‘A crazy clutter of the mediaeval, medical mind’. Thus reads the film director Ken Russell’s script for a scene that occurs roughly halfway through his 1971 cult feature The Devils. It goes on: ‘horses’ hooves, human bones, the foetus of a whale, retorts, jars … and dominating everything, the suspended crocodile under which evidence against GRANDIER is being discussed’.Footnote 1 The crocodile did not, regrettably, survive the cut of this scene, but the room’s anachronistic mélange of medievalized artefacts, placed incongruously side by side, serves as a metaphor: not simply for The Devils, but for a more general and pervasive kind of historical imaginary (and/or historical) presence that is prevalent across film, television, music and other media besides. While often engaged with what it means to be ‘historically informed’, that presence is frequently – if not uniformly – marked by contradiction and anachronism; it is at authenticity’s outer reaches that the creative past most effectively speaks to the present.

The Devils has experienced something of a revival in its critical fortunes in recent years, fuelled in part by a renewed interest in Russell himself – a man now recognized as a major player in what the film critic Raymond Durgnat has described as a fantasist or antirealist ‘phantasmagorical’ British cinema tradition.Footnote 2 But while a great deal of the growing literature on Russell has shown considerable interest in this film especially, unpacking the minutiae of its production, release and reception, there has been no critical investigation of the significant musical collaborations which are both heard and felt in the film.Footnote 3 Indeed, it was British music’s own enfant terrible Peter Maxwell Davies who composed the score for The Devils, and an interest in reanimating the past in bold ways is one trait that Davies and Russell shared in their respective careers. This was one of only two film scores that Davies composed (the other was for another Russell film, The Boy Friend, in the same year), and his music in The Devils is routinely juxtaposed with so-called period-appropriate, usually diegetic (though mostly off-screen), performances from the early-music popularizer David Munrow and the Early Music Consort of London. It is one of the aims of this article, then, to explore for the first time aspects of Davies’s film work, as well as some of the circumstances and details of his (and Munrow’s) little-known and short-lived association with Russell, which ended with an aborted collaboration on the première of Davies’s opera Taverner in 1972.Footnote 4

In this article, however, it is ‘medievalism’ – that is to say, the ‘semantic site for the fusion of creative and scholarly engagement with the past’ as something distinct from a learned, scientistic or philological form of the study of the Middle Ages – that I want to foreground first and foremost.Footnote 5 In particular, I am interested in how we might start to rethink and better understand a strain of modernist medievalism in post-war British new music through this unusual (but by no means incongruous, and perhaps even exemplary) case of a little-appreciated score by a composer of significant national standing. Indeed, in the improbable instance of a cult film, Davies’s cerebral form of medievalism is newly inflected by the possibility of alternative cinematic reading strategies that celebrate bad taste and excess in chronologically circuitous contexts that connect disparate discursive spaces of art (both ‘high’ and ‘low’) on stage, on the screen and in the concert hall.

Modernist medievalism, in so far as it is characteristic of Davies’s work, came close to achieving a mass audience through The Devils. Footnote 6 As well as better accounting for a one-of-a-kind film score, ill-fitted to established narratives of post-war new music, this article proposes to go further. Indeed, it contends that it is in medievalism’s playful treatment of such concepts as continuity and authenticity, humour, primitivism, spectacle and co-disciplinarity – spliced together here by an aesthetic of noisy heretical excess – that we may find more effective routes for understanding the role of a persistent past in the music of a resolutely modernist present.Footnote 7

Medievalism in The Devils, and in British music

The Devils – based on the Aldous Huxley novel The Devils of Loudun (1952) – is set in the seventeenth century, in a France still reeling from its wars of religion. It epitomizes many of the traits of a timely cinematic medievalism, with (as we shall see) garish costumes and castle walls, as well as religious superstition and violence, to say nothing of the shawm-dominated, raspy, diegetic music-making that takes place throughout. It tells, then, the partially true story of the mass possession of an entire convent of Ursuline nuns in the French medieval fortress town of Loudun, triggered (in this version of events) by the sexual obsession of one Sister Jeanne (Vanessa Redgrave) with the rebel Jesuit priest Urbain Grandier (Oliver Reed). This possession becomes the pretext for a cruel exorcism of Jeanne by a team of inquisitors working under orders from Cardinal Richelieu and, ultimately, the politically motivated trial and execution of Grandier.

A product of its time, the film draws heavily upon John Whiting’s 1961 play The Devils, itself adapted from Huxley’s novel. The film retains much that is theatrical in style – this is particularly obvious in the actors’ performances, which are so often histrionic, shrieking and loud. Furthermore, it follows by only a couple of years Krzysztof Penderecki’s similarly expressionistic opera on the same story, Die Teufel von Loudun (1969).Footnote 8 Visually, The Devils is dominated by a vast set designed by the young Derek Jarman: this was his first major film work, and the largest set that Pinewood Studios had seen. It depicts Loudun’s long-destroyed and medieval-walled city through the lens of an early twentieth-century kind of architectural modernism (the viewer may recall Fritz Lang’s Metropolis), as can be seen in the imposing white geometries of Loudun’s walls (see Figure 1). This architecture, and the kind of deeply embedded structural anachronism it embodies, runs deep in the film’s holistic sonic-visual textures.

Figure 1 The city of Loudun’s modernist-inspired medieval architecture. Sets designed by Derek Jarman.

Of course, The Devils is set not in the Middle Ages, but in the early seventeenth century. However, as in other works, such as Davies’s opera Taverner, it requires no great leap of the imagination to describe the stylized early modern or Renaissance in The Devils, as well as the musical-expressionist idiom that these works share (complete with references to ‘early music’), as potent instances of sonic medievalism or its ambiguously defined partner, neo-medievalism.Footnote 9 Indeed, it is the porousness of the medieval period – its historiographical fuzziness – that is the locus of its imaginative power. Medievalism has functioned since its nineteenth-century origins through the evocation and splicing together of a ‘non-contiguous’ and distant past with the present.Footnote 10 Popular and fantasy medievalism in literature, opera or film invariably employs the distant past as a stage on which the tensions of the present are played out and where, often, futures can be imagined – distance and alterity being key. So it is, then, that medievalism trades on an imaginary pre-modernity broadly defined. In short, it is a site of contested meanings, encompassing a range of stylized temporal discontinuities.Footnote 11

That medievalism is a slippery and even contradictory field also forms something of a rallying cry for scholars who believe strongly in the ongoing vitalism of the past and the lived intersection of scholarly and creative practice – with all the challenges this poses to already vexed notions of authenticity. On the basis of a discussion of the seeming strangeness of the architecture of the American university campus, for example (complete with often Disney-level Gothic revivalism), Daniel Lukes has declared evocatively that medievalism (or neo-medievalism) ‘looks to the future, unravels time and disrupts teleology, makes new the old, celebrates the impossible, makes mockeries of truth […] feels ashamed for its lack of respect for the historical Middle Ages, and distracts and enchants with improbably absurd assemblages’.Footnote 12

Lukes’s colourful exaltation should ring true for anyone familiar with the carnivalesque atmosphere into which The Devils descends during its closing tumultuous execution scene, where Grandier is publicly dragged to and burnt at the stake amid grotesque scenes (the walls of the city are destroyed at the end) – even if it does so as an inversion of Lukes’s implied utopia. It is a sequence in which time and setting dissolve into something neither strictly here nor there, neither past nor future, but wholly cruel, visceral and now. This image is conjured sonically in an ever-escalating musical mess that is entirely isorhythmic (governed by a transforming and cyclical cantus firmus), contrapuntal (or polyphonic) and dissonant. A production list of audio in the film which was compiled at the time (edited in Table 1) recalls the film’s circular sonic chronologies: smatterings of ‘Dies irae’ and ‘Sanctus’, alongside dovetailing musical sequences both ‘authentic’ (Munrow’s passages here include selections from composers like Michael Praetorius and Claude Gervaise, among others) and new (‘P. Maxwell Davies’). If the film’s central acts find some semblance of stability, it is at the beginning and the end that the names of Munrow (misspelt ‘Monroe’) and Davies (old and new, respectively, you might argue) – and thus musical time itself – become enmeshed, dissolute and out of sync.

TABLE 1 PRODUCTION LIST OF AUDIO IN THE DEVILS

| Duration | Title of composition | Composer/author/arranger |

|---|---|---|

| 1.03 | Introduction to King’s Dance | D. Monroe |

| 1.56 | King’s Dance | D. Monroe |

| 1.08 | Titles | P. Maxwell Davies |

| 2.48 | Dies irae | D. Monroe |

| 3.39 | Dies irae | D. Monroe |

| 0.50 | Grandier’s House | P. Maxwell Davies |

| 0.26 | Plague Death Dance | P. Maxwell Davies |

| 1.24 | Interlude – Grandier and Mlle De Brou | P. Maxwell Davies |

| 1.40 | Plague Death Dance | P. Maxwell Davies |

| 0.25 | Plague Death Dance | P. Maxwell Davies |

| 2.52 | Plainsong Sanctus | P. Maxwell Davies |

| 1.30 | Jeanne’s Second Vision | P. Maxwell Davies |

| 0.18 | Street Music | D. Monroe |

| 0.13 | Grounds of the King’s Palace | D. Monroe |

| 0.05 | Grounds of the King’s Palace | D. Monroe |

| 0.08 | Grounds of the King’s Palace | D. Monroe |

| 0.08 | Grounds of the King’s Palace | D. Monroe |

| 0.26 | Grounds of the King’s Palace | D. Monroe |

| 0.10 | Street Music | D. Monroe |

| 0.20 | Street Music | D. Monroe |

| 2.58 | Wedding of Père Grandier and Mlle De Brou | P. Maxwell Davies |

| 0.31 | Humming Nuns | P. Maxwell Davies |

| 0.48 | Mock marriage in convent | P. Maxwell Davies |

| 1.00 | Fight – Mlle De Brou and Sister Jeanne | P. Maxwell Davies |

| 0.15 | Help me, Father | P. Maxwell Davies |

| 2.14 | Cue 28 | P. Maxwell Davies |

| 2.27 | De Brou – Grandier | P. Maxwell Davies |

| 1.22 | Grandier narrates letter | P. Maxwell Davies |

| 0.23 | Fanfare no. 1 | P. Maxwell Davies |

| 0.08 | Exorcism music | P. Maxwell Davies |

| 0.25 | Jeanne’s supposed liberation | P. Maxwell Davies |

| 0.17 | Fanfare no. 2 | P. Maxwell Davies |

| 0.40 | Organ only | P. Maxwell Davies |

| 0.18 | Sign of the Devil | P. Maxwell Davies |

| 1.00 | Condemn[n]ing Grandier | P. Maxwell Davies |

| 1.52 | Grandier’s House smashed | D. Monroe |

| 0.45 | Street song 1 | D. Monroe |

| 0.55 | Street Music | P. Maxwell Davies |

| 0.39 | Street song 2 | P. Maxwell Davies |

| 0.40 | Grandier Dragged to stake | D. Monroe |

| 1.10 | Execution of Grandier | P. Maxwell Davies |

| 0.12 | Grandier Dragged to stake | D. Monroe |

| 0.12 | Grandier Dragged to stake | D. Monroe |

| 0.20 | Played simultaneously with Execution of Grandier | P. Maxwell Davies |

| 0.15 | Execution of Grandier | P. Maxwell Davies |

| 0.13 | Grandier Dragged to stake | D. Monroe |

| 4.49 | Execution of Grandier | P. Maxwell Davies |

| 3.55 | End Title | P. Maxwell Davies |

Source: London, Royal Academy of Music, DM/5/3.

As suggested by the scholar Jonathan Hsy, it is, then, precisely in ‘medievalism’s conspicuous concurrence of temporalities’ that a special space is created for ‘co-disciplinarity’ in which ‘an individual or a group of people [… can] test the very conventions of academic disciplines and […] experiment across diverse modes of artistic production’.Footnote 13 Again, this rings true not simply for work in medievalism studies itself (which cuts across any number of academic disciplines: literary criticism, art history, film theory and so on), but for products of medievalism including that which is under investigation here. Indeed, however much medievalism can come to reveal, The Devils is a complex constellation blurring much that is ossified in our cultural economy: in the first instance, combining Russell’s pop pedigree and transgressive aesthetic with the avant-garde Davies (incorporating, stylistically speaking, elements from his Artaudian music theatre and earlier musical expressionism), alongside Munrow’s own ‘historically informed’ (but heavily stylized) early-music recreations and even the film’s set designer Jarman’s medievalized homage to early twentieth-century modernist futures.Footnote 14 It is through the contradictory lens of the distant past that the film’s cross and co-disciplinary innovations might best be recognized, demonstrating what Hsy describes as the ‘sheer range of venues through which inventive medievalism flows, generating new artistic media in an ever-shifting present’.Footnote 15

The field of medievalism studies has only recently begun to show its influence in musicology. Its capacity to bring into collision divergent musical discourses and to push critical enquiry beyond ‘chronological and geographical boundaries’ is, however, already evident.Footnote 16 In the field of new music, especially, there is much to say. Take, for instance, Emma Dillon’s analysis of George Benjamin’s hugely successful opera Written on Skin (2012).Footnote 17 Dillon draws specifically on the works of two leading scholars of medievalism, Caroline Dinshaw and Louise D’Arcens, to call attention to the productive potential of the co-presence of multiple and conflicting temporalities in a work: the ‘asynchronous’ or ‘out of sync’ in artefacts of medievalism (also evoked in the Lukes quotation above).Footnote 18 She also refers to the making fluid of boundaries between the scholarly (or ‘discovered’) and the ‘made’ (fictional or creative) medieval, and the creative intersection that this fosters.Footnote 19 The resultant ‘new modality’ – ‘in which studies of the medieval past “discovered” and “made” are juxtaposed, and integrated’ – might fruitfully be applied not only to music in the opera house but also to absolute music more generally.

Benjamin’s medievalism – overt or disguised in compositional technical dress, ‘discovered’ or ‘made’, or a combination or juxtaposition thereof – might be viewed in the context of a post-war lineage beginning with Davies. Indeed, while Davies’s ‘Manchester School’ milieu has often been said to have brought a kind of Continental high modernism to British shores in the 1950s, Jonathan Cross briefly notes in relation to Harrison Birtwistle that ‘neo-medievalism’ was a ‘prominent feature’ of that composer’s music and an ‘interest that was also to be shared at Manchester by Peter Maxwell Davies and Alexander Goehr’.Footnote 20 British contemporary music, then, has indeed often been characterized by its playful relationship with a (broadly conceived) medieval history:Footnote 21 it is, you might say, one of its defining qualities. What this means in a music-analytical context has been the subject of some discussion, its presence discerned by close analysis of (say) embedded plainchant quotation as note row (a technique I investigate further below). But its meaning and implications for the situating of ivory-tower composers within broader cultural currents have largely been taken for granted. Indeed, as Anne Stone notes, by the late 1960s British modernism was ‘conditioned by the imagined medieval, and the sound of the medieval was inflected with 1960s modernity’.Footnote 22 She draws attention, in particular, to some of the interconnections between the contemporary music scene and the early-music revival – interconnections that are discernible across popular music (as in the folk-music revival) and in popular film and television too. Viewed in this way, medievalism is a vector through which to recognize the changing terrain of the popular historical perception conditioned simultaneously by scholarly and imaginative work in the field. ‘Serious’ music, as evidenced in The Devils, has much to contribute to that story, and to its destabilizing presence in post-war modernity.

The Devils: paracinema and its reception

While it was intended as something of a ‘serious’ and ‘historically informed’ study of power and corruption, The Devils is today mostly remembered for scenes of gruesome torture and dubious medical practice. (Russell was, despite the implied critique in the film, a devout Roman Catholic.) Particularly disturbing for its critics was an extended passage, promptly cut, that has come to be known enigmatically as the ‘Rape of Christ’. In this bacchanalian scene, scores of crazed and naked nuns molest religious paraphernalia, watched over by (it is implied) a masturbating priest, and they do so while accompanied by frenetic camerawork and an increasingly cacophonous soundtrack: a noisy and improvisatory mélange dominated by a percussive ensemble including police whistles, a ‘knife on plate’, a thunder sheet and more besides.Footnote 23 If we take this scene as a microcosm of the film as a whole (and to do so would not be unjustified), The Devils is clearly a stylistically abrasive work that is hard to classify, a reputation reinforced by its having a contested legacy and reception that has relegated it for much of its history to the rarefied status of ‘cult film’ and even a kind of ‘video nasty’.Footnote 24 All the while, it was marketed as something of a prestige ‘authentic’ historical feature, despite an expressionistic visual and sonic style that foregrounds excess, entirely in keeping with Russell’s authorial signature. The score is fully imbricated in this contradiction. At once entirely legitimizing, it is the work of someone whom the general public may have seen as a prestige composer well versed in early-music techniques and sources, but simultaneously theatrically avant-garde: equally repugnant, sonically speaking, to a mainstream audience.

In a now highly mythologized account of runaway censorship and near public hysteria, and after a considerable tussle with both the British Board of Film Classification and the film’s own studio, The Devils would receive a rare X certificate.Footnote 25 This was a response that came about, as Julian Petley has demonstrated, by way of a complex and interrelated, even artificial, public outcry conditioned by the seeming convergence of moralizing critics, local councils and socially conservative grassroots organizations (including Mary Whitehouse’s Nationwide Festival of Light), many of which even went so far as to lie about the film’s content while it was still in production.Footnote 26 It would be subjected to further cuts for audiences in the USA (where it was a commercial failure), and that heavily edited version went on to be released for home video in Britain and elsewhere.Footnote 27

The Devils is a complex text that exists in multiple forms – its censored original release is not ‘authentic’, and the real deal is still being reconstructed. However, its reputation for shock and depravity is far in excess of anything that is really there in the film, despite being also the principal reason why it is sought by cinephiles today. All the same, the conditions of its suppression, its ambitious narrative and visual scope, and the evolving credibility of its director have inspired a counter-narrative arguing for its legitimization by inclusion in the canon.

The Devils, then, has all the ingredients of a cult classic. As a result, it occupies a creative-imaginary space not readily suited to the seemingly inescapable binary of prestige (or ‘art’) and popular cinema. That it has a score from a renowned ‘avant-gardist’ also adds to this mystique, though I might argue that that is to mishear the score itself. To this extent, then, it has much in common, I suggest, with what has long been referred to in film theory circles as ‘paracinema’ (and with its cognate aesthetics of ‘trash’). Indeed, The Devils clearly challenged an ostensibly conservative establishment’s ideal of what constitutes ‘good taste’, a term that is consistently (perhaps even lazily) invoked in the mainstream discussion of Russell’s legacy.Footnote 28 ‘Good taste’, however, is also a hegemonic concept long recognized by Pierre Bourdieu as the spurious tool of a taste-making sociocultural elite; and, as Bourdieu states: ‘Tastes are perhaps first and foremost distastes, disgust provoked by horror or visceral intolerance of the tastes of others.’Footnote 29 In this view, ‘good taste’ functions not in the affirmative sense (so as to delineate, say, excellence), but instead to maintain something altogether more unequal, and to exclude any challenge to an oligarchic cultural order. No wonder, then, that a newer breed of scholarship concerned with Russell’s legacy shies away from the label now – and to this end, mention of Davies as composer for this film is principally employed for his legitimizing status as a serious composer of ‘art music’ rather than a co-conspirator in cultish trash cinema.

Building from this theoretical foundation, the influential notion of ‘good taste’ has become the basis for the study of ‘paracinema’ – an elastic concept intended to describe a huge range of ‘seemingly unrelated’ and ‘bad taste’ film subgenres (from exploitation movies of all kinds, obscure documentary, softcore pornography and more).Footnote 30 Paracinema is less a subgenre of film than it is a method of reading, though; or, to quote Jeffrey Sconce, a ‘counter aesthetic turned subcultural sensibility devoted to all manner of cultural detritus’.Footnote 31 Poised at the hinterlands of both ‘excess’ and ‘style’, paracinematic readings encourage a non-diegetic, detached appreciation of the ‘whole film’ where ‘unconvincing special effects, blatant anachronism, or histrionic acting’ bring the profilmic and extratextual into dialogue with traditional narrative verisimilitude so as to encourage distanced, critical and heterogenic readings.Footnote 32

The paracinematic canon also reveals (Joan Hawkins has suggested) something generally overlooked in the cultural analysis of art cinema, namely ‘the degree to which high culture trades on the same images, tropes, and themes that characterize low culture’.Footnote 33 A paracinematic lens reveals that the apparently impermeable line that preserves social structures’ corollary to the high and low divide in art is, in fact, a porous, if not outright moveable, one. Therein, too, lies the discursive power of the ‘paracinema’ label which is also relevant to this article: as Hawkins has also observed of the mail-order video market catalogues in which esoteric and cult film canons have historically been circulated (such catalogues freely list works of ‘art’ cinema alongside the ‘low end’ of body horror and cult trash), paracinema perspectives can do much to destabilize binary or hierarchic assumptions of taste.Footnote 34

The Devils, suffice it to say, does hold something of a paracinema pedigree on its own, and without my interpretative intervention, it operates (whether intentionally or not) at the productive fissure of art and trash. Indeed, it is mentioned (along with three other Russell features) in The Psychotronic Encyclopedia of Film (something of a bible for the subject), and the reference book Horror Films of the 1970s describes it as a ‘spiky, controversial, even inflammatory film’ that ‘fits in with the witch-hunt tradition of such gory 1970s films as Mark of the Devils (1972)’.Footnote 35 The ‘witch hunt’ obsession and folk horror associations indicate, also, a special place for medievalism within traditions of trash cinema. And while it would not be entirely fitting to throw Russell wholly into this category (such responses to the film run counter to the symbolist or mannerist reading more common today),Footnote 36 explicit authorial intent aside, a film as sonically and visually striking as this deserves correspondingly heterogeneous perspectives. Equally deserving of this is Davies’s soundtrack, which, as a kind of musical cognate for the visual action on screen, also trades in a similar aesthetics of noisy and flamboyant excess bordering on ‘trash’, albeit in a language or idiom mostly preserved, critically speaking, for its association with a concert-hall (or, indeed, music-theatre) ‘art music’ tradition.

Blind alleys and cacophonies: Davies’s medieval theologies

Davies’s work for The Devils has received little attention in the scholarship on his music. Indeed, the politics of a serious composer stepping down from the ivory tower to score for a popular film – one with as chequered a reception history as this one – is tricky, especially where commentators may be inclined to maintain for the composer a position that is in some way privileged. That The Devils has gone on to find a renewed profile on that strange but productive cusp between cult horror and underappreciated ‘art’ film (of national significance) is a further complicating, though no doubt promising, vector. Comparisons should come as no surprise: Davies, too, was an artist who defied expectation.

Consider, then, the brief account of his collaboration with Russell in Mike Seabrook’s understandably fawning Davies biography. For a start, any substantive details of the film itself are missed. Seabrook comments on Davies’s enthusiastic acceptance following an ‘approach’ from Russell in 1971 and the direction of travel here is made very clear.Footnote 37 And, although Davies would admit to finding it an ‘interesting novelty to work with film people’, he would, according to Seabrook, ‘on the whole’ see it as an ‘interlude [and] just that […] a bit of a blind alley, out of the mainstream of his development as a composer, and having no influence on it’.Footnote 38

There is, though, more to this score (which was exceptional for its time) than such an account would suggest, despite what the composer himself might have said. It is always, in any case, necessary to go far beyond the image- and reputation-sustaining activities of artists – which are, in fact, an extension of their creative activities.Footnote 39 As Mervyn Cooke – in an example of retrospective critical recognition that is rare today – has noted of the score, it remains (perhaps owing to a ‘steady influx of jazz and pop scoring’) a ‘notable exception’ in which ‘extreme nondiegetic modernism’ (consisting of ‘disturbing expressionism’ with ‘avant garde twitterings’ and ‘grotesque parody’) proves exceptionally well suited to Russell’s ‘strong visual imagery’.Footnote 40

In his review of the essay collection Peter Maxwell Davies Studies (a significant contribution that makes no mention of The Devils),Footnote 41 Christopher Fox briefly reads in Davies’s Russell encounter a kind of complicated (even liminal) moment for Davies, suggesting that this score was something more than merely the first thing he composed in his Orkney composition retreat:Footnote 42

It is also clear that it was the crazy parodies and Artaudian display of these works, not transformations of pitch […] which had taken Davies to the fringes of popular consciousness. Frenzied fox-trotting and absurdist theatricality brought Davies to the attention of Ken Russell […] it is perhaps not too far-fetched to suggest that Davies’s subsequent move to the Orkney islands was an attempt to put clear blue water between him and a success at odds with his most fundamental concerns.Footnote 43

Referring, of course, to the anarchic and extravagant music-theatre works of the period (1969’s Vesalii icones, Eight Songs for a Mad King and so on), Fox sees in The Devils –suffused, as Davies’s work then was, with timely ‘counter cultural energies’ – the culmination of what Philip Rupprecht has described elsewhere as Davies’s bursting out (publicly).Footnote 44 In relation to this, his Orkney-based retreat to a ‘new form of classicism’ seems, symbolically at least, to be a response or rebuttal.Footnote 45 This, then, accounts in some way for the disproportionate attention paid to his earliest works, and the score of The Devils got lost to criticism precisely because it fell in that moment between phases. It does not, apparently, have an obvious home in the now reified story of the composer: one that sees him at one end of the spectrum as the enfant terrible of British new music, and at the other, as the Master of the Queen’s Music.

Davies and Russell’s relationship should (with the help of some wishful thinking) have reached its zenith just less than a year after the release of The Devils, with the Russell-directed première of Davies’s first opera, Taverner, composed between 1956 and 1972, whose resemblance and overlap with The Devils – stylistically, chronologically, even biographically – is striking. Their first association had been the Unicorn Records releases of Davies’s groundbreaking music-theatre works Eight Songs for a Mad King and Vesalii icones, both recorded in 1970, which Russell financed and promoted.Footnote 46 Davies’s music theatre had struck a nerve with Russell (a very public rising ‘talent’ at that time),Footnote 47 and with hindsight this should come as no surprise, given Russell’s own growing reputation as a ‘British Fellini’.Footnote 48 That these recordings also were part of a concerted effort to bring the ‘avant-garde’ to popular audiences also seems likely, and Davies’s potential crossover appeal is detailed in an article in The Guardian in 1971.Footnote 49

Davies at the same time wrote the score for The Devils (performed, in the end, by his ensemble the Fires of London) as well as Russell’s film adaptation of the musical The Boy Friend, for which he composed a suite of popular song-style foxtrots (something of an obsession for Davies) as well as song arrangements from the musical on which it was based. Seabrook’s biography considers these arrangements in particular as something ‘Max thoroughly enjoyed’ (even if his ‘brief sideline as a composer of film music’ was to end because it was ‘back-water’).Footnote 50

In an interview recorded as part of the documentary Director of The Devils (1971), Russell boasted about their relationship and what would have been his forthcoming Royal Opera House directorial début with Davies’s opera Taverner. He noted the similarities between the two works thus:

It’s on a religious subject very similar to The Devils, it is about corruption of religion, the corruption of a human being, and when the forces of religion get to work on him […] so when it came around to finding a composer for this film there was only one possible choice.Footnote 51

Despite his professed confidence in the work and his role in realizing it, Russell did not in the end direct Taverner. It was reported shortly afterwards, also in The Guardian, that Russell had withdrawn from the production, ‘effectively ending […] one of the most provocative and stimulating artistic relationships of its time’.Footnote 52 The same article says that Russell had heard a tape recording of Taverner played on the piano and declared there and then that it was not enough to work with.Footnote 53 Davies is quoted as saying that their partnership had ended amicably (though Russell’s lack of a response was noted). He was then still planning to score for a further Russell feature, The Savage Messiah (a biopic of the modernist sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska), but this never came to pass either.

We can never know what a Russell-directed Taverner might have looked like, and how this unrealized and potentially landmark version of a work mostly recognized as important only for those with an interest in Davies and his compositional milieu might (or might not) have changed the course of both careers in question – and, perhaps fancifully, that of British new music and film more broadly. In lieu of this, it suffices to say that The Devils and Taverner share much, visually and sonically, as well as dramatically, and comparison here is apt: they stand as comparable manifestations of a challenging form of modern, or avant-garde, medievalism.Footnote 54 Taverner, too, for example, featured Munrow’s Early Music Consort of London, as intended, at its Royal Opera House première, playing on this occasion newly composed, period-pastiche music off stage. Both likewise dramatize similar religious themes (heretical to some) – chiefly forms of religious and authoritarian corruption – and conclude with public executions. Davies’s fictional treatment of the historical composer Taverner has him undergoing a negative transformation from Catholic composer (of ‘Popish-Ditties’) to a ruthless Protestant enforcer; in The Devils, however, Grandier stays resolute in the face of his own mistreatment.

And there are visual parallels too: Taverner premièred with a set designed by Ralph Koltai (1924–2018), whose giant metallic and wiry seesaw structure and ‘wheel of fortune’Footnote 55 recalls, if not by way of a direct copy, the aforementioned early twentieth-century modernism of Jarman’s own huge set.Footnote 56 It is striking in both The Devils and Taverner that such overtly modernistic and anachronistic settings should be juxtaposed against a more typical ‘authentic’ medievalized wardrobe. The result in both cases resembles a kind of (retrospectively, borderline comic) collision between a strict modernist expressionism and (now, at least) campy BBC period costume drama wholly representative of a shared epoch.

Like The Devils, Taverner had a mixed reception (the New York Times described it as offering a ‘pretty forbidding face to the average opera goer’),Footnote 57 and it was appreciated principally as a piece of music, if not as a great work of drama (the fact that Davies wrote and compiled his own libretto was cited as a reason for this).Footnote 58 This tension was, perhaps, expressed most neatly at the time by Joseph Kerman, who regarded the music very highly but figured that the dramaturgy was all wrong: the character of Taverner, he explained, felt like a ‘straw man […] a caricature out of a counter-reformist tract’, his transition not properly prepared or earned.Footnote 59 There is something in Taverner’s coarse and unrelenting style, and in its seemingly nihilistic outlook, which challenged a certain kind of operatic good taste too. While its score was accepted at face value by an audience no doubt anticipating something ‘difficult’ (it being, after all, an opera from a foremost modern composer), its didactic dramatic logic was ultimately derived from (and perhaps better suited to) a more ‘underground’ avant-garde music-theatre context (with all the associations with cultural capital that this implies), its post-Brechtian commitment to alienation and anti-narrative being less appealing to opera-house audiences.Footnote 60 Taverner has retained an important place in post-war British music, if primarily as a kind of metonym for well over a decade’s work by the composer (leaving its traces across several Taverner-inspired Davies compositions across all of the 1960s). But it is only in recent years that the theatrical achievements of the opera have been better appreciated and even rehabilitated.Footnote 61

In an article discussing the seemingly heretical content of Davies’s operatic works, Majel Connery has noted that he, like Russell, could be ‘confrontational, boundary-renouncing, provocative, and sometimes bizarre’.Footnote 62 Her reading of Taverner here, partially framed as a response to Kerman’s criticism that the character of Taverner’s transition in the opera makes little ‘dramatic sense’, suggests an idiosyncratic apophatic or negative theological underpinning, more sympathetic to its Christian subject matter than it might at first seem – or than Davies’s own avowed atheism might admit. Her reading is a holistic and intertextual (or transtextual) one, which considers Taverner as well as the failure of its own internal morality play – in conjunction with Eight Songs for a Mad King and the later Resurrection – as dramatizing the loss of voice (the excessive object of opera) so as to ‘stage (and, in so doing, inflect as theatrical) the terrifying experience of a lack of god where one ought to be’.Footnote 63 Being forced to reflect, somewhat ironically though not necessarily insincerely, in an extratextual or intertextual way on the horizon of vocal or bodily excess is a music-theatrical hermeneutic parallel to the kinds of strategies associated with the paracinematic ‘aesthetic’. Davies’s strange medievalized chronology too – the presence of early-music quotation, transformed and lampooned – reinforces this as another layer, both drawing the listener out of the action and immersing them in its fluid temporalities.

And while the score is absent of voice (although the shouted dialogue in the film itself more than makes up for that), Davies’s music for The Devils, in its necessary negotiation with Russell’s own ear-splitting cinema-auteur vision, proposes something of a companion work to Connery’s version of Taverner too, coating its own salvation negatively – Connery uses the phrase ‘excluded sacred’ – at the expense of good taste and in medieval costume. Consider the arch-conservative activist Mary Whitehouse’s own withering critique of The Devils (a film she probably never saw), pompously delivered in a manner suggestive of a kind of religious authoritarian hysteria (of the sort both the opera and the film set out to satirize):

That the film critics – some of whom have played a not inconspicuous part over the years in the acceptance of decadence within the cinema – were, this time, unanimous in their critical attack on The Devils is a true measure of the corruption of art, the extent of the blasphemy, the violence and perversion, the cacophony of sound which characterized this film.Footnote 64

Notwithstanding her inability to read in a work anything more than a face-value or two-dimensional morality, Whitehouse – ever, nevertheless, a sensitive critic – goes one step further than the average moralizing reviewer, recognizing the corrupting and affective potential of sound and music here and making the direct link between ‘cacophony’ and ‘blasphemy’. Ahead of her time, she foreshadows – negatively, of course – the development of so-called drastic as well as sonic turns in musical scholarship. One cannot help but wonder what, if ever she saw or heard them, she might have thought of such works as Vesalii icones, Revelation and Fall and Resurrection, and of the cacophonic violence that they depict – narratively, dramatically or sonically. Would The Devils have escaped the fate that she had partially engineered for it had it been reimagined in a form fitting the concert hall or opera house instead? Or might Davies have found himself on the wrong end of one of her campaigns?

Whatever might have been the case, thinking this through does occasion a number of questions with which I wish (rhetorically, at least) to colour the investigation here. What happens qualitatively to this type of music in its transition from the opera house to the screen, where one critic’s (Kerman’s) ‘marvellous score’ (despite being a ‘less marvellous […] theatre piece’) becomes corrupting, blasphemous and in some way immoral, depending on the media in which it is delivered?Footnote 65 And how is this excess – between music and image, blasphemy and violence – understood as it moves between these two ideological spaces? In particular, though, I want to explore the role played by the distant past (or, as I see it, medievalism) in negotiating or destabilizing these distinctions: does historical distance, I ask, strengthen or diminish this spiritual-heretical cacophony and corruption?

What fresh lunacy is this? A crocodile?! Chant and medievalism in The Devils

The Devils begins with a disclaimer, presented in a stark red font against a black background, a declaration of historical authenticity of the kind ordinarily disliked by the fantasist Russell:Footnote 66 ‘This film is based upon historical fact. The principal characters lived and the major events depicted in the film actually took place.’ This warning, that the film that follows is ‘authentic’, is followed immediately by the concurrence of the image of a stage and the unmistakable sound of 1970s-era early music. On this stage, France’s King Louis XIII (Graham Armitage) on a giant shell emerges from shifting cardboard waves, recreating Botticelli’s Birth of Venus and dressed in a costume consisting of three golden shells covering only his genitals and nipples. He is heralded into view here by the characteristically ‘shawmy’ sound of the Early Music Consort of London and their version of the courante from Praetorius’s Terpsichore. Footnote 67 After he is crowned by two well-toned dancers, that piece segues into the livelier ‘La Bourée’ from the same Praetorius collection, and the choreography livens up in kind.Footnote 68

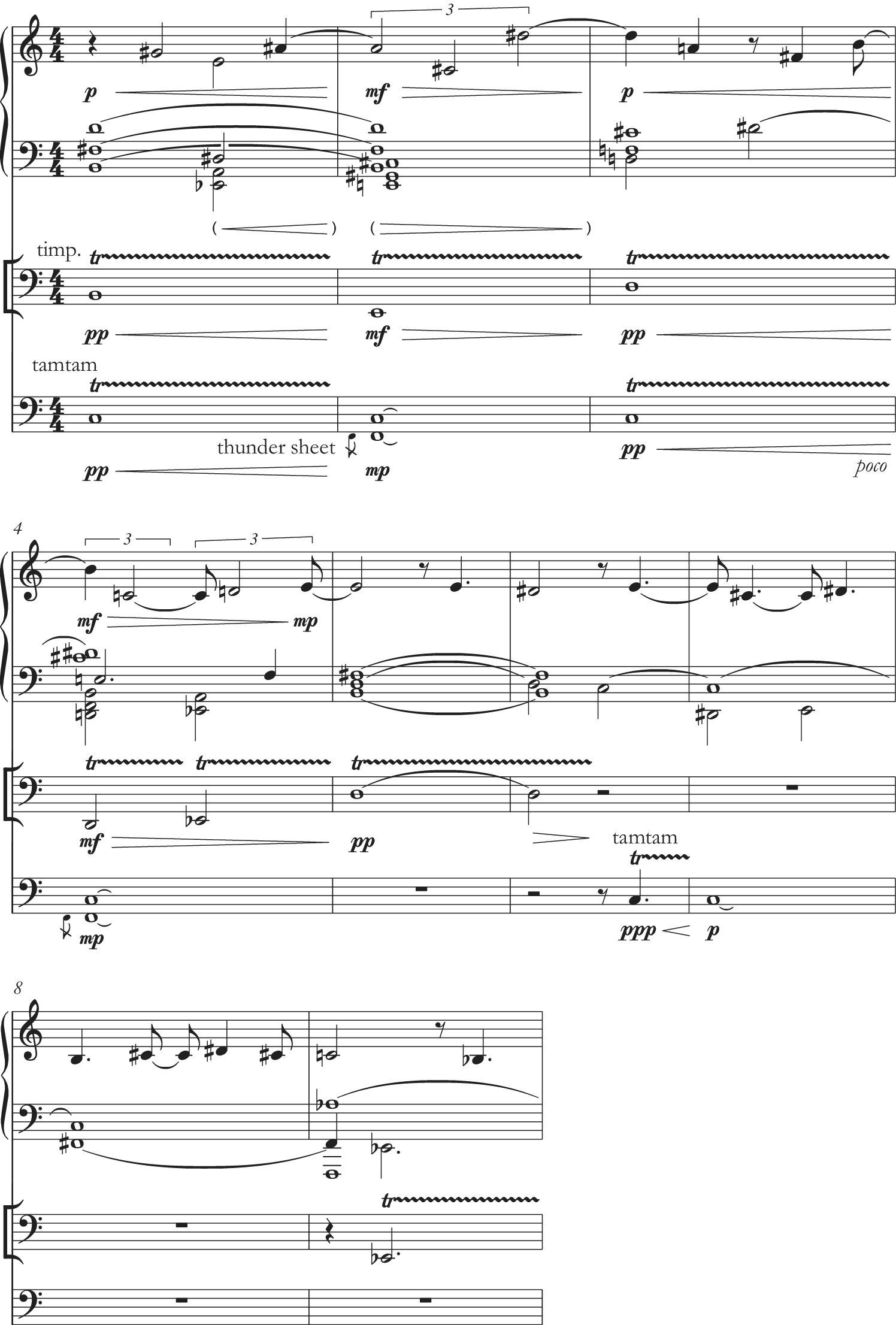

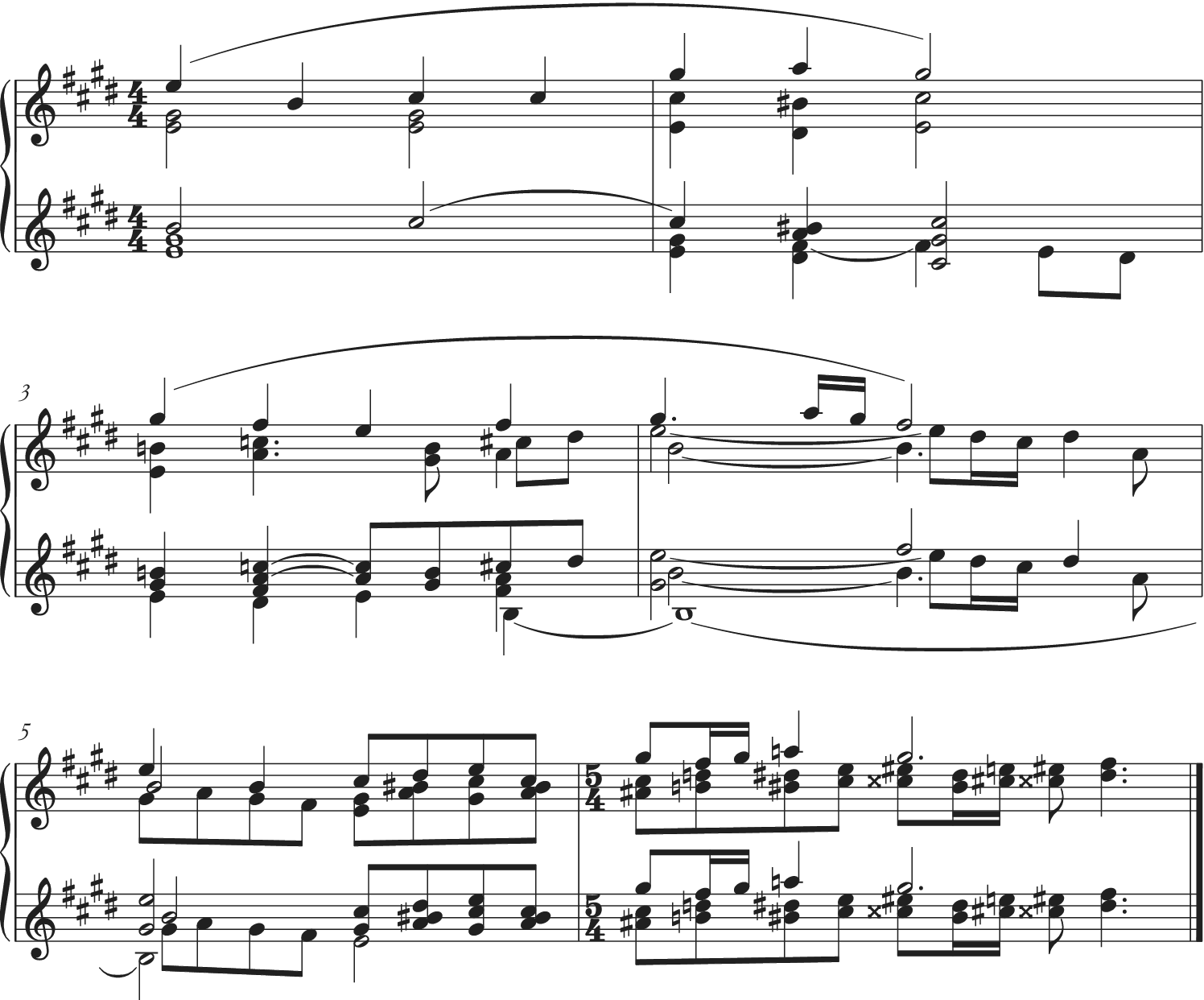

The room is full of chattering and gossiping courtiers, mostly dressed as women, and the highly camp display on stage and off stage is juxtaposed against the impotent masculinity of a chair-bound, visibly uncomfortable Cardinal Richelieu (Christopher Logue) in the middle of it all, flanked by two austere nuns shyly averting their gaze. The presumably diegetic music stops only for the King to receive applause, and as Richelieu addresses him, declaring his desire to help birth a new France ‘where church and state are one’, we first hear Davies’s score (see Example 1), which is unleashed simultaneously with the King’s response: ‘Amen’. The music, which is loud in the mix, briefly recedes as Richelieu adds: ‘And may the Protestant be driven from the land.’ This is followed (at bar 4) by an ear-splitting scrape performed on the thunder sheet in the soundtrack that coincides with a jump cut, from a closeup on Richelieu’s face to the face of a rotting corpse (with maggots in its eyes and mouth) suspended on a wheel alongside the road leading to Loudun.Footnote 69 The opening scene, in its interminably over-the-top way, cogently sets the tone for the film’s consistent and routine use of the shocking juxtaposition of exuberant early-music timbral ‘authenticity’ (however illusory) and a harsh sort of sonic expressionism. The noisy heresy to which it succumbs likewise underlines the concurrence of temporalities and even the (macabre) humour of it all.

Example 1 First nine bars of the title sequence of The Devils, music by Peter Maxwell Davies (transcribed from London, British Library, Add. MS 71263, fol. 51r). Reproduced by kind permission of the Peter Maxwell Davies Estate.

The melody, in the upper voice of Davies’s title introduction, is taken by the alto flute: an uncanny metallic timbre probably relatively unfamiliar to mainstream audiences. Its austere and lyrical line sketches out something bordering on the dodecaphonic (it plays a set of ten pitches without repetition) before coming to rest on a fragmentary quotation from the plainchant ‘Dies irae’ (the descending E–D♯–E–C♯–D♯–B–C♯). The accompaniment throughout Example 1 seems to suggest a kind of B minor tonality. However, false relations (such as the recurring E♭ and D♯ simultaneities) encourage a subtly discombobulating microtonal undercurrent. The broadly chordal accompaniment, delivered polyphonically with dovetailing resolutions, has a contrapuntal logic both entirely typical of Davies and evocative of a medieval kind of horizontal musical thinking. The embedded ‘Dies irae’ chant here has special status throughout the score, as I discuss further below, but it has also been a recurrent part of Davies’s compositional toolbox since as early as 1958.Footnote 70 Davies is, knowingly or not, tapping into long-standing traditions here, the ‘Dies irae’ having completed something of a semiotic transformation by this point, running (as James Deaville sees it) the associative gamut from the principally holy to the wholly satanic.Footnote 71

Within Loudun’s not-so-medieval walls, in the next scene, the film’s main protagonist Grandier preaches to a packed square of townsfolk, leading the funeral for a recently deceased governor of Loudun. A procession follows (see Figure 2) in which an ensemble of period instruments is heard to play the aforementioned ‘Dies irae’ chant in unison (accompanied by its sung Latin text), now in its historically appropriate context. The ‘Dies irae’ heard earlier in expressionistic dress is now retrospectively reimagined as a pre-echo of the diegetic period-appropriate music to come. The presence of historical instruments on screen – the serpent and sackbut, for example – has a powerful othering effect, one that is exploited in much cinematic medievalism.Footnote 72 That othering effect of alien instruments is often exploited (in both film and early-music practice) to conjure quasi-orientalist associations, but here they carry, I suggest, inauspicious and unnerving significations.Footnote 73 In this way, medieval music more generally works, with the expressionistic parts of the score too, to evoke an alienating distance both temporal and geographical.

Figure 2 Historical instruments in Loudun funeral procession in The Devils.

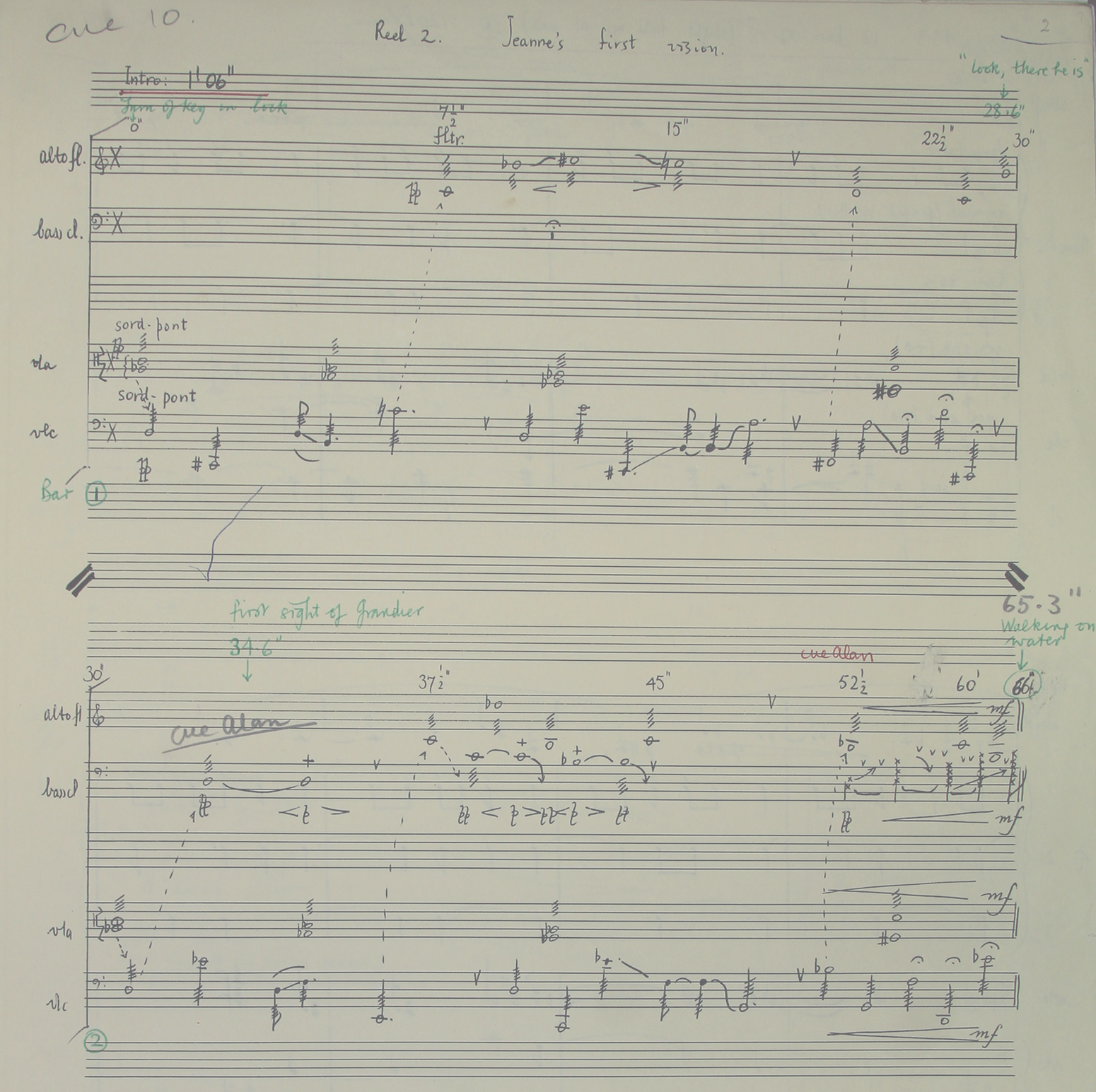

Medieval compositional techniques haunt Davies’s manuscripts here, and devices such as ‘isorhythm’ and ‘mensural canon’ are regularly referred to in labels by the composer (even when their presence is not entirely apparent to the listener). Indeed, the ‘Dies irae’ repeats for several minutes in this scene with a sort of trance-inducing and rhythmically rigid insistence (becoming defamiliarized); it is then (after an edit) heard from outside while the Ursuline sisters gossip in the corridors of their cloistered convent. When two women in the street outside are overheard by the abbess Sister Jeanne discussing Grandier’s sexual exploits, the passage designated by Davies (in his handwritten score) ‘Jeanne’s first vision’ begins, and for the duration of this 1' 06" ‘intro’ (see Figure 3) the sound of a muted cello played sul ponticello and tremolando (as well as flutter-tongued flute and bass clarinet harmonics) weaves in and out of the procession, which is still repeating the ‘Dies irae’ in the background.

Figure 3 The opening of ‘Jeanne’s first vision’. London, British Library, Add. MS 71264, fol. 2r. Reproduced by kind permission of the Peter Maxwell Davies Estate.

The chant’s excessive presence cannot be contained either by the walls or by the women’s conversation, and it is Grandier’s own presence (which is what is really being announced here) that is the inciting incident for Sister Jeanne’s subsequent obsession and the events of the film that follow. The passage is notably rendered in what Davies called in his own tabular analysis ‘free notation’, and the musical textures are harsh and metallic. There are further transformations of the same chant source material here too (the first four notes in the cello part, with a C♯ displaced by an octave, for example), with each voice clearly conceived as a polyphonic transformation of it.

A dream sequence that lends itself well to a multipart composition follows, as Sister Jeanne – obsessed with the charismatic Grandier – has a vision of the priest as Christ walking towards her on water. In this scene she falls before his feet to a relatively slow and regular percussive processional accompaniment (cymbals, large tabor, tamtam and so on). At this point, the alto flute plays a melody derived, again, from an inverted ‘Dies irae’ beginning (B–C–B–D–E). But as Jeanne washes his feet there is another noisy escalation dominated by whistles and flexatone improvisations, as well as flutter-tongued winds, while Jeanne remembers that she has a severe scoliosis and her hump returns. She begins screaming, ‘I’m beautiful!’ and ‘Don’t look at me!’ as an assembled circle of nuns laugh hysterically at her. The combined cacophony is a musical blasphemy seeming to exceed and destroy her once serene, holy (and, indeed, erotic) vision. By this point we are barely 13 minutes into the film, but the sonic onslaught – its curious combination of parallel and dovetailed temporalities, tonalities and escalating intensities – has bludgeoned any such simple, linear and cinematic, temporal logic. A short scene that follows, without music, in which the post-coital Grandier abandons a lover moments after she reveals that she is pregnant with his child, is somehow deafening by comparison.Footnote 74

In Rob Young’s Electric Eden, a panoramic history of twentieth-century British folk and medieval music-making (in spheres both ‘high’ and ‘low’), The Devils and its score are featured for their significant place in that story. Highlighted here are its links, culturally speaking, to the contemporaneous folk-music revival and a fashion for BBC medieval costume drama.Footnote 75 However, Davies is strangely absent from this discussion, and it is Munrow’s contributions that are foregrounded.Footnote 76 The reader is left, perhaps, with the assumption that the noisy modern score has little to contribute to the subject of the study – in comparison, at least, to the timely early-music interpretations of Munrow and the Early Music Consort of London. It may seem that this is the work of a socially detached composer of the avant-garde unlikely to be part of a uniquely British post-war cultural dialogue with a medieval past. Elsewhere, John Callow has, in a cultural history of witchcraft, drawn attention to the combination of Munrow and Davies in this film, the latter characterized as being at the ‘cutting edge of the avant garde’, with the resultant soundtrack offering ‘another example’ in the film of the mix between ‘knowing anachronism and scrupulous attention to historical detail’.Footnote 77 In another rare example of critical recognition for The Devils in a musical textbook, the question of ‘anachronism’ is posited as posing ‘many problems’.Footnote 78 The authors’ response to this problem lies, however, in the unambiguous contemporaneity of Davies’s contribution: a music that is alien to the film’s world but that imbues the film-text with modernity’s own gaze.

These very perspectives – coming from scholarship on folk music, witchcraft and film music – are, I suggest, making the same error as does the explicitly modernist and musicological discussion, which is likely to see in the musical collaboration at the heart of The Devils a kind of happy musical accident, or at least a sort of unremarkable filmic parallel for an isolated modernist music practice. Here, questions of anachronism and authenticity are inevitable, and this juxtaposition of new and old is a problem to be solved. These positions take for granted, in different ways, the same well-trodden narratives of modern, dissonant or ‘challenging’ music, and its teleological temporality is left as being necessarily a break with the past and in some way always entirely ‘contemporaneous’.Footnote 79

Were we to recognize, instead, a form of medievalism (playfully atemporal, and engaged meaningfully with what it means to be medieval in the – ever-shifting – present day), the score’s position in the film might be said to play an altogether more nuanced and interesting role. Indeed, it is my conjecture that the two temporalities coincide and inflect one another. As the past is made present and the present is made (sonically) past, the score (with its own complexly noisy and granular materiality) becomes physical and ‘authentically’ present in history too. Where medievalism can demodernize, modernity might reinscribe the artifice of the medieval. In watching The Devils it is hard, then, to sustain some of those typical simplistic binaries associated with film and music criticism: the authentically old and the modernist new, mapped here, perhaps, onto the diegetic and the non-diegetic. It is not, perhaps, so simple that Munrow’s ‘period-appropriate’ music sounds on the inside, while Davies’s voice provides a present-day ‘commentary’ (on the outside).

Taking place immediately after the aforementioned deafening silence, a scene depicting a gruesome plague outbreak on the streets of Loudun employs an expressionistic score underpinned by temporally incongruous and ‘authentically’ medieval techniques of composition. In it, among other things, Oliver Reed’s Grandier spars with the father (Louis Trincant) of the pregnant (and now spurned) lover, gleefully defending himself from his sword-wielding opponent with a crocodile. In this absurdist display, the sword eventually shatters against the rigid, though seemingly feather-light, theatre-prop reptile. Grandier had previously thrown it out of the window while interrupting a cruel and arcane attempt by a pair of alchemists to cure a dying woman (‘What fresh lunacy is this? A crocodile?!’ Grandier shouts at them.) It is an oddly comic and jarring moment, even by the standards of an avowedly odd and jarring film, juxtaposed as it is against piles of bodies being collected for incineration.Footnote 80

Comic forms of medievalism are recurrent, if contradictory, phenomena in the popular imagination according to D’Arcens, disrupting progressivized and periodized models of historical continuity, directing ridicule both at a medieval ‘other’ and at the present.Footnote 81 The crocodile is, presumably, the same one mentioned in the script quoted at the beginning of this article, a scene in which it did not survive the cut. In a nod to traditions of comic medievalism, then, it is, we might say, both present and absent; comically unwelcome, but also in some sense authentic in that its incongruity is meant to imbue the scene with a kind of absurd historicism. (It is there, after all, to be used as medieval-style plague cure.Footnote 82 )

Isorhythm is a technique for the ordering of musical time, and in the novel context of Davies’s medievally inflected attempt to work within the modern cinematic medium, that is its function in the plague scene.Footnote 83 Taking place between approximately 16' 00" and 22' 50" in the original British X-certificate version of the film, isorhythm and plainchant has, you might say, a role to play similar to that of the reptile in the seven-minute scene. Indeed, these seven minutes are accompanied by a four-section isorhythmic composition (with a coda and brief introduction) in which the ‘Dies irae’ chant is both heard and disguised, used and transformed as the basis for both angular polyphony and sombre lyricism, and as a sort of underlying structuring device.

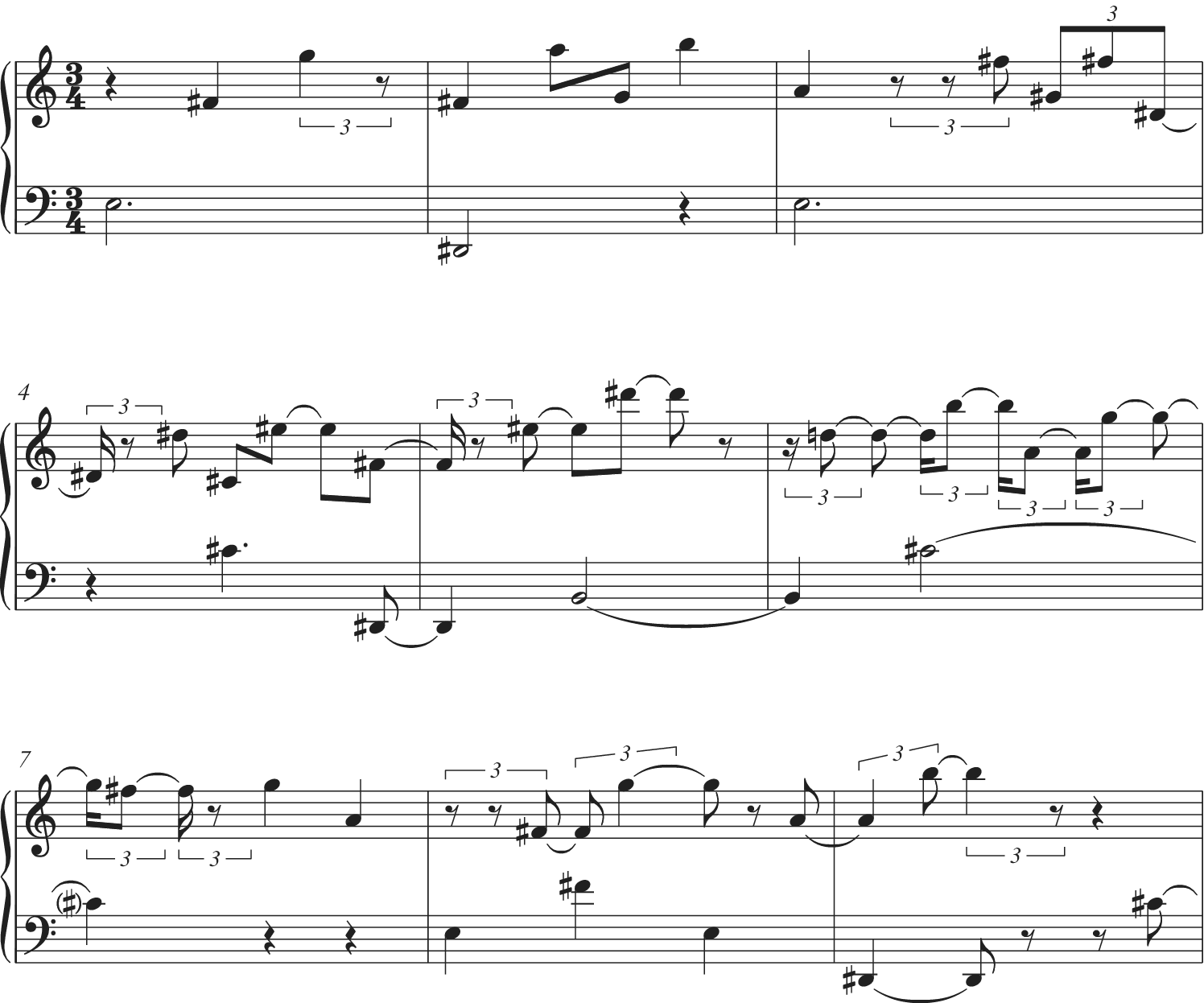

The music of this scene begins with a script cue: Grandier’s final line as he leaves his naked and pregnant lover Philippe Trincant in tears: ‘Hold my hand. It’s like touching the dead, isn’t it?’ It sounds, you could argue, trashy, and although tightly controlled, it feels unrefined, as if always threatening to fall apart, perhaps as if it were loosely improvised. A sustained chord heard at several key points in the film (simultaneous, and sort of leitmotivic, major-third dyads on D and E heard over a low rumbling D)Footnote 84 accompanies an edit as Grandier dons his cape and begins a quick march through the plague-strewn streets of Loudun. Then, a short and improvisatory flute flourish (labelled ‘death dance’ in Davies’s notes) made up of an accelerating ‘Dies irae’ chant (or, indeed, row) is sounded simultaneously with the beginning of the isorhythmic section labelled by Davies A1 in his manuscript, of which the opening nine bars are shown in Example 2.

Example 2 Beginning of plague-scene isorhythmic composition (transcribed from London, British Library, Add. MS 71263, fol. 2r). Reproduced by kind permission of the Peter Maxwell Davies Estate.

The passage, with trumpet in the upper voice and trombone plus cello in the lower one (in addition to improvisatory and noisy percussive accompaniment of which I can find no notated trace) is strikingly reminiscent of several of Davies’s much earlier (and ultra-modernist) experiments with chant and isorhythm. It shares much in particular with his interpretation of the technique of mensuration canon in such works as Prolation and St Michael (both 1958).Footnote 85 Stripped bare like this, the music rendered as just two contrapuntal voices in Davies’s only existent notes for the score, his modernist-medievalized treatment of the ‘Dies irae’ should be abundantly clear: a manipulated version of the chant unfolds in both voices, albeit masked by octave displacement. In the lower voice, and save for a few alterations, the chant is literal (note the first four notes: E, D♯, E, C♯), while in the higher voice it is, mostly at least, inverted and transposed up a tone, beginning on F♯. The two voices proceed according to the logic of an adapted mensuration canon, and the upper voice copies the rhythmic schema of the lower one at approximately three times its speed (a crotchet becoming a triplet quaver, and so on). As with much of the score, the effect is anything but subtle, and while the listener may not hear the chant outright, the ‘Dies irae’ recurs so loudly and so frequently that the assault is, over time, undeniable. Davies wields his medieval weaponry like Grandier does his crocodile.

Successive subsections of the scene are ordered according to repetitions of a ‘Dies irae’ cantus firmus, whose rhythmic scheme (or ‘talea’) is shown in Example 3. Part A1 proceeds until Grandier arrives in the room of the dying woman and confronts the alchemists, starting what Davies labels part B1 (‘isorhythmic to A1’), with the same rhythmic scheme and ‘Dies irae’ cantus firmus, albeit inverted. The slower, sparser, part B2 (here the counterpoint is carried by strings) begins as the woman dies; and part A2 as Grandier returns to the street (where the musical racket resumes). Table 2 summarizes the isorhythmic design of these parts. A final section labelled ‘coda’ accompanies a short sequence in which Grandier is seen later anointing a giant pit of corpses with an assistant clergyman (the latter disapproving of Grandier’s sexual exploits). The recurrent D/E major-third dyads (or ‘death chords’) are heard under their dialogue. As the camera lingers on the pit of plague victims, a cart empties another delivery of bodies into it. A flute and trumpet can be heard then repeating an indeterminate, swung and stilted, manipulation of the ‘Dies irae’ chant once again. The music fades, and the scene cuts abruptly to outside the convent.

Example 3 Rhythmic pattern for cantus firmus in the plague scene, talea 1 (transcribed from London, British Library, Add. MS 71263, fols. 2r, 3v). Reproduced by kind permission of the Peter Maxwell Davies Estate.

Example 4 Rhythmic pattern for cantus firmus in the plague scene B2, talea 2 (transcribed from London, British Library, Add. MS 71263, fols. 7r, 8v, 9r). Reproduced by kind permission of the Peter Maxwell Davies Estate.

TABLE 2 BREAKDOWN OF ISORHYTHMIC PARTS IN PLAGUE SCENE ACCOMPANIMENT

| Part (and description in score) | Low stave | High stave | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intro (to reel 3), cue ‘like touching the dead, isn’t it?’ | 10 secs. of sustained chord (D and E dyad over a low D) connecting end of previous scene to this one, plus accelerating ‘death dance’ (‘Dies irae’) | ||

| A1 (cut to Grandier in plague street) | talea 1 (see Example 3), ‘Dies irae’ cantus firmus, starting on E | mensuration canon, partly inversion of ‘Dies irae’, starting on F♯ | |

| B1 (from G. enters Mme De Brou’s room to Mme De B. dies) | talea 1, ‘Dies irae’ cantus firmus inverted, starting on E | freely composed | mostly cut from actual film |

| B2 (from Mme De B. dies to Trincant in street) | talea 2, metre 4/4 but each bar subdivided into 5 equal beats (see Example 4) | two voices playing simultaneous octave-displaced ‘Dies irae’ chants, starting on E (normal and inverted); additional flute part oscillating slowly between E♭ and B♭ | slow and sombre; accompanies death of Mme De Brou |

| A2 (from Trincant in street to death pit) | talea 1, ‘Dies irae’ cantus firmus inverted, starting on E (repeated from B1) | material partially derived from A1 (resembles mensuration canon) | |

| Coda (from cut to death pit to end of reel) | sustained D/E chord; improvisatory melodies derived from ‘Dies irae’ |

‘The full Hollywood treatment’: Footnote 86 authenticity and excess in modernist medievalism

A barely audible historic ‘authenticity’ bristles in The Devils under a surface of crass excess, one that is as comic as it is disturbing. Indeed, the complex isorhythmic design of parts of the score described above, whether or not it is aurally perceived, lends those moments some architectonic sonic gravitas, even if the wild percussive accompaniments distract and distort.Footnote 87 But were we to see here the appropriation of the ‘Dies irae’ as yet more avant-gardist esoterica, it would be worth considering the extensive currency the chant carries in the cultural-imaginative terrain that encompasses orchestral romanticism and popular culture.Footnote 88 One of music’s most enduring intertexts, the ‘Dies irae’ is the site for an unlikely convergence of all that is popular and serious in mainstream musical culture. As early as 1953, Robin Gregory wrote of the sacrilegious appropriation of a ‘most solemn’ church rite ‘intended to call to mind awe inspiring events, [having] no association with anything evil’. But, he explains:

Parodies of Berlioz, Liszt […] regarded by many as in bad taste and even approaching profanity, intentionally give the melody a baleful significance. Repeated use in this manner has extended to debase its real character so that now it is almost taken for granted that its use is cynical in intention.Footnote 89

Davies, of course, had his own penchant for sacrilege and parody, and it is clear even then that by appropriating this chant to inauspicious ends he was doing something that was practised widely, with clear significations for music lovers and cinema audiences alike. Indeed, Davies taps into a language of popular medievalism and contributes to a broader cultural dialogue that negotiates meaning at the horizon of scholarly rediscovery and interpretation (of medieval objets trouvés) and mass popular imaginaries. Simultaneously, it should be said, he is revisiting his own idiosyncratic canon of compositional practice.

There is another chant, one with less intertextual currency, that acts as a musical protagonist in The Devils, and is subjected more overtly to abasement at the altar of cinematic excess. The ‘Ave Maria’ appears a number of times in the film, including once as a foxtrot. On two occasions it is employed in Davies’s score for moments of absurd bathos. First, a wallowing Sister Jeanne believes that Grandier has arrived at the convent following an invitation to take up a post there, and as she runs through the corridors, the ‘Ave Maria’ melody is played on ascending ornamented and heavily vibrato strings, only to be interrupted abruptly at the sight of Grandier’s assistant, Father Mignon. Any comedy here is immediately turned on its head: moments later, Jeanne is subject to cruel torture (or exorcism).

Later in the film, in the middle of several scenes of possession and debauchery, the ‘Ave Maria’ returns again. Davies’s music here responds to the following composition brief, probably indicating its composition at a later stage in the film’s post-production:

MAX

Ken would like an extra piece of music in REEL 10:

After Jeanne says ‘I am free’ down to the laughter when the king shakes the empty box (27 seconds).

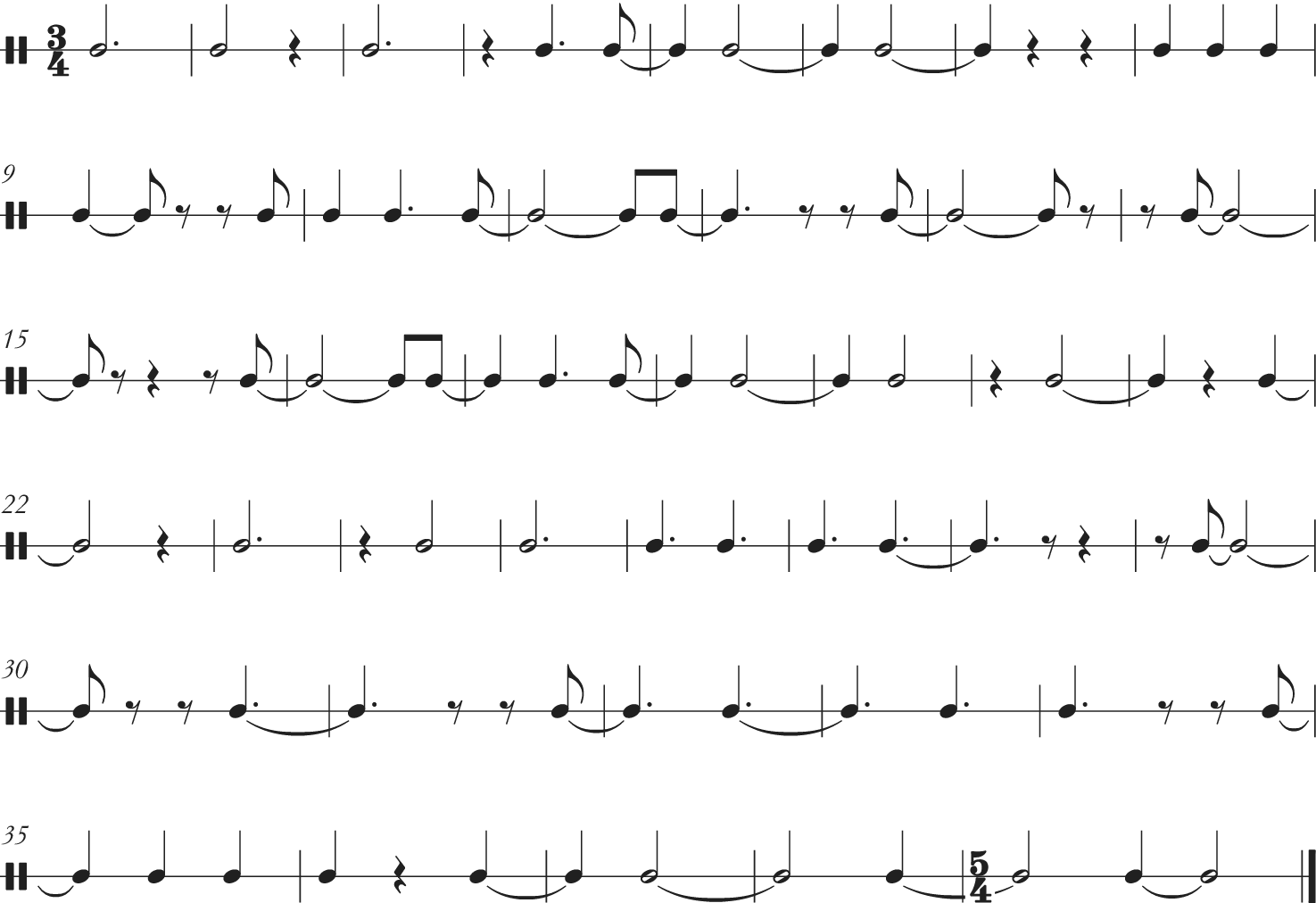

The type of thing Ken suggests is the full Hollywood treatment: a syrupy hymn sung by a celestial choir with harps etc.Footnote 90

Here, scenes of religious frenzy are interrupted by the arrival of King Louis XIII himself (disguised as Duke Henri de Condé): a discordant parody of a fanfare plays. The King here withdraws a golden relic box that he claims contains Christ’s own blood, which the witch hunter Father Barre promises will dispel the demons possessing the nuns. As he opens it, Sister Jeanne professes her freedom and the room erupts in ecstasy, followed by peaceful silence; the music in Example 5, involving the organ, the choir and more, then plays. However, the rising diminished triads that mark out the second half of this passage, which deforms the ‘Ave Maria’ with its deluge of Hollywood syrup, indicate a sudden and again absurdist inversion: the box is empty. ‘What sort of a trick are you playing on us?’ the King jokes before leaving to another fanfare. Hysterical laughter descends into chaos; this is where, in its uncut form, the ‘Rape of Christ’ would begin.

Example 5 ‘I am free’ reduction (transcribed from London, British Library, Add. MS 71264, fol. 17r–v). Reproduced by kind permission of the Peter Maxwell Davies Estate.

Those absurdist rising diminished triads mark out the absence at the heart of a holy relic (and thus make a mockery of religious pretence and power) paradoxically with a kind of musical excess: a significatory, stylistic excess, emptying the musical container (‘Ave Maria’) of its authenticity and signalling the artifice of its imaginative displays. I have referred to the idea of ‘excess’ such as this throughout the present article to describe, perhaps in a rather too capacious (though not an unfitting) way a range of phenomena. But excess as a concept serves the function of drawing a line across and connecting some of the disparate themes in this article. Excess, for example, characterizes medievalism, being in a sense the present-day overflow of a period long sealed off (historiographically speaking) yet accruing in the process a kind of limitless imaginative currency.Footnote 91 Excess and excessiveness are practically synonymous with Russell’s film-making style in the popular reception of his work,Footnote 92 forming the basis of his present-day reappraisal as a modern ‘mannerist’.Footnote 93 Opera too, in so far as The Devils mirrors Taverner, negotiates its own politics of excess.Footnote 94 Excess in particular has a complex, but no doubt important, place in conceptions of artistic modernism, as in recurrent narratives of ‘rupture’ that define it.Footnote 95

The film theorist Kristin Thompson sees excess as a crucial part of film more generally, and her thinking on the subject forms the justification for the paracinematic reading strategy mentioned above, ‘homogeneity’ – excess’s Other – being only a perceived emergent property of a work consisting of often disparate constituent parts. Inconsistencies in plot and pacing, moments of perceptual shock and more can come, she writes, to disrupt a sense of wholeness in a film; in recognizing the complexity of a work teetering on dissolution along the fault lines of excess we are intrigued ‘by its strangeness’ and made aware of how ‘the whole film – not just its narrative – works on our perception’.Footnote 96 The question of ‘authenticity’ looms large here: not in any essentialist sense of the term (whether something is or is not ‘authentic’ is a rabbit warren), but rather as something disunifying – as an aesthetic, a colour or a mood that connects the practices of the film’s contributors just as it threatens to collapse the whole excessive, paracinematic edifice. The Devils, much like some of Davies’s most assiduously ‘authentic’ works (all the ‘Taverner’ pieces, the Missa super L’homme armé and more), is excessively authentic.

Indeed, it is notable that Russell and his crew took every opportunity to boast of the research they did to make the film historically accurate at the time of its making and release – a striking move given its unashamedly anachronistic experience.Footnote 97 Warner Brothers even decorated their marketing for The Devils in the USA with a disclaimer that pre-empted (and in the process perhaps contributed to) the kind of censorious uproar that would make it unsellable there:Footnote 98

It is a true story, carefully documented, historically accurate – a serious work by a distinguished film maker. As such it is likely to be hailed as a masterpiece by many. But because it is explicit and highly graphic in depicting the bizarre events that occurred in France in 1634, others will find it visually shocking and deeply disturbing.

We feel a responsibility to alert you to this. It is our hope that only the audience that will appreciate THE DEVILS will come to see it.

In other publicity, as in the American audience trailer, this same thing is often simply shortened to ‘“THE DEVILS” is not a film for everyone …’. In the first instance, the passage’s defensive tone indicates some desire to be recognized according to the normative standard of a ‘distinguished film maker’ – an oddly self-defeating gesture which stakes its claim for a highbrow status that Russell himself would consistently undermine in his long and rocky career. Perhaps this is merely a savvy (if ultimately failed) attempt at promotion through controversy;Footnote 99 whatever its intended purpose, it is interesting that historical ‘authenticity’ is leveraged here into a politics of censorship.Footnote 100 Is historical veracity, I wonder, expected here to mitigate the film’s immoral, or ‘pornographic’, excesses; or does it, in fact, facilitate them? This film might disturb you, but at least it does so ‘authentically’.

Authenticity’s contradictory, disunifying and excessive impulse is embodied, then, by the early music that plays so strong a role in this film and in Davies’s work of the time. And this might account for the prevalence in works discussed here of Britain’s then most significant and popular exponents of the relatively young ‘early music’ movement: Munrow and the Early Music Consort of London. Early music, it is worth remembering, has in the past operated in a sphere neither strictly ‘high’ nor ‘low’, and has been described (for example by Nick Wilson) as then being a ‘new social movement [… providing] a voice for the identity-less [… which could counter] the alienation of the market’.Footnote 101 Its influence became widespread, not least in the medieval-minded folk revival that took place roughly at the same time, in the progressive rock movement that would come, and in myriad costume dramas which littered the popular imaginary landscape of the time; not to mention in Davies’s avant-garde generation. Young has noted the very real and ‘growing interest in medieval-period reconstruction’ in the ‘music, cinema listings and television schedules of the late 1960s and early 70s’, which he sees as a staple of a post-war British culture finding its identity in the ‘grain of the past’.Footnote 102

The modern history of early music has its own politics of ‘authenticity’ which becomes by extension one of excess, too, as in the eventual attempts, connected to the English ‘a capella heresy’ debate in the 1980s, to purge the movement in Britain of ‘Catholic Continental excess’. This much was intended, according Helen Dell, to ‘keep the borders clearly marked between the folk and medieval music-making of England and that of the continent’.Footnote 103 An excess of history, of interpretation, was seen in some quarters and in some of the more stylized interpretations of the repertoire as being problematic or even threatening. Such a politics makes distinctions between the authentic and the ‘inauthentic’ meaningless – or such was the opinion of Richard Taruskin, whose criticism of the ‘authentistic’ mode of interpretation saw it as an essentially modernist endeavour. His account of the ‘falseness’ of the notion of an ‘authentistic performer [stripping away] the accumulated dust and grime of centuries to lay bare an original object in all its pristine splendour’ is suggestive of material surpluses and excesses too.Footnote 104

Russell and Davies are staging something of a dramatization of the politics of early-music excess in The Devils. In this way, Russell’s cinematic vision affords us in turn a more nuanced second look at Davies’s own ‘ironical’ treatment of the musical materials of the period. Indeed, connected with and dovetailed into Davies’s score, the early–modern sonic continuum becomes something of a snake eating its own tail in The Devils. All the same, the discontinuities of musical time create opportunities, in conjunction with Russell’s paracinematic style, for the viewer (or listener) to locate new types of transgressive meaning.

Getting to understand what is meant by modernist medievalism – by the persistent fascination held by identifiably ‘modernist’ composers like Davies for early music, and for ‘medievalness’ more generally – is not an easy task.Footnote 105 This is partly because serious-minded composers of new music (of older generations, especially) tend by habit, if not by training, to distract, to focus their discussion on the more technical, recondite aspects of their craft and to form a picture of what influence the ‘past’ might have on their work through that lens. Indeed, it is something of a theme of Davies’s own writings on the subject that, for all the colour, excess, fun and absurdity of his musical medieval personality, when prompted to discuss the subject the tone becomes wholly dry.Footnote 106 In turn, such perspectives have coloured our latter-day reception of the legacies of musical modernism.

In this way, The Devils is suggestive of a kind of crack in the carefully crafted modernist edifice: one that articulates the transgressive and communicative power of Davies’s medievalism (and, by association, that of British music since the war) in the context of a broader current in challenging and popular medievalist artwork more generally. In an unusually candid account of Davies from a 1979 issue of Gay News, the journalist Alison Hennegan’s description of his London flat is similar to Russell’s scene-setting description at the beginning of this article: ‘filled with objects from those [medieval and early Renaissance] centuries, many of them glowing with unostentatious beauty, […] rejoiced in by being used rather than “preserved”’.Footnote 107 In a short yet broad discussion that deals with a range of subjects, including the challenges experienced by homosexuals in contemporary music, protest and politics, and in particular Davies’s alleged ‘turning his back on the modern world’ (in reference to his retreat to Orkney), Hennegan goes on to describe her spiking his enthusiasm following a comment on the unusual anachronisms of his own cluttered medieval room:

I know, I know! Everything we’re touching now and looking at in this flat is old, part of the past. And then you turn round and you’re looking at the future. And we’re just a juncture between the past and the future. And just to say ‘this is it’ and blinker yourself, whether backwards or forwards, is absolute nonsense. There’s no way of understanding one’s particular point in time if you do that.Footnote 108

This might seem out of keeping, but Davies’s outburst is revealing: his account of the present as poised precariously but excitedly between past and future proposes a popular sort of counterpoint to typical teleologies of musical modernism which see the past primarily as a wellspring of incidental materials with which to access the future. Indeed, his talk of ‘understanding’ our ‘particular point in time’ goes somewhat beyond the typical injunction to learn from the past and suggests a more vitalistic reading of history’s presence as being essential to now, and to the future, and in that sense essential to modernism writ large.

It is often said that a good (or successful) film score is one that goes barely noticed. Given the relative dearth of recognition of Davies’s score for The Devils (an absence more than filled by that very score’s noisy, ugly excess), one might see here alone reason to celebrate. But the challenge that the film’s score proffers to our conception of popular film, musical modernism and British musical modernism specifically, as well as of widespread and multimedia imaginative medievalisms (and the intersection of all these and more), suggests to me a missed opportunity. Davies’s trashy, excessive score, in conjunction with Russell’s own cacophonous cinematic vision, speaks powerfully to our understanding of both history and the distant past, and in turn to that of our modern world as well.