Reference Spring2013), popular songs were ubiquitous during the transition period, even in non-musical films; and sometimes, as in Weary River, it is hard to tell the difference between a dramatic film and a musical.

Shifts in recording practices and sound editing affected the emerging aesthetics of sound film. Originally all sounds were recorded live on set; many accounts (and production photographs) reference musicians situated just off-screen. This posed many challenges regarding microphone placement and mixing. It also usually resulted in longer takes, since there was less fluidity with editing than had been possible in silent film. Various improvements ultimately led to sound editing and mixing taking place in post-production. Filming to playback – the recording of a song in the studio in advance, to be played back and lip-synced by the actors while the image was shot silent – was the method used by Gaumont to produce Chronophone films, and it was purportedly used in The Jazz Singer to cover Jolson’s canting (Crafton Reference Crafton1997, 240), but it was sometimes difficult to achieve a convincing illusion of precise synchronization, and the technique also posed logistical problems for complicated scenes such as production numbers. The first commonly cited example of pre-recording was Broadway Melody, and after 1929 the practice became common (Barrios Reference Barrios1995, 60; Crafton Reference Crafton1997, 236).

Dubbing and re-recording had been possible if not always completely feasible since 1927, but there was a loss of recording fidelity, especially with sound-on-film (Jacobs Reference Jacobs2012). Warners, the only studio using sound-on-disc, had a working re-recording process by 1928 that allowed music underscoring (Slowik Reference Slowik2014, 64–73). As J. P. Maxfield explained,

The whole process [of Vitaphone rerecording] has been improved by the use of semi-permanent records of special material with a needle carefully fitted to the groove. This improvement has gone so far that no measureable surface noise is added in the process of dubbing.

Maxfield’s description makes clear, however, that Vitaphone dubbing was a convoluted process that had to be done in real time. As such, the practice did not become widespread until the early 1930s, when techniques for reducing the ground noise of film had developed sufficiently to allow reliable re-recording with sound-on-film. Early on, voice dubbing would often be done directly on the set, rather than through pre-recording or re-recording (Larkin Reference Larkin1929). In The Jazz Singer, for instance, the father’s one word of dialogue and Jolson’s piano playing were evidently both dubbed in live off-camera (‘Open Forum’ 1928, 1134).

Of course, film-music composition also underwent substantial change. Initially, the organization of music departments in Hollywood was somewhat ad hoc. In the late 1920s, the Hollywood studios either called upon composers with experience in silent-film scoring from deluxe theatres or they recruited composers, orchestrators and arrangers with experience on Broadway, including songwriters for film musicals. The composers from the deluxe cinemas, such as Riesenfeld and Mendoza, were assigned to score the synchronized silent films, whereas those who had specialized in arranging and composing Broadway production music, such as Max Steiner, Louis Silvers, Herbert Stothart and Alfred Newman, were assigned to the musicals and talking pictures. These initial assignments would have important consequences as studios quickly eliminated silent-film production, leaving a set of composers trained more on Broadway than in the silent cinema to establish the musical conventions of the Hollywood sound film. As talking pictures rapidly took over, musical accompaniment shifted from the wall-to-wall scoring characteristic of silent cinema to becoming increasingly intermittent. Nevertheless, this shift seems not to have been wholly a product of inadequate technologies of re-recording, as scholars have long presumed, since many talking films from before 1930, including the first all-talking Lights of New York, have extensive music underscoring dialogue (Slowik Reference Slowik2014, 89–93; Buhler and Neumeyer Reference Buhler, Neumeyer and Neumeyer2014, 25–6). Instead, the shift seems better explained by the kinds of films being made between 1930 and 1932 – more contemporary drama – and filmmakers’ uncertainty over how closely the musical practice of the sound film should follow that of the silent film. In essence, wall-to-wall music threatened to make sound film appear a little too much like silent film.

Although the technology improved quickly during the transitional period, its advance was also highly disruptive to established working conditions, and those most threatened with displacement by the new technology hardly welcomed its arrival. Labour disputes, especially with musicians, were widespread. Many theatre musicians were laid off as orchestras and organists were replaced with synchronized soundtracks. The musicians’ union fought for the continuation of live music, but without much success (Kraft Reference Kraft1996, 47–58; Cooke Reference Cooke2008, 46–7). At the same time, the new technology prompted a need for studio musicians; and, as a result, many of the best musicians moved to Hollywood.

Additionally, standardization came somewhat more slowly than was optimal because many theatres had initially invested in sound-on-disc and did not want to pay to convert to sound-on-film. Furthermore, although sound-on-film did not suffer from potential synchronization issues as did sound-on-disc, the former initially had more problems with sound quality in exhibition. At first, many major studios released films on both formats, a procedure that continued through the mid-1930s. Nevertheless, the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and subsequent deep and prolonged economic downturn profoundly affected the industry (as it affected nearly all aspects of American life), forcing studios to streamline their productions, to limit experiments and to focus on codification of best practices. By the start of 1931, Warner Bros. had joined the other Hollywood studios and begun converting to production using sound-on-film, and the production of silent films in Hollywood was also mostly over, with the exception of a few holdouts like Charlie Chaplin.

As sound-film technology became increasingly standardized, so did production practices. David Bordwell has emphasized the way the film industry worked to re-establish many of the regular production techniques from the silent film that had been disrupted with the coming of sound. These included, in particular, scene construction based on editing and single-camera shooting. The early sound film had used the soundtrack as the master shot to establish continuity in a scene. The image could be edited to the master continuity of the soundtrack, either by filming the scene with multiple cameras from various positions and with lenses of different focal lengths or through the use of cut-ins, especially reaction shots of characters listening. Through improved blimping, microphones, film stock, techniques of re-recording and other technology, the need for the audio master shot became less pressing (Bordwell et al. Reference Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson1985, 301–6).

Innovation and Resistance in Europe (1929‒1931)

While the transition to sound in the United States was rapid, the dissemination of the technology around the world was wildly uneven due to the large capital investments required and the financial uncertainty caused by the Great Depression. Because most theatres in Europe were wired for sound after 1929, the Depression created an economically chaotic situation as exhibition practices lagged behind production practices, and many sound films were initially shown silent at many theatres (Kreimeier Reference Kreimeier, Kimber and Kimber1996, 182). Furthermore, the change was, in many ways, controlled and dictated by American production and distribution companies. The United States had dominated world markets since the First World War, and American companies’ patents on sound synchronization technologies gave them a distinct advantage over the film industries of other countries, except perhaps in Germany, where the film industry took advantage of its control over key sound-film patents (Gomery Reference Gomery1976; Gomery Reference Gomery2005, 109–13). The reaction to synchronized sound in Europe provides a particularly rich story of competition, resistance and innovation in the aftermath of widespread technological change (Gomery Reference Gomery2005, 105–14).

Even as Hollywood adjusted to the changes brought on by synchronized sound, American companies sought to expand their reach (and their profits) through international distribution of sound films. They saw Europe in particular as an available market. The installation of sound equipment and distribution of sound films in countries that had not yet developed the technology to do this themselves promised to be lucrative. Engineers in Europe, however, had also made progress on sound-synchronization technology: more than fifteen sound systems were competing in Europe during the transitional period and, by 1928, the primarily Dutch-owned Tobis was formed, controlling most of the important patents in Europe, including the Tri-Ergon system (Kreimeier Reference Kreimeier, Kimber and Kimber1996, 178–9). Ufa, AEG and Siemens and Halske then launched the company Klangfilm to organize the German industry’s response. In 1929, Tobis and Klangfilm came to an agreement, and they began jointly marketing their technology as Tobis-Klangfilm, aiming to corner the European market and shut out American companies. Tobis-Klangfilm sought to stall the American film industry’s impending control of the international market, disputing patents in the hope of obstructing what they saw as an inevitable ‘talkie invasion’ by the American companies (Gomery Reference Gomery1980, 85) – not just studios, but also the activity of firms like ERPI that posed a major threat to more basic industrial concerns. In the summer of 1930, representatives from Tobis-Klangfilm and members of the American film industry conferred on neutral ground in Paris. An international cartel resulted from this ‘Paris Agreement’, and the German and American companies agreed to split up much of the world for patent rights and charge films royalties for distribution within each territory. As German and American companies held the decisive patents, other national film industries were at the mercy of foreign firms for the technology to produce and exhibit sound films. Resistance to the change was particularly widespread in countries like France due to fear that national cinematic practices would diminish.

Because the European transition to commercial sound-film production came somewhat later than in the United States (initially running two to three years behind), and perhaps because they had the American model to react to or because they needed to play catch-up, Europeans developed a number of innovative sound films as they made the transition. In England, Blackmail (1929) was originally planned as a silent film, but the quick inroads sound film was making in British theatres required that director Alfred Hitchcock re-conceive the film with dialogue sequences. As was commonly the case during the transition era, a silent version was also released for theatres not yet equipped with sound. The lead actress (Anny Ondra) had a heavy Czech accent, so Joan Barry was hired to speak the dialogue off-camera, essentially dubbing the film live because techniques of post-synchronization were not yet well developed (Belton Reference Belton1999).

Walter Ruttmann devised an innovative audiovisual aesthetic in his first sound film, Melodie der Welt. Adapting the approach he took in his silent Berlin: Die Sinfonie der Großstadt (Berlin: Symphony of a Great City; 1927), Ruttmann created an audiovisual ‘symphony’, a collage of recorded diegetic sounds corresponding to the montage of images from around the world. The soundtrack sounds almost like a prototype for musique concrète. Ruttmann also experimented with sound-only films. In 1931, Lang directed his first sound film, M, a wonderfully strange hybrid that combines silent-film technique (including fully silent sequences), a kind of voice-over narration to connect different locations, and off-screen sound to heighten suspense. Though Lang’s approach to sound in M might, like Hitchcock’s work on Blackmail, seem related to the technical challenges of synchronized sound film, it should be noted that by 1931 films coming out of the German film industry had achieved a high technical standard with respect to dialogue. Although shooting more dialogue without showing moving lips than American films from the time, deft handling of synchronized dialogue is nevertheless demonstrated in Die Drei von der Tankstelle (Three Good Friends or Three Men and Lilian; 1930), Erik Charell’s Der Kongreß tanzt (The Congress Dances; 1931) and Pabst’s Westfront 1918: Vier von der Infanterie (Comrades of 1918; 1930), Die 3 Groschen-Oper (The Threepenny Opera; 1931) and Kameradschaft (‘Comradeship’; 1931). If M was not an improvised solution to challenges posed by inadequate technology, it seems instead an experiment to avoid the obviousness of sync sound without reverting wholly to silent-film technique.

While establishing close and convincing synchronization remained a continual concern, and American films generally began a shot with a sync point of flapping lips and dialogue before passing to reaction shots, European films were on the whole less obsessed with such close dialogue synchronization and frequently shot dialogue from behind, where synchronization could be much looser. In early cases, like Blackmail and Augusto Genina’s Prix de beauté (Miss Europe or Beauty Prize; 1930), this seems to have been an expedient to allow dialogue to be added during post-production to footage shot silent. But the practice continued in later films, most notably in René Clair’s three Parisian operettas. In general, Clair explored an approach to sound film that also downplayed dialogue in favour of other sound elements. Apparent especially in his 1931 film Le Million, his first sound films use minimal dialogue, instead utilizing audiovisual counterpoint and songs to propel the action forwards. Clair does not completely avoid dialogue, but he associates it with the negative forces of economic necessity and the law. He also frequently shoots dialogue with the principal characters facing away from the camera. This strategy of loose synchronization endows the voice with a certain lightness – as though it is only barely contained by the speaking body and might break free at any moment (Fischer Reference Fischer1977; Gorbman Reference Gorbman1987, 140–50; Cooke Reference Cooke2008, 62–4). Clair’s world, inspired by vaudeville stage comedies, is comic and giddy, ruled by happenstance.

The experimental tradition of filmmaking in the Soviet Union continued for a time with sound. Dziga Vertov was the first Soviet director to make a sound film in the USSR: Enthusiasm, released in 1931. In the film, on-location sound and mechanical sound effects are woven together to create a collage, as was the case with Ruttmann. Vertov’s experimental approach to the soundtrack combined with the subject of Soviet miners, thereby reflecting the broader values of Soviet filmmakers that had begun with silent films like his earlier Man With a Movie Camera (1929) and Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin.

Vococentrism and the Codification of Practices (1931–1935)

After 1930, due in part to adverse economic pressures from the Great Depression, codification of effective practices for producing sound film became an ever more important goal of the industry, especially in the United States. This had the effect of curtailing the spirit of experimentation, and the wide-ranging practices of the early years gave way to an increasingly ordered set of practices defined by the principles of ‘vococentrism’ (Chion Reference Chion and Gorbman1999, 5; Neumeyer Reference Neumeyer and Buhler2015, 3–49). Despite calls for continued development of the possibilities of asynchronous sound by theorists, experiments in sound design that pushed against the default vococentrism of synchronized dialogue such as films by Chaplin, Clair, Lang, Pudovkin and Eisenstein frequently yielded excellent and provocative films but little real influence on the direction of mainstream filmmaking. Whether in the United States or internationally, in the years after 1930 commercial sound film increasingly simply meant talking film, and the vococentrism of talking film meant a high preponderance of synchronized dialogue.

In practice, however, vococentrism dominated because it was a robust yet flexible principle. If vococentrism insisted on the centrality of dialogue on the soundtrack, this did not mean that dialogue was uniformly ubiquitous or that sync dialogue featured prominently at every moment in the talking film. Certainly, some films were edited primarily on the basis of dialogue, so that each new line motivated a cut and almost all of the soundtrack was taken up by dialogue. But the power of the reaction shot was understood almost immediately, as was the potential for sound effects, and to some extent music, to complement and contextualize the voice, to make a setting for it. As Clair noted in his appreciative remarks about The Broadway Melody, ‘We hear the noise of a door being slammed and a car driving off while we are shown Bessie Love’s anguished face watching from a window the departure we do not see’ (Clair Reference Clair and Traill1953, 94). Since Michel Chion draws vococentrism from an analogy with the face, it is worth lingering on this comparison. If the face dominated the cinematography and editing of narrative film, this did not mean that every shot was a close-up, or that every shot revealed a face (except perhaps in a metaphorical way: the face of things, the face of the world), or even that every shot containing a face centred it. The centricity of the face in classic style was instead interpretive: it presumed that the reading of the image would be guided by the placement and displacement of the face within and from the frame. A similar situation pertained to the voice and the soundtrack. Vococentrism meant understanding the soundtrack in terms of the setting of the voice, and the expressive potential of the reaction shot lay at least in part in the way that it shifted the audiovisual interpretive significance of the voice from cause (the source of the dialogue in the speaking body) to its effect (on a particular listener).

Even as the industry rapidly standardized practices that favoured vococentrism, sound film continued to be widely distrusted by many who worked in the industry, both in Europe and America. If American companies moved quickly to convert to sound, the rapidity of the transition by no means indicated any kind of consensus surrounding its desirability over silent film. Many still understood sound film, especially dialogue, as contrary to the spirit of cinema. Europeans, notably Soviet and French directors, were particularly resistant. In the USSR, Eisenstein, Pudovkin and Alexandrov, three prominent directors, wrote an influential statement in 1928 attacking Hollywood’s approach to sound film before they had even seen one of its films. Rather than having image and sound slavishly bound in synchronized dialogue, the Soviet directors advocated a counterpoint between image and sound, a relationship that they believed was the audiovisual equivalent of the dialectical montage for which Soviet films had become justly famous (K. Thompson Reference Thompson1980; Eisenstein, Pudovkin and Alexandrov Reference Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Alexandrov, Leyda, Weis and Belton1928). Initially, Clair – well known for the visual style of his silent films – was also strongly opposed to the talking film, fearing synchronized dialogue in particular would destroy the expressive power of the image. He likewise advocated setting sound contrapuntally against the image in order to resist a naturalistically constructed synchronization grounded in realism, writing that ‘if imitation of real noises seems limited and disappointing, it is possible that an interpretation of noises may have more of a future in it … We do not need to hear the sound of clapping if we can see the clapping hands’ (Clair Reference Clair and Traill1953, 91–4, emphases in original).

The opposition between talking film as slavish synchronization and sound film as a site for inspired counterpoint, or asynchronous sound, as its best antidote was picked up by most film theorists of the time, including Béla Balázs and Rudolf Arnheim. According to Balázs, sound film should ‘approach the reality of life from a totally different angle and open up a new treasure-house of human experience’ (Reference Balázs and Bone1970 [1952], 197). Arnheim, by contrast, questioned the efficacy of asynchronous sound in many instances and focused as much on the power of synchronization as its redundancy: synchronized sound transformed film, the act of synchronization opening a divide between foreground elements in the image and the background. Sound film, he noted, ‘endows the actor with speech, and since only he can have it, all other things are pushed into the background’ (Reference Arnheim1957, 227).

As Arnheim was quite aware – and none too pleased – the synchronization of the sound film had the effect of imposing an ordering hierarchy on the image: synchronized objects were important objects, and dialogue added another level that made vococentrism the technical principle that implemented sound film’s irreducible anthropocentrism. In the silent film, by contrast, the world was not divided by a capacity to articulate meaning through talk; an essential continuity between people and things was assured in their common muteness, the universal condition of the silent image. With such a hierarchy of sounds established, the focus on the voice ensured the centrality of the human figure and its subjectivity in the sound film’s new economy of meaning and intention. Music and sound effects, then, set the voice within the economy of human meaning.

Vococentrism can therefore be understood as an effective reworking of the three principles of silent-film music, recast as powers within the hierarchal order of foreground and background. Centricity rewrites the principle of synchronization as a marker of import, the site of meaning that assures the appearance of subjectivity and its hegemonic status. Continuity becomes the power of background, the guarantor that the image presents only a view, a fragment of a world that extends indefinitely beyond the frame. Continuity also establishes the more or less neutral ground of asynchronous sound against which the synchronization of the foreground figure stands out in contrast. Finally, vococentrism redeploys subjugation to unlock its full syntactical power, that of the hierarchy itself; but subjugation pertains not simply to music and effects vis-à-vis the voice or the soundtrack vis-à-vis the image, but ultimately to the subjugation of everything to narrative, the cinematic form of meaningful action. Vococentrism, then, is the principle of the voice of narrative, which organized the codification of classical style.

Conclusion: The Emergence of the New Art

The traditional historical narrative of film music places the end of the transition to sound in 1933 with Steiner’s score for King Kong, which is typically considered to be the first classical Hollywood film score and responsible for beginning an era of relatively standardized approach to composing for films. This narrative is, of course, an oversimplification. Slowik argues that Steiner’s practice in the early 1930s was less an innovation than an extension and codification of methods that had developed in the silent film and had continued as a minority practice through the transitional period. Writing on Steiner’s scores for Symphony of Six Million and The Most Dangerous Game (both 1932), Slowik states ‘Steiner’s primary contribution was to reintroduce the theme-driven score in a dramatic context, an approach that had fallen out of favor with the advent of the 100 percent talkie’ (Reference Slowik2014, 204). Nathan Platte’s work on Steiner’s early scores during this period likewise makes it clear that many innovations that have been assigned to Kong in standard film-music histories had predecessors in earlier scores by Steiner and others (Platte Reference Platte2014). Nevertheless, the music for Kong seems much more consistent with the practices that would dominate Hollywood film music during the classic era than do the sound-film scores that came before it – with the possible exception of Symphony of Six Million (ibid., 321, 328; Long Reference Long2008, 88) – and indeed many that come after it. Steiner’s innovations would seem to belong to the manner in which he evoked but also broke with silent-film practice in a way that enabled him to forge an underscore predicated on sound film. But this practice did not emerge immediately in Steiner’s music, and, as Slowik and Platte both note, Kong still retained strong affinities to transitional accompaniment practices quite continuous with those of the silent film.

Like The Jazz Singer, Kong was perhaps primed to become a signal event, and to serve as the moment of origin for the classic Hollywood film score, because its soundtrack thematized its problem and so could be allegorized into a general solution. Slowik notes structural affinities between Kong and the earlier Symphony of Six Million with respect to music: both films initially develop an opposition of space articulated with music (island, ghetto) and without music (city, uptown). Six Million begins in the ghetto and returns to it, and throughout music remains bound to the ghetto, which is rendered exotic and pathetic in virtue of its musicality. Kong inverts this arrangement, beginning with the city devoid of music, devoid of life; the exotic island is then suffused with music, and Kong’s forced appearance in the city has the effect of releasing music into it (Buhler et al. Reference Buhler, Neumeyer and Deemer2010, 331). According to Slowik, ‘What marked King Kong as unusual was not a musical decision to tie music to fantasy but rather a narrative decision to depict urban reality and exotic fantasy in the same film and to blend them together in the final act’ (Reference Slowik2014, 234). And Slowik rightly notes that Steiner’s score for the film is fully consistent with film-music practice that had developed at the end of the transitional period. Yet this revisionist claim, although broadly correct, is akin to the one that would minimize the influence of The Jazz Singer in the transition to sound; neither claim accounts for the fact that these stories began circulating almost immediately. They may well form crucial pieces in the mythology of sound film, but the myth was already forming at the moment of origin. If Steiner could quickly represent Kong as having opened a new path for music in film (Reference Steiner and Naumburg1937, 220), it is likely that he seized on this film and not his previous or later work for a reason, even if he had a strong self-interest in promoting his own work.

While films like The Jazz Singer and Kong have become iconic in the history of film sound and film music for their innovations framing the transition period, the myths surrounding these films obscure a much richer history: one of codification and experimentation, of unexpected continuity and major disruption and of negotiation and confrontation. The shift occurred in markedly different ways in Hollywood and in Europe, and the technology’s dissemination to the rest of the world reveals further dimensions and complexities to the story of the transition. Emily Thompson, for instance, in her study of the installation of sound technology around the world, writes that sound film ‘provided a powerful new means by which to articulate national agenda, and the end result was not a single, standardized and unified modern voice but a cacophony of competing signals and messages’ (Reference Thompson and Erlmann2004, 192). Within this period, the role of music and sound in cinema shifted in many dramatic ways, but emerging out of the transition period the major principles motivating their use remained. The maintaining of these principles was by no means inevitable, as producers, directors and composers around the world negotiated the role of music and sound in the soundtrack; moreover, experiments with the soundtrack did not cease after the transition period. Many of the most innovative uses of sound in later films came from directors and composers who bucked the trends of established practices. Yet the manner in which film music and sound practices were standardized by the mid-1930s reveals certain constants from the silent to the ‘classical’ era of filmmaking: sound film, organized under the principle of vococentrism, ultimately had the effect of tightening the already powerful grip of narrative on cinema.

Synchronization sometimes went disastrously wrong in early experiments to join sound and film, particularly if these two components were reproduced separately and got out of step, say due to the film having been damaged, a section removed and the ends joined together. Austin Lescarboura, managing editor of Scientific American from 1919 to 1924, devoted a chapter of his book Behind the Motion-Picture Screen (first published in 1919) to the topic of ‘Pictures That Talk and Sing’ and described a scene from the film Julius Caesar (1913) – an early Shakespeare adaptation presented in the Kinetophone sound system with sound provided by synchronized Edison sound cylinders – in which an actor ‘suddenly sheathed his sword, and a few seconds later came the commanding voice from the phonograph, somewhere behind the screen saying: “Sheathe thy sword, Brutus!”’ (Lescarboura Reference Lescarboura1921, 292). The audience’s response was, understandably, one of hilarity.

Lescarboura, with considerable prescience, foresaw that the principles involved in new photographic methods of recording sound – then still at an experimental stage – would ‘some day form the basis of a commercial system’ (ibid., 300). Early attempts at ‘sound on picture’ (such as Lee de Forest’s Phonofilm) suffered from problems of noise, but by 1928 many of these had been resolved and a soundtrack that had reasonable fidelity became available through Movietone, which, like Phonofilm, had the advantage of the soundtrack actually lying on the print beside the pictures, thus removing the problem of ‘drift’ between two separate, albeit connected, mechanisms. The fascinating period during which filmmakers came to terms, in various ways, with the implications of the new technology is charted in detail in Chapter 1 of the present volume.

According to John Michael Weaver, James G. Stewart (a soundman hired by RKO in 1931 and chief re-recording mixer for the company from 1933 to 1945) recalled that the first sound engineers in film wielded considerable power:

during the early days of Hollywood’s conversion to sound, the production mixer’s power on the set sometimes rivalled the director’s. Recordists were able to insist that cameras be isolated in soundproof booths, and they even had the authority to cut a scene-in-progress when they didn’t like what they were hearing.

Stewart noted that the impositions made by the sound crew in pursuit of audio quality in the first year of talkies had a detrimental effect on the movies, bringing about ‘a static quality that’s terrible’. Indeed, one might argue that film sound technology, from its very inception, has been driven forward by the attempt to accommodate the competing demands of sonic fidelity and naturalness.

Peter Copeland has remarked how rapidly many of the most important characteristics of sound editing were developed and adopted. By 1931, the following impressive list of techniques was available:

cut-and-splice sound editing; dubbing mute shots (i.e. providing library sounds for completely silent bits of film); quiet cameras; ‘talkback’ and other intercom systems; ‘boom’ microphones (so the mike could be placed over the actor’s head and moved as necessary); equalization; track-bouncing; replacement of dialogue (including alternative languages); filtering (for removing traffic noise, wind noise, or simulating telephone conversations); busbars for routing controlled amounts of foldback or reverberation; three-track recording (music, effects, and dialogue, any of which could be changed as necessary); automatic volume limiters; and synchronous playback (for dance or mimed shots).

Re-recording, which was used less frequently before 1931, would become increasingly prevalent through the 1930s due to the development of noise-reduction techniques, significantly impacting on scoring and music-editing activities (Jacobs Reference Jacobs2012).

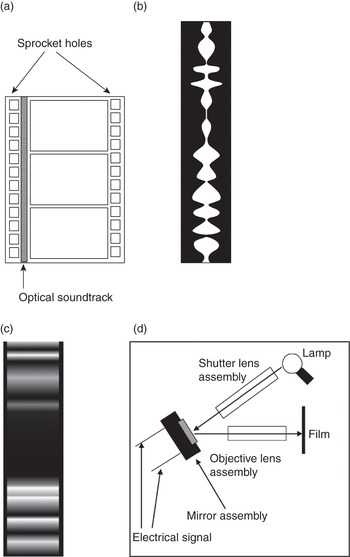

The Principles of Optical Recording and Projection

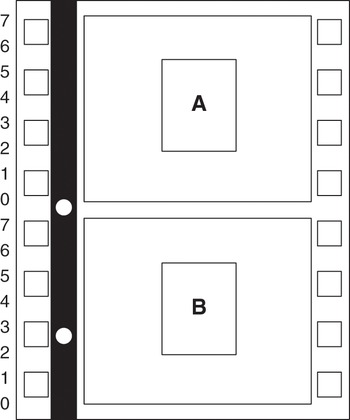

A fundamental principle of sound recording is that of transduction, the conversion of energy from one form to another. Using a microphone, sound can be transformed from changes in air pressure to equivalent electrical variations that may then be recorded onto magnetic tape. Optical recording provides a further means of storing audio, either through the changes in density, or more commonly the changes in width of the developed section of a strip of photographic emulsion lying between the sprocket holes and the picture frames. Figure 2.1(a) displays one of a number of different formats for the variable-width track with a solid black edge on the left-hand side, which is termed the unilateral variable area, shown in Figure 2.1(b). Other alternatives (bilateral, duplex and push-pull variable areas) have solid edges on the right side or on both sides. In variable-density recording, the photographic emulsion can take on any state between undeveloped (black – no light passes through) to fully developed (clear – all light passes through). Between these two states, different ‘grey tones’ transmit more or less light: see Figure 2.1(c). In digital optical recording tiny dots are recorded, like the pits on a CD.

Figure 2.1 35 mm film with optical soundtrack (a), a close-up of a portion of the variable-area soundtrack (b), a close-up of a portion of the variable-density soundtrack (c) and a simplified schematic view of a variable-area recorder from the late 1930s (d), based on Figure 11 from L. E. Clark and John K. Hilliard, ‘Types of Film Recording’ (Reference Clark and Hilliard1938, 28). Note that there are four sprocket holes on each frame.

The technology for variable-area recording, as refined in the 1930s, involves a complex assembly in which the motion of a mirror reflecting light onto the optical track by way of a series of lenses is controlled by the electrical signal generated by the microphone: see Figure 2.1(d). If no signal is present, the opaque and clear sections of film will have equal areas, and as the sound level changes, so does the clear area. When the film is subsequently projected, light is shone through the optical track and is received by a photoelectric cell, a device which converts the illumination it receives back to an electrical signal which varies in proportion to the light impinging on it, and this signal is amplified and passed to the auditorium loudspeakers. The clear area of the soundtrack, between the two opaque sections shown in Figure 2.1(b), is prone to contamination by particles of dirt, grains of silver, abrasions and so on. These contaminants, which are randomly distributed on the film, result in noise which effectively reduces the available dynamic range: the quieter the recording (and thus the larger the clear area on the film soundtrack), the more foreign particles will be present and the greater will be the relative level of noise compared to recorded sound. Much effort was expended by the studios to counteract this deficiency in optical recording by means of noise reduction in the 1930s, the so-called push-pull system for variable-area recording being developed by RCA and that for variable-width recording by Western Electric’s ERPI (see Frayne Reference Frayne1976 and Jacobs Reference Jacobs2012, 14–18).

Cinematography involves a kind of sampling, each ‘sample’ being a single picture or frame of film – three such frames are shown in Figure 2.1(a) – with twenty-four images typically being taken or projected every second. Time-lapse and high-speed photography will also use different frame rates. Early film often had much lower frame rates, for instance 16 frames per second (fps). The illusion of continuity generated when the frames are replayed at an appropriate rate is usually ascribed to persistence of vision (the tendency for an image to remain on the retina for a short time after its stimulus has disappeared), though this is disputed by some psychologists as an explanation of the phenomenon of apparent or stroboscopic movement found in film: as Julian Hochberg notes, ‘persistence would result in the superposition of the successive views’ (Reference Hochberg and Gregory1987, 604). A major technical issue which the first film engineers had to confront was how to create a mechanism which could produce the stop-go motion needed to shoot or project film, for the negative or print must be held still for the brief time needed to expose or display it, and then moved to the next frame in about 1/80th of a second. Attempts to solve this intermittent-motion problem resulted in such curious devices as the ‘drunken screw’ and the ‘beater movement’, but generally a ratchet and claw mechanism is found in the film camera.

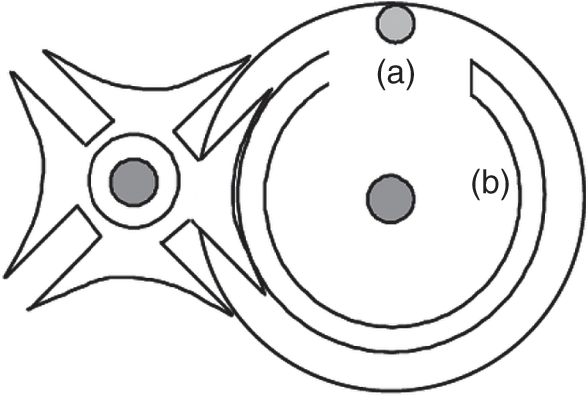

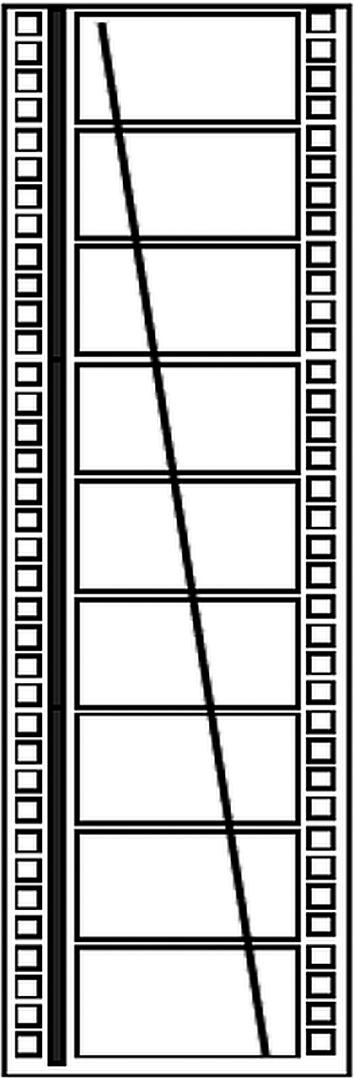

Some film projectors still use one of the most ingenious of the early inventions, modelled on the ‘Geneva’ movement of some Swiss watches and called the ‘Maltese Cross movement’ because of the shape of its star wheel: see Figure 2.2. The wheel on the right has a pin (a) and a raised cam with a cut-out (b). As this cam-wheel rotates on its central pivot, the star wheel on the left (which controls the motion of the film) remains stationary until its wings reach the cut-out and the gap between the wings locks onto the pin. The star wheel is now forced to turn by a quarter of a rotation, advancing the film by one frame. Unlike the intermittent motion required for filming and projection, sound recording and replay needs constant, regular movement. A pair of damping rollers (rather like a miniature old-fashioned washing mangle) therefore smoothes the film’s progress before it reaches the exciter lamp and the photoelectric cell, which generate the electrical signal from the optical track and hence to the audio amplifier and the auditorium loudspeakers. As the soundtrack reaches the sound head some twenty frames after the picture reaches the projector, sound must be offset ahead of its associated picture by twenty frames to compensate.

Figure 2.2 The Maltese Cross or Geneva mechanism.

Soundtracks on Release Prints

Early sound films only provided a monophonic soundtrack for reproduction, and this necessarily limited the extent to which a ‘three-dimensional’ sound-space could be simulated. This was an issue of considerable importance to sound engineers. Kenneth Lambert, in his chapter ‘Re-recording and Preparation for Release’ in the 1938 professional instructional manual Motion Picture Sound Engineering, remarks:

Most of us hear with two ears. Present recording systems hear as if only with one, and adjustments of quality must be made electrically or acoustically to simulate the effect of two ears. Cover one ear and note how voices become more masked by surrounding noises. This effect is overcome in recording, partially by the use of a somewhat directional microphone which discriminates against sound coming from the back and the sides of the microphone, and partially by placing the microphone a little closer to the actor than we normally should have our ears.

Whilst it was possible to suggest the position of a sound-source in terms of its apparent distance from the viewer by adjustment of the relative levels of the various sonic components, microphone position and equalization, filmmakers could not provide explicit lateral directional information. If, for instance, a car was seen to drive across the visual foreground from left to right, the level of the sound effect of the car’s engine might be increased as it approached the centre of the frame and decreased as it moved to the right, but this hardly provided a fully convincing accompaniment to the motion. In order to create directional cues for sound effects, further soundtracks were required. Lest there be any confusion, the term ‘stereo’ has not usually implied two-channel stereophony in film sound reproduction, as it does in the world of audio hi-fi (the Greek root stereos (στερεός) actually means ‘solid’ or ‘firm’); rather, it normally indicates a minimum of three channels. As early as the mid-1930s, Bell Laboratories were working on stereophonic reproduction (though, interestingly, no mention is made of these developments in Motion Picture Sound Engineering in 1938), and between 1939 and 1940 Warner Bros. released Four Wives and Santa Fe Trail, both of which used the three-channel Vitasound system, had scores by Max Steiner and were directed by Michael Curtiz (Bordwell et al. Reference Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson1985, 359).

Disney’s animation Fantasia (1940), one of the most technically innovative films of its time, made use of a high-quality multi-channel system called Fantasound. This system represented Disney’s response to a number of perceived shortcomings of contemporaneous film sound, as was explained in a 1941 trade journal:

(a) Limited Volume Range. – The limited volume range of conventional recordings is reasonably satisfactory for the reproduction of ordinary dialog and incidental music, under average theater conditions. However, symphonic music and dramatic effects are noticeably impaired by excessive ground-noise and amplitude distortion.

(b) Point-Source of Sound. – A point-source of sound has certain advantages for monaural dialog reproduction with action confined to the center of the screen, but music and effects suffer from a form of acoustic phase distortion that is absent when the sound comes from a broad source.

(c) Fixed Localization of the Sound-Source at Screen Center. – The limitations of single-channel dialog have forced the development of a camera and cutting technic built around action at the center of the screen, or more strictly, the center of the conventional high-frequency horn. A three-channel system, allowing localization away from screen center, removes this single-channel limitation, and this increases the flexibility of the sound medium.

(d) Fixed Source of Sound. – In live entertainment practically all sound-sources are fixed in space. Any movements that do occur, occur slowly. It has been found that by artificially causing the source of sound to move rapidly in space the result can be highly dramatic and desirable.

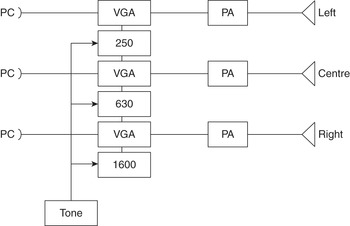

In its final incarnation, the Fantasound system had two separate 35 mm prints, one of which carried four optical soundtracks (left, right, centre and a control track). Nine optical tracks were utilized for the original multitrack orchestral recordings (six for different sections of the orchestra, one for ambience, one containing a monophonic mix and one which was to be used as a guide track by the animators). These were mixed down to three surround soundtracks, the playback system requiring two projectors, one for the picture (which had a normal mono optical soundtrack as a backup) and a second to play the three optical stereo tracks. The fourth track provided what would now be regarded as a type of automated fader control. Tones of three different frequencies (250 Hz, 630 Hz and 1600 Hz) were recorded, their levels varying in proportion to the required levels of each of the three soundtracks (which were originally recorded at close to maximum level), and these signals were subsequently band-pass filtered to recover the original tones and passed to variable-gain amplifiers which controlled the output level: see Figure 2.3 for a simplified diagram. The cinema set-up involved three horns at the front (left, centre and right) and two at the rear, the latter being automated to either supplement or replace the signals being fed to the front left and right speakers.

Figure 2.3 A simplified block diagram of the Fantasound system (after Figure 2 in Garity and Hawkins Reference Garity and Hawkins1941). PC indicates photocell, PA power amplifier and VGA variable-gain amplifier.