Introduction

Are populist actors more like a hurricane that risks undermining the quality of democracy or like a fresh breeze that reinvigorates it? On the one hand, recent episodes of populist government inclusion have sparked a revival of the view that populism constitutes a threat to democracy (e.g. Mény and Surel, Reference Mény, Surel, Mény and Surel2002a: 5–6; Taggart, Reference Taggart, Mény and Surel2002; Levitsky and Ziblatt, Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018). According to this view, populism entails a ‘risk of democratic decline’ (Ginsburg and Huq, Reference Ginsburg and Huq2019: 2), especially where it is not countered by a strong liberal opposition (Chesterley and Roberti, Reference Chesterley and Roberti2018; Ginsburg and Huq, Reference Ginsburg and Huq2019: 86–90; Pappas, Reference Pappas2019a). On the other hand, more optimistic accounts indicate that populism may act as a partial corrective and revitalize mass participation in democratic politics. Rather than representing a threat, a populist shift in the model of democracy may put an accent on vertical responsiveness at the expense of horizontal responsibility (Canovan, Reference Canovan1999: 10-15; Caramani, Reference Caramani2017; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde, Rovira Kaltwasser, Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2012b).

The existing empirical evidence for these diverging claims is diffuse. Some of it draws on developments from single countries or comparisons among a small number of prominent cases (e.g. Batory, Reference Batory2016; Chesterley and Roberti, Reference Chesterley and Roberti2018), often instances where countries de-democratize (Levitsky and Ziblatt, Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018). While instructive, this makes it difficult to assess whether these patterns generalize. At the same time, existing quantitative assessments come to remarkably diverging conclusions. These range from strong positive effects for populists confined to the opposition (Huber and Schimpf, Reference Huber and Schimpf2016b) to more pessimistic assessments, especially as regards populists holding executive office (Huber and Schimpf, Reference Huber and Schimpf2016a; Houle and Kenny, Reference Houle and Kenny2018; Kenny, Reference Kenny2019). Even very similar analytical procedures yield highly diverging conclusions, as regards the populist effect on democratic participation (positive according to Huber and Ruth, Reference Huber and Ruth2017; neutral or negative according to Houle and Kenny, Reference Houle and Kenny2018). Critically, this may be due to ideological differences between the populists analyzed (Huber and Ruth, Reference Huber and Ruth2017), or the variable institutional contexts in which these operate (Mudde, 2012:215-216), both of which strongly cluster within world regions (Europe and Latin America) and correlate with the degree of democratic consolidation (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde, Rovira Kaltwasser, Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2012b; Huber and Schimpf, Reference Huber and Schimpf2016b).

In light of these diverging arguments and findings, we revisit the effects of populism on the Quality of Democracy with a new analytical framework. We follow claims that the differential effects of populism can be located ‘in tensions at the heart of democracy’ (Canovan, Reference Canovan1999: 2). Building on this, our model emphasizes the multi-dimensional nature of the Quality of Democracy. This is characterized by multiple democratic functions and by inevitable trade-offs between these (Dahl, Reference Dahl1956; Bochsler and Kriesi, Reference Bochsler, Kriesi, Kriesi, Lavenex, Esser, Matthes, Bühlmann and Bochsler2013). Conceptually, this distinguishes between multiple possible models of democracy but does not recognize a single ‘high-quality’ democracy. By employing this multidimensional concept, we are able to formulate detailed expectations accruing under both prominent views on populism and to go beyond their ramifications for specific indicators: Does populism pose a systematic threat to central functions of democracy? Or is it a corrective, whereby it reinvigorates some democratic functions at the expense of others?

Our framework further enables us to attribute the multi-faceted impacts of populism on different democratic qualities to specific actors. In particular, we distinguish both between populists in opposition and in government, as well as between populists holding different ideological orientations. While the former distinction has been highlighted before (Huber and Schimpf, Reference Huber and Schimpf2016b, Reference Huber and Schimpf2016a), it has so far not been systematically linked with different democratic qualities in a disaggregated manner. As regards the latter, there is a strong call to ‘study populism not in isolation, but rather in combination with different ideologies’ (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2018b: 1670). This has been previously discussed for specific democratic measures (Huber and Schimpf, Reference Huber and Schimpf2017). However, an approach that accounts for how the ideological ‘colouring’ of populism systematically translates into different models of democracy has, to our knowledge, not been applied before.

By investigating our expectations in a systematic, cross-regional manner, we also contribute to the empirical literature on populism. To date, there is no systematic study on populism which comprehensively accounts for trade-offs between different democratic functions, while simultaneously considering their relation to different types of populist actors. The closest to our study is Houle and Kenny (Reference Houle and Kenny2018), who assess such trade-offs in Latin America, but thereby study mostly left-wing populists in weakly consolidated democracies. A second related study by Huber and Schimpf (Reference Huber and Schimpf2017) differentiates between left- and right-wing populists and their diverging impact on minority rights and mutual constraints. However, it abstains from conducting a more encompassing analysis of different democratic functions and is again exclusively concerned with one region (Europe). Other comparative studies on populism do not systematically distinguish between different functions of democracy (Huber and Schimpf, Reference Huber and Schimpf2016a) or consider specific but isolated components, for example, issue congruence, popular participation (Huber and Ruth, Reference Huber and Ruth2017), press freedom (Kenny, Reference Kenny2019), or support for democracy (Remmer, Reference Remmer2012). These make it difficult to judge whether the attained effects translate into a distinct model of populist democracy.

To obtain sufficient empirical variance for our differentiated expectations, we employ the largest currently available data collection on populism and the Quality of Democracy. We analyse 53 countries from four world regions during the time period between 1990 and 2016. This enables us to differentiate between democratic effects of populism as moderated by host ideology, institutional position (government or opposition), and electoral strength. Our dependent variable, the Democracy Barometer (DB), closely corresponds to our multidimensional concept of the Quality of Democracy. Its 105 objective indicators are associated with the same nine functions of democracy which we use in our theoretical discussion. While there is no single data source available to identify populist parties across such a large number of cases, we innovate by combining existing sources that conceive of populism as an ideational or a discursive concept (Mudde, Reference Mudde2004). We convert these measures to a single scale and perform multiple tests to make sure that our results are not driven by heterogeneous measures across cases. We further employ country-fixed effects to account for time-invariant inter-country differences. This enables us to attain findings robust to different settings and to a wide range of confounding factors, including political institutions.

Our results indicate a considerable divergence in the democratic effects of populism, depending both on the aspect of democratic quality studied and on specific actor types. We find that left-wing populism enhances representation. Furthermore, left-wing (and, more sensitive to the chosen specification, also right-wing) populists appear to exert mobilizational effects on previously demobilized parts of the population, while centrist populists lack such impacts. However, populists across the ideological spectrum, both in government and opposition, appear to erode institutional safeguards, most notably the rule of law and state transparency. Populists in power are furthermore associated with a deterioration of the public sphere in which democratic institutions are embedded.

The rest of the article proceeds as follows: the next section starts by presenting two contrary views on the effects of populists on democratic quality. Building on these arguments, it then discusses the variable impact of populists depending on their institutional position and host ideology. It formulates a set of hypotheses about the populist effect on nine dimensions of the quality of democracy. We then present our operationalization and our new data, and use them to investigate the effect of populist parties on democratic quality in a series of disaggregated regression models. Our final section concludes and discusses the ramifications of our findings.

The populist effect on democratic quality: two contrary views

“There are no institutions. Only the people rule.”

Papandreou at PASOK rally (cited in Pappas, Reference Pappas2019b: 73)

In our theoretical framework, we introduce two prominent views in the literature of the populist effect on the quality of democracy. A first set of scholars sees populism as a threat that exerts detrimental impacts on the fundament of democracy. In contrast, a second view identifies populist democracy as a specific type of democracy, which prioritizes direct popular control over politics, even if this weakens the protections of individual citizens. To account for the arguments of the latter view, we do not a priori distinguish between ‘low’ vs. ‘high’ overall quality of democracy. Rather, we understand the quality of democracy as a multidimensional concept, which makes explicit that its different functions are in continual tension with each other.

In what follows, we analyse the two contrary views to derive hypotheses on how populism affects the quality of democracy. We rely on our multidimensional framework to systematically differentiate between populism’s variable impact on its underlying functions. We then further refine our argument by attributing these potentially diverging effects to different actor types, differentiating between populist actors in government and opposition and by their host ideology.

The Quality of Democracy and the populist effect

To identify potential ‘tensions’ or ‘trade-offs’ between real-existing democracies and the populist ideal, we rely on a multidimensional concept of the Quality of Democracy (Merkel, Reference Merkel2004; Diamond and Morlino, Reference Diamond and Morlino2004). We use a mid-range concept that goes beyond the electoral principle and also incorporates further liberal democratic principles. We distinguish between nine functions of democracy, split into three groups: the first group refers to institutions of popular control and decision-making. These make the government responsive to citizens’ preferences (vertical accountability) and determine the inclusiveness of this process. Ideally, they allow for broad-based participation and for elected governments to effectively implement their electoral pledges. They are embedded in a second group of functions, comprising of the liberal protections of citizens’ rights against the excessive accumulation of power by elected officials. This includes institutions and practices allowing for a free political debate, checks, and balances to limit the power of governments, civil rights, the rule of law, and the transparency of the state action. Finally, a third group addresses the intermediaries between political institutions, civil society, and the wider public sphere, determining the quality of their interrelationships. The three groups of functions of democracy are related to the key trade-offs entailed in the model of populist democracy.

The populist view of democracy is related to our notion of populism: we define populism as a thin-centred ideology, which rejects democratic pluralism (cf. Mudde, Reference Mudde2004). Instead, populists see themselves as representatives of the ‘pure people’ and as antagonists of the ‘corrupt elite’. In their view, legitimate politics is an expression of the volonté générale (Abt and Rummens, Reference Abt and Rummens2007). Populists are united by this thin ideology, although they combine it with different specific host ideologies.

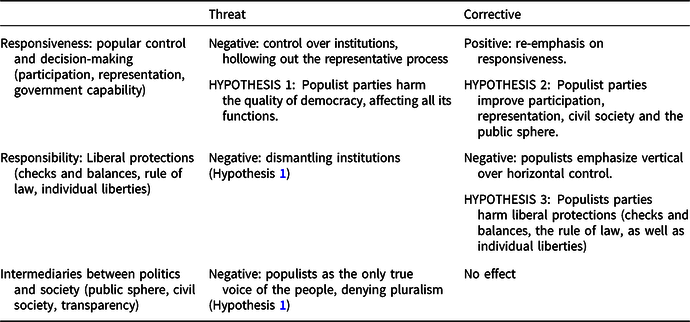

Some scholars characterize this populist vision of democracy as inherently anti-democratic. They perceive a twofold populist threat to democracy: first, thin-centred populist ideology rejects the notion of a pluralist society which is the basis of liberal, representative democracy (Abt and Rummens, Reference Abt and Rummens2007; Urbinati, Reference Urbinati, Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2018a: 18). This monolithic view of democracy makes intermediaries between the people and politics obsolete. Instead, populist leaders act ‘as the spokesperson of the vox populi’ (Kriesi, Reference Kriesi2014: 363), while villainizing other intermediaries – including the media sector, civil society, or established political parties – as serving the interests of the established elite, rather than the people (Ginsburg and Huq, Reference Ginsburg and Huq2019: 86–90; Mair, Reference Mair, Mény and Surel2002). Thus, populists bypass traditional intermediaries, such as an independent civil society or critical media, or bring them under their control.Footnote 1 Second, the lack of a long-term perspective of populist economic policies pushes them to take illegitimate measures to secure their re-election (Chesterley and Roberti, Reference Chesterley and Roberti2018). Accordingly, populism risks damaging all three groups of democratic functions. Table 1 summarizes the three groups of functions of the Quality of Democracy and reports the hypothesis related to this view in the second column.

Table 1. Populist threat or corrective, and the quality of democracy (hypotheses)

The second view, addressing populism as a corrective, builds on a multidimensional model of democracy, postulating trade-offs between its different functions. According to scholars holding this view, populist actors are inherently democratic, emphasizing majoritarian views of popular representation and endorsing direct, plebiscitary decision-making (Taggart, Reference Taggart, Mény and Surel2002; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2018a: 15-18; Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Rovira Kaltwasser2012). However, there is an inherent tension between two democratic functions: popular control and liberal protections. The latter have taken a major place in real-existing democracies – according to the populist view excessive place – at the cost of constraining the will of the people (Canovan, Reference Canovan1999: 7–8; Mény and Surel, Reference Mény and Surel2002b; Taggart, Reference Taggart, Mény and Surel2002). Consequently, populists campaign on issues otherwise neglected by mainstream parties (Mény and Surel, Reference Mény, Surel, Mény and Surel2002a; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde, Rovira Kaltwasser, Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2012a: 18; Roberts, Reference Roberts, Mudde and Kaltwasser2012: 147–153). Vice versa, liberal rights regimes entail complex judicial procedures and might hollow out popular rule. For instance, for Laclau (Reference Laclau2005: 171), liberal rights are not a core function of democracy, which he defines solely as electoral or plebiscitary. Instead, liberal rights are subject to democratic choice: ‘at some points in time […] the defence of human rights and civil liberties can become the most pressing popular demands’. Hence, according to this view, we would expect populism to boost the inclusiveness of the political process and emphasize popular control at the expense of liberal protections (see the third column in Table 1 for related hypotheses).

In sum, the two views, presenting populism either as a threat or as a corrective, share similar expectations about the deterioration of liberal rights and freedom. However, while the first view expects a deterioration of democratic representation and the public sphere, the latter expects that populism mobilizes previously excluded sectors of society, and thereby improves participation and representation.

The influence of populist actors over government policy

Having laid out the contrary expectations of the two prominent views on populism, we now proceed to refine our hypotheses with respect to specific actor types. In a first step, we argue that the hypothesized effects under both views are moderated by whether populists attain influence over government policy or remain confined to the opposition. In particular, the ability of populists to erode the Quality of Democracy (according to the view of populism as a threat) or its underlying liberal rights and freedoms (acknowledged in the view of populism as a corrective) is moderated by government access. Executive power allows populists to implement their perceived mandate and fight institutional safeguards (Müller, Reference Müller2016: 45–48; Müller, Reference Müller, Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017: 602–603; Abt and Rummens, Reference Abt and Rummens2007; Taggart, Reference Taggart, Mény and Surel2002; Huber and Schimpf, Reference Huber and Schimpf2016b; Houle and Kenny, Reference Houle and Kenny2018). Populists in government are also able to use their powers to infringe on the de facto autonomy of formerly independent institutions such as the judiciary, the civil service, public media, and civil society (Kenny, Reference Kenny2019; Houle and Kenny, Reference Houle and Kenny2018). According to empirical accounts (Abou-Chadi and Krause Reference Abou-Chadi and Krauseforthcoming; van Spanje Reference van Spanje2010), populists in opposition may exert similar effects, through indirect processes of ‘contagion’ affecting mainstream political parties. However, such contagion effects should be less pronounced than the effect of populists holding executive office themselves.

Conversely, government inclusion is less likely to decisively shape the mobilizing role of populists for previously excluded parts of the population (emphasized in the view of populists as a corrective). However, while populists in opposition might mobilize previously excluded groups and thus contribute to a more plural public sphere, populist governments are likely to actively engineer a public sphere that is favorable to their re-election (Pappas, Reference Pappas2019b).

Overall, the degree to which populists are able to threaten liberal rights and freedoms depends on their influence over policy. Similarly, potentially corrective effects on the core representative functions of democracy might also come at the cost of increasing harm to the public sphere as populists move from opposition to government. Following these considerations, we formulate two further hypotheses:

HYPOTHESIS 4: If populist parties gain executive power, they harm liberal protections and government transparency.

HYPOTHESIS 5: If populist parties gain executive power, they harm the public sphere.

The host ideology of populism

In a second step, we refine our expectations according to the host ideology of populist actors, or how populists define the ‘people’ according to their different ‘thick’ ideological underpinnings (Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Rovira Kaltwasser2012).

Left-wing populists frequently rely on a notion of the ‘people’ in terms of socio-economic status or are associated with emancipatory movements. Left-wing populists address and mobilize, depending on the specific setting, either the ‘working class’ or indigenous people (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2013). As a result, left-wing populists are especially likely to improve broad-based representation and participation of previously excluded groups. This effect is likely also to extend to non-institutionalized forms of participation, thereby revitalizing social movements and the public sphere (March, Reference March2011).

In contrast, populists with an authoritarian-nationalist thick ideology, often addressed as right-wing populists, build on a more exclusionary view of the people. They typically conceive of them as the marginalized ‘homeland’ defined in genealogical terms, which they contrast with globalized elites, sometimes characterized as ‘citizens of nowhere’, immigrants, or ethnic minorities. Their exclusionary notion of the ‘people’, and their sometimes negative, often more divisive campaigning may furthermore increase overall political disenchantment and demobilize parts of the electorate (Immerzeel and Pickup, Reference Immerzeel and Pickup2015). This may also destigmatize exclusionary practices, facilitating the erosion of liberal rights and damaging the public sphere (Urbinati, Reference Urbinati1998; Huber and Schimpf, Reference Huber and Schimpf2016b; Houle and Kenny, Reference Houle and Kenny2018).

Following increasing calls in the literature to include, apart from polar types, also ‘valence-types’ of populism (Zulianello, Reference Zulianello2020), we discuss this centrist type of populism. Centrist populists avoid strong ideological stances or reinforce ideologies already represented in the political mainstream (Hanley and Sikk, Reference Hanley and Sikk2016; Stanley, Reference Stanley, Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017). Owing to this, they seem comparably ill suited to have strong mobilizing effects. Hence, they are unlikely to engender a comparably inclusive participation and representation as their left- and right-wing variants do. Following these considerations, we formulate a final set of hypotheses:

HYPOTHESIS 6a: Populist left-wing parties strongly improve the quality of representation, compared to populist parties with other ideological orientations.

HYPOTHESIS 6b: Populist right-wing parties harm the quality of representation.

HYPOTHESIS 6c: Populist left- and right-wing parties improve the quality of participation, whereas no such effect exists for centrist ones.

HYPOTHESIS 7: Populist right-wing parties strongly harm civil rights protections and the public sphere, compared to populist parties with other ideological orientations.

HYPOTHESIS 8: Left-wing populist parties improve the public sphere and civil society.

Investigating the relationship between populist power access and different democratic qualities

Having formulated our theoretical expectations, we now proceed to investigate them empirically. To set up our analysis, we first operationalize the key concepts that underlie our arguments: the Quality of Democracy, populist actors, and their ideological position. In a second step, we systematically investigate our hypotheses on their interrelationships in a cross-regional, quantitative setup.

Operationalization: Quality of Democracy, populist parties, and ideological stance

This article relies on a new data collection, which massively expands the geographic scope of previous studies on the populist effects on the Quality of Democracy. It also employs a multi-dimensional operationalization of the Quality of Democracy, which closely corresponds to the afore-mentioned nine functions thereof. Our hypotheses highlight multiple moderating factors of the democratic effect of populism. They further point to gradual changes induced by populist actors on some of the functions of democracy and are thus optimally investigated with fine-grained measures.

The DB mirrors our concept and provides gradual measures for theoretically selected and disaggregated democratic qualities. The DB builds on a total of 105 indicators grouped into nine primary functions of democracy (and is based on the same concept of democratic quality that we operated with in the last section): competition, participation, representation, governmental capability, individual liberties, rule of law, mutual constraints, transparency, and the public sphere. It is currently available for a total of 70 democracies worldwide, with an established status in the 1990s, and covers the period of 1990 to 2016 (Merkel et al., Reference Merkel, Bochsler, Bousbah, Buhlmann, Giebler and Hänni2018).

A key empirical challenge is our moderating factors, which might crucially shape the diverging democratic effects of populism. For our quantitative setup, a sufficiently large number of cases is essential to account for these contextual variables. Considering the spatial clustering of these factors (in particular, of host ideology), limiting ourselves to a particular world region would risk bias. Our new data collection squarely addresses these issues by providing for the most comprehensive classification for populist actors across four world regions (Western Europe, Central and Eastern Europe, North America, and Latin America). It covers different prevailing host ideologies of populism and diverse institutional contexts for 53 countries during the period between 1990 and 2016.Footnote 2

We compile our data on populist actors by combining information from multiple existing sources. Specifically, we cover all parliamentary parties with at least 2% seat shares (lower chamber). To make sure that the information from multiple sources is comparable, we proceed as follows: first, we only include measures that identify populism based on a thin, ideational concept, in line with Mudde (Reference Mudde2004).Footnote 3 Second, we conduct empirical tests, based on the pairwise overlaps of these measures, which show that they consider the same concept, with some limits. Third, we convert all source measures of populism to a dichotomous scale (already employed by Huber and Schimpf, 2016a, Reference Huber and Schimpf2016b; Mudde, Reference Mudde2011; March, Reference March2011; Kessel, Reference van Kessel2015), using a cut-off point (Hawkins, Reference Hawkins2009; Hawkins, Reference Hawkins2013; Hawkins and Castanho Silva, Reference Hawkins and Castanho Silva2016).Footnote 4 Fourth, to consider the limits of comparability, we also construct a second, more limited measure containing only the most similar classifications, which we use as a robustness check.

In addition, we also collected information on each party’s ideology, in particular on its position on the left–right scale. Again, we combine information from multiple sources which we manually connect by name to the parties in our data. This results in a time-invariant measure for each party ranging from −1 (extreme left), over 0 (centre), and to 1 (extreme right).Footnote 5 We provide details on our party-level coding of both populist status and ideology as well as the full resulting data in our supplementary material.

We aggregate the information from individual parties to country-years by calculating the seat shares of populist parties (ranging from 0 to 1), variably disaggregated by host ideology,Footnote 6 institutional status (government or opposition), and country-year. This accounts for annual changes in party composition arising both from general elections as well as from other factors, such as by-elections, changing party allegiances, and shifting government coalitions. Again, our supplementary material provides more detail on this coding procedure.

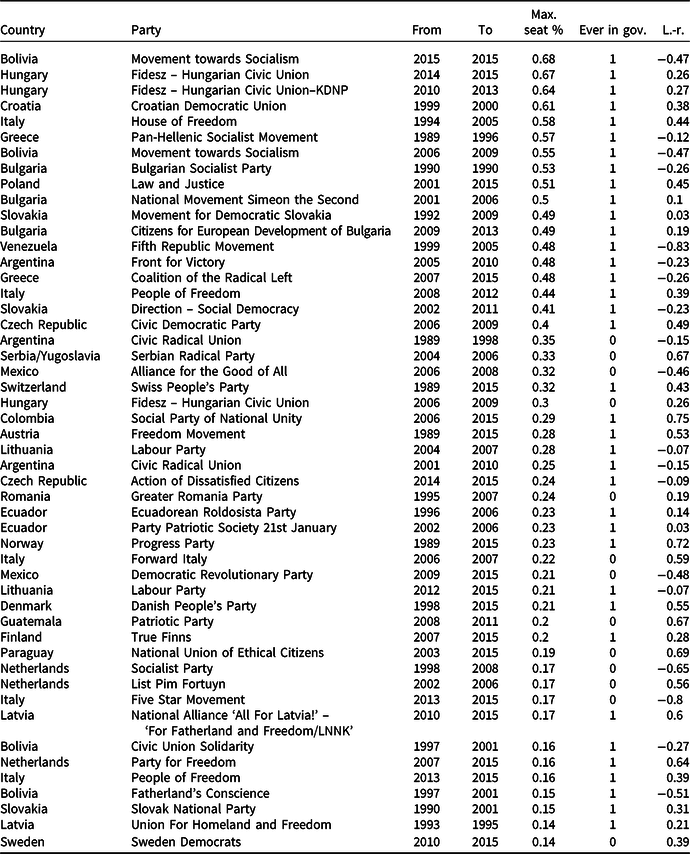

Our measure offers high face validity. Out of a total of 619 parties for which we have complete data, 97 are classified as populist during at least part of their existence. This includes the most prominent populist actors in Latin America (Bolivia’s Movement towards Socialism, Venezuela’s Fifth Republic Movement, and Argentina’s Front for Victory), Eastern Europe (Hungary’s Fidesz and Poland’s Law and Justice party), and Western Europe (Italy’s House of Freedom and the Swiss People’s Party). Table 2 shows an illustrative selection of parties that we classify as populist, chosen by the maximum seat shares they attained during the time period in our sample. It also shows their left–right stance and whether they were ever included in government.

Table 2. Populist parties [selection according to largest ever seat shares]

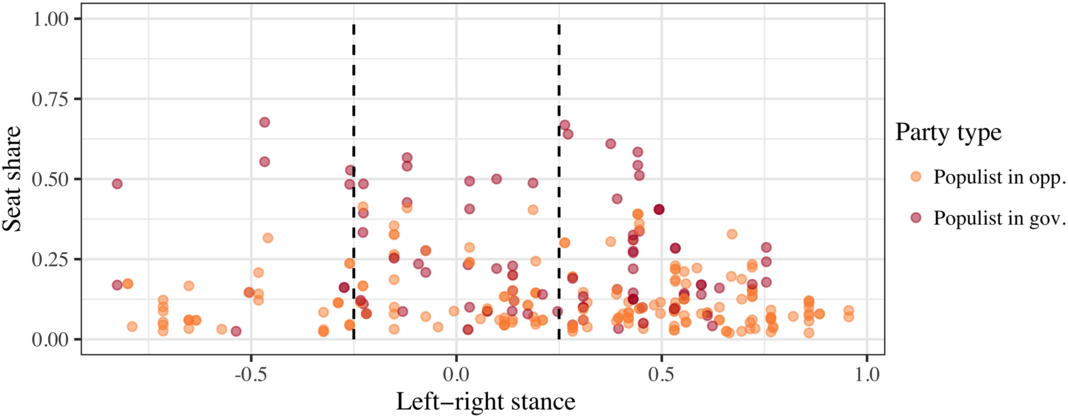

Figure 1 provides a full graphical overview of populist actors in our data (with each dot representing a unique party-period). It shows that our sample encompasses cases of populist parties across the full ideological spectrum and contains large variation in terms of their attained seat shares and government inclusion. However, it also indicates a comparative scarcity of cases where populists on the extreme right (beyond a certain threshold) are included in government (as opposed to those on the extreme left, which, in our sample, are in government quite frequently, especially in Latin American countries).

Figure 1. Distribution of cases by populist seat shares, populist ideology on the left-right spectrum (extreme left = -1, extreme right = 1), and populist inclusion into government. Note: The dotted lines represent the trichotomized version of the ideological variable, into separate dummies for left-, right- and centrist populists.

Our resulting sample covers 1194 country-years, based on 347 unique electoral periods in a cross-continental sample of 53 countries. Non-democratic years (Polity IV < 6) were excluded.Footnote 7

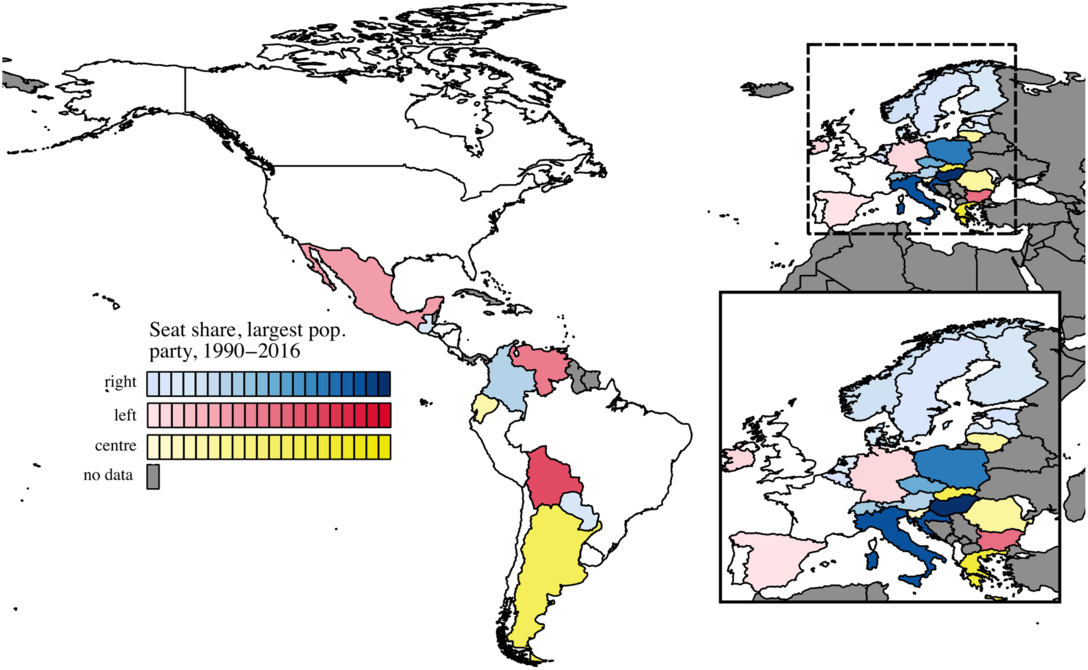

Figure 2 gives a simplified geographical overview of the resulting country-level data underlying our analysis. In particular, it shows both the strength and ideological ‘colours’ of each country’s largest populist party in the time period for which we have data. It indicates a substantial variation in both. Furthermore, it also echoes our afore-mentioned concerns of spatial clustering of different ideological types of populism, underlining the necessity to study a cross-regional sample. Notably, whereas significant populist actors in Latin America tend to be left-wing, the strongest populists in Europe are generally on the right side of the political spectrum. In the Balkans, they appear to be situated more in the ideological centre. Clearly, these differences correlate with factors about which we need to be concerned in our analysis. They thus indicate the need to control for stable inter-country and regional differences, for example, different standards in development, institutions, or socio-economic structures.

Figure 2. Seat shares and ideological type of largest populist party in our sample, 1990–2016. Note: Mapped values based on maximum values in our non-exhaustive sample of years across the time period used.

Modelling approach

Using these combined data sources, we now turn to a series of regression analyses that test our expectations. Our dependent variables are the nine functions of the Quality of Democracy taken from the DB (see above). Our key independent variables are the seat shares of different types of populist actors: those of the left, centre, and right. In addition, we also include a variable measuring the overall seat shares of populist actors in government to account for its hypothesized conditioning role across the spectrum.Footnote 8 To hold apart the impacts arising from populists from those of the broader party system (for example, left-wing populists vs. an overall left-wing party system), we control for the analogous seat share variables of the overall parliament composition in all of our specifications.Footnote 9

To estimate the effects of populist actors on democratic quality, we rely on an ordinary least squares setup. To account for persistent differences between different countries that might influence both the baseline Quality of Democracy as well as the electoral prospects of different types of populist actors, we include country-fixed effects in all our specifications. For instance, this allows us to control for factors underlying the disproportionate occurrence of right-wing populists in democratically more established states in Western Europe. To further alleviate the potential for reverse causation (with the populist vote being the result of specific changes in democratic qualities over time), all of our independent and control variables are lagged by 1 year.Footnote 10

In addition, we include a series of time-variant controls in all our models: First, we control for democratic consolidation (Huber and Schimpf, Reference Huber and Schimpf2016b) by including a term for regime durability based on Polity IV data (Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Gurr and Jaggers2019). Second, we control for the potentially negative effect of economic downturns on the quality of democracy (Armingeon and Guthmann, Reference Armingeon and Guthmann2014) by including a term for GDP per capita.Footnote 11 Third, we control for the region-specific role of EU accession talks (Börzel and Schimmelfennig Reference Börzel and Schimmelfennig2017), which systematically fostered democratic developments and limited populist influence in several countries we study (most notably, in Eastern Europe) as shown by Batory (Reference Batory2016) and Bochsler and Juon (Reference Bochsler and Juon2020). In addition, we include a year variable to account for linear time trends and a post-2008 dummy to account for the potential shock on both democratic quality and populist actors’ electoral chances following the 2008 financial crisis.

Empirical analysis

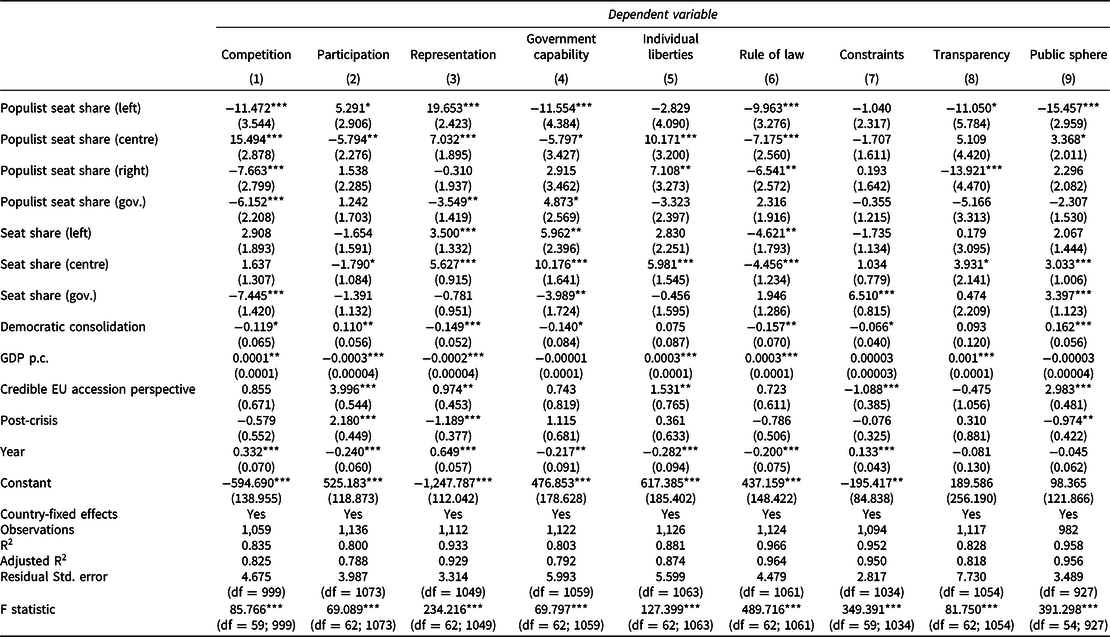

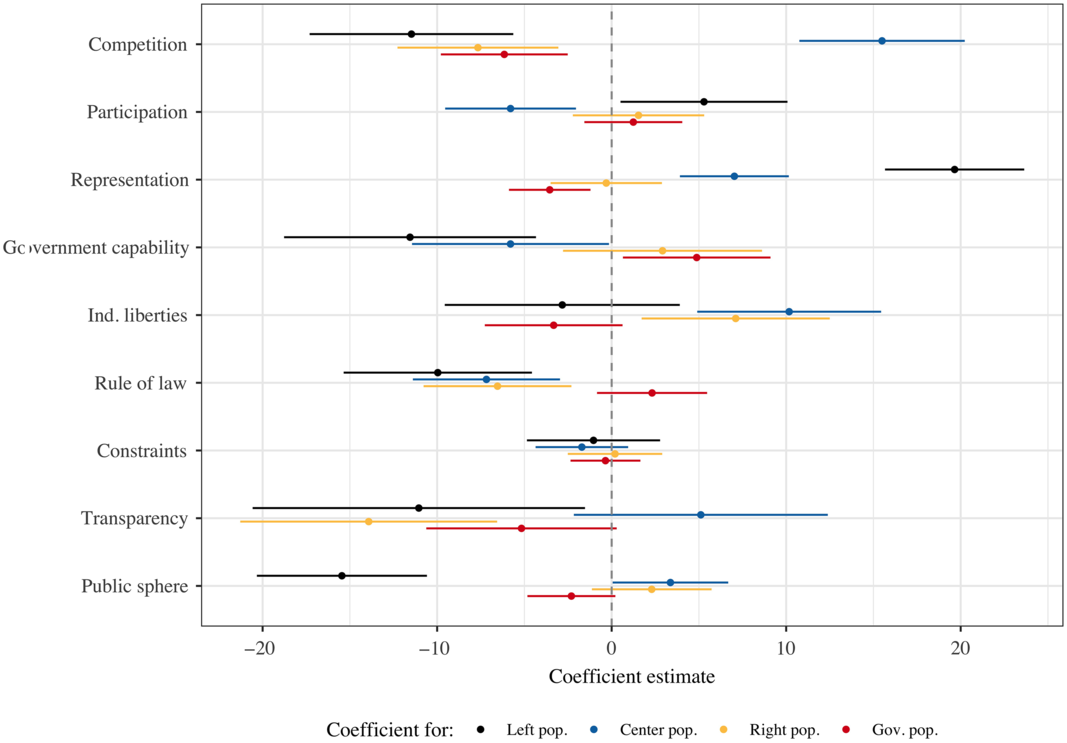

Table 3 reports the findings from our main specification, which models the impacts of combined seat shares of different types of populist actors. Figure 3 plots the coefficients of our main independent variables and their 90% confidence interval. Overall, our results are in accordance with the arguments underlying the view that populism is a partial corrective for democratic deficiencies. In particular, as expected by both views on populism, we find that populists across the ideological spectrum exert negative impacts on several democratic qualities belonging to our second layer of liberal rights and safeguards. Most notably, this relates to the rule of law and transparency, both of which appear to be reduced by populists across the ideological spectrum (the latter with the exception of centrist populists). Indicator-level checks (reported in the supplementary material) indicate that these negative impacts are mostly due to infringements of judicial independence and guarantees for neutral process, press freedoms, and disclosure rules for financial contributions to political parties.

Table 3. Model 1: populist party strength (left–centre–right), government inclusion, and components of the quality of democracy

Note: *P < 0.1; **P < 0.05; ***P < 0.01.

Figure 3. Effects of populist measures on components of democratic quality and 90% confidence interval.

However, corresponding to the view of populism as a corrective (and not to the one of populism as a threat), we also find that populists exert beneficial impacts on aspects belonging to our first layer of democratic control, although these are not uniform between different actors. Most notably, we find that populists of the left improve both participation and representation, while those of the centre also exert a beneficial effect on representation, which indicates at least a partial, if contingent, corrective role of populism. Other results are more difficult to reconcile with either of the two views – for instance, we find a rather positive impact of populist actors on individual liberties (except, surprisingly, for those belonging to the left) and mixed effects on competition. We interpret these findings as partial evidence in line with our Hypotheses 2 and 3 (and against Hypothesis 1).

The results further offer mixed support for our argument that, to trace the democratic effect of populists, a differentiation is required between populists in government and opposition and between those belonging to the left, centre, and right of the ideological spectrum. As concerns the former, while we find no significant difference between populists in government and opposition for their impacts on our second layer (individual liberties, rule of law, constraints, and transparency), the signs generally point to a negative association. The same applies to our expectation that populist actors in government are especially likely to lead to a deterioration in the public sphere. We view this as evidence that is overall in accordance with but insufficient for our Hypotheses 4 and 5.

As concerns populists’ ideological orientation, our findings are generally in line with the argument that the way populists construct the ‘people’ matters for their effects on our first, representative layer of democracy. As expected, we find that left-wing populists have the strongest positive impact on participation and representation (Hypothesis 6a) and that centrist populists do not have a positive impact on participation in contrast to those of the ideological wings (Hypothesis 6c). However, we find no evidence for the detrimental effects of right-wing populists on representation (Hypothesis 6b). In line with our arguments, our complementary indicator-level analysis reveals additional support that these results are indeed driven by particular conceptions of the ‘people’ held by different populist actors: left-wing populists are particularly strong promoters of the inclusion of ethnic minorities, whereas right-wing populists are associated with a decreased representation of women. However, we attain no evidence that right-wing populists are especially likely to engender infringements on individual liberties and minority rights or deteriorations in the public sphere, which is against our Hypothesis 7. Similarly, we find no evidence that left-wing populists should be favourably associated with individual liberties and the public sphere (Hypothesis 8). On the contrary, our results indicate a strong negative effect of left-wing populists on the latter, driven by infringements on constitutional freedoms of association, assembly, speech, and effective freedom of the press.

Robustness checks

In addition to our main specifications, we also conducted further checks to assess the robustness of our results (all reported in our supplementary material). We address four main potential issues. First, the distinction of left-wing, centrist, and right-wing populists requires a trichotomization of the left–right axis. Consequently, the chosen cut-off points might affect our findings related to the role of the host ideology. For example, our classification leads Christina Kirchner’s Front for Victory to be classified as centrist, although a different trichotomization might classify it as left-wing populist. Hence, we re-ran all our models with alternative thresholds. While our results do show minimal shifts in coefficients, which are to be expected, the substantial differences between ideological subtypes do not change. This enhances our confidence that the particular value of the chosen thresholds does not drive our findings.

To test the effect of ideology without a sharp classification into categories, we additionally re-ran all our analyses with a continuous measure of populist ideology, as well as its quadratic term.Footnote 12 This alternative approach requires us to exclusively rely on variation induced by the largest populist party in a given country-year and to ignore the impacts of smaller populist parties that might be active in the same period. We predicted and visualized this specification’s outcomes of all democratic qualities in our concept (see Figure 4).Footnote 13 The results of this alternative setup are in accordance with the findings from our main specification (full results in the supplementary material). It shows the negative impact of populists on the second and third layers of democratic quality as well as their partly corrective effect on the first layer (especially participation and representation). Analogous to our main specification, it also indicates that the negative impact of populists on the public sphere (but not liberal rights and safeguards) is exacerbated if they attain government inclusion. In addition, it visualizes the stronger mobilizational impact of populists of the ideological fringe (participation) and the stronger inclusive impact of populists on the left (representation).

Figure 4. Predicted democratic outcomes, depending on seat shares of largest populist party, its government inclusion, and its left-right stance [model 2 in supplementary material].

Second, the distinction between left-, centrist, and right-wing populism is strongly related to ideological differences and specific roles of populists in different regions. Left-wing populist governments are particularly frequent in Latin America, whereas centrist and right-wing populists are more frequent in Europe. To test the potential of spatial clustering to distort our analyses in spite of our use of country-fixed effects, we split up our sample and re-run our main models for two regions separately: Latin America on the one hand and all European countries on the other. While we are unable to distinguish between populists by their role or ideology for the Latin American sample (due to low variance), the attained results from the European sample are largely consistent with those from our pooled specification, thus indicating that our findings are not driven by regional clustering.

Third, we are also concerned about our combination of different measures of populism, with sometimes different underlying definitions (see above). To test the robustness of our findings to a more coherent, but also slightly more limited, measure, we consequently constructed an alternative measure of populism that discards sources that either (1) rely on a discursive concept or (2) exclusively code populist parties from one ideological side or the other. This left us with three sources – Huber and Schimpf (2016a, Reference Huber and Schimpf2016b) and Kessel (Reference van Kessel2015) – which we combined into a more limited populism measure. We re-ran all our models with this alternative measure and could not find any systematic differences to our main specifications. This reassures us that our findings are not biased by potentially diverging classifications of populism either.

Finally, we are concerned with possible reverse effects, whereby the pre-existing quality of democracy might drive the subsequent electoral success of particular types of populist parties. We address this in our modelling approach by including fixed effects at the country level and by operating with time-lagged explanatory variables. Thus, our analysis predominantly captures temporal changes in the quality of democracy following populist rule and not viceversa, while excluding selection effects arising from stable inter-country differences. To check the potential for left-over bias, in Appendix 5 in our supplementary material, we report a series of placebo tests, in which we invert our main independent and dependent variables. We find that populist parties are more likely to receive higher vote shares in periods with a lower quality of representation and participation, and right-wing populists in periods with lower values of the rule of law and transparency. While we consequently cannot rule out partial reverse effects as regards the influence of right-wing populists on our second layer of democratic quality, we do not find systematic troubling relationships as regards other aspects or actors.

In addition to these main concerns, we also checked the robustness of our findings for several other aspects. First, we estimated specifications with additional controls, including Presidential executives, proportional electoral systems,Footnote 14 net migration as a percentage of the total population, dependency on oil exports, and economic inequality given by the GINI index.Footnote 15 Second, we estimated alternative specifications for our main modelling approaches. These include a modification to model 1 that relies on six separate categorical terms for populist actors (left-wing populists in government, left-wing populists in opposition, and so on) and a version of model 2 that contains a cubic interaction term between populism and ideology. Substantively, our results remain the same. Third, we are concerned over potential bias induced by left-over serial correlation of errors (see footnote 10). We hence conducted a Prais–Winsten transformation of our main specification that is robust for serial correlation (Plümper et al., Reference Plümper, Troeger and Manow2005). These models offer further support for our main findings as regards the first (representation and participation) and third layers (public sphere). While the coefficients for the second layer point in the same direction, their significance is reduced, thus indicating less robustness as regards these results.

Conclusion

This article provides to our knowledge the most comprehensive study of the populist effect on the Quality of Democracy in the period since the Cold War. It is comprehensive for three reasons: first, it offers significantly enhanced scope compared to previous studies, covering 53 countries from three world regions. This enables us to rely on an encompassing sample of populist actors, whose ideological sub-types often cluster by region, institutional context, and degree of democratic consolidation. Second, in recognition of the significant tensions that exist between multiple dimensions of the Quality of Democracy, it maps the effect of populist parties on nine functions of democracy, which jointly offer a comprehensive picture of the Quality of Democracy. This allows us to assess whether populism indeed translates into broader patterns that go beyond isolated impacts on specific outcomes, such as vote turnout. Third, it responds to calls to distinguish populist parties by their host ideology and access to government office. Thereby, we are able not only to consider overall populist impacts but also attribute these to specific actors.

According to our measures, which are primarily based on objective indicators, we identify a populist threat to some institutions of liberal democracy. We find consistent and significant impairments of judicial independence and of guarantees for neutral process, press freedoms, and disclosure rules for financial contributions to political parties, where populist parties are in power.

Further, our findings are generally in line with the view that populism can be a partial corrective to specific democratic short-comings (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde, Rovira Kaltwasser, Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2012b), leading to trade-offs between different aspects of democratic quality. However, this is partly mediated by their specific construction of the ‘people’ they purport to speak for. Populists of the left have the potential to improve the participation of previously marginalized or demobilized societal strata. Left-wing and centrist populist parties exert positive effects on the quality of representation, in particular owing to increased representation of women and ethnic minorities.

Apart from these systematic trends, the populist effects on the Quality of Democracy differ widely between the countries under study; among others, we observe very different trajectories of the public sphere under populist rule in the countries under study. Our results are also more mixed as regards the expected conditioning role of populists’ government inclusion. This goes against previous findings on the detrimental role of populists in government (Huber and Schimpf, Reference Huber and Schimpf2016b, Reference Huber and Schimpf2016a). This may indicate that, even when confined to the opposition, significant populist actors may be able to shape policy indirectly by influencing the positions of government parties and possibly tilting them towards a more unrestrained style of ruling that is opposed to institutional constraints.

Our findings are evidently not the last word on the question of how populist actors shape democratic quality. While our approach shows the benefits of disaggregating between different dimensions of the Quality of Democracy and different types of populist actors, our findings also indicate a need for future research to trace these heterogeneous, and possibly partly indirect, impacts of populism in a more fine-grained manner. This could include variance from world regions outside of Europe and the Americas and over more extensive time periods than those which we have been able to include in our analysis. It might additionally involve a further disaggregation by ideology, such as the heterogeneous category of right-wing populists (Zulianello, Reference Zulianello2020). For now, we conclude that populist actors exert diverging impact on different layers of democratic quality, which are partly mediated by their specific construction of the ‘people’ they purport to speak for.

Acknowledgement

Research was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (NCCR Democracy) and the Centre for Democracy Studies Aarau (ZDA).

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773920000259.