Introduction

This is a sociological study on later-life care in domestic settings in Turkey from the perspectives of paid and unpaid carers. Caring in the context of later life in Turkey has mostly been studied from geriatric, psychological and social policy perspectives (Kalaycıoğlu et al., Reference Kalaycıoğlu, Tol, Küçükural and Cengiz2003). Although there are quantitative studies by formal institutions and research centres (e.g. Turkish Statistical Institute (TURKSTAT), Ministry of Family and Social Policies (MFSP) and Hacettepe University Institute of Population Studies (HUIPS)), qualitative studies into ageing remain scarce (e.g. Kalaycıoğlu et al., Reference Kalaycıoğlu, Tol, Küçükural and Cengiz2003; Baran, Reference Baran2005). The Turkish academic literature on ageing generally focuses on living arrangements and challenges, and health, social service and care-related needs of older people; however, the experiences of carers and caring work practices at home have not yet been studied. This needs to be remedied, as home care is the most prevalent form of later-life care in Turkey. As of 2015, only 0.36 per cent of older people in Turkey are in nursing homes and hospices (TURKSTAT, 2016); the remainder either live alone, or with close relatives or paid carers in domestic settings. This paper aims to explore this neglected area of care work practised at home by comparing formal/paid and informal/unpaid later-life care experiences, assuming body work as a crucial conceptual tool for understanding the different practices. After a brief demographic introduction into the context of care in Turkey, the article introduces the notion of body work that informs our analysis of the empirical data from a qualitative investigation of the carers’ experiences.

Background

The demographic and epidemiological transformation Turkey has undergone has narrowed the wide-based population pyramid of 1935–1975 featuring higher fertility and mortality rates, which have since declined (Koç et al., Reference Koç, Eryurt, Adalı and Seçkiner2010). The resulting population comprises a growing proportion of older people because of the decline in mortality and the increase in life expectancy. People over 65 constituted 4.3 per cent of the population in 1990, 5.69 per cent in 2000, 7.2 in 2010 and 8.5 per cent in 2017 (TURKSTAT, 2015, 2018). As such, later life has gained prominence for both families and policy makers.

In the traditional welfare regime of Turkey, the family and wider social circles are usually expected to provide care (Buğra, Reference Buğra2001; Kalaycıoğlu and Rittersberger-Tılıç, Reference Kalaycıoğlu, Rittersberger-Tılıç and Dikmen2003). Later-life care falls especially on female family members, making the family ‘the most comprehensive care institution’ (Tufan, Reference Tufan2016: 25). However, the family unit has undergone significant change due to both demographic transformation and the rural-to-urban mass migration since the 1970s. The decrease in the average number of household members and the evolving family structure from the traditional extended family to a more nuclear one has served to complicate later-life care (Koç, et al., Reference Koç, Eryurt, Adalı and Seçkiner2010: 58). Regardless, many nuclear families still live with or at least reside in the same building, street or neighbourhood as their older relatives (Ünalan, Reference Ünalan2000; Kalaycıoğlu et al., Reference Kalaycıoğlu, Tol, Küçükural and Cengiz2003; HUIPS, 2015).

Informal family care for older people has continued to exist even as the demand for commodified later-life care, whether institutional or home-based, is increasing. Family structure research shows that 6 per cent of all households have older members needing care (5% in urban, 9% in rural areas), with 10 per cent among the lower classes and 1 per cent in the high upper classes (MFSP, 2011: 278–279). Not surprisingly, lower-income households tend to care for their older relatives themselves in contrast to middle- and high-income families, who might opt for institutional and paid care (MFSP, 2011: 278). It is found that later-life care is primarily offered by daughters-in-law, children and spouses, and only 2 per cent of all households with older people needing care employ paid care-givers (MFSP 2011: 279). In fact, unless they live with their spouse (42.7%), older people mostly live with their children or other relatives (41.3%) rather than alone (15.9%) (MFSP, 2014: 100).

Care work, with all its physical and emotional aspects, is gendered and traditionally seen as women's work in Turkey; whether paid, professional or unpaid, it follows patriarchal/domestic ideology (Altuntaş and Atasü-Topçuoğlu, Reference Altuntaş and Atasü-Topçuoğlu2016). According to Altuntaş and Atasü-Topçuoğlu (Reference Altuntaş and Atasü-Topçuoğlu2016), since patriarchal ideology sees care as a private, intimate family matter directly associated with the body, it is provided within the family and rendered invisible, hence its ascription to women as part of the traditional role.

Conceptualising care work as body work

Until the 1990s, it seems sociology as a discipline neglected the body, embodiment and body work (Twigg, Reference Twigg2000a; Shilling, Reference Shilling2005; Gimlin, Reference Gimlin2007). On the one hand, paid body work was marginalised in traditional accounts of work (Shilling, Reference Shilling2005) and seen as an extension of gendered domestic duties; on the other, informal care has received much attention, especially from feminists examining traditional gender roles (Gimlin, Reference Gimlin2007). Despite the growing academic interest in body work and care work, in Turkey, these issues have received little sociological interest, albeit from different perspectives (e.g. Baran, Reference Baran2005; Rittersberger-Tılıç and Kalaycıoğlu, Reference Rittersberger-Tılıç, Kalaycıoğlu, Dedeoğlu and Elveren2012).

Twigg (Reference Twigg2000a) mentions that body work has commonly referred to the work of individuals on their own bodies for their own health/wellbeing, but that recently the term has come to include work on the bodies of others. More recently, Twigg et al. (Reference Twigg, Wolkowitz, Cohen and Nettleton2011) proposed a more restrictive definition, limiting it to formal paid labour to retain the analytic leverage of the concept.

Twigg (Reference Twigg2000a: 391) describes body work as ambivalent, potentially demeaning, closely linked with emotional intimacy, gendered, and involving some subordination and domination leading to ambiguity in social exchanges. She states that body work includes ‘practices of touching, manipulating and assessing the bodies of others’ (Twigg, Reference Twigg2000b: 139). Cohen and Wolkowitz (Reference Cohen and Wolkowitz2018: 43) emphasise that ‘body work involves (varying amounts of) embodied touch’. Particularly, care work as a form of body work is closely linked with the ‘negativities of the body’ and considered as ‘dirty work’, and the body in care specifically is silenced, because ‘carework is about dealing with human waste’ (Twigg Reference Twigg2000b: 143). Isaksen (Reference Isaksen2002) agrees that care work in its cultural construction is understood as dirty work and entails a ‘negative social reputation’. Specifically, Cohen and Wolkowitz (Reference Cohen and Wolkowitz2018: 43) state that the ‘social meaning of touch is altered both by the body of the person doing the touching and the body of the person being touched’. Similarly, Wolkowitz (Reference Wolkowitz2006: 146) defines body work as a form of service, with the body as the site of labour requiring contact with a frequently unclothed body and its products. Since emotions are involved, carers are usually women, underpaid, with the majority of the work done away from the public eye and thus rendered relatively invisible (Wolkowitz, Reference Wolkowitz2006: 148).

Graham's (Reference Graham, Finch and Groves1983) distinction between ‘caring for’ and ‘caring about’ comes up frequently in the literature, in that the former refers to ‘task-oriented physical labour’ or ‘practical acts of care’, while the latter means ‘relational, therapeutic emotional labour’ (England and Dyck, Reference England and Dyck2011: 208; Cohen and Wolkowitz, Reference Cohen and Wolkowitz2018: 44). Twigg (Reference Twigg2000a) states that there was a conceptual dominance in the debate of care in the 1980s and 1990s which ignored the body dimension. Emphasising the materiality of body work, Cohen and Wolkowitz (Reference Cohen and Wolkowitz2018) state that the emphasis on the centrality of ‘caring about’ in theories on care renders the physical work/body dimension of care invisible. James (Reference James1992), Wolkowitz (Reference Wolkowitz2006) and England and Dyck (Reference England and Dyck2011) maintain these two overlap, even merge, especially when care is carried out in the home. Thus, the spatial aspect of care is also assumed to influence care practices. As England and Dyck (Reference England and Dyck2011: 210) state, the home, a personalised spatial context where care work is performed, is a private space embedded with personal and symbolic meanings. They mention the home as both a workplace and a domestic area, with a dynamic relationship between the private and public spheres. Agreeing with Wolkowitz (Reference Wolkowitz2006) and England and Dyck (Reference England and Dyck2011), this study assumes the clear distinction between ‘caring for’ and ‘caring about’ to be misleading in the context of later-life care at home.

For the concept of body work, by embracing Hochschild's (Reference Hochschild1983) emphasis on the emotional aspect of work and aforementioned body work, it is assumed that care work as a form of body work (paid or unpaid) combines physical work with emotional work in the context of the domestic sphere. Moreover, the relationship between the cared and carer should not be reduced to only a client–worker relationship since they have a relationship within a specific social, cultural and economic context in the domestic sphere. In fact, as Cohen (Reference Cohen2011) notes, there are many actors involved in a relationship at the macro and micro levels in body work. In general, as Twigg (Reference Twigg2000b), Wolkowitz (Reference Wolkowitz2006) and Isaksen (Reference Isaksen2002) state, the practice of body work is multi-faceted; in particular, the care work practice is unique in terms of its connection with the ‘negativities of the body’, its involvement of the touch and manipulation of others’ bodies, and its silenced, invisible and tabooed aspects.

This article aims to understand later-life care at home from the perspectives of the carers: unpaid family care-givers, paid care-givers and nurses. Here, care work is taken as a form of body work, in keeping with Twigg's (Reference Twigg2000a) definition; however, it includes both paid and unpaid body work, as distinct from scholars only focusing on paid care work (e.g. Twigg, Reference Twigg2000a, Reference Twigg2000b; Wolkowitz, Reference Wolkowitz2006; Gimlin, Reference Gimlin2007; Twigg et al., Reference Twigg, Wolkowitz, Cohen and Nettleton2011). Like Cohen (Reference Cohen2011), who referred to Hochschild's (Reference Hochschild1983) emotional labour/work distinction, I also follow Kang (Reference Kang2010) and assume that ‘body work’ is any work performed on the body of another, and includes ‘body labour’, which is, specifically, commodified body work.

Disregarding the bodily aspect of later-life care or only seeing paid care work as an extension of informal family care and emphasising only traditional gender roles in an analysis of care work seems insufficient. It also seems wrong to view care work as something where market rationality applies, excluding its emotional and cultural aspects. Twigg (Reference Twigg2000a) mentions the body-work aspect of care work being neglected in community care. While I agree, limiting body work to paid labour could exclude the body work-related nature of informal care and care-givers’ practice in the context of home-based later-life care. A more holistic view of later-life care in terms of body work could be obtained through a comparative investigation of the relationships navigated – with family members, for instance – as well as the similarities and differences between paid/formal and unpaid/family care practices. Here, care work practices are examined by considering the relationships around the person being cared for, the locality, including the tensions related to the workplace/public sphere and home space/private sphere and the experiences of carers, as well as the tension between ‘caring for’ and ‘caring about’ involved in the emotional and physical aspects of body work. In this regard, the study investigates how care work is experienced, practised and managed, and how the tensions are negotiated differently in the domestic atmosphere for older people in terms of body work by paid and unpaid carers at home.

Study methods and sample

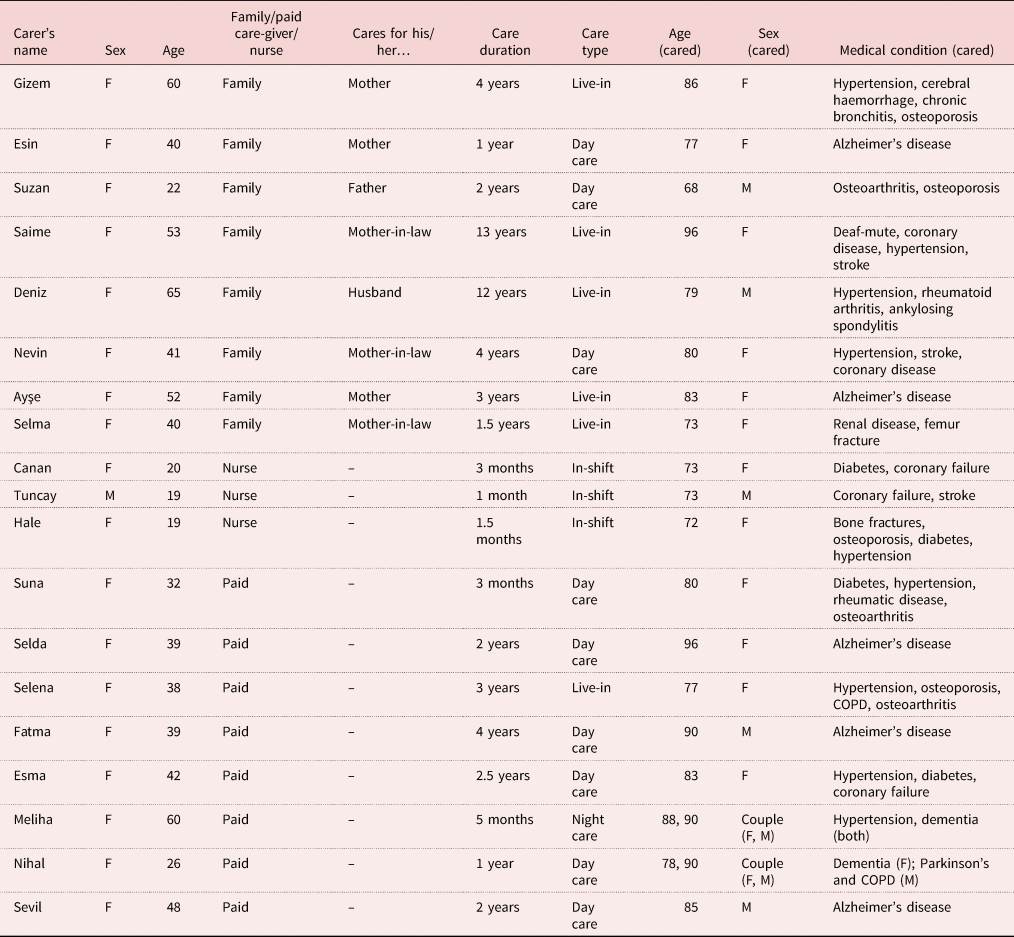

Focusing on later-life care via carers’ own interpretations in order to illuminate their personal conceptualisations and experiences, the study employs the qualitative research method based on primary data. In-depth, 90-minute (on average) interviews were done face to face with 19 carers providing care for people aged 65 and over, living at home in Ankara in 2012. The sample included eight unpaid family carers, eight paid carers and three professional carers. The participant profile is given in Table 1.

Table 1. Detailed information about the care-givers and the older people in care

Notes: F: female. M: male. COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Snowball sampling was employed. Through personal contacts and the neighbourhood chiefs’ guidance, paid care-givers were contacted in high- and middle-income neighbourhoods, close to the city centre; family care-givers were found in different low- and middle-income neighbourhoods; and nurses were selected from hospitals. Participants were asked about their socio-demographic and socio-economic status, work and caring history, reasons for providing care, working/caring conditions, details of care work duties, positive and negative aspects of care work, and their reflections on their care-work experiences.

Ethical procedures required for social research were followed, including informed consent, and information was provided regarding the aims and procedures, expected interview duration, as well as the right to withdrawal, anonymity and confidentiality. It was confirmed that the interview questions lacked any harmful content. The field interviews took place in a relaxed atmosphere. The interviews were recorded, with participants’ permission, transcribed and analysed thematically and conceptually into categories. Names with any identifying features were changed.

The first group of study participants – the unpaid family care-givers – were all women and cared for an older relative in their own home or in the older person's home. They were the daughter, daughter-in-law or wife of the older person. All had little education, lived in low-income households and were rural-to-urban migrants. None was trained for caring work, but most professed previous experience, i.e. a childhood spent with grandparents or having observed their mothers or other female relatives doing similar work.

The second group consisted of paid care-givers, all women, employed to care for an older person(s) at home. Except for one immigrant carer, all had a low level of education, low income and were rural-to-urban migrants. The majority of their husbands were janitors in apartment buildings in middle- or high-income neighbourhoods. Paid care work is common in these neighbourhoods, so they were familiar with the demands of care work.

The third was composed of one man and two young women nurses providing part-time home care for older people. These carers primarily worked in the cardiovascular and surgical intensive care units in hospitals. They found their clients through their informal professional networks. Their patients were from middle- or high-income families, post-operative, terminal and machine-dependent. They provided care for the same patient on an average of three days a week for two weeks to three months. This duration varied according to family members’ demands and the condition of the patient. The nurses were single, relatively young, new to the profession and from low-income families.

Conditions surrounding the care work

Among the participants, the family care-givers spend most of their time with those they are looking after, leaving the home only for care-giving-related errands like pharmacy runs. They mention reluctance to leave the older person alone despite having limited personal time. They describe care work as physically and mentally exhausting, extending through day and night. Many interviewed family care-givers have health-related complaints like herniated discs and/or depression exacerbated by their daily care practices. Also mentioned are interference, social pressure, gossip and under-appreciation from close kin networks, especially their siblings. Most of the family care-givers receive a government stipend for later-life care, which usually results in stigma from their close kin network, social disgrace and accusations of greed.

The paid care-givers interviewed earn less than minimum wage, work long, unpredictable hours and lack social security. Some, especially if single, are live-in, while others provide care only during the day or night. A few carers looking after husband and wife couples in the same home also receive low wages. The paid care-givers work an average of 12 hours a day, six days a week, while live-in carers work seven days. Those living close by have flexible working hours, but their proximity can lead to employers demanding extra hours. Among the paid interviewees, Suna cares for an 80-year-old woman in her building where Suna is the caretaker. She says:

I stop by to change her pads before bedtime, do chores she requests and take care of her cats. When you love someone you tolerate them, even if they defecate, you deal. I love auntie; when she is doing badly I stay overnight. What would I do if something ever happened to her?

For the interviewees, spatial proximity can result in flexible and unpredictable working hours, as in Suna's case. Interestingly, paid care-givers who have a warm relationship with the older person, rather than complain of the workload, frequently mention doing this work willingly. Also, many paid care-givers express job insecurity in the event of the older person's death. However, with a controlling employer setting job-related rules, job insecurity causes the care-giver to yield to employers’ demands of unpaid overtime and additional domestic work like cleaning, resulting in more varied tasks. The nurse participants also have long working hours but lack such extra tasks. They work full-time at a hospital, and provide home-based medical care 12 hours a day, two or three times a week for older people to supplement their income and gain professional experience.

The care-givers in the sample have multifarious responsibilities. These include bodily/physical tasks like health-related tasks, hygiene-related bodily care tasks and daily routines for the body (e.g. lifting or turning a bedridden body, using medical devices, decubitus care, administering scheduled medication, feeding, monitoring the older person's diet, exercising, bathing, cleaning after defecation, shaving, nail clipping, brushing teeth/dentures and cleaning mouth, washing hands and face, combing hair, changing pads, dressing and undressing, etc.); social, intellectual and emotional support such as reading out loud, conversing, taking walks together indoors or outdoors; and domestic chores like cooking and cleaning. Professional care-givers’ responsibilities are more clear-cut and include medically determined, intervention-based tasks, while unpaid family care-givers and paid care-givers’ responsibilities have a broader range. While crucial also for family care-givers, paid care-givers’ responsibilities depend on the type and the severity of illness(es) and level of disability of the care recipients and on the family member. Care-givers with bedridden patients focus more on bodily care while for relatively self-sufficient older people, the care involves social support and domestic duties like cleaning, cooking, shopping and companionship. For example, among the paid care-givers, Georgian migrant Selena is a live-in care-giver for a 77-year-old woman living with many diseases, each requiring medical care. She says:

I care for her, give her a massage, her medication, her oxygen tube, her Ventolin [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease medication], check her BP [blood pressure], administer insulin, take blood sugar levels and take her to the doctor frequently. Plus, I prepare meals, run errands at the store, bank and do housework if I have time.

She also expresses this work is labour-intensive and isolating:

I don't have much of a social life because it is 24/7. I have one day off a week that I can't take because I can't bear to leave her alone, worried something might happen to her. I need the money. We need each other.

Among the participants, the progression of older people's illness(es) is observed to influence the duration and content of care work, rendering the content of paid or unpaid care work difficult to standardise. All carers who care for those with Alzheimer's, especially, encounter new situations depending on the phase of the disease. Among the paid care-givers, Fatma, who cares for a 90-year-old man with Alzheimer's, says, ‘At first, everything was normal. We would chat, he would read to me, take care of himself but now he can't even eat on his own. So sad. Things always change. He needs constant care like a baby now.’ Thus, care work can be dynamic and changeable.

The physical and emotional aspects of the body seem enmeshed. The tasks involved in care work defy a clear classification, with the home as the context. Also, the existence of relationships between and among the carer, those contributing to – or, as the case may be, interfering in – the care; the type and stage of the patient's illness; and the nature of the work carried out all mean that the ‘caring about’ and ‘caring for’ aspects of the body work are indeed intertwined. Therefore, doing body work for an older person is not simply about physical effort; it is also emotional/relational and involves the management of the body. This study also finds that the work done by the different care-giver groups involves multifarious tasks addressing these interconnected aspects that will be explored later. A true grasp of care work as a type of body work requires a closer look at these relationships, at how the carers themselves perceive and experience the care they offer and, last but not least, the space in which these relationships exist, where the body work is conducted and the actors act, i.e. the home.

Relationships involved in care work

In the study, the type of later-life care and the tasks involved therein vary by type of care. The relationships between the carer and the older person can change based on the wider sets of relations in which these are embedded. In unpaid family care, for example, care management seems to be influenced by other relatives, whose involvement is often seen by the carer as interference. Unpaid carers here mention frequent criticism from siblings, revealing a web of relationships imbued with power dynamics, usually to the detriment of the care-giver, who finds such interference undermining and discouraging. Close relatives seem to commonly belittle and criticise, while friends, neighbours and others within the network show appreciation for the family care-givers, commending them for being ‘dutiful children’ (daughters, daughters-in-law or sons). The family care-givers mentioned occasional support from other relatives who shared the care work, but the decision-making power could shift over time and was associated with tensions.

Ayşe, an unpaid carer, has taken care of her 83-year-old bedridden mother with Alzheimer's for three years. Ayşe's siblings took turns providing care before Ayşe, upon discovering that her brother's wife physically abused her mother, decided to provide care at home. Deeper into the conversation, Ayşe frequently emphasised physical and mental exhaustion and the challenges in caring for her mother (e.g. refusing to take medication, spitting out food, handling her faeces, smearing her faeces around the house, sudden screams, etc.). However, she reported feeling happy to be fulfilling her responsibility to her mother. She mentions that her siblings disrespect her mother and have suggested putting her in a nursing home, but she says she feels emotionally and spiritually obligated, saying:

Ah, how can I not look after her? I am always reminded about how she raised me. She would stay up nights; wait by our bed when we were sick. It's my turn to be the mother now. Anyone with the fear of God inside them would look after [their mother].

Dejectedly, she mentions her brothers’ belittlement and even accusations of greed for the government stipend, even as the community commends her for taking care of her mother.

While paid care work is seen as demeaning since it involves taking care of someone's body with its ‘negativities’, unpaid family carers in the study are seen as doing honourable work, fulfilling their traditional duty to the older family members in the spirit of reciprocity. Those that do not care for their parents are shunned and shamed. This feeling comes across in all family care-giver interviews. Under such close social surveillance, the carers seem to feel the need to display how well the older person is being cared for (as apparent from attire and appearance, cleanliness and affection shown). Many participants mention feeling pressured to prove themselves against close relatives’ incessant interference, judgemental attitude, constant criticism and accusations of greed for the government stipend, as in Ayşe's case. So much physical and mental effort spent on managing relationships and impressions beyond merely caring for the older person clearly shows how much emotional work, in addition to and with relation to physical work, is involved in the job for family members offering care. Ayşe's case illustrates the complex and changing nature of family relationships in which care work takes place. The emotional labour extends beyond the carer and cared for and is further complicated by the web of familial relationships. Ayşe's comment illuminates the blurred distinction between ‘caring for’ and ‘caring about’ and its connection to wider social norms and expectations. Although unpaid, the work described obviously involves labour that harbours obligations and expectations constraining the autonomy and independence of the care-givers. Therefore, the dichotomy between paid and unpaid work here seems slippery. While other actors’ interference on the ageing body and traditional pressures act as a kind of control mechanism, they cause the interviewed carers to expend additional emotional effort; the care and modification of the older person's body, therefore, with the addition of other actors, renders the ageing body the site of a power struggle. This results in an effort on the part of the interviewed care-givers, like Ayşe, to present the older body in such a way as to prove the quality of the care being offered.

For the paid care-givers in the study, the relationships with those cared for is shaped by the type of illness of the care recipient, whether they are bedridden, the family members’ attitude towards the care recipient and care-givers, and the duration of the care. It ranges from a more friendly relationship to an employer–employee type relationship. A friendly relationship, usually a more paternalistic relationship, is similar to one that may exist in the case of the family care-givers here. These care-givers feel they live among family, and they treat the care recipient like they might do a close relative. They display informalisation, speaking to their charge as they would to a relative, calling them mother, father, aunt, uncle, grandfather or grandmother. The duration for which a care-giver has cared for the same older person and any emotional attachments eventually developing seem to be crucial factors in this kind of relationship. Strict employer–worker-type relationships, with inflexible working hours, and clear-cut duties and responsibilities and close monitoring, are very rare. This kind of relationship is mostly only seen in our study in cases where the person cared for is in the late stage of a serious illness such as Alzheimer's. Even the paid care workers in the study feel the scrutiny and constant judgement of the older person's family members and feel the need to make what could be called a presentation of the body of the cared. In one case, an old man lives with Alzheimer's in its final phases, but his carer, Fatma, dresses him in a suit and tie instead of casual clothes. Therefore, for our interviewees, emphasising the emotional aspects for unpaid carers but only the material aspects for paid carers offers a very incomplete picture.

For the nurses interviewed, the relationship seems to be more professional. Their duties are medically determined; they are the decision-makers and their care work is more of a medical ritual. They wear professional attire including protective equipment like gloves and masks and use medical jargon, which has a medicalising effect on the cleaning tasks involved in care work. The participating nurses appear not to see any distinction between medical care and cleaning practices. Their relationship to the care recipients, the recipients’ family members and their own co-workers are structured by medical rules, even when family members contribute to the caring and application of medication. Interestingly, they still treat those they are looking after as one might a relative, emphasising the ease and intimacy this approach brings to the relationship and practice. A nurse participant, Hale, says:

Our approach is different than doctors’. The [patients] are not objects for us. It's not just reposition the patient, administer medication and then you're done. We think ‘this person could have been my mother’. The more time you spend with the patient, the more attached you become, wonder how they're doing even when the work is done. Initially, you might not care, but later you start thinking, ‘Aunt Nesrin's nails seem longer, let me clip them’, or ‘her hair seems greasy, let me just wash it’ or ‘I'll just pluck her eyebrows’. Aunt Nesrin used to take care with her appearance when she was younger, you want to raise her spirits.

Although these family care-givers see their older relatives as ‘ancestors’, and paid care-givers approach and address the older person like a close relative, the older people are clearly ‘infantilised’ by both, especially when dealing with ‘negativities’. Despite ‘informalising’ the relationship, the carers tend to view the older person as a helpless infant while performing care work duties involving physical contact and cleaning. Paid women care-givers caring for old men frequently say, ‘He is like a baby; I don't see him as a[n older] man. He needs me to take care of him.’ The asexuality of older people is also emphasised, especially by paid women care-givers caring for older men. This infantilisation is not seen among the nurses. Some unpaid family care-givers like Ayşe also tend to see those under care as infants if their charge is bedridden or lacks self-sufficiency but with a different emphasis: reciprocity between generations.

Perceived responsibilities of care work

Care work is understood and conceptualised differently across the three groups in this study. During the interviews, when discussing duties and responsibilities, family care-givers frequently mentioned traditional obligations. Those caring for their parent emphasised the importance of reciprocity, saying it is their ‘turn’. Despite exhaustion, even depression, complaints are rare among these family carers, who say, ‘our older parents are our ancestors’.

Like in other cultures, in Turkey, care work follows traditional gender lines. Except for nurses, all interviewed care-givers believe that it should be women providing care. Though care work prevents paid employment and a social life, restricting family care-givers to the home, they have internalised and reproduce the idea that it should be the women that care for parents (in-law). Those who do not are judged and excluded from the social network. Institutional care, in fact, is seen as ‘shame’ upon the family. Doing their traditional duty, these unpaid family care-givers do not feel they have a choice in the matter, and also frequently express a familiarity with later-life care due to their previous experiences with infant and child care, including caring for grandchildren. A participant, Nevin, spent four years caring for her mother-in-law, who had had a stroke. She was responsible for the bathing, feeding and cleaning up following urination and defecation. Though initially inexperienced in later-life care, she says, ‘We were born used to this work. My mom took care of her mother-in-law, then I raised my kids, and now I am taking care of my mother-in-law just like her. It's a circle.’ When asked why it should be women that provide such care, carers said that women are ‘predisposed’. This perception is both internalised by women and transferred from one generation to another. Asked who cares and should care for ageing parents, both paid and unpaid carers stated that it should be the son – who is traditionally valued somewhat more than a daughter – who does this in Turkish society. Nevin states, ‘The other children weren't interested, they had excuses. In our society people feel it should be the sons’ job to take care of their older relatives.’ Not surprisingly, it is the daughter-in-law who ends up doing the actual care-giving. Managing the relations involved, especially when the carer is a daughter-in-law, is more challenging as they mention greater pressure, constantly trying to prove themselves and manage interfering relatives. It seems the conflicts are greater not with the older person but their relatives, requiring quite a lot of problem solving, patience and managing skills on the part of the carer.

Selma cares for her mother-in-law, living with various illnesses, now bedridden due to a femoral fracture. Selma's care work is labour-intensive; she has difficulty especially with cleaning after defecation and providing decubitus care, and describes her home space as a ‘prison’. Yet, vehemently opposed to nursing homes, she maintains that family should provide care. She explains that older people prefer to spend their last days in their sons’ household. Selma's own grandmother, however, was cared for by the daughters, and the community disapproved of the son's lack of involvement. She sees caring for one's elders as a religious duty.

Religious belief appears as a significant influence on the care-work perceptions of the interviewees, all of whom are Muslim. More than half, paid and unpaid, emphasised the role of ‘the fear of God’ in what they did and being rewarded by God in the afterlife. Among family care-givers, this is at least as influential as traditional obligations. It is noteworthy that each time the challenges of dealing with intimate care tasks came up during the conversations, both paid and unpaid carers brought up such religious beliefs.

Although the nurses seemed at ease discussing bodily tasks using medical language, both paid and unpaid carers seemed somewhat reluctant to mention such tasks. Interviewees in all three groups reported initial revulsion and nausea due to noxious smells, and having to touch and clean body parts, but added eventual acclimation. Also, carers in all three of our groups seem to empathise with the cared, trying to provide the best possible care. The former lawyer with Alzheimer's cared for by Fatma lives with his daughter, receiving round-the-clock care from two care-givers taking shifts since his disease progressed. Fatma mentions the initial discomfort of the older man as well as her own shyness, then gradual mutual acclimation:

[He] was also that way at first; embarrassed, uneasy. Three years ago, like when I was helping him get dressed, he would say ‘this is shameful, my girl!’ I was shy at first, too. Not anymore, because I see him like my father. I think you should treat them like a relative, because you earn your bread thanks to this man. Initially I didn't think I could take it if he urinated or defecated, but now I am used to it. You naturally feel some disgust at first. There were times I couldn't eat. But, as I said, you get used to it over time. I use masks and gloves; I still do. I see him like my close relative. When he's doing badly, I am sad too.

This excerpt exemplifies how these paid carers informalise the care work, emphasising the asexuality of the older person and cope with body work by distancing themselves from bodily fluids through the use of gloves. The use of gloves and masks against bad smells, bodily fluids and discharge is common among the interviewed paid, professional and unpaid care-givers.

The significant emotional aspect of care work frequently came up in all interviews. They stress affection, compassion, mutual trust, warmth, patience and kindness as essential to care-giving. All paid care-givers mention eventual affective attachment to the cared. Especially those who feel like a member of the family of the cared state, ‘I love older people. If I didn't love them, I couldn't do this. Love is the most important thing.’ A paid care-giver, Meliha says: ‘Being patient, soft-tempered, kind and loving are key. Do it with love; don't hurt his feelings. Then you won't burn out. Sure, it's for the money, but you should love your job and get used to it.’

All care-givers here, except the nurses, believe that women should provide care for other women, and men for other men. Gender differences between the carer and the person cared for seem to be a problem for both parties and a source of social disapproval here. A participant, Sevil, has been caring for an old man with Alzheimer's for two years. He is ambulatory and speaks, but can get forgetful and occasionally urinates around the home. He has a son living far away, who left when his disease became a big practical problem and has not visited since. Sevil provides care during the day, but the man stays alone at night. She is severely underpaid and works 14 hours a day, seven days a week. Though she seems to think of him as a father, she has issues with him being a man and faces her family's disapproval, but perseveres for financial reasons. She also feels compassion:

I am here all day with no one checking in. I am a stranger, yet I show interest. And it is a man. Sure, he is like my father and nothing else. You have no choice but to care; I help him with his bathing. I don't see him as a man. Like, my sister says she could never do it. A strange man. But I have to. It's not easy earning a living. I have able hands and feet. Thank God! A man is hard [to care for], but I take him for my father and I look after him as if here were a child. We are dependent on each other. Why would I come if he were not in need? We have gotten used to each other … This work cannot be done without compassion.

Like Fatma and Sevil, seeing the person they care for as a family member, pretending they are caring for a baby, and seeing and treating the older person as asexual may be a strategy for paid care-givers to deal with having and performing a job socially considered demeaning. Most participants emphasised outside disapproval and have been told, ‘They're not even related to you’, ‘Is this something to be done in return for money?’ or ‘Why are you cleaning up after a stranger?’ For example, Sevil states that her family strongly disapproves of her caring for an older man. Paid care-giver Nihal takes care of a 78-year-old man whose phlegm is expelled by a machine. She also mentions initial revulsion, but that she is now used to it. Responding to others’ disapproval, she says, ‘He's my dear old gramp. Those around me ask me how I can deal when he's not a relative, they say they never could, but I like older people, he's like a grandfather to me.’ The relationship construct seems different when the carer is paid, based on how common infantilising or asexualising descriptions seem especially when mentioning ‘negativities’. The interviewees frequently stated, while touching the body of a close relative seems normal, purposefully choosing to touch a stranger's body for the sake of a job can be judged negatively in society. The paid carers’ mentions of a father or baby rather than an ordinary man seem to be a mental construct or emotional effort, i.e. a coping mechanism for dealing with body work others may find offensive as well as an effort to convince those around them of the virtue of their work. The unpleasant aspects of body work are rarely mentioned by unpaid carers and taken as a traditional duty, while nurses report using gloves and gradually overcoming their initial unease, similar to the others.

The home as a space of care

What participants mean by the home, how they define and use the home space varies across the three types of care-givers interviewed, as does the extent and progression of the older patients’ illnesses, the nature of the duties of the care-givers and the kinds of relationships surrounding home care. The unpaid family care-givers see the home space as a private space, whereas the nurses see it almost like a hospital unit. However, the paid care-givers’ perceptions of the home space vary: some see it as a workplace – a public space, and others see it as their home – a private space, according to the type of relationship. In a paternal and warm relationship, over time, these care-givers see the private space of the cared as their own home. The participants, like Selda, who cares for a 96-year-old woman with Alzheimer's, typically say, ‘I tell people I have two homes. She's like a mother to me now. I cook for all of us. Her children call often and check. They expect more since we live close.’ They develop a sense of familiarity with the home space and feel they have command over it, unless the older person's family members interfere. A controlling family member and a more professional relationship can limit these care-givers’ use of the home space, rendering it primarily a workplace. The severity of the older person's illness also determines which spaces of the home the care-givers use. If the older person is ambulatory and mostly self-sufficient with personal hygiene, the care-givers may use the spaces in the home other than the bedroom for tasks like cleaning and preparing food. However, all care-givers interviewed reported spending time in the bathroom, at least to assist with bathing.

For the interviewed nurses, the meaning of the space of care seems different. Their charges are bedridden, seriously ill, and dependent on machines and the primary care space is the bed itself. The cared has no private space other than the bed, which is usually in the living room. It is in this bed that all bodily tasks are performed: the patient's blood is drawn, their body is wiped down, genital areas cleaned, pads changed, hair washed, nails clipped, decubitus ulcers treated, and the patient is dressed, undressed, shaved, fed, exercised, moved around, medicated and otherwise treated as necessary. In the home space, the rooms are utilised for different needs; however, the meaning of private space seems to be lost there for bedridden older people. For the participating nurses, the home functions as a kind of intensive care unit where many interventions are possible. Yet the nurses interviewed still accept that it is a private space for the cared, commonly saying, like young nurse Canan, ‘we are sensitive when we provide care for older people; we maintain their dignity, whether they are unconscious, unable to speak, or to move’.

For the interviewed unpaid family care-givers, the home remains a private space where traditional responsibilities are fulfilled. They feel isolated from the external world, even trapped. Among the participants, 65-year-old unpaid care-giver Deniz cares for her husband, who has had difficulty walking and meeting basic needs for many years. Deniz describes her isolation:

All my life, ever since I got married, I've had to give care. I gave up on my dreams of getting an education and a job. First it was my husband's bedridden mother, then his dad got sick and then I had babies. Twenty years I cared for all of them. I couldn't save my own life. Then my husband got sick. I'm just so tired of it all, sick of being in this house. I do everything, feed, bathe, change. No matter how frustrated I get I have to care for my husband. Sometimes I run out for an hour and it helps, but I'm always worried. I come back and everything's the same. It's a prison.

Though reluctant to complain about the care work and not wanting the cared to be left alone, they mention that their world is restricted to the home, away from public and social spaces. On the one hand, the home is a space of care for older people, and, on the other, it is a ‘prison’ for the care-givers, who are still reluctant to complain. Many unpaid family care-givers did not choose care-giving, but traditional norms about care work, especially the one prescribing intergenerational reciprocity, have compelled them to do so. They state that the outside world can begin to feel alien. Moreover, the unpaid care-givers, particularly whose charges are bedridden and who receive the government stipend, commonly draw similarities to paid care, as unpaid family care-giver Selma says, ‘I am a worker working for a pittance, and this is my prison.’ This is common among daughters-in-law and those who are forced into care-giving.

Discussion

This study examines how care work is practised by different types of carers in the Turkish context, comparing the perspectives of unpaid family care-givers, paid but non-professional care-givers and professional care-givers. Some similarities and differences across these three groups are found.

As Wolkowitz (Reference Wolkowitz2006) and Twigg (Reference Twigg2000b) emphasise, care work is invisible, silent and ambivalent in nature. It is hidden, confined to the home, as a private space. On the one hand, modern society ignores ageing, the needy body and death due to a fear of bodily decay and death; on the other hand, policy makers overlook the difficulties involved in the conditions of care work, whether paid or unpaid. If anything, later-life care is more concealed because it is concerned with tasks commonly deemed unpleasant (Twigg Reference Twigg2000a, Reference Twigg2000b). In the sphere of care work, the binary oppositions of modernity produced by Western thought – body versus mind, woman versus man, old versus young, domestic versus public, nature versus culture – all come together to reproduce the subordinate status of subjects. ‘Women’ do care work for ‘older’ people, performing the management of ‘bodily’ issues in the ‘domestic’ sphere. These subjects and their tasks are viewed as following the rules of ‘nature’ not culture. So, not surprisingly, care work, whether paid or unpaid, is invisible, silenced, hidden in the private space of home. The findings say that its silence seems to be related to its bodily aspect.

From the findings, the nature of care work seems dependent on the type of illness, whether the person being looked after is bedridden and the relationship with other actors involved in the management of the aged body. As Twigg (Reference Twigg2000a, Reference Twigg2000b) emphasises, it is ‘dirty work’ and involves the management of and dealing with bodily fluids such as urine, faeces, vomit and phlegm. Despite the interviewed family care-givers’ reluctance to talk about bodily tasks due to their close emotional relationship with their older relatives and concern for their dignity and privacy, performing these ‘dirty’ tasks remains challenging. They try to avoid the repulsive aspects by using gloves and masks as distancing techniques, but use such techniques less often than paid care-givers. The professionals interviewed always use these elaborate distancing techniques. While these care-givers fear ‘getting dirty’ while dealing with human discharge, they report observing that the older people seem to feel discomfort during cleaning, and decubitus care, as well as embarrassment and shame while bathing and undressing. The use of masks and gloves seem to alleviate such feelings. Furthermore, the infantilisation of older people under care, the forming of intimate, pseudo-familial relationships and gradual acclimation to the body of older people all have facilitating effects on coping with the bodily aspects of care. Based on the observations mentioned by paid and unpaid carers, older people, especially men, under care, seem to feel that their dignity and power are diminished. As coping strategies, care-givers emphasise the asexuality of older people or how they regard them as infants. Based on the findings, while many paid care workers, like Nihal and Sevil emphasise, receive disapproval within their close social network because they ‘touch’ others’ (especially men's) bodies, family care-givers like Ayşe are commended for fulfilling their traditional responsibility. However, it is still silenced and invisible.

England and Dyck (Reference England and Dyck2011: 208, 210) say the home, with its personalised spatial context in which care work is performed, is a private space and a key site of care, embedded with personal and symbolic meanings. The findings here reveal that the use of the space, the meaning of units in the home space and the degree of privacy versus professionalism all depend on the kinds of relationships surrounding the care work practice, the roles of the actors in care work, types of care work and the care needs of the older people. The home as a space of care can be treated as an intersection of the public and the private sphere, agreeing with England and Dyck (Reference England and Dyck2011). The paid, unpaid and professional carers all mention observing embarrassment and shame in those they care for when they are unclothed and in need of cleaning in their own private space, as in the case of Fatma. It seems, for paid care work, if ‘shame’ is felt or expressed by those they care for during tasks involving intimate body parts, the distinction between the public and private space could be said to exist. However, if the older person is bedridden, unconscious or unable to meet any needs independently, any distinctions regarding the notion of space are blurred. When the relationship becomes intimate, and mutual trust and ease are established, the distinction between the private and the public dissipates. For the paid carers interviewed, the use of the home as the space of care seems to blur the distinction between the private and public sphere. This ambiguity stems from the relationship of the care-giver to the older person and acclimation to them and their body, and how long the care-giver has been providing care for the same person.

The other important finding is that care work has strong emotional aspects for these paid and unpaid carers. Mutual trust, understanding, acclimation to each other, love, kindness, patience and intimacy are all-important for performing care and help both sides cope with fear and unease. According to Wolkowitz (Reference Wolkowitz2006), England and Dyck (Reference England and Dyck2011) and James (Reference James1992), the physical and emotional aspects of care work in the home space overlap. For the unpaid care-givers interviewed, the emotional component seems taken for granted; however, for the paid care-givers, managing the emotional aspects is more complex. All carers in the sample highlight the emotional component of later-life care as the essence of care work and understate the bodily aspects. In fact, the participants seemed to avoid mentioning bodily tasks until further along into our conversations, similar to Twigg's (Reference Twigg2004) finding that care workers de-emphasised the bodily character of care. While the unpaid carers stated it was unseemly to complain about bodily tasks because they were bound by traditional duty, the paid carers seemed to have developed coping strategies and to legitimise their choice to make a living touching a stranger's body. As mentioned before, Cohen and Wolkowitz's (Reference Cohen and Wolkowitz2018) study highlights the material nature of body work for paid carers since it involves physical touch and the manipulation of other bodies. Since unpaid care work also includes these aspects, as seen in Ayşe's case, our study finds that unpaid care work also has a material nature to it, no matter how silenced certain intimate aspects are, in both types of care, for different reasons.

Twigg (Reference Twigg2000b: 169–170) emphasises the similarities between paid care work and informal family-based care in terms of the gendered nature of both and the multifarious duties performed, both practical and emotional. She states paid care workers see their work as an extension of their family roles, that the ‘unbounded ethic’ or ‘love ethic’, which has its basis in family care, is imported into paid work. Similarly, the paid care-givers here like Meliha tend to construct an imaginary family, emphasising informalisation and the love/emotional aspects. The coping strategies the interviewed paid carers use for body work are used also by the unpaid carers, thus blurring the distinction between them.

In the case of paid care work, emotional attachment to the cared, a friendly relationship with the cared and their family members, acclimation to the person and their body, and (as emphasised by Rittersberger-Tılıç and Kalaycıoğlu, Reference Rittersberger-Tılıç, Kalaycıoğlu, Dedeoğlu and Elveren2012) establishing ‘imaginary kinship relations’ and ‘mutual trust’ leave them susceptible to low wages, flexible/unpredictable working hours and additional duties in the care space. These indicate the exploitative and exhausting character of care work. Unpaid women care-givers are also forced into performing care work, albeit by traditional norms and the government care work stipend, constituting exhausting labour circumstances.

As Cohen (Reference Cohen2011: 201) notes, ‘body labour does not involve a single set of practices, nor a single set of workers or bodies-worked-upon’, which complicates the standardisation of this type of labour. Also, there are many factors and actors influential in the practice and organisation of the body work practice and the relationship between the body worker and the body-worked-upon. However, the commonalities mentioned above justify referring to care work as body work. Though body work is frequently mentioned in the context of paid jobs in the literature, in this study, care work is conceptualised as a type of body work, whether paid or unpaid. An analytical distinction between waged labour and unpaid labour might be useful, but drawing a strict distinction is challenging because our findings imply that they overlap in domestic settings. While paid care work involves monetary compensation, the two types of care work are more similar than different, as the bodily/physical work performed on the ageing body, the relationships surrounding it and the related emotional aspects are enmeshed. As Twigg (Reference Twigg2000b) also mentions, paid carers import the aspects of family-based care into paid work. Whether the care is paid or unpaid in the sample, with the exception of the nurses, the similarities outnumber the differences because the space used is the home, a space normally reserved for primary intimate relationships, and the work involves the ‘touching’ and ‘modification’ of (intimate parts of) the older body for the sake of normalising it, which renders the older body the space of a power struggle. Furthermore, since aspects of care work can be perceived as demeaning, the carers develop coping strategies such as informalisation to legitimise their work. This informalisation usually involves the construction of imaginary familial bonds, which serves to blur the distinction between paid and unpaid carers. The emotional and physical aspects of care work as body work are so enmeshed that this study does not find sharp distinctions between paid and unpaid care work. The bodily aspects of the work, in particular, require the carers to manage their emotions and navigate the relationships surrounding the older person. The nature of body work, which includes intimacy, dirty work, negativities, and touching and modifying the aged body has led the interviewed care-givers to develop techniques for distancing themselves from the older body; managing, normalising and presenting the body; managing and reconciling the relationship; managing emotions; coping with traditional care norms, relating to the aged body as a space of power struggle; infantilising the cared; informalising the care (for the paid care-givers); medicalising bodily tasks (for the professional care-givers); and emphasising the asexuality of the aged body (for the paid care-givers).

Limitations

The study has some methodological limitations. Firstly, it may seem that the professional care-givers in the sample do not fully reflect the variety of professionals available since those in the study are young, less-experienced, newly graduated nurses caring for older patients to supplement their income. However, conversations and observations before the fieldwork showed that those in this line of work indeed mostly consist of new graduates. Secondly, foreign immigrant carers could not be included in the sample due to the language barrier, with the exception of only one immigrant who spoke Turkish. The fieldwork showed that paid later-life care provided by educated immigrants from poorer foreign countries has been an increasing trend in Turkey. Finally, family care-giver participants are uneducated, rural-to-urban migrants, and have low socio-economic status. Although people in this profile in Turkey prefer to (or indeed have to) care for their older relatives themselves, it is not true to say this participant group encompasses all types of care-givers that provide family care.

Concluding remarks and implications

Shilling (Reference Shilling2011: 336) states, ‘the issues raised within body work in health and social care is not only of academic concern, but deserve the attention of politicians and policy makers, front-line workers, and recipients of health, welfare and other body-related services’. Our findings not only point to the necessity for further research into other aspects and contexts of later-life care but also have implications for social policies.

Considering the population of people over the age of 60 is poised to double in 2050 (World Health Organization, 2018), in-depth studies on later-life care and body work-related practices in different cultures are crucial to aid our understanding of the needs of all those involved. This study was conducted on later-life carers in Turkey to identify similarities and differences in paid and unpaid care-givers’ experiences of body work using interview findings. Twigg and Wolkowitz define paid care work as body work, but this study conceptualises both paid and unpaid care work as such since both involve work carried out on the bodies of others. Our findings do support their conceptualisation of body work in general, but this work, in addition to revealing similarities between paid and unpaid body work, shows differences related to strategies used by these carers to deal with certain challenging aspects of body work. While it is found that the paid care-givers here construct an imagined familial relationship as a coping mechanism for what is seen as demeaning work, the work carried out by the family member carers inherently involves body work. It is our recommendation that future research comparatively examines care work as body work, both paid and unpaid, within the context of different local cultures, which could reveal different later-life care patterns, thus deepening and enriching the concept of body work.

One aspect of later-life care that was not the direct focus of this study, but which seems important for future research in terms of its policy implications, was found as the issue of class, based on the findings. All our participants come from low-income families. Furthermore, statistics show low-income families in Turkey tend to care for their older relatives at home (MFSP, 2011), possibly stemming from traditional obligations concerning family care and state support for family care, i.e. the care-giver allowance, as well as the inadequacy of social policies. In cases of paid care work, even for the nurses, differences were apparent between the cared and the carer in terms of social class. Therefore, further research into class-based differences in later-life care is necessary to inform related social policies.

In the Turkish context, while there are instances of institutional care, long-term paid care and short-term professional care, family care predominates; and families not taking care of their older relatives can be subjected to social exclusion. The Turkish state also promotes family care, as mentioned by Kalaycıoğlu (cited in Üstünel and Yılmaz, Reference Üstünel and Yılmaz2009), which falls upon female relatives. This reflects what James (Reference James1992: 490) describes: ‘family care emerges as being characteristically women's work, unpaid, but usually in addition to paid work, and based in the home where it becomes a 24 hour, “on-call” responsibility’. In case of care work, as Twigg (Reference Twigg2000b: 141) emphasises, ‘there is little or no public discourse on the body and its functioning’ and the coercive nature of care work workload, either paid or unpaid. Like in many cultures, in Turkey women are viewed as naturally predisposed to caring and performing bodily tasks for others, a perception echoed by many of our participants. Therefore, even paid carers are seen as doing women's work. However, when caring for older relatives as prescribed by tradition and social norms, women are confined to the care space, and prevented from gainful employment and having a reasonable social life and enjoyment of public spaces. These reinforce their subordinate position in society. This also means that the difficulties involved in care work are ignored at the social policy level. First, it needs to be acknowledged and understood that what is traditionally the responsibility of women, and what women do, for the most part, is later-life care work in the form of body work; it is coercive and labour-intensive; and it places severe limitations on women's lives. Secondly, paid care-givers must be registered with the social security and their working conditions must be regulated in accordance with labour law. Body work is challenging enough without the burden of difficult working conditions, further reinforcing the secondary position of women in the labour market.

Acknowledgements

Preliminary findings of the research were presented at the 2013 European Sociological Association Conference. I would like to thank all participants who kindly took time to share their information and insights. My deepest thanks go to Professor Sarah Nettleton for her invaluable advice, continuous support and guidance throughout the study.

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.