This article covers social network scenarios and provides a selection of images exposing the tools used to recruit women into terrorist activities. It will be focused on four main patterns of recruiting: role models, copy-cats, “the sister” and “alimah.”

Women joining “Islamic State in Iraq and Syria” (ISIS) mujahedin and terrorist activity in general should not be considered as trapped by wrong-minded ISIS men, but rather as Boudicca and Jeanne d’Arc as women leading military campaigns and Shirin Ebadi and Benazir Bhutto as women leading political changes. It is not impossible that a woman would initiate, plan and execute the operation, be it political or military (DeVries Reference DeVries2017). Islamist radicalized women have proved to be explicitly operative and effective in military and suicidal attacks. For example, the deadly attack on the Westgate mall in Nairobi was planned and executed by the British Muslim convert, the “Black Widow,” while “black Chechen widows” (martyrs) planned and executed numerous attacks in Russia.

Coordination and execution of these attacks was not possible without telecommunication and social networks. Social text, video and audio media play significant role in the terror game. It is important to state that the history of terror does not begin with the invention of Facebook. Terrorists worldwide found other means of communication to spread their ideology. It is within these new tools that the message was democratized, popularized, magnified and hastened to demonstrate to the whole world the inhumanity of terrible deeds of subtle militarized groups.

This article will trace the roles that social media play in the creation of different scenarios for the mobilization of women, aimed to involve them more deeply in terrorism activity. Once ISIS or other military groups are in a crisis, they will use women as a powerful resource both on the battlefield and for further mobilization. ISIS women, although initially restrained from military activity, could follow their Yazidi counterparts and fight on the battlefield.

In this sense, one of the crucial means of creating support and further mobilization for terror by ISIS militants is the usage of social networks. The usage of the networks is selective and strategic, from dissemination of general ideas and support, up to covered and encoded messages containing direct instructions for actions. Different types of women would be targeted by different social media strategies, thus maximizing the effect of the reach out of the mobilization attempts.

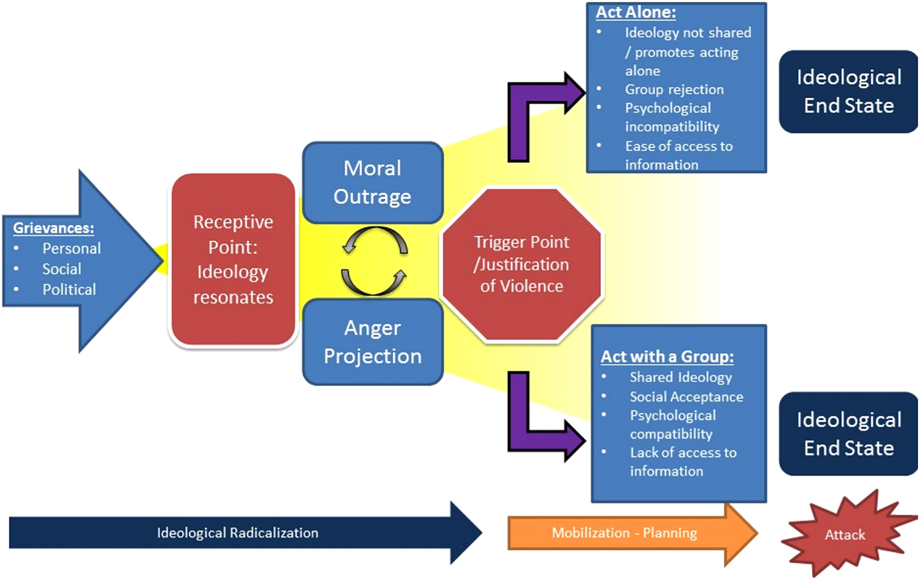

That is why one of the crucial questions here would be how those women, some of them adolescents, have been drawn to the terrorist activity of ISIS? The known facts suggest that there are clear differences in mobilization strategies designed for women coming from Western education against those who grew up in the Muslim (mostly Sunni) world. The first difference will lie in the role that social media play in the process. For the recruitment and mobilization of Western women social media channels are used for gaining support and emotional involvement, describing imagined paradise with real men playing their role and women supporting them. For the women coming from Muslim countries, it is utilized mostly for instrumental guidance and interpersonal contacts toward the aim of coordination. In other words, while Western women should be funneled through the whole process of mobilization beginning at Stage I of Grievances (see Figure 1), women coming from Muslim countries will be funneled directly to the Trigger Point or Act Alone/Act with a Group stage.

Figure 1 Mobilization route. Source: Connor and Flynn (Reference Connor and Flynn2015)

For example, evidence shows that women coming from Asian countries move into the battlefield following personal relations, previous ties and family. As such, women recruiting women in Central Asia states use small intimate cells of womanhood, often hidden from public eyes and aimed at reinforcement of religious beliefs as well as daily guidance and routine (Pikulicka-Wilczewska and Davé Reference Pikulicka-Wilczewska and Davé2017). Western women are recruited using an appeal for adventure and thrill, while also presenting to them the usage of real weapons, attractive commanders and administrative roles. Both groups are attracted by romance, but the first group is about finding the right man and the second is offered an illusion of a real man.

This study focuses on main mobilization strategies used by ISIS to convince supporters to join terrorist activities. The strategies utilized by ISIS ideologies for mobilization and recruitment that work amongst the women can be broadly separated into four frequent recruiting and mobilization strategies and the social media tools to implement those strategies: the role-model, the copy-cat, the “sister” and the “alimah.”

THE “ROLE MODEL”

For the purpose of mobilizing women, the role model is a person followed by others due to her exceptional behavior, or success in implementing a particularly special task. Provided certain instructions and guidance, she can be emulated. Regarding the terroristic cells, the role model would usually be older in age than the follower, yet it could also be someone of a higher religious role. Following the research literature, Merton (Reference Merton1950) hypothesized that individuals compare themselves to groups of people who occupy the social role to which the individual aspires. In regards of role models strategically chosen and propagated for terrorist activity, there exist two types of models: the celebrity type and the community type. The celebrity type is a person who has been depicted by the relevant media as a hero and therefore became famous. The community role models are teachers or educators who fill the gap in the adolescents’ world. Therefore, teachers and mentors have a huge impact on the follower’s perception of the world.

One of the explicit examples of the celebrity role model for terroristic activity is Dr Aafia Siddiqui. While Aafia Siddiqui herself was never a member of ISIS – she was convicted and imprisoned before the group was formed – she is an example of a “Muslim woman warrior,” an ideal celebrated by jihadists around the Islamic world. As a highly educated Muslim woman who rejected what she viewed as Western freedoms, she represents an alternative, if highly controversial, portrait of empowerment that groups like ISIS use to appeal to other women. Consider how a female ISIS blogger, Umm-Layth, seeks to attract recruits: “Our role is even more important as women in Islam, since if we don’t have sisters with the correct Aqeedah [conviction] and understanding who are willing to sacrifice all their desires and give up their families and lives in the West to make Hijrah [migration] and please Allah, then who will raise the next generation of Lions?”

Examples of teachers and mentors are the former leaders of the female wing of the banned terror group once known as al Muhajiroun (Channel 4 2015). The three women identify themselves as Umm Saalihah, Umm L and Umm Usmaan on Twitter. They operate in positions of authority within their circles and lecture women in secretive study sessions.

For those types of mobilization strategies, mass media videos, newspaper reporting and both open and secret social media accounts can serve as the best way of recruiting followers.

COPY-CATS

The copy-cat effect is described in literature as a tendency toward sensational publicity about violent murders or suicides to result in more of the same through imitation. Media coverage has played a role in inspiring other criminals to commit crimes in a similar fashion. Publicly nourished and accepted crimes would serve as instant fuel and triggers for unstable lone-wolf terrorists to execute their own actions. That is why the purpose of terror organizations is to transmit the actions and share along in the medium in every way possible.

A specific example of copy-cat behavior of women within ISIS is the teenage girl jihadists sought by Interpol, who are seen to inspire copy-cats as two more Austrian teenagers try to run away to Syria to join ISIS (Charlton Reference Charlton2014):

Two teenage girls vanished from their homes in the Austrian capital Vienna. Interpol believes the two, aged 16 and 15, were tricked into going to Syria. Police are now concerned they may be inspiring other girls to join the holy war. Two other girls of the same age were caught attempting to flee the country.

Women in the captured territories are not the only ones subject to the mobilization attempts through copy-cat scenarios, but also women in the covert secret cells having personal connections with the ISIS fighters in Europe and in the Middle Eastern countries. As shown in the Paris attacks, cornered and under fire in a Saint-Denis apartment, a defiant 26-year-old Hasna Ait Boulahcen screamed back at French police before detonating a suicide vest. It is unclear whether she took an active role in the ISIS organization and execution of the terrorist action or been a victim of circumstances; however, the fact of being at the place with a suicide vest on her body suggests that she crossed the lines between empathic support towards active fight. As a relative of one of Abdelhamid Abaaoud, the suspected ringleader of the Paris attacks, Boulahcen’s presence at the time of the police raid has raised questions about her role in the massacre, and the role of women as potential ISIS front-line fighters. In recent months, horrific stories have emerged of the sexual slavery of women and girls by ISIS, some of whom have been bought and sold at slave markets (Foreign Affairs Committee 2018). Could the blast detonated by Boulahcen be a sign that women’s role with ISIS ranks is changing? “It’s certainly ISIS’ first female suicide bomber,” said Mia Bloom, author of Bombshell: The Many Faces of Women Terrorists (Bloom Reference Bloom2011), though the statement has been disputed regarding the circumstances of her being at that place. “Up until now ISIS has been very clear. The role for women is cooking, cleaning and childcare. They do not have women on the front lines,” she said (Ap Reference Ap2015).

Copy-cat behavior requires heavy coverage by mass media and establishing admiration from a certain part of the population. Desire for fame or seeking personal significance turns people so inclined into possible copy-cats. That is why massive usage across social media is required. Strategic usage of social media tools will be developed to realize the full potential of realistic viral video clips, which is the best strategy to trigger followers. Special channels that create Hollywood-style effects and glorification in turn bring more exposure, legitimization and support.

THE “SISTER”

The “sister” mobilization mode is a special mode of guiding while sharing experiences or more knowledge. The “sister” helps to guide a less experienced or less knowledgeable person while sharing her experience. The “sister” would be of the same age or even younger, coming from a similar social background, freely offering and sharing her area of expertise or ground experience. She ideally comes from the same educational and social circles as her target. The relationship mode of both will be of a partnership and sharing of thoughts, as the “sister” would have certain experience while the target would like to obtain and to learn from that experience.

For the terrorist action of the “sister” mode one can recognize two forms of the relationship: formal and informal. The formal mentoring occurs within secret cells when the authority of the “older sister” is clearly recognized and there is a distinct subordination hierarchy between the mentor and the “younger sisters.” The older sister would have already gone through the initial stage of joining the terrorist organization, sharing their recipes on how the process takes place, what the target is supposed to do and which tools she should use to succeed.

The informal relations include sharing the experience from a participant observer point of view, depicting thoughts and concerns and finding answers. The informal guidance is more of a “friendship” rather than a hierarchical relationship. The “sister” in this case would be of the same age and sharing the same education and social norms, the connection would be of sharing experience, even jokes, funny and interesting ideas and how-to-do advice.

The “sister” is the right person with whom to share thoughts about romance and marriage. As evidence shows, “Older girls and young women are also lured with promises of romance and marriage to ISIL fighters” (Mazurana, Van Leuven, and Gordon Reference Mazurana, Van Leuven and Gordon2015). For example, “ISIL women and girls also actively recruit other females in the name of ‘sisterhood,’ promising real and loving friendships. On the social media accounts, these women shower each other with love and affection” (Chastain Reference Chastain2014). They treat each other as actual sisters and best friends, which could bring in any woman who longs for friendships.”

However, promises are rarely the reality for foreign female recruits, particularly those from Western countries (de Freytas-Tamura Reference De Freytas-Tamura2017). Yet another promise to the women and girls who would willingly join ISIS is a relatively secure and comfortable life once they arrive in ISIS territories. Recruitment materials and testimony on social media from women and girls who have joined describe receiving rent- and bill-free housing, food and monetary allowances. They also receive spoils of war, according to celebratory posts on social media, new clothing and appliances looted from the homes of “the Kuffar [non-believers] and handed to you personally by Allah as a gift.”

To preserve the instant flow of initial contacts, open accounts in social networks are utilized. For the target of interpersonal correspondence and creation of social bondage, covered and secret accounts are used by mobilizers.

ALIMAH

Alimah is an Islamic religious woman with authority in the eyes of the followers. Alimah has special training on the body of Islamic law and in other Islamic disciplines, but can also be a woman mentor at a community level. While formal teaching of women on laws and traditions of Islam is prohibited for men, women teachers and authorities of religious conduct are the ones who are addressed for this matter. Under ISIS authority, the religious Sharia judges take the cruelest role, lashing, stoning and even beheading other women regarded as infidels. Those who followed the Sharia among ISIS and judges are considered the arbiters of Sharia law by mainstream Muslims.

For example, MailOnline states that ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi personally sentenced a woman to be beheaded as a wedding present for a sadistic female “judge” in the terror group’s feared religious police (Fagge Reference Fagge2015). The notoriously cruel woman asked to kill an unbelieving “infidel” in return for taking a new husband following the death of her mujahedin husband in a battle. Al-Baghdadi insisted she could only take the life of another woman in line with the group’s strict segregation of affairs between men and women. He ruled she could cut off the head of another female ISIS judge who had been accused of spying, but who had probably just fallen out of favor (Fagge Reference Fagge2015).

This is yet another example of an ideological construction of justification of gender-based segregation between men and women formulated in Allah’s will and Sharia laws. According to an issue of Dabiq, ISIS’s online magazine, the Western work life is “modern day slavery (Webb and Rahman Reference Webb and Rahman2014)…that leaves the Muslim in a constant feeling of subjugation to a kāfir [infidel] master.” In addition, a manifesto purportedly published by the al-Khanssaa Brigade – an all-female police group based in the Islamic State’s de facto capital for a time, al-Raqqa – declared that contemporary women “are not fulfilling their fundamental roles” because “women are not presented with a true picture of man and, because of the rise in the number of emasculated men who do not shoulder the responsibility allocated to them towards their ummah, religion or people, and not even towards their houses or their sons, who are being supported by their wives.” Under ISIS’s ideology, femininity is a requirement for masculinity: “If women were real women, then men would be real men” (Hall Reference Hall2014).

The evidence shows that ISIS’s propagandists, recruiters and supporters use highly gendered language to claim that those who are not part of the so-called Islamic State are neither truly masculine nor feminine. They suggest that the Western lifestyle is emasculating, and Western culture “restricts” Sunni Muslim women’s ability to be “feminine” – and thus men’s ability to be “masculine” (Mazurana et al. Reference Mazurana, Van Leuven and Gordon2015).

The religious appeal and ideological construction would require text, video and download tools to open the media for wider spreading of information and learning. Under this strategy, open social media accounts as well as restricted lists of true followers are utilized to magnify influence and bring followers to the next level of involvement and mobilization.

DEVIATION FROM THE “MANIFESTO FOR WOMEN”

The manifesto for women together with its translated form consists of around 41 pages (Abdul-Alim Reference Abdul-Alim2015). It states that all women should be hidden and that they should remain indoors. Shops which sell fashions are termed as evil and they should remain hidden. Men are ranked different from women according to this manifesto. As a matter of fact, they have different roles according to Islam. The number one requirement for women is that they should bear children so that they be mothers and they are expected to serve their husbands and children. Women are only allowed to leave their house under exceptional circumstances like to study religion or to wage jihad in cases when the men are not available. Female teachers and doctors have more privileges as they can leave their houses, but they are required to strictly keep the sharia guidelines just as they are described by ISIS.

This manifesto also states that if a woman in any case should be forced to work outside, then this should not exceed a maximum of three days and it should be strictly for short hours. The materialism of so-called Western culture is condemned in this manifesto as it is accused of causing women to move away from their work as wives and mothers to their children. Royal families of Saudi Arabia are accused of deviating from the true path of Islam, a good example being that they do not seem to be religiously committed to the ban on women driving.

This document also highlights how a girl who later becomes a woman should be taught how to live her life. For her to be a quality mother and wife, it demands a certain education which is mainly religious. According to the manifesto, at the age of 7 to 9 years the child should best be taught three lessons: fiqh (understanding) and religion, Qur’anic Arabic (writing and reading) and science (accounting and natural sciences) while from the age of 10 to 13 years more religious education should be introduced.

CONCLUSIONS

Women are encouraged by ISIS not only to take part in the building of the new Caliphate in the newly occupied lands, but also to recruit other women to take part in the actual fighting. ISIS utilizes different strategies applied to different women’s backgrounds. For those coming from the Western world, the glorification and description of the true paradise is the right tool for recruitment, while for those coming from Muslim backgrounds, the organizational and infrastructure instruments are utilized.

Social media tools are then used in an extended manner for the broadest exposure possible, including funneled channels to gain more mobilization. They are also ultra-efficient tools for closed cells and circles of coordination and organization, for ideological and strengthening religious inclination, and for the execution of actions.

In this respect, one of the serious questions which should be asked regarding women’s involvement in terrorist activity is whether they are passive agents or frontline jihadists. A report from the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ICSR) said that ISIS has been appealing more to women and girls in its propaganda. “ISIS has increased its female-focused efforts, writing manifestos directly for women, directing sections of its online magazine publications Dabiq to the ‘sisters of the Islamic State’ and allowing women to have a voice within their recruitment strategy – albeit via social media,” the report said (Saltman and Smith Reference Saltman and Smith2015:18). ISIS sees women as crucial in growing the population of jihadi loyalists, so that the Islamic State survives and expands beyond this generation. In many cases, women are also seen as “safe” recruits, especially if they are related to a male fighter, Mia Bloom said. “It’s a fantastic vetting mechanism for the terrorist organizations. They are always worried about being infiltrated and so if someone is related to an existing member they feel that they’re most trustworthy. So, this is something we see – it’s all in the family,” she explains (Ap Reference Ap2015).

Nikita Malik, a senior researcher at the Quilliam Think Tank, told the noted journalist Christiane Amanpour that she believes that the detonation of a suicide bomb by a woman is more of an exception than the norm. “It was done more as a defense mechanism than an act of violence. The Islamic State has said in its propaganda many times that women are to remain in the home and really their participation in jihad is more of a nurturing role as a mother and a wife,” she said. Malik also said that countering the increasing number of women going to Syria to join ISIS requires not just debunking the romantic myths of finding a strong fighter husband but theological ideas too (Ap Reference Ap2015).

For covert terrorist cells, the advantages of recruiting Muslim women into terrorist activity are tremendous: covered with a burka, a woman can carry different loads; only a woman police officer can freely open and search a woman; women are more devoted and intuitive than men; women are mostly motivated by emotions and ideology than material rewards; and women are better recruiters. Upon training and careful instruction, women can serve as perfect soldiers, as evidenced by military practices around the world.

“I know it sounds like a contradiction, because once they get there their lives are limited but somehow they think this is divinely mandated. A response to it would have to deal with the theological inaccuracies in some of the propaganda they’ve revealed as well,” said Nikita Malik (Ap Reference Ap2015).

In the Caliphate realities, single women were married upon arrival and joined women forces to protect the strict way of life in captured territories. There is little evidence of their fate in the ISIS Caliphate. One of the crucial questions regarding those facts is what those women can possibly do once they decide to go back to their native countries and influence their friends back home? The scope of their influence can be significant, as the number of Muslims in Western countries is growing permanently.

That is why paying close attention to the ways terrorist groups, like ISIS, recruit women into their activity by means of social networks is one of the critical tasks to prevent terrorist activity. Careful monitoring and discovering tools, channels and ways of radicalization and mobilization will help to intersect and prevent the activity, while taking proactive legal steps will reduce the attractiveness and relative easiness of crossing the physical and mental borders.

The role of the woman as the world audience perceives it, not that of a suicide bomber but of an ideological supporter and operational facilitator, is more important for the maintenance of the operational capabilities and the ideological motivation for a terrorist organization. The women follow a gender-specific interpretation of the radical ideology, the female Jihad, and can become a possible danger, while conflict is in place.

In recent years, terrorist organizations have focused much attention on women: both as targets of their murderous attacks as well as a potential demographic group for recruitment. But counterterrorism efforts across the world have not given enough thought to the idea that women can also represent an untapped resource in the fight against extremism and radicalization. Women are uniquely placed to effectively challenge extremist narratives in homes, schools and societies the world over; they wield tremendous influence on those most vulnerable to terrorist recruitment: youth. For this reason, it is important to examine the role of women as perpetrators and victims of terrorism as well as under-utilized resources in the ideological fight against terrorism.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge my daughter Noya, who led me to think about young girls exposed to social networks who make spontaneous and emotional choices under social and psychological influence and pressure.

Marina Shorer carries out research mainly in the areas of national security, biometrics and cyber security, immigration, global economics and online education. Her position as principal of IDmap Institute helps her to be involved in the development of national security and online studies. During the last decades, she has intensively published and lectured in academic and professional spheres. Her recent publications include contributions to the books of Handbook of Research on Civil Society and National Security in the Era of Cyber Warfare (2015) and National Security and Counterintelligence in the Era of Cyber Espionage (2016). Dr Shorer is a welcomed presenter at NATO and other top security forums. Her experience as former media liaison for the Israeli Ministry of Internal Security contributes to the integration of her knowledge of the routine of the governmental structures with theoretical and practical tools, helping students find new and creative insights and solutions.