Introduction

What characteristics do state supreme court justices prioritize when choosing leaders? At the federal level, collegial court leaders are appointed or rotated by seniority. Footnote 1 In a plurality of states, however, apex court justices are selected by peer vote. Compared to the most commonly employed institutional alternatives, peer-vote selection lacks transparency. Courts using this mechanism do not typically reveal vote totals or explain why one person was selected over others (see, for example, The Albany Herald 2018). Given the considerable power state supreme court chief justices enjoy (Reference Hall and BraceM. G. Hall and Brace 1992; Reference Hall and WindettM. E. K. Hall and Windett 2016; Reference Wilhelm, Vining, Boldt and BlackWilhelm et al. 2020), it is important to understand how they obtain office (Reference Vining, Wilhelm and WanlessVining, Wilhelm, and Wanless 2019). And with respect to a relatively opaque procedure such as peer-vote selection, evaluating institutional performance depends on our ability to unravel the determinants of these group choices. As debate about how to choose court leaders continues (Reference Peppers and OldfatherPeppers and Oldfather 2012; Reference SmithSmith 2015; Reference SwaineSwaine 2006), evidence concerning the institutional performance of peer-vote selection rules can help guide public policy.

We analyze the determinants of chief justice selection by peer vote in state supreme courts. Drawing from a rich interdisciplinary literature on leader selection in the public and private sectors, we develop a theory of chief justice choice emphasizing experience, diversity, and politics. Leveraging within-contest variation from peer votes spanning 1965 through 2016, we find that selection often defaults to a seniority rotation norm resembling the rule governing federal circuit courts. More generally, the relationship between tenure and selection is nonlinear, with the probability of being voted chief increasing through the first fifteen years of experience before declining. Contrary to previous results (Reference Langer, McMullen, Ray and StrattonLanger et al. 2003), we find little evidence that a justice’s ideological divergence from the court median or important state officials is associated with selection outcomes. However, justices who dissent more often than their peers are less likely to be voted chief. We find no evidence of discrimination against women or people of color.

Our contribution to the chief justice selection literature is theoretical, empirical, and methodological. Theoretically, we build on existing research by developing and testing a more comprehensive account of how personal characteristics may influence peer voting. Empirically, we contribute more than a half century’s worth of new data on peer-vote contests. Methodologically, we improve on the previous literature by leveraging within-contest variation in modeling selection from relevant choice sets. Combined, these contributions generate new insights about the determinants of chief justice selection by peer vote. The results also enhance our understanding of political leader selection more generally (Reference CannCann 2008; Reference Deering and WahlbeckDeering and Wahlbeck 2006; Reference O’BrienO’Brien 2012) and contribute to a burgeoning literature on judicial decision-making outside of the case context (Reference Jensen and MartinekJensen and Martinek 2009; Reference HallM. G. Hall 2001; Reference StatonStaton 2010).

State Supreme Court Chief Justices

Chief judges of state (Reference Langer, McMullen, Ray and StrattonLanger et al. 2003; Reference Langer and WilhelmLanger and Wilhelm 2005; Reference Norris and TankersleyNorris and Tankersley 2018), federal (Reference Danelski and WardDanelski and Ward 2016; Reference Davis, Clayton and GillmanDavis 1999; Reference Epstein and ShvetsovaEpstein and Shvetsova 2002), and comparative (Reference Dawuni and KangDawuni and Kang 2015; Reference Smyth and NarayanSmyth and Narayan 2004; Reference Wetstein and OstbergWetstein and Ostberg 2005) courts have long enjoyed special attention in the study of judicial politics. This emphasis is warranted given the internal and external power enjoyed by these officials. In this section, we highlight the role chief justices play in state politics. As Reference Vining, Wilhelm and WanlessVining, Wilhelm, and Wanless (2019, 4) note, “The chief justice is influential within a state’s legal and political system due to the powers, duties, and responsibilities associated with the job and is seen as influential by other political elites.” Illustrating the importance of state apex court chief justices demonstrates why it is important to understand the determinants of leader selection.

State supreme court leaders often enjoy considerable decision-making power. Although practices vary over time and across states (Reference HallM. G. Hall 1990; Reference Hughes, Wilhelm and ViningHughes, Wilhelm, and Vining 2015; Reference McConkieMcConkie 1976), some chief justices enjoy unilateral opinion assignment power. Other states follow the U.S. Supreme Court’s model of having chiefs make assignments when they are in the majority coalition. Even if case dispositions are controlled by the median justice, and opinion content by the median member of the majority coalition, opinion writers enjoy an important first-mover advantage with respect to opinion content (Reference Bonneau, Hammond, Maltzman and WahlbeckBonneau et al. 2007; Reference Carrubba, Friedman, Martin and VanbergCarrubba et al. 2012; Reference Clark and LauderdaleClark and Lauderdale 2010). More so than with rotation and random assignment rules, discretionary opinion assignment mechanisms increase the potential for partisan and strategic decision making. Furthermore, this discretion creates opportunities for discrimination (Reference Christensen, Szmer and StritchChristensen, Szmer, and Stritch 2012; Reference Kaheny, Szmer and ChristensenKaheny, Szmer, and Christensen 2019).

Chief justices can also impact collegial relations. Considerable attention has been devoted to understanding how chief justices contributed to the demise of the U.S. Supreme Court’s consensual norm (Reference Caldeira and ZornCaldeira and Zorn 1998; Reference HaynieHaynie 1992; Reference Hendershot, Hurwitz, Lanier and PacelleHendershot et al. 2013). At the state level, scholars have shown that chief justices impact separate opinion writing. One persistent finding is that discretionary opinion assignment rules, which allow chief justices to reward cooperative colleagues and sanction uncooperative ones, are associated with fewer dissents (Reference Brace and HallBrace and Hall 1990; Reference Hall and BraceM. G. Hall and Brace 1989; Reference Hall and Brace1992). This relationship is attenuated, however, in states with more judicial resources (Reference Hall and WindettM. E. K. Hall and Windett 2016). A chief justice’s effect on consensus may even persist after returning to the associate rank (Reference Boyea and Farrar-MyersBoyea and Farrar-Myers 2011). With respect to chief justice selection mechanisms, states that have affirmative choice rules such as peer voting may confer leaders with enhanced legitimacy, thereby reducing dissent; this effect however, also attenuates as court resources increase (Reference Hall and WindettM. E. K. Hall and Windett 2016).

Outside of court, chief justices have administrative responsibilities and serve as judicial spokespersons. State (Reference Wilhelm, Vining, Boldt and TrochessetWilhelm et al. 2019) and federal (Reference Vining and WilhelmVining and Wilhelm 2012) chief justices produce state of the judiciary addresses emphasizing similar issues, including judgeships and budgets. Chief justices also propose reforms on topics such as caseload, judicial diversification, court resources for those with limited English language proficiency, rural access, judicial independence, pro se litigation, public defender funding, specialized court creation, judicial training, and performance standards (see, for example, Reference BoughtonBoughton 2019; Reference BuffonBuffon 2019; Reference PittPitt 2020; Reference ThomasThomas 2020; Reference YoungYoung 2008). Administratively, chief justices also undertake tasks such as overseeing budget proposals, leading judicial councils, and chairing merit selection commissions.

Chief justices also engage in educational outreach that may impact perceptions of institutional legitimacy. Chief Justice Tani G. Cantil-Sakauye of the California Supreme Court describes visiting schools “so that our students and our citizens understand that the strength of our democratic institutions relies on the public’s understanding of those institutions” (States News Service 2013). R. Fred Lewis, former Chief Justice of the Florida Supreme Court, spoke at numerous middle and high schools while also holding information sessions encouraging lawyers and judges to “volunteer to speak with classes at every school in Florida” (Reference KrauseKrause 2006). In Arizona, Chief Justice Robert Brutinel travels to every county to meet with local court officials, explaining, “It’s important to talk to the people who are actually doing the work to understand what the problems are, and what the Supreme Court and the administrative office can do to help” (Reference BuffonBuffon 2019). And led by its chief justice, the Illinois Supreme Court hosts a “Law School for Legislators” event “intended to familiarize the legislative branch with court operations and to foster dialogue of communication, cooperation and coordination between the legislative and judicial branches” (Reference AndersonAnderson 2017).

Interfacing with governors and legislators is among the most important responsibilities chief justices undertake. We discuss these interactions more below but note here that they can be contentious. In 2019, for example, Alaska governor Mike Dunleavy’s proposed budget struck the judiciary’s funding request by $334,700 because “it was equivalent to state spending on abortion services required by a series of rulings from the Alaska Supreme Court” (Reference BrooksBrooks 2020). Chief Justice Joel Bolger responded by noting the state’s “tripartite form of government” and urged Dunleavy to recognize the judiciary’s “right to make its request to the legislature” (Reference BolgerBolger 2019). Also in 2019, Chief Justice Maureen O’Connor of the Ohio Supreme Court argued against a proposed criminal justice bill in a letter to legislators that began, “You may think it unprecedented to receive a letter from me, as Chief Justice, that addresses my concerns about [this bill]. In reality, it is my duty to speak about matters that affect the administration of justice” (see Reference BoehmBoehm 2019).

Notwithstanding the centrality of chief justices in the study of judicial and state politics, little is known about what determines their selection. Reference Vining, Wilhelm and WanlessVining, Wilhelm, and Wanless (2019) examine the conditions under which associate justices run for election to be chief. While electing chief justices is procedurally transparent, peer-vote selections are opaque (but see Reference Langer, McMullen, Ray and StrattonLanger et al. 2003; Reference Norris and TankersleyNorris and Tankersley 2018). Courts selecting leaders by peer vote typically issue press releases announcing winners but offer little or no information about the process. With respect to voting, for example, public information requests to states in our sample revealed that none disclose information about vote divisions. Footnote 2 As a result of this opaqueness, institutional performance is difficult to evaluate.

Chief Justice Peer Votes

We develop a theory of chief justice selection by peer vote that emphasizes candidate characteristics relative to peers. Specifically, we highlight the potential importance of experience, bias, and politics in shaping selection outcomes. Our theoretical perspective draws from an interdisciplinary literature on leader selection in the public and private sectors. We also use insights from the literature on organizational leader selection and cognate research on the psychology of group decision making.

Experience

Political leaders are often selected based on experience (e.g., Reference Chiru and GherghinaChiru and Gherghina 2017). There are several reasons for this practice. As an initial matter, it is common to associate experience with expertise (Reference Rusbult, Insko and LinRusbult, Insko, and Lin 1995). To the extent these concepts overlap, choosing the most experienced candidate may benefit institutional performance. Allocating rewards based on experience can also enhance external perceptions of legitimacy (Reference FischerFischer 2008, 168–69). Internally, relying on experience values longevity and incentivizes stability. It also mitigates group conflict by minimizing decision costs and reducing discretion that may otherwise facilitate biased decision making. Avoiding conflict over small-group leadership choices is important for managing collegial relations, particularly because common dispute resolution mechanisms such as bargaining and third-party interventions are less applicable in these contexts (Reference Baron, Murphy and SaalBaron 1990).

The effect of experience on leader selection may be nonlinear. Evidence on acclimation suggests new judges sometimes face a steep learning curve (Reference BoyeaBoyea 2010; Reference Hettinger, Lindquist and MartinekHettinger, Lindquist, and Martinek 2003; Reference Hurwitz and StefkoHurwitz and Stefko 2004; but see Reference Heck and HallHeck and Hall 1981). In light of this potential performance deficit, relatively inexperienced judges are unlikely to be considered good candidates for leadership positions. At least initially, the probability of selection should be expected to increase with additional years of service. This experience allows for more effective peer evaluation, increased political visibility, and enhanced skill concerning the court’s internal and external workings. However, there may be diminishing and eventually negative returns to additional experience. Longer tenure, for example, may increase the threat of reduced mental capacity and declining performance. And of course it increases the probability of institutional exit (Reference BoyeaBoyea 2011; Reference Curry and HurwitzCurry and Hurwitz 2016; Reference HallM. G. Hall 2001). As a result, the probability of being selected for a state judgeship increases with additional years of experience before steadily declining (Reference GoelzhauserGoelzhauser 2018b). Likewise, additional years of experience may initially increase the probability of being selected chief, with diminishing and eventually negative returns.

Political officials may also value seniority as an objective candidate sorting heuristic. There is evidence, for example, that the practice of assigning congressional committee chairs based on seniority persisted even after the norm ostensibly eroded (Reference Deering and WahlbeckDeering and Wahlbeck 2006; Reference Polsby, Gallaher and RundquistPolsby, Gallaher, and Rundquist 1969; but see Reference CannCann 2008). In the judicial context, seniority norms for rotating leaders are often conditioned by prior service. Federal law dictates that the most senior circuit court judge who has not been chief assumes office at the end of an incumbent’s seven-year term, and numerous states have similar rules. Absent such a rule under choice by peer vote, default to a seniority norm would be understandable as a way to manage group conflict. Seniority is likely to be one of the few objective sources of overlapping consensus (Reference RawlsRawls 1987) concerning valued leader characteristics. As a proxy for leader quality, seniority is over- and under-inclusive, but that may be an acceptable tradeoff when it allows heterogeneous group members to reach an incompletely theorized agreement (Reference SunsteinSunstein 1995) about valued characteristics rather than arguing from first principles during each selection event or depleting group capital by making contentious choices. Moreover, default to seniority rotation would be sustainable if group members believe they will benefit from the norm in the future.

-

Experience Hypothesis: The probability of being selected chief increases with additional years of service before declining.

-

Seniority Hypothesis: The most senior justice who has not been chief is most likely to be selected chief.

Bias

Discretionary voting institutions may disadvantage members of marginalized groups such as women and people of color. The evidence from legislatures is mixed. A recent study finds no evidence that women and people of color are differentially excluded from legislative leadership positions (Reference Hansen and ClarkHansen and Clark 2020). With respect to committee type, however, one study finds that women are as likely to chair “important fiscal committees” (Reference DarcyDarcy 1996, 888), while another suggests they are less likely to chair politically prestigious committees (Reference Fouirnaies, Hall and PaysonFouirnaies et al. 2018). Women in the British House of Commons are more likely to be voted committee chairs by peers (Reference O’BrienO’Brien 2012). More generally, there is substantial evidence that women are less likely to be promoted to workplace leadership positions (e.g., Reference Blau and DevaroBlau and Devaro 2007; Reference Smith, Smith and VernerSmith, Smith, and Verner 2013; Reference Yap and KonradYap and Konrad 2009). As for mechanisms, role congruity theory demonstrates that women are often perceived to be less effective leaders as a result of purportedly lacking traits commonly associated with effective leadership such as aggressiveness and assertiveness (Reference Eagly and KarauEagly and Karau 2002). Moreover, adherence to gender stereotypes leads to biased evaluations of women, resulting in a competence discount that hinders workplace advancement (Reference HeilmanHeilman 2001).

Mirroring other societal contexts, women and people of color have long endured formal and informal barriers to equality in the legal profession. Although many explicitly disadvantageous rules such as prohibitions on women practicing law have been eliminated in the United States, subtler forms of discrimination persist. Examples of relevant empirical findings concerning law and courts include evidence that attorneys who are women or people of color are more likely to report being treated unfairly (Reference Collins, Dumas and MoyerCollins, Dumas, and Moyer 2017); judges who are women or people of color receive worse performance evaluations from members of the legal community (Reference GillGill 2014; Reference Gill, Lazos and WatersGill, Lazos, and Waters 2011); women are less likely to be advanced by nominating commissions under merit selection (Reference GoelzhauserGoelzhauser 2018b); federal district court nominees who are black or women receive lower competence ratings from the American Bar Association (Reference SenSen 2014); and black federal district court judges are more likely to be overturned on appeal (Reference SenSen 2015). Footnote 3

Bias may be explicit or implicit. Implicit bias arises from discriminatory attitudes and stereotypes that operate outside of conscious awareness. Examining judicial performance evaluations, Reference GillGill (2014, 276–77) demonstrates that implicit bias may be particularly prevalent “in hiring-related decisions where the characteristics that are stereotypical for the job are at odds with the gender or race stereotype,” and where “subjective, vague, or abstract evaluation criteria” allow for evaluatory gap filling based on attitudes and stereotypes. The chief justice position, for example, may be associated with increased time demands, and women who are attorneys are perceived to be less committed to the time-intensive nature of high-profile legal employment (Reference Rivera and TilcsikRivera and Tilcsik 2016). Being chief may also be associated with a need for assertiveness that women are perceived to be less likely to possess and judged more negatively for exhibiting (Reference Park, Yaden, Schwartz, Kern, Eichstaedt, Kosinski, Stillwell, Ungar and SeligmanPark et al. 2016). Explicit bias can be difficult to detect, but former Wisconsin Supreme Court justice David Prosser made headlines when he told his colleague Shirley Abrahamson, “You are a total bitch,” while Justice Ann Walsh Bradley reported that Prosser “put his hands around my neck, holding my neck as though he were going to choke me” (Reference CaplanCaplan 2015).

Racial bias allegations were raised in a Louisiana chief justice selection dispute. Some historical context is essential for understanding the dispute. At one point, the predominantly black Orleans Parish had been combined with three predominantly white parishes to elect two Louisiana Supreme Court justices while other parishes constituted single-member districts. Finding it “particularly significant that no black person has ever been elected to the Louisiana Supreme Court” (Chisholm v. Edwards 1988, 1,058), the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit held that the state’s districting scheme violated the Voting Rights Act by diluting the black vote in Orleans Parish. To satisfy a consent decree, Louisiana created a new Court of Appeal seat with the elected judge to be assigned to the Supreme Court, increasing the latter’s size from seven to eight (Perschall v. Louisiana 1997). Footnote 4 Nobody received a majority in the ensuing three-person Democratic primary, resulting in a planned runoff between the white first-round winner and a black second-place candidate. Footnote 5 Before the runoff, however, pressure mounted to ensure that a black judge filled the position in light of its purpose, and the white first-round winner withdrew arguing that her candidacy “threatened to ‘permanently scar’ race relations in New Orleans” (Orlando Sentinel 1994).

Ultimately, Bernette Joshua Johnson, a black woman, was elected to the newly created Court of Appeals seat in 1994 and immediately assigned by statute to the Louisiana Supreme Court, becoming the first woman of color to hold such a position (Reference Goelzhauser, Solberg, Disascro and WaltenburgGoelzhauser 2020). Several months later, a white man named Jeffrey Victory was elected to the Supreme Court. Justice Johnson ran unopposed for reelection to a regular Supreme Court seat after redistricting in 2000. As part of that redistricting, the number of high court seats was reduced back to seven and a law passed stipulating that “[a]ny tenure on the supreme court gained by [the judge elected to fill this position] while so assigned to the supreme court shall be credited to such judge” (see Chisholm v. Jindal 2012, 706). Notwithstanding this provision, a dispute later arose concerning whether Johnson or Victory was entitled to be chief justice under the state’s seniority rotation rule. Arguing that she was “being challenged because she’s an African-American” (quoted in Reference Campbell-RockCampbell-Rock 2012), Johnson filed suit in federal court, where a judge subsequently ruled that Johnson’s tenure began with her initial election and that she was therefore entitled to be chief justice. Although this anecdote arises under a different chief justice selection system, it illustrates the high stakes associated with position allocation and how bias can impact collegial court decision making. Footnote 6

-

Women Hypothesis: Women are less likely to be selected chief.

-

People of Color Hypothesis: People of color are less likely to be selected chief.

Politics

Political dynamics are important for leader selection. In the formative paper on chief justice selection by peer vote, Reference Langer, McMullen, Ray and StrattonLanger et al. (2003) develop a theory that emphasizes internal and external political dynamics. Internal political dynamics may be paramount in discretionary chief justice selections. In addition to being administrative leader, state supreme court chief justices often exercise opinion assignment authority (Reference HallM. G. Hall 1990; Reference Hughes, Wilhelm and ViningHughes, Wilhelm, and Vining 2015; Reference Kaheny, Szmer and ChristensenKaheny, Szmer, and Christensen 2019). Moreover, they can influence the production of separate opinions (Reference Brace and HallBrace and Hall 1990; Reference Hall and BraceM. G. Hall and Brace 1992; Reference Hall and WindettM. E. K. Hall and Windett 2016), which may impact perceptions of legitimacy. As Reference Langer, McMullen, Ray and StrattonLanger et al. (2003, 660) put it, “associate justices want a chief justice who has a moderate ideological tenor,” and “the median member is presumed least harmful to the other justices’ policy goals.” Footnote 7 Consistent with this expectation, they find that justices are less likely to be selected chief as their ideal point diverges from the court’s median.

In addition to revisiting this hypothesis, we build on Reference Langer, McMullen, Ray and StrattonLanger et al.’s (2003) theory by considering collegiality as an important manifestation of internal political dynamics. Specifically, we consider the propensity to dissent. As a former chief judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit once explained, “Maintaining collegiality [on multimember courts] requires continuous efforts at minimizing sources of irritation—such as dissents” (Reference PosnerPosner [2008] 2010, 33). Or as U.S. Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis put it to then-Professor Felix Frankfurter, the “great difficulty of all group action of course is when and what concessions to make. Can’t always dissent” (quoted in Reference UrofskyUrofsky 1985, 309). Although dissents can generate long-term legal change, they can also fray short-term relations by undermining a court’s positions and generating more work for opinion writers (Reference Epstein, Landes and PosnerEpstein, Landes, and Posner 2013). Footnote 8 In 2015, Wisconsin altered state law to allow for chief justice selection by peer vote in order to oust longtime Chief Justice Shirley Abrahamson. Although the decision was politically motivated, some colleagues lamented her frequent dissents, with former Justice Louis Butler noting, “I was looking to build majorities while I think she was trying to set forth her view in the law,” adding, “She always saw herself as a one of seven and had the right to do that” (Reference FerralFerral 2016).

There are several mechanisms by which a higher dissent may lead to a lower likelihood of being selected chief justice. First, consistent with Posner’s irritation observation, those who do not “go along to get along” may not be well liked. More dissents may also signal a lack of ability or desire to foster collegial relations on a multimember court. Given that “the chief justice is a figure of authority on a state supreme court” (Reference Vining and WilhelmVining and Wilhelm 2010, 712), there may also be concern about the public perception of the chief seeming out of step with the court majority. Last, as exemplified by Chief Justice Harlan Fiske Stone’s purported influence on the U.S. Supreme Court (Reference Corley, Steigerwalt and WardCorley, Steigerwalt, and Ward 2013, 29–32; Reference HaynieHaynie 1992; Reference Walker, Epstein and DixonWalker, Epstein, and Dixon 1988), there may be concern that a leader who sets an institution’s tone by frequently dissenting generates spillover effects that have deleterious consequences for collegiality and performance.

Externally, chief justices:

advise policymakers about the needs or desires of the justice system in addition to overseeing budget requests for the courts, judicial salaries and staff, case management, judicial procedure, indigent legal services, and the treatment of the criminally accused, among other issues. (Reference Wilhelm, Vining, Boldt and TrochessetWilhelm et al. 2019, 159)

In Iowa, for example, former Chief Justice Mark Cady lobbied state legislators for a funding restoration to prevent court closures and reduced services, to which one legislator replied, “We will do our damnedest to get you to where you need to be” (Reference RussellRussell 2017). And in Tennessee, Chief Justice Jeff Bivens expressed interest in criminal justice reform by noting, “I am proud to say that I am in talks with the governor, [house speaker, lieutenant governor], and chairmen of the legislative committees,” adding, “We are very close to announcing the formation of a statewide task force that will undertake this effort” (Reference BennettBennett 2017). Reference Wilhelm, Vining, Boldt and BlackWilhelm et al. (2020) find that state legislatures are less likely to approve judicial requests as the ideological distance between them and the chief justice increases. As a result of external political dynamics, Reference Langer, McMullen, Ray and StrattonLanger et al. (2003, 660) argue that “the ability of the chief justice to create and maintain good relations with [the legislature and governor] affects institutional goals.” Consistent with this expectation, they find that justices who are ideologically distant from important state officials are less likely to be selected chief by their peers. We expect the same.

-

Internal Compatibility Hypothesis: Justices are less likely to be selected chief as their ideological divergence from the court’s median increases.

-

Dissent Hypothesis: Justices are less likely to be selected chief as their propensity to dissent increases.

-

External Compatibility Hypothesis: Justices are less likely to be selected chief as their ideological divergence from executive and legislative officials increases.

Empirical Analysis

Modeling Strategy

Previous research analyzing chief justice selections by peer vote employ duration analysis, though with fundamentally different approaches. Reference Norris and TankersleyNorris and Tankersley (2018) analyze the time until peer-vote states seat a woman as chief justice from 1970 through 2008, with the risk set defined as state-years in which there is a peer vote. With state-year as the unit of analysis, this approach emphasizes state-level as opposed to individual-level variation. Indeed, with only one observation per state-year, this approach does not allow for examining the impact of candidate characteristics on selection outcomes. Reference Langer, McMullen, Ray and StrattonLanger et al. (2003) use a sample of state supreme court justices who first came to the bench between 1970 and 1996 to model the time until they were first voted chief by their peers. The unit of analysis is the justice-year, and the risk set is defined as state-years for justices eligible to win a peer-vote contest.

Our approach is different. The use of duration analysis in previous research indicates that the primary interest was in modeling the time until an event occurs—either selection of a woman (Reference Norris and TankersleyNorris and Tankersley 2018) or any eligible justice (Reference Langer, McMullen, Ray and StrattonLanger et al. 2003). In contrast, we are interested in understanding whether certain candidate characteristics are associated with chief justice selections from fixed choice sets. Although Reference Langer, McMullen, Ray and StrattonLanger et al. (2003) include two individual-level predictors in their analysis, their modeling strategy compares every justice in the sample to one another (across states and time) rather than comparing justices to colleagues on the same court at the time of selection. In contrast, similar to methodological advances in the legislative context (Reference CannCann 2008), we are interested in the outcomes of particular peer-vote contests, examining chief justice selections from the pool of sitting justices on a court who collectively comprise the choice set at a given point in time.

Social scientists are often interested in modeling selection from fixed choice sets. In the canonical paper, Reference McFadden and ZarembkaMcFadden (1973) analyzes shopping behavior, including transportation mode and destination. In political science, scholars have analyzed phenomena such as selection of a coalition government (Reference Martin and StevensonMartin and Stevenson 2001) and legislative party switching (Reference DesposatoDesposato 2006). With respect to judicial politics, this modeling strategy has been employed to understand opinion assignment (Reference Farhang, Kastellec and WawroFarhang, Kastellec, and Wawro 2015), panel assignment (Reference Hausegger and HaynieHausegger and Haynie 2003), and merit selection (Reference GoelzhauserGoelzhauser 2018b). As with those institutional settings, we are interested in modeling the selection of a particular individual from a fixed choice set rather than pooling justices across states and time. Thus, our estimation strategy leverages within-contest variation for identification.

Data and Measurement

Our original data span 1965 through 2016 and includes more than 200 selection events across 18 states and 19 apex courts that select chief justices by peer vote. Footnote 9 For each contest, the outcome variable is scored one for the justice selected chief and zero for others in the choice set. Although conditional logit is well suited for modeling selection from fixed choice sets, marginal effects can only be estimated with the fixed effect set equal to zero, which potentially generates misleading and meaningless quantities of interest (Reference BeckBeck 2015; Reference Karaca-Mandic, Norton and DowdKaraca-Mandic, Norton, and Dowd 2012; Reference KatzKatz 2001, 380). Alternatively, standard models with grouping-unit fixed effects perform well in simulations as conditional logit proxies while allowing for the recovery of meaningful substantive effects (Reference BeckBeck 2015; Reference CoupeCoupe 2005; Reference KatzKatz 2001). As a result, we present results from a logit model with contest fixed effects. Table A1 in the appendix displays results from conditional logit and linear probability model specifications. The results are similar.

Consistent with our hypotheses, we include the following explanatory variables. Our seniority variable is scored one for the longest serving justice who has not been chief and zero otherwise. To account for aggregate experience, we include variables counting number of years served on the apex court and number of years squared. The quadratic term permits testing for concavity. The discrimination hypotheses are evaluated with an indicator scored one for women and zero otherwise, and a second scored one for justices of color and zero otherwise. We account for partisan dynamics with three measures available for the length of the sample period. First, we include an indicator scored one for justices who are copartisans with the court median and zero otherwise. Second, we include an indicator scored one for justices who are copartisans with a unified state legislature and zero otherwise. Third, we include an indicator scored one for justices who are copartisans with the governor and zero otherwise. The robustness section considers alternative but time-limited measures. Last, we use opinion authorship data from Nexis Uni to measure a justice’s propensity to dissent. Specifically, we divide the total number of majority and dissenting opinions written or joined the previous year by the total number of dissenting opinions written or joined that year, multiplying quotients by 100 to generate percentages.

One of the benefits of our modeling strategy is that contest fixed effects sweep up observable and unobservable intra-contest heterogeneity. Thus, as (Reference Farhang, Kastellec and Wawro2015, S74) note in an analogous setting, “the model implicitly accounts for any factors that do not vary within a [contest] (essentially holding them constant) even though we do not explicitly estimate parameters for such variables.” In our context, the contest fixed effects account for state-level variables such as opinion assignment rules, court professionalism, and retention mechanisms that may be correlated with candidate characteristics and selection outcomes. As a result, the threat of omitted variable bias is diminished. Moreover, this approach accounts for time-varying effects with respect to predictors such as gender and race since effects are calculated based on intra-contest win probabilities (cf. Reference Farhang, Kastellec and WawroFarhang, Kastellec, and Wawro 2015, S74). In short, this estimation strategy accounts for any factor that is constant within a given contest. Leveraging within-contest variation to identify the effect of individual-level characteristics on the probability of selection lends credibility to the resulting inferences.

Results

Figure 1 plots estimated coefficients from a logistic regression with contest fixed effects analyzing chief justice selections by peer vote. Table A1 in the appendix displays estimated coefficients and standard errors, which are clustered by contest. As noted previously, the appendix also includes results from conditional logit and linear probability model specifications. Contest fixed effects and the intercept are excluded from Figure 1. Overall, the model fit is good. The area under the ROC curve, which indicates the proportion of correct classifications from a random draw of [0,1] pairs on the outcome variable, is 0.83. Moreover, the model reduces classification errors by 15%. Support for the hypotheses is mixed.

Figure 1. Chief justice selection by peer vote.

There is evidence that seniority and experience are associated with selection outcomes. Consistent with expectations, the most senior justice who has not been chief is more likely to be voted chief. The effect is large, with a move into this position associated with an increase in the probability of selection from 0.07 [0.05, 0.09] to 0.47 [0.38, 0.56], a difference of 0.40 [0.31, 0.50] (95% confidence intervals are in brackets). Thus, the peer-vote rule regularly defaults to seniority rotation. This result is understandable given that such a norm would diminish interpersonal tensions and allow for equitable distribution of the designation over time.

Years of apex court experience is also associated with selection outcomes. Moving years of experience from one standard deviation below its mean to one standard deviation above is associated with an increase in the probability of selection from 0.05 [0.03, 0.07] to 0.20 [0.15, 0.25], a difference of 0.16 [0.10, 0.22] (apparent arithmetic irregularities are due to rounding). As predicted, however, the effect is nonlinear. Figure 2 plots the probability of being voted chief as a function of years of experience. The probability of selection increases steadily through fifteen years of experience, at which point it declines steadily. At twenty-four years of experience, the lower 95% confidence bound crosses zero. This concave relationship demonstrates the change from positive to negative returns on experience over time.

Figure 2. Predicted probability of selection by years of experience.

Political dynamics are largely unassociated with selection outcomes. The estimated coefficients for the partisan divergence variables are not statistically distinguishable from zero. Dissent frequency, however, is negatively associated with selection outcomes as expected. Figure 3 plots the probability of being voted chief as a function of dissent frequency. Moving the dissent propensity variable from one standard deviation below its mean to one standard deviation above is associated with a decrease in the probability of selection from 0.18 [0.13, 0.23] to 0.05 [0.02, 0.08], a difference of -0.13 [-0.19, -0.06]. Unfortunately, we cannot isolate the mechanism with this sample. In addition to the possibilities discussed previously, dissent frequency may capture an aspect of preference divergence that is not fully absorbed by existing ideal point measures. Nonetheless, the widespread view of dissents as a collegial annoyance and threat to external goodwill offers some justification for why judges may prefer to select more conciliatory leaders.

Figure 3. Predicted probability of selection by dissent frequency.

The results for women and people of color suggest that members of these marginalized groups are not differentially likely to be voted chief by their peers. It is worth reflecting on why we do not observe discrimination in this context when it is evident in others, such as judicial performance evaluations (Reference GillGill 2014) and nominating commission decisions (Reference GoelzhauserGoelzhauser 2018b). Two results presented here may play into the lack of observed bias against women and people of color. First, defaulting to a seniority rotation norm may help reduce decision-making bias. Second, reliance on dissenting behavior may diminish the effect of implicit bias. There is evidence, for example, that judges who are women and people of color are less likely to dissent (Reference Haire and MoyerHaire and Moyer 2015; Reference Hettinger, Lindquist and MartinekHettinger, Lindquist, and Martinek 2003; Reference Szmer, Christensen and KahenySzmer, Christensen, and Kaheny 2015). If this is true for the women and people of color in our sample, the lower dissent propensity may counteract bias.

With respect to judicial performance evaluators and nominating commissioners, there is also a relative lack of accountability compared to the collegial court context. Decision makers in the former are largely insulated from blowback by design mechanisms that obscure individual choices. It is notable, for example, that there is no evidence of discrimination in gubernatorial selections under merit selection, where choices from the nominee set are often publicly observed and attributable to a single person (Reference GoelzhauserGoelzhauser 2018b). In the relatively small-group context of a collegial court, judges may be held responsible for biased outcomes such as repeatedly passing over women and people of color even when votes are ostensibly confidential. At a minimum, there is likely to be internal recognition of such patterns, which could generate group conflict.

Robustness

Table A2 in the appendix presents results from a variety of robustness checks. As an initial matter, we proxy for skill with four control variables. Footnote 10 First, we adopt Reference SenSen’s (2014) ordered ranking of law school quality based on U.S. News & World Report rankings: 1 = schools ranked 101+, 2 = schools ranked 100–76, 3 = schools ranked 75–51, 4 = schools ranked 50–26, 5 = schools ranked 25–15, and 6 = schools ranked in the top-14. Second, we include a law school honors variable scored one if a justice graduated law school with honors, served on the school’s flagship law review, or had a post-graduation judicial clerkship, and zero otherwise. Third, to account for political skill and connections that may enhance one’s value as chief, we include an indicator scored one for justices who previously served in Congress, a state legislature, or as state attorney general, and zero otherwise. Footnote 11 Fourth, we use external opinion citations data from Reference Choi, Gulati and PosnerChoi, Gulati, and Posner (2010). For judges serving in their sample from 1998 through 2000, we used factor analysis to create a latent citations score combing the natural log (plus a start value = 0.1) of citations from out-of-state apex courts, lower federal courts, the U.S. Supreme Court, and law reviews. Results are presented in Models 1 through 3 in Table A2. Including these controls does not change the primary results and none of the estimated coefficients for the added variables are statistically distinguishable from zero.

Next, we include additional controls for variation in previous service as chief justice. First, we include an indicator scored one for the incumbent chief justice and zero otherwise. Second, we include a variable scoring the number of times a justice previously served as chief. Model 4 in Table A2 presents results. Including these variables does not change the primary results and the estimated coefficient for the number of times having served as chief is not statistically distinguishable from zero. The estimated coefficient for the incumbent chief justice variable is, however, negative and statistically distinguishable from zero. Substantively, being the incumbent chief justice is associated with a decrease in the probability of being voted chief from 0.11 [0.08, 0.13] to 0.05 [0.02, 0.09], a difference of -0.05 [-0.10, -0.01]. This result is consistent with the finding that peer votes often default to rotation.

We also fit models with alternative ideological divergence measures. Although we use party affiliation as a divergence proxy in the primary model to cover our temporal period, more nuanced measures can be used on sample subsets. We include three alternative measures of the ideological distance between a justice and the court median. First, following Reference Langer, McMullen, Ray and StrattonLanger et al. (2003), we use Reference Brace, Langer and HallBrace, Langer, and Hall’s (2000) party-adjusted judge ideology (PAJID) scores to capture the absolute value of the difference in ideal points between a justice and the court median. Second, we calculate the same score using Reference Bonica and WoodruffBonica and Woodruff’s (2015) campaign finance (CF) scores based on campaign finance records. Third, we use Reference Windett, Harden and HallWindett, Harden, and Hall’s (2015) item response theory (IRT) scores combining Reference Bonica and WoodruffBonica and Woodruff’s (2015) measure with item response estimates from case votes. Models 5 through 7 in Table A2 present results.

Figure 4 plots predicted probabilities of chief justice selection over the range of values for each divergence measure. Contrary to what Reference Langer, McMullen, Ray and StrattonLanger et al. (2003) find with an alternative sample and estimation strategy, the estimated coefficient using PAJID scores to measure divergence is not statistically distinguishable from zero. Likewise, the estimated coefficient for the IRT divergence variable is not distinguishable from zero. Using CF scores, however, yields a result consistent with expectations. A change from one standard deviation below mean divergence to one standard deviation above is associated with a decrease in the probability of being selected from 0.11 [0.07, 0.15] to 0.07 [0.04, 0.10], a change of -0.04 [-0.08, <-0.01]. Although the effect size is small relative to seniority rotation and dissent frequency, this result provides some evidence that political dynamics are associated with chief justice selections.

Figure 4. Justice-court median ideological divergence.

PAJID and CF scores can be used to measure two types of external divergence. Following Reference Langer, McMullen, Ray and StrattonLanger et al. (2003), we measure ideological divergence between a justice and the state’s political elite, leveraging the fact that PAJID scores are scaled on a common dimension with Reference Berry, Ringquist, Fording and HansonBerry et al’s (1988) state elite ideology measure. Furthermore, using CF scores we measure ideological divergence between a justice and the sitting governor (Reference BonicaBonica 2014). Models 5 and 6 in Table A2 present results. Figure 5 plots predicted probabilities of selection over sample values for each external divergence measure. Contrary to what Reference Langer, McMullen, Ray and StrattonLanger et al. (2003) find with an alternative sample and estimation strategy, the estimated coefficient for justice-elite divergence is not statistically distinguishable from zero. Counterintuitively, the estimated coefficient for justice-governor divergence is positive and statistically distinguishable from zero. Moving from one standard deviation below mean divergence to one standard deviation above is associated with an increase in the probability of being selected from 0.06 [0.03, 0.09] to 0.13 [0.09, 0.17], a change of 0.07 [0.02, 0.12]. Other results are the same across specifications except that the estimated coefficient for dissent propensity is indistinguishable from zero in the IRT model, where data availability reduces the sample size by about half.

Figure 5. External ideological divergence.

Last, in an supplemental appendix we consider whether certain state-level institutional design choices moderate the effect of our theoretically relevant choice-level variables. Specifically, we consider chief justice opinion assignment power, contestable elections, court professionalism, court size, and secret internal voting procedures. Footnote 12 As noted previously, state-level predictors cannot be independently included in these models because they are perfectly collinear with the contest fixed effects. They can, however, be included as interactions with choice-level predictors (Reference AllisonAllison 2009; see also Reference Farhang, Kastellec and WawroFarhang, Kastellec, and Wawro 2015; Reference GoelzhauserGoelzhauser 2018b). In general, the primary results are stable across specifications. Footnote 13 Moreover, the primary specification presented here generally offers the best model fit. We note two results. First, unlike Reference Langer, McMullen, Ray and StrattonLanger et al. (2003) we find no evidence that unilateral opinion assignment power conditions the effect of partisan considerations on chief justice selections. Second, contestable elections diminish and court size enhances the positive effect of being the senior justice who has not been chief on the probability of selection. Footnote 14

Conclusion

Which characteristics do state supreme court justices prioritize when selecting leaders? Although a plurality of state supreme courts select chief justices by peer vote, little is known about why some justices are chosen over others. We develop a theory of chief justice selection that accounts for experience, bias, and politics. Using within-contest evidence from more than fifty years of chief justice selection events, we find that contests often default to seniority rotation. The impact of politics is mixed. Contrary to previous findings, we observe little evidence that ideological divergence from the court median or state officials reduces the probability of being voted chief. Justices who dissent more relative to their peers are, however, disadvantaged. We find no evidence of discrimination against women or people of color.

This project has implications for the broader study of political leader choice. As an initial matter, our theory of leader selection can be transported to other institutional contexts. With respect to marginalized groups, the results contribute to a bundle of conflicting evidence across settings finding that women and people of color may be favored, disfavored, or on no different footing when it comes to leader selection. Not surprisingly, experience matters across institutional settings. In selecting congressional committee chairs, however, there is evidence that a once-dominant seniority norm eroded in favor of partisan considerations (Reference CannCann 2008). In contrast, we find that a seniority norm continues to prevail over partisan considerations in state supreme courts. Indeed, unlike in legislatures we find little evidence that partisan considerations motivate leader choices. While we can only speculate about the mechanisms underlying this difference, possibilities include a greater need to encourage partisan loyalty and higher expected policy returns from selecting ideologically congruent legislative leaders.

As for normative judicial implications (cf. Reference Bartels and BonneauBartels and Bonneau 2015), the results presented here contribute to ongoing policy debates about how to select chief justices (Reference McCormickMcCormick 2013; Reference Peppers and OldfatherPeppers and Oldfather 2012; Reference SwaineSwaine 2006). Perhaps the primary policy implication with respect to institutional performance is that peer-vote selection seems to be working well for state supreme courts. Although discretionary selection institutions can generate partisan rancor and increase bias against marginalized groups, state supreme court justices regularly use leader selection power to disperse the chief justice designation on the basis of an objective and largely uncontroversial characteristic. Frequent dissenters, however, are less likely to be selected leader, perhaps because justices are concerned about internal and external relationship maintenance. Formally adopting a seniority rotation rule would be more transparent, but the peer-vote rule may be preferable as a way to reserve a deviation right when doing so is perceived to be in the institution’s best interest.

This project also contributes to the literature on judicial decision making outside of the case context. Understandably, the study of judicial decision making is primarily dedicated to case outcomes such as agenda setting, opinion construction, and merits voting (e.g., Reference Epstein and KnightEpstein and Knight 1998; Reference Hammond, Bonneau and SheehanHammond, Bonneau, and Sheehan 2005; Reference LangerLanger 2002). To fully understand judicial behavior, however, it is important to consider other decision types. Examples of studies considering judicial behavior outside of the case context include decisions to engage in strategic public relations (Reference StatonStaton 2010), seek promotion (Reference GoelzhauserGoelzhauser 2019; Reference Jensen and MartinekJensen and Martinek 2009), retire (Reference Curry and HurwitzCurry and Hurwitz 2016; Reference HallM. G. Hall 2001), use social media (Reference Curry and FixCurry and Fix 2019), and travel (Reference Black, Owens and ArmalyBlack, Owens, and Armaly 2016). More specifically, the results presented here contribute to a burgeoning literature on the determinants of judges choosing from among colleagues for various positions. Existing studies include chief judge selections of visitors on federal circuit court panels (Reference BudziakBudziak 2015), chief justice designations to specialty courts (Reference PalmerPalmer 2016), and chief justice designations to conference committees (Reference ChutkowChutkow 2014). As policymakers continue experimenting with these institutional arrangements, it will be important to understand how judges use this alternative decision-making power.

Much remains for future study. As an initial matter, a comprehensive comparative analysis of institutional performance with respect to chief judge selection requires more information about how various mechanisms function. Reference Vining, Wilhelm and WanlessVining, Wilhelm, and Wanless’s (2019) study of when associate justices run for chief in election states is exemplary in this regard. Additionally, we need more information about the extent to which chief justice selection institutions impact case outcomes (Reference Hall and WindettM. E. K. Hall and Windett 2016; Reference Langer and WilhelmLanger and Wilhelm 2005; Reference Leonard and RossLeonard and Ross 2014). The literature on the consequences of institutional design choices concerning formal powers such as opinion assignment is flourishing (Reference Boyea and Farrar-MyersBoyea and Farrar-Myers 2011; Reference Christensen, Szmer and StritchChristensen, Szmer, and Stritch 2012; Reference HandbergHandberg 1978), but other potentially fruitful avenues of inquiry include how mechanisms shape judicial visibility, administrative performance, and interbranch relations. Consistent with opportunities provided by state-level institutional variation more broadly (Reference Brace, Hall and LangerBrace, Hall, and Langer 2001), studying chief justices comparatively offers a unique window into mechanism design issues with implications for state politics, judicial politics, and political institutions.

Appendix

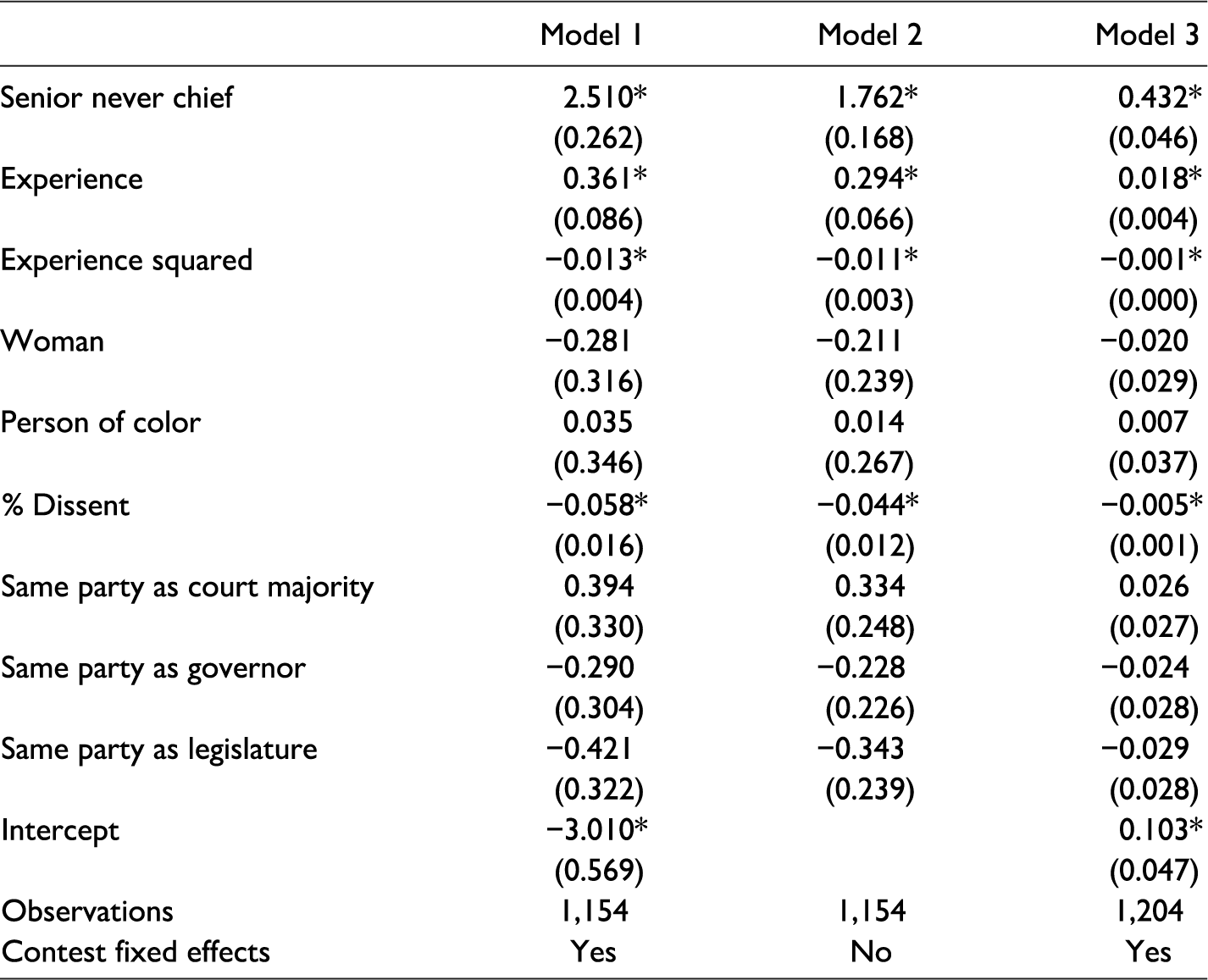

Table A1. Selecting Chiefs by Peer Vote—Alternative Specifications.

Note. Robust standard errors clustered by contest are in parentheses. The outcome variable is an indicator scored 1 if a justice is voted chief and 0 otherwise. Model 1 is fit with logistic regression and includes contest fixed effects, Model 2 is fit with conditional logistic regression using contests as the grouping variable, and Model 3 is fit with a linear probability model and contest fixed effects.

* p < .05.

Table A2. Selecting Chiefs by Peer Vote—Robustness.

Note. Robust standard errors clustered by contest are in parentheses. The outcome variable is an indicator scored 1 if a justice is voted chief and 0 otherwise. The ideological divergence variables in Model 5 use ideal points from Reference Brace, Langer and HallBrace, Langer, and Hall (2000) and Reference Berry, Ringquist, Fording and HansonBerry et al. (1998); the divergence variables in Model 6 use ideal points from Reference BonicaBonica (2014) and Reference Bonica and WoodruffBonica and Woodruff (2015); and the divergence variable in Model 7 uses data from Reference Windett, Harden and HallWindett, Harden, and Hall (2015).

* p < .05.

Authors’ Note

A previous version of this manuscript was presented at the 2018 annual meeting of the American Political Science Association. Thanks to Joseph Smith, conference participants, and the anonymous reviewers for helpful comments.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Greg Goelzhauser https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7770-6728

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Author Biographies

Madelyn Fife is a graduate of Utah State University and the New York University School of Law.

Greg Goelzhauser is an associate professor of political science at Utah State University.

Stephen T. Loertscher is a graduate of Utah State University and student at Brigham Young University Law School.