Antonín Dvořák (1841–1904) inscribed the score of his St Ludmila oratorio with the following pointed remark: ‘completed in the days when The Cunning Peasant (Šelma sedlák, op. 37, 1877) was executed in Vienna’.Footnote 1 In this statement, Dvořák is referring to the 1885 Viennese premiere of his comic opera – an event that incited riotous behaviour in the audience and brought forth harsh criticism in the Viennese press.Footnote 2 According to newspaper reports, a group of protestors in the upper galleries of the Hofoper showed their disapproval of The Cunning Peasant by whistling and hissing throughout the performance, which caused such a disruption that several of them were arrested. Some Czechs were also in attendance, and their hearty applause allegedly provoked the protestors to even louder demonstrations. The opera was given a second performance in Vienna – this time to a nearly empty house – before being withdrawn. The drop in attendance at the opera's reprise was likely triggered, at least in part, by poor reviews, since critical assessments generally played a large role in determining Viennese public opinion of a work.Footnote 3 As stated by one critic writing for the Czech daily Národní listy, ‘the Viennese audience … swears by the newspapers, and already during [the] second performance of Dvořák's opera the theatre was empty’.Footnote 4

While Dvořák's reception in Vienna prior to this event had not been without its complications, the riot brought about by The Cunning Peasant was unprecedented for Dvořák. David Brodbeck has suggested that the opera's negative reception had less to do with The Cunning Peasant than with the politics in Vienna during the 1880s.Footnote 5 At a time when the Czech nationalist cause was gaining ground and Austrian minister-president Eduard Taaffe had granted the Czechs certain small concessions, many Germans in Austria felt compelled to reject anything that might pose a threat to the privileged status of German language and culture. Based on this analysis, it would appear that Dvořák's fate was sealed long before the first notes of The Cunning Peasant were sounded at the Vienna Hofoper. Yet the incident takes on new meaning when considered from the perspective of the Czech critics who followed Dvořák's international career with great interest and were eager to voice their own opinions on the matter in the newspapers and journals of Prague. By and large, these Czech critics remained unconvinced that all Czech operas – whether by Dvořák or by another composer – would have been greeted with the same kind of disdain. Although the Czechs were often the first to acknowledge that Viennese judgement could be clouded by blind prejudice, the critics were unanimous in declaring that the fault lay mainly in the decision to stage The Cunning Peasant rather than another opera. These views, as expressed in the Czech press, are significant not because they offer a more plausible explanation for the riot, but because of what they reveal about the Czech critics themselves and their attitudes towards The Cunning Peasant in the 1880s.

Inspired by this extreme incident to speak perhaps more candidly than usual, the critics address many broader issues in their reviews. Implicit in their discussions are various assumptions about the nature of Czech opera and its suitability for international performance as well as questions about Dvořák's place within the Czech operatic canon. More particularly, the reviews cast a spotlight on the strained position of Czech composers vis-à-vis Vienna, especially in the realm of opera – a genre that was not easily exportable – with critics articulating theories and strategies on how to break through on the coveted Hofoper stage in the future. In this way, then, The Cunning Peasant provides a snapshot of the unique challenges of transnational opera performance.

‘Preventing Czech music from appearing in Vienna’: political contexts for the Hofoper riot

Success at the Vienna Hofoper eluded Dvořák for a number of reasons, not the least of which was the political situation of the time. Brodbeck argues that the rioters, who were members of a radical pan-German student movement, were motivated to action not by The Cunning Peasant itself, but by the composer's nationality.Footnote 6 Proof for this claim is provided by Viennese critic Josef Königstein, who writes in his review of the opera for the Illustriertes Wiener Extrablatt that yellow slips of paper were passed out among the students in advance of the performance, urging them ‘to prevent Czech music from appearing in Vienna’.Footnote 7 Königstein also points out that the police were on hand at the theatre, anticipating that a riot might break out. As Königstein puts it, ‘the police were informed of the scheme and about thirty detectives … were assigned to the gallery … the police brigade at the sentry post in the Giselastraße had been increased considerably in order to nip every outbreak of scandal in the bud’.Footnote 8 This suggests that the protests were premeditated – planned before these students actually had a chance to familiarise themselves with Dvořák's opera.

In general, the pan-German movement, of which these students were a part, was acquiring momentum in Austria during the 1880s under the leadership of Georg von Schönerer. Although the movement had already attracted a considerable following during the 1860s and 1870s, it intensified after Eduard Taaffe took up the office of Austrian minister-president in 1879 and initiated certain policies to appease the Czechs.Footnote 9 Three measures in particular helped Taaffe win the support of the Czechs in the early 1880s.Footnote 10 The first was the Stremayr Language Ordinance, which came into effect in April 1880, establishing Czech, as well as German, as an external administrative language in Bohemia and Moravia.Footnote 11 This meant that citizens residing in the linguistically mixed parts of these regions were able to communicate with government officials in Czech. The second measure was a change to the election system, which granted Czechs a greater degree of control in the Bohemian Diet.Footnote 12 The third was the division in 1881 of Prague University into two distinct Czech and German institutions. Naturally, these measures sparked resentment among the Germans in Austria.Footnote 13 William McGrath claims that Taaffe's polices drove most of the remaining moderates among the students in Vienna to radical pan-Germanism, and though they would later distance themselves from it, many of Austria's leading German intellectuals were involved in the deutschnational movement in their youth.Footnote 14 As Pieter Judson points out, many of the politicians who emerged in the 1880s ‘owed much of their ideological arsenal to the dogmatic Schönerer’.Footnote 15 Apart from advocating closer partnerships with Germany, these pan-Germans devised the so-called Linz programme, which called for reform to the taxation system, the introduction of legislation to protect the interests of the lower classes, and an extension of the franchise. In addition to these demands, it proposed a change to the borders of Austria, to exclude two outlying Slav territories so that German populations might be in a majority. Such an arrangement would ensure the continuation of German hegemony within the Habsburg monarchy. Even though the Linz programme did not materialise and the pan-Germans ultimately had very little political power, they had a strong ideological impact, as demonstrated by the riot at the performance of The Cunning Peasant.Footnote 16

The opera's harshest Viennese critics, such as the rioters, belonged to a new generation of German liberals, who subscribed to an increasingly ethnic, rather than civic, view of nationalism.Footnote 17 Whereas older critics such as Eduard Hanslick (1825–1904) and Ludwig Speidel (1830–1906) held to a traditional liberal ideology that was more inclusive and willing to grant status to any work that might be thought to display certain ‘German’ traits,Footnote 18 the younger generation – represented by critic Theodor Helm (1843–1920) – were moderate German nationalists who held a considerably narrower view of German identity. Instead of seeing Germanness as something that might be attained through education and acculturation, these liberals thought of German identity as inbred and unchangeable and were thus predisposed to disapprove of any Dvořák opera because it was not German.Footnote 19 Such a stance is demonstrated in Helm's review for the Deutsche Zeitung, where he writes that ‘in this music is found, in addition to many trivialities that please only a Slavic-national ear, many pretty melodies and a number of fine orchestral effects as well’.Footnote 20 This statement is dripping with condescension, implying that while the ‘many trivialities’ in the music might pass muster with the unrefined Slavs, they could not possibly garner the interest of the more sophisticated Viennese audience. Though Helm concedes that the music has some merits, he dismisses the work completely in his final assessment, deeming it to be entirely undeserving of such a fuss; in his words, ‘the utter dramatic worthlessness of the Dvořák-Veselý opus is not worth partisanship for or against’.Footnote 21 Robert Richard is even more severe in his review of the work for the Deutsche Kunst & Musik-Zeitung, describing The Cunning Peasant as having been ‘devoured’ by the Viennese public. He follows this up by commenting that while the phrase ‘speak no ill of the dead’ normally holds true, this is not possible for The Cunning Peasant, where everything is bad.Footnote 22 Such a categorical rejection of the work in all of its particulars suggests that the politics of the day had clouded his judgement. With the exception of a few traditional liberals such as HanslickFootnote 23 and Königstein, who ends his review by asserting that ‘what is beautiful remains beautiful whether it was created by a Russian or a German, an Italian or a Czech’,Footnote 24 the politically driven German critics and protestors seemed determined to make a scandal of The Cunning Peasant. Dvořák was not given an opportunity to redeem himself on the Hofoper stage, since the event marked the one and only time that a Dvořák opera was to be performed in Vienna during the composer's lifetime.

‘Die kleine Oper war für das Prager czechische Publikum geschrieben’

In the aftermath of the event, Czech critics were quick to offer their interpretations. While opinions differed in their details, these Czech critics agreed that the whole Viennese affair might have been avoided if a different opera had been selected for performance. They considered The Cunning Peasant to be inappropriate because it was too overtly Czech for Vienna, as it had been designed to appeal to the tastes of audiences at the Provisional Theatre (Prozatimní Divadlo) in Prague, where it was premiered in January 1878.Footnote 25 Hanslick himself acknowledges as much, declaring in his 1885 review of the work that ‘the small opera was written for the Prague Czech public’.Footnote 26 That Hanslick considered Czech audiences to be provincial is well known; he had once written to Dvořák, ‘it would be desirable for your things to become known beyond your narrow Czech fatherland, which in any case does nothing for you’.Footnote 27 In some respects, Hanslick seems to be raising a very real practical concern in both The Cunning Peasant review and his early letter to Dvořák, suggesting that the composer's works would have a relatively small chance of being widely disseminated if they were designed for a specifically Czech audience and written on a Czech text. In other words, Hanslick knew that Dvořák's Czech operas were not likely to have as wide a reach as those that were written in German, French or Italian – languages that were considered to be ‘Weltsprachen’. At the same time, an element of cultural snobbery is certainly palpable in Hanslick's writing. Even his description of The Cunning Peasant as a ‘small’ opera has connotations of inconsequentiality.Footnote 28 Whatever his opinion of the Provisional Theatre public, Hanslick agreed with his Czech colleagues on one point: Dvořák's opera was inseparable from its context in late 1870s Prague.

Hanslick continues his critique of The Cunning Peasant, by stating that ‘the subject, the character of the music, suggest that a small stage ought to be used’.Footnote 29 While the small scale of the work, in terms of spectacle, was considered to be problematic on the large stage of the Vienna Hofoper, it was entirely appropriate for the Prague Provisional Theatre. Built on a site that measured a mere thirty-two by twenty metres, the Provisional Theatre could seat no more than 362 people, with standing room for an additional 340.Footnote 30 Smetana voiced frequent complaints in the newspaper Národní listy in the early 1860s about the narrowness of the stage, the distorted acoustics resulting from the theatre's small size, and above all the limited space allotted to the orchestra.Footnote 31 By the 1870s, however, composers had learned to cope with the venue's dimensions and designed their operas accordingly. Though calling for nine soloists, The Cunning Peasant is not a particularly small opera by Provisional Theatre standards.Footnote 32 More so than his contemporaries, Dvořák gives a substantial role to the opera chorus, integrating choral passages into the whole work, rather than confining them to the opening and finale as was the usual practice in Czech comic operas at that time. The chorus is often split into male and female ensembles, alternating on the stage, which also betrays a sensitivity to the limitations of this performing space.

Another aspect that troubles Hanslick is the length of The Cunning Peasant; in his review, he points out that ‘[the work] does not fill an evening at the theatre’.Footnote 33 Though short in Hanslick's estimation, the length of Dvořák's opera was not exceptional in Prague at the time of its premiere. Written in two acts, The Cunning Peasant aligns itself with several other Czech comic operas of the 1870s, including those works in the genre by Bedřich Smetana (1824–84) that had directly preceded it: Two Widows (Dvě Vdovy) performed at the Provisional Theatre in 1874 and The Kiss (Hubička) from 1876.Footnote 34 Taking approximately two hours to perform, The Cunning Peasant was not generally regarded in the Czech press as unusually short.Footnote 35 The reviewer for the Prague daily Pokrok even describes the work's length as optimal, noting that ‘the brevity of some sections does not leave the listener unsatisfied, nor does the long duration of others tire the listener out’.Footnote 36 Though Czech critics waged discussions on other issues concerning The Cunning Peasant, including the relative proportions of the two acts,Footnote 37 the work's division into scenes,Footnote 38 and its dramatic pacing,Footnote 39 none of the reviewers in Prague during the 1870s saw the opera's length as inadequate for an evening's performance.

In its scope and length, then, The Cunning Peasant is not unlike other Czech comic operas from the era of the Provisional Theatre, but it nevertheless triggered a unique response from the public when it was first staged in Prague in 1878. The critic for Pokrok describes the memorability of the tunes in The Cunning Peasant: ‘the melodies have such an impact’, writes the reviewer, ‘sounding fresh, original, and yet so familiar to the Czech ear, such that they stay with the listener for a long time afterward, haunting one in an almost intrusive manner’.Footnote 40 These impressions are corroborated in Národní listy, where the reviewer speaks of the audience being ‘electrified’ by the work's ‘fresh, melodious character of a purely national spirit, which can be heard in almost every tune’.Footnote 41 Critic František Pivoda (1824–98) also comments on the extraordinary reaction of the audience to the ‘songs’ in Dvořák's opera: ‘the public is taking a great interest in this new work’, he asserts, ‘[greeting it] every time with very good attendance, giving it undivided attention from the beginning … to the end. That Dvořák's songs entertain and in parts … move [the audience] is evident on all faces.’Footnote 42 Another reviewer observes that Dvořák's ‘folk-inspired’ melodies have ‘a powerful impact on the Czech-Slavonic ear’.Footnote 43 As these examples show, the opera's tunefulness was prized in the Prague press during the work's first run.Footnote 44 While many Czech critics of the 1870s advocated a continuous approach to melodic construction in the realm of serious opera, taking their directions from Wagner, most of them agreed that ‘melodious’ works fared better with audiences in the realm of comic opera.Footnote 45 The Cunning Peasant was proof of this.Footnote 46

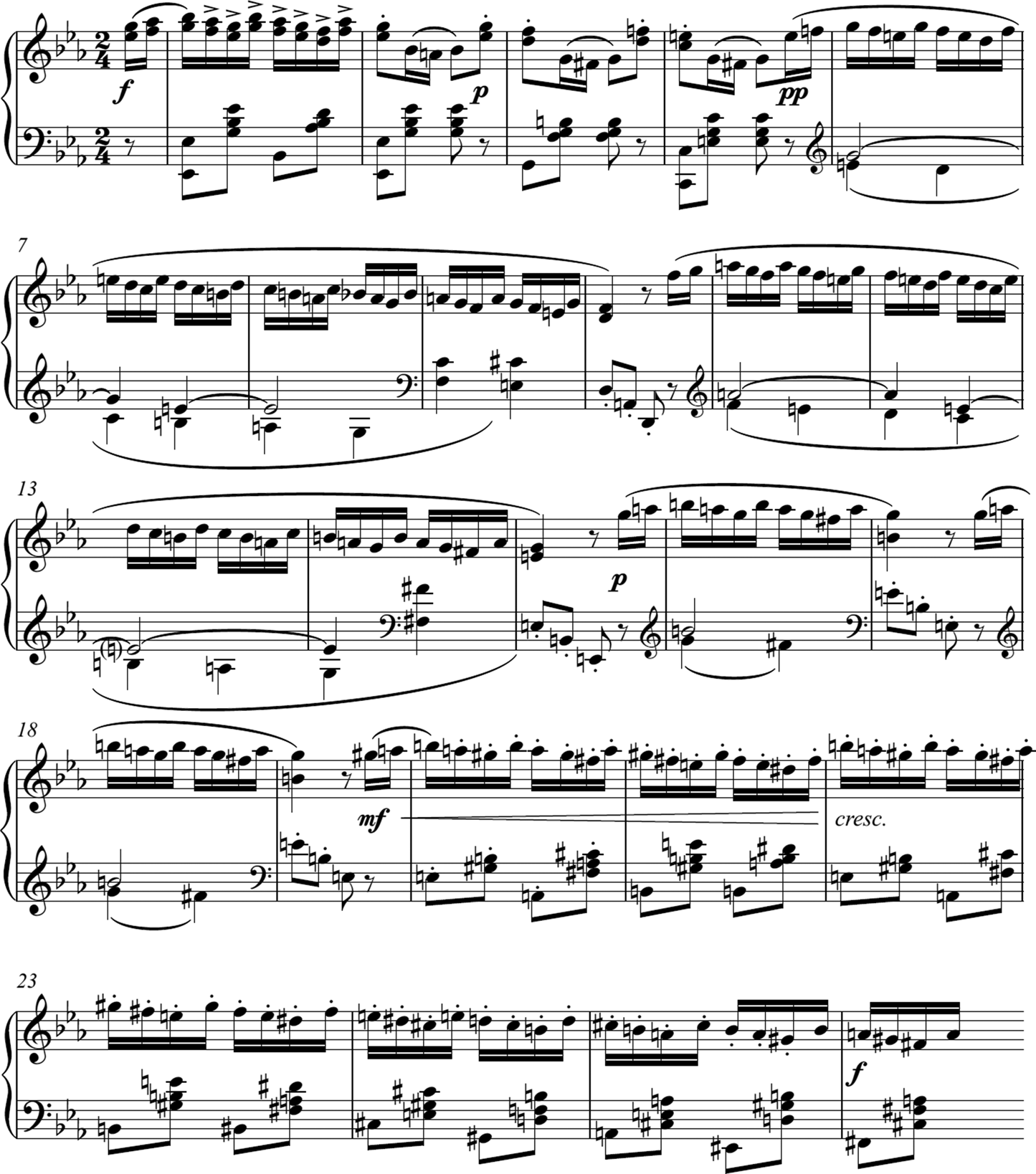

Pleasing the audience was indeed a high priority in The Cunning Peasant, as demonstrated by an adjustment that was made to it in later years. Following its premiere, the critic for Pokrok singled out the ballet music in the first scene of the second act, predicting that it will seem too ‘dark and learned’ for many listeners.Footnote 47 The passage begins and ends in E flat major, but modulates to both closely related and distant keys, venturing as far afield as E major. These changes of key are managed through a series of sequences, which may have seemed excessive to the reviewer. The tonally unsettled impression of this passage is compounded by a slight sense of rhythmic disorientation, as several of the phrases have irregular lengths (Example 1). This ballet music was replaced with Dvořák's more conventional sounding Slavonic Dance, op. 46, no. 3 in A flat major for the opera's three performances in autumn 1880. Though it is unclear whose decision this was, critic Václav Vladimír Zelený (1858–92) claims that the choice was made in the interests of the audience.Footnote 48

Example 1. Excerpt from the Ballet from Dvořák's The Cunning Peasant, Act II scene 1.

In addition to catering to the tastes of the Prague public, The Cunning Peasant seems to reflect the politics that were at play specifically at the Provisional Theatre during the 1870s. The work was written at a time when the more progressive political party in the Czech lands – the Young Czechs (Mladočeši) – had become prominent in the management of the theatre, and its adherents strongly favoured the operas of Smetana, who was himself a supporter. Though the term ‘Young Czech’ was in use as early as 1863, the Young Czech Party was not founded officially until 1874 as an alternative to the National Party, which by default became known as the Old Czech Party (Staročeši).Footnote 49 In essence, the Old Czechs believed that it was in the best interests of the Czech people to remain under Austrian rule, working within the framework of the Habsburg monarchy and in cooperation with the Bohemian nobility.Footnote 50 In contrast, the Young Czech Party advocated a greater degree of liberty for the Czech people, stating in their programme that they wished to achieve ‘the recognition and realisation of the independence and self-government of the Czech lands on the basis of valid and inviolate state rights’.Footnote 51 The Young Czechs disapproved of aristocratic privileges, had no desire to work with the Bohemian nobility and pushed for separation of church and state.Footnote 52 Given the Young Czech presence at the Provisional Theatre during this time, it seems to be no coincidence that Dvořák decided to invest his energies in composing an opera that was more in line with Smetana's operatic approach than any of his earlier works in the genre had been. Moreover, a change in administration occurred at the Theatre in April 1876: Rudolf Wirsing, a Young Czech, took over as director, and the Theatre's Consortium (Družstvo), which had formerly had many Old Czechs as members, now had a strong Young Czech presence. This led the Old Czechs to boycott opera productions at the venue for nearly a year. The boycott had an impact on the reception of Dvořák's grand opera Vanda, premiered in April 1876, right after the change in leadership. Prague's leading critic, Otakar Hostinský (1847–1910), claims that the effects of this dispute were still felt in November of that year, when Smetana's comic opera The Kiss was given: ‘about half of the Czech audience did not even set foot in the theatre’.Footnote 53 Eventually, a United Consortium (Spojené Družstvo) was formed at the Provisional Theatre in 1877, with representatives from both political groups.Footnote 54 Though it would appear that the conflict had been pacified by the time The Cunning Peasant was premiered in January 1878, the events of the previous two years were not easily erased from people's memories.

Dvořák's decision to offer The Cunning Peasant to the Provisional Theatre administration in summer 1877 was timely, since it was a work that the increasingly prominent Young Czechs were likely to approve. Vanda had been pan-Slavic, both in its music and in its dramatic content, based on an ancient Polish legend. Of the two political parties, the Old Czechs were the ones who tended to be proponents of pan-Slavism, and such an opera would undoubtedly have appealed to their tastes.Footnote 55 In contrast, The Cunning Peasant draws upon material that is definitively Czech, and the work alludes to the comic operas by the hero of the Young Czech Party, Smetana. Having already found favour with the Old Czechs, then, Dvořák seemed to be striving with this opera to win over the Young Czech faction of the Provisional Theatre audience and the many Party supporters who stood at the theatre's helm in the late 1870s.

Czech critics did not state it directly in 1878 in the way that Hanslick would in 1885, but their reviews affirm that Dvořák's opera was indeed ‘written for the Prague Czech public’.Footnote 56 Emanuel Chvalá (1851–1924) characterised the work as Dvořák's concession to a specifically Czech audience.Footnote 57 By offering The Cunning Peasant for performance at the Provisional Theatre, Dvořák demonstrated an awareness of the idiosyncrasies of the venue and its audiences. According to critics, those in attendance at the premiere responded to the opera's tunefulness and easy accessibility. Seeking to provide an explanation for the work's popularity, Pivoda writes in summary that ‘the reason for its success is the non-foreign, folk national direction that it takes’,Footnote 58 and that ‘national direction’ was manifested in various distinct ways.

‘Cunning’ Dvořák: conforming to Czech comic opera conventions

As observed by its early critics, The Cunning Peasant is a thoroughly conventional Czech comic opera, which incorporates into its plot comedic gestures that had almost become clichés. For instance, at its climax in the second act, one of the characters falls victim to a prank. With Václav as his accomplice, Martin – the cunning peasant at the centre of the story – sets a trap for his daughter Bětuška's suitor, Jeník, removing the ladder from beneath Bětuška's window and replacing it with a barrel into which Jeník is supposed to plummet. The prank misfires, when an entirely different character – the valet Jean – falls into it instead. This type of slapstick humour was common at the Provisional Theatre, where audiences frequently witnessed characters plunging accidentally into barrels, boxes, wells and water ducts.Footnote 59 The gimmick can be traced back to Vilém Blodek's comic opera from 1867, In the Well (V studni):Footnote 60 in an attempt to court a peasant girl, the wealthy suitor, Janek, falls into a well at the opera's conclusion. A similar comic effect can be found in Vojtěch Hřímalý's 1872 opera The Enchanted Prince (Zakletý princ), where one of the characters slips into a water fountain. These operas were well known to Czech audiences, having become staples in the Provisional Theatre repertory by the late 1870s, and allusions to them in The Cunning Peasant would have been instantly recognisable.

Dvořák's opera also conforms to established traditions by being set in the Bohemian countryside: a rural setting had become an indispensable ingredient for a successful Czech comic opera, ever since The Bartered Bride (Prodaná nevěsta) had enjoyed immense popularity in the early 1870s. When soliciting entries for an opera competition to mark the opening of the Provisional Theatre in 1862, Count Jan Harrach had suggested that Czech comic operas be based on village life.Footnote 61 While urban audiences found these rustic milieus to be somewhat off-putting at first,Footnote 62 such subjects quickly became a mainstay of Czech theatre. By the 1870s, rural locales were a safe choice for comic operas not only because they were sure to please, but also because they could be easily staged. The same sets and costumes were used repeatedly at the Provisional Theatre, which certainly helped give audiences the impression that these works were part of a unified repertory.Footnote 63 For The Cunning Peasant, librettist Josef Otakar Veselý (1853–79) indicates that the story is to take place in the town of Domažlice, rather than leaving the name of the village unspecified, as was usual practice. As a result, new costumes were ordered for the opera's premiere, designed to reflect the dress that was native to the Domažlice region. This emphasis on regional authenticity ties in with the broader European staging practice of using historically ‘accurate’ sets and costumes in opera productions. Christopher Campo-Bowen has also pointed to the ‘emphasis on ethnographic and geographic veracity’, and noted that the trend began in 1820s Paris.Footnote 64 This authenticity simultaneously distinguishes The Cunning Peasant from other contemporary Czech works of its kind. Many of the critics comment on the costumes as a particular selling point of the work, especially in articles that were published in the weeks leading up to the premiere. For example, one critic writes with palpable excitement: ‘The production will be rich and a large portion of the costumes, particularly the national dress of Domažlice, will be completely new.’Footnote 65 In its idealised rural depiction, Dvořák's work not only adhered to a common Czech opera trope, but also ‘perform[ed] the village’, and in so doing invited wider acceptance of Czech music.Footnote 66

The plot itself also relied on a well-worn premise. Much like The Bartered Bride, The Cunning Peasant tells the story of a young woman being forced against her will into an arranged marriage and simultaneously deterred from marrying her true love. The notion of two suitors vying for the same peasant girl – one of her father's choosing and one of her own – would undoubtedly have brought Smetana's best-known opera to mind for most audience members. Even the names of some of the characters from The Bartered Bride are retained in The Cunning Peasant. In each of the two works, the female protagonist's true love – the peasant boy, whom she ends up marrying – is called Jeník, though in The Bartered Bride he is much more pro-active than in The Cunning Peasant.Footnote 67 Tenor Antonín Vávra (1847–1932) performed both roles in Prague during the 1870s, sealing the connection between these two characters.Footnote 68 The other suitor in The Cunning Peasant is Václav, whose name is a formal version of Vašek, his counterpart in The Bartered Bride. Though less ridiculous, Václav is similar to Vašek: both are the sons of wealthy landowners and considered to be the most suitable prospective husbands for the female protagonists.Footnote 69 Additional parallel characters between the two operas have different names. Martin, the title character of The Cunning Peasant and the heroine's father, can be likened to Kecal, the marriage broker in The Bartered Bride: classic buffo characters, these men concern themselves with bringing about financially lucrative marriages. Like Mařenka in Karel Sabina's libretto, Bětuška plays the role of the pious and morally upright peasant girl in Veselý's text. In their broad strokes, then, the operas tell the same basic story;Footnote 70 yet, their titles indicate different points of emphasis. The Bartered Bride revolves mostly around the arranged marriage, while the central event in The Cunning Peasant is the aforementioned trick that Martin devises in order to thwart Jeník's courtship of Bětuška.Footnote 71

Given the similarities between the works and familiarity with The Bartered Bride, comparisons with Smetana's opera were inevitable in reviews of The Cunning Peasant following its Prague premiere.Footnote 72 Hostinský links these two operas, citing the duet between Jeník and Bětuška in the second act of Dvořák's work as evidence:

It was pitiable when, just a year ago, Smetana complained that his Bartered Bride had won the approval of so many of our audiences but not our composers; now he has true confirmation; a very talented representative of the younger generation of composers [Dvořák] barely set foot on Smetana's path of comic opera [composition] and was able to achieve such a success. And those parts [of The Cunning Peasant] that are most similar to The Bartered Bride were the best liked (for instance, the duet between Jeník and Bětuška in the second act) and show best that Dvořák did not give up his own artistic personality and individuality. This example of Dvořák's will not remain without a following, Lord willing; for it is only by this path – along which a talented artistic group heads in an excellent direction, determined by an individual [Smetana] – that an artistic school can be created.Footnote 73

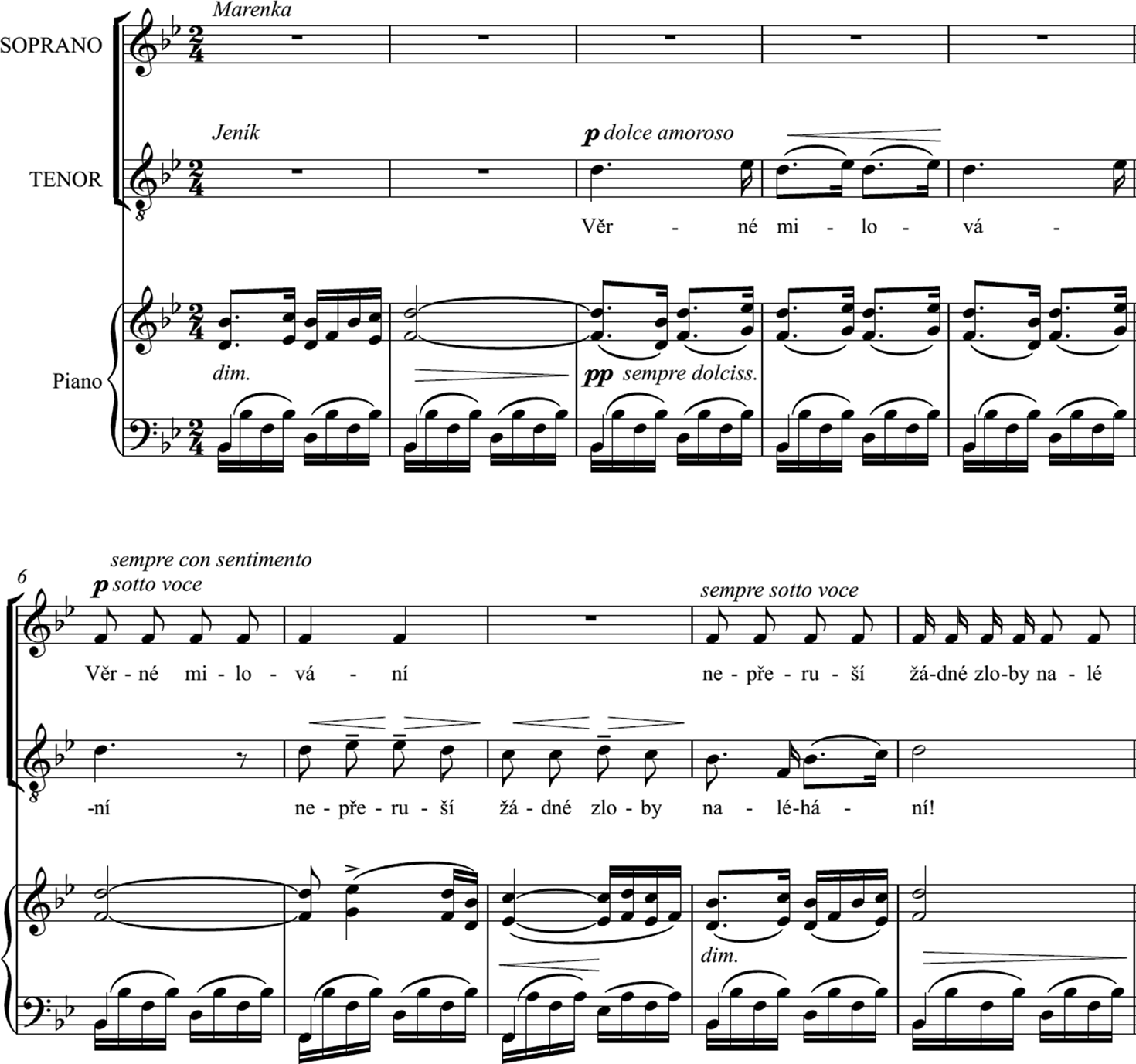

Smetana's librettist for The Kiss – Eliška Krásnohorská (1847–1926), who attended the premiere of The Cunning Peasant – refers to the same example as Hostinský in a letter dated 28 February 1878. Addressing Smetana, Krásnohorská states emphatically: ‘[Dvořák] has borrowed from your Act I duet in The Bartered Bride. Other parts are almost copies!’Footnote 74 Though occurring at different moments in their respective plots, ‘Rozlučme se dráha’ from The Cunning Peasant (Example 2) and ‘Věrné milování’ from The Bartered Bride (Example 3) are both lyrical duets in which the lovers pledge devotion to one another.Footnote 75 Each duet begins with a tenor solo in the high register; the soprano soon joins in with recitation-style interjections on the fifth scale degree. Krásnohorská further claims that the dramatic progression of the first few scenes leaves listeners with little doubt as to its model. ‘His libretto is very similar to … Act I of The Bartered Bride’, she observes: ‘first a gay chorus, then a lament by a girl, then a duet for the girl with her lover, then an intervention by the father and the suggestion of a rich bridegroom, and so on’.Footnote 76 While Hostinský and Krásnohorská allude to specific moments in Dvořák's opera that remind them of The Bartered Bride, most critics confine their remarks to generalities. One reviewer from 1878 writes simply that Dvořák attains ‘a loveliness [in The Cunning Peasant] that was formerly seen only in Smetana's The Bartered Bride’;Footnote 77 another critic, reviewing the work after an 1883 performance, describes The Cunning Peasant as belonging to a Czech operatic trilogy, along with The Bartered Bride and Hřímalý's The Enchanted Prince.Footnote 78 Comments like these suggest that the critics sought to situate Dvořák's work at the centre of a Czech comic opera repertory.

Example 2. Duet ‘Rozlučme se, drahá’ from Dvořák's The Cunning Peasant, Act II scene 2.

Example 3. Duet ‘Věrné milování’ from Smetana's The Bartered Bride, Act I scene 2.

Yet more than The Bartered Bride, it is Smetana's The Kiss that is mentioned in reviews of Dvořák's opera. The Kiss was premiered at the Provisional Theatre in late 1876, and Dvořák had allegedly attended the performance, witnessing its success first-hand.Footnote 79 The event was undoubtedly still fresh in people's minds in early 1878, and this is reflected in assessments of The Cunning Peasant. Writing in Národní listy, Hostinský predicts that Dvořák's work will ‘become a favourite of audiences in the same way as Smetana's The Kiss, of which it is a blood-related sister’.Footnote 80 The critic for Světozor goes further:

The Kiss was an appropriate model for [Dvořák], but not a model that he wanted to imitate; rather one to which he created a compelling counter response (protiobraz) based on his own imagination; and even if the composer Dvořák did not achieve in this work the kind of harmony of all parts, those characteristics, purity and stability of the national style, which we rightly admire in the music of Smetana, he can still look at his opera with great satisfaction – a work with which he has gained a second spot among our dramatic composers.Footnote 81

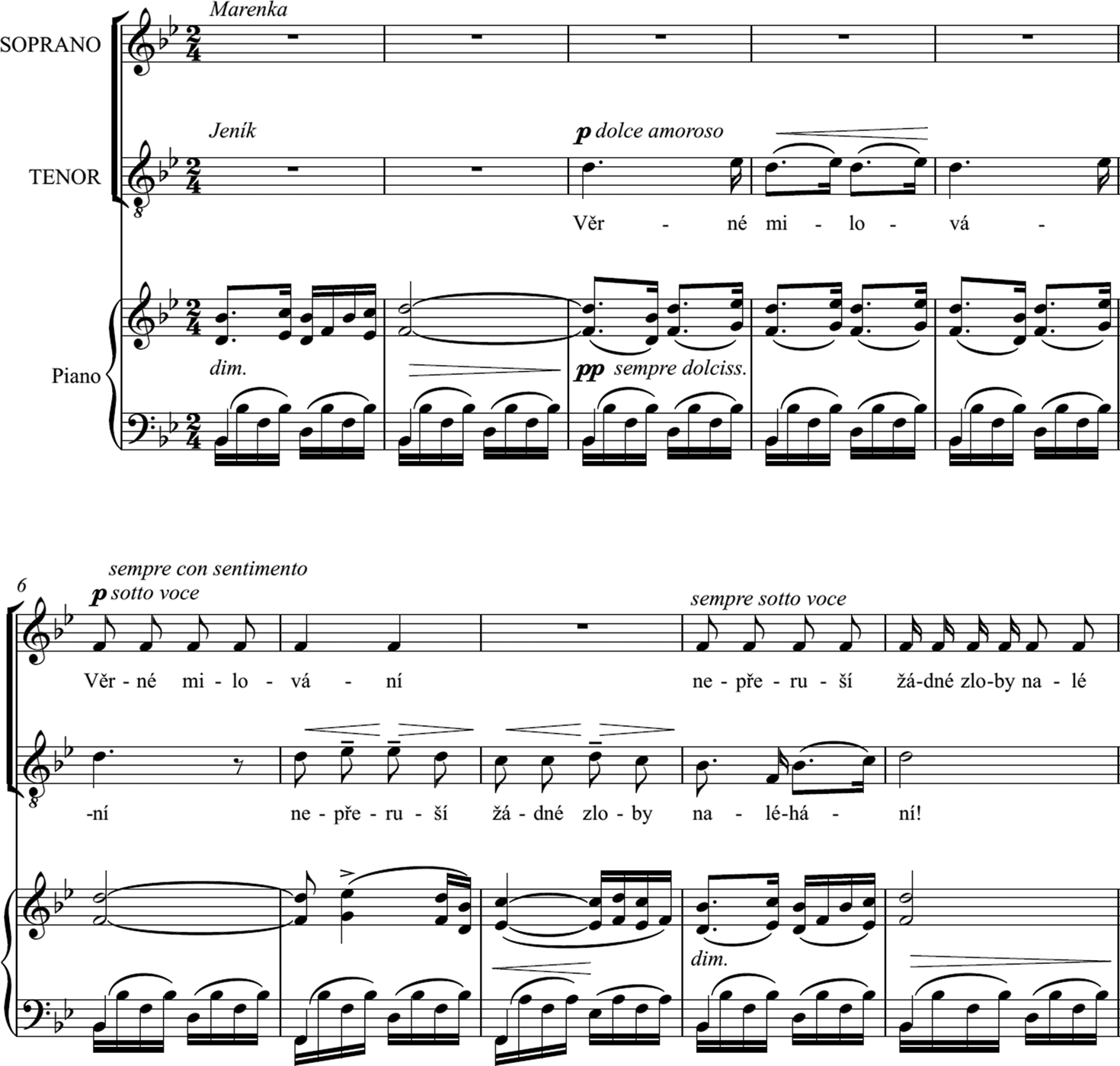

A more extensive analysis of the opera's relationship to Smetana's The Kiss is provided in Pokrok. In the first of two articles on The Cunning Peasant, the reviewer writes as follows: ‘We do not consider some reminiscences [of Smetana's The Kiss], which have more to do with details of construction (podrobnosti faktury) than melodic motives, to be [Dvořák's] fault; they are completely natural, can scarcely be avoided, and apart from these, Dvořák's imagination and thoughtfulness is evident on every page of the score.’Footnote 82 The critic's comments in the second article are in a similar vein: ‘we have already hinted that the influence of Smetana's The Kiss on the composer is discernible in this work; nevertheless, we do not agree with those who see Dvořák as a talented and fortunate imitator’.Footnote 83 Reiterating his earlier point, the critic assures readers that Dvořák ‘does not imitate, but imbibes the spirit of Smetana's music, creating independently’.Footnote 84 As evidence for this assertion, the reviewer calls attention to the peasant Martin's ‘Dobrá jdi si tedy k němu’, from Act I scene 3 of The Cunning Peasant (Example 4) and Father Paloucký's ‘Jak jsem to řek’, from Act I scene 6 of The Kiss (Example 5) – arias which, in the critic's view, might be considered complementary.Footnote 85 Though they are set in different keys, both are cast in 2/4 time, with a prominent underlying triplet rhythm. The arias begin with a series of downward leaps and proceed in a quick patter style of vocal composition that alludes to the buffa tradition. Perhaps the most conspicuous similarity comes at the end of the two numbers: each concludes with lengthy melismas, which contrast with the otherwise largely syllabic text-setting of the arias.

Example 4. Martin's aria ‘Dobrá jdi si tedy k němu’ from Dvořák's The Cunning Peasant, Act I scene 3.

Example 5. Father Paloucký's aria ‘Jak jsem to řek’ from Smetana's The Kiss, Act I scene 6.

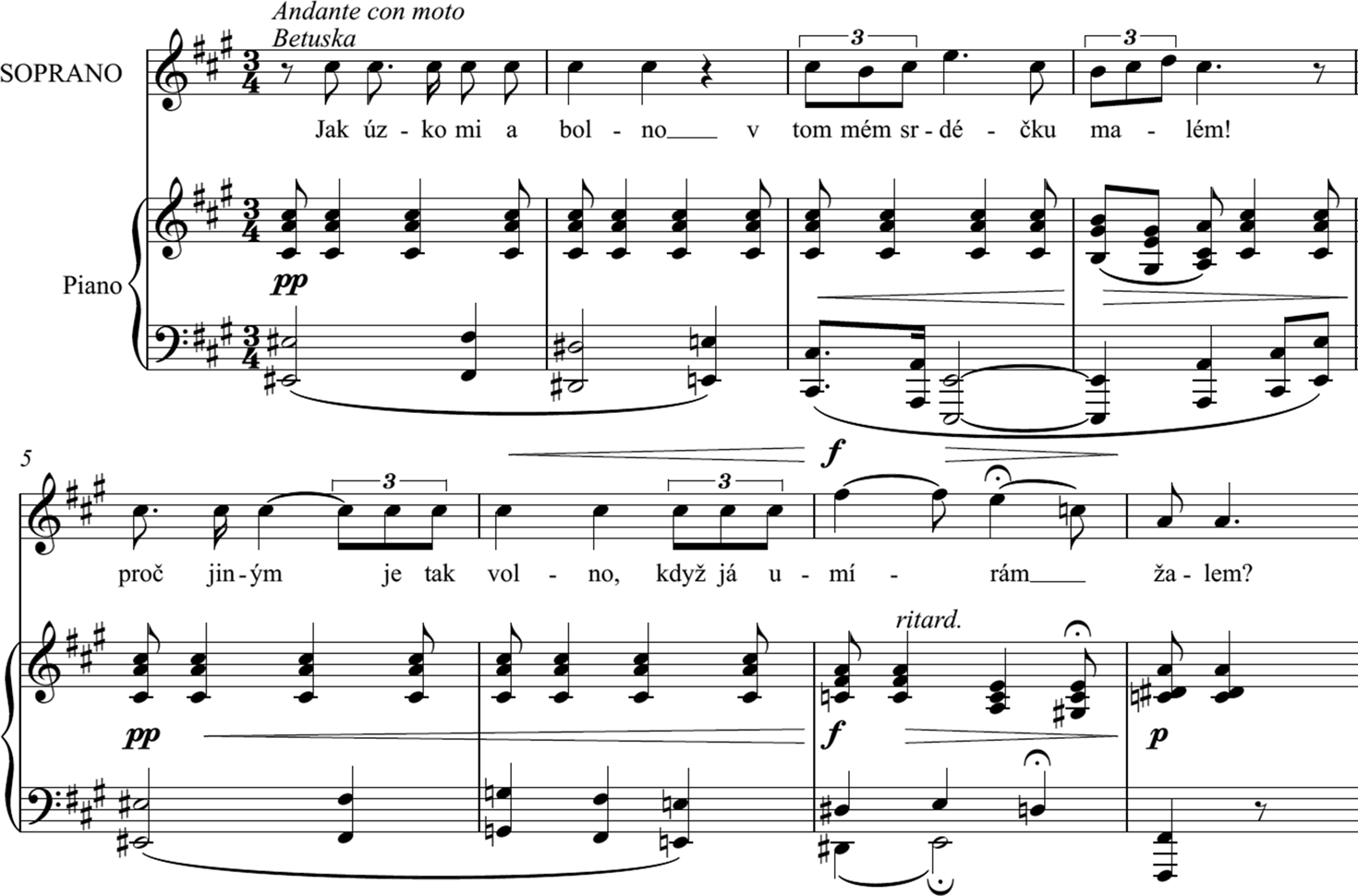

For all the critics’ efforts to show that Dvořák's work is aligned with Smetana, none refers to the aria ‘Jak úzko mi a bolno’, which appears at the end of Act I of The Cunning Peasant (Example 6). Here, the reference to Smetana is unmistakable. Bětuška sings of her anxiety over her impending arranged marriage to Václav and asks God to intercede, so that she might marry her beloved Jeník instead. This aria bears a strong resemblance to heroine Vendulka's ‘Jak zapomněl by na ten krásný čas’, from Act I scene 7 of Smetana's The Kiss (Example 7). Like Bětuška's aria, Vendulka's comes at a moment of uncertainty in the opera, as she contemplates her former love for Lukáš and conveys her trepidation for the future. A textual similarity seals the connection, as the arias begin with the word ‘jak’ (how). Both arias are marked ‘Andante’, written in 3/4 time, and scored in A major. Above the opening F♯ minor chord with an E♯ appoggiatura in the bass, the voice sings a relentless C♯, in a kind of recitation style that is moulded to the sorrowful text.Footnote 86 Such an overt nod to Smetana is rare in Dvořák's œuvre. In short, when composing The Cunning Peasant, Dvořák showed himself to be well versed in the Czech repertory, and this was seen as a positive quality among Czechs. Rather than viewing Dvořák's adherence to well-established operatic norms as a weakness, Czech critics of the 1870s delighted in it and described The Cunning Peasant as the composer's first step on a path that had been laid out by his operatic predecessors.

Example 6. Bětuška's aria ‘Jak úzko mi a bolno’ from Dvořák's The Cunning Peasant, Act I scene 14.

Example 7. Vendulka's aria ‘Jak zapomněl by na tak krásný čas’ from Smetana's The Kiss, Act I scene 7.

Several critics suggest in their reviews that the title of Dvořák's opera is inappropriate, arguing that the peasant Martin's actions are not terribly ‘cunning’. Of all the conventional gestures that were embedded in Veselý's libretto, Martin's prank was considered to be the most clichéd – labelled by Pivoda as an ‘over-used gag’.Footnote 87 Hanslick writes: ‘Both of the ingenious inventors, Martin and [Václav], want to laugh themselves to death at the joke of putting an empty barrel under the climbing lover; but the ones who do not laugh are the audience members, at least those at our [Vienna] Court Opera. The whole intrigue is aimed at an astonishingly naïve public.’Footnote 88 Even Hostinský – though he does not frame it in the same condescending terms as Hanslick – remains unamused by Martin's jokes:

The whole ‘cunningness’ of the peasant Martin – who says of himself that he is a ‘calculating bird’ and that ‘jokes come from every fibre of [his] being’ – lies in the fact that instead of a ladder, on which the poor farmer Jeník comes to visit Martin's daughter Bětuška, he places a barrel with a splintered plank beneath the window of her chamber … we [might] add that even this one and only ‘clever trick’ does not work out for Martin, because his victim turns out to be someone else.Footnote 89

In view of Martin's failed attempts at craftiness, it might be argued that the ‘cunningness’ of the opera as a whole lies in another direction – that is, in its appeal to Provisional Theatre audiences. Dvořák had secured a place for himself on the Czech operatic stage by tailoring the opera to his Czech public. Aware of Dvořák's own small-town roots, critics perhaps believed that he was better qualified than other composers to access the idealised rurality that they so craved in the comic opera genre. Jarmil Burghauser has observed that Dvořák's characterisation as a ‘peasant among composers’ that arose in the 1880s was surely encouraged by the composer himself as it helped to distinguish him from the fashionable philosophical or literary constructions of his contemporaries at the fin de siècle.Footnote 90 The real title character of the piece, then – the true ‘cunning peasant’ – might be Dvořák himself.

‘Impossible for the foreign stage’? Analysing the Viennese scandal in the Prague press

More than Dvořák's other operas, The Cunning Peasant is bound to a particular time and place. Unlike Vanda and Dimitrij, both of which are based on pan-Slavic material, and Rusalka Footnote 91 and Armida, which have more universal plots, The Cunning Peasant strives to be unequivocally Czech.Footnote 92 Since Czech operas were unknown in Vienna, audiences could not appreciate The Cunning Peasant's many connections to the Provisional Theatre's existing repertory; nor could they place the opera in a broader Czech context. The writer for Národní listy accounts for the opera's riotous Viennese reception by pointing to its Czechness, which to him makes it inappropriate for foreign performance. He also laments the fact that Dvořák's opera Dimitrij had not been chosen instead, asserting that this more recent work would have had a better chance of faring well on the international stage:

If Dimitrij had been given, it definitely would have been well liked; it would have surprised given the immense poverty of opera production [in Vienna], and from Vienna it would have made its way to all European stages, pushing Dvořák to the first rank of operatic composers. This had to be prevented and for that reason the relatively weak and purely Czech comic opera The Cunning Peasant was chosen. Its unfortunate text, which is impossible for the foreign stage, kills at least half of the effect of the lovely music. Dvořák's friends, who know the conditions here, warned Dvořák long ago and intently not to allow this particular opera to be performed first. Dvořák allowed [this to happen] after all and now he must see that his opera is being treated as a failure.Footnote 93

The critic for the journal Lyra sees the situation in much the same way and questions Dvořák's judgement not only in allowing this opera to be performed, but also in agreeing to have the libretto twisted out of shape.Footnote 94

Efforts had been made to downplay the Czech elements in Dvořák's opera. The German translation of the text – prepared by Emanuel Züngel for productions in Dresden and Hamburg during the early 1880sFootnote 95 – was considered inadequate for Vienna and had to be revised extensively so that it might please the more demanding Viennese public.Footnote 96 The plot was also transferred from its original setting of Domažlice to ‘Upper Austria’ – an alteration that had been initiated by publisher Fritz Simrock in 1882 for the opera's printed score and had already been in place for the Dresden and Hamburg performances of the opera. This change in location was likely done out of sensitivity to these German-speaking audiences. Located in Western Bohemia, the town of Domažlice had certain anti-German associations, since it had been the site at which Czech armies joined together to drive Germans out of Bohemia during the Hussite Wars of the fifteenth century, in what is referred to as the Hussenflucht.Footnote 97 Presumably, it was thought that such changes were required for it to be successful in the German-speaking world. However, its effect was somewhat miscalculated. In his review, Hanslick is bothered by the discrepancy between the ‘Slavic’ music and the ‘Upper Austrian’ setting, and he decries attempts to purge the opera of its Czechness. His comments on this are worth quoting in full:

More noteworthy, even baffling, is the statement in the Berlin libretto: ‘the plot takes place in Upper Austria’. From where did this nonsense come? The character of the music is distinctly Slavic; everyone can hear that after a fleeting listen to the first number; indeed one has to say this even after hearing the overture: the work is set in Bohemia and is played by Bohemian peasants. A composer, who wanted to characterise these melodies as Upper Austrian, belongs in the observation room of a mental hospital. Dvořák naturally had no part in this; in his original, the characters, who in translation are called Regina, Conrad, Gottlieb, have typical Czech names: Bětuška, Jeník, Václav. These original names should have been retained;Footnote 98 The Cunning Peasant is first and foremost a national-Bohemian opera, a work of Bohemian country life and as one cannot disturb this character in Dvořák's music, so one should not look to deny it or to transplant it to a different country. Which German translator of the opera Carmen would write in the libretto: the plot takes place in Steiermark, just to make it more popular here? … One must give distinctly national works with all their peculiarities or not at all.Footnote 99

Echoing Hanslick, Edvard Moučka – the Viennese correspondent for the Prague journal Dalibor Footnote 100 – objects to the idea of removing some of these Czech elements, pointing not just to the neutrality of the sets, but also to the costumes.Footnote 101 Moučka alleges that the costumes used in Vienna were deliberately nondescript. In his view, when the nationality of a work is ambiguous, it becomes bland, and the characters turn into mere caricatures, lacking any depth. In Moučka's words:

the national character of the whole work, which also contributes to making it interesting, was carefully taken out of the plot of the opera, even if it could not be taken out of the original music. In the piano-vocal score published by Simrock, Upper Austria is specified as the setting; here in Vienna, no location was given on the programmes and the costumes were completely international. The result of it was that all of the characters became mere puppets, who played their parts in a stereotyped, almost irritatingly caricatured, manner.Footnote 102

Moučka also marvels at the ignorance of the reviewer for the Morgenpost, who surmises that the Upper Austrian setting had been designated by Veselý in the initial version of the libretto, rather than being a revision intended to make the work more palatable to Viennese audiences. As Moučka explains, ‘the reviewer for the journal Morgenpost even dared to make the following reflection: “If Mr. Wesely” – the reviewer consistently avoids the orthography “Veselý” – “sets the story in Lower Austria and Dvořák sets the music in the Czech lands, the director ought to have taken his cues from the composer because it is easier to change the costumes than the music.”’Footnote 103 Conceived as a gesture that might make the work more relatable to Germans, the opera's changed setting and neutral costumes offended the very audiences that they were supposed to please. To the Viennese, far worse than a Czech peasant singing Slavic melodies on the Hofoper stage was one who did so while claiming to be Upper Austrian. This issue was not particular to Vienna and had already been raised when the opera was performed in Hamburg in 1883. In his study on Dvořák's reception in German-speaking Europe, Klaus Döge suggests that the mismatch between the setting of the story and the character of the music was the main element that prevented the opera from securing a permanent spot in the Hamburg Staatsoper repertory.Footnote 104 A Czech opera would not be performed in Vienna again until 1892, when Smetana's The Bartered Bride was given, among other works, by members of the Prague National Theatre, as part of the International Exhibition of Theatre and Music. The Bartered Bride was performed several times, and the other works given were Smetana's Dalibor and Dvořák's Dimitrij. In preparation for the Smetana production, Dr Josef Herold, a delegate from the Imperial Reichsrat, emphasised to the members of the National Theatre Association that ‘it was necessary to preserve a Czech character for the Viennese performances’ in all aspects. Apparently, they were heeding the lessons from seven years earlier. The Bartered Bride would be favourably received in the Austrian capital, and the fact that its ‘Czech’ character was not diluted likely contributed to its success.Footnote 105

Not only was The Cunning Peasant too Czech for Vienna and yet bland when its Czech elements were removed, but critics writing in Prague in 1885 considered it insufficiently representative of Czech achievement in the genre. To some extent, these kinds of opinions had already been expressed at the time of The Cunning Peasant's 1878 Prague premiere. By the late 1870s, the popularity of The Bartered Bride had grown to such proportions that it proved a stumbling block for the Czech reception of even Smetana's later operas, let alone the operas of other composers.Footnote 106 In such a climate, the best that Dvořák could hope for, when aligning himself with a distinctly ‘Smetana’ brand of comic opera, was second place in the eyes of the Czechs. In fact, this may have been what motivated him to turn away from the Smetana model altogether in the early 1880s and find his own voice in the realm of opera. According to Kelly St Pierre, the 1880s marked a shift: whereas critics in the past had devoted ‘attention to questions of whether or how Smetana wrote “Czech” music’, Smetana's output was now being pitched as ‘an ideal model for contemporary composers’,Footnote 107 and after Smetana's death in 1884, the tone of much of this writing became increasingly hagiographic. By the early twentieth century, a group of Czech critics would go so far as to use Smetana's style as a yard-stick of ‘Czechness’ and label works that did not measure up, as overly foreign.Footnote 108 Even though critical perceptions of Czech nationalism were still broad enough during the 1870s and 1880s to encompass the music of more composers than just Smetana,Footnote 109 there was already a sense among critics that any efforts to draw international attention to Czech works in this genre ought to be done through Smetana.

Critics in Prague were, thus, surprised that the task of paving the way for Czech opera composers in Vienna had been entrusted to Dvořák, with his Cunning Peasant as the vehicle. It was probably Dvořák's international renown that endeared him to the Vienna Hofoper administration: by 1885, he had achieved success beyond Bohemian borders in essentially all genres other than opera. Furthermore, as early as 1879, his grand opera Vanda had been under consideration for performance in Vienna, though – after extensive negotiations – the idea of staging it was eventually abandoned.Footnote 110 For better or worse, it was Dvořák who brought Czech opera to Vienna officially, and the larger significance of this was not lost on Czech critics. In the days leading up to the performance, an article appeared in Dalibor suggesting that the stakes were high and that the outcome of the event would have far-reaching repercussions. The critic predicts that ‘if this novelty breaks through with the rigorous audience of the Viennese opera, Dimitrij will not be far off on the horizon and maybe Dvořák will pave the way for other Czech composers to the stage that is supported by the state – a stage that has so far been closed off to them’.Footnote 111 Initial reports of the event in Prague are actually quite optimistic, and journalists seem to be reluctant to characterise it as a complete failure right away. The writer for Národní politika claims that the performance went off better than had been expected after the dress rehearsal and that the work ‘was received by the large audience, which filled all areas of the theatre, with frequent loud praise’.Footnote 112 Relatively positive reports also appear in Národní listy:

According to news from Vienna, Dvořák's The Cunning Peasant had honourable success there, though we would not be the least bit surprised if the work of our fellow countryman, be it filled with extraordinary musical beauty, were refused under the present circumstances by the angered Viennese, who have long stopped being the friendly do-gooders that they allegedly once were.Footnote 113

Yet hope quickly turned to disappointment when the opera fared so badly. The journalist for Národní listy highlights the severity of this failure, by asking the reader:

[After such a performance] who would want to prove, in the hope of a [positive] outcome, that The Cunning Peasant is not Dvořák's best opera – that he himself wrote the excellent grand opera Dimitrij on a good text by the spirited Mrs. Červinková? Who would want to convince the Germans that The Bartered Bride, The Kiss and Two Widows are valued much more in the Czech lands than The Cunning Peasant? [Who would want to explain to them] that, apart from Dvořák, we also have Smetana, Bendl, Rozkošný, Hřímalý, Bloček, Fibich, etc. and that these [composers] have [written] operas that will certainly achieve success on the large stage and will be more understood and well-liked than The Cunning Peasant?Footnote 114

Clearly, Dvořák was supposed to act as a kind of trailblazer, following whom the likes of Smetana, Bendl and others could make their way to the Viennese operatic stage. After The Cunning Peasant's scandalous reception, Vienna was perhaps more closed off to these other composers than ever. Aside from Czech participation at the International Exhibition in 1892, there was to be no performance of Smetana's operas in Vienna until nearly a decade later: The Kiss was staged at the Hofoper in 1894, and The Secret (Tajemství) followed in 1895. The Bartered Bride and Dalibor were given shortly thereafter, during the 1896/97 season. Although the Viennese premieres of the latter two operas witnessed no riotous behaviour, the press headlines for Smetana were, in some respects, much the same as they had been for Dvořák back in 1885. While some Viennese critics considered the performance of Smetana's operas in Vienna to be shamefully overdue, others used their reviews as an opportunity to uphold the operas of German composers and urge the Viennese to be weary of the ‘inundation of [their] musical life with Slavic works’.Footnote 115

In the wake of The Cunning Peasant controversy, several critics alleged that the whole incident had been orchestrated by members of the Vienna Hofoper administration to portray Czech opera in the worst possible light. They argued that a weak opera was chosen on purpose so that it might give Viennese critics an excuse to unleash invective on Czech art.Footnote 116 The implication is that a stronger work – in the Czech critics’ estimation – would have been able to safeguard itself against the prejudice of a Viennese crowd. Moučka takes this notion of a conspiracy the furthest, claiming that the administration had Dvořák's opera Dimitrij in its possession and could well have mounted it, instead of The Cunning Peasant.Footnote 117 Although Moučka's own biases as a Czech in Vienna undoubtedly influenced his assessment, his ideas are not completely unfounded. Hanslick is known to have liked Dvořák's Dimitrij: he had travelled to Prague in 1882 for the express purpose of attending the opera's premiere. Access to performance materials might have been gained easily through him. Václav Vladimír Zelený, writing for Dalibor in 1882 – three years before the Viennese scandal – predicts that The Cunning Peasant will not fare well in the Habsburg capital:

It is important to give recognition to Professor Hanslick, who is constantly drawing attention to the excellent operas of Dvořák. … I do not doubt that Dvořák, in any event, would soon be able to pave a path to foreign stages, but the efforts of Hanslick, more privately than through the press, have a great deal to do with it. … The theatre audience [in Vienna] is much wider and on average much less acquainted with music than the concert audience; on the other hand, [the theatre audience] is much more entangled in national and political prejudice, and for this reason, it would certainly be best to disarm them with such an imposing work as Dimitrij (according to all reports), and then show the comic operas. For this it does not follow that it is necessary to be afraid of the success of The Cunning Peasant, if it is indeed the first Dvořák opera to be performed in Vienna. For even if the weak parts of the libretto would cause negative assessments to predominate at first – [the weak parts being] exaggerated in the eyes of the Viennese by their Czech origins, which [would] probably make them the target of their rude jokes – these [opinions] would have to change in time. This is partly because of the high value of Dvořák's music and partly because the Germans are grossly lacking in comic operas of the type that are overflowing with musical thought, like The Cunning Peasant or Stubborn Lovers. Only this much is certain: the path of Dimitrij would be shorter and more successful.Footnote 118

Curiously, no mention is made here of the possibility of staging a Smetana opera in Vienna, in spite of Zelený's developing reputation as a Smetana partisan:Footnote 119 he confines his remarks in this instance to the operatic output of Dvořák. Though Zelený is more optimistic than those who would write in 1885, he already suspects The Cunning Peasant will be the ‘target of … rude jokes’ in the Austrian capital. The author of another article, printed in Dalibor in 1882, also suspects that The Cunning Peasant will be received poorly in Vienna:

[There] is talk, quite seriously, among the Czechs who are close to the world of opera, of the possibility of a performance of a Czech work by the present opera company, for which the name Dvořák, better known here, is at the forefront. Professor Hanslick earnestly asked the opera commission to prepare The Cunning Peasant, although I think that a serious opera would be more appropriate, whether it be Vanda or Dimitrij, unless a good revision of The Cunning Peasant would be done successfully.Footnote 120

The scandal was, in many ways, foreseeable even to the Czechs, leading some critics to conclude that it had been purposely arranged.

Moučka claims that the conspiracy extended to aspects of the performance. In his view, an inferior conductor and poor singers were selected for the production, so that the opera could not be heard at its best:

Instead of entrusting the singing roles to the best voices, of which there are many in the institution, the two most important roles (the Duke and Martin) were given to Mr. Horowitz and Mr. Mayerhofer, who are talented actors, but singers with very small voices. They were not able to do much as singers, and the parts themselves did not allow them to do much as actors. The direction of the opera should have been entrusted to the conductor with the greatest musical sensitivity, preferably to director Jahn, who is always able to compensate for a lack of effective contrast through the soft shading of individual phrases. Instead, the opera was given to conductor Hellmesberger Jr., who treats everything as if it were ballet music.Footnote 121

Though Moučka does not consider The Cunning Peasant to be without its weaknesses, he writes that ‘a keen and well-intentioned performance would have been capable of hiding some of the flaws and presenting the strong points of the work’.Footnote 122 Whether or not there is any truth to Moučka's assertion, multiple sources – both Czech and Viennese – report that the musicians did struggle to take the work seriously when performing for an empty theatre during the opera's second night. In his final analysis, Moučka divides members of the Hofoper audience into three distinct camps: those who liked the opera and had ‘retained the ability to make healthy aesthetic judgments about true beauty’; the blind fanatics, railing ‘against all things Czech’; and those who were jealous ‘over the fact that Vienna is fading more and more into the background in comparison to artistic production in Prague’.Footnote 123 Though in this last remark Moučka may be getting carried away with his own nationalist sensibilities, his comments do suggest that audience members were not as unanimous in their reactions to The Cunning Peasant as some Viennese critics would have their readers believe. In passing, Moučka likens the whole affair to one of the most infamous riots in operatic history: the Paris premiere of Wagner's Tannhäuser in 1861, when members of the Jockey Club whistled and shouted throughout the performance in protest against the Princess Pauline Metternich.Footnote 124

* * *

The politically charged atmosphere in Vienna during the 1880s prompted many audience members to head to the Hofoper production of The Cunning Peasant with their minds made up about what they were going to hear. The writer for Národní listy acknowledges this, writing that ‘Czech artists do not have to feel sorry when their creations do not come before the Viennese audience during these irritable times. [The Viennese audience] persistently refuses to give recognition to a work, no matter how splendid it might be, and to an artist, no matter how world-renowned, when he is a Czech.’Footnote 125 The writer for Národní politika reaches the conclusion that Czech composers do not need Viennese approval in order to know their worth; as he puts it, ‘for us, the opinion of an irritated mob is not what determines [the success of this work], though the [rioters] seem to have caught the attention of [the newspapers]’.Footnote 126 Favourable reviews from German-speaking Europe had caused The Cunning Peasant to grow in the Czech critics’ estimation,Footnote 127 but denunciation from Vienna was not about to bring the opera down in their eyes. Even so, Czech critics were persuaded, and perhaps harboured the delusion, that the outcome at the Hofoper would have been better with a different opera – one that was less blatantly Czech and held in higher regard in Czech musical circles than Dvořák's The Cunning Peasant. Hostinský, known to have disapproved of Dimitrij, was probably the only Czech critic who would not have supported a performance of Dvořák's later opera. Hostinský spends a large portion of his article on Dvořák's operas from 1901 dismissing Dimitrij, not only because it is in the grand opéra tradition, which, to Hostinský, meant that it was regressive, but most especially because Hanslick approved of it; throughout the article, Hostinský communicates a sense of unease over the hold that Hanslick seemed to have on Czech audiences in general and Dvořák in particular.Footnote 128 Yet, even he writes in 1878 that: ‘The best libretto for Dvořák would be a serious one, with true poetry, perhaps even pathos, in which lyrical moments might give way to large ensembles (let us remember Dvořák's Hymnus from Hálek's Heirs of the White Mountain) – such a text would guarantee an even more beautiful success than can be detected in The Cunning Peasant.’Footnote 129 Coming from a Czech vantage point, these critics were familiar with the many operatic works that had appeared on the stages of the Provisional and National Theatres in Prague and were bothered by what they deemed to be a case of misrepresentation. Although these critiques do not cast The Cunning Peasant in the most positive light, the immediate reaction that the Viennese episode seemed to inspire in the Czechs was sympathy. Jarmil Burghauser touches on this idea, when he claims that, after what happened in Vienna, Czech audiences became more interested in The Cunning Peasant – though this interest proved to be short-lived.Footnote 130 Dvořák's opera was given a brief run at the National Theatre in Prague in late 1885 and three performances in Brno in 1886, before being set aside once again. Though this upsurge in interest did not translate into a considerable increase in performances at home for the long term, the incident did force Czechs to revisit a work that had by then started to become somewhat neglected in the Czech lands and re-evaluate its place in the Czech opera repertory. Many years later, in an obituary for Dvořák, one critic observes: ‘From among Dvořák's operas, Dimitrij is generally held in the highest regard; however, The Cunning Peasant is the most significant for the development of national Czech opera, even though its libretto, like many others, will always be an obstacle to its [wider] dissemination.’Footnote 131

Two broader conclusions can be drawn from the events of 1885 at the Hofoper. The first concerns the relationships and dynamics among the multiple nationalities that coexisted in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Though industrialised and highly literate, Czechs were a relatively small national group and a subordinate population, from the perspective of Vienna. However, the discourses in Prague show that, as much as Czech critics were annoyed with Dvořák's treatment in the Viennese theatre and press, they were ultimately willing to give Viennese audiences the benefit of the doubt and refused to occupy a position of (perceived) cultural inferiority within the Empire. Such a feeling was likely misguided when it came to certain members of the Viennese public. Writing in reference to the late 1890s, Campo-Bowen claims that ‘Dvořák's characterization as a naively creative Czech “Other” was firmly entrenched in the imperial capital.’Footnote 132 Even so, on the whole, their arguments show that they believed – whether misguidedly or not – that the riots had more to do with repertoire choice than any darker social agenda. The latter does not even enter the discussion, apart from a few oblique references to Viennese prejudice. Additionally, the reviews reveal that many Czech critics regarded Hanslick – a central and well-respected figure on the Viennese music scene – as an ally and considered the Imperial Court Opera not to be utterly impenetrable. For them, breaking through on the Hofoper stage was merely a matter of devising the right strategy.

Second, the incident is instructive because of what it tells about the aesthetic biases and attitudes of the Czech critics. In spite of the early success of The Cunning Peasant at the Prague Provisional Theatre, its disastrous run at the Hofoper consolidated the pecking order among opera composers in the Czech lands. It served to reinforce Smetana's primacy, and Dvořák would continue to play second fiddle to his older contemporary, at least when it came to writing a work that would appropriately represent the Czech nation on the larger stage of the Imperial Court Opera – a stage that was viewed by many as the portal to international acclaim. Regardless of Dvořák's reputation as a country bumpkin next to the relatively cosmopolitan Smetana, it was The Bartered Bride that set the gold standard for idealised rurality in the eyes of the Czech critics. Proof positive for this assessment came in 1892, when Smetana's famous comic opera was received enthusiastically by the Viennese at the International Exhibition, and by comparison Dvořák's Dimitrij had a lacklustre showing at the same event. Those critics who had warned against staging The Cunning Peasant in Vienna back in 1885 were vindicated on this occasion, and the Czech operatic hierarchy crystallised further.

To close, it is worth turning the spotlight on Dvořák himself. As was his custom, Dvořák did not engage in the polemics, nor did he comment on the riots in his personal letters: undoubtedly, this was an episode that he preferred to forget. Yet, he did make one incisive remark about the event on the pages of his St Ludmila score, cited at the outset of this article: he likened the Viennese reception of his opera to an ‘execution’. His choice of word is significant here. Executions are political acts, carried out by the state and typically associated with a degree of public humiliation, both of which are important connotations that Dvořák seems to be conjuring up. Moučka's use of the term ‘execution’ has some of the same implications. Just before using the ‘execution’ metaphor, Moučka writes: ‘The vast majority of the Viennese audience and critics lost themselves in the task of trying to destroy and humiliate this work just because it comes from the pen of a Czech.’Footnote 133 The image of a defenceless Czech peasant being subjected to a death sentence at the hands of the Austrian state is quite potent and does not cast the Imperial Court Opera in the best light. In the end, then, the incident did not so much reflect badly on Dvořák as on the imperial project,Footnote 134 which relied on the peaceable coexistence of several national groups for its continuation and was weakened by internal strife and intolerance, of which the Hofoper riots were a prime example. Moreover, even if it likely offered little consolation, David Brodbeck notes that Dvořák must have been aware at the time that the ideology fuelling the riots – völkisch pan-Germanness – only had a marginal presence in Habsburg Austria,Footnote 135 and already by the mid-1880s, Dvořák was gradually discovering that Vienna was by no means the only avenue by which success beyond the Czech borders could be achieved. The severest blow to the composer, however, came in his efforts to assert himself specifically in the realm of opera. His aspirations in the genre had suffered a major setback, both at home and abroad, as a result of the Hofoper scandal. In this area at least, the struggle for Dvořák – Prague's ‘cunning peasant’ – was far from over.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S095458672200012X.