Introduction

In 2018 Czechs celebrated 100 years of their nation-state—75 years as Czechoslovakia and 25 years as Czechia. Nation-building refers to a process of unifying citizens through a sense of unity and cohesion. It is believed that it goes hand in hand with positive economic and political outcomes (Ahlerup and Hansson Reference Ahlerup and Hansson2011). Currently, the country has robust economic and wage growth, the lowest unemployment in the European Union, low numbers of people at risk for poverty or social exclusion, low crime rate, low economic emigration, low illegal immigration, and the world’s fifth most-accepted passport.Footnote 1 A successful nation-building process has several aspects: that the citizens of a country feel bound together by a sense of community; that they talk to, understand, and trust one another; and that they identify with and take pride in their nation (Ahlerup and Hansson Reference Ahlerup and Hansson2011). Nevertheless, Czechs are less proud of their citizenship than are the citizens of some European countries, such as Ireland, Greece, Iceland, Norway, and Slovenia. According to the European Values Study 2017 data, 35 percent of respondents in the Czech Republic are “very proud,” 49 percent “quite proud,” 13 percent “not very proud,” and 2 percent “not at all proud” of their citizenship (see Figure 1). Although cross-national surveys measure cultural differences in expressing national pride rather than national pride itself (Miller and Ali Reference Miller and Ali2014), differences in the degree of national pride among countries, however, have become a subject of Czech public debate. Opinions about Czech national pride range from the stance that the low level of national pride and “bad mood”Footnote 2 are inconsistent with the country’s achievementsFootnote 3 to the stance that, with respect to recent European history, it is not desirable to boost such group-based emotions as national pride (Miller-Idriss and Rothenberg Reference Miller-Idriss and Rothenberg2012).

Figure 1 How proud are you to be a [COUNTRY] citizen?

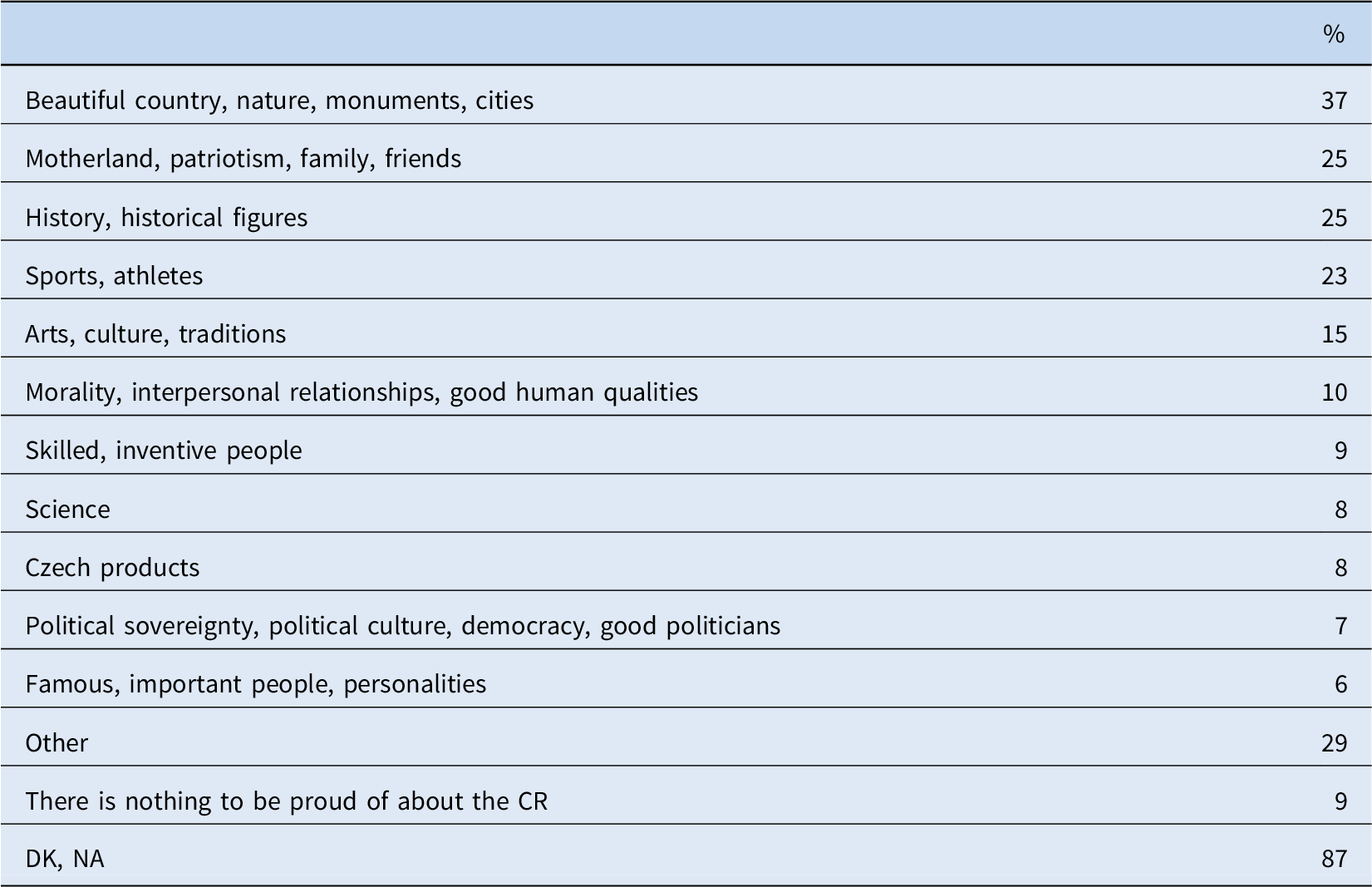

The surveys Naše společnost (October 2015) and International Social Survey Programme 2013 (National identity III) show that Czechs take pride in their citizenship because they live in a motherland with a beautiful countryside, picturesque nature and cities, history, historical monuments and figures, and also because of their families and friends (Čadová Reference Čadová2015; see Tables 1 and 2). For Czechs, achievements in sports are an important source of national pride, followed by history, achievements in the arts and literature, and scientific and technological achievements. When they think about history, they particularly appreciate the eras of the First Czechoslovak Republic (1918–1938), the Hussite Wars (1420–1434), the rule of Charles IV, and the 1968 Prague Spring (Šubrt and Vávra Reference Šubrt and Vávra2010). Attested periods of decline include the German invasion in 1939 and Protectorate, the Communist regime, and the 1968 Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia led by the Soviet Union. Relations with foreign countries and subordination to external powers are the reasons for low national pride for 12 percent of respondents. The main reasons for low pride, however, lie within Czech society. Czech national pride is reduced by perceptions of the political situation in the Czechia, corruption, fraud and theft, morality, poor interpersonal relations, and negative personality traits of compatriots, social pathology, and other social problems (Čadová Reference Čadová2015; see Table 3).

Table 1 Why are you proud of being a citizen of the Czech Republic?

Note: N=1045 15+. Respondents selected up to three categories.

Source: Naše společnost 2015—October.

Table 2 How proud are you of the Czech Republic in each of the following? (%)

Source: International Social Survey Programme 2013.

Table 3 Why are you not proud of being a citizen of the Czech Republic?

Note: N=1045 15+. Respondents selected up to three categories.

Source: Naše společnost 2015—October.

National pride is shaped by the unique historical and societal circumstances existing in each country, and by socio-demographic positions within each country (Smith and Kim Reference Smith and Kim2006, 133; Miller and Ali Reference Miller and Ali2014; Ha and Jang Reference Ha and Jang2015). Melancholy and weak national pride are more prevalent in nations that lost their autonomy or independence and retain memories of lost battles (Resnick Reference Resnick2008). This is the case for Czechs, who take pride in the rule of Charles IV,Footnote 4 when their capital, Prague, was also the capital of the Holy Roman Empire, and in the 20 years of existence of the economically advanced First Czechoslovak Republic. On the contrary, there is still an ongoing debate about how national pride was influenced by the Nazi occupation, Communist regime, and Soviet occupation. Vojtěch Šustek (Reference Šustek2013) documents how Nazi propaganda was used to damage the social cohesion and national pride of the Czech nation in the Protectorate.Footnote 5 The diminutive term little Czech (čecháček) in the title of Ladislav Holy’s (Reference Holy1996) book comes from wartime Minister of Education and National Enlightenment Emanuel Moravec (a former Czech Legionnaire, Czech army officer, military expert, and journalist turned Nazi collaborator). For him, the “little Czech” was someone who had little enthusiasm for the German Reich. Šustek (Reference Šustek2013) also shows that a part of the Nazi propaganda was adopted by the subsequent Communist regime to minimize the importance of non-communist anti-Nazi resistance, and the term little Czech has been used by some Czech politicians and journalists for people with little enthusiasm for “big” political ideas.Footnote 6

Nation and National Pride: Theory and Explanations

A nation is understood as a human group conscious of forming a community, inhabiting a particular state or territory, sharing (a myth of) common descent,Footnote 7 culture, language, having a common past (history) and a common project for the future, and claiming the right to govern themselves (Guibernau Reference Guibernau1996, 47-48). There is disagreement on the historical origins of nations and the roots of contemporary national identities. The different theories can be ordered on a timeline: whereas constructivists or modernists hold that nations and national identity are recent and flexible concepts that have emerged during the last two centuries (Gellner Reference Gellner1983; Anderson Reference Anderson1991), primordialists or perennialists hold that nations have ancient origins and deep cultural roots and change very slowly, if at all (Smith Reference Smith1986).

Nations are understood both as real entities (Brubaker Reference Brubaker1996) and as imagined communities (Anderson Reference Anderson1991). All communities larger than primordial villages of face-to-face contact, including nations, have to be imagined. Benedict Anderson (Reference Anderson1991) presents nationalism—a socio-cultural formation within nations—as a way of imagining and thereby creating communities. Nationalism binds people together in a community and promotes solidarity between rich and poor, left and right, and in a sense endorses a particular kind of equality among all members of a nation (Eriksen Reference Eriksen2002).

National pride is understood as a group-level emotion based on identification with a nation and unique appraisals of nation-relevant objects or events (Smith, Seger, and Mackie Reference Smith, Seger and Mackie2007; Smith and Mackie Reference Smith and Mackie2016), and perceptions of the collective’s emotional experience, namely, the perception of what the majority of group members feel. The notion of group-based emotions has been debated by social identity theorists (Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel and Turner1986), intergroup emotions theorists (Smith, Seger, and Mackie Reference Smith, Seger and Mackie2007), and cognitive appraisal theorists (Tracy and Robins Reference Tracy and Robins2007). Currently, there is a growing body of research on emotional climates, emotional atmospheres, intergroup emotions, and emotional cultures in both small (fan groups, religious groups, work teams, orchestras, families) and large groups (societies, nations) (von Scheve and Ismer Reference von Scheve and Ismer2013, 406).

National pride is an emotion people feel toward their nation-state (Smith and Kim Reference Smith and Kim2006). It can be based on positive feelings toward the nation’s achievements (Evans and Kelley Reference Evans and Kelley2002Reference Diener, Richard and Shigehiro; Smith and Kim Reference Smith and Kim2006) and good qualities of the individuals, communities, and institutions within the country, or it can represent beliefs about the superiority of the country based on ancestry, culture, and tradition (Smith and Kim Reference Smith and Kim2006, Ha and Jang Reference Ha and Jang2015). National pride based on achievements is linked to patriotism, while national pride based on descent, culture, and tradition is linked to nationalism. The former also corresponds to authentic pride, the latter to hubristic pride (Ha and Jang Reference Ha and Jang2015).

National pride is associated with national identity (Smith and Kim Reference Smith and Kim2006; Morrison, Tay, and Diener Reference Morrison, Tay and Diener2011; Reeskens and Wright Reference Reeskens and Wright2011; Ha and Jang Reference Ha and Jang2015). Nevertheless, it differs from national identity. While national identity reflects normative aspects of national membership, national pride reflects emotional aspects of national membership (Ha and Jang Reference Ha and Jang2015). National identity is generally defined using a dichotomy of ethno-cultural and civic identity (Jones and Smith Reference Jones and Smith2001a, Reference Jones and Smith2001b; Kuzio Reference Kuzio2002; Shulman Reference Shulman2002; Reeskens and Hoodghe Reference Reeskens and Hooghe2010). An ethno-cultural concept of national identity is based on ancestry, birth in the country, language, and religion (Kohn Reference Kohn1944; Smith Reference Smith1991; Jones and Smith Reference Jones and Smith2001a, Reference Jones and Smith2001b; Haller, Kaup, and Ressler Reference Haller, Kaup and Ressler2009).

According to the ethno-cultural concept of national identity, nations are viewed as collections of inter-related families having common ancestors or forefathers (Barrett Reference Barrett2000; Guibernau Reference Guibernau2004; Ford, Tilley, and Heath Reference Ford, Tilley and Heath2012). The civic concept of national identity is based on citizenship and respect for national institutions and laws. To belong to a nation, we must be born to it or acquire citizenship. However, citizenship is an involuntary legal status (Vink and Bauböck Reference Vink and Bauböck2013) and therefore is not automatically accompanied by national pride. Where we are born and what language we learn as infants is pure happenstance, and for most people today, being a citizen of a nation-state is just something we get in the lottery of birth (Bakke Reference Bakke2000; Brubaker Reference Brubaker2004). This is especially the case for younger, educated, secular, and cosmopolitan people benefiting from membership of their country in the European Union, but less the case of older generations experiencing confrontation with “others” threatening their national existence.

National pride is also related to happiness (Morrison, Tay, and Diener Reference Morrison, Tay and Diener2011; Reeskens and Wright Reference Reeskens and Wright2011; Ha and Jang Reference Ha and Jang2015). The word happiness is synonymous with subjective quality of life or well-being and connotes that life is good without specifying what is good about life (Veenhoven Reference Veenhoven2015). Happiness is defined as “a person’s cognitive and affective evaluations of his or her life” (Diener, Lucas, and Oishi 2001, 63) on three societal levels: (1) the micro level of individuals—social status, education, occupation, minority status, social participation, intimate ties, marriage, children; (2) the meso level of institutions—autonomy and size; and (3) the macro level of society—wealth, freedom, equality, security, institutional quality, and modernity (Veenhoven Reference Veenhoven2015, 383-9).

Research at the macro level indicates that the nation-state of which people are citizens (or residents) has consequences for people’s happiness. People live happier in modern, free, wealthy, gender-equal, secure, and well-organized societies, where they can count on the rule of law and a properly functioning government (Veenhoven Reference Veenhoven2015, 382-6). Institutional performance theories explain trust in institutions as an effect of their service delivery. For example, institutions become trustworthy when they provide protection against external aggression, prevent crime and terrorism, fight poverty and unemployment, improve the economy, provide education and health care, and integrate minorities and immigrants. Trust in institutions is violated by unfair and undemocratic decision making (procedural fairness theories) resulting in abuse of power, corruption, or unequal treatment of different groups in a society. Poor instrumental performance of government and unfair decision making lead to less trust in government (Norris Reference Norris1999). Perceived government effectiveness and satisfaction with the performance of a country’s political system are sources of national pride that can be distinguished from cultural pride (Nedomová and Kostelecký Reference Nedomová and Kostelecký1997; Vlachová and Řeháková Reference Vlachová and Řeháková2009; Dražanová Reference Dražanová2015).

Russell Dalton (Reference Dalton1999, 58) and Tom Smith and Seokho Kim (2006, 130) define national pride as a kind of affective orientation toward the national political system and a part of diffuse political support—a deep-seated set of attitudes toward the political system that is relatively impervious to change. Andreas Wimmer (Reference Wimmer2017) formulates precisely that pride is produced by power. Members of groups who are not represented in national government are less proud of their nation than other members of the polity. At the country level, the larger the share of the population that is excluded from representation in government, the less proud citizens are on average. National pride signals loyalty to a national political community and the nation-state (Dalton Reference Dalton1999; Tilley and Heath Reference Tilley and Heath2007) and is a proxy for social cohesion (Easterly, Ritzen, and Woolcock Reference Easterly, Ritzen and Woolcock2006; Schnabel and Hjerm Reference Schnabel and Hjerm.2014). Weak national pride is often in large part due to citizens’ distrust in their political institutions and leaders (Kuzio Reference Kuzio2002Reference Diener, Richard and Shigehiro; Brubaker Reference Brubaker2004).

Political trust is earned on the basis of performance (Kukovič Reference Kukovič2013). It is learned indirectly, at a distance. Media sell the country to the citizens and help shape a particular image of the national political community (Anderson Reference Anderson1991; Guibernau Reference Guibernau2004). National pride is not a matter of fact, but of public narratives, self-understandings shaped and reshaped by stories (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2004; Miller-Idriss and Rothenberg Reference Miller-Idriss and Rothenberg2012). Their effect may be, however, controversial. On one hand, media malaise theory tells us that all forms of modern mass media bring bad news and attack journalism and undermine the political community. On the other hand, mobilization theory states that regular consumers of political news, regardless of the news’ tone, are more inclined to be informed, interested, and involved in their communities (Norris Reference Norris1999; Jeffres et al Reference Jeffres, Lee, Neuendorf and Atkin2007; Luengo and Maurer Reference Luengo and Maurer2009).

Pride is also determined by relationship with other people (Poggi and D’Ericco Reference Poggi and D’Errico2011). Social trust (interpersonal trust, generalized trust) is the trust that people have in one another. Since the French revolution, legitimate states have been constituted by their citizens. Elisabeth Bakke (Reference Bakke2000) argues that citizens of a nation-state should have stronger feelings of belonging to their fellow citizens than to foreigners. According to the social capital theory, social trust is an exogenous factor in generating economic and governmental performance (the “bottom-up approach”; Jackman and Miller Reference Jackman and Miller1998). Trust and social interconnectedness are components of a democratic political culture and low levels of social trust seem to be an inheritance from communist rule (Uslaner Reference Uslaner1999). However, there is also research that shows that social trust is an effect, rather than a result, of institutional settings (Letki and Evans Reference Letki and Evans2005). The “top-down approach” understands social trust as a result of an institutional setting. Social trust is more important in authoritarian regimes, where social relations are necessary for everyday economic survival and the development of anti-regime freedom movements, than in liberal democratic regimes (Åberg and Sandberg Reference Ǻberg and Mikael2003; Letki and Evans Reference Letki and Evans2005). Ladislav Holy (Reference Holy1996) describes the nature of social trust in communist Czechoslovakia similarly. In a totalitarian regime, it made little sense to trust anyone but family and closest friends. This kind of social trust was broken up by the move to democracy and a market economy (Letki and Evans Reference Letki and Evans2005).

Previous studies from Western countries reveal that less-proud citizens tend to be younger and more educated (Smith and Kim Reference Smith and Kim2006; Tilley and Heath Reference Tilley and Heath2007). Martyn Barrett (Reference Barrett2000) supposes that the sense of national pride develops during childhood and adolescence and remains relatively stable throughout the life cycle. Generational change, however, brings more-educated and less-religious generations among those who grew up in cosmopolitan and ethnically pluralist environments and do not remember the struggle of their nation-states during the Second World War (Tilley and Heath Reference Tilley and Heath2007). Some studies provide evidence that men generally express more national pride than women (Smith and Kim Reference Smith and Kim2006; Grossberg, Struwig, and Pillay Reference Grossberg, Struwig and Pilay2006). The reasons why men tend to be prouder citizens than women are summarized, for example, by Zillah Eisenstein (Reference Eisenstein2000, 42). Nations are often envisioned as patriarchal families, “fraternities” or brotherhoods of men, in which the traditions of the “forefathers” are passed down to young men in the next generation. Men protect and avenge the nation, while women reproduce it. Nations reinforce and support male privilege and women are often excluded from positions of power—there is no equal sisterhood in citizenship.Footnote 8 National pride is greater among the dominant cultural group, and lower among deprived minority groups (Smith and Kim Reference Smith and Kim2006; Cebotari Reference Cebotari2015).

The goal of my study was to test how national pride depends on national identity, confidence in government, satisfaction with the way democracy works in the country, political interest, happiness, social trust, and socio-demographic variables.

Data and Variables

The October 2015 round of the survey Naše společnost was based on quota sampling and does not measure general national pride. Therefore, for my main analysis of general national pride, I used European Values Study 2008 based on a probability sample.Footnote 9 The analysis was performed on the subset of 1,790 Czech citizens (people who confirmed they are citizens of the Czech Republic in question Q71). In the European Values Study 2008 survey, national pride was measured by the question, “How proud are you to be a [COUNTRY] citizen?” This question on national pride captures people’s general national pride without any reference to specific national achievements (Cebotari Reference Cebotari2015). The survey also contains a large set of explanatory variables, as summarized here:

∙ happiness,

∙ generalized (social) trust,

∙ specific political support—confidence in government, satisfaction with the way democracy is developing in the country,

∙ civic identity and ethnic identity—to respect [COUNTRY]’s political institutions and laws, and to have [COUNTRY]’s ancestry,

∙ political interest—following politics in the news on the television or on the radio or in the daily newspapers,

∙ socio-demographic variables—sex, age, education.Footnote 10

Results of the Analysis

Table 4 presents the descriptive statistics for the explanatory variables, and Table 5 shows the results of three ordinal regression models that examine the relationship between general national pride and a set of predictor variables. The first model, M1, tests the effects of happiness, social trust, specific political support, and political interest (measured by frequency of following political news in the media) on general national pride. Although Hans-Dieter Klingemann, Dieter Fuchs, and Jan Zielonka (Reference Klingemann, Fuchs and Zielonka2006) do not find strong evidence that perception of government and the political system influence national pride in countries of Central and Eastern Europe, my analyses of Czech European Values Study data show a different picture.

Table 4 Descriptive statistics of explanatory variables.

Source: European Values Study 2008.

Table 5 Models predicting national pride (1–4, reference: 4=Very proud), parameter estimates.

Significance: alpha <0.001***, alpha <0.01**, alpha <0.05*.

Ordinal regression, link function: Complementary log-log: f(x)=log(−log(1−x))

Source: European Values Study 2008.

Model M1 confirms that confidence in government and satisfaction with the development of the democracy significantly predict general national pride; satisfaction with development of democracy appears to be an especially strong predictor of general national pride. There is ample evidence from public opinion surveys that confidence in government and satisfaction with development of democracy are generally low in the Czech Republic. Confidence in government also varies depending on the instrumental evaluations of a particular government (Kunštát Reference Kunštát2014; Červenka Reference Červenka2016) and satisfaction with the way democracy is developing in the country grows very slowly (Čadová Reference Čadová2016). During its first 25 years of independence, the Czech Republic has had 13 governments, but only three of them completed the four years of their electoral term. In 2008, the government even lost a vote of confidence during the Czech EU Presidency, when it was trusted by only 21 percent of the public. The analyses of the European Values Study 2008 data show that 45 percent of Czech citizens have “not very much” confidence in government and 34 percent have “none at all”; 45 percent of Czechs are “not very satisfied” and 14 percent are “very unsatisfied” with the way democracy is developing in the country and both variables are significantly correlated (Spearman r=.33, sig=.000). Model M1 also provides evidence that political interest measured by frequency of following politics in the media is positively associated with higher national pride. About 29 percent of Czech citizens follow politics on television, radio, or in the daily papers less than once a week or never and 43 percent follow political content in the media several times a week. Less politically interested people tend to be less proud citizens.

National pride is an emotion determined by positive self-evaluations of people and relationships with other people. Czechs show a below-average level of happiness in Europe (Watson, Pichler, and Wallace Reference Watson, Pichler and Wallace.2010; Hamplová Reference Hamplová2015: 31). Analyses show that they tend to choose the category “quite happy” in surveys. In the European Values Study 2008, evaluative happiness (Dolan and Metcalfe Reference Dolan and Metcalfe2012) was measured and 71 percent of Czech citizens reported that they were “quite” happy. The main sources of happiness in the Czech Republic are family and friends; slightly less important are work and leisure time (Hamplová Reference Hamplová2015). Model M1 (table 5) shows that happiness is a strong predictor of national pride. People who are “not very happy” (14 percent of respondents) or “not at all happy” (2 percent of respondents) tend also to be “not very proud” or “not at all proud” citizens. Social trust appears to be a significant predictor of national pride, too. Czechs display an average level of social trust in Europe (Olivera Reference Olivera2013). In the European Values Study 2008, 70 percent of Czech citizens agreed with the statement that “you can’t be too careful in dealing with people.”

In the second model, M2, two more variables, civic and ethnic nationalism, were added to the analysis. The analysis did not confirm any significant effects of ethnic or civic nationalism on national pride. Descriptive analysis provides evidence that 87 percent of Czechs believe that it is respect for national laws and institutions which makes a man or woman a true Czech (civic nationalism) while 71 percent of Czechs think that ancestry is the necessary prerequisite for being member of the Czech nation (ethnic nationalism; Vlachová 2019). Neither type of nationalism is significantly associated with national pride in the Czech Republic.

Based on previous studies I expect that less-proud citizens are younger, more educated, and women. Model M3 brings findings regarding socio-demographic covariates—sex, age, and education. Covariates slightly improve the model, because age and education have significant effects on general national pride. People age 60 and over tend to be more-proud citizens than do younger cohorts. Cohorts born before 1949, who experienced times of national solidarity during and after the Second World War, Communist coup, and invasion led by Soviet Union feel more national pride than do younger cohorts without similar experiences. People with middling levels of education also express significantly more national pride than do people with higher education levels living more cosmopolitan lives. No significant difference in national pride was found between men and women in the Czech data file. Concerning men’s role in protecting the nation, it was diminished after the Second World War in a majority of European countries, including the Czech Republic (the Czech Army has been fully professional since January 2005).

Conclusion

In undertaking the study described in this article, I sought to understand the specific reasons that influence general national pride in Czechia. Descriptive analysis based on national survey data reveals a variety of specific reasons that make Czechs proud of their country. Ordinal regression analyses based on representative European Values Study data confirm some of the reasons—political interest, instrumental political evaluations, happiness, and social trust—that explain general national pride.

However, the estimated models have only limited explanatory power. National pride is defined by large-scale identity processes not only at national level, but also at the relational and individual levels. Future research should pay less attention to the “league tables” of general national pride based on cross-national surveys. Instead, it should focus more on specific reasons why people select the categories of “not very proud” and “not proud at all” when asked “how proud are you to be a [COUNTRY] citizen?” Future research should help us understand the effect of individual achievements, interpersonal relationships, political interest, and instrumental political evaluations on general national pride.

Group-based emotions such as general national pride are dependent on an individual’s membership in a particular social group (nation) and appraisals of objects or events in terms of their relevance for the group. Membership in a nation is not, however, fully voluntary. Members of a nation who do not experience happiness, social trust, political interest, and support may express emotional nonconformity—less national pride. Nevertheless, they can sometimes feel and share collective emotions of national pride as the accumulation of many group-based emotional responses to a relevant societal event. When the Czech Republic’s men’s hockey team beat Russia’s in the Nagano 1998 Winter Olympics to win the gold, 30 years after the fall of the Soviet invasion to the Czechoslovakia, the whole Czech nation was proud.

Financial support

The research for this article was supported by the Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sports of the Czech Republic through project no. LG12023.

Author ORCID

Klára Plecitá, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5586-4672