To shun the surly butcher’s greasy tray,

Butcher’s, whose hands are dy’d with blood’s foul stain,

And always foremost in the hangman’s train.

The Art of Walking the Streets of London by John Gay (1685–1732)

Introduction

Annibale Carracci’s The Butchers Shop (1580–1583) is considered to be one of the most significant paintings of the mid-Renaissance. Apart from its acclaimed aesthetic qualities and its acknowledged contribution to the genre, the work has been recognized by many scholars for the symbolism inherent within its construction. Numerous interpretations have been put forward to suggest the intrinsic meaning contained within this visual narrative. Its contribution has been discussed within the context of the burlesque comic tradition,Footnote 1 commemorative portraiture,Footnote 2 the reassertion of artistic traditions after the disaster of mannerism, and as a metaphor for Christ’s sacrifice.Footnote 3

The aim of this paper is to suggest a reinterpretation of Carracci’s work, one that places the composition within the context of Bologna’s economic and cultural history. To date, few studies have explored how commercial activities have been represented in Renaissance imagery; this is despite such works being created during periods of widespread social reconfiguration, market commodification, and institutional hegemony. Seen as a work with a specific communicative role, it will be argued that The Butchers Shop not only acknowledges the social standing of its patron; it seeks to establish the moral authenticity of the profession it depicts. Through the use of identifiable codes, signs, and symbols, Carracci’s painting reasserts the reputation of the butchery trades, reinforces the value of the guild system, and comments upon the efficacy of papal interference in business endeavor.

The authority of the visual image has been historically recognized and the notion that a work of art may seek to communicate specific meaning is not new.Footnote 4 This paper, therefore, begins by exploring the legitimacy of the painted form and detailing why artistic works have been able to shape attitudes, influence behavior, and direct public opinion. The value of a visual interpretation is in part dependent upon the cultural, political, and social environments from which it was derived.Footnote 5 This paper, therefore, briefly describes the social and political events within sixteenth-century Bologna that remain key to any reinterpretation. The Butchers Shop itself is then examined before the significance of Carracci’s painting is discussed and a series of conclusions are drawn.

The Legitimacy of the Visual Form

Visual narratives may serve to inform our understanding of history by offering contemporary commentators an underutilized and often unexplored reference source.Footnote 6 Despite the temporal dislocation that exists when attempting to view a historical image through the eyes of the artist, careful contextualization can help inform subsequent interpretations. This, however, is not to suggest that artistic works remain impartial or independent of human meaning. Rather, they represent a complex social edifice in which both knowledge and truth may have multiple interpretations depending upon the context or setting. Indeed, through the blurring of actual and fictitious events, works of art are often criticized for creating an "illusive realty" in which narratives have little objectivity and act primarily in the interest of dominant groups or individuals.Footnote 7 Whereas works of art may have offered sixteenth-century audiences hope, encouragement, and enlightenment, their value, therefore, extended beyond any Cuccagnian ideal.Footnote 8, Footnote 9 Through established signs, codes, and symbols, paintings represented a form of communication that exuded authenticity Footnote 10 while simultaneously declaring to audiences what was both “true” and “genuine.”Footnote 11 Visual narratives may, therefore, reflect commonly held beliefs or preconceived ideas and, despite not always being universally agreed to or historically accurate, would have been considered legitimate and authoritative.

European painting during the sixteenth century witnessed a move away from the “contemplative abstract form” that characterized many medieval works. Artists and artisans began to place greater emphasis upon the human figure and the portrayal of more natural imagery.Footnote 12 While in Italy religious paintings continued to remain the most popular subject matter, a growing interest was witnessed in other forms of composition. The demand for land and seascapes, battle scenes, and still life compositions reflected a commodification of the market for artistic works as well as a form of post-Reformation religious iconoclasm. The reemergence of the merchant classes after the economic stagnation of the early fourteenth century and the devastating effects of the Black Death saw a growth in consumerism and the large-scale production of artistic works.Footnote 13, Footnote 14 The strong link between the Flemish art market and the northern Italian cities during the sixteenth centuryFootnote 15 fuelled a growing interest in “genre” art with images of street scenes, markets, bars, and taverns proving particularly popular.Footnote 16 The demand for these works spanned the social spectrum and contradicted the previously held belief that noble audiences were concerned only with high-order themes and representations of ideal beauty.Footnote 17 Far from being the domain of vulgar artists and peasant audiences, the demand for scenes of everyday life proved popular across the classes.

Despite the growing availability of printed texts during the Renaissance, visual imagery continued to represent a widely accepted and legitimate form of communication. In Italy, this was in part due to widespread levels of illiteracyFootnote 18 as well as attempts by the church and state to limit the persuasive power of the printed word. To discourage moves toward more public knowledge, works produced in the vernacular during the Catholic Reformation often remained limited to catechisms and teachings in moral conduct.Footnote 19 Unlike much of northern Europe, the overwhelming majority of doctrinal writings, church legislation, and higher instructions remained written in Latin and accessible only to clergy, the professions, and the educated elite.Footnote 20 In contrast, visual narratives such as paintings, sketches, frescos, and drawings remained accessible to the wider populace and represented objects with “uniquely high and concentrated information loads”Footnote 21 that could move beyond the aesthetic to convey deeper, intrinsic meaning.Footnote 22

Successfully interpreting any work of art remained reliant upon audiences being able to contextualize the narrative within their own socioeconomic and political landscape. Contemporary attempts to unlock the messages embedded within a historical composition similarly requires an appreciation of the prevailing artistic conventions as well as a recognition of the societal influences that shaped its production. A reinterpretation of Annibale Carracci’s The Butchers Shop, therefore, necessitates careful contextualization and an understanding of the events that informed the creation of this visual narrative.

The Historical Context

Across many parts of Europe, the second half of the sixteenth century represented a period of significant cultural transformation and social enlightenment.Footnote 23 Economic advancement was complemented by intellectual reform, scientific progression, and literary emancipation. The ability of both the state and the church to control the channels of communication was also increasingly challenged by the growing demand for privately commissioned works of art. While acknowledging the difficulties that surround any contextualization, it will be argued that the narrative contained within The Butchers Shop reflects a series of underlying pressures for cultural and socioeconomic reform accompanied by ongoing tensions in the Italian political and religious landscape. Three issues in particular inform our interpretation of Carracci’s work. These include the historical relationship between the city of Bologna and the papacy, the public perception of the guild system, and the image and reputation of the butchery profession.

Tensions between Bologna and the Papacy

Traditionally, the birth of the commune of Bologna dates from the early twelfth century when its citizens were granted imperial protection by Henry V and given leave to pursue their own rights and customs.Footnote 24 Over the following three centuries, the city alternated between signorial and republican regimes punctuated by periods of foreign occupation. Despite the uncertainty that stemmed from these protracted phases of political, social, and economic volatility, Bologna continued to assert its civic and religious independence from Rome.Footnote 25 In the 1390s, the city reaffirmed its autonomy with an oligarchic constitution and the construction of a series of buildings around a new civic square. After resisting further challenges from the Visconti of Milan and the papacy during the first half of the fifteenth century, a 1447 concordat with Pope Nicholas V offered the city a degree of stability by establishing a governo misto. This provided a framework for the retention of local autonomy, while at the same time placing Bologna under papal jurisdiction.Footnote 26

From the beginning of his pontificate in 1503, Pope Julius II sought to again reassert the authority of Rome by reclaiming its papal territories. In 1506, with the support of the French and the Swiss guard, he removed Giovanni Bentivoglio as quasi-signorial ruler of Bologna and declared himself as supreme ruler.Footnote 27 Despite his reputation for self-aggrandizement, Giovanni II had been credited with bringing a period of relative peace and stability to the city as well as embarking upon an ambitious plan of building and architectural rejuvenation.Footnote 28 Except for a brief period between May 1511 and January 1512, when a government was reestablished under the leadership of Giovanni’s son, Annibale II, Bologna remained subject to papal rule for the next three centuries.

According to Terpstra,Footnote 29 the early sixteenth century represented a period when the city negotiated and accommodated its own subordination. Under papal rule, the government of Bologna was divided into two elements. The Senate was comprised of forty members with each representative being personally selected by the pontiff. While this body presided over civic affairs, they remained subordinate to the papal legate who, as the Pope’s representative, took responsibility for justice and public order. Although the Senate positioned themselves as defenders of Bologna’s liberty, they also became responsible for shaping a civic identity that placed the city firmly within the papal state.Footnote 30

Rome’s patronage allowed the city to project an image of wealth and stability both at home and abroad. In 1530, Bologna gained international recognition when it saw Charles V crowned as Holy Roman Emperor and the treaties of Cambrai and Barcelona confirmed by Pope Clement VII. By the second half of the sixteenth century, Bologna had a population approaching sixty thousand, an established religious community, and, partly due to having one of the largest universities in Europe, an eclectic range of intellectual and scholarly inhabitants. Its thriving economy was primarily built around manufacturing and the silk industry, the latter of which employed around a quarter of the city’s inhabitants. It had evaded the plagues that had affected northern Italy since the mid-1550s and had escaped the famines that had decimated the cities of Modena, Parma, and Pavia.Footnote 31

Despite Bologna becoming the second city of the Roman church, the autonomy that it had cultivated over the previous 150 years had been lost. The university, an enduring symbol of civic pride and local identity, was centralized on a papal site, a move that both ensured conformity to the prevailing Catholic dogma as well as signified the power of Rome. The papacy sought to further reaffirm its domination over the civic authorities through the erection of iconic symbols such as Michelangelo’s statue of Julius II and Pius IV’s Fountain of Neptune. The construction of a papal fortress at the Porta Galliera, the demolition of sections of the commercial center, and the relocation of part of its population not only saw a change in the central topography of Bologna; it represented a further symbolic manifestation of Rome’s authority over the city.Footnote 32

Given the political stability and economic prosperity that Bologna experienced during this period, it is perhaps unsurprising that some of its citizens were able to amass significant personal fortunes through trade and enterprise. Any interference in the regulation of Bologna’s business practices was unwelcome and could be interpreted as a direct challenge by Rome to the city’s right to manage its own affairs. For example, despite a desire by the butchery guild to regulate the sale of meat themselves, the Bolognese government imposed a series of price controls on the industry. Concerned with a need to protect its poorest citizens and guarantee that meat remained affordable, a 1539 edict, La provisione et limitation sopra il precio delle carni, required set prices to be openly printed and displayed in shops and stalls. Not surprisingly, this proved unpopular among the city’s butchers, who pointed out that shortages in supply had led to increased costs from meat imports. To ensure butchers complied with the law and did not deliberately seek to defraud customers, an inspection body was also established. The Straordinari di carne became a common sight around the streets of Bologna as they sought to discourage activities such as under weighing or over charging. The price paid by a customer would be checked, and any butcher found guilty of fraudulent practices could be fined. This interference in the urban economy was seen a direct challenge to local government and did little to harmonize relationships between civic society, the Senate, and the papacy.Footnote 33

The Guild System

Scholars remain divided on the role played by guilds in medieval and early modern Europe. Whereas some argue they helped overcome structural market inefficiencies, others maintain they acted in the interests of their membership at the expense of the wider economy.Footnote 34 Such contrary views may reflect the fact that throughout Europe different guilds served a variety of functions, undertook multifarious activities, and evolved over hundreds of years. As a consequence, it remains difficult to generalize about their power, influence, and links to the political economy.Footnote 35 Moreover, whereas some commentators have distinguished between European craft and merchant guilds,Footnote 36 this distinction can be problematic, as individual institutions may have simultaneously been involved in a range of commercial activities, including manufacturing, wholesaling, and retailing, as well as international trade.

The earliest listing of guilds in Bologna dates from 1259 when a total of twenty-one were recorded in the city. By the beginning of the fourteenth century, guilds had come to occupy a dominant position within the sociopolitical landscape.Footnote 37 Continued economic growth in areas such as mercantile banking, textile, and leather production led to the demand for skilled workers and an expansion of the migrant population. Innovations in production and the emergence of new industries also led to the formation of new guilds. For example, the wool guild that had been established in 1256 saw itself fragment between those who produced the rough wool cloth (societas lane bixelle) and those who produced fine wool (societas lane gentilis). Although the silk industry had been slower to develop, by 1317 there were at least twelve silk mills operating in Bologna, and by the end of the fourteenth century, the Silk Guild had established itself among the most influential trade bodies in Bologna.

However, by the sixteenth century, the role of guilds across Europe had changed. In Italy, economic expansion saw many industries evolve their production processes around a system of labor specialization. For example, the silk industry involved coordinating a network of separate weaving, spinning, and dyeing workshops. As production expanded to the countryside, and the use of nonguild labor for certain manufacturing processes became increasingly common, many craft masters found themselves transformed from independent artisan into wage earner.Footnote 38 Those who controlled the production process (the merchant-entrepreneurs) oversaw a period in which guilds became mechanisms for labor market control rather than representative bodies concerned with the interests of their membership.Footnote 39, Footnote 40

In an attempt to maintain their autonomy and protect their reputation, many guilds became self-preserving institutions closely aligned with various political authorities who supported their restrictive practices through municipal regulations and the legal system. In Bologna, it has been suggested that guilds became associated with the exercise of both monopolistic and monopsonistic power. By acting as powerful cartels that restricted the purchase of raw materials and the sale of finished goods, they discouraged innovation, reduced investment, and inhibited market evolution.Footnote 41, Footnote 42 For example, a legal edict of 1461 that prevented the establishment of new silk mills in the countryside around Bologna created an urban monopoly and consolidated power in the hands of a small number of established families. Moreover, as the raw silk produced in Bologna was considered to be among the highest quality in Italy, attempts were made by the Arte della Seta Footnote 43 to block its export and restrict production to only local businesses.Footnote 44

In contrast, others have argued that it is too simplistic to consider guilds as anachronistic institutions whose anticompetitive practices and restrictive membershipsFootnote 45 resulted in the inefficient allocation of market resources.Footnote 46 Their ethos of shared values and social cohesion represented key tenets in understanding civil society. Guilds provided broader social and economic benefits while at the same time affording support and protection to their membership.Footnote 47 The provision of quality guarantees provided consumers with assurances in markets often devoid of product standards, whereas the creation of trademarks offered an easily recognizable visual identity and acted as a form of brand differentiation.Footnote 48 For those who joined a guild, membership offered a range of benefits, including welfare support and cheap credit, as well as access to the cumulative commercial expertise of other members.

EpsteinFootnote 49 further argues that one of the principal benefits of the guild system lay in its apprenticeship scheme. Rather than symbolizing an excessively long restrictive practice, apprenticeships helped share the costs and benefits of training, overcome seasonal variations in the labor force, and reduce the poaching of qualified individuals. Moreover, the existence of formal training and mentoring processes allowed guild members to further differentiate themselves and attract better quality staff. Rather than representing a means of labor market control, the apprenticeship system represented a major investment in human capital.

Far from being resistant to change and unable to cope with variations in market demand,Footnote 50 guilds often exhibited innovative and flexible working practices. In Bologna’s silk industry for example, the coordination of production phases (weaving, spinning, and dyeing) helped reduce transaction costs and maintain product quality.Footnote 51 Moreover, the tendency for members to physically locate in local clusters not only ensured that standards were maintained between competing practices; it encouraged technological diffusion through labor market spillover.Footnote 52, Footnote 53

Although butchers had been operating in Bologna since Roman times, their power and influence was consolidated during the late twelfth century when the government gave them permission to form their own guild (Arte dei Beccai). The matricule of 1294 noted that the Butchers Guild of Bologna had 752 members.Footnote 54 Through a series of subsequent land purchases in the years following its creation, the guild established a market in the heart of the city, and by the end of the thirteenth century it had succeeded in creating a virtual monopoly over the supply of meat. Over the next four centuries, the Butchers Guild continued to grow in both power and influence, its members occupied key political and civic posts within the city, and butchers became the only guild able to constitute itself into an armed society.Footnote 55, Footnote 56

Butchers, Fleshers, and the Theriophilic Paradox Footnote 57

Driven in part by an expansion of international trade, the thirteenth century saw the rise of the Mercator. These wholesale merchants accumulated significant wealth and power and became a respectable, political class in their own right.Footnote 58 By the sixteenth century, the growth of the professional classes in Italy challenged the prevailing social hierarchy and called for a reassessment of the divisions that defined rank and order. The simple dichotomy between the laboring third estate and the nonworking nobility appeared increasingly irrelevant in the face of a burgeoning bourgeoisie.

In place of the old divisions came new definitions that included a distinction between intellectual and manual labor. Those in the former category represented the “noble metier” and applied rational skills to commercial practices. Their intellectual and social position was reinforced through their patronage of the arts and the cultured leisure pursuits in which they indulged.Footnote 59 In contrast to the honorable activities of the merchant and banker, those who worked with their hands were regarded as “vile metiers” and considered vulgar and dishonest. The basis of this distinction stems, in part, from Cicero’s De Officiis and his judgment on honorable and dishonorable occupations.Footnote 60 The attainment of summum bonum (supreme happiness) was to be achieved through exemplary behavior, part of which was the observation of one’s ethical and moral duties. For example, activities that benefitted the community (such as the importation of goods for distribution) were seen as honest and worthwhile. In contrast, middlemen such as retailers worked only for their own benefit and were considered to be at the bottom of the social hierarchy.

Within this hierarchy, butchers occupied a paradoxical societal position. Despite the significant wealth accumulated by some individuals and the power exerted by the Butchery Guild, their status among Bologna’s social elite remained ambiguous. An edict issued in 1453 by the Cardinal Legate Bassarion, developed a social classification that, for the first time, distinguished beyond that of citizen and noncitizen.Footnote 61 Butchers were classified as being below bankers, drapers, and silk merchants but above those “who did not practice any trade or craft” (viles).Footnote 62 Nobles, from whom the city’s civic oligarchy were drawn, comprised third generation citizens who had a doctor or knight in the family and did not pursue a manual craft or trade. Although guild membership was not prohibited, it was limited to one of the four artes superiores. Footnote 63 Social rank was reinforced through the city’s sumptuary laws that attempted to place restrictions on the types of clothing and jewelry different classes of citizens could wear in public. Whereas the impact of such regulations may have remained more ideological than tangible, they did little to promote the social mobility of the butchery profession among Bologna’s civic elite.Footnote 64

The reputation of butchers was further undermined by those who considered the sale of meat a particularly “sordid” matter. Products such as meat, fish, and vegetables were associated with the lower functions of the body (consumption, ingestion, and excretion) and considered to be physically and morally unclean.Footnote 65 This was reinforced by the association of butchery with contagion and disease. Waste from the slaughter and dismemberment of animals regularly spilled into the streets and polluted water supplies.Footnote 66 Many civic authorities considered the butchery trade an offensive nuisance open to malfeasance and corrupt practice. Although recognizing the importance of the meat trade, local regulations often sought to prohibit the slaughtering of animals in public places or have such activities conducted outside of the town walls.Footnote 67 In Bologna, from the mid-thirteenth century, concerns over health and hygiene led to the establishment of a single city abattoir and restrictions on the erection of butchery stalls. However, the influence of the Butchers Guild was evidenced by the location of the complex at the Porta Ravegnana in the center of the city. Its position next to the Aposa Canal served as a meat market until the 1560s, when a new facility was proposed. Resisting any pressure to relocate outside of the city walls and away from the urban populace, the new market established itself close to the existing site.

Prejudices against the butchery profession can also be linked to a more profound, early modern philosophical discourse on the morality of animal slaughter and the impact of meat consumption upon the human soul. The doctrines of the church and the Great Chain of BeingFootnote 68 had established that animals were sentient beings who experienced feelings, perceptions, and memories. Although implicit within this theory was the basic superiority of man, the church also accepted that animals were afforded a higher place than lifeless matter within God’s hierarchy.Footnote 69, Footnote 70 These edicts, however, came to be questioned by scholars such as Michel de Montaigne (1533–1592) and Sir Thomas More (1478–1535) who queried whether there was a distinction between human reason and animal reaction.Footnote 71 If the superiority of humans over animals could be questioned, then the difference between man and beasts was not absolute. As animals were able to exercise logic, discrimination, judgment, and cunning, there were few differences between them and humans. By the end of the sixteenth century, this theory had become more explicit among intellectuals, artists, and moralists. The consumption of meat was considered by some as being a physiologically unnatural act that made men cruel and ferocious.Footnote 72 Such attributes took on symbolic significance during the Renaissance, with visual comparisons between man and beasts being used to highlight human failings. The visual depiction of the slaughtering of animals signified death and corruption, and, as a consequence, butchers were considered merciless cruel figures comparable to that of a public executioner.Footnote 73, Footnote 74

Placed within the context of Bologna’s business and cultural history and set against a background of institutional hegemony, social mobility, and occupational disrepute, The Butchers Shop (1580–1583), it will be argued, represents a visual narrative that asserts the efficacy of the butchery profession. By contrasting the symbols of exemplary behavior with negative representations of Rome and the papacy, it is suggested that Carracci seeks to enhance the societal reputation of his patron and reinforce the legitimacy of the guild system, as well as establish the butchery trade as being among the most noble of metiers.

Annibale Carracci’s The Butcher’s Shop: A Symbol of Virtuous Endeavor?

Until the late sixteenth century, depictions of commercial activity were confined (in Europe at least) to either frescos or footnotes in manuscripts and carried little iconographic meaning.Footnote 75 This mirrors the more general observation that prior to the Renaissance, “work” as a theme had traditionally been ignored by the artistic establishment who deemed it unsuitable for intellectual attention.Footnote 76 From the 1550s onward, increasing numbers of artistic works depicted individuals undertaking manual activities. However, subjects were often portrayed as deformed characters, and their inclusion acted to remind audiences of the stigma associated with physical toil. Such images not only reflected the view that manual labor distorted the body over time; by reinforcing the concept of the vile metier, they further strengthened the hegemony of the ruling elite. Whereas paintings such as Vincenzo Campi’s (ca. 1530–1595) Fishmongers (ca. 1580) and Francesco Villamena’s (1564–1624) print, Castagnaro (ca. 1600), sought to highlight the grotesque nature of those who labored with their hands (villano),Footnote 77 Annibale Carracci’s painting, The Butchers Shop (ca. 1580–1583), represents a departure from such representations and emphasizes the dignity of work (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Annibale Carracci, The Butcher’s Shop (c1580–1583).

The picture is one of two separate scenes of butcher’s shops painted by Carracci around 1582. Figure 1 is in the collection of Christ Church College, Oxford, while the other hangs in the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas.Footnote 78 Despite the latter being smaller (only one-twelfth the size), it is generally not considered to be a preliminary sketch for his much larger composition. DickersonFootnote 79 notes that unlike the spontaneous and naturalistic style of the Kimbell painting, the Oxford version is ordered and symbolic.Footnote 80 Its size and scale strongly suggest that this was a work specially commissioned by a wealthy patron. Although not unequivocally proven, The Butchers Shop (Figure 1) is generally attributed to the Canobbi family who were members of the Butchers Guild of Bologna and controlled around a quarter of the city’s meat trade.Footnote 81, Footnote 82

The Canobbi’s had amassed their fortune during the 1560s, when Giuseppe and Girolamo Canobbi constructed a new butchers’ complex. In return for funding the project they were granted stall holder rights. The revenues they accumulated from the subsequent leasing of the stalls caused their civic status and position within Bologna’s social hierarchy to rise prominently. Their affluence afforded them an almost aristocratic lifestyle that included their own private chapel in the church of Santi Gregorio e Siro. The commissioning of an altarpiece (subsequently painted by Annibale Carracci) not only signified devotion and reverence to God; it represented a testament to the brothers’ success. Whether prominently displayed in a church, in the home, or at a place of work, paintings were symbols of wealth designed to carry meaning to all those who viewed them. Although it may remain impossible to conclusively determine the intended audience for The Butchers Shop, an understanding of the historical context allows us to suggest that the painting could conceivably have been aimed at the city’s new urban elite. During a period that had witnessed the rise of the professional classes, Carracci’s work addresses the paradoxical societal position of the Canobbi family, reaffirming their position within Bologna’s evolving social hierarchy.

The Canobbi’s choice of artist remains significant. Although trained in the mannerist style that emphasized a highly idealized approach to imagery, Carracci displayed a fascination for the everyday world that surrounded him. His eclectic style and his ability to emulate the compositional form of established classical masters such as Raphael and Michelangelo is evidenced in a number of his works, including The Butchers Shop. Footnote 83 When he, together with his brother and cousin, founded their own academy (Accademia degli Desiderosi) in 1582, Annibale had already developed a reputation for realistic, empathetic portrayals of working people. His series of eighty drawings of workers and tradesmen in Bologna (Arti di Bologna) approach each subject with a degree of sympathetic humor and did much to popularize genre painting in Italy.Footnote 84

The painting itself depicts a scene with four individuals undertaking the everyday activities associated with the preparation and sale of meat: the slaughter, the dressing, the weighing, and finally the purchase by the customer. The sympathetic rendering of the subject matter is reinforced by the positioning of characters and objects within the painting. The workers have their backs to the two customers and, instead, seek to communicate their activities to the audience. The table that displays the meat is similarly tilted toward the viewer and faces outward rather than in the direction of those in the shop. Despite the potentially chaotic milieu, the scene is one of order and discipline, and the workers are shown to be completing their tasks with great dignity and professionalism.

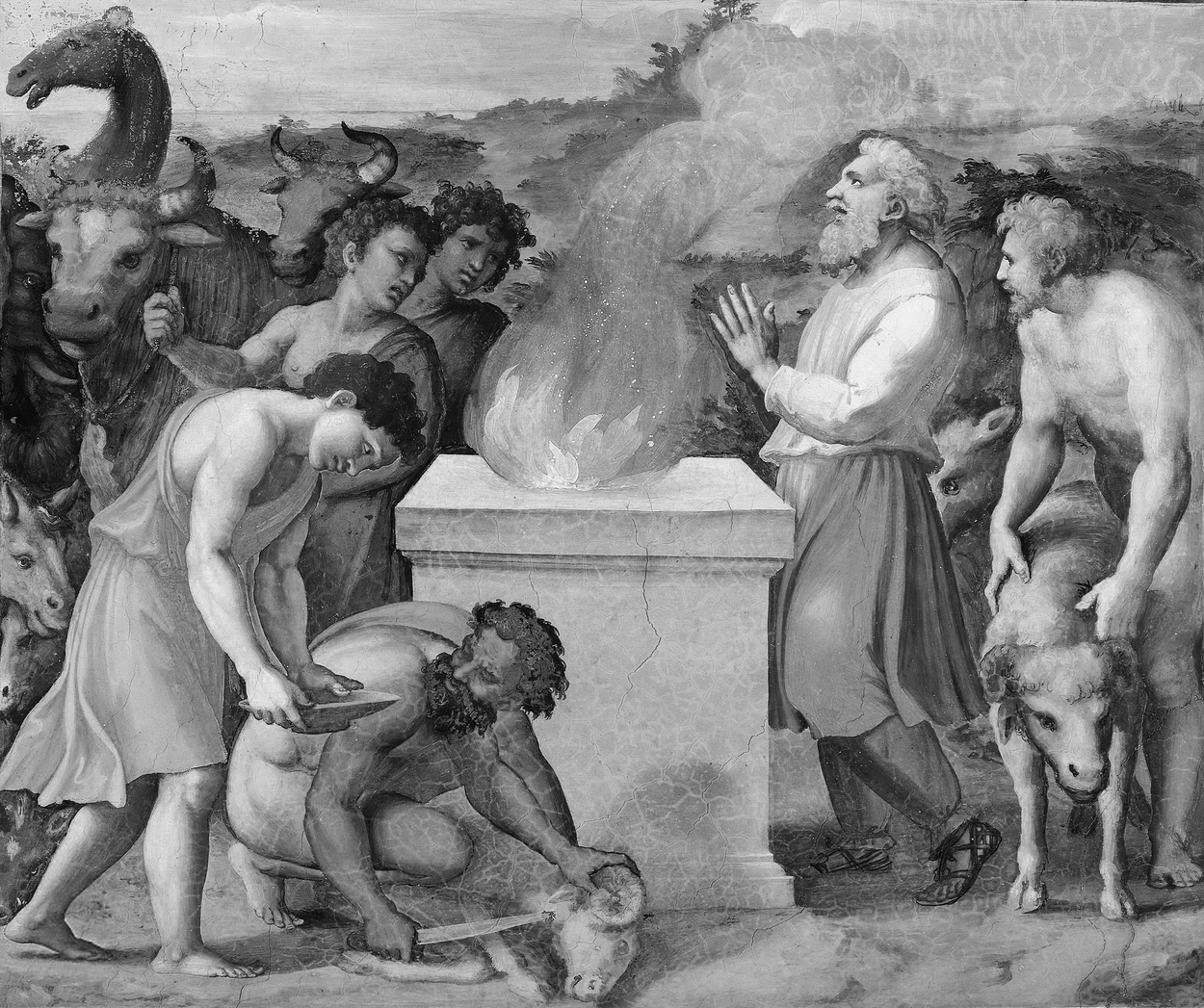

The composition reflects Carracci’s eclectic skills as an artist and draws upon works from High Renaissance art, in particular Michelangelo’s Sacrifice of Noah on the Sistine Chapel and Raphael’s fresco of the same title in the Vatican Loggia (Figures 2 and 3). Both works depict acts of spiritual devotion around an altar that is located at the center of the work. Noah, accompanied by his wife and followers, seeks to thank God for his salvation after the flood by officiating over a sacrifice of birds and animals. In The Butchers Shop, the upward pointing left arm of the master butcher has been compared to the raised hand of Michelangelo’s Noah, whereas the figure crouching before the altar serves as the model for the apprentice. In Raphael’s work (Figure 3) the similarity between the kneeling figure and the butcher’s trainee is particularly apparent. Parallels may be drawn in the turned position of the head, the hands holding the animal down, and the clutching of the knife.Footnote 85 By substituting the altar with a table and by placing his figures around this central feature, Carracci has not only replicated the structural form of the Renaissance masters; he has simultaneously elevated the status of the genre tradition and the butchery profession to the dominion of high art.

Figure 2 Michelangelo, The Sacrifice of Noah.

Figure 3 Raphael, The Sacrifice of Noah.

Rather than depict the damaging impact of labor upon the human body, Carracci’s figures are physically imposing and dominate the foreground of the painting. Even though each worker is formally positioned toward the audience, no one makes eye contact with the viewer. In a manner again reminiscent of the Sacrifice of Noah, (Figures 2 and 3), each character remains absorbed in their work. By linking butchers to sacred characters and emphasizing their devotion and commitment to the activities they must perform, Carracci seeks to establish the moral authenticity of the profession in the eyes of the viewer.Footnote 86

Unlike the almost cartoon artificiality of workers depicted in the mannerist tradition,Footnote 87 each character Carracci individualizes has different facial features and hairstyles.Footnote 88 Designed to evoke memories of more dignified subjects, the master butcher is portrayed as tall and upright and holds the scales in a manner reminiscent of a nobleman holding a sword.Footnote 89 The figure itself bears a close resemblance to Guillain’s engraving number 31 of the Straordinari di carne in Arti di Bologna (Figure 4).Footnote 90 Both are holding a steelyard and weighing meat in front of the customer. By linking the principal character in the composition to a public appointee, Carracci makes an implicit connection between the butchery profession and the upholders of Bologna’s civic authority.Footnote 91

Figure 4 Simon Guillain, Straordinari di carne.

Although butchery guilds sought to enforce quality standards and regulate the conduct of their members, their jurisdiction and authority were often limited.Footnote 92 As a consequence, some sellers were able to operate without the regulations that sought to govern their industry. The inclusion of scales in the composition, therefore, reaffirms the honesty inherent within the guild system and represent a transparent expression of the trust that purchasers could place in its members. Similarly, the butcher standing behind the table is reaching for a sprig of willow. Rather than wrap meat in paper for transport home, thin wooden branches were often used to create a form of carrying handle. Meat transported in this manner could easily be recognized and weighed by the Straordinari di carne. By including this activity in the composition, Carracci explicitly demonstrates how guild members uphold the law through the adoption of legitimate business practices.

WelchFootnote 93 notes that Renaissance economic theory was critical of the sale of products through intermediaries, as they provided an additional markup on goods and tended to vary prices according to circumstance. As a consequence, peddlers and street sellers were often criticized for being fraudsters who sought to exploit and deceive the customer. In contrast, vendors who had their own premises, butchered their own animals, and sold directly to the consumer, represented a form of exchange relationship that directly benefitted the community and remained characteristic of De Officiis’ honorable occupation. Carracci seeks to illustrate this exemplary behavior through the explicit display of a price list (bandi) in the top right corner of the painting. Despite the fraudulent practices of some sellers, those in The Butchers Shop adhere to the city’s regulations and price controls and, as such, they symbolize the morality and integrity of their profession and the guild system.

Kneeling in the front of the painting about to slaughter a ram is the butcher’s apprentice. Created during a period when the morality of animal sufferance and the ethics of meat consumption was being openly debated, the painting also serves to remind audiences of the professionalism and competence of the butchery trade. Whereas animals were slaughtered for food, the need to minimize suffering is also recognized. The composition’s link to higher order Biblical themes and the works of Michelangelo and Raphael suggests to audiences that they are witnessing representations of ritual sacrifice rather than acts of unnecessary cruelty. Far from being a disreputable occupation intent on destroying life, audiences are reminded how the guild system promoted skilled labor and maintained quality standards through their investment in human capital.

Even though the painting is of a butcher’s shop, there is very little blood either on the floor or on the clothing of the employees. Despite animal slaughter representing an everyday event and audiences being very familiar with the smell of decay and the sight of blood, Carracci’s painting stresses the cleanliness of the work space. The apron and shirt of the master is almost pristine white, and there is no blood on the hands or even under the fingernails of any of the workers. While the dog waits patiently under the table looking out expectantly for any scraps that may be dropped, its face shows disappointment. Through such imagery, the proficiencies of the guild and the minimization of animal sufferance are further reinforced. Renaissance audiences would be reminded that The Butchers Shop symbolized containment, order, and control rather than any representation of human failing.

Those who work in the shop contrast sharply with those who are patronizing it. Whereas WindFootnote 94 considers the presence of these characters as having both comic and erotic symbolism, this interpretation may be questioned. The inclusion of a soldier on the left of the painting is a halberdier and suggests a direct reference to Bologna’s position as a papal state and the historical tensions with Rome. The soldier for whom the meat is being weighed is portrayed as somewhat of a buffoon with an enlarged codpiece, drooping feather, and pike dangling between his legs. He is making a somewhat clumsy attempt to take money out of his purse. By examining the weaponry and clothing worn by the soldier, it is apparent that he represents a member of the Swiss guard.Footnote 95 In the sixteenth century, the papal militia usually carried a broadsword and halberd (pike). They wore a doublet or jacket that had no collar. This was fitted at the waist and ended in a point that went under the belt. Breeches were puffed and decorated with colored bands of material that went as far as the knee. Below this, soldiers usually wore stockings. Members of the Swiss guard wore various types of headgear that included a wide brimmed hat and a padded leather turban-shaped cap; these were normally trimmed with brightly colored pheasant or heron feathers.Footnote 96

Interestingly, Carracci has incorporated a codpiece into the soldier’s uniform. Although the codpiece represented a dominant fashion accessory during the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, by the 1580s its pop1ularity had waned.Footnote 97 It continued to remain in use, however, with members of the military, among whom it had acquired a more functional purpose. The spread of syphilis during the Renaissance has been well documented, with the first European epidemic being recorded in 1493.Footnote 98 Enlarged codpieces were used to provide padding and hold bandages in place, protect clothes against discharge, and provide the wearer with a degree of protection from items worn on the belt. Moreover, in an attempt to hide the disease, many soldiers incorporated the codpiece into their uniform, as those who carried syphilis were publicly persecuted, banned from shops, and in the case of soldiers, dismissed from the army.

Carracci’s inclusion of the Swiss mercenary appears to be a deliberate reference to the authority of Rome, and his unsympathetic portrayal of the character would not have gone unnoticed by sixteenth-century audiences. As members of the Pope’s guard, halberdiers were both exempt from taxes and able to slaughter their own livestock; it would, therefore, have been highly unusual to see one purchasing meat from an ordinary butcher’s shop.Footnote 99 By including the soldier in the composition, Carracci not only reminds audiences of Pope Julius’s retake of the city in 1506; he comments upon the increasing erosion of civic society through papal interference. Placed within the context of Rome’s imposition of price controls and the enforcement of regulations via the Straordinari di carne, The Butchers Shop becomes a symbolic expression of the contempt that families such as the Canobbi’s had for the papacy and its political authority.

In the background of the painting is an old woman who is sometimes attributed to being the halberdier’s wife. In contrast to the noble stature of those who work in the shop, she is depicted with a furrowed face and pointed nose. WindFootnote 100 suggests that the proximity of her hand to a piece of meat (carne) has clear sexual overtones. Her inclusion in the painting, therefore, represents a further attempt to inject an element of erotic humor into the subject matter. Given the symbolism and meaning contained within other elements of the composition, such an explanation seems unlikely. Schneider,Footnote 101 for example, suggests that rather than pointing to the meat, the woman is attempting to steal it from the table. Such an interpretation would reinforce the overall theme of the painting and allow the viewer to compare the honesty and integrity of guild members with the unscrupulous nature of those who relied upon the meat trade.

Conclusion

Pictorial narratives represent a widely available, yet relatively underutilized information source that can offer new insights into our cultural and business history. Although not all sixteenth-century works of art sought to convey meaning, the legitimacy of this form of expression meant that paintings represented a credible and authoritative channel of communication. At the same time, deconstructing visual imagery is recognized as being subjective, intuitive, and unscientific. Multiple interpretations of the same work remain possible, and the danger exists of simply assigning meaning based upon the recognition of various signs, symbols, and literary keys. The interpretation of The Butchers Shop put forward in this paper is, therefore, not something necessarily derived from agreement, and the cues provided by the artist can lead to alternative explanations of Carracci’s work.

Although some commentators have maintained that The Butchers Shop functions as a religious metaphor or an example of erotic Renaissance humor,Footnote 102 this paper places the composition within the context of Bologna’s political landscape. While accepting that it cannot be unequivocally proven, it suggests that Carracci’s work represents a commentary upon the socioeconomic tensions that underlaid civic life in sixteenth-century Italy. The symbols of professional conduct and personal reassurance, the linking to sacred characters, and the departure from traditional depictions of work, all arguably promote the legitimacy of the guild system and the reputation of the butchery profession. Moreover, the implicit narrative of Carracci’s composition may be interpreted as an advocation of institutional hegemony and trade protectionism.

It has, however, been suggested that Carracci’s work extends beyond an attempt to locate butchery among the most noble metiers and the attainment of summum bonum. The commissioning of The Butchers Shop is illustrative of the contribution artistic works could play in helping to establish an individual’s position within the prevailing social hierarchy. For those who could afford private commissions, the acceptance of genre art as a compositional form not only provided an opportunity to construct reality;Footnote 103 it offered societal prominence as well as political and economic legitimacy. If, as suggested in this paper, the painting sought to openly and transparently denounce Rome’s interference in Bologna’s civic and commercial activities, the status and reputation of its patron would have been significantly reinforced. By being able to contrast the inept and dishonest against the skilled and proficient, Annibale Carracci’s The Butchers Shop could be considered an example of reputation management as well as a form of sixteenth-century political propaganda.