While international organizations (IOs) were long the exclusive preserve of member governments, the past decades have witnessed a shift toward forms of governance that involve transnational actors (TNAs) such as nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), philanthropic foundations, scientific communities, and multinational corporations. Increasingly, IOs are engaging transnational actors as policy experts, service providers, compliance watchdogs and stakeholder representatives.Footnote 1 IOs with a historical record of no or limited access, such as the World Bank and the World Trade Organization (WTO), have gradually opened up to TNAs, while IOs that already had a tradition of interaction, such as the United Nations (UN) and the Council of Europe, have become even more open. At the same time, fundamental differences in TNA access remain, both across and within IOs.

These developments present us with a set of puzzles. First, why would states, typically protective of national sovereignty and political influence, compromise their traditional monopoly of power in IOs? Second, what explains the dramatic growth in TNA access to IOs over recent decades, which contradicts common assumptions of stability in the design of IOs? Third, what accounts for remaining differences in openness across and within IOs? Common to all of these puzzles is the question of what has driven and constrained TNA access to produce the patterns we observe.

This article offers a comprehensive theoretical and empirical account of TNA access to IOs. Understanding TNA access is central to the theory and practice of global governance. Once we know where, how, and why IOs open up, we can get traction on some of the critical questions in world politics. When do states share authority with private actors? What drives the design of IOs? How does TNA involvement affect political outcomes in IOs? Can openness toward civil society actors help ameliorate democratic deficits in global governance?

We conceive of TNA access as a dimension of the institutional design of IOs, similar to dimensions such as policy remit, geographical scope, and the autonomy of IO bodies.Footnote 2 Access is distinct from participation, even if the two often go together. Whereas access consists of the institutional mechanisms whereby TNAs may take part in the policy process of an IO, and may be granted either by the member states of an IO or by international bureaucracies servicing the IO, participation denotes TNAs' presence in these institutional venues. In this article, we focus exclusively on institutional access.Footnote 3 We define TNAs as private nonprofit or for-profit actors that operate in relation to IOs.Footnote 4 We treat them as one category because we have no strong theoretical reason to restrict the empirical scope to only a subset of private actors. Moreover, while IOs typically emphasize criteria such as competence and activities in multiple countries, they seldom discriminate between nonprofit and for-profit actors when granting access.

Our analysis builds on a novel data set, covering formal TNA access to 298 organizational bodies from fifty IOs over the time period 1950 to 2010. On the basis of this data set, we identify the most profound patterns in TNA access across time, issue areas, policy functions, and world regions, and statistically test competing explanations of the variation in TNA access. This research design breaks with previous scholarship on TNA involvement in IOs, which is dominated by accounts of single IOs or issue areas. Existing research boasts a rich set of in-depth studies of individual IOs, such as the UN, the WTO, and the European Union (EU).Footnote 5 Some studies expand beyond individual IOs, addressing TNA involvement within a particular issue area such as economic governance, environmental politics, human rights, and development.Footnote 6 So far, however, there are few studies with a comparative scope and no comprehensive large-N studies.Footnote 7

We argue that variation in TNA access within and across IOs is explained mainly by a combination of three causal factors: demand for the resources and services of TNAs, domestic democratic standards in the membership of IOs, and state concerns with national sovereignty. The principal drivers of openness in global governance have been functional demands for TNA resources that enable IOs to address governance problems more efficiently and effectively, and domestic democracy among the member states of IOs. Sovereignty costs associated with reductions in state control have been the principal constraint on TNA access, also contributing to distinct patterns of variation across policy functions and issue areas. The central transformative event in the historical development of TNA access was the end of the Cold War, which led to growing functional demands for TNA involvement in international cooperation, strengthened the voice of democratic states within IOs, and loosened the constraint of national sovereignty.

By contrast, we find only limited support for the conventional wisdom in existing research, which suggests that patterns of TNA access reflect the spread of a participatory norm in global governance. According to this argument, IOs have expanded TNA access, either because policy-makers have been socialized into believing in the appropriateness of participatory governance, or because they have adapted strategically to this norm for purposes of organizational legitimation. We conclude that a selection bias in existing research has led it to overestimate the general importance of norm change as a source of growing openness in global governance. Contributions that privilege norm adaptation tend to focus on the UN, the EU, and the large economic multilaterals, which probably offer the best examples of this logic at work, but are unrepresentative of the general population of IOs in this regard.

The article proceeds in four steps. First, we introduce the data set and map the transnational turn in global governance, presenting descriptive data on patterns in TNA access. Second, we outline the two theoretical accounts of TNA access, and derive testable hypotheses. Third, we assess these alternative arguments on the basis of a statistical analysis. Finally, we summarize our findings and outline the implications of our analysis for research on international institutional design, transnational influence, and democracy in global governance.

TNA Access in Global Governance, 1950–2010

IOs display extensive variation in the organization of TNA involvement. We describe the principal patterns of variation on the basis of a new data set on formal TNA access to 298 bodies of fifty IOs over the sixty-year period 1950–2010. The selected IOs comprise a stratified random sample. This sample was drawn from a list of 182 IOs that were identified by applying a set of five criteria to the Correlates of War IGO data set.Footnote 8 To be included an organization must: (1) be intergovernmental; (2) be independent from other IOs regarding budget, decision making, and reporting requirements; (3) have at least three members; (4) have at least one organizational body that operates on a permanent basis; and (5) be active in 2010.

To ensure that the sample represents the breadth of the IGO population, we applied stratified random sampling. The 182 IOs were categorized into ten issue areas and five world regions. Then, a random sample was drawn from each category, leading to a final set of fifty IOs.Footnote 9 As a result, our sample includes both major, well-known IOs, such as the UN and the WTO, and lesser-known regional or specialized organizations, such as the Wassenaar Arrangement and the International Coffee Organization.

We operate with IO bodies, such as ministerial councils, committees, and secretariats, as the unit of analysis. IOs are not monolithic entities and, as we shall show, TNA access varies within as well as across IOs. A focus on IO bodies thus permits a more fine-grained and comprehensive analysis of variation in TNA access in global governance. The data set exclusively captures formal access to IO bodies, as laid down in treaty provisions, rules of procedure, ministerial decisions, policy guidelines, or equivalent.Footnote 10 The data have been collected on the basis of documents from archives, databases, and direct data requests to the relevant IOs. The data set does not capture informal access to IO bodies developed through customs and practices.Footnote 11

We measure TNA access with a composite index that contains four dimensions of access. First, the depth of access captures the level of involvement offered to TNAs through institutional rules, and covers a continuum from active and direct involvement, sometimes mirroring that of member states, to passive and indirect involvement, such as observing negotiations. Second, the range of access captures the breadth of TNAs entitled to participate, and includes a spectrum from all interested TNAs to only those that fulfill a very restrictive set of selection criteria. Table 1 summarizes the coding along these two primary dimensions of access, which are each measured on a five-point scale.

Table 1. Measuring TNA access: Indicators for depth and range

In addition, the index contains two secondary dimensions. The permanence of access captures the extent to which institutional rules grant a permanent right for TNAs to be involved, or whether such privileges are ad hoc or by invitation.Footnote 12 The codification of access captures how access is legally regulated, and thus its revocability, by distinguishing between regulation through treaties, secondary legislation, or bureaucratic decisions.Footnote 13 The scores on each of these four dimensions are aggregated into a composite index. Depth and range form the additive component of the index because they are constitutive of access, defining what rights are granted to whom, while permanence and codification function as weighting factors because they shape the regularity and revocability of the depth and range of access. Since many IO bodies offer more than one type of access, the composite index is defined by the sum of all arrangements for each body, divided by the number of arrangements per body:

$$\eqalign{{\rm Access}_{{\rm ave}} & = \displaystyle{1 \over n}\sum\limits_1^n \lpar {\rm Range} + {\rm Depth\rpar }\,\times {\rm Permanence}\, {\rm \times }\, {\rm Codification}}$$

$$\eqalign{{\rm Access}_{{\rm ave}} & = \displaystyle{1 \over n}\sum\limits_1^n \lpar {\rm Range} + {\rm Depth\rpar }\,\times {\rm Permanence}\, {\rm \times }\, {\rm Codification}}$$

The data corroborate the existence of a profound shift in the design of IOs over time. Figure 1 displays the openness of IO bodies from 1950 to 2010, using the composite index. The figure reveals an increase in the formal openness of IOs over these sixty years, especially since 1990. From 1950 until 1990, TNA access was relatively low. In the period since 1990, there has been strong and continuous growth in TNA access. In 2010, seventy-one of 208 open IO bodies offered the maximum range of access, among them the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), and thirty-two bodies provided the maximum depth of access, such as the Business Advisory Council of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation.Footnote 14 At the same time, eighty-six bodies in the sample remained entirely closed, including the International Monetary Fund (IMF) Executive Board.

Figure 1. TNA access over time, 1950–2010 (index)

The frequency weights in Figure 1 show that the increase in the average level of TNA access is paralleled by a growing number of open IO bodies. About one quarter (26.5 percent) of the overtime trend stems from the creation of new IO bodies with access, while nearly three quarters (73.5 percent) are the product of institutional changes to existing IO bodies. Figure 1 also points to growing variation in the arrangements of TNA access, as illustrated by the dispersion of the frequency weights. In other words, there has not been a convergence toward a single standard of openness.

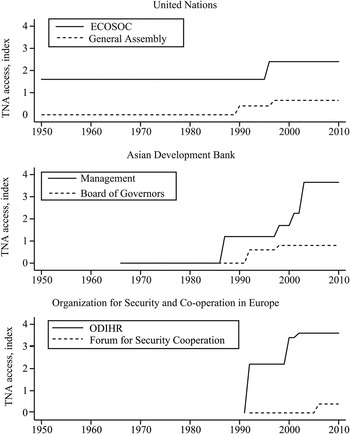

The arrangements for TNA access typically vary within IOs, confirming the appropriateness of IO bodies as the unit of analysis.Footnote 15 Figure 2 illustrates such internal variation within the UN, the Asian Development Bank (ADB), and the OSCE, contrasting examples of highly open IO bodies with less accessible bodies of the same IOs. In the UN, the General Assembly has been consistently less open than the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), which offered access from its founding. However, both bodies moved to more generous access in the 1980s and 1990s. The ADB did not offer access to the Management and the Board of Governors at its founding. In the mid-1980s, however, the Management began to provide TNAs access and has become more open since, while the Board of Governors opened later and to a lesser extent. The OSCE's ODIHR and Forum for Security Cooperation (FSC) were both created in the early 1990s. While the ODIHR was created as a very open body, the FSC has only recently begun to offer limited access.

Figure 2. Variation in TNA access within the United Nations, the Asian Development Bank, and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe

Figure 2 can also be used to illustrate our index. For example, the UN ECOSOC in 2010 received an index score of 2.4, based on three arrangements. One arrangement allows NGOs with consultative status (range = 2) to make statements at meetings (depth = 3) without additional restrictions (permanence = 1), as codified in Resolution 1996/31 (codification = 1). Similarly, the ADB Board of Governors received a score of 0.8 in 2010, equivalent to the sample mean, based on two arrangements. One of them originates from a policy paper (codification = 0.5), allowing accredited NGOs (range = 2) to participate in an NGO program parallel to annual meetings (depth = 2), but not lastingly (permanence = 0.5).

Previous research on civil society organizations (CSOs) in global governance, based on comparative case studies, has shown that the pattern of involvement varies across issue areas.Footnote 16 Our data confirm this assessment. Figure 3 shows the development of TNA access for ten issue areas, where the index scores represent the mean of IO bodies by issue area at a particular point in time.Footnote 17 In 2010, IO bodies in the field of human rights were by far the most open. Multi-issue bodies were the second-most open category, followed by development and trade. The lowest levels of openness could be found in finance and security.

Figure 3. TNA access across issue areas, 1950–2010 (index)

All issue areas have followed the same clear trend of an increase in openness over time, most notably after 1990. At a closer look, three additional patterns in the temporal development can be observed. First, IO bodies in human rights and development, as well as multi-issue bodies, have been pioneers of TNA access. Second, early differences in access have proven highly resilient over time, as IO bodies in some fields consistently have been the most open (human rights) or the most closed (security, finance). Third, unlike the overall trend of a steep increase from 1990 onward, access in some fields, such as environmental politics and commodity regulation, grew more linearly. Other issue areas, such as trade and security, became more accessible later and abruptly.

In addition, TNA access varies considerably across policy functions, as illustrated by Figure 4. IO bodies involved in monitoring and enforcement of member state compliance have been by far the most open category over the observation period. The second most open category in 2010, and during the first two decades of the observation period, was implementation bodies. Between 1970 and 1990, however, organizational bodies involved in policy formulation were more accessible than implementation bodies. Finally, the least open policy function in international cooperation has consistently been decision making. Yet, even in this category, we see a strong increase in the level of TNA access between 1990 and 2010.

Figure 4. TNA access across policy functions, 1950–2010 (index)

Access also varies across world regions. TNA access in 2010 was most extensive in North and South American, European, and global IOs, and less extensive in African and Asian IOs, even if the gap has decreased considerably in recent decades (Figure 5).

Figure 5. TNA access across world regions, 1950–2010 (index)

Explaining Transnational Access: Theories and Hypotheses

The previous section showed that the trend toward greater access for TNAs spans all areas of global governance, while at the same time significant variation continues to exist across multiple dimensions. In this section, we first outline the conventional wisdom on the expansion of TNA involvement, and then present our alternative argument.

The Conventional Wisdom: A Global Participatory Norm

The dominant explanation of TNA access in existing research privileges the emergence, spread, and consolidation of a participatory norm in global governance. This explanation is grounded in the constructivist notion that institutions reflect ideas and norms about what constitute appropriate and legitimate modes of governance. In this view, institutional design is a process where low priority is given to concerns of efficiency, compared with concerns of legitimacy. Norms define what institutional structures are appropriate in a given social community. Actors adapt to these institutional norms, either because they have internalized the norm as the “right thing to do,” or because they have learned what is expected of them.Footnote 18 The spread of norms about appropriate institutions gives rise to isomorphism, or the homogenization of institutional models across functional domains.Footnote 19

According to this argument, recent decades have witnessed the emergence and spread of a new norm about what constitutes legitimate global governance.Footnote 20 This norm conceives of TNAs as representatives of an emerging global civil society whose integration into policy-making can reduce the democratic deficits of IOs by strengthening participation, accountability, and transparency. While indirect representation through member governments was previously sufficient to legitimate IOs in democratic terms, the growing political authority of IOs requires that civil society becomes more directly involved in policy-making.

This argument comes in a “thick” and a “thin” constructivist version. Both are based primarily on case studies of a set of major IOs: the UN, the EU, and the large economic multilaterals. In the first version, member states and IO bureaucracies have introduced and expanded participatory arrangements because they have become socialized into believing in the normative appropriateness of this model. This argument is most frequently made in relation to the UN, where the participatory arrangements of ECOSOC, based on Article 71 of the UN Charter, are claimed to have established a powerful pro-NGO norm and “set a benchmark for other UN agencies.”Footnote 21 Others emphasize how the norm of NGO involvement spread and became consolidated through the large UN conferences of the 1980s and 1990s.Footnote 22 As a consequence, participatory governance nowadays constitutes the appropriate standard in the UN: “Whereas before, arguments were needed to justify the involvement of non-governmental actors in governance processes, now we face a reversal, so the pressure is there to justify the exclusion of non-state actors from governance processes, that is, to explain why the new norm of appropriate governance does not apply to the concrete case.”Footnote 23

Environmental and development policy are two areas of global governance where the pro-NGO norm of the UN is claimed to have been particularly influential. In the environmental domain, the UN Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm in 1972 involved a large number of CSOs, set up the inclusive UN Environmental Programme, and supposedly created a standard of openness for subsequent environmental conferences and negotiations.Footnote 24 In the development field, scholars trace the emergence of the participatory norm to the 1980s, when an ideational shift occurred away from state-led development and toward society-centered development.Footnote 25 The UN, through its Development Programme, was an early promoter of this norm and a subsequent model for other IOs.

In the “thin” constructivist version of the argument, the shift toward TNA access in global governance does not reflect socialization of policy-makers into this participatory norm, as much as adaptation to it for purposes of organizational legitimation. According to this argument, legitimacy is necessary for IOs to exercise authority and command compliance.Footnote 26 Where the design of IOs is a source of popular contention, decision makers may therefore adopt certain institutional features to secure legitimacy in relation to the external environment. Knowing what is prescribed by the prevailing norm, IO decision makers “act in accordance with expectations, irrespective of whether they like the role or agree with it.”Footnote 27 In this vein, O'Brien and colleagues argue that public opposition was the principal reason why the IMF, the World Bank, and WTO began to open up: “Under increased pressure from some elements of civil society for transparency and accountability the institutions have in the 1990s embarked upon a strategy of incremental reform. The intent is to extend and universalize existing multilateralism while blunting opposition through coopting hostile groups.”Footnote 28 Kissling and Steffek reach a similar conclusion, inspired by findings on the WTO, highlighting an “increasing willingness of international organizations to turn to CSO participation in order to confront the external criticism of their perceived missing legitimacy.”Footnote 29

In a similar manner, recent research speaks of IO openness as a consequence of “politicization” in global governance.Footnote 30 According to this argument, the conferral of increasing authority to IOs has subjected them to growing societal contestation. Prominent examples include the EU, the UN, the WTO, the World Bank, and the IMF. One of the expected effects of such growing politicization is expansion in TNA access. As Zürn hypothesizes: “International institutions that are politicized respond by giving greater access to transnational non-state actors as a move to increase legitimacy.”Footnote 31

Taken together, these variants of the conventional argument yield three complementary hypotheses.

H1

We expect IO bodies to open up as the participatory norm grows stronger and spreads, regardless of whether IO policy-makers have internalized or adapted defensively to it.

H2

We expect TNA access to be particularly high for IO bodies in policy areas and regions where the UN has engaged in participatory governance, reflecting its role as norm entrepreneur.

H3

We expect TNA access to be especially high for IO bodies that have been challenged by civil society actors, are at risk of being challenged, or are highly politicized.

The Argument: Functional Demand, Domestic Democracy, and State Sovereignty

The descriptive patterns identified earlier raise doubts about the extent to which the spread of a participatory norm can comprehensively explain TNA access. For instance, IO bodies offered access to TNAs even before the rise of a new participatory norm. Early differences in TNA access across issue areas, policy functions, and world regions have proven highly resilient over time. Access varies extensively within IOs, even though a participatory norm would lead us to expect more of a general organizational predisposition toward openness. These descriptive results lead us to develop an alternative argument about the factors that have driven and shaped TNA access to IOs. More specifically, we privilege a combination of three explanatory factors: functional demand for TNA resources and services, domestic democratic standards in the membership of IOs, and state concerns with national sovereignty. In the following, we outline the logic of each explanatory factor, and then explain how they come together in a distinct account of variation in TNA access.

The first explanatory factor emphasizes the expected benefits to states and IO bureaucracies of engaging TNAs. The logic is informed by rational functionalism, which explains institutional design by the benefits an institution is expected to produce.Footnote 32 It is also conformant with resource-exchange theory, which suggests that organizations seek to acquire the resources they lack through exchange with actors in their environment.Footnote 33 In line with this logic, we argue that IOs may offer TNAs access in anticipation of distinct functional gains. Whether TNAs can provide such gains or not is a product of the governance problems IOs confront.

Relative to other institutional solutions, the advantages of engaging TNAs are more pronounced where policy areas are technically complex, require local implementation, and present significant noncompliance incentives, and where the relevant information—policy expertise, implementation knowledge, and compliance information—is held by societal actors. Where these conditions apply, TNA involvement promises a more efficient and effective institutional solution than relying exclusively on state or supranational actors to assist IOs. TNAs are generally experts on the policy issues that most concern them (for example, business associations), are better positioned to implement policy at the societal level (for example, development NGOs), and have unique access to grassroots information on state violations (for example, human rights watchdogs).

More specifically, TNAs can offer valuable resources at three central stages of the policy process. To begin with, IOs may favor the inclusion of TNAs because they can provide valuable expertise at the stage of policy formulation. While many problems in global governance are characterized by uncertainty about policy options and effects, TNAs often specialize in collecting and providing policy information. Since this information generally is provided for free, it allows IOs to move research costs off-budget.Footnote 34 In addition, IOs may engage TNAs to perform implementation services. Most programmatic activities of IOs require implementation on the ground for which they are seldom optimally adapted. Outsourcing implementation to TNAs with local knowledge and capacity to reach the target population holds the promise of greater policy and resource efficiency.Footnote 35 Finally, IOs may offer access to TNAs to elicit their help in monitoring and enforcing compliance. International agreements frequently present states with noncompliance incentives. Where information on potential violations is decentralized, the monitoring of compliance from below by TNAs constitutes an effective and efficient alternative to oversight by IOs themselves.Footnote 36 In decision making, a corresponding functional advantage of TNA involvement is more difficult to identify. In fact, there may even be a disadvantage. As Raustiala notes: “When governments desire secrecy to air possible compromises, or are at the stage of logrolling once positions have solidified, they may find NGO participation undesirable or not useful.”Footnote 37

The second explanatory factor highlights the influence of democracies within IOs as a source of TNA access. This factor has analytical affinities with recent work on domestic political regimes and international cooperation.Footnote 38 It builds on the logic that states' preferences on the institutional design of IOs can be influenced by the nature of their domestic political regimes. Depending on whether they are democracies or autocracies, states may favor certain institutional design features. Given such regime-dependent differences in state preferences, the likelihood of these design features being adopted will vary across IOs depending on the composition of their membership.

The nature of domestic regimes can be expected to shape state preferences on the institutional design of IOs where design features tap into constitutive differences between democracies and autocracies. Such differences are free and fair elections, freedom of expression, transparency, accountability, rule of law, and an autonomous civil society. Extending such “democratic” features to IOs is likely to be a less radical step for democracies because it mainly involves applying the same procedural standards to all levels of political organization. Two examples of this logic are the establishment of public information policies and accountability mechanisms in global governance, which existing research shows are more likely when an IO's membership is democratic.Footnote 39

We assume that TNA access constitutes such a “democratic” institutional feature on which democracies and autocracies are likely to have different preferences. Democratic governments are used to interaction with civil society actors in domestic politics, and therefore are more likely to prefer the inclusion of TNAs in global governance. Autocracies, by contrast, are likely to resist TNA access, regarding it as a channel whereby domestic opposition groups can bypass the control of the regime and join their international allies in criticizing its policies.Footnote 40 By extension, we would expect IOs with democratic memberships to be more open to TNA involvement than IOs dominated by autocracies, and democratic transitions among an IO's membership to generate growing openness over time.

While functional benefits and domestic democracy are the drivers of access in our argument, state concerns for national sovereignty is the constraint. Sovereignty costs are frequently identified as restrictions on the delegation of authority from states to nonstate actors.Footnote 41 Sovereignty costs in this context result from reduced state control associated with the involvement of TNAs. Such sovereignty concerns can be assumed to vary across policy functions and issue areas.Footnote 42 First, the sovereignty costs of TNA access should be particularly high in IO decision making, where states adopt rules and principles, and in monitoring and enforcement, where states are held to their commitments and may face sanctions. Second, allowing TNAs access to policy-making should be perceived by states as more threatening in some issue areas than in others, for historical, cultural, and functional reasons. The costs should be highest when issues touch on elements of Westphalian sovereignty, notably, the territory and relations between the state and its citizens. Such issues are external and internal security, foreign policy, and asylum and immigration.

We test the core logic of this argument through three hypotheses—one for each explanatory factor:

H4

We expect higher TNA access for IO bodies engaged in governance tasks that are technically complex, require local programmatic activities, and present significant noncompliance incentives.

H5

We expect higher TNA access for IO bodies in organizations with more democratic memberships.

H6

We expect lower TNA access for IO bodies involved in policy functions and issue areas associated with high sovereignty costs.

In the following sections, we demonstrate how these three factors together provide the best comprehensive explanation of TNA access. We argue that the functional advantages of openness not only explain a central part of the expansion of access over time, as international cooperation has shifted toward governance problems that generate a stronger demand for TNA resources, but also persistent variation across policy functions and issue areas. The level of domestic democracy in the membership of IOs is also important to explaining the growing openness in global governance, following processes of national democratization, as well as variation across IOs and world regions in the readiness to engage with TNAs. The principal constraint on the expansion of TNA access are the sovereignty costs to states of reduced political control, which have contributed to variation in openness across policy functions and issue areas.

More specifically, we argue that these factors yield a two-stage account of the over-time development, reflected in the descriptive patterns identified earlier. All three factors have been at play in both periods, but with different intensity. During the period of 1950–90, functional benefits of TNA involvement meant that IOs limited access to TNAs where there was a clear functional need for their input. This translated into access in areas such as human rights and development, and in monitoring and enforcement. In parallel, domestic commitments to democracy led Western IOs to emerge as leaders in openness. Yet, throughout this period, state concerns with national sovereignty worked as a strong counterweight to functional and democratic pressures for IO openness. The effects were particularly prominent in the policy function and the issue area most closely associated with Westphalian sovereignty: decision making and international security. In all, this led to TNA access that was on average quite low by today's standards.

From about 1990 onward, TNA access to IOs expanded dramatically. The end of the Cold War acted as a catalyst that transformed global governance with consequences for TNA access (Figure 1). First, the end of the Cold War reinforced functional demand for the resources and services of TNA, as states broadened and deepened cooperation. In IOs that had been paralyzed by East-West tensions, the end of the Cold War removed political blockages and enabled states to set new policy ambitions.Footnote 43 In some areas of the world, it created space for ethnic tensions and conflicts to erupt, calling for IOs to act in new capacities, including conflict prevention, humanitarian interventions, and postconflict management.Footnote 44 In parallel, the ousting of authoritarian regimes was followed by unstable processes of democratic transition, calling for greater IO involvement in the monitoring of elections and human rights.Footnote 45 These developments generated higher access to IO bodies involved in implementation and monitoring, and in human rights and security. Second, the end of the Cold War brought about the democratization of many former authoritarian states.Footnote 46 In many IOs, this shifted the political balance in favor of greater openness, as the resistance of former authoritarian states to TNA involvement weakened, contributing to greater openness in formerly less democratic regions. Third, state commitments to sovereignty softened post-1989, reflected in a weakening of the principles of nonintervention and interstate cooperation.Footnote 47 While sovereignty concerns remained an important constraint on the extension of access, they did so with less intensity.

Determinants of TNA Access: A Multivariate Analysis

We now proceed to the multivariate assessment of the sources of variation in TNA access. We begin by briefly describing the measurements and models we use, before we turn to the results.

Operationalization and Model Specification

We assess the effects of a growing participatory norm (H1) based on the variable participatory discourse. Using the Google ngram tool, which includes more than five million publications from the Google books database, we develop an indicator that measures the strength of a participatory discourse based on references to the terms “democratic deficit,” “participatory governance,” and “global democracy” in scientific and nonscientific English-speaking publications.Footnote 48 The annual number of publications that include these terms are summarized into a common variable.Footnote 49 To avoid potential endogeneity and ensure that this variable represents the spread of a norm, participatory discourse is a lagged variable. While it is difficult to generalize how long a norm takes to spread, some scholars argue that socialization takes three to five years to observe.Footnote 50 A comparison of different time lags reveals that the effect of participatory discourse on the dependent variable is most pronounced between two and three years.Footnote 51 For these reasons, we operate with a three-year lag.

We test the effect of the UN as a norm leader (H2) through the indicator un conferences. Based on our data collection from research articles, conference reports, and UN documents, this variable measures whether the UN held special conferences in the same issue area or region as an IO body.Footnote 52

It includes information on fifty-one UN conferences between 1954 and 2009. The data are weighted by the number of official TNA representatives, since the effect of these events on the spread of a participatory norm is likely to be stronger if the number of participants is high. We also apply a time lag to test for a socialization effect. A comparison of different lags reveals that the effect of this variable is strongest after three to four years.Footnote 53 Thus, our variable combines a three- and a four-year lag.

We assess H3 through three variables intended to capture different aspects of challenges by civil society actors. First, we measure the effect of a direct challenge through the indicator protests against io. It captures media coverage of protests, assuming that protests making the news will lead decision makers to be concerned about the perceived legitimacy of an IO.Footnote 54

The data for this indicator were generated from the Lexis-Nexis academic database and include 6,270 articles from eighty daily newspapers in the category “world major newspaper” from 1960 to 2010. The articles were identified through keyword references to “demonstrator” and “protestor,” combined with the name of the organization.Footnote 55 We apply a three-year decreasing lag, assuming that the pressure for a strategic response will be strongest directly after the protest and weaken over time. We logarithmize the scale to limit the effect of outliers, such as the UN and the WTO. Second, building on the same data, we assess the risk of being challenged with the variable protests against similar ios, by which we mean IOs in the same policy area or world region.Footnote 56 We use the average scores for the media coverage of protests against IOs within ten policy areas and five regions, and apply the same decreasing three-year lag. Third, we assume that the visibility of an IO body in media coverage indicates the extent to which this body is politicized. We measure visibility in mass media using data compiled from LexisNexis. Based on the number of references to IO bodies in the New York Times and Le Monde, we use a three-step scale of many, few, and no references to categorize each IO body's coverage in the media.Footnote 57 These two newspapers complement each other's regional focus. More than one-third of the 298 IO bodies in our sample are mentioned. In a second step, we use references to the IO as a weighting factor to represent the over-time variation.Footnote 58

The hypothesis H4 refers to the nature of governance tasks. We expect higher access for IO bodies that engage in tasks that have technical complexity , require local activities, and present significant noncompliance incentives. We coded all 298 IO bodies according to these three dimensions, based on the description of their tasks in official documents and self-presentations. For each of the dimensions, we construct an indicator with a three-step scale, ranging from “not relevant,” to “somewhat relevant,” and “highly relevant.” In line with the underlying theoretical logic, the coding for each body is based on a combined assessment of the policy function and issue area in which it is active.Footnote 59

We test H5 based on an indicator that measures the average level of democracy in each IO's membership. Polity IV scores on “institutionalized democracy” from the Correlates of War (COW) data set are used as weights for the COW-IGO data on membership in IOs, which we updated for 2010 and adapted to our sample.Footnote 60 We add a one-year temporal lag to avoid representing the reverse effect of IOs affecting domestic political liberalization.Footnote 61

Third, to assess H6 we use two dummy variables; one measures whether a body is a decision-making body and the other if the body is involved in the field of security. We assume that the sovereignty costs of TNA access are higher for decision-making bodies and bodies in the field of security.

In addition, we include four control variables. First, some existing research argues that IOs with extensive resource deficits will have stronger incentives to involve TNAs.Footnote 62 For this reason, we include the variable io budget as an indicator of organizational resources.Footnote 63 These data were collected from IO websites, annual reports, direct contacts with the IOs, and the Yearbook of International Organizations.Footnote 64 We measure budget in millions of euros for 2010. The scale of the variable is logarithmized to normalize the effect of outliers.

Second, previous research suggests that member states vary in their support for TNA access, and that openness reforms are more likely when states have homogeneous preferences.Footnote 65 Accordingly, we control for preference heterogeneity with the variable affinity of member states. Using data on voting patterns in the UN General Assembly from the Affinity of Nations index, this variable captures the yearly average affinity of all pairwise combinations of member states of each IO in our sample.Footnote 66

Third, we control for power asymmetries, based on the idea that major powers carry more influence within IOs and will seek to promote or oppose TNAs depending on their preferences. The most prominent pattern, according to existing literature, is that major Western powers appear as defenders of TNAs, while major communist or authoritarian powers oppose their involvement.Footnote 67 We use an indicator that combines information on whether an IO has a major power in its membership with information on the domestic regimes of those powers.Footnote 68 The result is a democratic major power dummy for IOs that have at least one democratic major or regional power, but no undemocratic major or regional power that we can assume would veto access.

Finally, we assess whether the supply or availability of TNAs affects the extent to which they are granted access.Footnote 69 For these purposes, we construct the variable tna supply, which features time-series data on the broad set of NGOs accredited to the UN ECOSOC.Footnote 70 The indicator is based on the assumption that the number of NGOs accredited to ECOSOC fairly represents the worldwide population of TNAs. While the UN refers to NGOs rather than TNAs, its definition of NGOs is close to that of TNAs in substantive terms.Footnote 71 We disaggregate the data to measure the strength of the TNA supply by world regions, based on each NGO's country of registration. This variable thus indicates the average number of NGOs in the relevant regional reference group. To avoid endogeneity, we lag the variable by one year.

We test our hypotheses using Tobit regression analysis. Our choice of a Tobit model is driven by both methodological and theoretical considerations. First, we are equally interested in the likelihood and the degree of openness, and assume that our explanatory variables affect both dimensions. Second, deciding what level of access TNAs will be granted is usually made at the same time as the decision to open up a body. These two decisions are rarely made in a sequential way. Third, our dependent variable shows the distribution of a corner solution, and is left-censored at zero. The discrete component of this variable—whether or not the value equals zero—indicates whether a body provides access to TNAs. The continuous component, or all values greater than zero, represents the degree of TNA access for the average of all participatory arrangements per body.Footnote 72 With a logarithmic scale that limits the effect of outliers, the dependent variable follows an almost symmetric, bell-shaped distribution.Footnote 73 A Tobit estimator thus avoids the bias of an ordinary least squares (OLS) model for left-censored data, and enables us to exploit information from the theoretically relevant zero entries. We cluster standard errors at the body level to account for potential dependence between units.

We estimate a series of five Tobit models, as shown in Table 2, using the average scores of all participatory arrangements per IO body. Our three principal models use the index of TNA access as dependent variable. Model 1 estimates the effects for the full observation period 1950–2010, while Models 2 and 3 estimate the effects for the periods before and after 1990, respectively, to explore the possibility of a structural change in the explanation of TNA access. Recall that 1990 was identified as a turning point in the descriptive data (Figure 1). We display the estimated marginal effects of the independent variables in Model 1 in Figure 6. Moving beyond the index, we also estimate separate models for the depth (Model 4) and the range (Model 5) of access to assess whether the effects of the independent variables vary across the two main dimensions of TNA access.

Figure 6. Marginal effects for Tobit regression of TNA access (index), Model 1

Table 2. Tobit regression of TNA access

Notes: Tobit regression (intreg, STATA 11). Estimations clustered by panel identifier (IO body). Robust standard errors are used to compute Z statistics in all regressions. * p < .05; ** p < .01.

Results

What explains variation in TNA access across IO bodies? We first discuss the findings from Models 1 to 3 for each of the two alternative arguments and the control variables before we report the findings from Models 4 and 5.

The analysis grants only limited support to the argument that IOs have opened up as a result of the spread of a global participatory norm. These results suggest that the findings from case studies of the UN, the EU, and the large multilateral economic organizations do not extend to the broad universe of IOs. The strongest results are found for H1, where the analysis reveals that participatory discourse has a positive and significant statistical effect on TNA access, except for the time before 1990, suggesting that its influence is concentrated to the period after the end of the Cold War. In addition, this variable has a strong marginal effect on TNA access, as shown in Figure 6. However, there are two important limitations to the explanatory power of this variable. First, this factor cannot account for the increasing cross-sectional variation over time. Second, although the time lag reduces the risk of a bias from academic fads and publications by TNAs themselves in the measurement of the discourse, we cannot preclude that the indicator partially represents a broader time trend and the salience of the empirical phenomenon of TNA access.

The analysis provides less support for the other two hypotheses testing the conventional wisdom. The results for un conferences (H2) suggest that the UN has not been a norm entrepreneur because the effect is not significant in any of the three main models. Although these UN events often addressed issues that we nowadays associate with high TNA access such as development, environment, and human rights (Figure 3), UN conferences have not generated today's openness by inspiring IO bodies in related regions or issue areas to adopt participatory arrangements.

The hypothesis that TNA access would be especially high for IO bodies that have been or are at risk of being challenged by civil society actors (H3) receives weak support. The variable protests against io is only significant before 1990. However, protests were extremely rare during this period, so the finding contradicts the theoretical expectation. Descriptive data on this variable show that protests peaked around the year 2000, about a decade after TNA access began to expand strongly, and generally have targeted global, economic IOs. Challenges from civil society actors thus cannot explain the broad opening up of IOs in global governance. In comparison, there is slightly more support for an indirect influence of protest. The variable protests against similar ios has a positive and significant effect on TNA access for the full observation period, even if the marginal effect is relatively weak and the level of significance low. While it is puzzling that this factor is statistically significant before 1990, but not after, the results nevertheless indicate that protests may have led nontargeted IOs to take preventive action. Finally, the variable media coverage is not significant in any of the three models. This suggests that IOs that are more politicized, and therefore more vulnerable to challenges by civil society, are not more likely to open up to TNAs.

The analysis grants extensive support to the argument that functional demand, domestic democracy, and state sovereignty jointly explain TNA access. For two of the three variables measuring functional demand (H4), the results are positive, especially for the time period after 1990. The increase in access over the past two decades has been significantly influenced by the expected benefits from TNA involvement. We find a statistically significant positive effect of local activity on TNA access from 1990 onward, testifying to the attraction of TNA involvement for IO bodies with on-the-ground implementation. The absence of a similar effect for the full observation period is explained by the presence of a negative effect before 1990, when access to IO bodies with local implementation was an exception.

The positive relationship between local implementation and TNA access in recent decades is illustrated by the experience of the ADB. While the ADB's Management, responsible for project implementation, initially did not offer formal access, this body began to open up in the late 1980s, when the ADB shifted its attention from state-led to social development (Figure 2). From then on, TNAs were seen as important partners, because they had “valuable experience and expertise on local conditions and realistic perception of constraints and prospects.”Footnote 74 For instance, TNAs assisted the ADB by promoting community awareness and participation, providing health services and vocational training, and serving as microfinance conduits.Footnote 75 Building on its positive experiences, the Management subsequently expanded openness during the 1990s and 2000s.

Likewise, we find a strong positive and statistically significant effect of noncompliance incentives on TNA access for the full observation period. The marginal effect demonstrates that demand for compliance monitoring is one of the strongest predictors of TNA access. Assessing the time periods before and after 1990 separately, it becomes clear that this effect is particularly strong after 1990. This finding corroborates research that emphasizes functional reasons for private access to a new generation of international courts emerging after the end of the Cold War.Footnote 76 As an illustration, the International Criminal Court—the IO in our sample with the highest access level in 2010—relies extensively on TNAs to monitor compliance. According to Article 44 of the Rome Statute, any organizational body of the ICC, such as the Office of the Prosecutor or judicial chambers, can receive assistance in its work from experts, including from NGOs.

In contrast to the two previous indicators of functional demand, technical complexity is not significant in any of the three index models. This indicates that IOs do not open up to TNAs primarily to benefit from their technical expertise. One explanation could be that IOs instead internalize the solution to this demand through the creation of bodies with specific technical or scientific tasks. In the International Whaling Commission, for instance, the Scientific Committee is composed of member state experts, which reduces the body's demand for external scientific expertise.Footnote 77

H5 on the influence of domestic political regimes receives strong empirical support. level of democracy is positive and significant across all three index models. In addition, it has the strongest positive marginal effect on access among all independent variables. A comparison of different time lags shows higher coefficients for short lags, suggesting a rather rapid effect of domestic democratization on TNA access at the international level.Footnote 78 The OSCE stands out as an example where democratization among member states has led to an extensive expansion of openness (Figure 2). For example, the OSCE's Conference on the Human Dimension (and later Human Dimension Implementation Meeting) opened up to NGOs in the early 1990s, after former Soviet states became new-found proponents of access.Footnote 79

The analysis also offers firm support for the effect of sovereignty costs on TNA access (H6). The variable decision making has a significant negative effect on TNA access before 1990. As shown in Figure 4, even decision-making bodies have begun to open up in recent years, explaining the absence of an effect after 1990 and for the full observation period. In addition, there is a strong statistically significant negative effect for security across all index models. The marginal effect for this variable shows that engagement in security strongly reduces the level of openness of an IO body. Figure 2 illustrates how security bodies, such as the OSCE's FSC, often are the least accessible parts of multi-issue IOs. Similar results are obtained for the UN Security Council and NATO's North Atlantic Council.

Finally, we consider the effects of the control variables. io budget does not have a significant effect in any of the index models. Neither does the analysis grant any support for preference heterogeneity as a constraint on the openness of IO bodies, because affinity of member states is not significant in any of the models. The results for the variable democratic major power reveal an interesting pattern. We find that the presence of a democratic major power in the membership of an IO has a significant positive effect on the openness of its bodies before 1990, but not after. While the relative power of advocates and opponents of TNA access thus mattered before the end of the Cold War, the strong increase in openness since 1990 has not been driven by power differentials. Finally, we conclude that the supply or availability of TNAs does not influence their access to IO bodies. While tna supply has a statistically significant negative effect on access before 1990, this relationship is contrary to the theoretical expectation. Moreover, descriptive data show that the major increase in the worldwide NGO population lagged behind the opening up of IOs, suggesting that participatory arrangements are not the products of NGO demands but instead create opportunity structures and encourage TNAs to mobilize.

Do these results from the composite index hold for the separate dimensions of depth and range of access as well, or are they potentially governed by different logics? With a few exceptions, the results are the same as for our index models and identical across the two dimensions (Models 4 and 5). participatory discourse, noncompliance incentives, level of democracy, and security have a statistically significant effect on both depth and range. Likewise, there is no support in either model for un conferences, protests against io, media coverage, technical complexity, affinity of member states, democratic major power, and tna supply. Yet we observe interesting variation in four instances. First, the variable protests against similar ios has a positive and significant effect on the range of access, but not on the depth, lending some support to the notion that protests have led nontargeted IOs to seek legitimacy through access to a broad range of TNAs. Second, local activity has a positive and significant influence on range but not depth, suggesting that IOs seek input from a broad set of actors when engaged in on-the-ground implementation. Third, decision making has a significant negative effect on the depth of TNA access, but not the range of actors invited. When decision-making bodies grant access, it tends to be shallow, as in the case of the WTO Ministerial Conference. Fourth, io budget has a weak positive significant effect on the depth of access, but not the range. This suggests that IO bodies are more likely to offer deep access when they have sufficient resources to manage the costs of accreditation and participation.

In sum, the multivariate analysis points to strong explanatory power for the three factors of our argument: functional demand for TNA resources and services, the domestic democratic standards of IO memberships, and the sovereignty costs of TNA access. IO bodies are more likely to engage TNAs when involved in policies that require local implementation and monitoring of compliance, and when their member states are committed domestically to principles of liberal democracy, but less likely to invite TNAs where this would entail extensive sovereignty costs. While the effect of domestic democracy has remained strong throughout the entire time period, the effect of functional demand has increased over time, and the effect of sovereignty costs decreased. By contrast, we find less support for the explanation that a global participatory norm has pushed IOs toward greater openness through processes of socialization or organizational legitimation. However, there is some evidence to suggest that the growing strength of a participatory discourse has shaped the over-time trend in TNA access.

Robustness Checks

We also estimated a series of alternative models to check the robustness of our results.Footnote 80 First, we controlled for potential effects of our new index and the Tobit specification, by estimating a logit model with a binary dependent variable that indicates if an IO body is open or not. The results reveal a very similar pattern to those previously reported, with strong support for noncompliance incentives, local activity (after 1990), level of democracy, decision making (before 1990), and security. The same can be observed for democratic major power and, with the same caveat as above, participatory discourse . However, three results diverge. protests against similar ios does not remain statistically significant in this analysis. The effect of io budget is significant, suggesting that IO resources affect the decision to grant access, but not the level of access. We find a strong positive effect of tna supply for the period after 1990, suggesting that the existence of a large NGO population has influenced the likelihood of access, but not its level, during the past two decades.

Second, we estimated a zero-inflated negative binomial regression model. For this purpose, we transformed our dependent variable into a five-scale count variable with values from 0 to 4 to control for potential effects of the Tobit estimation of our index. This specification leads to highly similar results.

Third, we estimated a biased OLS model with fixed-year effects as an additional point of reference. This analysis, too, produced very similar results for the main variables.

Fourth, we controlled for the effects of our decision to operate with IO bodies as the unit of analysis, and re-estimated Models 1, 2, and 3 at the IO level. Although some variables are more difficult to interpret after the aggregation, the analysis corroborates the body-level results on noncompliance incentives (after 1990), level of democracy, decision making, security and, with the same reservation, participatory discourse.

Fifth, we added a series of dummy variables on world regions and policy areas to assess if they have an effect beyond other covariates.Footnote 81 A model that includes only these dummies indicates a significant negative effect on access for africa, asia, finance and security, as well as a positive effect of human rights. However, adding these dummies to Model 1 does not affect the principal results. The significance of the regional dummies disappears, since they are correlated with the level of democracy. The effect of IO bodies involved in finance, security, and human rights decreases, but remains significant, pointing to the existence of issue-specific determinants of TNA access beyond the general mechanisms in the core model.

Taken together, these additional tests suggest that the principal results from the Tobit analysis are robust regarding the influence of functional demand, domestic democracy, and sovereignty concerns.

Conclusion

The opening up of IOs to TNAs is one of the most profound changes in global governance in recent decades. This article contributes to our understanding of this development by descriptively mapping central patterns in TNA access since 1950 and assessing the sources of variation through a multivariate analysis. Our conclusion briefly summarizes the findings of the analysis and expands on their implications for the study of global governance.

Our argument can be summarized in terms of three principal conclusions. First, IOs have indeed undergone a profound institutional transformation over past decades, dramatically expanding the opportunities for TNAs to participate in global policymaking. If anything, our exclusive focus on formal TNA access underestimates this change, because many IOs offer informal mechanisms of access as well. This is a development that spans all issue areas, policy functions, and world regions. Still, significant differences remain as TNA access continues to vary in distinct and durable ways. Second, variation in TNA access is best explained by a combination of three principal factors. The functional advantages of including TNAs account for a central part of the expansion of access over time, as international cooperation has shifted toward more demanding governance problems, and for variation across issue areas and policy functions, both across and within IOs. The level of domestic democracy in the membership of IOs is an important additional source of growing openness and helps to explain variation across IOs and world regions as a result of democratization. The principal constraint on the expansion of TNA access has been the sovereignty costs to states, which have contributed to variation across issue areas and policy functions. Together, these factors yield a two-stage account of the opening up of IOs, with the end of the Cold War acting as a dividing event and catalyst for change. Third, the tendency of existing research to focus on developments in a specific set of major IOs has biased the understanding of TNA access. While many prominent contributions have concluded that IOs open up as a result of a participatory norm, an assessment of a broad sample of IOs for an extended period of time yields different results. What was claimed to be a general phenomenon constituted a relatively rare occurrence, primarily influencing TNA access in a select number of large regional or global IOs.

Expanding the perspective beyond its results on TNA access, this article generates implications for three areas of research on global governance. The first is the literature on international institutional design. Existing research tends to highlight the reasons IOs are resistant to change. Changing the constitutional rules of IOs invariably involves demanding institutional hurdles.Footnote 82 The capacity of IO bodies to implement institutional changes on their own is normally circumscribed by states' interest in matching delegation with control.Footnote 83 The organizational cultures of IOs often have a stabilizing effect by defining appropriate institutional practices.Footnote 84 Once in place, institutional rules tend to become self-reinforcing by structuring expectations, presenting adaptation costs, and generating positive feedback effects.Footnote 85 Yet, rather than stability, we observe profound change in the transnational design of IOs, suggesting that IOs are more amenable to reform than existing research assumes.

Our results also underline the necessity of comparative analyses. To date, most research on the design of IOs focuses on one or a limited number of IOs. As Koremenos notes, “we have lots of information about how certain variables operate in specific cases but little information about how those variables operate over the range of cases that international cooperation presents.”Footnote 86 As illustrated by our findings, this approach carries a high likelihood of biased generalizations. Students of international institutional design are therefore well-advised to explore designs that allow us to better capture general dynamics in global governance.

A second area of research for which this article carries implications is the literature on TNA influence in global governance.Footnote 87 Institutional access is frequently identified as a central determinant of TNA influence.Footnote 88 Truman, in his seminal work on interest groups, even regards it as a precondition, arguing that “power of any kind cannot be reached by a political interest group, or its leaders, without access to one or more key points of decision in the government.”Footnote 89 Rather than having to rely primarily on public-opinion mobilization and informal lobbying, TNAs with access to policy-making can employ a broader, and potentially more effective, portfolio of resources and strategies. With access, TNA get more opportunities to provide information, argue for their positions, shape implementation, and hold states to their commitments.

Our findings suggest that the institutional preconditions for TNA influence have improved dramatically over time, and are particularly favorable in policy fields such as human rights, development, and environment, and at the stages of policy formulation, implementation, and monitoring and enforcement. These findings can help to explain why existing research often identifies TNA influence in the formulation of environmental policy and the monitoring of human rights.Footnote 90 Nevertheless, we should not assume that access and influence have a linear relationship. Access may not be sufficient by itself or reflect a genuine IO interest in TNA input. Teasing out the conditionality of institutional access as an explanation of TNA influence is an important task for future research.

A third area of research for which this article has important consequences is the normative debate on democracy in global governance. The democratic legitimacy of global governance has occupied many researchers over the past two decades.Footnote 91 One influential line of theorizing highlights the potential for a democratization of global governance through more involvement of civil society. According to this notion, varyingly referred to as global stakeholder democracy, transnational democracy, and democratic polycentrism, TNAs can function as a “transmission belt” between the global citizenry and IOs, whose organized inclusion furthers democratic values such as participation, accountability, and transparency.Footnote 92

Our results on TNA access speak to the empirical viability of this normative vision and yield a mixed verdict. The opening up of IOs to TNAs is likely to be good news for advocates of global stakeholder democracy because access may provide channels of citizen participation, introduce mechanisms of external accountability, and improve transparency. At the same time, a set of enduring limitations in TNA involvement may be cause for pessimism. When IOs open up, they are typically selective in terms of which TNAs they invite. Some policy areas still remain nearly closed, and the opportunities for TNA involvement are least extensive at the democratically most central stage of international cooperation—decision making. These patterns suggest that challenges remain, even if the institutional preconditions for a civil-society-based democratization of global governance have improved in recent decades.

Supplementary material

Replication data are available at http://dx.doi.org/S0020818314000149.