I. INTRODUCTION

The idea of “church autonomy” has risen to prominence in law and religion discourse in recent years.Footnote 1 This is the idea that religious groups enjoy a sphere of autonomy in which they can make decisions about matters such as employment, membership requirements, and internal structures free from state interference or control. They enjoy autonomy to control their own membership, leadership, rules, structure, and ethos. The recent discussion of church autonomy has been fueled by several court cases. In 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court's judgment on Hosanna-Tabor v. EEOC recognized the existence of a “ministerial exception,” a doctrine grounded in the First Amendment that renders aspects of the relationship between ministers and churches beyond the scope of secular law.Footnote 2 In particular, the Court ruled that churches’ ministerial decisions were exempt from anti-discrimination legislation. Various church autonomy cases have also been considered in Europe in recent years. For example, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) ruled in Obst v. Germany (2010) that the Mormon Church was permitted to dismiss its European public affairs director for having an extramarital affair, while in Fernández Martínez v. Spain (2014) it ruled that a Catholic priest who was a teacher of Catholic religion and ethics and whose contract was governed by the Catholic church could be refused a renewed contract due to his publicly representing a reform group that the Bishop deemed to have goals that contradicted the teachings of the Church.Footnote 3 In both of these cases, the ECtHR justified its decisions by appeal to the collective dimension of religious freedom, arguing that the associative life of religious communities was protected against certain kinds of state interference. In particular, the Court argued that a principle of religious autonomy prevented the state from obliging religious communities to admit or retain unwanted members, office-holders, or employees.

Defenders of church autonomy—or religious group autonomy more broadlyFootnote 4—argue that it is an essential component of religious freedom. Rex Ahdar and Ian Leigh point out that individuals’ religious lives are often dependent on the vitality of the groups to which they belong, and argue that this vitality requires those groups to have some independent autonomy.Footnote 5 Echoing this thought, the ECtHR has stated that “were the organizational life of the community not protected by Article 9 of the [European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)], all other aspects of the individual's freedom of religion would become vulnerable.”Footnote 6 Freedom of religious association requires that religious groups can structure their internal organization according to their own beliefs and doctrines, set their own standards for membership and leadership, and discipline and dismiss those who contravene those standards. The case for church autonomy is further bolstered by concerns regarding the non-establishment of religion, and non-entanglement between church and state. The state should not adjudicate controversial theological questions or decide between competing conceptions of a religious doctrine, and this limits its capacity to interfere in cases involving such intramural disputes. Churches should be run by their duly constituted authorities, not by legislators.Footnote 7 Overall, then, as Douglas Laycock puts it, “the reason these decisions are beyond the jurisdiction of government is to protect religious believers and to protect churches from government interference.”Footnote 8

The ministerial exception, in particular, is seen by many as a vital guarantee of religious organizations’ ability to govern their own affairs and control their own doctrines, purposes, and structures. Ministers have a distinctive role as those who publicly represent the church and present its message, and thus churches must be granted exclusive authority to decide who is fit to fulfill this role. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit has stated that “the relationship between an organized church and its ministers is its lifeblood.”Footnote 9 Thus, the Supreme Court argues that

[r]equiring a church to accept or retain an unwanted minister, or punishing a church for failing to do so, intrudes upon more than a mere employment decision. Such action interferes with the internal governance of the church, depriving the church of control over the selection of those who will personify its beliefs.Footnote 10

Nicholas Hatzis makes the same kind of argument:

A minister is unlike any other employee, as he or she occupies a position at the center of collective religious life within the church, and his or her work is directly linked to the substance of religious faith. … Therefore, secular interference with clergy selection risks undermining the ability of religious groups to fashion the content of their beliefs and communicate it to the wider public.Footnote 11

This free exercise argument can again be bolstered by a non-establishment argument. Ira Lupu and Robert Tuttle write that the ministerial exception “is driven … by the long-standing doctrine of judicial abstention from deciding purely ecclesiastical questions.”Footnote 12 It rightly “forecloses judicial inquiry into the criteria that religious communities use to measure eligibility for positions involving communication of the faith.”Footnote 13

Some defenders of church autonomy present the view in very strong terms, speaking of the “jurisdictional sovereignty” of religious organizations and matters of church governance being completely beyond the state's competence or jurisdiction.Footnote 14 As others have pointed out, the language of “jurisdictional sovereignty” is to a certain extent rhetorical.Footnote 15 No one seems to deny that states have ultimate decision-making authority, or that some kinds of regulation of religious organizations are perfectly acceptable. No one thinks that churches should be completely exempt from planning laws or laws against fraud. And more importantly, no one thinks they should be exempt from laws against child abuse or sexual harassment.

Nonetheless, various scholars do defend a strong form of church autonomy, according to which certain kinds of decisions by religious organizations lie completely beyond the purview of the state. Courts should not inquire in any way into decisions that churches make concerning membership or leadership, for example. A strong form of the ministerial exception would hold that the relationship between ministerial employees and churches is not covered by any employment laws.

Critics have pushed back against this idea in the strongest terms. Jessie Hill argues that claims to church sovereignty are potentially limitless, making them deeply problematic.Footnote 16 Leslie Griffin speaks of the “sins” of Hosanna-Tabor and the dire consequences of the ministerial exception for many employees, arguing that the Supreme Court has “lost sight of individual religious freedom”Footnote 17 and “mistakenly protected religious institutions’ religious freedom at the expense of their religious employees.”Footnote 18 Cécile Laborde calls the ministerial exception as an “exorbitant right.”Footnote 19

Nonetheless, few think that religious organizations should enjoy no exemptions, or that the idea of religious group autonomy has no merit or weight. Few believe that the Catholic Church should be prosecuted for sex discrimination on the basis of its male-only priesthood.Footnote 20 Even those who reject the ministerial exception thus generally accept that there is something distinctive about the relationship between church and clergy, such that ministers are not simply treated the same as an ordinary employee of a business.Footnote 21 There seems to be broad agreement that religious organizations should enjoy some degree of autonomy in organizing their internal affairs, as part of protecting the religious and associational freedoms of their members and the separation of church and state.

This highlights a fact that is often obscured within the debate between advocates and critics of church autonomy: religious group autonomy is not an all-or-nothing matter, and the ministerial exception can come in a variety of strengths. For example, there are a variety of different kinds of inquiry that courts might conduct in response to legal complaints brought by (former) employees of religious organizations. While defenders of the strong form of the ministerial exception argue that courts should not engage in any examination of such cases, and some U.S. court decisions suggest likewise, recent European cases illustrate that judicial examination can come in various different forms, and there are important arguments to be had about the merits of each.

This article aims to distinguish between these different kinds of judicial examination, and to consider each in the light of the arguments for religious group autonomy. I will offer a typology of forms of both procedural and substantive judicial examination of religious groups’ decisions—focusing in particular on their employment decisions.Footnote 22 I will then argue that several of these forms of examination are indeed ruled out by a proper concern for religious group autonomy. Courts should not apply strict independent standards of procedural fairness, seek to interpret the group's religious criteria for employment and dismissal, substantively evaluate the reasons offered in support of the group's decision, or engage in an all-things-considered judgment concerning the balance that the group struck between the competing considerations and interests bearing upon the case. However, several other kinds of judicial examination are compatible with the values underlying religious group autonomy, and thus courts can permissibly engage in them. These include checking that the group's decision making followed its own specified formal structure, applying minimal independent standards of procedural fairness, checking that the stated reasons for the decision were not merely pretextual, such that there was a genuine religious reason for the decision, and ensuring that the group engaged in some kind of balancing of relevant interests. The overall picture that emerges from this is more complex than the straightforward advocacy or rejection of church autonomy or the ministerial exception often seen within the literature. But it is a picture that actually fits better with the legal reality in Europe, and suggests that recent ECtHR jurisprudence has generally succeeded in respecting legitimate religious group autonomy while engaging in permissible forms of judicial examination and evaluation of such groups’ decisions.

One final introductory comment. This article focuses on judicial examination. Protections of religious group autonomy can also be written into statutes, for example through exemptions from anti-discrimination legislation. My arguments could be used to support some such exemptions. But the kinds of cases we are considering here will generally involve interpretations of these statutes, or conflicts of rights (as seen in ECtHR cases). These specific disputes will have to be handled by courts, which is why this article is framed in terms of identifying and assessing the kinds of judicial examination courts could undertake when such disputes arise.

II. TAXONOMY OF JUDICIAL EXAMINATION

Let us imagine a case where an individual employed by a church is fired and sues the church on the grounds that her dismissal violates an anti-discrimination statute. The church denies this, arguing that the employee had proven herself unfit for office—by violating a standard of moral conduct,Footnote 23 teaching or endorsing views that are incompatible with the faith,Footnote 24 or refusing to submit to internal decision making and dispute resolution procedures.Footnote 25 How might the court go about examining this case, in order to reach a decision on the discrimination claim?

One option is to undertake no examination of the facts of the case at all, beyond establishing that the ministerial exception applies. Churches have rights against judicial interference with their employment practices, in order to protect religious freedom and avoid state entanglement with religion. It is not up to the courts to decide who is suitable or qualified to be a minister, so as long as this employee is within that category, her case is dismissed. This approach can be seen in various U.S. cases. For example, in 2003, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, dismissed the complaint of Gloria Alicea-Hernandez, a Hispanic liaison officer for the Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago who had resigned and sued for constructive dismissal, claiming that she had been discriminated against on the basis of both her national origin and gender.Footnote 26 The Court ruled that the ministerial exception applied, in the light of Alicea-Hernandez's responsibility for conveying the message of the church to the wider community, and thus rejected her claim for lack of subject matter jurisdiction, without considering the merits. Many other cases falling under the ministerial exception follow this pattern. The doctrine “precludes any inquiry whatsoever into the reasons behind a church's ministerial employment decisions.”Footnote 27

Even in the United States, however, there are limits to the protection afforded by the ministerial exception. First, it only covers “ministers.” This means that courts must make decisions concerning who counts as a ministerial employee, and there has been some disagreement about this matter. For example, in Kant v. Lexington Theological Seminary, the Kentucky Court of Appeals ruled in 2012 that a Jewish professor at a Christian seminary counted as a (Christian) minister, since his primary duties consisted of “teaching religious-themed courses” to “students who desired to become involved in Christian ministry” and the purpose of his position “was to fulfill [the seminary's] mission.”Footnote 28 Kentucky's Supreme Court overturned this decision in 2014, on the grounds that Kant “did not participate in significant religious functions, proselytize, or espouse the tenets of the faith on behalf of his religious institutional employer.”Footnote 29 Both courts agreed that whether Kant was a ministerial employee depended on the substantive nature of his work, and thus an assessment of this was required in order to decide the issue.

The U.S. Supreme Court entered the debate as to who counts as a ministerial employee in Hosanna-Tabor, where it ruled that claimant Cheryl Perich, a “called” teacher at a Lutheran school, qualified as such. This was based upon “the formal title given Perich by the Church, the substance reflected in that title, her own use of that title, and the important religious functions she performed for the Church.”Footnote 30 In his concurrence, Justice Alito (joined by Justice Kagan) offered further specification as to the functions one must fulfill to qualify as a ministerial employee: “The ‘ministerial’ exception … should apply to any ‘employee’ who leads a religious organization, conducts worship services or important religious ceremonies or rituals, or serves as a messenger or teacher of its faith.”Footnote 31

A second limit on the protection currently afforded by the ministerial exception is that the Supreme Court in Hosanna-Tabor stated that it was only affirming the exception for discrimination cases. The Court was explicitly agnostic with respect to tort claims or breach of contract. Different courts have reached different judgments concerning whether the ministerial exception does also cover those kinds of cases. In a case considered alongside Kant, Kirby v. Lexington Theological Seminary, the Kentucky Supreme Court found that Kirby was a minister, but there was still a question of fact regarding whether he had a contract and whether it was breached, and this could be determined without violating the ministerial exception, since that exception did not preclude breach of contract cases.Footnote 32

Nonetheless, on the approach taken by U.S. courts, once the claim has been shown to be within the scope of the ministerial exception, further judicial examination is precluded, and the church wins. This is not the approach taken by the ECtHR, however. While explicitly affirming the importance and weight of church autonomy concerns, and indeed their status within Article 9 of the ECHR, the ECtHR has also emphasized that in cases of conflict with other Convention rights, a fair balance must be struck. Other Convention rights—including rights against discrimination—can justifiably be infringed in order to protect religious group autonomy, but only when the infringement is shown to be a proportional means of achieving the legitimate end of collective religious liberty. Non-proportional interferences constitute wrongful violations of the competing right(s).

The European Court of Justice (ECJ) has reached a similar verdict, most notably in the recent case Egenberger v. Evangelisches Werk.Footnote 33 The ECJ held that national courts must check that religious occupational requirements are “genuine, legitimate, and justified,” in the light of the employer's religious ethos and right of autonomy.Footnote 34 Religious groups cannot discriminate in their employment decisions, even with respect to religion, without having a justification that shows that they are not violating workers’ rights against such discrimination. Similarly, they cannot impose requirements that employees comply with religious teaching unless this imposition is justified by their ethos.Footnote 35 Again, they must show that such requirements are proportional.

So what kinds of examination might a court undertake in order to determine whether the requirement or interference was proportional? We can identify two broad kinds of investigation—procedural and substantive examination of the church's decision making—which can then be further subdivided. The rest of this section lays out a taxonomy of these various kinds of judicial examinations and their motivations. The following sections consider the permissibility of each kind, at the bar of respect for religious group autonomy.

A. Procedural Examination

The basic thought here is that while churchesFootnote 36 have the right to base their employment decisions on their own standards—including standards that would be deemed unjustly discriminatory in other contexts—they must apply those standards in a fair way and follow acceptable procedures in making their decisions. There are two forms of procedural examination:

(a) Examination of whether the church followed its own employment procedures. The concern here is with verifying that the church followed the procedures for handling disputes and dismissing employees detailed in relevant contracts, policy documents, and so on. This again might have two aspects:

(i) Checking that the church's procedures follow the specified formal structure—e.g., written warnings, disciplinary hearings, the specified notice and forms of communication, and so on.

(ii) Checking that the church applied its stated standards to justify its decision, such that the decision was based on the kinds of reasons for dismissal that the church has committed itself to.

(b) Examination of whether the procedures followed by the church satisfied independent standards of procedural fairness. This might include applying standards of evidence (e.g., evidence for the claimant's purported wrongdoing) and transparency (e.g., following transparent decision-making procedures, offering clear reasons for decisions), ensuring that the employee was given the opportunity to reply to accusations and offer her side of the story, and imposing requirements to give sufficient warnings and time for correction prior to dismissal. The examination involved here will obviously vary with the precise standards applied, which could range from fairly minimal to highly demanding.

The difference between (a) and (b) is that the standards applied in (b) are independent standards of procedural fairness that are viewed by the court as essential for a decision to be legitimate, whereas the standards applied in (a) are those that the church itself has explicitly committed to. These can clearly come apart. A church could pass (b) but fail (a), due to committing itself to procedural standards beyond those that the court applies in (b) and failing to follow those procedures. Equally, a church could pass (a) but fail (b), in cases where it follows its own procedures, but those procedures are deemed to fall short of the necessary independent standards.

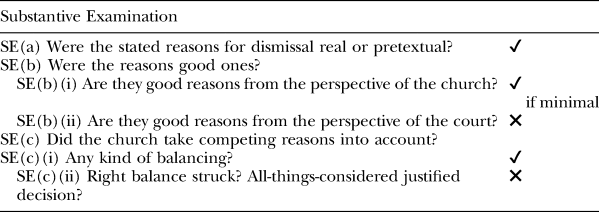

B. Substantive Examination

The basic thought here is that while churches have the right to make their own employment decisions, they must have adequate reasons for those decisions. The decisions must not be arbitrary or based on unsatisfactory reasons. There are several different kinds of substantive examination courts could undertake, which vary depending on what are taken to be “adequate reasons.”

(a) Evaluating whether the stated reasons for dismissal were the real reasons, or whether they were merely pretextual. Here courts check that the decision was sincerely made on the basis of the church's (religious) criteria, rather than those criteria being used as cover for other motivations.

(b) Evaluating the positive reasons for dismissal offered by the church. Are they good reasons for dismissing the employee? There are two possible understandings of “good reasons” here:

(i) Are they good reasons from the perspective of the church itself? Are they justified by the church's own doctrines and tenets? This evaluation would overlap with procedural examination (a)(ii), but it is not precisely the same. Procedural examination (a)(ii) concerns whether the church acted on standards of judgment specified within documents relating to its employment procedures, while the substantive examination here is a broader evaluation of whether there are justifications for the church's conduct within its doctrines and beliefs. Of course, the church may include general clauses within its employment documents that state that employees can be dismissed for failing to live up to the church's doctrines or acting contrary to its beliefs,Footnote 37 in which case there will be extensive overlap between these two forms of examination.

(ii) Does the court consider the reasons offered to be good ones, based on its own standards? Here the court directly evaluates whether it considers the reasons for the church's decision to be adequate to justify that decision.

(c) Evaluating whether the church adequately took into account countervailing reasons, such as the rights and interests of the employee. Again, there are two versions of this:

(i) Checking whether the church engaged in any kind of balancing of the relevant interests and reasons.

(ii) Deciding whether the balance struck by the church was justified, or whether the balance of reasons actually favored a different decision—i.e., not dismissing the employee.

The difference between the two kinds of evaluation under (c) is that (i) simply checks that the church took into consideration the range of reasons that applied to its decision, whereas (ii) imposes a higher bar by requiring that the church strike a well-justified balance between those reasons. (i) could be satisfied by a church that placed relatively little weight on the cost to the employee of losing her job, but at least recognized that this cost had some bearing on its decision, whereas (ii) would require the church to give this consideration whatever the court considers to be its proper weight. In other words, (ii) gives the church a lesser “margin of appreciation” within its decision making. Of course, there is a range of possible margins of appreciation that a court could give under (ii).

This completes my taxonomy of possible forms of judicial examination in response to a discrimination complaint against a church's decision to dismiss an employee. This taxonomy is summarized in the table overleaf.

III. SUBSTANTIVE EXAMINATION

What should we make of these various forms of examination, from a normative standpoint? In this section, I will consider substantive examination, before turning to procedural examination in the next section.

As we have seen, there are two main concerns underlying religious group autonomy in this context. First, the importance of groups being able to choose their own leadership and membership, as part of their freedom to control their own structures, doctrines, and ethos—a central aspect of religious freedom. Second, the fact that we do not want courts to assess the merits of religious reasons, or to be entangled in theological adjudication. It is not up to courts to decide what is a good reason for religious organizations to act upon, or to take sides in theological disputes.

Table 1. Taxonomy of Judicial Examination.

These ideas are well captured by Laborde's concept of associational “coherence interests” and “competence interests.”Footnote 38 Coherence interests are interests that associations have in living by their own standards, purposes and commitments, while competence interests are interests in interpreting what those standards, purposes, and commitments require.Footnote 39 These interests justify a level of autonomy for associations in structuring their activities around their own beliefs, and a level of judicial deference to their decisions in areas such as employment. For example, it is not up to courts to decide what qualities an individual must display in order to be a minister. Courts “lack the competence properly to evaluate the ‘gifts and graces’ of a minister. Only religious associations have the competence to interpret such qualities, and courts must accept the prima facie validity of the religious justifications proffered by the church.”Footnote 40

Concern for these associational interests rules out substantive examination types SE(b)(ii) and SE(c)(ii)—the court asking whether the reasons that the church acted upon were good ones from the perspective of the court, and whether the church struck the right balance between the relevant considerations. Both of these involve an evaluation of the merits of the reasons for dismissal, thus denying the church the freedom to make such decisions on the basis of its own standards, and its own understanding of those standards.

SE(b)(ii) invites courts to impose their own standards when assessing the church's decision, by making judgments such as that the employee's conduct that the church deemed immoral was not sufficiently heinous, or that the employee's teaching was not sufficiently objectionable, to justify dismissal. Importantly, under SE(b)(ii) judgments are made not in the light of the church's beliefs, but based on the court's own assessment of the employee's actions. This substitutes the church's values with those of the court, and so fails to respect the church's coherence interests.

SE(c)(ii), meanwhile, requires courts to weigh the strength of the reasons for dismissal, since this is necessary in order to evaluate the overall balance of reasons. The court could do this in one of two ways. First, it could interpret the church's own standards, and thus the extent to which the employee has fallen short of those standards. This would be to engage with a matter that is beyond its competence, especially since the examination here would need to be fairly detailed in order to reach a verdict on the strength of the reasons for dismissal. Second, it could appeal to its own judgments of the strength of those reasons. This would involve the same kinds of judgments as in SE(b)(ii), so again impose the court's own standards upon the church. SE(c)(ii) thus fails to respect either the church's competence interests or its coherence interests (or both).

Importantly, however, respect for coherence and competence interests does not rule out all kinds of judicial examination of churches’ employment decisions. For example, Laborde notes that “if a religious association asserts in its defense that a minister violated a tenet against adultery, this is an objectively testable religious justification.”Footnote 41 Such a justification might be thought to be objectively testable in two senses. First, it might be objectively testable whether there is adequate evidence for the claim that the minister committed adultery. Court investigation of this question involves a procedural examination, which I consider below. Second, it might be objectively testable whether the religion in question considers adultery to be immoral and thus grounds for dismissal. Importantly, the test here is not whether adultery is in fact a good reason for dismissal; that would be SE(b)(ii), and a violation of the church's coherence interests. Instead, the question is whether the church believes adultery to be such a reason. This is SE(b)(i).

There is a parallel to SE(b)(i) in the case of individuals who claim exemptions. There, many theorists hold that those claiming exemptions should be required to show that they have a sincere religious belief that conflicts with the relevant law or rule, and some even argue that the strength of their claim for an exemption partly depends on the status of this belief—whether it concerns a religious obligation or merely a religious preference, and whether it concerns a core or peripheral element of their faith.Footnote 42 Churches could similarly be required to show that they have a sincere religious belief that gives them reason for dismissing the employee. The court is not required here to pass its own judgment on this reason, but simply to ascertain that it is indeed grounded in the religion's beliefs or doctrines. To use Laborde's example, the court can check whether the church's teachings do indeed include a prohibition on adultery (by ministers or employees). The justification for this kind of examination is that religious organizations should not be able to dismiss employees with impunity, especially when there is a suspicion of discrimination. Protecting employees from discrimination (and from other forms of unfair treatment) is important enough to require that churches show that their decision has warrant on the basis of their beliefs, rather than being arbitrary.

This kind of requirement is reflected in Schedule 9 of the UK Equality Act 2010, which details exceptions from the law's requirements. Paragraph 2 exempts employment requirements relating to sex, marital status, and sexuality imposed by religious organizations, on the condition that these requirements are applied either “so as to comply with the doctrines of the religion” (the compliance principle) or “to avoid conflicting with the strongly held religious convictions of a significant number of the religion's followers” (the non-conflict principle). Checking whether the compliance and non-conflict principles are fulfilled involves examination of type SE(b)(i).

This kind of examination seeks to respect coherence interests, since the court is not challenging the church's freedom to live by its own standards or commitments, but is simply checking that those commitments do indeed support the decision that it has made. Concerns about entanglement and court incompetence—i.e., about violating competence interests—are not absent here, however. Deciding whether there is a justification for the decision based on the church's doctrines must involve some interpretation of those doctrines. One might argue that courts are not able to determine whether the church does in fact have the relevant belief or doctrine without taking sides in theological disputes, since there will undoubtedly be disagreement about this matter among the religion's followers, and even among the congregants (and leaders) of the specific church. The court must decide whose views to accept as authoritative. It thus becomes the arbiter of whether the employee's views are theologically heterodox, based on its understanding of the religion.

This kind of concern is perhaps reflected in the UK Equality Act's non-conflict principle, which allows for requirements that are based on the beliefs of the religion's followers rather than needing to be shown to be objectively grounded in religious doctrines. In the kind of case we are imagining, however, there is a question of whether it is the views of the members of the specific church, or church leaders, or members or leaders of the denomination as a whole, or even of particular theological experts, that should matter.

In my view, these concerns mean that the only acceptable form of examination falling under SE(b)(i) involves requiring the church to make a plausible case that its decision reflected a religious belief or doctrine. This does not mean that the relevant belief has to be uncontroversial, even among the denomination or specific church in question. And the evidential bar here should not be set particularly high. This should be considered a fairly minimal requirement, rather than any kind of detailed examination of the strength of the theological justification for dismissal. The church can present evidence from various sources, including scripture, its public teachings, relevant theological materials, and its past responses to similar conduct. Courts should not interrogate these sources in detail or investigate alternative interpretations, since the aim is not to establish the overall plausibility of the theological case, or the overall strength of the reasons for dismissal. The aim is simply to ascertain that the church acted on what it genuinely took to be good reasons. Therefore, as long as the church's case is reasonably plausible, this should be considered sufficient. This approach respects competence interests, while also ensuring that the church has a sincere justification for its decision.

When SE(b)(i) is specified in this way, it actually comes close to being equivalent to SE(a)—a pretext test. Laborde also defends this kind of examination, writing that “[w]hen courts inquire into whether a religious reason is used as a pretext for an employment decision, they are not automatically becoming entangled in theological questions over which they do not have competence.”Footnote 43 This is because “the question is not whether the asserted reason is true, but whether the defendant believed it to be true when he took the challenged action: it is an enquiry into sincerity, of the kind that are common in cases of individual freedom of religion.”Footnote 44 In other words, the pretext test involves a basic substantive examination of whether there is a sincere religious reason for the dismissal. This again requires the church to show that there is such a reason, in the way I described in the previous paragraph.

We should note here that the pretext test might also involve some procedural examination of whether there is evidence that some other reason—such as discriminatory reasons—actually motivated the decision. This kind of examination is acceptable only if burden of proof for the church is low. Courts should not engage in complicated judgments regarding precisely what considerations motivated the decisions of each individual involved. Usually, passing examination SE(b)(i) should be enough to pass the pretext test. But courts should be alert to cases where the religious reasons for the decision were only produced subsequent to the employee lodging a complaint and there is clear evidence that other reasons were actually behind the decision.Footnote 45

The U.S. Supreme Court has ruled out any kind of pretext text or judicial examination of whether the church had good reasons for dismissal from its own perspective, at least in discrimination cases. In Hosanna-Tabor, Perich argued that the asserted religious reason for her firing was pretextual. In response, the Court held that that this suggestion

misses the point of the ministerial exception. The purpose of the exception is not to safeguard a church's decision to fire a minister only when it is made for a religious reason. The exception instead ensures that the authority to select and control who will minister to the faithful—a matter “strictly ecclesiastical”—is the church's alone.Footnote 46

This seems to rule out not only the kinds of substantive examination we are presently considering (SE(a) and SE(b)(i)), but all kinds of judicial examination. The Court held that the ministerial exception is not intended merely to protect churches’ religious freedom, permitting them to fire ministers on the basis of their religious beliefs, but gives them license to fire ministers for whatever reasons they desire (or indeed for no reason at all). Some defenders of church autonomy have made similar suggestions. Laycock writes that

when a church does something by way of managing its own internal affairs, it does not have to point to a doctrine or a prohibition or a claim of conscience in every case. It can make out a good church autonomy claim simply by saying that this is internal to the church.Footnote 47

On this view, church autonomy claims are distinct from conscientious objection claims—they are about a category of decisions that are churches’ alone to make, rather than a conscience-based argument that some particular decision should be respected on grounds of reflecting sincerely held religious beliefs. Laycock grounds this view in the free exercise of religion. Justice Alito, meanwhile, in his concurrence to Hosanna-Tabor, grounds it in non-establishment, arguing that any examination of whether the church was acting on a genuine religious tenet would amount to the court inappropriately acting as judge of the nature of the church's beliefs.Footnote 48

Neither of these arguments is wholly convincing, however. It is not clear how an appeal to religious freedom can justify churches making ministerial decisions on the basis of any and every reason that they choose. And it is not clear why courts cannot make judgments concerning the sincerity of a claimed religious belief without judging the truth of that religious belief. Courts can engage in a pretext test without becoming entangled in theology, and concern for the rights and interests of employees seems to give good reason for this minimal kind of substantive examination.

Of course, there are concerns about court's capacity to engage in this kind of examination in an appropriately sympathetic way or without slipping into a more thoroughgoing form of substantive examination that infringes the church's competence interests. It is vital that the court is alert to the need for proper deference whenever competence interests are engaged. Further, such interests might be engaged more often than it appears at first glance. Julian Rivers warns that “disputes between individual ministers or other workers and their religious organizations which present as problems of discrimination in employment almost always reflect deeper underlying internal debates about religious doctrine and practice.”Footnote 49 This should always give courts pause before interfering, but it does not completely rule out judicial examination.

Overall, then, I think we should cautiously endorse SE(a), and a version of SE(b)(i) that largely amounts to the same thing. But the reasons for caution might well mean that the U.S.-style bar on these forms of examination is preferable in cases involving ministers proper—i.e., priests, rabbis, imams, church pastors, etc.—where the concern with protecting church autonomy is most acute, as a way of ensuring that the fundamental components of coherence and competence interests are adequately protected. In this narrow range of cases, all substantive examination should be ruled out. Many cases, including many that have been deemed to fall under the ministerial exception in the United States, involve employees who are not ministers sensu stricto (or indeed at all). In this broader range of cases, examination types SE(a) and SE(b)(i), in the minimal sense that I have specified, are justified. Of course, the reasons that the church can present in response to these forms of substantive examination will likely partially depend on the employee's role. The church's understanding of the way that role relates to its religious mission and ethos will be relevant in seeking to show that its employment decision was justified by its beliefs. It is easier to show the importance of an employee complying with church teachings if that employee performs functions that the church considers religiously important (which can of course go beyond preaching and pastoring), as opposed to tasks that are distant from the church's mission. The employee's specific job will thus always be relevant, since it will be one factor shaping the answer to SE(a) and SE(b)(i).

I have not yet addressed substantive examination type SE(c)(i)—checking whether the church engaged in any kind of balancing of the relevant interests. The justification for this form of examination is that the church should be required to take into account the rights and interests of their employees when making employment decisions. They should not make decisions with absolutely no concern for the effects that those decisions will have. The church must therefore show that they engaged in some kind of weighing process or gave some kind of acknowledgement to the countervailing interests of their employee.

Laborde again mentions this kind of examination approvingly, noting that the ECtHR has “held that religious associations must also consider the right to privacy, family life and employment prospects of employees”Footnote 50 when making their decisions. Those decisions must reflect some weighing of these various interests. For example, in the Fernández Martínez case, the ECtHR held that there had not been disproportionate interference with the priest's private life, and that national courts’ ruling in favor of the church had struck a reasonable balance between the various interests at stake.Footnote 51 In Schüth v. Germany,Footnote 52 however, the ECtHR ruled against Germany. Schüth was an organist employed by a Catholic church, who had been dismissed for adultery. The German courts upheld the decision of the church, but the ECtHR found that those courts had not adequately considered Schüth's right to respect for his private life and his limited prospects for finding alternative work. In other words, “the applicant succeeded not because the outcome of the cases was unacceptable, but because of a failure by the German courts to engage with the arguments of the applicant”Footnote 53—a failure to take his rights and interests properly into account.Footnote 54

This kind of examination would of course be ruled out by the U.S. Supreme Court's interpretation of the ministerial exception. And there is cause for concern, because it is very easy to slip from judging whether some balance taking into account all relevant considerations was struck to judging whether an acceptable balance was struck—and thus making judgments about the reasonableness and weight of the reasons for the dismissal. In other words, while the distinction between SE(c)(i) and SE(c)(ii) is clear in principle, it might be difficult to maintain in practice. This is similar to the concerns that apply to examining whether the church has genuine religious reasons for its decision—it is easy for this to slip into directly judging the plausibility of those reasons. As Carolyn Evans and Anna Hood put it, “there is a real danger that the requirement of a religious organization to give reasons … will develop in time into a requirement that the organization give reasons that the courts consider sufficient or reasonable or just.”Footnote 55 The question then again becomes one of the extent to which this slide is inevitable, and whether it is nonetheless worth the risk for the sake of ensuring that churches cannot completely overlook the interests of their employees, or whether the risk of increasing infringements upon legitimate exercises of religious group autonomy should lead us to rule SE(c)(i) out from the start. The recent jurisprudence of the ECtHR suggests that such a slide is not inevitable. The Court has engaged in SE(c)(i) while holding that member states (and thus religious groups within them) have a wide margin of appreciation, such that the Court will not evaluate whether the balance struck was all-things-considered justified—thus avoiding SE(c)(ii). But it is too soon to tell whether this will remain true in the long run.Footnote 56 I would therefore again suggest that courts should in general undertake SE(c)(i), but should refrain from doing so in cases involving ministers proper, in order to avoid any slippage into SE(c)(ii) in those cases, where the need for protection for religious group autonomy is most acute.

The upshot of the arguments in this section can be seen in the table overleaf.

IV. PROCEDURAL EXAMINATION

I have now considered each of the kinds of substantive examination, and endorsed SE(a), SE(c)(i), and a minimal form of SE(b)(i)—at least for employees who are not ministers sensu stricto—while ruling out SE(b)(ii) and SE(c)(ii). What about procedural examination? As a reminder, procedural examination type PE(a) involves the court examining whether the church had followed its own employment procedures, while type PE(b) involves the court examining whether the church's procedures satisfy independent standard of procedural fairness. Again, the justification for both kinds is that churches must make their decisions in a fair way, rather than dismissing employees arbitrarily. And again, there are possible concerns with regard to both types of examination—but rather different concerns apply to each.

With regard to PE(a), the concerns revolve around the issue of entanglement and respect for competence interests. Assessing whether the church has followed its own procedures will obviously require interpreting what those procedures are, and this might well involve theological adjudication. This is especially the case for PE(a)(ii), where the court asks whether the church took into account the kinds of considerations laid out in relevant contracts and policy documents. These considerations will invariably appeal to religious ideas and doctrines, or to concepts like being a member of the church in good standing or complying with the church's teaching. Assessing whether the church based its decision on such considerations inevitably involves examining theological questions that are beyond the court's competence, such as whether the employee has exhibited ‘moral failure’.

Table 2. Account of Permissible and Impermissible Forms of Substantive Examination.

It is less clear that this worry applies to PE(a)(i), however, where the court focuses on whether the church has followed the formal structure of decision making laid out in its employment documents. For example, if the church has committed itself to giving verbal and written warnings before dismissal, or to allowing employees to present their defense within particular formalized hearings, then it seems that courts can examine compliance with these procedural requirements without risks of entanglement. There is nothing distinctively theological about a commitment to issue employees with written warnings prior to dismissal, and it does not seem that concerns with religious autonomy should prevent an employee who is dismissed without warning from demanding redress. This suggests that procedural examination of this kind should be permitted as long as it remains purely factual, but courts should step back at the point when it requires adjudication of the meaning of disputed theological ideas.

Even PE(a)(i) was explicitly ruled out by the U.S. Supreme Court in Hosanna-Tabor. Its judgment stated that courts should not inquire into whether churches have followed their own procedures, because this would mean resolving quintessentially religious controversies.Footnote 57 But it is not clear why this must be the case, since it is not clear that all the elements of churches’ procedures have much to do with quintessentially religious controversies. The Supreme Court's justification for its blanket restraint here thus seems unpersuasive.

This is not to say that there was nothing to the Supreme Court's view, however. In more complex cases, determining whether a church followed its own procedures even in the sense specified by PE(a)(i) might necessitate a detailed examination of, and adjudication between, competing interpretations of ecclesiastical law, which might be shaped by theological disagreements. This does raise non-entanglement concerns, especially when the challenged decision has been made by what all parties recognize as the highest tribunal of a hierarchical institution.Footnote 58 This gives a pro tanto reason to defer to those authorities and their interpretations, which should be overridden only by strong evidence of procedural infractions.Footnote 59 In other words, employees should be protected from clear violations of churches’ stated procedures, and this will unavoidably involve some interpretation of those procedures. But, wherever possible, courts should steer clear of interpretative disputes, and so should not overturn decisions that were based on reasonable interpretations.

Christopher Lund raises a different concern regarding procedural examination, regarding legal intent. In many cases involving church employment, he argues, “there is insufficient reason to think the parties intended or expected the contract to give rise to legally enforceable rights.”Footnote 60 Many of the claims brought by employees involve appeals to oral reassurances or church documents that are not intended as legally binding promises. This problem of legal intent is also pertinent in the UK context, where Church of England clergy have traditionally been seen not as “employees” at all, but as “office-holders,” such that ordinary employment law does not apply. The same approach was often applied to ministers from other denominations. But this has changed in recent years, and courts now examine the specific facts in order to determine whether there was legal intent to create an ordinary employment relationship.Footnote 61

These questions of legal intent are important, and courts should be alert to them. But they do not rule out an examination of whether churches have followed their own procedures once legal intent has been found. Again, such examination seems permissible as long as it involves a kind of factual examination that avoids engaging in theological adjudication. This permits PE(a)(i), but rules out PE(a)(ii), since the latter will invariably involve interpreting theological standards.

One might object that the theological adjudication in PE(a)(ii) is no different to that involved in SE(b)(i), which I have endorsed. Determining whether a church had good reasons for its decision based on its own beliefs might seem to involve just as much theological adjudication as determining whether the church applied its stated standards and grounds in making that decision. This would be mistaken, however. The minimal form of SE(b)(i) that I endorse simply requires showing that a religious belief justifies the decision, rather than having to point to specific clauses within employment documents or to offer a detailed interpretation of the theological content of those clauses. PE(a)(ii) would require the court to establish whether the employee has really displayed a form of “moral failure” that the church can rightly hold to have triggered the relevant clause in her contract. Deciding whether such a standard has been met must involve a full, irreducibly theological, evaluation. Whereas SE(b)(i) simply requires the church to show that they have a sincere belief that the employee's conduct has fallen short.Footnote 62

Procedural examination type (b) involves courts evaluating the procedures followed by the church against independent standards of procedural fairness, such as standards of evidence, transparency, rights to reply, and so on. This aims to protect employees from arbitrary or unreasoned decisions, or from being dismissed without fair warning or a chance to respond to accusations leveled against them. The ECtHR has explicitly engaged in this kind of evaluation,Footnote 63 most clearly in the case of Lombardi Vallauri v. Italy, which concerned a professor at a Catholic university whose contract was terminated after it had been regularly renewed for twenty years. The reason for the non-renewal was that he no longer had the approval of the Congregation for Catholic Education, a required condition for the post, because they deemed him to have views “in clear opposition to Catholic doctrine.”Footnote 64 The ECtHR found a violation of Lombardi Vallauri's rights to free expression and to a fair trial,Footnote 65 on the basis that he had not been provided with an adequate explanation of the reasons for his contract not being renewed and had been given no opportunity to answer the charges against him. As Leigh puts it, “while recognition of religious autonomy could justify the university's refusal to employ someone who in its view did not conform to its religious ethos, this could not extend to a point blank refusal to explain the basis for that conclusion.”Footnote 66 In the eyes of the ECtHR, “religious autonomy therefore is not breached if the secular courts require some compliance with basic fair process requirements.”Footnote 67

The independence of the standards that the court draws upon here means that concerns about courts’ inability to interpret religious doctrines seem not to apply. But concerns about freedom of religion might well still apply, because the court could impose procedural standards that the church does not endorse, or that conflict with its doctrines.Footnote 68 This gives reason to ensure that the procedural standards imposed by courts are minimal. Churches can rightly be required to have some formalized structures where employees are given warnings, have a chance to respond to accusations, and are given reasons for decisions. But we should not impose strict standards of the kind we would expect the state to meet in its decision making.Footnote 69

This is particularly important because it prevents this procedural judgment from slipping into a substantive judgment of the veracity of the reasons on which the church based its decision. For example, consider the question of whether a church had adequate evidence for its decision. Are the complaints of a few well-regarded congregants adequate evidence of ill-temper and avarice that renders a minister unfit for office? This might itself depend upon the church's own view of what constitutes sufficient evidence in this context, based on its views about the levels of purity, and lack of suspicion of impurity, that must be exhibited by religious leaders. Similarly, with regard to fair hearing, whether the employee should have realized that a particular meeting was their final chance to state their defense, despite this not being explicitly stated, might depend upon contextual expectations that are shaped by the group's practices. If the court applied high standards of procedural fairness in these cases then it would in effect be making substantive judgments about the doctrines and practices of the church that led to their decision, thus infringing its coherence interests. This can generally be avoided if the requirements of fair procedure are sufficiently minimal. Of course, more minimal standards here means less protection for the employee, so this does not come without cost. Nonetheless, the correct balance between the competing values in this context would permit courts to impose minimal independent standards of procedural fairness upon churches, thus ruling out egregious cases of procedural unfairness without violating religious group autonomy.

Even minimal standards of procedural fairness might sometimes conflict with churches’ beliefs, however. Evans and Hood give the example of action taken by a Catholic church against an employee on the basis of information that was given during confession.Footnote 70 Requiring the church to explain its reasons in this case would violate its beliefs about the importance of secrecy in this context. There are two possible responses to this. First, one might allow for exceptions to the courts’ requirements of procedural fairness if the church can make a plausible argument for why they should not be applied in this case. So the church might explain why secrecy is necessary on this occasion, and the court might permit an exception on this basis. Evans and Hood note that the ECtHR hinted at this in its Lombardi Vallauri ruling.Footnote 71 Given that such exceptions are likely to be rare, since churches will not often have a commitment to violating basic standards of procedural fairness, this seems reasonable—especially in the light of the fact that congregants will likely be aware that these are features of the churches’ decision-making practices. Second, however, one might argue that precisely because it is basic standards of procedural fairness that are being applied, no such exceptions should be permitted. There are various basic rights that we do not allow churches to violate, and the rights of employees to decisions that meet these procedural standards might be in this category. The plausibility of this argument obviously depends upon how minimal those standards are. If they really are minimal enough then it might seem correct. A full consideration of these issues would require a detailed account of the procedural standards being applied and the kinds of cases where churches might claim coherence-interest-based reasons for violating them. I lack space for this here. Nonetheless, I would tend toward holding that exceptions are sometimes possible if the church can provide a plausible religious justification for them. Of course, this means that courts will have to adjudicate the plausibility of certain religious reasons, bringing back worries about entanglement. However, I think this is unavoidable within this narrow context, and that the relevant cases will be rare enough not to warrant major concern. Overall, then, I think we should endorse a minimal form of PE(a), while recognizing that exceptions might sometimes be permitted.

In sum, I have endorsed procedural examination type PE(a)(i) and a minimal version of PE(b), but rejected PE(a)(ii). In the previous section, I argued that even the forms of substantive examination that I endorsed should be avoided in cases involving ministers sensu stricto,Footnote 72 in order to ensure protection for the very core of religious group autonomy. Does the same apply for procedural examination? On the one hand, one might hold that even for ministers proper, protection from basic procedural unfairness is important. Churches should not be able to dismiss ministers with complete impunity or in ways that plainly contravene even their own procedural rules. One might thus hold that procedural, but not substantive, examination is permissible in cases involving such employees. On the other hand, concerns about slipping into forms of theological adjudication that violate churches’ competence interests, taking sides in internal interpretative disputes, and imposing independent standards in a way that undermines churches’ coherence interests, are again most acute for this category of employees. This might lead one to rule out even procedural examination, to ensure that the most central exercises of religious group autonomy are firmly protected. In my view, this is a close call. But I would tentatively lean in the latter direction, at least for the kinds of cases of dismissal under consideration here, and thus would only apply the framework that I have defended to cases that do not involve ministers sensu stricto.Footnote 73 It is important to emphasize, however, that many of the cases that courts consider are of this kind, so this is not a severe limitation in the framework's scope of application.Footnote 74

V. APPLICATIONS

I have now considered all of the kinds of judicial examination identified in my taxonomy. The table overleaf summarizes the account of legitimate examination, for employees who are not ministers sensu stricto, that emerges from my analysis.

Clearly, this account is fairly complicated. It also brings risks—given the fine distinctions involved, courts could easily slip from permissible into impermissible forms of examination, thus objectionably limiting religious freedom and violating competence interests. One might argue that the advantage of the U.S.-style ministerial exception is that it avoids this complexity and prevents this slippage. This would be misleading, however, because the exception also involves complexity, at the point of determining who counts as a “ministerial employee” in the relevant sense (which, importantly, is wider than ministers sensu stricto). The application of the exception requires the establishment of tests regarding who is a ministerial employee, and controversial judgment calls are unavoidable in applying those tests. Further, even if we find that an employee is not ministerial, this should not mean that we remove all protection for religious group autonomy. Certain kinds of protections from judicial examination should apply even for non-ministerial appointments since coherence interests and competence interests can still be at stake. Matters of theological adjudication and religious reasoning can be involved in decisions involving such employees. My approach provides for this, whereas the ministerial exception, ironically, might underprotect religious groups in these cases.

One way to avoid this underprotection is to define the category of “ministerial employee” within the ministerial exception widely. Indeed, U.S. courts use a fairly wide definition. This leads to the more pressing problem with the doctrine, however: overprotection of religious organizations in some cases, due to completely excluding all forms of judicial examination once an employee has been found to be ministerial. A recent Alabama District Court judgment illustrates this point. Maria Nolen, the former principal of a Catholic grammar school, claimed that she had been discharged in retaliation for her attempts to stop practices of discrimination against Hispanic students.Footnote 75 The school argued that Nolen had in fact been dismissed for embezzlement—and it was undisputed that she had written checks to herself after being instructed not to do so and claimed excessive reimbursement for travel expenses. It had also transpired that Nolen was not actually properly certified to serve as a head teacher in Alabama. This appears to be a case where the court should examine the facts in order to determine whether Nolen's claim of wrongful dismissal is sustainable. The putative reasons for her dismissal—embezzlement and lack of qualifications—are not distinctively “religious.” And dismissal for protesting discrimination against Hispanic students would be wrongful in this case, given that such discrimination has no relation to the Catholic Church's beliefs or doctrines, so this would not be a legitimate reason for dismissal even by their own lights. Examining this case need not involve evaluating religious questions. However, the court dismissed the case, on the basis that it was covered by the ministerial exception. I think the court was right that Nolen's role was ministerial in the sense relevant to the U.S. ministerial exception doctrine. She was an official representative of the Church in the community, and saw herself as such, and her role centrally involved promoting Christian values and advancing the school's religious mission. But these facts should not preclude the court examining the merits of her claims, given the nature of the case. My approach enables this.

Table 3. Account of Permissible and Impermissible Forms of Judicial Examination.

Of course, my approach does involve more complexity than the ministerial exception, and this comes with costs. But this is a good thing, to the extent that it leads to better decisions. Further, as I noted above, the recent jurisprudence of the ECtHR suggests that courts are able to make the necessary judgments and reach justifiable decisions. For example, take the case of Obst v. Germany.Footnote 76 Michael Obst was the Mormon Church's European director for public affairs. He was dismissed when it was discovered that he was having an extramarital affair—a serious sin within the church. He brought a claim against his dismissal under ECHR Article 8, which protects the right to respect for private life. This claim was dismissed by the German Federal Labor Court, but Obst appealed to the ECtHR.Footnote 77

How would my approach apply here? First, the court can check that the church has followed its own employment procedures, in terms of the specified formal structure of its decision making (PE(a)(i)). It can also check that this procedure satisfies minimal independent standards of procedural fairness (PE(b)). Obst's affair had become known through his own admission of it, so there were no concerns about evidence here.Footnote 78 However, Obst was dismissed immediately, prior to an internal disciplinary procedure that led to his excommunication. This does raise a concern regarding procedural fairness, which the Federal Labor Court considered. It concluded that dismissal without warning was permissible in this specific case given the severity of the breach of the church's teaching.Footnote 79 The German Civil Code permitted such dismissal in certain cases,Footnote 80 and Obst's contract explicitly stated that it could follow severe violations of the principles of the church.Footnote 81 In this way, the Court both applied some minimal independent standards of procedural fairness, and checked that the dismissal satisfied the church's own specified decision-making process. The ECtHR affirmed these judgments as reasonable.Footnote 82

Second, the court can consider the pretext question (SE(a)). There seems to be no question of pretext in this case. It is clear that the church expected its employees to refrain from adultery. Indeed, Obst's contract stated that employees of his level of seniority must be members of the church in good standing,Footnote 83 and the ECtHR explicitly noted that he was aware that this implied a requirement not to commit adultery, given the clear teachings of the church.Footnote 84 Obst had a high profile role representing the church and knew that he was expected to keep its teaching. These considerations also cover the minimal kind of evaluation of the reasons for the decision that I consider permissible (SE(b)(i)). The ECtHR emphasized that this did not mean that all religious employers could permissibly dismiss employees for adultery, but the Mormon Church had shown the seriousness of adultery in its eyes, and it was not up to the Court to question that.Footnote 85

Third, we face the balancing question. Here, the ECtHR checked that the German Court had engaged in some kind of balancing in making their decision—taking into account Obst's right to privacy (SE(c)(i)).Footnote 86 But it granted a margin of appreciation with regard to the substantive outcome: it did not seek to establish if this was the right balance, and noted that Obst could not complain simply because the weighting is not the one he would prefer.Footnote 87 It thus rightly refrained from examination type SE(c)(ii).

Rulings like that in Obst suggest that courts can apply my kind of framework—and indeed that some perhaps already implicitly use a framework not dissimilar to mine. Nonetheless, we should be attentive to the risks of courts slipping into impermissible forms of examination. This gives reason to hedge on the side of further limiting courts’ examinations in core cases of churches’ decisions regarding ministers sensu stricto, in order to ensure adequate protection for religious group autonomy. As I have argued, this might justify something closer to a U.S.-style ministerial exception for this narrow range of cases.Footnote 88 Beyond such cases, however, I think courts should endeavor to apply the framework I have sketched.Footnote 89 This framework takes seriously both the normative concerns underlying claims to religious group autonomy and the need to protect employees against arbitrary and unjust treatment. In this way, it might be able to provide some reconciliation between the strident defenders and critics of church autonomy.