Risk is endemic to the political arena. Issues are controversial, power is wielded and diminished, and emotions are high. Who decides to wade into this morass or avoid it altogether is the subject of much study. Beyond socialization, there is evidence that individual traits influence how and when people participate politically (Schreiber et al., Reference Schreiber, Fonzo, Simmons, Dawes, Flagan, Fowler and Paulus2013). We contribute to this growing body of evidence by exploring how risk tolerance and its relation to political engagement may be biologically instantiated in sensory systems. Specifically, we investigate the connections between genetic and self-reported bitter taste reception, its connection to risk tolerance, and both of their associations with political orientations. We also consider the role of gender in the relationship between bitter taste reception, risk tolerance, and political orientations. Building these connections can help us better understand how individual dispositions and genetic variation could influence how people approach their social environments and how the social environment (e.g., contentious political arenas) may activate these dispositions to shape attitudes and behaviors.

Over the last decade, political scientists have increasingly been interested in the role of risk attitudes in a variety of sociopolitical behaviors, such as political participation (Kam, Reference Kam2012), candidate choice (Kam & Simas, Reference Kam and Simas2012), and participation in contentious politics (Tezcür, Reference Tezcür2016). Politics inherently involves elements of risk. The benefits of participation in politics are not always clear, and almost all political acts “cost” something in terms of time, psychological investment, or money. Voting might seem like a low-risk way to participate in politics, but even voting involves risk, as voters can never be exactly sure what candidates will do once in office (Kam & Simas, Reference Kam and Simas2012). Other work in the life sciences field has found that tolerance for risk has a genetic element, which is why humans vary in their tolerance for risk-taking (Karlsson Linnér et al., Reference Karlsson Linnér, Biroli, Kong, Meddens, Wedow, Fontana, Lebreton, Tino, Abdellaoui, Hammerschlag, Nivard, Okbay, Rietveld, Timshel, Trzaskowski, Vlaming, Zünd, Bao, Buzdugan, Caplin and Beauchamp2019). We focus on the gustatory system, as taste serves as a way for humans to gauge risk (Trivedi, Reference Trivedi2012; Vi & Obrist, Reference Vi and Obrist2018), and previous research has found correlations between risk-taking personalities and spicy foods (Byrnes & Hayes, Reference Byrnes and Hayes2016). Given that bitterness can be an indication of potentially toxic or poisonous foods (Bembich et al., Reference Bembich, Lanzara, Clarici, Demarini, Tepper, Gasparini and Grasso2010), yet many bitter-tasting foods, such as leafy greens, are healthy and advantageous for us to consume, we suggest that bitter taste may be correlated with risk-taking behavior.

Bridging these literatures, we investigate the connection between genetic and self-reported bitter taste reception, its connection to risk tolerance, and both of their associations with political behavior. We consider the role of gender because although women tend to vote at higher rates than men, gender and politics scholars have consistently found gender gaps in political participation (Burns et al., Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba2001; Wolak, Reference Wolak2020). Furthermore, there are gender differences in risk tolerance, with women being more risk averse than men (Cross et al., Reference Cross, Copping and Campbell2011; Flynn et al., Reference Flynn, Slovic and Mertz1994), and in bitter taste detection, with women being more sensitive to bitter-tasting substances (Bartoshuk et al., Reference Bartoshuk, Duffy and Miller1994; Duffy et al., Reference Duffy, Davidson, Kidd, Kidd, Speed, Pakstis, Snyder and Bartoshuk2004). We suggest that connections between bitter taste sensitivity and risk assessment strategies may shed light on biologically instantiated gender differences when it comes to risk tolerance in the political domain.

Although some of our findings are mixed across our three samples, we find strong evidence that self-reported preference for bitter-tasting foods is associated with higher levels of risk tolerance. Bitter taste preferences are also associated with higher levels of political participation, particularly participatory activities that involve social risk. We found mixed evidence that the relationship between bitter taste and risk or between bitter taste and political participation is conditional on sex or gender identity. Furthermore, we found no evidence that detection of N-Propylthiouracil (PROP) is related to risk or political participation.Footnote 1

Taste preferences and social behaviors

Though there is evidence of a connection between olfaction and political orientation (Friesen et al., Reference Friesen, Gruszczynski, Smith and Alford2020; McDermott et al., Reference McDermott, Tingley and Hatemi2014), very few political scientists have explored the sensory area of taste. Our senses of smell and taste chemically identify substances as either appetitive or dangerous, and taste distinguishes between sweet, salty, bitter, sour, and umami/savory (Bachmanov & Beauchamp, Reference Bachmanov and Beauchamp2007; Higgs et al., Reference Higgs, Cooper, Lee and Harris2015). Present-day differences in bitter taste manifest in variations in consumption of substances, such as coffee, beer, red wine, leafy greens, and dark chocolate, but the evolutionary development of these responses is related to the universality of bitterness indicating possible “toxic foods” or poison (Bembich et al., Reference Bembich, Lanzara, Clarici, Demarini, Tepper, Gasparini and Grasso2010; Higgs et al., Reference Higgs, Cooper, Lee and Harris2015). Yet, some leafy green vegetables that are obviously healthy are bitter tasting, so “it would be most adaptive for us to be wary but not entirely repelled by bitter substances” (Herz, Reference Herz2008, p. 187).

As individuals age and are exposed to bitter, nontoxic food and drink, they can “acquire taste.” Often, this occurs when we also use our olfactory sense (smell) in consuming these flavors or when there are social influences on this consumption (Higgs et al., Reference Higgs, Cooper, Lee and Harris2015, p. 211; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Nagai, Nakagawa and Beauchamp2003). It is important to note that many types of tastes may be acquired based on one’s socioeconomic status (e.g., wine, craft beers, leafy greens, nonlocal foods), but large genetic studies have revealed that coffee, tea, and alcohol consumption habits are related to the genetic variant associated with bitter taste (Ong et al., Reference Ong, Hwang, Zhong, An, Gharahkhani, Breslin, Wright, Lawlor, Whitfield, MacGregor and Martin2018). This helps demonstrate that even with this ability to adapt our bitter taste preferences, individual variation persists (Meier et al., Reference Meier, Moeller, Riemer-Peltz and Robinson2012; Ong et al., Reference Ong, Hwang, Zhong, An, Gharahkhani, Breslin, Wright, Lawlor, Whitfield, MacGregor and Martin2018; Sagioglou & Greitemeyer, Reference Sagioglou and Greitemeyer2016). Adjusting one’s food preferences for nutritional or social reasons also could be adaptive and connected to other types of behaviors (Sagioglou & Greitemeyer, Reference Sagioglou and Greitemeyer2016).

Psychologists have looked at the association between bitter taste preferences and some social behaviors. Sagioglou and Greitemeyer (Reference Sagioglou and Greitemeyer2014) conducted an experiment in which participants consumed either a bitter or a control beverage and were asked to provide behavioral responses to conflict situations that were presented in writing or asked to rate their interaction with another individual. Those who consumed the bitter beverages were more likely to provide hostile responses and ratings than the control group. Combining this finding with the extant research on the connection between prosocial behavior and enjoying sweet-tasting foods (Meier et al., Reference Meier, Moeller, Riemer-Peltz and Robinson2012), Sagioglou and Greitemeyer (Reference Sagioglou and Greitemeyer2016) posited that consistent exposure to bitter foods may create a “chronic” trait of personality hostility. Using two samples of American adults, they found that self-rated assessment of bitter foods corresponded with the antisocial indices of Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy, even when controlling for salty, sweet, and sour taste preferences.

There is evidence that differences in bitter taste responses are genetically based. Of particular interest is sensitivity to 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP) and phenylthiocarbamide (PTC), related chemicals that taste bitter to tasters and are flavorless to nontasters (Bartoshuk et al., Reference Bartoshuk, Duffy and Miller1994). Tasters and nontasters display different patterns of brain activity when exposed to PROP, with heightened activity in the prefrontal cortex among tasters and no change in activity among nontasters (Bembich et al., Reference Bembich, Lanzara, Clarici, Demarini, Tepper, Gasparini and Grasso2010). Genetic variants in bitter taste sensitivity have several behavioral effects, especially regarding food preferences and dietary behaviors (Tepper, Reference Tepper2008). Among adults, greater perceptions of caffeine bitterness (from variants on chromosome 12) are associated with elevated coffee intake and lower tea intake, whereas greater perceptions of quinine bitterness (from variants on chromosome 12) and sensitivity to PROP (from variants in the TAS2R38 gene on chromosome 7) are associated with less coffee and alcohol consumption (Ong et al., Reference Ong, Hwang, Zhong, An, Gharahkhani, Breslin, Wright, Lawlor, Whitfield, MacGregor and Martin2018). In an adolescent and young adult twin sample (mean age 16.2), Hwang and colleagues (Reference Hwang, Breslin, Reed, Zhu, Martin and Wright2016) found a genetic association underlying the inverse relationship between bitter and sweet taste preferences that was partly dependent on variation in PROP sensitivity. Among children, variation in TAS2R38 is also associated with bitter taste sensitivity, lower thresholds for certain sweet tastes (e.g., sucrose), and more sugar consumption among 7- to 14-year-olds (Joseph et al., Reference Joseph, Reed and Mennella2016; see also Mennella et al., Reference Mennella and Pepino2005, for 5- to 10-year-olds), as well as lower consumption of bitter vegetables and American cheese among 4- to 5-year-olds (Keller et al., Reference Keller, Steinmann, Nurse and Tepper2002).

Bitter taste, risk assessment, and gender

Importantly for the present research, several of the studies exploring bitter taste found that the results are moderated by gender, such that women and girls, on average compared with men and boys, are more sensitive to PROP and to bitter tastes and prefer sweeter tastes. However, this may be partly because a higher proportion of women are super-tasters who have a greater density of fungiform papillae (Bartoshuk et al., Reference Bartoshuk, Duffy and Miller1994; Duffy et al., Reference Duffy, Davidson, Kidd, Kidd, Speed, Pakstis, Snyder and Bartoshuk2004), rather than solely because of PROP sensitivity (see also Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Bartoshuk, Kidd and Duffy2008). Cultural factors likely play an important role in how the relationship between gender, genetic predispositions, and food behaviors develops. For example, Keller and colleagues (Reference Keller, Steinmann, Nurse and Tepper2002) suggested that restrictive food strategies, which have gendered effects, may affect how PROP sensitivity translates into eating habits. Based on this literature, we expect PROP sensitivity to be associated with lower bitter taste preferences and greater sweet taste preferences, and that this relationship may be stronger among women than among men.

Individual differences in bitter taste preferences also have been linked to emotions (Macht & Mueller, Reference Macht and Mueller2007), but most links to personality have involved tasting sweet substances and prosocial behaviors (Meier et al., Reference Meier, Moeller, Riemer-Peltz and Robinson2012). Bitter taste exposure is associated with detecting emotions in faces (Schienle et al., Reference Schienle, Giraldo, Spiegl and Schwab2017) and influencing one’s personal mood (Dubovski et al., Reference Dubovski, Ert and Niv2017), suggesting that these taste preferences continue to moderate social behaviors and perceptions of others. Although research into the properties of bitter taste perception itself goes back decades, links to the psychological and behavioral correlates of bitter taste sensitivity outside the domain of eating are very recent, across disciplines (though see Schreiber et al., Reference Schreiber, Fonzo, Simmons, Dawes, Flagan, Fowler and Paulus2013, for a discussion of neural correlates of these factors separately—sensory detection, risk-taking, and political orientations). Thus, it is quite timely to launch a political behavior study to contribute to the conversation of psychologists, geneticists, and other scholars seeking to understand the relationships between sensory experience and social behaviors. Given that interest and participation in politics are also linked to personality traits (Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Huber, Doherty, Dowling, Raso and Ha2011; Mondak et al., Reference Mondak, Hibbing, Canache, Seligson and Anderson2010) and heritable factors (Dawes et al., Reference Dawes, Cesarini, Fowler, Johannesson, Magnusson and Oskarsson2014; Fowler et al., Reference Fowler, Baker and Dawes2008; Klemmensen et al., Reference Klemmensen, Hatemi, Hobolt, Petersen, Skytthe and Nørgaard2012), it is worth exploring whether there are interconnections between interest and participation in politics with gustatory systems.

Though we are testing political participation, there is some evidence of a relationship between bitter taste sensitivity and political ideology. Ruisch et al. (Reference Ruisch, Anderson, Inbar and Pizarro2021) found that sensitivity to PROP and PTC, both measures of bitter taste sensitivity, was correlated with ideology, and in particular, social conservatism. This relationship was mediated by sensitivity to disgust. Furthermore, the authors used a more direct physiological measure of taste sensitivity—the density of fungiform papillae on participants’ tongues—to test the same hypothesis. Greater density of fungiform papillae is an indicator of higher taste sensitivity and was also associated with more conservative ideology. Hibbing et al. (Reference Hibbing, Smith and Alford2013) also reported unpublished findings from their lab connecting PTC detection and conservative ideology.

We are interested in understanding how bitter taste preferences might relate to political behavior, apart from ideology or the pathway through disgust. Instead, we suggest that interest in bitter-tasting substances might be related to risk-taking behavior. If bitter taste once signified poison but also could involve consumption of leafy greens, those who are able to tolerate or enjoy a bitter taste could be rewarded by healthy nutrients—or punished with sickness and possible death (in the case of actual poisonous substances). Gender differences in both risk tolerance and taste detection and preferences lead us to consider a possible connection between these three domains: bitter taste, risk-taking, and gender.

For example, extant research has shown that women are more likely to be super-tasters, thus more sensitive to bitter substances, and more likely to prefer sweeter tastes (Herz, Reference Herz2008). Psychology research demonstrates that there are significant gender differences in risk assessment, with women being more risk averse than men across various types of domains (Bord & O’Connor, Reference Bord and O’Connor1997; Cross et al., Reference Cross, Copping and Campbell2011; Finucane et al., Reference Finucane, Slovic, Mertz, Flynn and Satterfield2000; Flynn et al., Reference Flynn, Slovic and Mertz1994; Garbarino & Strahilevitz, Reference Garbarino and Strahilevitz2004; Nelson, Reference Nelson2015; Waldron et al., Reference Waldron, McCloskey and Earle2005). Though our study is correlational and cannot determine causal order, we base our hypotheses on the extant literature and evolutionary theory to suggest that perhaps bitter taste tolerance co-develops with risk preferences, and this concurrence might explain some of the biological pathways of gender differences in risk behaviors.

Politics is inherently risky—from running for office to participation beyond simply voting—and individuals who demonstrate a low tolerance for general risk-taking are less likely to engage politically (Kam, Reference Kam2012). Whether the result of socialized norms or evolved sex roles, women, on average, tend to be more conflict and risk avoidant than men, so they eschew politics when it is competitive but may engage when the political sphere is perceived as consensual (Kam, Reference Kam2012; Mutz, Reference Mutz2006; Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Holman, Diekman and McAndrew2016; Wolak & McDevitt, Reference Wolak and McDevitt2011). In looking at the combination of personality traits, risk tolerance, and conflict avoidance, recent scholarship has found that what engages men in politics disengages women (Djupe et al., Reference Djupe, Friesen and Sokhey2017). Women may be more interested in channeling their time and talents into spaces of group belonging and agreement (e.g., religious institutions) than areas of competition and conflict like politics (Friesen & Djupe, Reference Friesen and Djupe2017).

The gendered nature of risk aversion and political engagement may be rooted in evolved responses toward sexual selection and social roles (Sweet-Cushman, Reference Sweet-Cushman2016). From this perspective, competition among males for mates partially explains why individuals choose to engage in risky behavior. Men tended to benefit more from engaging in risk-seeking behavior than women in terms of reproductive strategies. Using this logic, Sweet-Cushman (Reference Sweet-Cushman2016) proposed an evolutionary origin for candidate emergence. She posited that because women and men have faced different evolutionary pressures, they have developed different cognitive mechanisms for risk assessment. These differing cognitive strategies can impact the way that men and women evaluate risk in the political domain, and more specifically, in determining whether to run for office. Again, we suggest that perhaps bitter taste sensitivity and risk assessment strategies co-developed and may shed light on how biologically instantiated gender differences in risk seeking in the political domain are. Because of the socially constructed nature of gender, we extend our analyses beyond sex assigned at birth to see how continuous measures of masculine and feminine gender identity relate to risk aversion and political engagement.

Hypotheses

Given that it is biologically most beneficial for humans to be wary of bitter-tasting substances, but not entirely avoidant of them, we expect the following:

H1: Tasters (those who can detect PROP) are expected to be more risk avoidant than nontasters in everyday life. Among tasters, high tasters (those who experience the bitter flavor of PROP more intensely) are expected to be more risk avoidant than low or medium tasters. Similarly, we predict that the more an individual likes bitter tastes, as measured by their affinity for bitter foods, the higher they will score or risk-seeking/taking measures. These hypotheses are not specific to politics but capture a broader behavioral expectation, and we assume both sensitivity and preference for bitter tastes will be predictive of risk tolerance, even when included in the same model.

We also expect that bitter taste, given its association with risk tolerance, will be associated with risk in the political domain:

H2: Taster status, bitter taste sensitivity, and bitter food taste preference are expected to be associated with political behaviors such that tasters, those with greater bitter taste sensitivity, and those with lower bitter taste preferences will be less likely to participate in political activities that may involve social risk, including political discussions, attending a rally, and posting political content online.

Furthermore, we know from the taste literature that women have higher levels of bitter taste sensitivity, and scholars have demonstrated that there are significant gender differences in risk assessment, with women having less tolerance for risk than men. Therefore, we want to explore the interaction of gender and bitter taste preference on political participation.

H3: Women are not expected to be more likely to be tasters than men. However, women are expected to have greater bitter taste sensitivity among tasters and to express a lower preference for bitter flavors. We expect that this influences the willingness to participate in political activities that involve social risk.

Finally, in addition to testing the interaction of gender and bitter taste preferences on political participation, we also include a continuous measure of gender identity (Bittner & Goodyear-Grant, Reference Bittner and Goodyear-Grant2017; Gidengil & Stolle, Reference Gidengil and Stolle2021) to explore how masculine and feminine gender identity relate to bitter taste sensitivity and political participation. These continuous measures of masculinity and femininity capture variation beyond conventional gender identity measures and allow for potential orthogonality between these identities.

H4: Those who identify as more feminine are expected to have greater bitter taste sensitivity among tasters and to express a lower preference for bitter flavors than those who identify as more masculine. We expect that this influences the willingness to participate in political activities that involve social risk.

Methods

Samples

For our online sample, we contracted with Bovitz Inc., in Encino, California, to use its proprietary survey panel Forthright to recruit a sample of adults living in the United States (N = 1,043) between October 21 and 28, 2020. Forthright recruits participants in its panel through both internet- and address-based sampling methods. Participants for this study were randomly selected within the Forthright panel and invited through email invitations or SMS text messages for those who opted in with their mobile phone numbers. Forthright accounts for variance in response rates by oversampling certain demographic groups to ensure a nationally representative sample. Because of a quota logic error by one of the authors, we ended up sending the survey to 1,700 respondents to get the 1,043 complete responses.

Our second and third samples were recruited from the student population at the University of Illinois in 2019 (N = 521 for survey measures; N = 369 for PROP measures in lab; 70% lab completion rate) and 2020 (N = 374 for survey measures; 75% or 282 opted in to PROP measures by mail due to COVID-19, of which 35% or 98 completed PROP measures by mail). This sample was younger than the general population, which can be preferable as the ability to detect bitter taste does decline with age (Cowart et al., Reference Cowart, Yokomukai and Beauchamp1994). Across the three samples, respondents who did not complete the food preferences battery were excluded from the analyses. To address missing values on covariates, we employed this guideline: if 10% or less of the values on the covariate were missing, we recoded the missing values to the overall mean (Gerber & Green, Reference Gerber and Green2012).

Pilot data and power analysis

A pilot study provided us with a preliminary estimate of effect sizes for our hypothesized relationships to assist with power analysis alongside the broader literature (for limitations of relying on pilot studies alone, see Albers & Läkens, Reference Albers and Läkens2018; Kraemer et al., Reference Kraemer, Mintz, Noda, Tinklenberg and Yesavage2006) and an opportunity to test our analytical strategy in order to uncover any unforeseen challenges. The data were collected from a sample of undergraduates registered in political science courses at the University of Illinois in 2019 (Study 2). In the first wave of data collection, students completed the taste inventory and risk-taking battery. We found that bitter taste preferences predicted general risk seeking with and without controls for gender identity and other taste preferences (standardized betas between 0.17 and 0.19).

We conducted several a priori power analyses using G*Power software (Faul et al., Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Lang and Buchner2007) to examine the statistical tests proposed in the analysis section. All power analyses assumed .80 power with an alpha of 0.05. Previous explorations between bitter taste preferences and social traits and behaviors have resulted in small effect sizes—typically around .10 or .15 for the taste list preference (Sagioglou & Greitemeyer, Reference Sagioglou and Greitemeyer2016). Therefore, we proposed the nationally representative online survey sample of 1,000 to achieve 90% power.

Materials, measures, and procedures

In all samples, participants were asked to rate their food preferences from lists of foods developed by other scholars (Meier et al., Reference Meier, Moeller, Riemer-Peltz and Robinson2012; Sagioglou & Greitemeyer, Reference Sagioglou and Greitemeyer2016), including sweet (candy, honey, ice cream, maple syrup, pears); sour (cranberries, lemons, limes, sour cream, and vinegar); bitter (cabbage, coffee, grapefruit, radishes, rye bread, tea, and tonic water); salty (bacon, beef jerky, green olives, pretzels, salty peanuts, and soy sauce); and spicy (cayenne pepper, chilis, curry, hot salsa, jalapeno peppers, and Tabasco sauce).

Because of possible socialization and socioeconomic differences in food preference development, we also used a non-food-related tasting behavior component common in bitter taste studies in Studies 2 and 3. To accomplish this, we relied on N-Propylthiouracil (PROP) taster strips (manufactured by Bartovation). Participants were asked to rate whether they detected the substance and how strongly and negatively they rated the taste (Hwang et al., Reference Hwang, Breslin, Reed, Zhu, Martin and Wright2016). The taster strip method is strongly correlated with other methods for measuring PROP sensitivity (Bartoshuk et al., Reference Bartoshuk, Duffy and Miller1994), such as PROP ratio tests that rely on drinking solutions with progressively higher concentrations of PROP. In Studies 2 and 3, participants each rated one control paper strip (without PROP) and one treatment strip (with PROP). PROP strips were administered in a lab environment in Study 2 in the spring of 2019. Participants were asked not to eat, drink, or smoke for one hour before coming to the lab and were given a bottle of water with which to rinse their mouth before self-administering each strip and rating it on flavor intensity, flavor profile, and pleasantness. Participants all completed the control strip before the PROP strip.

Study 3 was administered in the fall of 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, in-person administration was not possible. Participants were asked to provide a mailing address to which the taster strips could be sent. Participants who provided a mailing address were mailed the strips in separately sealed plastic bags and an instruction sheet with a URL for the survey to complete alongside the strips. At the beginning of the survey, they were reminded that they should not have anything to eat, drink, or smoke for one hour before starting the survey. The survey followed procedures similar to those used in the lab in 2019 for self-administration of the control and PROP strips (with the control strip administered first).

All participants completed survey items, which included a seven-item risk-taking battery (e.g., “In general, how easy or difficult is it for you to accept taking risks?”; see Kam, Reference Kam2012), a 40-item multiple domains of risk measure (Weber et al., Reference Weber, Blais and Betz2002), attitudes about and experiences with COVID-19, and several demographic variables (age, gender, education). All risk batteries were coded so that higher values indicate greater risk seeking. Our main outcome of interest is political participation, which was measured using eight items adapted from Kam (Reference Kam2012). These items asked respondents to look to the future and assess their likelihood of participating in a series of acts, including rallies, marches, demonstrations, attending a local government or school board meeting, signing an e-petition, signing a paper petition, donating money to a political/social organization, attending a meeting on political/social issues, inviting someone else to attend such a meeting, distributing flyers to support a political/social organization, and posting about politics on social media. Response categories to all items other than voting were measured on a 5-point scale from “extremely likely” to “not at all likely.”

Age was measured with an open-ended question, and income was asked across a range of seven categories of income brackets. We also extended sex/gender measures beyond the binary male/female to include a self-placement on two dimensions—continuums from 1 to 7 on masculinity and 1 to 7 femininity. Following both past and recent research on the problems with standard conceptualizations and operationalizations of gender, we used these scales so as to not treat gender as a dichotomy and to allow for distinctions in identity strength (Bem, Reference Bem1976; Bittner & Goodyear-Grant, Reference Bittner and Goodyear-Grant2017; Gidengil & Stolle, Reference Gidengil and Stolle2021; Hatemi et al., Reference Hatemi, McDermott, Bailey and Martin2012; McDermott, Reference McDermott2016; Wangerud et al., Reference Wängerud, Solevid and Dejerf-Pierre2019). Following Wangerud et al. (Reference Wängerud, Solevid and Dejerf-Pierre2019), we also included a categorical measure of gender identity as well as sex assigned at birth to help us explore interactions between the categorical measures and the masculinity/femininity scales.

Deviations from pre-analysis plan

In our registered report, we suggested doing a series of exploratory analyses between bitter taste, Big Five personality traits, Wilson-Patterson issue attitudes, religiosity, and other measures. Because of space constraints and in the interest of focusing on our already complex set of results across multiple samples, we elected to save those exploratory efforts for a future pilot project. The 2019 student sample was collected in waves such that in the first wave, students rated their food taste preferences and completed some demographic variables. We used these data as our pilot sample for the registered report and to assist with power analysis. In a later wave with these same participants, the students were brought to a lab and tasted the PROP strips. Though this took place in 2019, we did not look at or analyze these data until our registered report was accepted by reviewers. This proved coincidentally fortuitous, as the COVID-19 pandemic swept across the United States just as we were set to collect the next two samples of data. Thus, our other deviation was that in the second student sample in 2020, we mailed the PROP strips for students to rate because the lab was closed due to the pandemic. Finally, we mistakenly included only 37 items of the 40-item risk battery in Study 1 (Weber et al., Reference Weber, Blais and Betz2002).

Study 1 (Adult Sample)

We first discuss descriptive statistics of the sample and scale reliabilities, followed by the models described in the preregistered analysis strategy. All significance tests are two-tailed. The central variables of interest in this study are bitter taste preferences, risk tolerance, sex, gender identity, and political participation. Our sample was 49.8% male and 50.2% female according to the sex assigned at birth measure. Among male respondents, 39.2% rated themselves at the highest end of the masculinity scale, and among female respondents, 37.9% rated themselves on the highest end of the femininity scale. All variables were recoded to range from 0 to 1 for ease of interpretation of the unstandardized coefficients.

To create a bitter taste preference scale, we averaged the bitter food items that participants rated into a composite score (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

= 0.55, Cronbach’s alpha = .72).Footnote

2 The bitter taste subscale had the lowest average score in terms of taste preference compared with the sweet (

$ \overline{x} $

= 0.55, Cronbach’s alpha = .72).Footnote

2 The bitter taste subscale had the lowest average score in terms of taste preference compared with the sweet (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

= 0.77), salty (

$ \overline{x} $

= 0.77), salty (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

= 0.69), and sour (

$ \overline{x} $

= 0.69), and sour (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

= 0.62) taste subscales. We conducted the same procedure to create risk tolerance scales (Kam, Reference Kam2012, scale:

$ \overline{x} $

= 0.62) taste subscales. We conducted the same procedure to create risk tolerance scales (Kam, Reference Kam2012, scale:

![]() $ \overline{x} $

= 0.49, Cronbach’s alpha = .72; Weber et al., Reference Weber, Blais and Betz2002, scale:

$ \overline{x} $

= 0.49, Cronbach’s alpha = .72; Weber et al., Reference Weber, Blais and Betz2002, scale:

![]() $ \overline{x} $

= 0.31, Cronbach’s alpha = .92) and a political participation index (

$ \overline{x} $

= 0.31, Cronbach’s alpha = .92) and a political participation index (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

= 0.35, Cronbach’s alpha = .91).Footnote

3 In terms of other demographic variables, our sample was 72.9% White and 27.1% non-White, had a mean age of 45.4, and 16.3% of respondents identified as Latinx. The median level of education is an associate’s degree. Full demographic information can be found in the Appendix in the supplementary material online.

$ \overline{x} $

= 0.35, Cronbach’s alpha = .91).Footnote

3 In terms of other demographic variables, our sample was 72.9% White and 27.1% non-White, had a mean age of 45.4, and 16.3% of respondents identified as Latinx. The median level of education is an associate’s degree. Full demographic information can be found in the Appendix in the supplementary material online.

Based on a two-sample t-test, we found no significant sex differences in bitter taste preference (p = .186) or political participation (p = .507). In terms of the continuous gender identity scales, there was no significant correlation between femininity and bitter taste preference (r = 0.03, p = .39). However, there was a significant positive correlation between bitter taste preference and masculine gender identity, though the effect size is small (r = 0.07, p = .03), providing some initial support to our expectations that masculinity is associated with a preference for bitter tastes.

Hypothesis 1

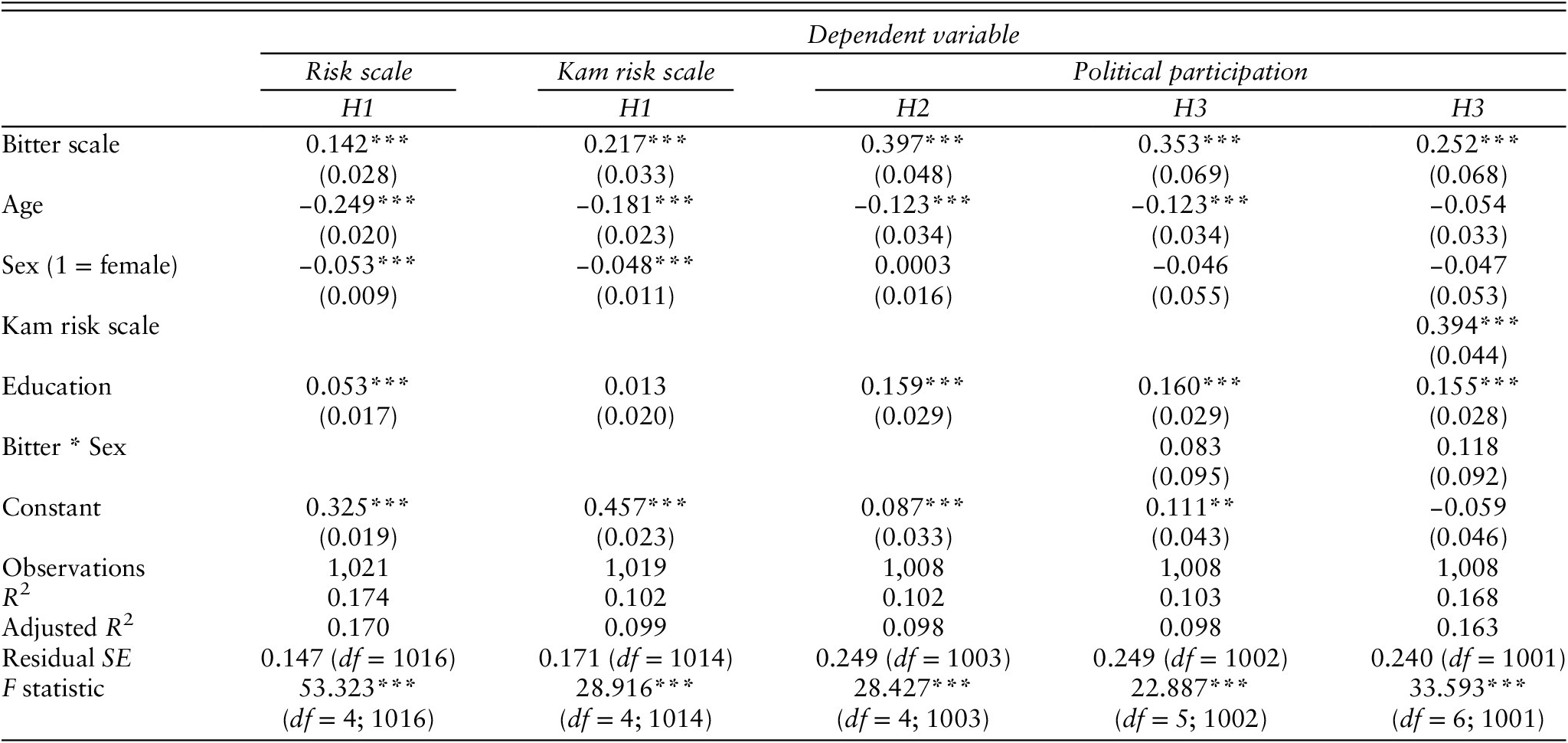

In H1, we predicted that bitter taste preference would be positively associated with risk tolerance. To test this hypothesis, we regressed risk tolerance on the bitter taste scale, controlling for age, binary sex, and education. We found strong support for H1. The bitter taste scale was positively associated with risk tolerance (p < .01). Full results are displayed in Table 1

Footnote

4 and summarized in Figure 1, demonstrating the positive relationship between bitter taste preference and risk tolerance. Comparatively, regression coefficients indicate that bitter taste had a stronger association with risk tolerance than education. With respect to the control variables, age and being a female respondent were negatively associated with risk tolerance, and education was positively associated with risk tolerance. This model explained a significant proportion of variance in risk tolerance (

![]() $ {R}^2 $

= .17, F = 53.3, p < .01).

$ {R}^2 $

= .17, F = 53.3, p < .01).

Table 1. Regression results (Forthright sample, 2020).

Note: Standard errors in parentheses. + p < .1; ** p < .05; *** p < .01.

Figure 1. Effect of bitter taste preference on risk (Forthright sample, 2020).

Hypothesis 2

H2 predicted that bitter taste preference would be associated with political activities that involve an element of risk, following Kam (Reference Kam2012). To test this hypothesis, we regressed the political participation scale on the bitter taste scale, again controlling for age, binary sex, and education. Full regression results can be found in Table 1. We found strong support for H2, as bitter taste was positively associated with political participation (p < .01). Regression coefficients indicate that bitter taste had a stronger association with political participation than education and age. With respect to the control variables, age was significantly negatively associated with participation, and education was significantly positively associated with participation. Given that the data were collected during a global pandemic, which arguably affected older individuals more severely, it may be unsurprising that political participation was lower for older Americans. This model explained a significant proportion of variance in political participation (

![]() $ {R}^2 $

= .1, F = 28.4, p < .01).

$ {R}^2 $

= .1, F = 28.4, p < .01).

Hypothesis 3

In H3, we predicted that women would express a lower preference for bitter flavors and that this preference would have an effect on willingness to participate in political activities that involve risk. To test the hypothesis, we regressed political participation on the bitter taste scale and an interaction between binary sex and the bitter taste scale. We controlled for age and education. As displayed in Table 1, we found no support for this hypothesis. The interaction between bitter taste preference and sex had no significant effect on political participation. In the second column, we included the Kam (Reference Kam2012) risk scale to determine whether bitter taste preferences were simply a proxy for risk in the relationship with participation, but in fact, bitter taste and risk were accounting for variance separately. The results of this hypothesis are summarized in Figure 2, which shows that the effect of bitter taste on political participation does not differ by binary sex. This model explained a significant proportion of variance in political participation (

![]() $ {R}^2 $

= .1, F = 22.9, p < .01).

$ {R}^2 $

= .1, F = 22.9, p < .01).

Figure 2. Effect of bitter taste preference on political participation by binary sex (Forthright sample, 2020).

We also conducted a mediation analysis to see whether bitter taste mediates the relationship between binary sex and political participation. The typical procedure for conducting a mediational analysis is a four-step method in which a series of linear regressions models are fitted to estimate the relationship between the independent and dependent variables controlling for the mediational variable (Baron & Kenny, Reference Baron and Kenny1986). We expected that bitter taste preference would attenuate the effect of female sex on political participation. Full mediation would occur if the effect of sex on political participation reduced to zero with the inclusion of bitter taste preference in the model. Partial mediation would occur if the effect were reduced. We followed this procedure and found that bitter taste preference did not mediate the relationship between binary sex and political participation. We also conducted a Sobel test and found no evidence of a mediation effect (p = .19).

Hypothesis 4

In our final hypothesis, we predicted that bitter taste preference would mediate the relationship between continuous measures of gender identity and political participation. We followed the same procedure that we followed to test H3 and found that bitter taste preference did not mediate the relationship between feminine gender identity and political participation. We also conducted a Sobel test and found no evidence of a mediation effect (p = .39).

Study 2 (Student Sample, Spring 2019)

As for Study 1, we first discuss descriptive statistics of the sample and scale reliabilities, followed by the models described in the preregistered analysis strategy. The food preference data in this sample were collected prior to preregistration and should be considered pilot data. The PROP data were collected after preregistration. All significance tests are two-tailed.

The central variables of interest in this study are bitter taste preferences, risk tolerance, categorical gender identity, continuous gender identity, and interest in politics; political participation was not available in this sample. Among respondents, 46.2% of the sample identified as male, 53.1% as female, and 0.8% as nonbinary (“What is your gender identity?”). When asked about their gender identity (“Finally, we would like to ask you a question about your gender identity. That is, how masculine or feminine you feel you are. Below you will find a continuum that goes from left to right. We would like you to place yourself somewhere along this scale: the far right of the scale reflects a person who feels they are 100% masculine, while the far left of the scale reflects a person who feels they are 100% feminine. Where would you place yourself on this continuum?”), among male respondents, 19.8% rated themselves as fully masculine, and among female respondents, 20.7% rated themselves as fully feminine.

To create a bitter food taste preference scale, we averaged the bitter taste items that participants rated into a composite score (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

= 0.53, Cronbach’s alpha = .68). The bitter taste subscale had the lowest average score in terms of taste preference compared with the sweet (

$ \overline{x} $

= 0.53, Cronbach’s alpha = .68). The bitter taste subscale had the lowest average score in terms of taste preference compared with the sweet (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

= 0.71), salty (

$ \overline{x} $

= 0.71), salty (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

= 0.63), and sour (

$ \overline{x} $

= 0.63), and sour (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

= 0.58) taste subscales. We conducted the same procedure to create risk tolerance scales (Kam, Reference Kam2012, scale:

$ \overline{x} $

= 0.58) taste subscales. We conducted the same procedure to create risk tolerance scales (Kam, Reference Kam2012, scale:

![]() $ \overline{x} $

= 0.49, Cronbach’s alpha = .56; Weber et al., Reference Weber, Blais and Betz2002, scale:

$ \overline{x} $

= 0.49, Cronbach’s alpha = .56; Weber et al., Reference Weber, Blais and Betz2002, scale:

![]() $ \overline{x} $

= 0.43, Cronbach’s alpha = .86) and a two-item measure of interest in politics in lieu of the political participation index (

$ \overline{x} $

= 0.43, Cronbach’s alpha = .86) and a two-item measure of interest in politics in lieu of the political participation index (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

= 0.35, Cronbach’s alpha = .56). For PROP tasting, 37.2% of the sample were nontasters (i.e., they categorized the intensity difference between the control and PROP strip as zero or less, or they characterized the taste of the PROP strip as not bitter). There was an average difference in the ratings of taste intensity between the PROP strip and the control strip of 0.17 (0.28 among tasters, the 62.8% of the sample who characterized the PROP strip as bitter and tasting stronger than control). Compared with men, women were significantly more likely to be tasters (men = 57.0%, women = 71.6%, p = .003), to have stronger difference ratings compared to control (men = 0.12, women = 0.23, p < .001), and to have stronger difference ratings when looking only at tasters (men = 0.22, women = 0.32, p < .001). PROP tasting was largely unrelated to bitter taste preference (r = 0.06 in full sample, p = .245; r = –0.03 among PROP tasters only, p = .637). In terms of other demographic variables, of those reporting race, our sample is 58.0% non-Hispanic White, 7.5% Black, 14.6% Asian, 1.0% other race, 8.5% multiracial, and 14.3% Hispanic or Latinx. The sample has a mean age of 20.0. Full demographic information can be found in the Appendix.

$ \overline{x} $

= 0.35, Cronbach’s alpha = .56). For PROP tasting, 37.2% of the sample were nontasters (i.e., they categorized the intensity difference between the control and PROP strip as zero or less, or they characterized the taste of the PROP strip as not bitter). There was an average difference in the ratings of taste intensity between the PROP strip and the control strip of 0.17 (0.28 among tasters, the 62.8% of the sample who characterized the PROP strip as bitter and tasting stronger than control). Compared with men, women were significantly more likely to be tasters (men = 57.0%, women = 71.6%, p = .003), to have stronger difference ratings compared to control (men = 0.12, women = 0.23, p < .001), and to have stronger difference ratings when looking only at tasters (men = 0.22, women = 0.32, p < .001). PROP tasting was largely unrelated to bitter taste preference (r = 0.06 in full sample, p = .245; r = –0.03 among PROP tasters only, p = .637). In terms of other demographic variables, of those reporting race, our sample is 58.0% non-Hispanic White, 7.5% Black, 14.6% Asian, 1.0% other race, 8.5% multiracial, and 14.3% Hispanic or Latinx. The sample has a mean age of 20.0. Full demographic information can be found in the Appendix.

Based on a two-sample t-test, we found no significant gender differences in bitter taste preference (women

![]() $ \overline{x} $

= 0.53, men

$ \overline{x} $

= 0.53, men

![]() $ \overline{x} $

= 0.52, p = .299), and that women in our sample were significantly more interested in politics than men (women

$ \overline{x} $

= 0.52, p = .299), and that women in our sample were significantly more interested in politics than men (women

![]() $ \overline{x} $

= 0.39, men

$ \overline{x} $

= 0.39, men

![]() $ \overline{x} $

= 0.31, p < .001). In terms of the continuous gender identity, there was no significant correlation with bitter taste preference (r = –0.02, p = .59).

$ \overline{x} $

= 0.31, p < .001). In terms of the continuous gender identity, there was no significant correlation with bitter taste preference (r = –0.02, p = .59).

Hypothesis 1

In H1, we predicted that bitter taste preference would be positively associated with risk tolerance and that PROP sensitivity would be negatively associated with risk tolerance. To test this hypothesis, we regressed risk tolerance on the bitter taste scale and PROP sensitivity. We controlled for age and gender identity (not for education, as the sample consists of college students). Again, we found strong support for H1. The bitter taste scale was positively associated with risk tolerance (p < .01). Full results are displayed in Table 2.Footnote

5 The effect size for bitter taste preferences on both risk measures was substantively similar (e.g., within one standard error) to the adult respondents in Sample 1. With respect to the control variables, identifying as a woman was negatively associated with risk tolerance across both measures, and older students were marginally less risk seeking on the Weber measure. This model explained a significant proportion of variance in risk tolerance (

![]() $ {R}^2 $

= .08, F = 10.8, p < .01).

$ {R}^2 $

= .08, F = 10.8, p < .01).

Table 2. Regression results for bitter taste preference (student sample, 2019).

Note: Standard errors in parentheses. + p < .1; ** p < .05; *** p < .01.

The results for PROP tasting (see Table 3) did not support H1, which predicted that PROP tasting would be associated with lower levels of risk-taking; there was no significant relationship between PROP tasting and either measure of risk. However, PROP tasting was significantly related with less risk seeking on the Weber social risk subscale (see Appendix).

Table 3. Regression results for PROP taste sensitivity (student sample, 2019).

Note: Standard errors in parentheses. + p < .1; ** p < .05; *** p < .01.

Hypothesis 2

H2 predicted that bitter taste preference would be associated with political activities that involve an element of risk, following Kam (Reference Kam2012), and that PROP sensitivity would have the opposite relationship. This sample did not have a measure of political participation, but we constructed a measure of interest in politics as a proxy. We controlled for age and gender identity. We found no relationship between interest in politics and either bitter taste preference or PROP taste ability among students (see Tables 2 and 3). As noted earlier, women were significantly more interested in politics than men.

Hypothesis 3

In H3, we made several predictions. First, we predicted that women were not more likely to be PROP tasters than men. This was disconfirmed, as 71.7% of women were tasters and 57.0% of men were tasters (p < .01). Second, we predicted that among men and women who are able to detect PROP, women would have greater bitter taste sensitivity. This was confirmed, as women tasters reported greater PROP sensitivity than men (men = 0.22, women = 0.32, p < .001). Third, we predicted that women would express a lower preference for bitter foods. This was not confirmed in this sample (women = 0.53, men = 0.52, p = .299).

Finally, we expected gendered variation in bitter taste sensitivity, and that bitter taste preferences would predict variation in participation in political activities that involved social risk (operationalized in this sample indirectly with interest in politics). We tested this final component in two ways. First, we regressed interest in politics on the bitter taste scale (or PROP tasting) and an interaction between categorical gender and the bitter taste scale (or PROP tasting). We controlled for age. Full regression results can be found in Tables 2 and 3. We found no support for these hypotheses. For both bitter taste preference (the first H3 column in Table 2) and PROP tasting (the first H3 column in Table 3), we see a marginal direct effect, indicating that for men, bitter taste preference (p = .077) and PROP tasting (p = .093) may be associated with lower interest in politics. The joint effect of the interaction and direct effect indicates a clear null relationship among women for both bitter taste preference and PROP tasting on interest in politics. However, the interaction with gender was not statistically significant, so we cannot statistically distinguish the effect among men and women. The results of all models remained unchanged by controlling for the Kam (Reference Kam2012) risk scale (the second H3 columns in Tables 2 and 3). We included this control to determine whether bitter taste preferences and PROP tasting were simply a proxy for risk in the relationship with participation, but in fact, the effects on interest in politics were essentially unchanged controlling for risk, and there was no significant effect of risk on interest in politics.

We also conducted a mediation analysis to see whether bitter taste mediated the relationship between binary sex and political participation, following the same analysis strategy as in the adult sample. Results of the Sobel test indicate no evidence of a mediation effect for bitter food preferences on political interest with gender (Sobel = .39). There was an effect with PROP detection, however, such that the effect of gender increased once PROP detection was included (Sobel = .002). This demonstrates evidence of a possible suppressor effect and no mediation.

Hypothesis 4

H4 made substantively the same predictions as H3, substituting the continuous measure of gender identity instead of a dichotomous measure of gender. Substituting continuous gender identity for dichotomous gender identity led to substantively identical results for each test, with one exception. Using the continuous measure of gender identity, bitter taste preference was significantly associated with lower interest in politics among more masculine respondents (direct effect of bitter taste preference = –0.27, p = .028), and among those who are feminine, this effect may be attenuated or even reversed (interaction of bitter taste preference and gender identity where higher values are more feminine = 0.36, p = .089), although the interaction term was marginally significant (p = .077). These results suggest that bitter taste preferences may have a negative effect on interest in politics for masculine respondents and a positive (or possibly null) effect for feminine respondents.

Study 3 (Student Sample—Fall 2020)

The central variables of interest in this study are bitter taste preferences, risk tolerance, sex, gender identity, and political participation. Among respondents, 42.3% of the sample identified as male, 55.4% as female, and 2.3% did not answer the sex assigned at birth question. Among male respondents, 22.2% rated themselves at the highest end of the masculinity scale, and among female respondents, 22.2% rated themselves at the highest end of the femininity scale.

To create a bitter taste preference scale, we averaged the bitter food items that we asked participants to rate into a composite score (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

= 0.51, Cronbach’s alpha = .67). The bitter taste subscale had the lowest average score in terms of taste preference compared to the sweet (

$ \overline{x} $

= 0.51, Cronbach’s alpha = .67). The bitter taste subscale had the lowest average score in terms of taste preference compared to the sweet (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

= 0.71), salty (

$ \overline{x} $

= 0.71), salty (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

= 0.63), and sour (

$ \overline{x} $

= 0.63), and sour (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

= 0.56) taste subscales. We conducted the same procedure to create risk tolerance scales (Kam, Reference Kam2012, scale:

$ \overline{x} $

= 0.56) taste subscales. We conducted the same procedure to create risk tolerance scales (Kam, Reference Kam2012, scale:

![]() $ \overline{x} $

= 0.47, Cronbach’s alpha = .74; Weber et al. Reference Weber, Blais and Betz2002, scale:

$ \overline{x} $

= 0.47, Cronbach’s alpha = .74; Weber et al. Reference Weber, Blais and Betz2002, scale:

![]() $ \overline{x} $

= 0.52, Cronbach’s alpha = .86) and the same political participation index as in Study 1 (

$ \overline{x} $

= 0.52, Cronbach’s alpha = .86) and the same political participation index as in Study 1 (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

= 0.53, Cronbach’s alpha = .91). For PROP tasting, 55.1% of the sample were nontasters (i.e., they categorized the intensity difference between the control and PROP strip as zero or less, or they characterized the taste of the PROP strip as not bitter). There was an average difference in the ratings of taste intensity between the PROP strip and control strip of 0.15 (0.33 among tasters, the 44.9% of the sample who characterized the PROP strip as bitter and tasting stronger than control). Compared with males, females were significantly more likely to be tasters (men = 32.5%, women = 53.4%, p = .041), to have stronger difference ratings compared to control (men = 0.07, women = 0.20, p = .003), and to have stronger difference ratings when looking only at tasters (men = 0.21, women = 0.37, p = .024). PROP tasting was largely unrelated to bitter taste preference (r = 0.15 in full sample, p = .129; r = 0.04 among PROP tasters only, p = .822). In terms of other demographic variables, of those reporting race, our sample is 53.1% non-Hispanic White, 6.2% Black, 0.27% American Indian, Native American, or Alaska Native, 17.6% Asian, 0.27% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, 10.3% Other (predominantly self-identifying as Latinx or Hispanic), 4.3% mixed race, and 19.6% Latinx). The sample has a mean age of 20.1. Full demographic information can be found in the Appendix.

$ \overline{x} $

= 0.53, Cronbach’s alpha = .91). For PROP tasting, 55.1% of the sample were nontasters (i.e., they categorized the intensity difference between the control and PROP strip as zero or less, or they characterized the taste of the PROP strip as not bitter). There was an average difference in the ratings of taste intensity between the PROP strip and control strip of 0.15 (0.33 among tasters, the 44.9% of the sample who characterized the PROP strip as bitter and tasting stronger than control). Compared with males, females were significantly more likely to be tasters (men = 32.5%, women = 53.4%, p = .041), to have stronger difference ratings compared to control (men = 0.07, women = 0.20, p = .003), and to have stronger difference ratings when looking only at tasters (men = 0.21, women = 0.37, p = .024). PROP tasting was largely unrelated to bitter taste preference (r = 0.15 in full sample, p = .129; r = 0.04 among PROP tasters only, p = .822). In terms of other demographic variables, of those reporting race, our sample is 53.1% non-Hispanic White, 6.2% Black, 0.27% American Indian, Native American, or Alaska Native, 17.6% Asian, 0.27% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, 10.3% Other (predominantly self-identifying as Latinx or Hispanic), 4.3% mixed race, and 19.6% Latinx). The sample has a mean age of 20.1. Full demographic information can be found in the Appendix.

Based on a two-sample t-test, we found no significant sex differences in bitter taste preference (female

![]() $ \overline{x} $

= 0.51, male

$ \overline{x} $

= 0.51, male

![]() $ \overline{x} $

= 0.51, p = .920), and women in our sample are significantly more likely to participate in politics than men (female

$ \overline{x} $

= 0.51, p = .920), and women in our sample are significantly more likely to participate in politics than men (female

![]() $ \overline{x} $

= 0.59, male

$ \overline{x} $

= 0.59, male

![]() $ \overline{x} $

= 0.44, p < .001). In terms of the continuous gender identity, there was no significant correlation between bitter taste preference and masculinity (r = 0.07, p = .18) or femininity (r = 0.04, p = .47).

$ \overline{x} $

= 0.44, p < .001). In terms of the continuous gender identity, there was no significant correlation between bitter taste preference and masculinity (r = 0.07, p = .18) or femininity (r = 0.04, p = .47).

Hypothesis 1

In H1, we predicted that bitter taste preference would be positively associated with risk tolerance and that PROP sensitivity would be negatively associated with risk tolerance. To test this hypothesis, we regressed risk tolerance on the bitter taste scale and PROP sensitivity. We controlled for age and binary sex, but not education (as the sample is all college students). Unlike Studies 1 and 2, we found no support for H1 in Study 3. Neither bitter taste preferences nor PROP sensitivity had a significant relationship with risk attitudes. Full results are displayed in Tables 4 and 5.Footnote 6 Female respondents were lower in risk on the Weber scale but not the Kam scale.

Table 4. Regression results for bitter taste preference (student sample, 2020).

Note: Standard errors in parentheses. + p < .1; ** p < .05; *** p < .01.

Table 5. Regression results for PROP taste sensitivity (student sample, 2020).

Note: Standard errors in parentheses. + p < .1; ** p < .05; *** p < .01.

Bitter taste preference was related to greater risk-taking on the recreational subscale of the Weber scale (Appendix, Table A7), but not on any of the other subscales (compared with the wider range of effects in Study 2 in Appendix, Table A5). Contrary to Study 2 and to H1, in Study 3, PROP tasting was related to greater social risk-taking on the Weber scale (Appendix, Table A8).

Hypothesis 2

H2 predicted that bitter taste preference would be positively associated with political activities that involve an element of risk, following Kam (Reference Kam2012), and that PROP sensitivity would have the opposite relationship. To test this hypothesis, we regressed the political participation scale on the bitter taste scale and PROP sensitivity separately. We controlled for age and binary sex. We do not find support for H2. The bitter taste scale and PROP sensitivity were not significantly associated with political participation. With respect to the control variables, female participants were more likely to participate in politics.

Hypothesis 3

In H3, we made several predictions. First, we predicted that women were not more likely to be PROP tasters than men. Using sex in place of gender in this sample, this hypothesis was disconfirmed as 53.4% of female respondents were tasters and 32.5% of male respondents were tasters (p < .01). Second, we predicted that among men and women who are tasters, women would have greater bitter taste sensitivity. This was confirmed, as female tasters reported greater PROP sensitivity than males (male = 0.21, female = 0.37, p = .024). Third, we predicted that women would express a lower preference for bitter flavors. This was not confirmed in this sample (female = 0.51, male = 0.51, p = .920).

Finally, we expected that sex differences in bitter taste sensitivity and bitter taste preferences would predict variation in participation in political activities that involved social risk. We tested this final component in two ways. First, we regressed participation in politics on the bitter taste scale (or PROP tasting) and an interaction between binary sex and the bitter taste scale (or PROP tasting). We controlled for age. Full regression results can be found in Tables 4 and 5. We found a marginally significant interaction effect for bitter taste sensitivity (p =.094). The results indicate that for women, greater bitter taste preference may be associated with more participation in politics relative to men. We found no significant main effect or interaction for PROP. As expected, greater risk seeking predicted greater participation in politics.

We also conducted a mediation analysis to see whether bitter taste mediated the relationship between binary sex and political participation, following the same analysis strategy as in the adult sample. Results of the Sobel test indicate no evidence of a mediation effect for bitter food preferences on political participation with binary sex (Sobel = .93). Similarly, we found no evidence of a mediating effect of PROP taste sensitivity for binary sex (Sobel = .20), although the PROP sample was much smaller than in Study 2 (N = 98 compared to N = 366).

Hypothesis 4

H4 made substantively the same predictions as H3, except for using continuous measures of femininity and masculinity instead of a dichotomous measure of sex. Substituting these continuous gender identity measure for the dichotomous sex variable led several of the tests that were significant in H3 to no longer be significant. Specifically, the continuous measures were not significantly associated with PROP sensitivity, femininity was not a significant predictor of PROP sensitivity among tasters, and there was no interaction between bitter taste preference and either masculinity or femininity.

Discussion

Table 6 displays the results of the hypothesis tests across the three samples for ease of interpretation. For H1, bitter taste preferences were significantly associated with more risk-taking in two of our three samples, but detection and strength of PROP strip tasting were not. H2, enjoying bitter-tasting foods and participating more in politics, was supported by our Forthright adult sample but not the student samples. PROP tasting was not related to participation in the student samples. H3 was mostly disconfirmed across the samples, with only women being more sensitive to PROP strips and the gender interaction with bitter food preferences being significantly related to participation in one student sample. Finally, H4 had partial support, as the taste preferences for sex and gender identity were mixed across the samples, but there was no significant interaction between or mediation of sex/gender and bitter taste or PROP and political participation.

Table 6. Results of hypothesis tests across three samples.

More specifically within our nationwide sample of American adults, we found strong support that those who have a higher degree of preference for bitter tastes also tend to be more risk tolerant. In addition, bitter taste preference was positively associated with political participation, particularly those activities that involve social risk (Kam, Reference Kam2012). Contrary to our expectations, the relationship between bitter taste and political participation was not conditional on gender. In fact, higher masculine and higher feminine identification predicted more political participation. When we look at this effect within an individual’s self-reported binary sex, masculinity is positively associated with participation among women (r = .19, p < .001), and femininity with participation among men (r = .25, p < .001). Building on the growing evidence of gender identity’s effects on politics (Bittner & Goodyear-Grant, Reference Bittner and Goodyear-Grant2017; Gidengil & Stolle, Reference Gidengil and Stolle2021), future research should examine why these sex-atypical gender identities are predictive of political engagement.

In our 2019 student sample, bitter food preferences were associated with more risk tolerance, but this effect did not extend to detection of the PROP strip taste. PROP detection and the bitter food ratings were not related to political interest at the p < .05 level, and this relationship did not significantly differ by gender. There was weak evidence (at the p < .10 level) that bitter taste preference and PROP sensitivity may be predictive of lower interest in politics among men when the gender interaction was included in the model. Moving to the 2020 student sample, in which PROP was collected at home via mail, neither PROP nor the bitter food preferences were associated with risk or political participation. We did find that for women, greater bitter taste preference may be associated with more political participation relative to men. This mixed pattern of results may point to general differences in more representative adult versus student samples, including food taste, risk, and rates of participation. Or perhaps the effects we detected with food preferences in two of the three samples are more predictive of socialized bitter food-seeking rather than a biological ability to detect the PROP strip, as these are largely independent in the two student samples. A third possibility is that the relationships of political orientations with taste preferences and genetically influenced taste abilities may only emerge later in early to mid-adulthood, perhaps through a process of niche selection as people have more control over their environments.

Moreover, the results from the two student samples do not always align. We found stronger (if still sometimes weak) evidence for the effects of bitter taste preference and PROP sensitivity on risk attitudes and political participation in the 2019 sample than the 2020 sample (Studies 2 and 3). This may be, in part, the result of random sampling differences. However, Study 3 was collected in in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic prior to the widespread availability of vaccines, and we strongly suspect that this may have affected the analyses conducted here. This event had deleterious consequences for the mental health of students that may have affected the composition of the sample (e.g., the proportion of students opting into an extra credit subject pool) or the measurement of variables of interest and the relationships among them. These effects may explain some of the differences between Studies 2 and 3 with regard to the effects of bitter taste preferences. Most notably, the pandemic made the administration of PROP taster strips in the lab (as was done in Study 2) impossible and necessitated mailing them to students, many of whom were not on campus in the fall of 2020. Some of these students (25%) opted out of providing an address for the mailers, and many (65% of those to whom mailers were sent) either did not receive the mailers or did not respond to the PROP questionnaire after the mailers were sent. The result is that the sample size for the PROP taster strips in Study 3 was many times smaller than we had intended when the study was designed prior to the pandemic. Examining the results across our samples indicates there could be a life course effect for bitter taste preferences and the connections to risk-taking and our other variables of interest. Because taste and food preferences can be habituated and influenced by lifestyle and economic status (Higgs et al., Reference Higgs, Cooper, Lee and Harris2015; Sagioglou & Greitemeyer, Reference Sagioglou and Greitemeyer2016), it is valuable to study these relationships across different types of samples.

We acknowledge several limitations to our study. Because of economic and COVID-19-related constraints, we were only able to analyze PROP detection within a student sample that also had many at-home participants rather than the strict protocol of the lab. The data were also collected during a global pandemic and a contentious U.S. presidential election, which may have impacted risk tolerance, political participation, and even food preferences. Furthermore, the modest effect sizes and explanatory power of our models limits how much of the variance in political engagement we can reasonably explain with our variables of interest. Thus, we are certainly cautious in our interpretations, but we think this research helps move the conversation forward regarding the connections between biology and politics. Our studies cannot speak to causality, but future research should continue to explore the genetic, physiological, and environmental connections between these variables of interest.

Contributing one more correlate of democratic engagement, though it may only explain a very small amount of the variation in participation, may seem only of scholarly use, but we would argue that investigating the biological and life preference connections to political involvement helps illustrate a broader picture of public life. That is, politics is merely another element in an individual’s environment that is impacted by instincts, dispositions, socialization, and context. People who take risks are more likely to engage in politics (Kam, Reference Kam2012) and more likely to try and enjoy a wider variety of foods, making politics as much an “experience” as a diligent exercise in citizenship. Including both PROP detection and self-reported food preferences provides leverage on understanding how much of the effect on risk and politics may be biological or culturally learned. We know that individuals develop tastes for substances like coffee over their life course, but the variation in taste-related genetic markers and anatomy of our taste buds suggest there may be a limit on overriding our biology.

Gender differences across risk tolerance, taste preferences, and political engagement suggest that women may have evolved and be socialized to exercise restraint and caution. On the flip side, trying new foods, taking risks, and getting politically involved have benefits that may be missed by those shying away from the possibility of unpleasantness or danger. Indeed, some psychologists argue that more risk-taking can increase excitement and life satisfaction, and this process could be facilitated through our taste buds. In a series of experiments in two different cultures, Vi and Obrist (Reference Vi and Obrist2018) found that ingestion of sour tastes led to the highest level of risk-taking behavior when compared with bitter, salty, sweet, and umami tastes. Interestingly, sweet tastes—which have been linked to prosocial behavior and agreeableness—led to lower levels of risk-taking, consistent with our theoretical argument about gender differences in all these domains. Bitter and salty tastes had no effect on risk-taking (Vi & Obrist, Reference Vi and Obrist2018). Taken with our findings, particularly with the nonfood taste of PROP and extant literature on its genetic receptor, future research should include investigations of the malleability and habituation of taste preferences and whether these connections to risk-taking persist across time.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/pls.2021.20.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by the Association for Politics and the Life Sciences and Indiana University–Purdue University Indiana Office of the Vice Chancellor of Research Rapid Response Grants. We would like to thank the Political Science Subject Pool coordinators at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC)—Tolgahan Dilgin and Aleena Khan—for assistance in collecting the data for Studies 2 and 3, respectively. We would also like to thank our team of research assistants at UIUC—undergraduates Marissa Finley, Amanda Nguyen, and Sarah Scharfenberg and graduate students Jaeseok Cho and Seyoung Jung—for their help in collecting the lab data for Study 2.

Competing Interest

None.