Introduction

Traditionally, with historical institutionalism, the choices made when an institution is formed, or policy initiated, will have a persistent influence over that policy (Peters, 1999: 210). However, crises can bring abrupt institutional change, as they present leaders with an opportunity to enact new plans and realize new ideas by embedding them in the institutions they establish. Consequently, a regularly invoked interpretation of institutional change has divided history into “normal periods” and “critical junctures,” during which major change is possible (Gorges, 2001: 156).

However, Pierson (2004: 5–6) argues that “many of the key concepts needed to underpin analyses of temporal processes, such as path dependency, critical junctures, sequencing, events, duration, timing, and unintended consequences, have received only fragmented and limited discussion.” This raises questions as to both the understanding, and employment, of these concepts. Consequently, critical junctures have remained underexamined and insufficiently specified. Thus, this paper seeks to outline a framework within which to identify critical junctures. If we can identify a critical juncture with some degree of certainty, then we can point to a period of change as significant with greater confidence than was previously possible.

In contextualizing where the remoulded critical juncture approach fits within the wider political science literature, the paper will initially focus on the approaches used by historical institutionalism to deal with, and identify, change. The paper will then examine the characteristics of critical junctures, the use of the approach and how the approach is remoulded to give it a rigour it previously lacked. The remoulded approach is then employed in a case study of the change in the ICTU's influence over public policy in Ireland in 1987 to see if this constituted a critical juncture. The conclusion will summarize the main arguments of the paper: that remoulding the critical junctures approach improves our understanding of the concept, and our ability to identify change.

Variation on the Examination of Institutional Change

Clearly, attentiveness to history is important, as tracing politics through time is helpful for identifying the boundary conditions for particular theoretical claims. Even more significant, the emphasis historical institutionalists place on conjunctures, and sequencing, draws attention to the temporal connections among social processes, and highlights the importance of meso- or macro-level analysis of institutional configurations. Yet, despite this, the significance of time and historical processes in historical institutionalism have been downplayed in deference to the attention devoted to the institutional side of the approach. However, “questions of institutional evolution and change have [also] attracted very little systematic attention” (Thelen, 2004: 24). This dearth of attention to historical processes, and institutional change, led political scientists to rely on societal functionalism, and the actor-centred version of that approach (Pierson, 2004).

An alternative to functionalist explanations of institutional development is path dependence. According to Thelen, “[t]his perspective has been more prominent among scholars associated with historical institutionalism” (2004: 26). It argues that early choices have a persistent influence thereafter (Peters, 1999: 210). Ikenberry (1994: 16) captures the essence of a historical institutionalist approach to path dependence in his characterization of political development as involving critical junctures and developmental pathways. In an effort to assess how process, sequence and temporality can be incorporated into explanations, Haydu (1998) goes beyond the notion that past choices affect future process (Mahoney, 2000: 510). Cox (2001) advocates using the constructivist perspective to expand the path dependence approach, as this specifies the path-shaping power of ideas, and individual action, to alter institutional configurations. Mahoney's (2001) definition of path dependence sought to separate the critical junctures of institutional formation from the long periods of institutional stability. This approach is akin to the concept of punctuated equilibrium espoused by Jones (2001), and borrowed from neo-Darwinian evolutionary theory (Gould and Eldredge, 1977). Greener (2005: 62) suggests that combining insights from morphogenetic social theory with the concept of path dependence can provide a coherent framework for its use. But ultimately, strong tools for understanding continuity were not matched by equally sophisticated tools for understanding political and institutional change (Thelen, 1999: 388). Path dependence seems to encourage scholars to think of institutional change as either minor and continuous or major and abrupt (Streeck and Thelen, 2005).

In light of this, scholars have explored change by building on evolutionary models in the life sciences (Arthur, 1994; Jervis, 1997; Mahoney, 2000; Kerr, 2002; Pierson, 2004). Consequently, political science may move away from its fascination with physics and absolute laws, and look more like the life sciences, with their emphasis on contingency, context and environment. In this event, the goal will be to explain past (evolutionary) outcomes, and less to predict future ones. Ultimately, the necessary conditions for current outcomes occurred in the past.

Thelen (2004: 292) argues that “earlier generations of institutional analysis focused primarily on the effects of different institutional configurations on policies and other outcomes.” However, of late historical institutionalists have sought to demonstrate the ways in which institutions are remade over time (Thelen, 1999, 2000; Clemens and Cook, 1999; Pierson, 2004). The impetus behind this is dissatisfaction with research concentrating either on the analysis of institutional reproduction or institutional change. Without denying the existence of critical junctures, this research is discovering continuity in periods of upheaval, and gradual change in periods of peace that eventually become major transformations (Thelen, 2004: 292; Djelic and Quack, 2003: 309–10). This research views periods of change and stability as entwined.

Institutions are being viewed as changing in subtle but significant ways by a variety of mechanisms, amongst which are the concepts of layering, conversion, displacement and drift. Layering involves the placing of new constituents onto an established institution's framework. This can see new initiatives introduced to address contemporary demands, but then adding to, rather than replacing, pre-existing institutional forms. Consequently, older institutions will often have a highly “layered” quality (Stark and Bruszt, 1998; Schickler, 2001; Pierson, 2001). Conversion sees the acceptance of new aims, and the integration of new groups, into institutions, as forcing change in the roles these institutions perform. Thus, old institutions may persist, but be turned to different uses by newly ascendant groups. Layering and conversion provide for a more nuanced analysis of the kind of incremental change common in politics. However, it must be remembered that in either case, the original choices are likely to figure heavily in the current functioning of the institution. Displacement occurs when new models emerge and diffuse, calling into question existing, and previously taken-for-granted, organizational forms and practices (Streeck and Thelen, 2005: 19). Where an institutional arrangement dominates (Orren and Skowronek, 2004), it is vulnerable to change through displacement, as conventional arrangements are questioned or replaced in favour of new institutions and associated behavioural logics. Drift relates to the fact that there is nothing automatic about institutional stability (Thelen, 2004). Institutions need to be actively maintained, otherwise they can stagnate through drift (Hacker, 2002, 2005; Streeck and Thelen, 2005). Approaches that focus on the stability of existing institutions miss the slippage resulting from the impact of the world upon them.

This brings us back to the issue of attentiveness to history, and the question of how to conceptualize the starting point of analysis. “Because the decision to select any particular event as the starting point of analysis may seem arbitrary, the investigator is prone to keep reaching back in search of the foundational causes that underline subsequent events in the sequence” (Mahoney, 2000: 527). A meaningful beginning point is required. In this situation, the crucial object is the factor that sets development along a particular path, the trigger event (Pierson, 2004: 46). Abbott (1997) argues that periods of institutional genesis correspond to critical junctures. The junctures are critical as they place institutional arrangements on trajectories that are difficult to alter (Pierson, 2004: 135). But, as Pierson argues above, critical junctures have received only limited discussion. If critical junctures are of such import to the discipline, and yet have been so neglected, an examination of the approach is necessary to see if there is room for improvement.

The Characteristics of Critical Junctures

The literature on critical junctures argues that they are characterized by the adoption of a particular institutional arrangement, a choice of one option from amongst alternatives (Mahoney, 2000: 512). Once an option is selected it becomes progressively more difficult to return to the initial point (Levi, 1997). Critical junctures establish pathways that funnel units in particular directions. Once units begin to move in a particular direction they realize increasing returns, and continue in that direction (Mahoney, 2003: 53). Returns processes generate irreversibilities, removing certain options from the subsequent menu of political possibilities (Pierson and Skocpol, 2002: 9). With the returns process, the most important implication is the need to focus on the branching point, the critical juncture (Pierson, 2000: 263). According to this literature, the juncture is critical as it triggers a process of positive feedback.

But, as Hacker (1998, 2002) emphasizes, it is important to keep discussions of path dependence and critical junctures distinct, otherwise one runs the danger of concept stretching (Sartori, 1970). Pierson (2004) argues that institutional stability can result from non-path-dependent causes, implying that critical junctures should not be defined in part by the assumption that they initiate a path-dependent process. A critical juncture could lead to the existence of an institution whose persistence is not due to path dependence, but instead stems from other sources of institutional stability.

Nevertheless, a critical juncture points to the importance of the past to explain the present, and highlights the need for a broad historical vantage point. Moreover, this “suggests the importance of focusing on the formative moments for institutions and organisations” (Pierson, 1993: 602). While critical junctures are not the only source of change, they can, nevertheless, discredit existing institutions and policies, triggering change (Cortell and Peterson, 1999: 184).

The Use of Critical Junctures

The perspective from which critical junctures are analyzed has varied greatly. Some critical junctures involve considerable discretion, whereas others appear embedded in antecedent conditions. The duration of a critical juncture may involve a relatively brief period in which one direction or another is taken, or it can constitute an extended period of reorientation (Mahoney, 2001). This analysis can focus on the underlying societal cleavages or crises that precipitate a critical juncture, or it can concentrate primarily on the critical juncture itself. Nevertheless, central to this approach is an understanding that change is a cornerstone of comparative historical research and development.

The analysis of critical junctures has been influential in comparative politics. In 1991, Collier and Collier developed a framework for analyzing change, to determine if certain periods constituted critical junctures in the trajectories of national development in Latin America. Their definition of a critical juncture does not imply that institutional innovation occurs in short episodes or moments of openness (Thelen, 2004: 215). Although this definition does not imply the primacy of agency and choice over structure in critical junctures, its openness to longer-term institutional innovation, while highly commendable, means that it does not provide a framework for determining at what point change is sufficient to constitute a critical juncture. How can something that appears to be a period of transition, or incremental change (in their example the incorporation period in Peru took 23 years), be considered a critical juncture? There is no set of criteria identified, nor hinted at, beyond which one is no longer confronted with a critical juncture, and is dealing with incremental change.

Mahoney (2000: 535), seeking to conceptualize critical junctures, argued that the contingent period corresponded to the adoption of an initial institutional arrangement. Using Mahoney's criteria for specifying the beginning of sequences helps make more plausible claims that certain outcomes are generated through a path-dependent process. Mahoney (2001) tries to explain why the liberal period in the nineteenth century, in five Central American countries, constituted critical junctures. “The exact dates for this period differ for each country, though they roughly correspond to the 1870–1930 period” (Mahoney, 2001: 116). For Mahoney, critical junctures are seen as having taken decades to come about, while their after-effects are of shorter duration. This raises questions as to the impact of those periods of change, and whether they were in fact critical junctures, or just incremental changes as in conversion or displacement, discussed above.

However, the concept of critical junctures has also been widely employed in a diverse spectrum of research not particularly concerned with long-term change. Garrett and Lange (1995: 628) argue that electoral landslides create critical junctures by producing overwhelming mandates for policy and/or structural change. Casper and Taylor (1996) argue that critical junctures can be used in analyzing periods when authoritarian regimes are vulnerable to liberalization. The approach has also been utilized in relation to national-specific incidents and crises. Examining the watershed in American trade policy that was the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934, Haggard (1988: 91) argues that unanticipated events (critical junctures), in this case an economic depression, bring into question existing institutions, and result in dramatic change. Vargas (2004) has used critical junctures to examine the dynamics of the conflict in Chiapas, Mexico. Gal and Bargal (2002) analyze the emergence of occupational welfare in Israel using critical junctures, while Karl (1997) refers to multiple critical junctures in her analysis of how “petro-states” became locked into deeply problematic development paths.

Remoulding the Critical Junctures Approach

Although ongoing work on the concept of path dependence by Mahoney, and others, has lent greater precision to previous formulations of critical junctures (Thelen, 2003: 209), this paper seeks to improve our understanding of the concept. It seeks to “flesh out the often-invoked but rarely examined declaration that history matters” (Pierson, 2004: 2). This paper argues that the critical junctures concept lacks rigour—it doesn't offer a set of basic criteria by which to assess potential critical junctures to discover if they are critical junctures or just change that has taken place incrementally. Thus, a question that arises is how to distinguish between a critical juncture, and incremental change? Where does one draw the line as to what is, and what is not, a critical juncture? This is the decisive weakness at the heart of the approach.

Thus, whilst answering this question may place restrictions on the liberty with which the term can be employed, at least one will be able to say with greater certainty what is a critical juncture. While acknowledging that developing a set of universally applicable standards for exploring critical junctures would be near impossible in light of the vast milieu of topics under examination in political science, at least moving in that direction would constitute an advance for the discipline. Consequently, the standards developed will have to be broad and encompassing, but this will make the approach operationalizable and falsifiable. What is more, this focus on the temporal dimension provides possibilities for shaping some overlapping intellectual terrain for scholars working in diverse research traditions (Pierson, 2004: 8). When confronted by the infinite regress problem, a clear understanding of critical junctures would provide us with an unambiguous break in the chain with which to define the starting point for analysis. As Mahoney (2001: 8) puts it, “critical junctures can provide a basis for cutting into the seamless flow of history.”

As Collier (1998: 5) suggests, the close familiarity researchers have with their cases allows them to follow the long-standing advice of Przeworski and Teune (1970) to construct “system specific indicators,” as opposed to “common indicators.” To an extent, this is what is being advocated, in that the remoulded framework, in setting out a range of general standards that must be met for there to have been a critical juncture, leaves the particulars of each standard open to the researcher. As Grix (2004: 120) argues, this is the essence of social science research. In this situation, the more specific the framework, the less likely it is to be generally applicable. Thus, we are left wrestling with contradictory necessities: the need to be more rigorous—to advance the approach; and the requirement to be broadly applicable, if the approach is to be of use to the discipline as a whole. The only solution under these circumstances is to try and develop an approach that is more rigorous than its predecessors, but still as broadly applicable as possible.

To be able to recognize what is a critical juncture, we must be able to recognize what is not. Not all events, even seemingly significant events, can reasonably be called critical junctures. A critical juncture must be an event, prior to which a range of possibilities must exist, but after which these possibilities will have mostly vanished. It is here at the narrowing point, where possibilities close off, that we find ourselves, seeking a means of defining critical junctures. But instead of assessing critical junctures through counterfactual analysis (Fearon, 1991, 1996), this paper argues for the development of a framework for assessing them. In doing so, it avoids the problem of contingency in critical junctures, in that we will now have a clearer understanding as to why an event is, or is not, a critical juncture, and thus why that event came to pass. Moving away from contingency means that this approach cannot be linked to path dependency, which itself works on the assumption of contingency in order to encompass unpredictability (Mahoney, 2000: 515).

Critical Juncture

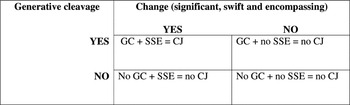

This paper argues that two separate elements are required for a critical juncture. First, it is necessary to identify the generative cleavage. This will involve an examination of the tensions that lead to the period of change. Second, the change must be significant, swift and encompassing. Here, a critical juncture will not be defined by the assumption that it initiates a path-dependent process. Non-path-dependent processes can result in institutional stability, and path dependence is less common than previously believed (Pierson, 2004; Thelen, 2004; Streeck and Thelen, 2005). Thus, it is conceivable that a critical juncture could witness the subsequent creation of a durable set of institutions whose persistence is not due to path dependence but to other sources of stability.

Generative Cleavage

An important part of the literature on critical junctures views them from the perspective of cleavages, placing emphasis on the tensions that lead up to the critical juncture. Since these cleavages are seen as producing, or generating, the critical juncture, Valenzuela and Valenzuela (1981: 15) refer to them as generative cleavages. The generative cleavage examined will vary depending upon the topic studied. “Traditionally, students of institutional change focused on the importance of situations of large-scale public dissatisfaction, or even fear, stemming from an unusual degree of social unrest and/or threats to national security” (Cortell and Peterson, 1999: 184). Wars, revolutions, coups d'état, economic crises, a change in the balance of power, electoral landslides, demographic changes and social movements may produce an overwhelming mandate for policy and or/structural change (Cortell and Peterson, 1999: 184). Such unanticipated events can discredit existing institutions and policies, triggering change (Tilly, 1975). As Katznelson (1997) stated, the macro-analysis of critical junctures that set countries along different developmental paths has long been the bread and butter of historical institutionalism. However, the attribution of critical junctures only to big exogenous shocks is not necessarily correct. Many less dramatic events, such as the urban/rural divide, or class differences, could be found to constitute generative cleavages, contributing to change that is significant, swift and encompassing.

Significant Change

Significant change is central to our understanding of critical junctures. As such, an attempt must be made to measure the significance of any change examined. Yet measuring significance will be difficult, as what constitutes significant change will vary as a function of the cases studied. However, instead of arguing, as has been the case up to now, that significant change must be a large event, and saying no more on the matter, this paper argues for the establishment of standards to enable the identification of the level of significance of change. We are attempting to introduce the concept of a more rigorous approach, without becoming overly rigorous to the point where the approach would be rendered of limited applicability. First, standards must be employed in measuring the level of change, and these should be clearly defined, and logical to the subject under examination. An operational definition measuring significance will have to indicate where the list comes from, and demonstrate that it was exhaustive and the values were mutually exclusive (Shoemaker et al., 2004). Ultimately, the levels set will be dependent upon the researchers' understanding of their topic, but setting out such standards will inculcate an inherently more rigorous approach than has existed up to now.

Swift Change

As we are dealing with critical junctures, periods of significant change, we assume that the change is not a long, slow process. Otherwise, we are dealing with incremental change. We must reject the notion of incremental change if we intend to address radical change. As a consequence, we add the notion of swiftness to our understanding of a critical juncture: the significant change must take place quickly.

Encompassing Change

The influence of the critical juncture must be encompassing. That is, it must have an effect upon all, or most, of those who have an interest in the institution or institutions it is impacting upon. In this regard we could be talking about things as vastly different as the populations of whole countries, the export community, ethnic minorities, all those working within a ministry, or the elderly pensioners in a society. Thus, we assume that for a change to be a critical juncture, its effects must impact upon a certain minimum percentage of those concerned. What this percentage could be would depend on the topic under examination.

The remoulded approach will enable us to better explain, and understand, past events. It will allow us to see clearly where change was incremental, and where it constituted a critical juncture, thus removing the mystery surrounding the issue of watersheds in politics. For Thelen (2000: 101) a critical juncture is environed by its location within a temporal field, its place within a sequence of developments. In this case, temporal context is central to our understanding of a critical juncture. Therefore, each critical juncture must be unique. This is the difficult part, in trying to establish standards, and bring a level of rigour that is universally applicable, for an area of research marked by its uniqueness.

This definition of a critical juncture gives rise to four possible sets of findings (see Figure 2). Only in the top left-hand box is a critical juncture possible. In any of the other locations in the diagram, the conditions for a critical juncture are not met. In the lower left-hand box, a generative is not identified, but the criteria for change (significant, swift and encompassing) are spelled out. This relates to a situation in which the nature of the change examined conforms to the criteria for a critical juncture, but the generative cleavage examined does not. Such a finding points to the possibility of an alternative generative cleavage to the one hypothesized, encouraging the researchers to re-examine their hypothesis. In the lower right-hand box, neither a generative cleavage nor at least one of the criteria for change is identified. In the top right-hand box a generative cleavage is identified but, again, at least one of the criteria for change is absent.

The Critical Juncture Grid

A framework within which to analyze critical junctures is of vital importance; in its absence, arguments as to what is, and what is not, a critical juncture are questionable. The objective in setting out the framework is to allow researchers to systemize their approach to examining potential critical junctures. This addresses the uncertainties regarding critical junctures not answered by earlier approaches. The remoulded critical junctures approach adds a tool to the historical institutional toolkit, allowing for a more coherent researching and understanding of past events. With this in mind we turn to an empirical example.

Case Study: Proposed Critical Juncture—Ireland 1987

In 1987 the Irish economy was in serious difficulty. The government, desperately seeking a solution, turned to politicized industrial relations at the national level. This witnessed a change in the ICTU's influence over public policy, with its recognition by the government as a “social partner.” With this development, the “union leaders secured access to government they had never previously enjoyed” (MacSharry and White, 2001: 130). The question this case study seeks to answer is whether this change in the ICTU's influence over public policy constituted a critical juncture, or was it merely a case of incremental change?

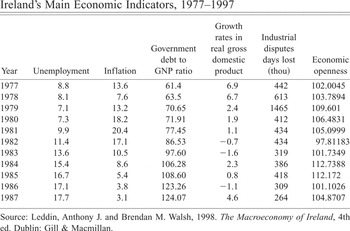

In this instance, the generative cleavage being tested for is a macro-economic crisis. However, what constitutes a macro-economic crisis is highly subjective in economics. Consequently, a range of various indicators will be utilized to enable us to reach a conclusion on the state of the economy. We will examine some of the main indicators of economic performance to see if they were at decade-long lows. In this regard, at least four of these indicators should have been at decade-long lows to indicate a macro-economic crisis. Account will also have to be taken of contemporaneous economic assessments by economists, newspapers, the central bank and international economic monitoring institutions. The opinions and actions of elected representatives will also have to be taken into consideration. If these diverse groups all considered the economy to have been in crisis, then there is a good chance that it was. Consequently, consideration of all this information should enable us to reach an informed decision on the state of the Irish economy in 1987.

In testing for change in the ICTU's influence over public policy, we are looking for significant, swift and encompassing change in different aspects of the relationship between the ICTU and government. This analysis will examine changes in the unions' policy preferences and relative power over public policy. The indicators employed are designed to measure the extent of what Baccaro (2002: 6) called “concertation” or “social partnership” as practiced in Ireland. They are related to, or derived from, the various dimensions upon which corporatism, corporatist bargaining and union strength can be measured (Hermansson, 1993; Nordby, 1994; Golden et al., 1999: 198), as well as the various dimensions that combine to define an industrial relations system (Archer, 1992: 377).

In this regard, swift is taken to refer to change occurring within 12 months of the proposed generative cleavage. We reject the notion of slow incremental change as we are seeking radical change. Encompassing requires that the change impacts upon at least 75 per cent of those with an interest in that change, in this case the membership of Irish trade unions. However, the criteria for significant change shall be particular to each of the observable factors utilized here. These factors will encompass many aspects of the relationship between the unions and government.

If the ICTU's rate of meetings with the prime minister increased by over 50 per cent within 12 months of the generative cleavage it is considered significant, while the significance of change in cabinet attitudes towards the ICTU shall be more subjective. If the ICTU's representation on government committees increased by over 50 per cent, it became involved in a tripartite agreement, and its membership increased by over 3 per cent, all within 12 months of the generative cleavage, then these factors would be considered significant. Measuring the significance of changes in the government's policy towards organized labour, and the level of ICTU policies incorporated into government policies, will be more subjective. Nevertheless, these changes will have to occur within 12 months of the generative cleavage, and have an impact upon most trade union members. Finally, change in the government's economic policies, as identified by organizations monitoring economic performance, and in the unions' influence over policy making, as identified by policy commentators, will be considered. This information should enable us to conclude whether there was a change in the ICTU's influence over public policy, and if this change was significant, swift and encompassing.

If there was a macro-economic generative cleavage and significant, swift and encompassing change in the ICTU's influence over public policy in 1987, then a critical juncture has been identified. Should any one of these conditions not be fulfilled, then we are not dealing with a critical juncture.

Testing for a Generative Cleavage

By 1987 the Irish economy, stagnating throughout the 1980s, was in serious difficulty, characterized by very high unemployment. The economic indicators for debt/GNP and unemployment had reached decade-long lows, while those for inflation, GDP growth, days lost to industrial disputes and economic openness, although not at decade-long lows, were far from impressive (Appendix A). When taken as a whole, the economic indicators pointed to an economy in trouble.

There was unanimity in both the domestic and foreign media concerning the economy. The Irish Times used the term “battered” to describe the economy in February 1987,1

The Irish Times, 3 February, 1987, p. 6.

Irish Independent, 4 February, 1987, p. 8.

The Economist, 24–30 January, 1987, pp. 53–55.

ibid.

The Irish Times, 12 February, 1987.

Irish Independent, 17 February, 1987.

The Economist Intelligence Unit, ‘Ireland: Country Profile 1991–92. (1992), p. 6.

Irish economists, concerned with the economy, delivered severe criticisms of policy and performance. Kennedy and Conniffe (1986: 288) observed that “it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that Irish economic performance has been the least impressive in Western Europe.” The Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) agreed that Irish economic performance had been appalling throughout the first half of the 1980s. Bradley and Fitzgerald (1989: iii) pointed out that from 1980 to 1987, growth averaged only 0.5 per cent per year, while the national debt doubled to over £23 billion, 40 per cent of which was sourced abroad. Unemployment, which had risen rapidly during the 1980s, peaked at a historic high of 17.7 per cent in 1987, with a total of 254,526 people out of work (Daly, 1994: 122). Ireland had reached the unenviable position of topping the European unemployment league.8

The Irish Press, 15 February, 1987.

The economy was looked upon with pessimism by the Central Bank. Its quarterly economic reports foresaw no immediate prospect for an improvement in either growth or employment.9

The Central Bank of Ireland, Quarterly Bulletin, Summer 1987, p. 7.

The Irish Times., 2 February, 1987.

ibid., 12 February, 1987.

According to the OECD (1987: 11–15), between 1979 and 1987 Irish economic performance had been dire: slow growth, rapidly deteriorating public finances, stagnation of per capita disposable income, huge balance of payments deficits, industrial relations turmoil and a large drop-off in domestic demand. As the OECD (1987: 77) put it, “by the mid-1980s a number of acute imbalances confronted the Irish economy.” These imbalances were also making the business community extremely worried. Leading businessman Tony O'Reilly warned of the dangers of IMF involvement, and of the loss of Irish economic sovereignty, if the economic crisis was not dealt with.12

Irish Independent, 14 February, 1987, p. 8.

In this context of economic despair, the government sought to build support among the economic and social interests for a national recovery strategy. In 1986 a National Economic and Social Council (NESC) report, A Strategy for Development 1986–1990, predicted that existing government policies would lead to further emigration, deterioration of the public finances and reduced flexibility for policy makers. The report emphasized the necessity of a national plan to tackle the public expenditure crisis. At the time, politicians of all political hues were coming to the same view. They all realized that something had to be done to improve the situation. Prime Minister Garrett FitzGerald acknowledged that “the national debt and interest payments were rising faster than national income, and constituted a vicious circle.”13

The Irish Times, 11 February 1987, p. 10.

ibid., 3 February, 1987.

ibid., 4 February, 1987.

The Times, 7 February, 1987.

The Irish Times, 2 February, 1987.

Testing for Significant, Swift and Encompassing Change

In 1987, the ICTU's access to the prime minister underwent dramatic transformation. In the years prior to 1987, the trade unions had met with Prime Minister Garrett FitzGerald on only a few occasions, and those encounters had generally been unproductive (FitzGerald, 1991: 454). However, after winning the general election of February 1987 the new prime minister, Charles Haughey, met with the ICTU on four occasions that year. Whereas the previous Fine Gael-Labour coalition government had been less than convinced of the merits of national tripartite agreements (Redmond, 1985), Fianna Fáil, even prior to the election, had embarked on a strategy of wooing the unions. It sought to involve them in policy discussions, as it regarded this as vital for imposing fiscal discipline. Most of the meetings between the prime minister and the ICTU were concerned with the government's plans for economic recovery, and how the union movement could contribute to this in a manner that was mutually beneficial to both them and the economy.18

ibid., 1987 and 1988.

The Fianna Fáil government adamantly supported a centralized pay agreement on account of its perceived benefits to the economy in terms of industrial peace, and the trade unions' commitment to support a series of painful, but necessary, spending cuts.19

ibid., 10 October, 1987.

The PNR was to see the reintegration of the union movement into the public-policy-making process. Three joint government-ICTU working parties, on employment and development measures, taxation and social policy, were set up as a result of the PNR.20

Annual Report, Irish Congress of Trade Unions, 1988.

ibid., 1988.

ibid.,

The level of union policies incorporated into the government's policies towards organized labour changed in 1987.23

Dáil Eireann, Vol. 374, 20 October, 1987.

ibid., Vol. 368, 3 July, 1986.

Budget, March, 1987.

ibid., 1988, 1989, 1990.

Dáil Eireann, Vol. 374, 20 October, 1987.

The social partnership shifted the Irish political economy from a British towards a European mode of consensus between social partners. “These arrangements re-established a reciprocal relationship between Congress [ICTU], the government, and employers on a much stronger institutional footing than heretofore” (Girvin, 1994: 130). From 1987 onwards the ICTU was to play a central role in the formulation of government economic and social policies, initially through the PNR, and subsequently through the central agreements that followed it. These tripartite agreements emphasized macro-economic stability, greater equity in the tax system and enhanced social justice. “In the decade after 1987, interest group activity in Ireland attained centre stage, with the tripartite agreements of the 1990s cementing social partnership” (Murphy, 1999: 291). These agreements showed how closely the union movement had become involved in policy making. “Ireland's social partnership approach [was] one of the most significant developments in public policy in the European Union” (NESF, 1997: 9).

The steady decline in the level of Irish trade union membership was also arrested in 1987/88. Rising unemployment and deepening recession had seen the unions suffer their most serious fall in membership since the Second World War (Roche, 1994b: 133). In 1987 union membership fell by 14,100, or 2.8 per cent (Roche, 1994a: 61). This left 468,600 trade unionists in the Republic of Ireland, a decrease of 76,600, or more than 14 per cent, since 1980. However, in 1988 trade union membership increased for the first time since 1980, reaching 470,500 (Roche and Larragy, 1989). Although an increase of only 0.4 per cent, this marked the beginning of a turnaround for the union movement. Over the following years the ICTU's membership grew substantially, reaching over 700,000 by late 2005.

In summation, the years leading to 1987 saw the Irish economy sinking deeper into recession. By 1987, continuation with the economic policies employed throughout the early 1980s was no longer viable. The view that the economy was in crisis was unanimously shared by the national media, political and economic commentators, the central bank, domestic and international organizations monitoring economic performance, and elected representatives.

In an effort to resolve the economic problems, the Irish political establishment opted for an inclusive and consensual approach. The general election of early 1987 saw a new Fianna Fáil administration come to power, determined to right the economy. This administration employed a new approach towards the trade unions that was to ultimately see the union movement involved in policy consultation with the reinstitution of centralized bargaining. Consequently, the ICTU's access to the Taoiseach, representation on government committees, government economic and industrial relations policies, the trade unions' influence on government policies, ministerial attitudes, and the overall level of trade union membership, all changed in the unions' favour, with government policies in particular coming to reflect those advocated by the unions. Most of these factors underwent significant and swift change, and the fact that they impacted upon the ICTU made them encompassing, as that body represented over 95 per cent of all Irish trade unionists.

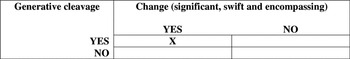

This brief case study shows that there was a significant, swift and encompassing change in the ICTU's influence over public policy in 1987, at a time when the country's economy was in crisis. This change in the ICTU's influence over public policy constituted a critical juncture. The occurrence of this critical juncture closed off a range of alternative paths that could have been chosen by the actors in the time preceding it.

Critical Juncture Grid—Ireland 1987

Conclusion

Historical institutionalism explores the conditions under which institutions evolve. The approach has developed rapidly over the past decade with the adoption of new techniques, becoming more dynamic, seeking to break away from focusing either on institutional reproduction or institutional change. A variety of mechanisms have been introduced to examine the subtle, yet significant, changes that occur within institutions. Yet some of the earlier concepts used for examining change, which are now falling from favour, were underspecified. One of these was the concept of critical junctures, a concept vital to our understanding of the starting points of analysis, thus solving the infinite regress problem.

In political science, few tools exist with which to make sense of institutional change (Thelen, 2003: 234). Katznelson (2003: 283) points to this deficiency, arguing that scholarship has yet to move purposefully in this direction. Into this desolate environment any new or revised instruments should be welcomed. This paper sought to improve on the critical junctures approach. The remoulded approach, as set out and tested above, provides a clearer means of examining change. In the case study of change in the ICTU's influence over public policy, in 1987, criteria are set out to enable us to see if the change constituted a critical juncture. The remoulded critical junctures approach possesses clarity, and a focus on context, that was previously lacking. With this approach it is easy to see what is a critical juncture, and why, reducing uncertainty surrounding the concept. The approach identifies what Aminzade (1992: 463) called the “key choice points.” The remoulded approach is applicable to any research concerned with change, raising the prospect of more wide-ranging research using the approach.

It is important that analysts become clearer as to the meaning of critical junctures. If the concept continues to be used loosely, the study of watershed events will probably amount to nothing more than a pointing to events that appear important. This article provides political scientists with conceptual and methodological tools for avoiding this error.

This addition to our body of theory provides greater leverage for analyzing the particular aspect of social reality encapsulated by critical junctures. This conforms to the need to place politics within context, within time (Pierson, 2004: 178). It can help political scientists think more clearly about the role of time and history in social analysis. This offers exciting opportunities for correcting common mistakes and silences in contemporary social science. It will enable us to strike a more effective and satisfying balance between explaining the general and comprehending the specific.

Appendix A