1. Introduction

Although the acquisition of past tense morphology (e.g. Imperfect and Preterit) is one of the most investigated areas in Second Language Acquisition (SLA) research, the role that lexical aspect plays in the acquisition of these forms in the second language (L2) remains currently under debate. The leading hypothesis, i.e. the Lexical Aspect Hypothesis (LAH) (Andersen, Reference Andersen and Meisel1986, Reference Andersen, Huebner and Ferguson1991; Andersen & Shirai, Reference Andersen and Shirai1994; Bardovi-Harlig, Reference Bardovi-Harlig2000), argues that certain form–meaning associations (i.e. telic–Preterit and atelic–imperfect) guide the emergence of past tense forms in L2 grammars.1 This hypothesis is especially relevant for the L2 acquisition of Spanish since temporal and aspect distributions (e.g. the Preterit/Imperfect contrast) are expressed through specific morphological forms in this language.

The validity of the LAH for the L2 acquisition of Spanish has not been satisfactorily demonstrated partly because of methodological issues affecting the design of the tasks employed (Camps, Reference Camps2005; Comajoan, Reference Comajoan2006; Montrul & Salaberry, Reference Montrul, Salaberry, Lafford and Salaberry2003; Salaberry, Reference Salaberry2008). There are two specific issues regarding the experimental design used in studies assessing the LAH which appear to be especially problematic. First, in some contexts the structure of a narrative (background and foreground) and the inherent aspectual properties of a predicate (telic and atelic) make opposite predictions regarding what morphological form (Preterit or Imperfect) is more likely to be used. Although this is potentially an ideal scenario in which to test the predictions of the LAH, such contexts are rare in naturally occurring discourse and therefore are difficult to test using uncontrolled narrative tasks. Second, because existing data have been elicited using either production or comprehension tasks only, studies using combined evidence from both types of tasks are not available. This is despite claims (e.g. Slabakova, Reference Slabakova2001) that data elicited through carefully designed experiments are necessary to achieve a full understanding of L2 speakers’ competence in this grammatical domain.

The current study provides new insights into the role that lexical aspect plays in the acquisition of Spanish as a second language by explicitly addressing these two methodological issues. We will show how the combination of a specially designed corpus of L2 Spanish and a comprehension task can provide more complete evidence of L2 learners’ linguistic competence regarding Spanish past tense morphology. Crucial in this study is the fact that the corpus of L2 Spanish has been built using three different oral elicitation tasks with increasingly controlled structure (personal interview, semi-controlled impersonal narrative and controlled storytelling task). These three tasks were administered to the same group of 60 learners of Spanish whose first language (L1) was English. Through the use of this specific methodology we are able to show that some effects of lexical class are indeed clearly visible in the personal narrative task, a task widely used in previous literature testing the LAH, but that this task alone cannot be used as definite evidence to support this hypothesis. In this paper we will present combined results which show that although certain verbal features (dynamicity in particular) seem to play a role from the earliest stages of acquisition, the learners targeted possess a more sophisticated knowledge of aspectual morphology in Spanish than that predicted by the LAH.

This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides the theoretical background on how aspect is represented in Spanish and introduces the principles of the Lexical Aspect Hypothesis. Section 3 discusses the motivation for the present study focussing on several methodological inconsistencies in previous research. Section 4 introduces the production study and the rationale for the three tasks employed. Results from these three tasks, and in particular those elicited in non-prototypical contexts, are discussed in this section as well. Section 5 introduces the comprehension study and discusses the results elicited by a sentence-context preference matching task. Section 6 discusses the results and their implications for both theorising and methodological debates in formal SLA research. Section 7 presents the conclusions.

2. Aspect marking in native and non-native Spanish

Aspect provides information about the temporal development of an eventuality including whether events are finished, about to start or in progress. In Spanish, these properties are grammaticalised in the past tense in morphological forms known as Preterit, when the interval of time during which the eventuality takes place is finished (perfective), and Imperfect, when referring to intervals of time that are still in progress and are unfinished (imperfective):

(1)

a. When Sue arrived (finished), my brother was cleaning (unfinished) the house.

b. Cuando Sue llegópret (finished), mi hermano limpiabaimp (unfinished) la casa.

The aspectual meaning of a sentence is also determined by the inherent lexical semantic properties of the verbal predicate (the verb and its complements) (Dowty, Reference Dowty1986; Smith, Reference Smith1991; Tenny, Reference Tenny1994; Verkuyl, Reference Verkuyl1993). For instance, events such as “break” or “build a castle” have inherent endpoints (are regarded as telic) in contrast to events such as “sleep” or “sing” which denote actions which do not involve a culmination point (regarded as atelic) (see Depraetere, Reference Depraertere1995; Smith, Reference Smith1991). The examples in (2) show how the same Spanish verb can be either telic or atelic and used with both Preterit (pret) and Imperfect (imp) morphology. Telic and atelic interpretations depend on the internal argument of the verb. The English translations indicate how this is expressed with different morphosyntactic means in English (morphological affixes on the verbs in (2a) and (2b), or periphrasis in (2c) and (2d)).

(2)

Because the aspectual interpretation of a verb is compositional (dependent on the whole VP and not just the verb), it is possible that the same verb can be interpreted as atelic in some contexts ((2a) and (2c)) but telic in others ((2b) and (2d)).Footnote 2 The examples above show that in Spanish the morphological form used can override the inherent aspectual value of events (atelic events with the Preterit in (2a) and telic events with the Imperfect in (2d)).

Four aspectual classes are typically distinguished according to the inherent aspectual properties of verbs: states (be, love), activities (walk, swim), accomplishments (paint a picture, draw a circle) and achievements (break, die) (see Vendler, Reference Vendler1967). States are events that do not require an input of energy, do not have an inherent endpoint and have no internal structure; activities are events that have duration but lack an inherent endpoint; accomplishments are events that have duration and an inherent endpoint and achievements are events that have an inherent endpoint but do not have duration (they are instantaneous). The distinction between these four classes is based on the interaction of three different features: telicity, dynamicity and duration (Andersen, Reference Andersen1989; Comrie, Reference Comrie1976; Smith, Reference Smith1991). Telic events (accomplishments and achievements) have inherent endpoints whereas atelic events (states and activities) lack inherent endpoints. Dynamic events (accomplishments, activities and achievements) have input of energy whereas non-dynamic events (states) lack input of energy. Finally, punctual events (achievements) happen instantaneously and have no duration.

The Lexical Aspect Hypothesis (LAH) (Andersen, Reference Andersen and Meisel1986, Reference Andersen, Huebner and Ferguson1991; Andersen & Shirai, 1996) is based on Vendler's four-way verbal categorisation and was proposed to explain observed patterns in the use of tense and aspect morphology by second language speakers. According to this hypothesis, inherent aspectual properties of verbs guide the acquisition of tense and aspect morphology on the basis that certain correlations between morphological forms and aspectual properties of verbs (i.e. perfective–telic and imperfective–atelic) are prioritised in learner grammars (see Bardovi-Harlig, Reference Bardovi-Harlig2000; Salaberry, Reference Salaberry2008, for extensive discussion on the role of the LAH in acquisition). More precisely, Imperfect and Preterit morphology are claimed to appear in a sequence of stages determined by the lexical properties of the verbal predicate so that perfective forms are expected to emerge with telic predicates (achievements and accomplishments) and spread to activities and finally to states later on. In contrast, imperfective forms are claimed to appear first with states and spread to activities and finally to accomplishments and achievements (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Expected pattern of spreading of Preterit and Imperfect forms across lexical classes.

The LAH assumes that the distribution of forms present in the input plays a fundamental role in the acquisition of aspect morphology based on both the Relevance Principle, i.e. learners will acquire the most relevant morphological form first (Bybee, Reference Bybee1985), and the Congruence Principle, i.e. learners will associate features which are semantically congruent such as telicity and perfectivity (Andersen, Reference Andersen, Hyltenstam and Virborg1993; Andersen & Shirai, Reference Andersen and Shirai1994; Shirai, Reference Shirai, Nakajima and Otsu1993, Reference Shirai, MacLaughlin and Ewen1995; Shirai & Kurono, Reference Shirai and Kurono1998). The LAH also assumes an association between lexical class and grammatical marking based on prototype theory (Rosch, Reference Rosch1973, Reference Rosch, Rosch and Lloyd1978) according to which each given category has its best exemplars, or prototypes, and a number of peripheral members, the non-prototypical exemplars, with fewer features in common. Shirai and Andersen (Reference Shirai and Andersen1995) argue that children first restrict the use of past tense morphology to the prototype of the category past (i.e. [+telic], [+punctual], [+result]) and restrict the use of progressive (which denotes the semantic features [+dynamic, −telic]) to activities and never to [−dynamic] predicates (i.e. states). In the case of L2 learners, it is hypothesised that learners would first associate one main meaning with each morphological form. These arguments assume the universality of the acquisition of perfective markers as children are said to show similar properties even if acquiring languages which encode aspectual distinctions in a different manner (although see Weist, Reference Weist1989, for contradictory evidence). This is consistent with proposals which have argued that certain semantic distinctions (e.g. state versus process and punctual vs. non-punctual) are biologically programmed and emerge early in acquisition (e.g. Bickerton's (Reference Bickerton1981) Language Bioprogram Hypothesis) and that both children and adults tend to favour the use of certain lexical and grammatical aspect combinations. For instance, it has been observed that properties such as telic (punctual), perfective and past on the one hand and atelic (durative), imperfective and present on the other, are natural form–meaning associations (Comrie, Reference Comrie1976) and that they cluster together as the result of non-linguistic cognitive constraints (see Wagner, Reference Wagner2010, for details). A large body of research has documented the existence of such prototypical combinations in children's early use of morphological forms, including studies examining Spanish-speaking children using both production (Jackson-Maldonado & Maldonado, Reference Jackson-Maldonado, Maldonado, Rojas and de León2001) and comprehension (Grinstead, Pratt & McCurley, Reference Grinstead, Pratt and McCurley2009). However, experimental data testing children's comprehension of non-prototypical associations have confirmed that children can appropriately prefer non-prototypical form–meaning pairings in certain contexts and corroborates that prototypical associations are only tendencies observable in production data (Wagner, Reference Wagner2010; Grinstead et al. Reference Grinstead, Pratt and McCurley2009). Taking this discussion into consideration we can summarise three main predictions of the LAH for L2 Spanish as follows:

1. Prototypical choices (i.e. perfective–telic and imperfective–atelic) are favoured over non-prototypical ones at the beginning of the acquisition process.

2. The perfective marker is used first on achievement and accomplishment verbs and spreads over all lexical aspectual classes as L2 experience increases.

3. The imperfective marker appears soon after the perfective marker is first used. Imperfective appears first with stative and activity (i.e. atelic) verbs and extends to accomplishment and achievement (i.e. telic) verbs.

Overall, aspectual morphology is expected to develop gradually and use of imperfective and perfective morphology is supposed to spread from the prototypical to the non-prototypical form–meaning combinations.

3. Motivation for the present study

Although research testing the predictions of the LAH in L2 Spanish is extensive (see overviews in Montrul & Salaberry, Reference Montrul, Salaberry, Lafford and Salaberry2003 and Salaberry, Reference Salaberry2008) the validity of this hypothesis for the acquisition of Spanish past tense forms has yet to be fully demonstrated. Some evidence supporting the predictions of the LAH does exist, mainly from studies primarily using (oral or written) production data elicited though the use of mostly uncontrolled narratives (Cadierno, Reference Cadierno2000; Camps, Reference Camps2005; Hasbún, Reference Hasbún1995; López-Ortega, Reference López-Ortega2000; Ramsay, Reference Ramsay1990). A common pattern of development observed in these data is that learners initially use present morphology in past tense contexts, followed by a stage where Preterit is the only past tense morphological marker produced though it is used for telic (accomplishments and achievements) predicates only. Finally, Imperfect emerges after the Preterit and is first used with state and activity verbs (see Hasbún, Reference Hasbún1995; Ramsay, Reference Ramsay1990, for relevant evidence and Comajoan, Reference Comajoan and Eddington2005, for discussion).

Some evidence against the LAH, however, has also been found. For instance, a number of production studies did not find support for the spreading of past tense across classes as predicted by the LAH (Bergström, Reference Bergström1995; Camps, Reference Camps2002; González, Reference González2003; Lubbers-Quesada, Reference Lubbers-Quesada and Buck2007; Salaberry, Reference Salaberry1998; Tracy-Ventura, Reference Tracy-Ventura2008), with some studies suggesting that the dynamic class as a whole (including atelic activity events) has a developmental pattern which is different from that of states (Bergström, Reference Bergström1995; Housen, Reference Housen, Vet and Vetters1994; Lubbers-Quesada, Reference Lubbers-Quesada and Buck2007; Salaberry, Reference Salaberry1998, Reference Salaberry1999, Reference Salaberry, Salaberry and Shirai2002). Shirai (Reference Shirai and VanPatten2004) also argues that Imperfect may not be subject to the same stage-like development as expected for the Preterit, i.e. spreading from atelic to telic predicates would not occur for the Imperfect. Other studies have also reported that perfective morphology does not emerge with achievement predicates exclusively and is used with other aspectual predicates as well (Bergström, Reference Bergström1995; Camps, Reference Camps2002; Comajoan, Reference Comajoan2001; Salaberry, Reference Salaberry2000).

Salaberry (Reference Salaberry1999, Reference Salaberry, Salaberry and Shirai2002, Reference Montrul, Salaberry, Lafford and Salaberry2003) conducted a series of studies examining the validity of the LAH in L2 Spanish with groups of L1 English university students learning Spanish at different proficiency levels. Overall, the findings of these studies converge in showing that learners seem to use the Preterit as a default marker of past tense during early stages of acquisition. Although some Imperfect was used with state verbs, the use of Preterit was associated with all verb types to a much higher extent than Imperfect (see Salaberry, Reference Salaberry2008, for an in-depth overview of these findings). A second important finding in Salaberry's studies is that when L2 speakers eventually abandon the Preterit as a default marker of past tense, they then start taking lexical class into consideration when choosing to use either Imperfect or Preterit. Salaberry also found that learners seem to rely on this association more radically than Spanish native speakers. Overall, these results seem to indicate that lexical class is relevant for learners at more advanced stages of acquisition, in contrast to the LAH, which predicts learners’ sensitivity to lexical class from very early on.

Furthermore, comprehension studies examining learners’ interpretation of imperfective and perfective forms have shown that persistent problems can be caused by the semantic properties associated with the Spanish Imperfect which may be used to express habituality, progressivity or neither of these – e.g. a continuous reading – (see Arche, Reference Arche2006) even after knowledge of the morphological forms is attested (Domínguez, Arche & Myles, Reference Domínguez, Arche, Myles, Danis, Mesh and Sung2011; Montrul & Slabakova, Reference Montrul and Slabakova2003; Slabakova & Montrul, Reference Slabakova and Montrul2003). If the complete acquisition of past tense forms involves acquiring new and specific interpretations for each of the two morphological markings, studies using comprehension (as well as production) data are then necessary to provide comprehensive evidence in this grammatical area. This is especially critical since any Preterit–telic and Imperfect–atelic associations found in comprehension data could be used as evidence supporting the LAH as well.

There are several possible explanations for the lack of agreement in the results discussed in these studies. Amongst them is the difficulty involved in assessing the complete LAH empirically as this hypothesis can actually be decomposed into a series of different assumptions about both the emergence and spreading of Preterit and Imperfect forms. For example, studies may find evidence supporting the expected pattern of (first) emergence of each form, but not the eventual spreading of each form across classes. As a consequence, what constitutes evidence for or against the LAH is not completely straightforward. Bardovi-Harlig (Reference Bardovi-Harlig2000, p. 266) suggests that a study that shows equal distribution of verbal morphology across classes (that is, use of Preterit and Imperfect emerging with all verbs) should be considered as such counterevidence. However, such a pattern may be especially difficult to attest if evidence is only available from a single production task.

In fact, it has already been argued that the type of task plays a relevant role in eliciting the form–meaning associations predicted by the LAH.Footnote 3 For instance, Bardovi-Harlig (Reference Bardovi-Harlig2000, Reference Bardovi-Harlig, Kempchinsky and Slabakova2005) argues that frequently used tasks seem to be biased to elicit Preterit forms, as they do not provide enough background contexts (exactly the contexts in which Imperfect naturally occurs). This unequal distribution is particularly relevant for story retelling tasks and personal narratives, as discussed in Camps (Reference Camps2002, Reference Camps2005), Liskin-Gasparro (Reference Liskin-Gasparro2000) and Salaberry (Reference Salaberry2003). In addition, Shirai (Reference Shirai and VanPatten2004) also argues that studies utilising paper-based tests, such as cloze or fill-in-the-blank tests, support the prediction of the LAH more consistently.

Another methodological problem relates to the observation that the prototypical punctual–telic–Preterit (El chico empezó a comer/The boy started to eat) and durative–atelic–Imperfect (María andaba/Mary was walking) associations predicted to occur by the LAH, are frequent in native natural speech, whereas non-prototypical associations are not and are therefore unlikely to be elicited through free narrative L2 tasks (interviews, story retelling, etc.). Such tasks, therefore, are often unsuccessful at providing full and convincing evidence about the L2 development of past tense form-to-meaning associations (see Slabakova, Reference Slabakova2001, for discussion). For this reason eliciting evidence using a task that includes naturally infrequent but appropriate Preterit–atelic (Maria anduvo/Maria walked) and imperfect–telic (El chico empezaba a comer/The boy was starting to eat) contexts is necessary as well.

A further complication is that a number of other factors (input frequency, L1 influence, learner characteristics, etc.) have been found to play a part in the emergence and development of L2 morphology (see discussion in Shirai, Reference Shirai and VanPatten2004). One factor which has received extensive attention is the influence of discourse structure, in particular notions such as foreground and background (Dry, Reference Dry, Hwang and Merrifield1992; Fleischman, Reference Fleischman1990; Givón, Reference Givón and Tomlin1987; Reinhart, Reference Reinhart1984). It has been proposed that the distribution of temporal-aspectual forms can be determined by discourse grounding in narratives (Bardovi-Harlig, Reference Bardovi-Harlig1992, Reference Bardovi-Harlig1995, Reference Bardovi-Harlig1998; Bergström, Reference Bergström1995; Kumpf, Reference Kumpf, Eckman, Bell and Nelson1984; Reid, Reference Reid1980; Smith, Reference Smith, Kempchinsky and Slabakova2003; Wallace, Reference Wallace and Hopper1982). Specifically, perfective marking is expected to be associated with the foreground of the discourse (i.e. the skeleton that carries the sequence of events taking place), whereas the imperfective should appear with those forms constituting the background (scene setting), regardless of their lexical aspect properties (Bardovi-Harlig, Reference Bardovi-Harlig, Gass, Cohen and Tarone1994). A number of studies have already corroborated that discourse structure can affect the choice between Imperfect and Preterit in an L2 (Comajoan, Reference Comajoan2001, Reference Comajoan and Eddington2005; Giacalone-Ramat, Reference Giacalone-Ramat, Salaberry and Shirai2002; Housen, Reference Housen, Vet and Vetters1994; López-Ortega, Reference López-Ortega2000; Noyau, Reference Noyau and Dechert1989, Reference Noyau, Salaberry and Shirai2002; Salaberry, Reference Salaberry2011; Veronique, Reference Véronique and Pfaff1987). Once again, this shows that having access to multiple sources of evidence, especially those which include different discourse structures, is crucial when investigating the acquisition of this grammatical area.

In summary, a review of the existing literature has shown that evidence supporting the Lexical Aspect Hypothesis in the L2 acquisition of Spanish past tense morphology remains inconclusive. This is partly due to the choice of methodology employed in previous research. We argue that combining varied research methods, including tasks to elicit past tense forms in non-prototypical contexts, is necessary in order to provide more conclusive evidence on the validity of this hypothesis in L2 Spanish. The next sections present two new studies which re-examine the validity of the LAH for the acquisition of L2 Spanish Preterit and Imperfect taking into consideration the methodological points just raised. The first study analyses data from a new oral learner corpus specifically designed to examine whether lexical aspect affects the use of these forms in both prototypical and non-prototypical contexts. The second study analyses new comprehension data collected from the same learners in order to offer complementary evidence on the status of aspectual L2 morphology in L2 grammars.

4. The production study

4.1 Predictions

In line with previous research our predictions focus on both the patterns of emergence of Imperfect and Preterit forms as well as their distribution of use across the four lexical aspect classes. We hypothesise that if the telic/atelic distinction guides learners’ development of Spanish Imperfect and Preterit morphology, (as predicted by the LAH), the Preterit would emerge before the Imperfect and would emerge with achievements first spreading to the other telic class (accomplishments) then to activities and finally to states. On the other hand, Imperfect would be expected to emerge after the Preterit and would be used with states first, spreading to the other atelic class (activities), then to accomplishments and finally to achievements. This is a straightforward examination of the predictions of the LAH in L2 Spanish.

Crucially, the methodological approach followed in this study allows us to make further predictions and test the validity of the LAH in a wider variety of contexts. These contexts include non-prototypical situations, those which directly contradict the predictions of the LAH, in which narrative grounding biases the use of Preterit with atelic verbs and the use of Imperfect with telic verbs. We hypothesise that if the LAH is valid in L2 Spanish, the type of form–meaning associations expected by this hypothesis (telic–Preterit and atelic–Imperfect) would still be observable in the non-prototypical contexts tested in our study and from early on. In contrast, if we find evidence that L2 Spanish speakers are able to produce non-prototypical form–meaning associations this would indicate that learners’ aspect marking in Spanish is not exclusively reliant on the telic/atelic distinction assumed by the LAH.

4.2 Participants

As Table 1 shows, 60 learners were identified for the project through visits to schools, colleges and universities in different parts of England. Samples of spoken Spanish produced by native speakers of ages similar to the L2 learners (five samples at each age level) were included as well.

Table 1. Participants.

Learners were divided into three groups according to their proficiency levels (beginners, intermediate and advanced) corresponding to three different education levels in the English school system: lower secondary school (Year 10, or Y10), upper secondary school final year (Year 13, or Y13), and university undergraduates (UG) during the final year of their Spanish BA degree. The team collected details of learners’ linguistic and educational background through a self-evaluation questionnaire. Only monolingual participants who had started learning Spanish at around 11 years of age (two years before the time of testing for the beginner students) and declared Spanish as their main foreign language were included in the study. The advanced speakers were final year undergraduate students who had spent a year studying abroad in a Spanish-speaking country. The three groups were chosen to represent three key language learning stages in a typical British instructed setting.

4.3 Task design

A survey of tasks used in previous research was conducted and possible task types were identified before the final three production tasks were developed. Tasks were also piloted with both native speakers and a sample of speakers of equivalent level to each learner group. The oral data were collected using three especially designed tasks: one impersonal narrative (Cat Story), one controlled narrative (Las Hermanas), and one personal narrative (elicited as part of a semi-structured interview).Footnote 4Table 2 shows relevant details of the oral tasks included in this study.

Table 2. Oral elicitation tasks included in the current study.

The impersonal narrative (Cat Story) task was designed to elicit the use of past tense forms through the retelling of a short story. Participants looked at a series of pictures and were asked to tell the story to the experimenter. The task included just two written prompts in order firstly to provide habitual/imperfective contexts (“Todas las mañanas eran iguales” “Every morning was the same”), and secondly to provide a one off/perfective context (“Hasta que un día. . .” “Until one day. . .”).

The impersonal controlled narrative (Las Hermanas) was specifically designed to test learners’ use of less frequent form-to-meaning associations. Eight contexts were created resulting from the combination of two variables: lexical aspect class (states, activities, accomplishments and achievements) and discourse grounding (foreground and background). Four of those contexts involved prototypical pairings of discourse grounding and lexical class (e.g. states in the background or achievements in the foreground). The other four contexts were designed to elicit non-prototypical pairings (e.g. states in the foreground or achievements in the background). A total of 25 target verbs, selected according to their inherent aspectual properties (see Table 3) were used to create a story about two sisters who took a trip to Spain. The story thus offered several examples of each context type.

Table 3. Verb types targeted in Las Hermanas task.

In order to promote inclusion of non-prototypical (telic–Imperfect and atelic–Preterit) contexts, a series of illustrations for the story were designed with the help of an artist and presented to the learners. The target verbs were provided (in the infinitive) underneath each picture; participants were asked to use these verbs while telling the story, and were free to add more information if necessary.

The personal narrative (administered within a semi-structured interview) was the least controlled task, as learners were free to talk about memories from their childhood and their upbringing. Experimenters were coached to use specific questions to elicit both the Imperfect (e.g. “What did you use to do when you spent time with your grandparents?”) and Preterit (e.g. “What did you do last weekend?”).

4.4 Data collection and analysis

The oral data were collected by trained members of the research team following uniform elicitation protocols for each task. All speech was audiorecorded using portable digital equipment. The soundfiles generated by the oral tasks were transcribed using CHILDES/CHAT transcription conventions (http://childes.psy.cmu.edu). Once each transcript was checked for accuracy, the soundfiles and transcripts were fully anonymised in preparation for public dissemination.Footnote 5 Part of speech (POS) tagging of the CHAT transcripts using the Spanish MOR and POST programs was then carried out. Data from all tasks were coded for lexical aspect, discourse structure (background and foreground) and forms produced (PRET(erit), IMP(erfect), PRES(ent), etc.) which, in turn, were also coded for appropriateness (CORR(ect) or INC(or)R(ect)).Footnote 6 These parameters were incorporated in each CHAT transcript as an extra tier of tagging (%VCX), which enabled the automatic analysis of various aspectual and discursive features (e.g. lexical aspect class, obligatory context, morphological form and discourse structure). The patterns of use (frequency of each form in each context) for each learner group were also analysed using further programs written by the research team.

4.5 Combined results from the three oral tasks

Overall, the results obtained by the three oral tasks show that 85% (17/20) of the Y10 learners were able to produce at least one past tense form (either Preterit or Imperfect) in the personal narrative task (the least controlled task) and 75% (15/20) did so in the impersonal narrative (Cat Story) task. One Y10 learner did not produce any Preterit in the personal narrative, and four learners (20%) did not use this form in the Cat Story task. In contrast, 40% (8/20) of the Y10 learners did not use any Imperfect forms in the personal narrative and 35% (7/20) did not produce it in the Cat Story. This result shows that 40% of beginner learners start using Preterit before Imperfect, a result which is congruent with previous findings which have also shown that Preterit usually emerges before Imperfect in L2 grammars. It also shows that the personal narrative task elicited the most past tense forms at beginner level, supporting previous findings as well. In contrast, 100% of the Y13 (intermediate) learners used at least one Preterit or one Imperfect form in both Cat Story and personal narrative, and only one learner did not produce any Imperfect in either of these two tasks.

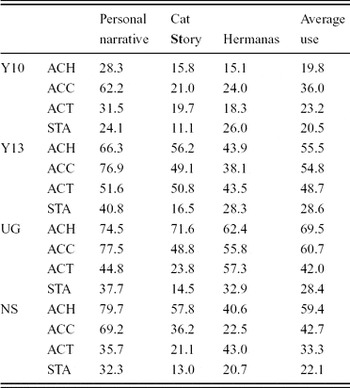

The average use of Preterit and Imperfect forms for each lexical class (achievements, accomplishments, activities and states) was obtained for each of the three oral tasks (Las Hermanas, Cat Story and personal narrative).Footnote 7 These results are shown in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 4. Percentages of use of Preterit forms in each task and lexical class.

Y10 = Year 10; Y13 = Year 13; UG = Undergraduates; NS = Native speakers;

ACH = Achievements; ACC = Accomplishments; ACT = Activities; STA = States

Table 5. Percentages of use of Imperfect forms in each task and lexical class.

Y10 = Year 10; Y13 = Year 13; UG = Undergraduates; NS = Native speakers;

ACH = Achievements; ACC = Accomplishments; ACT = Activities; STA = States

A Poisson generalised linear model was used to determine how the rate of use of the Preterit (as opposed to the Imperfect tense) depends on the Proficiency of the subjects, the Lexical Class used and the type of Task carried out. The resulting ANOVA table (Table 6), can be used to determine the significance of the explanatory variables. It shows that all the variables and all of the second-order interactions are significant i.e. there is a significant interaction between each pair of variables. This is the case regardless of the order of the fitting of the variables. This means that both Lexical Class and Task Type have a significant effect on the likelihood that each group uses Preterit or imperfect. We can also see that the type of task determines the use of Preterit and Imperfect with a particular class because the interaction between Task and Lexical Class is significant (p < .001, see last line of Table 6).

Table 6. Significance of the explanatory variables.

The results for the Y10 group (see Figure 2) show that learners use Preterit with accomplishment verbs (36%) more than with any other class, including achievements (19.8%), due to the high number of instances of the verb ir “go” produced by this group of learners. This group of speakers uses the Preterit with the same frequency for all other classes (i.e. a Tukey post-hoc test shows that only the difference in use between accomplishments and achievements (p = .001) and between accomplishments and activities (p = .005) was significant). In clear contrast with the predictions of the LAH, there were no differences between the use of Preterit in states and achievements (p = .8). The use of imperfect, although very low, is significantly higher for states (15.71%) than for any of the other three classes including activities (p = .002), where the use is rather low (3.6%). However, learners used the Preterit with states more often (20.5%) than the Imperfect (15.7%), a result which is not predicted by the LAH either. The difference in use between these two forms is not significant (p = .33), which shows that although Imperfect is preferred with states more often than with any other class, Preterit is used with states with similar frequency.

Figure 2. Average use of Preterit and Imperfect in the three oral tasks for beginner learners.

The results for the Y13 intermediate group show a clear increase in the use of Preterit and Imperfect forms (see Figure 3). This increase is especially pronounced for state verbs. Y13's use of Preterit is significantly higher than the use of Imperfect for all classes (including activities) except for states where Imperfect was used more frequently (40.6%) than Preterit (28.6%) (the difference approaches significance: p = .06). The most interesting result is that this group is more likely to use Preterit if the verb is an achievement, an accomplishment or an activity (i.e. if the verb is [+dynamic]) than if it is a state. Similarly, this group is more likely to use the Imperfect if the verb is a state ([–dynamic]) than if it is an event. This result is, again, in clear contrast with the expected spreading of use of these forms across lexical classes suggested by the LAH and shows that telicity does not affect the pattern of use of Preterit and Imperfect for this group.

Figure 3. Average use of Preterit and Imperfect in the three oral tasks for intermediate learners.

The results for the UG (advanced) group reveal the first observable effects of lexical class (telicity in particular) in the use of Preterit and Imperfect as the average use differs significantly across most of the classes (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Average use of Preterit and Imperfect in the three oral tasks for advanced learners.

The use of Preterit is higher with achievements (69.5%) than with any other class and decreases to 60.7% with accomplishments, 42% with activities and 28.4% for states. All differences are significant except for that between the telic classes (achievements and accomplishments: p = .18). Similarly, the Imperfect is only used 16.7% with achievements and 24.2% with accomplishments (the two telic classes) whereas its use increases to 30.1% with activities and 58.3% with states, as also predicted by the LAH (although the difference between accomplishments and activities for the use of Imperfect is not significant: p = .23). In contrast to the other two learner groups, the use of Imperfect is for the first time significantly higher than the use of Preterit for states (p < .001).

The reported pattern of use of Preterit (Preterit is most frequently used with telic events and least frequently used with atelic events) is also observed in the results obtained by the native group (see Figure 5). However, even though the difference in use of Imperfect with achievements and states is highly significant (p < .001), no significant difference was found between accomplishments and activities (p = .54). Furthermore, the use of Preterit and Imperfect is not significantly different for accomplishments (p = .82) and activities (p = .15) showing that native speakers did not prefer one of these forms significantly more often for these two classes.

Figure 5. Average use of Preterit and Imperfect in the three oral tasks for native controls.

Overall, these results indicate that the combined use of Imperfect and Preterit for each of the lexical classes in the three oral tasks shows clear differences between the beginner and Y13 learners on the one hand, and the advanced learners and native controls on the other. While intermediate and beginner learners do not show the spreading pattern expected by the LAH for either of the two forms, the other two groups do show a pattern which seems consistent with this hypothesis especially for the most prototypical classes (achievements and states).

4.6 Use of Imperfect in non-prototypical contexts

In contrast to previous studies, the results reported in our study include those elicited by a controlled narrative (Las Hermanas) designed to push learners to produce Imperfect and Preterit forms in non-prototypical contexts. Therefore, it is important to examine how far this task influenced the use of these two forms. Next, a comparison is presented between the results obtained by this task and those obtained from the personal narrative and the Cat Story.

The results show striking differences. Figure 6 (native controls) and Figure 7 (advanced L2 speakers) demonstrate how these two groups used the Imperfect according to the pattern predicted by the LAH for the four lexical classes in the personal narrative and Cat Story tasks. In contrast, Las Hermanas was successful in altering this pattern in both groups and eliciting higher use of the Imperfect with telic classes and lower use with atelic classes.

Figure 6. Use of Imperfect according to four lexical classes in two tasks (native controls).

Figure 7. Use of Imperfect according to four lexical classes in two tasks (advanced learners).

These results allow us to see that the use of Imperfect by native speakers, as well as by advanced L2 speakers, only follows the predicted pattern of the LAH if the type of narrative context is not controlled. The following examples illustrate the use of Preterit with atelic verbs (examples (3) and (5)) and Imperfect with telic verbs (examples (4) and (6)) in the Las Hermanas task by one intermediate (Y13–50) and one advanced learner (UG-75):

(3) De repente en tren [había un gran revuelostate–imp] [creyeronstate–pret] que había un problema y Gwen [/] Gwen [sintió agua de lluviastate–pret] um [necesitió ayuda del revisorstate–pret].

(Y13-50)

“Suddenly on the train there was a big commotion. They thought there was a problem and Gwen felt raindrops um she needed help from the conductor.”

(4) Gwen de niña [leía un libroaccomp–imp], [pintaba un cuadroaccomp–imp] y [escribía un cuentoaccomp–imp] cada fin de semana. Durante la semana [se despertaba tempranoachiev–imp] y [terminaba sus deberesachiev–imp] temprano también.

(Y13-50)

“Gwen when she was a child would read a book, paint a picture, write a story each weekend. During the week she used to wake up early and used to finish her homework early too.”

(5) Y de repente en el tren mientras que [hablaba sobre su niñezactivity–imp] [hubo un gran xx revuelostate–pret]. Los dos [creyeronstate–pret] que había un problema.

(UG-75)

“And suddenly while they were talking about their childhood there was a big commotion. Both thought that there was a problem.”

(6) Gwen de niña cada fin de semana [leía un libroaccomp–imp], [pintaba un cuadroaccomp–imp] [escribía un cuentoaccomp–imp] y durante la semana [se despertaba tempranoachiev–imp].

(UG-75)

“Gwen when she was a child each weekend would read a book, paint a picture, write a story, and during the week she would wake up early.”

It is interesting to note how despite the fact that advanced speakers produced slightly fewer Imperfect forms with activities in Las Hermanas (27%) than in the other two oral tasks combined (31%), their use of Imperfect with states was hardly altered between tasks (59% produced in the personal narrative and Cat Story and 57% produced in Las Hermanas), but it was for the native speakers (72% compared to 53%). This result is revealing of the strength of the Imperfect–state association already observed in the oral data discussed in the previous section.

The results for the intermediate group (see Figure 8) also show a modified pattern of responses in non-prototypical contexts. However, and similarly to the advanced group, the use of Imperfect with states was similar in both sets of tasks (42% in personal narrative and Cat Story and 38% in Las Hermanas) and this was observed for activities (21% in personal narrative and Cat Story and 22% in Las Hermanas) as well.

Figure 8. Use of Imperfect according to four lexical classes in two tasks (intermediate learners).

Overall, these results highlight the resilience of the Imperfect–state association in the grammar of these speakers. The results from the beginner group, which are shown in Figure 9, indicate that this association is observable from the earliest stages of acquisition. As we see in Figure 9, this group prefers to use Imperfect with states in both sets of tasks. In fact, the use of Imperfect was highest in Las Hermanas (18%).

Figure 9. Use of Imperfect according to four lexical classes in two tasks (beginner learners).

Overall, the results from this study can be taken as evidence that a strong Imperfect–state association guides the use of this form by L2 Spanish speakers from early on, and that the overall distribution of use of both Preterit and Imperfect cannot be fully accounted for by the LAH. This is particularly the case when we consider that the pattern of spreading across classes predicted by this hypothesis was not attested in our beginner and intermediate data. Although advanced speakers did show a pattern mostly consistent with the LAH, the fact the same pattern was observed for the native group raises the question whether the spreading across classes is in fact revealing of a developmental route, or whether such a pattern merely reflects form–meaning associations which are frequent in the target language.Footnote 8 The comparison between the results from the uncontrolled production tasks and Las Hermanas allows us to see that the latter possibility is more likely, as the particular distribution across classes is observed in the native data as well and in the two uncontrolled tasks only. Crucially, intermediate and advanced learners show that they are capable of using Imperfect with telic verbs in appropriate contexts as shown by the results of our controlled narrative task (Las Hermanas). This result suggests that these learners are already sensitive to changes in discourse structure and grounding, a factor which can affect the use of Preterit and Imperfect forms (Bardovi-Harlig, Reference Bardovi-Harlig, Gass, Cohen and Tarone1994, Reference Bardovi-Harlig1995).

4.7 Summary of results

The results of the oral production study have shown that beginner learners preferred the use of Preterit over Imperfect when speaking about a past tense event, a result which seems consistent with Salaberry's (Reference Salaberry1999) “Default Past Tense Hypothesis”. This hypothesis argues that the initial stage of development of past tense forms is characterised by an overgeneralisation of the Preterit across verb classes (including states) as the result of L1 transfer. Although our results show, consistent with Salaberry's hypothesis, that the use of the Preterit is widespread in early stages of acquisition, our study also shows that these learners use the Imperfect significantly more often with states than with any other type of verb. Our results seem to indicate that beginner learners do appear to be sensitive to one lexical property, dynamicity (i.e. whether the event is a state or not) when producing Preterit and Imperfect forms. One crucial finding to support this observation is that the use of Imperfect is clearly more frequent with states than with any of the other classes across all tasks, even in the controlled narrative task which was designed to force learners to use Preterit with states and Imperfect with events in non-prototypical contexts. In this task learners still preferred to use imperfect, instead of Preterit, with states in foreground contexts (i.e. this was the only lexically-determined association which was not affected by grounding effects).

Our results regarding the use of Imperfect are consistent with previous studies which have also shown evidence against the spreading of Imperfect across classes (Bergström, Reference Bergström1995; Salaberry, Reference Salaberry1998, Reference Salaberry2000; Shirai, Reference Shirai and VanPatten2004). Furthermore, and in clear contrast to the predictions of the LAH, both Preterit and Imperfect were used with the same frequency with state verbs by the least proficient learners. In Section 3 we discussed how deciding what can or should be used as evidence against the LAH is not completely straightforward due, amongst other reasons, to a large number of outcomes to be tested. In this respect, we agree with Bardovi-Harlig (Reference Bardovi-Harlig2000) in assuming that an equal distribution of verbal morphology across classes could be used as a significant piece of counterevidence. This supposition is corroborated by our findings and in particular by the results of the less proficient groups (exactly the groups for which the effects of the LAH should be most evident). In the light of all these results, we have enough evidence to argue that a pattern of emergence and development of past tense forms across different lexical classes consistent with the LAH is not supported by our corpus of oral data.

5. The comprehension study

An online sentence–context preference matching task (SCMT) was designed to examine whether the predictions of the Lexical Aspect Hypothesis can be extended to the acquisition of the different interpretations associated with the Spanish Imperfect (habitual, continuous and progressive) and Preterit. In particular the aim of this study is to examine whether learners know that the use of past tense forms is influenced by context, and whether state–Imperfect and event–Preterit associations, as observed in the production data, guide learners’ choices in this task as well.

5.1 Predictions

Two different sets of contexts were identified in this task: Imperfect (including habitual, progressive and continuous actions) and one-time events (finished actions that only occurred once). Two types of verbs (events and states) were included in the task. In the Imperfect context, it is expected that learners will accept the sentence with Imperfect morphology and reject the sentence with Preterit, regardless of the type of verb. In the one-time-event context, the reverse pattern is expected (high acceptance scores for Preterit and low acceptance scores for imperfect). These predictions are proposed under the assumption that whether the verb is an event or a state plays no role in the acquisition of these forms.

In contrast, any differences in responses across verb types would indicate an influence of dynamicity (the feature which explains the stative/eventive distinction). In particular, if learners are sensitive to the [+/–dynamic] distinction they would tend to accept the Imperfect more often with states than with events and would tend to reject the Preterit with states more often than with events. Crucially, in one-time-event contexts we should find evidence of higher acceptance of the Preterit with event verbs than with states and higher rejection of the Imperfect with events than with states.

5.2 Participants

The same 60 learners who participated in the production study took part in the comprehension study. The control group was formed by a group of 15 native speakers of peninsular Spanish.

5.3 Task design

Two sets of variables were included in the task design: type of predicate (eventive or stative) and type of context (one-time event, habitual, progressive, and continuous). These were combined to produce 32 different test items (see Table 7).Footnote 9

Table 7. SCMT design.

The participants were asked to rate the appropriateness of a pair of (Imperfect/Preterit) sentences in a particular context using a five-point Likert scale (–2, –1, 0, +1, +2). Each context was carefully biased toward either the sentence with Preterit (depicting one-time-event actions) or the sentence with imperfective morphology (depicting continuous, habitual, or progressive actions). We are aware that the decision to use English in the description of the situations could have influenced learners’ judgements in this task. However, we are not entirely sure that introducing the context in Spanish would have been problem-free either as learners could have based their choices on the Spanish forms available in the descriptions. In the end, due to the wide range of L2 proficiencies of our participants, we were forced to introduce the situations in the learners’ native language to ensure that the less experienced Spanish speakers (the beginner group) could perform this task.

Example (7) illustrates a sample test item where the introductory context represents a habitual action. Sentence (7b), with imperfective morphology, is appropriate in this context.

(7) When Ana was a child she had a very close friend, Amy, and she liked to spend a lot of time at her house after school.

a. Ana estuvopret mucho en casa de Amy al salir del colegio. (inappropriate)

“Ana was in Amy's house a lot after school.”

b. Ana estabaimp mucho en casa de Amy al salir del colegio. (appropriate)

“Ana used to be in Amy's house a lot after school.”

The responses given by each participant were counted and the mean average of each chosen option in each experimental condition was calculated. Mean values were then transformed into percentages. Two types of statistical analyses, within and between groups, were carried out using paired-samples t-tests for the former and a one-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc tests for the latter.

5.4 Results

The results of this study are summarised in Figures 10 and 11. Figure 10 shows the average ratings for both input sentences (with Preterit and Imperfect morphology) in contexts where Imperfect is the appropriate form (i.e. contexts depicting habitual, continuous or progressive actions in the past). Figure 11 shows the average ratings for the two input sentences in contexts where the Preterit is the appropriate form (i.e. contexts depicting one-time events in the past). The beginner group had very low acceptance scores in both scenarios and found it difficult to reject any of the sentences regardless of the verb type, revealing that this group have not yet acquired the properties underlying these aspectual distinctions. The results obtained from the 15 native controls show acceptance of Imperfect and rejection of Preterit in the expected pattern in both contexts. An ANOVA confirms that the type of verb does not affect the pattern of responses for this group in either Imperfect (F(3,76) = 0.067, p = .97) or one-time-event contexts (F(3,76) = 0.06, p = .96). A similar pattern of responses was also found for the advanced and intermediate learner groups in Imperfect contexts, but not in one-time-event contexts where the verb type seems to affect the learner's responses.

Figure 10. Mean ratings of input sentences in Imperfect contexts.

Figure 11. Mean ratings of input sentences in one-time-event contexts.

In Imperfect contexts, intermediate and advanced learners correctly accept the Imperfect and reject the Preterit equally for both types of verbs as none of the differences between the responses for event and state verbs were significant (p = .58 for Imperfect sentences and p = .59 for Preterit for advanced learners; p = .69 for Imperfect sentences and p = .49 for Preterit for Y13 learners). This result suggests that the type of verb does not affect intermediate and advanced learners’ responses in Imperfect contexts.

In contrast, an effect arising from the type of verb was observed for the pattern of responses obtained in the one-time-event (Preterit) context for both the Y13 and the UG groups (see Figure 11). The results of the ANOVA demonstrate a significant effect of verb type for the advanced learner's judgements of Imperfect (F(1,38) = 9.5093, p = .003) and Preterit (F(1,38) = 10.792, p = .002) sentences. Similarly, an effect of verb type was found for Imperfect (F(1,34) = 6.0255, p = .01) and Preterit (F(1,34) = 5.0660, p = .03) sentences for the intermediate group.

As Figure 11 shows, the acceptance rates for sentences with Preterit morphology in one-time-event contexts were higher with event verbs (at similar rates to the native controls) than with states for all the learner groups. This result suggests that intermediate and advanced learners had more difficulty accepting the Preterit when the verb was a state in this context. Similarly, learners had more difficulty rejecting the sentence with Imperfect morphology when the verb was a state than when the verb was an event. This result suggests that these two groups of learners had more difficulty rejecting the Imperfect when the verb was a state.

5.5 Summary of results

The results from the SCMT have shown that a state–Imperfect and event–Preterit association exists in the grammar of intermediate and advanced L2 Spanish speakers. This is evidenced by the fact that learners do not prefer the Preterit over the Imperfect with states even when this is the appropriate option (in one-time-event contexts). This result converges with similar types of associations found in the production data. However, the SCMT task results also show that these learners know that Imperfect can be used with verb types other than states (learners correctly prefer Imperfect with states AND events in Imperfect contexts) and that such associations are possible in Spanish. This finding is also supported by the production results as even the intermediate learners tested were able to use Imperfect with lexical classes other than states (see the results of the Las Hermanas task).

One important result is that although the intermediate and advanced learners did not judge sentences with eventive and stative verbs differently in Imperfect contexts, both learner groups accepted appropriate Preterit sentences with states significantly less often than with events, and rejected inappropriate Imperfect sentences with states less often than with events. That is, these learners have more problems accepting the Preterit with states and rejecting the Imperfect with states in contexts where these were the correct options. This result shows that, at least in perfective contexts, learners’ responses seem to be revealing a strong Imperfect–state and Preterit–event association. These results also support the suggestion that dynamicity is the lexical feature which learners are most sensitive to even at advanced stages of acquisition.

6. Discussion

The main aim of the two empirical studies was to investigate whether the L2 distribution of Preterit and Imperfect forms varied across lexical classes as predicted by the LAH, by assessing to what extent comparing the results of four different tasks (including both production and comprehension and different levels of task control) can provide more robust evidence to resolve this long-standing debate.

The review of the literature pointed out persistent problems with the methodology used in studies assessing the LAH, in particular failure to elicit infrequent semantic–morphology pairings and lack of convergence from different task types. It was argued that due to the rarity of particular forms in naturally occurring contexts, it was necessary to devise varied elicitation methods which would include carefully designed tasks that manipulate the types of contexts in which learners had to use the target forms. The results of the three production tasks were combined and demonstrated that learners’ use of Preterit does not seem to coincide more often with telic than atelic predicates as hypothesised by the LAH. Instead, our results converge to show that learners’ pattern of responses is revealing of a state–Imperfect and event–Preterit association. That is, although lexical aspect plays a role in this case, it is dynamicity and not telicity that affects learners’ choices.

Previous studies have also shown evidence that a state–Imperfect association guides the L2 acquisition of French temporal morphology (Bergström, Reference Bergström1995, Reference Bergström and Bartning1997; Kaplan, Reference Kaplan and VanPatten1987; Kihlstedt, Reference Kihlstedt, Salaberry and Shirai2002), but why this semantic contrast is relevant during the early stages of acquisition of these forms remains unknown. Dynamicity is perhaps the least understood of the semantic features typically used to classify verbs in different lexical classes (telicity and durativity are the other two) and the most difficult to characterise (see relevant review in Salaberry, Reference Salaberry2008). It is not obvious how the current explanation for the dynamic/non-dynamic distinction (i.e. whether the event requires a sustained input of energy as argued by Comrie, Reference Comrie1976) can enlighten these acquisition findings, except that it suggests that the aspectual nature of dynamic/non-dynamic events is largely lexical and it is not affected by the verbal phrase as a whole (i.e. dynamicity is not compositional) whereas compositional factors are involved in the interpretation of telicity in Spanish (see details in Hodgson, Reference Hodgson2006).

One anonymous reviewer suggests that our results could be explained if we assume, following Giorgi and Pianesi (Reference Giorgi and Pianesi1997), that English dynamic verbs have a [+perfective] feature. This analysis implies that all eventive verbs in English are implicitly interpreted as being perfective so it is possible to assume that English speakers may think that this is the case in Spanish as well. This, in turn, presupposes that perfective/progressive is the aspectual distinction which is relevant for native speakers of English (as opposed to the telic/atelic distinction). An analysis along these lines would see our results as supporting the view that L1 transfer plays a crucial role in the acquisition of Spanish past tense morphology. Although this is an interesting possibility, whether English event verbs are always perfective is an issue which is currently under debate and needs to be further clarified (see Bogaart, Reference Boogaart1999; Brinton, Reference Brinton1988; Smith, Reference Smith1991). We leave it for further research to further explore this line of research.

Taking into consideration that the speakers in our study were learning Spanish in an instructed setting, it may be the case that instruction determines the robustness of the observed Imperfect–state association (i.e. Imperfect is mostly introduced and first used with states such as ser/estar “to be”). In order to examine this possibility we carried out an analysis of the different types of state verbs that our participants used with Imperfect forms in the least controlled oral task (the personal narrative). As expected the number of different state verb types increases with proficiency as only 10 types were used by Y10 learners, but 19 were used by the Y13 group and 26 by the advanced speakers. In contrast, native controls used a total of 31 different state verbs in this task. These results do seem to indicate that Y10 learners are using Imperfect forms with a limited group of frequently used state verbs (see Collins, Reference Collins2002, for similar findings in L2 English and Bardovi-Harlig, Reference Bardovi-Harlig, Kempchinsky and Slabakova2005, for relevant discussion). The analysis of the type of state verbs used in the personal narrative task by each group shows that in the case of the beginner learners, 85% of state verb tokens used were forms of ser or estar “to be” although some instances of tener “to have”, haber “there is/are” and other types were observed as well (see details in Table 8).

Table 8. Percentage of use of Imperfect across state verbs.

Y10 = Year 10; Y13 = Year 13; UG = Undergraduates; NS = Native speakers

Interestingly, the intermediate learners’ use of Imperfect with ser and estar is similar to that of the advanced learners and native controls. This group is also using a wide variety of state verbs at this stage. Recall that intermediate, and even advanced learners, show sensitivity to the state–Imperfect association in the comprehension task; these results, however, show that their use of Imperfect with state verbs is not restricted to a few high frequency types. This seems to indicate that the early association of Imperfect with ser and estar observed for the Y10 group is no longer observable by the time learners reach intermediate proficiency and cannot fully explain the persistence of such association observed in our data. Further research is needed to clarify the nature and the full extent of this association in L2 Spanish.

The results of the advanced and native group in the production study merit special attention. The combined results of the three oral tasks show how Preterit was used more frequently with telic predicates and Imperfect with atelic by these two groups of Spanish speakers. Although the pattern observed for the advanced group seems to follow the predictions of the LAH, the fact that native speakers also show the same distribution seems to suggest alternative explanations. After all, the LAH is a hypothesis about learners’ behaviour in early stages in the acquisition process when they have difficulty acquiring past tense morphological forms. It would therefore seem strange that native speakers, as well as advanced learners, use particular forms with particular verbs because they are unable to treat past tense morphology as proper aspectual markers. Previous studies on the acquisition of Spanish have also shown that the use of prototypical temporal markers with particular verbs types is common in advanced learners who use these associations even to a greater extent than native speakers (see Salaberry, Reference Salaberry1999). In the current study, evidence that the use of Imperfect by the advanced learners is not constrained by the LAH comes from the fact that learners were able to produce appropriate telic–Imperfect associations in a controlled task (Las Hermanas) which was designed specifically to elicit those combinations. It may be possible that advanced learners end up forming these specific associations because they occur frequently in native input (i.e. the Distributional Bias Hypothesis, Andersen & Shirai, Reference Andersen and Shirai1994, Reference Antti and Järvikivi1996). Corpus studies examining the exact frequency of the patterns reported in this study for the native group are needed to support or eliminate this possibility (see Tracy-Ventura, Reference Tracy-Ventura2012). However, recent research (see McManus, Reference McManus2011) examining the L2 acquisition of French past tense morphology has also found similar behaviour in the oral data of a group of English native speakers. This seems to indicate that the use of Preterit with telic events and Imperfect with atelic is not unique to native Spanish but is a feature shared by other languages with similar morphological contrasts. This study shows that even when learners appear to behave in a manner which is consistent with the LAH (as in the case of the advanced group) those same learners are able to produce Imperfect forms with all lexical classes in the task which prompted this range of form meaning associations (Las Hermanas).

We would like to conclude this study on a methodological note. Our study is one of very few which have incorporated both corpus and experimental data to investigate a hypothesis of major interest in SLA research (see also Wulff, Ellis, Römer, Bardovi-Harlig & LeBlanc, Reference Wulff, Ellis, Römer, Bardovi-Harlig and LeBlanc2009). Our findings show that the frequency of use of the target forms varies across tasks, in line with previous claims that the design of the tasks used can affect and bias the results obtained in this grammatical domain (Slabakova, Reference Slabakova2001). The manipulation of narrative structure, as in the Las Hermanas task, has been crucial in observing particular learner behaviours which were not apparent in the uncontrolled oral tasks. It was only through the combination of data from these different types of elicitation methods that we were able to obtain a clear insight into learners’ mental representations in this grammatical domain and establish differences in learners’ knowledge of past tense morphology and their actual use of Imperfect and Preterit in real speech.

Although the usefulness of collections of large-scale data as linguistic evidence in work on syntactic theory has already been argued for (Armstrong, Reference Armstrong1994; Kempchinsky & Gupton, Reference Kempchinsky and Gupton2009) and a few learner corpora are being developed to test existing hypotheses in SLA research (e.g. the FLLOC (flloc.soton.ac.uk), SPLLOC (splloc.soton.ac.uk) and Wricle corpora (web.uam.es/proyectosinv/woslac/Wricle)), these do not represent common practice in formal SLA research. The apparent lack of interest shown by formal SLA research may be because corpus data are often regarded as limited with respect to the type of evidence they can provide. For instance, absence of positive evidence for the use of a particular form cannot be used as evidence for the ungrammaticality (or lack of acquisition) of that form. This is particularly important in formal SLA research, where exploring learners’ knowledge of what is ungrammatical (i.e. what is not allowed in learners’ interlanguage) is as fundamental as exploring what learners think is grammatically possible (Duffield & White Reference Duffield and White1999; White, Reference White1989). The current study shows, however, that combining experimental and corpus data can indeed provide robust converging evidence on the mental status of interlanguage grammars while overcoming some of the limitations of using only experimentally controlled data (including the metalinguistic nature of the judgements and problems of generalisability) or naturally occurring data (which may not be representative of what learners really know about the target grammar).Footnote 10 On the basis of the results presented in this study, we argue that this methodological approach can be very useful to address and clarify a wide range of theoretical problems in SLA research.

7. Conclusion

This study has examined a new set of data on the L2 acquisition of Spanish past tense morphology by native speakers of English in order to test the validity of the Lexical Aspect Hypothesis. The only piece of evidence in favour of a possible effect of lexical class found in this study is that a strong Imperfect-non-dynamic and Preterit-dynamic association is established by L2 speakers from early on. Interestingly, the state–Imperfect association can also be observed in the comprehension data of intermediate and advanced L2 speakers (these speakers have problems rejecting the Imperfect with state verbs in one-off event contexts). Overall, our results show that dynamicity (and not telicity) determines the emergence of the two available past tense forms in non-native Spanish and that the use of Imperfect and Preterit does not spread across lexical classes as predicted by the LAH. These results seriously question the validity of this hypothesis for the L2 acquisition of Spanish aspect-related morphology. Our results have also shown that sensitivity to discourse grounding (background and foreground) when choosing between the two available past tense forms starts to develop at the intermediate level of proficiency and that advanced learners are already successful at altering frequent Imperfect–atelic and Preterit–telic associations in a manner similar to that observed for the native controls.

A second contribution of this study is to demonstrate that using a mixed methodology approach (i.e. combining production and comprehension data using elicitation tasks with varying experimental control) is a successful way to tackle a long-standing issue in SLA research. Data collected through four different tasks have revealed how intermediate and advanced speakers’ use of Imperfect and Preterit differs across oral tasks when differences in discourse grounding are accounted for. Our experimental data testing the production and comprehension of non-prototypical associations have confirmed that L2 Spanish speakers are able to appropriately use non-prototypical form–meaning pairings. In turn, this shows that prototypical associations observed in the production data do not fully account for these speakers’ grammatical competence in this grammatical domain.