In 1946, the entertainer and activist Paul Robeson pondered America's intentions in Iran. In what was to become one of the first major crises of the Cold War, Iran was fighting a Soviet aggressor that did not want to leave. Robeson posed the question, “Is our State Department concerned with protecting the rights of Iran and the welfare of the Iranian people, or is it concerned with protecting Anglo-American oil in that country and the Middle East in general?” This was a loaded question. The US was pressuring the Soviet Union to withdraw its troops after its occupation of the country during World War II. Robeson wondered why America cared so much about Soviet forces in Iranian territory, when it made no mention of Anglo-American troops “in countries far removed from the United States or Great Britain.”Footnote 1 An editorial writer for a Black journal in St. Louis posed a different variant of the question: Why did the American secretary of state, James F. Byrnes, concern himself with elections in Iran, Arabia or Azerbaijan and yet not “interfere in his home state, South Carolina, which has not had a free election since Reconstruction?”Footnote 2

The struggle for decolonization (este‘mar zeda'i or zedd-e este‘mari) consumed Iranians after World War II as they strove to define the political ethos of their generation. From Palestine and India to Angola and South Africa colonized communities fought tyrannical regimes to bring a measure of equality, freedom, and legal accountability to their lives. Decolonization embraced a wide array of causes: anti-imperialism and political liberation as well as racial and economic justice. It entailed a fundamental ideological reboot, without clear parameters. Decolonization was not only a “constructive revolutionary endeavor,” but a humanitarian necessity. Colonial powers did not themselves disengage “to radically and holistically transform all aspects of life within an ethical global context,” but began to do so because colonized societies pushed them to that reality.Footnote 3 States like Iran without a direct history of colonialism engaged with this debate on two levels: state-to-state interactions and non-elite dissident activism. Nowhere did Iran's complicated and contradictory politics during the late Pahlavi era find better expression than in the debates about decolonization and race.Footnote 4

Civil Rights and Race Relations

In 1961, the Iranian intellectual, Mohammad ʿAli Islami Nodushan (b. 1925) opined about the changing political currents of the day. A literary scholar, a poet, and a trained lawyer, Nodushan had grown up near Yazd and later moved to Tehran to complete his secondary education. He attended the College of Law in Tehran and then traveled to Paris to attend the Sorbonne, where he completed a law degree. Nodushan also spent time in London and gained familiarity with both French and English. Upon his return Nodushan became a professor in Tehran University's College of Literature.Footnote 5 Considered a “dear friend” of Iranian dissident writer Jalal Al-e Ahmad (1923–69), Nodushan observed that at no point since the Suez War was the United States as “exciting” (hayjan angiz) a country. In Nodushan's view, John F. Kennedy's presidency could restore the “prestige” of the United States, a standing damaged by America's foreign policy interventions across the globe. The decline of America's popularity, especially in the decolonizing world, was rooted in the fruits planted by former US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and his support for dictators and so-called friends of the “free world” (donya-ye azad).Footnote 6 Nodushan believed that America now needed to move in lockstep with a changing global community. President Kennedy—a sailor and former naval officer—could not await a Noah-like rescue to survive the rising tides of global decolonization that threatened to engulf the United States.Footnote 7

As Nodushan explained, the Kennedy administration tried to promote a foreign policy rooted in notions of international altruism. In the 1960s this strategy found expression in America's support for Mohammad Reza Pahlavi's social reform program dubbed the “White Revolution.”Footnote 8 The shah, with encouragement from the Kennedy administration, honed in on land reform, women's suffrage, and literacy, among other matters, to bring about a measure of social mobility and relief to disadvantaged populations. But on the issue of race Iran had proceeded at times as if color-blind.Footnote 9 Like the rest of the world, Iran watched as mighty America continued to deprive its Black citizens of basic human and political rights. At the same time, Iranian intellectuals translated the works of Francophone writers who wrote about decolonizing societies, from Martinique to Mauritania. Through this process, Iranians became familiar with the experiences of slavery and systemic racism to which Blacks outside of Iran had been subjected in multiple contexts. Iranians also grappled with the prejudices endemic to their country, but not always in terms of phenotype discrimination. Although Iran had abolished slavery in 1929, public engagement with the subject often remained obscure and inchoate.Footnote 10

As a postwar intellectual, Islami Nodushan belonged to a generation of Third World thinkers who did not rush to embrace America's (or the West's) image of political liberator. In a scathing essay, “Nabard-e Rang dar Ifriqa-e Jonubi” (The Color Battle in South Africa), Nodushan bemoaned the anemic response of the United Nations to the racial injustices taking place there. He dismissed South Africa's claim that its racial problems were an internal affair. Rather, he considered it a ruse to justify the rule of “three million white people . . . over nine million Black people,” because they had access to “power, money and guns.” Nodushan expressed frustration that world leaders had stubbornly insisted on solving “the big problems of humanity” (masa'el-e bozorg-e ensani) with putative “legal frameworks” that had badly flouted the human rights of Black South Africans. He denounced the control of the country's precious mines by a small minority of whites of colonial British and Dutch descent. Apartheid, which he defined as “segregation” (jodayi), perplexed him, as it did other Iranian intellectuals who gravitated toward the struggles of dispossessed non-white populations in an era of decolonization.Footnote 11

Nodushan's essay was written in the midst of heightened political tensions in South Africa that had cemented apartheid as state policy. During the 1960s the governments of Iran and South Africa operated through informal diplomatic channels, which saw the increased isolation of South Africa because of its apartheid practices.Footnote 12 Following the assassination of South Africa's prime minister, Hendrik Verwoerd, on 6 September 1966, the Iranian press provided a dispassionate summary of South Africa's apartheid policies, many enacted during Verwoerd's tenure, which had insisted on “white supremacy” (siyadat-e sefid pustan) over a Black African majority.Footnote 13

As witnesses to their country's fight for independence and political enfranchisement, Iranians showed solidarity with liberation movements that pursued similar objectives. Many Iranians observed the racial upheaval that consumed America with a mixture of consternation and curiosity. On 21 February 1965, the murder of Malcolm X in Harlem dominated headlines. Malcolm's “X,” which reflected a rejection of his slave name, Little, was misidentified as “Tenth” (Malkom-e Dahom) in the venerable Persian daily Ettela‘at (Information; Fig. 1).Footnote 14 The newspaper portrayed Malcolm X as a separatist who believed that American Blacks needed to carve out a distinct state and government for themselves. Black Muslims in America were described as belonging to a unique faction of Islam whose beliefs diverged from those of Muslim orthodoxy. The escalation of racially inspired violence reinforced the intensity of social tensions in America, even as they demonstrated Malcolm's militant attitude (mo‘taqed beh khushunat va sheddat-e ‘amal ast).Footnote 15 That Malcolm X belonged to a group called the “Nation of Islam” further piqued the curiosity of Iranian bystanders. A journal with a religious focus discussed the plight of Black Americans, whose sin consisted simply of being a “Black human” (ensan-e siyah), for which they were beaten.Footnote 16

Figure 1. “Malcolm the Tenth: The Leader of America's Black Muslims Was Killed,” Ettela‘at, no. 11618, 22 February 1965.

Iranians did not quite know what to make of American Islam and its Black adherents. The death of Malcolm X provided an occasion to familiarize the public with the movement that Elijah Muhammad and Malcolm X had spearheaded. Despite the rifts between them, which had cost Malcolm X his life, these racial disturbances gripped Iranian readers. They came to recognize Betty Shabazz, the murdered activist's pregnant wife, who contended that the New York police had failed to provide him with adequate protection.Footnote 17 Similarly, when Martin Luther King received the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize, he appeared in a vignette as another Black American leader whose life was under threat.Footnote 18

The assassination of Dr. King on 4 April 1968 by “a white extremist” (sefid pust-e efrati) made front-page news, as did the ensuing race riots (eghteshashat-e nezhadi). The coverage mentioned King's philosophy of nonviolent “peaceful protest” (mobarezeh-e mosalemat amiz), and the shah also expressed condolences to President Lyndon Johnson and the American people about King's murder.Footnote 19 Another article covered the global reaction to King's killing and noted the resounding support of African countries at the United Nations for his cause.Footnote 20 One piece discussed the significance of the passage of the historic Civil Rights Act in 1964 and included the iconic photograph of President Johnson offering Dr. King a pen that represented the signing of the act.Footnote 21 At the same time, Iranians confronted racial injustice in America when reading about organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan (“the opponents of Blacks” [mokhalefan-e siyahan]) and the group's declared “sacred war” (jang-e moqaddas) against President Johnson.Footnote 22

Through figures such as Dr. King, other civil rights advocates, and sports icons, Iranians came to know prominent global Black icons. In 1965, Kenyan long-distance runner Kip Keino set the world record in the 5,000 meters and was featured in the popular Persian sports magazine, Kayhan-e Varzeshi (Sports Universe). The article recounted the race in detail and touted Keino's achievement as “the world record falls at the feet of a Black man.”Footnote 23 With even more excitement, Iranians followed the rise of Muhammad Ali (Cassius Clay), who enjoyed immense popularity in Iran during the peak of his career. Clay's victory over Sonny Liston in February 1964 (he had not yet changed his name and announced his conversion to Islam) made front-page news (Fig. 2).Footnote 24 Journalist Parviz Khorsand, writing for a religious-leaning journal, found special meaning in Clay's victory, which gave the boxer a platform to express his support for Islam in pursuit of racial parity.Footnote 25 Over a year later, Ali's TKO victory over Floyd Patterson again raised his stature in Iran. The public was particularly intrigued by the champion's taunting manner during the fight. Clay also stood out for his outspoken views about the Vietnam War, a conflict that polarized Persian intellectuals.Footnote 26

Figure 2. “In the Exciting Clay-Liston Fight for the World Heavyweight Boxing Championship, Liston Was Defeated and Clay Screamed: I Am the Winner!” Ettela‘at, no. 11327, 26 February 1964, 1.

Iran tracked the various phases of the Vietnam War with interest. Unlike the monarch, Iranian writers gravitated to Third World causes that cast America as an imperialist intruder on the world stage, and they commiserated with its battered enemies.Footnote 27 In 1973, the Iranian Students Association of Washington-Baltimore communicated with Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW) to share “some important materials about the real situation in Iran.”Footnote 28 This apparently included information about the arrest and killing of dissidents. Iranian students in the US found sympathetic ears among VVAW members who denounced the shah.Footnote 29

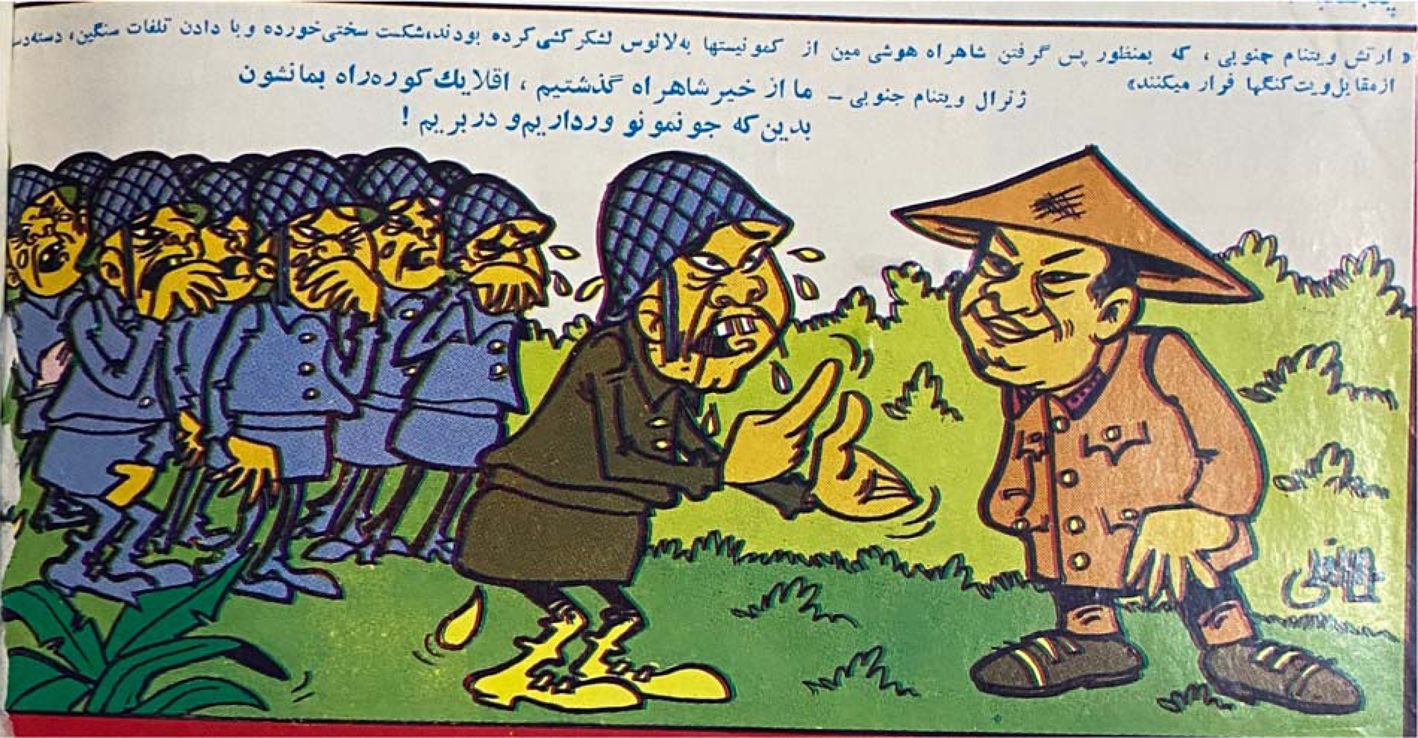

Yet the images of the Vietnamese were replete with racist stereotypes. These caricatures reinforced the ways in which Iranians “othered” East Asian communities, even when trying to express sympathy.Footnote 30 The satirical journal Towfiq pushed the limits on propriety and social norms, including race, which emerged as an important part of its messaging. Its illustrations suggested that many Iranians understood race and racial difference in simplistic, often ignorant and derogatory terms (Fig. 3).Footnote 31 Still, Iranians were finally beginning to see the Vietnam conflict in color and as part of a global decolonization struggle. The coupling of the Vietnam War with the fight for racial parity in South Africa and the United States alienated a skeptical Persian reading public that increasingly regarded American interventions around the world as abetting racial and economic injustice.

Figure 3. “The army of South Vietnam, which had sent troops to Laos to take back the main [Ho Chi Minh] trail from the Communists, suffered difficult defeat and heavy casualties, and fled in flocks from the Viet Cong.” South Vietnamese General to Viet Cong: “We have given up on the Main Trail. At least show us a back road so we can escape and save our lives.” Towfiq 49, no. 50, 4 March 1971.

Decolonization and Anti-Aryanism

In 1962, the influential writer, Jalal Al-e Ahmad published his scathing pamphlet against cultural imperialism called Gharbzadegi (Westernitis), which became a clarion call for cultural reidentification. Born into a religious family, Al-e Ahmad studied literature at the Tehran Teachers College and in 1944 briefly joined the communist Tudeh party. In the 1960s he rediscovered Islam as a cultural force and performed the hajj.Footnote 32 His sympathy for decolonized communities explained in part his critical view of the United States. Around the same time that Al-e Ahmad produced his work, Mohammad Reza Shah published his manifesto, Mission for My Country, an odd mix of memoir, history, and annual report. The shah touted his administrative successes and his efforts to “stamp out corruption.” The king explained his political philosophy and notion of democracy by making a peculiar analogy: “Political democracy can never operate like an electric refrigerator; you cannot just turn it on and let it run.” Instead, he argued, Iranian democracy necessitated a paternalistic approach that recognized the need for “maturity and tolerance,” and, referring to himself, “a sense of mission.”Footnote 33

Through educational and cultural endeavors, America tried to find a way to mediate these incongruities. One of these programs brought Al-e Ahmad to the United States in 1965 on a trip that lasted approximately three months. While visiting Harvard University, Al-e Ahmad encountered James L. Farmer, founder and first director of the Congress of Racial Equality as well as a civil rights activist and proponent of nonviolent protest. Farmer had been invited for a lecture, in which he discussed the necessity of moving past the tropes of Black and white in conversations about race relations in America. Farmer emotionally recalled his trip to Africa, his personal experiences of imprisonment, and his views of African American Muslims, including Malcolm X.Footnote 34 At another session, Harris Wofford, Special Assistant to the President (JFK) for Civil Rights and one of the founders of the Peace Corps, mentioned that approximately 200 volunteers were serving in Iranian villages and that they were being trained for future service in the State Department. The encounters at the seminar enabled participants to consider American responses to racial injustice and social inequality; however, the Peace Corps and other comparable educational exchanges failed to generate significant goodwill or understanding. Iranian students abroad rallied around anti–Vietnam War protests and remonstrated against America's support for a monarch they considered out of touch with populist concerns.

Like his friend Al-e Ahmad, Islami Nodushan also was invited to attend a seminar at Harvard in 1967. This seminar, which lasted about six weeks, included writers and activists from thirty countries. George Lodge, the son of Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., and Henry Kissinger oversaw the gathering. According to Nodushan, participants openly discussed all the complex crises facing the United States, from race to Vietnam. Outside the academic setting, Nodushan had the opportunity to meet Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, and Senator Robert Kennedy. Nodushan wrote that knowing America as a country was a necessity, given its weight in the world. Yet he recognized that America's size and diversity made it difficult to reach facile judgments about it.Footnote 35

As a rich country, Nodushan contended, America attracted false friends and envy. It spent ample sums of money to promote a positive self-image, but with mixed results. Americans were “naive” (sadeh del) and lacked a sophisticated worldview. Only three of its countless newspapers offered global perspective. Television provided most Americans with the daily sound bites they craved. Advertisers (and therefore big business) had a strong hand in communicating the news, which was managed privately. In several paragraphs Nodushan summed up the dilemmas and contradictions of America: “After spending two minutes watching the bloody scenes of the war, the swamps and jungles of Vietnam, the way Viet Cong sympathizers squirm in their blood, the crumbling cottages, and mothers with naked children in tow run for cover . . . suddenly the scene changes.” Americans could carry out crimes out of naivete, yet they held a deep love of liberty. The media (television) controlled America: “Today television is America's king” (padeshah), but Americans “like nothing more than freedom.” Nevertheless they accustomed themselves to a system of freedom built on money—as manifested in the electoral process. At the same time, Americans were deeply self-critical. Nodushan referenced the writings of William Lederer, who coauthored The Ugly American (1958), and cited passages from his A Nation of Sheep (1961), in which the author lambasts the American public for its ignorance of the situation in Laos. That overconfidence, said Nodushan, compelled America to meddle and turn every global conflict into a personal fight.Footnote 36

The year, 1968, stood out as a time of turbulence. The fight for civil rights played out in different ways. The consequential Writers’ Association of Iran (Kanun-e Nevisandegan-e Iran) came into existence, despite state censorship, and identified the “defense of freedom of expression” as a primary objective.Footnote 37 The association reflected the cultural influence of a new group of nonconformist intellectuals who often identified with global anti-colonial struggles.Footnote 38 In April 1968, Tehran hosted the United Nations Conference on Human Rights, a gathering that fell short of its lofty ideals.Footnote 39 Roy Wilkins, head of the NAACP, represented America at the gathering at the behest of President Johnson, who had appointed him to replace Ambassador Averell Harriman, then engaged in talks with North Vietnam.Footnote 40 As Wilkins spoke, the shah's sister, Princess Ashraf, who was presiding over the conference, looked on. A royal reception that included the shah and his queen awaited Wilkins once the speeches concluded The conference, coming on the heels of the tragic assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King on 4 April 1968 in Memphis, Tennessee, served as a sobering reminder of the labors that lay ahead in realizing the ideals of racial equality and universal enfranchisement.

In June 1968 the shah received an honorary degree from Harvard University. Henry Kissinger, a Harvard graduate, and chairman of Harvard's Board of Trustees David Rockefeller likely had a hand in convincing the powers that be to confer the recognition upon the shah. During his commencement address, the monarch proposed the creation of the Universal Welfare Legion, an international organization similar to the Peace Corps. Harvard ignored the signs of controversy that had beset the shah. Coretta Scott King, the deceased civil rights leader's widow, was also at Harvard. She delivered the class day speech and overshadowed the shah.Footnote 41

Iran's Response to Global Racial Justice

In the aftermath of the June 1967 Arab-Israeli war Iran was trying to connect the dots among America's civil rights crisis, its domestic unrest, and its regional role. Iran's split identities—secular and religious, national and regional, imperial and colonized—became reflected in the fractured political writings of the post-Mosaddeq era. Intellectuals with progressive, and at times socialist, leanings continued to watch happenings in Africa and other formerly colonized states with interest. Expressions of ethnic and racial acceptance or opposition grew strident as Iranians engaged with global crises that brought the politics of race heatedly into their backyard. Although the theme of ethnicity had endured as a subject of anthropological and political interest, race and racism rose to the fore as writers of different stripes considered their political affiliations and proclivities. Persian high and popular culture grappled with notions of race and skin color in contemporary society, and ideologies such as “Third Worldism,” Islamism, and socialism informed these intellectual and public debates. Iran also expanded its network of international relations. By 1976, it had pursued diplomatic engagements with several African nations. Iran expanded trade with African countries, in particular South Africa, Mozambique, Kenya, and Zambia, and forged more modest exchanges with Sudan, Ethiopia, and Angola.Footnote 42

Writers of the post-Mosaddeq years explored other facets of race and decolonization. It was during these decades, from the 1960s on, that Iranian intellectuals hungrily read and translated the writings of, Francophone writers such as Léopold Sédar Senghor, Aimé Césaire, Patrice Lumumba, and Frantz Fanon. In a special issue of the influential journal Jahan-e Now (New World), which was dedicated to African culture and liberation struggles, translator Fariborz Majidi delved into the thought of Senegalese president-poet Senghor. Majidi's essay spawned a new Persian vocabulary to express racial pride and négritude (siyah-e zangi budan)—the affirmation of Black African heritage—as articulated by Senghor. Majidi referenced Senghor's speech at Oxford in 1961, in which Senghor described the impact of French colonialism and its failed policy of “assimiliation” (hamanand-sazi).Footnote 43 Another piece referred to the struggles of Angola, as articulated by the refrain of its poet-president António Agostinho Neto (d. 1979), “Victory is certain.”Footnote 44 Through translations of Francophone works, pan-Africanism, Afro-Asian movements, and nonalignment, Iranians molded their conceptions of négritude, bondage, and decolonization.Footnote 45

The writings of Caribbean psychiatrist Frantz Fanon in particular roused young Iranian thinkers drawn to postcolonial discourses. Fanon's seminal works were translated into Persian prior to the Islamic Revolution. In 1970, Mohammad Amin Kardan put forth a Persian rendition of Fanon's Toward An African Revolution (Inqilab-e Ifriqa), published in 1964 after Fanon's death.Footnote 46 In 1973, a literary journal, Sokhan (Speech), introduced Fanon's background and works to the Persian reading public, including his scathing polemic on race relations, Black Skin, White Masks (Pust-e Siyah, Surat-haye Sefid).Footnote 47 A towering intellectual of those years, `Ali Shariati (d. 1977) famously contributed to the translation of Fanon's The Wretched of the Earth (Duzakhiyane Ruye Zamin).Footnote 48 Shariati showed an affinity for the politics of decolonization and fulminated against the oppressive policies that had accompanied imperialist regimes in Africa and elsewhere.Footnote 49 Never entirely comfortable with Iran's history of slavery and racism, many Iranian intellectuals of this era remained silent about this past, which only recently has become a topic of focused academic research.

In Iran, debates surrounding race remained complicated. For much of its modern history, Iran desperately strove to cast itself as an “Aryan” nation and people who belonged to the “white” race. Although European travelers to Iran such as Lady Mary Sheil, wife of the British minister to Persia, saw Iranians as “swarthy,” some Persian writers of the interwar era cast themselves as white.Footnote 50 Like other ethnic groups, Iranians had intermingled with migrating populations, including Africans. In the 1930s, the Third Reich had appropriated the meaning of Aryanism and abused the linguistic distinctions between Aryan and Semitic languages to claim an insidious and false racial superiority for Germans. Regrettably, some Iranian thinkers and bureaucrats tried to follow suit.Footnote 51

After 1945, with the defeat of Hitler's Germany and the demise of Nazism, the Aryan label fell out of vogue. It seems that message failed to reach Iran's sovereign, who, in 1965, took on a grandiose title, Arya Mehr (Light of the Aryans) to project an image of pomp and majesty. In 1965, the parliament had bestowed the title on the shah prior to his coronation two years later.Footnote 52 He followed this move in 1971 with a lavish celebration of Iran's pre-Islamic history and a glorification of the Achaeminid sovereign, Cyrus the Great. To bolster his image, the shah had hoped to bank on the dual legacies of Cyrus: as grand monarch and as advocate of human rights. Unlike the state, however, Iranian writers and activists shunned Aryan discourses and found meaning instead in the stories of dispossessed Blacks in Africa and America and in the anti-colonial struggles of the Third World.

Comparisons between Black liberation movements and modern Persian politics made sense, given the shared histories of oppression and imperialism. In turn, Black activists supported the cause of Iranian students who fought against the shah's regime. The Black Panther Party newspaper adopted an anti-imperialist stance against America's foreign policy interventions, including in Iran.Footnote 53 In 1970, when forty-one Iranian students awaited trial in San Francisco for having stormed the Iranian consulate to protest the visit of Princess Ashraf, the shah's sister, the Panthers wrote in their support.Footnote 54 The princess had come to the United States to participate at the United Nations, where she was elected chairwoman of the UN Human Rights Commission. The Panthers lambasted the police for its aggressive tactics in breaking up the protests, which left a student wounded in one eye.Footnote 55

In the realm of the arts, African American musicians became cultural ambassadors to Iran. In August 1970, the gospel group the Staple Singers performed at the Shiraz Arts Festival (Fig. 4).Footnote 56 Critics noted that the musicians “stole the thunder” from such luminaries as Ravi Shankar of India, the Julliard String Quartet, and the Senegal National Ballet. Reportedly at the concert “shouts of ‘vive les Noirs’ (translation: long live the Blacks) could be heard above the stomping, whistling and yelling throng that gave the Staple Singers standing ovation after standing ovation.”Footnote 57 A Persian review observed that the Staple Singers had earned “a special spot” (makan-e khassi) in the festival and that their music gave voice to their deepest pain and joy. This piece poignantly interpreted the doleful messages embedded in the songs the group performed, including the “beautiful” and “sad” tune, “Why Am I Treated So Bad?” Iran opened itself to African American culture through its embrace of gospel music and international sports.

Figure 4. “Musical Group Staple Singers” at the Shiraz Arts Festival. Sokhan 20 (1970): 471.

Still, the shah and his Iran remained a bundle of contradictions. Even as the monarch took on the sobriquet Arya Mehr, he expanded Iran's ties with numerous African countries. In the 1970s, he embarked on an ambitious project to develop petrochemical technologies with Senegal.Footnote 58 In 1976, when President Senghor visited Iran, at the University of Tehran an evening was devoted to his writings and to Senghor's identity as a poet rather than politician. Senghor was awarded an honorary degree from the College of Literature of Tehran University.Footnote 59

Islami Nodushan gave a speech in which he compared Senghor's ideas with themes in Persian mysticism and contributed to a Persian vocabulary for talking about Blackness (siyah budegi) and African colonial struggles. Nodushan began his talk by recognizing the brave struggles for independence that were unfolding on much of the African continent. He explained Senghor's concept of négritude as a desire to embrace the Black identity and to help it blossom. Citing Jalal al-Din Rumi, Nodushan argued that Persian mysticism, although distinct from the expressions of sensuality of Black culture, also differentiated itself from the Aristotelean philosophy of rationality. In his poetry Rumi juxtaposed the outward meaning of truth (ẓāhir) with its hidden or inward meaning (bāṭin). In contrast to Senghor's explanations about the importance of sensuality in Black experiences, Nodushan viewed Rumi's mysticism as suggesting that senses could deceive and reason thus prevailed. Despite these differences, Nodushan concluded that in the context of illumination and revelation the similarities between the philosophy of négritude and Persian mysticism remained undeniable.Footnote 60

Conclusion: #Black Lives Matter

The connection between Iranian politics and race relations is not of recent vintage. Despite the state's desire to cast Iran as a “civilized” and “white” nation, Iranians would never be accepted in the commonwealth of (white) Western nations. This realization provided the impetus to Iranian intellectuals, and even to the shah himself, to find common cause with non-Western or colonized communities, from Africa to the Americas. Paul Robeson, Jalal Al-e Ahmad, ʿAli Shariati, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, and Ruhollah Khomeini each recognized that modern experiences of dispossession united communities of color through their familiar struggles for liberation and equality.

In May 2020, the killing of George Floyd by Minnesota police officers unleashed a maelstrom of protest across America. The murder sparked Iran's foreign minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif, to tweet in support of the Black Lives Matter movement. As Zarif, who had spent about eleven years in the United States as a student, expressed it, “Some don't think #BlackLives Matter. To those of us who do: it is long overdue for the entire world to wage war against racism.” Zarif had seized the opportunity to hit on America's sensitive nerve. No sooner had Zarif tweeted his message than the former secretary of state, Mike Pompeo, delivered his salvo: “You hang homosexuals, stone women and exterminate Jews.”Footnote 61 This was not a flattering portrayal of either country. America's appetite for racism had badly marred its civilizational legacy, whereas the Islamic Republic's intolerance of social difference, and its penchant for the power-grab, had sullied its lofty revolutionary ideals.

Whatever Zarif's intention, his solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement hearkened back to a strand of political thought that Iran's prerevolutionary intellectuals had voiced. Iranian memories of decolonization appeared in unexpected places. Persian poet Mahmud Mosharraf Azad Tehrani (d. 2006), known as “M. Azad,” recalled in his poem, “Bar Bolandtarin Qalehhayeh Donya” (Upon the World's Tallest Castles), Patrice Lumumba, the first prime minister of the Republic of the Congo.Footnote 62 These bystanders watched as the United States and the Soviet Union seemingly divided Africa and the rest of the world into zones of manipulation and control during the Cold War, with ill effects for societies in the crosshairs.

Race relations provided an unanticipated and missed opportunity for collaboration. Although diplomats like Henry Kissinger recognized that Iranian intellectuals—a class often maligned by a suspicious shah—might be harnessed to advance America's image as the beacon of democracy, they failed to engage them deeply in conversations about race and decolonization. At home, Iranians’ desire for equality and upward mobility converged with these broad global movements and led to reforms and outright revolt. The shah, with nudging from the Kennedy administration, addressed disparities in Iranian society, but with mixed results. His reforms did not acknowledge adequately a changing world. As in America, Iranians yearned for new opportunities, economic advancement, and the freedom to shape their country's political future. But their often dissenting voices went in one ear and out the other, and the Pahlavi state did not sufficiently resolve socioeconomic disparities. At that time, the Pahlavi record could not be compared with the shortcomings of a post-Pahlavi regime that would widen some of these chasms in unforeseen ways.

The shah stayed tone-deaf about the underlying roots of discord. But race mattered, even to him. In 1979, as the revolution unfurled, Ayatollah Khomeini pointedly assented to the early release of African American hostages and justified his decision by speaking to their persistent persecution in America: “Blacks for a long time have lived under oppression and pressure in America.”Footnote 63 Khomeini catenated the disenfranchisement of African Americans with the suffering of Iran's weak and dispossessed classes (mostaz‘af). In doing so, he too targeted America's vulnerable past. Race relations, although rarely the lead story in Iranian diplomacy, gripped the middle classes. Iran's new generation saw beyond the West's white ambassadors and found affinity instead with the world's Black citizens.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank IJMES editor Joel Gordon for his indispensable support and assistance in preparing this article for publication. I benefited enormously from his insights and editorial suggestions. I am also grateful to Pardis Minuchehr for her comments on an earlier draft. I accept all responsibility for any inadvertent errors.