Introduction

Parasites have a significant impact on communities and ecosystems by directly affecting host fitness, with subsequent impacts on population dynamics and overall biodiversity (Hudson et al., Reference Hudson, Dobson and Lafferty2006; Tompkins et al., Reference Tompkins, Dunn, Smith and Telfer2011; Cable et al., Reference Cable, Barber, Boag, Ellison, Morgan, Murray, Pascoe, Sait, Wilson and Booth2017). Despite this, parasites are a fundamental component of healthy ecosystems with wide reaching impacts, from influencing the cycle of biogeochemical nutrients to regulating host density and functional traits (Hatcher et al., Reference Hatcher, Dick and Dunn2014; Preston et al., Reference Preston, Mischler, Townsend and Johnson2016). Parasites can also influence their host's behaviour, which can in turn alter the outcome of competitive interactions, reproductive behaviour and dispersal ability (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Mazzi and Zala1997; Macnab and Barber, Reference Macnab and Barber2012; Barber et al., Reference Barber, Mora, Payne, Weinersmith and Sih2017). During invasions by non-native species to new areas, parasites can play a key role facilitating or hindering the successful spread of invaders, while potentially having catastrophic effects on other related native species (Vilcinskas, Reference Vilcinskas2015).

Crayfish are freshwater crustaceans that are commercially harvested in many countries, but can also reach high densities and exert a significant impact on ecosystems, with several species having become widespread, damaging invaders (Holdich et al., Reference Holdich, James, Jackson and Peay2014; James et al., Reference James, Cable and Slater2014; Ercoli et al., Reference Ercoli, Ruokonen, Koistinen, Jones and Hämäläinen2015). For example, in Great Britain, the North American signal crayfish (Pacifastacus leniusculus) has become the most common crayfish species, having largely replaced the native white clawed crayfish (Austropotamobius pallipes, see Holdich et al., Reference Holdich, James, Jackson and Peay2014; James et al., Reference James, Cable and Slater2014). Crayfish are hosts to many parasites and symbionts, including viruses, bacteria, fungi and helminths that can cause chronic, long-term infections (Longshaw et al., Reference Longshaw, Bateman, Stebbing, Stentiford and Hockley2012; Kozubíková-Balcarová et al., Reference Kozubíková-Balcarová, Koukol, Martín, Svoboda, Petrusek and Diéguez-Uribeondo2013). One such parasite, the oomycete Aphanomyces astaci, the causative agent of crayfish plague, is a key threat to crayfish biodiversity worldwide (Svoboda et al., Reference Svoboda, Mrugała, Kozubíková-Balcarová and Petrusek2017), having eradicated many populations of native European crayfish (Filipová et al., Reference Filipová, Petrusek, Matasová, Delaunay and Grandjean2013; Kozubíková-Balcarová et al., Reference Kozubíková-Balcarová, Beran, Ďuriš, Fischer, Horká, Svoboda and Petrusek2015) and recent evidence suggests it may have also caused a decline in commercially harvested North American crayfish stocks (Edsman et al., Reference Edsman, Nyström, Sandström, Stenberg, Kokko, Tiitinen, Makkonen and Jussila2015; Jussila et al., Reference Jussila, Vrezec, Makkonen, Kortet and Canning-Clode2015). This obligate parasitic oomycete penetrates host tissues (Söderhäll et al., Reference Söderhäll, Svensson and Unestam1978) and produces motile reproductive zoospores (Cerenius and Söderhäll, Reference Cerenius and Söderhäll1984), which can reach high densities (up to several hundred zoospores per litre) during a crayfish plague outbreak (Strand et al., Reference Strand, Jussila, Johnsen, Viljamaa-Dirks, Edsman, Wiik-Nielsen, Viljugrein, Engdahl and Vrålstad2014). An infected individual can release about 2700 zoospores per week (Strand et al., Reference Strand, Jussila, Viljamaa-Dirks, Kokko, Makkonen, Holst-Jensen, Viljugrein and Vrålstad2012), and this number can be much higher when the crayfish is dying or moulting (Makkonen et al., Reference Makkonen, Strand, Kokko, Vrålstad and Jussila2013; Svoboda et al., Reference Svoboda, Kozubíková-Balcarová, Kouba, Buřič, Kozák, Diéguez-Uribeondo and Petrusek2013).

Generally, North American crayfish species which have co-evolved with A. astaci are considered to be chronic but largely asymptomatic carriers. They combat A. astaci through consistent production of prophenoloxidase, which activates a melanization cascade resulting in melanization of hyphae that prevents their invasion into host soft tissues (Cerenius et al., Reference Cerenius, Söderhäll, Persson and Ajaxon1987). Most native European crayfish, on the other hand, apparently only produce prophenoloxidase only in response to infection, which is too slow to effectively melanize the hyphae that then spread into host tissues leading to paralysis and death (Cerenius et al., Reference Cerenius, Bangyeekhun, Keyser, Söderhäll and Söderhäll2003). The Australian yabby (Cherax destructor) also suffers high mortality as a result of crayfish plague, though this species shows some resistance to less virulent strains and survives longer when exposed to highly virulent strains compared to highly susceptible species (Mrugała et al., Reference Mrugała, Veselý, Petrusek, Viljamaa-Dirks and Kouba2016). In infected European crayfish, severe behavioural changes before death include a lack of coordination and paralysis (Gruber et al., Reference Gruber, Kortet, Vainikka, Hyvärinen, Rantala, Pikkarainen, Jussila, Makkonen, Kokko and Hirvonen2014), though to what extent carrier crayfish exhibit behavioural changes is largely unknown and this could play a vital role during new invasions and in commercial crayfish farms. Highly infected crayfish, for example, might be less likely to disperse, which would alter invasion success and introduction to new habitats.

Few studies have directly assessed the effect of the A. astaci on North American species, although there is some evidence that they can succumb to the disease and display altered behaviour if also stressed by other factors (Cerenius et al., Reference Cerenius, Söderhäll, Persson and Ajaxon1987; Aydin et al., Reference Aydin, Kokko, Makkonen, Kortet, Kukkonen and Jussila2014; Edsman et al., Reference Edsman, Nyström, Sandström, Stenberg, Kokko, Tiitinen, Makkonen and Jussila2015). Co-infection of A. astaci and Fusarium spp., for example, results in eroded swimmeret syndrome (ESS) in signal crayfish, which causes females to carry fewer eggs (Edsman et al., Reference Edsman, Nyström, Sandström, Stenberg, Kokko, Tiitinen, Makkonen and Jussila2015). Mortality of adult signal crayfish has also been observed in experimental settings, though only when crayfish were exposed to very high zoospore numbers (Aydin et al., Reference Aydin, Kokko, Makkonen, Kortet, Kukkonen and Jussila2014). Furthermore, vertical transmission of A. astaci (from adults to eggs) has been reported (Makkonen et al., Reference Makkonen, Kokko, Henttonen and Jussila2010), and little is known on how A. astaci might affect juvenile North American crayfish.

Here, we addressed two key issues regarding the effects of A. astaci on signal crayfish. First, we tested the hypothesis that juvenile signal crayfish would suffer high mortality upon infection by A. astaci zoospores, as it has previously been suggested that juvenile crayfish may be more susceptible to infection compared to adults (Mrugała et al., Reference Mrugała, Veselý, Petrusek, Viljamaa-Dirks and Kouba2016). Additionally, we assessed the effect of A. astaci on adult signal crayfish, hypothesizing that even if adults may not suffer significant mortality, behavioural changes would be apparent.

Materials and methods

Signal crayfish trapping

All adult signal crayfish were collected in February and March 2017 using cylindrical traps (‘Trappy Traps’, Collins Nets Ltd., Dorset, UK) baited with cat food and checked daily (trapping licence: NT/CW081-B-797/3888/02). The crayfish were collected from a population displaying negligible levels of infection (maximum agent level A1) when assessed in 2014 (Derw Farm pond, Powys, Wales, SO 13891 37557; James et al., Reference James, Nutbeam-Tuffs, Cable, Mrugała, Viñuela-Rodriguez, Petrusek and Oidtmann2017). A small subset of individuals (n = 3) re-tested by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) (see ‘Aphanomyces astaci culture and quantification’ section) before the experiments began in May 2017 all revealed low levels of infection by A. astaci, although elevated compared to 2014 (agent level A2/A3). After removal from traps, crayfish were transferred to individual containers with 500 mL of pond water and transported to the Cardiff University Aquarium (holding licence: W C ILFA 002), where they were maintained individually in 20 L aquaria containing a plant pot refuge, gravel and air supply delivered via an airstone. The crayfish were held at 13 ± 1°C under a 12 h light:12 h dark lighting regime and fed a mixture of frozen peas and Tubifex bloodworm (Shirley Aquatics, Solihull, West Midlands, UK) once every 2 days. A 50% water change was conducted 1 h after feeding to maintain water quality and remove excess food. Crayfish were acclimatized to the laboratory for at least 4 weeks before the experiments began. Four females were carrying eggs, and upon hatching, the offspring were mixed, moved to 120 L communal aquaria and used in the juvenile infection experiment. Only male crayfish were used in the adult behavioural tests; since a relatively low number of females (n = 6) were caught and therefore it was not possible to test an equal number of males and females in this experiment.

Aphanomyces astaci culture and quantification

Crayfish in the current study were exposed to a group B strain (Pec14) of A. astaci provided by Charles University in Prague. This strain was isolated from dead Astacus astacus from a crayfish plague outbreak in the Černý Brook, Czech Republic (Kozubíková-Balcarová et al., Reference Kozubíková-Balcarová, Beran, Ďuriš, Fischer, Horká, Svoboda and Petrusek2015) and demonstrated similarly high virulence towards European A. astacus (see Becking et al., Reference Becking, Mrugała, Delaunay, Svoboda, Raimond, Viljamaa-Dirks, Petrusek, Grandjean and Braquart-Varnier2015) as the strains from group B (PsI) used in other experimental studies (Makkonen et al., Reference Makkonen, Jussila, Kortet, Vainikka and Kokko2012; Jussila et al., Reference Jussila, Kokko, Kortet and Makkonen2013). The culture was maintained in Petri dishes of RGY agar (Alderman, Reference Alderman1982; Becking et al., Reference Becking, Mrugała, Delaunay, Svoboda, Raimond, Viljamaa-Dirks, Petrusek, Grandjean and Braquart-Varnier2015; Mrugała et al., Reference Mrugała, Veselý, Petrusek, Viljamaa-Dirks and Kouba2016) and zoospores were produced according to the methodology of Cerenius et al. (Reference Cerenius, Söderhäll, Persson and Ajaxon1987). Briefly, two to four agar culture plugs (~2 mm2) were cut from an RGY culture and placed in flasks containing 200 mL of liquid RGY-medium. Multiple replicates were done each time in order to produce a sufficient number of zoospores. These cultures were allowed to grow at 16°C for 2–4 days on a shaker. Once sufficient mycelial growth had occurred, the cultures were washed to induce sporulation and transferred to separate flasks (containing 500 mL of distilled water). The washing was repeated in distilled water three to four times over ~8 h. Then, the cultures were incubated at 13 ± 1°C for 24–36 h until motile zoospores were produced. The number of zoospores was quantified using a haemocytometer.

Following both experiments, crayfish were euthanized by freezing at −20°C for 1 h. For juveniles, the whole crayfish was lysed (TissueLyser, Qiagen) and DNA extracted using a Qiagen DNeasy extraction kit (Qiagen). For adult crayfish, a section of tail-fan and soft-abdominal tissue was removed by dissection, lysed (TissueLyser, Qiagen), and both tissues were pooled (~20 mg total), and the DNA extracted using the same kits. Infection intensity was estimated based on the number of PCR-forming units (PFU) determined by qPCR using TaqMan MGB probes and expressed using the semi-quantitative levels A0–A7 for adults (as described by Vrålstad et al., Reference Vrålstad, Knutsen, Tengs and Holst-Jensen2009); with slight modification of the protocol as in Svoboda et al. (Reference Svoboda, Strand, Vrålstad, Grandjean, Edsman, Kozák, Kouba, Fristad, Koca and Petrusek2014). For juveniles, infection intensity was expressed as number of PFU because a direct comparison cannot be made here between juvenile (whole body) and adult (sample body) infection levels.

Juvenile crayfish infection

Here, we monitored the survival of juvenile signal crayfish that hatched in the laboratory when exposed either to A. astaci at 1, 10 or 100 zoospores mL−1 or to a sham treatment (control). All crayfish used in this experiment hatched within a 3-day period in May 2017. The infection was conducted twice in separate experiments, the first time approximately 4 weeks after the crayfish hatched (n = 25 crayfish per zoospore treatment) and the second time after 10 weeks with different crayfish (n = 17 individuals per zoospore treatment). When the experiment began, crayfish were housed individually in 1 L pots containing distilled water with a gravel substrate for 48 h. After this acclimatization period, the pots were spiked with 1, 10 or 100 zoospores mL−1 (the control treatment was given a 20% water change). After a 24 h infection period, 80% of the water in all pots was changed. The crayfish were fed crushed algae wafers and frozen Tubifex bloodworm (Shirley Aquatics, Solihull, West Midlands, UK) once every 2 days. A 50% water change was conducted 1 h after feeding to maintain water quality. For 14 days, we recorded crayfish deaths and any moults daily. Crayfish and moulted carapaces were stored in ethanol at −20°C until DNA was extracted.

Adult crayfish behaviour

Male crayfish behaviour was tested in an arena (Fig. 1) consisting of a tank (L: 100 cm × H: 53 cm × W: 48 cm) with access to a terrestrial area (L: 120 cm × H: 20 cm × W: 20 cm). At the start of the experiment, crayfish were divided into two groups: those destined for ‘high-infection’ and those to be kept at ‘low-infection’ levels. Those destined for the ‘high-infection’ group (n = 15, mean carapace length 52.2 mm, s.d. = 4.44) were individually exposed to a dose of 1000 zoospores mL−1 in 500 mL of water for 24 h. Simultaneously, the ‘low-infection’ crayfish (n = 17, mean carapace length 53.1 mm, s.d. = 4.66) were sham-infected by adding the same amount of distilled water instead of spore-containing water. After the 24 h period, all crayfish were returned to their individual tanks, where they were held for 1 week before their behaviour was assessed. Individual crayfish were placed into the behavioural arena (Fig. 1) and left to acclimatize overnight. Then, at 09:00 h the next day, their behaviour was recorded using an infrared CCTV camera (Sentient Pro HDA DVR 8 Channel CCTV, Maplin, Rotherham, UK) for 24 h (09:00–21:00 light and 21:00–09:00 dark). During video analysis, the time spent engaged in each of the following four behaviours was recorded for each crayfish: actively walking in water, in a refuge, stationary out of the refuge and moving out of water.

Fig. 1. Experimental arena used to assess crayfish behaviour. The tank was filled with water up to 3 cm below the level of the terrestrial area. The base of the arena, ramp (incline 30°) and bridge were coated in 1–2 cm of pea gravel.

Following this, each crayfish was moved to an aquarium (W: 30 cm × L: 61 cm × D: 37 cm) with covered sides and allowed to settle for 30 min before their response to being gently touched on the rostrum for 10 s was tested. Crayfish typically reacted by raising their chelae (an aggressive, threatening response) and/or retreating using a characteristic ‘tail-flip’ response. If a crayfish retreated, the glass rod was immediately moved again to touch the rostrum. This test was repeated three times with 5 min intervals. Whether the crayfish reacted with a ‘tail-flip’ and/or raised its chelae to attack was recorded. These responses were recorded since behavioural changes that affect a crayfish's ability to retreat or interact with conspecifics may have subsequent effects on competitive ability, resource acquisition, and ultimately, survival.

Following behavioural tests, crayfish were euthanized and A. astaci infection levels were quantified as described in the section ‘Aphanomyces astaci culture and quantification’.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in R version 3.5.1 (R Core Team, 2018). For the juvenile crayfish experiment, Kaplan–Meier survival analyses were performed using the ‘survival’ package in R (Terry and Therneau, Reference Terry and Therneau2018) with separate models run for both time points (4- and 10-weeks post-hatching). Both models included spore concentration and carapace length as independent variables. Model selection was based on Akaike information criterion (AIC). It was not possible to statistically assess the effect of moulting on mortality as an insufficient number of moulting events were recorded.

For the adult crayfish, the time spent moving (active), in shelter, stationary (outside of a shelter) or out of the water was quantified over 24 h for each individual. Generalized Additive Models for Location, Scale and Shape (GAMLSS) models (Stasinopoulos et al., Reference Stasinopoulos, Rigby and Akantziliotou2008) with appropriate distributions (see Table 1) were used to determine whether ‘treatment’ (i.e. high or low infection) or carapace length (mm) influenced the proportion of time crayfish spent moving, in shelter, out of water or stationary. In the GAMLSS with beta-inflated or beta zero-inflated distributions, the μ parameter refers to the average amount of time spent engaging in a particular behaviour, whilst ν relates to the likelihood of a behaviour not occurring (Stasinopoulos et al., Reference Stasinopoulos, Rigby and Akantziliotou2008). To assess the response of crayfish to a touch stimulus, threatening or tail flip escape responses were scored separately. The crayfish were tested three times, and it was noted whether they retreated by tail flipping and/or threatened by raising the chelae at least once during the three tests. These data were analysed in binomial models (i.e. threat/no threat, tail flip/no tail flip), using GAMLSS. Treatment group and carapace length were included as independent variables.

Table 1. Results of GAMLSS statistical analyses and mean proportion of time crayfish spent engaged in different behaviours over 24 h

BE, beta; BEZI, beta zero-inflated; BEINF, beta-inflated; BI, binomial; s.d., standard deviation.

Significant results (P < 0.05) are highlighted in bold.

a Denotes proportion of crayfish, not the mean.

Results

Juvenile crayfish infection

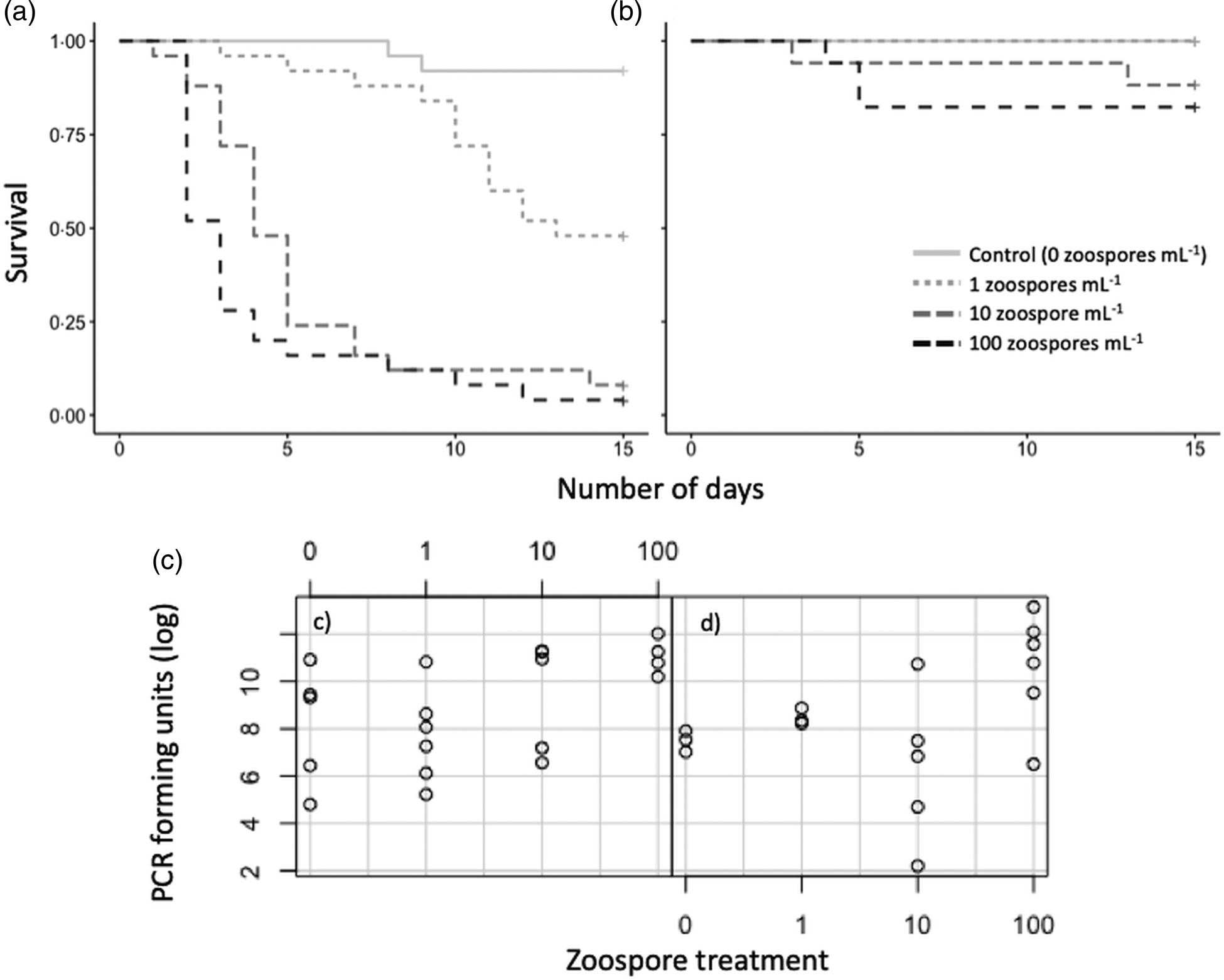

At 4-weeks old, zoospore concentration significantly affected survival of juvenile signal crayfish (z = 5.971, P < 0.001), with almost all crayfish dying in both the 10 and 100 zoospore mL−1 treatments after the 14-day experimental period (Fig. 2). Around half of the crayfish died in the 1 zoospore mL−1 treatment, whilst 92% of control treatment crayfish survived. Carapace length also had a significant effect on the survival of these crayfish, with larger individuals surviving longer (z = −4.387, P < 0.001). In contrast, survival of crayfish exposed to the same infection doses at 10 weeks of age was not significantly affected by the zoospore treatment; all crayfish in the control and 1 zoospore mL−1 treatments survived, whilst 88 and 82% of those in the 10 and 100 zoospore mL−1 treatments survived. All juvenile crayfish that were tested (Fig. 2) were previously infected (as they were descended from infected females), although those that were exposed to zoospores exhibited significantly elevated infection levels (subset tested for A. astaci infection using qPCR; Kruskal–Wallis χ 2 = 9.7534, d.f. = 3, P = 0.021; Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Survival (a, b) and infection levels (c, d) of juvenile signal crayfish infected with A. astaci for 2 weeks. Infection treatments were sham-infection, 1, 10 and 100 zoospores mL−1; (a, c) 4 weeks after hatching; (b, d) 10 weeks after hatching. Note in (b) sham-infection treatment is identical to infection treatment 1 (grey/dashed grey). A subset of juvenile crayfish from each treatment was tested using qPCR, (c) sham-infection, 0 zoospores mL−1 (n = 5), 1 (n = 6), 10 (n = 5), 100 (n = 4); (d) 0 (n = 3), 1 (n = 3), 10 (n = 5), 100 (n = 6). See Appendix Table A1 for absolute values.

Adult crayfish behaviour

All crayfish in the ‘high-infection’ group displayed agent levels A4–A6 (median number of PFU = 23 050; n[A4] = 3; n[A5] = 13; n[A6] = 1), whilst all crayfish from the ‘low-infection’ group remained at very low (n[A2] = 9) to low (n[A3] = 6) infection levels (median number of PFU = 43). As such, for all analyses, crayfish behaviour was compared in terms of high and low infection.

Adults exposed to A. astaci zoospores (high-infection: 1000 zoospores mL−1) were significantly less likely to leave the water and spent on average 1.3% (range: 0–3.8%) of the 24 h period in the terrestrial arena compared to those in the low-infection group (sham-infected), which spent 3.5% (range: 0.3–9.2%) out of water (GAMLSS, ν, LRT = 5.671, P = 0.017). In terms of the other behaviours, there was no significant difference between crayfish from both the high- and low-infection groups, which spent 31.8 (s.d. ± 9.1%) of the time active, 47.2 ± 25% stationary outside of a shelter and 18.6 ± 26% in a shelter (Table 1; Appendix Table A2).

Crayfish from the high-infection group were also significantly less likely to mount a tail-flip response to tactile stimulation (GAMLSS, μ, LRT = 4.036, P = 0.045), where 35% of those in the high-infection group initiated a tail-flip response at least once compared to 75% of those from the low-infection group. Overall, though there was no significant difference between the two treatment groups, larger crayfish were more likely to display a threat response (GAMLSS, μ, LRT = 4.758, P = 0.029), spend less time in a shelter (GAMLSS, ν, LRT = 5.514, P = 0.019) and more time stationary outside of a shelter (GAMLSS, ν, LRT = 5.730, P = 0.017) compared to smaller crayfish.

Discussion

Here, we show that A. astaci can cause almost total mortality in juvenile signal crayfish at ecologically relevant zoospore densities (Strand et al., Reference Strand, Jussila, Viljamaa-Dirks, Kokko, Makkonen, Holst-Jensen, Viljugrein and Vrålstad2012, Reference Strand, Jussila, Johnsen, Viljamaa-Dirks, Edsman, Wiik-Nielsen, Viljugrein, Engdahl and Vrålstad2014), though larger, older individuals were less affected. Additionally, we show that a high A. astaci burden affects the behaviour of adult crayfish, making them almost half as likely to spend time on land and to escape from tactile stimulation compared to less infected individuals. The low-infection levels of our control crayfish did not differ from those frequently observed in P. leniusculus populations across Europe (Kozubíková et al., Reference Kozubíková, Vrålstad, Filipova and Petrusek2011; Filipová et al., Reference Filipová, Petrusek, Matasová, Delaunay and Grandjean2013; Tilmans et al., Reference Tilmans, Mrugała, Svoboda, Engelsma, Petie, Soes, Nutbeam-Tuffs, Oidtmann, Rossink and Petrusek2014) and in Japan (Mrugała et al., Reference Mrugała, Kawai, Kozubíková-Balcarová and Petrusek2017); although slightly higher infection levels (A2–A5) were reported in the UK (James et al., Reference James, Nutbeam-Tuffs, Cable, Mrugała, Viñuela-Rodriguez, Petrusek and Oidtmann2017). Thus, the high-infection group in our study represents the outbreak of a highly virulent strain. Whilst signal crayfish are a highly successful invasive species in Europe that continue to spread (Peay et al., Reference Peay, Holdich and Brickland2010; Holdich et al., Reference Holdich, James, Jackson and Peay2014; James et al., Reference James, Cable and Slater2014), the negative impacts of crayfish plague reported here, especially in terms of juvenile mortality, could have consequences for commercially harvested stocks by reducing recruitment and possibly resulting in population crashes. This also supports previous studies which have shown that commercially harvested signal crayfish populations can decline when A. astaci is present (Jussila et al., Reference Jussila, Tiitinen, Edsman, Kokko and Fotedar2016). Furthermore, these results add to growing evidence that A. astaci could play a more significant role in regulating invasive signal crayfish population dynamics than previously considered, which could play a role in determining invasion success (Jussila et al., Reference Jussila, Vrezec, Makkonen, Kortet and Canning-Clode2015).

In North American crayfish species, A. astaci can grow within the carapace, though constant host melanization of new hyphae prevents spore penetration to soft tissues (Unestam and Weiss, Reference Unestam and Weiss1970; Nyhlén and Unestam, Reference Nyhlén and Unestam1975; Cerenius et al., Reference Cerenius, Bangyeekhun, Keyser, Söderhäll and Söderhäll2003). In the current study, juvenile signal crayfish suffered extensive dose-dependent mortality when exposed to A. astaci zoospores around 4-weeks post-hatching. Slightly older (and therefore larger) crayfish, however, avoided this cost. Many juvenile crayfish studied here probably became infected rapidly after hatching, having acquired an infection from their mothers via horizontal transmission. Older and larger crayfish possibly have a better-developed immune response, capable of efficiently melanizing hyphae. It has been suggested that the immune response of juvenile crayfish to A. astaci infection is generally reduced compared to adults (Mrugała et al., Reference Mrugała, Veselý, Petrusek, Viljamaa-Dirks and Kouba2016), which seems to be the case in the current study. In other invertebrates too, younger individuals exhibit lower immune responses, for instance, snails showing greater susceptibility to schistosome parasites (Dikkeboom et al., Reference Dikkeboom, Knaap, Meuleman and Sminia1985). It has also been hypothesized, however, that juvenile crayfish could be less affected due to their higher moulting frequency compared to adults (Reynolds, Reference Reynolds and Holdich2002), allowing them to shed the growing hyphae and lower their A. astaci burden. Further research comparing the immunological capacity of juvenile and adult crayfish is required to confirm this. By the 10-week time-point, particularly susceptible individuals may have already succumbed to infection and therefore those used in the current experiment would have been more resistant to the pathogen. This appears unlikely though, since high levels of mortality were not observed in the communal holding tanks. Ecologically, the finding that relatively young crayfish hatchlings are highly susceptible to high doses of zoospores could have significant implications for signal crayfish recruitment and survival, especially in lentic environments, where zoospores are less likely to be washed away from the maternal crayfish.

Adult crayfish suffering from higher A. astaci infection levels during the current study exhibited a reduced tendency to leave the water. Although crayfish spend little time out of water in general, this finding suggests that populations of invasive signal crayfish with high burdens of A. astaci could be less likely to disperse overland to reach new aquatic habitats, a behavioural trait that can contribute to the spread of invasive crayfish (Grey and Jackson, Reference Grey and Jackson2012; Holdich et al., Reference Holdich, James, Jackson and Peay2014; Puky, Reference Puky2014; Ramalho and Anastácio, Reference Ramalho and Anastácio2014). Other invertebrates are less active when infected by parasites, potentially to avoid the associated fitness costs of dispersal. Flat back mud crabs (Eurypanopeus depressus) infected with rhizocephalans, for example, spend more time in shelter and are less active than uninfected crabs (Belgrad and Griffen, Reference Belgrad and Griffen2015), whilst sponge-dwelling snapping shrimp (Synalpheus elizabethae) infected by bopyrid isopods show 50% lower activity levels compared to uninfected individuals (McGrew and Hultgren, Reference McGrew and Hultgren2011). In other invertebrates, many studies have shown that parasites can influence dispersal, though these studies focus on direct host manipulation, which does not seem to be the case here as there is no evidence of A. astaci actively manipulating the host. In terms of native European crayfish management, a lower tendency of infected individuals to disperse overland might be beneficial, by reducing the transmission of A. astaci to new waterbodies.

Highly infected crayfish were also less likely to respond to tactile stimulation by retreating in a characteristic ‘tail-flip’ manner. This reduced ability to escape could lead to increased predation of highly infected crayfish. A. astaci zoospores largely penetrate soft abdominal tissue (Vrålstad et al., Reference Vrålstad, Knutsen, Tengs and Holst-Jensen2009), and it is possible that the reduced escape response is directly due to the general pathological effects of the parasite (Unestam and Weiss, Reference Unestam and Weiss1970). Other parasites, such as Thelohania contejeani, also penetrate crayfish tissues, parasitizing the muscles and reducing the ability of crayfish to predate and feed (Haddaway et al., Reference Haddaway, Wilcox, Heptonstall, Griffiths, Mortimer, Christmas and Dunn2012). It is also possible that highly infected crayfish exhibit a reduced tendency to move on land to reduce the risk of predation. In the same way, crustaceans become less active and tend to stay in a refuge when moulting, during which they are vulnerable to predators and largely unable to escape (Thomas, Reference Thomas1965; Cromarty et al., Reference Cromarty, Mello and Kass-Simon2000).

The crayfish used in the current study were from a population previously considered to be below the detection limit [n = 30 tested by James et al. (Reference James, Nutbeam-Tuffs, Cable, Mrugała, Viñuela-Rodriguez, Petrusek and Oidtmann2017) exhibited A0–A1 levels]. However, given that infection levels A2–A3 were found both among crayfish tested before the experiment began, as well as among those in the group not exposed to zoospores, it is evident that this population has either become infected since 2014, that a previously very low prevalence of A. astaci has since increased, or that crayfish present with A2–A3 infection levels in 2014 were just not trapped by James et al. (Reference James, Nutbeam-Tuffs, Cable, Mrugała, Viñuela-Rodriguez, Petrusek and Oidtmann2017). Signal crayfish in Europe are generally associated with the group B strain of A. astaci (see Huang et al., Reference Huang, Cerenius and Söderhäll1994; Grandjean et al., Reference Grandjean, Vrålstad, Diéguez-Uribeondo, Jelić, Mangombi, Delaunay, Filipová, Rezinciuc, Kozubíková-Balcarová, Guyonnet, Viljamaa-Dirks and Petrusek2014), which has also been found infecting another Welsh population, approximately 45 miles away from the population studied here (James et al., Reference James, Nutbeam-Tuffs, Cable, Mrugała, Viñuela-Rodriguez, Petrusek and Oidtmann2017). Although not confirmed, the crayfish used in the current study were most likely initially infected with a group B strain and subsequently exposed to another strain from the same group. It is also possible that the tested crayfish were locally adapted to their original A. astaci infection (Gruber et al., Reference Gruber, Kortet, Vainikka, Hyvärinen, Rantala, Pikkarainen, Jussila, Makkonen, Kokko and Hirvonen2014; Jussila et al., Reference Jussila, Vrezec, Makkonen, Kortet and Canning-Clode2015), and the observed behavioural effects resulted from the exposure to the new A. astaci strain. As observed by Jussila et al. (Reference Jussila, Kokko, Kortet and Makkonen2013), even assumed identical A. astaci strains may differently affect their crayfish hosts; therefore, the experimental crayfish in the current study likely dealt with multiple infections of closely related A. astaci strains. Further research is required, to explicitly compare the behaviour and survival of infected and uninfected signal crayfish, as well as investigate the effects of different A. astaci strains (both in single and multiple infections) on the behaviour and survival of infected crayfish.

In summary, we have shown that high levels of A. astaci cause severe mortality in young juveniles and affect the behaviour of adult signal crayfish. Mounting evidence suggests that signal crayfish may succumb to A. astaci more often than previously considered, which could be having an impact on commercially harvested populations (Aydin et al., Reference Aydin, Kokko, Makkonen, Kortet, Kukkonen and Jussila2014; Edsman et al., Reference Edsman, Nyström, Sandström, Stenberg, Kokko, Tiitinen, Makkonen and Jussila2015). The crayfish exposed to zoospores in the current study displayed relatively high plague agent levels of A4–A6 (A7 being the highest level of infection; Vrålstad et al., Reference Vrålstad, Knutsen, Tengs and Holst-Jensen2009). A longer period of infection, or higher infection dose, may induce further behavioural responses beyond those reported here, and in some cases even cause mortality as observed by Aydin et al. (Reference Aydin, Kokko, Makkonen, Kortet, Kukkonen and Jussila2014), where signal crayfish were exposed to 10 000 zoospores mL−1. Female crayfish suffering from ESS carry far fewer fertilized eggs than uninfected females (Edsman et al., Reference Edsman, Nyström, Sandström, Stenberg, Kokko, Tiitinen, Makkonen and Jussila2015) which, coupled with the high juvenile mortality documented in the current study, could drastically reduce juvenile recruitment and result in population crashes. Similarly, crayfish plague could also have implications for the further spread of signal crayfish by affecting population dynamics, though this species has already successfully colonized large parts of Europe (Holdich et al., Reference Holdich, James, Jackson and Peay2014) and so the ecological impact may be negligible. Anecdotally, it was assumed that most North American crayfish are infected with A. astaci, though molecular methods have demonstrated that it is less prevalent than once thought. In France, for example, just over half of the signal crayfish populations tested were found to be positive for crayfish plague (Filipová et al., Reference Filipová, Petrusek, Matasová, Delaunay and Grandjean2013), and in the UK the prevalence was 56.5% (James et al., Reference James, Nutbeam-Tuffs, Cable, Mrugała, Viñuela-Rodriguez, Petrusek and Oidtmann2017). It is possible, therefore, that the population dynamics of uninfected invasive populations may be affected when infected individuals are translocated and introduced.

Financial support

This project was funded by Coleg Cymraeg Cenedlaethol (JRT) and the Welsh Government and Higher Education Funding Council for Wales through the Sêr Cymru National Research Network for Low Carbon, Energy and the Environment (NRN-LCEE) AquaWales project.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional guides on the care and use of laboratory animals.

Appendix

Table A1. Number of PFU for subset of juvenile crayfish tested for A. astaci

Table A2. Time (in s) and proportion of time that crayfish spent engaged in behaviours over a 24 h period