Child abuse is a pervasive global challenge affecting all children, irrespective of age, sex, race, religion, or ability. The World Health Organization (1999) defines it as

all forms of physical and/or emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse, neglect or negligent treatment or commercial or other exploitation, resulting in actual or potential harm to the child’s health, survival, development or dignity in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust or power. (p. 15)

Children with developmental disabilities (e.g., cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, autism spectrum disorder) are 3 to 5 times more likely to be victims of abuse than their typically developing peers (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Bellis, Wood, Hughes, McCoy, Eckley and Officer2012) and are overrepresented in involvement with child protection services for all kinds of abuse (Dion, Paquette, Tremblay, Collin-Vézina, & Chabot, Reference Dion, Paquette, Tremblay, Collin-Vézina and Chabot2018). They are also more likely to be victims of more serious and more frequent sexual abuse (Soylu, Alpaslan, Ayaz, Esenyel, & Oruç, Reference Soylu, Alpaslan, Ayaz, Esenyel and Oruç2013).

These children may also experience complex communication needs, which manifest as difficulties with producing and/or understanding spoken language. Although no large epidemiological studies have been conducted on children with complex communication needs, smaller studies suggest that they are particularly vulnerable, as they cannot rely on traditional communication modes such as speech for help (Devries et al., Reference Devries, Kuper, Knight, Allen, Kyegombe, Banks and Naker2018). Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) offers many of these children an effective way of interaction, which could include disclosing abuse. AAC includes all forms of communication that are used to express and complement expression of thoughts, emotions, and needs (Beukelman & Light, Reference Beukelman and Light2020). It can also be used to enhance understanding (i.e., strengthening receptive language) and for creating structure (e.g., when using visual schedules). Many children with complex communication needs are students in special schools (also known as ‘schools for specific purposes’ or ‘specialised schools’). The definition of special schools differs between countries, but in this study special schools refer to segregated schools — that can be situated on the same premises as mainstream schools — specifically for children with intellectual disabilities.

Abuse prevention is an important strategy to decrease child abuse (World Health Organization, 2016). However, there appears to be a lack of research on school-based abuse prevention programs that address different types of abuse aimed at both children with and without disabilities. All children need access to appropriate, accurate, and accessible information that is informed by evidence about life skills, rights, specific risks (e.g., the internet and social media), and self-protection (e.g., developing positive peer relationships; Mikton Butchart, Dahlberg, & Krug, Reference Mikton, Butchart, Dahlberg and Krug2016; UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2011). Abuse prevention programs should thus be developed to suit the needs of all children, regardless of (dis)abilities, by employing the seven universal design principles, namely equitable use, flexibility in use, simple and intuitive use, perceptible information, tolerance for error, low physical effort, and size and space for use (Johnson & Muzata, Reference Johnson, Muzata and Banja2019).

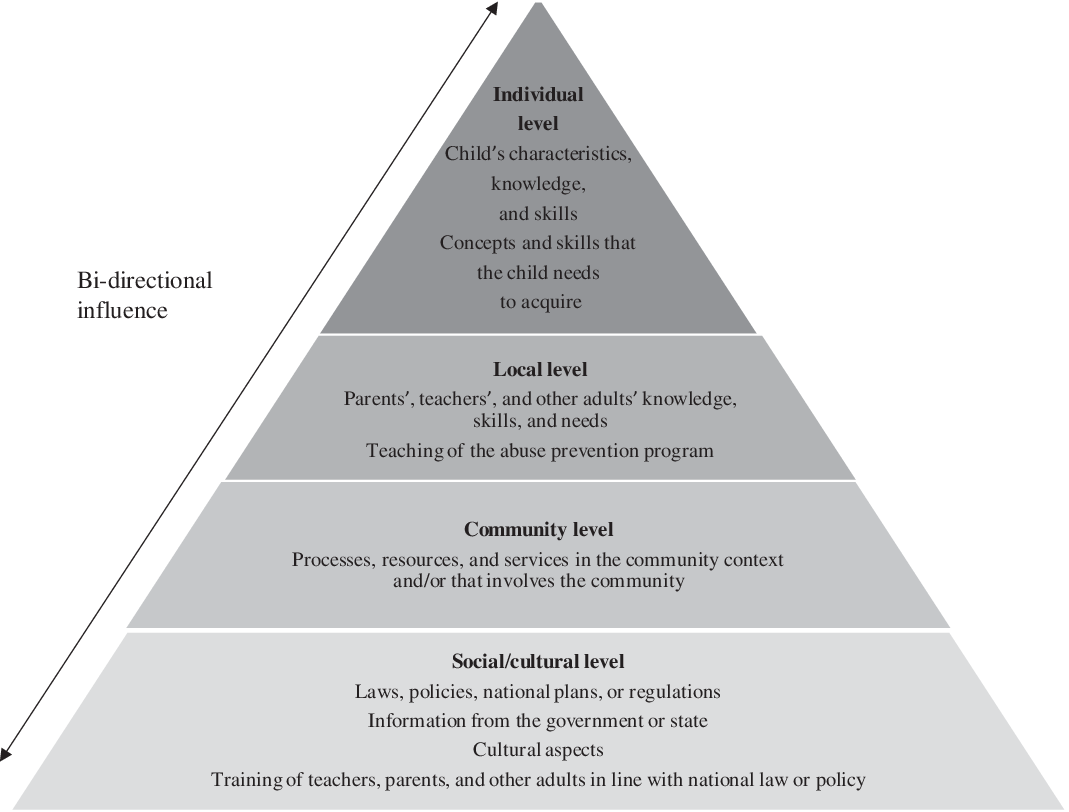

The behavioural ecological model (BEM) holds promise for unpacking what a school-based prevention program should entail. It states that physiological responses can be learned (respondent conditioning) and can be reinforced or extinguished depending on contingencies of past responses (operant conditioning). Furthermore, it explains that learning occurs in a social context where the person, environment, and behaviour interact and influence each other (social cognitive theory; Hovell, Wahlgren, & Adams, Reference Hovell, Wahlgren, Adams, DiClemente, Crosby and Kegler2009). The BEM assumes that behaviour is shaped through four levels of influence (individual, local, community, and social/cultural level) that interact (see Figure 1). It has been used successfully for developing health promotion interventions and has also been adapted for public health research relating to tobacco use (Rovniak, Johnson-Kozlow, & Hovell, Reference Rovniak, Johnson-Kozlow and Hovell2006), research on sustainability practices of universities (Brennan, Binney, Hall, & Hall, Reference Brennan, Binney, Hall and Hall2015), and in developing anti-bullying school-based interventions (Dresler-Hawke & Whitehead, Reference Dresler-Hawke and Whitehead2009). In the latter study, the importance of involvement of individuals and institutions from all levels of the model is emphasised in order to decrease bullying (Dresler-Hawke & Whitehead, Reference Dresler-Hawke and Whitehead2009). These principles can also be assumed for abuse prevention, which is similar to bullying in that it includes emotional or physical abuse. Therefore, the BEM could provide a framework for the current study.

Figure 1. The Behavioural Ecological Model for School-Based Abuse Prevention Programs. Adapted from ‘The Behavioral Ecological Model: Integrating Public Health and Behavioural Science’, by M. F. Hovell, D. R. Wahlgren, and C. A. Gehrman, in R. J. DiClemente, R. A. Crosby, & M. C. Kegler (Eds.), Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research: Strategies for Improving Public Health (pp. 347–385), 2002, San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Copyright 2002 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Adapted with permission.

On the one hand, there is a paucity of abuse prevention programs that have been developed for children with disabilities (Nyberg, Ferm, & Bornman, Reference Nyberg, Ferm and Bornman2021). On the other hand, established abuse prevention programs developed for children without disabilities, such as Staying Safe with Emmy and Friends (Dale et al., Reference Dale, Shanley, Zimmer-Gembeck, Lines, Pickering and White2016; White et al., Reference White, Shanley, Zimmer-Gembeck, Walsh, Hawkins, Lines and Webb2018), are not adapted to the specific needs of children with communicative and/or intellectual disabilities. Furthermore, the specific components taught in these programs might differ according to the child’s (dis)ability and specific needs. For example, children who are in a wheelchair may be more exposed to potentially abusive situations while visiting the bathroom or showering, whereas children with challenging behaviour might be exposed to abuse as a response to their own problem behaviour. Not only have abuse prevention programs specifically aimed at children with disabilities thus been underresearched, but also research on adapting existing programs to better fit the needs of children with communicative and/or intellectual disabilities is scant.

The aim of this study is therefore to explore the views of three stakeholder groups, namely teachers in special education, practitioners working with children with disabilities who had been victims of abuse, and parents of children with communicative and/or intellectual disabilities, regarding the key components and methods they considered as important for consideration when developing a school-based abuse prevention program.

Materials and Methods

Research Design

A qualitative approach was used to obtain in-depth information on the development of a school-based abuse prevention program for children with communicative and/or intellectual disabilities. Two focus groups and six semistructured interviews were conducted.

Participants

Three different stakeholder groups were included: Group 1 (teachers working in special education with children 7–12 years of age); Group 2 (practitioners experienced in working with children with disabilities who had been victims of violence, such as child investigators, nurses, and psychologists); and Group 3 (six parents of children with communicative and/or intellectual disabilities 7–12 years of age), described in Table 1. Parents participated in one-on-one interviews, rather than focus groups, due to the ethical implications of discussing abuse in a group setting.

Table 1. Participant Description

Data Collection

Before recruiting participants to the study, ethics permission was obtained through the ethical vetting board at Gothenburg University.

Focus groups with teachers and practitioners

The focus group with seven teachers (Group 1) was conducted at a central, convenient location for the participants. All had been recruited through a post on the Facebook page of a centre for AAC and assistive technology. All participants received written information about the study after expressing initial interest to participate. They completed a consent form and a biographical questionnaire before the focus group started. The first author acted as the moderator for the focus group. A research assistant was responsible for note-taking and summarised the discussion at the end to ensure the accuracy of the notes and to facilitate member checking.

The focus group with the practitioners (Group 2) was conducted at a venue where most of them worked. They were recruited using a snowball technique, and after the initial contact was made, they received written information about the study. Group 2 participants signed informed consent forms and completed biographical questionnaires before the focus group commenced. Despite their different professional backgrounds, they were co-workers and thus knew each other. Once again, the first author was the moderator of the group and she was assisted by a research assistant.

Both focus groups 1 and 2 used the same interview guide to ensure comparability and increase procedural integrity. The following five questions were asked:

-

1. What experiences do you have of children with disabilities who have been victims of abuse?

-

2. If you were to design a program for children with communicative and/or intellectual disabilities aimed at preventing abuse, what would you include?

-

3. Which questions are important to ask during the evaluation of the program?

-

4. In your opinion, what is the key element/most important element in an abuse prevention program for children with communicative and/or intellectual disabilities?

-

5. Which difficulties with implementing an abuse prevention program do you foresee?

The focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by the first author. The transcriptions were checked and corrected for accuracy by the third author.

Semistructured interviews with parents

Six semistructured interviews were conducted with parents (Group 3), at a location they chose, using an interview guide that started with the initial five questions included in the focus groups. A further five questions were added after reviewing focus group results, namely:

-

1. Do you think that parents want to know more about child abuse and abuse prevention programs?

-

2. How can parents be involved in an abuse prevention program at school?

-

3. What is important to consider when teaching children with communicative and/or intellectual disabilities about abuse?

-

4. In your opinion, how could the program be adapted for children with different disabilities?

-

5. How can you retain the children’s knowledge about abuse that they received during the program?

The interviews were audio-recorded.

Data Analysis

The data from the three stakeholder groups were collapsed to form one corpus, which was analysed with qualitative data analysis software, namely ATLAS.ti 8 (Windows Version 8.4; ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, 2020). Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six steps for thematic analysis was employed, namely (a) familiarisation with the data by reading and rereading the transcripts; (b) generating initial codes; (c) searching for themes; (d) reviewing themes and codes through recoding and refinement; (e) defining and naming themes; and (f) constructing a code book with themes, codes, and definitions of the codes. The code book included four main themes, namely teaching methods and components (with 27 different codes), implementation (with 14 different codes), difficulties (with 19 different codes), and evaluation (with 10 different codes). The coding was validated by the second author, who subsequently reviewed 20% of the data. She was blinded to the code assigned but had knowledge of the theme to provide context. Interrater reliability of 78% was achieved after the review. After a consensus discussion, full agreement was achieved. Each code was reviewed and plotted onto a level of the BEM framework.

Findings

The findings are presented according to the four levels of the BEM. The themes and codes linked to each level of the BEM are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Themes and Codes Related to the Different Levels of the Behavioural Ecological Model

Social/Cultural Level

The social/cultural level of the BEM refers to laws, policies, national plans, or regulations, information from the government or state, cultural aspects, and training of teachers, parents, and other adults. Four themes were related to this level, namely teaching methods and components, implementation, difficulties, and evaluation (Table 2).

Eleven codes linked to teaching methods and components were delineated on the social/cultural level. These were (a) involve parents, (b) use videos, (c) use role-play, (d) use case studies, (e) train face to face, (f) adapt training material for children, (g) knowledge: types and signs of abuse related to teaching, (h) knowledge: disability and treatment, (i) knowledge: how to report, (j) create opportunities to practise skills, and (k) address attitudes. All three stakeholder groups reiterated the importance of involving parents in abuse prevention programs. Videos and role-play were suggested teaching methods, as was the use of case studies to facilitate discussion: ‘Well, when we worked with the case studies, there was really good discussions and it’s an angle of approach that doesn’t single out anyone’. Some participants preferred face-to-face training over online methods. They also suggested that the training material (including a training manual) should be in an accessible format for children so that the adults would not need to adapt it themselves. Regarding the content, participants suggested that the overall aim of abuse prevention training should be to increase the adults’ general knowledge of both abuse and disability, and the intersection of the two:

To make it visible earlier on a group level, because then it might be easier if you see that one of your children’s friends are being treated badly or is not doing well, or it might be easier to do something about that if there is a focus on it. For everybody.

Adults need to know about different types of abuse and how to identify possible signs of abuse, as this can be especially difficult with children with communicative and intellectual disabilities: ‘But it is really hard to tell, so therefore a lot of the children who are victims of abuse are not detected’. Participants discussed being trained on how to report suspected abuse: ‘One shouldn’t be put in a position where you ask the questions [about abuse] and don’t really know, what do I do with this?’ Knowing about available treatment options was also discussed. Participants also identified the attitude towards disabilities and abuse component and that it should be included in training. Opportunities should also be created for using the skills acquired during training.

Two codes related to implementation emerged: (a) ensure parental support and (b) make mandatory. Parental support as a critical element of successful implementation of the abuse prevention program was underscored, as children with disabilities sometimes exhibit challenging behaviour that increases the caregiving burden, which might in turn act as a trigger for abuse:

Describing that it is normal to feel frustration as a parent. And despair, sadness and anger — anger is contagious. Talking about these feelings. If you have a child with behaviour issues then that is extremely challenging parenting. Without talking about the child as being difficult, but rather talking about challenging parenting instead.

Some participants thought that the program needed to be mandatory (e.g., included in the school plans and regulations).

Five codes linked to difficulties related to the social/cultural level were identified: (a) lack of knowledge: abuse, (b) lack of knowledge: disability, (c) cultural aspects, (d) (over)protecting children, and (e) child’s rights. The lack of knowledge (related to disability and to abuse) was discussed at length, as highlighted by a practitioner: ‘I think overall that when we are addressing schools, teachers sometimes have alarmingly little knowledge about abused children’. Some participants said that the rights of children with disabilities should be known and respected by society, but that is not always the case. Participants also discussed the risk of over-protecting adolescents with disabilities by denying them access to alcohol, romantic partners, or the broad freedoms enjoyed by their peers without disabilities:

One difficulty is when do you start to talk about what? Age-wise, when is a student mature enough to start to talk about sexual abuse? I think that’s really difficult with our students, when they get to puberty. So, you don’t kind of start something that can turn out wrong. To know when do I start talking about this. They aren’t really the age that they are.

Some participants also highlighted cultural aspects related to disability and abuse as potential difficulties that trainers should be aware of.

Only one code relating to evaluation was linked to this level, namely the need to employ different evaluation methods that are adapted for all children:

It’s an extensive task, it’s not just sitting down with a questionnaire, that’s not possible. But it’s rather observations over time, and then to capture the correct results.

Methods such as Talking Mats (Murphy & Cameron, Reference Murphy and Cameron2008) were mentioned, as well as using interviews or questions before and after the implementation of the program.

Community Level

The community level refers to processes, resources, and services in the community context and/or that involves the community. Three different themes — implementation, difficulties, and evaluation — were related to this level, as shown in Table 2.

Five implementation codes were delineated, namely (a) dedicated budget, (b) shared values, (c) collaboration, (d) adaptation of context, and (e) community relevance. First, the importance of a dedicated budget for the implementation of the program was discussed. Sharing the same values in terms of rights of individuals with disabilities and what constitutes abuse was suggested as an important factor. Schools, parents, and therapeutic and other services need to collaborate and share important information: ‘There has to be communication between the home and the school. Because these children have especially big difficulties to understand that there can be different rules in different places’. The context where the program is implemented (e.g., school) needs to be adapted to meet all children’s needs. The context can also facilitate knowledge and understanding: ‘The child will be dependent on the knowledge in a given context’. Participants also discussed that the program ought to be relevant for the community at large.

Only one code, social services, related to difficulties was reported at the community level. Participants identified social services practitioners as important collaborators, while also noting their lack of knowledge regarding how to communicate with children with communicative and/or intellectual disabilities (‘We did contact social services to consult them, but they didn’t have any knowledge whatsoever’) as well as a lack of transparency in the processes and actions of social services (‘We talked quite a lot about this issue with the confidentiality, that it could be … well it makes it difficult sometimes’).

Evaluation yielded two codes aligned to this level, namely (a) using disclosure as an outcome measure (e.g., disclosing to the school nurse), and (b) using abuse as an outcome measure (e.g., using the number of reports made to social services, the number of police reports, or the number of police investigations that go to court).

Local Level

The local level includes the knowledge, skills, and need for training for parents, teachers, and other adults as well as the actual teaching of the abuse prevention program. The codes related to this level belonged to all four themes: teaching methods and components, implementation, difficulties, and evaluation (see Table 2).

Seven codes relating to teaching methods for children with disabilities were linked to this level: (a) use play, (b) use stories, (c) use videos, (d) use role-play, (e) check comprehension, (f) listen and believe, and (g) include AAC methods. Play and stories were described as methods for ensuring understanding of key components, as well as using videos and role-play:

I’m thinking that you would need to replay things, kind of. Either using role-play, or dolls or something. That you create something other than just … well of course teach, but also something more experience based, I think, is needed.

Evaluating the children’s comprehension was suggested to ensure that they grasped the intended information. Participants also discussed that adults should listen to and believe children when they speak out:

I’m also thinking about this thing that we discussed quite a lot when we did our questionnaires, which is feedback to the student. I have listened to you, I understand you, I want to help you.

Finally, different AAC methods (e.g., Talking Mats, communication boards, and manual signs) were seen as crucial to enable children with communicative and/or intellectual disabilities to understand the key components taught in the program. The need for AAC customisation for individual children was also mentioned.

Four codes relating to implementation were identified, namely (a) who teaches? (b) support from management, (c) adaptations: teaching methods, and (d) adaptations: teaching material. Participants discussed that the program trainer should be somebody with appropriate skills whom the children trust. The teachers especially highlighted that teachers need support from principals and the school management to enable them to implement the program. Furthermore, participants felt strongly that the program should be adapted to children with communicative and/or intellectual disabilities. This adaptation needs to be done in terms of the methods used in the program (e.g., how questions are asked, how information is provided, and in what group setting it is taught). Moreover, these adaptations should be done for individual children and for the group: ‘I can imagine that some might find it difficult to deal with it in a group and for some it’ll be an advantage to do it in a group’. The program also needs to be adapted in terms of the materials used (e.g., using pictures and AAC methods to enhance understanding). Participants suggested using a basic manual to start, which could then be adapted for individual children.

Seven codes related to difficulties were mentioned. These were (a) bulldozing, (b) staff resistance, (c) time constraints, (d) fear: adults, (e) despair: parents, (f) concern: effect of training, and (e) decision-making: teachers. ‘Bulldozing’ entails violating children’s rights and not respecting children when they say no; for example, if a child does not want to participate in certain compulsory school activities and says no, it could create a potentially problematic situation in terms of respecting the child’s decision. Some children are more inclined to respond with a ‘no’ to any inquiry that involves something unfamiliar:

I feel like we need to include the concept of ‘I don’t want to’. I mean we work a lot with that … how do I put this. We’re struggling to get our students to try things, and then they can say, ‘I don’t want to’, but we still drag them along to things.

Also discussed as a potential difficulty was resistance from staff to implement the abuse prevention program due to different reasons (e.g., lack of knowledge or resources, time constraints, fear):

One thing I’ve been struck by over the years, is that one quite often meet staff at schools and preschools that are too afraid to report [abuse] or to take it further and discuss the matter even though they’ve seen indications of abuse. Today, we are starting to give better information and education to them also. But it’s so easy for them to say, ‘I don’t want to be that child’s safe person because imagine if I have to stand and talk to that angry dad later’. And then you have to talk to that person from our perspective and say that, well, the child is going home to that dad, you can choose not to do that.

Abuse can stem from a sense of despair that parents can experience when dealing with children with challenging behaviour, as described by a police officer:

I often meet children with different kinds of neuropsychiatric disabilities. And when you talk to those parents, they often say that they kind of snapped …. They’ve coped with so much and then they ran out of energy. Patience, energy, perseverance, everything ran out. And then, then there was only violence left.

Parents’ willingness to allow their child to participate in a prevention program is affected by their being concerned that their child might be abused or traumatised when participating in an abuse prevention program. One parent mentioned that teachers need to be in charge in their classrooms and make decisions and rules without having to consider parental preferences.

Five codes relating to evaluation were delineated, namely (a) expert panel review, (b) view adults’ role, (c) view multiple role-players, (iv) consider context, and (v) did it work? The code ‘Did it work?’ refers to evaluating whether the abuse prevention was effective (i.e., did it produce the desired outcomes) without suggesting any method. Adults’ understanding of their responsibility and the need for adaptations, such as using AAC, was suggested by a parent as an important aspect to evaluate. Evaluating the effect of the program by asking about the context was also suggested: ‘I think what could also be evaluated is the environment at the school. Is the school calmer after the program?’ Participants thought that it was important to ask questions to children, to parents, and to teachers when evaluating the program. One participant suggested that a first version of the program could be reviewed by an expert panel to verify the contents and methods of the program.

Individual Level

The individual level refers to the child’s characteristics, knowledge, and skills, as well as concepts and skills that need to be acquired. The codes that were related to the individual level came from four different themes: teaching methods and components, implementation, difficulties, and evaluation, as shown in Table 2.

Key components refer to the concepts that should be taught to children with communicative and/or intellectual disabilities as part of the program. Eleven codes were identified, namely (a) empowerment and children’s rights, (b) distinguish wrong/right, (c) identify and name abuse, (d) say ‘no’, (e) identify dangerous situations, (f) unmask deceitful behaviour, (g) disclose abuse, (h) understand sexuality, (i) show integrity, (j) understand and identify emotions, and (k) understand behavioural consequences. Empowering children by teaching them about their rights and learning what is right and wrong were highlighted in all three groups: ‘But my idea with this kind of [abuse prevention] program is also to help children with disabilities to have agency in their own wellbeing in some way’. Participants also suggested that children’s rights could be linked to the Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations, 1989).

The need for children with communicative and/or intellectual disabilities to be able to speak up about abuse, to understand what constitutes abuse and know how to say no, to learn about specific situations that could be associated with risk (such as being alone in a taxi with a taxi driver), as well as unmasking deceitful behaviour (such as adults posing as children online) were discussed in all groups. Disclosing abuse could present some challenges. A parent said,

We need to strengthen children from within, so that they dare to talk about it. And give the right prerequisites. If that child has had a different experience or has difficulties with expressing themselves, then we need to face that at the same time.

Children with communicative and/or intellectual disabilities also need to be taught about sexuality, integrity, feelings, and how their behaviour affects others. One practitioner had experienced the consequences of a lack of teaching young adults with intellectual disabilities about sexuality:

It was kind of a topic that was just left there … and at the same time everybody was … well … aware that many of them had sexual relationships. This concept of, what are we protecting them from, and not? Should you protect children, or adults, from their own sexuality? That doesn’t turn out well.

Three codes relating to implementation were identified, namely (a) retaining knowledge, (b) screening, and (c) adaptation of program to different disabilities. Retaining the knowledge gained from participation in the abuse prevention program was thought to be done mainly by repetition: ‘Repeating the information many times’; ‘Continuously as the child ages it changes and then you need to carry on. It is not like it is a one-time event’. The idea of screening children for experience of abuse while offering the abuse prevention program at the same time was mentioned by one participant. Adapting the program to children’s (dis)abilities was seen as essential to enable as many children as possible to participate and benefit from the program. However, some participants also saw this as the greatest potential challenge to the successful implementation of the program. A teacher explained, ‘I still think [the biggest challenge] is getting through to all groups of students. The ones who have the most difficulties and have severe intellectual disabilities’. Some participants proposed solutions for this, such as,

I think it would be good to have a class that is put together depending on the difficulties. And then you need sort of a toolbox with different exercises, and then you can use the ones that fit for this particular group.

Seven codes relating to difficulties were noted: (a) communication and cognitive challenges, (b) poor generalisation skills, (c) disclosure/failure to disclose, (d) docility, (e) dependency, (f) (re)traumatisation, and (g) challenging behaviour. Challenges related to communication and intellectual difficulties were frequently discussed and concerns were raised in terms of both general understanding and understanding specific concepts such as abuse and the ability to express themselves. One teacher said, ‘It is really us who control the words that they can give us, because we might not give them these words or objects to talk about’. A parent expressed concern about their child’s ability to disclose abuse: ‘To express something by herself about what she experienced, I don’t think that she could do that’. Generalisation of concepts was described as difficult for children with communicative and intellectual disabilities, and participants expressed concerns about how to compensate for that in abuse prevention: ‘It might be OK for Mum and Dad to do something, but it might not be OK if school staff does roughly the same thing, or something that can be perceived as the same thing’. Difficulties related to communication and cognition were also linked to disclosure, including both actual disclosure and failure to disclose. The participants envisaged potential problems related to disclosure in terms of having access to the appropriate vocabulary and also who to disclose to and at what time:

And they [children with communication difficulties] don’t come to the police either, because they haven’t been able to disclose about abuse or vulnerability from the beginning, to anyone around them. In situations where, for example, the person that you could disclose to, like an assistant or something like that, if that person is the abuser … then it becomes difficult.

Docility refers to children with communicative and/or intellectual disabilities answering questions in the way they think the person asking the question wants them to answer rather than telling the truth. Many children with disabilities are dependent on caregivers and staff for many areas of daily life. This could affect their ability to disclose abuse, to say no to risky situations or actual abuse, and to remove themselves from the abuser:

I’m thinking dependency on usually a lot of different persons and that can be a lifelong dependency in many ways. Maybe not on the level that you need help in every situation, with dressing and so on, but to get a functioning home situation when you start to become an adult, to gain some more freedom … this differs so much when you might not have the prerequisites yourself to live it.

Traumatisation or re-traumatisation was a risk linked to the abuse prevention program, as alluded to by some participants. Talking about abuse, naming abuse, and speaking about sexuality and integrity creates a potential risk that some children will be affected, especially if they have previously been victims of abuse, a fact which might not be known:

There’s also a risk, I think, to scare children from intimacy. You need to think about how you talk about sexual abuse and consent. That at the core intimacy and physical closeness is something nice and cosy. I think that adults talk about it in a way that it almost scares children away from that. We shouldn’t do that. But rather teach the children how it [intimacy] can be safe.

Challenging behaviour in children with communicative and/or intellectual disabilities were discussed by several participants in terms of the difficulties related to this when implementing an abuse prevention program:

I can’t demand from him that he should totally know what is right and wrong in all situations. He has, for example, shoplifted. It is very wrong. You can’t do that. He knows that. But he doesn’t know that when he is doing it. Because he forgets it.

Two codes belonging to the evaluation construct were noted: (a) children understanding key components (receptive) and (b) children using key components (expressive). Children’s understanding of the topic was suggested as a possible way to evaluate the effectiveness of the program: ‘I think you need to ask the children what they learned. So, some sort of evaluation with the children’.

Discussion

Our study shows the depth and complexity of developing and implementing a school-based abuse prevention program for children with communicative and/or intellectual disabilities. These children are particularly vulnerable to abuse and need to be involved in abuse prevention themselves. Furthermore, the involvement of parents and teachers was also reported as being crucial to ensure successful implementation. The number of focus groups and interviews were limited, as well as the number of participants. The results presented in the study should be viewed as preliminary and an addition to the limited knowledge base on school-based abuse prevention programs for children with disabilities.

The adapted version of the BEM employed in this study is proposed as a valid framework for developing school-based abuse prevention programs. The analysis of the present study’s data reveals that the findings are assigned to all the levels of the BEM.

The results linked to the social/cultural level were mainly related to teaching adults about abuse and identifying signs of abuse in order to provide support to children and prevent abuse and neglect. A general lack of knowledge of abuse was raised as a concern, which is consistent with a Swedish report that showed that 35% of universities did not include child abuse in teacher training for younger children, and that the existing training was limited (Inkinen, Reference Inkinen2015). Noticing signs of abuse in children with disabilities can be challenging as some of the common signs of abuse or neglect might not be relevant for children with disabilities (e.g., changes in behaviour or frequent absence from school). These behaviours might be linked to the child’s disability and not abuse. Drawing from the results of the present study, describing the signs of abuse children with disabilities exhibit is needed, but to our knowledge, no tool currently exists for this purpose.

Beyond identifying and describing abuse, teachers also need to feel confident in reporting abuse. Most child abuse and neglect is never reported, as demonstrated by the discrepancy between the number of reports to child protection services versus the frequency of abuse found in surveys distributed to adults and children (Gilbert et al., Reference Gilbert, Kemp, Thoburn, Sidebotham, Radford, Glaser and MacMillan2009). In a study in Sweden of general practitioners, 20% had suspected child abuse but not reported it despite mandatory reporting laws (Talsma, Bengtsson Boström, & Östberg, Reference Talsma, Bengtsson Boström and Östberg2015). The underlying reasons for lack of reporting can include limited knowledge about the signs of abuse, routines for reporting, as well as fears about damaging the relationship with the family.

Supporting parents of children with communicative and/or intellectual disabilities to navigate some of the challenges of parenting a child with a disability was highlighted. Parents and other familiar caregivers are often the main perpetrators of child abuse and neglect (Hurren et al., Reference Hurren, Thompson, Jenkins, Chrzanowski, Allard and Stewart2018; Stöckl, Dekel, Morris-Gehring, Watts, & Abrahams, Reference Stöckl, Dekel, Morris-Gehring, Watts and Abrahams2017), emphasising that parental support to cope with the increased caregiving burden of children with disabilities should never be underestimated. Parenting programs to decrease abuse have been found to have moderate yet significant effectiveness on reccurrence of child abuse and should therefore be considered in situations of known abuse (Vlahovicova, Melendez-Torres, Leijten, Knerr, & Gardner, Reference Vlahovicova, Melendez-Torres, Leijten, Knerr and Gardner2017).

Despite relatively few themes linked to the community level in our study, the involvement of the community in abuse prevention is important. The community’s role becomes evident in the concept of shared values of rights and risks for all children, including children with disabilities. Shared values can be achieved through training both teachers and parents to ensure that both groups receive the same information. Collaboration is also important for children, as they benefit from consistency in the information given and the attitudes towards abuse among the important adults in their lives.

Social services are an important collaborator for both schools and families, and the difficulties described by the teachers in the present study in relation to social services are troubling. A lack of written policy on how to serve children with disabilities could contribute to each case being handled on an individual basis, which could influence the quality and consistency of the service negatively (Lightfoot & LaLiberte, Reference Lightfoot and LaLiberte2006). Furthermore, social workers’ knowledge of disability and AAC may be limited.

Unintentional abuse can stem from trying to convince children to do things they don’t want to do, or to challenge them to push beyond their capability. Respecting their rights and opinions, while at the same time making sure that they participate in activities, needs to be discussed within the scope of an abuse prevention program. Lack of information to teachers and parents can create challenges, such as parents not wanting their child to participate in the abuse prevention program or teachers being reluctant to teach the program.

Research has highlighted active participation by children as a vital component in school-based abuse prevention (Brassard & Fiorvanti, Reference Brassard and Fiorvanti2015). Interactive teaching methods such as role-play, videos, and discussions could potentially increase understanding and facilitate learning in children with communicative and/or intellectual disabilities and make the program accessible and appealing to them. Video modelling has also been used effectively to teach children with various disabilities about social skills (Gül, Reference Gül2016) and could likewise be used to teach abuse prevention. The use of AAC materials, in particular pictorial support, based on universal design principles, will ensure that the program is accessible for all children. Furthermore, learning also depends on the person teaching the program, their knowledge of the children, and their ability to adapt the program. The teacher’s skill and experience are thus crucial in the adaptation process.

The complexity of learning, understanding, and being able to express oneself as a child with communicative and/or intellectual disabilities was discussed in depth. The main message from these discussions was the need for adaptation to meet the individual child’s needs, using universal design principles (Johnson & Muzata, Reference Johnson, Muzata and Banja2019). Flexibility, also a universal design principle, emphasises that programs ought to have room and suggestions for adaptations for children with different skills, as outlined earlier. Likewise, the principle of perceptible information was addressed by the participants in terms of the need for adapting the program for children with intellectual disabilities. These adaptations should be included in the program, with suggestions of different approaches to accommodate different types of disabilities.

Children with communicative and/or intellectual disabilities need knowledge on a vast array of topics within the scope of abuse prevention. To provide a common ground, knowledge on feelings, sexuality, and children’s rights needs to be established before teaching about abuse and neglect. All information should be age and disability appropriate, and children with communication disabilities should be given access to the appropriate vocabulary to disclose abuse (Kim, Reference Kim2010). As many children with communicative and/or intellectual disabilities experience difficulties with generalisation, the key components of the program should be repeated over time.

Children with communicative and/or intellectual disabilities are dependent on their caregivers and are often trained to be compliant. This poses a challenge in view of abuse prevention. Therefore, children’s empowerment should be central to an abuse prevention program, highlighting that their voices need to be heard (UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2011).

Conclusion

Several challenges, but also possibilities, with implementing a school-based abuse prevention program were identified in the present study. The findings reported can be used to navigate the challenges of program development and implementation. Future studies should include a larger sample size to draw further conclusions on this important topic. Some difficulties that were mentioned by all three stakeholder groups concerned limited knowledge, time, resources, and support. In order to implement an abuse prevention program, it is imperative to first ensure that the needed factors are in place. If not, the program is bound to fail.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Petter Silfverskiölds Minnesfond, Stiftelsen Sunnerdahls Handikappfond, Helge Ax:son Johnsons Stiftelse, and Stiftelsen Solstickan.