Courage is known as one of the most universally admired virtues (Peterson & Seligman, Reference Peterson and Seligman2004). The notion of courage can be traced to early historical, philosophical, and religious writings (e.g., Augustin, 1887; Plato, 1961). Plato perceived courage as one of the four core virtues (Dahlsgaard, Peterson, & Seligman, Reference Dahlsgaard, Peterson and Seligman2005). For Aristotle, courage was ‘inseparable from the human capacity for the deliberation and choice required for moral responsibility’ (Ward, Reference Ward2001: 71). More recently, courage has been recognized as pivotal to workplace-related outcomes, such as creativity (May, Reference May, Luth and Schwoerer1975), and has been claimed to be ‘at the heart of leadership’ (Staub, Reference Staub1996: 191). Courageous action was also seen as an ‘indispensable, recuperative mechanism for regenerating organizations’ (Hornstein, Reference Hornstein1986: 15). However, despite the wide recognition that courage has received in the literature, the scientific discourse on courage in organizations has only begun to emerge (Pury & Lopez, Reference Pury and Lopez2010; Harbour & Kisfalvi, Reference Harbour and Kisfalvi2014; Detert & Bruno, Reference Detert and Bruno2017).

Schilpzand, Hekman, and Mitchell (Reference Schilpzand, Hekman and Mitchell2014) observed that there are two main streams in the contemporary discourse on courage: (a) literature in which courage is seen as a character strength, virtue, or disposition (e.g., Peterson & Seligman, Reference Peterson and Seligman2004; Chun, Reference Chun2005; Peterson & Park, Reference Peterson and Park2006); and (b) literature that discusses courage as a behavioral response (action) to events occurring in various social settings (e.g., Rate & Sternberg, Reference Rate and Sternberg2007). While the first view appears to be the dominant paradigm present in the literature across various fields (see Harbour & Kisfalvi, Reference Harbour and Kisfalvi2014), the second perspective is gaining increased attention in organizational research (e.g., Schilpzand, Hekman, & Mitchell, Reference Schilpzand, Hekman and Mitchell2014; Palanski, Cullen, Gentry, & Nichols, Reference Palanski, Cullen, Gentry and Nichols2015). Broadly defined, the latter perspective implies that ‘courage is more appropriately expressed in terms of the “act” rather than the “actor” (i.e., defining courage in terms of behavior rather than in terms of personality or character traits)’ (Rate & Sternberg, Reference Rate and Sternberg2007: 6).

This study aims to contribute to the second stream of research. Specifically, the purpose of the study is to advance our understanding of the relationship between behavioral courage and job performance, and also to explore the possible effects of organizational level and gender on such a relationship. While recent empirical research has underscored the importance of courageous actions as an important constituent of leadership effectiveness (O’Connell, Reference O’Connell2009), as well as executive performance and executive image (Palanski et al., Reference Palanski, Cullen, Gentry and Nichols2015), theoretical conceptualizations of the relationship between courage in the workplace and job performance across various levels of organizations have not received adequate empirical attention. Further, the effects of organizational level and gender on the potential relationship between behavioral courage in the workplace and job performance still remain underexplored (e.g., Kaiser & Craig, Reference Kaiser and Craig2011; Zenger & Folkman, Reference Zenger and Folkman2012; Palanski et al., Reference Palanski, Cullen, Gentry and Nichols2015). Thus, the questions guiding this study are as follows:

-

1. What is the nature of the relationship between behavioral courage and managerial job performance?

-

2. What are the effects of organizational level on the relationship between behavioral courage and managerial job performance?

-

3. What are the effects of gender on the relationship between behavioral courage and managerial job performance?

Behavioral courage examined in the present study was operationalized using a multisource feedback instrument that measures behavioral competencies considered important to managerial effectiveness. Prior research has employed managerial competencies and behaviors to assess virtues and character strengths (e.g., Grahek, Thompson, & Toliver, Reference Grahek, Thompson and Toliver2010; Sosik, Gentry, & Chun, Reference Sosik, Gentry and Chun2012), and to conceive behavioral courage (Palanski et al., Reference Palanski, Cullen, Gentry and Nichols2015). As self-reporting of courage may not be adequate in assessing the construct (Worline, Reference Worline2004; Harbour & Kisfalvi, Reference Harbour and Kisfalvi2014), to measure behavioral courage we employed direct supervisors’ ratings of the behaviors of managers being profiled. In addition, as studies on courage in organizations underscore the importance of social (organizational) and historical contexts in defining courage (e.g., Worline, Reference Worline2012), we purposefully limited the data to mid- to large-sized for-profit organizations in the United States, gathered during the period from 2010 to 2015.

In the following section, we provide theoretical grounding and develop our hypotheses. We then describe the method and present our results. What follows is our discussion in which we outline theoretical and practical implications. Finally, we present the limitations of the study and also highlight areas for future research.

THEORETICAL GROUNDING AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

Woodard and Pury noted that ‘various definitions, as well as controversy regarding the various types of courage’ have often been attributed to the fact that ‘research on courage is remarkably limited’ (Reference Woodard and Pury2007: 135). The authors empirically conceived the following four-factor structure of courage: (a) work/employment courage; (b) patriotic, religion, or belief-based physical courage; (c) social-moral courage; and (d) independent courage, or alternatively, family-based courage. Woodard and Pury’s (Reference Woodard and Pury2007) findings were central to this inquiry as they support the argument that, as a social construct, courage needs to be understood through the lens of a particular human activity. Thus, what can be seen as courage at work may differ from what is seen as courage on a battlefield. Likewise, courage in the workplace decades ago may not be seen as such in the contemporary workplace.

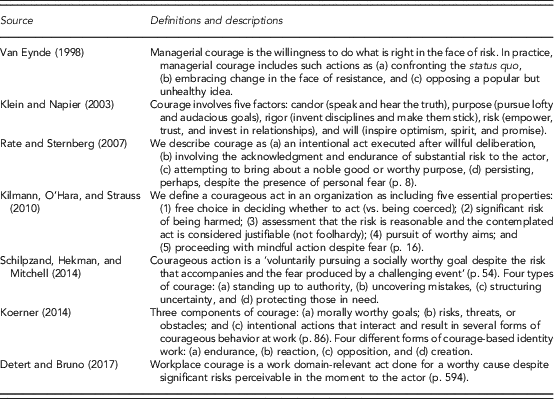

As the study’s focus is on behavioral courage in the workplace, what follows is a review of the literature that has explored courage in the organizational context. Table 1 provides selected definitions of courage and descriptions of acts of courage in the organizational context.

Table 1 Selected definitions and descriptions of acts of courage in the organizational context

While the investigation of courage in the workplace is still emergent, several recent studies have provided useful insight on the construct and its manifestation. For instance, previous research often conceptualized courage as overcoming adversity or challenges in the face of fear (Rachman, Reference Rachman1990). In turn, Rate, Clarke, Lindsay, and Sternberg (Reference Rate, Clarke, Lindsay and Sternberg2007: 95) empirically found that ‘fear may not be a necessary component’ of courage. At the same time, three other components the authors considered in their analysis (intentionality/deliberation, noble/good act, and known personal risk) found empirical support. More recently, Schilpzand, Hekman, and Mitchell (Reference Schilpzand, Hekman and Mitchell2014) challenged the conventional wisdom of courage as being attributed only to a person’s disposition. The authors found that both the determination of one’s degree of personal responsibility in responding to a challenging situation and the potential social costs involved in acting are important constituents of workplace courage. Grounding their work in 94 interviews, the authors conceived courageous actions around the following four themes: (a) standing up to authority, (b) uncovering mistakes, (c) structuring uncertainty, and (d) protecting those in need. Similarly, Koerner (Reference Koerner2014) observed that previous conceptualizations of workplace courage often focused on oppositional forms of courage, in which actors confront powerful others to remedy a problematic situation. The author noted that a broader range of courage forms might exist in the workplace. Specifically, about 30% of the courageous acts examined in the study did not include such oppositional forms.

Courage in the workplace and job performance

Research on courage in the workplace provides empirical evidence of the positive effects of courage on various organizational outcomes. In a survey of 2,548 respondents from seven British firms, Chun (Reference Chun2005) observed that courage, as a virtue factor, was positively associated with overall satisfaction. In their study of the relative importance of character traits for leader performance in upper echelons, Sosik, Gentry, and Chun (Reference Sosik, Gentry and Chun2012) found that behavioral manifestations of courage (which the authors operationalized as bravery) was an important virtuous predictor for top executive performance. More recently, Palanski et al. (Reference Palanski, Cullen, Gentry and Nichols2015) highlighted the role of behavioral courage as an important mediator in the relationships between integrity and executive performance, as well as between integrity and executive image. Therefore, we expect that managers with higher ratings on behavioral courage will more likely receive higher job performance ratings from their supervisors than those with lower scores. Our expectation is consistent with prior empirical research that has linked courage with various positive organizational outcomes. Thus, we predicted that:

Hypothesis 1: Behavioral courage displayed by managers in the workplace will be positively related to job performance.

Behavioral courage and organizational hierarchy

The nature and complexity of work varies substantially across the organizational hierarchy (Jacobs & Lewis, Reference Jacobs and Lewis1992). A wide range of theories as well as empirical evidence suggest that some behaviors and skills gain more importance than others as individuals move up the organizational ladder (e.g., Mumford, Campion, & Morgeson, Reference Mumford, Campion and Morgeson2007; Dai, Yii Tang, & De Meuse, Reference Dai, Yii Tang and De Meuse2011). The moderating effect of organizational level on the relationship between various important behavioral variables has been reported in a number of management studies (e.g., Kim, Murrmann, & Lee, Reference Kim, Murrmann and Lee2009). Specifically, Kaiser and Craig (Reference Kaiser and Craig2011) explored the moderating role of organizational level on the relationship between seven dimensions of managerial behavior and overall leadership effectiveness, and found that behaviors associated with effectiveness differed across levels.

While courage is often discussed as an important attribute of both leaders and followers (e.g., Chaleff, Reference Chaleff1995; Baker, Reference Baker2007), recent empirical studies have explored the relationship between courage and executive performance. In particular, our literature review suggests that recent empirical studies have largely focused on exploring the importance of courage for top executive performance (Sosik, Gentry, & Chun, Reference Sosik, Gentry and Chun2012; Palanski et al., Reference Palanski, Cullen, Gentry and Nichols2015). Given the expectation of courage among the upper echelons of management, we expected there would be significant differences in the relationship between behavioral courage and job performance, based on the employee’s position in the organizational hierarchy. In particular, we proposed that:

Hypothesis 2: The positive relationship between behavioral courage and job performance will be moderated by organizational level. Specifically, the relationship between behavioral courage and job performance will be stronger when the manager is at a higher level in the organization.

Behavioral courage and gender

The importance of gender as a variable of interest in management and leadership research has grown as women have gained more access to managerial and leadership positions. There is vast literature that has explored the differences between female and male genders in various professional and national contexts (e.g., Karatepe, Yavas, Babakus, & Avci, Reference Karatepe, Yavas, Babakus and Avci2006; Kim, Murrmann, & Lee, Reference Kim, Murrmann and Lee2009). Various empirical studies, including meta-analyses, have reported the moderating effect of gender on a number of organizational outcomes (e.g., Avolio, Mhatre, Norman, & Lester, Reference Avolio, Mhatre, Norman and Lester2009; Kim, Murrmann, & Lee, Reference Kim, Murrmann and Lee2009; Wang, Chiang, Tsai, Lin, & Cheng, Reference Wang, Chiang, Tsai, Lin and Cheng2013). In particular, Eagly, Johannesen-Schmidt, and Van Engen (Reference Eagly, Johannesen-Schmidt and Van Engen2003) found that women were more likely to be identified as transformational leaders than men. In turn, Avolio et al. (Reference Avolio, Mhatre, Norman and Lester2009) explored the moderating effect of gender on the impact of leadership interventions. The authors reported a significant difference in the effect sizes for leadership interventions implemented for all-female and majority-female participants versus all-male and majority-male participant studies.

While the extant literature on differences between males and females has broadened our understanding on the role of gender in the workplace, the findings from empirical research on the role of gender were not conclusive, and in some cases warranted further investigation (Avolio et al., Reference Avolio, Mhatre, Norman and Lester2009). For instance, while past research suggested that women tended to be rated more critically than men (e.g., Eagly & Carli, Reference Eagly and Carli2003), a recent study by Zenger and Folkman (Reference Zenger and Folkman2012) found that women were rated as better leaders than their male counterparts, with their results being consistent at every level as rated by their peers, bosses, and direct reports.

As women tend to be considered as more communal and selfless than men (Bono et al., Reference Bono, Braddy, Liu, Gilbert, Fleenor, Quast and Center2017; Eagly & Carli, Reference Eagly and Carli2003) – characteristics that seem to be closely associated with the ‘common good’ aspect of behavioral courage – it is quite possible that behavior patterns of female managers may be perceived as more courageous in business environments. In addition, as our data were collected in the United States, and in the ‘contemporary culture of the United States, women … are lauded as having the right combination of skills for leadership, yielding superior leadership styles and outstanding effectiveness’ (Eagly, Reference Eagly2007: 1), we proposed that:

Hypothesis 3: The positive relationship between behavioral courage and job performance will be moderated by gender. Specifically, the effect of behavioral courage will be stronger when the manager is female.

METHODS

Participants

The data for the present study were obtained from an archival database of multisource feedback on managers in a variety of organizations. Specifically, ratings on nonexpatriate managers were collected from mid- to large-sized for-profit organizations in the United States from 2010 to 2015. The sample in this study consisted of a total of 6,009 managers (M age=42.8, SD=8.1), with 52.9% male. Among the participants, about 80.7% were White, 7.5% Asian, 5.7% Black, 4.2% Hispanic, and 1.8% Other. About 16.9% of participants had a high school degree, 49.9% held a baccalaureate degree, and 33.2% attended graduate school. As to the organizational levels, 48.6% were at the low level, 33.8% were at the middle level, and 16.3% were at the top level.

Measurement

Behavioral courage

The scale for behavioral courage was created employing items drawn from a multisource feedback instrument, The PROFILOR ® for Managers (PDI Ninth House, 2004). As the original 135-item instrument was developed without specific consideration of this construct, we followed the principles of Q-methodology (Stephenson, Reference Stephenson1953) to create our scale. First, building on our extensive review of the literature on courage (e.g., courageous leadership, workplace courage, etc.), the authors selected 30 items drawing from The PROFILOR ® for Managers (PDI Ninth House, 2004). Next, two subject matter experts, with advanced degrees and field experience in management and human resource development were asked to individually assess the 30 items and select those that represented behavioral manifestations of courage in the workplace. The subjective judgment of the subject matter experts was necessary to ensure face validity of the construct. Building on the results obtained from the subject matter experts, the panel of authors unanimously agreed upon six items as representative of behavioral courage in the workplace, to be employed in the study:

-

1. Takes a stand and resolves important issues.

-

2. Makes decisions in the face of uncertainty.

-

3. Challenges others to make tough choices.

-

4. Drives hard on the right issues.

-

5. Influences and shapes the decisions of upper management.

-

6. Champions new initiatives within and beyond the scope of own job.

As recent studies underscore that it is through ‘the eye of the beholder’ that actions can be interpreted as courageous or not (Harbour & Kisfalvi, Reference Harbour and Kisfalvi2014), we employed direct supervisor ratings of the six behaviors in our analysis. The ratings were recorded using a 5-point scale (1=‘Not at all,’ to 5=‘To a very great extent’). The six items yielded an internal consistency of 0.87. The use of supervisors’ ratings was intentional; it implied that the six behaviors that the managers were assessed upon were directed towards some organizational goals, as opposed to the manager acting in self-interest. Consistent with studies that employed a similar approach (e.g., Sosik, Gentry, & Chun, Reference Sosik, Gentry and Chun2012), confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to test whether the items are well related to this latent construct. The fit indices of confirmatory factor analysis indicated that this one-factor model fit the data (χ2=141.89, p<.001, normed fit index=0.99, comparative fit index=0.99, goodness-of-fit index=0.99, and root mean square error of approximation=0.04). Factor loadings ranged from 0.48 to 0.56.

Job performance

This outcome variable was measured using an existing 5-item scale from The PROFILOR ® for Managers (PDI Ninth House, 2004). The scale had been developed and validated by the original developers of The PROFILOR ® for Managers (PDI Ninth House, 2004, 2006). All items were measured on a 1–5 scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree.’ The scale had an internal consistency of 0.88 (PDI Ninth House, 2006). Items included:

-

1. Accomplishes a great deal.

-

2. Gets the job done.

-

3. Gets work done on time.

-

4. Produces high-quality work.

-

5. Is an effective manager overall.

Moderating variables: organizational level and gender

The five employee levels (1=Supervisor of hourly and clerical, 2=First-line management, 3=Middle management, 4=Executive management, 5=Top management) were dummy coded into three variables: low level (1 and 2 combined, as the reference group), middle level (3), and top level (4 and 5 combined). Gender was coded as follows: 0=female, 1=male.

Covariates

We controlled for race (white as the reference group), as whites may receive higher ratings than non-whites (e.g., McKay & McDaniel, Reference McKay and McDaniel2006). We also controlled for the human capital measures of education (1=Some secondary/high school, 2=Secondary/high school, 3=Undergraduate degree, 4=Postgraduate degree, 5=Doctorate/professional), as the variable may affect performance outcomes (e.g., Ng & Feldman, Reference Ng and Feldman2010). Educational level was dummy recoded into three variables: High school (1 and 2 combined), which was used as the reference group; Undergraduate degree (3); and Postgraduate (4 and 5 combined). Finally, we controlled for age as previous studies indicated that older employees may be rated lower on performance appraisals (Lawrence, Reference Lawrence1988).

RESULTS

The preliminary analyses showed a high correlation between the two scales, behavioral courage (6-item scale) and job performance (5-item scale) (r=0.72, p<.001), which may have caused a multicollinearity problem for the regression analysis performed later. Thus, we ran a principle component analysis with varimax rotation to examine the orthogonality of these two constructs. The results showed that two main factors (eigenvalue>1) explained 61.3% variance. After a further look at each constituent item, we found that one item in each scale had large factor loadings on both factors. To reduce the redundancy between the factors, we decided to remove the following items: ‘Drives hard on the right issues’ in the behavioral courage scale and ‘Is an effective manager overall’ in the job performance scale. The refined scale of behavioral courage had an internal consistency coefficient of 0.79 and 0.87 for the job performance scale. After these revisions, the correlation between behavioral courage (5-item scale) and job performance (4-item scale) was reduced to 0.63 (p<.001). The new mean for behavioral courage was 3.85 (SD=0.56) and job performance was 4.31 (SD=0.58).

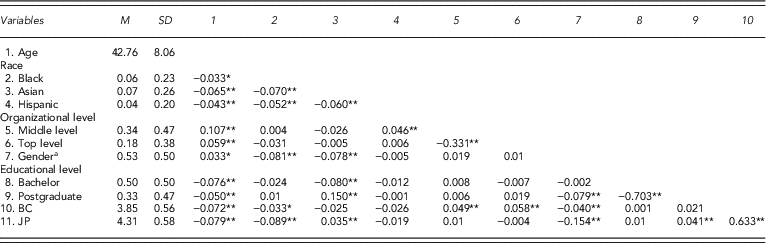

Table 2 includes means, standard deviations, and correlations among the variables used in this study.

Table 2 Means, standard deviations, and correlations among variables after revising scales

Note.

a 0=Female, 1=Male.

BC=behavioral courage; JP=job performance.

*p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001.

We also examined whether there were differences either among different organizational levels or by gender. The results from analysis of variance displayed significant differences in behavioral courage among the low, middle, and top hierarchical levels (F=13.80, p<.001). Follow-up posthoc analyses showed that the managers at the top level (M=3.91) had significantly higher behavioral courage scores than those at the low level (M=3.79; p<.001); Likewise, managers at the middle level (M=3.88) also showed higher behavioral courage than managers at the low level (p<.001). However, no statistically significant difference was discovered when comparing managers at the middle level and managers at the top level. At the same time, an independent-sample t-test showed that there was a small yet significant difference (0.05) in behavioral courage between male and female managers (t=2.95, p=.003), with males scoring slightly higher than females.

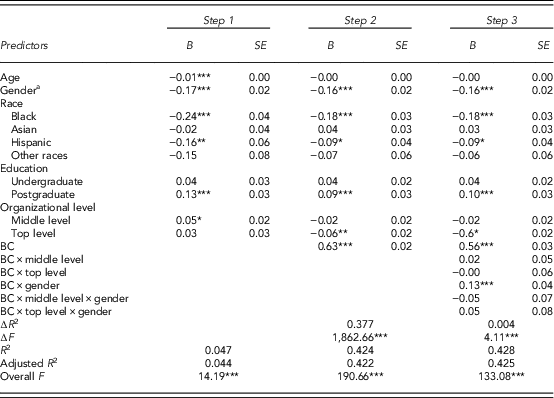

To test our hypotheses, we performed a hierarchical regression analysis. The results can be found in Table 3. The first model included control variables (age, race, and education) and dummy-coded independent variables (gender and organizational level); the second model added behavioral courage; the third model added (a) interactions between behavioral courage and organizational level, (b) interactions between behavioral courage and gender, and (c) three-way interactions among behavioral courage, organizational level, and gender.

Table 3 Regression results for behavioral courage, and the interaction between behavioral courage and organizational level as predictors of job performance

Note.

a 0=Female, 1=Male.

BC=behavioral courage; JP=job performance.

*p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001.

After entering our control variables and two moderator variables (Step 1), we observed that the entered variables did not have much effect on job performance. However, after adding behavioral courage into the model, we found that behavioral courage had a positive relationship with supervisor ratings of job performance and alone accounted for a substantial amount of variance in this outcome (b=0.63, p<.001; ΔR 2 =0.377, p<.001). Hence, Hypothesis 1, predicting that managers who demonstrate behavioral courage are likely to be perceived as better performers, was supported.

Interestingly, adding behavioral courage appeared to have a suppressor effect on this relationship. Specifically, in the first model (Step 1) managers who were at the middle level were rated higher on job performers than managers at low level management positions (b=−0.05, p=.025). However, after adding behavioral courage into the model, this effect disappeared, while top-level management became significant (b=−0.06, p=.009) (see Step 2 in Table 3). This suppressor effect may indicate that top-level management was substantially correlated with behavioral courage, which enhanced the effect of top-level management on job performance.

Hypotheses 2 and 3 predicted that organizational level and gender would moderate the relationship between behavioral courage and job performance. These hypotheses were tested in the last two models of the regression analysis (Step 3), in which we were looking for the interaction effects. To reduce multicollinearity, we centered behavioral courage (i.e., minus the grand mean). After testing for Hypothesis 2, we observed that although behavioral courage was found to be highly predictive of higher ratings on job performance (Step 2), behavioral courage appeared to have the same predictive value among the three organizational levels (see Step 3 in Table 3); hence Hypothesis 2 was not supported.

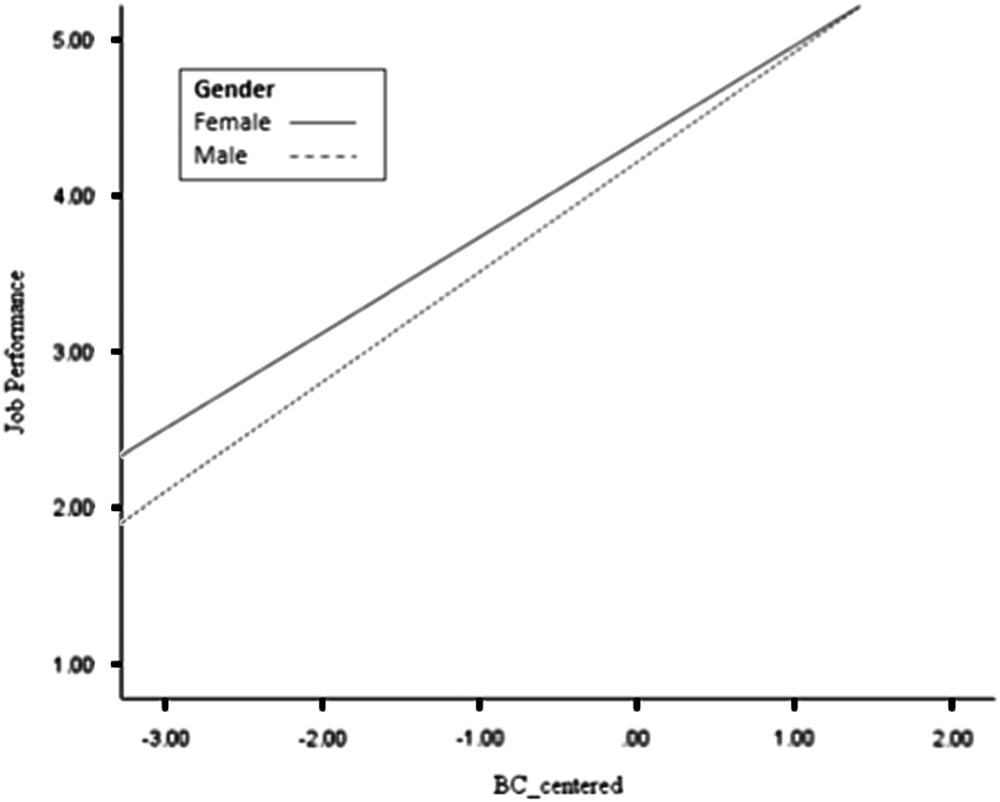

In turn, model 3 also showed a significant interaction effect between behavioral courage and gender (b=0.13, p=.001). This indicates that even though female managers overall had better performance than male managers, as observed in Step 1 (b=−0.17 p=.001), gender was found to be a moderating variable in the relationship between behavioral courage and job performance (see Figure 1). Specifically, when levels of behavioral courage were high, both genders were rated equally as high performers. However, when levels of behavioral courage were low, women were rated as better performers than men. Hence, Hypothesis 3 was supported. The three-way interaction (behavioral courage×organizational levels×gender) did not yield any statistically significant results.

Figure 1 Interaction effect between behavioral courage (BC) and gender.

DISCUSSION

Theoretical implications

We found that behavioral courage was positively associated with job performance. As the data collected included managers from a variety of mid- to large-sized for-profit organizations in the United States, the findings are likely to be generalizable to managers in other for-profit organizations. At the same time, we acknowledge that our findings should not be considered in isolation; rather, various other factors have been recognized as important predictors of job performance (e.g., Lim, Song, & Choi, Reference Lim, Song and Choi2012; Rana, Ardichvili, & Tkachenko, Reference Rana, Ardichvili and Tkachenko2014). To wit, behavioral courage needs to be understood as one of the important predictors associated with higher job performance. The study results also shed light on the supposed moderating effects of organizational level and gender in the relationship between behavioral courage and job performance, thus addressing the recognized need for studying potential moderators of workplace courage (Detert & Bruno, Reference Detert and Bruno2017). With the identified moderating effect of gender, the study results also contribute to the emerging discourse in courage scholarship that explores the role of gender in the workplace (Rankin & Eagly, Reference Rankin and Eagly2008). In particular, the study results support and also extend some propositions of the social role theory of sex differences and similarities (Eagly, Wood, & Diekman, Reference Eagly, Wood and Diekman2000).

Our results suggest that behavioral courage is likely to be beneficial to an organization irrespective of the manager’s position in the organizational hierarchy. This important finding somewhat echoes Kilmann, O’Hara, and Strauss (Reference Kilmann, O’Hara and Strauss2010) inquiry in which the authors attempted to conceive courage at different levels of the organization. In particular, the authors found that employees who experienced less fear and observed more acts of courage perceived their organization as better than its competitors in overall performance, customer satisfaction, and potential for long-term success. Our study supports Kilmann, O’Hara, and Strauss (Reference Kilmann, O’Hara and Strauss2010) in the sense that acts of courage in the workplace appear to be positively associated with important organizational outcomes. It is possible that, if mean scores on behavioral courage are compared across organizations, some organizations are likely to score higher on courageous behavior than others. To reiterate, with a sample of managers from mid- to large-sized for-profit organizations in the United States, we found that there was a positive, causal relationship between behavioral courage and job performance, and the relationship was significant after controlling for organizational level.

Our analysis did not support the hypothesis that organizational level would moderate the relationship between behavioral courage and job performance. At the same time, the significant differences between the employees at low and high hierarchical levels (based on their supervisors’ assessment) found in the analysis of variance test did suggest that managers at the top level were perceived as demonstrating courageous behaviors to a greater extent than employees at the low level. One possible explanation could be that employees at the top level are expected to exhibit more behavioral courage. This is somewhat corroborated by the substantive literature that underscores the unique requirements of managerial roles at different organizational levels (Mumford, Campion, & Morgeson, Reference Mumford, Campion and Morgeson2007; Kaiser & Craig, Reference Kaiser and Craig2011). In other words, the complexity and nature of work at the top level may indeed demand more of such behaviors.

As seen in Figure 1, the study results revealed a significant interaction effect between behavioral courage and gender (b=0.13, p=.001). More specifically, when both genders exhibited high levels of behavioral courage, both male and female managers were seen as high performers at a similar level. At the same time, the results portrayed a different story when female and male managers demonstrated only some (or no) patterns of behavioral courage. In the latter case, males appeared to be rated significantly lower than females on job performance. A possible explanation is that our study may have tapped into the gendered social construction of heroic leaders that influences the characterization of men and women as heroes. Rankin and Eagly (Reference Rankin and Eagly2008) found that, when participants were asked to identify courageous business leaders, they were more likely to name well-known business executives, the majority of whom were men. Echoing Rankin and Eagly (Reference Rankin and Eagly2008), it appears that the social construction of heroic leaders (typically seen as men) sets higher expectations for men than women in the business context, when it comes to this type of behavior. In other words, demonstrations of behavioral courage by males and females are likely to be perceived differently by supervisors. In fact, men appeared to be disadvantaged in this case; when male managers demonstrated only some patterns of behavioral courage, they were rated lower on job performance than female managers who demonstrated equivalent levels of behavioral courage. At the same time, as our results suggest, the differences disappear when both male and female managers demonstrate high levels of behavioral courage.

This significant interaction effect between behavioral courage and gender can also be explained by Eagly, Wood, and Diekman’s (Reference Eagly, Wood and Diekman2000) social role theory, which asserts that, in their roles, women are typically seen as more communal, whereas men are seen as more agentic. Extending Eagly, Wood, and Diekman’s (Reference Eagly, Wood and Diekman2000) proposition, it appears that the incongruity of expectations about women (i.e., more communal and less assertive) and about the leader position in an organization (the leader role) may make patterns of behavioral courage from women more noticeable and thus rated higher. However, when patterns of behavioral courage are demonstrated to a large extent, the effect of gender becomes insignificant.

Practical implications

As discussed in our literature review, and empirically supported in this inquiry, behavioral courage appears to benefit organizations in various important ways (Kilmann, O’Hara, & Strauss, Reference Kilmann, O’Hara and Strauss2010; Pury & Lopez, Reference Pury and Lopez2010; Koerner, Reference Koerner2014; Detert & Bruno, Reference Detert and Bruno2017). This paper, in particular, identified five such behaviors that are representative of behavioral courage in the workplace and also found that there is a positive relationship between supervisors’ ratings of behavioral courage and job performance in for-profit organizations. Corroborated with the growing literature on courage in the workplace, the study results provide important practical implications.

Given that courage, as well as cowardice, may be contagious (Pury, Lopez, & Key-Roberts, Reference Pury, Lopez and Key-Roberts2010), we suggest that the type of behaviors examined in this study may provide important guidance to leaders, managers, and human resource development practitioners in organizations. As leading by example has long been recognized as an important leadership practice (Kouzes & Posner, Reference Kouzes and Posner2008), organizational leaders should act as role-models and behave in a courageous manner when a situation necessitates it. In this sense, transformational leadership may be a suitable approach for enlisting behavioral courage from employees, because leaders seek ‘the greatest good for the greatest number’ and ‘are concerned about doing what is right’ (Bass, Reference Bass1998: 174). Further, with increased attention to moral behaviors and ethical decision making in organizations, ethical leadership may also lend support to promoting courageous action and moral courage among organizational members (Brown & Trevino, Reference Brown and Treviño2006; Sekerka & Bagozzi, Reference Sekerka and Bagozzi2007).

Echoing Lester, Vogelgesang, Hannah, and Kimmey (Reference Lester, Vogelgesang, Hannah and Kimmey2010), we also suggest that the development and facilitation of behavioral courage in the workplace should be a responsibility of leaders. Research indicates that providing training programs and developmental interventions can be an effective way to foster behavioral courage in organizations (Kilmann, O’Hara, & Strauss, Reference Kilmann, O’Hara and Strauss2010). For example, training programs that involve role playing and simulation-based activities have been suggested as effective tools to develop individual skills and self-competence, to act on situations that require courageous work behaviors (Harbour & Kisfalvi, Reference Harbour and Kisfalvi2014; Simola, Reference Simola2015). Training programs may also include identity-based interventions that point to individual awareness-raising, ethical self-regulation, and courageous decision-making to encourage morally courageous acts (Sekerka & Bagozzi, Reference Sekerka and Bagozzi2007; May, Luth, & Schwoerer, Reference May2014). As such, we suggest that organizational leaders and managers utilize such developmental interventions to effectively promote skills, self-competence, and values that are needed to foster behavioral courage in the workplace (Sekerka, McCarthy, & Bagozzi, Reference Sekerka, McCarthy and Bagozzi2011).

Further, as our results indicate, behavioral courage is likely to be beneficial irrespective of the position in the organizational hierarchy. In other words, human resource interventions on promoting courage in the workplace should not be limited to the managers at the top of an organization. Specifically, Worline, Wrzesniewski, and Rafaeli (Reference Worline, Wrzesniewski and Rafaeli2002) asserted that the courageous behaviors of an individual could influence the agency of other organizational members, thus increasing a collective sense of organizational agency. Given recent empirical research supporting the link between courageous actions and innovation in organizations (Koerner, Reference Koerner2014), as well as the argument that the failure of courage is directly linked to failures in organizational performance (Worline, Wrzesniewski, & Rafaeli, Reference Worline, Wrzesniewski and Rafaeli2002), we suggest that identifying and removing constraints that suppress behavioral courage at all organizational levels may be instrumental to sustaining competitive organizational performance.

In summary, in line with the growing literature on courage in the workplace (Koerner, Reference Koerner2014; Detert & Bruno, Reference Detert and Bruno2017), the results of this study point to the importance of creating and sustaining an organizational culture where behavioral courage can be developed and exercised. As the workplace is continuously reported to be a place where leaders lack trustworthiness and employees often pursue self-interests rather than collective purposes, the need for courage scholarship cannot be overstated (Detert & Bruno, Reference Detert and Bruno2017). With regard to practice, we suggest that organizational leaders, human resource development, and organization development professionals should increase their efforts in promoting the value of being courageous, developing ‘courage’ skills in employees, and also reducing the fear of workplace failure.

LIMITATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

Limitations

There are several limitations in the present study. First, the behavioral dimensions that the study employed were based on convenience. Although we developed the measures while taking face validity under consideration, we were somewhat limited in our options. Specifically, we were not able to consider cognitive, emotional, and other relevant aspects that the act of courage in the workplace may entail (Rate et al., Reference Rate, Clarke, Lindsay and Sternberg2007). Second, our study was based on a cross-sectional design and leaves room for speculation in regard to causality among the constructs. To overcome this limitation and improve the generalizability of the results, future research may rely on longitudinal methods and time-lagged designs when examining the relationship between behavioral courage and other organizational constructs. Third, although the use of direct supervisors’ ratings (as external observers) was supported by theory (Harbour & Kisfalvi, Reference Harbour and Kisfalvi2014), including other ratings (i.e., peers, direct reports, etc.) could have yielded a somewhat broader perspective on the observed behaviors. In addition, our research design did not permit controlling for the effects of larger social (and structural) systems. As various organizations (and organizational units) appear to constrain or foster this type of behavior (Kilmann, O’Hara, & Strauss, Reference Kilmann, O’Hara and Strauss2010), multilevel modeling (i.e., using a nested structure) could have shed more light on the relationship between acts of courage in the workplace and the workplace itself. Finally, as our data represent behavioral patterns that may be typical for managers in mid- and large-sized for-profit organizations, we do not expect these results to be generalizable to nonprofit or small- and entrepreneurial types of organizations.

Future research

While previous research attempted to explore various individual characteristics that may be predictive of courageous behavior (e.g., O’Connell, Reference O’Connell2009), an inquiry into specific elements of organizational contexts that might promote behavioral courage could also advance our understanding of the construct. A qualitative inquiry into the conditions that may induce acts of courage in some organizations and, in turn, suppress such acts in others could be one of avenues for future research. In addition, as we suggested above, a multilevel analysis could be also considered as a method for studying the effects of larger social settings on behavioral courage. Specifically, being able to control for larger (nested) structures could advance our understandings of the effects of various social contexts (e.g., a team, an organizational unit, an organization) on individual behavioral courage. To wit, the use of hierarchical linear modeling and other similar statistical methods could be a promising direction in research on courage in the workplace.

As courageous behavior appears to be positively associated with job performance, this type of behavior could be seen as one of the important factors predicting career advancement (i.e., promotion). Future research could explore whether having higher ratings on behavioral courage actually leads to the employees’ career advancement in their organizations (or even lead to turnover intentions). An inquiry into the relationship between behavioral courage and career advancement (promotion) and factors that affect this relationship would provide interesting insight into both practice and theory. Similarly, as some organizations (or units) may fall into bureaucratic or fearful types (Kilmann, O’Hara, & Strauss, Reference Kilmann, O’Hara and Strauss2010), where employees exhibit low acts of courage, another avenue for future research could be an exploration of employee motivation to stay with or leave such organizations, once they find that courageous behavior is inhibited. Similarly, an investigation of the effects of various organizational variables on the relationship between behavioral courage and risk of career derailment (or turnover intention) could provide useful insights to organizational leaders. Likewise, exploring the relationship between behavioral courage and job performance (or other organizational outcomes) in different national contexts may also be a promising avenue for future research. Rather than using cultural region analyses (i.e., GLOBE country clusters), a country-by-country analysis could provide more useful findings (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Quast, Jang, Wohkittel, Center, Edwards and Bovornusvakool2016).

Lastly, this study assessed gender as male and female participants, which is consistent with prior studies that examined the concept of behavioral courage (e.g., Palanski et al., Reference Palanski, Cullen, Gentry and Nichols2015). Future research on courage in the workplace should add attention to the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community. For instance, an investigation of behavioral courage across different industries, including those industries that are traditionally considered hostile to the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community (Collins & Callahan, Reference Collins and Callahan2012), could shed more light on the pressures of acting courageously across a broader population.

CONCLUSION

Courage in the workplace is an emerging yet important construct. As recently noted by Detert and Bruno (Reference Detert and Bruno2017), a variety of perspectives, definitions, and approaches are needed to advance our understanding of the construct and its relationship with other important organizational outcomes. In this regard, our study has provided several important contributions. First, our results indicated that behavioral courage may lead to higher levels of job performance. Second, although the nature of work may set higher expectations for managers at the top regarding courageous behaviors, individual acts of courage appear to be beneficial to organizations irrespective of the manager’s position in the organizational hierarchy. Finally, we find that, while the social construction of courageous business leaders may have set higher expectations for men in the contemporary workplace, when behavioral courage is demonstrated to a large extent, it is equally associated with high levels of performance for both genders. We hope that our findings stimulate future interests in empirically testing the utility of behavioral courage in the workplace and its relevance to important individual and organizational outcomes.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Brenton M. Wiernik and several other colleagues from the University of Minnesota for their helpful comments on earlier versions of the manuscript.