On March 11, 2014, the Brazilian embassy and the China-based People’s Literature Publishing House held a special workshop on Brazilian literature at Peking University to celebrate the publication of the Chinese translation of Brazilian writer Cristovão Tezza’s novel Eternal Son [O Filho Eterno, 2007). This workshop brought Tezza in dialogue with some Chinese writers and scholars about the connections between Chinese and Brazilian literature. After Tezza briefly introduced the literary tradition of realism and modernism in Brazil, rather than expressing their interest in Brazilian literary tradition, Chinese writers responded by talking about their reading experience of the Colombian novelist Gabriel García Márquez and magical realism.Footnote 1

The Chinese writers’ lack of knowledge of Brazilian literary tradition, and their diversion of the topic of discussion with Tezza to a Colombian author, prompt inquiries into at least three main issues. The discussion is indicative not only of a broader lack of cultural identification among cultural intellectuals in the global south that is overshadowed by the prominent economic integration of the BRICS, but also suggests the fact that Brazilian literature can gain its significance in China only as part of “Latin America,” of which Brazil is the unique Portuguese-speaking country. Moreover, the Chinese writers’ frequent reference to “magical realism,” a phrase that, taken to define the native character of Spanish American fiction that has circulated globally, is not a matter of meaningless coincidence but rather a mirror of its predominant hold over the Chinese imagination of Latin America. Since it was introduced to China after García Márquez won the Nobel Prize in 1982, the phrase has repeatedly appeared in Chinese mass media and academic works. The sensational response of Chinese media and audience to Peruvian writer Vargas Llosa’s winning of the Nobel Prize in 2010 demonstrates the continuing influence and draw of magical realism in China.Footnote 2 Similarly, when the Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to Chinese writer Mo Yan in 2012 for his work as a writer “who with hallucinatory realism merges folk tales, history and the contemporary,” most Chinese media translated the phrase “hallucinatory realism” directly to “magical realism.” Such mistranslation, whether intentional or not, effectively fashioned a new trend of nostalgia for Latin American literature in China after thirty years.Footnote 3 The nostalgic power of magical realism explains why this topic came up at the center of the dialogue between Brazilian and Chinese literature. For decades magical realism has rendered Brazilian literature invisible and supplementary to the continuously glamorous boom writers.

It is not enough, however, to stress the invisibility of Brazilian literature in China simply by blaming magical realism or Spanish American literature in general, and arguing for the “uniqueness” of Brazilian literary tradition.Footnote 4 This paper will explore the construction and circulation of the notion of a “revolutionary Brazil” through literary translation in socialist China. This is especially evident in the significance placed on the Brazilian northeast area, which socialist writers constructed as a revolutionary space through the translated works of Jorge Amado and Euclides da Cunha in the socialist camp. Moreover, a tracing of the change in canonization that mainly focuses on Spanish American literature is limited. Because it fails to explain why the canonization of Brazilian literature surprisingly maintains its stability by according Jorge Amado the most important status for more than fifty years. An analysis that focuses on Spanish American literature will not lead to further reflection of the lure of imagining “Latin America” as a unified geographical space, whether economically or politically beneficial for China, despite the recognition of its divergence. Particularly, it does not explain why there also exists nostalgia for Latin America’s leftist tradition in contemporary China as opposed to the nostalgic trend of magical realism.Footnote 5

Moreover, if we limit our analysis to the dynamics between literature and politics in China, we may ignore the question of how to situate Latin American intellectuals’ choice within national and global politics during the Cold War era. To stress only those who had close contact with the communist camp is to ignore the different choices that Latin American intellectuals made among competing universals of Cold War. On the other hand, it is also worthwhile to further investigate the active agency of those Latin American intellectuals who were receptive to the Chinese revolution to Latin America. As Rothwell points out, studies of communist China’s influence on Latin America often ignore the agency of Latin Americans in the transmission of Chinese revolutionary ideology, “Although China was eager and willing to promote its revolutionary ideology among Latin Americans, there could be no question of those ideas gaining any traction without an enthusiastic effort by Latin American sympathizers.”Footnote 6 What specific reasons motivated several Brazilian intellectuals and writers to travel to China and bring Chinese revolutionary experience and Chinese literature back to their own countries? Why and how did they contribute to the Chinese imagination of a revolutionary “Latin America” and Brazil as part of it? Also, how did their translation and critique contribute to the imagination of a homogenous, historically progressive stage that both China and Brazil share?

Based on these questions, this paper investigates the literary translation between China and Brazil from 1952, when Jorge Amado visited China for the first time, to 1964, when the Brazilian military government detained and expelled Chinese diplomats after the coup d’état. Literary translation between China and Brazil in this period, I argue, should be regarded as both cultural and social practices that sought alternatives aimed at transcending the bipolar universals of the Cold War. My paper mainly focuses on the mutual appropriation of revolutionary literary sources, especially socialist realist works, in the service of constructing national literature during the period of anti-colonialist/imperialist struggles for national independence in both countries. Also, it examines the discursive practices of Chinese and Brazilian intellectuals who contributed to the circulation of these literary works and with them revolutionary imagination. This new form of imagination sought to build tri-continental solidarity among Asian, African, and Latin American countries, which aimed at creating viable alternatives to not only the existing bipolar world order but also the discursive practices of the dominant colonial/imperial powers. Countering backward stereotypes of “underdeveloped area” in previous periods, these literary works represented a new image of people who were fighting for national independence from colonial/imperial exploitation and oppression. It is, however, also worth noting that such discursive practices were not always the main form of exchange. The absorption of literary sources was quite limited due to the fact that European and Soviet Union literature still served as the main literary model for Chinese and Brazilian leftist writers. Moreover, the battles of the Cold War largely overshadowed in-depth discussion of colonial experiences and anticolonial struggles. The dominant influence of the Soviet Union on the circulation and evaluation of these works shaped the mechanistic interpretation of them as loyal to the aesthetic of socialist realism and evidence of anti-American imperialist struggles. It is such mechanistic interpretation of history shaped by Cold War discourse, I argue, that deterred a more thorough reflection on anti-colonial/imperialist experience.

Caught in Cold War Dynamics: Culture as Battlefield

On January 31, 1952, Brazilian writer Jorge Amado arrived at the Peking airport with Cuban poet Nicolás Guillén after he received the International Stalin Prize for Strengthening Peace among Peoples in the Soviet Union.Footnote 7 Waiting for them at the airport were some of China’s most influential writers, including Guo Moruo, Mao Dun, Ai Qing, and Emi Siao. In the following month, Jorge Amado visited factories, villages, and historic sites such as the Great Wall and Summer Palace.Footnote 8 This visit marked the beginning of the close connection between the newly established People’s Republic of China and Brazil that lasted until the mid-1960s. Hundreds of Brazilians traveled at the invitation of the PRC government during this period.Footnote 9 The most prominent visitors among them were the leader of the Communist Party of Brazil, Luís Carlos Prestes (1959), and Brazilian vice president João Goulart (1961), who was the first Latin American head of state to visit China. Chinese economic and cultural delegations also visited Brazil with the help of those who had been to China.Footnote 10 Among them were prominent writers including Ai Qing, Emi Siao (1954), and Zhou Erfu (1959). The transcontinental travel of these writers, together with their works and their dominant influence in the literary sphere, inaugurated a new phase of history in which culture and especially literary translation became a significant form of diplomatic strategy for the PRC government to reach out to Brazil.

Cultural diplomacy played an essential role in the PRC government’s connection with Latin American countries during the Cold War era.Footnote 11 Being aligned with the Soviet Union, the PRC government adopted the Soviet “people-to-people” diplomacy rather than traditional “state-to-state” relations as counter to US intensified control of Latin American countries one the one hand and the Republic of China (ROC) government in Taiwan, who maintained its legitimate seat as China in the United Nations on the other.Footnote 12 To avoid suspicion from counterparts, such diplomacy mainly relied on establishing personal relations among intellectuals through the World Peace Council (WPC) and numerous cultural associations like the China-Latin American Friendship Association, whose activities appeared less aggressive than direct political propaganda. The performances that these art delegates brought to Brazil were mainly traditional Chinese arts such as the Peking Opera or acrobatics.Footnote 13

In the initial exchanges, the WPC and the socialist camp served as essential intermediaries in China’s efforts to gain support from Latin American leftist intellectuals.Footnote 14 For example, Emi Siao recalled that he became acquainted with Jorge Amado at the Union of Czech Writers in 1951.Footnote 15 And it is through entering the WPC that Guo Moruo and Emi Siao established close relationships with Latin American intellectuals, including Jorge Amado, and invited them to China. The mediating influence of the WPC can also be seen in the Asia and Pacific Rim Peace Conference that was held by the Chinese government between 1951 and 1952. More than 150 delegates from 11 Latin American countries (3 from Brazil) went to China. Right after the conference, some delegates established associations that aimed at promoting further cultural communications with China. In Brazil, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo each established a Brazil-China Friendship Society in 1953 and 1954, respectively.Footnote 16

Additionally, the PRC government also sought to establish party-to-party relations with Latin American communist parties and make use of them to increase its political and cultural influence. The Brazilian Communist Party (PCB), which sent a delegation to China in July 1953, was the earliest to establish such a relationship.Footnote 17 The Chinese efforts at winning support from Latin American communist parties were intensified after Khrushchev gave his “secret speech” at the Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party, which greatly shocked Latin American leftist intellectuals and led to their disillusionment with the Soviet Union.Footnote 18 For example, Jorge Amado was one of the leftist intellectuals who immediately fell into disillusion and turned to Cuba and Afro-Asian countries.Footnote 19 What made these leftists particularly disappointed was the post-Stalin Soviet’s policy of peaceful coexistence with the West, and its disavowal of violent struggle pushed more Latin Americans toward identification with anti-colonial and anti-imperialist struggles of China and other Afro-Asian countries.Footnote 20 After the Cuban government established a formal diplomatic relationship with the PRC government in 1960, the Chinese embassy at Havana, together with the Xinhua [New China] News Agency, which developed branches in four countries (including Brazil), largely facilitated the PRC government’s direct communications with Latin Americans without the Soviet Union as an intermediary.Footnote 21 As the competition between China and the Soviet Union in Latin America became increasingly fierce in the 1960s, the PCB split into pro-Soviet force (PCB), led by Prestes, and pro-Chinese force (PCdoB), led by Mauricio Grabois, João Amazonas, and Pedro Pomar.Footnote 22 PCdoB maintained contact with the PRC government and received revolutionary instructions from it. Whatever divergence there was, the PCB and later PCdoB’s support was essential to China’s efforts to increase its influence and support in Brazil in this period.

The Brazilian interest in China cannot be simplified as evidence of their political inclination to communism, however, because most of these visitors were non-communists. Besides the prevailing anti-American sentiment, many Brazilian visitors, like other Latin Americans, saw China’s ongoing economic and cultural construction as an alternative way to achieve national independence apart from the Soviet and American models.Footnote 23 The defense of national culture against European influence that had been an urgent concern in Brazil since the early twentieth century inspired Brazilian writers and artists to enhance their cultural ties with countries in Asia and Africa.Footnote 24 The desire to identify with Asian and African peoples who were seeking national independence and economic development was further fueled by the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), which sprouted from the Afro-Asian Conference in Bandung (1955) and the Cuban revolution.Footnote 25 (See Figure 1.) As the number of non-communist travelers between China and Brazil increased in the late 1950s, anxiety grew with regard to the Chinese government’s strategy of cultural diplomacy to increase its influence in Brazil. Reports of the New York Times indicated that although the majority of the Brazilian visitors to China were neither communists nor leftist-inclined, they generally acquired positive impressions of China and tended to put more pressure on their president, Janio Quadros, to establish diplomatic and trade relations with China.Footnote 26

Figure 1 Firsthand report of Bandung conference on Brazilian newspaper, Imprensa Popular, May 1, 1955.

NAM was not only attractive to Brazilian intellectuals, but also to reformist politicians who were inclined to get rid of their economic dependence on the United States and increase their influence in Latin America and the emerging third world. The socialist mode of state intervention in the national economy and social welfare system proved to be a better example for them than the capitalist mode of development in Western world.Footnote 27 Nothing demonstrated such policy orientation better than the Brazilian representative’s appearance at the Belgrade Non-Aligned Conference and Jõao Goulart’s visit to China in 1961. In his lecture published in the Chinese official newspaper People’s Daily, Goulart, who was then Brazilian vice president, claimed that the Brazilian government stands with all other newly independent and decolonizing countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America and adopts an independent policy that tolerated the difference of ideology. Moreover, he also expressed his government’s willingness to recognize the PRC government’s legal status in the United Nations.Footnote 28

The positive reaction of the Brazilian government, particularly during Goulart’s presidency, promoted the PRC government to increase diplomatic activities with Brazil. In 1963, the PRC government established the Xinhua News Agency in Rio de Janeiro.Footnote 29 The close contact with socialist China, however, aroused the suspicion that Brazil would become a socialist country. Brazilian sociologist Gilberto Freyre, who was the editor of the CIA-supported magazine Cadernos Brasileiros, warned his American audience that the United States must invest more money in Brazil’s industrial development to prevent it from becoming a communist country.Footnote 30 Although the Brazilian government had been simultaneously trying to maintain a stable diplomatic relationship with the United States, there was no tolerance of the neutral stand of Brazil. Especially after Goulart became president of Brazil, his close connection with China and other communist countries was regarded as a great threat to the United States.Footnote 31 Such tension finally resulted in the Brazilian coup d’état in 1964, after which the military government arrested nine Chinese, including seven trade mission members and two correspondents of the Xinhua News Agency, in the name of spy activities.Footnote 32 This incident, also exacerbated by the influence of the Sino-Soviet split in Brazil, led to a dramatic decline of the China-Brazil connection.

Despite its shortness, the China-Brazil “honeymoon” period facilitated travel for writers and artists across continents. Their footprints and personal accounts vividly reflected the political dynamics of Cold War. For example, Jorge Amado traveled to China through the Soviet Union and Mongolia in 1952. In 1957, he visited China again with Pablo Neruda through India and Burma after they participated in the peace conference at Sri Lanka. (See Figure 2.) Like other foreign visitors, his travel in China also followed strict plans and rules restricting where he could visit and what he could know. He was shocked to discover that their friends Emi Siao, Ai Qing, and Ting Ling disappeared because of the Anti-Rightist Campaign.Footnote 33 On the other side of the planet, when Ai Qing and Emi Siao visited Brazil and other countries in 1954, they faced various restrictions on their visas and on the presents they could bring to celebrate Neruda’s birthday.Footnote 34 In Footnote spite of the surrounding political tension, what is significant in this period is the role of these writers who not only contributed to a new form of diplomatic relationship, but also gave literary translation incomparable status and value in this period.

Figure 2 (From left to right) Pablo Neruda, Zélia Gatai, Jorge Amado.Footnote 35

Literary Translation in National and International Networks

In the 1950s, the literary translation between China and Brazil began with Jorge Amado’s first visit to China. After Jorge Amado won the International Stalin Prize for Strengthening Peace among Peoples, the Chinese newspapers and magazines introduced his works to Chinese readers.Footnote 36 His translator Wu Lao recalled that he read the English translation of Terras do Sem Fim [The Violent Land, 1943] in autumn 1951 and translated it into Chinese before Jorge Amado’s visit.Footnote 37 Between his two visits (1952 and 1957), four of his works were translated from other languages (English, Russian, French) into Chinese.Footnote 38 Teng Wei notices that the translation of Latin American literature was an important strategy for the PRC government to promote diplomatic relationships with Latin American countries. Whenever a Latin American writer visited China, there would be introduction or translation of his or her works.Footnote 39 No other Brazilian writers enjoyed the same level of reverence accorded to Jorge Amado. His influence in the Soviet Union–led socialist camp and his status at the WPC and PCB determined the importance of his works in China. Moreover, because Brazil refused to send an army to the Korean War, Jorge Amado’s visit in 1952 was regarded as an inspiring message of support for the PRC from Brazilians.Footnote 40 Therefore, the Chinese state media frequently propagated his image as a fighter for peace and published his lecture about Brazilian peoples’ ongoing struggle against American imperialism and support for the PRC.

In addition to diplomatic concerns, the translation of Jorge Amado’s novel was also part of the ongoing institutionalization of literary translation and publication. Hong Zicheng emphasized the importance of reassessing the nature and value of both Chinese and foreign literary works. Since the establishment of the PRC, Hong says, it was necessary to set the basic norm for literary writing and the selection and absorption of certain literary sources that were useful for the development of national literature. This follows the tradition of Chinese leftist literature that had been regarding foreign literature as its indispensable nutrients since the early twentieth century. Lu Xun, Mao Dun, and other Chinese writers tried to broaden the view of national literature by translating non-Western European literature toward which they felt more empathetic.Footnote 41 The Chinese writers’ empathy toward literature of oppressed nations was largely influenced by the Danish critic Georg Brandes, who regarded national literature as a reflection of its nationality and the carrier of the inner spirit of a nation.Footnote 42

Although the oppressed nations here mainly refer to those of eastern Europe, Chinese writers looked for reference from other parts of the world perceived to share similar historical experiences. It is noteworthy that Indian and South African literary works were also translated in the Compendium of New Chinese Literature edited by Zhao Jiabi.Footnote 43 With regard to Brazilian literature, Xiaoshuo yuebao [Fiction Monthly] published Mao Dun’s introduction of Graça Aranha’s novel Canaã (1902), his translation of Aluísio Azevedo’s short story “Útimo Lance” (1893), and Issac Goldbeerg’s article “Brazilian literature” in the early 1920s.Footnote 44 Mao Dun was not the only leftist intellectual who was attentive to Brazilian literature. Zhou Yang also published his review of Brazilian literature in 1931.Footnote 45

This tradition was later enhanced by the nationwide institutionalization of literary translation and publication after the foundation of PRC. In 1954, Mao Dun, who became the minister of culture and president of the Chinese Writers Association of PRC, gave a report at the National Conference on Literary Translation. In his report, Mao Dun stressed the importance of introducing progressive literature from colonial and semi-colonial countries suffering from imperialism.Footnote 46 Such deep identification with a shared colonial experience not only evoked the spirit of the May Fourth writers’ translation of literature of those oppressed but also Mao Zedong’s talk at the Yannan Forum on Literature and Art to orient literary translation through political intervention in order to better serve the masses. For Mao, politics and literature are mutually dependent. He regards literature as part of the political practice that can transform writers and artists for social revolution at the spiritual level.Footnote 47 Literary translation has to be carefully examined because it matters to the critical absorption of foreign literary sources for new socialist literature. Candidates for literary translation must be politically or ideologically “healthy” in their content, as well as artistically articulate using language that people could understand. Directed by state power, literary translation and canonization was raised to the center of political and social life in the 1950s.Footnote 48 State intervention, however, effected a radical transformation of each part and participant of the translation process, including translators, publishing houses, and literary magazines, in order to establish a highly collaborative form of production that left little space for individual choice.Footnote 49

In addition, many universities opened foreign languages majors to train professional translators. The first Spanish major was established at Beijing Foreign Languages Institute (now Beijing Foreign Studies University) in 1953. The first Portuguese major was established at Beijing Broadcasting Institute (now Communication University of China) in 1960. One distinct characteristic of the Spanish and Portuguese majors was that they were established through the collaborative efforts of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Latin American visitors (except for those Spanish refugees who went to the Soviet Union at the end of the Spanish civil war).Footnote 50 These Latin American visitors not only taught languages but also explained the political situation and anti-imperial struggles of Latin American countries to students.Footnote 51

Compared to the previous period, state-oriented literary translation placed increasing significance on the translation of Afro, Asian, and Latin American literature.Footnote 52 The translation of Brazilian literature also increased dramatically.Footnote 53 Among Jorge Amado’s three novels, for example, Terras do Sem Fim was printed three times (34,500 copies); São Jorge dos Ilhéus was printed twice (16,300 copies); and Seara Vermelha received four printings (31,500 copies). In addition, because the Portuguese language major was established very late in China, most of the works were translated from Russian, English, Spanish, and French translations except for Castro Alvez’s poems. That most of the translation were based on books published in the Soviet Union or the French communist publishing houses testifies to the fact that these literary works were closely connected to socialist literary networks, which refused to limit the discussion of these works within national borders.

The Brazilian responses to the transformation of literary translation and publication in China varied on different sides. Learning of the passage of law effecting the socialist transformation of China’s publishing industry in 1952, a Brazilian newspaper Diário da Tarde reported that Chinese editors were experiencing a hard time due to state intervention into their publishing businesses.Footnote 54 This raised concerns about the freedom of writing and publishing. Brazilian writer Lygia Fagundes Telles, who had been to China with a group of Brazilian writers in 1960, mentioned that when they had conversations with Chinese writers, their first question was how they survived within the socialist regime.Footnote 55

Such intervention was, however, attractive for some Brazilians who had close observations and communications with Chinese editors and writers. Brazilian journalist Jurema Yari Finamour, who visited China in 1956, published his interview with an editor from the Shanghai Literature & Art Publishing House. During this interview, Finamour probed the editor on such concerns as how the PRC government guaranteed that writers had enough time to do creative works apart from working in the field; how the special committee of each publishing house examined the content of books before publication; and how much the government paid their writers. Although Finamour challenged the editor, for example, by complaining about the price of translated Chinese literature, the editor’s detailed explanations suggested the desire of Chinese publishing house representatives to persuade foreign visitors to put aside their doubts about the freedom of writers and publishers.Footnote 56

Similarly, Brazilian writer Eneida Costa de Moraes visited the Foreign Languages Press and the Youth & Children’s Publishing House in Shanghai in 1959. Although astonished by the highly collective form of translation and publication works under the guidance of a special committee, Moraes was impressed that it raised the quality and quantity of the state-oriented literary translation and publication, which allowed Chinese readers to enjoy various types of books at reasonable prices. In her published report in the Brazilian newspaper Diario de Noticias, she mentioned that the price of children books fell by 50 percent since 1950 under the government’s intervention. Moreover, Moraes noted that wherever she went, she always found young people with books, and the bookstores were always full.Footnote 57 Moraes’s report highlighted the mass reading culture that grew largely under the policies of state-oriented publishing projects, which made books more widely available to the masses.

It is significant that Brazilian writers also participated the translation and canonization of Brazilian literature. Moraes’s assigned tasks during her visit were illustrative of the collaborative efforts of Brazilian writers and Chinese publishing houses in circulating translated Chinese literature. Apart from introducing their works, Moraes recalled, the Chinese editors of the Foreign Languages Press also asked her to select some books to bring back to Brazil. Although she selected only a few, she found that there was a big package of books in her room when she returned to her hotel. Among the books she brought back were the French translations of Selected Stories of Lu Xun and Folklore Art in China.Footnote 58 It is clear that the Chinese publishing houses were making use of this opportunity to introduce their books to Brazilian readers through their Brazilian visitors. It seemed that Moraes also liked these books, for she cites Lu Xun’s words from “Guxiang [My Old Home]” in the front page of her travelogue to socialist countries: “No começo a Terra não tinha caminhos; mas cada vez que um grande grupo de homens passa pelo mesmo lugar, no fim um caminho se forma [For actually the earth had no roads to begin with, but when many men pass one way, a road is made].”Footnote 59 And the title of the travelogue also comes from these words: Caminhos da Terra [Roads across the Earth, 1960].

Another example is Jorge Amado, who played the most important role in the translation and introduction of Chinese literature. Jorge Amado’s interest in Chinese literature had begun before his visit to China. In 1945, he translated Sheng Cheng’s Wode muqin [My Mother, 1928] from French to Portuguese, which was published by Editora Brasiliense in the collection “Coleção Ontem e Hoje [Collection of Yesterday and Today].” (See Figure 3.) Among the same collection was Xiao Jun (Tian Jun)’s novel Bayue de xiangcun [Village in August, 1935], which was translated from English (including Edgar Snow’s introduction). (See Figure 4.) Both novels are focused on Chinese revolution. Later he got acquainted with Chinese writer Emi Siao through the international networks of the communist camp. During his first visit to China, he became friends with Ding Ling, Ai Ching, Guo Moruo, and Mao Dun. Throughout the 1950s Jorge Amado had been dedicated to not only helping Chinese writers and artists with their trip to Brazil, but also introducing Chinese literature, art, and film to Brazilian readers.

Figure 3 Book cover, the Portuguese translation of My Mother.

Figure 4 Book cover, the Portuguese translation of Village in August.

When Emi Siao and Ai Qing went to Chile to celebrate Pablo Neruda’s fiftieth birthday in 1954, Jorge Amado was also in the party and helped them during their transfer at Rio de Janeiro.Footnote 60 In 1955, the Brazilian publishing house Editorial Vitória published Luiz Barreto de Sá’s translation of Ding Ling’s novel Taiyang zhaozai sanggan heshang [The Sun Shines over the Sanggan River, 1948] under the direction of Jorge Amado. (See Figure 5.) When the Chinese performance troop went to Brazil in 1956, the newspaper Para Todos, of which Jorge Amado was the editor, published a considerable number of articles that thoroughly covered all their activities as well as Brazilian intellectuals’ enthusiastic responses. Particularly, it invited a Chinese delegate to write an article to introduce the history of Chinese opera to Brazilian readers.Footnote 61 In the following years, the newspaper continued to publish articles that introduced Chinese films and even held a competition to select Brazilian art delegates to make an exhibition in Shanghai.Footnote 62

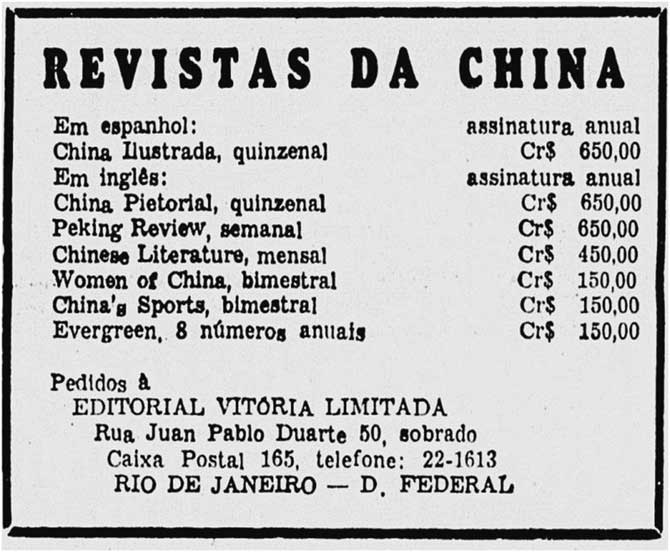

Figure 5 Editorial Vitória’s advertisement on subscription of Chinese magazines.Footnote 63

In addition to capitalizing on the personal influence of Brazilian visitors, Chinese publishers also utilized PCB-supported publishing houses to disseminate their literature. Ding Ling’s novel was published by Editorial Vitória, which was founded in 1944. Throughout this period it had been the main publisher of PCB that published novels by national and foreign authors on Marxist theory and history. Moreover, it also offered subscriptions of many magazines that were released by Chinese publishing houses. Among them were the English magazine Chinese Literature in 1951, which was in charge of translating and introducing Chinese literature to foreign countries. To promote this magazine, PCB’s newspaper Imprensa Popular introduced every new issue as soon as it was released. (See Figure 6.)

Figure 6 Book cover of the Portuguese translation of The Sun Shines over the Sanggan River.

Another publishing house was Edições Zumbi, which was founded with support from PCB in 1957. Compared to Editorial Vitória, it was very small and only had three operators: Elvio Eligio Romero (Paraguayan), Antonietta Dias de Moraes (Brazilian writer), and Emiliano Daspett (Paraguayan).Footnote 64 As soon as it was founded, it published a series of translated foreign novels, including a collection of Lu Xun’s Kuangren riji [1918; Portuguese: Diário de um Louco; English: A Madman’s Diary] translated by Antonieta Dias de Moraes. (See Figure 7.) The advertisement of the book in newspapers recommends it by citing Mao Zedong’s praise that Lu Xun was the model for all Chinese writers, whose works mark the beginning of the modern history of Chinese thought.Footnote 65 It is not clear why and how Brazilian translators selected Ding Ling and Lu Xun, and from what language they translated their novels. The published articles about Ding Ling and Lu Xun’s novels in Brazilian newspapers were mainly from PCB members or from those visitors who had been to China.

Figure 7 Book cover of the Portuguese translation of A Madman’s Diary.

Unlike the translation of Brazilian literature in China, the reception of translations of Chinese literature was quite polarized due to Cold War tensions. In general, literature from the PRC was regarded as communist propaganda. An interesting example is that in 1957, a newspaper interviewed a failed contestant of a knowledge competition TV program called “O Céu é o Limite [The Sky Is the Limit].” The fifteen-year-old boy lost the competition because he failed to answer the question about Ding Ling’s novel The Sun Shines over the Sanggan River. Having learned Chinese for six years at the ROC’s embassy, the intelligent boy was angry that he lost the game only because of a novel of communist propaganda, which he believed merely collected some characters and created a falsified history, “We should not include it as Chinese literature.”Footnote 66

This incident exemplifies how Cold War concerns redefined the essence of what constituted proper “Chinese literature.” Moreover, it directs our attention to the more popular, “true” Chinese literature that was competing with those from the “communist China” in Brazil. Besides classical Chinese literature, the most influential contemporary Chinese writer in this era was Lin Yutang, who was an active anti-communist writer living in the United States. At the same time that the Chinese writers from communist China were trying to get their visa, Lin Yutang also visited Brazil and gave his lectures to a large number of audiences as a “real” representative of Chinese literature and culture in 1959. In an interview, he cited the Stalin Prize winner Ding Ling, who was living in a poor situation after the anti-rightist movement, to criticize the PRC government for depriving writers of their freedom. Even writers in the Soviet Union, Lin claims, had more freedom than those in China.Footnote 67

The development of Cold War tensions largely limited the introduction of literary works about the Chinese revolution. In 1963, Zumbi’s advertisement of Lu Xun’s fiction could still be found in Brazilian newspapers. After 1964, however, there were no more space for new translations of Chinese revolutionary literature. In spite of the difficulties, we can see that some Brazilian intellectuals did succeed in linking with the Chinese revolution through translated literature and magazines before 1964. These works, together with the large number of travelogues of China written by Brazilian visitors, served as the main source of discursive practices that connected China and Brazil through their shared struggle for national independence. There is no other period in which literary translation played such an important role in sharing experience of transcontinental solidarity against colonialism and imperialism.Footnote 68

Imagining the World Revolution through Literary Translation

The introduction and interpretation of Jorge Amado’s trilogy in the early 1950s was the most revealing example of the position and function of literary translation. As a loyal supporter of the Soviet Union, Jorge Amado was first known as a “fighter for peace” and a “poet” who eulogized the socialist camp. When he went to China in 1952, Renmin wenxue [People’s Literature] published the translation of an excerpt from Os Subterrâneos da Liberdade (The Bowels of Liberty] and an article that was written by a Soviet critic F. Kel’in.Footnote 69 Moreover, Yiwen also translated his eulogy of the Soviet Union, “Canto à União Soviética [Song for Soviet Union]” in 1953.Footnote 70 Because of his political influence, the introduction of Jorge Amado’s political activities often overshadowed his writing career. Although three of his novels were translated into Chinese, they were mainly regarded as a faithful reflection of Brazilian history:

In the first novel [Terras do Sem Fim], Amado describes the fight between two feudal aristocrats for tropical forest, which expanded to civil war. In the second novel [São Jorge dos Ilhéus], the American capitalists’ company came. It raised cocoa’s price and then let it decline sharply. The local plantations went bankrupt and were sold to the American company. Therefore, the American company carried out fascist rule in the area. A young communist started to organize local proletariat to revolt. However, the party was young and lacked experience, so [the revolt] failed. . . . Then transitioned to the third novel [Seara Vermelha]. The reactionary rule made Brazilian people suffer cold and hunger, so the people organized and revolted. The zenith of this novel is the revolt in 1935. This revolt was led by Aliança Nacional Libertadora (ANL), which aimed at overthrowing the reactionary rule of Vargas but failed because of the violent suppression from both national and foreign forces. The end of the novel depicts the PCB finally emerging from underground after struggle.Footnote 71

Almost all Chinese critics adopted such interpretations.Footnote 72 Such interpretations, however, were not created by Chinese critics but came from Jorge Amado himself and critics from the Soviet Union.Footnote 73 Jorge Amado, in his novel São Jorge dos Ilhéus, was said to move the historical time of the rise of planters from World War I—which quickly collapsed in the postwar era—to the 1930s, in order to associate it with imperialist exploitation.Footnote 74 By doing so, Amado successfully conforms Brazilian history to Marxist theory. In fact, Amado’s revision was just part of Brazilian intelectual efforts to use Marxism to understand and seek solutions for the backwardness of their country since the 1930s.Footnote 75 In 1952, Guangming Daily published Li Sheng’s translation of F. Kel’in’s article on Latin American Progressive Writers, which summarized Amado’s trilogy as a reflection of the three phases of Brazilian people’s history: feudalism; foreign imperialist capital’s invasion; and people standing up and fighting for freedom.Footnote 76 In spite of the World Peace Council’s effort to support and promote literature that conformed to the criteria of socialist realism, the unanimous interpretation among Chinese and Soviet Union critics indicates the continuous influence of the Comintern’s definition of Latin American revolution in their blueprint of world revolution, which had been controversial throughout its history.Footnote 77 Manuel Caballero points out that the Comintern was very arbitrary and too impatient to understand the historical and social prerequisite for launching a revolution in Latin America, arguing that “the Comintern proposed a revolution in Latin America and organized the armies to fight for it before making any attempt to understand what kind of societies the Latin Americans lived and therefore, what kind of revolution they needed.” Despite the dissidence of some Latin American intellectuals, it still “placed Latin America as a whole in the ‘semi-colonial’ category,” Caballero argues, “whose dominant class was that of big landed proprietors allied to imperialism.”Footnote 78

Although the Chinese Communist Party’s stance was different from the Comintern concerning the issue of launching revolution in underdeveloped regions of the world, its understanding of Latin America was clearly influenced by the Comintern’s views. By including all Latin American countries within a homogenizing notion of historical progress, it created a sense of closeness that connected anti-colonial struggles in the same semi-colonial category. Such configuration determined that Latin American literature had to be constructed as being whole regardless of its internal differences. In 1963, Wang Yangle wrote the first book about the history of Latin American literature, Lading meizhou wenxue [Latin American Literature].Footnote 79 Wang pointed out that the literary developments in each nation of Latin America were completely parallel, for they all conveyed the same aspiration for liberation and revolution from American imperialism. Similarly, another critic Wan Qing argues that “progressive Latin American literature had an anti-colonial, anti-feudal and anti-dictatorial character since it was born.”Footnote 80

Wang’s conception of the origins and unity of “Latin America” reflects how Cold War dynamics shaped a highly politicized definition of a regional space and literature. It further developed into a literary imagination of world revolution in which anti-feudalist and anti-imperialist struggle for national independence united Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Wang Congcong points out that the name “ya-fei-la” (Asia-Africa-Latin America) became a new political and cultural symbol indicative of China’s self-identification of its position in the world. And the main function of literary relations with Afro-Asia Latin American countries is to enhance the mutual identification among peoples and stir up anti-imperialist fervor.Footnote 81 It was this particular function that determined how translated literary works were selected, introduced, and accepted in this era. In February 23, 1957, China Youth Daily published a reader’s letter “Wo xihuan ‘Huang jinguo de tudi’ ” [“I like São Jorge dos Ilhéus”]. In the letter, the reader Mu Zi, who worked in a hospital at Beijing, was deeply moved by parallels between Chinese landlords and Brazilian plantation owners through Jorge Amado’s novel.Footnote 82

Mu Zi’s reading of the novel reflected how translated literature aroused Chinese readers’ imagination of a revolutionary Brazil that was suffering from the same exploitation and oppression. Unlike the Comintern, which marginalized Latin America, the Chinese regarded it as one of the most important actors in their imagination of the world revolution, particularly after the Cuban revolution. In some of his talks with Latin American representatives, Mao Zedong stressed the importance of breaking reverence for Euro-American civilization and strengthening identification among Afro-Asian Latin American countries. He called for reversing the general conception of what/who was considered advanced/backward, civilized/savage by claiming that Asia, Africa, and Latin America were more civilized and advanced than Western countries. It is interesting to see how Mao perceives racial difference as invalid in the context of third world solidarity,

I feel happy as long as I see friends from Asia, Africa and Latin America. Have you had contact with Africans? I recently met some young representatives from African countries from Kenya, Cameroon, Guinea and Madagascar. Malagasy’s skin color is between black and yellow, which is similar to ours. I don’t know any of them but still feel close [to them]. There is [only] one reason, that is, our countries are in the same position in the world.Footnote 83

In the Chinese imagination of world revolution, the main subject should be “people,” no matter what race or what ethnicity they are, of “ya-fei-la” (Asia-Africa-Latin America), which later developed into the concept of “third world.” By identifying people rather than any specific race, such imagination tries to transcend the cultural difference or racial difference that had been shaped and perpetuated by colonial discourse for centuries. The visual representation of Latin Americans went through a radical change in this period. In the previous period, the images and accounts of naked barbarians in the Amazon forests were still popular on circulated missionary magazines. (See Figure 8.) Since the 1950s, Latin Americans appeared in movies and magazines as a group who waved their arms and fought for revolution, especially after the Cuban revolution, which fixed fighting Footnote Cubans as the representative of Latin Americans. (See Figure 9.)

Figure 8 Brazilian indigenous people.Footnote 84

Figure 9 Documentary “Zhandou de guba” [Cuba Fight, 1960], made by China’s Central Newsreel and Documentary Film Studio.

In addition to the visual representations, there were a large number of newspaper commentaries of the political situation in Latin America. Particularly, many writers traveled between China and Brazil and used their firsthand report, lecture, or writing to enhance such a sense of intimacy. Ai Qing wrote two poems about Black people he saw on the streets during his stay at Rio de Janeiro in 1954. Ai Qing’s sympathy with the miserable life of the Black people led him to write numerous stories in which he imagines the pain within their hearts. In “Heiren guniang zai gechang [A Black Girl Is Singing],” he describes a Black girl holding a White baby in her arms. The Black girl who is singing happy songs to the crying baby, Ai Qing guesses, might be a miserable maid serving a White family. In “Lianmin de ge [Song of Sympathy],” he criticizes Rio de Janeiro as a licentious society where old White men hold hands with young Black girls.Footnote 85

Another Chinese writer, Zhou Erfu, who led a group of cultural delegates to Latin America between 1959 and 1960, published a series of reportage literature on Latin America’s colonial history and contemporary struggle in People’s Daily. In Brazil, Zhou Erfu visited the Museum of the Inconfidência Ouro Preto in Minas Gerais and a café plantation in São Paulo. Zhou Erfu reported on his close contact with Brazilian people and observation of their living conditions under the exploitation of American imperialism. Zhou’s understanding of Brazil’s colonial history, however, seems to be limited by his dogmatic understanding of Marxist theory. For example, while criticizing European colonial activities in Latin America, he praised Colombus’s discovery for promoting the development of world history. The discovery of Latin America, he believes, resulted in the decline of feudalism and aceleraion of the progress of capitalism, which paved the way for socialist revolutions. More ironically, he treats Portuguese colonialism as bygone history and overlookes the cultural and economic connection between China and Brazil that was established through centuries of Portuguese colonial activities.Footnote 86

It is interesting to see how the Brazilian Northeast became a central concern in those literary exchanges. The Brazilian intellectuals’ concern with the uneven economic development within the nation motivated them to construct a notion of the Northeast as a poor, miserable place that was full of potential for peasant revolt and agrarian revolution.Footnote 87 And it was through the Northeast that some Brazilian intellectuals found their own parallels to China in the 1950s. Ding Ling’s novel was introduced as a way of understanding the peasant revolution and land reform in Brazil. Interpretation of Ding Ling’s novel was, however, also largely limited by the lack of in-depth observation of the land reform. There were very few analyses of the novel and its historical background except for a basic introduction of its plot.Footnote 88 Moreover, the imagination of an exotic Orient was still prevalent in Brazilian writings of communist China, of which the direct visual evidence are the book covers of translated Chinese literature.Footnote 89 (See Figures 3, 4, 5, 7.)

On the other side of the planet, hoping that Latin American peasants could also be mobilized through land reform, the PRC government also paid attention to the Brazilian Northeast as a potential region for joint peasant revolution. Francisco Julião, leader of the peasant leagues in Brazil’s Northeast, was invited to visit China and meet with Mao Zedong at least once in the early 1960s.Footnote 90 Faced with the potential threat of peasant revolution in the Northeast, the United States was anxious to extinguish the fire of revolution by investing hundreds of millions of dollars to help the development of the Northeast.Footnote 91

Since the Cold War placed the Northeast at the center of the discursive practices of both sides, it was not a coincidence that most of the translated Brazilian literary works in this period focused on the Northeast. Moreover, the late 1950s saw an increase of interest in Euclides da Cunha, whose novel Os Sertões [The Backlands, 1902] was celebrated by Chinese critics as the great reportage literature on the most noble peasant revolution in Brazilian history. In 1959, China held a major commemoration conference on the fiftieth anniversary of Cunha’s death. Both Brazilian and Chinese writers participated in the event. Chinese writer Zhou Erfu and Brazilian writer José Geraldo Vieira gave lectures about Cunha.Footnote 92 This grand conference not only established the status of Os Sertões as a canon of the peasant revolution, but also highlighted the significance of reportage literature as a model to represent revolutionary struggles.

Chinese critics often ignored the trivial change of the canonical status of Brazilian literature in the late 1950s. After it was translated into Chinese in the same year, Os Sertões took the place of Jorge Amado’s novels and dominated the Chinese imagination of Brazil as a revolutionary space that originated from the “fudi” of the Northeast. In 1960, Wang Shoupeng (Wang Yangle) published the article “Latin-American Literature Comes to China,” which introduced the achievement of literary translation to foreign readers, in the English language magazine China Reconstructs. In this article, he does not mention any of Jorge Amado’s works. This change did not simply result from Jorge Amado’s retreat from communist activities; the Chinese magazine criticized him publicly until 1964.Footnote 93 Rather, it reflects the transition from the Soviet model to the Chinese model as the critic tried to understand Brazil. It also reflects how the Brazilian intellectuals, through constructing various discourses about the Brazilian Northeast and Latin America, inscribed these spaces on the utopian map of world revolution.

Conclusion

In 1987, Jorge Amado made his third visit to China when the magic realism “boom literature” was popular among Chinese writers. After thirty years, he met again with his friend Ai Qing, who had just lived through the tough years of the cultural revolution.Footnote 94 By this time, Amado had long begun to refute his previous identification with the category of “Latin American literature.”Footnote 95 By stressing the heterogeneity of national literature, Jorge Amado not only separates literature from political practice that sought to unite the continent, but also negates the political practices that searched for transcontinental anti-colonial/imperial solidarity among third world countries in the previous period. Ironically, his novels gained another round of popularity among Chinese readers and ensured the profits of publishing houses through the sexual image of his characters. (See Figure 10.)

Figure 10 Book cover of Chinese translation of Dona Flor and Her Two Husbands, with the specific note of “full translation” (1994 reprinted version).

It is generally believed that the Cold War politics depreciated the value of literature and the autonomy of writers. It is true that politics dominated the form and content of literary writing and translation in this period. Their practice, however, can hardly be reduced to political propaganda. For the writers’ practice differed from each other. And they were not always in accord with the ideologies that they embraced. For instance, Ai Qing’s poem “Cape of Chile [Zai zhili de haijia shang],” which was written when he represented the PRC government at the celebration of Chilean poet Pablo Neruda’s birthday, became the “proof” of his formalism during the disputes over the form and content of Chinese new poetry. Feng Zhi criticized Ai Qing for appreciating the details of the decoration of Pablo Neruda’s house, which shows his inclination toward formalism, rather than filling his poem with combative spirit for the political struggle for peace.Footnote 96

In addition, to treat writers as tools of political propaganda ignores the fact that many intellectuals, who were not necessarily leftist, played an active role in the hot battles of Cold War. To describe Cold War Latin American history within bipolar battles ignores the fact that these intellectuals traveled across the strictly defined Cold War boundaries and tried to construct a new way of cultural connection. We cannot deny that their attempts were quite limited because it was hard to transcend the influence of superpowers. We should, however, also value their efforts as part of the social practices that sought a new sense of interconnectedness between two continents that would override the old one that was shaped by Western missionaries for centuries. The interconnectedness between the two continents, and also with the African continent, was believed by many intellectuals to be based on anti-colonial/imperial struggles and the pursuit of national independence. Such belief thus contributed to the climax of discursive practices between China and Brazil in the twentieth century, which connected the two countries through a constructed imagination of the world revolution.