1. Introduction

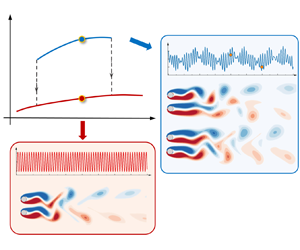

Bistability is a well-known phenomenon in dynamic systems where the system has two equilibrium states and rests in either state. The two states may or may not be connected, as shown in figure 1. For example, the hysteresis phenomenon with one loop, where the solution branches (states) are different when the control parameter is continuously increased and decreased, is a mode of bistable states that are mutually connected (type A in figure 1). In a certain class of problems, the two solution branches are connected through two hysteresis loops (illustrated by the type B of figure 1). Bistability can, however, occur in the absence of hysteresis when the two loops in type B coalesce, creating an isolated solution branch above the continuous branch (illustrated as the type C of figure 1). Since the two solution branches are non-connected, the isolated branch is also denoted as the ‘isola’ branch in the literature (Ganapathisubramanian & Showalter Reference Ganapathisubramanian and Showalter1984; Guidi & Goldbeter Reference Guidi and Goldbeter1997). In such cases, the system can jump from the solution branch of the isola to the continuous branch when the control parameter is varied but cannot undergo the reverse transition regardless of the increase or decrease of control parameter. Transition of this type is referred to as an irreversible transition. The irreversible transition has been found for steady-state bifurcations in chemical and biological systems (e.g. Ganapathisubramanian & Showalter Reference Ganapathisubramanian and Showalter1984; Guidi & Goldbeter Reference Guidi and Goldbeter1997). The bistabilities with hysteresis (types A and B) have also been observed in bluff-body flows, such as vortex-induced vibrations of a circular cylinder (e.g. Feng Reference Feng1968; Khalak & Williamson Reference Khalak and Williamson1999) and oscillatory flow around a near-wall cylinder (e.g. Xiong et al. Reference Xiong, Cheng, Tong and An2018). Nevertheless, irreversible bistable states have rarely been reported, especially in bluff-body flows, to the best knowledge of the authors. The present study provides a detailed account of the irreversible bistable states discovered in two parallel Kármán wakes, in particular on the origins and bifurcation behaviours of the bistable states.

Figure 1. Three types of bistability, namely, type A: bistability with one hysteresis loop, type B: ‘mushroom’ bistability, forming two hysteresis loops and type C: ‘isola’ bistability with irreversible transitions, re-plotted from figure 1 in Guidi & Goldbeter (Reference Guidi and Goldbeter1997). While the horizontal axis, ![]() $\alpha$, is the controlling parameter, the vertical axis,

$\alpha$, is the controlling parameter, the vertical axis, ![]() $x_s$, represents the response quantity in the system. The limit points, i.e.

$x_s$, represents the response quantity in the system. The limit points, i.e. ![]() $\alpha _1$–

$\alpha _1$–![]() $\alpha _4$, are associated with the critical value where the bifurcation occurs. The two equilibrium states are represented by solid lines.

$\alpha _4$, are associated with the critical value where the bifurcation occurs. The two equilibrium states are represented by solid lines.

Steady approaching flow around two identical side-by-side cylinders is governed by the gap ratio, ![]() $g^* = G/D$ and Reynolds number,

$g^* = G/D$ and Reynolds number, ![]() $Re = U_\infty D/\nu$, where

$Re = U_\infty D/\nu$, where ![]() $G$ is the gap distance between two cylinders (as shown in figure 2),

$G$ is the gap distance between two cylinders (as shown in figure 2), ![]() $U_\infty$ is the approaching velocity,

$U_\infty$ is the approaching velocity, ![]() $D$ is the cylinder diameter and

$D$ is the cylinder diameter and ![]() $\nu$ is the kinematic viscosity of the fluid. Many interesting flow features arise due to the interaction of two wakes. For example, at small

$\nu$ is the kinematic viscosity of the fluid. Many interesting flow features arise due to the interaction of two wakes. For example, at small ![]() $g^*$ values, e.g.

$g^*$ values, e.g. ![]() $g^* < {\sim }0.4$ in figure 3(a), the flow behaves like a single bluff body with a single Kármán vortex street that forms behind the two cylinders (e.g. the symmetric single bluff-body state, SS, and the asymmetric single bluff-body state, ASS, in figure 3a,c). The characteristic length scale of the flow is of the order of

$g^* < {\sim }0.4$ in figure 3(a), the flow behaves like a single bluff body with a single Kármán vortex street that forms behind the two cylinders (e.g. the symmetric single bluff-body state, SS, and the asymmetric single bluff-body state, ASS, in figure 3a,c). The characteristic length scale of the flow is of the order of ![]() $2D$. At large

$2D$. At large ![]() $g^*$, individual vortex shedding is formed behind each cylinder and synchronised in-phase and synchronised anti-phase wakes are identified at

$g^*$, individual vortex shedding is formed behind each cylinder and synchronised in-phase and synchronised anti-phase wakes are identified at ![]() $g^* > {\sim } 1.5$. Corresponding flow characteristics are dominated by length scales of

$g^* > {\sim } 1.5$. Corresponding flow characteristics are dominated by length scales of ![]() ${\sim }D$. At intermediate

${\sim }D$. At intermediate ![]() $g^*$ values, e.g.

$g^*$ values, e.g. ![]() $g^* = {\sim }0.4\text {--}1.5$, the flow features are dictated by the interaction of flow characteristics associated with both length scales, leading to complex flow features such as the flip-flop flows, where the flow through the gap flaps laterally at a lower frequency than the vortex shedding frequency.

$g^* = {\sim }0.4\text {--}1.5$, the flow features are dictated by the interaction of flow characteristics associated with both length scales, leading to complex flow features such as the flip-flop flows, where the flow through the gap flaps laterally at a lower frequency than the vortex shedding frequency.

Figure 2. Computational domain, ![]() $h$-type mesh (the physical mesh) distributions of two side-by-side cylinders at

$h$-type mesh (the physical mesh) distributions of two side-by-side cylinders at ![]() $g^{\ast} = 1$ used in the spectral/hp element method. The total mesh resolution is determined by both the distribution of the h-type meshes and the interpolation order

$g^{\ast} = 1$ used in the spectral/hp element method. The total mesh resolution is determined by both the distribution of the h-type meshes and the interpolation order ![]() $N_p$ for the p-type refinement. A close-up view on a

$N_p$ for the p-type refinement. A close-up view on a ![]() $hp$-refined mesh consisting of sixth-order Lagrange polynomials

$hp$-refined mesh consisting of sixth-order Lagrange polynomials ![]() $(N_{p} = 6)$ on Gauss–Lobatto–Legendre quadrature points is shown in the red-framed inset, where the p-type refined mesh is in grey. Velocity boundary conditions are shown in blue boxes.

$(N_{p} = 6)$ on Gauss–Lobatto–Legendre quadrature points is shown in the red-framed inset, where the p-type refined mesh is in grey. Velocity boundary conditions are shown in blue boxes.

Figure 3. Flow regime/mode distributions for the steady flow past (a) two circular cylinders and (b) two square cylinders in a side-by-side arrangement with the variation of gap ratio (![]() $g^*$) and Reynolds number (

$g^*$) and Reynolds number (![]() $Re$) reproduced from (a) Kang (Reference Kang2003), Carini, Giannetti & Auteri (Reference Carini, Giannetti and Auteri2014a) and Carini, Auteri & Giannetti (Reference Carini, Auteri and Giannetti2015) and (b) Mizushima & Hatsuda (Reference Mizushima and Hatsuda2014). The discrete symbols in (a) denote different flow regimes by Kang (Reference Kang2003). The overlapping symbols in regions 1, 2 and 3 in (a) represent cases that are sensitive to different initial conditions. The grey shaded area in (a) is the parameter space occupied by the FF flow by Kang (Reference Kang2003). Corresponding snapshots of the flow states for SS: single bluff-body vortex shedding, ASS: asymmetric bluff-body vortex shedding, IP: in-phase, AP: anti-phase and FF: flip-flop in (a) are represented in (c). The green and purple solid lines in (a) and (b) denoted the neutral curves of IP and AP modes, respectively.

$Re$) reproduced from (a) Kang (Reference Kang2003), Carini, Giannetti & Auteri (Reference Carini, Giannetti and Auteri2014a) and Carini, Auteri & Giannetti (Reference Carini, Auteri and Giannetti2015) and (b) Mizushima & Hatsuda (Reference Mizushima and Hatsuda2014). The discrete symbols in (a) denote different flow regimes by Kang (Reference Kang2003). The overlapping symbols in regions 1, 2 and 3 in (a) represent cases that are sensitive to different initial conditions. The grey shaded area in (a) is the parameter space occupied by the FF flow by Kang (Reference Kang2003). Corresponding snapshots of the flow states for SS: single bluff-body vortex shedding, ASS: asymmetric bluff-body vortex shedding, IP: in-phase, AP: anti-phase and FF: flip-flop in (a) are represented in (c). The green and purple solid lines in (a) and (b) denoted the neutral curves of IP and AP modes, respectively.

Kang (Reference Kang2003) conducted numerical simulations to map out flow regimes over a parameter space of ![]() $(g^*, Re) = (0.1\text {--}4, 40\text {--}160)$ with relatively coarse

$(g^*, Re) = (0.1\text {--}4, 40\text {--}160)$ with relatively coarse ![]() $Re$ and

$Re$ and ![]() $g^*$ resolutions. Six flow regimes were classified, namely, the anti-phase synchronised (AP), the in-phase synchronised (IP), the flip-flopping (FF), symmetric single bluff body (SS), asymmetric single bluff body (or deflected pattern, ASS) and steady pattern. The flow regime distributions over the parameter space of

$g^*$ resolutions. Six flow regimes were classified, namely, the anti-phase synchronised (AP), the in-phase synchronised (IP), the flip-flopping (FF), symmetric single bluff body (SS), asymmetric single bluff body (or deflected pattern, ASS) and steady pattern. The flow regime distributions over the parameter space of ![]() $(g^*, Re) = (0.3\text {--}4, 45\text {--}90)$ are re-plotted in figure 3(a), while the corresponding snapshots of each flow regime are represented in figure 3(c) by means of the present direct numerical simulations (DNS) with zero initial conditions. The FF flow was identified as a dominant flow state in a region at

$(g^*, Re) = (0.3\text {--}4, 45\text {--}90)$ are re-plotted in figure 3(a), while the corresponding snapshots of each flow regime are represented in figure 3(c) by means of the present direct numerical simulations (DNS) with zero initial conditions. The FF flow was identified as a dominant flow state in a region at ![]() $g^* = 0.4\text {--}1.5$, as shown by the grey shaded area in figure 3(a). Kang (Reference Kang2003) also found that the wake patterns in regions 1, 2 and 3 (figure 3a) could bifurcate to the flow states nearby, depending on initial conditions. For instance, the flow state in region 2 can be either FF or IP flow and either IP or AP synchronised state is stable in region 3.

$g^* = 0.4\text {--}1.5$, as shown by the grey shaded area in figure 3(a). Kang (Reference Kang2003) also found that the wake patterns in regions 1, 2 and 3 (figure 3a) could bifurcate to the flow states nearby, depending on initial conditions. For instance, the flow state in region 2 can be either FF or IP flow and either IP or AP synchronised state is stable in region 3.

Carini, Giannetti & Auteri (Reference Carini, Giannetti and Auteri2014b) and Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Auteri and Giannetti2015) quantified marginal curves of two distinct FF regions through linear (Floquet) stability analysis of the IP base flow over a parameter space of ![]() $(g^*,Re) = (0.6\text {--}2.4, 51\text {--}70)$. They ascribed the FF flow to an instability of two IP synchronised parallel wakes, rather than the alternative switching between upwards and downwards asymmetric vortex shedding states by Mizushima & Ino (Reference Mizushima and Ino2008) (named the ‘bistability conjecture’ in Carini et al. Reference Carini, Auteri and Giannetti2015). By introducing infinitesimal perturbations on the IP periodic base flow, the Floquet analysis produced a pair of unstable complex-conjugate multipliers above the critical threshold of

$(g^*,Re) = (0.6\text {--}2.4, 51\text {--}70)$. They ascribed the FF flow to an instability of two IP synchronised parallel wakes, rather than the alternative switching between upwards and downwards asymmetric vortex shedding states by Mizushima & Ino (Reference Mizushima and Ino2008) (named the ‘bistability conjecture’ in Carini et al. Reference Carini, Auteri and Giannetti2015). By introducing infinitesimal perturbations on the IP periodic base flow, the Floquet analysis produced a pair of unstable complex-conjugate multipliers above the critical threshold of ![]() $Re$, leading to a secondary instability of the IP limit cycle. It is also denoted as the Neimark–Sacker bifurcation or the secondary Hopf bifurcation, characterised by a two-dimensional invariant torus bifurcating from the limit cycle in the Poincaré map. By extending the Floquet analysis over the parameter plane, they tracked out two instability regions associated with the Neimark–Sacker bifurcation of the IP vortex shedding cycle, namely FF1 and FF2 regions (as the dotted blue and purple lines overlapped in Kang's regime map in figure 3a). Nevertheless, the DNS carried out by Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Auteri and Giannetti2015) found additional cases with FF features outside the FF1 and FF2 regions, e.g.

$Re$, leading to a secondary instability of the IP limit cycle. It is also denoted as the Neimark–Sacker bifurcation or the secondary Hopf bifurcation, characterised by a two-dimensional invariant torus bifurcating from the limit cycle in the Poincaré map. By extending the Floquet analysis over the parameter plane, they tracked out two instability regions associated with the Neimark–Sacker bifurcation of the IP vortex shedding cycle, namely FF1 and FF2 regions (as the dotted blue and purple lines overlapped in Kang's regime map in figure 3a). Nevertheless, the DNS carried out by Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Auteri and Giannetti2015) found additional cases with FF features outside the FF1 and FF2 regions, e.g. ![]() $60 < Re < 65$ at

$60 < Re < 65$ at ![]() $g^* = 1.8$. They speculated that the upper bound of the FF2 curve is associated with a subcritical Neimark–Sacker bifurcation. In addition, after overlapping the flow regime maps obtained through DNS (Kang Reference Kang2003) and the FF1 and FF2 marginal curves by Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Auteri and Giannetti2015), a discrepancy between the FF flow predicted by the two methods is clearly observed. The Floquet analysis of the IP base flow by Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Auteri and Giannetti2015) did not detect the presence of FF flow that was revealed by the DNS (Kang Reference Kang2003) in the vicinity of

$g^* = 1.8$. They speculated that the upper bound of the FF2 curve is associated with a subcritical Neimark–Sacker bifurcation. In addition, after overlapping the flow regime maps obtained through DNS (Kang Reference Kang2003) and the FF1 and FF2 marginal curves by Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Auteri and Giannetti2015), a discrepancy between the FF flow predicted by the two methods is clearly observed. The Floquet analysis of the IP base flow by Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Auteri and Giannetti2015) did not detect the presence of FF flow that was revealed by the DNS (Kang Reference Kang2003) in the vicinity of ![]() $g^* = 1.5$ (in the region sandwiched between FF1 and FF2 marginal curves). However, the exact cause for the discrepancy is unclear and has not been addressed so far.

$g^* = 1.5$ (in the region sandwiched between FF1 and FF2 marginal curves). However, the exact cause for the discrepancy is unclear and has not been addressed so far.

Previous studies that may offer some indications for the cause of the above contradiction will be briefly introduced below. By introducing infinitesimal perturbations on the steady symmetric base flow, the linear global stability analysis identified different forms of global instabilities in the steady flow past two circular cylinders (Mizushima & Ino Reference Mizushima and Ino2008; Carini et al. Reference Carini, Giannetti and Auteri2014a) and square cylinders (Mizushima & Hatsuda Reference Mizushima and Hatsuda2014). Two forms of instabilities that relevant to this study are the IP and AP modes, as the green and purple neutral stability curves tracked out over the parameter spaces in figure 3(a,b), respectively. The intersection between IP and AP neutral stability curves are denoted as an IP–AP codimension-two bifurcation point (![]() $g^*_c$,

$g^*_c$, ![]() $Re_c$). The IP and AP neutral stability curves separate the parameter space into four regions, as indicated in figure 3(b), which are, region I: the trivial symmetry steady mode; region II: IP mode; region III: AP mode; and region IV: mixed IP–AP mode. The flows in regions II and III are unstable to IP and AP mode disturbances, respectively, and the flow in region IV is unstable to both IP and AP mode disturbances. Region IV can be further divided into IV-1 and IV-2 based on weakly nonlinear analysis, according to a comprehensive study by Mizushima & Hatsuda (Reference Mizushima and Hatsuda2014). The flow is unstable to a mixed mode of IP and AP disturbances of finite amplitudes in region IV-2, while either the IP or AP mode of disturbance will survive by itself in region IV-1, depending on initial conditions. Because unique solutions exist, the flow is independent of initial conditions in regions I, II, III and IV-2. Although the weakly nonlinear analysis by Mizushima & Hatsuda (Reference Mizushima and Hatsuda2014) is for square cylinders, the general findings are expected to be at least qualitatively applicable to the present interest. The bistable feature in region IV-1 is likely relevant to the cause of the discrepancy in predicting FF flows by stability analysis and DNS for two side-by-side circular cylinders. Furthermore, Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Auteri and Giannetti2015), through a weakly nonlinear analysis, speculated that the quasi-periodic features of the FF flow in the vicinity of (

$Re_c$). The IP and AP neutral stability curves separate the parameter space into four regions, as indicated in figure 3(b), which are, region I: the trivial symmetry steady mode; region II: IP mode; region III: AP mode; and region IV: mixed IP–AP mode. The flows in regions II and III are unstable to IP and AP mode disturbances, respectively, and the flow in region IV is unstable to both IP and AP mode disturbances. Region IV can be further divided into IV-1 and IV-2 based on weakly nonlinear analysis, according to a comprehensive study by Mizushima & Hatsuda (Reference Mizushima and Hatsuda2014). The flow is unstable to a mixed mode of IP and AP disturbances of finite amplitudes in region IV-2, while either the IP or AP mode of disturbance will survive by itself in region IV-1, depending on initial conditions. Because unique solutions exist, the flow is independent of initial conditions in regions I, II, III and IV-2. Although the weakly nonlinear analysis by Mizushima & Hatsuda (Reference Mizushima and Hatsuda2014) is for square cylinders, the general findings are expected to be at least qualitatively applicable to the present interest. The bistable feature in region IV-1 is likely relevant to the cause of the discrepancy in predicting FF flows by stability analysis and DNS for two side-by-side circular cylinders. Furthermore, Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Auteri and Giannetti2015), through a weakly nonlinear analysis, speculated that the quasi-periodic features of the FF flow in the vicinity of (![]() $g^*_c$,

$g^*_c$, ![]() $Re_c$) might be associated with the nonlinear interaction between IP and AP states. However, no further investigation has been conducted to address this conjecture.

$Re_c$) might be associated with the nonlinear interaction between IP and AP states. However, no further investigation has been conducted to address this conjecture.

The objective of the present study is to elucidate the cause for the observed discrepancy in predicting FF flow regimes through DNS by Kang (Reference Kang2003) and stability analysis by Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Auteri and Giannetti2015). The focus of the study is then extended to the bifurcations of the bistable states. The remainder of the paper is organised in the following manner. In § 2, the numerical method and the concepts of phase dynamics are briefly introduced. The bistability phenomenon and the contradiction between DNS and Floquet analysis are explored in § 3. Discussion is offered in § 4. Major conclusions are drawn in § 5. Detailed validations of numerical methods are presented in the appendix.

2. Methodology

2.1. Numerical method

The governing equations for the present DNS are the non-dimensional incompressible Navier–Stokes (N–S) equations

\begin{equation} \left.\begin{gathered}

\boldsymbol{\nabla}\boldsymbol{\cdot}\boldsymbol{u}=0,\\

\partial\boldsymbol{u}/{\partial

t}={-}(\boldsymbol{u}\boldsymbol{\cdot}\boldsymbol{\nabla})\boldsymbol{u}

-\boldsymbol{\nabla}p+Re^{{-}1}\nabla^2\boldsymbol{u},

\end{gathered}\right\}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation} \left.\begin{gathered}

\boldsymbol{\nabla}\boldsymbol{\cdot}\boldsymbol{u}=0,\\

\partial\boldsymbol{u}/{\partial

t}={-}(\boldsymbol{u}\boldsymbol{\cdot}\boldsymbol{\nabla})\boldsymbol{u}

-\boldsymbol{\nabla}p+Re^{{-}1}\nabla^2\boldsymbol{u},

\end{gathered}\right\}

\end{equation}

where ![]() $\boldsymbol {u} = (u, v)$ is the velocity vector corresponding to

$\boldsymbol {u} = (u, v)$ is the velocity vector corresponding to ![]() $\boldsymbol {x} = (x, y)$,

$\boldsymbol {x} = (x, y)$, ![]() $t$ is the time and

$t$ is the time and ![]() $p$ is the pressure.

$p$ is the pressure.

Equation (2.1) is solved by using a spectral/hp element method embedded in the open-source software package Nektar++ (Cantwell et al. Reference Cantwell2015). The total mesh resolution in the spectral/hp element method is determined by both the distribution of the ![]() $h$-type elements and the interpolation order

$h$-type elements and the interpolation order ![]() $N_p$ for the

$N_p$ for the ![]() $p$-type refinement, so that the total mesh equals to

$p$-type refinement, so that the total mesh equals to ![]() $N_{el} \times N_p^2$, where

$N_{el} \times N_p^2$, where ![]() $N_{el}$ represents the total number of macro-elements in the

$N_{el}$ represents the total number of macro-elements in the ![]() $h$-type mesh. In the present study, sixth-order Lagrange polynomials are used on Gauss–Lobatto–Legendre quadrature points. A second-order time integration method, a velocity correction scheme and a Galerkin formulation are employed for all present simulations. For further information, please refer to the previous studies in Guermond & Shen (Reference Guermond and Shen2003), Blackburn & Sherwin (Reference Blackburn and Sherwin2004), Karniadakis, Israeli & Orszag (Reference Karniadakis, Israeli and Orszag1991) and Vos et al. (Reference Vos, Eskilsson, Bolis, Chun, Kirby and Sherwin2011).

$h$-type mesh. In the present study, sixth-order Lagrange polynomials are used on Gauss–Lobatto–Legendre quadrature points. A second-order time integration method, a velocity correction scheme and a Galerkin formulation are employed for all present simulations. For further information, please refer to the previous studies in Guermond & Shen (Reference Guermond and Shen2003), Blackburn & Sherwin (Reference Blackburn and Sherwin2004), Karniadakis, Israeli & Orszag (Reference Karniadakis, Israeli and Orszag1991) and Vos et al. (Reference Vos, Eskilsson, Bolis, Chun, Kirby and Sherwin2011).

As shown in figure 2, a reference Cartesian coordinate system (![]() $x$,

$x$, ![]() $y$) is defined with its origin being placed at the mid-point of the line connecting the centres of two cylinders. A rectangular computational domain in the size of

$y$) is defined with its origin being placed at the mid-point of the line connecting the centres of two cylinders. A rectangular computational domain in the size of ![]() $(50D + 100D)\times (50D + 50D)$ is adopted for the present scenario, where the steady flow is imposed from left to right in the

$(50D + 100D)\times (50D + 50D)$ is adopted for the present scenario, where the steady flow is imposed from left to right in the ![]() $x$-direction. A Dirichlet velocity boundary condition (

$x$-direction. A Dirichlet velocity boundary condition (![]() $u_\infty = U$ and

$u_\infty = U$ and ![]() $v_\infty = 0$) is specified on the inlet and lateral boundaries of the computational domain sides, while a Neumann velocity boundary condition (

$v_\infty = 0$) is specified on the inlet and lateral boundaries of the computational domain sides, while a Neumann velocity boundary condition (![]() $\partial u /\partial x = 0$ and

$\partial u /\partial x = 0$ and ![]() $\partial v /\partial x = 0$) is implemented on the outlet boundary. A no-slip boundary condition is enforced on the cylinder surfaces. As suggested by Karniadakis et al. (Reference Karniadakis, Israeli and Orszag1991) and Blackburn & Sherwin (Reference Blackburn and Sherwin2004), a high-order Neumann pressure condition is specified on all domain boundaries except a reference zero Dirichlet pressure condition is employed on the outlet boundary.

$\partial v /\partial x = 0$) is implemented on the outlet boundary. A no-slip boundary condition is enforced on the cylinder surfaces. As suggested by Karniadakis et al. (Reference Karniadakis, Israeli and Orszag1991) and Blackburn & Sherwin (Reference Blackburn and Sherwin2004), a high-order Neumann pressure condition is specified on all domain boundaries except a reference zero Dirichlet pressure condition is employed on the outlet boundary.

The initial conditions (IC) specified in the present study include,

(i) zero initial conditions (IC-0);

(ii) non-zero initial conditions: the simulation is initiated with instantaneous flow field from a fully developed flow at the adjacent upper and lower

$Re$ with an interval of

$Re$ with an interval of  $\Delta Re = 1$, namely IC-

$\Delta Re = 1$, namely IC- $Re_H$ and IC-

$Re_H$ and IC- $Re_L$, respectively;

$Re_L$, respectively;(iii) non-zero initial conditions: the simulation is initiated with instantaneous flow field from a fully developed flow at the adjacent upper and lower

$g^*$ with an interval of

$g^*$ with an interval of  $\Delta g^* = 0.1$, namely IC-

$\Delta g^* = 0.1$, namely IC- $g^*_H$ and IC-

$g^*_H$ and IC- $g^*_L$, respectively.

$g^*_L$, respectively.

The time-step size ![]() $\Delta t$ for each case is chosen to be

$\Delta t$ for each case is chosen to be ![]() $\Delta t = 0.002$, based on the Courant–Friedrichs–Lewy (CFL) stability criterion, which is defined as,

$\Delta t = 0.002$, based on the Courant–Friedrichs–Lewy (CFL) stability criterion, which is defined as,

where ![]() $|\boldsymbol {u}|$ is the magnitude of the velocity in each cell and

$|\boldsymbol {u}|$ is the magnitude of the velocity in each cell and ![]() $\Delta l$ is the cell size in the direction of the velocity. The maximum value of CFL is kept below 0.5 for all the simulations conducted in the present study.

$\Delta l$ is the cell size in the direction of the velocity. The maximum value of CFL is kept below 0.5 for all the simulations conducted in the present study.

Detailed two-dimensional (2-D) mesh and numerical scheme validations at ![]() $(g^*, Re) = (1.5, 100)$ will be presented in Appendix A.

$(g^*, Re) = (1.5, 100)$ will be presented in Appendix A.

2.2. Linear stability analysis

In addition to the 2-D DNS, linear (Floquet) stability analysis is conducted to investigate the bifurcations of periodic base flows in the ![]() $g^*-Re$ space. The Floquet analysis considers the evolution of velocity and pressure perturbations, namely,

$g^*-Re$ space. The Floquet analysis considers the evolution of velocity and pressure perturbations, namely, ![]() $\boldsymbol {u}'(x, y, t)$ and

$\boldsymbol {u}'(x, y, t)$ and ![]() $p'(x, y, t)$, respectively, to a

$p'(x, y, t)$, respectively, to a ![]() $T$-periodic base flow

$T$-periodic base flow ![]() $\boldsymbol {U}(x, y, t)$ by solving the linearised N–S equations as,

$\boldsymbol {U}(x, y, t)$ by solving the linearised N–S equations as,

\begin{equation} \left.\begin{gathered} \boldsymbol{\nabla}\boldsymbol{\cdot}\boldsymbol{u}'=0,\\ \partial\boldsymbol{u}'/{\partial t}={-}(\boldsymbol{U}\boldsymbol{\cdot}\boldsymbol{\nabla}\boldsymbol{u}' +\boldsymbol{u}'\boldsymbol{\cdot}\boldsymbol{\nabla}\boldsymbol{U})-\boldsymbol{\nabla}p'+Re^{{-}1}\nabla^2\boldsymbol{u}'. \end{gathered}\right\} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \left.\begin{gathered} \boldsymbol{\nabla}\boldsymbol{\cdot}\boldsymbol{u}'=0,\\ \partial\boldsymbol{u}'/{\partial t}={-}(\boldsymbol{U}\boldsymbol{\cdot}\boldsymbol{\nabla}\boldsymbol{u}' +\boldsymbol{u}'\boldsymbol{\cdot}\boldsymbol{\nabla}\boldsymbol{U})-\boldsymbol{\nabla}p'+Re^{{-}1}\nabla^2\boldsymbol{u}'. \end{gathered}\right\} \end{equation}

Since the perturbed flow ![]() $\boldsymbol {U}+\boldsymbol {u}'$ was recommended to satisfy the same boundary conditions as the base flow

$\boldsymbol {U}+\boldsymbol {u}'$ was recommended to satisfy the same boundary conditions as the base flow ![]() $\boldsymbol {U}$ (Barkley & Henderson Reference Barkley and Henderson1996), the velocity boundary conditions with

$\boldsymbol {U}$ (Barkley & Henderson Reference Barkley and Henderson1996), the velocity boundary conditions with ![]() $\boldsymbol {u}' =0$ and

$\boldsymbol {u}' =0$ and ![]() $\partial \boldsymbol {u}'/\partial \boldsymbol {n} =0$ are imposed on boundaries where Dirichlet and Neumann conditions are specified for the base flow, respectively. The mesh resolutions are identical to those employed in DNS. The method for 2-D Floquet stability analysis is identical to that reported by Elston, Sheridan & Blackburn (Reference Elston, Sheridan and Blackburn2004) and Elston, Blackburn & Sheridan (Reference Elston, Blackburn and Sheridan2006) and will not be detailed here.

$\partial \boldsymbol {u}'/\partial \boldsymbol {n} =0$ are imposed on boundaries where Dirichlet and Neumann conditions are specified for the base flow, respectively. The mesh resolutions are identical to those employed in DNS. The method for 2-D Floquet stability analysis is identical to that reported by Elston, Sheridan & Blackburn (Reference Elston, Sheridan and Blackburn2004) and Elston, Blackburn & Sheridan (Reference Elston, Blackburn and Sheridan2006) and will not be detailed here.

Owing to the periodicity of the base flow ![]() $\boldsymbol {U}(x, y, t)$, a temporal Fourier interpolation method is adopted to reconstruct the base flow through

$\boldsymbol {U}(x, y, t)$, a temporal Fourier interpolation method is adopted to reconstruct the base flow through ![]() $N_{t,s}$ equi-spaced time slices over one period

$N_{t,s}$ equi-spaced time slices over one period ![]() $T$. The solutions of

$T$. The solutions of ![]() $\boldsymbol {u}'(x, y, t)$ can be determined by using the Arnoldi method over the

$\boldsymbol {u}'(x, y, t)$ can be determined by using the Arnoldi method over the ![]() $K_n$ dimensions of Krylov subspaces and can be written as a sum of components

$K_n$ dimensions of Krylov subspaces and can be written as a sum of components ![]() $\boldsymbol {u}_{\boldsymbol {i}}'(x, y, t) = \tilde {\boldsymbol {u}}_{\boldsymbol {i}}'(x, y, t) \exp (\lambda T)$, where

$\boldsymbol {u}_{\boldsymbol {i}}'(x, y, t) = \tilde {\boldsymbol {u}}_{\boldsymbol {i}}'(x, y, t) \exp (\lambda T)$, where ![]() $\tilde {\boldsymbol {u}}_{\boldsymbol {i}}'(x, y, t)$ is a

$\tilde {\boldsymbol {u}}_{\boldsymbol {i}}'(x, y, t)$ is a ![]() $T$-periodic Floquet eigenfunction,

$T$-periodic Floquet eigenfunction, ![]() $\mu = \exp (\lambda T)$ is the Floquet multiplier of the system and

$\mu = \exp (\lambda T)$ is the Floquet multiplier of the system and ![]() $\lambda$ is the Floquet exponent. The flow is deemed as unstable if the complex Floquet multiplier

$\lambda$ is the Floquet exponent. The flow is deemed as unstable if the complex Floquet multiplier ![]() $\mu$ crosses the unit circle (

$\mu$ crosses the unit circle (![]() $\lambda > 0$), indicating the perturbation increased exponentially, whereas the flow is stable if

$\lambda > 0$), indicating the perturbation increased exponentially, whereas the flow is stable if ![]() $\mu$ remains in the unit circle (

$\mu$ remains in the unit circle (![]() $\lambda < 0$, perturbation decays). As suggested by Elston et al. (Reference Elston, Sheridan and Blackburn2004), the flow is characterised by a secondary period (or quasi-period) when

$\lambda < 0$, perturbation decays). As suggested by Elston et al. (Reference Elston, Sheridan and Blackburn2004), the flow is characterised by a secondary period (or quasi-period) when ![]() $\mu$ is a complex-conjugate pair with

$\mu$ is a complex-conjugate pair with ![]() $\mu =|\mu |\exp (\pm \textrm {i} \omega _s T)$. The secondary period

$\mu =|\mu |\exp (\pm \textrm {i} \omega _s T)$. The secondary period ![]() $T_s$ of the system is expressed as,

$T_s$ of the system is expressed as, ![]() $T_s = 2{\rm \pi} /\omega _s$.

$T_s = 2{\rm \pi} /\omega _s$.

In this study, two forms of ![]() $T$-periodic base flow, namely, IP base flow, which has a spatio-temporal symmetry, and AP base flow, with a reflection symmetry with respect to the

$T$-periodic base flow, namely, IP base flow, which has a spatio-temporal symmetry, and AP base flow, with a reflection symmetry with respect to the ![]() $x$-axis, are utilised in the Floquet analysis. The symmetry conditions are listed below,

$x$-axis, are utilised in the Floquet analysis. The symmetry conditions are listed below,

where the vorticity ![]() $\omega _z(x,y,t)$ indicates the curl of the 2-D velocity components

$\omega _z(x,y,t)$ indicates the curl of the 2-D velocity components ![]() $U=(u,v)$,

$U=(u,v)$,

It is noteworthy that either the IP or AP periodic base flow cannot be simply recovered by using a standard time integration of the governing equations in (2.1) for corresponding ![]() $Re$ where the FF flow develops. Two stabilisation approaches are employed in this study to generate the IP and AP periodic base flows, which will be introduced in Appendix B.

$Re$ where the FF flow develops. Two stabilisation approaches are employed in this study to generate the IP and AP periodic base flows, which will be introduced in Appendix B.

The stability analyses were carried out until the residual of the leading Floquet multiplier reached a value smaller than ![]() $10^{-6}$ or the simulations reached 1000 iterations. The present Floquet analyses on both IP and AP base flows use

$10^{-6}$ or the simulations reached 1000 iterations. The present Floquet analyses on both IP and AP base flows use ![]() $N_{t,s} = 32$ equi-spaced time slices to reconstruct the base flow feature over

$N_{t,s} = 32$ equi-spaced time slices to reconstruct the base flow feature over ![]() $T$ and

$T$ and ![]() $K_n = 16$ dimensions of Krylov subspace iteration are adopted to obtain the Floquet multiplier. Detailed dependence checks for the

$K_n = 16$ dimensions of Krylov subspace iteration are adopted to obtain the Floquet multiplier. Detailed dependence checks for the ![]() $N_{t,s}$ and

$N_{t,s}$ and ![]() $K_n$ are presented in Appendix C.

$K_n$ are presented in Appendix C.

2.3. Phase dynamics

The concept of phase dynamics is routinely used to investigate the dynamics of a self-sustained weakly nonlinear oscillator (or oscillators) subject to periodic external forcing. This method has been applied in the community of fluid mechanics to elucidate the synchronisation behaviours of quasi-periodic phenomena in self-excited jets (Li & Juniper Reference Li and Juniper2013), thermoacoustic systems (Kashinath, Li & Juniper Reference Kashinath, Li and Juniper2018) and bluff-body flows (Ren et al. Reference Ren, Cheng, Tong, Xiong and Chen2019; Konstantinidis et al. Reference Konstantinidis, Zhao, Leontini, Lo Jacono and Sheridan2020; Aswathy & Sarkar Reference Aswathy and Sarkar2021) and demonstrated to be effective in revealing the nature of flows that involves complex interactions.

The global wake structures behind two side-by-side cylinders are similar to a feedback system, where the Kármán vortex street that forms behind one cylinder is influenced by that of the other. The synchronisation state between the two wakes is determined based on the instantaneous phase difference between lifts on the two cylinders as,

where ![]() $\varPsi _i(t)$ represents the instantaneous phase of lift coefficient fluctuation

$\varPsi _i(t)$ represents the instantaneous phase of lift coefficient fluctuation ![]() $\Delta C_{Li} (t) = C_{Li} (t) - \langle C_{Li} (t)\rangle _{T_a}$ determined from the Hilbert transform (Pikovsky, Rosenblum & Kurths Reference Pikovsky, Rosenblum and Kurths2003),

$\Delta C_{Li} (t) = C_{Li} (t) - \langle C_{Li} (t)\rangle _{T_a}$ determined from the Hilbert transform (Pikovsky, Rosenblum & Kurths Reference Pikovsky, Rosenblum and Kurths2003), ![]() $i (= 1$ and

$i (= 1$ and ![]() $2)$ denotes the

$2)$ denotes the ![]() $i$th cylinder and

$i$th cylinder and ![]() $\langle \cdot \rangle _{T_a}$ denotes a time-averaged quantity over the statistical period,

$\langle \cdot \rangle _{T_a}$ denotes a time-averaged quantity over the statistical period, ![]() $T_a$.

$T_a$.

Generally, the resulting phase dynamics contains four synchronisation states, namely, phase locking, phase trapping, phase drifting and phase slipping, according to the temporal variations of ![]() $\varPsi (t)$. While the

$\varPsi (t)$. While the ![]() $\varPsi (t)$ of the phase locking state is time invariant,

$\varPsi (t)$ of the phase locking state is time invariant, ![]() $\varPsi (t)$ increases or decreases monotonically with time in the phase drifting state. The phase trapping state is featured by a long period oscillation of

$\varPsi (t)$ increases or decreases monotonically with time in the phase drifting state. The phase trapping state is featured by a long period oscillation of ![]() $\varPsi (t)$ around a constant value, while the

$\varPsi (t)$ around a constant value, while the ![]() $\varPsi (t)$ in the phase slipping state experiences a sudden slip at the end of each long period of oscillation (epoch). Similar but more detailed discussions can be found elsewhere (Pikovsky et al. Reference Pikovsky, Rosenblum and Kurths2003; Li & Juniper Reference Li and Juniper2013; Ren et al. Reference Ren, Cheng, Tong, Xiong and Chen2019).

$\varPsi (t)$ in the phase slipping state experiences a sudden slip at the end of each long period of oscillation (epoch). Similar but more detailed discussions can be found elsewhere (Pikovsky et al. Reference Pikovsky, Rosenblum and Kurths2003; Li & Juniper Reference Li and Juniper2013; Ren et al. Reference Ren, Cheng, Tong, Xiong and Chen2019).

In the present study, the value of ![]() $\langle \varPsi \rangle _{T_a}$ is used to interpret the IP or AP synchronisation state for periodic flows as the phase dynamics of those flows is in the phase locking state. For instance, when two wakes are in the IP synchronisation,

$\langle \varPsi \rangle _{T_a}$ is used to interpret the IP or AP synchronisation state for periodic flows as the phase dynamics of those flows is in the phase locking state. For instance, when two wakes are in the IP synchronisation, ![]() $\langle \varPsi \rangle _{T_a}$ exactly equals to an even-number multiple of

$\langle \varPsi \rangle _{T_a}$ exactly equals to an even-number multiple of ![]() ${\rm \pi}$, whereas the flow is deemed in the AP synchronisation when

${\rm \pi}$, whereas the flow is deemed in the AP synchronisation when ![]() $\langle \varPsi \rangle _{T_a}$ equals to an odd-number multiple of

$\langle \varPsi \rangle _{T_a}$ equals to an odd-number multiple of ![]() ${\rm \pi}$. All the values of

${\rm \pi}$. All the values of ![]() $\langle \varPsi \rangle _{T_a}$ are shifted to the interval of

$\langle \varPsi \rangle _{T_a}$ are shifted to the interval of ![]() $[0, {\rm \pi}]$ in the present study to provide a clear view of IP or AP synchronisation of two cylinder wakes.

$[0, {\rm \pi}]$ in the present study to provide a clear view of IP or AP synchronisation of two cylinder wakes.

For the FF flows, a rich phase dynamics, such as phase drifting, phase slipping and phase trapping states, is observed. Since ![]() $\varPsi (t)$ varies typically with time in FF flows, we found that the mean value of

$\varPsi (t)$ varies typically with time in FF flows, we found that the mean value of ![]() $\varPsi (t)$ over a statistical period,

$\varPsi (t)$ over a statistical period, ![]() $\langle \varPsi \rangle _{T_a}$ is not a good measure for classifying the synchronisations of FF flows, mainly because (I) some AP synchronised FF flows can have a zero mean value (would be identified as IP using

$\langle \varPsi \rangle _{T_a}$ is not a good measure for classifying the synchronisations of FF flows, mainly because (I) some AP synchronised FF flows can have a zero mean value (would be identified as IP using ![]() $\langle \varPsi \rangle _{T_a}$) and (II) the FF flows with phase drifting features have non-convergent

$\langle \varPsi \rangle _{T_a}$) and (II) the FF flows with phase drifting features have non-convergent ![]() $\langle \varPsi \rangle _{T_a}$ values. To solve the problem, we use the histogram of the probability of occurrence of

$\langle \varPsi \rangle _{T_a}$ values. To solve the problem, we use the histogram of the probability of occurrence of ![]() $\varPsi _k$ calculated over a small interval of

$\varPsi _k$ calculated over a small interval of ![]() $\varPsi$ (

$\varPsi$ (![]() $\Delta \varPsi /2{\rm \pi} = 0.02$) to represent the characteristics of FF flows. The FF flow is deemed to be primarily IP and AP if the dominant peak of

$\Delta \varPsi /2{\rm \pi} = 0.02$) to represent the characteristics of FF flows. The FF flow is deemed to be primarily IP and AP if the dominant peak of ![]() $\varPsi _k$, denoted by

$\varPsi _k$, denoted by ![]() $\varPsi _{k-p}$, falls within the ranges of

$\varPsi _{k-p}$, falls within the ranges of ![]() $[0, {\rm \pi}/2)$ and

$[0, {\rm \pi}/2)$ and ![]() $[{\rm \pi} /2, {\rm \pi}]$, respectively.

$[{\rm \pi} /2, {\rm \pi}]$, respectively.

3. Results

A number of interesting flow states are identified through DNS with IC-0, as shown by the flow regime map presented in figure 4. All simulations reported in the present study are carried out for at least 2000 non-dimensional time units (equivalent to approximately 400 vortex shedding periods). Simulations are continued for an extra 1000 non-dimensional time units after the flow becomes fully developed for the purpose of statistical analysis. The classification of flow states was primarily based on the synchronisation features of coupled Kármán wakes through the phase dynamics outlined in § 2.3. For convenience of discussions, the terminologies of ‘cluster shear layers’ and ‘gap shear layers’ are employed to define the two shear layers in the outer and gap regions, respectively.

Figure 4. Flow states distributions of steady flow past two identical cylinders in the side-by-side arrangement with the variation of gap ratio (![]() $g^*$) and Reynolds number (

$g^*$) and Reynolds number (![]() $Re$). The region flooded by grey indicates the occurrence of FF flows with IC-0. While the dashed grey line represents the onset of vortex shedding for the steady flow past two cylinders with a symmetry wall at

$Re$). The region flooded by grey indicates the occurrence of FF flows with IC-0. While the dashed grey line represents the onset of vortex shedding for the steady flow past two cylinders with a symmetry wall at ![]() $y/D = 0$, other dashed boundaries with colours indicate the boundary between two flow states estimated from DNS with IC-0. The solid lines and dotted lines are the marginal curves given by Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Giannetti and Auteri2014a,Reference Carini, Giannetti and Auterib, Reference Carini, Auteri and Giannetti2015). Corresponding force and flow features for cases marked by yellow circles are shown in figure 5.

$y/D = 0$, other dashed boundaries with colours indicate the boundary between two flow states estimated from DNS with IC-0. The solid lines and dotted lines are the marginal curves given by Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Giannetti and Auteri2014a,Reference Carini, Giannetti and Auterib, Reference Carini, Auteri and Giannetti2015). Corresponding force and flow features for cases marked by yellow circles are shown in figure 5.

The characteristic length scale of the flow is mainly dependent on ![]() $g^*$. The dominant length scales of the flow are approximately

$g^*$. The dominant length scales of the flow are approximately ![]() $2D$ at

$2D$ at ![]() $g^* \sim \mathit {0}$ and

$g^* \sim \mathit {0}$ and ![]() $1D$ at

$1D$ at ![]() $g^* \sim \mathcal {1}$, constituting the corresponding single bluff-body flow state at

$g^* \sim \mathcal {1}$, constituting the corresponding single bluff-body flow state at ![]() $g^* < {\sim }0.5$ and the synchronised AP wakes at

$g^* < {\sim }0.5$ and the synchronised AP wakes at ![]() $g^* > {\sim 3}$ in figure 4. In this paper, we denoted the flows at small and large

$g^* > {\sim 3}$ in figure 4. In this paper, we denoted the flows at small and large ![]() $g^*$ values as cluster-scale and cylinder-scale flows, respectively. At intermediate

$g^*$ values as cluster-scale and cylinder-scale flows, respectively. At intermediate ![]() $g^*$, especially for

$g^*$, especially for ![]() $g^* = {\sim }0.5\text {--}2$, it is not straightforward to quantify the length scale of the flow as the flow gradually transits from a cluster-scale flow feature to a cylinder-scale flow feature in the sequence of increasing

$g^* = {\sim }0.5\text {--}2$, it is not straightforward to quantify the length scale of the flow as the flow gradually transits from a cluster-scale flow feature to a cylinder-scale flow feature in the sequence of increasing ![]() $g^*$ values.

$g^*$ values.

Two examples of the cylinder-scale and cluster-scale IP flows at ![]() $(g^*, Re) = (2.0, 85)$ and (1.0, 55), respectively, are illustrated in figure 5(a,b) for reference. The two IP flows are located in two regions separated by a parameter space occupied by FF flows with IC-0. Both IP flows are characterised by the IP synchronisations of the lifts on the two cylinders. The vortex shedding for the IP flow at

$(g^*, Re) = (2.0, 85)$ and (1.0, 55), respectively, are illustrated in figure 5(a,b) for reference. The two IP flows are located in two regions separated by a parameter space occupied by FF flows with IC-0. Both IP flows are characterised by the IP synchronisations of the lifts on the two cylinders. The vortex shedding for the IP flow at ![]() $(g^*, Re) = (2.0, 85)$ is dominated by merged vortices of identical sign that are shed from individual cylinders, as illustrated in figure 5(a). The vortex shedding pattern for the flow in figure 5(b), however, is mainly featured by the shedding of large-scale vortices from the two cluster shear layers farther downstream from the cylinders. Vortex shedding around individual cylinders for the IP flow in figure 5(b) is very weak and the periodic lateral swing of gap flow is mainly induced by vortices shed from the cluster shear layers. The present observations of IP flows with cluster-scale features also agree with the findings by Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Giannetti and Auteri2014b), where the small gap eddies in the IP base flow at

$(g^*, Re) = (2.0, 85)$ is dominated by merged vortices of identical sign that are shed from individual cylinders, as illustrated in figure 5(a). The vortex shedding pattern for the flow in figure 5(b), however, is mainly featured by the shedding of large-scale vortices from the two cluster shear layers farther downstream from the cylinders. Vortex shedding around individual cylinders for the IP flow in figure 5(b) is very weak and the periodic lateral swing of gap flow is mainly induced by vortices shed from the cluster shear layers. The present observations of IP flows with cluster-scale features also agree with the findings by Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Giannetti and Auteri2014b), where the small gap eddies in the IP base flow at ![]() $g^* = 0.7$ are transported between two subsequent big vortices and shed from the outer shear layer on the opposite cylinder side.

$g^* = 0.7$ are transported between two subsequent big vortices and shed from the outer shear layer on the opposite cylinder side.

Figure 5. Typical lift force coefficient, ![]() $C_L$, and flow features for (a) the IP flow with cylinder-scale characteristics; (b) the IP flow with cluster-scale characteristics; (c) the AP

$C_L$, and flow features for (a) the IP flow with cylinder-scale characteristics; (b) the IP flow with cluster-scale characteristics; (c) the AP![]() $_B$ flow; and (d) the IP

$_B$ flow; and (d) the IP![]() $_B$ flow.

$_B$ flow.

The other flow states newly identified in figure 4 is the synchronised biased IP (IP![]() $_B$) and biased AP flow (AP

$_B$) and biased AP flow (AP![]() $_B$) strips denoted by the regions with inclined blue and purple lines, respectively. The force and flow characteristics of the AP

$_B$) strips denoted by the regions with inclined blue and purple lines, respectively. The force and flow characteristics of the AP![]() $_B$ regime presented in figure 5(c) show that two Kármán vortex streets formed behind the cylinders are no longer mirror reflections of each other as in AP flow (figure 3c). The gap flow in the AP

$_B$ regime presented in figure 5(c) show that two Kármán vortex streets formed behind the cylinders are no longer mirror reflections of each other as in AP flow (figure 3c). The gap flow in the AP![]() $_B$ flow is inclined towards one direction (towards the top in figure 5c) over the vortex shedding period. This asymmetric feature can also be inferred from the evolution of

$_B$ flow is inclined towards one direction (towards the top in figure 5c) over the vortex shedding period. This asymmetric feature can also be inferred from the evolution of ![]() $C_L$ on each cylinder, whereby large and small amplitudes of lift oscillations are observed on Cy1 and Cy2, respectively. Similar flow features have been observed in steady approaching flow past two square cylinders in a side-by-side arrangement (Ma et al. Reference Ma, Kang, Lim, Wu and Tutty2017), but not reported for two circular cylinders, to the best knowledge of the authors. The IP

$C_L$ on each cylinder, whereby large and small amplitudes of lift oscillations are observed on Cy1 and Cy2, respectively. Similar flow features have been observed in steady approaching flow past two square cylinders in a side-by-side arrangement (Ma et al. Reference Ma, Kang, Lim, Wu and Tutty2017), but not reported for two circular cylinders, to the best knowledge of the authors. The IP![]() $_B$ occurs in a region among FF flows at relatively high

$_B$ occurs in a region among FF flows at relatively high ![]() $Re$ (

$Re$ (![]() $0.6 < g^* < 0.9$,

$0.6 < g^* < 0.9$, ![]() $69 < Re < 90$ in figure 4). Figure 5(d) shows the force and flow features of a typical IP

$69 < Re < 90$ in figure 4). Figure 5(d) shows the force and flow features of a typical IP![]() $_B$ regime at

$_B$ regime at ![]() $(g^*,Re) = (0.8, 70)$, where the gap flow is biased downwards. The lift oscillations of both cylinders are periodic with time, mainly due to vortex shedding from Cy1 and cluster-scale vortex shedding in the far wake. Even though the gap shear layers undergo cyclic oscillations over each vortex shedding period (not shown here), they remain biased downwards. The large inclination angle of the gap flow suppresses the vortex shedding from Cy2 and induces a considerable separation distance between shear layers around Cy1.

$(g^*,Re) = (0.8, 70)$, where the gap flow is biased downwards. The lift oscillations of both cylinders are periodic with time, mainly due to vortex shedding from Cy1 and cluster-scale vortex shedding in the far wake. Even though the gap shear layers undergo cyclic oscillations over each vortex shedding period (not shown here), they remain biased downwards. The large inclination angle of the gap flow suppresses the vortex shedding from Cy2 and induces a considerable separation distance between shear layers around Cy1.

The FF flow is observed at intermediate ![]() $g^*$ values when the flow transits from a cluster-scale dominated flow feature to a cylinder-scale dominated feature, as shown by the region flooded with grey in figure 4. For the purpose of comparison, the marginal curves for FF1 and FF2 modes identified by Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Giannetti and Auteri2014b, Reference Carini, Auteri and Giannetti2015) are plotted as dotted blue and purple lines, respectively. As will be discussed in the following paragraphs, the flow in the region indicated by filled circles in purple can be either IP or FF depending on the disturbance in the flow. Therefore, the FF flow obtained from IC-0 in this region is denoted as FF

$g^*$ values when the flow transits from a cluster-scale dominated flow feature to a cylinder-scale dominated feature, as shown by the region flooded with grey in figure 4. For the purpose of comparison, the marginal curves for FF1 and FF2 modes identified by Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Giannetti and Auteri2014b, Reference Carini, Auteri and Giannetti2015) are plotted as dotted blue and purple lines, respectively. As will be discussed in the following paragraphs, the flow in the region indicated by filled circles in purple can be either IP or FF depending on the disturbance in the flow. Therefore, the FF flow obtained from IC-0 in this region is denoted as FF![]() $_C$ (‘

$_C$ (‘![]() $_C$’ for conditional) herein. The regions flooded by blue either side of the FF

$_C$’ for conditional) herein. The regions flooded by blue either side of the FF![]() $_C$ region are occupied by conditional FF flows, which will be elaborated further in the subsequent discussion.

$_C$ region are occupied by conditional FF flows, which will be elaborated further in the subsequent discussion.

The present study focuses primarily on the bifurcations associated with the IP/FF![]() $_C$ and IP/AP flow states. The following three highlights are noteworthy by comparing the present DNS results and Floquet analysis results from Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Giannetti and Auteri2014a,Reference Carini, Giannetti and Auterib, Reference Carini, Auteri and Giannetti2015):

$_C$ and IP/AP flow states. The following three highlights are noteworthy by comparing the present DNS results and Floquet analysis results from Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Giannetti and Auteri2014a,Reference Carini, Giannetti and Auterib, Reference Carini, Auteri and Giannetti2015):

(i) the lower branch of FF1 marginal curves by stability analysis is identical to the lower-bound boundary of FF flows predicted by DNS;

(ii) a new branch of FF flows with solid purple circles, i.e. FF

$_C$, is discovered by DNS with IC-0 but not by the Floquet analysis based on the IP base flow;

$_C$, is discovered by DNS with IC-0 but not by the Floquet analysis based on the IP base flow;(iii) a noticeable difference between the results of DNS and Floquet analysis near the lower branch of the FF2 marginal curve is observed.

The following analyses and discussions are centred around interpretation of the features observed above. It will be demonstrated that the presence of the flow state in the parameter range occupied by the FF![]() $_C$ state and the orange shaded area is dependent on IC.

$_C$ state and the orange shaded area is dependent on IC.

Similarities between flows around two circular cylinders and two square cylinders reported by Mizushima & Hatsuda (Reference Mizushima and Hatsuda2014) are observed. The parameter subspaces of IP–FF1, AP, FF2 and FF![]() $_C$ defined in this study correspond respectively to the II, III, IV-2 and IV-1 regions (figure 3b) by Mizushima & Hatsuda (Reference Mizushima and Hatsuda2014). The feature (i) observed above is likely because the origin of the FF1 flow is synchronised IP Kármán wakes, as pointed out by Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Giannetti and Auteri2014b). The solution of transition from the steady base flow to the IP state in this region is unique based on the findings from two square cylinders, meaning that the use of the IP base flow in stability analysis is appropriate, and the transition to the FF flow in this region is non-bistable accordingly. The interpretations of feature (ii) need more elaboration. Judging based on the findings by Mizushima & Hatsuda (Reference Mizushima and Hatsuda2014), a probable cause for the feature (ii) is that the bistable state of the IP or the AP single mode (region IV-1 in figure 3b) exists over the parameter subspace of FF

$_C$ defined in this study correspond respectively to the II, III, IV-2 and IV-1 regions (figure 3b) by Mizushima & Hatsuda (Reference Mizushima and Hatsuda2014). The feature (i) observed above is likely because the origin of the FF1 flow is synchronised IP Kármán wakes, as pointed out by Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Giannetti and Auteri2014b). The solution of transition from the steady base flow to the IP state in this region is unique based on the findings from two square cylinders, meaning that the use of the IP base flow in stability analysis is appropriate, and the transition to the FF flow in this region is non-bistable accordingly. The interpretations of feature (ii) need more elaboration. Judging based on the findings by Mizushima & Hatsuda (Reference Mizushima and Hatsuda2014), a probable cause for the feature (ii) is that the bistable state of the IP or the AP single mode (region IV-1 in figure 3b) exists over the parameter subspace of FF![]() $_C$ and it is stable or unstable to FF instabilities, respectively. The cause of feature (iii) is the emergence of synchronised AP

$_C$ and it is stable or unstable to FF instabilities, respectively. The cause of feature (iii) is the emergence of synchronised AP![]() $_B$ flow prior to the onset of FF flows, which is somewhat identified as the secondary instability to the IP base flows. This aspect will be elaborated further in the subsequent discussion.

$_B$ flow prior to the onset of FF flows, which is somewhat identified as the secondary instability to the IP base flows. This aspect will be elaborated further in the subsequent discussion.

3.1. Phase evolution

The dominant peak of ![]() $\varPsi _k$, i.e.

$\varPsi _k$, i.e. ![]() $\varPsi _{k-p}$, and the standard deviation of

$\varPsi _{k-p}$, and the standard deviation of ![]() $\varPsi _k$ over

$\varPsi _k$ over ![]() ${T_a}$,

${T_a}$, ![]() $\sigma$, are examined along the lines of

$\sigma$, are examined along the lines of ![]() $g^* = 1.5$ and

$g^* = 1.5$ and ![]() $Re = 60$ based on DNS with IC-0 in figure 6 with

$Re = 60$ based on DNS with IC-0 in figure 6 with ![]() $T_a = 1000$ to investigate potential bifurcation routes of the flow. The filled symbols and error bars represent the values of

$T_a = 1000$ to investigate potential bifurcation routes of the flow. The filled symbols and error bars represent the values of ![]() $\varPsi _{k-p}$ and

$\varPsi _{k-p}$ and ![]() $\sigma$, respectively. Different flow states are indicated by different symbols. The following features are noteworthy.

$\sigma$, respectively. Different flow states are indicated by different symbols. The following features are noteworthy.

Figure 6. Variations of the maximum probability phase of ![]() $\varPsi (t)$, i.e.

$\varPsi (t)$, i.e. ![]() $\varPsi _{k-p}$, at (a)

$\varPsi _{k-p}$, at (a) ![]() $(g^*, Re) = (1.5, 55\text {--}78)$ and (b)

$(g^*, Re) = (1.5, 55\text {--}78)$ and (b) ![]() $(0.7\text {--}3.5, 60)$ with IC-0. The statistical period is

$(0.7\text {--}3.5, 60)$ with IC-0. The statistical period is ![]() $T_a = 1000$. The black vertical bars indicate the standard deviation

$T_a = 1000$. The black vertical bars indicate the standard deviation ![]() $\sigma$ of

$\sigma$ of ![]() $\varPsi _{k-p}$ over

$\varPsi _{k-p}$ over ![]() $T_a$.

$T_a$.

(I) At ![]() $g^* = 1.5$, as shown in figure 6(a), the synchronised IP flow at

$g^* = 1.5$, as shown in figure 6(a), the synchronised IP flow at ![]() $Re < 56.5$ is featured by

$Re < 56.5$ is featured by ![]() $\varPsi _{k-p} = 0$ and

$\varPsi _{k-p} = 0$ and ![]() $\sigma = 0$ as expected. As

$\sigma = 0$ as expected. As ![]() $Re$ is furthered increased beyond the IP flow range,

$Re$ is furthered increased beyond the IP flow range, ![]() $\varPsi _{k-p}$ suddenly shifts to

$\varPsi _{k-p}$ suddenly shifts to ![]() ${\sim }{\rm \pi}$ with a non-zero

${\sim }{\rm \pi}$ with a non-zero ![]() $\sigma$ in the FF

$\sigma$ in the FF![]() $_C$ state and reverts back to zero in the IP state at

$_C$ state and reverts back to zero in the IP state at ![]() $Re > 71.5$. This observation indicates that the FF

$Re > 71.5$. This observation indicates that the FF![]() $_C$ is possibly bifurcated from the AP synchronisation state.

$_C$ is possibly bifurcated from the AP synchronisation state.

(II) The synchronisation feature of the flow undergoes changes in a sequence of IP–AP–IP–AP with increasing of ![]() $g^*$ values at

$g^*$ values at ![]() $Re = 60$ (figure 6b). The value of

$Re = 60$ (figure 6b). The value of ![]() $\varPsi _{k-p}$ varies gradually from 0 to

$\varPsi _{k-p}$ varies gradually from 0 to ![]() ${\rm \pi}$ with a non-zero

${\rm \pi}$ with a non-zero ![]() $\sigma$ as

$\sigma$ as ![]() $g^*$ increases in the FF1 region (the area flooded by green). At the onset of FF

$g^*$ increases in the FF1 region (the area flooded by green). At the onset of FF![]() $_C$,

$_C$, ![]() $\varPsi _{k-p}$ stables at

$\varPsi _{k-p}$ stables at ![]() ${\sim }{\rm \pi}$ at

${\sim }{\rm \pi}$ at ![]() $g^* = 1.35 \text {--} 1.85$ and is located between

$g^* = 1.35 \text {--} 1.85$ and is located between ![]() ${\rm \pi} /2$ and

${\rm \pi} /2$ and ![]() ${\rm \pi}$ as

${\rm \pi}$ as ![]() $g^*$ further increases. This again suggests the two wakes in the FF

$g^*$ further increases. This again suggests the two wakes in the FF![]() $_C$ flow are largely in the AP synchronisation. The value of

$_C$ flow are largely in the AP synchronisation. The value of ![]() $\varPsi _{k-p}$ suddenly shifts to 0 in the periodic IP state and returns back to

$\varPsi _{k-p}$ suddenly shifts to 0 in the periodic IP state and returns back to ![]() ${\rm \pi}$ in the periodic AP state at

${\rm \pi}$ in the periodic AP state at ![]() $g^* = 2.25$ and 3.0, respectively.

$g^* = 2.25$ and 3.0, respectively.

(III) The nearly zero values of ![]() $\sigma$ in the IP and AP states indicate the gap flow constitutes periodic oscillation and non-oscillation over the vortex shedding period,

$\sigma$ in the IP and AP states indicate the gap flow constitutes periodic oscillation and non-oscillation over the vortex shedding period, ![]() $T$, respectively. The non-zero

$T$, respectively. The non-zero ![]() $\sigma$ value displayed by the FF flow suggests the gap flow undergoes FF over the period other than

$\sigma$ value displayed by the FF flow suggests the gap flow undergoes FF over the period other than ![]() $T$. The larger the

$T$. The larger the ![]() $\sigma$, the more unstable the gap flow is.

$\sigma$, the more unstable the gap flow is.

3.2. Stabilities of IP and AP base flows

The Floquet analysis introduced in § 2.2 is then conducted to investigate the cause for the feature (ii) and is discussed in the following paragraphs.

To start with, the linear stability analysis based on the IP base flow is conducted along seven vertical lines for ![]() $g^* = 0.8 \text {--} 1.8$, as shown in figure 7(a), where the grey and blue shadows represent cases with stable and unstable Floquet multiplier(s), respectively. The critical bifurcation points for the onset of instability are estimated by using a linear interpolation of

$g^* = 0.8 \text {--} 1.8$, as shown in figure 7(a), where the grey and blue shadows represent cases with stable and unstable Floquet multiplier(s), respectively. The critical bifurcation points for the onset of instability are estimated by using a linear interpolation of ![]() $|\mu |$ to unity. The neutral stability curve for the onset of FF instability obtained from Floquet analysis on the IP base flow is plotted as the dashed orange line in figure 7(a). To facilitate further discussion, the marginal curves obtained from Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Giannetti and Auteri2014a,Reference Carini, Giannetti and Auterib, Reference Carini, Auteri and Giannetti2015) and the boundaries estimated from the present DNS with IC-0 are plotted in figure 7(a). More precisely, the solid green and purple lines represent respectively the marginal curves of IP and AP modes tracked out through the global stability analysis based on the steady symmetric base flow by Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Giannetti and Auteri2014a), the FF1 and FF2 marginal curves reported by Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Giannetti and Auteri2014b, Reference Carini, Auteri and Giannetti2015) are shown by the dotted blue and purple lines, and the boundary between FF and IP flows identified from DNS with IC-0 is indicated by the dashed green line.

$|\mu |$ to unity. The neutral stability curve for the onset of FF instability obtained from Floquet analysis on the IP base flow is plotted as the dashed orange line in figure 7(a). To facilitate further discussion, the marginal curves obtained from Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Giannetti and Auteri2014a,Reference Carini, Giannetti and Auterib, Reference Carini, Auteri and Giannetti2015) and the boundaries estimated from the present DNS with IC-0 are plotted in figure 7(a). More precisely, the solid green and purple lines represent respectively the marginal curves of IP and AP modes tracked out through the global stability analysis based on the steady symmetric base flow by Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Giannetti and Auteri2014a), the FF1 and FF2 marginal curves reported by Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Giannetti and Auteri2014b, Reference Carini, Auteri and Giannetti2015) are shown by the dotted blue and purple lines, and the boundary between FF and IP flows identified from DNS with IC-0 is indicated by the dashed green line.

Figure 7. Bifurcation diagrams of Floquet analyses based on (a) the IP periodic base flow along ![]() $g^* = 0.8 \text {--} 1.8$, and (b) the AP periodic base flow along

$g^* = 0.8 \text {--} 1.8$, and (b) the AP periodic base flow along ![]() $g^* = 1.5 \text {--} 2.0$. The shaded areas are the cases where Floquet analyses were conducted. The grey and blue areas represent the cases with stable and unstable Floquet multiplier(s), respectively. The symbols with different colours in (a) are the flow state distributions obtained from the DNS by initialising the flow from an IP flow with IC-

$g^* = 1.5 \text {--} 2.0$. The shaded areas are the cases where Floquet analyses were conducted. The grey and blue areas represent the cases with stable and unstable Floquet multiplier(s), respectively. The symbols with different colours in (a) are the flow state distributions obtained from the DNS by initialising the flow from an IP flow with IC-![]() $Re_L$ or IC-

$Re_L$ or IC-![]() $Re_H$. Neutral stability curves associated with the IP and AP periodic base flows in (a) and (b) are plotted as dashed orange and magenta lines, respectively.

$Re_H$. Neutral stability curves associated with the IP and AP periodic base flows in (a) and (b) are plotted as dashed orange and magenta lines, respectively.

For the cases with ![]() $g^* < 1.4$, the lower-bound

$g^* < 1.4$, the lower-bound ![]() $Re$ values for the onset of instability to IP base flow in figure 7(a) are consistent with the FF1 marginal curve predicted by Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Giannetti and Auteri2014b) and the present DNS with IC-0. In the vicinity of

$Re$ values for the onset of instability to IP base flow in figure 7(a) are consistent with the FF1 marginal curve predicted by Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Giannetti and Auteri2014b) and the present DNS with IC-0. In the vicinity of ![]() $g^* \sim 1.5$, the FF

$g^* \sim 1.5$, the FF![]() $_C$ flow predicted by DNS is not captured by the linear stability analysis based on IP base flow, identical to the results reported by Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Auteri and Giannetti2015). For the cases with

$_C$ flow predicted by DNS is not captured by the linear stability analysis based on IP base flow, identical to the results reported by Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Auteri and Giannetti2015). For the cases with ![]() $g^*> 1.5$ in the FF2 region, both the lower- and upper-bound

$g^*> 1.5$ in the FF2 region, both the lower- and upper-bound ![]() $Re$ values with unstable Floquet multipliers are close to those identified by Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Auteri and Giannetti2015), but are noticeably different from those results predicted by DNS with IC-0 as:

$Re$ values with unstable Floquet multipliers are close to those identified by Carini et al. (Reference Carini, Auteri and Giannetti2015), but are noticeably different from those results predicted by DNS with IC-0 as:

(I) Firstly, the lower-bound

$Re$ for FF flows predicted by the present Floquet analysis on the IP base flow is

$Re$ for FF flows predicted by the present Floquet analysis on the IP base flow is  $Re \sim 51.39$ at

$Re \sim 51.39$ at  $g^* = 1.8$ (the blue shadow in figure 7a), which is noticeably different from those predicted by DNS with IC-0 (

$g^* = 1.8$ (the blue shadow in figure 7a), which is noticeably different from those predicted by DNS with IC-0 ( $Re \sim 54.5$). This is because the AP and AP

$Re \sim 54.5$). This is because the AP and AP $_B$ flows emerge in a narrow strip of parameter space (e.g.

$_B$ flows emerge in a narrow strip of parameter space (e.g.  $Re = 51.5 \text {--} 54.5$ at

$Re = 51.5 \text {--} 54.5$ at  $g^* = 1.8$) prior to the onset of FF flows. Those flows are deemed unstable by Floquet analysis is because the vortex shedding frequency of the IP base flow used in the analysis differs substantially from that of the actual AP flow in the region, leading to a pair of unstable complex multipliers in the stability analysis.

$g^* = 1.8$) prior to the onset of FF flows. Those flows are deemed unstable by Floquet analysis is because the vortex shedding frequency of the IP base flow used in the analysis differs substantially from that of the actual AP flow in the region, leading to a pair of unstable complex multipliers in the stability analysis.(II) Secondly, the upper-bound critical

$Re = {\sim } 58.53$ for the FF flows predicted by Floquet analysis on the IP base flow is lower than the critical

$Re = {\sim } 58.53$ for the FF flows predicted by Floquet analysis on the IP base flow is lower than the critical  $Re = {\sim } 64.5$ from DNS with IC-0. The cause of this contradiction is because the FF flow at

$Re = {\sim } 64.5$ from DNS with IC-0. The cause of this contradiction is because the FF flow at  $g^* = 1.8$ for

$g^* = 1.8$ for  $Re = {\sim }58.5 \text {--} 64.5$ is located in the FF

$Re = {\sim }58.5 \text {--} 64.5$ is located in the FF $_C$ region and cannot be captured by the Floquet analysis on the IP base flow.

$_C$ region and cannot be captured by the Floquet analysis on the IP base flow.

Next, a linear stability analysis based on the AP periodic base flow is conducted at ![]() $g^* = 1.5$, 1.8 and 2.0 as revealed in figure 7(b). The regions with stable and unstable Floquet mode(s) and the boundary lines are labelled in the same manner as those in figure 7(a). The neutral stability curve obtained from the Floquet analysis on the AP base flow is plotted as the dashed magenta line in figure 7(b).

$g^* = 1.5$, 1.8 and 2.0 as revealed in figure 7(b). The regions with stable and unstable Floquet mode(s) and the boundary lines are labelled in the same manner as those in figure 7(a). The neutral stability curve obtained from the Floquet analysis on the AP base flow is plotted as the dashed magenta line in figure 7(b).

For the cases at ![]() $g^* = 1.5$, the predicted lower-bound

$g^* = 1.5$, the predicted lower-bound ![]() $Re = {\sim } 55.61$ of the FF

$Re = {\sim } 55.61$ of the FF![]() $_C$ flow largely agrees with the

$_C$ flow largely agrees with the ![]() $Re$ value predicted by DNS with IC-0 (

$Re$ value predicted by DNS with IC-0 (![]() $Re = {\sim } 55.5$), confirming our speculation that the AP base flow is unstable to FF flow instabilities. For the cases of

$Re = {\sim } 55.5$), confirming our speculation that the AP base flow is unstable to FF flow instabilities. For the cases of ![]() $g^* = 1.8$ and 2.0, the predicted lower-bound and upper-bound

$g^* = 1.8$ and 2.0, the predicted lower-bound and upper-bound ![]() $Re$ values agree neither with DNS nor with the stability results based on IP base flow. The Floquet analysis with the AP base flow is only capable of capturing the critical

$Re$ values agree neither with DNS nor with the stability results based on IP base flow. The Floquet analysis with the AP base flow is only capable of capturing the critical ![]() $Re$ values for the onset of AP

$Re$ values for the onset of AP![]() $_B$ flow, with a dominant real multiplier

$_B$ flow, with a dominant real multiplier ![]() $|\mu |>1$. For instance, the predicted lower-bound

$|\mu |>1$. For instance, the predicted lower-bound ![]() $Re$ values for the onset of AP

$Re$ values for the onset of AP![]() $_B$ flow at

$_B$ flow at ![]() $g^* = 1.8$ are

$g^* = 1.8$ are ![]() ${\sim }52.02$ and

${\sim }52.02$ and ![]() ${\sim }52.5$ for the Floquet analysis and DNS with IC-0, respectively.

${\sim }52.5$ for the Floquet analysis and DNS with IC-0, respectively.

The stability analysis based on the AP base flow is unable to predict the upper-bound ![]() $Re$ values of the FF

$Re$ values of the FF![]() $_C$ flows, likely caused by the following two reasons. Firstly, the method for generating the AP base flow is not applicable for the flow far away from the AP marginal curve (the purple solid line in figure 7). The vortex shedding frequency predicted by enforcing the symmetry condition at

$_C$ flows, likely caused by the following two reasons. Firstly, the method for generating the AP base flow is not applicable for the flow far away from the AP marginal curve (the purple solid line in figure 7). The vortex shedding frequency predicted by enforcing the symmetry condition at ![]() $y/D = 0$ can differ substantially from the actual vortex shedding frequency in the vicinity of upper branch of the marginal curves, resulting in unstable complex multipliers in the stability analysis in figure 7(b). In addition, the vortex shedding frequency of the periodic AP flow would differ significantly from that of the periodic IP flow at the same (

$y/D = 0$ can differ substantially from the actual vortex shedding frequency in the vicinity of upper branch of the marginal curves, resulting in unstable complex multipliers in the stability analysis in figure 7(b). In addition, the vortex shedding frequency of the periodic AP flow would differ significantly from that of the periodic IP flow at the same (![]() $g^*$,

$g^*$, ![]() $Re$) value. For instance, the Strouhal numbers,

$Re$) value. For instance, the Strouhal numbers, ![]() $St = 0.172$ and

$St = 0.172$ and ![]() $St = 0.167$ are predicted for the AP flow and the IP flow at

$St = 0.167$ are predicted for the AP flow and the IP flow at ![]() $(g^*, Re) = (2.5, 90)$, respectively. Because the AP flow cannot sustain in the IP region, the Floquet analysis based on the AP base flow would resolve the unstable Floquet multipliers.

$(g^*, Re) = (2.5, 90)$, respectively. Because the AP flow cannot sustain in the IP region, the Floquet analysis based on the AP base flow would resolve the unstable Floquet multipliers.

3.3. The influence of IC

3.3.1. The IP/FF $_C$ bistability

$_C$ bistability

The bistability nature of the base flow over the parameter space occupied by the FF![]() $_C$ flow is further confirmed through DNS by initialising the flow from an IP state at adjacent lower or higher

$_C$ flow is further confirmed through DNS by initialising the flow from an IP state at adjacent lower or higher ![]() $Re$ values but constant

$Re$ values but constant ![]() $g^*$ for

$g^*$ for ![]() $g^*$ from 0.8 to 1.8. The interval of

$g^*$ from 0.8 to 1.8. The interval of ![]() $Re$ is fixed as

$Re$ is fixed as ![]() $\Delta Re = 1$. To simplify the discussion, the flows initialised from the fully developed instantaneous flow field at adjacent lower or higher

$\Delta Re = 1$. To simplify the discussion, the flows initialised from the fully developed instantaneous flow field at adjacent lower or higher ![]() $Re$ values are denoted as IC-

$Re$ values are denoted as IC-![]() $Re_L$ and IC-

$Re_L$ and IC-![]() $Re_H$, respectively. Flow states identified with IC-

$Re_H$, respectively. Flow states identified with IC-![]() $Re_L$ and IC-