1 Introduction

In 2016 post-truth was named the word of the year by Oxford Dictionaries. Although it had been functioning in English for many years, appearing in numerous newspaper headlines and occasionally even in book titles, its usage skyrocketed immediately after the 2016 Brexit referendum in the UK and at the beginning of the 2016 American presidential campaign. The changing political landscape called for novel ways of linguistic representation and created the need for post-truth. Keyes affirms:

At one time we had truth and lies. Now we have truth, lies, and statements that may not be true but we consider too benign to call false. Euphemisms abound. We're ‘economical with the truth’, we ‘sweeten it’, or tell ‘the truth improved’. The term deceive gives way to spin. At worst we admit to ‘misspeaking’, or ‘exercising poor judgment’. Nor do we want to accuse others of lying. We say they're in denial. A liar is ‘ethically challenged’, someone for whom ‘the truth is temporarily unavailable’. (Keyes Reference Keyes2004: introduction)

Society's preference for the use of euphemisms correlates with the increased reliance on emotions instead of facts in discussing current affairs and various political issues. Modern-day politicians play on people's emotions, such as anger and fear, in order to score political points. Nowadays truthfulness in not in demand and lies are not stigmatised. We are facing the ‘routinization of dishonesty’ (Keyes Reference Keyes2004; Crossley & Sitbon Reference Crossley and Sitbon2016). Culture in general, and political culture in particular, is changing dramatically, and together with the changing reality it shapes the language that describes it. Instead of the truth, we are more likely to encounter post-truth and its kin, enumerated by Keyes (Reference Keyes2004): enhanced truth, neo-truth, soft truth, faux truth, truth lite, poetic truth, parallel truth, nuanced truth, imaginative truth, virtual truth, alternative reality, strategic misrepresentations, creative enhancement, non-full disclosure, selective disclosure, augmented reality, nearly true, almost true, counterfactual statements and fact-based information. Lying has been substituted by: enriching, enhancing, embroidering, massaging, tampering with, bending, softening, shading, shaving, stretching, straying from the truth or even making things clearer than the truth, presenting the truth in a favourable perspective, telling the truth improved and being lenient with honesty. What is more, post-truth has motivated the appearance of a number of related items in English (post-fact, post-trust, post-logic, post-sense) as well as in other languages, such as German (postfaktisch), Spanish (posverdad, posfactual), Polish (postprawda, postfakt, postprawo). This proliferation of items based on the post-truth model calls for a closer inspection. This article claims that the increasing frequency of occurrence of post-truth in 2016–17 as well as similar words prefixed with post- has lead to the emergence of the new meanings associated with the prefix itself.Footnote 1 These meanings, difficult to define in an unambiguous way as they are, clearly revolve around ‘fake’, ‘mock’ or ‘approximate’, as is presented in the analytical part of the present article. A radial network categorisation model is proposed in order to account for the novel meanings of the prefix (Brugman & Lakoff Reference Brugman, Lakoff, Small, Cottrell and Tanenhaus1988; Geeraerts Reference Geeraerts2009; Lewandowska-Tomaszczyk Reference Lewandowska-Tomaszczyk, Geeraerts and Cuyckens2012).

There are several mechanisms at play at the same time. First of all, the new sociocultural reality and especially the changing face of contemporary politics lead to the need for new concepts to be constructed. Relying on unverified information, ‘truthiness’Footnote 2 rather than truth, and appearances rather than evidence need to be given a new name. Secondly, taboo words are to be avoided, and instead of lying we are more willing to accuse others of using post-truth. As a consequence, this term starts to be associated with certain attitudes which give rise to ironic and sarcastic undertones. They become conventionalised in the prefix and may then be transplanted into new creations based on the same schema. Finally, the word post-truth is innovative and expressive enough to grab attention and thus is likely to occur in newspapers and newspaper headlines, which in turn leads to its further popularisation.

2 Productivity of affixes

There exists a great deal of confusion and uncertainty in the study of linguistic productivity, and even its definition varies significantly from scholar to scholar. Hockett (Reference Hockett1960) introduces the term for one of the properties of human language, thus differentiating it from other animal communication systems. He calls it the most important property and defines it as a ‘the capacity to say things that have never been said or heard before and yet to be understood by other speakers of the language’ (Reference Hockett1960). Language is open and productive ‘in the sense that one can coin new utterances by putting together pieces familiar from old utterances, assembling them by patterns of arrangement also familiar in old utterances’ (Hockett Reference Hockett1960: 90). This definition makes Hockett's ‘productivity’ very close to Chomsky's ‘creativity’, as Bauer observes (Reference Bauer2001). To obscure the picture even more, some scholars assume that productivity is a scalar concept (Bauer Reference Bauer2001). So is the prefix post- productive at all? Certain morphological processes, such as prefixation, can be used to create new words, or can be available whereas others are not. Bauer states:

Those that are available may be used in the creation of neologisms, they are found (relatively) frequently in nonce-formations, they are is some sense psychologically salient, since the processes can be done and undone (in the sense of comprehended) on-line in real time, and this leads to a relatively high number of types being found in corpora, with a relatively low number of tokens for each type. (Bauer Reference Bauer2003: 7)

Plag (Reference Plag2003) defines productivity of an affix as ‘the property of an affix to be used to coin new complex words’ (Plag Reference Plag2003: 55) and claims that some affixes possess this property, some exhibit it only to a certain extent, whereas others do not have it at all. Lehrer (Reference Lehrer1995), in turn, claims that she takes ‘the presence of neologisms to be evidence for the contemporary productivity of an affix’ (Lehrer Reference Lehrer1995: 135). At the same time, the presence of neologisms is linked to the ability an affix offers the language user to produce new words. New linguistic elements can be created by analogy with a most prominent element which functions as a sui generis schema. New elements are created on the basis of such a schema, by analogy with the most prominent element. The present article uses the definition of a constructional schema in line with Ronald Langacker:

In CG [cognitive grammar], patterns of composition are described by constructional schemas, i.e., schematic symbolic assemblies representing whatever commonality is observable across a set of symbolically complex expressions. Constructional schemas serve as templates for the construction and evaluation of novel expressions. They are precisely analogous to the expressions that instantiate them, except that some or all of the symbolic structures constituting the assembly are schematic rather than specific. (Langacker Reference Langacker2003: 257–8)

Taylor (Reference Taylor2002) also emphasises the underlying schemas and defines productivity in the following way:

Productivity is the flipside of analysability. A word is analysable to the extent that it can be brought under a schema; the more salient a schema, the more likely it is to be able to sanction new instances, created on the pattern of the schema. The fact that speakers are able to create new forms depends on their having recourse to schemas which sanction the new forms; the schemas, in turn, arise in virtue of the analysability of encountered instances. (Taylor Reference Taylor2002: 290)

The salience of the schema is responsible for the number of instances it sanctions. The more instances can be subsumed under the schema, the more productive the schema appears to be. However, it is not the general frequency of tokens that counts, but rather the number of different types. ‘All other things being equal, a schema which has a large number of different instances, none of which is itself particularly frequent, will be able to sanction new instances more readily than a schema with relatively few instances, each of which in itself may be quite frequent’ (Taylor Reference Taylor2002: 291). Another factor influencing the productivity of a word-formation pattern is the valence of a morpheme. Morphemes may be restricted in their use and attach, for example, to stems with certain semantic content or specific phonological structure.

Clearly, then, the prefix post- can be considered productive. It is available for speakers to use, and newly coined creations are easily subsumed under the general post + X schema. The salient analysability leads, in turn, to increased productivity. Neologisms abound, meanings change, and it is to the problem of this semantic change that we will now turn.

Hamawand (Reference Hamawand2013), after Langacker (Reference Langacker1987, Reference Langacker1991, Reference Langacker2008), claims that derivation is a combination of a stem and an affix which either modifies the conceptual content or yields different construal of a situation in near-synonymous constructions.

The meaning of a derivative involves the particular construal the speaker imposes on its conceptual content. Two derivatives may invoke the same conceptual content, yet they differ semantically by virtue of the construals they represent. Derivation is then seen as the integration of the component parts to form a composite whole. It is not only a question of the form or semantics of the base, but also the result of the semantic match-up between its internal parts. Morphology is semantically motivated, and differences in morphological behaviour reflect differences in meaning. (Hamawand Reference Hamawand2013: 737)

This view is in line not only with Langacker's cognitive grammar, but also with cognitive semantics in general as well as with the usage-based approach to language study. Newly coined derivatives are thus created by language users in order to serve a given communicative function; to convey the necessary meaning. Other users’ knowledge, in turn, originates from the actual language use, i.e. from the situations in which a given element is encountered. In this way, new meanings are gradually conventionalised and accepted. In general, a linguistic system is gradually shaped by actual language use. The next part of the article, then, will examine how the actual data of using novel derivatives shapes the system.

3 The prefix post- as a radial category

Radial categorisation differs from the classical approach (Taylor Reference Taylor2003) in that the category members are not evaluated according to a set of binary, necessary and sufficient attributes, but rather according to their similarity to the central meaning, the prototype. The prototype usually has an embodied, physical meaning and thus prototypical meanings are most commonly related to the spatial domain. But whatever the nature of the prototype, other members are ascribed to the category on the basis of the perceived similarity to the prototype. This rule sanctions the addition of new members, which, no matter how much they vary, bear some resemblance to the already existing, more entrenched and prototypical members, i.e. meanings in the case of the prefix post-.

In a radial category, all subcategories are motivated directly or indirectly by the prototype, but there need not be any one characteristic that all of them share. The prototype is a semantically central sub-category that serves to motivate extensions to other subcategories via cognitive mechanisms such as metaphor and metonymy. Furthermore, the prototype tends to belong to the physical domain and is normally connected to more subcategories than any other. It is important to notice that the subcategories within a network are not necessarily discrete, nor must any given example fit into one and only one subcategory. Instead, the subcategories serve as salient nodes in a web of interrelated meanings where any given item may be motivated by multiple subcategories. (Nesset, Janda & Endresen Reference Nesset, Janda and Endresen2011: 380)

Nesset, Janda & Endresen (Reference Nesset, Janda and Endresen2011) make use of radial categorisation in order to account for the proliferation of meanings of prefixes, in which they echo a well-known paper by Brugman (Brugman & Lakoff Reference Brugman, Lakoff, Small, Cottrell and Tanenhaus1988) in which she analyses the meanings of the preposition over. Both prepositions and affixes are highly polysemous and their meanings are distributed throughout multiple semantic domains, which makes their classification complex and difficult. Radial categorisation proves most useful in accounting for such complex categories. Newly added members can also be accommodated into a radial category without risking methodological confusion. Geeraerts claims that ‘the radial network model describes a category structure in which a central case of the category radiates towards novel instances: less central category uses are extended from the center’ (Geeraerts Reference Geeraerts2008: 9). Lewandowska-Tomaszczyk (Reference Lewandowska-Tomaszczyk, Geeraerts and Cuyckens2012) describes the nature of radial categories in the following way:

Polysemous words are clustered around a number of (radially-related) categories rather than in one prototype category even though each of the polysemous senses can display a (complex) prototype structure. The central radial category member is a complex of a number of cognitive models, which motivate other non-central senses. The extended senses clustered around this one radial category are related by a variety of possible links such as image schema transformations, metaphor, metonymy or by partial vis-à-vis holistic profiling of distinct segments of the whole sense. (Lewandowska-Tomaszczyk Reference Lewandowska-Tomaszczyk, Geeraerts and Cuyckens2012: 22)

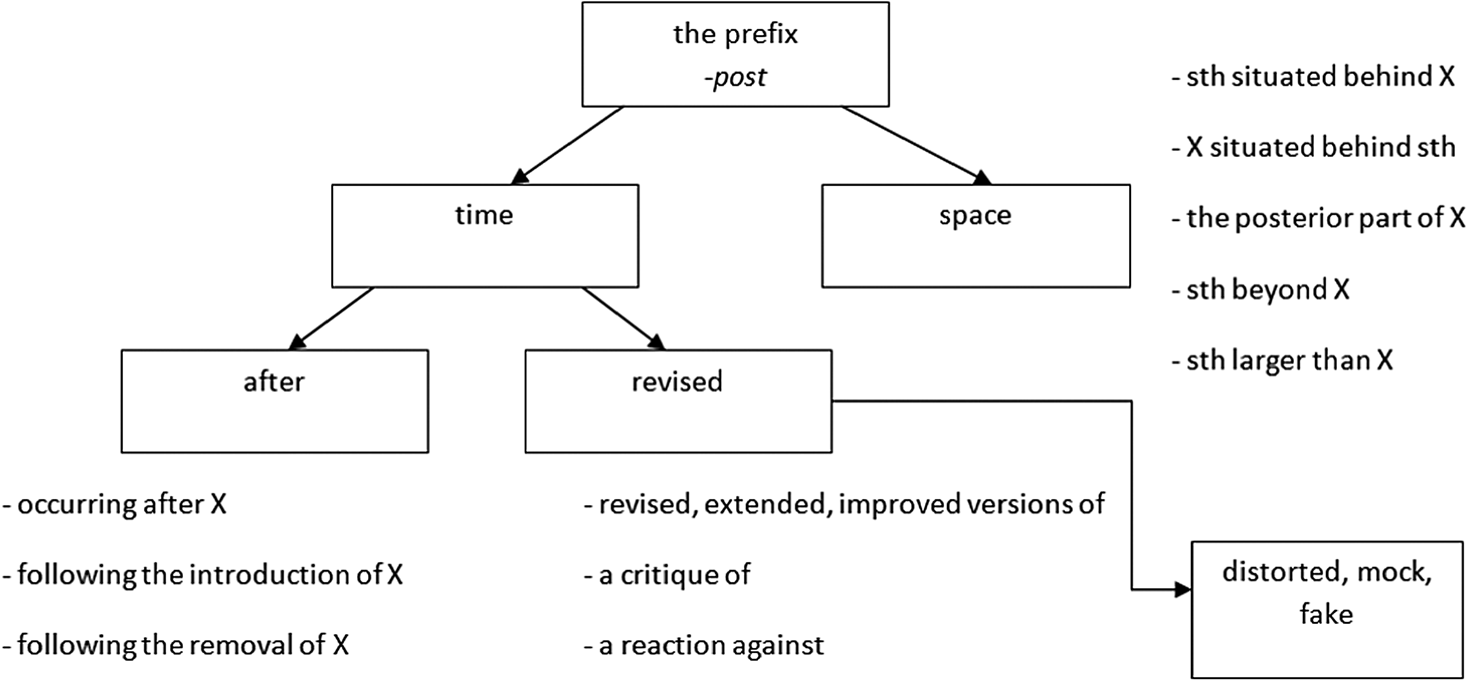

Radial networks are more concerned with ‘clusters of different senses rather than the structure of a single meaning’ (Geeraerts Reference Geeraerts2009: 192). They are similar to the family resemblance theory of categorisation in that their members are linked together by networks of interrelated senses, but do not necessarily share even one common feature (Taylor Reference Taylor2003). This can clearly be seen when comparing different senses of the prefix. The temporal sense may originate from the embodied, spatial sense and can be treated as its metaphorical extension. The ‘revised version’ sense, in turn, may be an elaboration from the temporal sense, whereas the new, emerging meaning found in combinations such as post-truth and post-fact may be derived from the ‘revised version’ meaning, but which at the same time is fairly remote from the spatial sense. Thus, different meanings are linked together in an AB > BC > CD > DE fashion, where neighbouring elements share certain features and more distant elements lack a common denominator. The radial network model is even more suited to the description of this category, however, because it focuses on the clusters of senses. In other words, the model proposed here emphasises a number of salient clusters to which other new members may attach as long as they share certain features at least with one member of the cluster. It has to be borne in mind, however, that categorisation by radial networks also has certain disadvantages, as pointed out by Geeraerts (Reference Geeraerts2009):

The complex and subtle interrelations that are revealed when we look at the features involved are not made explicit, and the whole radial network picture evokes a rather atomistic view of the meanings in a polysemous cluster. The radial network representation suggests that the dynamism of a polysemous category primarily takes the form of individual extensions from one sense to another. This may hide from our view the possibility that the dimensions that shape the polysemous cluster may connect different senses at the same time. (Geeraerts Reference Geeraerts2009: 195)

For this reason, the radial approach to categorisation is followed in order to convincingly account for the interrelated traditional meanings of the prefix post-, as well as the newly emergent meanings. Let us now examine the prefix in more detail.

Etymologically, the prefix post- is a word-forming element meaning ‘after’, from the Latin post ‘behind, after, afterward’, from *pos-ti (source also of Arcadian pos, Doric poti ‘toward, to, near, close by’; Old Church Slavonic po ‘behind, after,’ pozdu ‘late’; Lithuanian pas ‘at, by’).

It can be characterised in the following ways: (i) as a spatial prefix meaning ‘behind’, as in postabdominal; (ii) as a temporal prefix meaning ‘after’, e.g. in postadolescence. The temporal meaning is extended into (iii) ‘revised version of a theory’, e.g. in poststructuralism.

Most frequently, nouns and adjectives are prefixed with post-, although there are occasional combinations with verbs.

• prefix + noun (e.g. postabdomen, postadolescence, postadolescent, postadoption, postapocalypse)

• prefix + adjective (e.g. postabdominal, postbasic, postcapitalist, postmodernist)

• prefix + adverb (e.g. postabdominally, postcritically)

• prefix + verb (e.g. postdate, postfix, postjudge)

Lehrer (Reference Lehrer1995) and Hamawand (Reference Hamawand2013) agree that although the prefix has both spatial and temporal uses, it is more productive as a prefix of time. Within the temporal sense, Hamawand also distinguishes a sense related to a ‘revised view of a theory’ and represents a network of related meanings, as shown in figure 1 (Hamawand Reference Hamawand2013: 741, modified).

Figure 1. A network of the interrelated senses of the prefix post-

Counterintuitive as it may seem to cognitive linguists, the prefix's temporal meaning is considered as the prototypical one. Prototypicality is understood here, however, not as the primary meaning out of which other meanings have developed, but rather as the one which is the most frequently encountered. Consider:

Primarily, the prefix post- is tasked with designating order in time. This sense can be restated in two ways. (a) ‘after the period named in the root’. This sense applies when the nominal bases are abstract, implying action. For example, post-war reconstruction is reconstruction that happens in the period after a war. Other nouns are post-ceremony, postelection, post-operation, post-race, post-sixth-century, etc. The same is true of adjectival bases, as in post-doctoral research, post-industrial society, post-natal care, post-operative complications, etc. (b) ‘a revised view of the theory named in the root’. This sense applies when the nominal bases are abstract, implying non-action. For example, poststructuralism is a philosophy that rejects structuralism's claims to objectivity and emphasises the plurality of meaning. Other nouns are postfeminism, postmodernism, etc. (Hamawand Reference Hamawand2013: 741)

In other words, the meanings cluster together and form a radial category. Taking all the above into consideration, it seems that the radial approach to categorisation is the most relevant approach to be applied for the analysis of the emergence of new meanings of the prefix post-. For the purposes of this article, only truly polysemous cases are taken into consideration and a whole group of linguistic elements stemming from the meaning of post- used in the postal context (the context of post office) are disregarded, such as: postbag, postcard, postcart, postcode, postman, postmark, postwoman, as well numerous acephalous cases, for instance: poster, postiche, posture, postpone, postulate. Having now set the context, a detailed analysis of the prefix post- is offered in the next section.

3.1 Spatial meaning

What Hamawand (Reference Hamawand2013) labels as the spatial meaning is in fact a category of its own. It consists of a number of interrelated sub-meanings all of which pertain to the spatial domain, but form different image schemas. Thus, the post + X construction may be used to describe the following situations:

(i) something is situated behind X > postocular (also: postorbital) – situated behind the eyes (e.g. postocular pain), postoral – situated behind the mouth, postpalatine – situated behind the palate, postscenium – the part of the theatre situated behind the scenes, postcanine – situated behind the canine teeth (figure 2)

(ii) X situated behind something > postscapula – the part of the scapula situated behind or below the spine (figure 3)

(iii) the posterior part of X > postoblongata – the posterior part of the medulla oblongata, postsphenoid – the posterior part of the sphenoid bone (figure 4)

(iv) something beyond X > posthuman – a person who possesses qualities beyond human qualities, exists in a state beyond being human (figure 5)

(v) something larger than X > post-Panamax – larger than Panamax – (related to ships), i.e. exceeding maximum dimensions listed in the regulations on Panama Canal transit (figure 6)

Figure 2. Something is situated behind X

Figure 3. X situated behind something

Figure 4. The posterior part of X

Figure 5. Something beyond X

Figure 6. Something larger than X

Note that for the processing of the meanings listed in (i), (ii) and (iii) the point of reference is needed, i.e. such constructions inevitably possess a degree of subjectivity as it is the conceptualiser who can access the meaning from a certain vantage point which is not expressed directly. In (i) the choice of the perspective is clear: we tend to perceive most objects, places, and body parts as having fronts and backs and analyse the expressions accordingly. For instance, postocular is located within our body, as the front of the eye is where the retina and the pupil are located. However, the choice of the reference point in (ii) is not necessarily clear. It may be the centre of our body, the centre of gravity, or some central, pivotal element like the spine in the human body. In (iii) there is no need for any external point of reference, the object, however, needs to be conceptualised in a certain way, i.e. we need to decide on its front and back. Note also that meaning in (i) can be considered prototypical, creating the concept of prototypes within prototypes, or in other words: meta-prototypical categories.

3.2 Temporal meaning

Similarly to spatial meaning, temporal meaning also exhibits a clustered nature with a number of sub-meanings creating their own prototypical organisation. Thus, the post + X construction can mean the following:

(i) something occurring after X, something following X > postsale – after a sale, postwar – after a war, postembryonic – a period that follows the embryonic stage of development

(ii) something following the introduction of X > postwelfare – following the introduction of the welfare system, postapp – following the introduction of an app

(iii) something following the removal, disappearance, or subtraction of X > postobese – no longer obese, posttumour – following the removal of a tumour, posttax – following the subtraction of the tax

The meaning in (i) can be considered the prototypical temporal meaning of the prefix, whereas other meanings form extensions to it. In addition to the prototypical organisation of the categories, we also observe fuzzy boundaries between them. Consider, e.g., postverbal meaning ‘occurring after a verb’, ‘located after a verb’. This element can be ascribed to both the spatial and the temporal category; its spatial meaning is the one of being located after a verb in a written sequence of words, its temporal one pertaining to its occurrence after a verb in speech.

3.3 Extended temporal meaning (‘the revised version’ meaning)

It is more difficult to enumerate sub-meanings of this extended category, as its members are more abstract and require more detailed definitions. Let us investigate the following examples:

• postfeminism – a set of theories which claim that feminism is no longer relevant and needs to be extended to fit women's needs and expectations

• postimpressionism – emerged as a reaction against Impressionists’ way of depicting light and colour

• postmodernism – a reaction against tendencies in modernism

• poststructuralism – presents a critique of structuralism

This meaning can be roughly encapsulated in the following way: post X is a revised, extended, improved version of X or a reaction against, a critique of X. This leads us to the extended radial network of the prefix (figure 7).

Figure 7. An extended network of the interrelated senses of the prefix post-

How does post-truth fit into this picture? Considering multiple paraphrases that were enumerated in the introduction, we may observe that they all deal with the ‘improved’ or somehow extended and more capacious versions of the truth. As a consequence, that post-truth-like expressions can be claimed to constitute a subsection of the ‘revised version’ group of meanings (rather than ‘temporal’ meanings indicating, for example, the advent of a new era). These new meanings come into being and can be partially accounted for as a result of conceptual integration.

4 Emergent meanings of the prefix post-

Whatever the actual motivation driving this semantic change, the underlying process is based on conceptual integration. Conceptual integration, as proposed by Fauconnier and Turner (Fauconnier & Turner Reference Fauconnier and Turner2003a, Reference Fauconnier and Turnerb), is represented as a four-domain model in which two input spaces are integrated onto the common ground (generic space) in order to create a new quality (blended space). The blended space is a new entity whose meaning is different from the sum of meanings included in the individual mental spaces. There are emergent elements which can only be accounted for in a cognitive way, i.e. the new value appears as a result of the cognitive mechanism of integrating two concepts while also taking into account the contextual information. Context, in turn, is understood in a very broad way, similarly to Langacker's current discourse space (Langacker Reference Langacker2008), which includes the whole conversational frame: the speaker and the hearer, the interaction between them, their background knowledge, and the situation in which this exchange takes place. Only in this way can meanings be ‘negotiated’ and adopt new qualities which are absent from either of the original input spaces. Thus, in the case of post-truth, the generic space is constituted by the constructional schema post + X, on the basis of which numerous elements may be created. Input space 1 is the prefix, input space 2 is the stem. In the blended space new meanings arise. Another factor contributing to the appearance of emotive overtones is the semantic clash between the input spaces, i.e. the juxtaposition of the prefix post- and the stem truth. At first sight, neither of the two most conventionalised (spatial and temporal) meanings of the prefix makes sense in this juxtaposition. The extended meaning, that of ‘revised version’, also feels counterintuitive, as truth is supposed to be a non-graded, absolute and stable philosophical concept.

Let us take a closer look at post-truth in context. The examples shown below were extracted from the specified online sources between January 2018 and January 2019, unless explicitly stated otherwise.

5 Example analysis

5.1 Investigating the uses of post-truth

It is worth bearing in mind that the view of the polysemy of the prefix post- proposed in the present article is not based on the classification by a prototype with one strong meaning and other meanings ascribed to the category by means of the similarity to the prototype, but on a classification based on the conception of a network of interrelated senses with several strong semantic nodes.

For this reason, it is important to stress the undeniable connections existing between all the senses of a given category. The use of one element inevitably leads to the activation, or priming, of other senses, which become more salient and may add some semantic colouring to the element used. Regardless of its most common definition, post-truth activates associations related to the temporal meaning of the prefix and thus suggests the end of the truth: post-truth era hints at the times when the truth is no longer used; post-truth politics refers to the new fashion of making politics which is inferior to the old times when the truth was still relevant, etc. It is arguable, though, whether a similar association can be established between post-truth and the spatial sense of the prefix. There are numerous contexts in which collocations of spatial relations occur. Consider the following set of examples:

(1) Last days we felt an implicit longing for icebergs, but maybe we just live in a post-truth region. (https://woodcastles.de/en/artwork/greenland-ice)

(2) The spokesperson for Trump that said he didn't have to tell the truth because we live in a post-truth country is also pretty scary. (www.heraldnet.com/opinion/idea-of-a-post-truth-country-is-scary/)

(3) It once again brings to the focus the say-do gap that is arguably fuelled by the same inability to rationalise that has led us to our post-truth state. (www.truth.ms/blog/post-truth-important-considerations-for-insight-consultants)

(4) This post-truth state considers truth of ‘secondary importance,’ the emotional fantasy of what is wished for takes precedence over what's so. (www.chirotexas.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=3041:the-post-truth-age&catid=23:news-information&Itemid=178)

(5) As we move into this strange dystopian post-truth area where people believe reality will conform to whatever the loudest people want it to be, StarTalk is a wonderful dose of anti-venom to have on hand. (www.christhebrain.com/mindmaelstrom/heres-5-things-keeping-me-sane-as-we-journey-into-2017)

(6) The ‘post-truth’ environment we live in seems, at least in part, to be a function of the current confusing information flow and how politicians, governments and others use it towards their own ends. (http://time.com/4650956/photojournalism-post-truth/)

Post-truth collocates very well with region, country, state, area and even environment, although the last case does not give context unequivocal enough to analyse the actual meaning of the expression. Clearly, the examples enumerated above do not constitute indisputable evidence for the interrelation between the different senses of the polysemous prefix, and they are not meant to. What they do show, however, is a strong tendency for senses present in a polysemous element to merge and influence each other (i.e. the new senses present in post-truth intertwining with the more general ‘spatial meaning’), rather than forming isolated islands of meanings. The examples in (7) to (12) constitute further evidence for the links to the ‘temporal meaning’ of the prefix.

(7) So, what role is photography to play in this ‘post-truth’ era, when even documentary evidence is denied or disputed by those in power, where access is controlled, where we suffer from an information overload and the battle for the information space is chaotic and fought on a thousand fronts? (http://time.com/4650956/photojournalism-post-truth/)

(8) ‘… Yet we now confront what has been called a “post-truth” era, one in which evidence, critical thinking, and analysis are pushed aside in favor of emotion and intuition as bases for action and judgment,’ Faust told an overflow crowd at Sanders Theatre. (https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2017/02/pursuing-veritas-in-a-post-truth-era/)

(9) We may live in a post-truth era, but nature does not. (www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-oe-barnett-nature-alternative-facts-20170210-story.html)

(10) Homo sapiens is a post-truth species, whose power depends on creating and believing fictions. (www.theguardian.com/culture/2018/aug/05/yuval-noah-harari-extract-fake-news-sapiens-homo-deus)

(11) Postmodernism in post-truth times (Kester Reference Kester2018)

(12) The truth about the post-truth age (www.ft.com/content/53b00158-409c-11e7-82b6-896b95f30f58)

However, post-truth is most frequently encountered in social and political contexts, as illustrated by the following sentences:

(13) Scientists and philosophers should be shocked by the idea of post-truth, and they should speak up when scientific findings are ignored by those in power or treated as mere matters of faith. (www.scientificamerican.com/article/post-truth-a-guide-for-the-perplexed/)

(14) Post-truth refers to blatant lies being routine across society, and it means that politicians can lie without condemnation. (www.scientificamerican.com/article/post-truth-a-guide-for-the-perplexed/)

(15) The irony is that politicians who benefit from post-truth tendencies rely on truth, too, but not because they adhere to it. They depend on most people's good-natured tendency to trust that others are telling the truth, at least the vast majority of the time. (https://thewire.in/media/post-truth-take-ram-setu)

(16) One offshoot of the Brexit aftermath that is particularly disturbing is a growing obsession with the ‘post-truth’ society. (https://senseaboutscience.org/activities/the-post-truth-debate/)

(17) It has now spiralled into a debate about how to better appeal to ‘post-truth’ citizens, as though they are baffling and lack reason. (www.theguardian.com/science/blog/2016/sep/19/the-idea-post-truth-society-elitist-obnoxious)

(18) No doubt some election 2020 Svengali is right now writing the plans for how to win over a post-truth electorate – more statements on buses. (www.theguardian.com/science/blog/2016/sep/19/the-idea-post-truth-society-elitist-obnoxious)

In all of these examples, however different they are, the meaning of the prefix in not neutral. It activates negative, sarcastic and mocking attitudes. At the same time, this raises the question whether these newly acquired semantic and pragmatic values migrate to other linguistic items together with the prefix or whether they are inherently present only in post-truth itself. In order to shed more light on this issue, let us consider other creations based on the same schema.

5.2 Investigating the uses of post-fact

This section presents a selection of examples of post-fact which are often used interchangeably with post-truth and treated as synonymsFootnote 3 of it.

(19) Perhaps, though, the biggest sign of the arrival of a post-factual world is the level of lies, half-truths and pure fabrications launched by the Trump campaign in the 2016 US Election; all of which fueled him to become the new President Elect. (www.kadence.com/journal/2016/11/15/what-does-a-post-factual-world-mean-for-research)

(20) The US presidential campaign and the Brexit referendum result both fuelled concerns about the rise of ‘post-truth politics’, with many painting 2016 as the dawn of a post-factual era (http://archive.battleofideas.org.uk/2016/session/11540#.XCZbElVKjIU)

(21) In a post-factual presidency, Trump can play both victor and victim. (www.theguardian.com/media/2017/jan/15/trump-post-factual-presidency-both-victor-and-victim)

(22) Candidates, pundits and the public alike are guilty of this post-factual trance that seems to keep them from admitting they're wrong. (www.scottmonty.com/2016/11/living-in-post-factual-world.html)

(23) Myth versus fact: are we living in a post-factual democracy? (www.referendumanalysis.eu/eu-referendum-analysis-2016/section-2-politics/myth-versus-fact-are-we-living-in-a-post-factual-democracy/)

(24) Rather than presenting cold facts, we have to connect back to the client and the personal opinions they hold rather than propounding stark alternatives; which in a post-factual world can be happily glossed over. (www.kadence.com/journal/2016/11/15/what-does-a-post-factual-world-mean-for-research)

Again, the main semantic domain in which post-fact is used is that of politics in general and political campaigning in particular. Also, similarly to post-truth, post-fact seems to carry ironic and sarcastic connotations as well as negative emotive values. A world of post-facts, just like a world of post-truths, is a world in which no source of information can be trusted, deliberate misinformation is common and widespread. Post-facts are used in order to score political points by addressing people's emotions rather than reason. The use of post-facts and post-truths is said to have led to at least two groundbreaking political events: the victory of Brexit supporters in the referendum on exiting the European Union in 2016, and the election of Donald Trump as the forty-fifth President of the US in 2016. Many claim that the Leave side won because they played on people's emotions (e.g. their fear of immigrants, and the inflated sense of national pride) by manipulating facts and figures and presenting them as post-facts (or factoids) (see Bennett Reference Bennett2019a, Reference Bennett, Zienkowski and Breeze2019b). Likewise, in the US, opponents of Donald Trump accused him of deliberately misinforming the public in order to gain votes.Footnote 4

5.3 Investigating the uses of post-trust

Although post-truth and post-fact are by far the most frequent elements which adopt the prefix post- in its novel meaning, there are other, less common elements, such as post-trust. Post-trust refers to a (political) environment in which trust is no longer a value in itself, and building trust is used only, if at all, in order to score political points. Post-trust times are the times in which trust is scarce, hesitant and not taken for granted. This comes as a direct result of the proliferation of post-truths and post-facts or, even more importantly, the proliferation of phenomena being discursively constructed as such, especially in the political sphere. The general public have come to distrust the authorities and public figures due to the continuous decay of truth and a barrage of various kinds of affairs and scandals. The default attitude in the post-trust era is not to trust anyone and to remain sceptical about every possible source of information. Consider the following:

(25) Facts have always been hard to separate from falsehoods, and political partisans have always made it harder. It's better to call this a post-trust era. (www.wxxinews.org/post/finders-guide-facts)

(26) As alarming as the descent into a post-truth era is, we should be just as concerned by the current trust deficit and our slide into a post-trust world. (www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/02/in-a-post-trust-world-we-cant-allow-the-most-vulnerable-to-suffer/)

(27) In a ‘post-trust’ world, we can't allow the most vulnerable to suffer (www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/02/in-a-post-trust-world-we-cant-allow-the-most-vulnerable-to-suffer/)

(28) But in the post-trust era, we know that any news source can steer you wrong at times, and they're likely all jumbled together in your news feed anyway. (www.under-main.com/topical/post-truth-or-post-trust-2/)

5.4 Investigating other uses of the prefix post-

Other configurations with the prefix post- in its novel, emerging meaning include post-shame, post-logic, post-sense and post-politics (see figure 8). Post-shame is correlated with the constant use of post-truths and post-facts. If a person is continually surrounded by or constantly uses factoids and lies, they are likely not only to develop a lower sensitivity to them, but also to lose the sense of shame in using them. If everybody is telling half-truths or blatant lies, it is no longer perceived as shocking or shameful. A post-shame era is an era in which everybody lies, but no one pays much attention to it. Everybody, including public figures, uses emotions instead of facts and we can speak of an ‘affective’ way of doing politics (Papacharissi Reference Papacharissi2014; KhosraviNik Reference KhosraviNik2018). There is no feeling of shame involved in being caught lying. In such a world, the concept of sense is also distorted. If lying is a default scenario, there is no reliable point of reference, nothing and no one can be trusted and nothing makes sense, which eventually leads to a post-sense world. A post-sense world, in turn, is a world to which the laws of logic no longer apply. And we can sense our ‘gradual slide towards the post-logic age’, as cited in example (32). All these phenomena are present in a new style of politics: post-politics. Consider the use of post-shame, post-logic and post-sense in context in the following examples:

(29) A post-shame environment would imply a post-trustworthy environment, which would in turn lead to a post-trust environment (Blackburn Reference Blackburn2018: 8)

(30) Post-truth, post-logic and post-shame: the yapping halfwits of The Apprentice are perfect icons of our age. (www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/10/06/post-truth-post-logic-and-post-shame-the-yapping-halfwits-of-the/)

(31) Post-truth, post-sense and post-shame: perhaps Donald's TV children are not so dim after all. (www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/10/06/post-truth-post-logic-and-post-shame-the-yapping-halfwits-of-the/)

(32) You were sensing our gradual slide towards the post-logic age. An age where rational thought and imperial evidence are no longer to be used as barometers for ‘the truth’. In this post-logical world we will rely solely on emotional decisions and action without forethought. (https://medium.com/@eamonlavery/stop-trying-to-apply-logic-to-donald-trump-5b729bd77db3)

(33) We're not post-truth here. It's more profound than that: We're post-logic. We disagree on the very systems on which we arrive at belief. It's no coincidence that conservative ‘don't believe’ humans are causing climate change, for instance. And the fact that about 95 percent of scientists tell us that this is the case only fuels the believers’ contempt and strengthens their opposition. (www.pastemagazine.com/articles/2016/11/facebook-has-a-moral-obligation-to-fight-fake-news.html)

(34) It's a nihilistic post-shame world. It was bad enough when we bullied people for being stupid – but swinging back towards not even acknowledging what constitutes stupid might be even worse. (https://observer.com/2016/12/we-are-living-in-a-post-shame-world-and-thats-not-a-good-thing/)

(35) Regimes of Posttruth, Postpolitics, and Attention Economies (Harsin Reference Harsin2015)

Figure 8. Novel emerging meanings of the prefix post-

6 Prospects for further research

The prefix post- has been shown to be productive in English as well as in other languages. Due to its specific behaviour and novel collocations restricted to a number of contexts, it has extended its semantic scope and acquired a derogatory meaning which can be approximated as the meaning of mockery, criticism, referring to something fake and artificial. However, it seems that these new creations further increase the potential of the prefix. Let us consider example (36):

(36) There is no core identity, no mainstream in Canada. Those qualities are what makes us the first post-national state.

This statement made by the Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in 2015 opens up yet another perspective. Here, the intended meaning is clearly positive, inclusive, lifting limitations and problems that ‘national states’ may traditionally pose. However, the word has since appeared in numerous collocations and contexts assuming the original, intended meaning just as frequently as the opposite, negative, derisory one. Most common collocations include: post-national integration, post-national citizenship, post-national world, post-national democracy, post-national values, post-national country, post-national state, post-national Canada. Post-national is defined as ‘of or relating to a time or society in which national identity has become less important’ (Oxford Living Dictionaries online) or as ‘pertaining to a time or mindset in which the identity of a nation is no longer important’ (Wiktionary online), but its exact connotation is less clear, as it heavily depends on the speaker's point of view in general, and political persuasion in particular.Footnote 5 As example (36) shows, a contextual analysis is indispensible for establishing a more reliable and comprehensive network of meanings.

Moreover, a comparative study might reveal some new directions in the evolution of the prefix. It would be instructive to analyse whether only the complex post-derivatives are borrowed by other languages (e.g. post-truth > Polish post-prawda, post-fact > Polish post-fakt) or whether it is possible that completely new items can be created just on the basis of the schema, i.e. without any direct English model (e.g. possibly Polish postpolityka with a different meaning to the historical meaning of the English post-politics, or Polish postprawo, lit. ‘post-law’). The coinage of the expression postprawo in Polish may be motivated by the formal similarity between prawda (‘truth’) and prawo (‘law’). Moreover, the so-called Polish Constitutional Court crisis of 2015 might have sparked the need for the creation of postprawo (‘post-law’), i.e. the times or the state in which the law is no longer of primary importance and can be interpreted freely so that it fits the needs of the reigning party. Consider also the following examples:

(37) Post-prawda, post-logika, post-etyka. Obłędny Morawiecki, szalony cały PiS. Ale widać koniec. (https://oko.press/post-prawda-post-logika-post-etyka-z-dodatkiem-obledu-a-la-morawiecki-co-z-tym-robic/)

(English:‘Post-truth, post-logic, post-ethics. Mad Morawiecki, the whole PiS (Law and Justice party) crazy. But the end is near.’)

(38) Postprawda, postprawo i minister Dworczyk. (https://marcinmatczak.pl/index.php/2018/10/31/postprawda-postprawo-i-minister-dworczyk/)

(English: ‘Posttruth, postlaw, and minister Dworczyk’)

(39) Postprawda i post-Kościół (http://wiez.com.pl/2018/05/09/postprawda-i-post-kosciol/)

(English: ‘Posttruth and post-Church’)

(40) Prawda i „postświat” (http://gadowskiwitold.pl/publicystyka/prawda-i-%E2%80%9Epost%C5%9Bwiat%E2%80%9D)

(English: ‘Truth and postworld’)

The existence of such new formations in Polish testifies to the fact that the productivity of the prefix post- has already started spreading beyond English. In English, though, the emergence of multiple novel formations means that the new radial category has become accepted by speakers and conventionalised up to a point. This fact, in turn, provides evidence for the emergence of a new semantic category within the radial network of meanings already present in the prefix. Changes in the sociopolitical context, the omnipresence of lies and half-truths, degeneration of trust, disappearance of genuine shame and increasing reliance on emotion instead of fact have led to the need for additional means of linguistic expression. The prefix post- has evolved so as to cater to this need and make available an extra semantic tool at the morphological level. It is an economical shortcut which saves a lot of lexical description and expresses the newly emerging sociopolitical concepts in a simple, yet ingenious and very convenient way.