1. Introduction

It is well-known that in German, past participles can occur in root position with a directive illocutionary force, as in 1 (Fries Reference Fries1983, Donhauser Reference Donhauser, Eroms, Gajek and Kolb1984, Gärtner 2013, Heinold Reference Heinold2012, Reference Heinold2013, among others).

(1)

The directive interpretation is sometimes suggested to follow from the fact that infinite root clauses can be seen as a special case of imperatives: Like imperatives, they denote properties rather than propositions (Gärtner 2013:217). Still, past participles as root clauses do not have to exhibit directive illocutionary force, as shown by Fries (Reference Fries1983:52), who gives the example Abgemacht! lit. ‘agreed’, without commenting on the interpretation, though. This example shows that past participles in root position can also have a performative illocutionary force.Footnote 2 Other examples are given in 2, where the speaker performs the speech act denoted by the verb by saying that the speech act in question has been performed, thus the illocutionary force is that of a performative (Searle Reference Searle1989:536).Footnote 3

(2)

The performative participles in 2 are formed from verbs denoting speech acts such as compliance with a request (in a broader sense) or confirming a statement. In 2a, the participle is used as “linguistic feed-back” (Allwood et al. Reference Allwood, Joakim and Elisabet1992): It serves as a response from the hearer to grant a request. In 2b, the performative participle occurs in a monological use and has the—informationally redundant—effect of acknowledging the truth of a proposition: The speaker explicitly concedes to a widely held opinion. In both cases, the performative participle alternates with the affirmative response particle Ja! ‘Yes!’, or Nein! ‘No!’, if it is a confirmation of a negative statement, as in 2a. The core use of the performative participle is to signal that a proposition p may safely be added to the Common Ground (CG). The agent, which is understood to be the speaker, is left unexpressed, as is the propositional argument of the speech-act-denoting verb: A contextually resolved propositional content counts as promised or granted by virtue of the participle being uttered. I refer to this use of the past participle as the performative past participle (henceforth: PfP).

It is not unusual for past participles to occur alone in various contexts in German, as in 3 (Behr Reference Behr1994, Redder Reference Redder and Hoffmann2003).

(3)

In 3, the nonspeech-act-denoting verb gerettet ‘saved’ is used assertively to state that the character referred to as er ‘he’ is saved, or rather considers himself to be saved. Such uses lend themselves to an analysis as a reduced clausal structure along the following lines: [er ist] gerettet ‘[he is] saved’. The same pertains to the following examples, where the participles are used assertively “out of the blue”, and the theme argument in 4a (whatever the speaker has managed to do) is found in the extralinguistic context.

(4)

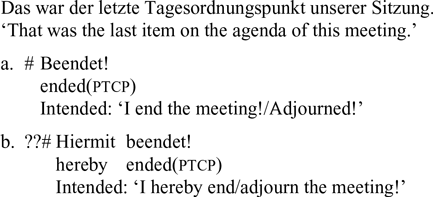

Yet, the PfP has special properties that need to be accounted for. First, not all performative verbs can occur as PfPs. A performative verb such as beenden ‘to end’ cannot occur as a PfP, as shown in 5a, a continuation of the sentence in 5. This verb is (marginally) better as a PfP if accompanied by hiermit ‘hereby’, which forces a performative reading, as in 5b.Footnote 4

(5)

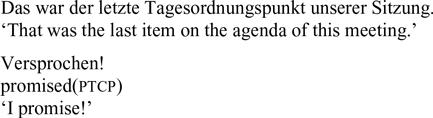

The performative verbs that can form PfPs, in contrast, do not require hiermit ‘hereby’ to be used performatively:

(6)

Second, performative verbs allow both assertive and performative readings, but the past participle in 7 only has the performative reading. It cannot be understood assertively as ‘this has been promised’.Footnote 5

(7)

PfPs are primarily found in colloquial German, although participle constructions are generally taken to belong to a formal or literary style (Redder Reference Redder and Hoffmann2003:156).Footnote 6 Participles in performative use are known from classical Semitic languages (Rogland Reference Rogland2001, Wild Reference Wild1964:253–254) and also from Dutch (Rooryck & Potsma Reference Rooryck, Potsma and van der Wurff2007).Footnote 7 For a recent crosslinguistic discussion of performative participles, see Fortuin Reference Fortuin2019. In German, they appear to have received little attention in the literature. They are briefly mentioned in Dal Reference Dal1966:120, in the influential account of nonfinite main clauses in Fries Reference Fries1983:52, 236, and also in Rapp & Wöllstein Reference Rapp, Wöllstein, Ehrich, Fortmann, Reich and Reis2009:167, but they are not described as performatives, nor are they discussed in detail. Brandt et al. (1989:5) give an overview of performative utterances in German and provide one example of a past participle in root position: Baden verboten lit. ‘swimming forbidden’, while Liedtke (Reference Liedtke1998) and Colliander & Hansen (Reference Colliander and Hansen2004) do not mention the PfP at all in their discussions of speech acts in German. The Duden grammar (2006) does not comment on this use of the past participle, while Zifonun et al. (Reference Zifonun, Ludger and Bruno1997:2226) describe examples such as offen gestanden ‘frankly admitted’ and ehrlich gesagt ‘honestly said’ as stereotypical phrases commenting on the manner of speaking. The performative use as in Versprochen! ‘(I) promise!’ or Geschenkt! ‘Granted!’ does not seem to be mentioned.

Dal (Reference Dal1966:120) suggests that the use of participles such as offen gestanden ‘frankly admitted’ and Zugestanden! ‘I admit!’ lit. ‘admitted’, that is, as root clauses, is of a similar kind (“von ähnlicher Art”) as instances of the directive past participle, but this cannot be entirely true: Performativity is not a subtype of directive force (Fries Reference Fries1983:52 also draws a distinction between participles with a directive reading and participles with other readings), and there are differences between the two uses of the past participle. The directive participle can occur with a quantified subject (see, among others, Fries Reference Fries1983, Gärtner 2013:204), as in 8a and with an accusative object, as in 9a (Donhauser Reference Donhauser, Eroms, Gajek and Kolb1984:369, Gärtner 2013:210, Heinold Reference Heinold2013).Footnote 8 The PfP permits neither of this as shown in 8b and 9b.Footnote 9

(8)

(9)

A further striking difference is that the directive participle can be used “out of the blue”, while the PfP needs a supporting context for its interpretation. Thus, the PfP is different from the directive participle and deserves a discussion on its own.

The goal of this article is to show that a participle in root position can indeed be used performatively in German and to provide a description and an analysis of this phenomenon given that it has received little attention. I concentrate on PfPs used as responses, and the main focus is on description; but I also briefly show how the properties uncovered can be captured in the formal framework of Lexical-Functional Grammar (LFG), even though I believe that the analysis can be formalized in other syntactic frameworks as well. Furthermore, I discuss the pragmatics of PfPs used as responses. I demonstrate that the PfP is primarily used to express agreement with an interlocutor and show how consent can be analyzed within a conversational framework such as the one developed for responses in Farkas & Bruce Reference Farkas and Bruce2010. Finally, I briefly show how the PfP is used for special rhetoric purposes in monological uses. Although there is a lot more to be said about the syntax, semantics, and pragmatics of PfPs, it is only possible to propose a preliminary syntactic and pragmatic analysis and to point to directions for future research.

The article is structured as follows: In section 2, I show that the PfP in its core use is restricted to a subset of speech-act-denoting verbs. In section 3, I discuss the performative interpretation of PfPs in German and compare PfPs with canonical (finite active) performatives. In section 4, I rule out alternative analyses by showing that the PfP is indeed a verbal participle and not a reanalyzed particle or a reduced clause. In section 5, I discuss the syntax of the PfP. In section 6, I show how the syntactic properties can be captured within LFG. Sections 7 and 8 give a preliminary account of the pragmatics of the PfP in dialogues, and section 9 shows how this analysis can be extended to monological uses. Finally, in section 10, I conclude.

2. The PfP and Performative Verbs

The PfP is formed using performative verbs, that is, verbs denoting actions that can be carried out by language. Performative verbs can be used assertively to describe the world (for example, to state that someone has declared war or made a promise) and performatively to change the world (a state of war or a promise comes into existence). Searle (Reference Searle1989:547) refers to this latter use as declarations and claims that declarations have a double direction of fit between word and world. By a successful performance of the speech act the world is changed according to the propositional content, and at the same time the utterance is a description of this new state of the world. Thus, successful declarations are self-fulfilling.

As mentioned above, PfPs cannot be formed with all performative verbs. First, performative verbs can be divided into two groups according to the outcome of the speech act, that is, what comes into existence. On the one hand, there are performative verbs such as taufen ‘to baptize’ and trauen ‘to wed somebody’. By uttering these verbs, the speaker creates a nonlinguistic fact, for example, that someone or something has been baptized or that someone has been wedded. On the other hand, there are performative verbs such as mitteilen ‘to announce’, versprechen ‘to promise’, and zugeben ‘to admit’, which create a new linguistic fact (Searle Reference Searle1989:549). By uttering Ich verspreche hiermit … ‘I hereby promise …’, the speaker creates the fact that a promise has been made, which is a linguistic fact. The PfP is primarily observed with verbs creating new linguistic facts. Verbs creating nonlinguistic facts are only marginally possible as PfPs if accompanied by hiermit ‘hereby’, as in 10 (see also example 5 above), while PfPs of verbs creating linguistic facts are possible without hiermit.Footnote 10

(10)

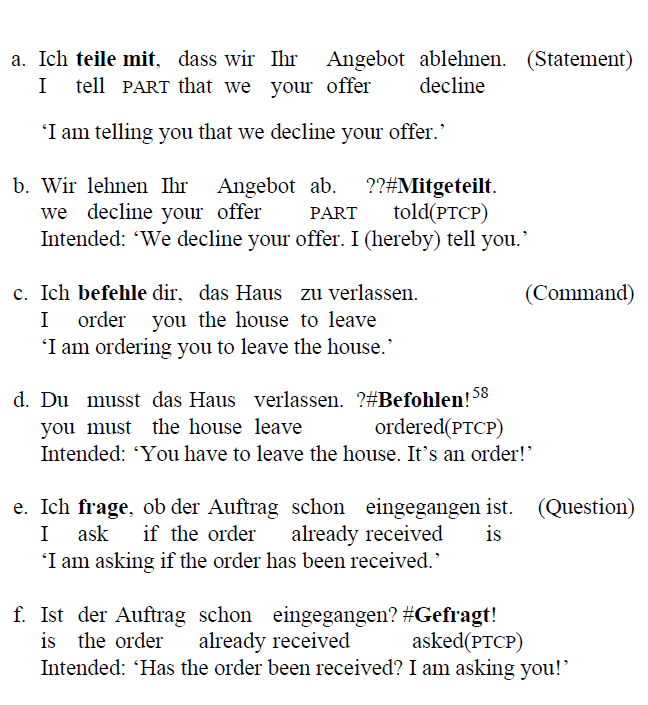

Second, the verbs denoting linguistic facts can be divided into verbs denoting initiating speech acts (such as fragen ‘to ask’) and verbs denoting responding speech acts (such as abmachen ‘to agree’). PfPs are found with verbs denoting responding speech acts, while verbs denoting initiating speech acts such as fragen ‘to ask’, sagen ‘to say’, mitteilen ‘to announce’ or beordern ‘to order’ are only possible as PfPs if accompanied by hiermit, an adverbial or an internal argument (see section 7.1):

(11)

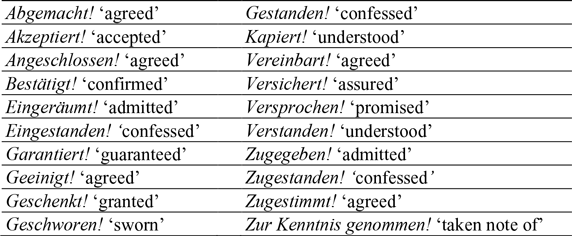

Finally, among the verbs denoting responding speech acts only those that express consent as opposed to disagreement can form PfPs. PfPs are primarily used to confirm an assertion or express readiness to comply with a request, but not to contradict an assertion or refuse a request (#Geleugnet! lit. ‘denied’, #Geweigert! lit. ‘refused’). I return to a discussion of this restriction in section 7.1 and suggest that PfPs are used as responses to express consent. Verbs attested as PfPs used as responses appear in table 1.

Table 1. Verbs used as PfPs.Footnote 11

It should be noted at this point that even within the category of performative verbs denoting responding supporting speech acts, the status of the various PfPs is not the same. PfPs such as Versprochen! lit. ‘promised’, Zugegeben! lit. ‘admitted’, Abgemacht! lit. ‘agreed’, and Akzeptiert! lit. ‘accepted’ are well established and generally accepted in performative use. Others, such as Geeinigt!/Zugestimmt!/Vereinbart!/ Angeschlossen! lit. ‘agreed’, are attested as PfPs, but are not found natural by all informants and appear to be rare as PfPs. One way to explain this contrast is to propose that there is a core set of verbs allowing the PfP, and that other verbs, such as sich einigen/zustimmen/ sich anschließen ‘to agree’, are used as PfPs by way of analogy, that is, resemblance with the core construction given that they express consent. Support for this proposal comes from the fact that the less acceptable verbs are often also syntactically different from the core verbs in selecting dative objects or genuine reflexive objects, while the core verbs select accusative objects.Footnote 12 Whether these less acceptable PfPs become established PfPs remains to be seen. It is in any case striking that even the deviant cases of PfPs conform to independently observed behavior of past participles in root position. For example, the reflexive object is omitted in the PfPs Geeinigt!/Angeschlossen! ‘Agreed!/It is settled!’. In order to provide as comprehensive an account of the PfP as possible, I include such (possibly occasional) uses in the discussion and leave a more fine-grained classification of core verbs and peripheral verbs in this construction for future research.Footnote 13

Finally, there are at least two verbs used as PfPs that do not usually qualify as performative verbs and do not occur as performative verbs in finite active performative sentences, or only marginally so. These are the verbs verstehen and kapieren ‘to understand’. On the face of it, verstehen and kapieren do not denote speech acts: They do not report communi-cative events unlike other performative verbs (Condoravdi & Lauer Reference Condoravdi, Lauer, Reich, Horch and Pauly2011:157), and one does not understand something just by claiming to understand it, that is, one cannot define an utterance to be an understanding. Nevertheless, the past participles of these verbs are used performatively. An example of verstehen is given in 12.

(12)

In B’s response in 12, verstanden ‘understood’ is interpreted performatively, as agreement to comply with the request made by A, while the finite form verstehe ‘I understand’ is not possible in the canonical finite active performative with hiermit.Footnote 14

The possibility of using participles of some cognitive verbs as performatives invites the conclusion that some verbs can be coerced to performative use under special circumstances in the sense of Pustejovsky Reference Pustejovsky1995 and Goldberg Reference Goldberg1995:195. Another explanation is due to a reviewer, who suggests that the participle could be a fragment answer to an implicit question containing the participle, as in 13a. However, an analysis as a fragment answer does not explain why verstehen and kapieren ‘to understand’ are much better in this use than verbs such as hören ‘to hear’, as in 13b.

(13)

Why exactly the verbs verstehen and kapieren can be used as performative verbs, as in 12, and what the special circumstances are, awaits further study.

3. The PfP as a Performative Speech Act

The canonical performative clause is a present tense active clause containing a 1st person subject and hiermit ‘hereby’: Ich VPERFORMATIVE hiermit … ‘I hereby VPERFORMATIVE …’. In 14, the speaker makes a promise by saying that s/he is making a promise, that is, the speaker defines the utterance to be a promise (Eckardt Reference Eckardt2012:22). Unlike the canonical performative clauses, the PfP—being nonfinite—does not contain tense. Yet, in a similar vein, speaker B in 15 defines his/her answer to be a promise using a PfP.

(14)

(15)

Thus, despite the lack of tense in 15, the performatives in 14 and 15 are understood to have the same illocutionary effect of making a promise.

However, there is an aspectual difference between the finite performative and the PfP: The finite verb in 14 focuses on the act of making a promise, and the resulting state of p [:speaker not telling hearer’s dad] being promised is inferred (with the propositional content of the complement clause in square brackets). In contrast, the participle in the PfP in 15 focuses on the resulting state: The speaker claims that a state of p [:speaker not telling hearer’s dad] being promised holds, and the event leading to this resulting state is inferred. In other words, the PfP denotes the state resulting from performing the speech act denoted by the verb and can be paraphrased as With this message, the state of p being Ved holds. Thus, a paraphrase of 15 is: With this message, the state of [me not telling your dad] being promised holds. In this sense, the PfP shows a clear affinity to the performatively used adjectival passive (Maienborn Reference Maienborn2007:89, Schlücker Reference Schlücker and Fryd2009:109), as in 16. I discuss this association in section 4.2.

(16)

The PfP shares with finite performatives the ability to license the adverb hiermit ‘hereby’. In fact, some performative verbs are more acceptable as PfPs if hiermit forces a performative reading, as shown in 5b and 10 above. Yet for PfPs such as Versprochen! ‘I promise!’, Zugegeben! ‘I admit!’, Geschenkt! ‘Granted!’, and Geschworen! ‘I swear!’ the presence of hiermit is not required at all.Footnote 15

(17)

Eckardt (Reference Eckardt2012:26) proposes that hiermit refers to the ongoing information exchange, as in the paraphrase with this message given for 15. The paraphrase for 15 shows that this is indeed a performative reading and not an assertive reading since hiermit has a different interpretation with assertive readings. In 18, hiermit occurs with a verb that does not denote a speech act, and it deictically refers to some extralinguistic action, which led to the successful completion of a task, not to the utterance itself.

(18)

Another characteristic feature of performative utterances is their strict speaker orientation. The subject of a finite performative verb is canonically in the 1st person, as shown in 14. In contrast, the PfP hardly ever appears with an overt agent phrase (a by-phrase is accepted by some speakers, but an agentive nominative subject is ruled out). Yet the agent of the PfP is almost always associated with the speaker, just like the agent in the performatively used adjectival passive in 16. The PfP in 19 can only mean that the speaker admits that Peter is late, not that Peter has admitted that he (Peter) was late.

(19)

It even seems to be the case that a participle of a performative verb must always be speaker-oriented, unlike a finite performative verb. For example, a clause with a finite performative verb can be used to assert that someone else is engaged in a performative speech act: In 20, the clause with a finite performative verb is embedded within reported speech, as indicated by the use of the reportive subjunctive verspreche ‘promise-prs.sbjv’. The speaker is reporting that Peter made an explicit promise.

(20)

A PfP in the very same context of reported speech is degraded, according to informants, that is, a PfP is not understood to mean that Peter has made a promise:

(21)

This could be an indication that PfPs are more strongly associated with performative use (and thus with the speaker) than clauses with finite performative verbs. The discourse in 21 appears incoherent, since the speaker is reporting what someone else has said, and at the same time s/he is understood to make a promise to the effect that Peter has really said this, that is, the PfP is understood to mean that the speaker is making a promise.Footnote 16

If the PfP is indeed more strongly associated with the speaker than finite active performatives, it should not be expected to occur in delegated speech. In delegated speech, the speaker is authorized to speak for someone else, and the subject is in the 3rd person and not in the 1st person (Eckardt Reference Eckardt2012:32–34, Tiersma Reference Tiersma1986:203). For example, in 22 the speaker makes a promise on behalf of the chancellor.

(22)

It is difficult to determine whether PfPs are used in delegated speech, since PfPs hardly ever occur with explicit agents. The PfP in 23 seems marginal, but it is hard to determine whether this is due to the presence of an explicit by-phrase or due to the fact it is an instance of delegated speech.

(23)

Even though it is possible to imagine a scenario like the one in 24, where a parent is speaking for her child, the lack of an explicit agent distinct from the speaker, as in 22, makes it almost impossible to determine whether the parent intends the utterance to be a promise of her own or to be a promise that her child allows her to make.Footnote 17

(24)

The PfP is only used without speaker orientation in questions, as in 25b, a continuation of 25, parallel to finite performatives occurring in questions, as shown in 25a. This appears to be a special case of performatives where the speaker asks the hearer to perform a performative speech act by providing an affirmative answer.

(25)

Another property that the PfP shares with the finite performative is that it cannot be denied or confirmed by the interlocutor (Eckardt Reference Eckardt2012:28–29). It is not possible for the hearer to deny that the speaker just made a promise, and confirming this is redundant since performative uses are always true (Condoravdi & Lauer Reference Condoravdi, Lauer, Reich, Horch and Pauly2011:151).

(26)

The data in this section have shown that the PfP clearly exhibits all the crucial features associated with the canonical finite active performative: It has the same illocutionary effect, it licenses hiermit, it is strictly speaker-oriented (even more so than the finite performative), and it can be neither denied nor confirmed. An important difference between PfPs and finite performatives is, however, that the PfP is restricted to a subset of those verbs that are observed in finite performatives. I return to this discussion in section 7.

4. PfPs as Particles, Adverbs or Reduced Clausal Structures

The question is whether the PfPs considered so far are indeed verbal participles and not particles or adverbs, and—if they are verbal elements—whether they could be analyzed as having some kind of a reduced clausal structure, for example, as adjectival passives, as suggested by Fries (Reference Fries1983:236). In the following sections, I provide evidence that PfPs are verbs, and that they are not associated with a reduced clausal structure.

4.1. The PfP is Not a Particle or an Adverb

The first question is not trivial because it is not unusual for past participles to be reanalyzed as other parts of speech. For instance, ausgenommen ‘exempted’ is used as a preposition or a subordinating conjunction, verdammt ‘dammed’ as an interjection, and ausgerechnet lit. ‘calculated–of all things/people/times’ as an adverb. Similarly, PfPs alternate with (affirmative) response particles such as Ja! ‘Yes!’, Okay!, Jawohl! ‘Yes, Sir’, Stimmt! ‘Right!’ or Genau! ‘Exactly!’, as shown in 27.Footnote 19

(27)

However, there is evidence to suggest that PfPs are true verbal participles and not response particles or adverbs. PfPs do exhibit unambiguous verbal properties. First, they license hiermit, as discussed above, manner adverbials, as in 28b,c, and even internal (recipient) arguments, as in 28d,e, whereas response particles and adverbs do not.

(28)

Second, PfPs do not modify other verbs. Krifka (Reference Krifka2007:16) provides an example of a past participle used as a speech-act-related expression, namely, a speech act adverbial that modifies a (possibly unexpressed) speech act verb:

(29)

In 29, zusammengefasst lit. ‘summarized’ can be interpreted as modifying an unexpressed performative verb, such as ausgedrückt ‘expressed’ or gesagt ‘said’.Footnote 23 In contrast, PfPs do not lend themselves to an analysis as speech act adverbials. They do not modify speech acts, and they cannot occur with speech-act-denoting verbs.

Moreover, PfPs can occur alone as responses, while this is not possible for a speech act adverbial such as zusammengefasst, as shown in 30: A speech act adverbial must adjoin to a clause.

(30)

Thus, there is clear evidence that the PfP is indeed a verbal participle and not a particle or an adverb.

4.2. The PfP Does Not Have a Reduced Clausal Structure

Performative utterances are typically finite clauses in the present tense (Dahl Reference Dahl2008, Eckardt Reference Eckardt2012:24), and so one could reasonably suppose that the PfP is derived from a finite clause. In fact, Rooryck & Potsma (Reference Rooryck, Potsma and van der Wurff2007:273–274) suggest for performative participles in Dutch that they are underlyingly (dynamic) passives, and Fries (Reference Fries1983:236) suggests for the PfP Abgemacht! ‘Agreed!’ in German that it is underlyingly an adjectival passive. An underlying clausal structure for the PfP would explain the difference in interpretation between performative and directive participles. The performative participle would denote a proposition, while the directive participle denotes a property since it does not have a clausal source (Donhauser Reference Donhauser, Eroms, Gajek and Kolb1984). However, as I demonstrate below, the PfP differs in a number of ways from various finite structures.

Putative clausal sources for the PfP should contain a finite verb in the present tense and a past participle. Given this, some potential finite sources of the PfP Versprochen! ‘I promise!’, with a propositional anaphor or a complement clause, are exemplified in 31. They include the active perfect clause 31a, the werden-passive clause 31b, and the adjectival passive clause in the indicative 31c and in the present subjunctive 31d. Note that the active perfect form habe versprochen ‘have promised’ is included because it satisfies the structural requirement of containing a present tense verb and a past participle, and is possible as a performative utterance. Note also that hiermit appears to be obligatory in 31a,b.

(31)

However, none of the structures in 31 qualify as a clausal source of the PfP. Examples 31a,b must be excluded from the list despite meeting the structural requirements. As far as the active perfect form is concerned, Rapp & Wöllstein (Reference Rapp, Wöllstein, Ehrich, Fortmann, Reich and Reis2009:167), in their discussion of the participle Verstanden! ‘Understood!’, do indeed suggest that when it occurs alone, it is an ellipsis of an active perfect. They observe that an auxiliary can be inserted:

(32)

The verb verstehen ‘to understand’ is not, however, a canonical performative verb, as briefly discussed in section 2, and no insertion of the auxiliary haben ‘to have’ is possible with canonical performative verbs such as versprechen ‘to promise’ or schwören ‘to swear’, as shown in 33.

(33)

There are also other reasons why the active perfect in 31a or the present tense werden-passive in 31b can hardly count as clausal sources of the PfP. Both the active perfect and the werden-passive appear to require the presence of hiermit in order to be interpreted as performatives. Without hiermit the clauses are interpreted as assertions, that is, as a reminder that something has already been promised or that something will be promised.Footnote 25 In 34, B’s answer in the active perfect only seems possible on an assertive reading, and the werden-passive is marginal as a performative.

(34)

Thus, hiermit appears to be necessary to enforce an interpretation of 31a,b as performatives. In contrast, no hiermit is required to enforce the performativity of the PfP, as already mentioned. This difference makes 31a,b unlikely clausal sources of the PfP.

Another important difference between active perfect clauses and werden-passives on the one hand and PfPs on the other is the presence versus absence of genuine reflexives. When participles of reflexive verbs, such as sich schämen ‘to be ashamed’ or sich einigen ‘to agree’, occur in structures that lend themselves to an analysis as an ellipsis—for example, in term answers (Fries Reference Fries1983:53)—they obligatorily retain their genuine reflexives, as shown in 35.

(35)

In contrast, reflexive objects of verbs such as sich anschließen ‘to subscribe to’ and sich einigen ‘to agree’ do not occur in PfPs (or in directive participles, for that matter, as noted in Fries Reference Fries1983:53, Rapp & Wöllstein Reference Rapp, Wöllstein, Ehrich, Fortmann, Reich and Reis2009:168, and Heinold Reference Heinold2013:321). This argument is weakened by the fact that sich anschließen ‘to subscribe to’ and sich einigen ‘to agree’ are judged to be marginal as PfPs by some speakers. Still, when these verbs are used as PfPs, they behave like directive participles formed from verbs with reflexive objects: The reflexive is obligatorily omitted, as shown below.Footnote 26 Example 36 is from a conversation between two participants on a Wikipedia discussion page. Example 37 is from an exchange on an internet forum.Footnote 27

(36)

(37)

Note that in both 36 and 37, the use of reflexives, as in *mich/uns/sich geeinigt and *mich/sich hiermit angeschlossen, respectively, would make the second participant’s response ungrammatical. If PfPs have an elliptical structure, the impossibility of genuine reflexive objects in them is puzzling.

Having ruled out clauses in the active perfect tense and the werden-passives in the present tense as possible clausal sources, let me now consider the adjectival passive in the indicative and present subjunctive. The adjectival passives as performatives, as in 31c,d (Brandt et al. 1990:4, Searle Reference Searle1989:537, Liedtke Reference Liedtke1998:177, Maienborn Reference Maienborn2007:89, Schlücker Reference Schlücker and Fryd2009:109), capture the intuition that the PfP is predicated of the (contextually resolved) internal argument p: With this utterance, the state of p being Ved holds. Since the propositional content is resolved contextually, the putative clausal source can contain a propositional anaphor das ‘that’ as the passive subject, as in 38a, or the pronominal es ‘it’ with an extraposed complement clause, as in 38b.

(38)

From a synchronic point of view at least, there is no direct syntactic relationship between the adjectival passive and the PfP. The ability to form an adjectival passive is not a prerequisite for being able to form a PfP, as verbs that do not form adjectival passives can occur as PfPs. Adjectival passives are formed from verbs with internal arguments (theme or experiencer) (Gehrke Reference Gehrke2015:908–909), but not from verbs with genuine reflexive objects. The verbs sich einigen ‘to agree’ and sich anschließen ‘to subscribe to’ do not form adjectival passives, as shown in 39, but they do occur as PfPs (although, as mentioned above, examples such as 36 and 37 are judged to be marginal by some speakers).

(39)

Interestingly, the adjectival passives of reflexive verbs are better in Heische-clauses, that is, clauses with the verb in the present subjunctive:

(40)

Examples such as 40 are judged to be better than adjectival passives in the indicative in 39, but they are also judged to be somewhat stilted, while the PfPs in 36 and 37 are very colloquial. Moreover, it would be hard to explain why a PfP can only be based on an adjectival passive in the subjunctive, while adjectival passives in the indicative also allow performative readings.

There are also verbs, such as erinnern ‘remind’ in 41, that can form adjectival passives with a performative reading, as in 41a, but fail to occur as PfPs, as shown in 41b. This is unexpected on an analysis of the PfP as an ellipsis, since ellipsis would have to be lexically restricted in these cases.Footnote 29

(41)

Another important difference between the adjectival passive and the PfP is that they do not have the same range of interpretations. The full copula clause in 42 allows for both an assertive and a performative reading. In 42a, the adjectival passive serves as an answer to A’s polar question by asserting that the chancellor’s visit to the opening has been settled. Note that hiermit is excluded here. In 42b, the adjectival passive is used performatively and it serves as an acceptance of an agreement reached by A and B (provided that B is in a position to make arrangements for the chancellor). Here hiermit is possible.

(42)

In contrast, the PfP does not allow for an assertive reading in the context of a polar question, as in 43a. It can only receive a performative reading, as in 43b. If the PfP were an ellipsis of the adjectival passive, the two ought to exhibit the same range of readings.

(43)

Another semantic difference between the adjectival passive and the PfP follows from this distribution of assertive and performative readings. The adjectival passive is ambiguous between having the speaker as the agent on a performative reading or a third party on an assertive reading, as shown in B1’s response in 44, where the third party can be the chancellor herself or her office. The PfP in B2’s response, in turn, is unambiguous. Only the speaker can be the agent, since the sentence only has a performative reading.

(44)

This ambiguity of 44B1 is also found when an adjectival passive is used in reported speech, as mentioned in section 3. The adjectival passive in 45a is ambiguous: It can either mean that someone else has promised Peter a compensation or that Peter has promised the hearer that he, Peter, would get a compensation. The PfP in 45b cannot mean that some third party has promised Peter a compensation. The speaker may utter this sentence to assure the hearer that Peter said so; it could also mean, albeit only marginally, that Peter promised the hearer that he would get a compensation.Footnote 30 As an elliptical variant of an adjectival passive with a subjunctive, one should expect the response in 45b to be ambiguous as well, but it is not.Footnote 31

(45)

Thus, the PfP and the adjectival passive have distinct syntactic and semantic properties which may not be explained if the former is an ellipsis of the latter.Footnote 32

Note that the PfP is also different from evaluative adjective phrases occurring in root positions, discussed by Günthner (Reference Günthner, Günthner and Bücker2009). Consider example 46.

(46)

The PfP appears to share many properties with this construction: The evaluative adjective can occur alone leaving the clausal complement (what is considered great in 46) to be resolved contextually; the adjective shows speaker orientation, that is, the evaluator is understood to be the speaker (even though the adjective has no agent argument). However, the evaluative adjective in 46 is interpreted assertively, while the PfP does not allow for an assertive reading. Also, the evaluative construction allows for evaluative expression of various categories (Günthner Reference Günthner, Günthner and Bücker2009:178–179), as in 47a.Footnote 33 In contrast, the PfP does not seem to alternate with performative expressions of other categories, as shown in 47b.

(47)

Günthner (Reference Günthner, Günthner and Bücker2009) argues that the adj+dass-clause construction is not a reduced clausal structure. Neither is the PfP, but they are different constructions.

5. The Syntax of the PfP

5.1. The Argument Structure of PfP Verbs

Two questions present themselves concerning the syntax of the PfP: How are the arguments of the input verb expressed and what is the constituent structure of the PfP? The verbs occurring as PfPs do not form a homogeneous group from a syntactic point of view. The only common property appears to be that they are at least two-place predicates. As a minimum, the verbs select an agent (the speaker) and allow a propositional argument, namely, what is communicated in the denoted speech act: what is promised, admitted or agreed upon.Footnote 34 The attested verbs occurring in PfPs all allow for a complement clause with the complementizer dass ‘that’. Verbs selecting a complement clause with the complementizer ob ‘if/whether’ appear to be excluded from the PfP. The restriction to the complementizer dass follows from the fact that the speaker commits to the truth of a proposition, while the complementizer ob is used for embedded clauses with an unresolved truth value (Zifonun et al. Reference Zifonun, Ludger and Bruno1997:2258). This contrast is illustrated in 48a,b versus 48c,d.

(48)

Otherwise, a variety of complementation patterns is observed for the verbs occurring as PfPs:

(i) NPACC+NPDAT: jmdm. etw. bestätigen ‘to confirm sth. for sb.’, gestehen ‘to confess’, schenken ‘to grant’, versichern ‘to assure’, versprechen ‘to promise’, zugeben ‘to admit’

(ii) NPDAT/NPDAT+PP: etw.D zustimmen ‘to agree to sth.’, jmdm. (darin) zustimmen, dass … ‘to agree with sbd. in sth.’

(iii) NPACC: akzeptieren ‘to accept’, verstehen ‘to understand’, kapieren ‘to understand’

(iv) NPACC+(comitative) PP: etw. (mit jmdm.) abmachen ‘to agree’, etw. (mit jmdm.) vereinbaren ‘to agree on sth.’

(v) NPREFL+NPDAT/NPREFL+NPDAT+dass-clause: sich etw.D anschließen ‘to subscribe to sth.’, sich jmdm. anschließen, dass … ‘to accord with sb. that …’

(vii) NPREFL+PP+(comitative PP): sich (mit jmdm.) über etw. einigen ‘to agree on sth.’

It is striking that some of these verbs—for example, abmachen ‘to agree’ and sich einigen ‘to agree’—alternate between taking a plural subject and occurring with a comitative mit ‘with’-phrase. This accords well with the generalization that the PfP is used to express consent.

5.2. Expression of the Agent

Past participles occur in both active and passive constructions. Müller (Reference Müller2002:146–148), building on a proposal by Haider (Reference Haider1986), suggests that past participles block the designated argument of the verb (the argument with subject properties). An auxiliary such as haben ‘to have’ deblocks the designated argument to form a composite active tense, as in 49a, while an auxiliary such as werden lit. ‘to become’ realizes the second most prominent argument (in the accusative case in 49a) as the subject of a passive, as in 49b. The blocked external argument can be realized as an oblique by-phrase.

(49)

Unlike directive participles, which allow (quantificational) subjects (Fries Reference Fries1983:52, Rapp & Wöllstein Reference Rapp, Wöllstein, Ehrich, Fortmann, Reich and Reis2009:168, Gärtner 2013:204, Heinold Reference Heinold2013:316; see 8a above), PfPs do not allow the agent to be realized as a nominative subject, as shown in 50a. Even more puzzling is that the PfP does not seem to occur with an oblique by-phrase either, as illustrated in 50b. An oblique by-phrase appears to be better than a nominative subject, but no authentic examples have been found.

(50)

As discussed in section 3, speaker restriction is a defining characteristic of performatives. In an active performative, the subject is a 1st person pronoun (or a DP denoting the speaker, such as der Unterzeichnete ‘the undersigned’).Footnote 35 In a passive performative, the (unexpressed) agent is understood to be the speaker, as in 51 (from Brandt et al. 1990:4).

(51)

Given that performatives are speaker-oriented, any overt realization of the agent appears to be redundant unless it is independently required by the syntax, for example, when an active verb requires a subject. Still, avoidance of redundancy cannot be the explanation for why agent phrases are hardly ever seen in the PfP. Syntactically, overt agents are possible in performative adjectival passives, as in 52, even though they are syntactically optional. The by-phrase in 52 is redundant and is not required by the syntax.

(52)

Moreover, the agent would not be redundant in delegated speech, where the speaker has been authorized to perform the speech act on behalf of someone else. Yet agent phrases, as in the constructed example 53, are hardly ever found in the PfP.

(53)

Still, given the fact that an oblique by-phrase is much better with the PfP than DP subjects and even appears to be accepted by some speakers, I assume that the PfP has a passive argument structure and that the agent is linked to an oblique by-phrase.Footnote 37 Since the oblique by-phrase (the agent) in the canonical use of the PfP is fully interpretable as the speaker, I suggest that this by-phrase is restricted to be a null pronominal in the 1st person (ignoring delegated speech, as in 53B). The presence of a null pronominal excludes overt realization of the argument. For those speakers who do accept an overt by-phrase, the restriction that it be a null pronominal is optional. I account for the optionality of this restriction in the analysis below.

5.3. Expression of Internal Arguments

The PfP licenses only one kind of internal argument, namely, the recipient argument. Though rarely seen, internal recipient arguments are typically realized as dative objects, as was already shown in section 4.1. The relevant examples are repeated in 54.

(54)

Reflexive objects are barred from occurring (see examples 36 and 37), as also observed for directive infinitives and participles in Fries Reference Fries1983:53–54, Gärtner 2013:206, and Heinold Reference Heinold2013:321.

What is more puzzling is why the PfP does not license internal propositional arguments as overt anaphors, as in 55a,b, or as pronominal adverbs, as in 55c.

(55)

From a syntactic point of view, it is not clear why the PfPs in 55 are ruled out. In general, participles do license internal arguments either as complements inside the VP or as accusatives in a small clause, the so-called absolute accusative with the accusative corresponding to a passive or unaccusative subject (Fabricius-Hansen et al. 2012:80ff., Zifonun et al. Reference Zifonun, Ludger and Bruno1997:2225). In the discussion of the expression of the agent in section 5.2 it was suggested that the PfP has a passive argument structure. Thus, the structure in 56 ought to be available for the PfP with an internal argument linked to the subject (a passive subject) but it is not, as 55a shows.Footnote 41

(56)

Even if the small clause structure in 56 were available for PfPs with passive subjects (that is, for PfPs derived from verbs that take objects with accusative case), it would not be available for the PfPs derived from verbs with dative-marked objects and prepositional objects, as in 55b and 55c, respectively, since dative and prepositional objects cannot be construed as passive subjects. However, dative and prepositional objects should be able to occur VP-internally, as in the structure in 57, but they cannot, as 55b,c show.

(57)

It should be noted that past participles with internal arguments expressed as nominative subjects are observed in root position in small clause structures, like the ones in 58 (see also Fries Reference Fries1983:52). These clauses appear to be instances of the so-called absolute nominative construction as the adjective ending in 58c shows (case cannot be determined for 58a and 58b). This construction is only possible with verbs selecting accusative complements.

(58)

I do not consider these examples instances of the PfP though. Fries (Reference Fries1983:236) and Fabricius-Hansen et al. (2012:84) suggest that absolute nominatives are clausal; more specifically, the nominative is the subject of an elliptical finite verb. More importantly, the absolute nominatives shown in 58 are special in that they lack a determiner (see Fries Reference Fries1983:53, who speaks of determiner ellipsis in conjunction with directive participles). As illustrated in 59, if the nominative subject is a definite DP, the acceptability of such examples decreases.

(59)

The impossibility of a definite DP is incompatible with the very nature of the PfP: In the PfP, what is promised or agreed on is contextually resolved, so it must be represented by a propositional anaphor such as das ‘that’ or dies ‘this’ and not a determinerless NP. Also, the analysis of the PfP as an ellipsis of the absolute nominative would not explain why PfPs can be derived from verbs with dative and prepositional objects. As mentioned, only verbs with accusative objects occur in constructions such as 58.

Since the propositional argument in the PfP is fully interpretable but cannot be overtly realized, I suggest that it is a (propositional) null pronominal, which is left to anaphoric resolution. This view of the propositional argument still leaves a problem, though. Occasionally the PfP allows for an extraposed complement clause, as in 60.

(60)

One way of explaining the data in 60 is to propose that the PfP does not allow overt definite complements. The clause in 60 is licensed because it is not marked for definiteness. However, this would require one to explain why complements marked for definiteness are barred from occurring. Verbs selecting complement clauses usually also allow propositional anaphors such as das ‘that’ or dies ‘this’ to replace the clause.

As an alternative analysis, I suggest that the internal argument of the PfP in 60 is also a null pronominal and that the extraposed dass-clause restricts the interpretation of the null pronominal as in the analysis of correlative es in German in Berman et al. Reference Berman, Stefanie, Christian, Jonas, Butt and King1998. An argument in favor of this analysis of 60 is that a null pronominal (just like an overt pronominal) is anaphorically dependent on an antecedent. The extraposed dass-clause restricts the interpretation of the null pronominal to an already given discourse entity; in other words, the dass-clause provides background, or discourse-old information, as argued for dass-clauses with an overt pronominal es ‘it’ in Berman et al. 1998:13. Since the PfP is typically used to express consent, what is agreed upon is expected (or presupposed) to be present in the discourse, as also observed for the evaluative adj+dass-clause construction (Günthner Reference Günthner, Günthner and Bücker2009:159). This analysis is further supported by the fact that in dialogical contexts, PfPs are infelicitous with discourse-new propositional content in the dass-clause, as shown in 61B2.

(61)

In a monological use such as the one in 60, the content of the dass-clause does not belong to old discourse strictly speaking; but still the PfP can be replaced with Stimmt! ‘That’s right!’, as if the speaker is reacting to an anticipated objection from the hearer.Footnote 45 I return to this effect of PfPs in section 9.

The construction with a PfP and an extraposed dass-clause in 60 behaves just like clausal structures with an overt pronoun es, as in 62.

(62)

The construction in 62 is an instance of the so-called correlative es construction in German (see, among others, Cardinaletti Reference Cardinaletti1990; Berman et al. 1998; Sudhoff Reference Sudhoff2003, Reference Sudhoff, Frey, Meinunger and Schwabe2016), where a sentence-internal nominal proform es ‘it’ is coreferential with a complement clause in the extraposition. The PfP construction behaves just like the correlative construction. The correlative construction does not allow the clause to appear preverbally, as 63a shows (Berman et al. 1998:5–6, Sudhoff Reference Sudhoff2003:55, Sudhoff Reference Sudhoff, Frey, Meinunger and Schwabe2016:24), which is also observed in the PfP construction in 63b. This restriction is explained if the PfP contains a correlative null pronominal.

(63)

On the analysis of the extraposed clause as restricting the interpretation of a null pronominal it is unexpected that PfPs also occur with V2-clauses, as in 64.Footnote 47 Correlative es does not occur with extraposed V2-clauses (Sudhoff Reference Sudhoff, Frey, Meinunger and Schwabe2016:35).

(64)

However, verbs occurring with correlative es also occur in a construction with an anticipatory pronominal es and a V2-clause that is not syntactically subordinate to the main verb, as in 65. In these examples, there is an intonational break before the V2-clause, and sometimes a colon is used, as in 65b, instead of a comma, as in 65a.

(65)

Whatever the analysis of these constructions, the PfP behaves exactly like verbs with an anticipatory es, which lends support to positing a null pronominal in PfPs, including constructions where the PfP is followed by a subordinate dass-clause as in 60 or a V2-clause as in 64.

To sum up the discussion in this section, the PfP licenses only internal recipient arguments. As for the impossibility of realizing the agent and the internal propositional argument, I suggest that they are constructionally restricted to null pronominals.

5.4. The Constituent Structure of the PfP

As far as the constituent structure of the PfP is concerned, there is very little to go by. There is evidence that the PfP projects a VP: As shown in sections 4.1 and 5.3, the PfP licenses VP-internal recipient arguments, possibly oblique by-phrases, and manner adverbials (following Pittner Reference Pittner, Jennifer, Engelberg and Rauh2004:260, manner adverbials are adjoined to the verbal complex, that is, they are VP-internal).

However, there is also evidence that the PfP contains an IP above the VP. For example, the PfP allows for (evaluative) sentential adverbials such as leider ‘sadly’ or selbstverständlich ‘naturally’, as in 66.

(66)

There are reasons for believing that these sentential adverbials adjoin to IP. If they could adjoin to VP, they would be expected to occur in small clauses, such as absolute accusatives, as in 67, but they cannot. The marginality of 67 is explained if the absolute accusative contains a VP and not an IP.

(67)

Note that in addition to supporting the existence of an IP projection in PfPs, evaluative sentential adverbials also provide further evidence that the PfP cannot be a small clause occurring in root position with an empty DP (see discussion in section 5.3). The structure would be that of an absolute accusative, as in 68a, but with an empty DP, as shown in 68b.

(68)

Thus, the occurrence of sentential adverbials provides evidence that the PfP is not a small clause and, furthermore, that it is an IP. If sentential adverbials adjoin to IP or I', a PfP with a sentential adverbial has the structure in 69.Footnote 50

(69)

There is yet another syntactic property of the PfP that must be explained, namely, PfPs cannot be embedded. This is surprising because other types of performative expressions can (Brandt et al. Reference Brandt, Gabriel, Norbert, Frank, Jörg, Günther, Helmut and Inger1990:16–17). The PfP can only occur unembedded, as also noted for evaluative copula-less clauses (Müller Reference Müller, Finkbeiner and Meibauer2016:88). If a past participle of a speech-act-denoting verb is syntactically embedded, it can only be understood assertively. For example, conjunctions such as weil ‘because’ and obwohl ‘although’ can be followed by a finite clause, as in 70a, as well as a past participle, as in 70b (or an adjective; Breindl Reference Breindl, Konopka and Schneider2012, Ørsnes Reference Ørsnes2017). The finite clause in the weil-clause in 70a can be understood as a performative, while the past participle following weil in 70b can only be understood as an assertion: because it has been confirmed. Note that the weil-clause is syntactically integrated, being in the prefield. In this position, weil ‘because’ cannot be followed by root clauses, such as V2- or imperative clauses (Reis Reference Reis2013:228).

(70)

To explain why the PfP cannot be syntactically embedded I suggest that it has the category IProot. This gives one the structure of a simple PfP in 71a, and the structures of a PfP with an internal dative argument and a manner adverbial in 71b and 71c, respectively.

(71)

To sum up, the PfP is proposed to have the following syntactic properties: It is an IProot dominating a VP; the agent of the past participle is (canonically) a 1st person null prominal, and the internal propositional argument a null pronominal to be resolved contextually.

6. An Account Within Lexical-Functional Grammar

LFG posits two levels of syntactic representation: a c(onstituent)-structure and a f(unctional)-structure (Bresnan Reference Bresnan2001, Dalrymple Reference Dalrymple2001). The c-structure represents the constituent structure with hierarchical relations and linear precedence. The f-structure represents—among other things—the grammatical relations between the syntactic constituents, that is, the predicate-argument relationships. There is no one-to-one relationship between the c-structure and the f-structure. The f-structure can contain elements that are not explicitly represented in the c-structure. For example, null pronominals are present as elements in the f-structure but have no formal expression in the c-structure. This is exactly what can be claimed to hold for the PfP. There are no nodes in the c-structure corresponding to the agent or the propositional argument of the PfP Versprochen! ‘I promise!’. Still, the oblique by-phrase and the propositional argument are present in the f-structure as selected grammatical functions with a semantic representation as pronominals. The attribute pred represents the semantic form, and [pred ‘pro’] means that the grammatical functions in question are interpreted as pronominals that are resolved contextually. Since they have no expression in the c-structure, the pred-specifications have to be added constructionally.Footnote 51 For the PfP Versprochen! ‘I promise!’ I propose the following c- and f-structures:

Figure 1. C- and f-structures of the PfP Versprochen! ‘I promise!’.

The c-structure is very simple: It is merely an IProot dominating a VP. The f-structure shows that the main predicate is versprechen ‘to promise’, which selects a (passive) subject, an oblique by-phrase, and a dative object. All selected grammatical functions are pronominals, with the by-phrase restricted to the 1st person. As for the dative object of versprechen ‘to promise’, I assume that it is always restricted to the 2nd person when omitted in a performative sentence (as in Ich verspreche (dir), dass ich komme ‘I promise (you) that I will come’). The f-structure further shows that the clause is a performative and that the specific speech act denoted by the verb belongs to a type of speech act expressing consent. The distinction between illocution and speech act type is intended to account for the fact that a performative utterance such as Versprochen! ‘Promised!’ creates a linguistic fact, which is, in itself, a speech act (Searle Reference Searle1989:549). I return to the pragmatics of PfPs in section 7 and further justify the view that PfPs are pragmatically restricted.

The c- and f-structures are licensed by the (simplified) c-structure rule with functional annotations in figure 2.Footnote 52 This rule, in combination with the lexical entry for the passive past participle versprochen ‘promised’ in figure 3 and a VP-rule, which is not given, license the c- and f-structures above.Footnote 53

Figure 2. C-structure rule with functional annotations for the PfP.

Figure 3. Lexical entry for the (passive) past participle of versprochen ‘promised’.

In figure 2, the f-structure associated with IProot is the same as the one associated with VP. The speech act type is constrained to express consent,Footnote 54 while the illocutionary force of the speech act is performative. The oblique agent is in the 1st person (that is, the speaker). Brackets indicate optionality: The oblique agent is identified as a (null) pronominal, unless an overt pronominal has contributed the specification [pred ‘pro’] (von mir bestätigt). Curly brackets indicate disjunction with | separating the disjuncts: The propositional argument of the consent verb is a pronominal linked to a (passive) subject, a dative object or an oblique object (a prepositional object) of the participle. The verbal head is a past participle, and the verbal head is passive.

The crucial point in the LFG account presented here is that this particular configuration of an IProot dominating a VP headed by a past participle of a verb semantically typed to denote a speech act expressing consent (in a broad sense) allows one to constructionally specify the pronominal elements and the illocutionary force. The result is the clausal f-structure given in figure 1.

7. The PfP as an Expression of Consent

In a performative utterance, the type of speech act performed—that is, a promise, an order, a request etc.—is determined by the performative verb. The PfP allows for a variety of different verbs, but they can all be subsumed under the heading of consent. They confirm a statement, for example, einräumen/zugeben ‘to admit’, gestehen ‘to confess’, schenken ‘to grant’, and zustimmen ‘to agree on’, or agree to comply with a request, for example, abmachen ‘to agree’, akzeptieren ‘to accept’, kapieren ‘to understand’, vereinbaren ‘to agree on’, versprechen ‘to promise’ or verstehen ‘to understand’. In this section, I elaborate on this characterization of the PfPs; I show that they are used as supporting responding speech acts and that this explains why they alternate with the response particle Yes! (or No! as a response to a negative statement). At the same time, they are only felicitous if the hearer is committed to the content under discussion, either by claiming it to be true or by wanting it to be true. I suggest that these properties serve as a characterization of consent. Finally, I briefly demonstrate how PfPs —just like response particles—are found in monological uses for special rhetorical purposes.

7.1. The PfP and Responding Supporting Speech Acts

Eggins & Slade (Reference Eggins and Slade1997:183) present the following classification of speech acts adapted from Halliday Reference Halliday1994.Footnote 55 The grey-shaded cells indicate contexts, where the PfP is found, as I show in the following.

Eggins & Slade (Reference Eggins and Slade1997) distinguish between initiating speech acts and responding speech acts. As the examples in 72a,c,e illustrate, performative verbs that denote initiating speech acts—here mitteilen ‘to tell’, befehlen ‘to give orders’, and fragen ‘to ask’—are possible in finite performative utterances. However, these verbs are problematic as PfPs, as shown in 72b,d,f.Footnote 57

(72)

As mentioned in section 2, participles that denote initiating speech acts only seem to be possible if accompanied by hiermit ‘hereby’ or with the right prosody (and gesture) forcing a performative reading, as in 73a.Footnote 59 In the absence of hiermit, the addition of an adjunct, as in 73b, or an internal argument, as in 73c, improves a PfP that denotes an initiating speech act considerably, but why such improvement is possible is unclear (in fact, the participle can be left out in 73b).

(73)

The canonical PfPs, as in 74B, are used to perform responding speech acts, and as such they belong to the inventory of linguistic feedback. This is the reason why they alternate with Ja!, which is used as a response to utterances that perform initiating speech acts (among many other functions of Ja!; see, for example, Hoffmann Reference Hoffmann2008).

(74)

As the PfP is used in a responding speech act, it needs a supporting context for its interpretation. This requirement is not unique to PfPs but applies to other response expressions as well. For example, the response particle Ja! is inherently anaphoric (Krifka Reference Krifka and Machicao2014). Similarly, Holmberg (Reference Holmberg2013:31) proposes in his analysis of English and Swedish that answers to polar questions are sentential structures, where the IP (the propositional content) is inherited from the question and then elided. This is parallel to the PfP, where the argument of the speech act verb is also missing. I do not assume any deletion though. The argument is analyzed as a pronominal, as detailed in section 5.3.

As shown in table 2, responding speech acts are either supporting or confronting. Through supporting speech acts the speaker acknowledges statements, agrees to comply with requests or provides answers to questions. Through confronting speech acts the speaker contradicts statements, refuses to comply with requests or provide answers to questions. Examples of speech act verbs used to perform confronting speech acts are bestreiten ‘to dispute’, widersprechen ‘to contradict’, leugnen ‘to deny’, sich weigern ‘to refuse’ or sich wehren ‘to resist’. These verbs do not occur as PfPs, at least not without a supporting hiermit.Footnote 63 In 75a and 75b, speaker B expresses disagreement and refusal, respectively. Note that the response particle Nein! ‘No!’ is acceptable in these examples.

Table 2. Speech act pairs (Eggins & Slade Reference Eggins and Slade1997:183).Footnote 56

(75)

Of course, whenever a PfP alternates with Ja!, it is used to perform a responding supporting speech act. Note that the PfP can alternate with the negative response particle Nein! if the latter is used to indicate agreement with a negative statement, as in 76a. The examples in 76 illustrate that the response particle is polarity based (Holmberg Reference Holmberg2013:32), while the PfP is truth based.

(76)

The PfP is not only used to perform supporting speech acts; given that agreement or consent is generally assumed to be a preferred next action (Pomerantz Reference Pomerantz, Maxwell Atkinson and Heritage1984:63–64), the PfP also represents a preferred conversational move.

As mentioned in note 10 (section 2), the PfP Abgelehnt! ‘Denied!’ is a notable counterexample to the claim that PfPs can only be derived from verbs of support or approval, which are associated with the supporting speech acts. This PfP is found in legal language but also in informal discourse to reject a proposal, as noted by a reviewer. I propose the following explanation. Verbs of approval such as stattgeben/genehmigen ‘to approve’ can occur negated in performative contexts: Nicht stattgegeben! ‘Not approved!’ The verb ablehnen ‘to deny’ is synonymous with such negated uses. This semantic similarity could have paved the way for the verb expressing refusal (that is, the verb associated with the confronting speech act) to be used as a PfP. This counter-example, however, should not overshadow the rather striking generali-zations that can be made about the use of PfPs as expressions of consent.

Note, however, that PfPs do not occur in all instances of supporting speech. While PfPs do occur as responses to statements and requests, they do not occur as answers to polar questions. German has two verbs meaning ‘to affirm’ and ‘to deny’, namely, bejahen and verneinen. These verbs cannot occur as PfPs in answers to polar questions, just like the verb bestätigen ‘to confirm’.Footnote 65

(77)

The difference between statements and requests on the one hand and questions on the other lies in the expected response. Statements and requests create a positive bias on the part of the hearer, who knows that the speaker anticipates agreement. In contrast, although questions imply an answer, they do not create a positive bias toward a particular answer (Farkas & Bruce Reference Farkas and Bruce2010:96).Footnote 66 A statement or a request commits the speaker in a way that a question does not. By making a statement the speaker commits to the truth of the statement, and by making a request the speaker commits to an interest (in a broad sense) in having the hearer comply with the request (Condoravdi & Lauer Reference Condoravdi, Lauer and Piñón2012:41ff.). This commitment is a prerequisite for confirmation: The hearer must confirm something that the speaker has already committed to herself. In contrast, it is not possible to confirm a question, only to provide an answer. For the response PfP(p) to be successful, the hearer must have committed herself to p.

To sum up, the PfP is a supporting response to an assertion or a request, where the hearer is already committed to p. p is eventually added to CG. I take this to be a characterization of consent.

7.2. The PfP as Confirmation of an Assertion

In 78, speaker B confirms the statement made by speaker A. This is the prototypical instance of consent, where A and B both commit themselves to the same assertion.

(78)

Verbs found in this context include bestätigen ‘to confirm’, zugeben/ einräumen ‘to admit’, sich einigen/zustimmen ‘to agree’, sich anschließen ‘to subscribe to’, garantieren ‘to guarantee’, schenken ‘to grant’, and gestehen/eingestehen ‘to confess’. On the analysis in Farkas & Bruce Reference Farkas and Bruce2010, speaker A publically commits to the truth of the proposition: The meeting was very successful. Speaker B confirms the truth of this proposition and publically commits herself to its truth as well. Eventually the proposition is added to CG. As confirmation of a statement, the PfP alternates with the expression Stimmt! ‘That’s right!’, which presupposes that speaker A has already committed to the truth of the proposition. Therefore, Stimmt! has a more restricted use than Ja!: Stimmt! does not occur as an answer to polar questions, as shown in 79b.

(79)

There is a difference between the response expression Stimmt! and the PfP though. The expression Stimmt! can be used as an answer to a question about an observable fact with the paraphrase ‘I know’, as in 80a. In contrast, the PfP is only felicitous in a context where a diverging opinion is easier to imagine as, for example, in the response to the assessment in 80b, or where an observable fact is somehow unexpected, as in 80c.

(80)

Farkas & Bruce (Reference Farkas and Bruce2010) only consider assertions expressed by declarative sentences. They do not account for nondeclarative sentences denoting—or presupposing—propositions. In the canonical case, a PfP occurs as a response to a declarative clause, as in 80b. However, a PfP can also serve as a response to other sentence types provided they introduce a proposition belonging to speaker A’s discourse commitments. In 81, the PfP is a response to an exclamative clause.

(81)

Exclamative clauses express the speaker’s attitude to a particular proposition, for example, that something is surprising or noteworthy (Zanuttini & Portner Reference Zanuttini and Portner2003). In 81, the exclamative clause presupposes that B has (in A’s opinion) indeed eaten a lot (Michaelis Reference Michaelis, Haspelmath, König, Oesterreicher and Raible2001, Zanuttini & Portner Reference Zanuttini and Portner2003). In uttering an exclamative, speaker A publically commits to the proposition that is considered noteworthy. Speaker B can confirm this proposition thereby making it a member of CG. The crucial condition for the use of the PfP is that p already belongs to speaker A’s discourse commitments. Speaker B subsequently confirms p.

In addition to this canonical use of the PfP—that is, as a positive response to an assertion—there are (at least) two other uses in which the PfP does not alternate with the expression Stimmt! The first one concerns the commitment of speaker B to p expressed by speaker A. Farkas & Bruce (Reference Farkas and Bruce2010) only consider confirmation and rejection as possible reactions to an assertion (the answers Yes! and No!). There is also a third possibility, namely, that B neither confirms nor contradicts a statement by A but simply acknowledges a statement or the fact that A is uttering a particular statement (see also Allwood et al. 1992:17). Linguistically such a response is signaled by the feedback items Ach so! ‘Really!’, Aha! or Verstehe! ‘I understand!’. The PfP is also found in this context, as shown in 82, which contains the complex verb zur Kenntnis nehmen ‘to take note of something’.

(82)

This use of the PfP differs from the canonical confirmation of an assertion in not being supporting. The speaker does not confirm p, and p cannot be added to CG. Only the fact that A holds this opinion can be added to CG.

Second, the PfP can also be used in a situation when p is part of B’s discourse commitments and A asks whether p can indeed be added to CG—or, if p is already part of CG, whether it should be kept in CG. In this case, the PfP is a response to an incredulous question biased toward a particular answer. PfPs that appear in this context include Versprochen! ‘I promise!’, Geschworen! ‘I swear!’ or Versichert! ‘For sure!’:

(83)

This use of the PfP is similar to the confirmation use discussed above, but A does not make a public discourse commitment.

7.3. The PfP as Agreement to Comply with a Request

PfPs are also formed from verbs that express agreement/readiness to comply with a request (in a broad sense) made by the hearer. These are verbs such as abmachen/vereinbaren ‘to agree’, akzeptieren/annehmen ‘to accept’, verstehen/kapieren ‘to understand’, versprechen ‘to promise’, as shown in 84 where B confirms the agreement.

(84)

Just like the PfP that confirms a statement, the PfPs in 84 perform a responding supporting speech act; they are also positively biased as speaker A has an interest in speaker B’s fulfilling the request. On the face of it, this use is much like the confirmation of a statement: B confirms a statement made by A. However, there is a difference: B commits herself (and sometimes also A) to some future action. This difference is reflected in the range of possible response particles alternating with the PfP. The PfP alternates with Ja! as expected, but it does not alternate with Stimmt! Instead, it alternates with the particle Okay! or Jawohl! ‘Yes, Sir!’ depending on B’s evaluation of the strength of the request:

(85)

This use also shows a clear bias toward a positive response. By making a request A performs a directive speech act wishing for the proposition expressed by the directive sentence to come true (Searle Reference Searle1976:11, Condoravdi & Lauer Reference Condoravdi, Lauer and Piñón2012:41ff.). By uttering a PfP such as Abgemacht! ‘Agreed!’ or Versprochen! ‘I promise!’, B commits to making a particular state of affairs a reality, which results in A and B sharing a goal. Similarly, the confirmation of an assertion results in A and B sharing an assumption.

Requests can be made in a variety of ways: Declarative clauses, questions, imperative clauses, and cohortatives can all be used to perform directive speech acts. The example in 85 and the example in 86 below (repeated from 15) illustrate declaratives understood as requests.

(86)

Interestingly, PfPs are also possible as answers to polar questions, if a polar question is interpreted as a request, as in 87, and not as a polar (information seeking) question.

(87)

Taken out of context, speaker A’s question in 87 can be interpreted either as a polar question or as a request. The response shows that speaker B chooses to interpret it as a request and to commit to the goal suggested by A. The PfP is also felicitous as an answer to polar questions where A explicitly asks B to make a commitment by including the performative verb in the question, as in 88.

(88)

As expected, however, PfPs are not possible as answers to true information seeking questions, as mentioned earlier. In the following examples, the modal particle denn, which only occurs in syntactically interrogative clauses (Reis Reference Reis2003:165), and the adverb überhaupt ‘at all’ invite an interpretation as a polar question rather than as a request.

(89)

The PfP is also felicitous as a response to a declarative clause interpreted as a question, usually due to a rising intonation (Niebuhr et al. 2010), as in 90a. Here the answer does not provide new information, but rather confirms a commitment that has already been under discussion, the so-called question of confirmation (Nachfrage or Bestätigungsfrage, Zifonun et al. Reference Zifonun, Ludger and Bruno1997:643). The PfP is also felicitous in cohortatives asking for mutual agreement, as in 90b. Here both A and B commit to (common) future action. Finally, as a response to an imperative, the verbs verstehen and kapieren ‘to understand’ are possible, as in 90c.

(90)

Verstehen and kapieren are not, strictly speaking, performative verbs. They are only used as performative verbs as past participles, as mentioned in section 2.

8. An Account Within the Framework of Farkas & Bruce Reference Farkas and Bruce2010

In this section, I propose an account of the essential features of the pragmatics of the PfP, namely, that it is used to perform a responding supporting speech act, which presupposes a positive bias on part of the hearer. The account is modelled in the conversational framework proposed by Farkas & Bruce (Reference Farkas and Bruce2010) in their analysis of responses to assertions and polar questions.

8.1. The PfP as Response to Assertions

Table 3 depicts the conversational state after A has uttered the sentence Die Sitzung war sehr gelungen ‘The meeting was very successful’, in the framework of Farkas & Bruce Reference Farkas and Bruce2010. By making this assertion, interlocutor A places a syntactic object in the form of a declarative sentence (D), paired with its denotation p, on the Table that contains what is referred to as the question under discussion in other frameworks (Farkas & Bruce Reference Farkas and Bruce2010:86). At the same time, A publically commits to the truth of the assertion. This is shown by including denotation p among A’s Discourse Commitments (the cell right under A). At this point, p is not yet a mutual assumption and therefore not yet a member of CG.Footnote 68 Every move to put an item on the Table is associated with a preferred reaction, represented in the projected set, that removes this item and thus empties the Table. For example, an assertion made by A can be confirmed, rejected, elaborated or questioned. The projected set, however, shows that the preferred responding move is to confirm the assertion and add it to CG.

Table 3. Conversational state after A has uttered an assertion.

By responding with a PfP such as Zugestimmt! ‘I agree!’ or Zugegeben! ‘Granted!’ at this point of the conversation, B maps the context in table 3 to the output context depicted in table 4.

Table 4. Conversational state after B has confirmed A’s assertion.

In the output context, B confirms the proposition and p is added to B’s discourse commitments, in accordance with the preferred move. Consent is obtained since the proposition p belongs to the discourse commitments of both interlocutors. Farkas & Bruce further assume a common ground increasing operation (Farkas & Bruce Reference Farkas and Bruce2010:99), which moves a proposition on the discourse commitment list of both interlocutors to CG. The resulting conversational state is depicted below:

Table 5. Conversational state after p has been added to CG.

The conversational states illustrate the three crucial features of the PfP: First, the PfP is responding in that it targets the top-most element on the Table; second, the PfP is supporting in that it confirms A’s discourse commitment, that is, it represents the preferred conversational move in the projected set; and third, the PfP expresses p that belongs to A’s discourse commitments.

8.2. PfPs as Response to Directives

Farkas & Bruce (Reference Farkas and Bruce2010) deal with Yes! only as a response to assertions and polar questions, not as a response to requests. In this section, I show how the PfP as a response to a request can be accommodated within the conversational framework of Farkas & Bruce. An elaborate discussion of the representation of imperatives or directives in general is beyond the scope of this paper, and many problems are sidestepped. The goal is to show what it means, within this conversational framework, to reach a consensus and to illustrate why PfPs cannot serve as responses to (information seeking) polar questions. For ease of exposition, I restrict myself to directives expressed by imperatives. I do not try to account for indirect speech acts, where a directive is expressed by a V2-clause, a V1-question or a V2-question, as in 86, 87, and 90a, respectively.

An approach to directives that requires no major extensions to the framework of Farkas & Bruce Reference Farkas and Bruce2010 is to follow the analysis of imperatives in Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann2012 and treat directives as (modalized) propositions. Kaufmann (Reference Kaufmann2012:59ff.) proposes that an imperative sentence such as Go home! can be semantically represented as the (deontically) modalized proposition You should go home, where the modal verb is understood as a performative modal (in contrast to a descriptive modal). The imperative in 91a has the semantic paraphrase in 91b on this approach.

(91)

The paraphrase in 91b is represented as H-should-P, where P is the property of being ready and H is the hearer.

By treating imperatives as modalized propositions, one can treat directives along the lines of assertions in the framework of Farkas & Bruce Reference Farkas and Bruce2010. By uttering a directive such as Halten Sie sich bereit! ‘Please, be ready!’ in 92, speaker A makes a public commitment to the modalized proposition: The hearer should be ready. This formally captures the speaker’s endorsement, as in Condoravdi & Lauer Reference Condoravdi, Lauer and Piñón2012, namely, that the speaker has an interest (in a broad sense) in the coming about of what is denoted by the imperative clause. The imperative sentence and its denotation are added to the Table along with the projected set, that is, the preferred conversational move, namely, that speaker B confirms this proposition so that its denotation is added to CG. By confirming a modalized proposition with a PfP such as Verstanden! ‘Got it!’, speaker B agrees to comply with the request denoted by the imperative sentence, as shown in table 7. This is the only difference between confirming an assertion and responding positively to a request: The latter commits the speaker to future action.

Table 6. Conversational state after A has uttered a request.

Table 7. Conversational state after B has responded with a PfP.

Table 8. Conversational state after request has been accepted by B and added to CG.

(92)