1. INTRODUCTION

Recent efforts to widen access to electroacoustic music through education (e.g. Landy Reference Landy2012) build upon a long-standing tradition. The legacy of musique concrète is particularly rich in this regard. Reform of musical pedagogy was a favourite concern of Pierre Schaeffer’s and an active interest of the Groupe de Recherches Musicales (GRM) from its beginnings (Delalande Reference Delalande1976). From his early days as a scoutmaster (Nord Reference Nord2007) to his mid-1950s stint advising the training of radio engineers for the French overseas broadcasting service (Damome Reference Damome2012), teaching held an important place in Schaeffer’s career. His passion for discipline, and especially the self-discipline which characterises his prescriptions for listening, was informed by a deeply personal faith rooted in both traditional Catholic mysticism and the syncretic teachings of Georges Ivanovich Gurdjieff (Kaltenecker Reference Kaltenecker2010). For Schaeffer’s students, the task was not simply to master a new musical language but to remake themselves as authentically ‘conscious’ listeners. It is no coincidence that Schaeffer’s theory gives such a central place to the practice of solfège. Well documented in Schaeffer’s writing and interviews, the discipline of acousmatic solfège confronted students with a series of ‘deconditioning’ exercises aimed at undermining the intervention of cultural or scientific habit in the work of composition and analysis (Schaeffer Reference Schaeffer1966: 478–9; Pierret Reference Pierret1969: 73–4). Its outcome was a generalised language of sonic phenomena, applicable equally to the understanding of musics outside the Western system of notation and to the invention of new musical languages (Schaeffer Reference Schaeffer1966: 602–3). Education has also played a significant role in disseminating Schaeffer’s vision outside of France. Indeed, it may be that Schaeffer’s influence on contemporary electroacoustic expression is most strongly felt not so much in the new musical genres composers have engaged with since his time but in the ways they have been taught to use their ears.

The history of acousmatic music in Quebec provides strong support for an account of the growth of a transnational Schaefferian network that acknowledges the vital role of its disciplinary and pedagogical links. This is especially important because it complicates received wisdom about the origins of acousmatic theory and practice. Consider the scene-defining article, now 20 years old, in which French emigré Francis Dhomont (Reference Dhomont1996) articulated what he heard as the fundamentally eclectic character of the Quebecois ‘sound’. Dhomont imputes the emergence of a distinct ‘school’ of composers in Quebec to an inborn ‘musical bilingualism’, a hybrid disposition with essentially North American and essentially European aesthetic qualities. This may seem fair enough on the surface. But Dhomont’s representation of the way Schaeffer’s teachings were first transplanted into this fertile soil is misleadingly incomplete. Moreover, his definition of acousmatic music backgrounds the contributions of local colleagues. The term ‘acousmatic’ and the musical ‘notion it represents’ for Dhomont ‘are founded on Schaefferian phenomenological concepts, extend musique concrète, and symbolise the aesthetic views of composers either belonging to or following the tradition of France’s Groupe de Recherches Musicales de Paris’ (Dhomont Reference Dhomont1996: 25). This emphasis on origin and continuity clearly privileges native French voices such as Dhomont’s over those of the Quebecois musicians who welcomed him into their midst. These forerunners were ‘curious’ about the medium, Dhomont suggests, but not fully inculcated until his own authority had been properly established. Anglophone researchers have since become accustomed to hearing Dhomont named as the sole bearer of the Schaefferian torch to North America (Collins, Schedel and Wilson Reference Collins, Schedel and Wilson2013: 123). The famous anecdote of his independent invention of musique concrète using a wire recorder helps to solidify his claims to authentic authority (Dhomont and Mountain Reference Dhomont and Mountain2006: 10). For Dhomont, the specificities that marked the ‘Quebec sound’ could be characterised in terms of divergence from the natural orthodoxy of his own ‘cinema for the ears’. ‘Crossbreeding’ of acoustic with electronic sources and other ‘postmodern’ fusions of materials and genres are cast as markers of an essential New World hybridity, a kind of genetic mutation in an otherwise pure national heritage (Dhomont Reference Dhomont1996: 26–7).

It is important to note the historical context in which Dhomont wrote this assessment. On one hand, acousmatic music had never held more institutional power than it did in the mid-1990s. On the other, it faced a mounting crisis of legitimacy. In a cultural landscape increasingly shaped by electronic dance musics and other ‘pop’-derived experimentalisms, acousmatic composers came under attack as convention-laden elitists, disconnected from the progress of technological and aesthetic evolution (Waters Reference Waters2000; Thibault Reference Thibault2002; Haworth Reference Haworth2016; Adkins, Scott and Tremblay Reference Adkins, Scott and Tremblay2016: 106–7). Progressive voices fled to the margins, and acousmatic music was re-defined, both from within and from without, as the conservative orthodoxy young composers are familiar with today. To affirm the continuity of an acousmatic tradition in this context, even in the uniquely diverse context of the ‘École de Montréal’, was surely an act of defiance against the rapid disintegration of its avant-garde authority. Perhaps, then, we can think of Dhomont’s article and the acousmatic orthodoxy it names as a kind of deceptive counter-reduction. It certainly over-emphasises the social and aesthetic cohesion of the Quebecois reception of Schaeffer’s ideas. Understood in this simplified manner, it is no wonder that acousmatic music became such a useful straw-man for millennial postmodernists. In parallel, however, with recent calls for a ‘post-acousmatic’ musical practice (Adkins et al. Reference Adkins, Scott and Tremblay2016), it is now pertinent to deconstruct the history of the ‘acousmatic orthodoxies’ that are supposed to have dominated in places such as Montreal. Many points in Dhomont’s narrative should stand in question. Was Dhomont the ‘common ancestor’ bringing the concepts and disciplines of acousmatic music with him from France, or were there forgotten figures already integrating Schaeffer’s ideas differently before Dhomont’s arrival? In short, did pluralism actually precede dogmatism?

An examination of the influential teaching career of Dhomont’s contemporary Marcelle Deschênes confirms that the answer to both questions is yes: there is a significant counter-history to be discovered in the shaping of Quebec’s acousmatic tradition. Deschênes belonged to the first Quebecois cohort to study on the GRM’s course at the Conservatoire de Paris in 1968 and 1969, and spent two more years learning from composers and musicologists there. Upon her return she delivered comprehensive undergraduate courses in ‘Morpho-typology’ at Université Laval in Quebec City from 1972 to 1977, and then went on to become the principal architect of the first electroacoustic curriculum at Université de Montréal in 1980 (Lefebvre Reference Lefebvre1991, Reference Lefebvre2009). Her personal archive, to which she has graciously granted me access since the summer of 2015, contains a wealth of writing and teaching material showing that she had developed a robust and independent interpretation of Schaeffer’s theoretical work several years before Dhomont arrived in Montreal. The collection contains over 25 years of teaching material, analysis and theoretical notes, including an unfinished companion volume to Schaeffer’s treatise, which Deschênes conceived as an account of the dynamics of musical organisation. Most importantly, this work establishes exactly the kind of pluralistic, intermedial orientation that Dhomont characterises as secondary to his own intervention, but does so prior to his arrival.

Although she is fondly remembered by her students, Deschênes’s definitive role in the development of acousmatic thought in Quebec has been neglected for many of the same reasons that women’s voices have always been pushed to the margins of electroacoustic music circles (McCartney Reference McCartney2006; Rodgers Reference Rodgers2010; Born and Devine Reference Born and Devine2015). Musicologists have also traditionally tended to privilege productive composition over the reproductive labour of teaching (Citron Reference Citron1993; Cusick Reference Cusick2001). By looking more at historical teaching material, I argue that we can both move towards correcting this imbalance and provide a more accurate depiction of the social dynamics of the acousmatic tradition. Schaefferian thinking was influential not only as it informed composition, I suggest, but also as an ‘acoustemology’ (Feld Reference Feld2015), fostering new ways of practising and conceptualising musical audition. If we are to understand acousmatic music not only as a genre but also as a socially and historically cohesive tradition or scene, a heterogeneous account of its construction that includes education is essential.

2. Marcelle Deschênes as Music Educator

Marcelle Deschênes was born in 1939 in the small village of Price on the south shore of the Saint Lawrence River in eastern Quebec. Encouraged by her mother, a popular local school teacher, Deschênes took up poetry, photography and the piano as a young child. She left the village as a teenager, after finishing her studies, to work as a pianist for the new Radio-Canada television station in Matane, Quebec. In 1962 she moved to Montreal where she continued to support herself as a pianist while studying composition at Université de Montréal under Jean Papineau-Couture and Serge Garant. Her social circle there included the nationalist poet Raôul Duguay, and she was similarly attracted by the radical cultural politics of the time. Her later student compositions reflect the rising importance of vernacular theatre and free improvisation in Montreal’s avant-garde. Groups such as Jazz Libre du Québec and Duguay’s Infonie sought to give a stronger voice to the socialist independence movement by amplifying its solidarity with the decolonisation struggles of the global south and the black civil rights movement in the United States (Mills Reference Mills2010; Stévance Reference Stévance2011; Fillion Reference Fillion2016). Deschênes was particularly receptive to the intermedial quality of these experiments. Her final examination work, 7+7+7+7 ou aussi progression sur la circonférence, du jaune au rouge par l’orange, ou du rouge au bleu par le violet, ou même embrassant le pourtour total (7+7+7+7 or also progression on the circumference, from yellow to red by orange, or from red to blue by violet, or even embracing the whole perimeter) (1968), was serial in form so as to appease her teachers, but its material was transposed from visual sources using a method inspired by the theories of Paul Klee (Reference Klee1964). She carefully colour-coded the notation to correspond with sections of Klee’s 1932 painting Garten Rhythmus, and added small drawings of her own to the score so as to guide the interpretation of aleatory passages.

It was around the same time that Schaeffer’s ideas began to find an audience in Canada. Schaeffer visited Montreal for the first time in 1968 as part of a UNESCO conference on culture and mass media (Beaucage Reference Beaucage2008). The following year he returned for a week of seminars at the invitation of the musicologist Maryvonne Kendergi, who taught in the Faculty of Music at Université de Montréal.Footnote 1 Schaeffer’s ideas had a particular resonance for separatist musicians hoping to achieve what they imagined as a ‘decolonisation of the ear’ (Duguay Reference Duguay1971). Schaeffer’s call to ‘practice’ the ear as if it were an instrument seemed a potentially useful strategy in the struggle to foster a revolutionary separatist consciousness through the mass media and the arts. Philosophy student Lucie Hirbour-Coron wrote that Schaeffer’s ideas should encourage media and policy-makers to ‘invent the suitable conditions for a certain freedom of listening’ (‘inventer les conditions propices à une certaine liberté d’écoute’) (Hirbour-Coron Reference Hirbour-Coron1971). Under the influence of high-profile public events in Montreal such as the International and Universal Exposition of 1967, a clear connection began to develop in Quebec between artistic modernism and the modernisation of the senses through public education (Kenneally and Sloan Reference Kenneally and Sloan2010).

In autumn 1968, funded by prizes in photography, piano and composition, as well as bursaries from the governments of France, Quebec and Canada, Deschênes decamped to Paris to join the GRM’s first formal conservatory course. Entitled Musique fondamentale et appliquée à l’audio-visuel (Fundamental music applied to the audiovisual) the course consisted of a mandatory training in Solfège expérimental (Experimental solfège) led by Guy Reibel and Henri Chiarucci, as well as three optional seminar streams: one for performers entitled Entraînement à l’exécution au microphone (Training in execution at the microphone), with Bernard Parmegiani and Albert Laracine; a more philosophical seminar aimed at non-music students entitled Musique fondamentale (Fundamental music) with Pierre Schaeffer and Daniel Charles; and one specifically for composers entitled Stage de musique expérimentale (Practicum in experimental music) with François Bayle and Ivo Malec (Groupe de Recherches Musicales 1968). Deschênes’s interests were broad, but she was particularly attracted to Schaeffer’s ideas about shared structures of auditory perception across cultures. She frequented the GRM courses for three years and complemented her studies with courses in comparative music analysis with the ethnologist Claude Laloum at Vincennes. Under the combined influence of Laloum and Schaeffer she began to explore the use of pre-existing musical materials – anything from quotations of Mozart to recordings of Burundian ceremonial music – gathered from her analysis courses. Her allegiance with musique concrète was focused on theory and process more than results. On a typewritten sheet inserted into her classroom notes she boiled Schaeffer’s message down to three ‘postulates’ – the primacy of the ear (la primauté de l’oreille), the return to living acoustic sources (le retour aux sources acoustiques vivantes), and the search for a language (la recherche d’un langage) – and five ‘points of method’ – decoding the (generalised) solfège (déchiffrer le solfège (solfège généralisé)), creating sound objects (créer des objets sonores), discovering the (technical) procedures (découvrir des procédés (techniques)), realising studies before conceiving works (material studies) (réaliser des études avant de concevoir des oeuvres (études de matériaux)) and learning to work (apprendre à travailler) (Deschênes no date a).

Shortly after her return to Quebec in 1971 she took up a position in the fledgling Studio de musique électronique d l’Université Laval (SMEUL) directed by Nil Parent at Université Laval in Quebec City. There Deschênes played alongside Parent and students Jean Piché and Gisèle Ricard in the pioneering Groupe de l’interprétation de musique électroacoustique (GIMEL). Among the studio’s other students were future electroacoustic composers Robert Normandeau, Alain Thibault and Pierre Ménard (Ricard Reference Ricard2009). Parent was highly protective of his position as founding composer in the studio, and Deschênes found herself forced to make the best of a supporting role in research and pedagogy. Nevertheless, teaching allowed Deschênes to continue mining the pluralist, comparative vein she had discovered in Paris. As she wrote in a course proposal at the beginning of her first year on the faculty, ‘the question of initiation into music may be reduced to a formula: initiation by musical facts (music as heard and as made) and no longer by musical systems’ (‘La question des entrées de la musique pourrait être réduite à une formule: entrée par les faits musicaux (musique à entendre et à faire) et non plus par les systèmes musicaux’) (Deschênes Reference Deschênes1972b: 1). Over the ensuing decade she would develop the implications of this formula.

First she devised a series of courses based on Book V of Schaeffer’s treatise with the title Morpho-typologie. Her definition of the topic emphasised the breadth of possible applications. ‘Sonic morpho-typology’, she wrote, ‘favours the personal constitution of a new vocabulary sensitive enough to provide a solid base for improvisation, composition and the comprehension of musical facts which no longer correspond to the reference system of Western classical music’ (‘La morpho-typologie sonore favorise la constitution personnelle d’un vocabulaire nouveau susceptible de fournir une base solide à l’improvisation, à la composition et à la compréhension des faits musicaux qui ne correspondent plus au système de référence de la musique classique occidentale’) (Deschênes Reference Deschênes1977c: 7). In the first year, students focused on analysing and describing sound objects from a variety of sources including their own recorded improvisations, canonical works of classical music and the university’s collection of ethnographic recordings. The goal here was to impart to students an intuitive grasp of musical materials based on listening alone. A library of sound examples began to take shape in conjunction with the course.

In the second year of the Morpho-typology course, attention turned to the dynamics of musical form. Here, Deschênes noted, Schaeffer’s treatise could no longer function as a guide:

The object designates a kind of sphere which listening grasps in the blink of an ear while sound unfolds and manifests in duration, is a living process, an energy in action integrated into a much larger musical structure. It thus proves to be necessary to give movement back to the object that Schaeffer immobilised in order to better understand its materiality, and to add to the masterful work of the Treatise on Musical Objets a systematic study of the laws, the energetic logics, and the processes that animate the them. (Deschênes Reference Deschênes1977c: 13)

(L’objet désigne une espèce de sphère que l’écoute saisit d’un coup d’oreille, alors que le son se déroule, se manifeste dans la durée, est un processus vivant, une énergie en action intégrée à une structure musicale beaucoup plus vaste. Il s’avère donc nécessaire de remettre en mouvement l’objet sonore que Schaeffer a immobilisé pour mieux saisir la matière et d’ajouter au magistral travail du Traité des Objets Musicaux, une étude systématique des lois, des logiques énergétiques, des processus qui les animent.)

In seeking to redress Schaeffer’s refusal to broach questions of form (Schaeffer Reference Schaeffer1976; Chion Reference Chion1983: 166–7), Deschênes’s research during this period also anticipates later attempts to extend acousmatic thinking to large-scale structural dynamics, such as the ‘spectromorphology’ of Denis Smalley (Reference Smalley1986). For inspiration she turned back to the intermedial strategies she had borrowed from Klee’s (Reference Klee1964) posthumously published Bauhaus lectures as a student. Thus, in addition to their now-familiar listening and analysis sessions, Deschênes tasked her students with the invention of new graphic and theatrical strategies emphasising what she referred to as the ‘dialectical’ entanglement of oral and written musical traditions (Deschênes Reference Deschênes1977c: 15). As early as 1972, then, acousmatic theory was already being taught to Quebecois students, not as a formal practice exclusive of existing genres but as a synthesis of post-serialist, experimentalist and ethnographic forms of production.

The official appetite for educational experimentation was high in Quebec at this time. While the idealism of the revolutionary separatists had begun to subside, the practical work of social and institutional transformation had just begun. One of the largest projects affecting musical life was that of secularising the education system. Until the 1950s, much of Quebec’s school system fell under the control of the Catholic clergy. Girls were often segregated from boys, rural children were disadvantaged in comparison with those in the cities, and university attendance was low (Dumont, Jean, Lavigne and Stoddart Reference Dumont, Jean, Lavigne and Stoddart1983). A royal commission was assembled in 1961 to study alternatives, and a series of major reforms followed over the ensuing decade. At the primary level, particular emphasis was placed upon upholding educational ‘rights’ in the spirit of the UNESCO charter’s recommendations on freedom of thought and upon modernising teacher training in line with contemporary ideas about childhood development (Corbo Reference Corbo2002). According to ministry of education guidelines, music should play a central role in connecting these goals:

Because, as a basic principal, music exercises an extremely effective action on the development of the child’s personality, from this point of view it is important, in the context of elementary education, to give to all children without exception a valid musical education which, in addition to dispensing joys of exceptional quality, constitutes a marvellous means of developing their faculties of intelligence, attention and judgement. (Direction Générale de l’Enseignement Élémentaire et Secondaire 1973: 3)

(Puisque, par principe de base, la musique exerce une action extrêmement efficace sur le développement de la personnalité de l’enfant, à ce point de vue il importe, dans le cadre de l’enseignement élémentaire, de donner à tous les enfants sans exception une éducation musicale valable qui, en plus de prodiguer des joies d’une exceptionnelle qualité, constitue un merveilleux moyen pour développer ses facultés d’intelligence, d’attention et de jugement.)

Progressive models in France provided some inspiration (e.g. Drott Reference Drott2009), but reforms in Quebec were more profound and thus required a more liberal orientation.

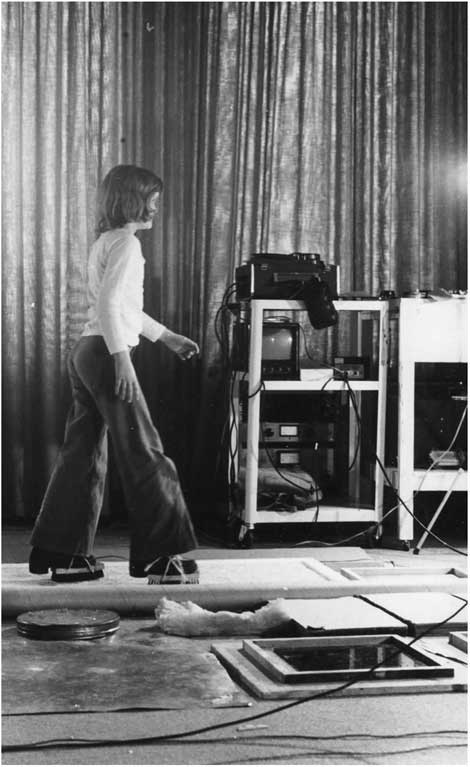

In 1974 Deschênes was placed in charge of a new research project with the goal of developing experimental music education strategies for elementary classrooms. Working in collaboration with the 12 students in her Morpho-typology course, she guided 60 children in small, age-integrated groups through a series of weekly auditory awareness workshops (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Marcelle Deschênes, Pierre Pouliot and students at the Studio de musique électronique de l’Université Laval. Private archives of Marcelle Deschênes. Used with permission.

Students developed listening exercises for the children in the form of games or theatrical exercises. They would then record their sessions with the children for later analysis, or for reuse in their own compositions. One of the most important outputs of this project for Deschênes was Moll: opéra lilliput pour six roches molles (Moll: Lilliputian Opera for Six Soft Rocks) (1976; Deschênes 2006), a set of music theatre miniatures scored for two clarinets, three trombones, three percussion groups, children’s toys and tape. Both the tape part and the playful storyline are taken from documentation made during the children’s workshops at Université Laval. Thematic material highlights poetic contrasts in scale: childhood meets death, pebbles found on the beach of the lower Saint Lawrence become stars, insects gather into storms. The listening score is illustrated with clippings from comic books and newspapers showing the narratives of the various episodes. Moll was popular with audiences and gave a significant boost to Deschênes’s reputation. It was premiered by the Société de musique contemporaine du Québec in 1976, and won first prize at Bourges in the mixed music category in 1978 (Deschênes Reference Deschênes1980; Mountain Reference Mountain2003: 19).

Following mounting personal confrontations, GIMEL was dissolved in 1977 (Ricard Reference Ricard2009) and Deschênes moved to Montreal (Daunais and Plouffe Reference Daunais and Plouffe1992). Deschênes quickly made contact with the music department at Université de Montréal to offer her services as a teacher and propose further research on ‘the interaction between auditory perception and creation (sonic or otherwise)’ (‘sur l’interaction entre la perception auditive et la création (sonore ou autre)’) (Deschênes Reference Deschênes1977b). From Laval she had brought with her a growing library of sound examples and listening exercises designed to initiate students into the language of Schaeffer’s treatise. Her reputation as a composer was also on the ascent. In the ensuing years she helped found ACREQ (Association pour la création et la recherche électroacoustiques du Québec), gave birth to a son and set up the private studio Bruit Blanc at her home in Outremont. At the same time, Université de Montréal began to intensify its support for electroacoustic research. The first electroacoustic research at the university had taken place in an informatics group organised by Denis Lorrain in 1969. A studio was established under the direction of acoustician Louise Gariépy in 1974, but it had functioned mainly as a technical service to the rest of the department. In 1979, with the approval of a new music building, the university devoted $420,000 to new electroacoustic facilities, this time with a compositional focus (Roy no date; Gariépy Reference Gariépy1983). Plans began to take shape to complement the studio with a new curriculum and a new professorship. In the winter of 1979–80, Deschênes gave a condensed version of her Morpho-typology course in a series of five seminars at Université de Montréal under the title Le ‘Spectacle perceptif’ des musiques électroacoustiques (The ‘perceptual spectacle’ of electroacoustic musics) (Deschênes Reference Deschênes1979). While Dhomont had visited the previous year and was considered by many to be a strong candidate for the post, his ambitions were soon upset. Deschênes succeeded instead on the merit of her strong teaching portfolio, her previous research experience and the detailed curriculum she had already worked out in Quebec City. She adapted the new syllabi in collaboration with Gariépy and Lorrain, and took over direction of the studio the following autumn. Dhomont joined the department as a part-time teaching adjunct in 1983, but never took up a full faculty post, and until his departure in 1996 was only ever permitted to offer individual instruction as a co-supervisor. Throughout the rise of Dhomont’s ‘school’, the studio remained under Deschênes’s leadership.

3. Summary of Selected Course Contents

Much of the teaching material and documentation from Deschênes’s early educational research survives unpublished in her private archive in Montreal. Alongside a vast library of secondary literature on auditory perception, Deschênes’s teaching archive includes: plans and student assignments from four years of her Morpho-typology course; plans, exercises, student assignments and photographs from her research project for children; administrative material, syllabi, lesson plans, student work and analysis examples from her courses in Perception auditive (Auditory perception) and Techniques d’écriture électroacoustique (Electroacoustic production techniques) at Université de Montréal; and more than 20 boxes of alphabetised index cards comprising a projected companion to Schaeffer’s treatise which Deschênes called the Lexique (Lexicon). A collection of over 250 audio and videotapes containing examples from the Morpho-typology courses and documentation of the workshops survives as well. This material provides a vivid picture of Deschênes’s theoretical and practical engagements with the ideas she had brought back from the GRM after her studies there. Indeed, it shows that Deschênes’s work anticipates Dhomont’s assessment of the hybridity of the Montreal sound by two decades.

The most notable difference between Deschênes’s teaching of the treatise and the later ‘orthodox’ reading that appears to have taken root in the 1980s is her strong emphasis on aesthetic pluralism. Although she did often use examples from works of musique concrète, she never did so to the exclusion of other styles of contemporary music. Analyses of Schaeffer’s Étude aux objets (1958) sit side by side with analyses of work by Xenakis, Stockhausen, Berio, King Crimson, clippings from the American avant-garde magazine Source and ethnographic recordings from Asia and Africa. Deschênes held a strong conviction that Schaeffer’s ideas about auditory perception provided the basis for a rigorously comparative approach. As she wrote in her plan for the first year of Morpho-typology, the first rules of a generalised solfège should be to ‘accept sound objects of all provenances’ (‘accepter les objets sonores de toutes provenances’) and to ‘accept all musics (classical occidental, contemporary, oriental, african, etc...)’ (‘accepter toutes les musiques (classique occidentale, contemporaine, orientales, africaines, etc...)’) (Deschênes Reference Deschênes1972a: 3). In effect, her aim was to use the language of the treatise to redefine music as the art of listening beyond discrimination. From the point of view of the treatise, this of course allowed students to discover the internal logics of different musics by comparing them on the basis of their engagement with sound as a medium rather than on value-laden criteria such as rhythm, harmony and melody. From the point of view of policy-makers and administrators, Deschênes’s approach had the advantage of promoting ethical practices suitable for the modernisation of the Quebec education system: a tolerance of cultural difference, a sense of historical progress, an awareness of the contingent and perspectival nature of perception, and a critical engagement with media technologies. A workshop entitled Le Marché des Sons (The market of sounds) encapsulates these values (Figure 2). Circulating between differently themed ‘shops’, children in the workshop learn to select, evaluate, and memorise sounds through acts of purchase and exchange (Deschênes Reference Deschênes1977a). Although Deschênes describes its purpose as ‘to encourage the knowledge of musics and sounds of all contexts and of all periods’ (‘pour favoriser la connaissance des musiques et des sons de tous contextes et de toutes époques’) (Deschênes Reference Deschênes1982), there is also a clear sense of teaching the children to listen as consumers in an increasingly globalised market of commodity recordings. Listening became the basis for a kind of personalised ownership of musical works, in a similar sense to that which Peter Szendy has theorised more recently (Szendy Reference Szendy2008). As several of Deschênes’s compositions encompass quotations not only from the wider repertoire but also often from the work of students and collaborators, her creative work may also be heard with a similar ethos in mind.

Figure 2 Le Marché des Sons with facilitator Guy Isabelle. Private archives of Marcelle Deschênes. Used with permission.

Another significant feature of Deschênes’s early teaching was its emphasis on multidisciplinarity and intermediality. She has frequently attributed these principles to her reading of Klee, who sought to provide a unified framework for the temporal and spatial structures of music and drawing (Mountain Reference Mountain2003). Although the GRM at this time certainly did have an interest in audiovisual projects, the kinds of direct intermedia analogy Deschênes borrowed from Klee were an obvious departure from Schaeffer’s insistence on the special status of sound. Indeed, Klee’s roots in the Bauhaus (Jewitt Reference Jewitt2000) gave him strongly modernist implications, and accordingly his ideas found far more purchase among the serialists than at the GRM (Grant Reference Grant2001; Mussgnug Reference Mussgnug2008). Nevertheless, Klee remains an important source of inspiration for cross-modal experiments in analysis, composition and music therapy today (Waters Reference Waters2000; Smeijsters Reference Smeijsters2003; Dickinson Reference Dickinson2016). Intermediality in Deschênes’s teaching was not limited to the colourful listening scores that frequently accompanied her analyses. The workshop Les Roches Molles (The Soft Rocks), from which material was gathered for the composition of Moll, has a distinctly Bauhaus feel, linking sound, costume, bodily gesture and narrative to explore analogies between the material quality of simple natural objects – a collection of coloured stones worn smooth by the water – and the imaginary quality of the distant stars. Intermediality also remained at the forefront of Deschênes’s compositional practice throughout her career. Her first major work as a faculty member at Université de Montréal, for instance, was the large-scale theatre collaboration OPÉRAaaaAH! (Deschênes 1983) premiered by the SMCQ, which included material by Raôul Duguay, conceptual artist Monty Cantsin (Istvan Kantor) and her student Alain Thibault, as well as contributions by a variety of visual artists and dancers. The multidisciplinary nature of OPÉRAaaaAH! was so extreme that it posed significant challenges for the documentation methods available at the time. Fragments of the score along with a few recorded excerpts from the tape part, production stills and rehearsal videos are all that survive, a problem which contributes to the present-day neglect of Deschênes’s work.

Finally, Deschênes’s teaching was unique for its time in seeking a dynamics of musical organisation to accompany Schaeffer’s conception of the musical object. Deschênes found support for her ideas in the new styles of structuralist analysis that circulated in journals such as Musique en Jeu (Donin Reference Donin2010). Where no traditional ‘system of reference’ was in evidence, structuralist analysis proposed that musical works could be re-conceived as relational systems of salient contrasts between minimally significant units (Chiarucci Reference Chiarucci1973). Structuralist and phenomenological methods could be used in parallel, Deschênes wrote, to discover the links between objects in themselves and objects in dynamic relation (Deschênes no date b). In contrast with structuralism, however, Deschênes’s solutions to the problem of formal organisation remained resolutely intuitive and anti-reductive. Musical form was to be passionately experimental and intermedial, co-constructed through the interaction of sound, notation, instrumentation and listening. Bodies, images, stories and sensations should make equal contributions to the organisation of a work. Although the impulse to extend Schaeffer’s project here anticipates the later work of Denis Smalley, the differences are also clear. Smalley extends Schaeffer’s taxonomical impulse, insists upon well-defined categories of sonic motion and makes a sharp distinction between the auditory and non-auditory aspects of musical form. Smalley seeks a kind of certainty: listeners are understood to have heard correctly when they all have the same understanding of a piece (Smalley Reference Smalley1997: 109). Deschênes wants her listeners to have fundamentally different experiences from one another. Workshops such as Forêt tactile (Tactile forest) (Figure 3) and Faire entendre par les pieds (Making heard with the feet) (Figure 4), for example, use sonified gestures to generate musical form as a direct feedback to embodied, collective interaction (Deschênes Reference Deschênes1977a). Participants learn to listen as co-authors with potentially divergent conceptions of a work’s focus and evolution over time. Hence the strategy of Deschênes extension to Schaeffer’s treatise, her unfinished lexique, is not a taxonomy but a descriptive catalogue structured arbitrarily by the alphabet. The lexique is a tool for associating sounds not only with other sounds, but also with images, sensations, spaces and narratives without restriction.

Figure 3 Le forêt tactile. Private archives of Marcelle Deschênes. Used with permission.

Figure 4 Faire entendre par les pieds. Private archives of Marcelle Deschênes. Used with permission.

4. Conclusion

I have drawn upon newly excavated primary sources to support my contention that, although an acousmatic ‘orthodoxy’ in Quebec may be said to have been established under the influence of French and British theorists in the 1980s, acousmatic thinking had already flowed into the Quebecois electroacoustic scene by pre-existing channels for over a decade, especially through the now neglected work of Marcelle Deschênes. Furthermore, I argue that it was Deschênes’s pluralist and postmodernist interpretation of acousmatic theory that most strongly influenced the Quebecois electroacoustic aesthetic and not the teaching of Francis Dhomont, which existing histories tend to overemphasise. Although Deschênes was certainly not alone in promulgating this version of Schaefferian thinking, she was particularly influential as a teacher and counts many of the main figures in the Quebecois acousmatic tradition among her students. The rise of the separatist movement and the secularisation of education in the 1960s and 1970s gave strong support to Deschênes’s interpretation of the treatise and created a fertile environment for her research in music education.

There are certainly a variety reasons why this body of work has suffered such neglect. One of them is systematic sexism. But it is not my intention to simply accuse previous authors of suppressing historical facts in their own self-interest. As long as a gender imbalance persists, all practitioners and educators share responsibility for it. My point is rather that it does not help to make prescriptive cuts in the history of electroacoustic music based on tropes about exclusive theoretical schools which are unsupported by empirical evidence. Among practitioners Schaeffer’s theories have always been understood in conversation with a wide range of literatures from disciplines as diverse as semiotics, musicology, psychology, cognitive science, cybernetics, acoustic, anthropology, sociology and various branches of engineering. The task of historians is not to distill the essences of these different knowledges but to understand how they shaped each other in interaction. Instead, as Ben Piekut (Reference Piekut2011) has argued, observers should pay attention to how experimental music traditions are made and remade over time through distributed socio-technical action. The history of music education gives us one more body of evidence to consider, and this can only help us to draw more accurate conclusions.