Introduction

The fundamental opacity of the historical process means we live in what Bloch calls ‘the darkness of the lived moment’ so that we are surrounded both by failure and success, utopia and dystopia, freedom and oppression. (Thompson Reference Thompson2013: 5)

As Kenya drew towards the fiftieth anniversary of its independence, its national media published articles that looked back on the postcolonial record of development and progress. Two of the newspapers with the largest circulation – the Daily Nation and The Standard – took the opportunity to reflect on some of the key events that, journalists argued, were ‘defining moments’ in the history of the nation. The opening of the new provincial hospital in the western town of Kisumu, on 25 October 1969, was one such event (Gekara 2009; Karimi 2013; Amina Reference Amina2012). Built as a gift from the Soviet Union to Kenya, the hospital materialized Cold War solidarities as well as conflicts concerning Kenya's developmental futures. During the 1960s, tensions had been rising between President Kenyatta and his one-time vice-president, Oginga Odinga, driven by ideological divisions over the country's political direction, Odinga's calls for redistribution and his decision to leave government and set up an opposition party in 1966. The pro-Western Kenyatta regarded Odinga as being too close to the USSR and to socialism, and he was suspicious of Odinga's Soviet connections, which the ‘Russian’ hospital materialized. Matters came to a head at the opening ceremony. Odinga's supporters heckled Kenyatta and stones were thrown. As his entourage sped away from the ensuing chaos, Kenyatta's bodyguard opened fire on the crowds gathered on the streets. Between eight and thirty people died and many more were injured (see Branch Reference Branch2011: 52–65, 87–8). The new hospital's wards were overwhelmed by the wounded while the new mortuary received the dead.Footnote 1 Three days later, Odinga was placed in detention and his party was banned. The incident was Kenyatta's last visit to Kisumu during his increasingly authoritarian rule (1963–78). In Kisumu and its hinterlands, 1969 was followed by years of marginalization from politics and a deeply felt exclusion from development and the fruits of Kenya's economic growth.

Fifty years later, newspapers, journalists and bloggers returned to this incident (Gekara 2009; Amina Reference Amina2012; Karimi 2013).Footnote 2 A YouTube screening of President Kenyatta's speech at the hospital's opening ceremony received lively comment.Footnote 3 In October 2013, The Standard interviewed a witness to the 1969 massacre who recalled ‘people felled by the bullets’ and schoolchildren being trampled in a stampede as the crowds fled the gunfire (Karimi 2013). In an article titled ‘Incident that turned Kenya into a one-party state’, the Daily Nation published a photograph of schoolchildren running from the violence (Gekara 2009). Journalist Emeka-Mayaka Gekara argued that the event marked a turning point in the new nation towards the oppression of political opposition and the consolidation of state violence, a turn that was taken to greater extremes during the rule of President Moi (1978–2002), Kenyatta's successor.

The newspaper articles recalling the hospital's opening ceremony mark a retrospective moment, calling Kenyans to reflect on fifty years of ‘progress’, on past and present relations between the state and its citizens, on development and its beneficiaries. The media attention also marks a rare moment of reflection on the hospital's past and its role in Kenya's Cold War politics and political struggles. The newspaper story caught my attention because, while conducting ethnographic and archival research in the hospital, still known locally by its nickname, ‘Russia’, I had been struck by the lack of interest in its past. The memory of the Soviet gift to Kenya, and the part the hospital played in visions of developmental futures and Cold War politics, seemed to remain only in its nickname. Certainly, the act of calling the hospital ‘Russia’ recalls Odinga's legacy and the alternative visions of development and of uhuru that he attempted to pursue. Yet calling the hospital ‘Russia’ does not appear to be an act of remembering its origins, the excitement that permeated its beginnings as a gift from the Soviet Union, or its ambivalent symbolic role in Soviet friendship and Cold War politics. The past's presence in the solid, tropical modernist architecture of the building and in the nearby modernist housing estate named ‘Moscow’ did not appear to be of great interest to the hospital staff or to residents of Kisumu in general. In particular, the conflicting visions of development, visible in the moment of the hospital's birth and in the commemorative attention given to it in the media fifty years later, are invisible elsewhere, submerged, seemingly forgotten.

The tension between commemoration and amnesia raises questions concerning how pasts are inhabited and about the afterlives, if there are any, of the dreams, hopes and expectations of past futures that once animated Russia in Kenya. The simplest question I ask – how this hospital, Russia, is connected to the past of its foundation – has no simple answer, as the remains of these connections appear truncated, erased or deflected. The violence of Russia's birth reveals the extent to which aspirations concerning development were riven by ideological conflict. The newspaper articles underline that Russia's past is deeply political, while the amnesia surrounding this past suggests a depoliticizing impulse. What, then, is at stake in this depoliticization? The question is more than one of remains; it is about the presence and absence of the past and the tying and untying of pasts to the present.

My starting point in this article is the present absence of these developmental pasts and the dreams that surrounded them. Anthropologists, historians and cultural geographers have recently turned to the remains, ruins and ruinations of mid-twentieth-century projects of development, industrialization, modernization and science, and the past futures they embodied, attending to the traces of the past in the present, the multiple temporalities embedded in material remains, and the affective landscapes these traces engender (see, for example, Stoler Reference Stoler2008; Geissler Reference Geissler, Geissler and Molyneux2011; Street Reference Street2012; Lachenal 2013; Tousignant Reference Tousignant2013; Droney Reference Droney2014; Geissler et al. Reference Geissler, Lachenal, Manton and Tousignant2016; Yarrow Reference Yarrow2017). One of the most striking of these affects is nostalgia. As the future has contracted and horizons narrowed, longings for past futures, embodied in the dreams and promises of mid-twentieth-century projects of development and progress, have gained a powerful presence in places as diverse as Zanzibar, Vietnam, England and Cameroon (e.g. Bissell Reference Bissell2005; Piot Reference Piot2010; Schwenkel Reference Schwenkel2013; Ahearne Reference Ahearne2014; De Jong and Quinn Reference De Jong and Quinn2014; Lachenal and Mbodj-Pouye Reference Lachenal and Mbodj-Pouye2014; see also Ferguson Reference Ferguson1999). When I began my fieldwork in ‘Russia’, I had expected the tropical modernist buildings to evoke a sense of nostalgia for the dreams of modernity and progress associated with independence and its promises. I found nothing of this. The absence of interest in Russia's past forced me to think about the politics of making pasts (Edensor Reference Edensor2005). Why are some past dreams of progress remembered and even commemorated, while others are not? Why do some remains become significant while others become ‘rubble’ (Gordillo Reference Gordillo2014)? While it is often argued that remembering is a social and political process, the presence of memory in one form or another is often taken for granted (Edensor Reference Edensor2005). For Gaston Gordillo (Reference Gordillo2014), working in Argentina amidst sites of ancient and recent settlement and extraction, these questions about significance became crucial. He shows that place making is political, as is the work of remembering and forgetting.

The amnesia surrounding Russia calls for our attention. Why do these past futures and the promises and dreams they held out fail to get a foothold in the present? Just as scholars plumb nostalgia for its interpretive possibilities, I suggest that we should attend both to this amnesia and to the past futures that seem to be forgotten. We should do this not to recover a nostalgic view of mid-twentieth-century dreams of progress but rather to acknowledge the struggles that shaped the past and the present (Atieno-Odhiambo Reference Atieno-Odhiambo, Ogot and Ochieng’1995: 2). At the same time, we should acknowledge that what draws us to people's nostalgic narratives of the mid-twentieth century are the hopes and dreams invested in them. At a time when grand narratives of progress have lost their footing, we long for an era when progress seemed universal and there was optimism about the future. Thinking about these pasts, remembering them, recalling and retelling them become ways of imagining other conditions and possibilities: a form of hope in the present. They recover a kind of dreaming that reached ahead and that had a destination and a direction. Today, as Peter Thompson argues in The Privatization of Hope, ‘grand dreams have crumbled along with grand narratives’ and dreaming has been telescoped down to the lowest common denominator (Reference Thompson2013: 14). Instead of imagining a collective destination, ‘dreams of a better world are dreams of a better world for oneself and one's family’ (ibid.: 5). Pragmatically accommodating our hopes to the limitations of present-day horizons, we dream of private happiness and private ambitions. Does the amnesia about Russia's past, with its narratives of progress and its conflicting dreams of development, indicate a loss of the ability to dream (Buck-Morss Reference Buck-Morss2002)? In The Principle of Hope, Ernst Bloch (Reference Bloch1986) maintains that hope has to be learned: it is the product of experience, failure and resistance to an everyday acceptance of reality (Thompson Reference Thompson2013: 7). Hope is not blind optimism; instead, it is ‘the wave and particle that carries us forward’ (ibid.). If, as Lachenal and Mbodj-Pouye (Reference Lachenal and Mbodj-Pouye2014) put it, ‘the history of development is interwoven with subjective experiences of duration, progress, failure, of rupture and continuity’ (and, we could add, expectations and anticipation), what happens to the ‘learning of hope’ when this history is forgotten and cast aside as irrelevant?

This article begins with the story of Russia, to explore some legacies of the Soviet gift and the ways in which these developmental pasts and the dreams that accompanied them are connected to, or disconnected from, the present. Methodologically, I approach these questions through a focus on ‘knots’, connections between past and present, which I encountered and unearthed in the process of my research. These knots include material, institutional, bureaucratic, affective and biographical remains. They range from the architectural statement made by the hospital today, its solid tropical modernist buildings, to archival records, letters and minutes of meetings, and the newspaper articles commemorating the hospital's opening in 1969 (see Geissler and Prince Reference Geissler, Prince, Geissler, Lachenal, Manton and Tousignant2016). Knots are entanglements between past and present that one may also find in language, in place names and in biographical narratives. Moving from questions of memory and forgetting to encounters with these remains and residues in the present (Hunt Reference Hunt1999; Reference Hunt2014; Reference Hunt, Geissler, Lachenal, Manton and Tousignant2016), I find it useful to approach the hospital as a ‘constellation’ – a fraught place that ‘gathers’ ideas, dreams, memories, affects, objects and people – and as a ‘terrain’, as this evokes the texture of a temporally dense and layered place (Gordillo Reference Gordillo2014). In moving across such terrain, one encounters rifts and stumbles into cracks.

The hopeful future

‘Russia’ in 2015. Completed in 1968, the large provincial referral hospital is a concrete three-storey tropical modernist building situated near the centre of Kisumu. Originally 200 beds, it serves as the referral hospital for an entire province and has expanded over the years to more than 500 beds, with the addition of new wards and outpatient buildings. Its striking feature is the solidity and durability of the materials; in contrast to many of the recently constructed buildings in Kenya, there are no cracks in its concrete. After a long period of disrepair and neglect during the 1980s and 1990s, contracted cleaners, gardeners and maintenance staff ensure clean corridors, manicured lawns and newly painted walls (Figures 1 and 2). This is no ruin, then, but a place oriented to the future, manifested in plans for new developments and partnerships with private companies, NGOs and foreign donors (predominantly USAID). The hospital's self-presentation materials highlight this orientation. I could find few references to its past beyond a line about its original construction by the USSR and the official photograph of President Kenyatta at the opening ceremony, in which there is no hint of the violence.Footnote 4

Figure 1 ‘Russia’ viewed from a covered walkway, March 2014.

Figure 2 Stairway to the operating theatres, March 2014.

The absence of this past led me to the archives and to the material concerning the planning and construction of the Russian hospital.Footnote 5 To my surprise, far from dry documentation, these papers were brimming with affect. The trail of letters, reports, requests and minutes of meetings exuded a palpable ‘sense of anticipation, of limitless potential, of national futures’ (Anderson and Pols Reference Anderson and Pols2012: 111), suggesting lively conversations between Kenyan civil servants driven by the expectancy of a newly constituted citizenry. Here, the hospital emerges as an object of hope, the repository of the dreams of a new future that seemed to pour forth from Kenya's independence.

The new Russian hospital was planned as a state-of-the-art hospital that would provide modern medical care in explicit contrast to the racially segregated forms of medical care that had been available to Kenyans in the colony. Discussions about building a new hospital for the Kenyan population began in 1960, before independence. At this time there were two hospitals in Kisumu and they were racially segregated. The Nyanza General Hospital was located in the town centre and was for ‘Africans’; while the ‘Victoria Hospital’ was in the formerly European-only residential area and had been whites-only (Figure 3). Up to independence, these hospitals, both single-storey and built in the British colonial bungalow style, remained infused with colonial hierarchies. Nyanza General Hospital was described as being crowded and inadequately staffed, with poor facilities. The new nation wanted something better. From the early 1960s, the British administration had been promising to build a new, modern hospital but was unwilling to finance it, and by independence in 1963, nothing had happened.Footnote 6

Figure 3 Victoria Hospital, originally the European hospital in Kisumu, now the private ‘amenity ward’ of the Russian hospital, March 2015.

In 1964, a letter records that the Soviets made an offer to build and equip a new, ‘super-modern’, first-class hospital in Kisumu, ‘as a gift from the USSR to the Kenyan people’.Footnote 7 The offer was made in the wake of a visit by a Kenyan delegation to Moscow, led by Oginga Odinga, to ask for economic aid, arms, scholarships and a hospital (Branch Reference Branch2011: 38; Rothmyer Reference Rothmyer2018: 120). Odinga forged ahead with these ‘gifts’ from the USSR in the face of manoeuvres by Kenyatta (and his British and American allies) to cut him off from Soviet ties of patronage (Branch Reference Branch2011: 41). The USSR promised to fully equip the hospital with up-to-date technologies (e.g. X-ray machines) and materials, down to the light bulbs in the operating theatre.Footnote 8 In addition, it promised to supply the hospital with all its medicine for the first two years, and with medical staff (fifteen doctors and ten technical assistants) for the first five years.Footnote 9 Construction began in 1966 and the hospital – referred to as the Russian hospital – was officially opened in 1969.

During this prolonged period, the Provincial Medical Officer (PMO) of Nyanza and other bureaucrats in the Medical, Lands, Public Works and Housing Departments were deeply involved in the process of planning and construction. The archival documents capture a mood of excited optimism, pride, anticipation and expectation in the new hospital as a site of medical modernity.Footnote 10 The hospital was a public project. It was to be a hospital for everyone, an inclusive project of national development and nation building, and the Kenyan public had great interest in it and high expectations. For example, on 24 October 1963, just before independence, Dr Aruwa, Regional Medical Officer (RMO), wrote to the Ministry for Works, Communication and Power in Nairobi: ‘The provision of the new hospital in Kisumu is a matter that exercises the minds of the local population to a very large degree.’ He continued, ‘The people of the region are anxious that the hospital be built as soon as possible.’Footnote 11

His successor, the PMO Dr Ouya, wrote on 22 July 1964: ‘I am receiving so many verbal questions on the proposed hospital that I would be grateful if you could let me know where the matter stands at present.’Footnote 12

Dr Ouya's letters were written several times a week, and sometimes daily, to various ministries, bureaucrats, medical experts, engineers and building contractors. From 1964 until its completion in 1968, and beyond, he pursued the project with incredible energy and enthusiasm.Footnote 13 He seemed to take it upon himself to make the hospital ‘the best’ in East Africa, describing it as ‘the most modern’, with the most ‘excellent’ facilities, as the ‘leading’ hospital in the East African region, and as ‘dealing with the latest drugs’.Footnote 14 In a letter dated 16 January 1967, he writes: ‘The facilities offered at the new hospital would probably be equal to anything else in East Africa … I feel that the hospital will be a show piece in Kenya as it will be the most modern and up to date.’Footnote 15

As planning progressed, Dr Ouya paid attention to the most miniscule details concerning equipment and the needs of future staff and patients. He argued that even the non-medical departments should set the best of standards. His imagining of an expansive future extended even to a detailed description of the diet of the hospital's patients: ‘As the leading medical institution in west Kenya … it will be up to us to set the best standard of nutrition … We have planned an ideal diet.’Footnote 16

For Dr Ouya, the hospital represented a new relationship between the state and its citizens: a place of the future – ordered, efficient, with the ‘latest drugs’ and ‘up-to-date technology’, offering patients ‘state-of-the-art’ care down to ‘the best standard of nutrition’.Footnote 17 For him, the new hospital looked to the future, away from the past. It was to be a symbol of the new postcolonial nation, one that made a statement about the possibility of rapid progress and about Kenyans’ aspirations for global equality.

The new hospital also stood as a symbol of new alliances with the Eastern Bloc and thus of a different model of development. The USSR pursued development in the ‘Third World’ as one based on solidarity within the Socialist bloc rather than on imperialist hierarchies. Demonstrations of this solidarity included not only the construction of hospitals and other architectural and development projects (Stanek Reference Stanek2012; Stanek and Avermaete Reference Stanek and Avermaete2012), but also the provision of Soviet expertise and the training of Africans in the USSR on generous scholarships (which I return to later). The Kenyan doctors I interviewed, who had worked with the Russians at the hospital from 1969 to the 1970s, spoke warmly of friendship with the Russian doctors, of teamwork, sharing vodka and dinner parties – a pattern of socializing that contrasted starkly with their experiences of British stiffness and formality.Footnote 18

Alongside hopes and expectations surrounding the hospital, the archival material also suggested that there were anxieties about the hospital's success, driven by political tensions in Kenya that were fuelled by Cold War politics.

Cold War tensions

Dr Ouya's visions of the hospital as a ‘showpiece’ in Kenya, and the erasure of these visions, were tied to the East African experience of the Cold War and the ways it played out in Kenya. The archival materials suggest that most Kenyans (town residents, government bureaucrats, medical officers) did not regard the ‘Russian-built hospital’ as a materialization or exportation of Soviet ideologies but instead approached it as a ‘gift’ from the Soviet Union to the Kenyan people, a materialization of good will (see Humphrey Reference Humphrey2005).Footnote 19 However, the hospital project was a crucial node in Cold War politics, and, in particular, the tension between capitalist and socialist futures. While President Kenyatta was courting Western countries and stressing the continuity of British economic interests and the protection of private property, Oginga Odinga found an alternative vision of development and alignment in the Soviet Union's anti-imperialist rhetoric and socialism (Ochieng’ Reference Ochieng’, Ogot and Ochieng’1995; Swainson Reference Swainson1980).Footnote 20 He made no secret of his pursuit of closer ties with the USSR, the People's Republic of China and other countries of the Warsaw Pact, and he articulated a vision of redistribution that appealed to Kenyans disillusioned with their exclusion from capitalist development (Branch Reference Branch2011). In competition with the American ‘airlifts’ organized by Tom Mboya, the USSR, through Odinga, began offering scholarship programmes for African students (the first Kenyan cohort studied in Moscow in 1959) and in 1961 renamed the Peoples’ Friendship University the Patrice Lumumba University in memory of the assassinated Congolese leader. In 1964, the Lumumba Institute was established in Nairobi. Set up through Odinga and funded by the USSR, China, India and Eastern Bloc countries, it aimed to train student activists affiliated to the (sole) political party – the Kenyan African National Union (KANU)Footnote 21 – and ‘to elaborate the spirit of harambee’. It was soon accused of being a secret training centre for communist agents and a ‘hotbed of radicalism’; in April 1964, Odinga's offices were raided and he was accused of plotting with the Soviet Union against the government (Branch Reference Branch2011: 48–52; Rothmyer Reference Rothmyer2018: 136–8). Then, in early 1965, students at the Lumumba Institute were arrested after staging a mock coup against KANU leaders.Footnote 22 Tensions rose as some Soviet and Chinese diplomatic staff were expelled from Kenya and Kenyatta warned Kenyans against the ‘dangers of imperialism from the East’ (Duignan and Lewis Reference Duignan and Lewis1994: 8).

Somewhat surprisingly, given these tensions and attempts to isolate Odinga and ‘the radicals’ (Branch Reference Branch2011), the Kenyan government accepted the Soviet Union's offer in 1964 to build a new ‘super modern’ hospital. Like the Lumumba Institute, the hospital materialized the close connections between Odinga (whose son, Raila, was educated in the DDR in the 1970s) and the USSR. Soviet delegates were welcomed in Kisumu, and a Soviet architect and planners got to work. The hospital project went ahead, although the letters exchanged between the PMO Dr Ouya and the ministries in Nairobi suggest that it was neglected by the central government, as Dr Ouya's requests for support were often ignored.

Between 1965 and 1968, tensions between Kenyatta and Oginga Odinga continued to rise. When Odinga founded his new political party, the Kenya People's Union (KPU), in 1966, he was again accused of Soviet-supported agitation against the government. As recounted above, matters came to a head during the hospital's opening ceremony in October 1969. Two months earlier, the popular politician Tom Mboya had been assassinated, and Kisumu, already regarded as the seat of political opposition, was tense. According to historian Daniel Branch, Kenyatta anticipated a showdown with Odinga and had given his bodyguards ‘clear and unequivocal orders prior to the visit to Kisumu to “shoot to kill when the first stone is thrown”’ (Branch Reference Branch2011: 88). As his entourage arrived at the hospital's grounds, some of the 5,000-strong crowd began heckling and throwing stones. The police made arrests, while Kenyatta continued with the opening ceremony, warning Odinga publicly that he would arrest him. Hecklers interrupted Kenyatta throughout his incendiary speech and clashes broke out between KANU and KPU supporters. Kenyatta was rushed into his car and out of the hospital. His bodyguards opened fire on the crowds alongside the road (ibid.). The hospital, a site of hope in the future, in modernity and progress, became the scene of state violence and repression (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Fleeing gunfire. Source: Gekara (2009).

Silence and the body politic

In the archives, the opening ceremony and its aftermath are marked by silence. PMO Dr Ouya, who was normally so vocal, was silent on this occasion. I found only one document that alluded to the violence: a letter dated November 1969, from the then Provincial Matron (a British woman) to the staff of the ‘new Russian-built hospital’:

I would like to express my thanks to all members of staff for the tremendous effort they made to ensure that the hospital was clean and in good order for the Presidential visit. The hospital looked spotless, the patients looked comfortable and well cared for and many people remarked on this to me. We are all very sad that this occasion was marred by tragedy. I would like to thank all those who rendered assistance to the injured … I was immensely impressed by the way you all acted in this crisis and I wish you to accept these few lines as a token of appreciation.Footnote 23

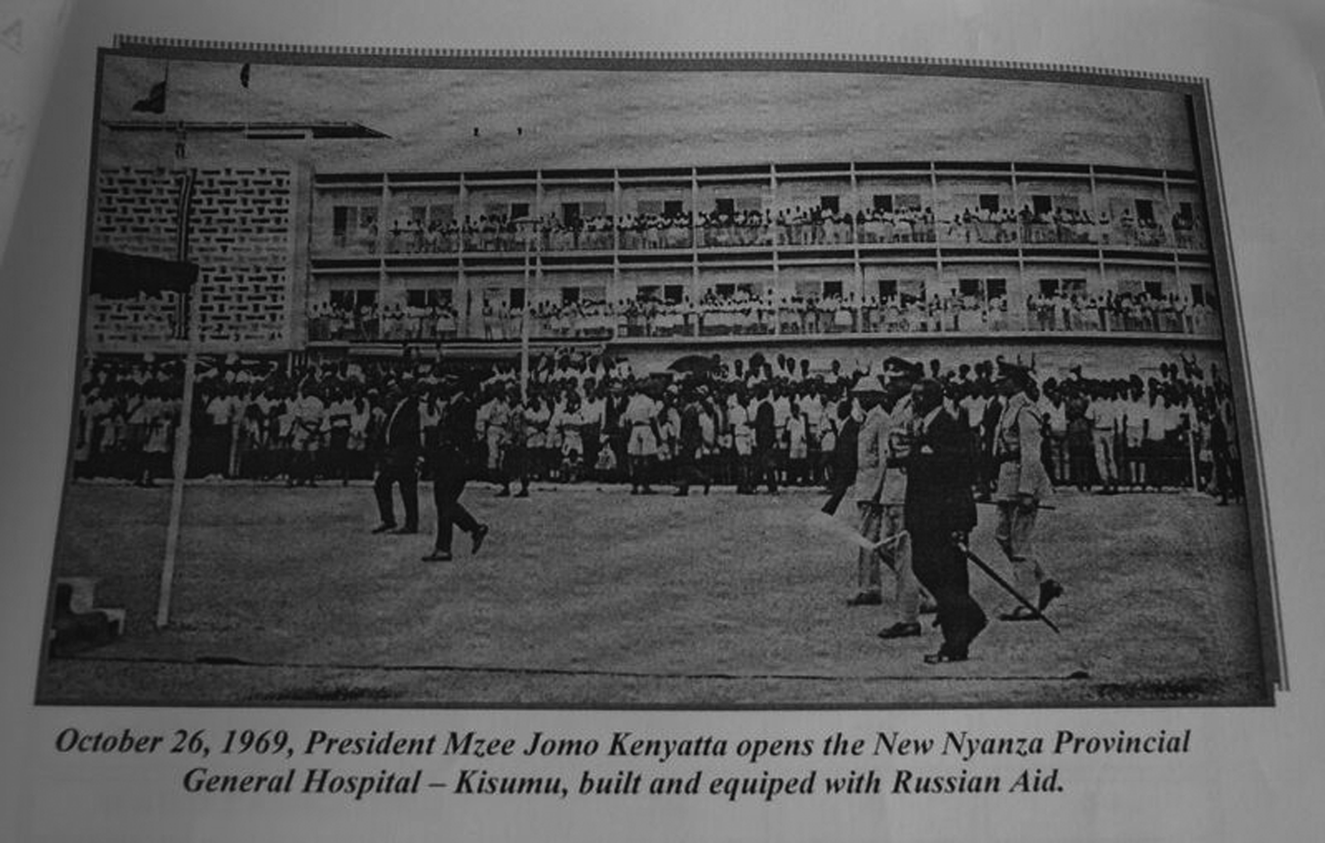

In the hospital's self-presentation documents (a report giving an overview of the hospital's services, activities, donors and partners, printed in 2011) I found only the official photograph of the opening ceremony, taken before the massacre. It shows Kenyatta as he tours the hospital grounds. The photograph suggests the pomp and splendour of that day and its promise of a bright future (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Opening ceremony in October 1969: ‘President Mzee Jomo Kenyatta opens the New Nyanza Provincial General Hospital, Kisumu, built and equipped with Russian Aid’. Source: Ministry of Medical Services, New Nyanza General Hospital, 2011.

Fifty years later, however, media attention to the violence of the opening ceremony prompted Kenyans to reflect on social media on the achievements and failures of the postcolonial state. On pursuing the trail left by the photograph published in The Standard in 2009 (Figure 4), I found an online conversation on YouTube, following the uploading of Kenyatta's speech made at Russia's opening ceremony:

I attended this function as a nine-year-old. I had to run for my life and luckily we lived in the hospital grounds and the run for dear life was thus shorter for me than for most. We revered Kenyatta, but now as a grown up I can look at his record with better lenses. I find little positive that this man contributed to the well being of the nation he purported to have created; tribalism, nepotism, corruption, dictatorship, and theft are just but a few of the ills he bequeathed to the rest of us.Footnote 24

Violence was present, then, at the heart of the dreams of progress, of new futures, of equality, solidarity and inclusion that we now associate with the 1960s and 1970s.Footnote 25 At its birth, the hospital was a place already mired in the tensions surrounding the new postcolonial state. During its official opening to the public, a moment full of anticipation for the future, dream became nightmare. At the event meant to demonstrate the care and concern of the state for the health of its citizens, the hospital became a site of state-directed violence against those very bodies it had promised to protect. The photograph of fleeing schoolchildren suggests an uneven history of state concern, neglect, violence and care. Rather than sketching a contrast between a past of bright futures and a dystopian present, we arrive instead at a space of contradiction. The hospital, as a place that has endured these events, also connects them.

Through all these events, the archival material remains strangely apolitical. Conflicting visions of development, which became visible in the violence of Russia's opening ceremony, are submerged and erased in the ongoing bureaucracy of administration. What appears visible is the depoliticizing of these pasts (Stoler Reference Stoler2009). Science, medicine, progress and development were to be presented and remembered, it seems, as non-political, as collective and thus as neutral, something universal in which everyone could share (Anderson Reference Anderson2002). It is as if the hospital's place and role as a ‘utopic geography of hope and potentiality’ (Anderson Reference Anderson2006: 693) could not accommodate the politics of its birth. Yet one discerns a repository of this hope in Dr Ouya's striving to depoliticize Russia. His silence about the violence surrounding the opening ceremony suggests a hope that this place would remain one of progress, development and a better future. As politics could have no place in this vision, his response to the opening ceremony is silence. Could it be that in this move to depoliticize, in the amnesia and the wilful forgetting, there remains a desire to keep dreaming?

Other Soviet gifts

I have traced one knot of connections between Kenyans’ dreams of medical modernity, the Cold War and the present, beginning with Kenyans’ retrospective gaze at the violence surrounding Russia's birth. A second knot of entanglements between divergent pasts and present futures emerges from interviews I conducted with Kenyans trained as medical doctors in the USSR.

From the late 1950s, again through its ties with Odinga, the Soviet Union began offering scholarships for Kenyan students to study in the USSR.Footnote 26 Many studied at the Peoples’ Friendship University, set up in 1960 and renamed the Patrice Lumumba University after Lumumba's assassination in 1961. Set up to educate an elite from Asia, Africa and Latin America who were sympathetic to Soviet values, the university brought together students from the colonized and decolonizing world with students from the USSR and Eastern Bloc countries. Students were given full scholarships, including an allowance for clothes, travel, accommodation and food, and they were taught Russian. In addition to studying, they could travel and some volunteered to work during the holidays on projects that were promoted as ‘building Socialism’.Footnote 27 The Soviet Afro-Asian Solidarity Committee, which supported struggles for self-determination and freedom, was one of the university's founders, and student committees were politically active.Footnote 28

One of the doctors I interviewed was Odhiambo Olel, a resident of Kisumu, now retired from government service and currently running a small private medical practice (Figure 6). Olel's story connects the Soviet gift, dreams of medical modernity, socialist internationalism and anti-imperialism to the postcolonial struggles for multiparty democracy and dreams of political freedom in Kenya.Footnote 29

Figure 6 Dr Odhiambo Olel, 24 September 2013.

Born in 1935, Dr Olel grew up in Kenya during the late colonial era; in 1960, he received a scholarship from the Soviet Union's Afro-Asian Solidarity Scholarship Committee to study medicine at Moscow State University. Olel was the eldest child in a polygamous Christian family. His grandfather had been a porter during the First World War and, on returning to Kenya, made sure his children became literate. His father was a market clerk and one uncle was a ‘medical dresser’ for the Department of Health in Nakuru. Dr Olel began primary school in 1947 in Nakuru, a town he described as ‘a hotbed of settlers’, where he strongly remembers the racial segregation of white people from Africans. After secondary school in Uganda in the mid-1950s, Makerere University College offered to send him to the UK to qualify as a laboratory technician, but he wanted to study medicine, which the scholarship from the USSR enabled him to do. He described travelling in 1959, in the company of four other Kenyans, on a clandestine route from Uganda through Sudan to Egypt, from where he flew to the USSR.Footnote 30

On his arrival in Moscow in 1960, Olel had to learn Russian. ‘It was not difficult. Science was universal!’ he told me in our first interview. ‘And you know,’ he continued, ‘we were ambitious. We were activists. We wanted to be a good example; we did not want to fail. It was that time of the Cold War.’ He explained, ‘Those early years were very difficult for us who were still under colonial rule. Some of us were very bitter with the ruthless rule and discrimination on racial grounds [which] made us agitate politically.’ He described the impact that the independence of countries such as India, Indonesia and Ghana had on his own and his fellow students’ political activism: ‘We felt it was time to play our role in the political emancipation of our people.’ In the USSR, he met students from the ‘Third World’, then mostly still under colonial rule, who were brought together by the Afro-Asian Solidarity Committee. He explained:

We had an Afro-Asian Solidarity Committee, inspired by the Bandung Conference in Indonesia which brought together African and Asian leaders of newly independent countries and countries fighting for their freedom from colonial rule, and the non-aligned movement. Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, Abdel Nasser, Haile Selassie and Kwame Nkrumah. They were hot-headed people!

During his time in the USSR, the ‘solidarity’ shared by students from Africa, Asia and Latin America and the warm friendships they enjoyed with the Russians left a deep impression on him. While studying medicine, Olel became a student leader and participated in demonstrations against colonialism. In 1961, he and other African, Asian and Latin American students protested outside the American, Belgian and British embassies in Moscow against the assassination of Patrice Lumumba. As he recalled:

We demonstrated in 1961 when Lumumba was killed. We smashed the windows of the British and American and Belgian embassies in Moscow. We were joined by Latin American students and by students from the Far East … We were hot-headed then! As students. We felt the British had mistreated us. We wanted a change … That was the time of the Cold War, of ideology. We were siding with the USSR, we felt that they were on our side to fight the British, in the British colonies.

Olel remained in the USSR for eight years, returning to Kenya in 1968. After an internship at Kenyatta National Hospital in Nairobi, he served in the Kenyan Ministry of Health and then the Kisumu municipality from 1970 to 1990. He also continued his political activism, joining the doctors’ strike in October 1971,Footnote 31 during which he was arrested for three days. This experience pushed him to resign from Ministry of Health employment, and in 1972 he instead took up the post of Chief Medical Officer in charge of health in Kisumu, employed by the municipality.Footnote 32 In 1973, the municipality sent Olel for postgraduate training in public health at Makerere University, and in 1974 he spent time in Prague, Geneva and New Delhi for further training under the auspices of the World Health Organization (WHO).

After Kenyatta's death in 1978, his successor, Moi, tightened the one-party state's grip on power. This move, which continued Kenyatta-era arrests and detentions, compelled Dr Olel, like many others, into political activism (see Ogot Reference Ogot2010). He joined MwaKenya, an organization that, according to Daniel Branch, originated among Nairobi dissidents involved in the 1982 coup attempt against Moi's government.Footnote 33 It spread to the universities and advocated, peacefully, for multiparty democracy.Footnote 34 In 1982, Moi's government changed the constitution to make Kenya a de jure one-party state, and, after a failed military coup in August 1982, it arrested university professors, banned MwaKenya and ruthlessly pursued anyone associated with it. In 1983, as the government cracked down on dissent, Dr Olel was again arrested and spent three days in a police cell ‘under suspicion I was a member of a clandestine organization publishing and distributing [the] mambana/mpatanishi newsletter which was critical against Moi's regime’. He was released as ‘the document was not found on me’. In 1986, he was arrested for the third time and spent seventeen days in solitary confinement in the notorious Nyayo House, where he was tortured.Footnote 35 He was convicted of being a member of MwaKenya, given a five-year sentence, and on 20 March 1987 he was sent to Kamiti, Kenya's maximum-security prison. After a successful appeal he was released after two years. On 7 July 1991, Olel was again arrested for participating in demands for the end of one-party rule. He spent five days in a police cell and was granted release on condition that he refrain from political activities for six months. For those six months, he told me, ‘I kept my peace.’ In December 1991, under intense pressure from Western donors, the Kenyan parliament repealed section 2A of the constitution (which restricted a second political party) and multiparty elections were held in 1992.

Dr Olel left government employment in 1990 but continued to run his private medical practice in Kisumu. Due to Dr Olel's political views and connections with the struggle for multiparty democracy, opposition figures, including Oginga Odinga, were among his regular patients.Footnote 36

During our interviews and in later conversations and email exchanges, Dr Olel presented his student years in the USSR as a time when his horizons opened, and he, along with other Africans, Latin Americans and Asians, participated in a world that was freeing itself from imperialism, where ‘science was universal’ and progress meant entry into a world of equal nations. He remembers the Soviet gift as one of friendship and solidarity, of conviviality and discovery, as cultivating a connection and relationship that could reach into the future. He contrasted this with the British: ‘The British did not think of the future. What kinds of relations were they building? They were not building friendship. That [kind of relationship] was not sustainable.’

Dr Olel's story is one of expanding opportunities. Horizons were opening up and young Africans and Asians like him found inspiration and support from the Socialist bloc. Dr Olel brought what he learned about the struggle against imperialism and aspirations for postcolonial nationhood back to Kenya and to the struggle for democracy there. It is clear that Olel's life and career have been intimately tied to postcolonial politics, with its hopes and dreams, disappointments and betrayals, for which he made personal sacrifices and for which he also suffered.

Dr Olel's career and those of his generation stand in marked contrast to the aspirations and experiences of Kenya's new generation of medical graduates, trained in Kenyan medical schools. In 2013–14, I interviewed some of them. While the majority had studied medicine in one of Kenya's thriving medical schools, one intern (whom I refer to as Dr S) had taken a medical degree at the Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia (renamed in 1992), from 2008 to 2013, on a competitive scholarship. After the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991, Russia has continued to offer some scholarships to African students (as does China). Such opportunities are exceedingly scarce, however. According to Dr S, African students encounter a great degree of hardship in the new Russia, a hardship that seems absent from the accounts of the older generation (even taking into account the tendency to romanticize one's youth).Footnote 37 While my interviewees of Dr Olel's generation acknowledged that having ‘black skin’ made them stand out, few remembered acts of racism; instead, they recalled the friendship and warmth of Russian hospitality. Some married Russians. Dr S, however, recalled his fear of racist skinheads and of walking alone on the streets. In contrast to the generous scholarships of the past, studying in Russia today is also a financial struggle, even with a scholarship.

The interviews I conducted with the interns underline another shift in generational experience. This is the disjuncture between the high optimism of medical modernity during the 1960s – embodied in the description of the new hospital as being ‘state of the art’ and having the ‘best facilities’ in the region – and the realities of medical treatment and care in a Kenyan public hospital today, after structural adjustment and amidst continuing austerity. Government work offers few benefits and young medics instead seek careers within NGOs and foreign-funded medical research or look for a life outside the country.

Through a glass darkly: Russia in 1969 and 2015

What visions have we been formed by, yet forgotten? What visions have we let shrivel, fester, or fall away? (Tsing Reference Tsing2005: 81)

‘Knowledge that travels today is haunted by the disappointments of past visions,’ writes Anna Tsing in her ethnography of environmental activism in Indonesia (Reference Tsing2005: 81). In a chapter that takes Sukarno's opening speech to the Bandung Conference in 1955 and ‘Let a new Asia and a new Africa be born!’ as its motto, she ponders the legacies of the Bandung Conference and its aspirations for world peace and unity, its dreams of a rising ‘Third World’ and its belief in modernization, science and progress. The Bandung Conference offered, Tsing argues, a universal bridge to a ‘global dream space’ of peace, unity and freedom. Yet it did not last, as these dreams became intermeshed with Cold War politics, elite power grabs, authoritarian regimes and imperial remains. Bandung's visions have seemingly perished, contained now only in museum cases commemorating the conference. ‘How old and obsolete’ these dreams seem, comments Tsing. We see them through a glass darkly. ‘As the future has shifted, the past contorts, confused’ (ibid.: 84).

In this article I have taken Tsing's question ‘What visions have we been formed by, yet forgotten?’ as a challenge to explore past dreams and visions of past futures, the frictions as well as the trajectories that they created. The newspaper coverage of Russia's opening ceremony in October 1969 unearthed a place where dreams and expectations of progress and development collided with disappointment and betrayal. Probing the story of this hospital does not reveal a linear trajectory from the time of ‘high optimism’ in African futures (Droney Reference Droney2014) to a now familiar trope of ruination and neglect. Instead, it suggests the past as a field of struggle (Atieno-Odhiambo Reference Atieno-Odhiambo, Ogot and Ochieng’1995; Ogot Reference Ogot2010) and Russia as a place where diverging and opposed dreams and anticipations of postcolonial progress and development converged and collided. However, this politicization of development – and the hospital as a politicized space – remains submerged.

For postcolonial nations, medicine and science offered paths to universal progress (Anderson and Pols Reference Anderson and Pols2012). They were ‘dream-bridges for the development of Third World nations’ (Tsing Reference Tsing2005: 85) and ‘transformational projects aimed at altering local and global hierarchies’ (Tousignant Reference Tousignant2013: 730; see Anderson Reference Anderson2009; Geissler Reference Geissler, Geissler and Molyneux2011). The postcolonial moment opened up many futures. In the hopes and aspirations that Kenyan civil servants brought to the Russian hospital and that I found in the paper trails they left, and in Dr Olel's trajectory from colonial subject growing up in a racially segmented country to medical student at Patrice Lumumba University in Moscow, we discern the affective, material, institutional and personal resonances of these hopeful times. These stories suggest the possibilities that existed for advancement, medical careers and participation in medical science, along with opportunities for shaping political futures (Cooper Reference Cooper1994; Iliffe Reference Iliffe1998; Anderson and Pols Reference Anderson and Pols2012). These were optimistic times, when, in Olel's words, ‘science was universal’ and progress appeared to be so too. In Kisumu, such promises materialized in the plans for a new, state-of-the-art hospital for the postcolonial nation.

Yet promises of inclusion in new trajectories of progress faced the contingencies of Cold War politics, while Kenya's increasingly repressive and authoritarian politics sowed an acute sense of betrayal, disappointment and distrust. Planned as a celebration of medical modernity, Russia's opening ceremony ushered in a new era of state repression, which continued through the 1970s and 1980s. Backed up by Western interests, elite capture of the country's resources ensured that the promises of uhuru – of shared progress and collective development – failed to materialize. In Kisumu, these were years of stasis. After 1969 and the effective suppression of political opposition along with Kenya's ties to the USSR, the region experienced years of political and economic marginalization and an acute sense of exclusion from development taking place elsewhere.

Tsing suggests that the present is haunted by the disappointments of past visions. Can haunting describe the presence of Kenya's pasts, its past connections and past futures?Footnote 38 Haunting reaches towards the echoes of different pasts, ‘inchoate yet lingering on’ in Kisumu and in the lives, trajectories and struggles of some of its residents. Russia's opening ceremony haunts Kenyan dreams of progress as it reveals a nation already fragmented. Seen from the present, the event marks a moment when dreams of uhuru, of postcolonial nationhood and societal progress began unravelling. Who remembers these dreams, visions and struggles now? And if they are forgotten and obsolete, why should we attend to them at all? Tsing's approach is useful because she explores what remains in the gap between dreams of the past and struggles over the future. Her observation ‘How few today remember the meeting in Bandung’ marks a beginning as she explores how knowledge travels, producing new encounters and creating frictions. If ‘the bridge to the global dream space was universal truths, science, modernization and political freedom, the inadequacy of the bridge seems hardly a good enough reason to have abandoned the quest’ (Reference Tsing2005: 85).

From the turn of the twenty-first century, Kisumu's experience of being on the margins has changed. Odinga's son, Raila, educated in East Germany from 1963 to 1970, served in the government from 2001 to 2005 and as prime minister from 2008 to 2013 in the coalition created after the violently disputed election results of December 2007. Raila directed new infrastructural investment towards Kisumu and its hinterlands, including contracts with Chinese companies for multi-lane highways. Together with the investment of returnee Luo diaspora in property, this has created a boom in land prices and the property market. Meanwhile, Kisumu's status as a hotspot of global health funding also created a flurry of activity. Since the early 2000s, the proliferation of NGOs and research institutions, dominated by American funding, has created jobs and opportunities, albeit transient ones (Prince Reference Prince2013; Reference Prince2015). Amidst these fast-lane developments, Kisumu's middle-class residents are looking to the future, to the new private hospitals advertised on huge billboards promising state-of-the-art medical treatment and medical insurance giving access to ‘world-class care’, and at the new shopping malls, motorways and flyovers. These circulations and constructions materialize Kisumu's participation in global modernity, offering connections between the city and the rest of the world. They put Kisumu on the global map and demonstrate how far it has developed. Kisumu is no longer being left behind. Even those excluded from the fruits of these developments (the majority of the city's residents) are drawn into this vision of progress.

The excitement about global futures alongside the acceptance of Kenya's socio-economic inequalities as a fact of life is revealing of the contemporary moment in which dreams of collective futures have been reduced to fears and anxieties about securing individual livelihoods.Footnote 39 For Kenya's struggling middle classes, aspirations have been narrowed down to individual lives and the ability to grasp passing opportunities. It is clear that, for Kisumu's residents, the future no longer lies with Russia. Post-structural-adjustment, the hospital for the public has become a hospital for the poor. The nation as a location of collective betterment exerts little affective pull. Russia and the promise of public service it once projected are being bypassed by new medical modernities exemplified by public–private partnerships and global investments in a medical marketplace oriented to the needs of a privately insured middle class, effectively abandoning other members of society (Figure 7) (see Thomas Reference Thomas2016).

Figure 7 ‘Abandoned’: screenshot of The Standard front page, 20 September 2012.

The story of Russia, then, is not a story about nostalgia for the future, for the lost twentieth-century social collective and its visions for the part Kenyans and other Africans would play in the world and its futures. Rather, it is a story about amnesia and the neoliberal moment – the breathless ‘moving ahead’ that Kisumu's residents variously take pride in or complain about, and the attempt to keep up with the curve, to learn the language of global health and development and gain access to it (Prince Reference Prince2013). The future that the new modern public hospital stood for during the 1960s is very different from the future orientations that saturate the twenty-first-century city today. The violence of the hospital's opening materialized the ‘bitter intellectual and ideological struggle about the morality of development’ (Branch Reference Branch2011: 63), between Odinga's visions of redistribution and Kenyatta's embrace of corporate capitalism (Ochieng’ Reference Ochieng’, Ogot and Ochieng’1995). Today, the role that Russia played in the political and developmental futures of the city remains submerged in the flurry of projects and partnerships, infrastructural developments and new opportunities. These past political and ideological struggles and competing dreams about the future are not plumbed as a resource for dreaming or as terrains for imagining other kinds of futures. Yet their traces stubbornly surface in toponyms that animate the city's landscape and orient its inhabitants. The hospital's nickname, Russia, is echoed in the designation of a housing estate, built in the 1970s with Soviet aid, as ‘Moscow’, while the colonial hospital for the whites, which today acts as a private ward, is still referred to as ‘Victoria’. Others toponyms, such as the housing estates named after assassinated political figures, mark out struggles for freedom and for a political voice. ‘Lumumba Estates’ and ‘Lumumba Clinic’ remember the Congolese politician's assassination in 1961 amidst rumours of CIA involvement; ‘Tom Mboya Road’ is one of many sites recalling this popular politician (and friend of America); while ‘Robert Ouko Flats’ remembers the Kenyan foreign minister whose brutal murder in 1990 has never been properly investigated (Cohen and Odhiambo Reference Cohen and Odhiambo1992). These toponyms point in partial and incomplete ways to the struggles of the past. They speak to the city's political sympathies and solidarities, its participation in postcolonial politics and Cold War divisions, and its postcolonial dreams. They recall colonialism and point to independence and its promises, to developmental hopes and Cold War tensions and to postcolonial struggles for political freedom. They evoke the violent history of the nation and the struggle for political freedom amidst Western imperialism and government repression.

Beyond these signposts of past hopes and struggles, it takes a slowing down, an immersion in bureaucratic records, a picking up of paper trails and a careful exploration of disjointed connections and fragmented trajectories to seek out the dreams and the visions that Kisumu's residents participated in, held dearly, disagreed about and struggled towards. In this process, Russia, like the city it forms part of, emerges as a palimpsest, a site of hopes and dreams, violence and disappointment, and the anticipation of futures. Like the biography of Dr Olel, it also provides a gauge of the openings and closures of postcolonial dreams, aspirations for the future and expectations of progress.

Acknowledgements

The research on which this article is based was funded by a Norwegian Research Council independent (FRISAM) fellowship, and took place from 2013 to 2016, with follow-up research in 2017. I conducted interviews and observations with working and retired medical professionals, collected documents and newspaper articles, and followed relevant debates on social media. The research was conducted in collaboration with Dr Phelgona Otieno, KEMRI-CRC. Ethical and research approval was granted by KEMRI's Scientific Research Committee and Research Ethics Committee, by the hospital's Ethical Review Board, and by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD). I am immensely grateful to the hospital administration and staff for welcoming us, and to the staff at the Division of Vector-Borne Diseases, Kisumu. Special thanks to Biddy Odindo and Maulyn Akech for research assistance, to Philister Adhiambo Madiega for her support and warm hospitality, and to Dr Benson Mulemi of the Catholic University of East Africa for his advice. I gratefully acknowledge the archivists at the Nyanza Province Record Centre, Kisumu, and the Western Province Record Centre, Kakamega, for their help in locating the hospital files.