Introduction

Filial obligation has long been regarded as a cornerstone value in traditional issei (pre-war first-generation Japanese Canadian) culture (Ayukawa, Reference Ayukawa2008; Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi2000). Yet despite the centrality of and emphasis on filial obligation as a core value in the social support and caregiving literature on Asian families over the life course (e.g., Pyke, Reference Pyke2000; Sorensen & Kim, Reference Sorensen, Kim and Ikels2004; Sung, Reference Sung2001; Zhang, Reference Zhang and Ikels2004), it is surprising that the intergenerational stake hypothesis, with its focus on filial relationships, has not been applied to intergenerational studies of social support in Asian families in North America. The current study addresses this gap in the literature by exploring generational differences in filial obligation among older parents and adult children in post-immigrantFootnote 1 Japanese Canadian families, a group that is regarded as highly assimilated and acculturated due, in large part, to the rapid “Canadianization” of the community after wartime internment and forced dispersal (Ayukawa, Reference Ayukawa2008; Miki, Reference Miki2004; Oikawa, Reference Oikawa2000; Sugiman, Reference Sugiman2004).

Literature Review

Filial obligation is a cultural schema or norm (influencing ideas about appropriate behaviour) that can manifest at the individual level as a personal attitude towards the importance of parent support/care. As noted previously, norms supportive of filial obligation are especially salient in traditional Asian cultures, in which they continue to be reinforced by values of collectivism and interdependence, and by the practice of filial piety. At the individual level, attitudes towards filial obligation are not strict reflections of cultural norms, but are personalized and influenced by factors such as gender (Rossi, Reference Rossi, Bengtson and Achenbaum1993), self-reported health, the availability of family members (Franks, Pierce, & Dwyer, Reference Franks, Pierce and Dwyer2003), and the context of changing family relationships over time (Stein, Wemmerus, Ward, Gaines, Freeberg, & Jewell, Reference Stein, Wemmerus, Ward, Gaines, Freeberg and Jewell1998).

Empirical research on the congruence of filial responsibility attitudes between younger and older generations has emerged largely out of concerns about the potentially negative effects of incongruence on the experience and outcomes of caregiving and receiving in filial dyads. As a framework often used to explore parent-child relationships in later life, the now-classic intergenerational stake hypothesis (Bengtson & Kuypers, Reference Bengtson and Kuypers1971) is relevant to understanding differences in filial obligation between generations. The hypothesis maintains that parents and children have different expectations and understandings of the filial relationship due to developmental differences in their concerns or “stakes.” Parents’ concerns focus on the continuity of values they have internalized as important over the life course and with the close family relationships they have developed over time. Accordingly, they tend to minimize conflict and overstate solidarity with their children. Children, on the other hand, have a tendency to understate intergenerational solidarity and overstate differences, in an attempt to establish autonomy and independence from their parents.

Although originally developed to examine parent-child relationships in the early stages of the family life course, the intergenerational stake hypothesis has been applied to research on older parent–adult child relationships. In particular, Gesser, Marshall, and Rosenthal (Reference Gesser, Marshall and Rosenthal1985), using a dyadic rather than the more common comparison group design, have found support for the hypothesis in a sample of older parents and adult children. Specifically, their results indicate that older parents are concerned more with value continuity, while adult children desire separate value systems and identities that are distinct from their parents. The intergenerational stake hypothesis emphasizes generational differences in attitudes about family relationships (such as filial obligation), and explains these with reference to differences in relational needs (i.e., it tends to be focused on both the individual and dyad as units of analysis).

In addition, microlevel family dynamics like the quality of the parent-child relationship (Gesser et al., Reference Gesser, Marshall and Rosenthal1985) may also contribute to the emergence of differing value systems as parents and children negotiate and renegotiate their filial relationships over time. Such dynamics, it can be reasonably argued, may be key factors in understanding differences in parent-child value adherence to filial obligation, especially in ethno-cultural families where both generations are native-born (i.e., families that are one generation or more removed from traditional ethnic cultural understandings).

Geographical proximity may also affect congruence on values. Research by Funk (Reference Funk2007) on the nature of filial obligation has indicated that living close to or in the same city as parents acted for some participants as a “trigger” for feelings of responsibility for parents. Likewise, findings from McDonough-Mercier, Shelley, and Wall (Reference McDonough-Mercier, Shelley and Wall1997) have suggested that “for those children who are close at hand, their parents are nearby and the children feel responsible for them” (pp. 183–184).

Despite its appropriateness for exploring the nature of relationships in ethno-culturally diverse families, the intergenerational stake hypothesis has not been extensively tested with such samples. Further, although some research does identify discrepancies in values of filial responsibility and obligation between parent-child generations, much research suggests that in fact, parents may have lower filial responsibility expectations of their children (in terms of the level and nature of involvement), and children have higher expectations of themselves, and thus more strictly adhere to ideas of unconditional filial responsibility and obligation (Blieszner & Hamon, Reference Blieszner, Hamon, Dwyer and Coward1992; Blust & Scheidt, Reference Blust and Scheidt1988; Donorfio, Reference Donorfio1996; Groger & Mayberry, Reference Groger and Mayberry2001; Peek, Coward, Peek, & Lee, Reference Peek, Coward, Peek and Lee1998). These findings appear to contradict an intergenerational stake hypothesis, which seeks to explain generational discrepancies by focusing on a parent’s greater psychological stake in the filial relationship.

Gender has also been discussed in relation to the intergenerational stake hypothesis, providing support for the idea that mothers may have higher expectations. Rossi (Reference Rossi, Bengtson and Achenbaum1993) suggested that women in particular have a greater investment in developing and maintaining relationships with their children over the life course than their male counterparts for a number of different reasons. First, women function as the primary informal caregivers to spouses, children, and older parents in mid- to later life and thus have a greater lived understanding (empathy) of the expectations placed on individuals, particularly daughters, who take on supportive roles within the family. Second, motherhood assumes a more central role in women’s lives than fatherhood for men, because women are socialized to be more expressive and nurturing than men and, thus, are more likely to assume the family “kin-keeper” role (Rosenthal, Reference Rosenthal1985). Finally, historically, women have had greater economic interdependence with other family members because they are (1) typically the supplementary (i.e., lower) income earner in the family; and (2) likely to experience a significant reduction in income in later life after the onset of illness in and/or death of their spouse. We would, therefore, expect to see gender differences in the development of generational stakes in both parents (mothers and fathers) and children (daughters and sons).

The intergenerational stake hypothesis, as mentioned, tends to focus on attitudinal differences between parents and children without proper attention to the significance of changing contexts over the life course. Likewise, research on generational value differences and social support in ethno-cultural minority groups (e.g., Burr & Mutchler, Reference Burr and Mutchler1999; Hashimoto, Reference Hashimoto1996; Ishii-Kuntz, Reference Ishii-Kuntz1997; Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi2000; Matsuoka, Reference Matsuoka1993; Sugiman & Nishio, Reference Sugiman and Nishio1983) often failed to take into account the myriad of socio-structural, historical, and cultural influences on parent-child relationships over the family life course. Given these limitations, it is important that examinations of generational differences incorporate understandings of the different generational impacts of broader contextual influences (such as individualization). For instance, exploring the nature of cross-generational differences in filial responsibility, Hareven (Reference Hareven1994) proposed that over the past century, the timing of life course events has shifted from being more closely articulated to collective family needs to being more individualized (i.e., reflective of specific age norms). Indeed, others have suggested that in a North American context, social, economic, and demographic changes have created increased structural opportunities for individual choice, which, when combined with a cultural emphasis on individualism, contributes to the “individualization” of family relationships (Beck & Beck-Gernsheim, Reference Beck and Beck-Gernsheim2001). In this context, family commitments may be perceived as increasingly voluntary and involving greater choice and fewer obligations than in the past. Although the influence of individualism on the actual individualization of family relationships is uncertain, the language and rhetoric of individualism, which privileges independence between family members, is an important component of socialization in Western societies, with a potentially salient influence on individual constructions of family responsibility and potentially, through a generational socialization effect, the development of disparate generational stakes.

This may even be the case among families and cultures whose traditional value systems are strongly grounded in Confucianism. Although Hashimoto (Reference Hashimoto and Ikels2004) described how children in Japan continue to be socialized to filial behaviour as well as to the ideal qualities of agreeableness and congeniality, and Ikels (Reference Ikels and Ikels2004) pointed out that filial behaviour is associated with reliability, loyalty, and honour in Asia generally, not all research in contemporary Asian societies has supported these findings. Indeed, Sung (Reference Sung2001) argued that expressions of filial piety even in Asia – in fact intergenerational relations as a whole – have become increasingly based on affection and patterns of reciprocal support. Holroyd (Reference Holroyd2001, Reference Holroyd2003) suggested a shift away from duty-centred and control models of filial piety towards an obligation to care equally as strong, yet motivated by affection and emphasizing the autonomy of youth. Wang (Reference Wang and Ikels2004), in China, has described how traditional patterns of multigenerational co-residence are being replaced by marriage in the parents’ household followed by a short stay, which functions as symbolic expressions of filial piety. Finally, Sorensen and Kim (Reference Sorensen, Kim and Ikels2004) noted a decline in observing the “full funeral” tradition and the revision or adjustment of other ceremonies in Korea, as evidence of pragmatic adaptation of “standards of performance to new situations” (p. 159). Considering this evidence, it is reasonable to assume that divergence in values between parents and children may reflect changing structural realities faced by younger generations in Asia, an assumption that would be relevant and interesting to explore in Asian immigrant and post-immigrant families in North America.

An appreciation of changing structural realities is a main focus of the life course perspective, which, in the context of families, underscores the differential impact of generation-specific socio-structural, cultural, and historical forces on adherence to familial values. For example, it can be argued that the collective experience of systemic racial discrimination and marginalization of nisei (second generation pre-war Japanese Canadian) parents early in their life course has in many important yet implicit ways shaped the degree to which they adhere to and understand the traditional issei (first generation pre-war Japanese Canadian) value of filial obligation and, as a result, their expectations for social support from their children in later life (Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi2000). Sansei children, not having experienced similar socio-political exclusion as children and/or young adults and having grown up in ethno-culturally diverse communities as part of the “Canadian mosaic,” may have more individualistic (versus familiastic) ideals vis-à-vis the provision of social support to parents (Kobayashi). Yet although ethnic variations in adherence to norms of filial responsibility have been studied (e.g., Burr & Mutchler, Reference Burr and Mutchler1999), the importance of macro-social, historical, and cultural exigencies in the etiology of generational value systems have not been addressed in tests of the intergenerational stake hypothesis. Such understandings would certainly provide insights into any discrepancies between generations (a hypothesis that also aligns with the intergenerational stake hypothesis).

Filial Obligation in Later Life Japanese Canadian Families: A BC Study

Given the historical significance of filial obligation as a foundational value in Asian immigrant groups (such as Japanese Canadians), the extent to which later generations (i.e., the nisei and sansei) adhere to this value may have implications for social support exchanges between aging parents and their adult children. Accordingly, the study in this article examined congruence or incongruence on filial obligation in older parent-adult child dyads in Japanese Canadian families in British Columbia using semi-structured interview data. Drawing on the intergenerational stake hypothesis, and extending it to consider the significance of differential generational experiences, particularly the life-altering experience of the internment and forced dispersal of the nisei early in the life course, we posed the following research questions. First, is there a discrepancy between parents and children in their attitudes on filial obligation? Second, if a discrepancy exists, to what can it be attributed (e.g., higher or lower parental expectations)? A third and final question asked, what is the relationship between a parent’s characteristics and generational discrepancies in attitudes on filial obligation? Specifically, in an exploratory extension of the intergenerational stake hypothesis (which explains generational discrepancies by reference to “intergenerational stake”), we examined the relationship between intergenerational value congruence/divergence and a parent’s gender, health status, marital status, and geographic proximity.

A focus on Japanese Canadians provided an opportunity to study an Asian ethno-cultural group whose traditional (i.e., first generation) Meiji-era value system is rooted in Confucianism (i.e., is similar to the Chinese and Korean value systems), but whose current members, according to the 2006 Census, are largely (63.2%) Canadian-born (Statistics Canada, 2008), at least one or two generations removed from an immigrant experience. In addition, and perhaps most important and interesting in this case, is the opportunity to examine parent-child relationships in a population whose first and second generations have had a unique and complex socio-political history of exclusion and marginalization in Canada, and to explore the influence that this has had on the nature and process of acculturation in its third and later generations (Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi2000; Sugiman, Reference Sugiman2004).

Methods

Data Source and Sampling

This study used data gathered from 100 older nisei parents (55–85 years) and 100 of their adult sansei children (31–50 years) who agreed to participate in face-to-face interviews from September 1998 to December 2000. The sample was drawn from a list of 9,983 Japanese surnames (including mailing addresses and telephone numbers) in the province of British Columbia (BC). The original sampling frame was a compilation of provincial subscriber lists from the “Nikkei Voice”Footnote 2 and the bulletin Footnote 3. In cases where the husband and wife were listed as a single subscriber, the names were separated out as two separate individuals in the frame. The names and contact information from the lists were then checked for accuracy and exhaustiveness using the Canada Phone CD-ROM for Japanese surnames. As a result of this validity check, 1,204 names were added to arrive at the final sampling frame. The list was then stratified by size of place of residence: large (population 90,000+), medium (30,000–89,999), small (10,000–29,999) and very small (less than 10,000). Screening telephone calls were made to random samples of individuals from each stratum.

To be eligible for inclusion in the sampling frame, the contacted individual had to be (1) a second-generation Japanese Canadian, aged 55 years and over, with a living child (third-generation) between the ages of 30 and 50 years living in BC, who was non-institutionalized and willing to participate in the study; or (2) a third-generation Japanese Canadian, aged 30 to 50 years, with a living parent (second-generation) at least 55 years of age living in BC, who was non-institutionalized and willing to participate. All participants identified the other dyad participant to be contacted. We acknowledge that such a selection process may have introduced some sampling bias into the study; however, the vast majority of eligible respondents only agreed to participate contingent on this self-directed selection process.

Data Collection

A survey interview instrument with both closed- and open-ended questions was developed for the study (based in part on that used by Gee and Chappell [Reference Gee and Chappell1997] for their study on ethnic group membership and old age in Chinese Canadian families). Revisions were made after pilot tests were conducted with seven parent-child dyads in the Greater Vancouver area.

Parents and children were interviewed separately to ensure that participants’ responses would not be influenced by the presence of their parent/child. The majority of interviews took place in participants’ homes, with the exception of three interviews with children that were conducted in public places at their request.

Operationalization of Congruence

Congruence on filial obligation between older parents and adult children is operationalized in three ways: (1) degree congruence – similarity between dyad members in the levels of expressed adherence to filial obligation; (2) content congruence – similarity between dyad members in the content and context or reasons (i.e., the justifications, explanations, and expressions of support or disagreement) for filial obligation; and (3) overall congruence – similarity between dyad members on both degree and content congruence. These will be described, in turn.

First, expressed adherence to filial obligation was indicated by participants’ responses to the closed-ended question, “Do you agree with this statement, ‘Children should take care of their parents in old age?’” (Responses: Yes, No, Depends (specify), and No Opinion). This question was selected for inclusion as the primary measure of filial obligation given its centrality in Kitano’s (Reference Kitano1976) widely validated scale on this value with immigrant and post-immigrant visible minority Americans. Degree congruence, an indicator at the level of the dyad, was determined by the similarity of responses between parents and children to this question (similarity was defined as both dyad members expressing identical response options, either both positive [yes/yes] or both negative [no/no]; all other combinations were defined as incongruent or divergent).

Content congruence between dyad members refers to the similarity of coded themes in open-ended responses to the nested question (following from the degree congruence question), “Please tell me why you feel this way. Elaborate as much as possible on your previous response.” The assessment of content congruence therefore involved an initial qualitative analysis in order to code responses between dyad members as congruent or incongruent. Specifically, the method used was content analysis, for gathering and analyzing (i.e., coding) the content of transcribed text from semi-structured interviews with participants. In this way, qualitative responses were translated into quantitative rankings of congruence, a method that has been used in previous studies on spousal caregiver congruence (e.g., Chappell & Kuehne, Reference Chappell and Kuehne1998). Specifically, parents and children are congruent (positive or negative) if they use the same or similar expressions (i.e., words, and stories or recollections) to discuss their connection to filial obligation. For example, if a parent and child both agree that children do not have an obligation to take care of parents in later life unless a serious health issue arises for the parent, then they have high negative content congruence because they both qualify their low level of adherence to the value of filial obligation using similar rationalizations. Thus, it is expected that content congruence will be related to degree congruence.

Finally, the overall congruence measure is calculated to determine the extent to which this is true in the sample. Overall congruence, or similarity between dyad members on both degree and content congruence, was assessed by taking the sum of degree and content congruence for a dyad.

Additional Variables Used in the Analyses

In the process of analyzing and interpreting the content of parents’ and children’s responses on filial obligation for this study, several factors were identified as salient (i.e., they were used to qualify support in open-ended responses to the filial obligation statement). Specifically, parents’ gender,Footnote 4 health, and marital status and geographic proximity were articulated as triggers to the enactment of support and emerged as important themes in qualitative analyses of the open-ended responses. Thus, quantitative measures of these key socio-demographic factors were selected for additional bivariate analyses, exploring their relationship with congruence on filial obligation. These included (1) gender of parent (male, female); (2) self-reported health status of parent (very good/excellent, good, fair/poor); (3) marital status of parent (married, widowed/divorced); and (4) geographic proximity (very close – within 50 km, close – 51–200 km, and not very close – 201+ km).

Analyses

After assessing and operationalizing congruence and performing the content analysis of the qualitative data (as just explained), we examined the extent of both content and degree of congruence among dyads through descriptive statistics. High incongruence between generations would support the intergenerational stake hypothesis, as well as providing some support for a life course perspective that focuses on the impact of different generational experiences.

Due to the small sample size and the skewed univariate distributions for congruence, all additional quantitative analyses were conducted at the bivariate level. Specifically, as we have explained, we examined bivariate relationships between overall congruence and parent’s gender, a parent’s perceived health status, marital status, and geographic proximity using χ2 as the measure of association.

Results

Sample Description

Although a table is not provided for the gender composition of the dyads, the breakdown is as follows: 37 per cent of the nisei parent sample were males and 63 per cent were females with a mean age of 39 years, while 43 per cent of the sansei child sample were males and 57 per cent were females with a mean age of 68 years.

Content Analysis: Qualitative Findings

Themes from the content analysis of the open-ended interview data were used to determine the salient characteristics of parents for the bivariate analyses. The findings also provided preliminary insights into the meaning of filial obligation to each member of the dyad. In contemporary Japanese Canadian families, it can be reasoned that the value has been negotiated and re-negotiated in the context of changing socio-structural, historical, and cultural forces. Content analysis of the open-ended responses on value statements from parents and children revealed similar yet somewhat different “translated” understandings of filial obligation that were, in many cases, situation-based. For example, according to both older parents and adult children, overall congruence on filial obligation was dependent to a large degree on the health and marital status of the parent (i.e., a change in a parent’s health or marital status in later life may be perceived as an impetus or trigger in the enactment of a child’s sense of filial obligation and parent’s expectations of the child for support). This understanding reflects the cross-generational process of meaning transformation that this core value has undergone in Japanese Canadian families – that is, to the issei, filial obligation was almost entirely based or dependent on a child’s obligation from birth to repay his/her parents for all of their efforts in giving birth to and raising him/her, and its enactment was not strongly tied to a parent’s gender and/or a change in a parent’s status, be it health or marital (Ayukawa, Reference Ayukawa2008).

Intergenerational Congruence/Incongruence: Descriptive Findings

A descriptive examination of degree and content congruence indicates that parent-child dyads in our study were, for the most part, congruent. Overall, more than three-quarters of the dyads (79%) indicated congruence on the degree of adherence to filial obligation, while two thirds (66%) showed congruence on response content (see Table 1). Just under two thirds (62%) indicated congruence on both degree of adherence and content (see Table 1).

Table 1: Degree, content, and overall congruence (n = 100 dyads)

A very small number of mother-child dyads (7%) were incongruent on degree of adherence to filial obligation, while content incongruence for mother-child dyads was slightly higher at 17 per cent (see Table 2). For father-child dyads, incongruence on degree of adherence was noted for a minority of pairs at 23 per cent. Content incongruence was noted for a higher number (31%) of father-child dyads. Two qualitative examples of incongruence on content included these:

Mother: I am grateful that my son visits us as often as he does. He works out in Nelson for BC Hydro, so we only really get to see him on weekends. I’m glad that he still comes around to help his father out around the orchard though. We really appreciate the extra hand especially around picking time.

Son: I go home as often as I can, but I don’t get the feeling that my parents really appreciate the times that I do come around. Lately, mom has been nagging me to get my life in order – you know get married, take over the orchard, raise a family. I don’t need that kind of pressure right now. I have enough to deal with at work and home so I had just as soon not go [to visit them].

Father: Even though she [my daughter] stops by to visit once a week, it’s not enough. She only spends a couple of hours with us. My wife is getting older and she needs more help around the house. I figure that daughters should take care of their parents a little better than that, don’t you? Show some more respect.

Daughter: I think that my parents look forward to my weekly visits. Mom always has this great meal prepared – home-cooked Japanese meals, they’re the best – and my dad is always anxious to talk about the latest “family” crisis. I’m like his “sounding board” since I don’t think that my mom really pays much attention to him anymore. She just puts up with his rants and raves now.

Table 2: Degree, content, and overall congruence by sex of parent (n = 100 dyads)

In mother-son and mother-daughter pairs, an overwhelming majority (93%) were degree congruent on adherence to filial obligation. Of particular interest are the content congruence results for mother-son and mother-daughter dyads which indicated that 83 per cent of emergent themes in support of positive adherence to filial obligation were congruent. The following qualitative examples highlight the salience of filial obligation in one positive and one negative value congruent mother-child dyad.

Mother: My relationship with my son is very close. He lives in Kelowna, just a 20-minute drive away from my house, so I get to see him quite often. He always makes a point of checking in on me to see if I need anything. Ever since my husband died three years ago, my son has taken real good care of me. He doesn’t let me be alone [laughs].

Son: Mom and I are pretty close. I have dinner at her place a couple of times a week, and I’m always dropping in to see how she’s doing. I don’t like the fact that she’s living all alone in that big house. I’m hoping that she’ll move to a smaller place in Kelowna. I’d feel better if she moved to an apartment in a retirement complex or something. There’s a Japanese Canadian complex not too far away, but she doesn’t seem to want to be with other Japanese. Maybe it’s that internment experience that did that to her. I don’t know. She is getting too old to take care of the house anymore. I worry about her all the time it seems.

Mother: I don’t agree with that [children should take care of their parents in old age]. Kids shouldn’t feel burdened by this sense of obligation. That’s too Japanese, too traditional in this day and age. After all, we are Canadians; we’re not living in Japan.

Son: You shouldn’t feel obligated to take care of your parents. Things like this should come naturally. I’m not saying that I won’t do it, but I don’t want to feel “guilted” into doing it, and I know that my mom wouldn’t make me feel guilty about not doing it if I couldn’t. She’s not very traditional [Japanese] in her thinking. I think that the wartime experience really made her want to be a Canadian really fast. She didn’t want to identify with too many things “Japanese.”

In father-son and father-daughter dyads, just over three-quarters (77%) were degree congruent; however, only 69 per cent responded similarly when asked to comment on the reasons for adherence to the value (i.e., content congruence). The following are two qualitative illustrations of content congruence on responses to the filial obligation statement between fathers and their children.

Father: I can always count on him [my son] if I need him. He and his family live close by and they’re always checking up on us [he and his wife]. Even with his busy life, he still comes by to help out with odd jobs and chores around the house.

Son: My parents are getting older. Dad can no longer maintain the place like he used to when we were younger. I’d like to help out more, but I have a busy dental practice in town which makes it difficult to see them [parents] as much as I would like to. Still, I guess that I do get out to see them regularly – which is at least once a week.

Father: I look forward to seeing her [my daughter] during the week. I usually drop by her store every other day, just to see how she’s doing. Sometimes there’s something that she wants me to help out with; other times, we just have coffee. It’s become part of my routine since retiring. I enjoy spending time with her. It’s something that my parents were never able to do for me given what happened to us during the war and all.

Daughter: My dad and I have always been close. He has supported my efforts emotionally as well as financially. I wouldn’t have been able to do this [open her own store] without his support….It’s nice that he comes by to see me so often during the week. I think that he enjoys helping with accounting and inventory control for the store. We spend quite a bit of time – quality time – together. I think that I really owe my father a lot; he has always been there for me. Although he doesn’t talk much about it, I know that he wants to have a better relationship with me than he ever had with his parents. The internment really did that to families you know. It made already difficult relations, very distant relations, even more strained.

For overall congruence, just under three quarters (72%) of mother-child dyads were congruent on both degree and content while just under two thirds (60%) of father-child pairs were congruent on both dimensions.

Bivariate Analyses

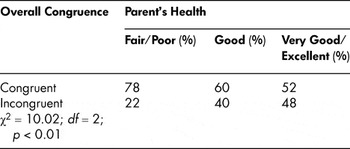

Bivariate (χ2) analyses were conducted to examine factors that may be associated with congruence. Results indicated that gender of the parent was related to degree congruence (p < 0.01: see Table 3a). Specifically, if the parent is female there is more likely to be value congruence in terms of degree of adherence. Also, perceived health status of the parent was related to degree congruence (p < 0.02); parents who perceived their health as worse (poor/fair) were more likely to be in relationships demonstrating degree congruence (Table 3b). Bivariate relationships between degree congruence and both marital status and geographical proximity were not significant (Table 3c and 3d).

Table 3: Cross-tabulations with degree congruence

A. Gender of parent (n = 100)

B. Perceived health status of parent (n = 100)

C. Marital status of parent

D. Geographic proximity

As with degree congruence, content congruence was significantly related to gender (p < 0.05) and parents’ perceived health status (p < 0.01). In addition, it was related to parents’ marital status (p < 0.05). Female parents were more likely to be in relationships that indicated congruence in the content of responses supporting the parent-child relationship, parents who perceived their health as worse were more likely to be in congruent relationships, as were parents who were widowed (see Table 4). Geographic proximity was not associated with content congruence.

Table 4: Cross tabulations with content congruence

A. Gender of parent (n = 100)

B. Perceived health status of parent (n = 100)

C. Marital status of parent (n = 100)

D. Geographic proximity

Finally, although geographic proximity was not significantly related to overall congruence, parent’s gender (p < 0.05), perceived health status (p < 0.01), and marital status (p < 0.05) all related to overall congruence (see Table 5). Specifically, mothers, parents reporting poorer health, and those who were widowed were more likely to be in dyads demonstrating overall congruence.

Table 5: Cross tabulations with overall congruence

A. Gender of parent (n = 100)

B. Perceived health status of parent (n = 100)

C. Marital status of parent (n = 100)

D. Geographic proximity (n = 100)

Discussion

The findings from this study challenge the intergenerational stake hypothesis in later life –that is, the conclusion by Gesser et al. (Reference Gesser, Marshall and Rosenthal1985) that older parents and adult children are often far apart in their adherence to traditional value systems. Specifically, the overall extent of incongruence or generational differences was very low in the sample for both mother-child and father-child dyads, but especially for mothers. These results, therefore, fail to support the intergenerational stake hypothesis and also serve to contest the idea that generational differences in life course experiences necessarily translate into attitudinal differences.

Instead, these findings provide support in an ethno-cultural post-immigrant family context for Silverstein and Bengtson’s (Reference Silverstein and Bengtson1997) conclusion that modern American families, although structurally and culturally diverse, possess an enduring form of solidarity that allows them to continue to satisfy their members’ needs in later life. Again, this is especially true for older mother-adult child relationships in Japanese Canadian families. Such a high degree of intergenerational congruence may also indicate that cultural norms of filial obligation, despite different acculturation experiences between the generations, can endure in translated (i.e., different from traditional first-generation understandings) but mutually understood forms, promoting family and, in some cases, community cohesion (Cantor & Brennan, Reference Cantor and Brennan2000; Clarke, Reference Clarke2001). Although it is beyond the scope of this study (given the data and information that was collected and the analyses performed) to conclude that this is unequivocally the case, the qualitative data certainly provide some evidence of the significant differences in life course experiences between the nisei and the sansei, differences (e.g.), the internment experience) that were mutually acknowledged as salient in some cases (see father-daughter example of content congruence). The application of a life course framework to this study (which would also presume necessary retrospective data collection) would certainly allow us to explore the significance of social-structural, historical, and cultural exigencies further, thereby enabling us to strengthen the argument that the intergenerational stake hypothesis is not supported in later life Japanese Canadian families despite disparate social, economic, and acculturation experiences.

In addition to its contribution to the literature on intergenerational relationships, the current study provides further support for past research findings on filial obligation that suggest that parent’s gender, and marital and health status, matter in understanding the nature of intergenerational support in later life families. That is, there is more likely to be a match between a parent’s level of expectations and what a child is willing to provide in terms of support if the parent is a mother, is widowed, or has poor health. Indeed, research on filial obligation has indicated that parents’ expectations intersect with these factors and play a key role in determining congruence on attitudes towards care. For example, one exception to parents’ tendency to express low expectations for future care, which may give rise to greater intergenerational congruence, might be when parents have high need for such care due to health and/or marital status issues, in which case they tend to express higher expectations (Blieszner & Hamon, Reference Blieszner, Hamon, Dwyer and Coward1992; Peek et al., Reference Peek, Coward, Peek and Lee1998).

Further, some studies have suggested that older women have higher expectations for filial responsibility, associated with their greater need for assistance in old age (Donorfio, Reference Donorfio1996). For perhaps similar reasons, Sorensen (Reference Sorensen1998) reported that daughters of low-income mothers are more likely to anticipate both task help and personal care, thereby implicating both gender and class as salient factors in the development of attitudes on filial obligation. Interestingly, class/socio-economic status issues did not emerge in our study as a major finding in the thematic analysis of the qualitative data and was subsequently not included as a key socio-demographic factor in the bivariate analyses. An inductive approach to exploring the meaning of filial obligation may capture this as well as some of the more nuanced dimensions like geographic proximity, which did not emerge as significant in relationship to intergenerational congruence.

Finally, Peek et al. linked women’s higher expectations to stronger perceived “claims” for support due to their greater involvement in childrearing. Indeed, any one or number of these findings could be useful and valid in constructing a better understanding of our results and therefore need to be considered more carefully in future studies on the nature of parent-child value congruence in later-life families.

What are the implications of these findings for the exchange of social support in Japanese Canadian, and more generally, in other Asian Canadian post-immigrant families in later life? Given the failure of our findings to support the intergenerational stake hypothesis in our sample, it bodes well for the continued valuation of filial obligation, albeit in translated forms, in younger generations of immigrant and post-immigrant families despite the increasing push towards an “individualization” of family relationships in North American culture (Beck & Beck-Gernsheim, Reference Beck and Beck-Gernsheim2001). However, attitudes may not necessarily translate into care behaviours, particularly when adult children face structural barriers to the provision of care (e.g., employment, competing family responsibilities). The assumption that support from adult children is a given, particularly in times of need – for example, the transition to widowhood and/or poor health – opens the door for governments further to offload responsibility for care of older adults onto families. This shift in responsibility from the state to the family has already taken root across the country as evidenced by a series of deep and enduring cuts to provincial home care programs. And so, despite the positive support outcomes that the current study suggests are possible for parent-child relations given strong family solidarity in later life, it is important to note that the implications of such solidarity may actually be negative in terms of access to formal support for adult child caregivers in the future.

Limitations and Future Research

Although the questions in the study enabled us to collect retrospective accounts from the participants, the study is still limited by the cross-sectional nature of the data collection that does not allow for a rigorous examination of changes in the parent-child relationship over time. Another limitation is that despite the use of random sampling techniques, we are unable to generalize the results from the study to the larger population of Japanese Canadians due to the selection of British Columbia residents only, whose profile may be quite different, for instance, from their Ontario-based counterparts. Also, the bivariate analyses performed on the data allow for only a cursory look at the complex relationship between important socio-demographic variables (as identified by the parents and children themselves) and congruence between older parents and adult children. It is therefore recommended that future research collect data from a larger number of dyads in a national sample to allow for multivariate analyses of the data.

Further, the current study is limited to an examination of the relationship between parental characteristics (gender, health status, marital status) on congruence in parent-child relationships. In exploring the nature of the relationship between older parents and adult children, it is important that future research examine the impact that these same characteristics in adult children have on dyadic value congruence, because the socio-demographic characteristics of both members of the dyad are important factors to consider in understanding the nature of social support in families.

What can we surmise about the measurement of intergenerational congruence from this study? Certainly, a strength of this article is its use of both quantitatively and qualitatively derived measures of congruence. However, the meaning of content congruence in the absence of degree congruence is uncertain. In addition, the fact that approximately one third of degree-congruent dyads did not offer similar explanations for their response (content incongruence) raises questions and suggests the limitations of quantitatively derived measures of congruence from qualitative data.

As indicated by Giarusso, Stallings, and Bengtson (Reference Giarusso, Stallings, Bengtson, Bengtson, Schaie and Burton1995), there are three tests of importance in examining the intergenerational stake hypothesis: (1) tests of dyadic parent-child data in addition to individual-level perceptions, (2) examinations of gender differences in intergenerational stakes, and (3) tests of parent-child interactions over time. This study, in its design, has attempted to address the first two of these tests, yet the cross-sectional nature of the data limits our ability to discuss the fluid nature of dyadic interactions in families over time. Future research should explore the extent to which the construction and re-construction of ethnic identity at different points in the life course in response to different social structural, historical, and cultural exigencies may help to explain why older nisei parent-adult sansei child dyads are so strongly congruent in their attitudes on filial obligation. Additionally, emergent research should focus on how life course variations within immigrant and post-immigrant families can help us to develop a better understanding of the nature of family ties and the cross-generational process by which immigrant and first-generation values and beliefs are transmitted and translated in the context of social support.