Malaysia is a ‘syncretic state’, which is exemplified in the political sphere by the mixture of coercive elements with electoral and democratic procedures.Footnote 1 The syncretic nature of the operations of the government is, to a large extent, necessitated by the need to secure stability in the multi-ethnic Malaysian society of about 27 million people. Malaysia is widely accepted as a country which has sustained a legitimate political system based upon popular participation. Nevertheless, several studies characterized Malaysian political system as a fettered democracy or a ‘semi democracy’.Footnote 2 This study analyses Malaysia's 12th general elections by concentrating upon the parties, issues, personalities, and results, as well as the laws relating to elections to ascertain if they conform to democratic principles. How did the competing parties fare in the election? Is the 2008 election a repeat of the past elections held earlier? What are the implications of 2008 election results for the future of democracy and race-based politics in Malaysia?

Elections in Malaysia are held for the House of Representatives (Dewan Rakyat) of the bicameral Parliament at the national level and for the State legislative assemblies (Dewan Undangan Negara) of the 13 states. Members of respective houses are elected from single-member constituencies using the first-past-the-post system. This plurality-majority electoral system is a legacy of British colonial rule in Malaysia. The Constitution of Malaysia requires that parliamentary elections be held at least once every five years. However, the Prime Minister may dissolve the Parliament with the approval of the Yang di Pertuan Agong, the King, before the expiry of this five-year period. The Constitution requires that a general election, supervised by a politically neutral Election Commission, must be held within three months after the dissolution of the Parliament. Any legally qualified Malaysian citizen may register as a candidate in the election by filing the appropriate forms and a monetary deposit of RM 10,000 (US$ 3,215) for a parliamentary seat and RM 5,000 (US$ 1,608) for a state assembly seat.Footnote 3

The 2008 general election

Election for the 12th Parliament was rumored to take place at the end of 2007. These rumors were fuelled by the nation's economic growth and the decision of the ruling United Malays National Organization (UMNO) to postpone its election to focus on the strategies to win the 12th national election.Footnote 4 However, elections had to be delayed because of several anti-government demonstrations, including the one organized by the Hindu Rights Action Force (HINDRAF) complaining of Indians being institutionally sidelined by the government. The postponement was also due to the major floods in December 2007 that forced thousands out of their homes.

Speculations continued until Prime Minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi dissolved the Parliament on 13 February 2008, with the consent of the King.Footnote 5 All state assemblies, except for Sarawak, were also dissolved. Polls were not due until May 2009, but Prime Minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi wanted a fresh five-year mandate to capitalize on a string of state construction projects launched during 2006 and 2007 as well as to garner a fresh mandate before an expected slowdown in the global and Malaysian economies took place.Footnote 6 From the opposition perspective, the early scheduling of the election was to deny the major opposition figure, Anwar Ibrahim, the chance to take part in the election. Anwar, who was charged and convicted of corruption, was not eligible to stand for election until 14 April 2008. Anwar Ibrahim criticized the Prime Minister on the choice of date, calling the move a ‘dirty trick’.Footnote 7

The day after the dissolution of the parliament, the Election Commission announced the nominations to be held on 24 February 2007, and the general polling at the national and state levels to take place on 8 March 2008. This gave 13 days of campaigning to take place. The general election involved 222 parliamentary seats and 505 state assembly seats. In the 2004 elections, candidates contested for 219 parliamentary seats. The three newly created seats – Igan, Sibuti, and Limbang – resulted from a constituency re-delineation exercise in Sarawak. There were in total 576 state seats, but Sarawak did not dissolve its State Assembly as its members were elected on 20 May 2006.

The Election Commission budgeted about RM 200 million (about US$ 64 million) for election expenses. It hired 149,000 mostly schoolteachers and 50,000 casual workers for smooth running of elections.Footnote 8 According to the Election Offences Act 1954, a parliamentary candidate is allowed to spend a maximum of RM 200,000 (US$ 64,308) while a state candidate is allowed RM100,000 (US$ 32,154) for campaign during the election. This means the BN's 222 parliamentary candidates and 504 state candidates for the 12th general election could collectively spend up to RM94.8 million (US$ 30.5 million). However, the amount spent far exceeded the legal ceilings.

The Election Commission (EC) introduced several changes for this election. The notable changes include the use of transparent ballot boxes for the polling agents to see, the availability of full electoral rolls in order to check and verify the names of all registered voters to avoid electoral fraud, absence of serial numbers on ballot papers to ensure anonymity, the casting of postal ballots to be observed by polling agents at army and police camps, and the continuation of the system of counting ballots at the polling centres, instead of at the official tally centre, to expedite the counting process and the declaration of results.Footnote 9 These changes by the Election Commission have been lauded by the poll observers arguing that there is room for further improvement.

The EC had also decided to use indelible ink to prevent multiple voting. However, four days before the polls, the EC reversed its decision arguing that ‘the security of this method of preventing multiple voting has been breached’.Footnote 10 The police received reports that similar inks had been smuggled into the country and that there could be attempts to use the ink to prevent unsuspecting voters, particularly from the rural areas, from voting. Besides the breach in security, the EC also cited the absence of legal provisions for the use of indelible ink that required amending the Constitution. The opposition parties condemned this decision of the EC as undemocratic, adding that the EC had wasted RM 2.4 million (US$ 0.77 million) on 48,000 bottles of ink.Footnote 11 They also accused the Election Commission of being in league with the government. The EC made its decision on the advice of the ruling party leaders.Footnote 12 Yet, the leaders of the ruling coalition considered the EC decision ‘not good’ as it might affect the perception of voters about the EC.Footnote 13 The Prime Minister, Abdullah Badawi, saying that the Barisan Nasional (National Front or BN) preferred the use of indelible ink, considered the EC's decision ‘highly regrettable’ but election must go on.Footnote 14 The Election Commission also required the nomination papers to be stamped with a RM 10 (US$ 3.22) stamp duty on the statutory declaration (Form 5 or 5A). This requirement was later withdrawn because, according to PAS vice-President Mohammad Sabu, many Barisan Nasional candidates did not have their statutory declarations duly stamped.Footnote 15

Candidates and parties

As announced, the nominations were held relatively smoothly on 24 February 2008. In all 1,588 candidates, including 103 independents, were approved by the Election Commission for contesting in the election. The ruling Barisan Nasional nominated candidates for all the parliamentary and state seats though one of its Kelantan State Assembly candidates was disqualified for bankruptcy. Among the major opposition parties, Parti Islam Se Malaysia (Islamic Party of Malaysia, PAS) filed 301 candidates of whom 66 were for parliamentary and 235 for state assembly. Parti Keadilan Rakyat (People's Justice Party, PKR) nominated candidates for 97 parliamentary and 174 state assembly seats. The Democratic Action Party (DAP) nominated 47 for parliamentary and 101 for state assembly seats. The BN won eight parliamentary and two state constituencies uncontested. Sarawak based major party, PBB, nominated 14 candidates for parliamentary seats. It did not field any candidate at the state level because Sarawak did not hold elections for state seats in conjunction with those of other states. In Sabah, Parti Bersatu Sabah (Sabah United Party, PBS) filed nomination for four parliamentary and 13 Sabah state assembly seats.

The March election witnessed a number of new faces contesting the election. In previous elections the new faces ranged between 20 to 30%; the March election saw some parties fielding as many as 55% new faces. Thus, the Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA), a major component of the BN, introduced 22 new faces for the 40 parliamentary seats it had been allocated. The Malaysian Indian Congress (MIC), another component of the BN, introduced 13 new faces for the 19 state seats it contested. Likewise, PAS in Kelantan fielded 11 candidates at parliamentary level of whom seven were new. Almost all the new faces were professionals or more youthful and energetic politicians.

Of the 1,588 candidates, 118 were women, 39 of whom contested the parliamentary seats. Two women candidates from Barisan Nasional won their parliamentary seats uncontested. One woman candidate from PAS won a Kelantan state assembly seat uncontested. The oldest candidate in the 12th general election was Maimun Yusuf, an 89-year-old unlettered grandmother who contested the Kuala Terengganu parliamentary seat. It was expected that she would garner enough sympathy votes to let her claim the RM 10,000 deposit money back. However, she lost the deposit money as she polled only 685 votes, far short of the required 1/8th of the 72,259 votes.

Interestingly, 185 parliamentary and 440 state seats saw direct one-to-one contests. A total of 23 parliamentary and 39 state assembly constituencies had three candidates each. In other words, in these constituencies the BN candidate was challenged by two other candidates. In the remaining nine parliamentary and 24 state constituencies, the number of contestants exceeded three, and in two Sabah state constituencies, there were eight contestants. This was because of the proliferation of local parties and an increasing number of independent candidates.

Barisan Nasional is a multi-ethnic alliance of 14 political parties but also constitutes a party in its own right.Footnote 16 It has its own constitution; in elections it behaves like a single party by putting forward a common team of candidates contesting under a single banner. Given the plural nature of Malaysian society, political leaders of various ethnic groups have opted for a consensus politics through the formation of BN.Footnote 17 United Malays National Organization (UMNO) is the dominant party, followed by the MCA, the MIC, Parti Gerakan Rakyat Malaysia (Malaysian People's Movement Party, Gerakan) and other smaller parties. The major components of BN in Sabah and Sarawak are Parti Bersatu Sabah (United Sabah Party, PBS) and Parti Pesaka Bumiputera Bersatu (United Traditional Bumiputera Party, PBB). Candidates for office are nominated through a complicated process of seat sharing. The time-tested formula behind the distribution of seats is that the parties will not field candidates against each other and each will contest where it is most likely to win.

Of the 13 opposition parties that contested the election, three stand out: PAS, DAP, and PKR. PAS is a Malay-based Islamic party with a commitment to its goal of establishing an Islamic state. Since 2004, the party has adopted ‘the moderation strategy’, launched its outreach programme to recruit non-Muslims, and adopted the motto ‘Pas for all’. It reaches out for non-Malay support through PAS supporters' club composed of non-Muslims, mainly Chinese.Footnote 18 Subsequently, PAS has replaced its earlier slogan of establishing an Islamic state with a ‘welfare state’. In the 1999 elections PAS was a leading component of the short-lived opposition coalition known as Barisan Alternatif (Alternative Front, BA) that included KeADILan, DAP, and Parti Rakyat Malaysia (Malaysian People's Party, PRM).

PKR is formed in 2003 by a merger of Parti Keadilan National (KeADILan or National Justice Party) and the older PRM. KeADILan was launched on 4 April 1999 with Dr Wan Azizah Wan Ismail, the wife of former Deputy Prime Minister, Anwar Ibrahim, as its president. KeADILan claimed to be a bridge ‘between existing parties’.Footnote 19 Despite merger, the PKR remains a centrist party and promised a just and democratic administration, accountability, transparency, and rule of law in Malaysia and genuine multi-ethnic, multi-religious cooperation and unity. In the 2008 elections, PKR formed an alliance with PAS and DAP separately whereby they agreed not to nominate candidates against each other and thus ensuring a straight fight with the BN.

DAP is professedly a non-communal party with a commitment to achieve a ‘Malaysian Malaysia’. It is strongly identified with the predominantly urban Chinese and has difficulty obtaining support from other groupings. Yet the party did nominate Indian and Malay candidates in the 2008 elections. The party is avowedly secular and broke away from the Barisan Alternatif in 2001, as it could not accept the PAS slogan of making Malaysia an Islamic state.

Campaign strategies

Campaigning for the twelfth general elections unofficially began at the end of 2007, long before the national parliament was dissolved.Footnote 20 Officially, however, the election campaign period covered 13 days in March 2008, the longest such period in Malaysia's electoral history since 1969. The opposition parties, however, asked for a longer period to convey their viewpoints to the electorate effectively. Campaigning assumed four major forms: poster wars, small group discussions (ceramah) or political rallies, door-to-door efforts, and electronic means including use of the Internet and mobile phone companies' short message services (SMS).

Posters, leaflets, and billboards appeared throughout the country. The flags and banners of BN could be seen everywhere. The party erected some 4,500 billboards at strategically chosen roundabouts and junctions and along highways across Malaysia. The theme of Barisan Nasional's advertising blitz was ‘Security, Peace, Prosperity’. The agencies hired to make the commercials used a ‘sledgehammer’ approach in dealing with political opponents. They highlighted the achievements of the coalition government, used blatant or crude attacks on the opposition, and warned the public not to gamble in the election by voting the opposition.

Although PAS, DAP, and PKR took part in the poster wars, their flags and leaflets were visible in and around election operation centers. Opposition candidates, in several interviews with the author, admitted that they were constrained by limited resources. Parties also bought advertising space in newspapers. Once again, BN had an edge because it controls major Malaysian media outlets. Almost the entire print media, as well as radio stations and television channels, devoted much of their news programs and election coverage to promoting the government's achievements. A content analysis of the mainstream media shows that during the 13-day campaign, BN bought approximately 1,100 pages of full-page color ads in all local newspapers. The opposition did use the national media outlets but they relied extensively on their own bimonthly and monthly magazines to reach out to the people.

In addition, the contesting parties made greater use of the Internet than previously to reach the voters. Many political parties had created their own websites long before the elections were announced. For the opposition parties, which get little mainstream media coverage, the Internet provides access to a wider audience. PAS, DAP, and PKR offer well-designed websites with much information about party policies and programs. Websites such as Malaysiakini, Aliran.com, Agendadaily, and several others provided a medley of news updates on current affairs and a forum for debate on issues in Malaysian politics and economy.

Political parties also made extensive use of blogs, YouTube, and the mobile phone's SMS. PKR, DAP, as well as the Youth and ‘Puteri’ (literally princess) wings of UMNO, among others, campaigned by SMS.Footnote 21 Among the opposition, PAS offered information services via SMS for 50 cents (US$0.13) per message. Recipients of messages received the headlines and lead paragraphs of Harakah's top stories daily and notices about the time and venue of ceramahs. Barisan Nasional's campaign site, http://bn2008.org.my, unveiled two weeks prior to the election, presented the government's achievements and progress and countered the opposition's allegations.

The parties also used ceramah to reach out to and feel the pulse of the people. Most of the ceramah were held in open grounds; some were targeted at specific groups of about 100 to 200 people. The ceramah were usually held at night. Compared to 2004, ceramah in the 2008 elections were frequent and were filled with high-spirited public speeches often characterized by personal attacks and character assassinations. Police have issued 2,971 permits for election ceramah nationwide.Footnote 22 These ceramahs were in addition to those held within the compounds of supporter's residents. The opposition parties used the ceramah to highlight Malaysia's rising crime rate, consumer-price inflation, and government corruption. Most parties preferred door-to-door campaigning. Dressed simply, candidates visited houses and marketplaces explaining their stands and soliciting votes. The participants took the elections seriously, spending massive amounts of money mobilizing voters and organizing polls and demonstrating considerable faith in the legitimacy of electoral politics. The parties paid travel allowances to outstation voters to return home and vote for the parties of their choice. Understandably, BN paid better allowances than the opposition parties.

Parties also used election theme songs to convey their message to the voters. MCA had a two-and-a-half-minute song in Mandarin, packed with lines of lyrical promises titled ‘Cherish Each Other, Work Hard Together’. The song was to drum up support and inject energy in the party's campaigns. In Sungai Siput, the PKR candidate had a song, sung repeatedly on nomination day and in campaigns since then, titled ‘Sungai Siput Residents' Song’. The DAP had its own musical overture entitled ‘Just Change It’, with a melody hauntingly reminiscent of the 2006 World Cup tune by Patrizio Buanne, ‘Stand Up [For The Champion]’. The DAP song was available for download as ring tones in the MP3 format.

Manifestos

The Barisan Nasional, except for its Kelantan state liaison committee with an additional state manifesto, had one single manifesto to represent all its coalition partners. The opposition had three different national manifestos and contested under their respective symbols. This led the BN deputy president, Najib Tun Razak, to claim that opposition parties did not have the same direction and did not agree on policy and ideology. They made ‘pacts [only] to oppose BN during elections’.Footnote 23

The BN's 24-page manifesto had the theme ‘Security, Peace, Prosperity’. The BN manifesto contains a progress report on 76 major Barisan achievements under Abdullah's leadership since the 2004 polls. In the preface, Abdullah pointed out that the country's economy grew by 6.3% in 2007, the best performance since 2004; its fiscal deficit was brought down to 3.2% of gross domestic product; international trade crossed the RM1 trillion mark; some 1.3 million job opportunities were created and ‘five strategic corridor developments were launched’.Footnote 24 The government had spent RM16.2 (US$ 5.21) billion in petrol, diesel, and gas subsidies; RM18 (US$ 5.79) billion in lowering gas prices for industry and electricity generation; and increased the civil servants' salaries and cost of living allowance to RM8 (US$ 2.57) billion per annum The government has allocated monthly allowances for 1.5 million deserving students, increased maximum monthly assistance per poor household from RM350 (US$ 113) to RM450 (US$ 145), and upgraded monthly allowance for disabled workers from RM200 (US$ 64.31) to RM300 (US$ 96.46).

The Manifesto pledged to raise the nation's productivity, income, and competitiveness levels; eradicate hardcore poverty and bring down poverty rate down to 2.8% by 2010; raise the teachers' qualification and provide more scholarships for poor but deserving undergraduates regardless of race. The manifesto promised to lower the country's crime index, enforce anti-corruption measures, and speed up implementation of e-government initiatives. To foster national unity, the Manifesto emphasized the promotion of better understanding of Islam among Muslims and non-Muslims through Islam Hadhari and to increase dialogue on inter-faith issues. In international affairs, the Barisan Nasional would continue to play an active, principled, and impartial role in international affairs and advance the economic agenda of the OIC through capacity building in less developed OIC member countries.

With the caption ‘A Nation of Care and Opportunity’, PAS Manifesto promised a trustworthy, just, and clean government for a better life. The Manifesto did not call for transforming Malaysia into an Islamic state. It rather pledged to defend the well-being of the people and safeguard the interest of the nation through prudent management of state resources and a balanced approach to development. It also promised to reduce the cost of living, promote freedom of religion, and to ensure equal justice to all.Footnote 25 It promised to end all excesses and injustices of the BN regime, uplift ‘the professionalism of our Police and Security forces’, and institute an effective integrity plan to reveal, corrupt practices, abuse of power, cronyism and nepotism. It would uphold the Rule and Sanctity of Law by reinstituting the Judicial Integrity and restore genuine democracy through a free, clean, and fair electoral process. The PAS manifesto did not solicit votes to replace the BN government but to put ‘an effective element of “check and balance” in our system of government’.Footnote 26

For Kelantan, PAS issued a separate manifesto with the theme ‘Develop with Islam, lead towards change and achieve blessings’. The Manifesto listed the ‘positive’ changes the PAS government had brought during the last 18 years, including good administration and municipality, Islamic education, rights for all races, women's dignity, human development, housing, and the Islamic financial legal system. The state PAS promised to offer group takaful (insurance) schemes for teachers, staff, and students of the Kelantan Islamic Foundation for free and introduce programs to train, assist, and guide women so that they could achieve socio-economic progress. It would also set up a fund for women in business and build a sports complex for women complete with a stadium and a mosque. PAS leaders asked its followers to fast on the day of elections and conduct special prayers to save the state from the BN onslaught.

The DAP unveiled an eight-point manifesto with a call to ‘Just Change It’. Like other opposition Manifesto, the DAP Manifesto began by providing a critique of the Barisan Nasional government. The Manifesto claimed that the BN has failed to deliver on its promises of ‘justice, respect for rule of law, sharing our economic wealth, lowering crime rates, equal opportunity, reduced corruption, greater political freedom, accountability and good governance’ made in the 2004 general election.Footnote 27 The party pledged to: ensure safer streets and establish an Independent Police Complaints and Misconduct Commission, provide better living standards, establish a Malaysian-first economic policy, ensure quality education; promote a healthy environment for the future generation, provide gender equality and youth empowerment, establish a clean and transparent government, and ensure democracy and freedom with an independent election Commission to promote electoral reforms. It also promised a bonus of up to RM6,000 (US$ 1,929) per family for households earning RM6,000 or less per annum. The DAP Manifesto ends by asking the voters to ‘deny BN two-thirds majority’. Like PAS, the DAP campaigned not to form a government but merely to reduce BN's majority, presumably to provide a strong check and balance in the government.

In Sarawak, the party was seeking to get the Sarawak Land Code amended to protect the rights that codify property rights that is to make provisions for automatic renewal of land titles as and when the lease expires. Saying that people are the real owners of natural resources such as land, forest, mines, sand and gravel, Sarawak DAP also wanted to end the monopoly of maritime resources and their extraction as well as profits by ‘oligarchic’ parties.

PKR's five-point manifesto is entitled ‘A New Dawn for Malaysia’. It promised to make Malaysia a truly constitutional state guaranteeing basic human rights, rule of law and an independent judiciary; create a vibrant economy; eliminate discriminatory policies, corruption and wastage; make streets and neighborhoods safer by creating a professional and neutral police force; make Malaysia more affordable by lowering petrol prices, ensure tolls and tariffs are never raised unreasonably; and increase the standard of education, including higher salaries for educators.Footnote 28 The party also pledged to abolish the New Economic Policy and replace it with an affirmative action to help the poor of all races and religions and a minimum wage of RM1,500 (US$ 482).

Like others, the PKR manifesto lamented: ‘Over the last few years, we have seen our nation being dragged through increasing racial division, debilitating economic performance as well as unprecedented levels of crime and corruption.’ Likewise, a common theme in the three manifestos of the opposition parties was inflation and the cost of living. PKR even pledged to lower petrol prices. Unlike others, however, the PKR Manifesto ‘encapsulates PKR's vision for putting Malaysia back on track’.Footnote 29 It described how PKR will govern and ‘build a nation that reflects the true potential, talent and calibre of the Malaysian people’.Footnote 30 The Manifesto was highly personal with its leader, Anwar Ibrahim, pictured saying: ‘My five promises’.Footnote 31

Results

Elections were held as scheduled on Saturday, 8 March 2008. In all, 7,950 polling stations were installed for the 10.7 million registered voters. Barisan Nasional won 140 of the 222 seats in the federal parliament. As pointed out by Abdullah Badawi, in most places, the size of the BN majority ‘would be considered a landslide’.Footnote 32 Yet it was a huge set back for the ruling coalition such that the stock market fell by 10% a day after the election, as investors worried about the danger of unrest and instability in the country.

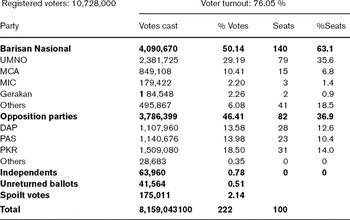

As shown in Table 1, the BN polled about 50% of the popular votes from the 8.2 million ballots cast and won 63% of the seats in Parliament. In 2004, the BN won about 64% of the popular vote and 92% of the 219 parliamentary seats. The BN component parties performed miserably. Gerakan lost 80% of parliamentary seats it contested, MIC 67%, MCA 51.6%, and Umno 27.5%. The election saw the defeat of four ministers, eight deputy ministers, and eight parliamentary secretaries. Opposition parties won 82 seats. PKR, which had only one member of parliament elected in 2004, won 31 seats. DAP captured 28 and PAS obtained 23 seats. No one expected such a massive swing to the opposition. It was expected that the Chinese and Indian voters would abandon the BN. There were stories of Malays who had decided to ‘throw away’ their votes as a sign of protest. But what happened was beyond anyone's comprehension.

Table 1. Results of parliamentary elections

Source: Calculated from the data supplied by the Election Commission, Malaysia.

This was BN's worst performance ever in Malaysia's 50 years of independence, and crucially, for the first time since 1969, the BN lost the two-thirds majority in parliament. Abdullah Badawi, knowing he could not repeat the landslide he achieved in 2004, had set this as the electoral winning post. He fell short of eight seats to reach the targeted two-thirds majority. This matters in practical terms since the BN can no longer override legislation passed by the states or amend the constitution at will. Interestingly, its peninsula-wide popular vote was only 49.79%, which effectively means that the opposition received the majority vote in this part of the country. However, when converted to parliamentary seats, BN has 85 of the constituencies in the peninsula, while the opposition won only 80. Almost 40% of the BN's seats, 55 out of 140, are in Sabah and Sarawak.

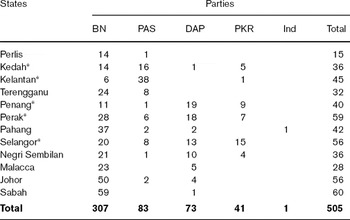

In the concurrent elections for assemblies in 13 states, the BN won majorities in eight, conceding five states to the opposition. As shown in Table 2, in the State of Penang, the BN-UMNO won 11 of the 40 state seats. Gerakan, which has led the state since 1969, could not get a single seat. The DAP which captured seven parliamentary and 19 state seats formed the government in Penang in coalition with PAS and PKR. Penang, with a majority of Chinese voters, is a major industrial center, producing microchips, mobile phones, and computer parts in factories owned by Intel, Dell, and Motorola, among many others. In Kedah, the Opposition took 22 of the 36 state seats. PAS, in alliance with PKR and DAP, formed the state government.Footnote 33 In Selangor, considered to be a safe stronghold of Barisan Nasional, the opposition parties won 35 of the 56 state seats and formed the government led by the PKR Secretary General. Perak was one of the tightly contested states with BN winning 28 state assembly seats and the opposition winning 31 seats, still giving the opposition the chance to form the government.

Table 2. Seats won in the state assemblies by political parties

Note: *indicates states where the government is currently under the opposition rule.

Source: Calculated from the data supplied by the Election Commission, Malaysia.

One of the major electoral battles was fought in the east-coast state of Kelantan, the only state controlled by PAS before the 2008 election with a one-seat majority in the state assembly against UMNO. PAS retained its control of the state of Kelantan, despite a vigorous campaign by the Barisan Nasional promising millions of dollars in development aid.Footnote 34 Additionally, PAS won back a sizable number of seats, 38 of the 45 seats, which it had lost to the BN-UMNO in the 2004 election.

In an interview with the New York Times, Anwar Ibrahim claimed: ‘I don't think Malaysian politics will ever be the same again.’Footnote 35 Controlling the five states and the metropolitan areas gives the opposition effective control over 45% of the economy in terms of gross domestic product. Consequently, the de facto leader of the opposition, Anwar Ibrahim, demands recognition as the ‘alternative government’ or ‘government in the waiting’. Realistically, however, Malaysia obviously has a strong opposition but not an alternative government yet.

Unfulfilled promises

According to Abdullah Badawi, ‘The result of the elections was a strong message that I have not moved fast enough in pushing through with the reforms that I had promised to undertake.’Footnote 36 Abdullah's unprecedented victory in 2004 general election was due, in part, to his amiable manner and to positioning himself as a progressive reformer.Footnote 37 He promised to clean up corruption, strengthen civil liberties, uphold justice, and overhaul the civil service, judiciary, and police force.

Abdullah did follow through, to some extent, on his anticorruption campaign pledges and launched a National Institute for Ethics and a National Integrity Plan in 2004. One Minister, found guilty of buying votes in UMNO's party elections in 2004, was forced to resign in October 2005. Progress has been slow in subsequent years, however. In 2006, the Prime Minister's efforts were undermined by police resistance to establish an independent police complaints and misconduct board. In the cabinet reshuffle in February 2006, the most controversial ministers retained their positions.

During the three years of Abdullah's administration, there were a number of corruption scandals including the billion-dollar fraud at the Port Klang Free Trade Zone and the outrageous and much-flaunted wealth of a ruling party member of the Selangor State Assembly who built a palatial mansion for himself without the requisite municipal approval. There were also claims that a High Court judge allowed the lawyer representing a rich businessman to write for him his judgement in a defamation lawsuit. Then there was the highly publicized case of the murder of a Mongolian model which implicated politicians and a minister. These scandals did not receive decisive responses from the Prime Minister.

Dissatisfaction was also expressed concerning the electoral system and the way elections are run in the country. There were complaints about one-sided rules and practices in the conduct of elections that favor the ruling coalition, short campaigning period that disadvantages the opposition, the delimitation (review and recommendation) of constituencies that allegedly have benefited the ruling party, and the phantom (unqualified) and the postal voters casting ballots in favor of the ruling coalition. Though the Election Commission's conduct of elections, as observed by the author in several polling centres, has been generally satisfactory, it has been accused of being biased serving the interest of the ruling coalition.Footnote 38 Consequently, 26 NGOs and five opposition political parties formed a coalition for Clean and Fair Election, known as BERSIH which organized a demonstration on 23 November 2007, demanding an immediate reform on at least three issues, i.e. the use of indelible ink, the abolition of postal voting, and the cleansing of the electoral role. The government's response was lukewarm. The use of indelible ink was agreed to, but at the last minute the EC decided not to use it till a provision to that effect was inserted in the Constitution through amendment.

Abdullah has also been seen as weak on freedom of religion issues, disappointing those who once saw him as a ‘moderate’ leader. A significant segment of the Hindu Indian minority were unhappy about a series of court cases pertaining to consequences emanating from Hindu conversions to Islam, the custody of children, the religious identity of deceased persons, and so on. The demolition of Hindu temples, purportedly for illegal construction, had also incensed the community. Thousands of Malaysian Indians led by the Hindu Rights Action Force (HINDRAF) held a rally on 25 November 2007, demanding protection of their rights. They were chased away by the police and five of their leaders were jailed under Internal Security Act which permits detention without charge or trial. This damaged Abdullah's popularity and the credibility of the BN government. M. Manoharan, one of five jailed activists, was elected to the State Assembly of Selangor while in prison. Conversely, the heads of the two ethnic Indian parties in the BN lost their seats, including the only ethnic Indian in the Cabinet, Samy Vellu, who has been heading the Malaysian Indian Congress for three decades. Almost all the Indian leaders contesting from the BN platform lost their seats.

Racial and religious tensions were compounded by developments on the economic front. In an effort to cut government subsidies, fuel prices were significantly increased first by 20 cents in 2005 and a second time by 90 cents in 2006, sparking tremendous public resistance and a series of protests in March 2006. In his four years in office, however, Abdullah has managed to maintain the economic growth at 6%, underpinned by strong export prices for commodities such as palm oil and crude oil. However, the benefits of the strong economy have accrued to small political elite to the neglect of the ordinary citizens. As pointed out by the Economist, ‘the richest 10% of the population earns 22 times the income of the poorest 10%’.Footnote 39

Many ethnic Chinese and Indians blame this lop-sided development upon the government's affirmative action program known as the New Economic Policy (NEP) that has given Malays preference in jobs, education, business, housing, finance, and religion since 1971. The Ninth Malaysia Plan (9MP), launched in 2006, aims, among others, to meet the 30% target for bumiputera corporate equity share, a primary justification for the NEP's continued affirmative-action policies.Footnote 40 According to the 9MP, the bumiputera owned only 18.9% of corporate equity. This figure was contested by others sparking tremendous national debate over the policy and assessment of ethnic wealth. Fearing the incitement of racial tensions, Deputy Prime Minister Najib Razak ordered an end to the discussion altogether. Opposition leaders, including Anwar as well as a growing number of Malays, have called for the abolition of racial preferences in recent years, arguing that they benefit only a small elite and do not really improve the economic condition of ordinary Malays.

The Merdeka Center conducted a survey with 1,026 randomly selected registered voters in Peninsular Malaysia in December 2007 to gauge public sentiment. The survey results showed that about 70% of Malaysians were concerned about price hikes and the rising cost of living, 60% about crime and public safety, and 63% about ethnic inequality in the society. They were also unhappy with the rising incidence of corruption and the government's management of the economy. Confidence in the government in running the economy was very low among Chinese and Indians. They protested by voting in strong opposition to the parliament. The survey also showed that the approval rating of the Prime Minister had decreased from 91% in 2005 to 61% in 2007. As shown in Figure 1, Abdullah's popularity suffered with increase in petrol prices and dipped significantly after the BERSIH and HINDRAF demonstrations. The survey results were published immediately but did not have much impact upon the governing elite.Footnote 41

Figure 1 Abdullah Badawi's approval rating since taking office in 2004.

Source: Merdeka Center, ‘Voter Opinion Poll 4th Quarter 2007’ [on line] available from www.merdekacenter.uni.cc/download/National, accessed on 18 March 2008.

Fractured governing coalition

The crisis caused by the credibility gap of Abdullah's administration was compounded by sharp divisions within the United Malays National Organization (UNMO). Immediately after the 2004 election, UMNO was seriously afflicted by factional fights. Mahathir Mohamad, 82, who still enjoys a good deal of respect in UMNO, has resorted to a wide-ranging campaign to discredit and depose Abdullah. In a series of dramatic statements, Mahathir accused Abdullah of undermining his legacy and failing to live up to campaign promises. He has charged that his successor was mismanaging the economy and railed against the influence of Abdullah's family members, in particular his son-in-law, Khairy Jamaluddin. Abdullah's lackluster responses added to perceptions that he was ineffective. Mahathir's venomous attacks have greatly eroded Abdullah's popularity (see Figure 1). Mahathir not merely refrained from campaigning for the ruling coalition but even advised the voters to elect a good number of opposition candidates to keep the government in check. There were also reports of UMNO leaders not being on good terms with each other. In Perlis, the three Parliamentary members were not on good terms with the Chief Minister. The supporters of the incumbent Perlis Chief Minister resigned en masse, locking up operations rooms and refusing to campaign for the party. There were other noticeable rifts in the party which led the UMNO Supreme Council to postpone internal party elections, scheduled for 2007, until after the national general elections.

Factionalism in the party was compounded by Abdullah's attempt to strengthen his base within the party by replacing established and popular veterans with loyal new candidates in the election. These misjudgments provoked a revolt within UMNO. There were reports of UMNO members themselves sabotaging campaign machineries in various states. Open disagreement over the party's candidate list broke out in Kelantan, Terengganu, Perlis, Kedah, and Perak.Footnote 42 In Kelantan, a day before the nominations, two UMNO candidates withdrew from the parliamentary seats which were quickly replaced by unknown figures. The post-election analysis by UMNO revealed that UMNO members sabotaged the electoral process in 14 parliamentary and 22 state constituencies in Perak and Kedah during the March general election. According to Abdullah, ‘the act of sabotage has already taken place. If not for it, we would not have lost the two-thirds majority and two state governments . . . This is truly regrettable.’Footnote 43

Other BN component parties were equally riven with factionalism. The MCA was weakened by internal strife with various factions fighting for influence and positions. The MCA president Ong Ka Ting dropped his key rivals, including former health minister Chua Jui Meng, who challenged Ong for the Party presidency in 2005. The Health Minister, Chua Soi Lek, resigned from office in January 2008 over a sex scandal. Publication of a videotape of the episode was widely believed to have been made by Chua Soi Lek's rivals within the MCA. The Vice President of MCA also declined to contest in the election. MCA had earlier adopted what is known as the ‘rejuvenation strategy’ in pursuance of which a number of reliable and productive candidates were dropped because they had served three terms. Fifty-eight of the party's 130 candidates were new. Some of the candidates dropped from the race worked for their rivals while others simply did not vote for their own party. The MIC is widely seen as unable to live up to its primary ideal of safeguarding the interests of the Indian community. The party was torn between various factions one of which was led by its President Samy Velu and the other by former Deputy President of the party, S. Subramaniam.

The Barisan itself was riven with a variety of different struggles. While UMNO dominated the cabinet and policy decisions, the MCA, MIC, and Gerakan have been unable to have much impact in the wake of adverse court decisions concerning the rights of non-Malays. The general feeling extended across middle-class professionals that the BN has deviated from the policy of power sharing needed for governing a plural society like Malaysia.

The Anwar factor

The grievances against the BN were very well articulated by Anwar Ibrahim, the charismatic, opposition icon and de facto leader of PKR. Anwar Ibrahim started as an Islamic student activist who later championed Malay nationalism after he joined UMNO in 1982. In 1998, after he was sacked as UMNO Deputy President and Deputy Prime Minister, Anwar established, through his wife, KeADILan as a multi-racial platform which later emerged as PKR. In 2008, Anwar presented himself as a Malaysian leader fighting for equality, justice, and fairness for all Malaysian races. As a first step, he promised Chinese and Indians that he would eliminate the New Economic Policy which embodied all the ethnic discrimination and ethnic privileging.

It is also significant to note that Anwar Ibrahim understood the mood of the electorate better than any other political analyst. To capitalize on the public disillusionment, Anwar Ibrahim formed two separate alliances with DAP and PAS because of their different ideological foundations. The three parties agreed not to contest against each other so as to present a united opposition front to the BN. The seat negotiations were difficult but ultimately successful in peninsular Malaysia. Anwar allowed the DAP and PAS to contest in their respective strongholds. PKR settled for a few safe seats and many seats not coveted by DAP and PAS. PKR nominated candidates for 271 generally mixed constituencies composed of Malay, Chinese, and Indians. To make up for its organizational deficiencies, Anwar brought in Party Socialist Malaysia and other civil societies under its banner.

The three parties embraced multiculturalism. They adopted the common goal of denying two-thirds majority to the BN. In their campaign, they highlighted Malaysia's growing crime rate, rising consumer prices, and corruption. They harped on about these issues on a daily basis as they manifested a clear failure of the government. Unlike other leaders, Anwar was not confined to a particular constituency since he was legally barred from contesting until April 2008. This was a blessing in disguise as it allowed him to campaign throughout the country addressing joint PKR-DAP and PKR-PAS ceramahs. A gifted speaker, Anwar was able to convince the Malay and non-Malay voters to vote in a strong opposition to the BN government, which was depicted as inefficient and arrogant.

Alternative media

The opposition parties carried out their campaign through various media outlets. It has often been pointed out that major newspapers and television stations, partly owned by parties in the governing coalition, do not give coverage to the opposition news. Nevertheless, under Abdullah Badawi's four-year rule and especially during the campaign period the opposition did receive a good amount of media space. A content analysis of eight newspapers, the radio and the television, conducted by the Electoral Studies Unit of the International Islamic University Malaysia, showed that the space allotted to opposition parties ranged between 20% and 35% during the 13-day campaign period. The major English daily, the New Straits Times, gave up to 26% of impartial coverage to opposition parties. Another English daily, The Star, provided about 9% coverage, while the Malay language newspaper, Utusan Malaysia, gave about 5% space to the opposition. The English language dailies also provided coverage to the civil societies aligned to various opposition parties.

Still, the Opposition parties were disadvantaged and hence they campaigned on the cyberspace using new technologies such as blogs, SMS, and YouTube. With a population of around 27.1 million in 2007, Malaysia had nearly 14 million Internet users.Footnote 44 There has been a proliferation of independent websites and blogs such as Malaysia Today and Malaysiakini which publicized institutional corruption and other issues, particularly in the judiciary. Malaysiakini was set up in 1999 as Malaysia's first commercial Internet newspaper. The site averages 120,000 visitors a day, of which approximately 80% are from within Malaysia, which compares respectably with the circulation of mainstream newspapers such as the New Straits Times. The opposition parties made good use of this vibrant alternative media on the Internet. They nominated bona-fide bloggers who campaigned online, raised funds through their websites, and won against the ruling party candidates, Bloggers Jeff Ooi won Penang's Jelutong seat, Tony Pua for PJ Utara, NikNazmi for Seri Setia and Elizabeth Wong for Bukit Lanjang in Selangor.

The DAP chairman, Lim Kit Siang ran three blogs which were meticulously updated with multiple posts every day, and many of the party's other leaders followed his example. PAS ran its own online journal HarakahDaily.net which featured six different online television channels and provided original reporting on the election. Anwar Ibrahim wrote his own blog with news links and videos of his party's campaign activities. Anwar used the site to release a video clip, in 1997, showing a high-profile lawyer brokering top judicial appointments, which led to the appointment of a royal commission of inquiry. Through this alternative media, the opposition highlighted Malaysia's rising crime rate, consumer-price inflation, and government corruption urging the voters to deny BN the two-thirds majority it desired. The opposition parties' good performance in the election proves that their voices were heard.

The BN unveiled its campaign site, http://bn2008.org.my along with its manifesto. However, it was half-hearted and suffered from legitimacy crisis. The BN did not take alternative media seriously and relied extensively on newspapers, the print media, and the television. As Abdullah Badawi regretted, ‘We did not think it was important. It was a serious misjudgment.’Footnote 45

Apparently, Barisan Nasional's apathy towards the use of the Internet was one of the major contributors to its losses in the election. The survey by Zentrum Future Studies Malaysia, conducted from 20 February to 5 March 2008 and involving 1,500 respondents, showed that the alternative media had a big influence on voters. The survey found about 65% of the respondents trusted blogs and online media for reliable information as against 23% who relied on the television and about 15% on newspapers.Footnote 46 The opposition parties used this alternative media to reach to the electorate, set aside their ideological differences, posed a united challenge to the ruling coalition, and achieved a stunning electoral victory, which, to many political analysts, was impossible given the entrenched power of the ruling BN.

Election, ethnicity, and democracy

Observers of the 2008 elections have likened the results to a ‘political tsunami’.Footnote 47 The ruling coalition lost its two-thirds majority in the federal parliament, which it had been enjoying since 1969; failed in its attempt to wrest control of Kelantan from PAS; and lost control of four states including Selangor and Penang, two of the richest states in Malaysia. The results indicate a change from race-based politics to multiculturalism.

The results show that the BN component parties were not the only ones to represent the large ethnic groups. The Chinese-based Gerakan and MCA won a combined total of 17 parliamentary seats in Peninsular Malaysia, while the DAP (the Chinese dominated party in the opposition) won 26 parliamentary seats, 12 of which were in constituencies with a heterogeneous ethnic composition (mixed seats). PAS won 23 seats, which included four in Selangor and one in Kuala Lumpur, thus changing the perception of it being a rural Malay party. The PKR won 31 parliamentary seats, 18 of which came from ethnically mixed seats which are traditionally stronghold areas for the BN.Footnote 48 Using the statistical method called ecological inference, Ong Kian Ming estimated that only 58% of Malays, 35% of Chinese, and 48% of Indians voted for BN candidates in West Malaysia. The swing vote from the BN to the opposition was estimated to be five percentage points among the Malays, 35 among the Chinese, and 30 among the Indians.Footnote 49 Many Malaysians voted for the opposition by crossing ethnic boundaries. Evidently, there is a change in the behaviour of the Malaysian electorate towards multiculturalism. Many observers of Malaysian politics attribute this behavioural change to Badawi's failure to tackle corruption, crime, and inflation. Others consider it a genuine revolt against race-based politics. The stability of such a change over time would make it mandatory to revisit the concept of the ‘syncretic state’ ascribed to the Malaysian political system.

The opposition's success in denying the two-thirds majority to the BN is also described as a revolution and ‘a new dawn’ for democracy in Malaysia.Footnote 50 Anwar Ibrahim called it ‘a defining moment, unprecedented in our nation's history’.Footnote 51 It reflects a notable shift in political culture, towards more democratic, transparent, and accountable government.

The incumbent Barisan Nasional faced the biggest challenge in the electoral history of Malaysia. The major peninsular opposition parties were united and received the support of a wide range of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and independent activists. The opposition had a unified platform of multi-racialism, social justice, democracy, and more equitable development, as well as a cooperative strategy. The voice of the opposition was more strident and more assertive during and in the aftermath of the election. The government, on the other hand, seemed more hesitant and in some ways even defensive. The emergence of a strong opposition could help institutionalize the idea of checks and balances in a democratic framework, and would render it difficult for the ruling coalition to opt for repressive policies.

The substance and relative success of the opposition can be traced to the sacking of Anwar Ibrahim, then the deputy prime minister, from all government positions and his expulsion from UMNO in 1998. Anwar's dismissal and subsequent jailing sparked unprecedented anti-government protests and demonstrations, known as the reformasi (reform) movement, that led to the emergence of the four-party alliance known as Barisan Alternatif (BA). The BA mounted a coordinated campaign to unseat the ruling BN. The subsequent split in the opposition in 2001 over the issue of Islamic governance/secular state weakened the opposition as a whole, but strengthened individual parties within the opposition who were free to pursue narrow ethnic-based strategies to gain support.Footnote 52 It is to the credit of Anwar Ibrahim that in the 2008 elections, he brought the Islamic PAS, the secular DAP, and his own multi-ethnic PKR to cooperate and to fight the BN in a united fashion. Indeed, the combined opposition in 2008 was clearly a more formidable force than the earlier opposition coalition. Encouraged by the electoral success, these parties formalized their alliance and established the Pakatan Rakyat (People's Alliance) on 1 April 2008. The Pakatan Rakyat presents itself as a realistic alternative to the ruling BN and its leader, Anwar Ibrahim, is described as the ‘prime minister in the waiting’.

The re-emergence of the opposition coalition in the form of Pakatan Rakyat might be seen as a refreshing development towards a two-coalition ‘turnover’ system. The BN and the opposition coalition competed in the elections and offered distinct political platforms and policies to the electorate. The two-coalition or two-party system is found in many democracies including the United States and Canada. Such a system would allow for deepening democracy in Malaysia.

The 2008 elections also witnessed an assertive role played by various non-governmental organizations and other civil and political forces in the society. It is extremely important for a stable democracy to have a strong and vibrant civil society. The Malaysian non-governmental and civil societies, laced with ‘new media’, braved various obstacles and persevered in asserting their role. The rank and file of civil societies acted as candidates, campaign workers, and election monitors for the opposition coalition. The contesting parties and affiliated civil societies made greater use of the internet to express their dissenting views with the ruling coalition. Internet sites have increased significantly and the numbers of hits on the most popular ones have been tremendous. The Internet will help propel the growth of stable social structures and institutions of democracy. In sum, the 2008 elections have taken Malaysia one step closer to both mature democracy and multiculturalism.

Conclusion

The Barisan Nasional, which scored its greatest electoral victory ever in 2004, was returned to power in 2008 with a smaller majority and the loss of five states. Unlike earlier elections where the ‘three Ms’ – media, money and machinery – determined the electoral outcome, the outcome of the 2008 elections was fought and won on the basis of issues. Abdullah came to power in 2004 by promising to lead a clean administration and by stressing the need for greater transparency, accountability, and increased bureaucratic efficiency. However, the reforms he instituted did not meet the public expectation. A number of factors contributed to a rising discontent among Malaysians across racial divides, including rising crime, a number of corruption scandals, the weaknesses of the judicial system, and interferences with the appointment of senior judges and increased food and fuel prices. The BN had severely underestimated the extent and depth of the discontent particularly among the Chinese and the Indian communities which led to series of street demonstrations. The BERSIH and HINDRAF demonstrations, a few months prior to elections, seriously dented the popularity of Abdullah and the BN administration. In particular, the MCA, Gerakan, and the MIC lost ground through the growing discontent among minorities who felt that these parties were unable to protect their interests.

The opposition parties joined hands under the leadership of Anwar Ibrahim and capitalized on the public anger over transparency and accountability. Using alternative media, they highlighted the weaknesses of the government and campaigned effectively to deny the BN the two-thirds majority. They promoted multiculturalism and the electorate obliged by voting across ethnic boundaries. They also benefited from inter-party and intra-party factionalism in the BN.

One of the most noticeable aspects of this election was that the BN and the opposition alliance reacted to the election result with grace and restraint. Abdullah Badawi praised democracy and thanked the public for the strong message. Opposition leaders asked the public to remain calm and refrain from public celebrations that may lead to violence. A responsive ruling coalition with a reduced majority and a responsible strong opposition in the parliament should help the Malaysian political system to be more accountable, transparent, and democratic.