Revolutions are the locomotives of history.

—Karl MarxEvery revolution, be it political, economic, social, or aesthetic, is, in the last analysis, a technological revolution.

—Villém FlusserIn 1924 the self-taught artist Iurii Nikolaevich Rozhkov created a series of photomontages inspired by Vladimir Maiakovskii's propagandistic ode to labor, “To the Workers of Kursk,” and the geological discovery of the Kursk Magnetic Anomaly (KMA).Footnote 1 The series was first shown at the “Twenty Years of Work” exhibition in January 1930, which the poet himself curated. In the exhibition catalogue, Maiakovskii made note of Rozhkov's work as: “A temporary monument. Rozhkov's montages. To be printed.”Footnote 2 Two months after the exhibition Maiakovskii committed suicide. Rozhkov's photomontages remained unpublished during his lifetime.Footnote 3

Although a nonprofessional artist, Rozhkov was well informed about modern graphic art and innovations in the burgeoning Soviet visual culture.Footnote 4 In the 1920s, he shared the ideology of the “Industrial Art” movement, which sought to merge art that capitalism had separated from crafts, with material production based on highly-developed industrial machinery. He quickly embraced photomontage, the new artistic technique celebrated by the various artists associated with Lef, as the most suitable means for communicating the progressive revolutionary message.Footnote 5 Due to his distinctive method and approach to montage, however, the quality of Rozhkov's work is unlike that of other graphic artists. His compositions, which often incorporate angular “cubo-futurist” forms, are inventive artistic idioms composed of typographic, photographic, and pictorial-illustrative materials, whose sole target is not only propaganda, but also aesthetically innovative and richly conceived metaphor.

The aim of this article is, first and foremost, to introduce Rozhkov's lesser-known photomontage series as a new model of the avant-garde photopoetry book, which offers a sequential reading of Maiakovskii’s poem and functions as a cinematic dispositive of the early Soviet agitprop apparatus.Footnote 6 Second, it illustrates how Rozhkov's photomontages for Maiakovskii's ode to labor are more than mere examples of the sharp political propaganda of the reconstruction period of the NEP era, dominated by economic and industrial themes.Footnote 7 They herald the joyous and genuine expression of the enthusiasm for production and revolutionary faith in a better future, articulated both as the struggle against backwardness and the thirst for technical and industrial modernity. Their main function was seen not as propaganda, but rather the production of reality through its aesthetization. Further, I will examine the visual devices that Rozhkov employs in his photomontages to render—following Maiakovskii's verses—a sharply polemical and satirical response to all those who relentlessly criticized and attacked the Lef authors and their progressive ideas. The conclusion proposes that the photopoem itself converts into an idiosyncratic avant-garde de-mountable memorial to the working class. The photopoem acts not only as a document of its own revolutionary era, but also as an example of the alternative cinematic dispositive through which the early agitprop apparatus is realized in lived experience, reproduced, and transformed, thus delineating its shift towards the new dispositif of the late 1920s—socialist realism.

The Avant-garde Photopoem as Agitprop Cine-Dispositive

The avant-garde photopoetry book forces both high and low genres into a “scandalous” identity. In the Russian avant-garde, this marriage between poetry (recognized as the high art that privileges originality) and photomontage (recognized as a reproductive form of mass culture rather than art) was ideologically motivated. As theoretician of Russian constructivism, Boris Arvatov, wrote in his 1922 programmatic article “Agit-cinema”: “There is no ‘high’ or ‘low’ art for the working class; the proletariat knows only progressive, revolutionary art and the backward, extinct, reactionary art.”Footnote 8 Arvatov recognized all artistic means based on technological reproduction, including photomontage, as perfect utilitarian forms of visual art in the epoch of proletarian dictatorship—the most suitable for propaganda: “Agitation is first and foremost a tool for transforming reality. Representational agitation must present this transformation completely immediate, by itself.”Footnote 9 For Arvatov, agitation is “a pragmatic activity”; although its principal condition is the “dynamism and hyperbolism of action,” it nevertheless should be comprised only of contemporary material, of “real people and things”:

Realism of materials and flamboyancy of action—that's what is needed.

Flying trains, running skyscrapers, airplane strikes or things rebelling are suitable themes not only because they are amusing, but also because of the possibilities they grant: to take the existent and do with it whatever one wants.

America was for mere amusement.

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) must impart a purposeful, social meaning to amusement.Footnote 10

Maiakovskii was also aware of the political importance of agitation. His avant-garde ode “To the Workers of Kursk,” written in November 1923 and published in January 1924, represented an attuned response to the task of industrial propaganda in the reconstruction period and emerging practices of commemoration.Footnote 11 In his short article titled “Agitation and Advertising” (1923), published in a small Ekaterinburg magazine, Maiakovskii writes: “We know well the power of agitation. Nine-tenth of every military victory, of every economic success, belongs to the ability and the strength of our agitation.”Footnote 12 If his ROSTA (Russian Telegraph Agency) Windows aided the military success of the Red Army in the Civil War, his ideologically-engaged poetry of didactic propaganda was meant to support the economic revival of the emerging Soviet state. In tune with Arvatov's account on agitation as a “pragmatic activity” and “a tool for transforming reality,” Maiakovskii's “To the Workers of Kursk” and Rozhkov's subsequent photomontages both represent expressions of three large agitation projects: monumental, industrial, and political propaganda.

Early Soviet agitation propaganda is an illustrative example of Foucauldian dispositif, since it both comprises and is comprised of a network of discourses, institutions, regulatory decisions, administrative measures, pieces of knowledge and values that are reciprocally linked, defined, and governed by strategies of management of power.Footnote 13 Moreover, early Soviet agitprop produced various dispositives, such as agit-trains, newsreels, ROSTA posters, wall newspapers, advertisements, and photo-books, which in turn transformed the agitprop apparatus into a number of real, concrete, experiential forms.Footnote 14 Rozhkov's photopoetry book, I argue, was conceived as an agitprop cine-dispositive.

Marked by the proliferation of signifiers, Rozhkov's photomontages for Maiakovskii's “To the Workers of Kursk” are a unique case among the emerging photopoetry experiments of the 1920s, or so-called alternative cinematic dispositives. Following Pavle Levi's concept of “cinema by other means,” I suggest that Rozhkov's series can be understood as a cinematic dispositive, or what El Lissitzky envisioned as a “bioscopic book.”Footnote 15 The materiality of the medium plays a key role in this vision: the bioscopic book transforms a mere object into a concrete piece of “technology” due to its operational body, that is, due to its continuous page-sequence and the dialectics inherent to the montage of the poetic text and photomontages. In other words, such a dispositive is sequential and cinematic, and involves a spatial arrangement (topology) of items and ideological concepts and a narrative sequence (series of defined events).Footnote 16

The pictorial saturation, graphic intensity, and visual—both iconic and indexical—satiation are the most apparent characteristics of Rozhkov's entire series.Footnote 17 It is as if the reader/viewer of Rozhkov-Maiakovskii's photopoem is thrown amidst the Kracauerian “blizzard of photographs,” trying to orient him/herself vis-à-vis this whirlwind of images, thus attempting to discern what it means to be a social subject through visual reasoning.Footnote 18 Here the words and letters themselves become images: the dynamically arranged and heterogeneous typographic text in Rozhkov's series functions as an active and organic visual insert.Footnote 19 One finds a similar synthesis of text and photography in Gustav Klutsis’ propaganda posters, Aleksandr Rodchenko's commercial advertisements, and film posters during the 1920s and early 1930s in Soviet Union, but not in most photopoetry books.Footnote 20

Rozhkov pushed the photo-book model proposed by Rodchenko in About This (Про это, 1923) even further toward an inventive symbiosis of text and photomontage, consequently bringing its page in close proximity to the poster and cinema.Footnote 21 Rozhkov was the ideal reader of Maiakovskii and Rodchenko's collaborative work; Rozhkov the consumer of Lef editions became Rozhkov the producer, both programmer and designer, an active “influencing machine,” an agitprop prosumer.Footnote 22 Rozhkov's series exemplifies the often-repeated claim by media archeologists that any pair of dispositives—an essential part of which is a prosumer who simultaneously acts as a consumer, producer, “middleman,” channel, or medium—can translate, remediate, metamorphose, and incorporate each other, and through this process redefine themselves and one another.

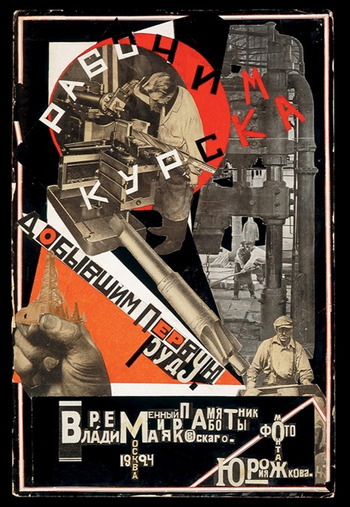

Rozhkov intended the front cover of the unreleased agit-book to be a poster-like illustration of the poem's lengthy title: “To the Workers of Kursk, Who Extracted the First Ore, A Temporary Monument of Work by Vladimir Mayakovsky” (Figure 1).Footnote 23 As a successful conflation of visual images and typography reinforced by different shapes and colors, Rozhkov's cover design distinctly conveys the title of Maiakovskii's poem while playfully suggesting meanings beyond it. The color choice for the topographical layout of the words “To the Workers of Kursk” (РабочиМ КурсКА) guides the viewer's perception to the letters painted in red (KMA), which stand for the largest magnetic anomaly on Earth—Kursk Magnetic Anomaly (Курская Магнитная Аномалия)—a territory rich in iron ore located near the Russian border with Ukraine, which Lenin had been eager to excavate since 1919.

Figure 1. Yuri Rozhkov: To the Workers of Kursk (1924), front cover photomontage. Collection of the State Literary Museum (GLM), Moscow. Courtesy of Kira Mattisen.

The acronym is accompanied by the photographic images of engineers and workers, machines and tools. Both hard-working laborers and skilled engineers are represented as “serving” the same cause: by working in the mining industry, they are aiding the country's industrial and economic revival and, eventually, raising the standard of living in the nascent Soviet Union. As historical geographer Grey Brechin reminds us, mining engineers and historians repeatedly claimed that miners were the true vanguard of progress. To the merchant's oft-repeated cliché “commerce follows the flag,” the champions of mining added the condition “but the flag follows the pick.”Footnote 24 The close association of mining with warfare, according to Brechin, is even more ancient than the idealized relationship between agriculture and morality. Unlike farmers, miners toil in a lightless and timeless realm of extreme danger and hardship. If agriculture is feminine and fecund as symbolized by Demeter and Ceres, then testosterone characterizes mining, whose gods are of the underworld.Footnote 25 Rozhkov's first photomontage exposes these observations, taking us to the realm opposite that suggested by Rodchenko's front cover for About This. If the image of Lili Brik—at least partially—denotes the feminine realm of petty-bourgeois everyday life (meshchanskii byt), Rozhkov's front cover is a composite of images dominantly masculinized and mechanized.Footnote 26

The powerful technical machinery plays a vital topological and tropological role in the photomontage: it occupies the center and introduces the importance of technology within the narrative of the photopoem. Zooming in on the diagonally displayed image of the counterbore, one can easily recognize the following inscription on the mechanical tool: “№ 2 The National Tool Co. Cleveland Pat. Jan. 30. 1912.” It is important here to recall Arvatov who emphasized that the new Soviet state had to “impart a purposeful, social meaning” to everything that would come from America, including the technology itself. Technology—tools, machines, and technological knowledge—appears to be liberated from any ideology. Yet according to Arvatov, this is an illusion perpetuating what Karl Marx called “false consciousness”; what is obscured is that this is the technology of private-property production, enabling the capitalist status quo:

This technology, limited by the framework of individual capital or middle-sized shareholding capital (the mode of production in most countries even to this day), manufactures things for individual consumption, i.e., things not connected to each other, separated, Thing-commodities. Production works for the market and therefore cannot take into account the concrete particularities of consumption and proceed from them; it is forced, in the construction of things, to proceed from existing patterns of a purely formal order, to imitate them. The result is the complete and utter conservatism and stasis of forms.Footnote 27

Rozhkov's photomontage series proposed a similar idea to Arvatov's program of the reconstruction of everyday life: political agitation and propaganda would increase ideological consciousness of the socialist subjects, who as a result would grow invulnerable to the lure of capitalism and private ownership. Not coincidentally, the only monochrome photomontage in the series (because it represents miners toiling in the lightless realm of the underground) featuring the dominant diagonal image of the drill, echoes Rozhkov's front cover but with an important difference. While the counterbore on the front cover is inscribed with letters confirming its American origin, the drill on the monochrome photomontage bears the more noticeable acronym KMA. In other words, Rozhkov made an unequivocal ideological statement about the state building program of industrialization, following Arvatov's dictum. Agitprop—agitation propaganda—was Rozhkov's program, which focused on the dissemination of Marxist-Leninist thought and action applied by the Soviet state. The revolutionary potential of technology is rendered both through the rich visual content of the unpublished book and its very material form. The dynamism of the book's conceptual design turns Rozhkov's photomontage series into a specific piece of “technology”—cinematic dispositive—that resists the mentioned stasis of forms.

Revolution: Alternating Rhythm and Cinematic Sequencing

Rozhkov's innovative and experimental design attracted Maiakovskii's attention. Maiakovskii persistently urged artists to search for new means of expression. “Novelty. Novelty of material and device!”—he advocated.Footnote 28 The exceptionality of Rozhkov's photomontage series lies in his specific technique of merging typography with photography. In this regard, Rozhkov did something quite different from Rodchenko. While his precursor printed his photomontages in About This separately from the text of the poem, Rozhkov merged Maiakovskii's verses with the images and pasted them both on the same sheet, thus turning the verses themselves—words and letters—into images. The letters became the active optical elements, occupying the same visual level as the images themselves, resulting in a hierarchical backflip of the image-text relationship. In Rozhkov's photomontages, the image became superior to the text: it is not that images illustrate the poetry, but other way around—the poetry explains the images.

One of the reasons for this somersault in the text-image correlation is that Rozhkov modified Maiakovskii's stepladder (lesenka) layout while retaining the consistency of its verse lines. A verse line of Maiakovskii's lesenka, as the segment that is on the same horizontal typographical line, is synonymous with a “step” on the staircase.Footnote 29 Although Rozhkov sometimes pasted the cutout letters of the poem's text as lines that are not completely horizontal but usually slanted (similar to designs for advertisements and film posters), he consistently retains the same division of verse lines as in the printed version of the poem. Maiakovskii must have appreciated this feature of Rozhkov's photomontages, since the inherently melodic nature of the verse proposed by intonation was both maintained and altered by the visual organization of the verses. If the intonation was maintained within the specific verse lines, it was modified by the disappearance of lesenka. Consequently, Rozhkov's photomontages create a different tempo of reading the poem than that of Maiakovskii's lesenka. Rozhkov additionally anchored this parallel rhythm to the visually discernable segments, which were to organize and structure the apparent blizzard of images.Footnote 30

For Maiakovskii, it was paramount that the rhythmic organization of words in a poem should deliver musical impact. In his 1926 essay “How to Make Verses,” he emphasized the precedence of both line length and the “transitional words” that connect one line to the next. Maiakovskii urged his fellow poets to take advantage of all the formal possibilities available to them, or, as he put it, to give “all the rights of citizenship to the new language, to the cry instead of melody, to the beat of drums instead of a lullaby.”Footnote 31 If the poem was intended to reflect the dynamism of the new technological age, then, Maiakovskii insisted, its style and, even more, its formal structure and layout should be equally “energetic”; otherwise, the poem would merely echo the mawkish and old-fashioned conventions of the symbolist-romantic imagination, only to function on the thematic level.

Undoubtedly, Maiakovskii viewed the lesenka layout as the most suitable form for the expression of the new sensibility and dynamism of the modern age. The formal feature of Maiakovskii's verse fully corresponds to the technique of montage: the entire poem About This, for example, is constructed from diverse fragments as distinct sense-units. These rhythmically, semantically, as well as spatially and temporally remote fragments, are also visually marked by the margin titles printed in a thicker font, which function similarly to those still images with the text from the silent cinema (intertitles).Footnote 32 Maiakovskii used the same margin title device in the poem “To the Workers of Kursk,” dividing it into the three different parts—it was, it is, and it will be—which along with the unmarked prologue address, respectively: the tumultuous and revolutionary past, the present brimming with the inherited hardships and the vast potential for their defeat, and an optimal vision of the future.

Rozhkov was certainly aware of Maiakovskii's device, which Sergei Eisenstein acknowledged and praised much later in his essay “Montage 1938,” when he wrote that Maiakovskii “does not work in lines … he works in shots, verses … cutting his lines just as an experienced film editor would construct a typical film sequence.”Footnote 33 In order to enable the acoustic reenactment through visual representation, Rozhkov followed Maiakovskii while dividing the poem into specific segments or episodes, or so-called sense-units. Following Brian McHale, I suggest naming this division of the stepladder lines into sense-units segmentivity and sequencing, which is an important criterion that defines Maiakovskii's poetry as much as poetry in general.Footnote 34 It is sequencing that facilitated Rozhkov in creating his photomontage series as a cinematic dispositive, entailing two important components—topical (expressed by a set of subjects, objects, and their arrangements) and dynamic (expressed by a series of narrative programs)—that I will discuss later.

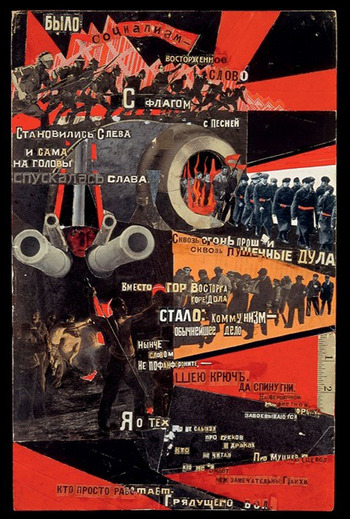

Cinema influenced both Maiakovskii's writing and Rozhkov's reading of poetry.Footnote 35 It is as if he read poetry as segmented writing—the kind of writing that is articulated in sequenced, gapped lines, whose meanings are created by bounded sense-units, operating in relation to pause or silence. It is the phenomenon of sequencing that enabled Rozhkov to represent Maiakovskii's poem visually: to roll the sense-units from lines of printed verses back into the scenes.Footnote 36 Rozhkov did not do this mechanically; instead he rather meticulously divided the poem into segments that naturally follow its progression. Moreover, Rozhkov represented the scenes in a relatively free manner, either framing them in panels with different shapes (triangular wedge-like, trapezoids, speaker-like cones, rectangular) and varied inner dynamics, or leaving them unframed and thus allowing a more animate and symbiotic interaction between the panels.Footnote 37 If we look, for example, at the first sheet of Rozhkov's photomontages with Maiakovskii's verses (Figure 2), we see that he visually segmented the opening lines of the poem (the prologue) into the following five sense-units:

segment I: Army advances from the left

Было: Socialism—

социализм— was:

восторженное слово! an exalted word!

С флагом, With banner,

с песней and song

становились слева, we fell in on the left,

segment II: A face between the muzzles of cannons

и сама and glory itself

на головы came down

спускалась слава. on our heads.

segment III: Soldiers march from left to right

Сквозь огонь прошли, We went through the muzzles of cannons

сквозь пушечные дула. through the bullets’ hail.

segment IV: Common people walk from right to left

Вместо гор восторга— Instead of mountains of elation—

горе дола. The sorrow of the vale.

Стало: Then came:

коммунизм— Communism—

обычнейшее дело. The most ordinary thing.

segment V: A group of shirtless blast furnace workers

Нынче Now

Словом with words so fine

не пофанфароните— you cannot make fanfaronade—

шею крючь no matter how you bend your back

да спину гни. and twist your neck.

На вершочном It's on an unseen

незаметном фронте tiny front line

завоевываются дни. that are won the victories of our days.

Я о тех, I am talking about those,

кто не слыхал who have never heard

про греков of the Greeks

в драках, in their battles,

кто who

не читал have not read

про Муциев Сцево̀л, about Mucius Sceavolas

кто не знает, who do not know

чем замечательны Гракхи,— why the Gracchi brothers are renowned—

кто просто работает— who simply work—

грядущего вол. The oxen of the future.

Figure 2. Yuri Rozhkov: To the Workers of Kursk (1924), photomontage No. 1. Collection of the State Literary Museum (GLM), Moscow. Courtesy of Kira Mattisen.

In the very first sense-unit, Rozhkov emphasized the subject, “we,” by the visual representation of Red Army soldiers, who “fell in on the left” as the forces fighting for the progressive leftist ideas of the socialist Revolution. Rozhkov wittily chose to put the “exalted word”—socialism—on the red “banner,” thus combining the different denotative layers of Maiakovskii's verses and underlying the significance of the very idea of “socialism.”

In the second segment, however, Rozhkov faced a complicated task: to represent visually the abstract concept of “glory.” Yet, his choice reveals the hand of an artist. Namely, he switched the number of nouns in Maiakovskii's lines: the singular abstract noun “glory” is transposed into the visual sign of “the muzzles of cannons” in plural, while the plural subject, “[our] heads,” which at the same time is bestowed with “glory itself,” is represented by a singular red-tinted face. In this way Rozhkov implies that the force of the revolutionary idea is in its cohesiveness, its ability to unite its subjects, thus forging a unified, collective identity. Moreover, the muzzles of cannons stand for the means by which revolutionaries gained glory, while simultaneously providing the shape of a halo, the saint's nimbus.

The third and fourth segments are closely interrelated in Rozhkov's visual representation. Both trapezoid-shaped panels frame the illustration of movement: a tidy formation of soldiers marching from left to right juxtaposed with an unsteady procession of citizens carrying goods and belongings. Here Rozhkov contrasts not only the directions of these two movements, but also the participants’ different appearances and genders, their postures and, consequently, the speed of their respective processions. Rozhkov understood what contemporary graphic novelists know well: the speed of movement appears faster from left to right than from right to left.Footnote 38 This visual contrast between the two panels manifests the spread of sorrowful disappointment with NEP measures that was characteristic for the members of left forces gathered around Lef and concomitant with the ebbing of spectacular revolutionary heroism: “Instead of mountains of elation—/ the sorrow of the vale.”Footnote 39

Rozhkov represents the fifth sense-unit through a single scene, although it is the part of the poem that is significantly longer than the rest. The scene features a group of blast furnace workers in front of the smelting furnace. Two shirtless laborers, joined by two dressed workers, are toiling in the background, bending their backs and twisting their necks. In the foreground we distinguish another bare-chested man in the pose of the victorious warrior who wields a long, thin stick resembling a spear.Footnote 40 Rozhkov represents the shirtless workers as simultaneously laboring and victorious. Also, the very site—a dark environment with fire, heat, and smoke from the blast furnace, comingling with the men's sweat—alludes to “an unseen tiny front line” where the efforts of the workers stand for human struggle for a better, communist future. Thus, the blast furnace site symbolizes the everyday battlefield on which, as the poet suggests, “the victories of our days” are won.

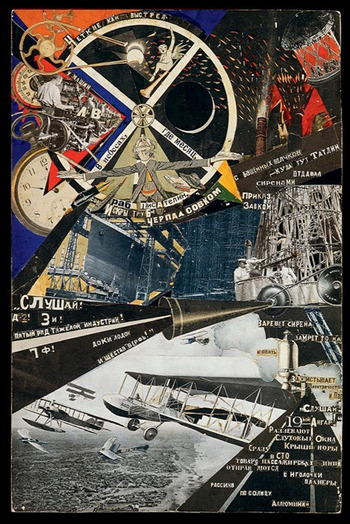

As we see, the sequencing/segmentivity clearly indicate the separate scenes, simultaneously revealing the beginning and end of the syntagmatic segments of verse lines to which a specific visual scene corresponds. Moreover, the sequencing/segmentivity also illuminate relations between assorted representations within the scenes, directing the viewer to recognize various visual rhymes, visual overlappings, or repetitions (analogous to alliteration or assonance in verse). The sequencing/segmentivity point toward how space relations, or the proper dimensionality of the visual (measures of height, width, and depth) and its content (color and shape) correspond to the time relations, the dimensional form of the acoustical (measures of beats in meter, rhythm, and tempo), and its content (tone, timbre, and pitch). Let us look, for example, at one of the three photomontages featuring part of Maiakovskii’ s poem marked with the margin title “IT WAS” and providing the imagery of the economic, industrial, and technical backwardness in which post-revolutionary Russia found itself after the end of the Civil War:

segment I: Dozens of triangles

Шторы We've put

Пиджаками blinds

на́ плечи надели. on our backs for jackets.

segment II: A sinewy youngster cornered by bayonets

Жабой Like angina

сжало грудь the blockade's yoke

блокады иго. has strangled our chest.

segment III: Ruined machinery

Изнутри Inside,

разрух стоградусовый жар. the hundred-degree heat of ruins.

Машиньё The (beast-like) machinery

сдыхало, has gone dead

рычажком подрыгав. with a twitch of levers.

segment IV: Threatening fang-like shards and factory buildings

В склепах-фабриках In the vaults of factories

железо rust

жрала ржа. gobbled up the iron.

segment V: Panoramic landscape scene

Непроезженные Impassable steppe-lands,

выли степи, whined,

и Урал and the impenetrable

орал Ural forests

непроходимолесый. howled.

Figure 3. Yuri Rozkov: To the Workers of Kursk (1924), photomontage No. 3. Collection of the State Literary Museum (GLM), Moscow. Courtesy of Kira Mattisen.

Beside the imagery that clearly suggests the complete ruin of Russian industry and the empty, rusting factories (segments III and IV), Rozhkov employs new symbols of the nascent revolutionary state: the hammer and sickle seal, and the red flag (segment II).Footnote 41 The entire photomontage is Rozhkov's illustration of the poet's commentary on the political situation in Russia during the Civil War until its end in 1922. Maiakovskii's verse in the second segment, for example, refers to the period after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, during which Bolshevik Russia was faced with an international blockade, while simultaneously fighting the White Guards and allied forces. Rozhkov's representation features a sinewy youngster as Bolshevik Russia, who holds the recognizable symbols of the new revolutionary state (flag and blazon) and who is threateningly surrounded by bayonet-like arrows. Since these emblems are absent from Maiakovskii's poem, they represent a clear political supplement to its content. Rozhkov's visual interpretation of Maiakovskii's verses—the narrative program of his cinematic dispositive—renders them more accessible and visible as ideologically unambiguous. The image of the toad is yet another instance where Rozhkov uses literal representations of Maiakovskii's poetic image of the “blockade's yoke” which “strangled” Russia “like angina.”Footnote 42

It is more interesting, however, to see how Rozhkov created a close link between the two different poetic images with apparently distant meanings. The visual representations of segments II and IV, for example, are both framed by circular panels. Also, the pictorial elements of similar shape and color are located inside both circles: the black bayonet-like arrows and the black threatening fang-like shards. The shards are the graphic representation of the “rust” that “gobbled up the iron” in the factories. Maiakovskii's images of the “blockade” and “rust” both brim with alliteration: жабой сжало г р удь and железо ж р ала р жа. While Maiakovskii created semantic links between the remote poetic images of the “rust” and the “blockade” by employing acoustic repetitions (alliterations of the rolling р and repetitive ж sounds), Rozhkov generated such associations by repeating the same visual shapes (circles and sharp black arrows). The backwardness and the accompanied luck of industrial means for production are in large part—as the acoustically and visually established semantic relations indicate—the consequence of the destruction caused by the Civil War, international military intervention, and blockade.

Finally, the sequencing/segmentivity introduces a breaking device: it determines where gaps open up in a poetic text as a provocation to meaning making. It is where spacing interrupts intelligibility, where the text breaks off and a gap (if only an infinitesimal one) opens up. The reader must create the closure: the reader's cognitive apparatus must gear up to overcome the resistance, bridge the gap and close the breech.Footnote 43 The role of sequencing/segmentivity in comprehension is like that of a direction sign: what the lesenka is to meter, sequencing is to reading/viewing protocol.

Production: The Industrial Land of the Future

Maiakovskii's ode to the working class and Rozhkov's subsequent visual illustrations both celebrated the cult of the machine, the struggle for time, and allied currents of efficiency. In that regard, they functioned not only as purposeful political propaganda, but also as an artistic statement on the importance of technology, organization, and discipline. Similarly to Alexei Gastev and Platon Kerzhentsev, who were true promoters of the new technological age in the nascent Soviet Russia, Maiakovskii and Rozhkov articulated a vision of the communist future commensurate with the desire for technical and industrial modernity.Footnote 44

Their optimal projection into the future was made upon the American mass production assembly line as giant emblems of modernity. As the precise indicator of the country of origin of the technological machinery from the cover page, Americanization was also a metaphor for fast industrial tempo, high growth, productivity, and efficiency. Such a vision of the future, first and foremost, involved the visual imagery of a time obsessed with modern technology. Rozhkov's first four photomontage sheets addressing the section of Maiakovskii's poem entitled “IT WILL BE” surge with imagery of large cranes, construction sites, spacious wharfs, building yards, heated blast furnaces, iron-constructed bridges, factory halls, high boat masts, and factory chimneys.

More importantly, such a vision of the future entailed new means of transportation and communication, which epitomized the dynamism of modern everyday life and the rapid pace of industrial development. The factory sirens and cone-shaped loudspeakers were, as part of an aural-centered vision, pervasive icons of modern means of communication. We see, for example, the same loudspeakers in many of Gustav Klutsis's graphic designs of the propaganda stands and so-called Radio Orators. Both speakers and sirens were used primarily in organizing and mobilizing the workers in factories, which was reflected through two main artistic forms during the post-revolutionary years: the symphony of factory sirens and the noise orchestra.Footnote 45 Simultaneously, the various means of passenger and industrial cargo transportation—train, car, tractor, boat, airplane—were the most suitable images for the visualization of the bright Soviet future and, as we will see, of a “running memorial” to the working class. An American automobile and the Taylorized worker were the totems of progress in the 1920s.Footnote 46

Figure 4. Yuri Rozhkov: To the Workers of Kursk (1924), photomontage No. 11. Collection of the State Literary Museum (GLM), Moscow. Courtesy of Kira Mattisen.

It is no coincidence that Rozhkov's most visually compelling photomontage is the one representing “cars and engines” as they “pass in streams through the main gates of factories,” and “ships for surface and under-water voyages” as they “slip into the water from wharfs a mile long” (Figure 4). Rozhkov's vision portrays the prospective future as inseparable from the factory and its production assembly line. This photomontage sheet notably stands out with its distinct completeness, compositional sternness, and harmony of design, which altogether faithfully reproduce the features of the assembly line: precision, continuity, coordination, speed, automatization, and standardization. Rozhkov artistically soldered segregated elements within the image, thus achieving an organic visual whole. The colorful stripes in the background create a feeling of spatial depth and movement. A spare amount of text is introduced in the montage so that Maiakovskii's verses are sharply defined and easy to read.

Rozhkov skillfully employs a photograph of steel construction in order to represent visually Maiakovskii's poetic personification of the factories whose “main gates / gape open wide.” The architecture of the steel construction (represented at the upper part of the photomontage) is reminiscent of the arcades because of its verticality, which concludes in the soothing curve of the arc. Here Rozhkov succeeds in taming the spiky angularity, which is a pervasive characteristic of his constructivist graphic design, and to transform it into the curves of the steel arch and the dotted Dunlop tire. Nevertheless, Rozhkov preserves the sharpness and dynamism of such angularity in the graphic representation of the linear perspective, the vanishing point of which is the tiny black square far back in the entrance of one of the “main gates” of the factory (Figure 4). Many yellow, blue, and red stripes radiate out of this tiny black square, thus creating the effect of spatial depth and movement. Even the typographical layout of the verses in the photomontage's upper part enhances linear perspective by suggesting perception of spatial motion.Footnote 47

Rozhkov uses multicolored beaming stripes to graphically emphasize the important concept of lenta from Maiakovskii's image of the “cars and locomotive engines” that “pass in streams” or, more precisely, that “pass by stretching on strips,” or “on long belts,” since the Russian word lenta translates into all these meanings (stream, strip, beam, band, belt). The entire photomontage distinguishes itself by this new standard of beauty—the beauty of the industrial and technological world of construction and creativity. The vision of such a technological land of the future is modeled upon Ford's conveyor belt, which functioned as a model both of a factory and of modern society.

Another alluring example of the conveyor belt image is the cut-and-paste photograph of men operating a series of machines, each of which has a wheel connected to a single rotating mechanism (Figure 5). This image—surrounded by a larger image of a round pocket watch, an image of a cyclic barometer, and an image of a rotating flywheel with a belt—occupies the left quarter of the ring with the thick white outline, in the center of which appears yet another round gear. Rozhkov uses this image to represent visually the following lines from Maiakovskii: “Precise like gunshot / at the machine / are time and motion men.” Yet he pastes the letters of the word “Elvists” over the image that represents skilled workers operating the machines. Through his typographic choice of the more visible, majuscule Cyrillic letters л and в in the word эЛьВисты, Rozhkov emphasizes the initials from which the word originates, thus making Maiakovskii's hard-to-read reference visually readable: Эльвисты, or “time and motion men,” is what the members of the League of Time were called, and “ЛВ” (Лига Время) was its abbreviation, created for the propaganda purposes for the Scientific Organization of Labor in the Soviet Union.Footnote 48

Figure 5. Yuri Rozhkov: To the Workers of Kursk (1924), photomontage No. 10. Collection of the State Literary Museum (GLM), Moscow. Courtesy of Kira Mattisen.

Maiakovskii was also familiar with Kerzhentsev's concern to introduce scientific principles into all organized activity of work (the army, education, and all aspects of social life). Kerzhentsev's vision of the revolution in time, or revolution from below, was built in the foundations of his major works, The Struggle for Time and The Scientific Organization of Labor. Maiakovskii was most likely familiar with Kerzhentsev's theoretical work on the subject and his impassioned article “Time Builds Airplanes,” published in Pravda around the time he founded League of Time (Figure 5).Footnote 49

Representation: Political Commentary and Cultural Critique

The use of the photographic documentary material for cultural critique and satirical commentary puts Rozhkov in close proximity to the tradition of the Dadaists and Rodchenko's early photomontages. But the force of the ideological doctrine and agitation propaganda which one recognizes in Rozhkov's cinematic dispositive is certainly what brings his work closer to the graphic works of Klutsis, Valentina Kulagina, Sergei Sen'kin, Solomon Telingater, and the brothers Stenberg.

The photomontages of Raoul Hausmann, Hannah Höch, Richard Huelsenbeck, George Grosz, John Heartfield and other Berlin Dada monteurs featured the images of important politicians and other contemporary figures popularized by the illustrated press and mass media. In the 1923 edition of About This, Rodchenko was the first to incorporate actual photographs of the people described in that particular work of fiction: poet Vladimir Maiakovskii and his lover Lili Brik.Footnote 50 Rozhkov, in turn, treats Rodchenko's photomontage as raw material for his own work and uses the image of Maiakovskii from About This to represent the following verses from “To the Workers of Kursk”: “A word factory / has been given me to run” (Figure 6). Following Sergei Tret'iakov's proposal, Maiakovskii represents himself as a word factory manager and production organizer.Footnote 51 Rozhkov's representation, similar to the Berlin Dadaists, suggests instead the poet-cyborg who is in symbiosis with the machine.Footnote 52 Thus, Rozhkov's photomontage renders the audible material of production visible: the cone-shaped cylinder of a phonograph radiates the words and phrases that are, in fact, the titles of all of Maiakovskii's major works up to “To the Workers of Kursk.”Footnote 53 Rozhkov may have found the model for this visual rendering in Klutsis’ photomontage “Downtrodden Masses of the World: Under the Banner of the Comintern, Overthrow Imperialism,” made for the photo-book Young Guard: For Lenin (Molodaia gvardiia. Leninu, 1924).

Figure 6. Yuri Rozhkov: To the Workers of Kursk (1924), photomontage No. 5. Collection of the State Literary Museum (GLM), Moscow. Courtesy of Kira Mattisen.

Following in the footsteps of the Berlin Dadaists and the early Soviet satirical periodical Krysodav, Rozhkov incorporated the images of important European and Russian politicians of the time.Footnote 54 Thus, for example, for the illustration of the lines, “It fled from the Germans / it feared the French / With their eyes / fixed on / this tasty prize,” Rozhkov uses the images of Joseph Joffre, a French general during World War I, and Raymond Poincare, a French statesman who served five times as prime minister and once as president (1913–20). While the images of these Frenchmen symbolize France—along with its most stereotypical symbols such as Paris, the French flag, Eiffel Tower, and a bottle of (supposedly French) wine—they are also here to remind the reader/viewer of the French military engagement against the Bolsheviks in the Polish-Soviet war during 1919–21.

The photomontage on the subsequent sheet shares a similar function that—along with Maiakovskii's lines— “You, / who yelled: / “You've eaten the / sunflower seed bare, / Sunflower / has littered / Russia!”—features images of Tsar Nikolas II and several members of the Russian Provisional Government. These members include, from left to right, Boris Savinkov, the deputy war minister in the Provisional Government; Pavel Milyukov, the founder, leader, and the most prominent member of the Constitutional Democratic Party (Kadets), and Minister of Foreign Affairs in the Provisional Government; Alexander Kerensky, the second prime minister of the Russian Provisional Government; and Alexander Konovalov, one of Russia's biggest textile manufacturers and minister of trade and industry in the Provisional Government.Footnote 55

Below one can see the face of Tsar Nicholas II (executed by the Bolsheviks), under which the words “to Paris” in French suggest that the majority of members of the former Provisional Government ended up in exile in France. Maiakovskii refrains from directly referring to these political figures; he actually calls out some “Alfred from Izvestia,” which is the pseudonym of the publicist Kapel'ush who published an article against the journal Lef (on June 10, 1923) in the daily newspaper Izvestia. Rozhkov, however, chooses not to represent “Alfred from Izvestia”; instead, he uses the opportunity to accuse the Russian emperor and his political successors as being the main culprits of Russia's pre- and post-revolutionary hardships.

Maiakovskii's anti-monumental attitude becomes one of the main ideological statements providing the poem's polemical perspective.Footnote 56 Along with canonical nineteenth-century Russian writers, who were decisively “thrown from the Steamship of Modernity” by the Futurists a decade earlier, Maiakovskii straightforwardly calls out many of his contemporaries. He polemicizes with those who openly wrote against Lef and their avant-garde art as alien to the masses, and with those who participated in the contemporary processes of commemoration supporting less progressive, traditional values. In the last three photomontages, Rozhkov demonstrates Maiakovskii's anti-monumental attitude, including images of well-known (both pre- and post-revolutionary) cultural figures.

Figure 7. Yuri Rozhkov: To the Workers of Kursk (1924), photomontage No. 13. Collection of the State Literary Museum (GLM), Moscow. Courtesy of Kira Mattisen.

Rozhkov illustrates the first segment of the sheet with the image of his supervisor from the Lenin agit-train—Lev Sosnovskii (Figure 7).Footnote 57 We see Sosnovskii writing “Down with Maiakovskiiism” (Долой Маяковщину) in cursive letters—a clear illustration of the former's confrontational cultural politics expressed in the articles and feuilletons, published from 1920 to 1923 in Pravda. It is very likely that Rozhkov was familiar with the response to Sosnovskii in the third issue of Lef journal's editorial, entitled “LEF to Battle!” There one finds the following statement: “Кто в Леф, кто по дрова.”Footnote 58 The word дрова (firewood) is footnoted with the following sentence: “Oak, pine, aspen, and other Species.” In Russian, these words (oak=дубовые, pine=сосновые, aspen=осиновые, and other Species=и других Родов) create sound associations with the names V. Dubovskoi, L. Sosnovskii, S. Rodov and Others (such as, for example, the aforementioned Alfred from Izvestia and V. Lebedev-Polianski from Pod znamenem Marksizma), who constantly attacked Lef and Maiakovskii in particular. This witty editorial of the third issue of Lef (June-July 1923) is followed by the “Program” section, which is entirely devoted to the task of debunking Sosnovskii's accusations as unfounded, counter-factual, and demagogic.Footnote 59

In this photomontage sheet, Rozhkov uses yet another image of Maiakovskii from Rodchenko's photomontage for About This (Figure 7). The image of Maiakovskii posed as an old man is juxtaposed with the portraits of Dostoevskii and Leo Tolstoi, and the images of monuments to Pushkin and Gogol'. This segment foreshadows Rozhkov's subsequent illustrations, and visually underlines Maiakovskii's resistance to the processes of ossification, monumentalization, and canonization about which Iurii Tynianov wrote so deftly in his 1924 article “Interval.”Footnote 60 The photograph of geologist P.P. Lazarev, a leading member of the committee for research and exploration of KMA appointed by Lenin, which shows him holding a rock in his hand, juxtaposed with the image of workers—“thirty thousand or so / Kursk / women and men”—dominates the photomontage (Figure 7).

The top segment of the next photomontage sheet is additionally intriguing, since it represents Rozhkov's supplement to Maiakovskii's verses (Figure 8). While the poet mentions Merkulov (whom he misnames) and three Andreevs, Rozhkov pastes three images of Leonid Andreev.Footnote 61 Rozhkov, however, decided to provide his own creative response on another topic: Maiakovskii's poetic image of “the whole academy crowd, / messing about / with writers’ moustaches.”

Figure 8. Yuri Rozhkov: To the Workers of Kursk (1924), photomontage No. 14. Collection of the State Literary Museum (GLM), Moscow. Courtesy of Kira Mattisen.

Rozhkov made a sidesplitting representation of the nineteenth-century Russian writers’ pantheon, assembling the following Frankenstein-like hybrid identities by cutting and pasting the halves of the faces (from left to right): I.S. Turg/oncharov, from Ivan Turgenev and Ivan Goncharov; A. Herz/zhkovskii, from Aleksandr Herzen and Dmitrii Merezhkovskii; Tols/trovskii, from Aleksei Tolstoi and Aleksandr Ostrovskii; N.V. Gog/resaev, from Nikolai Gogol' and Vikentii Veresaev; Tolst/chenko, from Lev Tolstoi and Taras Shevchenko; Maksim Gor'k/ushkin, from Maksim Gor'ki and Aleksandr Pushkin; and Tolst/vratskii, from Lev Tolstoi and Nikolai Zlatovratskii, (Figure 8). Rozhkov may have found the model for his visual joke in Hannah Höch's 1923 photomontage Hochfinanz, or in Rodchenko's front cover for the Mess Mend (“A Yankee in Petrograd,” Vol. 7, Black Hand by Jim Dollar, 1924). Rozhkov's photomontage work on Maiakovskii's 1927 poem “Jew” proves his preference for this stylistic device.Footnote 62

Rozhkov's entertaining and mocking supplement to Maiakovskii's poem reflects the existent anti-canonical sentiment that Lef members preached, practiced, and disseminated, first and foremost in their manifestoes. For example, in the programmatic text “Whom Does LEF Wrangle With?” from the first issue of Lef, one can read the following attack on the classics: “The classics were nationalized. The classics were honored as our only pulp literature. The classics were considered permanent, absolute art. The classics with the bronze of their monuments and the tradition of their schools suffocated everything new. Now, for 150,000,000 people the classic is an ordinary textbook. … we will fight against transferring the working methods of the dead into today's art.”Footnote 63 In the text “From Where to Where?” Sergei Tret'iakov writes in a similar vein: “Never encumber the flight of creativity with a fossilized stratum (no matter how highly expected)—this is our second slogan.”Footnote 64 Rozhkov's photomontage draws upon this very connection between the classics, on the one hand, and the fossilizing forces of tradition and monuments, on the other.

At the same time, the writers’ pantheon photomontage casts an additional light on the following verses, in which Maiakovskii assures that no one will call out the factories to “go back / again / to ivory, / to the mammoth, / to Ostrovskii.” For the illustration of this part of the poem, Rozhkov employs angular shapes—triangles and pyramid-like spikes—along with an image of hands turning a wheel (probably backwards). Behind these hands is the portrait of the nineteenth-century Russian playwright, Aleksandr Ostrovskii (Figure 8). Triangles and spikes emerge again as the visual symbol of obstacle(s).Footnote 65 In this case, the obstacle is scripted in the quote, “Back to Ostrovskii!” This was a new slogan proclaimed by the Soviet Commissar of Enlightenment, Anatolii Lunacharskii, who in anticipation of the one-hundredth anniversary of the playwright's birth published a two-part article in Izvestia (April 11 and 12, 1923), entitled “About Aleksandr Nikolaevich Ostrovskii and Concerning Him.” In the article, Lunacharskii called on revolutionary theater artists to revise their negative attitude toward the classics. Moreover, he issued a call for the reevaluation of Russian literary classics within the new sociopolitical context, along with the controversial proclamation that futuristic art—which rejects the old art together with academism—cultivated an erroneous method of reassessment.Footnote 66 Lunacharskii's article triggered a sound debate between “monumentalists” and “iconoclasts” and an avalanche of responses, among which Maiakovskii's and Rozhkov's are the most playful and inventive.Footnote 67

Maiakovskii's lines, “At your / hundredth anniversary / the likes of Sakulin / won't pour out / unctuous speeches” are undoubtedly a response to Lunacharskii's article. They are also an expression of resistance to the public recognitions of prerevolutionary artists and cultural workers, however, such as Leonid Sobinov (an acclaimed Imperial Russian operatic tenor) and actor Aleksandr Yuzhin, (the Georgian Prince Sumbatov, who dominated the Maly Theatre in Moscow at the turn of nineteenth and twentieth centuries). Both Yuzhin and Sobinov were made People's Artists of the RSFSR in 1922 and 1923, respectively. Maiakovskii was most likely provoked by such an act, which he understood similarly to Lunacharskii's new slogan “Back to Ostrovskii”—as a relapse toward more traditional and bourgeois art forms. Moreover, on the cover of the second issue of Lef (April-May 1923), one can find Rodchenko's photomontage with a crisscross expressing an avant-garde gesture of rejecting and canceling the old, bourgeois art, of which one of the symbols is Prince Sumbatov himself.Footnote 68 Following Maiakovskii, Rozhkov's photomontage incorporated images of “monographs” and marble fences, above which are two portraits of Sobinov as well as the image of a stone profile in which one can recognize a monument to Shakespeare (Figure 8).

An Avant-garde Memorial to the Proletariat

The entirety of Maiakovskii's poem deals with the issue of how to pay tribute to the tens of thousands of workers, to the anonymous mass of men and women “who simply work,” and whom Maiakovskii baptizes “the oxen of the future.” Maiakovskii considered the poem a suitable mode for commemorating the working class and expressing its revolutionary role, especially because the verses could easily be adapted into publically spoken words or innovative photo-books. He knew that his modern ode devoted to the workers could be read at public meetings or even recorded and broadcast to tens of millions. In other words, he was aware of how the new technological media were able to bestow impermanence with permanent qualities. At the time, Maiakovskii believed in what he was preaching and kept insisting that men must not lose sight of the grand social design, through which each man alone could hope for what all men desired. He insisted not only that communal effort and faith in one's country must not be relaxed, but also that such endeavors and convictions must be reproduced regularly as a part of the culture of everyday life by and through the means of technical reproducibility.Footnote 69

Toward the very end of the poem we find an expression of the poet's belief in the promise of technological advancements. Maiakovskii envisages “a temporary monument” to the working class as the “running / high-speed / handmade memorial.” Conceptually, the image of “running memorial” still strikes one as a contradictory and puzzling, if not an innovative idea. One can easily find such concepts of the moving monument in the Russian literary tradition, starting with the representation of the living statue in Pushkin's poetic mythology.Footnote 70 Yet Maiakovskii's contribution to the image—nestled in the cultural tradition of Russian imagery so cozily that it almost became customary—was his ascription of a high-speed quality to it.Footnote 71

Rozhkov's visual representation of the memorial to the working class is consistent with Maiakovskii's poetic image and reflects the constructivist insistence on the use of technology and the importance of functionalism in art. For the visual representation of such a monument, Rozhkov chose the image of a locomotive (Figure 8). Although an invention of the early nineteenth century, the locomotive still summons a set of meanings tightly connected with progress and rapid movement, so significant for the Russian revolutionary imagination in the early 1920s. This connection is, of course, completely literal: the locomotive (lat. “causing motion”) provides the motive power of a train and pulls the train compartments from the front. However, its link to classic and avant-garde conceptions of art is implicit: the locomotive has no payload capacity of its own, and its sole purpose is to move the train along the tracks. As an autonomous aesthetic object, the locomotive supports Immanuel Kant's notion of the “purposeless purpose” of an art object. Just as any other machine, the locomotive possesses an expressive visual beauty and “stupendous power.”Footnote 72 On the other hand, as a highly functional vehicle for the particular means of transport, the locomotive completely embodies the constructivist concept of the artwork as a product of politically effective, socially useful, and mass-produced art. Following Maiakovskii's conception of the “running memorial,” Rozhkov's visual representation is on par with the constructivist art governed by the principles of material integrity, functional expediency, and societal purpose.Footnote 73

Ultimately, the image of locomotive operates as a symbol capturing the dynamic nature of Rozhkov's cinematic dispositive that itself functions as a “running, hand-made” de-mountable memorial to the working class. The acoustic crescendo from the finale of Maiakovskii's poem resonates in the visual cadence of Rozhkov's photomontage. Maiakovskii refuses the “sharp-tongued lecturer” who would “heap praises” on the working class during the “anniversary in the interval of the operas or operettas.” Instead, Maiakovskii asserts, the “tractor will sound forth” as “the most convincing electro-lecturer,” and “a million of chimneys / will inscribe / your last names.” Rozhkov employs the images of factory buildings and chimneys, tractors (“engines on wheels”), motors, and dynamos, thus emphasizing the importance of the increase of technologically advanced and organized production. Each of the sense-unit panels of Rozhkov's last photomontage has a similar rectangular shape. This feature of compositional equivalence functions similarly to cadence in versification: it represents visual configuration that creates a sense of repose, finality, and resolution.

The very last image of the large mining tube/pipe and the workers in and around it is reminiscent of the image of Red Army soldiers going through “the muzzles of cannons” from the prologue sheet. Stylistically, this visual rhyme of the imagery from the beginning and the end of Rozhkov's dispositive has a formulaic function: similar to the initial and final formulae from the folk genres, it provides the photopoem with the so-called “ring structure.”Footnote 74 Pragmatically, Rozhkov's sequential, cinematic rendering of such imagery, similar to temporality in the socialist realist novel, aspires to bridge the gap between the world as it “is” and as it “ought to be” by subordinating historical reality to the preexisting functional patterns of folk literature.Footnote 75 Semantically, however, it illustrates the assertion made by historian Sheila Fitzpatrick that the first Five-Year Plan, introduced in 1928 after the end of NEP, mobilized both the visual and discursive rhetoric of War Communism, thus delineating transition towards the new dispositif of the late 1920s: socialist realism.Footnote 76

Maiakovskii's utopian vision and Rozhkov's subsequent cinematic rendering of the “half-open eye of the future” are both agitprop apparatus dispositives, whose main function amounted not to propaganda, but to the production of reality through aesthetization. While Arvatov's “agit-cinema” recognized the “possibilities” that the agitational representation grants (“to take the existent and do with it whatever one wants”), Rozhkov's cine-dispositive introduced distinct devices and visual vernacular that played a critical role during the late 1920s in turning the heroic work, amazing feats, and bold intentions into “facts before they become reality.”Footnote 77 Rozhkov's cine-dispositive commemorated the workers by celebrating the image of a massive industrialization campaign, which in the late 1920s led to a complete restructuring of the Soviet arts.Footnote 78 As such, it signposted the subsequent conversion of avant-garde artists’ multiple narrative programs into the singular program with a “homeodynamic state,” the official “method” of socialist realism.Footnote 79