Introduction

The cognitive model proposes that beliefs concerning shape, weight, eating/food and the implication of these for the self (Hunt and Cooper, Reference Hunt and Cooper2001; Vitousek, Reference Vitousek and Salkovskis1996; Vitousek and Hollon, Reference Vitousek and Hollon1990) promote the maintenance of the emotional distress and symptomatology of anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Once such beliefs are formed, information processing biases are suggested to select for information consistent with them (Blackburn and Davidson, as cited in Hunt and Cooper, Reference Hunt and Cooper2001). A number of information processing biases have been studied, including attentional, interpretational and selective memory biases (see Lee and Shafran, Reference Lee and Shafran2004; Williamson, White, York-Crowe and Stewart, Reference Williamson, White, York-Crowe and Stewart2004 for a review). However, despite the theoretical importance of evaluating the role of memory biases, reviews highlight a lack of research in this area (Harvey, Watkins, Mansell and Shafran, Reference Harvey, Watkins, Mansell and Shafran2004; Lee and Shafran, Reference Lee and Shafran2004).

The cognitive model suggests memory biases select for information congruent with beliefs about weight, shape and eating/food; thus this information is more elaborately encoded and/or more readily recalled as there are more cues for retrieval (Hermans, Pieters and Eelen, Reference Hermans, Pieters and Eelen1998). Few studies that evaluate this have been conducted; this study will focus on three key studies, namely Sebastian, Williamson and Blouin, Reference Sebastian, Williamson and Blouin1996; Hermans et al., Reference Hermans, Pieters and Eelen1998; and Hunt and Cooper, Reference Hunt and Cooper2001. Sebastian et al. (Reference Sebastian, Williamson and Blouin1996) conducted a study involving three groups of 30 females: weight preoccupied, non-weight preoccupied, and a heterogeneous eating disorder group with diagnoses of anorexia nervosa (AN; n = 10), bulimia nervosa (BN; n = 10) and EDNOS (n = 10). The stimulus words were categorized as “fat body”, “non-fat body”, and neutral (Sebastian et al., Reference Sebastian, Williamson and Blouin1996, p. 279). The results indicated that the eating disorder group recalled significantly more fat body words than non-fat body or neutral words, which was not found in either of the non-clinical groups (Sebastian et al., Reference Sebastian, Williamson and Blouin1996). A limitation of this study is the use of negatively toned words, as it is possible the memory bias shown was for the negative tone of the words due to the presence of depression (Hunt and Cooper, Reference Hunt and Cooper2001).

Hermans et al. (Reference Hermans, Pieters and Eelen1998) looked at implicit and explicit memory in females with AN (n = 12) and non-dieting controls (n = 12). The explicit memory task stimulus words were anorexia-related, positive, negative and neutral words with the same affective valence noted for the anorexia-related and anorexia unrelated words (Hermans et al., Reference Hermans, Pieters and Eelen1998). The results indicated that individuals in the AN group exhibited an explicit, however not implicit, memory bias for anorexia related words that was not shown by the control group (Hermans et al., Reference Hermans, Pieters and Eelen1998). A limitation of this study was that the weight/shape words were not distinguished from food words in the anorexia-related word category and as with the Sebastian et al. (Reference Sebastian, Williamson and Blouin1996) study, levels of hunger were not considered.

Hunt and Cooper (Reference Hunt and Cooper2001) considered both levels of depression and the valence of the words (Lee and Shafran, Reference Lee and Shafran2004). Furthermore, the impact of hunger on the recall of food words was assessed. Three groups of female participants were included in the study, these were BN (n = 12), depression (n = 12) and control (n = 18). The stimulus words included five categories: weight/shape words; food words; emotion words; neutral body words; and neutral nouns, each category containing 24 words. The first three categories of words subdivided into equal numbers of positively and negatively toned words (Hunt and Cooper, Reference Hunt and Cooper2001). The study found that females in the bulimia group showed “a bias to recall positive and negative weight/shape words compared to emotional words, but not compared to neutral nouns and body words” (Hunt and Cooper, Reference Hunt and Cooper2001 p. 93). Whilst the BN group recalled more food related words than the control group, this was also the case for the depression group. Furthermore, this enhanced recall correlated with levels of hunger for both groups, which led the authors to suggest enhanced recall for food words was dependent on levels of hunger (Hunt and Cooper, Reference Hunt and Cooper2001). The limitations of the study include its specificity to bulimia nervosa and small sample size.

Lee and Shafran (Reference Lee and Shafran2004) suggest future research should address two key areas. First, the inclusion of the range of eating disorders seen in clinical practice. As the most prevalent and least researched diagnoses (Fairburn and Harrison, Reference Fairburn and Harrison2003), it would seem useful to conduct research that includes EDNOS. Second, that there is a need for future research to be more ecologically valid to gain better insight into how memory biases operate in everyday life (Lee and Shafran, Reference Lee and Shafran2004). In line with this, Nikendei et al. (Reference Nikendei, Weisbrod, Schild, Bender, Walther and Herzog2008) considered memory biases using pictorial and semantic food related stimuli. Three groups, AN (n = 16), 16 control participants that had food prior to the task and 16 that had fasted prior to the task took part (Nikendei et al., Reference Nikendei, Weisbrod, Schild, Bender, Walther and Herzog2008). The authors concluded there were “behavioural indications of abnormal processing of food related and neutral stimuli” (p. 439) for the AN group that were similar to fasting controls, with no significant difference between the AN and non-fasting control group (Nikendei et al., Reference Nikendei, Weisbrod, Schild, Bender, Walther and Herzog2008). This perhaps highlights the importance of considering hunger in relation to the encoding task.

Legenbauer, Maul, Rühl, Kleinstäuber and Hiller (Reference Legenbauer, Maul, Rühl, Kleinstäuber and Hiller2010) suggest that BN has been “largely overlooked” within the literature related to memory biases (p. 304). This study included a BN group (n = 25) and control group (n = 27) that were “exposed to body related, food related and neutral TV commercials” (p. 349). The results suggested a memory bias for the BN compared to the control group; however, this was for poorer recall and recognition of body-related rather than “schema consistent materials” (p. 312) e.g. weight as suggested in previous research (Sebastian et al., Reference Sebastian, Williamson and Blouin1996).

In an attempt to clarify the role of memory biases and extend the current literature, the current study aims to consider memory biases for weight/shape and food words utilizing, as far as possible, the methodology of Hunt and Cooper (Reference Hunt and Cooper2001). The study aims to extend this research in terms of sample size and ecological validity via the inclusion of females with EDNOS as a discrete group.

Hypotheses

1. Females with BN will recall more weight/shape and food words, both positively and negatively toned, compared to all three other word categories (emotion, neutral nouns, and neutral body words). As suggested by the transdiagnostic theory this will also be demonstrated by the EDNOS group, but not by the control group. Furthermore, that differences in the recall of food words will not be accounted for by differing levels of hunger between groups.

2. Information related to current concerns, namely negative weight, shape and food related information, will be more unpleasant for females in the bulimia nervosa and EDNOS groups than the control group.

Method

Design

The study's design is quasi experimental with independent samples completing self-report questionnaires and a memory task.

Participants

Inclusion criteria for all participants was a body mass index (BMI) within the normal range (BMI of 18.50 – 24.99) as defined by the World Health Organization (2006), aged 18–35 and English as a fluent language. Exclusion criteria were current problematic substance use and a history of traumatic head injury. Inclusion criterion for the eating disorder groups was a diagnosis of bulimia nervosa or EDNOS, with the diagnostic items of the eating disorder examination (EDE) completed to highlight symptomatology consistent with these diagnoses (American Psychological Association (APA), 2000). EDNOS was defined as a clinically significant eating disorder as assessed by the researcher using the EDE and DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2000) criteria. An exclusion criterion for the eating disorder groups was current inpatient treatment. Specific exclusion criteria for the control group were the participant reporting a diagnosed eating disorder, current clinical depression, or formal dieting in the past 4 weeks. Clinical depression was not an exclusion criterion for the eating disorder groups as “depressive symptoms and major depressive disorder” are suggested to be prevalent in females with bulimia nervosa (Wildes, Simons and Marcus, Reference Wildes, Simons and Marcus2005 p. 9).

Fifty-one participants met inclusion criteria; 16 in the Bulimia Nervosa group, 18 in the EDNOS group, and 17 in the control group.

Measures

Demographic information

Participants were asked their educational level, age and number of years in education post 16 years of age. Weight and height were taken to calculate BMI; participants in the eating disorder groups were given the option to have this taken from their records. All participants described themselves as fluent in English.

In line with Rees (Reference Rees2002) this study used only the diagnostic items of the EDE (12th edition; Fairburn and Cooper, Reference Fairburn, Cooper, Fairburn and Wilson1993) to highlight bulimia nervosa or EDNOS. The Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDEQ) self-report measure (Fairburn and Beglin, Reference Fairburn and Beglin1994) was used to provide a subjective assessment of symptomatology over the past 28 days for all groups. Both the EDE and EDEQ are suggested to be reliable and valid (Fairburn and Cooper, Reference Fairburn, Cooper, Fairburn and Wilson1993; Shafran and Robinson, Reference Shafran and Robinson2004).

As the study words were presented both aurally and in writing, the National Adult Reading Test second edition (NART2; Nelson, Reference Nelson1991) was used to ensure groups were matched in terms of comprehension of written English. Scores on the NART2 are highlighted as not affected by the presence of depression (Crawford, Besson, Parker, Sutherland and Keen, Reference Crawford, Besson, Parker, Sutherland and Keen1989). The Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI II; Beck, Steer and Brown, Reference Beck, Steer and Brown1996) was included, which is suggested to have high reliability and validity. A hunger rating scale (HRS; Grand, Reference Grand1968) was used to measure levels of hunger, as used by Hunt and Cooper (Reference Hunt and Cooper2001).

The 120 words used by Hunt and Cooper (Reference Hunt and Cooper2001) formed the basis for stimulus words used in this study. These break down into five categories: positively and negatively toned weight/shape words; food words; emotion words; neutral body related words; and non-body related neutral words (see Hunt and Cooper, Reference Hunt and Cooper2001 for selection criteria for the words). The emotional valance of the word set was re-rated by three female eating disorder service users, after which 39 additional words were generated. As in the Hunt and Cooper (Reference Hunt and Cooper2001) study the words were then rated for emotional valence by 14 female postgraduates. Four words were substituted in the neutral noun category and two words added to each category in an attempt to increase the percentage agreement between raters for the final word set (Appendix 1). As with the Hunt and Cooper (Reference Hunt and Cooper2001) study, positively valenced words were defined as thin related and negatively valenced as fat related.

Procedure

The bulimia and EDNOS groups were recruited via clinicians in NHS adult mental health services and voluntary services. The general population control group was recruited through strategies such as posters. Following informed consent, demographic information was recorded after which females in the eating disorder groups were interviewed using the diagnostic items of the EDE. All females then completed the HRS. Participants were then asked to listen to 130 tape-recorded words in a “random fixed order” and to “imagine themselves in a scene involving the word and themselves” (Hunt and Cooper, Reference Hunt and Cooper2001, p.96). The words were presented one every 15 seconds. Initially up to six practice trials were completed. After completing a distracter task of counting backwards in threes from 100 for 20 seconds (Hunt and Cooper, Reference Hunt and Cooper2001), participants were given a sheet of paper and asked to recall as many words as possible. Only exact words were scored in terms of the suffix; however words spelt incorrectly that did not change the sense of the word were included. The NART2, BDI II and EDEQ were then completed.

Results

Sample characteristics

The demographic information and questionnaire totals are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic information and questionnaire means and standard deviations by group

Standard deviations in parentheses; Mean years education 16+ = the mean number of years in full time education from the age of 16 upwards.

*N = 49 One participant did not complete the NART2. One participant's data were excluded.

**The BDI II was totalled both including and excluding question 18 concerning appetite to consider if this had a significant impact on the scores for the bulimia nervosa and EDNOS groups.

Preliminary analysis

One way analysis of variance (ANOVA) indicated no significant differences between groups for age, F (2, 48) = 2.56, p = .09, ŋр2 = 0.10, level of education, F (2, 48) = 1.37, p = .27, ŋр2 = 0.05 and BMI F (2, 48) = 0.51, p = .60, ŋр2 = 0.58. One way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni tests indicated no significant differences for the NART2 F (2, 46) = 0.11, p = .90 ŋр2 = 0.02. Following a log transformation completed as Levenes test was significant (Wuensch, Reference Wuensch2006), a significant difference was found between groups on the BDI II both including (F (2, 48) = 33.49, p < .001, ŋр2 = 0.58) and excluding (F (2, 48) = 30.63, p < .001, ŋр2 = 0.56) question 18 concerning appetite, with both eating disorder groups scoring significantly higher than the control group (p < .001). A Kruskal Wallis ANOVA highlighted a significant difference between groups (x 2(2,N=51)=32.21,p=<.01); with both the bulimia nervosa (U = 0.00, r = −0.85) and EDNOS (U = 5.00, r = −0.83) groups scoring significantly higher on the EDEQ than the control group (p < .001).

Analysis for the total word recall by group

Table 2 highlights the mean number of words recalled by word type and in total for each group. A one-way ANOVA revealed no significant differences between groups for total words recalled F (2, 48) = 0.10, p = .90, ŋр2 = 0.00.

Table 2. Means and standard deviations for words recalled in total and for each word category by group

Standard deviations in parentheses

Analysis of word valence recall

Two three-way mixed ANOVAs were completed to consider any differences in terms of the valence of the words recalled for the three word categories containing both positively and negatively valenced words (weight/shape, food, and emotion). The first [group x words type (weight/shape versus emotion words) x valence (positive versus negative)] with repeated measures on the second and third factors indicated no significant interaction for group by valence F(1, 48) = 0.64, p = .53, ŋр2 = 0.03 or group by word type by valence F(2, 48) = 0.63, p = .54, ŋр2 = 0.03. The between group main effect was non-significant F(2, 48) = 0.37, p = .70, ŋр2 = 0.02.

The second three way mixed ANOVA [group x words type (food versus emotion words) x valence (positive versus negative)] with repeated measures on the second and third factors indicated no significant interaction for group by valence F(1, 48) = 1.02, p = .37, ŋр2 = 0.04 or group by word type by valence F(2, 48) = 0.37, p = .70, ŋр2 = 0.02. The between group main effect was also non-significant F(2, 48) = 0.91, p = .91, ŋр2 = 0.01.

Hypothesis 1: analysis for the recall of the word set

A two-way ANOVA [group (control, bulimia nervosa and EDNOS) by word type (weight/shape, food, emotion word, neutral nouns, and neutral body words)] with repeated measures on the second factor was conducted. The Greenhouse-Geisser correction was used as Mauchly's test of Sphericity was significant (p = .019), which indicated a significant main effect of word type, F(1, 3.42) = 11.52, p < .001, ŋр2 = 0.19. The interaction of group by word type (F(2, 6.84) = 1.38, p = .22, ŋр2 = 0.05) and the between group analysis (F(2, 48) = 0.132, p = .88, ŋр2 = 0.05) were non significant.

This analysis was then repeated with the two eating disorder groups combined into one group. The results of this analysis highlighted a significant main effect of word type (p < .001), with both the interaction of group by word type (p = .05) and the between group analysis being non significant when the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied (p = .62).

A new variable was then computed prior to completing the a priori contrasts that allowed the specific area of interest for Hypothesis 1 to be considered; this weighted the word categories positively and negatively (Fields, Reference Field2005), with the weight/shape and food words weighted positively and the neutral nouns, neutral body words, and emotion words weighted negatively. Two a priori orthogonal contrasts were conducted via a univariate ANOVA which was significant F(1, 48) = 3.231, p = .048, ŋр2 = 0.12. The first contrast indicated that the two eating disorder groups, but not the control group, recalled significantly more weight/shape and food words compared to all other word categories (p < .001, 95% confidence interval [CI] between groups on the weighted word variable, 22.50, 52.19). The second contrast revealed no significant differences between the two eating disorder groups for the recall of weight/shape and food words compared to the other three word categories (p = .63, 95% CI, -10.65, 6.51).

Hunger and recall of food words

No significant relationship between hunger and recall of food words was found using non parametric tests (all p > .05).

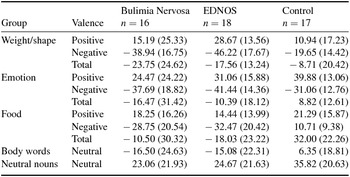

Hypothesis 2: pleasantness of the stimulus words

The means and standard deviations by group for the pleasantness ratings of the words are shown in Table 3. One way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni tests were used to consider group differences for the pleasantness ratings of all the word types. A significant difference was found between groups for the positive weight/shape words F(2,48) = 4.12, p = .02, ŋр2 = 0.15, with the EDNOS however not the BN group rating these words as significantly more pleasant than the control group (p = .02). A significant difference was found between groups for the negative weight/shape words F(2, 48) = 12.18, p < .001, ŋр2 = 0.34, with both the BN and EDNOS groups rating the words as significantly more unpleasant than the control group (p < .001).

Table 3. Means and standard deviations for pleasantness ratings for each word category by group

Standard deviations in parentheses

No significant differences were found between groups for the positive food words F(2,48) = 0.88, p - .42, ŋр2 = 0.04. A Kruskal Wallis ANOVA indicated a significant difference between groups for the recall of negative food words (x 2(2,N=60)=30.47,p=<.001). Post hoc Mann Whitney tests indicated both the BN (U = 3.50, r = −0.83) and EDNOS (U = 10.00, r = −0.80) groups rated the words significantly more unpleasant than the control group (p < .001).

No significant differences were found between groups for the pleasantness ratings of positive or negative emotion words or neutral nouns. A significant difference was found between groups for neutral body words F(2, 48) = 5.95, p = .01, ŋр2 = 0.20, with the BN and EDNOS groups rating the words significantly more unpleasant than the control group (p = .01).

Discussion

Hypothesis one states that females with BN will recall more weight/shape and food words, both positively and negatively toned, compared to all three other word categories (emotion, neutral nouns, and neutral body words). As suggested by the transdiagnostic theory this will also be demonstrated by the EDNOS group, but not by the control group. Furthermore, that differences in the recall of food words will not be accounted for by differing levels of hunger between groups.

The results for hypothesis 1 indicated that, whilst the omnibus ANOVA highlighted a main effect of word type, the interaction of group by word type and the between group differences were non significant. This finding is not consistent with the prediction of hypothesis one. A priori contrasts were used to consider the specific prediction of hypothesis 1 in relation to the pattern of word categories recalled between groups. The orthogonal contrasts completed allowed greater specificity in terms of analyzing this specific prediction (Field, Reference Field2005).

The a priori contrasts indicated that females in the bulimia nervosa and EDNOS groups, but not the control group, recalled more weight/shape and food related words compared to all other word categories (emotion words, neutral nouns and neutral body words). This finding is consistent with the cognitive model of eating disorders (e.g. Fairburn, Reference Fairburn1981; Vitousek and Hollon, Reference Vitousek and Hollon1990) in relation to memory biases for weight/shape and food-related information. In line with the transdiagnostic cognitive model, the second contrast found no significant difference between the two eating disorder groups. Unlike the Hunt and Cooper (Reference Hunt and Cooper2001) study, enhanced recall for food words was not found to be dependent on differing levels of hunger between groups. Hypothesis 2 proposed that information related to current concerns would be more unpleasant for females in the eating disorder groups. The results demonstrated that both the bulimia nervosa and EDNOS groups found the negative weight/shape (p < .01), negative food (p < .01) and neutral body (p < .05) words significantly more unpleasant than the control group. The EDNOS, however not the bulimia nervosa group, found the positive weight/shape words significantly more pleasant than the control group (p < .05). No significant differences were found between groups for the neutral nouns, positive food words or emotion words.

Sebastian et al. (Reference Sebastian, Williamson and Blouin1996) propose that memory biases in eating disorders may be similar to those for depression. This is important to consider in the current study given the significant difference between both the eating disorder groups compared to the controls for mean BDI II score. Both the eating disorder groups rated the negative weight/shape and negative foods words, but not the negative emotion words, as more unpleasant than the control group. This supports Hunt and Cooper's (Reference Hunt and Cooper2001) conclusion that the memory biases are specific to weight/shape and not to negatively toned words per se as suggested for individuals with depression (e.g. Ridout, Astell, Reid, Glen and O’Carroll, Reference Ridout, Astell, Reid, Glen and O’Carroll2003). There were also no differences in the total recall of words between groups, which could suggest that the groups did not differ in terms of concentration. It is therefore possible that whilst the cognitive style of females with eating disorders and depression are similar, the precise content of the cognitions differ (Phillips, Tiggemann and Wade, Reference Phillips, Tiggemann and Wade1997).

In line with the Williams, Watts, MacLeod and Mathews (Reference Williams, Watts, MacLeod and Mathews1997) model, the results suggest it is possible information related to weight/shape and food could be more elaborately encoded and readily retrieved for individuals experiencing BN and ENDOS. Through the process of elaboration, stronger links would be made between concepts leading to more retrieval cues being available (Hermans et al., Reference Hermans, Pieters and Eelen1998). Hermans et al. (Reference Hermans, Pieters and Eelen1998) suggest that in relation to anorexia nervosa this process could “lead to the formation of strong associative links between . . . anorexia-related concepts and many other (often neutral) memory representations” (Hermans et al., Reference Hermans, Pieters and Eelen1998 p. 198). In the current study, the percentage concordance of raters was lowest for the neutral noun category, which perhaps suggests the difficulty of finding truly neutral words.

The lack of an overall significant difference between groups for the omnibus ANOVA completed for hypothesis 1 contrasts with the Hermans et al. (Reference Hermans, Pieters and Eelen1998) and Sebastian et al. (Reference Sebastian, Williamson and Blouin1996) studies, which reported differences between groups. This could reflect the differing diagnoses of the participants, that this study was underpowered, or methodological differences between the studies e.g. word types.

There are a number of limitations to this research. The most important of these is the small sample size. The difficulties encountered recruiting to all groups are reflected in the unequal numbers in the groups and that the numbers required for the a priori power calculation were not achieved, which has implications for the generalization of the findings. This could also explain the non significant result between groups for the omnibus ANOVA. Other limitations of the research include the use of words as the stimuli, which could have lowered the ecological validity of the study, and the specific word set used. The word set being so large (N = 130 words) could have led to floor effects and is recognized to be beyond human memory capacity. It is acknowledged that the number of words in each category was too high given the number of participants. It is also recognized that asking participants what they imagined when instructed to imagine themselves in a scene with the word could have strengthened the methodology. A further limitation is the exclusive reliance on a free recall paradigm relative to a recognition paradigm.

An additional limitation of the word set relates to the difference in imageability of words as suggested by the University of Western Australia (UWA) database (1981); with the neutral nouns and body words being significantly more imageable than the weight/shape words and the food words more imageable than the emotion words. This could explain the difference found between the recall of food and emotion words in terms of the emotion words being less imageable than food words; however, this does not explain the within group differences.

Given the above limitations, this study suggests support for the cognitive model of eating disorders (e.g. Fairburn, Reference Fairburn1981) in that the a priori contrasts revealed both eating disorder groups recalled significantly more weight and shape and food words than the control group. Importantly, this was not found to relate to difference levels of hunger between groups. Both eating disorder groups also found weight and shape, food and neutral nouns more unpleasant than the control group. This suggests the importance of considering the role of memory biases within clinical practice when working with clients. This study provides preliminary support for the use of the transdiagnostic approach to the theory and treatment of eating disorders and highlights the importance of future research that considers this approach to treating eating disorders.

Acknowledgements

Massive thanks go to all who participated in and supported this research.

Appendix 1. Final word data set

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.