Introduction

A meningocoele refers to protrusion of meninges through a defect in the skull and dura. Posterior skull base meningocoeles are a rare entity and may be clinically occult. We describe an extremely rare, if not unique, case of a meningocoele enlarging the jugular foramen in an adult patient with neurofibromatosis type 1 and discuss possible aetiological factors that may have led to its development.

Case report

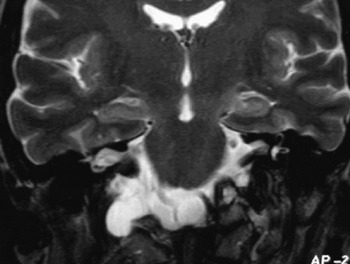

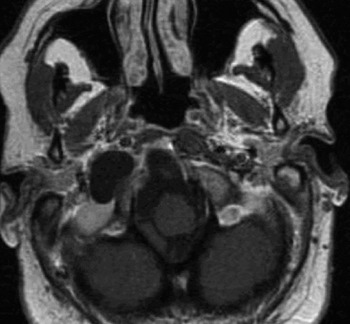

A 48-year-old female with known neurofibromatosis type 1 presented with a 12-month history of episodic positional vertigo. Each bout was very brief, lasting for no more than a few minutes. Attacks were not associated with auditory hallucinations. There was no history of head trauma, tinnitus, hearing loss or sepsis. The patient had multiple, cutaneous, café-au-lait patches and peripheral neurofibromas. She had no cranial nerve palsies or focal neurological signs. A pure tone audiogram was within normal limits for her age. A computed tomography (CT) scan showed widening of the right jugular foramen by a sharply circumscribed low-density lesion. There was moulding and pressure erosion of the adjacent bones (Figure 1). The lesion was of nearly the same density as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and appeared continuous with CSF of the right cerebello-medullary angle cistern. The internal acoustic meatus was normal and the inner-ear structures were preserved. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a sharply circumscribed lesion, isointense to CSF signal on all pulse sequences, expanding the jugular foramen and extruding out of the skull base into the carotid space (Figures 2 and 3). There was no enhancement following contrast administration (Figure 4). A FLAIR (fluid attenuation and inversion recovery) sequence showed complete suppression of signal and a diffusion-weighted sequence demonstrated free diffusion within the lesion (Figure 5), so confirming the diagnosis of a CSF containing structure i.e. a meningocoele and differentiating it from an epidermoid cyst. There was no other recognised intracranial or calvarial abnormality associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 on the imaging studies. As the patient was relatively asymptomatic, an annual follow up was suggested by imaging and the lesion continued to remain stable over a three-year period.

Fig. 1 Axial CT showing expansion of the right jugular foramen with thinning of the adjacent petrous and occipital bones on bone window algorithms. Note the enlarged right jugular foramen (small black arrow), normal left jugular foramen (long black arrow) and thinning of the occipital bone (white arrow).

Fig. 2 Axial T2 weighted MRI showing the T2 hyperintense meningocoele expanding the jugular foramen (long arrow) and extending subcranially. Note anterior displacement of the internal carotid artery (small arrow) and normal flow void of the left jugular vein (block arrow).

Fig. 3 Coronal T2 weighted image showing continuation of the right cerebellomedullary cistern with the meningocoele sac.

Fig. 4 Axial T1 weighted post contrast image shows that the lesion has similar signal intensity as CSF without any demonstrating enhancement.

Fig. 5 Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map shows that the lesion returns similar signal as CSF demonstrating free diffusion.

Discussion

A cephalocoele refers to protrusion of intracranial contents through a congenital defect in the calvarium and dura. The sac may contain meninges (meningocoele), meninges and brain tissue (meningo-encephalocoele), or meninges, brain and ventricles (meningo-encephalo-cystocoele).Reference Laine, Nadel and Braun1, Reference Hunt and Hobar2, Reference David and Proudman3 Broadly speaking, cephalocoeles may be either primary (where there is no pre-existing skull defect) or secondary (in the presence of an existing skull defect). Primary cephalocoeles may be occipital (developing between the lambda and foramen magnum), parietal (situated between bregma and lambda), sinicipital (at the junction of frontal and ethmoid bones) or basal (at the junction of sphenoid and ethmoid bones). Sinicipital cephalocoeles may be further subclassified as naso-frontal, naso-ethmoidal, naso-orbital or combined. Basal cephalocoeles are also subclassified as transethmoidal, spheno-ethmoidal, spheno-orbital, spheno-maxillary and transsphenoidal.Reference David and Proudman3 Sphenoidal cephalocoeles may develop through any part of the sphenoid bone but defects through the sphenoidal body are commoner than defects in the ala.Reference Elster and Branch4 Alternatively, secondary cephalocoeles may be associated with craniofacial clefts, surgery or trauma.

Most cephalocoeles are congenital and are thought to represent failure of neural tube fusion, but other aetiologies have also been proposed. The commoner congenital fronto-nasal cephalocoeles are thought to be due to failure of regression of a dural diverticulum between the frontal and nasal bones. This diverticulum contacts with skin and adheres to it leaving a bony gap through which the sac herniates out.Reference Hunt and Hobar2 Sphenoid cephalocoeles are either due to a persistent craniopharyngeal canal or failure of development of the multiple ossification centres of the sphenoid bone.Reference Laine, Nadel and Braun1 Spontaneous meningocoeles into the middle ear through defects in the tegmen plate are even less common. They present as middle-ear masses.Reference Gray, Willinsky, Rutka and Tator5 Skull base cephalocoeles other than at these sites are exceedingly rare. Larsen et al. reported a case of skull base meningoencephalocoele in a neonate. It had widened the jugular foramen and this is the only previously reported case of a cephalocoele found at this site.Reference Larsen, Hudgins and Hunter6

The association of neurofibromatosis type 1 with spinal meningocoeles is well known. Lateral and anterior thoracic meningocoeles are often found in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 due to pressure differences between the thorax and subarachnoid space superimposed on bony defects.Reference Fortman, Kuszyk, Urban and Fishman7 The association of neurofibromatosis type 1 with sphenoid wing dysplasia is also well recognised. There are case reports of orbital cephalocoeles through defects in the sphenoid bone in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 that present as exophthalmos.Reference Clauser, Carinci and Galie8, Reference de Vries, Freihofer, Menovsky and Cruysberg9 Aside from these, however, the occurrence of meningocoeles through the skull base in neurofibromatosis type 1 is extremely rare. Kurimoto described a patient who presented with a soft posterior neck mass, which was a meningocoele produced by a large bony defect in the occipital bone posterolateral to the foramen magnum.Reference Kurimoto, Hirashima, Hayashi, Endo, Ohi and Okamoto10 This was the only other case report, which described a posterior fossa meningocoele in a patient with neurofibromatosis type 1. Unlike our patient, the jugular foramen was not involved and the skull defect involved the occipital bone posterolateral to the foramen magnum. Meningocoeles extending into the pterygopalatine fossaReference Chapman, Curtin and Cunningham11 and frontobasal regionReference Soames, Williams, Bannister, Berry, Collins, Dyson and Dussek12 have also been described in the setting of neurofibromatosis type 1. To the best of our knowledge, the association of neurofibromatosis type 1 with a skull base meningocoele enlarging the jugular foramen and extending into the carotid space has not been previously reported.

• Posterior skull base meningocoeles in neurofibromatosis type 1 are a rare entity. This paper describes the first case of a skull base meningocoele enlarging the jugular foramen in a patient with neurofibromatosis type 1

• It is postulated that mesodermal dysplasia, which underlies neurofibromatosis type 1, is responsible in some way for its development. The meningocoele could either result from a severe form of dural ectasia or from dysplastic, weakened bone at the skull base

Understanding the underlying pathophysiological basis of neurofibromatosis type 1 provides an insight into its possible formation. Mesodermal defects of the neural axis in neurofibromatosis type 1 are well recognised. The rare basal meningocoeles in neurofibromatosis type 1 are likely to represent a variant of cranial nerve dural ectasias that are occasionally seen in individuals with neurofibromatosis type 1. These are thought to be due to a primary mesenchymal defect, which is also responsible for other associated abnormalities such as sphenoid dysplasias.Reference Chapman, Curtin and Cunningham11

Anatomically, the jugular foramen is located between the occipital and the petrous part of the temporal bones. The anterior portion of this foramen transmits the inferior petrosal sinus; the posterior portion, the transverse sinus; and the intermediate portion, the glossopharyngeal, vagus, and accessory nerves.Reference Probst13 We postulate two theories, which could have led to the development of this meningocoele. In the setting of neurofibromatosis type 1 there could have been a primary bone dysplasia involving the posterior skull base similar to the commoner sphenoid dysplasias that resulted in a pre-existing or potential bony defect. This potential defect or dysplastic, weakened bone around the jugular foramen would have expanded due to chronic CSF pulsations with consequent protrusion of meninges. De Vries et al. described a patient who presented with pulsatile exophthalmos in which the entire right frontotemporal skull was found to be dysplastic intra-operatively and showed craniolacuna. They postulated that the weakened bone would not have been able to resist CSF pulsations, leading to slow bony resorption.Reference de Vries, Freihofer, Menovsky and Cruysberg9 It is possible that a similar pathological process would have taken place in our patient. Kaufman et al. stated that thinning of bone and a consequent skull defect could develop with normal pulsations of CSF.Reference Kaufman, Yonas, White and Miller14 On the other hand, in the absence of a primary bony defect or dysplasia, the meningocoele could, in fact, represent an extreme variant of a dural ectasia associated with one of the three lower cranial nerves that exit through the jugular foramen. This hypothesis has been suggested previously by Chapman et al. Dural ectasia in neurofibromatosis type 1 has been reported frequently in association with spinal, optic and acoustic nerves and Chapman et al. also described dilatation of the facial nerve canal by fluid signal.Reference Kurimoto, Hirashima, Hayashi, Endo, Ohi and Okamoto10, Reference Chapman, Curtin and Cunningham11 Though it is unclear in our case whether the coexistence of neurofibromatosis type 1 was responsible for the presence of the meningocoele, it is highly likely to have contributed to its development.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we describe a case of a meningocoele extending through the jugular foramen in an adult and a unique association with neurofibromatosis type 1. It is postulated that factors influencing the formation of such a meningocoele may either be mesodermal dysplasia leading to defective bony development or dural ectasia of cranial nerve sheaths, both of which are well known associations of neurofibromatosis type 1.