INTRODUCTION

During the last several decades, significant progress has been made in the development of a Late Pleistocene megafaunal chronology in Eurasia, based on radiocarbon (14C) dating results (e.g., MacDonald et al. Reference MacDonald, Beilman, Kuzmin, Orlova, Kremenetski, Shapiro, Wayne and Van Valkenburgh2012; Stuart Reference Stuart2015). While the majority of these 14C dates come from bones and tusks of woolly mammoth (e.g., Stuart et al. Reference Stuart, Sulerzhitsky, Orlova, Kuzmin and Lister2002; Guthrie Reference Guthrie2004; Kuzmin and Orlova Reference Kuzmin and Orlova2004; Vartanyan et al. Reference Vartanyan, Arslanov, Karhu, Possnert and Sulerzhitsky2008; Kuzmin Reference Kuzmin2010; Nikolskiy et al. Reference Nikolskiy, Basilyan, Sulerzhitsky and Pitulko2010; Puzachenko et al. Reference Puzachenko, Markova, Kosintsev, van Kolfschoten, van der Plicht, Kuznetsova, Tikhonov, Ponomarev, Kuitems and Bachura2017), they also include several other megafaunal species (e.g., Orlova et al. Reference Orlova, Kuzmin and Dementiev2004; Stuart et al. Reference Stuart, Kosintsev, Higham and Lister2004; Pacher and Stuart Reference Pacher and Stuart2009; Kuzmin Reference Kuzmin2010; Stuart and Lister Reference Stuart and Lister2011, Reference Stuart and Lister2012, Reference Stuart and Lister2014; Markova et al. Reference Markova, Puzachenko, van Kolfschoten, Kosintsev, Kuznetsova, Tikhonov, Bachura, Ponomarev, van der Plicht and Kuitems2015; Kosintsev et al. Reference Kosintsev, Mitchell, Deviese, van der Plicht, Kuitems, Petrova, Tikhonov, Higham, Comeskey, Turney, Cooper, van Kolfschoten, Stuart and Lister2019; Lister and Stuart Reference Lister and Stuart2019).

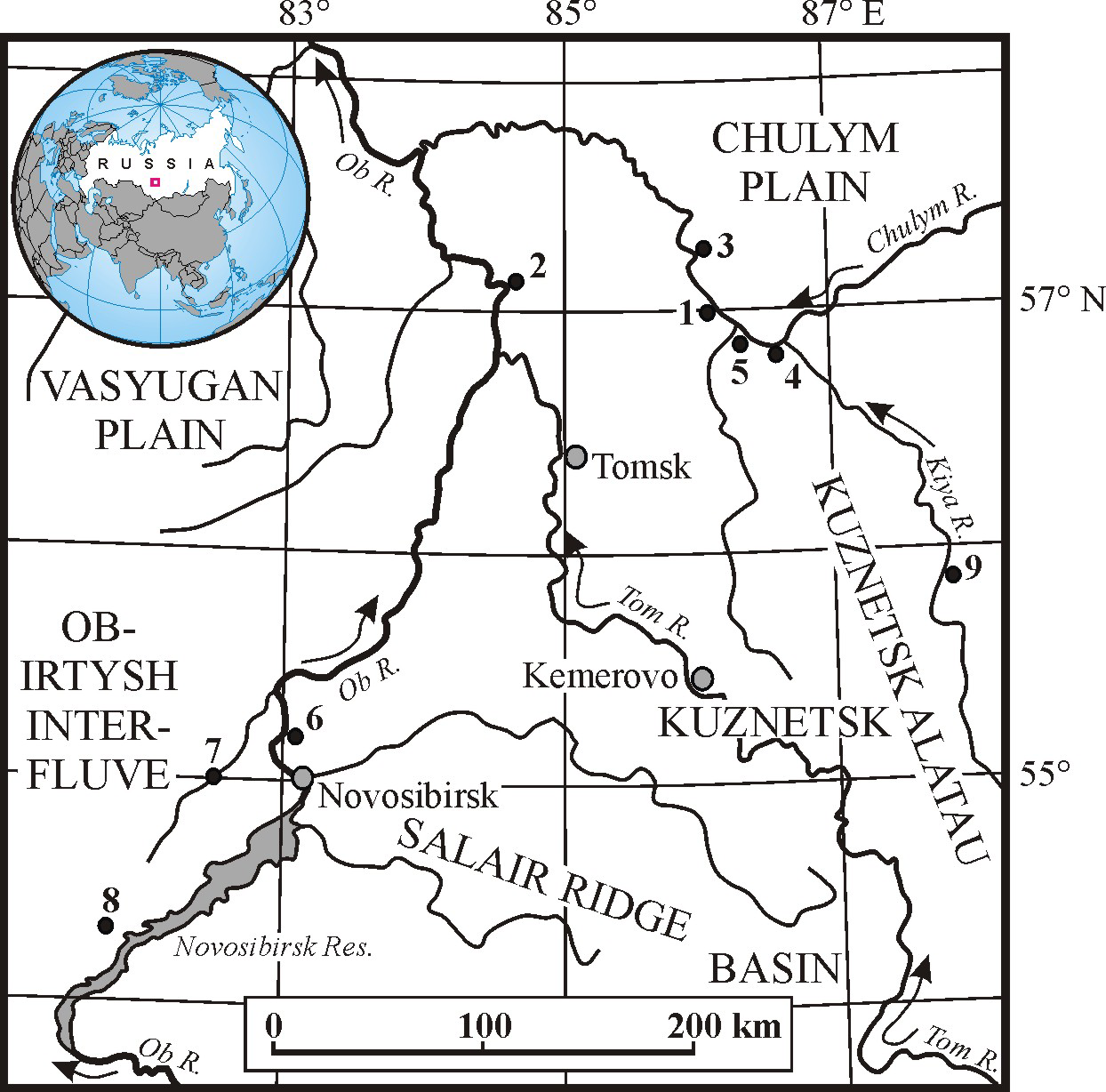

However, some regions remain relatively poorly studied, and the southeastern part of the West Siberian Plain (Figure 1) is one such area. In the last 10–20 years, new data has been accumulated in this area, and here we present the latest information on the chronology and environment of the large mammals that existed during MIS 3 (i.e. before the Last Glacial Maximum), and discuss the possibility of survival of some species which were previously considered to be extinct in Siberia and in Europe, by the mid-Late Pleistocene.

Figure 1 The main localities of the MIS 3 megafauna in southeastern West Siberia: 1—Asino; 2—Krasny Yar (Tomsk Province); 3—Sergeevo; 4—Zyryanskoe; 5—Bolshedorokhovo; 6—Krasny Yar (Novosibirsk Province); 7—Chick River; 8—Orda River; 9—Shestakovo.

The MIS 3 in Siberia can be dated to ca. 25–56 ka BP, or ca. 29–59 ka cal BP (e.g., Swann et al. Reference Swann, Mackay, Leng and Demory2005). In Siberia it is referred to as the Karginsky interstadial (e.g., Volkova Reference Volkova2002: 134–139), and it is equal to the Middle Weichselian interstadial in Europe.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

For this study, we used data collected during the last two decades in the basins of the Ob and Chulym rivers (Shpansky Reference Shpansky2018). Classic paleontological methods of identification and description were applied to the Late Pleistocene mammalian fossils, recovered from both in situ positions and surface collections on the riverbanks. Almost all of the localities in southeastern West Siberia that contain mammal fossils are of the subaquatic type, and bones are embedded into sands and sandy loams of alluvial genesis or paleosols (Shpansky Reference Shpansky2006, Reference Shpansky2018). Only at the Shestakovo locality are bones situated in loess-like loams of aeolian origin (Zenin et al. Reference Zenin, van der Plicht, Orlova and Kuzmin2000).

The measurements of proboscidean skulls were conducted according to methods developed by Dubrovo (Reference Dubrovo1966), and of teeth according to Garutt and Foronova (Reference Garutt and Foronova1976), with precision up to 0.1 mm. For comparison, skulls of the steppe elephant species Mammuthus trogontherii trogontherii Pohlig and Mammuthus trogontherii chosaricus Dubrovo from localities in Western Siberia and Europe, including the holotype of M. t. chosaricus (PIN PM KP 4874) from the Cherny Yar in the lower stream of Volga River, were used. The comparison of the last change of M3 teeth for woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius Blum.) and two species of steppe elephants from the Middle–Late Pleistocene of West Siberia and Europe was also performed. The results are presented as a bivariate plot with the most important parameters for teeth—thickness of enamel, and frequency of plates per 10 cm.

The 14C dating of mammalian fossils was conducted by both liquid scintillation counting (LSC; lab code SOAN) and accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS; lab codes UBA, GrA, and AA) (Tables 1–2). Methods of the pretreatment of bones are fully described in Kuzmin and Orlova (Reference Kuzmin and Orlova2004) for LSC; and in Zenin et al. (Reference Zenin, van der Plicht, Orlova and Kuzmin2000), Shpansky et al. (Reference Shpansky, Svyatko, Reimer and Titov2016), and Kuzmin et al. (Reference Kuzmin, Fiedel, Street, Reimer, Boudin, van der Plicht, Panov and Hodgins2018) for AMS. We applied the quality criteria for bone collagen suggested by van Klinken (Reference van Klinken1999) and Brock et al. (Reference Brock, Wood, Higham, Ditchfield, Bayliss and Bronk Ramsey2012), with the determination of the collagen yield, C:N ratio, and stable isotopes (δ13C and δ15N) values whenever possible. Samples with a low collagen yield (less than 1% weight) and C:N ratios beyond the 2.9–3.6 range were excluded. Unfortunately, this information does not exist for LSC and some of the AMS dates.

Table 1 New radiocarbon dates of MIS 3 megafauna in southeastern West Siberia.

Table 2 Radiocarbon dates for the Khozarian steppe elephant (Mammuthus trogontherii chosaricus) from southeastern West Siberia.

1 Calib Rev 8.1 software was used (available at http://calib.org/calib/); with ± 2 σ.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The list of mammalian species from the region includes ca. 20 taxa (Shpansky Reference Shpansky2018). The most common among them are Pleistocene bison (Bison priscus Boj.) and horse (Equus ex gr. gallicus Prat), woolly mammoth, and woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis Blum.).

The 14C values on mammal bones vary from greater than ca. 48,600 BP to ca. 24,400 BP (Table 1). The best-studied outcrop is Krasny Yar in Tomsk Province (Figure 1). Here new 14C dates were obtained from layers 5–6 (Figure 2), in the range of ca. 37,920 BP—greater than ca. 48,600 BP. Collagen parameters (yield and δ13C) are within the reliable range. For Layer 3, the 14C value is ca. 25,700 BP; also, a bone of Pleistocene bison was 14C-dated to ca. 18,500 BP (Shpansky Reference Shpansky2006). The age of cave hyaena (Crocuta crocuta spelaea Goldf.), ca. 43,140 BP, is noteworthy because no direct 14C dates from this region were previously available (see Stuart and Lister Reference Stuart and Lister2014). Along with a 14C value from Denisova Cave (Altai Mountains, southern Siberia) of ca. 42,300 BP (Stuart and Lister Reference Stuart and Lister2014, supplementary materials), this is one of the latest 14C dates for cave hyaena in West Siberia.

Figure 2 Krasny Yar (Tomsk Province) locality, with 14C-dated fossils.

Two bones of Panthera sp. (the ancestral form of cave lion) returned infinite ages of greater than ca. 46,200–48,600 BP. They were probably obtained from a redeposited context, and the true age could be older than MIS 3. Also, at the Zyryanskoe locality, a bone of Panthera spelaea Goldf. was 14C-dated to greater than ca. 44,500 BP (Table 1). This is most probably a redeposited specimen that appeared in the MIS 3 sediments.

The Sergeevo locality in the Chulym River basin (Figure 1) has three 14C dates on mammal bones. Layer 7 is dated to greater than ca. 44,900 BP; and Layer 4 to ca. 32,100–34,300 BP. Paleoenvironmental reconstruction for Layer 7, based on palynological and microfaunal (ostracods) analyses, show that the climate was cold and wet. The presence of a relatively large proportion of woolly rhinoceros in Layer 4 (ca. 12% of total bones), directly 14C-dated to ca. 32,100 BP (Table 1), can be explained by favorable conditions for this species in the river valley.

New data on the chronology of woolly mammoth in West Siberia, ca. 25,800–28,700 BP, were obtained from the Orda River and Bolshedorokhovo localities (Table 1). They are similar to the Shestakovo locality where it was 14C-dated to ca. 24,400–25,700 BP.

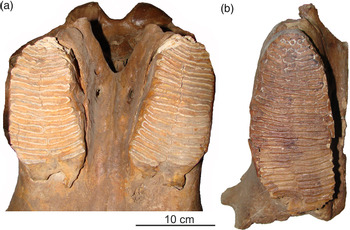

The most unexpected and intriguing 14C dates were obtained from the Asino locality in the Chulym River valley (Figure 1; Table 2) where the skull of a Khozarian steppe elephant (Mammuthus trogontherii chosaricus) was discovered (Figure 3). Previously, the latest finds of this species in West Siberia were known from deposits of the last interglacial (MIS 5e), ca. 115,000–130,000 years ago (Vasiliev Reference Vasiliev and Podobina2005; Shpansky Reference Shpansky2018). The Asino skull is moderately well preserved, with some damages to the occipital bone, the left side of the parietal bone, the left alveoli of the tusk, and near the nasal opening. The left zygomatic arch is missing. The Asino skull is similar to two Khozarian steppe elephant skulls from Layer 6 of the Krasny Yar locality (Novosibirsk Province; Figure 1) (see Table S1 in supplementary materials). According to Vasiliev (Reference Vasiliev and Podobina2005), the age of the Krasny Yar skulls could be the beginning of the Late Pleistocene, MIS 5e.

Figure 3 Skull of Khozarian steppe elephant (Mammuthus trogontherii chosaricus) from the Asino locality: (a) frontal view; (b) lateral view.

A distinctive feature of the Ashino skull is the relatively narrow facial part with a sufficiently large length and height. This is reflected in the narrow nasal opening, minimum width of the forehead, width of the supraorbital processes, and other parameters (measurements 7, 10, 12, 19, and 21; see Table S1 as well as Siegfried Reference Siegfried1956; Baigusheva and Garutt Reference Baigusheva and Garutt1987; Shpansky et al. Reference Shpansky, Vasiliev and Pecherskaya2015). The Asino skull has M3 teeth of moderate wear. The plates are very short, with parallel surfaces and without any bulges. In the anterior part of the crown, heavily worn plates are divided in half. The thick enamel is presented in rough folds. In the crowns, 15 plates are preserved in the right tooth, and 13 plates in the left one. It can be assumed that at least 5 plates were lost in each tooth as a result of abrasion. The last plates are at the very early stage of abrasion, and their surface was damaged in recent years in the museum.

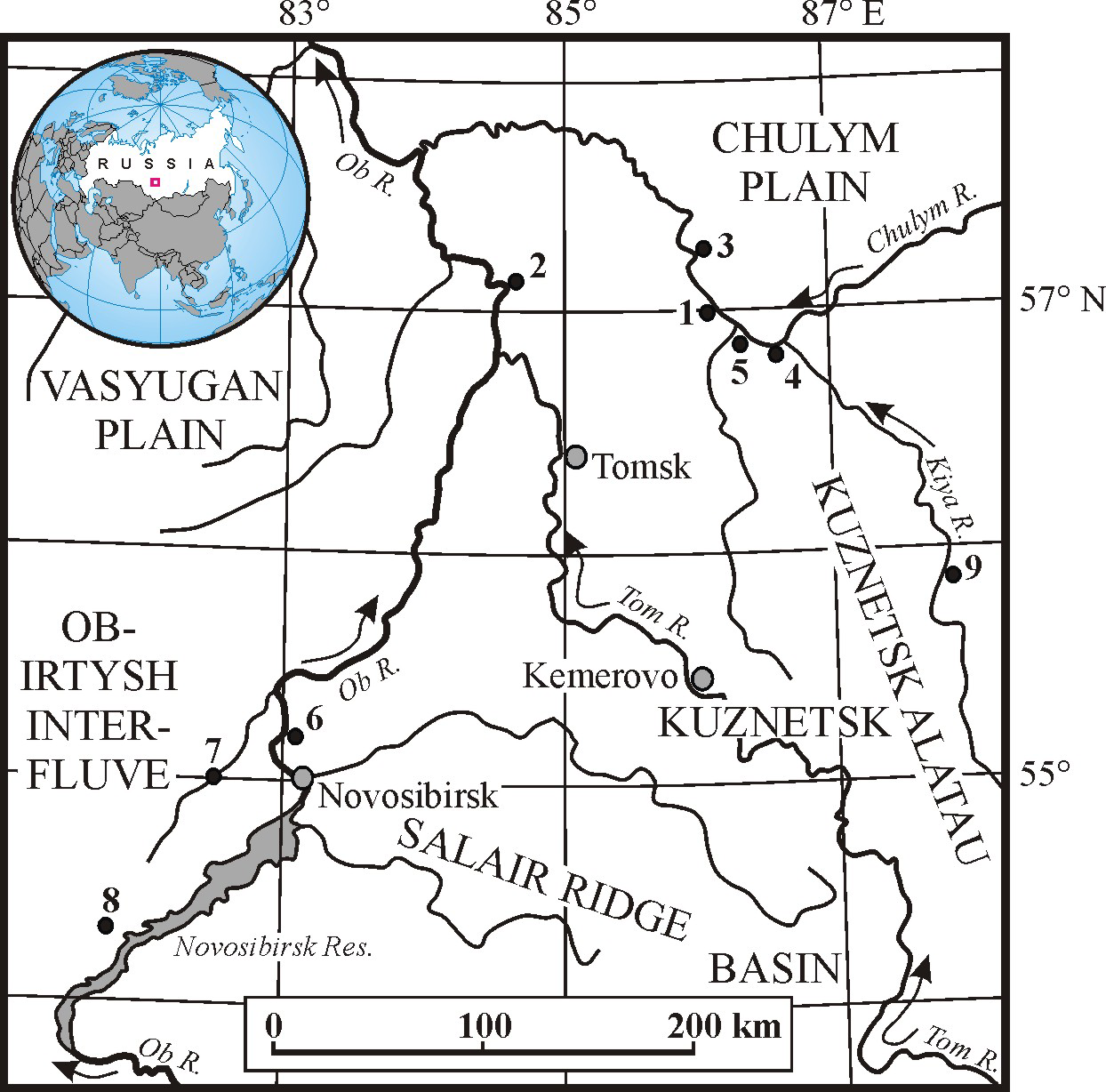

The morphology and morphometrics of the skull and teeth (Tables 3 and S1; Figures 3 and 4) testifies that this is the Khozarian steppe elephant and not a woolly mammoth. On the graph of the main morphometric parameters for M3 teeth of M. t. chosaricus, one can clearly see that the teeth from the Asino have the thickest enamel, while the frequency of plates per 10 cm is within the range of variability of this taxon (Figure 5). For comparison, the data on M3 teeth for woolly mammoth from Layer 4 of the Sergeevo locality is presented (Table 3). It is clearly different from the Asino M. t. chosaricus, and correlates with the typical Late Pleistocene woolly mammoth. At the same time, the 14C dates of the Asino and Sergeevo localities are very close (see Tables 1–2), and the distance between these sites along the Chulym River is about 20 km (Figure 1).

Figure 4 Occlusal view of the M3 teeth: (a) Khozarian steppe elephant from the Asino locality (TOKM 10300/3); (b) woolly mammoth from the Sergeevo locality (PM TSU 18/140).

Figure 5 Bivariant diagram of the M3 teeth of Khozarian steppe elephant and woolly mammoth (see original data in Table 3).

Table 3 Sizes (in mm) of the М3/m3 teeth for the Khozarian steppe elephant from West Siberia and Eastern Europe, and the woolly mammoth from Sergeevo locality. The upper values are for dex, and the lower for sin.

* Teeth are not completely erupted; measurements were made using the available part.

** Lower part of the Irtysh River basin (West Siberia).

*** Lower part of the Volga River basin (Eastern Europe).

**** Cis-Urals region, Kama River basin (Eastern Europe).

Two 14C dates were generated for the same specimen of the Khozarian steppe elephant (Table 2), and according to the criteria for the quality of collagen they can be considered as reliable. If true, the age of steppe elephant at Asino can be estimated as ca. 41,900–43,700 BP, or ca. 45,700–46,200 cal BP (median values of calibrated dates).

This information looks unusual, considering all previously known data on steppe elephant in Eurasia (e.g., Titov and Golovachev Reference Titov and Golovachev2017). Very late dates on steppe elephant, ca. 24,900–33,900 years ago (i.e., equal to cal BP), were reported from China (Wei et al. Reference Wei, Hu, Yu, Hou, Li, Jin, Wang, Zhao and Wang2010). However, they should be treated with caution because re-dating of several supposedly late finds of Pleistocene megafauna from China returned much older ages (Turvey et al. Reference Turvey, Tong, Stuart and Lister2013). On the other hand, a recent direct 14C dating campaign for giant rhinoceros Elasmotherium sibiricum showed that it survived in West Siberia and the Urals until ca. 33,300–34,400 BP (or ca. 37,500–38,900 cal BP) (Kosintsev et al. Reference Kosintsev, Mitchell, Deviese, van der Plicht, Kuitems, Petrova, Tikhonov, Higham, Comeskey, Turney, Cooper, van Kolfschoten, Stuart and Lister2019). This unexpected conclusion clearly demonstrates that our knowledge of the age of Late Pleistocene megafauna in Siberia is still limited. Obviously, more direct 14C and other dates (for example, U-series) are needed for the Asino fossils.

CONCLUSIONS

New data on the MIS 3 megafauna of southeastern West Siberia and its chronology has allowed us to increase the dataset of the 14C values on fossil mammals of Eurasia. While for some species—woolly mammoth and rhinoceros, and Pleistocene bison and horse—the chronological patterns are in the general range established earlier for northern Eurasia, the very late age of the Khozarian steppe elephant (Mammuthus trogontherii chosaricus), ca. 45,100–45,400 cal BP, allowed us to suggest the possibility of its late survival in Siberia.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The study was funded by the grant from the Russian Science Foundation (RNF), Project No. 20-17-00033. We are grateful to Chrono Centre, Queen’s University of Belfast (UK); Centre for Isotope Research, University of Groningen (the Netherlands); and the AMS Laboratory, University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ, USA), for help in 14C dating of fossils from Western Siberia. We are also grateful to two anonymous reviewers for their comments.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/RDC.2021.6.