INTRODUCTION

Past research on preference organization has shown that there is a normative orientation for preferred responses to first actions such as requests, offers, invitations, and assessments to be delivered early and in simple form, whereas dispreferred second actions are typically much more complex, mitigated, and indirect, and are accompanied by prefaces, hesitations, repairs, apologies, and accounts (e.g., Levinson Reference Levinson1983, Davidson Reference Davidson, Atkinson and Heritage1984, Drew Reference Drew, Atkinson and Heritage1984, Heritage Reference Heritage1984, Pomerantz Reference Pomerantz, Atkinson and Heritage1984). Importantly, Lerner Reference Lerner1996 and others point out that dispreferred responses not only incorporate mechanisms for delaying the production of the gist of a dispreferred response but also concurrently provide early indications that a possible dispreferred response might be in the offing through maximizing its projectability.

Although conversationalists in any language are likely to face the need to tackle the potentially universal task of delaying the production of dispreferred responses, research in interactional linguistics is increasingly showing that certain linguistic resources for accomplishing specific interactional activities may feature more prominently or noticeably in some languages than in others (e.g., Lerner & Takagi Reference Lerner and Takagi1999; Tanaka Reference Tanaka1999; Couper-Kuhlen & Thompson Reference Couper-Kuhlen, Thompson, Kortmann and Couper-Kuhlen2000, Reference Couper-Kuhlen, Thompson, Hakulinen and Selting2005; Selting & Couper-Kuhlen Reference Selting and Couper-Kuhlen2001; Hayashi Reference Hayashi2003; Thompson & Couper-Kuhlen Reference Thompson and Couper-Kuhlen2005). For instance, Japanese speakers have considerable freedom to vary the order in which main grammatical elements such as subject, object, and verb appear. Among other things, this practice is regularly directed toward enabling early delivery of preferred responses or delayed production of dispreferred ones, as reviewed below. In contrast, as often cited, such grammatical prerogatives are not as readily available in English (e.g., Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985:50; Fox, Hayashi & Jasperson Reference Fox, Hayashi, Jasperson, Ochs, Schegloff and Thompson1996; Thompson & Couper-Kuhlen Reference Thompson and Couper-Kuhlen2005), with elements such as subject, verb, and object being more or less obligatory, and word order more resistant to permutation than in Japanese. Nevertheless, English speakers likewise have an interactional rationale for delaying the delivery of dispreferred responses.

If English grammar is indeed relatively inflexible in the above respects, however, it makes sense to ask how speakers might be adapting to the grammatical constraints under which they operate, and what alternative devices, if any, they may be deploying to realize the same interactional objective of delaying dispreferred responses. To take this further, one might even entertain the possibility that the very same resource as in Japanese – varying word order – is perhaps also being enlisted in English, but in more constrained, subtle, or deceptive ways. On a more fundamental level, such questions provide an opportunity to take a cross-cultural/linguistic perspective to sensitize ourselves to certain taken-for-granted patterns in interaction, which might otherwise be relatively elusive or intangible in one language, but happen to be more overtly manifested or clearly visible in another. Such an endeavor bears upon the deep-seated issue of universality versus cultural/linguistic specificity: how participants in different linguistic communities might be employing potentially divergent sets of available grammatical devices to implement shared interactional tasks. In the process, this article addresses the more general question of how the context-free aspects of preference – for example, the management of the timing of social action – may be realized in context-sensitive ways through the linguistic tools provided in different languages.

It should be underscored, however, that no assumption is being made here that English conversationalists themselves might be orienting to the grammatical resources at their disposal as being in any way limiting or deficient. Conversation analytic studies have revealed the seemingly effortless ways in which local conditions are adapted for interactional operations such as turn-taking and repair (e.g., Fox, Hayashi & Jasperson Reference Fox, Hayashi, Jasperson, Ochs, Schegloff and Thompson1996, Tanaka Reference Tanaka1999). Even if constraining factors do exist, they are likely to be dealt with as a matter of course, or as second nature. Moreover, it goes without saying that participants are normally not actively comparing the linguistic tools available in their immediate interactional environment to those of another culture or language. Referring to the difficulties of cross-cultural comparisons in general, Lerner & Takagi (Reference Lerner and Takagi1999:50) note: “It is important to remember that much linguistic and other cultural difference is not produced for the most part as difference, but as separate features situated in their own cultural milieu.” At the same time, however, we should not underestimate the possibility that an understanding of the ostensibly artful ways of dealing with potential grammatical “constraints” may well point to hitherto uncharted aspects of the relationships among grammar, culture, and social interaction.

This article starts with a brief summary of the management of word order in Japanese to delay dispreferred responses or expedite preferred ones. Against this backdrop, I embark on a preliminary exploration of the salience of word order for the realization of dispreferred actions within the purportedly rigid word order constraints of English. Attention will then be directed to the implementation of other grammatical operations that circumvent or work within the potential limitations of word order variability to delay the onset of declination/disagreement components while simultaneously projecting them.Footnote 1 Space limitations make it impossible to consider in any detail other integral dimensions of the organization of preference, such as prosodic, visual, and bodily displays (e.g., Auer, Couper-Kuhlen & Müller Reference Auer, Couper-Kuhlen and Müller1999, Ogden Reference Ogden2006). The data include several major data corpora, among them the Holt, Rahman, SBL, and Heritage corpora.Footnote 2

SUMMARY OF GRAMMAR AND PREFERENCE ORGANIZATION IN JAPANESE

As already noted, word order in Japanese is extremely flexible. The main grammatical elements, such as subject, object, and verb, can be produced in practically any order for a turn to maintain “coherence” for participants. Moreover, these elements, which are often found to be essential in English turn construction, are regularly left unexpressed in Japanese when deemed recoverable from the context. To briefly summarize the main points in Tanaka Reference Tanaka2005, such linguistic features interlock with preference organization, permitting word order to be freely managed to delay dispreferred responses and hasten preferred responses. This is typically realized grammatically by housing the gist of either a dispreferred or preferred response in a predicate component, and producing the component turn-finally for dispreferred responses versus turn-initially (or as the sole component expressed in a turn) in the case of preferred responses.

At the risk of simplification, fragments (1) and (2) from the above-mentioned article exemplify the routine management of word order in the construction of dispreferred and preferred responses, respectively. In the excerpts throughout this article, the first pair part of an adjacency pair is highlighted with a + sign, the corresponding second pair part with an arrow; and the gist of a dispreferred response in boldface. In the Japanese excerpts, unexpressed elements are supplied within double parentheses in the English gloss.

In the following, a clerk at a newsagents has telephoned the distributor to ask on behalf of a customer whether the distributor can locate a copy of an advertisement that appeared in a magazine. In response to the request, the employer of the distributor gradually builds up an elaborate, highly expressed response, incrementally projecting a declination, while simultaneously delaying the declination component.

(1)

It can be observed that various grammatical items such as adverbials and topic phrases are produced early in the turn (lines 13–18), thereby delaying the declination component (line 19), which is carried in the verb phrase wakara nai ‘have no knowledge of’,Footnote 3 occurring as the final major syntactic element of the turn. In this way, participants can maximally load a turn to include prefaces, mitigations, and accounts prior to the declination component, thereby heightening its projectability.

In contrast to the delay and complexity observed in the above fragment, the following instance of a preferred response exemplifies an early occurrence of the gist of an agreement. In this multiparty conversation, the participants are talking about how the fashion trends of their youthful days have come back.

(2)

The agreement (line 2) is brought to the very opening of the turn through a word order beginning with the predicate and followed by a subject, resulting in the agreement appearing at the earliest possible opportunity. To repeat, the fragments above illustrate the common practice in Japanese of carrying the gist of an action in the verb or predicate, and either delaying or hastening its delivery by varying the word order in accordance with whether a response is dispreferred or preferred, respectively.

DEVICES FOR DELAYING DISPREFERRED RESPONSES

Numerous devices for delaying or withholding declination components in English have been identified in previous research. For instance, a declination of an invitation may be prefaced with silence (Davidson Reference Davidson, Atkinson and Heritage1984), hesitation, the token Well, or appreciation, as well as, sometimes, the inclusion of beginnings such as I don't think (Atkinson & Drew Reference Atkinson and Drew1979:58). Likewise, a rejection of an offer can be delayed by an initial production of an appreciation (Atkinson & Drew Reference Atkinson and Drew1979:58–59). Disagreements with assessments can be delayed by silence, repair initiators such as partial repeats and requests for clarification, or a weak agreement followed by a contrastive conjunction, such as but, prior to a disagreement (Pomerantz Reference Pomerantz, Atkinson and Heritage1984). More recently, Couper-Kuhlen & Thompson Reference Couper-Kuhlen, Thompson, Kortmann and Couper-Kuhlen2000 and Barth-Weingarten Reference Barth-Weingarten2003 demonstrate how disagreements are regularly prefaced, though also sometimes followed, by an acknowledgment or concession. Further, Heritage Reference Heritage1984 and others show that, in the case of invitations, requests, and offers, an account may sometimes suffice in place of a declination, and that a declination itself is routinely softened or mitigated. Importantly, I will be drawing on the insight that “dispreferred seconds of quite different and unrelated first parts (e.g., questions, offers, requests, summonses, etc.) have much in common, notably components of delay and parallel kinds of complexity” (Levinson Reference Levinson1983:333).

One of the aims of this article is to build on other work in interactional linguistics to further refine these descriptions in order to understand more systematically the grammatical methods employed by speakers for projecting and delaying the gist of dispreferred responses in English. The focus will initially be on such syntactic resources, although one is constantly reminded that grammar is simply one facet of, or resource for, action in interaction (see Schegloff Reference Schegloff1995; Goodwin Reference Goodwin, Ochs, Schegloff and Thompson1996; Lerner & Takagi Reference Lerner and Takagi1999:50; Thompson & Couper-Kuhlen Reference Thompson and Couper-Kuhlen2005). Although no attempt will be made to achieve exhaustive coverage, I begin by considering how participants manage word order for this purpose, by characterizing the kinds of grammatical units that are regularly enlisted prior to a gist of a dispreferred response. This is followed by an examination of the use of a family of grammatical constructions with which English speakers are able to offset the purportedly limited mobility of major grammatical elements within a turn.

OPERATING ON WORD ORDER FOR DELAYING DISPREFERRED RESPONSES

It was noted previously that Japanese speakers regularly employ predicate-final word order to structure dispreferred responses while housing the dispreferred content in the turn-final predicate – an ordering optimized for the insertion of a range of prefaces, accounts, and qualifications prior to the dispreferred action. In the case of English, however, word order variability is restricted. Nevertheless, when it comes to certain categories of elements such as adverbials, discourse markers, and epistemic expressions (Table 1), all with a degree of syntactic autonomy, their positioning within utterances permits some mobility (e.g., Ford Reference Ford1993, Fox et al. Reference Fox, Hayashi, Jasperson, Ochs, Schegloff and Thompson1996, Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985). Moreover, these grammatical items are essentially syntactically “non-obligatory” elements of clause structure.Footnote 4 They often consist of formulaic expressions, which lay the groundwork for a forthcoming dispreferred content without themselves having explicitly declinatory properties. In the data, such items were indeed regularly found turn-initially or medially, in effect displacing the gist of the dispreferreds toward the end of a turn, albeit sometimes by only a split second. Examples of these three categories will be examined below for the ways in which they may delay the dispreferred content.

table 1. Categories of items used to delay the production of the gist of dispreferred responses.

I begin by considering the general category of adverbials, consisting of grammatical elements such as adverbs, adverbial phrases, adverbial clauses, prepositional phrases, and parenthetical inserts that are regularly employed to preface dispreferred responses. Although not specifically looking at the delaying function of adverbials, a number of writers have shown that adverbials of one kind or another can sometimes serve to announce dispreferred actions (see, e.g., Ford Reference Ford1993 on adverbial clauses; Clift Reference Clift2001 on actually; Barth-Weingarten Reference Barth-Weingarten2003; Edwards & Fasulo Reference Edwards and Fasulo2006 concerning “honesty phrases”).Footnote 5 The interactional significance of adverbials will invariably differ case by case, also depending on the grammatical type and the specific contexts in which they are occasioned. Generally speaking, however, they can be employed to provide some kind of background that frames an upcoming dispreferred or to specify a sense in which the immediately ensuing talk is to be understood. They may, in some instances, qualify or mitigate the emergent declination or disagreement, as in example (3). The items under scrutiny are enclosed in boxes □ and the gist of the dispreferred highlighted in boldface.

(3)

In this excerpt, H makes an offer of help that is declined by S. After the latter's pre-declinatory Well ‘at’s and appreciation, an adverbial phrase At the moment is inserted immediately before the declination component no:, having the effect of delaying the latter and breaking the “contiguity” between the offer and the declination (see Schegloff Reference Schegloff2007:63–73). The adverbial phrase qualifies the upcoming gist of the declination by nominally delimiting the refusal to the present point in time, theoretically leaving open the possibility that the offer may be accepted at a future date. Interestingly, phrases chosen for this slot frequently (though not always) turn out to be formulaic expressions that qualify or mitigate a forthcoming declination – for instance, as a matter of fact, come to think of it, under the circumstances. Such pre-positioned expressions can be employed to gently set the tone for an upcoming dispreferred content without themselves performing a declination or disagreement.

Excerpt (4) exemplifies the use of adverbial clauses, which are also a subclass of adverbials.

(4)

In response to earlier talk by Jay, Bob develops the point that people have been predicting that the world is coming to an end for thousands of years (between lines 3 and 12).Footnote 6 In partial overlap, Jay begins to construct a disagreement in line 8 by embarking on the first part of a two-part “compound turn-constructional unit” (Lerner Reference Lerner1991) with an adverbial clause beginning with if (initially truncated). He restarts in lines 13–14, If there- there was ever a ti:me, when the world, at least the h uman world, was going to come to an en:d?, which substantially delays the onset of the ensuing main clause, it would be no:w., containing the gist of the disagreement, no:w (line 15). Moreover, the grammatical structure of the adverbial clause (i.e., the first part of the compound TCU), combined with the contextual particulars (i.e., an environment of disagreement) projects the rough contours of the second part to follow: for example, If there was ever a time when A was going to happen, it would be B, where B would contain a temporal formulation differing from the one put forward by Bob (thousands of years ago). In other words, the initial adverbial clause not only stipulates the grammatical format of the second part but also provides a general framework and background for anticipating the impending gist of the disagreement. This if-clause instantiates a type of conditional clause analyzed by Ford Reference Ford1993, structured to treat the information in the prepositioned if-clause as a given, from which the material presented in the main clause is to follow as a logical conclusion. This structure is exploited here for delaying and softening the disaligning gist of the disagreement, by using the initial clause for hypothesizing about the end of the world, which itself is not the bone of contention. Instead, it is the ensuing main clause that houses the disagreement – postulating when the world will come to an end – as an option conditional on the hypothesis presented in the adverbial clause. The disagreement, then, is considerably attenuated through this turn construction, which places distance between the undisputed aspect of the issue and the point of contention by carrying them in separate clauses.

Consider an example of a “purpose adverbial clause” used to delay a declination:

(5)

After the doctor initially recommends that the patient go to a hospital (not shown), the caller articulates the patient's reluctance to go to hospital, followed by an implicit request that the doctor (or someone else) come to see him (lines 27–28). In response, the doctor in effect declines the request by partially repeating his earlier recommendation that the patient needs to go to hospital (lines 29–31).Footnote 7 In an emotional outburst, the caller then “corrects” the doctor's formulation of the injury as broken his bone by embarking on an on-line reporting of the state of his friend's shoulder blade (between lines 32 and 38). After acknowledging this, the doctor relaunches the recommendation that the patient go to hospital (lines 39–40). Although other facets of this turn will be reexamined in the next section, I note for now that the doctor positions a purpose adverbial clause to save time before to the gist of the dispreferred in which he obliquely reinvokes the patient's need to go to hospital, this time, by suggesting that he call for an ambulance: Yes. uWhat I'm tryin'a say, is ![]() he ou- he: u:h the best thing tuh do is to call for an ambulance.

he ou- he: u:h the best thing tuh do is to call for an ambulance.

Although it focuses on written texts, there is much to be learned from Thompson's (Reference Thompson1985) discussion of the particular utility of initial purpose clauses to “guide the reader's attention in a very specific way, by naming a problem which arises from expectations created by the text or inferences from it, to which the following material, often consisting of many sentences, provides the solution” (p. 67). In the context of excerpt (5) above, the talk preceding the purpose adverbial clause to save time (including the caller's emotional outburst) can be heard to create an “expectation” – for instance, that the patient has a dire medical condition that requires urgent attention. The consequent identification of the problem of how best to save time, in turn, raises further expectations and projects the subsequent articulation of a “solution,” as duly supplied in the main clause: he ou- he: u:h the best thing tuh do is to call for an ambulance. Here, the “solution,” which comes last in this scheme, simultaneously houses the gist of the dispreferred response. On another level, then, the initial purpose adverbial clause construction can be seen as one interactional “solution” to “the problem” of how to delay the appearance of the gist of a dispreferred response. Further, as the purpose adverbial clause in the excerpt does create a relatively tight logical link with the ensuing main clause, it can be quite specific in the way it prepares the interlocutor for the kind of dispreferred content to follow. In particular, the dispreferred status of the doctor's turn notwithstanding, the adverbial clause in this excerpt to save time contributes to setting an affiliative tone for the entire turn through the formulation of “the problem” as one motivated by concern with the patient's welfare (instead of say, by an institutional need for efficiency), which thereby frames the upcoming dispreferred “solution” as something in the patient's best interests.

In sum, in addition to the effect of the delay itself, the prefacing of a dispreferred response with “adverbials” – when they do not contain directly negating, refuting, or declinatory elements – can have wide-ranging implications for variously qualifying, mitigating, and providing the background for the dispreferred action. This is done, for instance, by fronting an adverbial phrase to delimit the scope of applicability of a dispreferred response, as in (3); through fronting a conditional adverbial clause and framing a difference of opinion as arising from a mutually shared position, as in (4); or by employing an initial purpose adverbial clause to present a disagreement as originating from a concern to bring about a positive outcome for the interlocutor, as in (5).

The second general class of grammatical items that were regularly found to preface a declination component is a subset of elements broadly classifiable as discourse markers (Schiffrin Reference Schiffrin1987), including address terms such as Lottie or dear, and expressions for monitoring and managing talk, such as Look, Listen, I'll tell you, I might remind you, Tell me, Let me see, You know, You see. Being syntactically perhaps even more autonomous from clause structure than adverbials are, they are easily brought to some position preceding a declination component. Two examples are presented below:

(6)

(7)

The discourse marker look Oz in excerpt (6) is an example of an expression for monitoring and managing talk combined with an address term. Skip enlists the expression within an elaborate account of why he is unable to take on with the request at the present time. Lerner notes that the use of address terms is relatively unconstrained in relation to turn construction or grammatical position, but that they are routinely used when doing something beyond just addressing, such as to show concern or a positive or negative stance of some kind (Reference Lerner2003:184–87). This additional use of address terms as stance markers is likely to be particularly salient in telephone calls (as in this case), where there is normally no need to employ names simply for the purpose of addressing. Indeed, it occurs as a part of a highly affiliative turn full of displays of contrition, willingness, and obligingness.

With respect to the positioning of discourse markers in dispreferred responses, the data show that they are regularly preceded by Well, as in the two examples above. Furthermore, the expression look Oz also serves to mark and facilitate the transition from the speaker's affiliative retrieval of a prior promise to oblige (lines 8–9) to the articulation of the reason for the potential inability to fulfill the promise on this occasion (lines 11–12). The discourse marker let me see in excerpt (7) is also positioned to enable an interactional transition from an affiliative act of showing appreciation to a disaffiliative one of rejecting an offer. Discourse markers observed in such positions in the data typically have relatively little semantic content and frequently consist of formulaic expressions, but they nevertheless represent a class of elements regularly used to preface some problem, and they sometimes serve an important role as an interactional pivot.

Closely related to the use of discourse markers is a method of delaying the gist of a dispreferred with epistemic expressions such as I think, I say, I guess, I'd bet you. Albeit less frequently (in the current data set), speakers also employ evidentials such as I mean, it seems, it sounds as though, it looks like, which are sometimes classified as a subset of epistemic phrases (e.g., Palmer Reference Palmer1986; Kärkkäinen Reference Kärkkäinen2003:18–19). Like the previous two types, they are somewhat independent of clause structure and have a relatively high degree of syntactic mobility (see Thompson & Mulac Reference Thompson, Mulac, Traugott and Heine1991). Like discourse markers, epistemic expressions that delay the gist of dispreferred responses are typically positioned immediately before a clause containing the gist, though they can occur elsewhere. When featuring in pre-declinatory positions, they can herald the dispreferred content by displaying a stance that frames upcoming talk (see Thompson Reference Thompson2002; Kärkkäinen Reference Kärkkäinen2003:136–37). While not looking specifically at dispreferred responses, Thompson (Reference Thompson2002:139) observes that the most frequently found epistemic phrases in her database of conversations occurred as formulaic phrases with the first person singular, and with no complementizer.Footnote 8 Thompson Reference Thompson2002 and Kärkkäinen Reference Kärkkäinen2003 both report that I think is by far the most commonly occurring epistemic phrase.

The data show participants making use of such forms not only to delay the dispreferred content but also as a hedge, by vesting their stand with some uncertainty. The following excerpt exemplifies how this class of expressions has some mobility in terms of positioning.

(8)

Here, a minor disagreement develops after Bea asserts that those things can be developed through work (line 1), to which Maude hearably begins to produce a counterargument in line 3, partially overlapped by Bea's underlining that they are not accidents (line 4). To this, Maude responds in line 6 first with a concession No? they takeworking at (see Couper-Kuhlen & Thompson Reference Couper-Kuhlen, Thompson, Kortmann and Couper-Kuhlen2000, Barth-Weingarten Reference Barth-Weingarten2003), but goes on to produce a disagreement that a sense of humor is something that one is born with (lines 6–9), delaying and hedging the latter with the epistemic phrase I think coming shortly before the phrase containing the gist of the disagreement: something you're ↓born with. The exchange of divergent opinions undergoes another cycle as Bea reasserts her position in lines 11 and 12, with the disagreement it can be de↑v eloped ↑to o:, likewise prefaced by I think. Among other things, this example illustrates the flexibility of positioning of epistemic expressions, which do not necessarily come at the beginning of a clausal structure but are also found in other places, such as after the subject but before the copula of a copular clause (e.g., line 8), exemplifying a phenomenon described as the “grammaticization of epistemic parentheticals” (Thompson & Mulac Reference Thompson, Mulac, Traugott and Heine1991, Thompson Reference Thompson2002).

Participants' orientations to the propriety of the use of epistemic expressions within dispreferred responses is demonstrated through the kinds of self-editing that speakers regularly engage in when producing dispreferred responses (Fox & Jasperson Reference Fox, Jasperson and Davis1996), as in the next two excerpts.

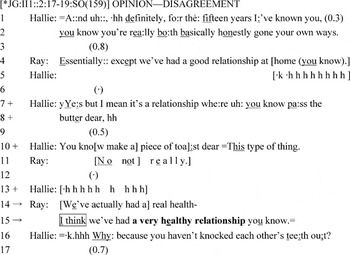

(9)

In excerpt (9), to Ray's positive assessment of his relationship with his partner … we've had a good relationship at home ( youknow) (line 4), Hallie begins her response with y Ye :s but followed by the evidential I mean, after which she goes on to disagree by providing two enactments devaluing the relationship: youknow pa:ss the butt er dear,hh (lines 7–8) and You know make a piece of toa :st dear (line 10). An orientation to the appropriateness of utilizing epistemic phrases in engaging in “amicable” disagreements by delaying and mitigating a dispreferred is demonstrated several lines down. In line 11, Ray proceeds to refute the implications of Hallie's dramatization, although overlapped by the latter. Then in line 14, Ray launches a further rebuttal beginning with W e've actually had a real health- which is cut off but clearly hearable as an emerging disagreement, coming subsequent to the overlaid Non ot r eally in line 11, as well as the use of actually, which can be confrontational, depending on its positioning within responses to questions built to prefer a yes-answer (see Clift Reference Clift2001). However, Ray stops mid-course and repairs line 14, not only by editing out the actually, but also by prefacing the turn beginning with the epistemic expression Ithink, and then continuing with a partially variant repeat of the original version: we've had a very healthy relationshipyo uknow (line 15).

The next excerpt contains a direct replacement of I don't think with I think, which moreover contributes to transforming an incipient response from one with negative polarity to one with positive polarity:

(10)

To Deena's inference that the acquaintances who cancelled their wedding will be unable to recover their deposit (lines 1–2), Mark first proffers token agreements (lines 4–6), and after adding but goes on to produce what sounds as though it will turn into a negatively formulated disagreement – I d on't think (line 6) – which projects a continuation such as they ended up losing all that much. Instead, he immediately repairs I d on't think to I th ink, thereby altering the turn-trajectory from a directly countervailing stance to one that performs the disagreement more obliquely by drawing out a redeeming aspect of the situation: the graciousness of the people to whom the deposit was paid.Footnote 9

Summing up the discussion thus far, it may not be accidental that items that regularly get placed prior to the gist of a dispreferred tend to be elements that are syntactically relatively mobile or autonomous within clause structure. If one grants that there is an interactional rationale for speakers to mobilize whatever resource may be available in the interest of delaying the onset of a declination component to maximize affiliation with coparticipants, the very fact that grammatical forms found to appear early in a clause essentially turn out to be items such as adverbials, address terms, discourse markers and epistemic phrases – that is, syntactically mobile or autonomous expressions – indicates that speakers must indeed be constrained by the word-order restrictions in conversational English that militate against “major” grammatical elements being brought forward with ease.

HOUSING THE GIST OF A DISPREFERRED RESPONSE IN A CLAUSE-FINAL SYNTACTIC ELEMENT OF A COPULAR CONSTRUCTION

Now, given the potential restrictions on movement of word order, the next logical step would be to consider whether participants exploit methods other than manipulating word order to achieve the very same objective of delaying the gist of a dispreferred response. The data indicate that one way English speakers may be circumnavigating the possible limitations of a relatively fixed word order is by working within the syntactic constraints of “canonical” word order of the English language in order to postpone the onset of a dispreferred action. Importantly, just as Japanese speakers deploy word order variability, which is a prominent feature of Japanese syntax, English speakers can be observed to opt for turn designs that are in concert with the syntactic resources at their disposal. This study ends with an examination of a specific device – found preponderantly within dispreferred responses – by which delay is accomplished, not via an operation on word order but through the deployment of the canonical word order of a ready-made syntactic construction in which the final slot can be tailored to house the gist of a dispreferred.

As one commonly observed type of canonical word order in English, a predicate is positioned as the last main element of a copular clause:

(a)

The data show that speakers have regular recourse to this ordering principle for achieving delay, by carrying the gist of a dispreferred response within the turn-final slot Z. To see this construction at work, perhaps in its simplest form, the following lines are reexamined. (To see the full excerpt, please refer to ex. 4 above.)

(11)

As previously described, to an interlocutor's stand that people have been prophesying the impending end of the world for thousands of years, the speaker delays the onset of the gist of a disagreement by housing it within the main clause Y (it would be no:w.) of a compound TCU of the form “if X – then Y.” It is apparent that an even greater delay is being accomplished by designing Y itself as a copular clause, and by placing the dispreferred content no:w in the clause-final slot.

To demonstrate participants' orientations to the utility of the copular construction for implementing dispreferred actions, instances of repair in two earlier excerpts will be reexamined. The following is a particularly revelatory example of participant orientation to this syntactic turn shape, arrived at as the result of a repair of an emergent syntactic form with the gist appearing turn-medially into a copular construction that targets the turn-final slot Z for housing the gist of a disagreement:

(12)

Recall that Bea had just mentioned that qualities like sense of humor take working at, and are not accidents. To this, Maude embarks on a disagreement. Note, however, that before the unit in lines 6–7 emerges in full, it is abandoned and wholly restructured to the form in lines 8–9:

Looking at the kind of repair taking place, in lines 6–7 Maude starts to construct a clausal unit according to the SVPP structure: s ome people (·) are(b) (·) bo:rn withuh-m (0.3). This syntactic structure involves a relatively early placement of the gist of the disagreement are born in the slot for the verb component, followed by the beginning of a prepositional phrase withuh-m, projecting some prepositional object such as a sense of humor, supplied above in double parentheses. Before this unit develops fully, Maude stops and restarts (in line 8) by deploying instead a copular construction with an embedded epistemic phrase: Subject—I think—is—Z, where the gist of the disagreement (born with) now occurs within the predicate nominal clause something you're ↓born with, which in this case is the final main element Z of the copular clause.

Of note is the fact that the copular construction assumes the basic structure

(b)

referred to as a “reversed pseudo-cleft” (Erdmann Reference Erdmann1990, Collins Reference Collins1991), serving additionally to push back the gist of the disagreement within the predicate nominal clause itself: something you're ↓born with. Among other things, this fragment shows Maude implementing radical adjustments to achieve maximal delay in designing a disagreement, and specifically an orientation to the appropriateness of (a particular variation of) the copular construction as part of an overall attempt to hedge, mitigate, and delay a dispreferred response.

The following will be reinspected as a case of repair that suggests possible interactional grounds for specifically choosing a copular construction to perform a dispreferred action:

(13)

Notice that at the end of line 39, the doctor begins to produce what appears to be a clausal structure, he ought to…, which would formulate the disagreement/declination in prescriptive terms with possible moral overtones. However, he abandons this inchoate expression and opts for a copular construction of the form

(c)

which not only delays the gist of the declination but also renders it more indirect by presenting it as the best choice among alternatives.

Generally speaking, instances of relatively simple copular clauses, as in excerpt (11), were few and far between among the dispreferred responses observed in the data at hand. For instance, the predicate nominals (slot Z) in the copular constructions highlighted in (12) and (13) are themselves clausal. Indeed, copular constructions built into dispreferred responses typically exhibit highly complex internal structures, far too elaborate to deal with fully within the scope of this article. Suffice it to say that this syntactic structure admits a wide range of subtypes, where the SUBJECT position can consist of anything from a word to a clause, and slot Z potentially allows for even more variability and complexity in its internal structure, ranging from a simple predicate adjective/predicate nominal to a complex multi-unit utterance.

As one commonly observed variation of this grammatical form, speakers routinely preface an upcoming dispreferred content with the thing is …, where the declination component is carried or projected in the turn-final slot, as demonstrated below:

(14)

Immediately before the part reproduced here, Heatherton's reporting of the doctor's recommendation of the ointment was met with a series of unenthusiastic responses from Joan. In line 1, when Heatherton suggests that the medication may at least help their mother psychologically, Joan begins to respond more substantially (line 3) by employing a copular construction of the basic form:

(d)

Joan's response in line 3, Well you see ![]() the thing is tih day it'sgone tuh huhr knee:., which begins with the pre-declination well and discourse marker you see as previously discussed, thereafter directs attention to a novel physical symptom, contrasting with the need for psychological relief implied by Heatherton immediately beforehand. In other words, the slot Z is already being filled by material with hearably declinatory overtones. After an intervening silence, Joan resumes her response with An:d, launching into a lengthy informing about how the knee trouble began and the major inconvenience it is causing. Joan concludes the informing with a more unequivocal declination: En the Al: Al:geepan is (.) neo diffrent from the stuff thet I: put on al ready you know (lines 20–21). In retrospect, slot Z can be seen to have expanded to include the extended informing between lines 3 and 21 (containing a brief exchange between the interlocutors in lines 17–19); of note are the numerous connectives such as and, so, and because that Joan uses to mark continuations within her informing. The expression the thing is…, while having meager semantic content and without itself being declinatory, enables Joan to announce and frame the background and reasons for declining Heatherton's suggestion, and to delay the production of the ultimate gist of the declination to the very end of the turn. Couper-Kuhlen Reference Couper-Kuhlen2001 observes that the formula the thing is… “signals that the turn's business is complex and thus projects a multi-unit turn.” The data yielded other constructions with similar interactional uses, including the thing is though…, the only thing is…, the circumstances are…, and the fact of the matter is….

the thing is tih day it'sgone tuh huhr knee:., which begins with the pre-declination well and discourse marker you see as previously discussed, thereafter directs attention to a novel physical symptom, contrasting with the need for psychological relief implied by Heatherton immediately beforehand. In other words, the slot Z is already being filled by material with hearably declinatory overtones. After an intervening silence, Joan resumes her response with An:d, launching into a lengthy informing about how the knee trouble began and the major inconvenience it is causing. Joan concludes the informing with a more unequivocal declination: En the Al: Al:geepan is (.) neo diffrent from the stuff thet I: put on al ready you know (lines 20–21). In retrospect, slot Z can be seen to have expanded to include the extended informing between lines 3 and 21 (containing a brief exchange between the interlocutors in lines 17–19); of note are the numerous connectives such as and, so, and because that Joan uses to mark continuations within her informing. The expression the thing is…, while having meager semantic content and without itself being declinatory, enables Joan to announce and frame the background and reasons for declining Heatherton's suggestion, and to delay the production of the ultimate gist of the declination to the very end of the turn. Couper-Kuhlen Reference Couper-Kuhlen2001 observes that the formula the thing is… “signals that the turn's business is complex and thus projects a multi-unit turn.” The data yielded other constructions with similar interactional uses, including the thing is though…, the only thing is…, the circumstances are…, and the fact of the matter is….

Another recurrent subtype of (a) is the “pseudocleft,” a copular construction in which the subject phrase consists of a what-clause followed by a be-COPULA, typically is:

(e)

The pseudocleft is increasingly receiving attention among interactional linguists as a highly strategic device for framing and projecting some social action in the interest of achieving a wide range of interactional objectives; this construction has been described as manifesting an extremely variable structure, in which the grammatical relation between what Hopper (Reference Hopper, Pütz, Niemeier and Dirven2001: 112) calls the “pseudocleft piece” (the first part, beginning with what and ending with an optional is) and the ensuing Z is not fixed, with Z having indeterminate length and structure (Hopper Reference Hopper, Pütz, Niemeier and Dirven2001, Reference Hopper2004; Hopper & Thompson Reference Hopper, Thompson and Lauryto appear). Among other interactional management functions, it has specifically been identified as a means for designing dispreferred responses (Kim Reference Kim, Downing and Noonan1995), and as functioning “in natural discourse to delay an assertion for any of a number of pragmatic reasons” (Hopper Reference Hopper, Pütz, Niemeier and Dirven2001:111).

A renewed inspection of a previously examined fragment yields an example:

(15)

As noted, the doctor's declination of the caller's implicit request for the former to come and see the patient was mitigated and rendered indirect through a counter-proposal, and the gist delayed by its placement in the final slot of the copular clause in line 40. It turns out that yet another way in which the doctor achieves delay here is by structuring the entire turn (lines 39–40) as a pseudocleft construction with a pseudocleft piece uWhat I'm tryin'a say, is, and slot Z incorporating first a purpose adverbial clause to save time (an example of a delay through pre-positioning of an adverbial), followed by a repair (as discussed previously), and ending with the copular clause the best thing tuh do is to call for an ambulance (line 40). Notice that the gist of the declination, call for an ambulance, is doubly delayed by first being placed in the final slot Z' within the copular clause (line 40), which in turn is embedded within Z as the turn-final predicate nominal of the parent pseudocleft construction (see Table 2).

table 2. Overall and Internal structures of excerpt (15).

This instance exemplifies the potential structural expandability of the pseudocleft, and the consequent possibilities for incorporating progressive delay of the onset of the gist of a dispreferred. Importantly, it also demonstrates a more general phenomenon whereby copular clauses are often found nested in structurally complex ways within an overarching copular clause, which can contribute synergistically to further delaying the gist of a dispreferred response.

In addition to the methods already discussed, the pseudocleft piece uWhat I'm tryin'a say, is renders the doctor's turn even more indirect in at least four ways. First, the pseudocleft piece contains no explicitly declinatory features. Second, it functions similarly to discourse markers (to monitor or manage talk), as discussed above. Third, it creates an anticipatory framework by gently projecting some talk to come. Finally, it introduces a distance and breaks the contiguity between the more “innocuous” pseudocleft piece and the upcoming declination, by placing them in separate clauses, with the gist of the dispreferred as far removed as possible from the pseudocleft piece. Such features can make the pseudocleft into a highly allusive vehicle for gently prefacing the declination component. Indeed, Hopper writes:

direct transcriptions of recorded speech point to pragmatic or rhetorical motivations rather than structural or strictly semantic ones as the functional basis of the English pseudocleft.

While it is possible to identify several such functions, they all derive from a single fact: The pseudocleft works to delay the delivery of a significant segment of talk. It accomplishes this by adumbrating (foreshadowing) the continuation in general terms without giving away the main point. (Hopper Reference Hopper, Pütz, Niemeier and Dirven2001:114; italics, original)

Kim Reference Kim, Downing and Noonan1995 also demonstrates the utility of a pseudocleft as a device for obliquely turning down an interlocutor's position without directly opposing it, by presenting one's own position as another alternative.

To conclude this section, the ostensible hurdle presented by relatively fixed word order in English does not appear to pose particular problems for participants to delay the production of declination components in dispreferred responses. As one “solution,” English speakers regularly deploy copular constructions (a), whereby a declination component can be delayed by positioning it in the turn-final slot. Moreover, in accordance with various interactional contingencies, speakers were found to creatively enlist a host of different sub-types, such as those beginning with the thing is (d), or others such as pseudoclefts (e), reversed pseudoclefts (b), and related constructions (c). What these share is the capacity for distancing the part that gently lays the groundwork for a forthcoming dispreferred (i.e., the first part of the copular construction prior to the optional copula) from the latter part (which can be tailored to carry the gist of the dispreferred). This capacity can be optimized by the possibility of expanding the first part (such as through an elaborate pseudocleft piece) as well as an even greater potential for an indefinite expansion of the latter part (slot Z), which can incrementally delay the arrival of the gist of the declination. Participant orientations to the overwhelming effectiveness of copular constructions as a delaying device were reflected in instances of repair, which showed the trails of attempts by speakers to modify or fine-tune the trajectories of emergent turns from those that perform a declination relatively early and directly into those that incorporate greater delay. The implementation of the kinds of repair dealt with here did not consist of just simple replacements or insertions such as those found in the previous section, but rather of the wholesale coopting of an emerging clause structure with some form of copular construction. Such instances of repair are, moreover, concurrently designed to augment affiliation with coparticipants, since forestalling devices are by and large not employed solely for the purpose of delay but typically incorporate measures to mitigate or render indirect an upcoming declination component.

CONCLUDING COMMENTS

The present study can be seen as a sequel to a previous article (Tanaka Reference Tanaka2005), which investigated how the delaying of dispreferred responses or the hastening of preferred responses in Japanese is accomplished in part through housing the gist of a response within a verb/predicate component, and through operating on the word order to position the component later for dispreferred responses or earlier for preferred responses. In comparison, it was argued that English conversationalists work within a linguistic system that appears to be more constrained by the relative immobility within clause structure of the main syntactic elements.

English speakers thus do not normally have freedom to vary the canonical word order of main syntactic elements to delay the appearance of the gist of dispreferred responses. However, where items are brought forward in time to delay a dispreferred, they overwhelmingly tended to be syntactically nonessential yet relatively mobile items such as adverbials, discourse markers, and epistemic expressions. In other words, English conversationalists do operate on word order in this rather restricted sense to postpone the onset of the dispreferred content. It should be emphasized, however, that these objects can play a key role not only as delaying devices, but also to variously frame or specify an upcoming declination, or to mitigate and render more indirect a declination component.

However, given that word order variability cannot adequately explain how the gist of dispreferreds is delayed in English, attention was shifted to whether English syntax provides other means to accomplish the objective. Although by no means the only available turn shape, the copular construction {SUBJECT—COPULAR VERB—Z} – which can be tailored to house the dispreferred content in the turn-final slot Z – emerged as an overarching, flexible solution to the interactional need to maximize delay of an upcoming gist of a dispreferred response, while working within the constraints of English grammar. Crucially, the subject position and the final slot Z of the copular construction admit wide variation in terms of internal structure and scale of expansion, thereby providing extensive scope for performing nuanced interactional work prior to the appearance of the gist. On the one hand, the oft-noted structural complexity of dispreferred responses can be partly explained by the possibility of designing copular constructions with elaborate internal structures, including various types of cleft constructions, the nesting of multiple copular clauses, and the embedding of relatively syntactically mobile items, including adverbials, discourse markers, and epistemic expressions. Seen from another angle, the previously reported utility of the pseudocleft, the reversed pseudocleft, and other types of cleft constructions for the implementation of dispreferred responses makes sense when these are regarded as special cases of the copular construction.

To repeat, Japanese speakers rely heavily on the grammatical resource of word order variability to house a dispreferred content in a turn-final predicate, whereas English syntax provides a ready-made, predicate-final syntactic structure in the form of the copular clause, which offsets the potential constraints that may be posed by the low degree of word order variability. Thus, even though English and Japanese word orders have sometimes been described as “mirror images” (e.g., Takezawa & Whitman Reference Takezawa and Whitman1998:104), the copular construction in English has an uncanny resonance with some of the features of dispreferred responses in Japanese: Not only do both have a predicate-final word order, but the facility for indefinite internal expansion allows participants to set the background and engage in preliminary contextualizing work prior to the production of the dispreferred content.

This article has taken as a point of departure the seemingly universal practice of delaying dispreferred responses, and it has investigated how participants use divergent linguistic resources in Japanese and English to achieve similar interactional ends. Through scrutiny of the grammatical structures of dispreferred responses in English, a close correlation was observed between the fundamental grammatical resources available in the respective languages and the kinds of operations routinely enlisted for the deeply social task of delaying declinatory elements. It can be seen that the language-specific organization of grammar is being mobilized for interactional ends to enable a context-sensitive operation of the context-free organization of preference. Plans for future research include closer investigation of the structure of dispreferred responses in English and extension of the current study to preferred responses in English. Finally, it is hoped that the comparative perspective adopted here may stimulate further cross-linguistic investigations into the interpenetration of grammar and interaction in the realization of dispreferred responses, as well as various other practices in interaction.

APPENDIX: ABBREVIATIONS USED