Recent developments have prompted debate about potential threats to the stable functioning of democratic institutions within Western societies. These include the rise and governance of Donald Trump in the United States, electoral accomplishments of populist radical right parties in Europe, Brexit, small but detectable declines in democratic institutional functioning in Europe and North America, partisan and ideological polarization, and the failure of Western democracies to abate autocratic developments in other countries (e.g., Alexander and Welzel Reference Alexander and Welzel2017; Carey et al. Reference Carey, Helmke, Nyhan, Sanders and Stokes2019; Foa and Mounk Reference Foa and Mounk2017; Freedom House 2019; Gidron and Ziblatt Reference Gidron and Ziblatt2019; Levitsky and Ziblatt, Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018; Lührmann et al. Reference Lührmann, Gastaldi, Grahn, Lindberg, Maxwell, Mechkova, Morgan, Stepanova and Pillai2019; Miller and Davis Reference Miller and Davis2018; Norris Reference Norris2017; Plattner Reference Plattner2017). To this list one may now add the severe disruptions and hardship caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

How great is the risk of substantial democratic decline in the West? A key consideration in addressing this question is the mass orientation toward democracy within Western general publics. Political scientists have traditionally assumed that mass support for democracy and unconditional rejection of authoritarian alternatives can insulate democratic institutions against threatening crises (e.g., Easton Reference Easton1965; Linz and Stepan Reference Linz and Stepan1996; Plattner Reference Plattner2019). Indeed, recent evidence suggests that aggregate support for democracy predicts subsequent changes in democratic functioning (Claassen Reference Claassen2019). In this regard it is concerning that non-trivial segments of Western populations are amenable to authoritarian practices, lack a firm commitment to democratic institutions and norms, or endorse a notion of “democracy” that is fundamentally illiberal (Inglehart Reference Inglehart2003; Kirsch and Welzel Reference Kirsch and Welzel2019; Miller Reference Miller2017; Sullivan, Piereson, and Marcus Reference Sullivan, Piereson and Marcus1982). Furthermore, if undemocratic Western citizens share a particular ideological worldview, strategic elites who endorse this worldview can assemble sizable coalitions that would accept authoritarian measures to achieve common ideological goals.

With this in mind, the present research addresses the ideological make-up of citizens who would be most inclined to “green-light” authoritarian actions within the consolidated Western democracies. Using World Values Survey data from fourteen Western democracies between 1995 and 2014, as well as recent Latin American Public Opinion Project data from three national samples from Canada (2017) and the United States (2017 and 2019), we obtain two key findings. The first is that a broad conservative cultural orientation—involving traditional sexual morality and gender views, religiosity, anti-immigration attitudes, and related beliefs and values—is consistently associated with openness to authoritarian governance. On average, this association is stronger than those between democracy attitudes and college education, age, and political engagement. Moreover, it is present across different operationalizations of cultural conservatism and democracy attitudes. This finding suggests that authoritarian governance may be perceived as an efficient way of enforcing social conformity, upholding religious traditionalism, and resisting multi-cultural diversity (e.g., Adorno et al. Reference Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson, Sanford, Aron, Levinson and Morrow1950; Altemeyer Reference Altemeyer1996; Miller and Davis Reference Miller and Davis2018; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019; Welzel Reference Welzel2013).

The second key finding, however, suggests that left-wing economic views are in many cases a part of the ideological package that most strongly resonates with openness to authoritarian governance. Specifically, the combination of right-wing cultural and left-wing economic attitudes—what has been dubbed a “protection-based” attitude package (Malka, Lelkes, and Soto Reference Malka, Lelkes and Soto2019; see Johnston, Lavine, and Federico Reference Johnston, Lavine and Federico2017) was associated with higher levels of openness to authoritarian governance than was any other attitude package in half of the nations represented in the samples, including all five of the English-speaking democracies studied (Australia, Canada, Great Britain, New Zealand, and the United States). In most of the other Western democracies, protection-based and consistently right-wing attitude packages were associated with similarly high levels of openness to authoritarian governance. Overall, then, the protection-based attitude package most consistently accompanied amenability to authoritarian governance. We reason that this attitude package, sometimes described as “populist right” or “left authoritarian,”Footnote 1 reflects a prioritization of social order and economic stability, which, in the minds of citizens, may be satisfied by leadership and policy action that are unconstrained by democratic rules. We discuss implications for radical right populism and the prospect of splitting potentially undemocratic mass coalitions along economic lines.

Attitudes Toward Democracy and Why They Matter

Over the last three decades, cross-national survey projects have assessed a range of democracy-relevant attitudes and beliefs among mass publics. Though such measures have mainly been of interest to scholars studying transitioning democracies (e.g., Miller Reference Miller2017; Qi and Shin Reference Qi and Shin2011), recent developments suggest that attention should be devoted to such attitudes within established democracies as well (e.g., Drutman, Diamond, and Goldman Reference Drutman, Diamond and Goldman2018; Miller and Davis Reference Miller and Davis2018; Norris Reference Norris2017; Voeten Reference Voeten2017).

When classifying measures of democracy-related attitudes, it is important to distinguish between specific and diffuse support (Easton Reference Easton1965). Specific support for democracy refers to satisfaction with how democracy is working in one’s country. Although low specific support may be concerning (e.g., Sarsfield and Echegaray Reference Sarsfield and Echegaray2006), it might also serve as a mechanism through which citizens hold leaders accountable and incentivize democratization (e.g., Qi and Shin Reference Qi and Shin2011).

Diffuse support, on the other hand, is represented by a family of indicators that reflect committed support for a democratic system of government. This includes items gauging abstract support for a democratic regime, support for democratic institutions and norms (such as free press and separation of powers), rejection of authoritarian forms of government, and rejection of actions that degrade democratic norms and institutions. When measuring diffuse support, it is advantageous to include items gauging amenability to authoritarian actions under circumstances when such actions might be compelling. This is because some citizens who profess support for “democracy” also express support for authoritarian actions or endorse an illiberal definition of democracy (e.g., Bratton Reference Bratton2010; Dalton Reference Dalton1994; Kiewiet de Jonge Reference de Jonge and Chad2016; Kirsch and Welzel Reference Kirsch and Welzel2019; Schedler and Sarsfield Reference Schedler and Sarsfield2007).

Scholars have argued that high societal levels of diffuse support lower the probability that social upheaval or economic crisis will result in a deterioration of democratic institutions (Easton Reference Easton1965; Linz and Stepan Reference Linz and Stepan1996). Empirical tests of this view have tended to be narrowly focused in terms of countries, time periods, and measures, and as a whole have produced mixed results (e.g., Fails and Pierce Reference Fails and Pierce2010; Hadenius and Teorell Reference Hadenius and Teorell2005; Welzel Reference Welzel2007). However, the most comprehensive analysis to date suggests that high nation-level diffuse support has predicted lower levels of democratic deterioration, especially within democratic countries (Claassen Reference Claassen2019).Footnote 2 Thus it is important to understand the nature of democracy support among citizens of the consolidated Western democracies.

Who Is Open to Authoritarian Governance?

If societal support for democracy matters, then the question of which groups are most flexible in that support matters as well. In terms of demographics, non-college educated and younger people are relatively open to authoritarian governance (Lipset Reference Lipset1959; Miller Reference Miller2017; Norris Reference Norris2017; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019; Voeten Reference Voeten2017). Beyond demographics, variables related to political disengagement and dissatisfaction with how democratic institutions are functioning tend to correlate with openness to authoritarian governance (Drutman, Diamond, and Goldman Reference Drutman, Diamond and Goldman2018; Kiewiet de Jonge Reference de Jonge and Chad2016; Miller and Davis Reference Miller and Davis2018; Sarsfield and Echegaray Reference Sarsfield and Echegaray2006).

The Role of Ideological Attitudes

As many have argued, it is particularly important to understand the ideological and attitudinal correlates of democracy support (e.g., Adorno et al. Reference Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson, Sanford, Aron, Levinson and Morrow1950; Alexander and Welzel Reference Alexander and Welzel2017; Miller and Davis Reference Miller and Davis2018; Sullivan, Piereson, and Marcus Reference Sullivan, Piereson and Marcus1982). When a Western citizen approves a particular undemocratic action, it stands to reason that this action is often supported as a perceived means to an ideological end. The desired end could be something traditionally associated with the political right—such as realizing an ethno-nationalist vision of the country—or something traditionally associated with the political left – such as substantially increasing redistribution. Indeed, the desired end may involve both of these (e.g., Lefkofridi and Michel Reference Lefkofridi, Michel, Banting and Kymlicka2017; Oliver and Rahn Reference Oliver and Rahn2016).

The rigidity-of-the-right

The most influential perspectives on ideology and democracy attitudes are those tied to the classic “rigidity-of-the-right” model (Adorno et al. Reference Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson, Sanford, Aron, Levinson and Morrow1950; Altemeyer Reference Altemeyer1996). According to this view, people with a right-wing ideology possess strong needs for order, structure, security, and conformity, and tend to be open to authoritarian actions that can succeed in enforcing conformity, minimizing dissent and heterogeneity, and taking swift, decisive action to deal with national problems. This type of viewpoint ties democracy attitudes to the perennial political tradeoff between order and freedom. Those on the right are said to prioritize order and stability over freedom and self-direction, and, as a result, to be open to authoritarian governance.

However, a close look at the literature reveals that ideological differences in needs for security and certainty really apply to the cultural—rather than economic—aspects of conservatism (Duckitt and Sibley Reference Duckitt and Sibley2009; Federico and Malka Reference Federico and Malka2018; Malka and Soto Reference Malka and Soto2015). And, consistent with this, measures that prominently include culturally conservative content have been positively associated with openness to authoritarian governance (Alexander and Welzel Reference Alexander and Welzel2017; Ben-Nun Bloom and Arikan Reference Ben-Nun Bloom and Arikan2013; Canetti-Nisim Reference Canetti-Nisim2004; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019; Sullivan et al. Reference Sullivan, Piereson and Marcus1982; Welzel Reference Welzel2013). Cultural conservatives who conceive of the nation in racially, linguistically, or religiously exclusive terms (i.e., nativists) might naturally find threatening aspects of democracy that permit all individuals to try to gain access to power (Drutman, Diamond, and Goldman Reference Drutman, Diamond and Goldman2018; Miller and Davis Reference Miller and Davis2018). Moreover, cultural conservatism is associated with cognitive styles and dispositions that favor order, structure, simplicity, and certainty (Jost et al. Reference Jost, Glaser, Kruglanski and Sulloway2003; Schoonvelde et al. Reference Schoonvelde, Brosius, Schumacher and Bakker2019; Stenner Reference Stenner2005; Zmigrod, Rentfrow, and Robbins Reference Zmigrod, Rentfrow and Robbins2018), as well as low education (e.g., Lipset Reference Lipset1959) and low cognitive ability (e.g., Carl Reference Carl2014), which may yield non-democratic preferences.

Having said this, it is also plausible that any consistent relationship between cultural conservatism and democracy support is outweighed by the effect of who is in power and what they intend to do (e.g., Drutman, Diamond, and Goldman Reference Drutman, Diamond and Goldman2018). Indeed, those on the left and the right display roughly equal levels of out-group animosity overall—they simply reserve their animosity for different types of groups (Brandt and Crawford Reference Brandt and Crawford2020). It would be reasonable to suspect that cultural conservatives are generally no more willing to subvert democracy than are cultural liberals; rather, whichever ideological group is in power will support undemocratic action that allows its leadership to pursue desired policy action without constraints.

In sum, while there are reasons to expect that cultural conservatives will be more open to authoritarian governance than cultural liberals, it is also plausible that the link between cultural attitudes and democracy support will not be consistent. Thus, the first goal of our research is to evaluate the consistency of the link between cultural attitudes and openness to authoritarian governance across Western democracies.

The role of the protection-based attitude package

The traditional rigidity-of-the-right perspective implies that right-wing economic attitudes fuse naturally with right-wing cultural attitudes (e.g., Azevedo et al. Reference Azevedo, Jost, Rothmund and Sterling2019) and that these form a constellation of views that accompany attraction to authoritarian government (Adorno et al. Reference Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson, Sanford, Aron, Levinson and Morrow1950). Indeed, preference for inequality in the economic domain might naturally resonate with preference for social and political inequality (e.g., Jost et al. Reference Jost, Glaser, Kruglanski and Sulloway2003). And in some contexts, values of democracy and capitalism may conflict, as underscored by the historical associations between democracy and redistributive desires (McCloskey and Zaller Reference McClosky and Zaller1984).

However, there are reasons to expect that left economic attitudes might be a part of an ideological package that coheres with anti-democratic sentiment. Communism, after all, combined authoritarian governance with a radically egalitarian ideology, an attitude combination that still prevails among citizens who lived through Communism for substantial parts of their lives (Pop-Eleches and Tucker Reference Pop-Eleches and Tucker2019).Footnote 3 On theoretical grounds one could argue for a resonance between authoritarian governance and an economically interventionist state, as the latter may be facilitated by decisive and unimpeded executive action. Consider the aforementioned trade-off between social order and autonomy. While cultural conservatism would likely align with the “order” position on this tradeoff, so, seemingly, would economic preferences that prioritize protection and stability over freedom (Johnston, Lavine, and Federicio Reference Johnston, Lavine and Federico2017).

Indeed, over half a century ago Lipset (Reference Lipset1959) reviewed evidence that individuals with low education and status were inclined to both support redistributive economic policy and to adopt a range of conservative cultural positions, some of which were inherently undemocratic (e.g., opposition to civil rights for racial minorities). Lipset (Reference Lipset1959) argued that the appeal of Communist parties among these “working class authoritarians” reflected their combination of far-left economics and their authoritarian inclinations. As it turns out, recent evidence suggests that citizens who combine a culturally conservative worldview with an economically redistributive and interventionist set of preferences often place high priority on security, certainty, and stability (Federico and Malka Reference Federico and Malka2018; Johnston, Lavine, and Federico Reference Johnston, Lavine and Federico2017; Johnston Reference Johnston2018; Malka, Lelkes, and Soto Reference Malka, Lelkes and Soto2019; Malka and Soto Reference Malka and Soto2015). These citizens seem to apply a mindset to the political domain that attracts them to policies that maintain cultural tradition and uniformity (social conservatism) and that also entail top-down provision of material security (left-wing economic views). This type of worldview has been referred to as a “protection-based” attitude package, because it involves strong government intervention to provide protection against cultural and economic sources of insecurity. Its opposite—a freedom-based package—combines left-wing cultural with right-wing economic views, reflecting acceptance of cultural and economic risk rooted in the value of freedom (Johnston, Lavine, and Federico Reference Johnston, Lavine and Federico2017).

To date, the question of whether Western citizens with a protection-based attitude package are especially open to authoritarian governance has not been tested systematically. However, some observations suggest that they might be. For one thing, increased support for populist radical right European parties—which are often flexible or antagonistic toward democratic norms (Mudde Reference Mudde2007)—often comes at the expense of white working class support for social democratic parties (Abou-Chadi and Wagner Reference Abou-Chadi and Wagner2019; Berman and Snegovaya Reference Berman and Snegovaya2019; Lefkofridi, Wagner, and Willmann Reference Lefkofridi, Wagner and Willmann2014). This is a demographic group that often supports exclusive immigration policy and economic intervention on the part of the state, and this attitude combination might also resonate with the democratically illiberal aspects of the far-right agenda. Other work suggests that populist radical right parties have greater electoral potential when a higher percentage of immigration opponents hold more redistributive economic views in a protection-based attitude package (Pardos-Prado Reference Pardos-Prado2015; see also Cochrane Reference Cochrane2013; Gidron and Ziblatt Reference Gidron and Ziblatt2019; Lefkofridi and Michel Reference Lefkofridi, Michel, Banting and Kymlicka2017; Webb and Bale Reference Webb and Bale2014). Jedinger and Burger (Reference Jedinger and Burger2019) found that economic protectionism—a part of traditional left-wing platforms—correlates positively with right wing authoritarianism (Altemeyer Reference Altemeyer1996), an individual difference that reflects cultural traditionalism and authoritarian intolerance. Carmines, Ensley, and Wagner (Reference Carmines, Ensley and Wagner2016) found that Republicans with a protection-based attitude package were the most likely to support Donald Trump during the 2016 primaries. More directly, Drutman, Diamond, and Goldman (Reference Drutman, Diamond and Goldman2018) found in a Reference Drutman2017 U.S. sample that citizens who combined cultural conservatism with left economic attitudes scored relatively high on two items gauging openness to authoritarian governance. However, it is unclear if this only applies to Americans in the Trump era (see Drutman Reference Drutman2017). Thus, our second goal is to evaluate whether a protection-based attitude package is a consistent predictor of openness to authoritarian governance within Western democracies.

Method

We examine the consistency with which a broad-based cultural conservatism is associated with openness to authoritarian governance among Western citizens, and the possibility that those cultural conservatives who also hold left economic attitudes are particularly non-democratic in orientation. We do so using two data sources that use different measures of political and democracy attitudes, enabling us to test whether the findings generalize across different operationalizations of the key constructs.

Data Sources

World Values Survey

The first data source consists of Waves 3 through 6 of the World Values Survey (WVS), fielded between 1995 and 2014. The WVS uses probability sampling to recruit representative national samples. For most countries, the sample frame includes individuals age 18 or older who reside in private households. Most respondents are interviewed face to face. Sampling and other methodological details vary somewhat across national samples, and more detailed methodological information can be found at www.worldvaluessurvey.org.

Following Voeten (Reference Voeten2017), we regard as consolidated Western democracies a total of twenty-one countries: the EU15 plus Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, and the United States. Fourteen of these countries were represented with at least one sample across the four waves: Australia, Canada, Finland, France, Germany, Great Britain (United Kingdom excluding Northern Ireland), Italy, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United States. We used data from thirty-three national samples spanning these fourteen countries and a total of 45,035 respondents. Table B-1 in the online appendix reports the sample sizes of each country in each wave.Footnote 4 For each of the fourteen consolidated Western democracies represented in WVS Waves 3–6 we pooled data across all available waves.

Latin American Public Opinion Project

The second data source consists of three recent surveys from the two Western democracies represented in the Latin American Public Opinion Project’s (LAPOP) AmericasBarometer, the United States, and Canada. Though the United States and Canada are a small and non-representative subset of Western democracies as a whole, they are important to study because each has recently declined in mass support for democracy (Claassen Reference Claassen2019) and because of the larger global influence of the United States. Most importantly, use of this data source enables us to examine our research questions with different measures of the key constructs, as described later.

A U.S. survey was fielded in May of 2017 (N=1,500) by YouGov Politmetrix, and a Canada Survey was fielded in March and April of 2017 (N = 1,511) by The Environics Institute. These surveys included a more extensive and heterogeneous set of items tapping openness to authoritarian governance than the WVS. In addition, a more recent U.S. survey was fielded in July of 2019 (N=1,500) by YouGov Polimetrix, though it contained only a subset of the democracy attitude items included in the 2017 surveys.Footnote 5 Due to variation in the items administered, we separately analyzed data from each LAPOP sample (U.S.-2017, Canada-2017, and U.S.-2019). Each of these LAPOP samples was drawn from a large pool of opt-in internet panelists using a procedure in which respondents were matched to a representative national sample on key attributes. Surveys were completed online. More detailed methodological information can be found at https://www.vanderbilt.edu/lapop/core-surveys.php.

Measures

All items were initially coded to range from 0.00 to 1.00, and multi-item composites were formed with these recoded variables. Full question wording for all WVS and LAPOP items are presented in part A of the online appendix.

Openness to authoritarian governance

In the WVS, openness to authoritarian governance was measured as a composite of three items querying respondents’ evaluations of different types of political systems (e.g., Ariely and Davidov Reference Ariely and Davidov2010; Miller Reference Miller2017). Respondents rated on a four-point scale how good or bad a way of governing their country each of the following would be: “Having a strong leader who does not have to bother with parliament and elections,” “Having the army rule,” and “Having a democratic political system.” The democracy item was reverse coded and the three responses were then averaged into a composite that was coded to range from 0 .00 to 1.00, with high scores meaning more openness to authoritarian governance (M = .20, SD = .19, Mr (mean inter-item correlation) = .30).Footnote 6

The LAPOP surveys contain multiple questions addressing openness to authoritarian governance that differ in key ways from the WVS items. Most importantly, some of these items assess willingness to subvert democratic institutions and norms under circumstances when doing so might be tempting, without invoking the term “democracy.” Given that a number of citizens simultaneously express support for “democracy” and willingness to degrade democracy when circumstances are difficult (Dalton Reference Dalton1994; Inglehart Reference Inglehart2003; Kiewiet de Jonge Reference de Jonge and Chad2016) or an illiberal interpretation of what “democracy” means (e.g., Alexander and Welzel Reference Alexander and Welzel2017; Bratton Reference Bratton2010; Kirsch and Welzel Reference Kirsch and Welzel2019), it is advantageous to include such questions in an openness to authoritarian governance composite.

A total of eight democracy attitude indicators were available in at least one of the LAPOP surveys. These were justifiability of a military coup when there is a lot of crime or corruption (only in the 2017 surveys), justifiability of the executive leader closing the national legislature (only in the 2017 surveys), the “Churchill item” asking if democracy is better than any other form of government (all three surveys), political intolerance (all three surveys), support of restrictions on free speech (only in the 2017 surveys), support of the Prime Minister limiting voice and vote of the opposition party (only in Canada-2017), belief about whether democracy is preferable to any other kind of government (only in Canada-2017), and justifiability of closing Congress or dissolving the Supreme Court (only in U.S.-2019). Thus, openness to authoritarian governance measures were formed by averaging across five indicators in the U.S.-2017 sample (M = .22, SD = .19, Mr = .19), seven indicators in the Canada-2017 sample (M = .28, SD = .20, Mr = .21), and three indicators in the U.S.-2019 sample (M = .27, SD = .21, Mr = .16). Additional information about the eight indicators is presented in part A-2 of the online appendix.

It is clear that the openness to authoritarian governance measures capture broad constructs that encompass both weak allegiance to the notion of democracy as well as support of particular autocratic ideas (e.g., rule by a strong leader, military coups, curtailing free speech). It is also clear that the measures vary in specific content across the WVS and the three LAPOP datasets, with the LAPOP measures including often under-sampled indicators of support for specific authoritarian actions under difficult circumstances. While we believe each of the measures described here is a face-valid representation of flexible commitment to democracy and willingness to go along with authoritarian alternatives, we make no claim that each measure captures the exact same construct within every nation and sample. However, we do believe that these measures capture relatively similar constructs with similar patterns of relationships with well-known correlates of democracy attitudes. Indeed, as displayed in table C-1 in the online appendix, the democracy attitude measures correlated negatively with college education and political engagement across all countries and datasets.

Cultural conservatism

Based on prior evidence that many aspects of cultural conservatism tend to converge on a broad individual difference construct (e.g., Bouchard Reference Bouchard, Voland and Schiefenhövel2009; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019; Saucier Reference Saucier2000; Stankov Reference Stankov2017; Wilson and Patterson Reference Wilson and Patterson1968), we computed a widely inclusive cultural conservatism measure with the WVS data. It includes indicators of socially traditional versus progressive policy preferences as well as a range of social attitudes, values, and beliefs shown in prior work to cohere with these policy preferences (e.g., Feldman Reference Feldman, Sears, Huddy and Jervis2003; Hetherington and Weiler Reference Hetherington and Weiler2009; Malka Reference Malka and Saroglou2013; Miller and Davis Reference Miller and Davis2018). A total of eighteen items were used, although the specific number of available items vary across countries and waves, as described in part A-1 of the online appendix. Items addressed traditional sexual morality, religiosity, opposition to immigration and multi-cultural diversity, strict child-rearing values, and rejection of gender equality. Thus, the construct captured by this measure represents a comprehensive traditional/conservative versus progressive/liberal orientation toward morality, culture, politics, social behavior, and religion. The measure was coded to range from 0.00 to 1.00, with higher scores meaning greater cultural traditionalism (M = .38, SD = .18, Mr = .18).

Far fewer items tapping cultural conservatism were available in the LAPOP surveys. Four-item scales were computed for the U.S.-2017 and Canada-2017 samples, consisting of items measuring agreement with the view that punishment of criminals should be increased, approval versus disapproval of same-sex marriage, religious attendance, and religious importance (U.S.-2017: M = .47, SD = .26, Mr = .34; Canada-2017: M = .40, SD = .21, Mr = .28). A three-item scale was computed in the U.S.-2019 sample, consisting of religious attendance, religious importance, and belief that men make better political leaders than women (M = .43, SD = .28, Mr = .37).

As with the openness to authoritarian governance measures, there is variation in the cultural conservatism measures across the survey projects, an advantage from the standpoint of testing multi-method robustness. The WVS measure is very broad in scope, while the LAPOP measures are narrower, have higher inter-item correlations, and have a greater concentration of religiosity content. As displayed in table C-2 in the online appendix, the measures of cultural conservatism were uncorrelated or negatively correlated with left economic attitudes, reliably negatively correlated with age, and, in fifteen of seventeen datasets, correlated with not having a college education.Footnote 7

Left economic attitudes

Within the WVS, a broad measure of economic attitudes was computed, which included economic policy preferences as well as content related to capitalist values (e.g., Guiso, Sapienza, and Zingales Reference Guiso, Sapienza and Zingales2003). The measure consisted of items querying opinion of government responsibility to reduce income inequality, government responsibility to provide for the welfare of citizens, preference for public vs. private business ownership, belief that competition is good, belief that hard work (rather than luck) matters most for success, and belief concerning the societal consequences of pursuing individual wealth. As described in part A-1 of the online appendix, the specific number of available items varied slightly across countries and waves. A left economic attitudes measure, coded to range from 0.00 to 1.00 with higher scores indicating preference for greater redistribution and less of a capitalist worldview, was computed (M = .42, SD = .15, Mr = .16).

Fewer economic attitude items were available in the LAPOP surveys. In the U.S.-2017 sample, the left economic attitudes measure was computed as an average of items gauging support versus opposition to government ownership of industry and government action to reduce income inequality (M = .41, SD = .28, r = .46). In Canada-2017, only the item asking about reduction of income inequality was available, so this was used as the left economic attitude measure (M = .71, SD = .25). Finally, in the U.S.-2019 sample, the left economic attitude measure was a composite of four items that gauged attitudes about reducing income inequality, support of more government spending to help the poor, support for high taxes on the rich, and disagreement that most unemployed people could find a job if they wanted one (M = .52, SD = .25, Mr = .43).

The left economic attitude measure in the WVS is broad in scope while the LAPOP measures are narrower and possess higher inter-item correlations. Evidence that these measures tap a roughly similar left versus right economic attitude construct across countries and datasets is displayed in table C-3 of the online appendix. As would be expected of valid measures of left economic attitudes, they correlate with low income across all datasets and low financial satisfaction across all WVS datasets (financial satisfaction was not available in the LAPOP datasets).

Control variables

In some of the WVS analyses, variables that are potentially predictive of democracy attitudes were used as controls. One was confidence in key democratic institutions of the respondent’s country computed as a composite of confidence in the government, the parliament, and the country’s political parties (M = .40, SD = .21, Mr = .64) (Qi and Shin Reference Qi and Shin2011). Another was political engagement (e.g., Norris Reference Norris2011), which was computed as a composite of self-rated interest in and personal importance ascribed to politics (M = .48, SD = .27, r = .63). Respondents also rated how satisfied they were with their households’ financial situations (M = .62, SD = .25). College education (M = .18, SD = .39), age (M = 46.5 years, SD = 17.5), female gender (M = .52, SD = .50), and household income decile (M = .46, SD = .28) were also recorded.

Some of the LAPOP analyses also involved control variables. First, a confidence in institutions variable was computed as a composite of self-rated trust in political parties, elections, Congress (Parliament), and (only in the 2017 surveys) local (municipal) government, in which higher scores mean greater trust (U.S.-2017: M = .43, SD = .21, Mr = .47; Canada-2017: M = .54, SD = .22, Mr = .63; U.S.-2019: M = .42, SD = .24, Mr = .54). Second, political engagement was a composite of self-rated interest in politics and frequency of following news (U.S.-2017: M = .77, SD = .25, r = .51; Canada-2017: M = .73, SD = .20, r = .35; U.S.-2019: M = .78, SD = .24, r = .48). Third, respondents rated their satisfaction with the way democracy works in their country (U.S.-2017: M = .49, SD = .25; Canada-2017: M = .62, SD = .21; U.S.-2019: M = .52, SD = .27). Finally, college education (U.S.: M = .26, SD = .44; Canada-2017: M = .28, SD = .45; U.S.-2019: M = .28, SD = .48), age (U.S.-2017: M = 47.5 years, SD = 17.5; Canada-2017: M = 47.3 years, SD = 15.7; U.S.-2019: M = 48.3 years, SD = 17.5), female gender (U.S.-2017: M = .52, SD = .50; Canada-2017: M = .52, SD = .50; U.S.-2019: M = .51, SD = .50), household income (median category selected was 3,601 - 4,400 USD per month in U.S.-2017, 60,000-69,999 CAD annually in Canada-2017, and 3,101 - 3,600 USD per month in U.S.-2019), and, only in the U.S. samples, dummy variables representing the effects of racial/ethnic group (with white as the comparison category) were also recorded.

Analysis Strategy

For the main analyses, four OLS regression models were tested within each of the fourteen WVS country datasets and each of the three LAPOP country-year datasets. In each model the dependent variable was openness to authoritarian governance. The first model included only the cultural conservatism and left economic attitudes measures, and the second model included these as well as their interaction. These models directly address the primary questions of this research: whether there are reliable differences in openness to authoritarian governance across citizens differing in cultural conservatism and across citizens with different combinations of cultural and economic attitudes. The third and fourth models were the same as the first and second, respectively, but with the inclusion of control variables. These models address whether any observed ideological differences in openness to authoritarian governance are present above and beyond differences in various background characteristics, such as college education and political engagement, that could relate to both ideology and democracy attitudes. However, it should be noted that non-demographic control variables such as political engagement and confidence in institutions might be endogenous to the ideological variables, and might constitute a part of the mechanism by which ideological variables influence democracy attitudes (e.g., Federico, Fisher, and Deason Reference Federico, Fisher and Deason2017; Hillen and Steiner Reference Hillen and Steiner2019).

All continuous predictor variables were mean-centered and scaled by two standard deviations (see Gelman Reference Gelman2008), with the interaction term formed by multiplying mean-centered and scaled variables. Binary predictor variables were coded 0 and 1, and the openness to authoritarian governance outcome variables retained their 0.00 to 1.00 coding. Thus, regression coefficients represent the predicted percentage point change in openness to authoritarian governance going from one SD below to one SD above the mean on continuous predictors and going from the low to the high value on binary predictors. Weights were applied in all analyses.

In both data sources, there was variation across the datasets in question availability, and there was missing data due to non-response. Tables B-2 and B-3 in the online appendix display the percentage of respondents in each WVS country dataset (table B-2) and each LAPOP country-year dataset (table B-3) with data for each item. Where the percentages are zero, the item was not administered and is not included in the relevant composite. Percentages with complete data rarely fell below 90, and were often close to 100, except in cases where the item was not administered at all, the item was not administered in all of a country’s WVS waves, or the item was household income.

For the main analyses, missing data were replaced separately within each of the fourteen WVS country datasets and each of the three LAPOP country-year datasets using multiple imputation carried out with the R packages “mice” (Van Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn Reference Van Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn2010) and “miceadds” (Robitzsch et al. Reference Robitzsch, Grund, Henke and Robitzsch2019). Using predictive mean matching (Rubin Reference Rubin1986) to impute missing values at the item level (see Gottschall, West, and Enders Reference Gottschall, West and Enders2012), we created twenty copies of each dataset with different sets of imputed item values in each copy (see Enders Reference Enders2010, 214-215). All items used in analyses were included in each dataset’s imputation phase, as were dummy variables for wave in the case of the WVS country datasets.Footnote 8 Multi-item scales were formed within these imputed datasets, and then regression analyses were conducted and their results pooled across the twenty copies of each dataset.

Results

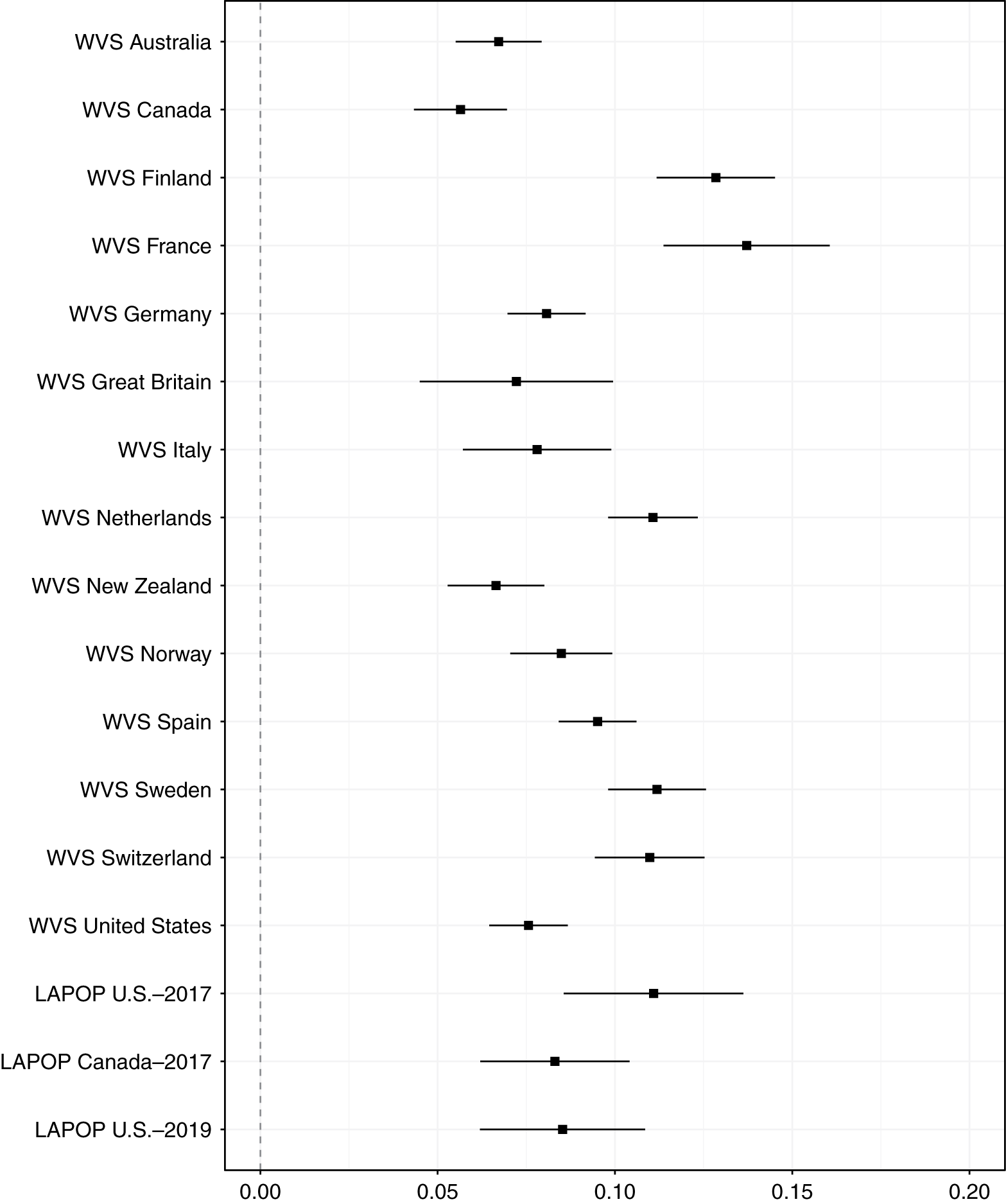

The full regression results for each dataset are displayed in part D of the online appendix (tables D-1 to D-17). Figure 1 displays the regression coefficients for cultural conservatism from Model 1 of each dataset. In each of the seventeen datasets there is a positive and statistically significant association between cultural conservatism and openness to authoritarian governance. In the first regression model (controlling only left economic attitudes), the coefficients ranged from .06 (WVS Canada) to .14 (WVS France) with a mean of .09. This suggests that going from one SD below to one SD above the mean on cultural conservatism is associated with a 6–14 percentage point increase in openness to authoritarian governance. Variation in the estimated association across datasets is likely due to some combination of sampling error, variation in actual effect sizes across countries and times, and variation in the precise constructs captured by the measures across countries. What is clear, though, is that citizens who are culturally conservative tend to be more open to authoritarian governance compared to citizens who are culturally progressive.

Figure 1 Effect of cultural conservatism on openness to authoritarian governance

As shown in tables D-1 though D-17 (Model 3) in the online appendix, these associations remained significantly positive when control variables were included, with the average coefficient remaining .09. These models with control variables show that cultural conservatism on average had the largest associations with openness to authoritarian governance, with its average coefficient exceeding in magnitude those of all other predictors, including the next strongest predictors of political engagement (average coefficient of –.06), college education (average coefficient of –.05), and age (average coefficient of –.04).

These findings provide strong support for the hypothesis that cultural conservatives are consistently more amenable to authoritarian actions than are cultural liberals within Western societies. This finding emerged in all countries and across two distinct operationalizations of the constructs.

Figure 2 displays the regression coefficients for left economic attitudes from Model 1 of each dataset. As displayed, left economic attitudes were more often positively associated than negatively associated with openness to authoritarian governance. Associations ranged from -.04 (LAPOP U.S.-2019) to .10 (WVS United States) with a mean of .02. Although the greatest negative association was observed in a U.S. LAPOP sample, left economic attitudes went with openness to authoritarian governance primarily within the English-speaking countries, with positive and statistically significant coefficients observed in WVS Australia, WVS Canada, WVS Great Britain, WVS New Zealand, WVS United States, and LAPOP U.S.-2017, as well as WVS Germany. Negative and statistically significant coefficients were observed in WVS Spain and LAPOP U.S.-2019. As displayed in Model 3 of figures D-1 – D-17 of the online appendix, when control variables were added, the significant positive coefficient for left economic attitudes dropped to non-significance in the case of WVS New Zealand and the negative coefficient in WVS Netherlands became significant.

Figure 2 Effect of left economic attitudes on openness to authoritarian governance

Comparing the effect sizes between cultural conservatism and left economic attitudes, we find that in almost all cases the effect sizes for the latter were far smaller. Overall the findings suggest that the link between right-wing positions and openness to authoritarian governance does not generally extend to the economic domain, and that the associations between economic and democracy attitudes are small, of varying sign across countries and measures, and perhaps slightly titled toward a left-authoritarian association within the English-speaking countries.

We next examined if, beyond the additive effects of cultural and economic orientations, the combination of holding right-wing cultural and left-wing economic views uniquely predicts openness to authoritarian governance. If this were so, one would expect positive cultural conservatism X left economic attitude interaction effects. If, on the other hand, a consistently right-wing attitude package resonates the most with openness to authoritarian governance, one would expect negative interaction effects.

Figure 3 displays the coefficients for the cultural conservatism X left economic attitudes interaction from Model 2 of each dataset (i.e., without control variables). As displayed, this interaction was significantly positive in nine out of seventeen datasets, and never significantly negative. Coefficients for the interaction ranged from –.03 (WVS Italy) to .13 (LAPOP U.S.-2019), with a mean of .04. What immediately stands out is that the interaction was significantly positive, indicating that cultural conservatism was more strongly linked with openness to authoritarian governance among those on the economic left compared to those on the economic right, in every dataset from an English-speaking country: WVS Australia, WVS Canada, WVS Great Britain, WVS New Zealand, WVS United States, LAPOP U.S.-2017, LAPOP Canada-2017, and LAPOP U.S.-2019. The interaction effect was also significantly positive in WVS Sweden. As displayed in Model 4 of tables D-1 to D-17 in the online appendix, when control variables were included, only the interaction effect in WVS Australia dropped to non-significance.Footnote 9

Figure 3 Effect of cultural conservatism x left economic attitude interaction on openness to authoritarian governance

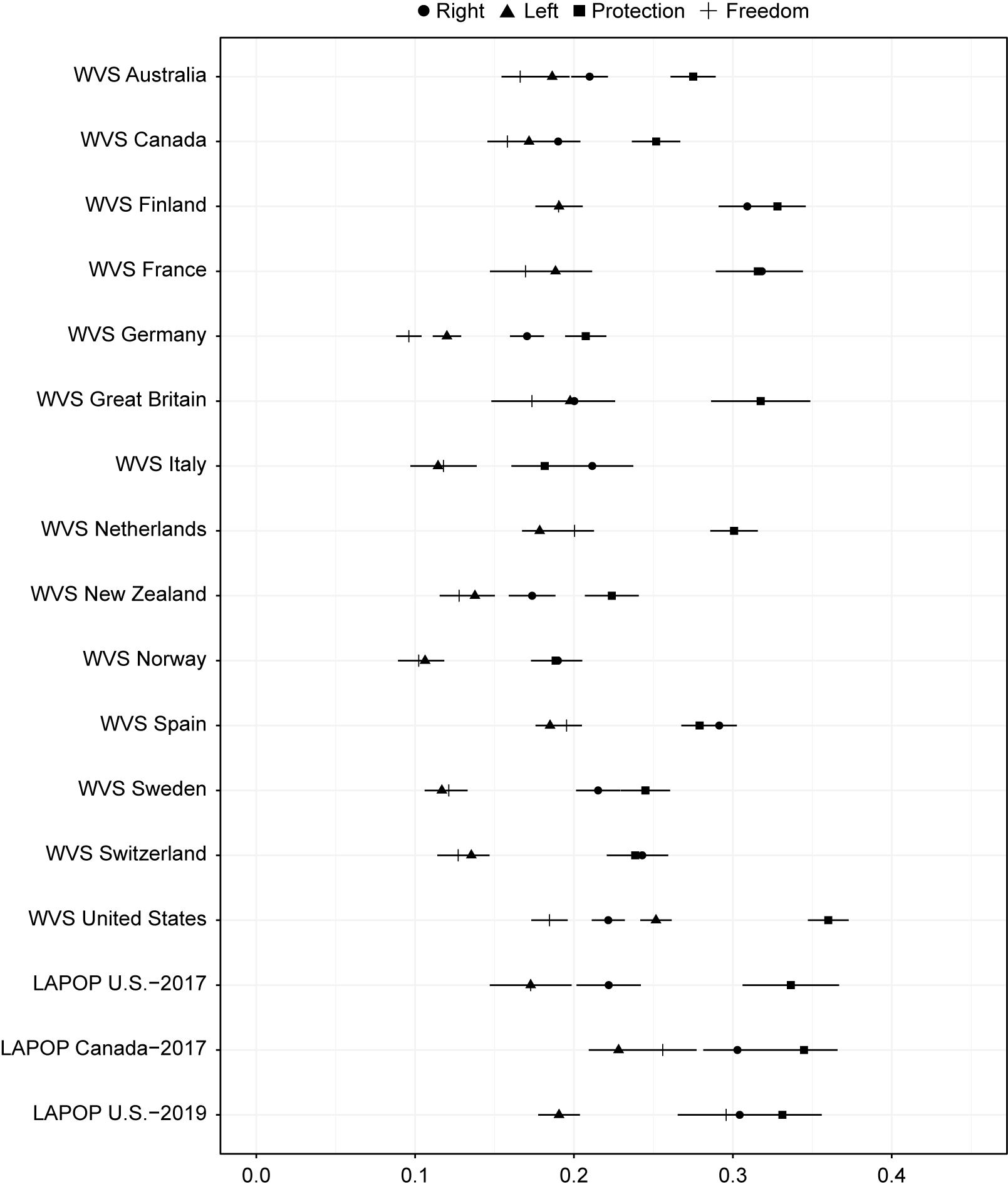

To interpret these interaction effects, we computed predicted values of openness to authoritarian governance for hypothetical individuals with right-wing, left-wing, protection-based, and freedom-based attitude packages, using regression equations from each dataset containing cultural conservatism, left economic attitudes, and their interaction (Model 2). Predicted values were computed based on all combinations of +/–1 SD from the mean on cultural conservatism and left economic attitudes (e.g., the right-wing package was +1 SD on cultural conservatism and –1 SD on left economic attitudes, the protection-based package was +1 SD on both, etc.). Predicted values of openness to authoritarian governance are displayed in figure 4.

Figure 4 Predicted values of openness to authoritarian governance

As displayed, it was primarily within English-speaking democracies that citizens with a protection-based attitude package were more open to authoritarian governance than were their fellow citizens with any of the other three attitude packages. Within WVS Australia, WVS Canada, WVS Great Britain, WVS New Zealand, WVS United States, LAPOP U.S.-2017, LAPOP Canada-2017, and LAPOP U.S.-2019, as well as WVS Germany, WVS Sweden, and, to a lesser extent, WVS Finland, protection-based citizens had the highest estimates of openness to authoritarian governance. In WVS Italy and, to a lesser extent, WVS Spain, those with consistently right-wing attitude packages were more open to authoritarian governance than those with protection-based attitude packages. In the remaining countries, protection-based and consistently right-wing attitude packages tended to be associated with approximately equal levels of openness to authoritarian governance, while citizens with consistently left-wing and freedom-based attitude packages tended to be the most democratic.

Overall, these findings suggest that, out of the four attitude packages, the protection-based package most consistently coheres with support of authoritarian actions among Western citizens. Its greater link with undemocratic sentiment than the right-wing package, however, seems to occur primarily in the English-speaking Western democracies. Where the protection-based package is not singularly associated with the highest degree of anti-democratic sentiment, it tends to be tied with the consistently right-wing package in this regard.

Robustness Checks

We conducted two additional sets of analyses to test whether findings are robust to alternative measurement and analytic strategies. Because our main goal is to describe ideological associations with democracy attitudes, and because results did not differ meaningfully across models with and without control variables, we excluded the control variables from these analyses. Results are reported in part E of the online appendix.

First, we repeated the WVS country analyses (Models 1 and 2) using a four-item openness to authoritarian governance measure which includes the “experts decide” item (see n. 6). Results of these analyses did not differ substantively from those of the main analyses (refer to figures E-1 through E-4 of the online appendix).

Second, we repeated analyses from all datasets (Models 1 and 2) without imputing missing data, and instead forming scale scores by averaging across all available items for each respondent and excluding respondents with missing scale scores listwise. Results of these analyses did not differ substantively from those of the main analyses (refer to figures E-5 through E-8 of the online appendix).

Discussion

Much debate has focused on the degree and nature of the risk that the world’s established democracies will become substantially less democratic in the not too distant future. An important consideration in this debate is the nature of democracy attitudes among Western citizens. Survey evidence suggests that non-trivial numbers of Western citizens would welcome or at least be untroubled by autocratic developments. The presence of such citizens will not, of course, upend entrenched democratic institutions overnight. But it can influence the incentives of elites to take (or accept) actions that would serve to gradually erode democracy (e.g., Claassen Reference Claassen2019; Inglehart and Welzel Reference Inglehart and Welzel2005; Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018; Qi and Shin Reference Qi and Shin2011). Importantly, to the degree that particular ideological leanings characterize this group, aspiring Western elites who lack qualms about eroding democracy can attract a respectably sized constituency for using non-democratic means to achieve specific ideological ends.

What type of Western citizens would be most inclined to support democracy-degrading actions? The present findings provide two insights into this question. The first is that Westerners with a broad culturally conservative worldview are especially open to authoritarian governance. For what is likely a variety of reasons, a worldview encompassing traditional sexual morality, religiosity, traditional gender roles, and resistance to multicultural diversity is associated with low or flexible commitment to democracy and amenability to authoritarian alternatives. This association tends to be larger than those of commonly studied correlates of support for authoritarian governance, such as political engagement, college education, and age. It is reliably present across Western democracies, and across two data sources that differ in their measurement of cultural conservatism and democracy attitudes.

It would be reasonable to suspect that whether cultural conservatives or cultural liberals are more open to authoritarian actions would depend on whether authoritarian proposals are coming from culturally conservative or culturally liberal elites, and what aims these proposals are directed toward. While there is likely truth to this, the present findings suggest a consistent ideological asymmetry between cultural liberals and cultural conservatives in preference for authoritarian governance. Considering the LAPOP data, the associations were present in both the United States, where conservative elites had control of the national government, and Canada, where a left-leaning government presided. Thus, it would appear that aspiring authoritarian elites who wish to go “hunting where the ducks are” are best off catering their appeals to cultural conservatives. This finding also lends credence to the strategies employed by Vladimir Putin, Victor Orban, and others to seek the weakening of Western democratic institutions through appeals to cultural conservatives (e.g., Plattner Reference Plattner2019).

The second insight is that Westerners who hold a protection-based attitude package—combining a conservative cultural orientation with redistributive and interventionist economic views—are often the most open to authoritarian governance. Notably, it was the English-speaking democracies where this combination of attitudes most consistently predicted openness to authoritarian governance. In most of the remaining countries, those with protection-based and consistently right-wing attitude packages were about equally open to authoritarian governance.

It is worth considering this finding in the context of potential threats to Western democracy stemming from radical right populism (Alexander and Welzel Reference Alexander and Welzel2017; Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Ziblatt2017; Mudde Reference Mudde2007; Norris Reference Norris2017; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019; Plattner Reference Plattner2017, Reference Plattner2019). Sometimes described as “far right” or “radical right”, this typically refers to an ideological worldview that combines cultural conservatism with rhetoric that a corrupt elite is exerting power for self-serving means at the expense of the morally upright “people.” This worldview is represented by populist radical right parties and politicians whose main emphases are ethno-nationalism, strident opposition to immigration, traditional sexual morality, law and order, and disparagement of mainstream political actors and norms (Lefkofridi and Michel Reference Lefkofridi, Michel, Banting and Kymlicka2017; Mudde Reference Mudde2007; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019). Radical right populism seems to fuse organically with openness to authoritarian governance, as it involves denigration of institutions that democratically constrain the country’s leadership (such as the media and the justice system) and a hostile posture toward legal protections for disfavored groups (Norris Reference Norris2017; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019).

Conservative cultural views pertaining to immigration, sexual morality, law and order, and ethno-nationalism have been far more central to the populist radical right worldview than economic attitudes (Lefkofridi and Michel Reference Lefkofridi, Michel, Banting and Kymlicka2017; Mudde Reference Mudde2007). However, since the mid-1990s, there appears to have been a leftward shift in many—though certainly not all—populist radical right parties’ economic rhetoric (Afonso and Rennwald Reference Afonso, Rennwald, Manow, Palier and Schwander2018; Derks Reference Derks2006; Fenger Reference Fenger2018; Lefkofridi and Michel Reference Lefkofridi, Michel, Banting and Kymlicka2017; Michel Reference Michel2017). This might be understood as recognition that parts of the traditional center-left and center-right mass coalitions support economic intervention while holding nativist and traditional cultural views (Hillen and Steiner Reference Hillen and Steiner2019; Van der Brug and Van Spanje Reference Van der Brug and Spanje2009; Lefkofridi, Wagner, and Willmann Reference Lefkofridi, Wagner and Willmann2014; Berman and Snegovaya Reference Berman and Snegovaya2019; Webb and Bale Reference Webb and Bale2014; Gidron and Ziblatt Reference Gidron and Ziblatt2019; Carmines, Ensley, and Wagner Reference Carmines, Ensley and Wagner2016; Oliver and Rahn Reference Oliver and Rahn2016). One way of integrating this combination of stances is through “welfare chauvinism”: reserving social welfare benefits and economic protection for the “real” members of the nation who are said to have suffered from elites who are more interested in directing their solicitude toward immigrants (Gidron Reference Gidron2016; Lefkofridi and Michel Reference Lefkofridi, Michel, Banting and Kymlicka2017; Schumacher and Van Kersbergen Reference Schumacher and van Kersbergen2016).

Indeed, the present findings suggest that—especially within the Anglophone democracies—the types of citizens who would be most receptive to these appeals will also be relatively inclined toward anti-democratic sentiment. This raises the uncomfortable question of whether being more blunt in their anti-democratic sentiment would constitute an electoral liability or advantage for populist radical right politicians seeking to gain more support from culturally conservative but economically left-leaning citizens. But these findings also provide insight into how those who would support undemocratic actions might be split along economic lines. The two ideological groups that are most open to authoritarian governance are those with protection-based and consistently conservative attitudes. As it turns out, populist radical right parties have attracted not only white working-class individuals inclined to favor redistributive policy, but also culturally aggrieved small business owners who are often on the economic right (Lefkofridi and Michel Reference Lefkofridi, Michel, Banting and Kymlicka2017). This has incentivized some degree of “position blurring” in order to thread this needle and appeal to each constituency without alienating the other (Rovny Reference Rovny2013). The present findings reinforce suggestions that if social democratic parties offered a more coherent economic alternative to the Western neo-liberal consensus and de-emphasized their progressive cultural stances, they could peel away some protection-based voters and split the constituency for non-democratic action along economic lines (Berman and Snegovaya Reference Berman and Snegovaya2019). However, it is unclear if the overall electoral gains from this would exceed the costs (Abou-Chadi and Wagner Reference Abou-Chadi and Wagner2019; Gidron Reference Gidron2016).

We must note that we did not expect or predict that citizens of the Anglophone democracies would display the strongest link between the protection-based attitude package and openness to authoritarian governance. We can only speculate as to the reasons for this. One possibility is that citizens of Anglophone democracies are more likely to associate free market economics with political freedom and democratic liberalism, based on an intuitive classical liberalism (Hartz Reference Hartz1955). Central to classical liberalism is a focus on individualism. As it turns out, citizens of English-speaking countries tend to score higher than citizens of other countries in self-report measures of individualism, which tap a focus on personal as opposed to collective goals, individual autonomy, self-differentiation, and competition (Oyserman, Coon, and Kemmelmeier Reference Oyserman, Coon and Kemmelmeier2002; Triandis Reference Triandis1993). It might be the case that in Anglophone democracies more so than other democracies, consistent support for procedural democratic rules is linked with a classically liberal mindset focused on individual autonomy to pursue economic interests and cultural preferences without government interference. Within such societies, those citizens most inclined to reject this ethos may be especially open to authoritarian governance. But whether this finding proves reliable and explanations for it are left as a matter for future research.

The present research tested theoretically derived hypotheses about an important social matter using a large number of samples spanning fourteen countries and two survey projects that vary in measures of the key constructs. But there are caveats and limitations to this work that we wish to make explicit.

First, although we found ideological differences in openness to authoritarian governance, predicted values of openness to authoritarian governance among the most non-democratic ideological groups were still below the scale midpoint. A hopeful way of viewing this finding is that even the least democratically committed ideological groups still tend toward support for democracy. However, we remind readers that the absolute position on the scale must be considered in the context of social desirability bias, misdefinitions of democracy in illiberal terms, and support of “democracy” in the abstract only (Alexander and Welzel Reference Alexander and Welzel2017; Bratton Reference Bratton2010; Kiewiet de Jonge Reference de Jonge and Chad2016; Schedler and Sarsfield Reference Schedler and Sarsfield2007)—all of which are likely to push the mean toward the democratic end of the continuum. That predicted values of openness to authoritarian governance for the least democratic groups were below the scale midpoint does not necessarily undermine the conclusion that these groups would find authoritarian actions appealing.

Second, causal direction is unclear because the present datasets are non-experimental and cross-sectional. It could well be the case, for example, that unmodelled individual attributes cause both ideological and democracy attitudes. Top candidates for such unmodelled individual attributes are cognitive abilities and styles that pertain to simple, unreflective black-and-white reasoning (e.g., Arceneaux and Vander Wielen Reference Arceneaux and Wielen2017; Zmigrod, Rentfrow, and Robbins Reference Zmigrod, Rentfrow and Robbins2018). Such thinking styles might lead people to conceive of societal problems in tangible and straightforward terms and attract people to direct and simple solutions (Adorno et al. Reference Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson, Sanford, Aron, Levinson and Morrow1950; Lipset Reference Lipset1959). Prior work suggests that such tendencies might relate to cultural traditionalism, the protection-based attitude package, and openness to authoritarian governance (Carl Reference Carl2014; Johnston, Lavine, and Federico Reference Johnston, Lavine and Federico2017). Specifically, simplistic thinking might yield feelings of threat in response to the culturally unfamiliar (without considering the benefits of multicultural diversity or the drawbacks of cultural intolerance), a desire to handle economic problems with straightforward ameliorative government action (without considering implications for incentives, economic growth, and budget deficits), and a desire for decisive leadership whose action is not constrained by procedural rules (without considering the long-term value of consistently applied procedural rules). These cognitive abilities and styles are unlikely to have been adequately captured by the present covariates, such as college education and political engagement. We must note, however, that our main interest was to describe which ideological groups are most open to authoritarian governance. Conclusions about this specific matter do not depend on whether relationships are driven by unmodelled individual differences or reflect causal influence between ideology and democracy attitudes. Indeed, it might make the most sense to consider democracy attitudes as part of particular ideological packages that include traditionally studied political attitudes (e.g., Bouchard Reference Bouchard, Voland and Schiefenhövel2009; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019). Nonetheless, longitudinal and experimental data would be useful for identifying the causal influences underlying the present patterns.

Finally, it is possible that the present findings represent measurement artifacts associated with the particular ideological and democracy attitude measures drawn from the WVS and LAPOP measures. That the measures varied quite a bit across the two data sources is encouraging. However, whether or not these findings emerge using other measures of the key constructs is an important matter for future investigation.

Conclusion

There are legitimate concerns about the health of democracy within Western societies (e.g., Freedom House 2019; Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018; Lührmann et al. Reference Lührmann, Gastaldi, Grahn, Lindberg, Maxwell, Mechkova, Morgan, Stepanova and Pillai2019). Given the evidence that mass attitudes toward democracy can influence democratic functioning (Claassen Reference Claassen2019), understanding openness to authoritarian governance among Western citizens is an important goal. Individuals on both the left and the right may be vulnerable to antidemocratic appeals, but the present findings suggest that cultural conservatives in the West are consistently more open to authoritarian governance than are their culturally liberal counterparts, and in several democracies this is especially the case when their cultural conservatism is combined with left-leaning economic attitudes.

The durability of Western democracy may depend in part on the ability of mainstream left and right parties (or moderate factions within them) to attract those Westerners who are most open to authoritarian governance. These types of parties have played important roles in preserving Western democracy, the former by providing a democratically committed outlet to citizens unhappy with the outcomes of a capitalist economy (e.g., Berman Reference Berman2006; Berman and Snegovaya Reference Berman and Snegovaya2019) and the latter by promoting stability and compromise while containing right-wing ethno-nationalism (Gidron and Ziblatt Reference Gidron and Ziblatt2019; Ziblatt Reference Ziblatt2017). To the extent that these parties can split the culturally conservative vote along economic lines, the prospects for liberal democracy could well be improved.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592720002091.