A BRIEF HISTORY OF COLLECTIONS, COLLECTORS, AND ACADEMIC ARCHAEOLOGY IN URUGUAY

Uruguay has a long history of collection (mid-nineteenth century) if we compare it with the recent beginning of professional archaeology (1976). The first known collection of archaeological objects and fossils was built up by Charles Darwin in 1832 during his visit to this part of the world. The collection, following the colonialist model of that time, was destined for the British Museum. It is important to highlight that Darwin not only made this archaeological collection but also made the first descriptions of archaeological sites in Uruguay, such as that of the “cairns” on the Sierra de las Ánimas.

Collection in Uruguay and its relationship with archaeology has varied over time, depending on the frame of reference. In general terms, we recognize some key moments, which begin with the formation of the first large collections during the late nineteenth and mid-twentieth centuries. There was a great interest in natural sciences, history, ethnography, and ethnohistory (Bauzá Reference Bauzá1929), and these collections were made mainly by scholars, intellectuals, poets, and professionals from other disciplines gathered around scientific associations or institutions, or by local amateurs. At this point, we recognize the research and important contributions achieved by José Henriques Figueira (Suárez Reference Suárez2011). Figueira was a scholar and intellectual who can be considered the pioneer or “founder” of anthropology in Uruguay. His contributions were not limited to archaeology; he also made early contributions to physical anthropology, ethnography, and ethnohistory. He published the first photographs of Fishtail points from Uruguay almost 40 years before those found in Fell's Cave (south of Patagonia). In addition, he made taphonomic observations related to the formation process of archaeological sites in order to discuss Florentino Ameghino's interpretation of the age of archaeological materials and fossils from a site on the Cerro de Montevideo. The latter has double merit—first, because it was carried out in 1892, when Ameghino was a world authority in relation to archaeology and paleontology; and second, because Figueira's arguments not only are advanced for his time but also demonstrate a clear scientific and academic vocation.

This first period, which lasted until the mid-twentieth century, was marked by the development of complex personal networks of scientific sociability (sensu Pupio Reference Pupio2013) and exchange—or not—of information, objects, and documents. The first publications were also authored in this time, including those by Arechavaleta (Reference Arechavaleta1892) and Figueira (Reference Figueira1892). Furthermore, the journal Revista de Amigos de la Arqueología started being published in 1927.

The next stage in the development of Uruguayan archaeology began in the 1960s with the founding of the Centro de Estudios Arqueológicos (CEA), an association that brought together a group of amateur archaeologists led by Antonio Taddei. Although the CEA was located in the capital city Montevideo, it promoted the development of provincial centers, such as the Rivera Archaeology Center, which was under the auspices of a local artist (Santos Reference Santos1965). The CEA maintained an active and close relationship with private collectors throughout the country. The Third National Congress of Archaeology, organized by the CEA in 1974, along with the prominent figure of Taddei were key factors in the creation of a professional career in archaeology in Uruguay. The degree in anthropological sciences with a specialization in archaeology was created in 1976, a period in recent history in which the military dictatorship and its ideological, political, and social repression reached its highest point. Unlike the case of Argentina, where the military dictatorship definitively closed the university career in Mar del Plata—and did so temporarily in La Plata, Buenos Aires, Rosario, and Salta (Politis Reference Politis and Politis1992:83–84)—here in Uruguay, this period was the beginning of the professional career. This is closely connected to the fact that in Argentina there had been many years of tradition in anthropology and archaeology, whereas in Uruguay, from a political point of view, anthropology was not an ideological threat because it did not exist. Furthermore, the political-ideological aspects of the issues discussed during the dictatorship were totally controlled by the military regime. The first generation of students who started university in 1976 graduated in the early to mid-1980s. It was not until 2001 that the university offered a master of science degree (MSc) in anthropology and later, in 2013, a doctorate (PhD) in human sciences.

The new academic career meant a significant cutoff in the relations with collectors. In the professional field, according to similar processes that occur in the region (see Pupio Reference Pupio, Heizer and Lopes2011), there has been explicit interest in differentiating from that nonsystematic action carried out by collectors, who were thought of as undermining archaeological contexts. This situation can be illustrated by the following quote: “The use of scientific methods completely disqualifies the work of collectors and amateurs, clearly establishing the difference between the scientific purposes of archaeology and that of those who go hunting for rare and beautiful objects just to enhance their showcases” (Martínez Reference Martínez1994:29; translated by the authors). Thus began a period of disregard and rejection of collectors and amateurs, which is based on a discourse of academic superiority and exclusivity in the study of the past (see Curbelo Reference Curbelo, Politis and Peretti2004). The resulting gap led, in some cases, to the production of knowledge from a centralized academy located in the capital city, ignoring the diverse local knowledge and perceptions about the past and the landscape. But this gap also resulted in the loss of trust and the low availability among collectors and archaeologists for collaborative work—situations that some archaeologists are trying to reverse today.

A revision of the hegemonic and absolute role of the academic and professional researcher in the production of knowledge about the past has also begun. Following Curtoni (Reference Curtoni, Barberena, Borrazzo and Borrero2009), it is necessary to “decentralize the primary position of the archaeologist in the production of knowledge,” recognizing the existence of other stakeholders in order to give rise to discussion, negotiation, and coparticipation (Curtoni Reference Curtoni, Barberena, Borrazzo and Borrero2009:25; translated by the authors). From new perspectives, some Uruguayan archaeologists are recognizing the role that other nonacademic stakeholders have historically played in the development of archaeological knowledge, inviting methodologies and practices that integrate knowledge and stakeholders (Blasco et al. Reference Blasco, Lamas, Gentile, Villarmarzo, Gianotti, Berrutti, Cabo and Dabezies2014; Caporale and Vallvé Reference Caporale and Vallvé2022; Lamas et al. Reference Lamas, Blasco and Villarmarzo2019; Vallvé and Malán Reference Vallvé and Malán2020; Vienni et al. Reference Vienni, Villarmarzo, Gianotti, Blasco, Bica and Lamas2011; Villarmarzo et al. Reference Villarmarzo, Blasco and Gianotti2020). In this framework, it becomes necessary to reconfigure the relationships between professional archaeologists and collectors and to review the strategies for dialogue.

In 2015, Bianca Vienni carried out a diagnosis of the process of social appropriation of scientific knowledge related to the archaeological heritage from Uruguay. She identified as conflicts the relationship between collectors and archaeologists, the lack of collection inventories, and the lack of access to private collections, among others. According to Vienni (Reference Vienni2015), with regard to the production of knowledge, although among some younger archaeologists there is a trend toward the use of transdisciplinary tools and the production of knowledge together with other social stakeholders, among archaeologists with more extensive experience, the production of knowledge is understood as exclusively led by the interests of the academic community. From this perspective, scientific knowledge has a disciplinary, homogeneous, and hierarchical nature (Vienni Reference Vienni2015). She concludes that

archaeologists stimulate a unilineal paradigm of communication of scientific knowledge that in their discourse is considered as a bidirectional model with a relevant role in society. Although there are programs that seek to carry out these actions, most of the members of the scientific practice subsystem are unable to accomplish comprehensive instances [Vienni Reference Vienni2015:374; translated by the authors].

At this point, it is necessary to refer to the different types of archaeological collections in Uruguay. Although we do not pretend to establish an exhaustive classification or to fully describe the historical processes of formation of these collections, we outline some characteristics that can contribute to a better understanding of the context of our work. A distinction can be made between public and private collections, regarding the current ownership and administration regime. In Uruguay, many current public collections were originally private and later donated or sold to public national and provincial institutions. Due to their process of formation and collector interests, these collections have great heterogeneity in terms of the number and types of pieces, the parts of the country they come from, and archaeological data, which is minimal or missing in most of the cases. The possibility of becoming institutional collections—and therefore a center of reference for researchers and the society in general—on many occasions did not correspond to either the intrinsic characteristics or the information they offered to research. However, this had to do with the collectors’ determinations and personal contacts, which led to their access to public institutions and to decision-makers. On the other hand, there are collections that, for different reasons, do not have institutional status, and they remain in the private sphere. In general, they have been made up by local collectors who, motivated by their own interest in the past and their curiosity, collected archaeological material in areas near their residence. Access to this type of collection, both for research and divulgation, is undoubtedly more difficult, because it depends on personal will and the availability of collectors or their families. In most cases, when the collector dies, the collections are sold, discarded, given away, or dismantled by their families, and if the collector ever had archaeological data, it is usually lost in these situations. In all cases, they are collections of objects that belonged to Indigenous people and/or from historical periods (for example, nineteenth-century battlefields for independence and civil wars), whose heritage situation requires an updated debate that includes, among other things, changes in the Uruguayan legal-administrative framework. Archaeological objects in Uruguay can be sold in the legal market through formal channels, such as auction houses, or they can be sold on the illegal market, which includes social networks (Facebook, Mercado Libre, etc.), street markets, and border regions.

Archaeologists have given nonacademic collections different values in their research process. For some of them, collections are part of a necessary exploratory stage, whereas for others, collections have been the basis for proposing regional occupation models and classification models (e.g., Duran Reference Durán1990; Hilbert Reference Hilbert1991). Iriarte and Suárez (Reference Iriarte and Suárez1993) and Suárez (Reference Suárez, Consens, López Mazz and Curbelo1995, Reference Suárez2000a) are among the first who carried out a critical analysis of the ways archaeologists in Uruguay have approached nonacademic collections, as well as the potential these collections have for systematic research.

Based on this previous work, in the development of the long-term project on the Paleoamerican period,Footnote 1 the study of archaeological material from collections (fishtail points, specialized bifaces, and other artifacts) has been incorporated from the very beginning (Suárez Reference Suárez2000b, Reference Suárez2001a, Reference Suárez2001b, Reference Suárez2006, Reference Suárez2009, Reference Suárez2011, Reference Suárez2015; Suárez and Cardillo Reference Suárez and Cardillo2019; Suárez and Gillam Reference Suárez and Gillam2008; Suárez et al. Reference Suárez, Vegh and Astiazarán2018). These articles demonstrate the potential and importance of investigating and studying public and private collections during the development of long-term research. Another example is from the Colonia Sur Coastal Archaeology Project in the province of Colonia (Malán and Vallvé Reference Malán and Vallvé2019),Footnote 2 whose aim is the study and management of collections for the development of archaeological practice and research (Malán Reference Malán2013, Reference Malán2018, Reference Malán and Martínez2020, Reference Malán2022; Malán and Vallvé Reference Malán and Vallvé2019; Malán et al. Reference Malán, Vallvé and Leal2021; Vallvé and Malán Reference Vallvé and Malán2020). In the province of Río Negro, another team of archaeologists has made a substantial commitment to the review of public and private collections built up in previous decades (e.g., Bortolotto et al. Reference Bortolotto, Fleitas and Gascue2015; Gascue and Bortolotto Reference Gascue and Bortolotto2016; Gascue et al. Reference Gascue, Loponte, Moreno, Bortolotto, Rodríguez, Figueira, Teixeira de Mello and Acosta2016, Reference Gascue, Bortolotto, Loponte, Acosta, Borges, Fleitas and Fodrini2019).

From the Society for American Archaeology (SAA) and the working group created in 2015—Professional Archaeologists, Avocational Archaeologists, and Responsible Artifact Collectors Relationships Task Force—at least two categories of collectors are recognized: “responsible and responsive stewards of the past (RRS) and those whose practices violate archaeological ethics, cultural resource laws, or both” (Pitblado et al. Reference Pitblado, Shott, Brosowske, Butler, Cox, Espenshade and Neller2018:16). In Argentina, Guráieb and Frère (Reference Guráieb and Frère2012) also distinguish those local collectors who throughout their lives have devoted themselves to collecting archaeological objects and “who provide those interested with information about the types of archaeological remains found, the archaeological sites and the landscape” (Guráieb and Frère Reference Guráieb and Frère2012:99; translated by the authors) from another type of collectors, who are “urban and much more selective with respect to the archaeological pieces they collect” (Guráieb and Frère Reference Guráieb and Frère2012:99; translated by the authors), and whose demand promotes the illegal market for archaeological pieces.

In Uruguay, it is possible to identify a variety of cases, all with different implications concerning the regulatory framework. They range from archaeological heritage looters and opportunistic collectors—in coastal areas, for example, beachcombers, tourists, sport divers (see Brum Reference Brum2014; Vallvé Reference Vallvé2021)—to responsible and responsive collectors or stewards of the past (sensu Pitblado et al. Reference Pitblado, Shott, Brosowske, Butler, Cox, Espenshade and Neller2018) who are curious about the history of our ancestors and are sensitive enough to recognize that it is worth guaranteeing their study as well as the collective enjoyment of our cultural heritage. Within all these situations, there are collectors who eventually facilitate the study of their materials and even promote it, contacting researchers and research institutions. A brief characterization of these situations could be summarized as follows:

(1) People who find archaeological material by accident and keep it in their homes or take it to research or reference centers.

(2) Collectors who collect archaeological material on the surface to form their own private, nonprofit collections, motivated by personal interests and curiosity.

(3) Collectors who excavate and destroy archaeological sites in order to recover objects because of their “beauty” and/or uniqueness. Among them, we include those who use metal detectors at historic sites.

(4) People who use objects as goods and sell the pieces they find (to other collectors, tourists, or auction houses).

(5) Collectors who buy archaeological material (in the legal and illegal market).

Despite all these situations mentioned above, we must highlight that many collectors in Uruguay collect archaeological material at sites close to where they live or near places they frequent (vacation-home owners, frequent nautical tourists, fishermen, farmers, landowners, local residents). They often make their archaeological collections from surface sites, and, in general, they do not sell what they collect. There are local collectors who eventually facilitate the study of their materials and even promote it, contacting researchers and research institutions, while there are some others who don't.

In this article, we present our experiences from the Paleoamerican Period Project (RS) and the Colonia Sur Coastal Archaeology Project (MM and EV) concerning our collaborative approach in the study and management of local archaeological heritage, and we offer examples of practices that have created positive relationships between archaeologists and local responsible and responsive collectors (sensu Pitblado et al. Reference Pitblado, Shott, Brosowske, Butler, Cox, Espenshade and Neller2018, Reference Pitblado, Rowe, Schroeder, Thomas and Wessman2022).

Legal and Administrative Framework

First, it is necessary to refer to the legal-administrative framework for collectors and archaeological collections in our country. In Uruguay, the archaeological heritage is under the protection of the Constitution of the Republic: “All the artistic or historical wealth of the country, whoever its owner, constitutes the cultural treasure of the Nation; it is under the safeguard of the State and the law shall establish what it deems appropriate for its defense” (Article 34; translated by the authors). Uruguayan legislation specifically related to the protection of the archaeological record refers to the Heritage Law (Law No. 14,040), enacted in 1971. Article 14 of this law states that any intervention on archaeological sites must be regulated by the state. Therefore, collecting archaeological material without the prior authorization of the competent state agencies, even if it is carried out on private properties, is illegal. Despite this, the fact that in Law 14,040 itself there is no clear conceptualization of archaeological heritage and that, even now, there is no specific regulation that explicitly prohibits the collection and sale of archaeological materials generates situations that are detrimental to the adequate management and protection of the archaeological heritage. In 2017, the Comité Nacional de Prevención y Lucha contra Tráfico Ilícito de Bienes Culturales was created, complying with the recommendations and agreements adopted by Uruguay, such as the 1970 UNESCO Convention on Illicit Traffic, ratified by Uruguay in 1977, among others (Machado Reference Machado2020). This committee has intervened and stopped the sale of archaeological pieces at auctions, but only in cases where the materials have been identified as stolen. For this reason, it is essential to have inventories, which unfortunately does not always happen.

According to Law No. 14,040, one of the five commitments of the Comisión del Patrimonio Cultural de la NaciónFootnote 3 (CPCN in Spanish) is “to propose the plan to carry out and publish the inventory of the historical, artistic and cultural heritage of the nation” (Article 2; translated by the authors). Although the CPCN is currently working on it (García Reference García2020), there is no complete and updated national inventory to date. Meaningful progress, though indirect, occurred with the enactment of the Museums Law No. 19,037, in December 2012, from which the National Register of Museums and Museum Collections was created. Enrollment in this registry is mandatory only for museums and collections managed by the state or of mixed management, whereas it is optional for private ones (Article 12). One of the requirements of this national registry is to make an inventory of its objects (Articles 16 and 17). This law also creates the National Museums System and the Mestiza digital platform, which was developed for the registration of museum collections (with two levels: inventory and cataloging). Although it is a tool that is free and available throughout the country, its use requires a certain level of expertise and, therefore, resources (human–technical and financial), which are not always available. Although the Museums Law constituted an important step in the documentation and registration of the national cultural heritage, it presents the following drawbacks in reference to our object of study (archaeological collections):

(1) It only refers to museums and museum collections (not to small collections or pieces owned by individuals).

(2) Registration is mandatory only for state institutions (leaving out the private sphere, where the practice of collecting occurs).

(3) The inventories requested as a requirement to be part of the national registry are not unified, so their format and database fields depend on each institution.

(4) Although there is a standardization tool that unifies the registry system, it is not mandatory and requires resources for its implementation.

In addition, it was designed for application mainly in museum institutional settings. In sum, as there is no mandatory inventory or registry, this means that the archaeological heritage currently in both public and private/domestic collections is not known. Consequently, the information and trafficking of archaeological objects collected unsystematically cannot be controlled.

Law No. 14,040 requires urgent updating, given that in more than four decades it has undergone few modifications, which have not echoed the new conceptualizations of cultural heritage or international experiences. This follows ineffective and outdated mechanisms that generate “gray legal areas.” Last but not least, Uruguay has not developed real cultural heritage public policies in which archaeological heritage is considered. Because of all these factors, the unsystematic collection of archaeological materials is an activity customarily accepted by the population, which, in general, does not view this activity as a crime.

CASE STUDIES

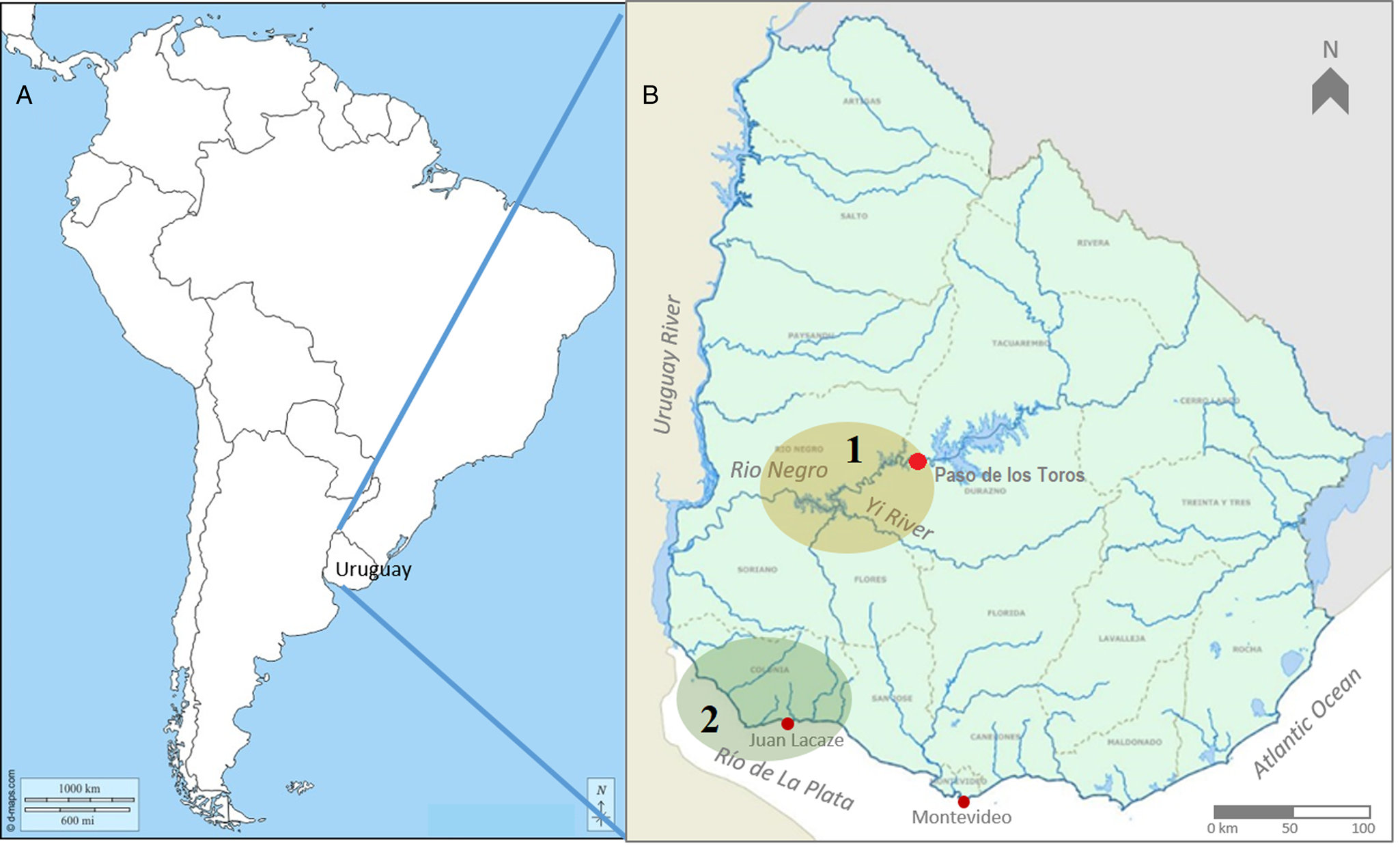

In the research projects we conduct, whose focuses of attention have to do with the early settlement of the Paleoamerican period (RS) and the human occupations on the Río de la Plata coast during the middle and late Holocene (MM and EV; Figure 1), we integrate the participation and collaboration of local responsible and responsive collectors at different stages of the research process. We consider that this practice we have been developing for more than two decades, based on a harmonious relationship between archaeologists and local responsible and receptive collectors, is beneficial for both parties. Our practice is in accordance with the SAA recommendations (Piblado et al. Reference Pitblado, Shott, Brosowske, Butler, Cox, Espenshade and Neller2018) and with much of what has been written by our colleagues in the last issue of Advances in Archaeological Practice (Pitblado et al., eds. Reference Pitblado, Rowe, Schroeder, Thomas and Wessman2022).

FIGURE 1. Location of the case study areas: (A) modified from https://d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=2312&lang=es; (B) modified from https://geoportal.mtop.gub.uy/visualizador; (1) in yellow, the middle Negro River area, where there are intense Paleoamerican occupations; (2) in green, the coast of Colonia Province, Colonia Sur Coastal Archaeology Project (ACCS) work area.

First, as archaeologists we learn and know about new sites and places of interest because they were previously identified by collectors. In practical terms, this can facilitate archaeological survey stages, minimizing time and maximizing resources. The collections also acquire great relevance when we study sites that no longer exist. Such is the case of urbanization on the extensive sites in dunes on the coasts along the Atlantic Ocean and on the coasts of the Río de la Plata and its tributaries (these are areas where real estate pressure as a result of sun-and-beach tourism has grown dramatically since at least the 1940s). Other sites have disappeared due to the construction of hydroelectric dams, such as the Paleoamerican sites in some parts of the coasts of the Uruguay River and the middle portion of Negro River. Some of the coastal sites where we work are exposed to erosion processes due to fluvial dynamics. This alters the archaeological context and leaves archaeological remains temporarily on the shore surface. In the case of the Paleoamerican sites of the Uruguay River, the river usually exposes the archaeological material from the slopes alongside it, remaining on the shore surface temporally, and then the material is transported back by the next flood, which makes it impossible to recover it. For the coastal sites in Río de la Plata (Colonia Province), when strong south winds that significantly increase the water level combine with subsequent lower-than-normal tides, the low intertidal zones are exposed together with archaeological material, which temporally remains on the sandy surface of the beach. During that time, archaeological material is subject to local beach users (bathers, walkers, fishermen). In both areas, the collection of materials has been almost inevitable. However, it has been possible to recover archaeological data thanks to the collaborative work between local responsible and responsive collectors and archaeologists, within a framework of responsible action on conservation and democratic access to archaeological heritage.

Our relationship with collectors of Paleoamerican material has been going on since the beginning of our long-term project, which started in 1999 (RS). Since then, we have visited and kept in contact with different local responsible and responsive collectors who have opened the doors of their homes to us in order to analyze and register their collections, obtained mainly from the Uruguay River and the Negro River. Some collectors are more receptive and have taken part in different instances of the research that we have carried out, such as during the surveys on the Negro River (Séptimo Bálsamo and Robert Bálsamo; see Figure 2). Others participate and collaborate during the excavations that we have carried out at the Paleoamerican sites, such as Pay Paso 1 and Tigre (Suárez Reference Suárez2011, Reference Suárez2015; Suárez et al. Reference Suárez, Vegh and Astiazarán2018).

FIGURE 2. Example of collaborative archaeological survey at the sand dunes of the middle Negro River during December 2021: (A) large sand dune being observed by Séptimo Bálsamo; (B) projectile point found during survey; (C) research team made up of local collaborators and archaeologists—from left to right Bruce Bradley, Robert Balsamo, Victor Carbalho and Rafael Suárez. (Photos by Rafael Suárez.)

Among all our experiences with collectors, we would like to refer to the case of Jorge Vegh (an architect) and Joaquín Astiazarán (a high school history teacher), both responsible collectors. During their rafting sessions (one of their hobbies), in last 20 years they made a collection of approximately 400 surface Paleoamerican artifacts that includes Fishtail points, preforms, bifaces, blades, a discoidal stone, and other tools from the La Palomita site, a fluvial sand dune deposit on the Yi River in central Uruguay. They documented their findings using satellite images, aerial photos, and topographic maps of the Military Geographic Service of Uruguay (scale 1:50,000), where they made annotations and comments. In their last expeditions, they started to use GPS. They signed each artifact and kept them in numbered boxes together with a map indicating provenience (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. Recording and storage of archaeological material done by Vegh and Astiazarán: (A) location of sites on the Yí River using satellite image; (B) packaging in numbered boxes with identification; (C) interior of the boxes with the archaeological material recovered in the Yí River. (Photos by Jorge Vegh.)

Some of their important findings, which include artifacts made by early hunter-gatherers from the plains of Uruguay (Figure 4), were published in collaborative article in PaleoAmerica (Suárez et al. Reference Suárez, Vegh and Astiazarán2018). In addition, both Vegh and Astiazarán participate in different instances of the research projects directed by RS regarding early settlements in Uruguay.

FIGURE 4. Some representative Paleoamerican tools of the Astizarán/Vegh collection donated to the Museo Nacional de Antropología (Montevideo): (A–C), blade tools; (D) stem of Fishtail point; (E) Fishtail point; (F) preform of Fishtail point; (G) discoidal stone. (Photos by Rafael Suárez.)

Responsible and responsive collectors also benefit from a positive relationship with archaeologists. Contact with one of the authors (RS) facilitated what both Vegh and Astiazarán had had in mind for a long time: the donation of their collections to the National Museum of Anthropology (where it is currently partially exhibited). In addition, Vegh is an advanced student of the MSc program in anthropology and Astiazarán began to work on the degree in anthropological sciences at Universidad de la República (FHCE-UdelaR). This case is interesting for several reasons:

(1) It shows how responsible collectors stop collecting archaeological objects when understanding their value goes beyond the affective-emotional value they give to those objects, and they have even joined academic training programs.

(2) The donation of their collections also shows that they are responsible and responsive enough to consider that those objects are part of the archaeological-cultural heritage so that researchers can study them and the whole society can enjoy them.

(3) This also shows that professional archaeologists should not stigmatize collectors, because they can be future colleagues.

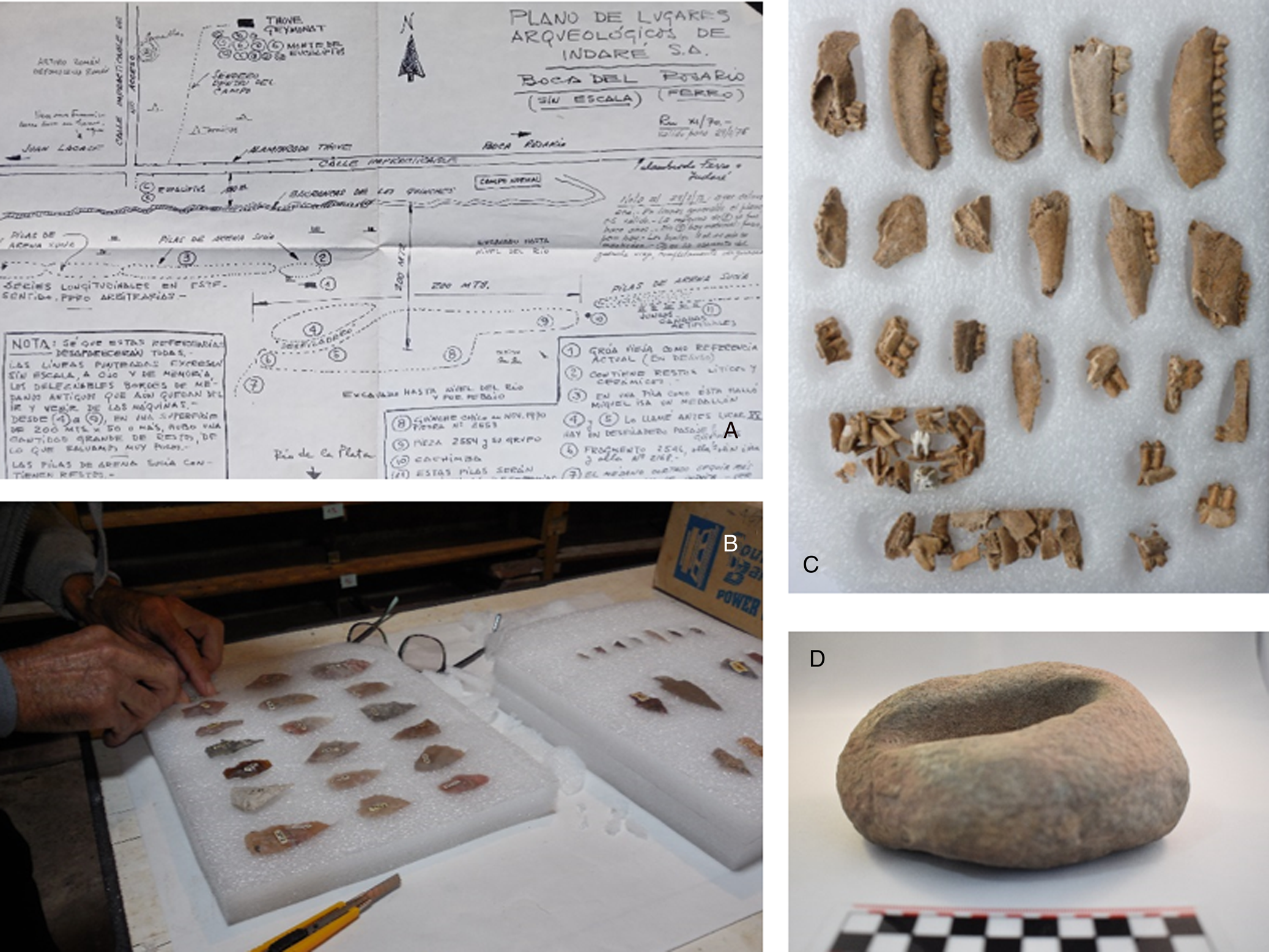

Another example of the positive relationships between archaeologists and collectors is the work that we have been doing in the province of Colonia (MM and EV), based on the study of the René Mora Archaeological Collection (Malán Reference Malán2013, Reference Malán and Martínez2020), with more than 27,000 pieces unsystematically collected by Mora over four decades in the region but with important archaeological data (Figure 5). After several years of work and good relationships with René Mora's heirs, and because of interinstitutional collaboration, the family donated the collection to a cultural reference local institution in 2015 (Rodó Library in the town of Juan Lacaze). Since then, we have been working on conservation, research, and enhancement of the collection, with every task inextricably linked to public use and enjoyment. For the collection inventory, as well as the organization of the associated information, the collaboration of César Mora, René's son, has been extraordinary. Furthermore, César Mora is one of the key informants for the project we carry out in the area. In addition, because of this successful case and its positive results, other collectors have opened their doors, allowing the study of their pieces, providing information, accepting conservation guidelines for the care of their domestic collections, and even expressing the intention to donate them to the same institution. Moreover, some local collectors have lent their archaeological material for research, publications (Malán et al. Reference Malán, Vallvé and Leal2021), and exhibitions at Rodó Library. In Figure 6B, a piece of pottery that was brought by a local collector during one of our regular workshops is registered and analyzed.

FIGURE 5. Example of the archaeological data that is part of René Mora Collection: (A) sketch made by Mora in 1970 showing different sorts of data about several findings; (B), (C), and (D) are examples of archaeological material from the René Mora Collection, now located in Rodó Library. (Photos: ACCS Archive, 2019.)

FIGURE 6. Examples of participatory laboratory research work at Rodó Library in Juan Lacaze, Colonia: (A) Local Archaeological Research Support Team (ELAI) working on classification and primary analysis of archaeological material from the René Mora Collection; (B) archaeologist, archaeology student, professor, and ELAI collaborator studying a pottery vessel from a local collection with a portable low-magnification digital microscope. (Photos: ACCS Archive, 2019.)

From our experience in the Colonia Sur Coastal Archaeology Project, active locality presence and a strong commitment to working with the local community (Vallvé and Malán Reference Vallvé and Malán2020) have been the backbone of our work. Workshops, minicourses, and exhibitions are regularly held in order to share the valuable cultural-archaeological heritage of the area, to raise awareness about the importance of recovering contexts with archaeological techniques, and to promote good practices related to preventive conservation (archaeological materials from private collections in private homes due to inadequate storage conditions present conservation problems, in general). Within this framework, we formed the Local Archaeological Research Support Team (ELAI in Spanish). It is a heterogeneous, committed, and motivated group of 20–30 people (Figure 6), with ages ranging between 14 and 80 and a diversity of personal interests. Secondary-level students and teachers, neighbors, owners of land where there are archaeological sites, tour operators, officials of cultural institutions, university archaeology students, collectors, and local stewards of the past are part of the ELAI. They all contribute their knowledge to strengthen the research and management of the sites. In addition to participation in field and laboratory tasks, the ELAI members collaborate on the display of exhibitions and coparticipate in the experimental archaeology work line. Last but not least, all the members of the ELAI work for free in the project.

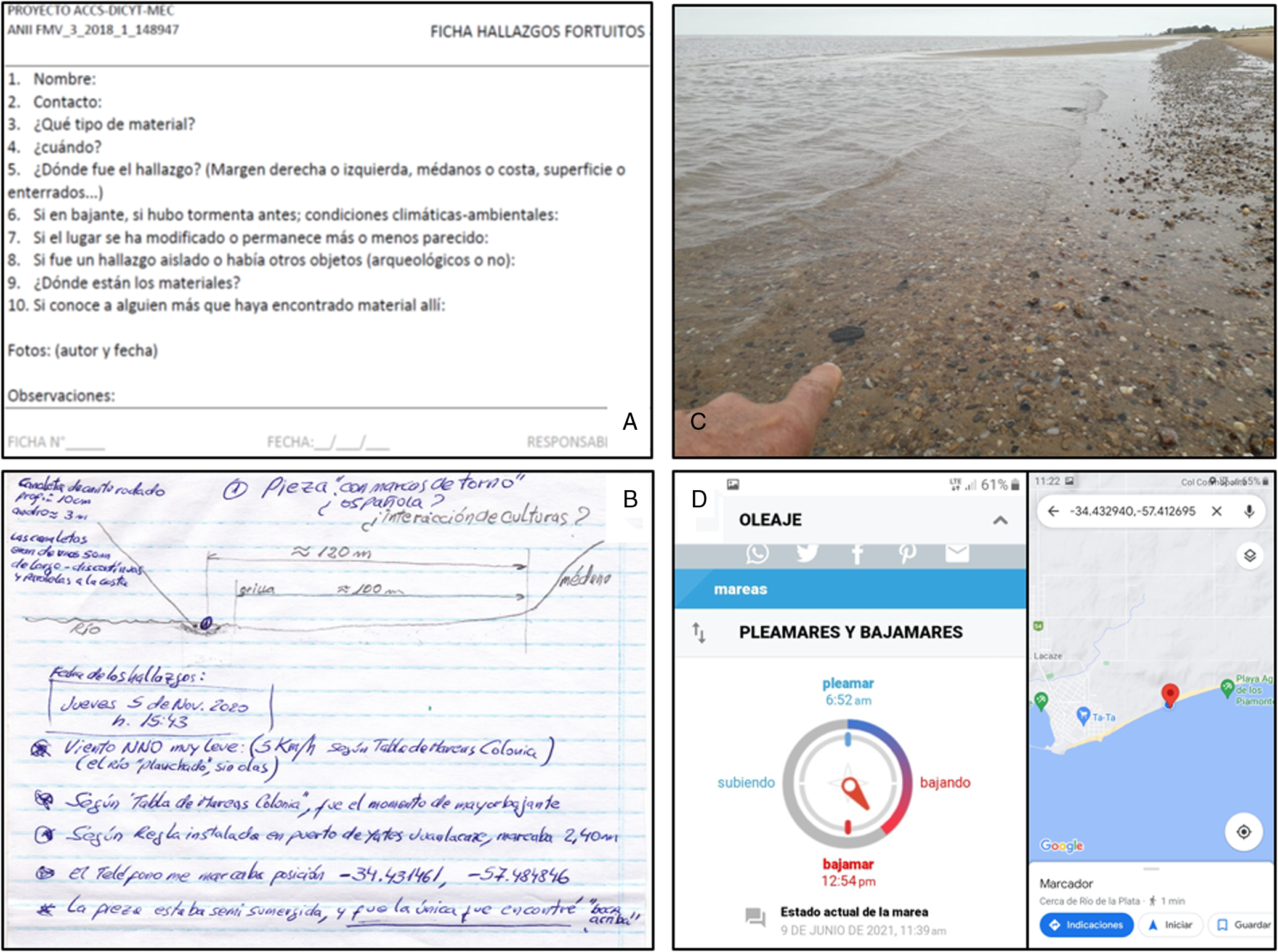

Another important tool has been the implementation of a self-filling form (see Figure 7), whose aim is to help with the systematization of information about casual archaeological findings (a common situation on the coast of Río de la Plata). This participatory tool aimed at the local population, which has experienced these casual findings (current or past), allows the registration and documentation of information (including photography and georeferencing, when possible) so that it can be used in research and heritage management. This short form, which works as a guide, can be filled out both on paper or digitally (through WhatsApp, text or audio message, or e-mail). The form contains 10 fields, including personal information (name, telephone number), type of find, date, context information (other material associated), weather conditions (wind direction, extreme events, lower tides), current location of the objects found, and whether the individual knows any other person who has found any archaeological materials (Vallvé and Malán Reference Vallvé and Malán2020). This last item, together with ELAI's own work, has been very useful for getting in contact with collectors or stewards of the past who are more difficult to identify and approach. This action has enabled the initiation of positive relationships with other local collectors and the activation of awareness processes about the inconvenience of collecting and the importance of sharing information. With this form, we are not only generating baseline data about archaeological sites and site formation processes but also discouraging collection. We work under the slogan “collect information but not materials.” Based on the involvement and active participation of responsible and responsive collectors and local stewards of the past in different stages of our research and site management, we are committed to generating changes in people's behavior, raising awareness for the sustainable management of archaeological heritage, promoting a sense of belonging, and strengthening ties of cooperation between archaeologists and collectors.

FIGURE 7. (A) Self-filling form; (B), (C), and (D) examples of information sent by Ángel Germano, ELAI member and local resident of Juan Lacaze, about his findings during his usual walks along the beach. In the case of (B), in 2019, he took a paper form to our laboratory, together with the collected pieces. In the case of (C) and (D), in 2021, he sent the information by WhatsApp, and he did not collect the material, which remained in situ.

CLOSING THOUGHTS AND PROPOSALS

The existing legal vacuum, together with outdated legal-administrative frameworks in Uruguay, generate “gray legal areas” regarding the practice of collecting and commercializing archaeological heritage. As a consequence, the perception between what is legal and what is illegal is not always so clear, giving rise to inappropriate practices that put the integrity of archaeological heritage at risk.

From our archaeological practice, based on concrete experiences, we believe it is necessary to advance in some specific ways. We envision and propose at least the following three:

(1) Legislation Update. To date, all the attempts to update Law 14,040 have failed. Currently, the Comisión del Patrimonio Cultural de la Nación is working on a new law. In each of these instances, the Association of Professional Archaeologists of Uruguay (AUA, according to the previous designation; ARQUA, according to the current designation) has actively participated, advising and contributing not only reflections but also specific content for the drafting of the new bills. From our point of view—and specifically in reference to the issue of this article—we highlight some points that should be addressed in the new regulatory framework: (a) update the definition of archaeological heritage and clearly define the framework of legal action around this concept, especially in terms of interventions; (b) establish and specify a mandatory national registry, both in the public and private spheres, that allows the current situation to be visualized and that provides tools with which to act in the future; (c) regulate aspects related to the commercialization of archaeological heritage, which should not be subject to the market system.

(2) Code of Professional Ethics. In Uruguay, professional archaeologists do not have a code of ethics that guides their practice and work. Currently, the Association (ARQUA) has proposed creating this as the main objective for the year 2022. We believe it is important to include guidelines on the relationship with other social stakeholders interested in archaeological heritage, such as responsible and responsive collectors, stewards of the past, and Native peoples’ descendants. A respectful treatment protocol should be generated for burials and/or human bones recovered in excavations as well as for the practice of taking samples for genetic studies. However, it is important to note that this code would affect less than 50% of archaeologists in Uruguay, those who are part of the association. The others are not affiliated with any professional group and are therefore are exempt from these regulations.

(3) Work Methodologies. We propose implementing strategies based on the coparticipation and integration of actors and knowledge, promoting inter- and transdisciplinary dialogue and reconciling different points of view, interests, and knowledge in order to minimize conflicts and maximize benefits (Olsen et al. Reference Olsen, Kern and Tobey1999). Vitancurt (Reference Vitancurt2014) proposes four pillars that should be taken into account in a participatory practice:

(a) Construction of trust, based on the acceptance of differences of opinion, vision, and interests; fluid and transparent communication; reaching agreement to progress to concrete actions.

(b) Continuity of the process over time. This is essential to achieve real and effective participation based on human relationships that last over time. Trust should be achieved by the accumulation of concrete actions and permanent work in the territory.

(c) Gradualism, regarding the formalization and institutionalization of working groups. It is a process that begins with specific actions and that, over time, “progresses to more complex forms of organization, addressing broader issues” (Vitancurt Reference Vitancurt2014:133).

(d) Adaptation regarding the need for revision and permanent adjustments.

We propose going one step further toward a real horizontalization of the participation of collectors by sharing and allowing them to participate in scientific publications (when they are interested). In this sense, the case of La Palomita Paleoamerican site, where an archaeologist and collectors share authorship in a prestigious international scientific journal, is an example of this effort (Suárez et al. Reference Suárez, Vegh and Astiazarán2018). The relationship between archaeologists and collectors in Uruguay must overcome the still-prevailing authoritarianism or academic superiority that exists in some cases. Instead, we encourage cooperation in all stages of research, with the real participation of the different stakeholders and the generation of favorable conditions to carry out collaborative work.

Our work in the province of Colonia around the Mora Collection, which began nearly 15 years ago, and the more recent formation of the ELAI (2018), represent successful alignment with these pillars. The formal participation of the local community in the registration and systematization of information through the self-filling form is a good example of this. Tools like this help to collect information that can be incorporated into archaeological research and heritage management programs, while at the same time creating awareness of archaeological heritage. Local stakeholders, including responsible and responsive collectors, become protagonists with real responsibility for the conservation of heritage. During this time, the ELAI has constituted a space for permanent reflection on the activity of collecting archaeological materials and its consequences.

We do not encourage responsible and responsive collectors to collect artifacts from archaeological sites. However, responsible and responsive collectors and archaeologists both have legitimate interests concerning archaeological material and past knowledge. Because of this, in our projects, we encourage a collaborative and open practice between archaeologists and responsible collectors, as was shown in the cases presented in this article. Although some archaeologists in Uruguay are in the process of reviewing certain hegemonic accounts from the academy and reconfiguring the relationships between archaeologists and collectors, there is still a long way to go. We believe this practice should be formally encouraged by the academy as well as public and private institutions.

From our experiences of working with responsible and responsive collectors and local stewards of the past in Uruguay, we recognize the importance of advancing in formal and practical terms, with our main focus being trust built around the ideas of stewardship and heritage values through continuity and mutual respect. We recognize the importance and convenience of sharing information and knowledge, and the recognition of common interests and shared rights duties over archaeological heritage.

Acknowledgments

Our thanks go to all the collectors who have shared their knowledge and archaeological collections with us; to Bonnie Pitblado, Suzie Thomas, Anna Wessman, Bryon Schroeder, and Matthew Rowe—the Advances in Archaeological Practice guest editors who allowed us to present our case study in this volume; to the reviewers who helped to improve this manuscript with their suggestions and comments.

Data Availability Statement

No original data were used in the preparation of this article.

Competing Interests

The author(s) declare none.