In the two years following the September 2008 collapse of the American investment bank Lehman Brothers, governments in advanced industrial economies committed over two trillion euros to bailing out banks and other financial firms.Footnote 1 The largest of these companies were labeled “too big to fail”: their scale, complexity, and mutual interconnectedness rendered them essential to the continued functioning of the financial system and, by extension, wider economy. The inadequacy of financial regulation prior to this financial crisis has been cited as among its primary causes, and so addressing the too-big-to-fail problem with new rules became an essential policy priority after the bailouts had stabilized the system.Footnote 2 In this paper, I examine the politics of what has been called the “most far-reaching” measure proposed to bolster systemic security: structural banking regulations.Footnote 3 By separating commercial and investment banking in firms, structural reforms threatened the universal banking model utilized by most of the world's largest banks. Yet, despite substantial opposition from the banking industry, structural reforms were given serious consideration in a handful of countries badly affected by the crisis.

Among these countries, the opposite approaches taken in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands stand out. Both countries were similarly hit by the crisis itself, bailing out some but not all their largest banks; both hosted similar financial systems, comprising a small number of systemic universal banks working alongside well-developed capital markets; and their policy cycles were closely aligned and informed by expert commissions assembled to assess reforms. Given these striking parallels, why did the UK proceed with its strong “ring-fence” structural break while the Netherlands eschewed this approach in favor of softer measures targeting banking culture? In this paper, I isolate aspects of the countries’ divergent majoritarian and consensus party systems as the key factors that determined policy challenges to the banks’ own reform prescriptions. Combining theoretical strands from the business power and comparative democracy literatures, I argue that levels of party competition over regulatory reform crystallized outcomes at important junctures in the countries’ policy cycles. In the UK, competitive political parties wrested banking reform from its default setting of interest group issue ownership; in the Netherlands, an absence of political action led to the banks seizing and holding the regulatory initiative by default. I identify two divergent dynamics of the countries’ party systems that played out at formative junctures, leading to alternative reform outcomes: power sharing and coalition formation. The analysis presents original interview data with key stakeholders alongside primary and secondary sources.

Unpacking this approach involves charting a course between two foundational perspectives in political science: what Hacker and Pierson call the “Schattschneiderian” and “Downsian” schools of political economy.Footnote 4 These labels respectively emphasize the primacy of interest groups and voters in shaping policymaking. I acknowledge that political conflict in a policy realm invariably exists on a continuum between poles, along which politics may slide in response to events such as crises. However, this movement is contingent on the response of political parties, the key mediators between the twin stimuli of interest group preferences and voter sentiment. In this paper, I argue that a country's institutionalized party system exerts a profound influence on this mediation, ultimately conditioning the location of a given policy area along the spectrum. In so doing, I hope to prompt recognition of formal political institutions, specifically party systems, that have been largely overlooked by scholars of the political economy of financial regulation.

The paper proceeds in three sections. First, I briefly situate structural regulations in their historical and contemporary contexts, describing their significance amid the Basel III capital regime and banks being ascribed “systemic” status. This provides the rationale for narrowing the case focus to the UK and the Netherlands and a subsequent discussion of the limitations of alternative hypotheses. Second, I recognize the utility of the business power literature in a policy landscape traditionally dominated by narrow interest groups, before suggesting how recent work may be augmented by an appreciation of comparative democratic effects. I start from a premise that political parties are key units of analysis, since they ultimately mediate between mass publics and interest groups in policymaking processes. The dominance of one or the other of these forces in political considerations is contingent on several factors: first, the salience of political issues and following on from this, the ways in which political parties respond to salient issues. I then outline two specific, related factors, which collectively led to “systemic political action” and “inaction”: power sharing and coalition formation. The third section applies this general model by reconstructing the cases, identifying the critical junctures around the countries’ 2010 elections and subsequent events, which “locked in” paths towards reform and relative continuity. I then briefly conclude.

Financial crises and structural regulations

Structural banking regulations seek to “sever the link, or insulate, ‘traditional’ retail banking activities from riskier activities pursued by banks on capital and money markets.”Footnote 5 They are thus at odds with “universal banking,” which combines both forms seamlessly and had secured practical global ubiquity prior to the crisis, after the 1999 repeal of the United States’ Glass-Steagall Act.Footnote 6 Glass-Steagall was a vestige of the devastating impacts of the Great Depression, and to this day, Glass-Steagall's demand for total separation between federally-insured commercial banks and securities-holding investment banks remains a high watermark for structural regulations, against which new proposals are compared.Footnote 7

A host of alternative regulations designed to shore up individual banks and broader systemic security also emerged in the intervening period between the two crises, leading policymakers to assemble multifaceted packages of regulatory reform, both nationally and internationally.Footnote 8 Among these, bank capital requirements are most consequential here.Footnote 9 Capital rules represent either an alternative or a complement to structural regulations in their own right, as both share a similar desire to secure financial systems by reducing the systemic threat posed by large, interconnected banks. Moreover, in their most recent manifestation, capital requirements have led to the development of “global-systemically important bank” (GSIB) status, reassigned annually by the Financial Stability Board (FSB) to a global “top league” of thirty-eight banks located in eleven countries since 2011. This imposes extra capital requirements and accountancy standards on the most systemically integral firms and adds formal weight to the empirically nebulous term “too big to fail.”Footnote 10

However, while over a hundred states, including all European Union members, have voluntarily adopted the latest iteration of the de facto global minimum standards for capital, Basel III (2010), far fewer implemented structural reforms.Footnote 11 Five countries proceeded, while the Netherlands formally explored the option before pulling back. This leads to the use of a “most similar-systems design” logic of comparative analysis in this paper.Footnote 12

Case selection and alternative explanations

The five countries that implemented structural reforms are Belgium, France, Germany, the UK, and the United States. In each case, the government bailed out at least one FSB-designated GSIB during the subprime crisis (2007–9), but beyond this starting point, there are consequential differences both between the ways these countries experienced the crisis and the terms of their final reforms. An exhaustive description of these details is beyond the scope of this paper, suffice to note that the UK's regulation has been described as a particularly comprehensive reform, certainly when cast against comparable Franco-German laws.Footnote 13 The British “ring-fence” mandated full legal and economic separation between the two wings of UK banks with over £25bn in domestic retail deposits, and unlike the French and German laws did not allow market making in the purview of the retail bank. Nevertheless, juxtaposing two cases that categorically did and did not adopt the legislation simplifies this study.

On the independent variable, the UK-Netherlands dyad also represents the “most-similar” comparison from the array in table 1. The two countries share multiple commonalities in terms of how they experienced the crisis and approached the structural reform question. First, while scholars have shown that not all bailouts are alike, these countries’ were.Footnote 14 While Switzerland, France, and the United States made profitable interventions, the Netherlands was forced to fully nationalize one of its Big Three banks (ABN-Amro) and recapitalize another (ING) at an overall loss to the taxpayer, leaving only one unassisted (Rabobank).Footnote 15 The UK government became majority owner of RBS and minority owner of Lloyds, again at an overall loss, while leaving others untouched (Barclays, HSBC, Standard Chartered) through the re-regulatory process. The UK committed 23.1 percent of GDP to its bailout package, while in the Netherlands this figure was 23.7 percent.Footnote 16

Table 1. Crisis Effects and Structural Outcomes: FSB-Designated GSIB Host Countries

Equally, both countries were governed mainly through the 2009–14 policy cycle by conservative-led coalitions, and their legislative processes were influenced by multiple groups of experts at various important points. Unlike in the UK, the Dutch Labor Party (PvdA) entered government and controlled the Finance Ministry from November 2012 onwards, but still did not push for reform. Partisan regulatory accounts, which suggest that incoming Left governments should introduce tougher new regulations after right-wing deregulation leads to booms and busts, are controlled for by this comparison.Footnote 17

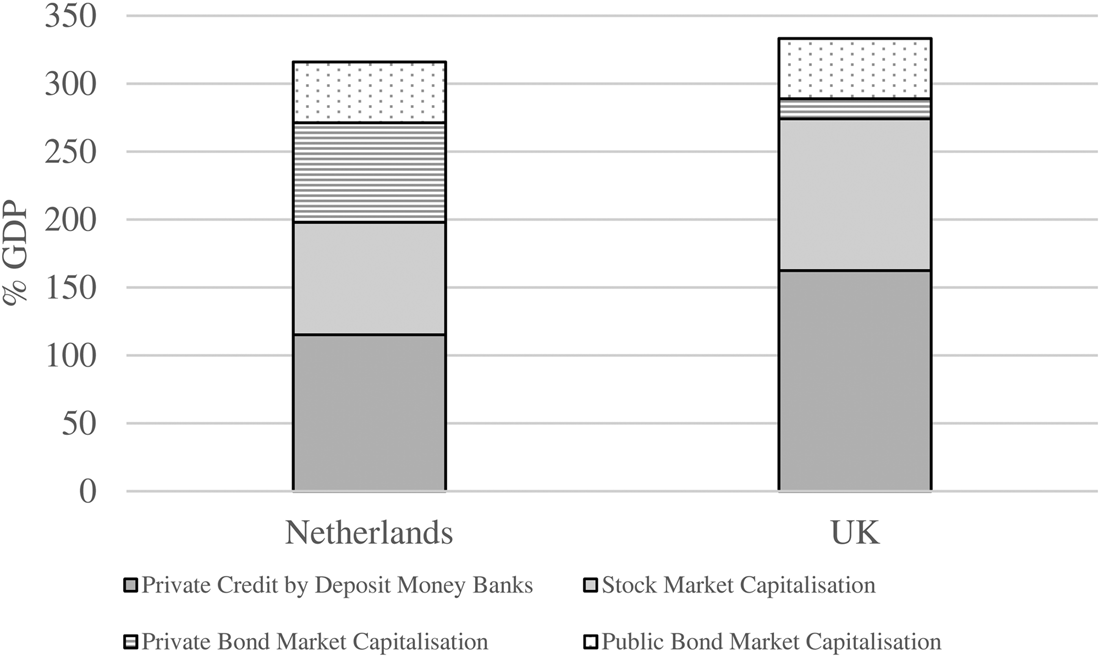

An alternative explanation could center on variable financial systems, as per Zysman's influential bank- and market-based dichotomy.Footnote 18 A simple hypothesis might be that a country reliant on bank credit would be more hesitant to constrain its leading banks than a country with developed capital markets funneling alternative finance to nonfinancial companies. In this scheme, the UK and the Netherlands have historically been considered weak market-based and “hybrid” financial systems respectively.Footnote 19 However, as figure 1 demonstrates, financing the real economy in both cases now combines banks and capital markets working in tandem, with the stock market larger in the UK and bond markets in the Netherlands. Indeed, in light of a recent resurgence in its banking sector, financial systems scholars now concede that “in some sense [the UK] seems to be both marked-based and bank-based,” in a manner akin to the Netherlands.Footnote 20 Taking a bird's eye view of the countries’ aggregate financial systems, then, does little to elucidate reform outcomes.

Figure 1: Sources of Funding for NFCs, 2006–15

One criticism of the financial systems approach has been its insensitivity to changing bank business models, as GSIBs acted as drivers of change by increasingly turning to the capital markets themselves for funding and investment opportunities.Footnote 21 It is therefore necessary to briefly acknowledge some differences and further similarities between the firms in question. First, investment banking was more prominent in the British GSIBs overall than in the Dutch. In 2010, investment assets constituted 60 percent of total assets at Barclays, 52 percent at RBS, 44 percent at HSBC, and 27 percent at Lloyds; against 40 percent at ING and 19 percent at ABN-Amro. In terms of Tier 1 regulatory capital, however, all firms except Rabobank (16.1 percent) held an average in the range 12.9 percent–13.6 percent between 2009 and 2015, and so there was no discernible trend towards higher voluntary capitalization in either country.Footnote 22

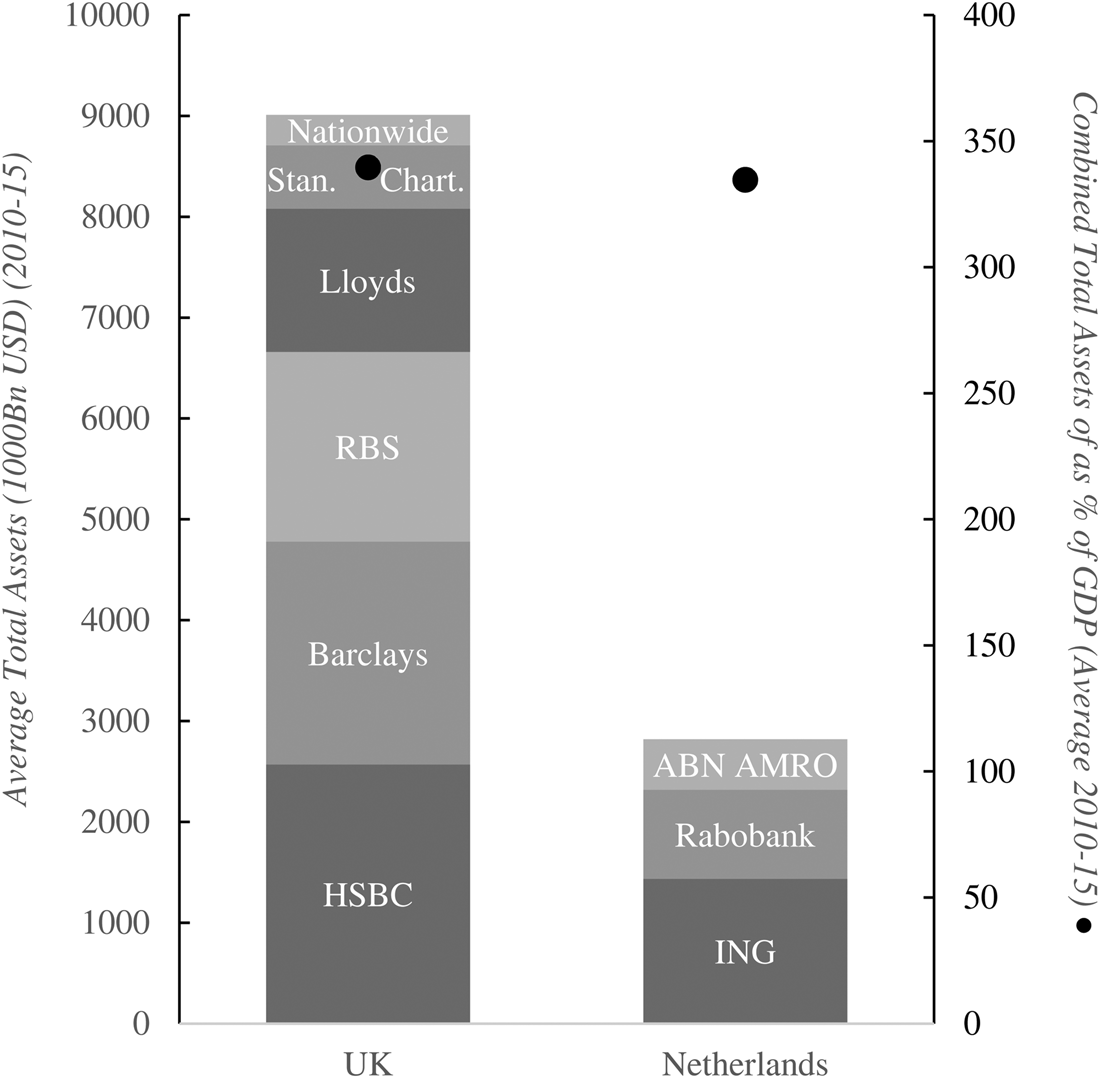

More importantly, structural measures were not solely proposed for conflict of interest issues. Prominent critics also saw the measures as a means to “cut down to size” large banks and reduce the scale of the too-big-to-fail problem.Footnote 23 Indeed, economists questioned whether the banks might have also become “too big to save,” in a future crisis, irrespective of policymakers’ intentions.Footnote 24 The relative scale of the overhanging too-big-to-fail problem was very similar in the two countries after the crisis. While the British GSIBs held almost three times the Dutch GSIBs’ total assets through 2015, relative to their national economies, these levels were almost equivalent (339 percent and 334 percent of GDP respectively, see figure 2). This proportional figure was notably smaller in larger, diversified economies with a greater number of similarly sized and smaller GSIBs, such as Germany (134 percent) and the United States (63 percent).Footnote 25

Figure 2: Total and Relative Size of GSIBs

Speaking of financial services’ contribution to the British economy, Chancellor George Osborne said the re-regulatory process was animated by the “British dilemma”: balancing the benefits that a large financial services sector delivered against the threat it posed to the wider economy. However, this might equally apply to the Netherlands: Amsterdam remains a prominent financial center, and financial services also represent a strategic area of comparative advantage for the Dutch economy.Footnote 26 In this context, the fact that a British Conservative-led government legislated against the express wishes and established models of its two largest non-supported banks (HSBC and Barclays) while their Dutch counterparts did not is noteworthy, irrespective of precise business models. In sum then, though the two cases are not perfectly aligned, the way they experienced the crisis, the orientations of their politics and economies and the use of expert policy panels provide a reasonable basis for structured comparison that challenges existing theoretical approaches while prompting further theorizing.

Business power and interest group politics

Business power theories offer an alternative framework through which to interpret this divergence. Traditionally, business power has been categorized as either “instrumental” or “structural” in form, depending on how policymakers are perceived as being influenced. These modes might respectively be understood as synonymous with political activities, such as lobbying, networking, and campaign contributions;Footnote 27 and economic logics, the existential, electoral necessity for policymakers to induce investment, jobs, and growth; thereby granting leverage to private firms in capitalist economies.Footnote 28 Given banks’ often sizable (political) resources and their central role in the economy, they have become a logical locus for theoretical refinement here.Footnote 29

Singularly instrumental accounts of financial power still abound, drawing inferences from banks’ lobbying money and networks with regulators and policymakers to their political power.Footnote 30 However, recent contributions drawing on structural precepts have sought to examine both forces in concert.Footnote 31 Large-N studies operationalize these forms of power using proxies, such as examining firms’ size (structural power), lobbying spend (instrumental power), and preferences against policy outcomes.Footnote 32 These data are not readily available for most European countries, and here I focus on a small number of country cases and units of analysis (large banks), and so a qualitative framework is more apposite.

Small-N comparisons have, instead, sought to tease out causal mechanisms by studying information flows and “signaling games” between policymakers and firms. Given the information asymmetry that generally exists between the two sets of actors, both seek exchanges that will shape diligence and policy. Indeed, far from being dopes who are unwittingly manipulated by well-informed lobbyists, policymakers often explicitly seek out information from industry when drafting legislation.Footnote 33 Firms are typically, though not always, skeptical of new government regulations and they are generally better informed than policymakers and public officials about the potential sectoral or firm-wise consequences of proposed measures.Footnote 34 Their success in information exchanges ultimately hinges on how credible policymakers find their information. When trying to stymie or water down proposals, this may comprise a combination of messages: direct cost projections; wider negative inducement effects on firms’ ability to invest; or outright disinvestment threats, such as “capital strikes” or relocation to friendlier regulatory jurisdictions. Case studies have sketched out how banks and other large firms have combined these instrumental and structural logics and tactics in real signaling games with policymakers, both pre- and post-crisis.Footnote 35 The asymmetry of knowledge, resources, and, thus, countervailing critical voices in the financial regulation policy ecosystem has also been empirically observed,Footnote 36 leading scholars to label it an archetypal case of “regulatory capture,” where firms (banks) may effectively dictate terms to regulators.Footnote 37

Systemic political (in)action

However, even in unbalanced policy arenas, powerful actors are subject to constraints, and Culpepper's work on hostile corporate takeovers highlighted an important one: issue salience. Culpepper demonstrated that when politics in an issue area of low public interest depart from their default “quiet” setting and become “noisy,” business interests may lose their grip on policy agendas.Footnote 38 Financial regulation is an exemplary case of “quiet politics,” a traditionally exclusive realm dominated by organized business interests,Footnote 39 brought into sharp relief by the unforeseen focusing event of the financial crisis.Footnote 40 However, while a window of high salience might have been a necessary condition for the adoption of a punitive policy, such as structural reform, was it sufficient alone to guarantee adoption in all cases?

A formative descriptive observation about the two cases concerns differences in levels of political competition. While the banking crisis was salient in both cases, only in the UK did major parties articulate rival reform agendas, a characteristic almost entirely absent in the Netherlands. This politicization had the effect of shifting the mode of politics from “interest group oriented” to “voter oriented” in the UK, but not in the Netherlands. But why was this the case? I argue that this owes to distinctive features of the countries’ party systems. It catalyzed the British “majoritarian” system more than it did in the diffuse “consensus” Dutch system. This was decisive in setting the reform agenda for the divergent policy outcomes in the two cases.

The UK and the Netherlands have generally been juxtaposed as examples of two contrasting modes of democracy: “majoritarian” and “consensus,” in Lijphart's terms.Footnote 41 There are multiple formal and informal institutional dimensions to this typology, but I focus on two related by-products of their contrasting electoral systems, from which competition and causal mechanisms for continuity and change in the two countries, in these cases, flowed: power sharing and coalition building.

Admittedly, the link between electoral systems and policy outcomes is disputed territory; there is little by way of little scholastic consensus.Footnote 42 However, certain effects, or by-products, can clearly be traced back to these systems, which in turn creates the basis for connecting a stepwise causal mechanism from electoral system to policy. First, in consensus systems, multiple parties tend to share office, often moving frequently in and out of governing coalitions. In the Netherlands, between 2000 and 2010, six different major parties were involved in power-sharing arrangements in different combinations: CDA (center-right), PvdA (center-left), D66 (center-liberal), VVD (center-right), LPF (right-populist), and CU (center-right). In such models, legacy policies—in this case, financial regulations—are not as readily attributable to single parties.Footnote 43 In contrast, only Labour had ruled with an outright majority in the UK since 1997, and prior to this the Conservatives had governed for eighteen years. Indeed, prior to 2010, no functioning coalition government had governed Britain since World War II.

The effect of this majoritarian dynamic is a concentrated policy legacy, or output legitimacy being readily attributable to particular parties. This has clear implications for political competition, suggesting blame games over legacy policy failures are more likely to occur in majoritarian systems that strongly link single parties to government and governance. Negative criticism through blame is inevitably followed by the positive articulation of distinct proposals for reform, slated by policymakers-in-waiting, wishing to unseat incumbents. Conversely, such political thermodynamics are likely to be consigned to fringe parties in systems where the responsibility for policy failure is difficult to attribute to a single major party.

Second, corresponding proportional electoral systems in consensus countries are much more likely to lead to coalition governments than majoritarian processes,Footnote 44 and the post-election coalition building dynamics of the two countries may be meaningfully different depending on processes and numbers of parties involved. In the strongly majoritarian UK, coalitions were historically extremely rare. Between 1946 and 2009 inclusive, the British executive was exclusively formed by a single party and the Netherlands was exclusively governed by coalition.Footnote 45 The resulting hung parliament returned in the UK was almost unprecedented, while the results of the Dutch election were routine. The fragmented Dutch coalition formation process typically lasts several months as informateurs try to establish a working majority, while the two-party British coalition was secured after intense transactional negotiations between the Liberals and the two largest parties just days after the election. The temporal effect of this process was to usher in a new government while crisis salience was still high in the UK, delaying this until impetus had faded in the Netherlands.

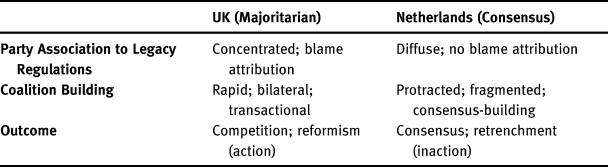

Together, these party system dynamics amount to “systemic political action” on the part of British political parties and “inaction” in the Netherlands (see table 2). The effects of these pre- and post-electoral processes wrested agenda control from its interest group default setting in the UK but not in the Netherlands. In the UK, competition and rapid reconciliation allowed for meaningful political steps to be taken, challenging leading banks’ prescriptions for reform, while in the Netherlands these prescriptions were retrenched by a party politics that left them unchallenged for an extended period.

Table 2. Party Systemic Characteristics Leading to Political Action and Inaction

Cases

The UK

The British case was frontloaded by political dynamics and decisions that would ultimately determine the fate of the country's structural reform legislation several years later. It is necessary, then, to isolate the junctures and factors that set this process along its path. There are three discrete periods of interest: the competitive political cycle that predated the 2010 election; the post-election coalition formation and the ICB; and the post-ICB consolidation between 2011 and 2013. These are addressed in turn.

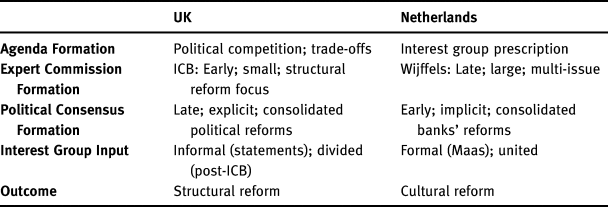

Table 3. Comparison of Policy Inputs and Outcomes

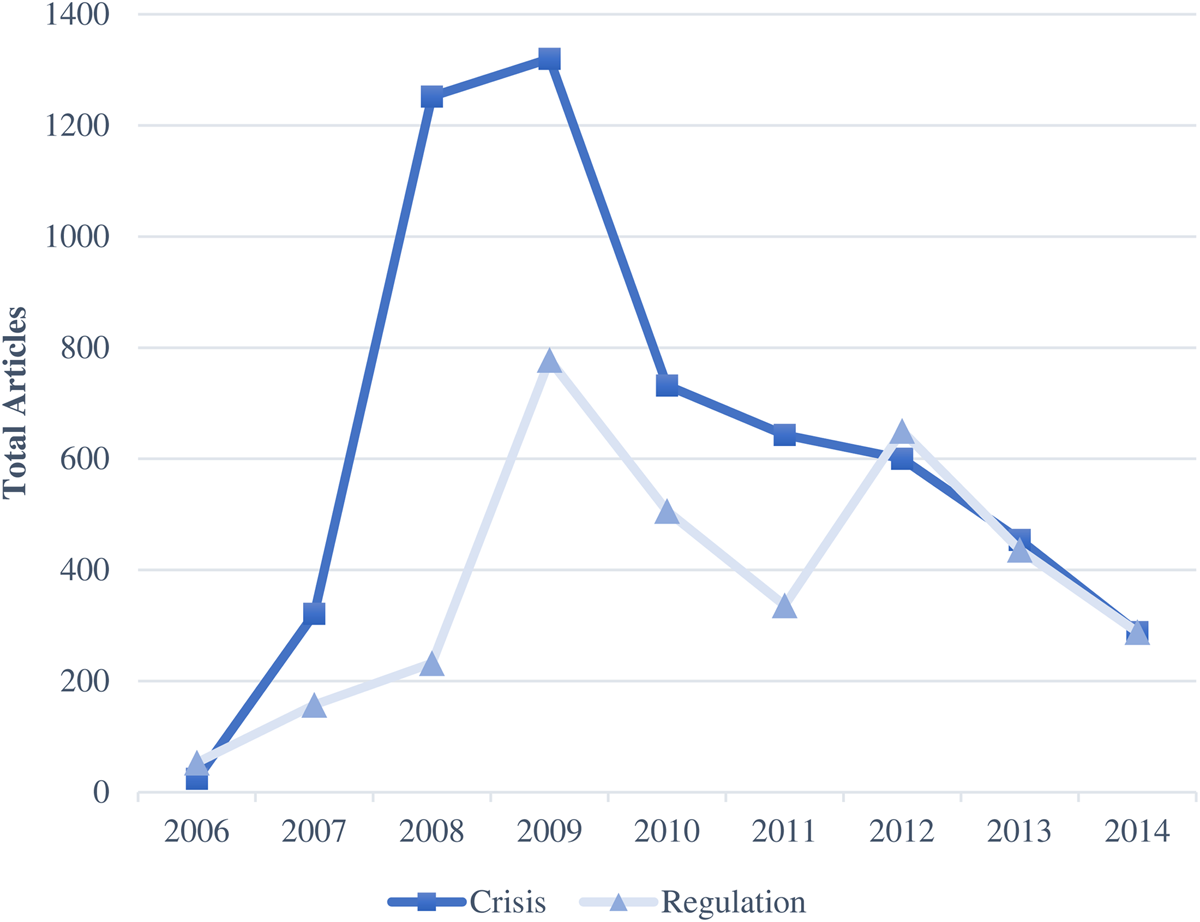

Prior to the election, the British GSIBs established their position through their umbrella body, the British Bankers’ Association (BBA). Chief Executive Angela Knight dismissed structural reform, calling instead for “boring technical steps,” including accountancy rules and capital requirements, and signaled that banks would likely exit the UK were a British Glass-Steagall rule to be implemented.Footnote 46 However, against a backdrop of popular interest in the crisis, as shown by figure 3, the leading parties—Conservatives, Labour, and Liberal Democrats—each devised a unique set of regulatory reform proposals that formed part of their 2010 campaigns.

Figure 3: Coverage of the Financial Crisis in the UK (2006–14)

All parties agreed with the BBA on a basic need for tougher capital requirements, but beyond this, there were significant departures. A key battleground between the two largest parties concerned regulatory agencies. After consulting former UBS executive Sir James Sassoon, the Conservatives prioritized the abolition of the lead regulator, the Financial Services Authority (FSA), and the restoration of prudential supervisory powers at the Bank of England. The FSA was established in 2001 as a key plank of Labour's embrace of the City of London, as the government courted political credibility and investment with and from finance capital.Footnote 47 However, the FSA had drawn heavy criticism for an overemphasis on consumer issues at the expense of prudential oversight, and had itself conceded that it had operated according to a light-touch mantra.Footnote 48 The Conservatives’ attack on the FSA, the organization most tangibly linking Labour to the crisis, was apparently sincere but also calculated. A Conservative former Junior Minister stated, “we saw [the FSA] as Labour's regulator and an organization that wasn't fit for purpose, so we were quite eager to see it go.”Footnote 49

The FSA itself and Labour responded defensively, arguing for greater resources and powers, allowing the regulator to constrain executive pay and compel banks to draw up “living wills” to prove their resolvability.Footnote 50 However, senior Labour ministers forcefully rejected proposals to break up the banks.Footnote 51 The Conservatives were less hostile, noting potential merits to structural reforms but ruling out any unilateral movement that might threaten Britain's competitiveness, instead prioritizing international cooperation on the issue.Footnote 52

The third party, Liberal Democrats, who had never held office, outflanked both their rivals. Their proposal attacked both the banks and rival parties, pledging that only they would “establish clear separation between low-risk retail banking and high-risk investment banking,” resurrecting a British form of Glass-Steagall.Footnote 53 The party's line on bank reform was entrusted to their Treasury Spokesperson, Sir Vince Cable. As early as 2008, Cable called for “revolutionary changes [to financial regulations] . . . once the dust ha[d] settled.”Footnote 54 He stated that, “I think what we said resonated with people. We didn't have historic ties to the City and we called it as we saw it. . . . It was clear to me that the banks needed to be broken up.”Footnote 55 Competition between the parties is clear in these three positions. While Labour defended its record and regulator against Conservative proposals that linked its time in office to the crisis, the Liberal Democrats presented a comparatively radical alternative that surpassed both established parties, directly imposing harsh structural breaks for the banks. This competitive dynamic shaped the early parameters of the policy agenda.

The ultimate outcome of the election—the formation of a stable two-party coalition—was unprecedented in modern British politics. Only once since 1929 had the majoritarian electoral system not delivered a majority government, and in 1974, coalition talks and minority government failed. The competitive legacy and dynamics of the majoritarian system had placed parties in an unfamiliar situation, which necessitated swift strategic trade-offs to secure a stable partnership. This led to a period of intense negotiations in the days following the election before several quid pro quos facilitated the coalition agreement. The speed of this agreement is important, because it ensured the government was formed at the height of the crisis’ salience, in mid-2010 (figure 3), during a window in which banks had not been able to secure an accepted roadmap to reform. One key coalition trade-off involved banking regulation: Cable agreed to FSA-abolition in exchange for Osborne making a credible commitment to further exploring unilateral structural reform.Footnote 56 This was manifest in the form of the ICB expert panel in June 2010, the composition and remit of which was politically determined, and was essential to ultimately securing reform.

ICB selection was an explicitly political process, as the two ministers hand-picked members.Footnote 57 Osborne consulted reformist Bank of England Governor Sir Mervyn King for advice on suitable candidates, while Vince Cable pushed for the journalist Martin Wolf, who had been a leading commentator on the crisis.Footnote 58 Martin Taylor was a notable inclusion, as the former Barclays executive had been especially critical of “parasitic” investment banks in his testimony to the unrelated bi-partisan Future of Banking Commission, which had fully endorsed structural reforms just as the ICB was being formed.Footnote 59 These two were joined by competition expert Clare Spottiswoode and former JP Morgan executive Bill Winters. Collectively, the five members combined diverse backgrounds with extensive expertise, and were headed up by Sir John Vickers, a former chief economist at the Bank of England, who was unanimously praised in multiple interviews as “well-respected,”Footnote 60 “an outstanding academic,”Footnote 61 and “fair-minded.”Footnote 62 They were supported by a small, dedicated secretariat, who were seconded to support the ICB over fifteen months, helping to collect exhaustive data, including thousands of submissions, sensitive balance sheet information and testimony from banks, other businesses, and consumer groups.Footnote 63 The group was characterized throughout by a collegiate work ethic that sought to achieve a workable regulatory settlement, while disagreements were sporadic and superficial.Footnote 64

Even before it published its final recommendations in September 2011, the ICB worked to fatally undercut the credibility of the banks’ cost signals, which were designed to ward off structural reforms.Footnote 65 The commission's formidable expertise and resources shielded the Treasury from asymmetric industry-to-policymaker communications and forced the banks to abortively redirect lobbying toward the premier minister.Footnote 66 First, the ICB's interim report questioned the impact of banks relocating their headquarters after HSBC, Barclays, and Standard Chartered had each commenced strategic domiciling reviews through 2011–12.Footnote 67 The commission then directly challenged HSBC's projections of scope and synergy gains achieved under a universal banking model, and disputed the claim calculated by a consultants hired by the banks that the operational costs of the ring-fence would be between £12–15bn per annum.Footnote 68 The ICB instead calculated collective costs would fall between £4–7bn per year, with the majority being offset by a reduction in undesirable implicit guarantees.Footnote 69 The “social costs” to the UK economy, stemming from diversification losses and operational costs, were estimated at £1–3bn per annum. This did not include the one-off expense of implementing the reforms, which the Treasury later estimated collectively to be between £500m–£3bn.Footnote 70 Such estimates dwarfed and undermined those made by the banks themselves, fatally reducing the credibility of their cost-signaling and establishing the viability of a unilateral structural measure, albeit in a more moderate guise than Cable had envisioned.

Industry lobbying rebounded in the two years between the publication of the ICB's report in September 2011 and primary legislation in December 2013, but the upshot of structural regulation becoming a firm proposition was that leading banks fractured and angled for bespoke concessions that would dilute costs based on their own business models, leaving only HSBC acting in a mode of outright hostility.Footnote 71 Certain concessions were granted, such as a de minimis exemption that allowed the largely Asia-based Standard Chartered to avoid compliance, but the ICB report acted as empirical ballast for the final law that would follow after two years of further consultations.

The third phase demonstrates how political consensus had crystallized around structural reform in the UK after the ICB had firmly established it on the policy agenda. The Parliamentary Commission on Banking Standards (PCBS) considered ring-fencing alongside a broader range of issues over banking culture, and ran concurrently through 2013 after Libor and a series of smaller scandals had refocused public attention on the British GSIBs throughout 2012. Osborne affirmed his reconciliation to unilateral reform by appointing chair the reformist Conservative Andrew Tyrie, a man labelled “the most powerful backbencher in the Commons” in his capacity as Treasury Select Committee Chair.Footnote 72 MPs with relevant interests and expertise from all major political parties worked amiably on a broad range of questions concerning the future of finance, and throughout the process, the banks lacked a figure in Parliament prepared to publicly defend them and voice concerns over the foundations laid by the ICB.Footnote 73 The PCBS endorsed and strengthened the ICB's findings, and Tyrie became a vocal critic of banks’ attempts to weaken the ring-fence with lobbying.Footnote 74 Its main legacy was the “electrification” of the ring-fence, allowing the regulator to break up banks if they attempted to “game” and circumvent separation rules.Footnote 75 By 2013, Labour had also fallen fully behind the ICB's proposal, with opposition figures now focused primarily on preventing the government from reneging on implementation. Primary legislation in December 2013 stayed largely faithful to the ICB report, setting a January 2019 deadline for the separation of commercial banking and core investment practices.

The Netherlands

Howarth and Quaglia note that the fourth to sixth largest European economies—Italy, Spain, and the Netherlands—had deliberately not adopted legislation and were content to wait and see what pan-European directives would emerge from Brussels.Footnote 76 Among this group, the Netherlands is an outlier for reasons already described: two of its GSIBs, ABN-AMRO and ING, were badly exposed and it took similar steps to secure them at similar expense to the UK. While neighbors on all sides were attempting to shape their own destiny on the issue with domestic measures, the Netherlands settled on waiting for pan-European measures. However, this position was not reached by default, and was also the result of a political process that downplayed structural regulations in favor of a change in business culture, at the behest of the banks themselves. Again, path-defining inputs to the policy cycle were frontloaded and can be broken into discrete phases around the 2010 and 2012 elections.

The Dutch pre-election policy agenda was marked by two early and consequential departures from the UK's: the Dutch Banking Association (NVB) was more proactive in establishing a distinct reform agenda than the BBA; and leading Dutch parties conspicuously did not challenge this with rival agendas of their own. This was despite the fact that the subprime crisis was salient through 2009, as figure 4 indicates. As in the British case, these early dynamics set the Netherlands on a decisive path of its own.

Figure 4: Coverage of the Financial Crisis in the Netherlands (2006–14)

NVB proactivity was manifest in the Maas Commission report, released in April 2009. The NVB's own commission comprised three former executives: one from each of the Big Three Dutch banks, alongside an academic economist. While acknowledging the banks made mistakes, the report spread blame thinly across supervisors, monetary authorities, ratings agencies, investors, and even savers themselves.Footnote 77 It formulated a set of forty-eight primary recommendations in several sub-fields: governance, risk, remuneration, and shareholder structures. Contra British alternatives, which explicitly cited systemic security, these were self-imposed measures designed to change management cultures, with a goal of restoring public trust in the system rather than explicitly tackling the too-big-to-fail problem. Measures would apply to all NVB members, and included the globally unprecedented “Banker's Oath” and “Banking Code,” which compelled individuals to swear to behave ethically, declare risky investments, and placed a cap of 100 percent on bonus remuneration for all bank employees. This formalized an ongoing “gentleman's agreement” between Finance Minister Wouter Bos and the leading banks that saw them voluntarily waive bonuses during the crisis.Footnote 78 A “comply or explain” principle compelled banks to offer a good explanation in the event that they could not uphold these standards, but stopped short of enshrining punishments with pre-determined legal sanctions.Footnote 79 In its focus on changing bankers, the Maas Report conspicuously did not broach bank structures. Even harsher capital requirements, such as a new counter-cyclical buffer, are discussed only in chapter 3, and so would not have been considered mandatory.

The Banking Code was swiftly pushed through parliament in a 2009 fait accompli between the governing CDA and PvdA coalition, entering force in January 2010, prior to the election. Dissenting voices were peripheral throughout this period, and through the June 2010 general election cycle, which ran in parallel to the British vote, no major Dutch political party pushed a regulatory reform agenda with concrete ambitions beyond restoring trust in the sector. Instead, the leading CDA, VVD, and PvdA parties competed almost exclusively over fiscal policy and austerity.Footnote 80 While the British debate over economic responses to the crisis featured both financial regulation and public finances, in the Netherlands, the latter eclipsed the former. Parties were ambiguous about precise regulatory initiatives, calling for pan-European cooperation and, in the case of the CDA, endorsing the Banking Code. With each of these major parties having presided over legacy regulations in the preceding years, there was no attempt to attribute blame to rival parties or regulators, and each of the three largest parties failed to propose reforms beyond the Maas prescriptions.

However, with the crisis still ongoing, the legislature had concurrently considered banking reforms through the De Wit Committee, formed in June 2009. This was an all-party parliamentary body, comprising eight members, one from each of the eight largest parties, and led by Jan de Wit of the Socialist Party (PS), who was elected to the role on account of his reputation as an open-minded and fair arbiter unlikely to be in thrall to the banks.Footnote 81 De Wit's work was divided into two cycles, the first examining the causes of the crisis and recommending regulatory responses; the second offering a critical appraisal of the government's role in securing the system throughout. The first report, entitled “Credit Lost” (Verloren Kredit), was compiled after thirty-nine interviews with academics, industry representatives, regulators, and politicians through January–February 2010. The committee worked with academics from Utrecht University to conduct a detailed analysis of potential regulatory responses, and also hired a team of expert support staff, including civil servants, lawyers, and economists to aid in the production of the final report.Footnote 82 This resulted in a broad selection of up to twenty recommendations, which, although less numerous than the Maas Committee's, included more radical departures from legacy regulations.

The De Wit recommendations endorsed Maas’ calls for a culture shift, yet it also made four proposals that went substantially further: the introduction of “unilateral” banking regulations, beyond European rules, if necessary; capital requirements above Basel III baselines; greater resources for regulators; and working with regulators to explore the feasibility of breaking up Dutch banks along either geographical or operational lines.Footnote 83 This assemblage of ideas has parallels with the positions of individual British parties, however, crucially in this case, De Wit simply put the proposals into the public domain, and there was no compulsion for any party to adopt them as a reform program. These ideas were, in turn, forcefully rejected by the NVB, which reaffirmed the thrust of the Maas reforms:

The banks have taken responsibility from the onset of the crisis and have shown self-reflection. They themselves have thoroughly investigated the causes of the crisis and have opted for better risk management, more expertise, more attention for the customer and a responsible remuneration policy with the Banking Code . . . [which] is unique and internationally normative.Footnote 84

The third element of the framework concerns coalition building dynamics as a by-product of the party system. In contrast to the UK, the 2010 Dutch election itself led to protracted negotiations, lasting five months, where multiple attempts at coalition building repeatedly failed and Dutch politics had become dominated by an internal controversy within the CDA over whether it should enter coalition with the anti-immigrant PVV.Footnote 85 This thematic shift—coupled with the fading proximity of government formation to the subprime crisis—further negated the potential for political departures from the banks’ reforms. As figure 4 shows, explicit coverage of the subprime crisis faded rapidly through 2010 as the sovereign debt crisis around the European periphery took center stage. A window of opportunity, with the crisis still fresh in the public's minds, had apparently been missed.

After a unique “toleration agreement” established a VVD-CDA government assisted by the PVV, Finance Minister Kees-Jan de Jager (CDA) focused primarily on augmenting Maas, making the Banking Oath mandatory, rather than pushing the agenda into any of the areas presented by De Wit. At no point during the 2010–12 parliament was the issue of structural regulation seriously on the reform agenda, with the issue eclipsed by debates over code and oath terms and the Eurozone crisis. However, despite declining coverage as per figure 4, these soft measures had done little to inspire the sort of consumer confidence the NVB was hoping for, and trust in the banking sector had not been restored. Survey data later indicated that a plurality of bank customers thought of the oath as a “political means to regain trust in the sector” while a majority of bank employees themselves considered it a “meaningless gesture.”Footnote 86 Meanwhile, special questions added to the annual Dutch Household Survey between 2008 and 2013 highlighted an overall decline in trust in the capacity of the central bank as supervisor; a decline in consumers’ faith in the liquidity situation of their own banks; and a linear year-on-year growth in consumers thinking that their bank might fail.Footnote 87

The lack of discussion over the too-big-to-fail problem in favor of the targeting of “culture” with oaths, codes, and bonus levies had clearly not achieved the banks’ and government's stated aims of restoring confidence through 2012. In response to this domestic concern and overarching European initiatives, the outgoing De Jager formed the Wijffels Commission, a thirteen-member body comprising academic experts and consumer advocates, which had a remit closely paralleling the ICB's in the UK. Named for its chair, the widely-respected economist and Rabobank executive Herman Wijffels, the committee met monthly in the Hague throughout its nine-month tenure, and was tasked with examining competition, regulatory policy, and the sustainability of the “bancassurance” model utilized by the two crisis-hit Dutch GSIBs: ABN-Amro and ING.

Wijffels was initially suspended by the collapse of the government and the 2012 election, but was reconvened in September 2012 by new PvdA Finance Minister Jeroen Dijsselbloem under the auspices of the VVD-PvdA coalition government. Again, at a critical moment in the process, Dijsselbloem did not alter the original composition of De Jager's panel, and this led to structural regulation being sidelined by skeptics who outnumbered the reformists who broached it on the commission.Footnote 88 Ultimately, discussions were dominated by other considerations: what to do about nationalized banks (ABN-Amro and SNS Reaal), whether to push the Dutch leverage ratio above the Basel III baseline, and how best to diversify the concentrated mortgage market.Footnote 89 The final June 2013 recommendation on structural regulation was to aspire to pan-European implementation of the Liikanen reforms, which ultimately never arrived. According to one commissioner, this was an expedient compromise, “not because there was any real enthusiasm for [Liikanen], but we thought it was appropriate at the time.”Footnote 90 By this point, hypothetical European rules would likely have had little impact on the Dutch Big Three banks. As the report states, “the Dutch banks themselves have indicated, they will probably not be obliged with the current extent of their trading activities to separate them when this proposal is introduced.”Footnote 91 It went on to warn explicitly against following the ICB model, stating that operational costs would rise, profitability would fall, and Dutch companies would become reliant on foreign banks for capital, “which is not of interest to the Dutch economy.”Footnote 92 This concluded formal explorations of bank reform alternatives in the Netherlands.

In sum, the Dutch case demonstrates how party system effects consistently failed to present political challenges to the banks over reform. Dutch parties effectively outsourced reform agenda impetus to the banks per Maas, which held “default action” status thereafter. Though multiple policy alternatives were subsequently mooted and government policy was not widely popular, even successive attempts to address the issue—including the formation of the Wijffels Commission—did not prioritize reform and reinforced the Maas agenda. The British case differed strongly, with blame attribution over legacy governance leading to political competition and the articulation of distinct reform agendas, followed by swift post-election trade-offs by two opposition parties eager to enter office. The ICB was the direct offspring of the coalition agreement and a political commitment to reform, which translated into an operational remit to the same end. This, in turn, disrupted the traditional City-Treasury signaling nexus, scrutinizing cost projections, downplaying exit threats, and securing an incontrovertible political consensus around structural reform.

Conclusion

This paper has sought to develop a new framework for understanding financial regulatory policy, based not on partisan leanings, financial systems, or even primarily interest group activities, but instead the effects of party system dynamics. It posits a corrective to an implicit assumption that while business power is variable, its operations are unidirectional and ubiquitous, and that policymakers nested in different democratic environments might respond to interest group and voter stimuli in universal fashions. Drawing on two archetypal cases, I suggest instead that certain features of majoritarian and consensus political systems can lead to important differences in outlook between policymakers at formative stages in the policy agenda, most notably through election cycles under conditions of high salience. This, in turn, has implications for levels of influence interest groups may exercise. British and Dutch banks both wielded significant influence over regulatory policy in the run up to the crisis and presented a similar overhanging continuation of the too-big-to-fail problem after 2009, but while British parties agitated for their own reforms and devised a process that secured them, their Dutch counterparts did not, leaving a re-regulatory agenda championed by the banks themselves unchecked.

This paper represents a first cut, and the explanatory force and generalizability of this argument should be tested and refined across more countries corresponding to different democratic systems and in further regulatory policy arenas exposed to sudden exogenous shocks and flares of salience. In general terms, it echoes calls for scholars of banking and finance to recognize policymaking as a dynamic process, undertaken by actors operating in different structures, offering variable incentives and constraints.Footnote 93 Whether the British or Dutch regulatory approach will ultimately prove more robust remains to be seen, and this debate will likely only be settled at the onset of the next crash.