Background

Dementia is a life-altering diagnosis faced by millions of individuals and families worldwide. Dementia describes a variety of progressive symptoms affecting a person's ability to function. Symptoms can affect many domains of life, most often impacting memory and cognition. 564,000 Canadians were living with dementia as of 2016 with an estimated 25,000 new cases expected to be diagnosed each year. By 2031, it is projected that 937,000 Canadians will be living with dementia (Alzheimer Society of Canada, 2018). There are several different types of dementia: Alzheimer's dementia, vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, mixed dementia, frontotemporal dementia, and dementia of Parkinson's disease, just to name a few. Alzheimer's dementia caused by abnormal deposits of beta-amyloid plaques and tau tangles accounts for at least 60% of all cases of dementia (Lau and Brodney, Reference Lau and Brodney2018).

The progression of symptoms experienced by a patient with dementia is unique; however, most individuals with Alzheimer's dementia progress through three stages: early, middle, and late. With no curative or highly efficacious treatment options, dementia as a disease state is inevitably progressive (Lau and Brodney, Reference Lau and Brodney2018). Affected individuals will require a variety of support and assistance through each stage of dementia, with most individuals in the late stage relying on full-time assistance for activities of daily living. For family and caregivers, the emotional, physical, and financial responsibility involved with caring for a loved one with dementia can be extraordinary.

For decades, palliative care teams have specialized in symptom management and end-of-life care. As experts in optimizing the quality of end of life, it is interesting that the role of palliative care in dementia management is not yet well elucidated. To date, it is not standard of care to involve a palliative care team when a patient is diagnosed with dementia, and that's why this review was initiated to assess the evidence to support or refute the benefits of palliative care (Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Froggatt and Connolly2016). Dementia may solely be seen as a neurodegenerative condition, which may cause management to exclusively involve either neurologists and/or allied health professionals (e.g., occupational therapists and social workers). While this is appropriate — it is not comprehensive. Discrepancies exist in longitudinal care, including but not limited to prescription habits and admission rates. It is evident that dementia is a progressive condition that can result in symptoms analogous to those afflicted with terminal malignant illnesses, as seen in palliative care patient population. This is why it is crucial to involve aspects of palliative care medicine and broaden the scope of practice when dealing with patients with dementia. It is a detriment to the patient, as well as the family and/or caregivers, to not implement palliative practice and utilize limited resources. With this progressive disease affecting over 35.6 million individuals worldwide and no curative option on the horizon, the time is now to understand if palliative care improves the symptoms and care of patients with dementia (Alzheimer Society of Canada, 2018).

Objective

The aim of this systematic review was to understand the impact of palliative care in dementia management.

Methods

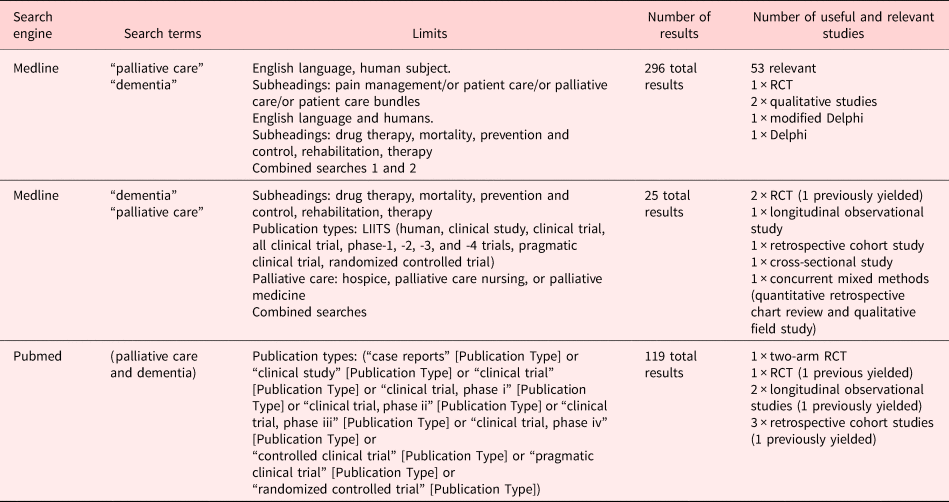

We used Medline and PubMed and searched for (“palliative care” or “dementia”) and “palliative care and dementia” with limits on the date from January 1, 1998 to October 2017. This yielded 440 total results and 73 relevant publications ranging from op-ed pieces to qualitative studies, to randomized control trials (RCTs) (there were really only three), to prospective cohort studies, as well as theoretical trial designs. Of these, only 14 were deemed to be useful and relevant to the objective at hand. These articles were then read, and the relevant points and themes were summarized. Corroborative themes were identified, and the authors responsible for the contributing research were cited as they came up. Additional sources were added to the literature search by way of being referenced in the article. We used The Cochrane Collaboration — Systematic Reviews of Health Promotion and Public Health Interventions Handbook to structure this review. Given that this is a systematic review, no approval of a research ethics committee was required.

Inclusion criteria

The systematic review was conducted using a prospective study protocol, defining the inclusion criteria as studies assessing an association between palliative care and dementia management outcomes. Eligible studies included adults (19 plus years) of either gender, with a diagnosis of dementia (any subtype and all stages). Studies had to be on humans and in the English language. We included single-blind cluster RCT, two-arm parallel cluster RCT, unblinded RCT, observational studies, retrospective cohort studies, cross-sectional studies, concurrent mixed methods study, qualitative study, and Delphi studies.

Exclusion criteria

For the purpose of this review, studies that were not in the English language were excluded. Studies, not on humans and population younger than 19 years old with a diagnosis of dementia (any subtype and all stages), were omitted as well. Duplicated studies were not included. In addition, study designs that did not involve RCT, theoretical study designs, or prospective cohort studies were excluded.

Identification of studies

The systematic computerized literature search of published studies was carried out between October and December 2017. The search was conducted in Medline from October 10, 2017 to October 30, 2017, in Cochrane from November 3, 2017 to November 21, 2017, and in PubMed from December 1, 2017 to December 29, 2017 using the following search terms: “dementia” and “palliative care or palliative” or “dementia and palliative care.”

Data extraction and statistical analysis

Data from each study were extracted using a standardized protocol to assess study design, outcomes, limitations, and author's conclusions. A standardized abstraction form was used (Figure 1), and the two reviewers were not blinded to the study hypotheses.

Fig. 1. Standardized abstraction form.

Results

Identification of studies

The search strategy outlined yielded 440 total publications in Medline and PubMed. No additional relevant studies were found in the Cochrane library. The evaluation of the 440 publications is shown in Figure 2.

Fig. 2. Evaluations of publications.

Discussion

Main findings/results of the study

Despite the incredible amount of people affected by dementia, it was surprising to find limited high-quality data addressing this key topic. A few common themes (Figure 3) were identified in reviewing the available literature.

Fig. 3. Common themes. RCT, Randomized clinical/control trial; GOC, goals of care; EOL, end of life; QOC, quality of care; QOL, quality of life; PC, palliative care; UC, usual care; ACP, advance care plans; NH, nursing home; AHR, adjusted hazard ratio; ER, emergency room.

Goals of care and end-of-life conversations

As individuals' progress through the stages of dementia, cognition, and the capacity to make informed decisions is often lost, with few individuals creating advanced care plans outlining their specific wishes, families are often left to make decisions regarding goals of care and end-of-life care. Palliative care places a focus on having these vitally important discussions addressing goals of care and end-of-life care. Hanson et al. (Reference Hanson, Zimmerman and Song2017) noted that using a goals of care video aids along with structured end-of-life discussions as part of a palliative care intervention led to a statistically significant increase in concordance between family decision-makers and clinicians at 9 months of follow-up or at death (133 [88.4%] vs. 108 [71.2%], p = 0.001). Hendriks et al. (Reference Hendriks, Smalbrugge and Hertogh2017), however, highlighted that creating advanced care plans may not be enough. They noted that 21% of nursing home patients with dementia were hospitalized despite a “do not hospitalize” order, underscoring the importance of healthcare provider education around respecting an advanced care plan or specific palliative goals (Hendriks et al., Reference Hendriks, Smalbrugge and Hertogh2017). Sampson et al. (Reference Sampson, Jones and Thune-Boyle2011) noted another interesting theme surrounding advanced care planning; despite its benefits for those with advanced dementia, throughout their study, there was a reluctance from patients and family members in making these advanced care plans (Sampson et al., Reference Sampson, Jones and Thune-Boyle2011). Perhaps, this reluctance could be mitigated by discussing disease trajectory (Figure 4). Evidence shows that discussing disease trajectory and what to expect helps patients and their caregivers be more willing to accept palliative care in advanced stages and improves satisfaction with the care (Teno et al., Reference Teno, Lynn and Phillips1994).

Fig. 4. Disease trajectory of a chronic life limiting illness like dementia (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Kendall and Boyd2005).

Prognostication

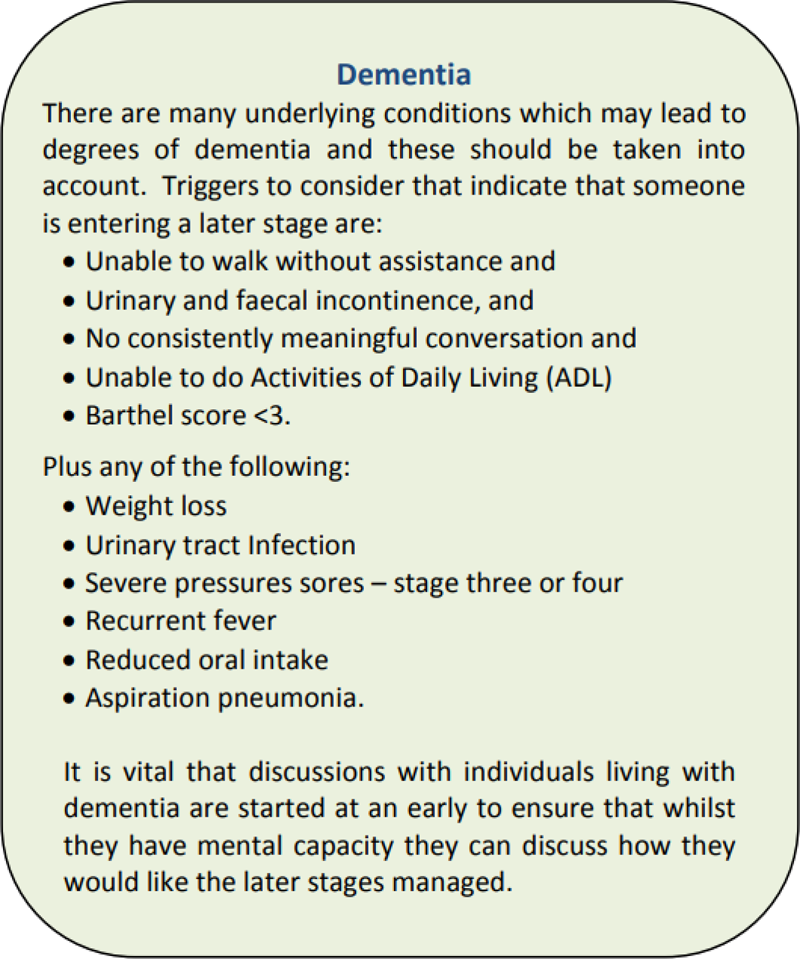

Adding complexity to end-of-life planning is the lack of a reliable prognostication tool in dementia. Brown et al. (Reference Brown, Sampson and Jones2013) reviewed prognosticators in patients with advanced dementia and found that the Functional Assessment Staging 7c criterion was likely not a reliable predictor of 6-month mortality. Their systematic review concluded a lack of prognosticator concordance across the literature (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Sampson and Jones2013). Similar to the Functional Assessment Staging 7c criterion, the palliative performance scale is an assessment tool used by clinicians to assess functional status and to prognosticate. The tool was initially validated amongst oncology patients where it is a reliable predictor of survival. Unfortunately, this was not reflective in the dementia community. When compared, a low palliative performance scale (<20) indicated short prognoses in malignant, nonmalignant, and dementia patients (survival <3 days, sensitivity 75%, and specificity 93%) but with higher palliative performance scales (>20), medium-term life expectancy was not reliably predicted in nonmalignant or dementia patients (Linklater et al., Reference Linklater, Lawton and Fielding2012). The Gold Standards Framework Proactive Identification Guidance (PIG) supports the use of the “surprise question” (Figure 5) in conjunction with general indicators of decline (Figure 6) and specific clinical indicators (Figure 7) to identify patients nearing the end of life (The Gold Standards Framework, 2010). The “surprise question” in a study did predict death better than intuition (53.2%, intuition = 33.7%; p = 0.001) but with a higher false positive rate. Unfortunately, similar to the palliative performance scale, the “surprise question” has been shown to predict death more accurately in patients with cancerous illness vs. noncancerous illnesses [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.79–0.87 vs. 95% CI: 0.73–0.81, respectively; p = 0.02] (Downar et al., Reference Downar, Goldman and Pinto2017; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Senior and Rhee2018). Echoing indicators of decline, such as hypoalbuminemia and weight loss, the Functional Assessment Staging 7c criterion did find anorexia [hazard ratio (HR) 2.22; 95% CI: 1.52–3.44], dry mouth (HR 1.81; 95% CI: 1.23–2.67), and cachexia (HR 1.27; 95% CI: 1.3–1.55) to be associated with increased mortality at 6 months (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Sampson and Jones2013). The PIG framework challenges the notion of exact prognostication and instead proposes predicting need as being more valuable than prognostication of exact time remaining. Whether prognostication or identifying need helps patients and/or families living with dementia, placing a palliative care focus in the early stages of the illness is essential to ensure that patients and families are aware of the importance of goals of care, end-of-life planning, and disease trajectory (The Gold Standards Framework, 2010).

Fig. 5. The surprise question (The Gold Standards Framework, 2010).

Fig. 6. General indicators of decline (The Gold Standards Framework, 2010).

Fig. 7. Specific clinical indicators for dementia (The Gold Standards Framework, 2010).

Symptom management

A common theme in the literature was patients and family's impression that symptoms were generally poorly managed in patients with dementia, particularly advanced dementia. When the symptoms of patients dying with cancer were compared to that of patients dying of dementia, there were no statistically significant differences in moderate to severe dyspnea (dementia: n = 28, 49% vs. cancer: n = 33, 61%; p = 0.28) and moderate to severe agitation (dementia: n = 4, 7% vs. cancer: n = 12, 23%; p = 0.09) (Soares et al., Reference Soares, Japiassu and Gomes2018). It is standard practice to involve palliative care for the management of end-of-life symptoms in cancer patients; however, it is not for patients with dementia despite evidence that both groups experience severe and comparable symptoms. Mean scores in Sternberg et al.’s (Reference Teno, Lynn and Phillips2014) retrospective cohort study indicated poor management of patients with dementia in areas of pain, shortness of breath, fear, and skin breakdown. Sternberg et al. noted that pain and agitation were the most common symptoms, advanced dementia being associated with more pain. They also noted that symptom management only intensified at the end of life (Hendriks et al., Reference Hendriks, Smalbrugge and Hertogh2017). Both studies indicate that a priority should be placed not only on educating healthcare providers but also on providing focused symptom control throughout all stages of dementia management.

Interestingly, dysphagia was sparsely discussed as a priority in symptom management through the literature reviewed in this study. Dysphagia is a symptom which can lead to aspiration pneumonia, laryngospasm, and lung abscess. Given that aspiration rates are significantly higher in the dementia population [35.6% of patients with dementia vs. 6.7% of controls (χ 2-test; χ 2 = 9.895; df = 1; p < 0.01)] (Rosler et al., Reference Rosler, Pfeil and Lessmann2015), and aspiration pneumonia is the leading cause of death in the dementia population [odds ratio (OR) 2.891; 95% CI: 1.459–5.730] (Manabe et al., Reference Manabe, Mizukami and Akatsu2017), it is critical that a palliative care approach be taken where managing symptoms like dysphagia and dyspnea would be a priority.

Dementia is a particularly devastating diagnosis for it not only causes an onslaught of physical symptoms but also responsive behavior of dementia which is not as thoroughly discussed in the literature. We know that responsive behavior of dementia can be challenging to treat and distressing to patients and their loved ones. Passmore et al. (Reference Passmore, Ho and Gallagher2012) suggested that a palliative care approach which recognizes the importance of personhood and preservation of dignity would bridge the current gap which exists in providing care to patients with the complex biopsychosocial constellation of symptoms caused by advancing dementia (Passmore et al., Reference Passmore, Ho and Gallagher2012).

Emergency room visits

Emergency room visits can not only be lengthy and tedious for patients, but they place a major burden on our healthcare system. Rosenwax et al. (Reference Rosenwax, Spilsbury and Arendts2015) compared the use of the hospital emergency room by people with dementia who did and did not have access to community-based palliative care. Through their retrospective cohort study, they concluded that community-based palliative care was associated with significant reductions in hospital emergency room use. In fact, patients without access to community-based palliative care visited the emergency room 1.4 times more often in the first 3 months of study (95% CI: 1.1–1.9) with 6.7 times more visits in the weeks immediately preceding death (95% CI: 4.7–9.6). The most frequent emergency room presenting complaints included shortness of breath, altered conscious state, confusion, and nausea/vomiting (Rosenwax et al., Reference Rosenwax, Spilsbury and Arendts2015). Given the evidence that aspiration pneumonia is the leading cause of death in the dementia population, the leading emergency room chief complaint of shortness of breath was suspicious for possible aspiration pneumonias, another indication that perhaps dysphagia is not being optimally managed without standardized palliative care interventions in place (Manabe et al., Reference Manabe, Mizukami and Akatsu2017). By improving access to palliative care services for patients with dementia, it could not only spare patients and family members the time and distress of an emergency room visit but would better utilize healthcare resources.

Prescribing behavior

Prescribing behavior surrounding patients with advanced dementia was another theme identified through two studies in this review. Prescribing patterns are particularly important given the potential for polypharmacy and prescribing cascades that can occur with this medically complex population (Figure 8).

Fig. 8. Prescribing cascade (Rochon and Gurwitz, Reference Rochon and Gurwitz1995, Reference Rochon and Gurwitz1997).

Holmes et al. (Reference Holmes, Sachs and Shega2008) questioned the safety and appropriateness of medications prescribed to those with advanced dementia. They found that, on average, 6.5 medications were prescribed per person with 6 of 34 patients (18%) prescribed 10 or more daily medications. The study evaluated medications being used at the end of life and determined appropriateness based on how the medication affected quality of life and improved pain and symptom management. Twenty-nine percent of patients in this study had been prescribed a medication considered to be “never appropriate” based on the modified Delphi process (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Sachs and Shega2008). Common medications deemed to be “never appropriate” included cholesterol-reducing agents, bisphosphonates, certain antiarrhythmics, and anticholinergics (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Sachs and Shega2008). Palliative care specializes in streamlining and discontinuing medications that do not align with patients' identified goals of care. With more standardized involvement of palliative care consultation, discontinuation of these “never appropriate” medications at end of life could not only improve the quality of life but would reduce the potential for unnecessary side effects and adverse reactions experienced by the patient.

There is also a financial benefit to palliative care consultation in the dementia population. Araw et al. (Reference Araw, Kozikowski and Sison2015) compared the pharmacy cost before and after palliative care consultation in patients with end-stage dementia and found a statistically significant decrease in medication cost following palliative care consultation ($31.16 + 24.71 vs. $20.83 + 19.56; p = 0.003). There was a shift in the medications prescribed with a significant difference in the number of patients taking analgesics before and after palliative care consultation (55 vs. 73.3%; p = 0.009), and an average daily antiemetic cost showing moderate increase from pre- to post-palliative care consultation ($0.08 + 0.37 vs. $0.23 + 0.75, p = 0.047). These findings show that palliative care consultation aims to optimize the types of medications prescribed to patients, with more emphasis on symptom control but overall leading to a reduction in pharmacy costs (Araw et al., Reference Araw, Kozikowski and Sison2015). This supports the multifaceted benefit on prescribing practices shown when palliative care consultation is implemented in the management of patients with dementia.

Strengths and weaknesses

This study provides a comprehensive review of the evidence surrounding the benefits of palliative care in dementia management. It looks at multiple aspects of dementia care including symptom management, emergency room visits, prognostication, and incorporated evidence focused on patient and family member outcomes and views.

Strengths of the studies used in this study involves that the majority of the articles were RCT study designs, the involvement of metrics in the form of scales, outcomes not only limited to patient themselves but families as well which provides a wholesome perspective and addressing levels of management with transitions to different settings. In addition, the studies used can be applicable to dementia patient populations in a generalized fashion, allowing for reproducibility.

Despite the strengths of the studies in which this article was built on, there are weaknesses. These include studies with attrition biases, underpowered, lack of discernable CIs, and p-values.

What this study adds

There are changes to education and practice that can be applied from the knowledge gathered through this review. Palliative care interventions and an emphasis on palliative care in the healthcare education curriculum should be prioritized and implemented to improve the level of care provided to patients with dementia. There is a grave need to improve understanding and respect for goals of care. A priority should also be placed on educating providers around recognizing and appropriately managing symptoms throughout all stages of dementia, particularly in areas of pain, dyspnea, dysphagia, agitation, fear, and skin breakdown.

We know that providing access to palliative care services for patients with dementia can reduce emergency room visits and thus should be encouraging implementation of palliative care services at earlier stages of the disease trajectory to better utilize healthcare resources and improve the experience of patients and families. Improving education around appropriate prescribing and the risks of the prescribing cascade can not only emphasize symptom control but potentially lead to a reduction in pharmacy costs and drug-related complications in this population.

We acknowledge that there is currently no reliable prognostication tool validated for use within the dementia community. The Functional Assessment Staging 7c criterion was determined to be an unreliable predictor of 6-month mortality. A palliative performance scale is an assessment tool validated amongst oncology patients and used by clinicians to assess functional status and to prognosticate. It is a reliable predictor of survival but unfortunately does not reliably prognosticate for patients with dementia. The Gold Standards Framework Proactive Identification Guidance (PIG) supports the use of the “surprise question” along with general indicators of decline to identify patients nearing the end of life, despite its higher false positive rate.

Finally, understanding the views of healthcare providers regarding possible fears, uncertainties, and/or biases in the management of advancing dementia might also help target appropriate education. With only 57% of palliative care recommendations being implemented, integration of palliative care consultation will only be impactful for the patient if we understand the possible biases or preconceptions surrounding palliative care, palliative care consultation, and palliative care recommendations.

Conclusions

Although the body of literature to support or refute thematic conclusions is not large, a trend toward benefit can be concluded. Four key themes were identified in this review: goals of care and end-of-life conversations, symptom management, emergency room visits, and prescribing behavior. In each domain, palliative care consultation has either showed benefit or was postulated to have benefit if implemented. Discussion of goals of care and end-of-life care involving palliative care consultation showed greater concordance between family decision-makers and clinicians; access to palliative care led to a reduction in emergency room visits; and palliative care consultation resulted in a total reduction on medication/pharmacy costs. This review highlighted the gaps, however, in the standard of care provided to patients living with dementia; suboptimal management of symptoms and healthcare provider education being leading issues. Although the severity of symptoms from advancing dementia can be compared to terminal cancer, the same emphasis and importance on palliative care consultation and symptom management have not yet been paralleled in the dementia population (despite the severity of symptoms is analogous to malignant terminal illnesses, not much of an emphasis is being placed on dementia management which is a growing problem in the realm of aging population, wide spread and merits the same proactivity). The World Health Organization alongside the International Palliative Care Initiative of the Open Society Foundations identified palliative care as a public health issue and together created the “Roadmap for Palliative care” which outlines tasks and obstacles that must be overcome before palliative care can be successfully instituted. The roadmap highlights four key domains to be addressed: policy, education, drug availability, and implementation indicators. This roadmap could be used to provide a skeleton framework for integrating palliative care into the care of dementia patient's worldwide and underlines the significance of this systematic review as an initiative.

Future research

We highlighted a reluctance to complete advanced care planning but were unable to identify underlying reasons. Additional studies are needed on this topic. Appropriately designed studies with valid qualitative analysis would yield additional power. Future research targeted toward understanding patient and caregiver apprehension in undertaking this task could elicit solutions to overcome these barriers, promoting earlier advanced care planning. We speculate that prognostication would benefit patients and families living with dementia, however, without a validated and reliable tool, prognostication becomes extremely challenging in this particular population. A lack of a valid quantification tool for assessing dementia further highlights a need for an appropriate metric. If a tool similar to the palliative performance scale was created and validated, its use could become as ubiquitous as the palliative performance scale, equipping healthcare providers with a simple way of prognosticating for patients with dementia. On the contrary, The Gold Standards Framework which emphasizes identifying need over true prognostication should be considered. Perhaps, a study comparing each approach (identifying need vs. prognostication) and the resulting impact on patients and families would best clarify this aspect of dementia management. Finally, understanding the overall benefit of palliative care in the dementia population requires larger RCTs with longer follow-up across different settings (inpatients/outpatients) to solidify the themes and trends outlined in this review.

Limitations

The previously defined search criteria of this review yielded 14 useful and relevant studies, of which the only three were RCTs. Thus, the review is based on a small number of studies and insufficient data, most of which were retrospective and qualitative in nature. There was heterogeneity with respect to endpoints and outcomes and in the classification of severe and advancing dementia in the studies reviewed which limits our ability to corroborate other themes that arose or to undertake a meta-analysis. Publication bias should also be taken into consideration.

Authorship Statement

Conception and Design: Dr. Helen Senderovich.

Analysis and Interpretation of Data: Dr. Helen Senderovich and Dr. Sivarajini Retnasothie.

Drafting of Paper and revising it critically: Dr. Helen Senderovich and Dr. Sivarajini Retnasothie.

Final Approval of Version to be published: Dr. Helen Senderovich.

Accountable for all aspects of the work: Dr. Helen Senderovich and Dr. Sivarajini Retnasothie.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951519000968.

Acknowledgments

We thank Akash Yendamuri (MD) for his contributions in the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

This review received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflict of interest to declare.