Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is one of the most prevalent disorders worldwide and is characterized by depressed mood, anhedonia, and changes in appetite, energy, sleep, psychomotor activity, cognition and suicidal ideation.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that the prevalence has increased over the last decade, and by 2015, 4.4% of the world population had the disorder.2 In recent decades, the condition has been one of the first causes of disability; Reference Kessler and Bromet3 its symptoms produce suffering and impairment in functionality and productivity, impacting almost all areas of life.Reference Wiles, Thomas and Abel4

The psychological processes of MDD include components of learning and cognition. The relation of the person to his/her environment depends on previous learning, either by the meaning that is attributed to the events or the behavioral patterns that have been learned to address similar situations.Reference Beck5–Reference Kanter, Busch and Weeks7 Also, life events may function as stressors, influencing patterns of cognition and depressive behavior.Reference Dohrenwend and Dohrenwend8–Reference Liu and Zhang13

According to the cognitive theory of depression, core beliefs (CBs) are formed early in the history of the individual. CBs structure cognitions to give meaning to reality and experiences. CBs are fundamental and absolute perceptions about the self, the world, and the futureReference Beck6, Reference Alford, Beck and Jones14 and dysfunctional negative CBs produce cognitive distortions, feelings, and behaviors that can present themselves as psychiatric disorders, for example, MDD.Reference Osmo, Duran and Wenzel15

Behavioral theory indicates that depressive symptoms arise from a reduction in positive reinforcement and from an increase in aversive stimulation (exposure to stressors).Reference Lewinsohn16 A more aversive environment produces avoidance behaviors or avoidance patterns, which are characteristics of MDD.Reference Ferster17 The avoidance patterns (inactivity, withdrawal, ruminations and self-criticism), combined with a failure to produce a more effective resolution of problems, also limit contact with positive reinforcers, preventing the improvement of mood. In addition, poor personal skills for dealing with aversive situations increase the tendency to remain depressive and engage in avoidance behaviors.Reference Kanter, Busch and Weeks7, Reference Martell, Addis and Jacobson18

MDD may be treated with antidepressants, psychotherapy or the combination of both. For mild MDD, psychotherapy alone is recommended. In moderate to severe cases, the indication is antidepressants associated with psychotherapy.19–Reference Parikh, Quilty and Ravitz21 The mechanism of the action of antidepressants is the increase in the neural availability of certain neurotransmitters, particularly serotonin and noradrenaline.Reference Wiles, Thomas and Abel4, 19, Reference Hollon, DeRubeis and Fawcett22 The limitations of antidepressant treatment include abandoning treatment, side effects in up to 70% of the patients, and lack of complete remission.Reference Wiles, Thomas and Abel4, Reference Hollon, DeRubeis and Fawcett22, Reference Dimidjian, Hollon and Dobson23

The most recommended psychotherapies with higher levels of evidence are cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), behavioral activation (BA), interpersonal therapy, and problem-solving therapy.20, Reference Parikh, Quilty and Ravitz21, Reference Cuijpers, van Straten and Warmerdam24–Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Weitz, Andersson, Hollon and van Straten27 These psychotherapy models are the first options in mild to moderate depression and should be used as an adjunct to drugs in moderate to severe MDD.19, Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Weitz, Andersson, Hollon and van Straten27 The combined use of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy has been suggested to promote a greater symptom reduction relative to antidepressants or psychotherapy alone, in addition to reducing the chances of recurrence.Reference Dimidjian, Hollon and Dobson23, Reference Rosen and Davison28, Reference Gaudiano and Miller29

BA is based on the behavioral theory of depression. Its objective is to identify the relations between behavior and mood, to modify avoidance patterns and to increase behaviors that reduce stressors and increase the amount of environmental positive reinforcements, which produce improvements in mood or have antidepressant effects.Reference Martell, Addis and Jacobson18, Reference Busch, Rusch and Kanter30, Reference Lejuez, Hopko and Acierno31 The growing number of studies involving BA has increased its level of evidence for the treatment of MDD.Reference Parikh, Quilty and Ravitz21, Reference Takagaki, Okamoto and Jinnin32, Reference Abreu and Abreu33 A division of the components of CBT has suggested that BA components of CBT work as well as cognitive mechanisms, such as cognitive restructuring of dysfunctional CBs; Reference Jacobson, Dobson and Truax34 a finding that has been replicated.Reference Dimidjian, Hollon and Dobson23

In the past 60 years, several approaches have been influenced by behavioral and cognitive therapies, such as conventional CBT, a label that encompasses several protocols emphasizing cognitive mediation, Reference Alford, Beck and Jones14, Reference Ruggiero, Spada and Caselli35–Reference Thoma, Pilecki and McKay37 such as schema therapy, compassion-focused therapy, behavioral activation, acceptance and commitment therapy, dialectic behavioral therapy, etc., and, in the last 10 years, trial based-cognitive therapy (TBCT). These psychotherapy models are differentiated by both the theories and the ways of approaching behaviors and thoughts.Reference Ruggiero, Spada and Caselli35, Reference Hayes, Levin and Plumb-Vilardaga 38 TBCT was developed in Brazil, based on Aaron Beck’s CBT model, but with its own case conceptualization and techniques. Among TBCT distinctive features, the following can be underscored: it provides an integrative conceptualization of psychopathology; presents a set of step-by-step cognitive and behavioral techniques; introduces a new systematic approach to change dysfunctional core beliefs; it was designed as an overall easy-to-remember case-formulation model both for the therapist and the patient; integrating cognitive, emotional, and experiential work simultaneously.Reference de Oliveira36, Reference de Oliveira39

TBCT was inspired by the novel “The Trial”, by Franz Kafka, based on the assumption that self-accusations are part of the human existence and correspond to CBs.Reference de Oliveira40 Therefore, TBCT promotes cognitive restructuring at the 3 levels of cognitive conceptualization (automatic thoughts, underlying assumptions and core beliefs) with techniques that mimic a legal process in which the patients are led to assume the roles of defendant, prosecutor, defense attorney and juror, by seeking evidence for and against their CBs conceptualized as self-accusations.Reference de Oliveira, Hemmany and Powell41, Reference De Oliveira42 TBCT has been shown to be effective in social phobia, Reference de Oliveira, Powell and Wenzel43, Reference Caetano, Depreeuw and Papenfuss44 and also to promote modification of CBs in patients presenting with a variety of psychiatric diagnoses.Reference de Oliveira, Powell and Wenzel43, Reference Powell, Oliveira and Seixas45, Reference Delavechia, Velasquez and Duran46 It is therefore important to evaluate its efficacy in reducing depressive symptoms relative to BA, a first-line treatment for MDD.

Thus, given the disability, burden, and increasing prevalence of MDD, the limitations of antidepressant treatment efficacy, and the need for investigations of empirically supported psychotherapies, 47, Reference Leonardi and Meyer48 we decided to compare the efficacy of TBCT and BA relative to antidepressants used alone (Treatment as Usual: TAU) in the treatment of MDD.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

This is a randomized, single-blind clinical trial with 2 psychotherapeutic intervention groups (TBCT and BA), and 1 control group (TAU) for whom pharmacological monotherapy with antidepressants was used to treat MDD. Groups that received psychotherapy maintained continued use of antidepressants. Recruitment occurred through mental health outpatient clinics, residency programs in psychiatry, and dissemination on the radio, newspapers and the internet. Interested parties were contacted via telephone or email and a screening was scheduled with a trained evaluator. Participants considered eligible for randomization were on antidepressant medications for at least 2 months, were between 18 and 60 years old, and met the criteria for MDD according to DSM-IV 1 or ICD-10, assessed with the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI-plus).Reference Amorim49, Reference Lecrubier, Sheehan and Weiller50 The patients also had to have a score greater than 15 on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Reference Dimidjian, Hollon and Dobson23, Reference Hamilton51 or greater than 20 on the Beck Depression Inventory.Reference Dimidjian, Hollon and Dobson23, Reference Beck, Ward and Mendelson52, Reference Cunha 53 Those using mood stabilizing drugs, in psychotherapeutic treatment, with a high risk of suicide (according to the MINI-plus), or diagnosed with bipolar disorder, psychotic disorders, or current abuse of or dependence on psychoactive substances were not included in the study. The recruitment and study occurred between 2015 and 2017, in Salvador, Brazil.

Procedures

The eligible patients underwent a screening to explain the research and provide information on their use of antidepressants and current depressed mood and have the research explained to them. Those selected were referred to an interview where they had access to the informed consent form and were submitted to the initial evaluation. When eligible, participants were assigned by the research coordinator, through a randomization list, to 1 of 3 intervention groups: TBCT, BA or TAU and followed for the 12-week duration of the intervention, 1 session per week. All randomized patients undergoing antidepressant treatment continued to use the medication during the entire research period. Participants who were randomized to psychotherapy were not to have their antidepressant medication doses increased. On the other hand, those on antidepressant monotherapy (TAU group) could have the doses modified at the discretion of their psychiatrists, characterizing this group as having a naturalistic treatment.

Psychotherapists were assigned according to the time compatibility with the patients. The evaluations obtained in all groups at baseline were repeated after 6 weeks (intermediate assessment) and twelve weeks (final evaluation). Patients were removed from the study if they missed 2 consecutive sessions, or a total of 3 sessions or, in the TAU group, if they ceased using the antidepressant medication.

Evaluation tools

Participants were evaluated with inventories, scales and diagnostic interviews at the initial assessment (before the interventions), at week 6 and week 12. All assessments were performed by a trained and blind evaluator.

Diagnostic Interview: The MINI-plus Reference Lecrubier, Sheehan and Weiller50 is a semi-structured interview for the diagnosis of mental disorders. It is compatible with the DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria and validated for the Brazilian population.Reference Amorim49

Severity of depression: The primary measure of depression severity was done with the HAM-D Reference Hamilton51 17-item scale, the answers to which were obtained through a semi-structured interview by means of the GRID-HAM-D, validated for the Brazilian population.Reference Henrique-Araújo, Osório and Ribeiro54 HAM-D is one of the most commonly used scales for MDD severity assessment, Reference Neto, Júnior and von Krakauer Hübner55 where a score from 8 to 15 indicates mild depression, from 16 to 26 indicating moderate depression, and above 27 indicates severe depression.Reference Furukawa56 The GRID-HAM-D was applied in the initial evaluation, in the intermediate evaluation and in the final evaluation. Depression severity was also evaluated by means of the BDI, which, in addition to being administered by an independent evaluator, was also used in all psychotherapy sessions. BDI scores from 14 to 19 indicated mild depression, from 20 to 28 indicated moderate depression, and above 29 indicated severe depression.Reference Beck, Ward and Mendelson52, Reference Cunha 53, Reference Furukawa56

Other measures: In the assessments administered by the independent evaluator, the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)Reference Beck, Epstein and Brown57 was also used, which measured the degree of anxiety, where scores from 10 to 19 indicated mild anxiety, from 20 to 30 indicated moderate anxiety and above 30 indicated severe anxiety.Reference Cunha 53 The Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) assessed how much the clinical condition impacted social functioning in the areas of work/education, social life and home family life/home responsibilities. These scores indicated how much the symptoms had disrupted these aspects of function on a scale of 0 (did not interrupt in any way) to 10 (extremely disturbed).Reference Sheehan58 The Cognitive Distortions Questionnaire (CD-Quest), Reference Kaplan, Morrison and Goldin59, Reference de Oliveira, Seixas and Osorio60 which measured the frequency and intensity of 15 categories of distorted thoughts, had a score that varied from 0 to 75. The quality of life questionnaire (WHOQOL-BREF)61, Reference Fleck, Louzada and Xavier62 evaluated the quality of life through 4 domains: physical, psychological, social and environmental. The higher the percentile score in each domain, the better the quality of life was.

Therapists

Psychotherapeutic interventions were performed by 7 psychologists with at least 6 years of experience in psychotherapy. TBCT and BA were applied by psychologists who were experienced CBT and behavior therapists, with training in TBCT provided by its developer, Irismar Reis de Oliveira. Patients randomized to TAU were cared for by their psychiatrists, with no restrictions to antidepressant dose changes.

Treatments

Trial-based cognitive therapy

TBCT was applied based on the clinical manual, Reference de Oliveira39, Reference De Oliveira42 structured for 12 sessions. This treatment took place over 3 stages. Stage 1 occurred from the first to the fourth session, addressing the first and second levels of cognition, represented by dysfunctional automatic thoughts and underlying assumptions. Stage 2 began in session 5 and worked on the restructuring of dysfunctional negative CBs, the main mechanism of TBCT action. In this phase, the application of Trial I was used to simulate a legal trial in which the patient assumes the roles of the investigated party (inquiry), the defendant, the prosecutor, the defense attorney and the juror. Throughout this procedure, the patient formulates and develops positive CBs, after gathering evidence that does not support the dysfunctional negative CBs. Then, through the “preparation for the appeal” procedure, the patient gathers evidence supporting the new functional positive CB. In phase 3, the final one, which begins in session 10, the patient is led to prosecute the internal prosecutor (inner critic), for having accused him/her abusively and unjustifiably for a long period of time, if not his/her entire life. It is a phase of metacognitive awareness consolidation during which the patient becomes more explicitly aware of his/her own cognitions (metacognition), acquiring more control and attempting to accept and coexist with his/her unpleasant cognitions and emotions.

Behavioral activation

BA was used according to the protocol of Martell, Addis and Jacobson (2001), Reference Martell, Addis and Jacobson18 adapted for 12 sessions. Its application took place over 4 stages. The first was to present the contextual model of depression and to teach the monitoring of the relationship between behavior and mood. The second stage occurred throughout all sessions, and the patient, in addition to being monitored with the activity and mood schedule, planned activities to engage in, according to their goals and values, and increased behaviors with a high probability of obtaining rewarding, enjoyable, and fulfilling consequences, which would result in improving mood. In the third stage, from session 6, patients were encouraged to remain active through problem-solving techniques, as opposed to remaining in avoidance patterns that are part of depressive symptoms. In this stage, avoidance patterns are identified and actions are planned for the patient to remain active instead of avoidant or passive. In the last stage, a treatment review and relapse prevention strategies, such as breaking patterns of avoidance through planned activities, were implemented. The clinician’s manual does not have a session-by-session structure. A typical BA session should cover the agenda, discuss the activities schedule, and plan the activities to be conducted during the week. Interventions for cognitive restructuring were not used.

Statistical analysis

The collected data were tabulated and analyzed with the Software Package for Social Science, version 22.0.63 Demographic and clinical variables were analyzed with the chi-square test for categorical variables (sex, schooling, color or race, dropout rates) and one-way ANOVA for continuous variables (age and baseline scores of all scales). For the missing data, primary (HAM-D) and secondary (BDI, SDS, CD-Quest and WHOQOL) outcomes were analyzed by Intention to Treat (ITT), regardless of the moment of abandonment, Reference Gupta64 and a Multiple Imputation (MI) procedure, Reference Rubin65 with 5 imputed datasets (based on age, sex and group of intervention) and pooled values assuming a missing at random (MAR) data mechanism. A generalized estimating equations (GEE) with auto-regressive first order working matrix, with time as covariate was performed to compare within/mainly effects changes over time (initial, intermediate and final evaluations), over groups (TBCT, BA and TAU). Additionally, in the main effect evaluation, likely interaction effects (time x groups) were evaluated. Between groups effect sizes (d) were obtained through Cohen’s test, in which values above .2, .5 and .8 were respectively considered low, moderate and high.Reference Cohen66 The level of statistical significance established for this study was 0.01, because of the high number of measures. Data of Estimated Marginal Means of groups with MI and the complete-case analysis are available upon request.

This clinical trial was registered at clinicaltrials.org (NCT02624102), and approved by the Health Sciences Institute IRB, at the Federal University of Bahia, Brazil (CAAE 44663315.4.0000.5662).

Results

Participant flow and losses

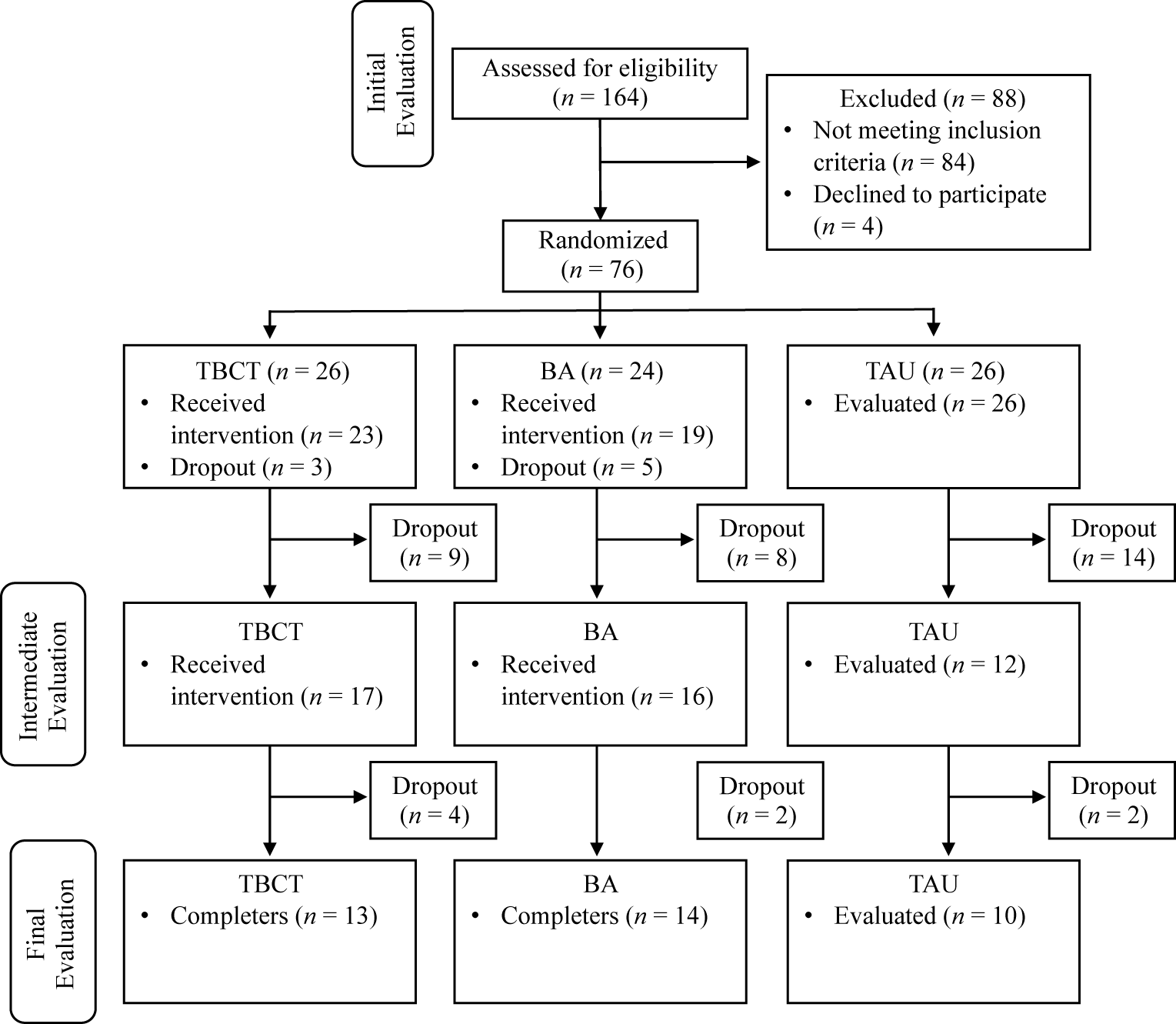

After the screening, a sample of 76 patients was randomized to the 3 conditions (TBCT = 26; BA = 24; TAU = 26). Of the total sample, 31 patients dropped out before the intermediate evaluation (TBCT = 9; BA = 8; TAU = 14), and 39 dropped out before the final evaluation (TBCT = 13, BA = 10, TAU = 16). The proportion of patients who completed the 12 sessions of psychotherapy and the 3 independent evaluations was 50% in TBCT (n = 13), 60.9% in BA (n = 14) and 38.4% in the TAU (n = 10). Fig. 1 shows the flowchart of the study.

Figure 1. Flowchart of study. BA, behavioral activation; TAU, treatment as usual (Antidepressants); TBCT, trial-based cognitive therapy.

The reasons for dropouts in the psychotherapy groups were patients giving up (n = 10), traveling or unavailability for scheduling (n = 7), protocol breakdown and unknown reasons (n = 6). The 61.5% dropout rate (n = 16) by the final evaluation in the TAU group was motivated by patients no longer wanting to participate after being randomized to the drug group (n = 13), and no longer found or not receiving calls (n = 3). The chi-square test indicates a significant difference between dropout rates in the intervention groups and the TAU group [χ²(4) = 10.249, p = .03], because of the large dropout rate in the latter.

Sample characteristics and baseline

The sample was composed of 86% women (n = 66). There were no significant differences between the three groups in social demographical measures: sex [χ²(2) = 1.4, p = .50]; color or race [χ²(4) = 4.1, p = .39]; schooling [χ²(4) = 4.4, p = .36]; employee [χ²(4) = 3.8, p = .43] and civil state [χ²(6) = 8.4, p = .21]. One way ANOVA showed no significant differences between groups in baseline relative to age [F(2, 73) = .30, p = .74] and other clinical measures: HAM-D [F(2, 73) = 1.02, p = .37]; BDI [F(2, 73) = .34, p = .71]; BAI [F(2, 71) = 1.66, p = .20]; SDS [F(2, 72) = .47, p = .63]; and all domains of WHOQOL [F(2, 72) = .191–1.70, p > .05]. Nevertheless, there was a statistically significant difference in CD-Quest between the BA and TAU groups in baseline [F(2, 71) = 4.35, p = .02]. Table 1 shows the clinical and demographic characteristics of the sample.

Table 1. Clinical and demographic characteristics of the sample across groups.

Abbreviations: ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; BA, behavioral activation; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; M, average; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; PD, panic disorder; PMDD, premenstrual dysphoric disorder; SAD, social anxiety disorder; SD, standard deviation; TAU, treatment as usual; TBCT, trial-based cognitive therapy.

* Body dysmorphic disorder, hypochondria, nonspecific anxiety and dysthymia.

** Bupropion, citalopram, clomipramine, duloxetine, paroxetine and nortriptyline.

Main outcomes

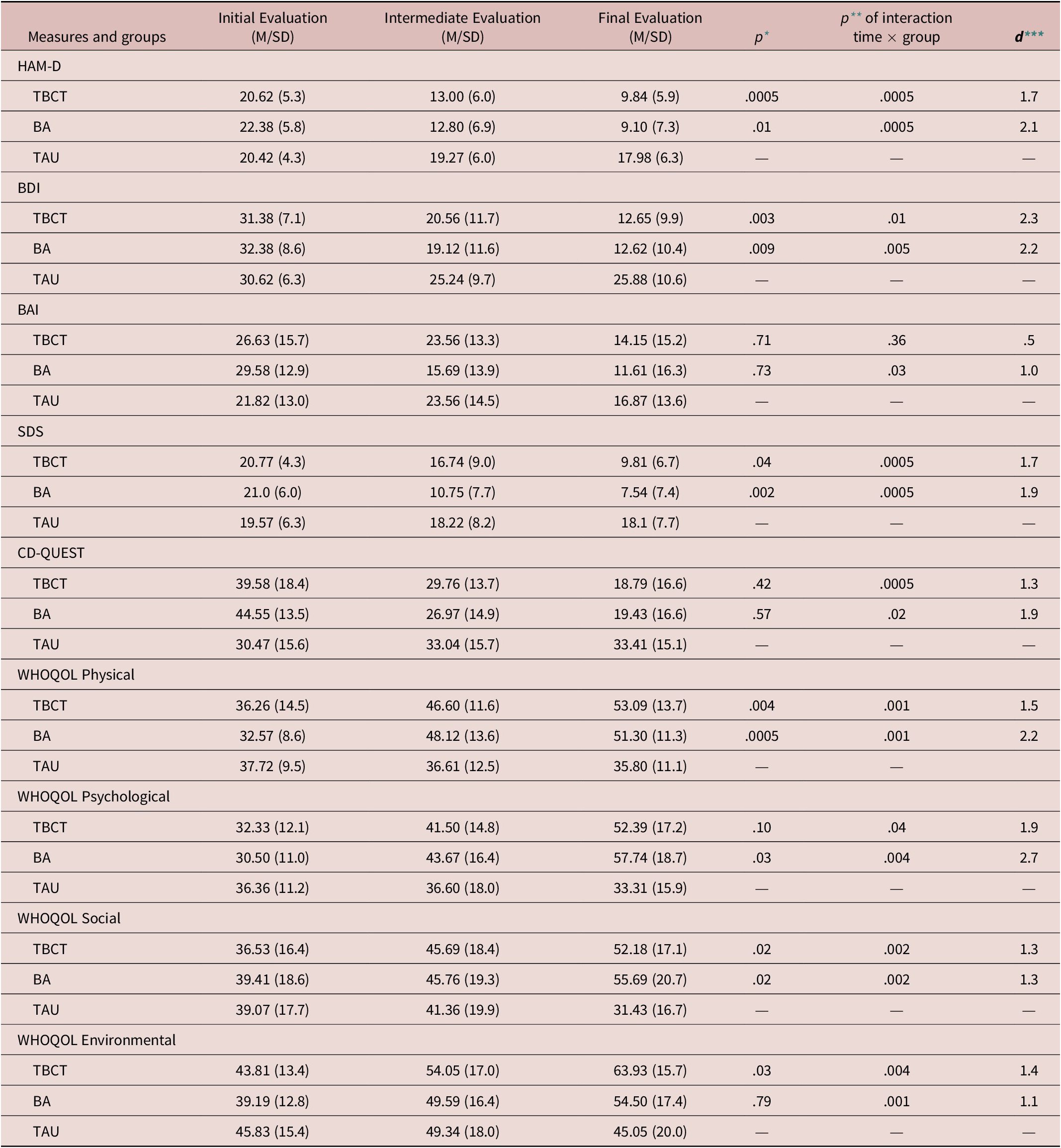

There were statistically significant improvements in all measures for the TBCT and BA groups compared with TAU. Table 2 presents the HAM-D, BDI, BAI, SDS, CD-Quest scores and the 4 WHOQOL domains, according to GEE model and effect sizes.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and inferential group difference analysis over time (TAU reference group) under ITT and MI.

Abbreviations: BA, behavioral activation; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CD-Quest, Inventory of Cognitive Distortions; HAM-D, Hamilton Depression Scale; ITT, intention to treat; MI, multiple imputation; SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale; TAU, treatment as usual; TBTC, trial-based cognitive therapy; WHOQOL, Quality of Life Questionnaire.

* p value for group difference (TAU taken as reference).

** p value for interaction between group × time.

*** Cohen’s d between groups (TAU taken as reference).

Differences within and between groups in primary measure

A generalized estimating equation (GEE) was conducted to compare the differences between and within 3 groups. There was a statistically significant improvement in symptoms for all patients in HAM-D over time [β = –3.964, p < .0005]. This data indicates a decrease of 3.964 points in HAM-D score in each evaluation, regardless of which group.

Parameter estimates comparisons showed a significant difference between the 2 psychotherapies and TAU. For the TBCT group, patients presented more improvement relative to TAU in HAM-D [β = 4.75, p = .0005]. Likewise, the BA group improved more relative to TAU [β = 4.75, p = .01], which indicates a decrease of 4.68–4.75 points in HAM-D in each evaluation for these groups. On the other hand, there was a lack of evidence of difference when TBCT was compared with BA: HAM-D [β = .31, p = .83].

The interaction time × group shows that time had a moderator effect in the reduction of HAM-D scores between groups. TBCT and BA presented a moderator effect of time on intervention compared to TAU: HAM-D [β = –4.535, p < .0005] and [β = –6.456, p < .0005] respectively, with no significant difference between both [β = 1.921, p = .29].

Differences within and between groups in secondary measures

GEE showed significant improvement in the BDI score over time: BDI [β = –7.133, p < .0005]. Parameter estimates show that both psychotherapies were different from TAU in reducing the BDI score: TBCT [β = –5.724, p = .003]; BA [β = –5.850, p = .009]. There was no difference between BA and TBCT: BDI [β = .12, p = .95].

GEE showed a moderator effect of time in groups. TBCT and BA showed a significant interaction time × group in comparison with TAU: BDI [β = –7.000, p = .01] and [β = –7.509, p = .005], respectively. There was a lack of evidence of difference between TBCT and BA in interaction time x group in BDI: [β = .510, p = .82].

There was an effect of time in reducing disability in SDS throughout the 3 groups [β = –4.252, p < .0005]. BA group was different from TAU in reducing disability in SDS throughout treatment [β = –5.359, p = .002], but TBCT was not different from TAU [β = –2.961, p = .04]. There were no differences between BA and TBCT [β = 2.397, p = .13). Analysis time × group showed an interaction when BA was compared with TAU [β = 5.996, p < .0005] and TBCT with TAU [β = –4.746, p < .0005] but not in the comparison of BA with TBCT [β = 1.250, p = .40].

In the social domain of the WHOQOL, there was an effect of time on improvement of quality of social relationships [β = 3.942, p = .01]. BA and TBCT groups were not different from TAU in improving social quality of life: [β = 9.981, p = .02] and [β = 7.732, p = .02], respectively, with no statistical difference between BA and TBCT [β = –2.248, p = .62]. However, there was an interaction time × group in comparisons: BA with TAU [β = –11.965, p = .002]; TBCT with TAU [β = –11.650, p = .002] but not between BA and TBCT [β = –.315, p = .93].

There were effects of time in improvement of psychological, environmental and physical health domains of WHOQOL and a reduction of symptoms in other scales: WHOQOL all domains: [βs = 5.508 – 7.210, ps < .0005]; BAI [β = 5.818, p < .0005]; CD-Quest [β = 7.020, p < .0005]. Environmental domains did not show statistical improvement of quality of life in comparisons between TBCT with TAU [β = 7.485, p = .03], BA with TAU [β = 1.033, p = .79] and BA with TBCT [β = 6.451, p = .11]. Interaction time × group showed that there was a moderator effect of time in improvement of this domain for BA and TBCT in comparison with TAU [βs = 8.044 – 10.452, ps < .005] but not in BA with TBCT [β = 2.408, p = .43].

There is no difference, in psychological domain, in comparing BA with TAU [β = 8.689, p = .03], TBCT with TAU [β = 6.810, p = .10] and BA with TBCT [β =1.879, p = .59. Interaction time × group shows a moderator effect of time in BA with TAU [β = 15.150, p = .004], but not in TBCT with TAU [β = 11.556, p = .04] and TBCT with BA [β = 3.594, p = .47].

Physical health domain shows an improvement in comparing BA and TBCT with TAU [βs = 7.070 – 8.529, ps < .005] but not between BA with TBCT [β = 1.459, p = .68]. In the same way, interaction time × group shows that time was a moderator in comparing BA and TBCT with TAU [βs = 9.374 – 10.327, ps = .001] but not in TCP with BA [β = .953, p = .78].

The CD-QUEST and BAI scores did not show statistical differences in multiple comparisons between the 3 groups [ps > .42]. However, interactions time × group shows that time had a moderator effect in comparing TBCT with TAU: CD-Quest [p < .0005] but not in BA with TAU [p = .02] and BA with TBCT [p = .68]. Time was not a moderator when comparing between BA and TBCT with TAU: BAI [p > .03].

Discussion

The results of the trial indicated that when added to antidepressants, TBCT and BA helped to significantly reduce MDD symptoms, which did not occur with the continuation of antidepressants alone in HAM-D. When TBCT and BA were compared, there was a lack of evidence of difference in most of the scales (ps > .6). These data were based on the HAM-D scores, one of the most commonly used scales for depressionReference Dimidjian, Hollon and Dobson23 and BDI, in a profile of samples suggesting recurrent MDD.

In addition to HAM-D and BDI, and for the level of significance assumed in this study, TBCT and BA were different from TAU in improvement of physical domain of WHOQOL [ps < .004] and BA was different from TAU in improvement of the SDS score [p = .002]. The data obtained were compatible with a study by Hollon et al., Reference Hollon, DeRubeis and Fawcett22 which had a study design similar to this one that compared antidepressants with CBT. The authors found that combined treatment was more effective than antidepressants alone. In our study, all 3 groups had been maintaining constant drug use for at least 2 months. Elevated depressive symptoms at baseline indicated that patients needed to have antidepressant doses or type of antidepressant altered, in addition to the fact that more than half of our sample had recurrent MDD and comorbidities. These levels of symptoms are explained by the literature, which indicates high rates of recurrence,Reference Monroe and Harkness67 associated with the number of previous depressive episodes, residual symptoms and discontinuation of drug treatment.Reference Yang, Chuzi and Sinicropi-Yao 68, Reference Berwian, Walter and Seifritz69

The TAU group, which received only antidepressants in a naturalistic fashion, had a 60% dropout rate, which can be explained by the participant’s desire to have access to psychotherapy and the availability of free antidepressants in the public health system in Brazil. High dropout rates (up to 58%) have been found in other studiesReference Zu, Xiang and Liu70 in the group with antidepressant monotherapy. There was also more abandonment in the group on antidepressants alone compared to the groups in psychotherapy plus pharmacotherapy in the study by Dimidjian et al.Reference Dimidjian, Hollon and Dobson23 Therefore, the inferiority of the antidepressants here does not seem to be due to the low efficacy of the antidepressants themselves, since they are already known to produce the observed improvements in the symptoms, Reference Cartwright, Gibson and Read71 but to the profile of the sample and those who dropped out.

Moreover, the finding that psychotherapy reduced baseline levels of depression in the population using antidepressants attests to the benefit that the subsequent addition of BA or TBCT to the pharmacological treatment can provide in patients with MDD. Similar results were obtained in a clinical trial that added CBT to the usual pharmacological treatment in patients with MDD who were resistant to antidepressants, finding superiority of the combined treatment.Reference Wiles, Thomas and Abel4

One study in the Chinese population found no difference between CBT + antidepressants compared to antidepressants alone, but antidepressant use started concurrently with psychotherapy, Reference Zu, Xiang and Liu70 in contrast to the present study. On the other hand, there are several studies showing that combined treatment is more effective in reducing depressive symptoms, Reference Hollon, DeRubeis and Fawcett22, Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Weitz, Andersson, Hollon and van Straten27 being therefore more in agreement with our findings, mainly because they showed positive outcomes with the addition of psychotherapy to those who were already in pharmacological treatment, as demonstrated in other studies with similar methodology.Reference Wiles, Thomas and Abel4, Reference Lopez and Basco72

Regarding the comparison of efficacy between TBCT and BA, a component analysis that divided and compared the CBT components, found that BA, which is part of the CBT protocol for depression, Reference Beck73 and complete CBT were equally effective, Reference Jacobson, Dobson and Truax34 similar to what was demonstrated in this study. BA is an approach that does not modify the content of cognitions but addresses them through acceptance and encouragement to action.Reference Martell, Addis and Jacobson18, Reference Hayes, Levin and Plumb-Vilardaga 38, Reference Jacobson, Martell and Dimidjian74 Interestingly, even without attempting to modify cognitions, BA was able to reduce the CD-Quest scores to a similar degree as TBCT, although the size of our sample was not large enough to demonstrate any significant differences between psychotherapies in that measure relative to TAU. In summary, both the change in the content of thoughts, as proposed by the TBCT, without direct incentive for behavioral exercises, and the schedule of activities, without changing the content of thoughts, as proposed by BA, promoted a reduction in the depressive symptomatology and an improvement in measures of incapacity and quality of life. Studies have shown that thought modification improves mood in the course of the therapeutic session itself.Reference Thoma, Pilecki and McKay37, Reference Powell, Oliveira and Seixas45 However, the mechanisms of change within each therapy should be better elucidated in future studies, since improvement in symptoms, especially in MDD, may depend on both common factors (e.g., therapeutic relationship) and specific factors (behavioral or cognitive techniques) found in psychotherapy.Reference Thoma, Pilecki and McKay37

Still regarding the comparison between TBCT or cognitive interventions and BA, in addition to the study by Jacobson et al., Reference Jacobson, Dobson and Truax34 another trial has suggested that both psychotherapies have similar efficacy rates.Reference Richards, Ekers and McMillan75 However, TBCT is a transdiagnostic approach, Reference de Oliveira, Hemmany and Powell41, Reference de Oliveira, Powell and Wenzel43, Reference Delavechia, Velasquez and Duran46 while BA has been shown to be effective in treating only depression to date. Thus, TBCT might be the choice for patients presenting with comorbid conditions.

BA was different from TAU group in reducing disability as measured by the SDS, but both psychotherapies had similar effect sizes: BA [d = 1.9; p = .002] and TBCT [d = 1.7; p = .04], suggesting that TBCT might also be helpful in improving disability in depressed patients. BA acts directly on patterns of avoidance and passivity, encouraging behaviors that increase contact with rewarding environmental events, and many of these events involve interpersonal contact, whether at work or with family or friends.Reference Lejuez, Hopko and Acierno31, Reference Jacobson, Martell and Dimidjian74 Also, in the BA protocol, Reference Martell, Addis and Jacobson18 techniques of functional analytic psychotherapy (FAP) are used, Reference Busch, Rusch and Kanter30, Reference Abreu and Abreu33, Reference Jacobson, Martell and Dimidjian74 in which, through a genuine therapeutic relationship, the passive patterns that occur in the interaction between therapist and patient are the target of intervention, perhaps explaining the interpersonal improvement in this group.Reference Kohlenberg and Tsai76–Reference Manos, Kanter and Rusch79 In this way, BA acts to improve functionality and to reduce disability, which is associated with welfare, as demonstrated in other studies, Reference Kern, Busch and Schneider80 resulting in mood improvement.Reference Nagy, Cernasov and Pisoni81 TBCT was effective in the improvement of quality of life, as shown in a previous studyReference Powell, Oliveira and Seixas45 possibly by the changes of negative evaluation throughout the TBCT techniques.

The findings of this research regarding the cognitive modifications made directly by TBCT and indirectly by BA, because BA does not address the content of cognition but encourages action despite the content, lead to the possible interpretation that cognitive change precedes emotions and behaviors and that exposure to reinforcers produces the emotional and behavioral changes.Reference Jacobson, Dobson and Truax34 Studies on the mechanisms of therapeutic change are necessary to check this assertion.

TBCT and BA significantly reduced BDI scores relative to TAU. However, the effect sizes of the psychotherapies were similar. Wiles et al.Reference Wiles, Thomas and Abel4 compared CBT with antidepressants versus usual treatment (antidepressants alone) with using BDI as the primary outcome measure. The results also indicated a greater response in the CBT group compared to antidepressants alone in reducing depressive symptoms, corroborating our findings that the combination of psychotherapy with drugs can produce a better effect.

Although CBT and TBCT are similar approaches, the latter has specific techniques directed to the modification of dysfunctional CBs associated with psychopathological symptoms. De Oliveira et al.Reference de Oliveira, Powell and Wenzel43 found equivalent reductions in a comparison between TBCT and CBT. Moreover, TBCT was more effective in reducing the fear of negative evaluation compared to CBT, in patients with social anxiety disorder. These findings can be attributed to the constant engagement and focus that TBCT encourages in the discovery of evidence for and against dysfunctional negative CBs, by means of an analogy to a legal process, to modify absolute and inflexible CBs.Reference Powell, Oliveira and Seixas45 This approach has also been shown to be as effective as exposure therapy in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, and more effective than exposure therapy in reducing depressive symptoms as measured by BDI in these patients (Duran et al., submitted). TBCT was effective in the cognitive restructuring of CBs in patients presenting with several diagnoses with changes in associated emotions.Reference de Oliveira, Hemmany and Powell41, Reference Delavechia, Velasquez and Duran46

Limitations

This trial has limitations. First, the dropout rate was higher than that in previously published studies. The TAU group had a dropout rate of 61.6%, with only 10 patients completing the 3 evaluations, as well as a considerable number of dropouts in the psychotherapy groups. Failure to provide psychological or psychiatric help to the TAU group might be a reason for the high dropout rate. Other studies have shown large dropout rates for the antidepressants group. For example, Dimidjian et al.Reference Dimidjian, Hollon and Dobson23 indicated that the group receiving antidepressants had 46 patients who completed from a baseline of 100 subjects, and the study by Zu et al.Reference Zu, Xiang and Liu70 found that of the 60 patients randomized to antidepressants, 25 completed the final evaluation.

Possibly, the TAU group was not receiving adequate psychiatric treatment, which might be another limitation of this study. One way to avoid this limitation would be to follow up all patients with a psychiatrist who could perform antidepressant management in TAU, while keeping the psychotherapy groups at stable doses. The psychiatric follow-up of all patients might reduce dropout rates in all groups. Additional alternatives based on other strategies, including sending emails, phone messages and calls to patients by the researchers as well as educational workshops to keep the patients engaged, could have been implemented.Reference Brueton, Tierney and Stenning82

Another limitation was the small sample size. Considering that the required sample size was more than 30 patients per arm, our study only obtained two-thirds of that number. Also this trial also did not stratify patients according to TDM severity. Additionally, as pointed out by Hollon et al., Reference Hollon, DeRubeis and Fawcett22 research involving psychotherapy should be tailored to the needs of each patient, with more intense sessions, and lasting more than 30 weeks, as was done in their trial.

New clinical research should be conducted with both BA and TBCT to increase the amount of empirically supported psychotherapies for the improvement of this increasingly common and disabling disorder.

Conclusions

The addition of TBCT or BA as an adjunct to antidepressant treatment is more effective than the continuation of antidepressants alone in patients with MDD, particularly in a population of patients who have a recurrent profile of the symptoms. Both psychotherapies produced a therapeutic response in patients who were already taking antidepressants; the patients in this population seem to represent a proportion of depressive patients with recurrent problems, comorbidities, and possible problems in adhering to pharmacological treatments, possibly due to issues in the public health system, especially those that are dedicated to mental health. Both psychotherapies were able to reduce the baseline symptoms measured by HAM-D by more than 50%, with robust effect sizes and to improve quality of life. The BA intervention reduced both the depressive symptoms and the disability caused by them, improving functionality, in addition to other trials that prove their specificity and great effectiveness in the treatment of MDD. This study increases the degree of evidence favoring BA as one of the first-choice treatments for MDD.

TBCT proved to be as effective as BA. TBCT has been shown to be effective in the improvement of other disorders, such as social phobia and PTSD, and is now found also to be also effective in the treatment of MDD, as demonstrated by this study. The data suggest that TBCT is an effective transdiagnostic approach, possibly acting by way of its distinctive potential to modify dysfunctional negative CBs in a more experiential fashion.

Disclosure.

Curt Hemanny, Clara Carvalho, Nina Maia, Daniela Reis, Ana Cristina Botelho, Dagoberto Bonavides, and Camila Seixas have no conflict of interest to declare. Irismar Reis de Oliveira is the developer of trial-based cognitive therapy (TBCT).