Introduction

Some young people in today’s Western democracies are politically active. Among them, a few adopt political means that go beyond what is legal in order to try to exert influence on decision making (Oswald and Schmid, Reference Oswald and Schmid1998; Cameron and Nickerson, Reference Cameron and Nickerson2009; Gavray et al., Reference Gavray, Fournier and Born2012). Preferences for, and involvement in, illegal political activities seem to peak in mid-adolescence (at ages 15–16), with a continuous decline thereafter (Watts, Reference Watts1999). Usually, the adolescents who adopt illegal political means comprise a much smaller group than the adolescents who are involved solely in legal political activities (Enosh, Reference Enosh2010 [2008/2009]). However, the fact that the number of activists using illegal political means is fairly small does not make the study of this style of political activity, or its users, less important. Perhaps, quite the opposite is the case.

Illegal political activity is a multifaceted concept that encompasses actions as diverse as property destruction, illegal political graffiti, and building occupation. These political actions can be described in terms of how violent they are (toward property or humans), their direction of attention (toward political opponents or the broader system), and the resources (time, money, reputation) associated with them (Verba et al., Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995; della Porta and Diani, Reference della Porta and Diani1999; Ekman and Amnå, Reference Ekman and Amnå2012). Depending on their points of departure, researchers have understood young people’s involvement in illegal political activities in different ways. Some claim that such activities have their origin in poverty, social alienation, and vulnerability (White, Reference White2007); others claim that they are conscious strategies that ‘demonstrate a strong commitment to an objective deemed vital for humanity’s future’ (della Porta and Diani, Reference della Porta and Diani1999: 176); and still others claim that they are expressions of ‘coming-of-age rebellion’ or ‘youthful immaturity’ (Peterson, Reference Peterson2001). The view taken in this study is that adolescent activists who move beyond legal limits in their attempts to exert political influence are prepared to use whatever means they feel necessary to reach their political goals, an attitude that may be explained by a reluctance to accept authority.

There are reasons to believe that maintaining a stringent distinction between legal and illegal political activities might not permit a correct depiction of politically active adolescents. In fact, some published studies suggest that the two modes of political activity are more closely related than is commonly acknowledged (e.g., Bean, Reference Bean1991). For one thing, illegal political activities have been found to be critically dependent on their legal counterparts. Several studies have indicated that legal political activity precedes involvement in illegal political activity – that is, that activists tend to be involved in legal political activism before they adopt illegal political means (Bean, Reference Bean1991; Moskalenko and McCauley, Reference Moskalenko and McCauley2009; Dahl, Reference Dahl2014; Dahl and van Zalk, Reference Dahl and Van Zalk2014). Dahl (Reference Dahl2014), in an adolescent sample, showed that involvement in illegal political activities was 58% more likely among the adolescents who had reported involvement in legal political activities, 1 year earlier, than among those who had reported no previous involvement. Therefore, for many adolescents, involvement in illegal political activity is about crossing the border – from the legal to the illegal (Moskalenko and McCauley, Reference Moskalenko and McCauley2009). Thus, a relevant research question becomes: what characterizes the adolescents who have crossed the legal-illegal border? This study is an attempt to find some of the missing pieces in the puzzle.

In order to better understand the uniqueness of adolescents crossing the border to illegal political activity, let us start by portraying their similarities to adolescents engaged in legal political activism. From previous research, one would expect that politically engaged youngsters are interested in politics, whether or not they are engaged in legal or illegal political activism (Jennings and Niemi, Reference Jennings and Niemi1974; Brady et al., Reference Brady, Verba and Schlozman1995; Verba, et al., Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995; Dostie-Goulet, Reference Dostie-Goulet2009). Thus, engagement in politics should, at least to some extent, be a reflection of an interest in what goes on in the society one lives in. However, when it comes to illegal political activities, there is a lack of solid empirical evidence for this hypothesis. Some studies claim that illegal political activities are not associated with political interest (Oswald and Schmid, Reference Oswald and Schmid1998; Watts, Reference Watts1999; Gavray et al., Reference Gavray, Fournier and Born2012), whereas others report that political interest is a factor underlying political activities in general, regardless of whether they are legal or illegal (e.g., Schmid, Reference Schmid2012; Dahl, Reference Dahl2014).

Politically engaged adolescents may also be expected to feel that they have the ability to make a change when it comes to political matters (Vecchione and Caprara, Reference Vecchione and Caprara2009; Sohl, Reference Sohl2011). For example, they should feel that they have the capacity to construct and collect petitions if they want to do so. Such a belief in one’s ability to take political action is commonly referred to as a sense of political efficacy. Just like an interest in politics, political efficacy should, in general, bridge the various styles of engagement in politics. That is, the perception of being able to do something that can have an impact on the political process should be largely independent of whether the political activities involved are legal or illegal. Research on political efficacy has shown that, just like the people who are involved in lawful and conventional modes of political activity, those who step beyond the legal limits have high perceptions of their political efficacy (Finkel, Reference Finkel1987; Enosh, Reference Enosh2010 [2008/2009]). In short, political efficacy should be independent of action style – illegal or legal.

A third aspect that might characterize politically engaged adolescents is possession of a clear goal-orientation, or a broader motive for being engaged. As previous research has shown that getting motivated is a crucial step in the process leading to participation in political activity (e.g., Klandermans and Oegema, Reference Klandermans and Oegema1987), it may seem a truism that individuals engaged in politics are driven by political goals. However, what is important here is that having long-term political goals is most likely something that transcends the style in which young people engage in politics (Moskalenko and McCauley, Reference Moskalenko and McCauley2009). This is not to say that adolescents taking the step to include illegal means in their political repertoire share the same underlying motives as young people whose political participation remains legal. Yet, involvement in politics is likely to be driven by political goals, regardless of the means that the activists feel are needed. Thus, like political interest and political efficacy, having longer-term goals may be expected to be largely unrelated to the action style used to exert political influence.

Therefore, in many cases, the goals of adolescents who use legal means in their political expression should be the same as those that drive adolescents who, in addition to pursuing legal political activities, are also involved in illegal political activities. However, one characteristic is likely to differentiate these two groups of adolescents, irrespective of the characteristics of their goals. It is likely that adolescents who cross the border to illegal political activity are more willing to adopt political tactics that may cause damage to other people (Opp and Roehl, Reference Opp and Roehl1990). Adolescents involved solely in legal political activity may argue that breaking the law to change society is sometimes justified. However, the idea that the end justifies the means can be expected to be more acceptable among adolescents involved in illegal political activity. This hypothesis has not yet been tested empirically.

How might we explain that adolescents who are involved in illegal political activities are likely to be more acceptant of the end justifying the means? We do not expect the adolescents who are engaged in legal political activities to be very different from those who are involved in illegal political activities in terms of their political interests, political efficacy, or long-term goals for political engagement. However, we do expect that the adolescents who engage in illegal political activities are more willing to pursue their goals even if this means, in the end, that they may harm other people. Why this is the case remains an open question. We are not aware of any published studies that have addressed this issue before.

We propose here that an explanation for why adolescents who are involved in illegal political activities are more ready to sacrifice other people’s well-being to achieve their political goals is that these adolescents do not readily accept the authority residing in their society, teachers, or parents. The idea that when people perceive an authority as non-legitimate they will challenge that authority has a rich tradition in political science (Easton, Reference Easton1965, Reference Easton1975; Inglehart and Catterberg, Reference Inglehart and Catterberg2002; Harrebye and Ejrnæs, Reference Harrebye and Ejrnæs2013). In a broad sense, a challenge to authority should be understood as an attempt to undermine its legitimacy (Passini and Morselli, Reference Passini and Morselli2009b), and individuals’ challenges of, or disobedience toward, authority may reflect an intention to prevent authority relationships from degenerating into authoritarian ones (Passini and Morselli, Reference Passini and Morselli2009a). When concerned with challenges of authority, it is also important to acknowledge that some modes of disobedience are accompanied by a pro-social agenda, aiming at promoting beneficial social change for everyone. By contrast, anti-social disobedience may reflect the intention to effect change mainly for oneself (Passini and Morselli, Reference Passini and Morselli2009b). Nevertheless, irrespective of whether an individual has a pro- or anti-social attitude, when an authority is perceived as illegitimate, such a perception is likely to go hand-in-hand with a challenge to authority.

In similar vein, anti-social attitudes have been characterized as involving mistrust in authority figures and tolerance of law violations (Butler et al., Reference Butler, Fearon, Atkinson and Parker2007). Such negative attitudes and behavior toward authority may also be transferable across contexts. Stated differently, when adolescents perceive their relationship with their parents in negative terms, such a negative perception is likely to be transferred to relationships with representatives of authority in school (Jaureguizar et al., Reference Jaureguizar, Ibabe and Straus2013). Negative perceptions of parental and educational authorities have repeatedly been shown to be strong predictors of adolescents’ violent behavior against authorities (Musitu et al., Reference Musitu, Estévez and Emler2007; Jaureguizar et al., Reference Jaureguizar, Ibabe and Straus2013). With its potential to be transferred across contexts, a non-legitimization of authority that turns into violence may also arise in relation to other authorities in adolescents’ lives. Compared with their legal counterparts, illegal political activities represent a more distinct challenge to political authority, and we suggest that such a challenge may not stop at crossing the legal–illegal border. Thus, as a challenge to authority, adolescents’ involvement in illegal political activity is also likely to express itself in acceptance of violent political means.

In short, we propose that adolescents involved in illegal political activities can be expected to have more strained relationships with their parents and teachers, and to be more norm-breaking than adolescents who restrict their political activities to ones that are legal in conventional society. In addition, negative perceptions of authority may explain why adolescents who are involved in illegal political activities are willing to accept the ones that potentially cause damage to other people.

Method

Participants and procedure

The data used in this study comprised of questionnaire responses collected from adolescents in a Swedish community with around 130,000 inhabitants. In order to acquire data during the formative years of political socialization, when illegal political activism seems to peak (Watts, Reference Watts1999), we targeted students in middle and late adolescence. The target sample comprised of 1870 adolescents from schools strategically chosen to ensure that there was a balanced gender distribution and an accurate representation of the social and ethnic backgrounds of students on both theoretical and vocational programs in the community. Participants were students in the 9th grade (N=817; M age=15.4, std. dev.=0.52, 86% response rate) and 12th grade (N=740; M age=18.5, std. dev.=0.69, 81% response rate). At the time of data collection, the income level, population density, and unemployment rate in the targeted community were similar to national averages. Only the proportion of young inhabitants (15–24 years) of foreign background in the city was slightly higher than the national average (24% vs. 20%) (Statistics Sweden, 2014). The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Board in Uppsala.

Data collection took place during school hours and was administered by trained research assistants. Teaching personnel were not present during the time the questionnaires were filled in. Participants were informed about the time needed to complete the questionnaire and the content of the items included, and were informed that their participation was voluntary. In addition, participants were assured that their responses would not be seen by others, either parents, teachers, or anyone else. All participating classes received a reimbursement of ~100 euros to their class fund for taking part in the study.

Measures

Political attitudes and activities

The adolescents reported on their involvement in various types of political activities, of which some were legal and some illegal. They stated how often they engaged in each of the following activities during the last 12 months on a three-point scale (0=never, 1=occasionally, and 2=several times). The adolescents also reported on their attitudes toward illegal and violent political activities.

Legal political activities

Involvement in legal political activities was measured by eight items on the study’s list of types of political activities. Examples of items are as follows: ‘attended a meeting concerned with political or societal issues,’ ‘boycotted or bought a certain product for political, ethical, or environmental reasons,’ ‘distributed leaflets with a political content,’ ‘participated in legal demonstration or strike,’ and ‘wore a badge or a t-shirt with a political message.’ Cronbach’s α for this scale was 0.74. Frequencies showed that 31.6% of the adolescents had not taken part in legal political activities during the last year; 27.6% had been involved only once; and 40.8% had been involved more than once.

Illegal political activities

From the different types of political activities reported upon by the adolescents, an illegal political activity scale was created by averaging scores across five items (Dahl and van Zalk, Reference Dahl and Van Zalk2014) (see Table 1). The items were as follows: ‘participated in illegal action, demonstration, or occupation,’ ‘broke the law for political reasons,’ ‘wrote political messages or painted graffiti on walls,’ ‘participated in political activity leading to fighting with political opponents or the police,’ and ‘participated in political activity where property was damaged.’ Cronbach’s α for the illegal political activity scale was 0.85. A majority had not taken part in illegal political activism during the last year (92.8%); 3.4% had been involved only once; and 3.8% had been involved more than once.

Table 1 Frequencies of illegal political activity by cohort

Frequencies and percentages of involvement in illegal political activity for both cohorts. The response scale refers to how often the adolescents stated that they engaged in each of the illegal political activities during the last 12 months (0=never, 1=occasionally, and 2=several times). Due to rounding error, some percentages do not add up to exactly 100.

Breaking the law to change society

This measure was created within the project for the purpose of assessing adolescents’ readiness to use violence in order to exert political influence. We asked ‘What is your opinion concerning breaking rules to change societal matters? If I think that something is wrong …’ The adolescents could choose between the following three response options: (1) ‘I will stay within the law. The Swedish law declares what is right. We must stick to decisions we make together. If something should be changed, it should be done within the boundaries of the law (48.0%),’ (2) ‘I can consider breaking the law. If decisions taken by politicians are wrong, then it is right to break the law. I would consider breaking the law if needed (47.3%),’ and (3) ‘I can consider breaking the law even if other people get hurt. When the law is completely wrong, drastic means are sometimes necessary (4.7%).’

Political interest

We used three questions to assess adolescents’ levels of political interest (Verba et al., Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995): ‘How interested are you in politics?’, ‘How interested are you in societal issues?’, and ‘People have different feelings about politics. What are your feelings?’ The response scale ranged from 1 ‘completely uninterested/loath’ to 5/6 ‘very interested/great fun’ (Cronbach’s α=0.86).

Political efficacy

The adolescents indicated their ability to get involved in political activities on a 10-item scale. More specifically, this measure assessed ‘the perception by an individual of his or her own abilities to execute actions aimed at producing a change in society’ (Sohl, Reference Sohl2011: 394). The stem question was ‘If I really tried, I could …’ with examples such as ‘… help to organize a political protest,’ and ‘… take part in a demonstration in my hometown.’ The response scale ranged from 1 ‘I could definitely not manage that’ to 4 ‘I could definitely manage that’ (Cronbach’s α=0.93).

Goal orientation

To assess the adolescents’ underlying motives for their political activities, we asked them whether their engagement had long-term goals. This measure was created within the project, and the stem question was ‘Some people have set goals for themselves concerning their engagement in societal issues. Have you?’ The adolescents had the following four responses to choose: (1) ‘I will work actively in organizations and I’m already a member of an organization,’ (2) ‘I will definitely work actively (in organizations or by other means) on issues like this but have not yet committed myself,’ (3) ‘I’m not interested in issues like this and, as far as I can see, I will not commit myself to getting engaged in them,’ (4) ‘I’m not interested in issues like this, rather the opposite. I will certainly not commit myself to do anything about them.’

Relations to authorities

We measured relations to authority separately for the societal, school, and parental contexts.

Societal context

Two measures tapped adolescents’ perceptions of societal authorities. The respondents rated their confidence in political institutions and their involvement in law breaking.

Confidence in political institutions. The adolescents were asked three questions about their confidence in institutions in the political system (Linde and Ekman, Reference Linde and Ekman2003). They were asked the following: ‘How much confidence do you have in the following institutions?’ ‘The parliament,’ ‘The government,’ and ‘The courts.’ The response scale ranged from 1 ‘no confidence’ to 4 ‘very high confidence’ (Cronbach’s α=0.91).

Delinquency. Adolescents responded to six items about their delinquent activities during the last year (Kerr and Stattin, Reference Kerr and Stattin2000). Adolescents’ involvement in delinquency can be understood as reflecting frustration due to the lack of autonomy. In order to gain some autonomy, some adolescents challenge the societal authorities by ‘rebelling against institutions they feel display unfairness and aggressiveness, even though this rebellion does not necessarily reveal an efficient and definitive solution’ (Gavray et al., Reference Gavray, Fournier and Born2012: 406). We asked about cases of shoplifting, arrest, property destruction, carrying weapons, threatening others, and skipping payment on buses or at the movies. The response options ranged from 1 ‘no, never’ to 5 ‘more than 10 times’ (Cronbach’s α=0.75).

School context

The adolescents were asked how fair they perceived their teachers to be. Their perceptions have been found to be associated with adolescent delinquency (e.g., Gottfredson et al., Reference Gottfredson, Gottfredson, Payne and Gottfredson2005).

Perception of teachers as unfair. The adolescents responded to six statements about the fairness of their teachers. Item examples were as follows: ‘Most teachers don’t like me,’ and ‘There are scarcely any teachers who praise me when I do a good job.’ The response scale ranged from 1 ‘absolutely disagree’ to 4 ‘absolutely agree.’ (Cronbach’s α=0.82).

Parental context

We asked the adolescents whether they avoided disclosing information to their parents, whether they perceived their parents as cold and rejecting toward them, and whether they were defiant in relation to their parents. All three scales have repeatedly been found to correlate with delinquent behavior (Stattin and Kerr, Reference Stattin and Kerr2000; Kerr and Stattin, Reference Kerr and Stattin2003; Tilton-Weaver et al., Reference Tilton-Weaver, Kerr, Pakalniskeine, Tokic, Salihovic and Stattin2010).

Adolescents’ non-disclosure of information to their parents. Our measure of adolescents’ non-disclosure of information about their whereabouts outside home comprised of five items (Persson et al., Reference Persson, Stattin and Kerr2004). Item examples were as follows: ‘Do you usually tell how school was when you get home (how you did on different exams, your relationships with teachers, etc.)?’ and ‘Do you keep a lot of secrets from your parents about what you do in your free time?’ The response options for this scale ranged from 1 ‘not at all/keep almost everything to myself/never’ to 5 ‘very much/tell almost everything/very often.’ Three of the items were recoded so that higher scores indicated less disclosure of information (Cronbach’s α=0.76).

Parents’ coldness-rejection. This measure (Tilton-Weaver et al., Reference Tilton-Weaver, Kerr, Pakalniskeine, Tokic, Salihovic and Stattin2010) comprised of six statements introduced by the stem question: ‘What does your mother [father] do if you do something she [he] doesn’t like?’ Item examples were as follows: ‘Ignores what you have to say if you try to explain’ and ‘Makes you feel guilty for a long time.’ Adolescents were offered three response options for these statements: (1) ‘never,’ (2) ‘sometimes,’ and (3) ‘usually.’ The adolescents reported on their mother and father separately. As reports for mothers and fathers were strongly associated (r=0.70), the mean of both reports was used when data on both parents were available (Cronbach’s α=0.90).

Defiant behavior. Adolescents’ defiant behavior toward parents was measured using four questions (Persson et al., Reference Persson, Stattin and Kerr2004). Examples of the items are as follows: ‘What do you usually do when your parents ask you to turn off the computer?’ and ‘What do you usually do when your parents tell you to clean up in your room?’ The response scales ranged from 1=‘stop/do it immediately (turn off the computer/clean the room immediately) without complaining or questioning’ to 4=‘don’t listen to what they are saying or don’t care about what they are saying’ (Cronbach’s α=0.71).

Statistical analysis

For the purpose of the study, the adolescents were grouped on the basis of their involvement in legal, illegal or both legal and illegal political activities, or their lack of involvement in legal or illegal political activities. There were only eight adolescents involved in illegal political activities who had not been involved in any legal political activities. As this study was guided by the presumption that illegal political activity is mostly about boundary-crossing, we were interested in the adolescents who had crossed the legal–illegal border in their political engagement. Accordingly, these eight adolescents were excluded from the analytic sample, leaving us with the following three groups: persons not active in either legal or illegal political activities, the not politically active group (n=484); persons involved in only legal political activities (n=961), the legal political activity group; and persons involved in both legal and illegal political activities (n=104), the illegal political activity group. Thereafter, the analyses were performed in two steps.

First, we conducted analyses of covariances (ANCOVAs) with Bonferroni-corrected mean comparisons to examine the extent to which adolescents moving beyond the legal limit in their political engagement were different from adolescents engaged in legal activities only, or from those who were not engaged in either legal or illegal activities. The ANCOVAs included gender as an independent variable and were controlled for age. In addition, we used EXACON software (Bergman and El-Khouri, Reference Bergman and El-Khouri1987) to examine whether adolescents in the three political-activity groups differed in their attitudes toward breaking the law in order to effect change in their society. The EXACON program compares observed and expected frequencies for each predictor–outcome combination cell-wise. If a predictor–outcome combination is observed significantly more often than expected by chance, it is labeled a Type, whereas if a combination is observed significantly less often than expected by chance, it is labeled an Antitype.

In the second step, we created a dichotomized version of our breaking the law to change society measure. In one group (coded 1), we placed adolescents who could consider breaking the law even if other people got hurt (n=72), and in the other group we placed both the adolescents who would stay within the law in their political engagement and adolescents who would consider breaking the law but not if other people might get hurt (coded 0; n=1468). This recoding enabled us to test whether adolescents who are involved in illegal political activities are more ready to sacrifice other people’s well-being to achieve their political goals, compared with adolescents involved in legal political activities only. We used logistic regression models that predicted (a) whether political activity predicts adolescents’ approval of political violence and (b) whether the effect of political activity on adolescents’ approval of political violence is reduced or disappears after controlling for adolescents’ challenges to authority.

Results

Table 1 shows the frequencies of adolescents’ involvement in illegal political activity. As can be seen from this table, involvement in illegal political activity is rare. Yet, some adolescents in both cohorts reported engaging in politics in illegal ways.

Differences and similarities in political interest and attitudes between the three groups of not politically active, legally politically active, and illegally politically active adolescents

The first step in the analysis was to compare adolescents in the three political-activity groups with regard to political interest, political efficacy, and goal-orientation, including gender as an independent variable and after controlling for age (see Table 2). Because some of the scales, and other subsequent scales, had items with different sets of responses, we standardized the individual items before adding them to their scale.

Table 2 Means of the political interest and attitude variables according to type of adolescent political activity after controlling for age (Z-scores)

ANCOVA=analyses of covariance.

a,b,cSuperscripts indicate significant differences (P<0.05) between the groups. Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons.

***P<0.001.

The results of the ANCOVAs, reported in Table 2, show that there were differences between the three groups in terms of political interest, political efficacy, and goal-orientation (P<0.001). We had expected the adolescents involved in illegal political activities to have about the same levels on these measures as the adolescents involved in legal political activities: This was true for political efficacy; however, contrary to our expectations, adolescents involved in illegal political activities reported significantly greater political interest and goal-orientation than adolescents involved in legal political activities. It should be noted that, on all three measures, the adolescents who had been involved in legal or illegal political activities differed significantly from those who had not been involved in political activity of any kind. With regard to gender, girls reported significantly higher political efficacy, F(1, 1506)=6.01, P=0.014 and goal-orientation F(1, 1506)=6.32, P=0.012 than boys. There were no significant interaction effects (P>0.05) of gender and political activity. Altogether, the results suggest that adolescents who cross the legal border in their political engagement are at least as interested, efficacious, and goal-oriented as their legally oriented counterparts. Indeed, their political interest and goal-orientation were found to be higher than those of adolescents who had been involved only in legal political activities.

In addition, we used the EXACON program (Bergman and El-Khouri, Reference Bergman and El-Khouri1987) to examine whether adolescents in the three political-activity groups differed in their attitudes toward breaking the law in order to change society. Table 3 shows that non-active adolescents reported more often than expected by chance that they would stay within the law when trying to change society (a significant type), and less often than expected by chance that they would consider breaking the law to change society (a significant antitype). No observed frequencies were significantly different for the adolescents involved in legal political activities compared with the other adolescents. The adolescents involved in illegal political activities, however, reported less often than expected by chance that they would stay within the law (an antitype), and more often than expected by chance that they would break the law even if other people got hurt (a type) when trying to change society. In sum, the main aspect of these results is that, compared with adolescents not active in politics and adolescents involved in legal political activities, adolescents involved in illegal political activities are more willing to break the law even if other people get hurt.

Table 3 Exacon results showing differences in attitudes toward breaking the law to change society across not politically active adolescents, adolescents involved in legal political activity, and adolescents involved in illegal political activity (n=1519)

T=significant type; A=significant antitype.

Bonferroni-adjusted P=0.005556.

The complete wording of the response options were as follows:

aI will stay within the law. The Swedish law declares what is right. We must stick to decisions we make together. If something should be changed, that should be done within the boundaries of the law.

bI can consider breaking the law. If decisions taken by politicians are wrong, then it is right to break the law. I will consider breaking the law if needed.

cI can consider breaking the law even if other people get hurt. When the law is completely wrong, drastic means are sometimes necessary.

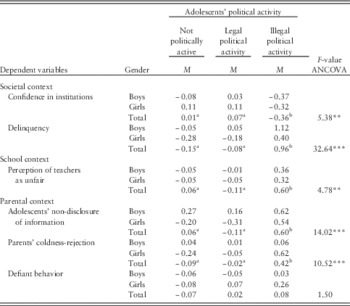

Differences and similarities in relation to authority between the three groups of not politically active, legally politically active, and illegally politically active adolescents

We have argued that one reason why some adolescents cross the border of legality is that they do not readily accept authority. We expected the adolescents involved in illegal political activities to differ from their legally oriented counterparts in their relation to authority. We measured challenges to authority in the following three different contexts: societal, school, and parental.

Table 4 shows that, after controlling for age, the values of the measures of societal context – confidence in political institutions and delinquency – differed significantly between the three groups. Bonferroni-corrected mean comparisons showed that the adolescents involved in illegal political activity reported significantly lower levels of confidence in political institutions and significantly higher levels of delinquent behavior than members of both the other groups. The pattern was the same for perception of teachers as unfair, with the mean comparisons showing that the adolescents involved in illegal political activity perceived their teachers as significantly more unfair. In the parental context, there were no differences in defiance between the three groups. However, on the two remaining measures – coldness-rejection and adolescents’ non-disclosure of information about daily activities – there were significant overall differences. The adolescents involved in illegal political activities reported more coldness-rejection and less disclosure than the other two groups of adolescents.

Table 4 Means of the authority-relation variables according to type of adolescent political activity after controlling for age (Z-scores)

ANCOVA=analyses of covariance.

a,bSuperscripts indicate significant differences (P<0.05) between the groups. Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons.

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

We also found some gender differences with regard to authority relations. Boys reported significantly higher levels of delinquency, F(1, 1435)=25.69, P<0.001 and non-disclosure, F(1, 1435)=14.27, P<0.001 than girls. In addition, there was a significant interaction effect of political activity and gender on coldness-rejection F(1, 1435)=14.27, P<0.001. Independent samples t-tests showed that, although girls’ coldness-rejection differed across the three political-activity groups (not politically active, M=−0.24; legal political activity, M=−0.05; illegal political activity, M=0.62), the coldness-rejection of boys was significantly different only between those involved in legal and illegal political activity (not politically active, M=0.04; legal political activity, M=0.01; illegal political activity, M=0.06). In short, with the exception of one of the indicators of parental context, the adolescents involved in illegal political activities reported more attitudes and behaviors that constituted challenges to authority than adolescents involved in legal political activities or adolescents who were not politically active. For the most part, on these measures, adolescents involved in legal political activities did not differ from the adolescents who had not been politically active.

Why do adolescents involved in illegal political activity show greater approval of political violence?

As the main difference between the three groups of adolescents with regard to breaking the law to change society mainly concerned whether the adolescents involved in illegal activities were willing to approve of political violence, we used a dichotomized measure to separate the adolescents according to their attitudes toward political violence. In the first step of our logistic regression analysis, we regressed the measure of approval of political violence on the three-category political-activity variable (not politically active, involved in legal political activities, and also involved in illegal political activities). The adolescents involved in legal political activity formed the reference group. As shown in Table 5, compared with the adolescents involved in legal political activity, the adolescents not involved in political activity at all did not approve more of political violence (OR=0.62; P<0.14). Adolescents involved in illegal political activity, however, were almost four times more likely to approve of political violence (OR=3.94; P<0.001) compared with legally oriented activists. This suggests that there is a greater likelihood that adolescents involved in illegal political activities are ready to use violent political means compared with adolescents involved in legal political activities.

Table 5 Logistic regression model predicting approval of political violence from the measures of political activity and challenges to authority controlling for age

Adolescents involved in legal political activity were used as the reference group. At Step 2, measures of challenges to authority were entered using Wald’s forward stepwise selection.

If challenges to authority explain why adolescents involved in illegal political activities are more ready to use political violence, then there should not be an association between involvement in illegal political activities and approval of political violence once challenges to authority are entered into the equation. Because the six measures of challenge to authority are likely to account for much of the same variance, we entered the challenge measures using Wald’s forward stepwise selection procedure. As seen in the second step depicted in Table 5, in the final model of the stepwise procedure, three measures of challenge to authority – delinquency (OR=1.23, P<0.05), perception of teachers as unfair (OR=1.35, P<0.05), adolescents’ non-disclosure of information to parents (OR=1.45, P<0.05) – predicted approval of political violence. However, there was still a significant effect of involvement in illegal political activities (OR=2.27; P<0.05). In sum, the effect of involvement in illegal political activity on approval of political violence was reduced considerably once the adolescents’ challenges to authority had been controlled for, but the effect did not disappear entirely. This suggests that the approval of political violence observed among adolescents involved in illegal political activity can be partially, but not totally, explained by non-acceptance of authority.

Discussion

Previous research shows that legal political activities are not regarded as sufficiently effective by all the young people who try to exert political influence. Accordingly, some also include illegal political means in their political repertoire (Cameron and Nickerson, Reference Cameron and Nickerson2009; Enosh, Reference Enosh2010 [2008/2009]; Gavray et al., Reference Gavray, Fournier and Born2012). In this study, we used a sample of 1557 Swedish adolescents in an attempt further to understand what is characteristic of adolescent activists who cross the legal–illegal border. Non-active adolescents, adolescents involved in legal political activities, and adolescents involved in illegal political activities were compared with regard to their political interest, political efficacy, goal-orientation, challenges to authority, and disposition to break the law in order to effect change in society. In what ways are adolescents involved in illegal political activity similar to adolescents solely involved in legal political activity? Contrary to our expectations, the illegal activists reported higher levels of political interest and goal-orientation than the adolescents involved in legal political activity. The political-efficacy level of adolescents involved in illegal political activity was also higher, but this difference was not significant. Compared with the non-active adolescents, irrespective of the political means used, politically active adolescents reported higher levels on all three measures. The adolescents involved in illegal political activity also seemed to have different attitudes toward authority. Regardless of context – societal, school, or parental – these adolescents seemed to challenge the authority in question. The fact that adolescents’ involvement in illegal political activities can be understood as a form of critical questioning of, or a challenge to, societal norms and authority is an interpretation that fits well with theories of political participation (e.g., della Porta and Diani, Reference della Porta and Diani1999; Inglehart and Catterberg, Reference Inglehart and Catterberg2002). Finally, perhaps the most striking result is that adolescents involved in illegal political activity seem to be more ready to accept political means that might lead to other people getting hurt. We conclude that part of the reason why they hold such an attitude is that they have consistently negative attitudes toward authority.

One main presumption underlying this study was that adolescents involved in illegal political activities are more acceptant of violent means to change society. We argue that, given the violent manner in which adolescents with negative attitudes toward authority have been found to behave (Musitu et al., Reference Musitu, Estévez and Emler2007; Jaureguizar et al., Reference Jaureguizar, Ibabe and Straus2013), those involved in illegal political activities are more likely, as a challenge to political authority, to be ready to accept means that can hurt people when trying to exert political influence. It seems as if a negative attitude toward authority stretches from the family, through school, to the political system. The fact that more adolescents involved in illegal political activities than expected seem to be acceptant of political means that may hurt other people suggests that, for at least some of them, their use of illegal political means is not accompanied by an appreciation of democratic values – for example, equal rights for all. Stated differently, for some adolescents involved in illegal political activities, challenges to authority are rooted in a stance of anti-social disobedience (Passini and Morselli, Reference Passini and Morselli2009b). In a sense, acceptance of political violence indicates that these young people support the idea that, in order to attain a political goal, the ends sometimes justify the means.

These findings can also be understood in the light of what della Porta and Diani (Reference della Porta and Diani1999) have suggested is the meaning of violence in political activity. In addition to attracting attention and winning specific battles, the use of violent political means can also be understood as having a symbolic value. The idea is that violent protest, for example, can be justified as a symbolic rejection of an oppressive system (della Porta and Diani, Reference della Porta and Diani1999). Similarly, Passini and Morselli (Reference Passini and Morselli2009a) argue that disobedience can be an approach aimed at stopping a relationship with an authority turning into an authoritarian one. On the part of adolescents involved in illegal political activity, and much in line with the argument of Passini and Morselli, the acceptance of harmful political means can thereby be understood in terms of a will to demonstrate that a political authority is non-legitimate. However, as the use of violent political means often gives rise to the alienation of sympathizers and public condemnation (Wolfsfeld et al., Reference Wolfsfeld, Opp, Dietz and Green1994), the extent to which such an attitude is realized in practice can be questioned.

In our attempts better to understand the characteristics of adolescents involved in illegal political activity, we found that these adolescents were equally efficacious, but contrary to our expectations they were more interested in politics and more motivated to reach their goals compared with their legally oriented counterparts. These findings indicate that, irrespective of whether the resources required to offset the costs of public condemnation are political skills, motives, or means, illegal political actions are likely to demand more from the activists themselves than are legal political actions (Sherkat and Blocker, Reference Sherkat and Blocker1994; Wolfsfeld et al., Reference Wolfsfeld, Opp, Dietz and Green1994). Turning to gender differences, the most prominent result was that girls had a greater perception of their political efficacy than boys, although, in general, males express higher political efficacy than females (Verba et al., Reference Verba, Burns and Schlozman1997; Vecchione and Caprara, Reference Vecchione and Caprara2009). Although the interaction was not significant, the mean values for political efficacy suggest that there are likely to be differences between the girls (M=0.70) and the boys (M=0.14) involved in illegal political activity (see Table 2). To the knowledge of the author, only one previous study has examined gender differences with regard to political efficacy and illegal political activity (Enosh, Reference Enosh2010 [2008/2009]). The results of Enosh (Reference Enosh2010 [2008/2009]) show that political efficacy weakly predicts, for both genders, a willingness to take part in illegal political activities. We also found a significant interaction suggesting that girls who perceived their parents as increasingly cold and rejecting became more engaged in political activity. For boys, the only difference was that the ones involved in illegal political activity were more inclined to perceive their parents as cold and rejecting. In accordance with previous research on the impact of gender on adolescents’ political socialization, these findings indicate that girls and boys perceive their involvement in political activity in different ways (Mayer and Schmidt, Reference Mayer and Schmidt2004). To be able to speculate further about the potential effects of gender, additional research is required. In sum, adolescents are likely to perceive involvement in illegal political activity as more demanding than involvement in legal political activity. In addition, there may be a need to further examine the connection between political efficacy and illegal political activity in adolescence. At present, knowledge is insufficient.

This study has some limitations that need to be addressed. Its cross-sectional design does not permit conclusions to be drawn with regard to the direction of effects. Adolescents’ illegal political activism that seems to differ from their legal political activism cannot lead us unambiguously to draw the conclusion that the differences underlying the two styles of political action are the triggers to adolescents becoming involved in illegal political activities. A longitudinal study design is needed to address the issue. In addition, the generalizability of the findings reported in this study should be discussed. The current sample was one of Swedish adolescents. We should, therefore, be cautious in generalizing findings based on this sample to adolescents living in other contexts and countries. What we can say, however, is that the study offers a theoretical framework that might be used in future studies of adolescents involved in illegal political activity. Finally, although illegal political activity is a complex concept, comprising some very different kinds of actions, we did not distinguish conceptually between illegal political activities of various types. However, the items underlying the construct of illegal political activity used in this study have been employed elsewhere with adequate results (Dahl, Reference Dahl2014; Dahl and van Zalk, Reference Dahl and Van Zalk2014). In addition, whenever the phenomenon is examined empirically, it is shown that, irrespective of the sometimes diverse natures of the items, dispositions to illegal political activities come together on a single scale with adequate psychometric properties (Corning and Myers, Reference Corning and Myers2002; Moskalenko and McCauley, Reference Moskalenko and McCauley2009).

In addition to these limitations, there are some strengths to the study. First, we used a large sample of adolescents with different social and ethnic backgrounds. Consideration of the relation between legal and illegal political activities has a rich tradition in research on political participation (e.g., Barnes and Kaase, Reference Barnes and Kaase1979; Bean, Reference Bean1991). However, only a few studies (e.g., Enosh, Reference Enosh2010 [2008/2009]; Gavray et al., Reference Gavray, Fournier and Born2012) have examined how people involved in illegal political activities differ from legally oriented activists in adolescence – the age period when the preference for illegal political means seems to peak (Watts, Reference Watts1999). Accordingly, given the infrequent nature of illegal attempts to exert political influence, conducting empirical inquiries on an adolescent sample seems optimal. In addition, due to the infrequent nature of illegal political activity, previous studies have usually asked respondents about their intention to, or attitude toward, these political means (e.g., Kuhn, Reference Kuhn2004). However, it is not necessarily the case that an intention to participate is realized in actual behavior. Barnes and Kaase (Reference Barnes and Kaase1979), for example, have argued that the more controversial the behavior in question is, the lower will be the attitude–behavior congruence. In this study, therefore, we used adolescent reports of actual illegal political activity in our attempts to address the differences between politically active adolescents who cross the legal–illegal border and those who do not.

To conclude, most politically active adolescents are solely involved in legal political actions. Later on, however, some may find that the established political channels are not responsive to their demands or to what they have to say, which may prompt them to include means that lie beyond the legal border. Based on the results of this study, we support the position maintained in previous research holding that involvement in illegal political activity is about crossing borders (Bean, Reference Bean1991; Moskalenko and McCauley, Reference Moskalenko and McCauley2009; Dahl and van Zalk, Reference Dahl and Van Zalk2014). The main difference between legal and illegal activists, as we conclude from this study, is that the adolescents involved in illegal political activity seem to be ready to break the law even if it means hurting other people at the same time. That attitude was found to be far less common among the adolescents involved solely in legal political activity. Such a stern position – that is, that of letting the ends justify the means – may very well be accompanied by a perception of the authorities as non-legitimate.

Acknowledgments

This study was made possible by access to data from the Political Socialization Program, a longitudinal research program at YeS (Youth & Society) at Örebro University, Sweden. Professors Erik Amnå, Mats Ekström, Margaret Kerr, and Håkan Stattin were responsible for the planning, implementation, and financing of the collection of data. The data collection and the study were supported by grants from Riksbankens Jubileumsfond. The authors greatly acknowledge Sevgi-Bayram Özdemir and Metin Özdemir for their helpful comments and assistance.