Over the last decade, the concept of and orientation towards building community resilience to disasters has taken root.Reference Chandra, Acosta and Stern 1 – 3 Federal agencies have developed requirements and guidance to build community resilience, and local health departments are being required to include a range of community organizations in emergency preparedness and response activities. 4 , Reference Plough, Fielding and Chandra 5 Community resilience is not simply an expanded or enhanced version of emergency preparedness; rather, it rests on new skills such as community engagement, ability to leverage a range of community assets, and integration of routine and preparedness operations.Reference Mobula, Jacquet and Weinhauer 6

While government agencies strive to create more effective response and recovery plans and to forge stronger partnerships with a range of nongovernmental organizations, they are confronted with how to demonstrate improvement in resilience capacities and capabilities, particularly absent disaster. For many years, tabletop exercises have been used to test preparedness and response capabilities and to aid communities in ongoing quality improvement. These exercises have been widely used to test the ability of community health facilities to respond to infectious disease outbreak or to determine whether a coalition is ready to respond collaboratively in a disaster.Reference Frahm, Gardner and Brown 7 – Reference Klima, Seiler and Peterson 9

Given the use of tabletop exercises in traditional emergency preparedness activities (eg, hierarchical, emergency management), there is significant potential for application in the context of community resilience. We describe a process for developing a tabletop exercise to assess progress in community resilience.Reference Chandra, Acosta and Stern 1 , Reference Chandra, Williams and Plough 10 The aims of the article were twofold: (1) to outline the methods used to develop the tabletop and (2) to describe key themes from the pilot testing of the tabletop in the context of resilience.

METHODS

The tabletop exercise described here was developed for the Los Angeles County Community Disaster Resilience (LACCDR) project. LACCDR is a large demonstration project to assess how communities identify and test resilience-building activities in Los Angeles County.Reference Chandra, Williams and Plough 10 Eight communities (out of 16) emphasize coalition development to enhance resilience-based planning, whereas the other 8 communities were led in more traditional preparedness activities. Evaluation methods include a range of quantitative and qualitative approaches, such as resident and organization surveys and document review.Reference Chandra, Williams and Plough 10

LACCDR is rooted in an operational model of resilience, which utilizes a conceptual framework for community resilience that emphasizes the engagement, education, and interconnection of governmental and nongovernmental partners considered essential to a community’s ability to mitigate vulnerabilities and recover from stress. The work to develop this model was based on a comprehensive literature review and case study analysis by project team members to identify the elements most closely associated with the ability of a community to rapidly and successfully respond and recover from disaster. LACCDR has focused on 4 of the 8 levers: (1) partnership (developing strong partnerships within and between government and nongovernmental organizations), (2) engagement (promoting participatory decision making in planning, response, and recovery activities), (3) education (ensuring ongoing information to the public about preparedness, risks, and resources before, during, and after a disaster), and (4) self-sufficiency (enabling and supporting individuals and communities to assume responsibility for their preparedness).Reference Chandra, Acosta and Stern 1 Note that the other levers—wellness, access, quality, and efficiency—were not the focus of this effort. The team focused on these 4 levers because partnership and engagement of the community are key goals for the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health (the lead agency for LACCDR), education is essential to achieving broader community participation, and enhancing self-sufficiency is central to the concept of resilience capacity.

Developing the Tabletop Exercise

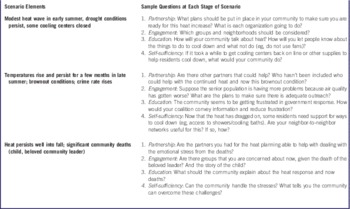

Although LACCDR employs various evaluation methods, there was no direct way to assess how a coalition in each of the 16 demonstration communities would act in an actual event. To assess the extent to which coalitions were strengthening the 4 resilience levers (Table 1), the team developed and conducted a community resilience tabletop exercise.Reference Frahm, Gardner and Brown 7 , Reference Agboola, McCarthy and Biddinger 8 The team identified a scenario that is seemingly modest at start (a heat wave) but then escalates over time with other changes in community conditions (crime increases, drought worsens, brownouts occur, and community members die). This allowed the coalition to consider the extent and quality of their partnerships and assets for an expansive and lengthy event rather than what is traditionally tested in tabletops, that is, a catastrophic or acute scenario. This scenario was designed to help the communities identify any gaps in assets and partnerships that may be less relevant in much less severe conditions but that would be critical for mitigating the overall negative impact. We reviewed the initial scenario and changing conditions with our LACCDR steering committee (comprised of a diverse set of government, community-based, and academic partners) to ensure that the scenario was logical and could be mapped to the 4 community resilience levers.

Table 1 Elements of the Community Resilience Tabletop Exercise and Sample Questions

The tabletop was conducted after the coalitions had completed initial action plans, had received training in all the core components of either standard preparedness or community resilience, and had just started to implement community programs or were planning to under their action plans.

Tabletop Content

The tabletop was designed to be relatively brief at 2 hours in order to create an exercise that was manageable yet potentially impactful. The presentation of the scenario with prompts and 2 unfolding situations lasted 1.5 hours; debriefing took 30 minutes (Table 1). Although an LACCDR project team member facilitated the sessions with a note taker, the exercise was intended to be self-guiding so that coalitions assumed responsibility for the discussion.

Tabletop Scoring

For each of the 4 levers, participants were asked to rate their response on a scale of 1 to 5 with 1 indicating a worse performance on the lever and 5 indicating the best performance. Coalition members were provided rating criteria and were asked to come to consensus on a single score for each lever. The facilitator and note taker independently rated the coalitions by use of the same criteria.

Tabletop Pilot Test

The tabletop exercise was conducted with all LACCDR coalitions (preparedness, resilience) from June 2014 to September 2014. Coalitions participated with a total of 203 members: 105 members from the preparedness coalitions and 98 members from the resilience coalitions. After the conclusion of the tabletop, the study team offered a summary of their impressions to the coalition for their ongoing efforts. The resilience coalitions received a more expansive summary with recommendations for action steps to improve their resilience responses (eg, ideas and strategies for improving partnerships), whereas the comparison coalitions received only a brief summary of their discussion with no recommendations. The tabletop will be administered at later time points to assess changes in coalition capacity over time; the results presented next describe the findings from baseline.

Analysis

Our analysis of the tabletop included 2 components. The first component was the tabletop scores. We present the findings from the perspective of the coalition and our study team raters (α=0.9). The second analysis was a review of the tabletop notes. We identified themes regarding which issues were raised and how coalitions planned to address the concerns.

RESULTS

The pilot test offered important insights about the perceived benefits and challenges of the design and content of the tabletop. We summarize the findings from the conduct of the tabletop scenario and the participant reactions, as well as the results from the exercise itself.

Process

Participants remarked that the nature of the tabletop scenario forced them to test their assumptions about the organizations in the coalition and the capacities they actually possessed. Because the scenario started with a common public health emergency for southern California (ie, heat wave), coalition members noted that they initially thought their response capacity would be much stronger and the activities would be straightforward. But, as the scenario evolved and worsened, those assumptions were tested and challenged beyond what some participants anticipated would be a required response. The project team purposefully did not reveal the scenario to coalition members in advance, which allowed members to react in real time. However, this lack of preplanning or “read ahead” appeared to unnerve some coalition members, who were used to traditional exercise designs with well-practiced scenarios, such as H1N1 or bioterrorism.

Exercise Outcomes

Table 2 summarizes the average coalition score for the resilience and preparedness coalitions and the average offered by the LACCDR project team. There was relatively close alignment between the coalition self-scores and the LACCDR team, although the tendency was toward slightly lower ratings by the LACCDR team. Overall, the resilience coalitions performed the same or better than the preparedness coalitions on partnership and self-sufficiency levers. Across both resilience and partnership coalitions, partnership was the lever in which coalitions felt the most confident.

Table 2 Average Ratings for Resilience and Preparedness Coalitions for 4 Community Resilience CoalitionsFootnote a

a Abbreviation: LACCDR, Los Angeles County Community Disaster Resilience. Statistical analysis of differences was not pursued because of sample sizes.

b Average across 2 LACCDR raters.

Overarching Themes

Although each coalition had a core of active members, the exercise quickly revealed that most coalitions did not have enough (both quantity and type) of the partner organizations needed for an escalating heat wave or changing conditions, such as the spike in crime rates. Many coalitions realized that they did not have enough engagement of organizations representing at-risk populations, particularly for an event that extended across a few months. As the exercise progressed, many coalitions noted that they did not have plans for reaching some of the housing developments or buildings that serve lower-income or immigrant populations.

Perhaps one of the most striking findings for coalitions was the lack of educational materials to cover topics as far ranging as heat to power outages to psychological impacts of disaster. Some coalitions had spent time developing materials for 1 or 2 scenarios, but had no materials that knitted together to address a compounding or multifactorial event. Self-sufficiency was discussed similarly across coalitions as participants determined that they would have to function with limited government assistance in the early stages of a challenging event yet had not fully developed the plans or capacities to achieve this.

Preparedness Coalition Themes

While most themes were experienced across coalitions, there were some interesting findings for each coalition type. Preparedness coalitions noted that their challenges in partnership were in developing a coordinated response, including difficulty in engaging sectors because many groups are not open to collaboration. In addition, coalitions were concerned that their greatest challenge to partnership was public apathy and lethargy. Furthermore, preparedness coalitions remarked that they had individual education activities but now needed to integrate these messages into one universal message. In discussing the efforts in engagement, some coalitions noted that there is no central hub to deal with different agencies on behalf of at-risk populations.

Resilience Coalition Themes

Resilience coalitions had work plans and processes to help them involve partners and integrate education. As such, their challenges were slightly different. The resilience coalitions had initial support from LACCDR to forge more partnerships across diverse sectors. But active involvement of these groups was still difficult, including getting stakeholders to use resources and engage specific at-risk populations. Regarding self-sufficiency, most resilience coalitions noted that neighbor-to-neighbor networks were stronger than when they started. However, they remained concerned regarding how to leverage daily stressful experiences to keep that level of self-sufficiency high. One common theme in the resilience coalitions was that they felt well equipped with education but knew they needed to have a way to share that information with the broader community for an emergency or disaster that extended longer than a month. Few coalitions had conducted a thorough asset analysis of their current organizational members, with attention to how those assets would be used or sequenced over a long response and recovery period.

DISCUSSION

The development and pilot testing of the community resilience tabletop revealed the benefits of using this approach to assess proxy indicators of resilience as well as to aid communities in determining how to improve resilience capacities. Coalitions noted that the exercise motivated them to consider whether they had the right mix of partners, particularly as the events unfolded, expanded, and worsened. The exercise further revealed that outreach to specific sectors, such as utilities and schools, was not as robust as previously anticipated. For resilience coalitions, which had the benefit of LACCDR support, there was somewhat more progress in these levers, although challenges remained regarding the diversity and sustainability of these partnerships.

As noted earlier, the timing of this exercise allowed the coalitions to have developed a plan to evaluate or use as a basis for the exercise. However, the more complex construct of community resilience, which may be more long-term to develop, was still relatively new to coalitions in terms of implementing programs beyond standard preparedness (eg, CERT [Community Emergency Response Team] training). Given the novel features of community resilience and its dependence on growth in relationships and culture of communities, the differentiation of groups would be expected to take time.

The use of a tabletop exercise was part of a suite of assessment activities integral to the LACCDR. The tabletop had a dual purpose, serving to help the study team analyze coalition progress and providing coalitions with valuable insight to inform ongoing quality improvement and capacity building. The tabletop exercise is a critical community resilience tool for communities to assess their current and potential capacity to mitigate the impact of an event on their community and the people who live there, especially people who may need additional help.

While the exercise offered keen insights for LACCDR, it was a pilot effort and as such, there are important limitations to note. First, the exercise was reviewed for local context appropriateness, and the team worked to have all relevant coalition members in each exercise, but scheduling issues may have precluded attendance from all members. Those absences may have hampered the perspectives of relevant sectors. Second, the assessment scales were developed on the basis of 4 resilience levers from the community resilience framework used in LACCDR. Although the framework and levers are based on empirical research, the framework continues to be tested. Thus, scores should be appropriately contextualized given the limitations of the scales used (eg, construct validity). Third, the geographic and climate diversity of Los Angeles County means that some communities have more experience with continuous ongoing heat than do others, and the impact of some aspects of the scenario (eg, civil unrest) would likely be experienced very differently in every community. The scores and reactions of coalitions must be assessed within this context.

Despite these important caveats, the use of a tabletop scenario to test resilience assets and capacities offers great potential for future resilience assessment, absent an actual event. In addition, the benefits of community quality improvement are clear in this pilot, providing important insights for coalitions about where and how they can strengthen their response and recovery planning efforts.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Emergency Preparedness cooperative agreement and by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. We thank the full LACCDR study team and coalition members.

Author Contributions

Anita Chandra conceptualized the tabletop exercise and led the development of this article. Malcolm Williams contributed to development and conduct of the tabletop exercise, including data analysis. Christian Lopez contributed to conduct and analysis of the tabletop exercise summarized in this article. Jennifer Tang also contributed to conduct and analysis of the tabletop exercise summarized in this article. David Eisenman contributed to the design of the tabletop exercise. Aizita Magana informed the content of the exercise and supported execution of the pilot phase of tabletop exercise development reported here.